THINK OF SOME immensely successful companies that have launched breakout products over the past decade. My starter list is shown in figure 11.1. At first glance, these blockbusters appear to have little in common. The list spans multiple industries, and these companies provide services or products, use sophisticated technologies or off-the-shelf solutions, and sell through Internet or brick-and-mortar facilities. And yet, I would argue that there are strong commonalities explaining how and why each of these companies succeeded in redefining their respective marketplaces.

Figure 11.1 Breakout products and services

Each of these companies succeeded by:

• Targeting customers who were poorly served by current products and services.

• Focusing on different performance attributes that addressed unmet consumer needs, rather than mimicking the key product characteristics of incumbent market leaders.

• Substantially changing the “4Ps”1 that serve to define what, where, and how mainstream products are marketed, priced, and sold.

• Deconstructing and reconstructing prevailing value chains, characterizing the way work gets done.

• Expanding the market by bringing nonconsumers into the category and getting current customers to buy more.

• Making competitors irrelevant (at least temporarily) by fundamentally changing the basis of competition.

If you chose other examples of breakout success, see if these new rules of doing business also apply to the companies on your list.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to observe the common conditions underlying successful companies. But it’s another (and much harder) challenge to presciently identify promising opportunities and be the first to introduce the “next new thing.”

Over the past two decades, three business-strategy frameworks have emerged, all of which provide useful guidance to entrepreneurs and corporate innovators seeking to identify meaningfully differentiated products and services that deliver a compelling consumer value proposition: Youngme Moon’s breakout positioning,2 W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne’s Blue Ocean strategy,3 and Clayton Christensen’s disruptive technology.4

While each of these approaches adopts a different strategic perspective, they share a clear directive for enlightened companies to reject conventional industry norms, structures, and category images by focusing on new product attributes that appeal to consumers who are poorly served by existing products.

Breakout Positioning

In chapter 9, I showed that competitive dynamics in most industries tend to follow a predictable pattern of tit-for-tat replication and performance augmentation, which, over time, results in increasingly undifferentiated products targeting and overserving the same customers.

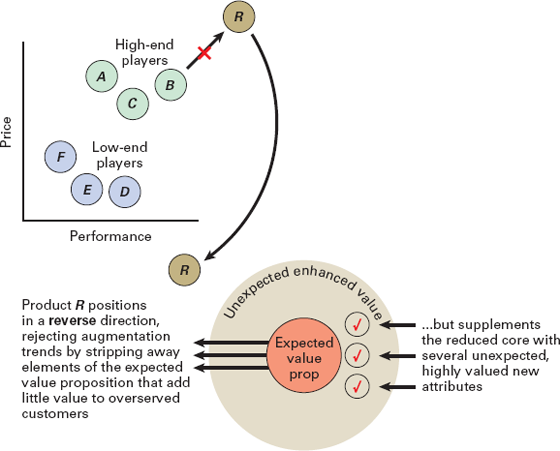

These circumstances create opportunities for an enlightened market entrant to reconceptualize the design of new products and services to better align with the needs of poorly served customers. Two distinct types of breakout positioning strategies warrant attention: reverse positioning and breakaway positioning.5

Reverse Positioning

Practitioners of this approach purposely reverse the trend of constant augmentation of product performance on traditional product attributes. This is not to say that reverse-positioning entrants simply “dumb down” product performance in order to offer budget prices, typical of low-end providers within a current category. Rather, purveyors of reverse positioning recognize that a growing number of consumers are simply not well served by traditional high- or low-end industry incumbents (figure 11.2).6 In such cases, high-end players offer too many enhancements that add more cost than real value. (Do you really need more pixels on your smartphone screen than can be detected by the human eye?)7 But low-end entries simply don’t provide enough functionality or convenience to please dissatisfied consumers either. (Are those knee-jamming, nonreclining seats on long-haul budget-airline flights really worth the cost savings?)8

Figure 11.2 Reverse positioning

In response, successful reverse positioning providers strip out features from high-end offerings that don’t add appreciable value for many consumers, and instead add new, unexpected, and highly valued product attributes that were overlooked by existing players. The net result is a far more compelling value proposition for a potentially large segment of consumers whose needs were not served well by any current products on the market.

For example, when JetBlue entered the financially troubled U.S. airline industry in 2000, a number of legacy carriers (like American, United, and Delta) all vigorously competed to outdo each other on high-end amenities: multiple classes of service, full meal service, on-board music and movies, and private lounges for frequent travelers. At the low end of the market, budget carriers (like Spirit and Southwest) stripped out virtually all creature comforts, packed more, smaller seats into their aircraft, and sharply reduced fares.

JetBlue recognized that there was an opportunity to create a better passenger experience for customers who were willing to pay a small premium over budget carriers to enjoy new types of amenities that were simply not available on legacy airlines.9 In designing its new service, JetBlue started by eliminating costly features typically found on full-service airlines that created little perceived customer value.

TABLE 11.1

JetBlue’s Reverse Positioning: Eliminated Amenities

| Eliminated Amenity |

Rationale |

| Meals |

No meals are better than bad meals. |

| Multiple service classes |

Unnecessary for many consumers if coach service is good enough. |

| Private lounges |

Low value proposition for most passengers. |

| Onboard movies on centrally located monitors |

Limited selection to satisfy diverse passenger preferences. |

In exchange, JetBlue added a number of unique and highly visible new amenities that were enthusiastically welcomed by many passengers, earning the company a reputation as America’s “cheap chic” airline (table 11.2).

TABLE 11.2

JetBlue’s Added Surprise and Delight Amenities

| Added amenity |

Rationale |

| Increased legroom |

Highest in industry; highly valued, tangible benefit. |

| Leather seats |

Previously not offered in coach class. |

| Satellite TV at each seat with dozens of channels |

Unexpected and unique source of customer delight. |

| Premium snacks |

Great snacks more pleasing than bad meals. |

| Friendly cabin service |

Strong differentiator relative to legacy airlines. |

A hallmark of reverse-positioned products is that they have the potential to surprise and delight customers with unexpected features not found anywhere else. As a testament to its successful reverse-positioning strategy, JetBlue has received the highest customer satisfaction rating among U.S. low-cost carriers for eleven consecutive years,10 and has consistently outscored the full-service legacy carriers on customer satisfaction as well.11

Another illuminating, but lesser known, case of successful reverse positioning can be found in the hotel industry. As a globetrotting consultant for over three decades, I have had the opportunity to personally experience the consumer value propositions offered in this intensely competitive sector. To simplify an understanding of competitive dynamics in the hotel industry, consider two distinctly different product segments: high-end, business-oriented hotels (such as Marriott, Westin, Ritz-Carlton, and Four Seasons) and budget hotel chains (such as Motel 6, Days Inn, Super 8, and Comfort Inn).

Customers like me are extremely attractive to business hotel operators, as we travel often, have access to generous expense accounts, and participate in business conferences and meetings that generate sizeable revenues. As a result, high-end hotel chains have competed vigorously for our patronage with a rich set of amenities and conveniences, including: prime locations in city centers; luxury dining and conference center facilities; round-the-clock room service; concierge services; fully equipped fitness centers; pools and spas; spacious, well-furnished rooms; minibars; and complimentary bathrobes and personal-care products. Needless to say, these amenities are costly, driving individual room prices in major metropolitan areas to levels that can exceed $600 per night.12

Since all high-end business hotel chains compete on largely the same performance attributes, it is difficult for any one player to stake a claim to unique services or advantaged prices. For example, in one such attempt to break away from the pack in this highly competitive industry, the Westin chain launched a campaign in the late 1990s to develop the world’s most comfortable hotel bed. After testing hundreds of beds, pillows, and linens, Westin invested $30 million to equip its hotels with the aptly named “Heavenly Bed.” From personal experience, I can attest that they indeed introduced an exquisitely comfortable product. Advantage Westin.

But now put yourself in the shoes of competing hotel chains. Would you allow an archenemy to maintain bragging rights to the most comfortable bed in the industry? In the years following Westin’s launch of the Heavenly Bed, Hilton announced the introduction of its own Serenity Bed. Marriott invested a reported $190 million to introduce its Revive Collection. Radisson introduced its Sleep Number bed. Crowne Plaza responded with its Sleep Advantage program. Hyatt rolled out its Hyatt Grand Bed. Westin’s competitive advantage was short-lived and precipitated an augmentation war where no one won, except for customers who could afford to pay more for a better night’s sleep.13

This intense battle for supremacy in sleeping comfort was not fought in the low-end segment of the hotel industry. Budget hotels, more likely to be located at highway intersections than downtown, compete on different terms to attract a different type of customer, where low price is the paramount consumer consideration. As such, budget hotels offer accommodations that are “good enough” for their price-sensitive consumers. That’s not to say that budget hotels don’t engage in their own form of tit-for-tat replication and augmentation. With nightly rates often below $50, these chains tend to restrict their attention to more prosaic amenities, such as free breakfast and Wi-Fi access.

As it turns out, neither of these two segments of the hotel industry served my needs very well on short solo business trips. More generally, they also fail to address the preferences of high-income, experienced travelers who frequently visit city centers for an urban leisure experience.

First, this sophisticated segment of frequent travelers would certainly reject budget hotels, whose location and lack of panache are antithetical to their needs and values. However, full-service business hotels are also often a poor fit, offering more amenities than these travelers value or are willing to pay for.

For example, savvy and self-sufficient customers are certainly capable of, and may indeed prefer, carrying their own luggage without bellhop assistance (after probably having maneuvered their own suitcases through airports, subways, or taxis). As seasoned travelers, they are likely to be happy to obtain their own room key from an automated kiosk, without waiting in line for assistance from a desk clerk, and to select their own restaurants and theaters without an on-site concierge. (Empowering mobile devices are the norm for sophisticated travelers.)

This customer segment also has little interest in spending much time in their hotel room, and thus puts low value on spacious accommodations with sumptuous furnishings, particularly at prices commensurate with such luxuries. Similarly, when traveling alone, business travelers rarely have the time or interest in dining alone in a fancy hotel restaurant, while leisure travelers often prefer the diverse choices of renowned independent restaurants over hotel fare.

In 2008, serial entrepreneur Rattan Chadha, a retail-clothing company founder and CEO—recognized the opportunity for a reverse positioning strategy to better serve the needs of customers they characterized as “a mix of explorer, professional, and shopper.”14 In creating a new hotel chain called citizenM (M for mobile), he retained the few key features of traditional high-end business hotels that were highly valued by their target customer—most notably, convenient downtown locations, fast free Wi-Fi, high-definition TVs, comfortable bedding, and luxury showers, while stripping out most of the other typical amenities of high-end hotels that added more cost than value.

In place of these eliminated amenities, Chadha introduced unusual hotel design concepts specifically intended to surprise and delight citizenM’s target customers. For example, the founder envisioned that solo business travelers would likely prefer to eat a light dinner at a self-service counter or lounge chair, as opposed to sitting at a restaurant table alone and being served by a waiter. While weekend leisure travelers would probably dine at nearby city restaurants, they might welcome a quick snack in pleasant surroundings after a long city walk. Therefore, when guests enter a citizenM hotel they encounter a large downstairs common space named the living room, loosely subdivided by high-end designer furniture and contemporary art. This includes a central area referred to as canteenM, where guests can order coffee or a cocktail and pay for self-serve food items.

TABLE 11.3

citizenM’s Reverse Positioning

| Eliminated amenity |

Rationale |

| Bellhops |

Customers can/prefer to carry their own luggage. |

| Front-desk clerks |

Key issue and payment can be handled by automated kiosks or via mobile devices. |

| Concierge services |

Target customers are self-reliant on concierge mobile apps. |

| Hotel restaurants and room service |

Most target customers prefer self-serve food service, stocked with healthy, fresh food choices available 24/7. |

| Large rooms and plush furniture |

Not a priority for customers in the target segment, who spend little time in the room. |

| Conference facilities |

Not relevant for most target customers. |

Chadha’s intent was to create a pleasant, functional shared space attractive enough that guests would prefer spending their downtime there rather than in their rooms. This allowed Chadha to make citizenM’s guest rooms unusually small (no wider than their king-sized bed). The citizenM standardized room modules are entirely manufactured off-site and transported to the hotel site during construction. Yet the rooms are luxurious, including a rain-head shower, high-quality bedding, in-room tablets that provide free movies, Internet access, and personalizable mood settings. Once entered, guest preferences are stored in a central database so that rooms can be personalized for subsequent visits (figure 11.3).

Figure 11.3 citizenM reverse positioning: a, lobby area; b, canteenM; c, typical citizenM room. Photos courtesy citizenM.

This reverse-positioning strategy of citizenM allowed the company to reduce construction costs and staffing levels by 40 percent relative to industry norms. As a result, citizenM can set their prices at less than half the room rate charged by high-end business hotel chains, and citizenM’s value proposition has strongly resonated with its target audience. Since its 2008 launch in Amsterdam, citizenM has expanded operations to New York, London, Paris, Glasgow, and Rotterdam, consistently achieving occupancy rates above 90 percent.15

Reverse-positioning strategies have also been successfully deployed in many other industries from fast food to furniture retailing. By reconfiguring the design of products and services to surprise and delight customers, as shown in table 11.4, reverse positioning can help companies to profitably break away from the pack in intensely competitive industries.16

TABLE 11.4

Additional Reverse Positioning Examples

| In-N-Out Burger vs. Fast Food Market Leaders |

| Eliminated Feature |

Added Surprise and Delight Elements |

| Breakfast fare. |

Freshly baked buns. |

| Chicken and fish menu items. |

Fresh vegetables, delivered daily. |

| Happy meals and deserts. |

All hamburgers cooked to order. |

| Children’s play apparatus. |

Secret sauces, known through word-of-mouth. |

| IKEA vs. Traditional Furniture Retailers |

| Eliminated Feature |

Added Surprise and Delight Elements |

| Assembled furniture, built to order. |

Full-room solutions, designed for home assembly. |

| Highly durable construction at commensurately high prices. |

Immediate availability and self-delivery at attractively low prices. |

| Attentive salesperson assistance. |

Extremely wide merchandise selection with a variety of self-help tools. |

| Long wait times for delivery. |

Swedish meatballs and babysitting services. |

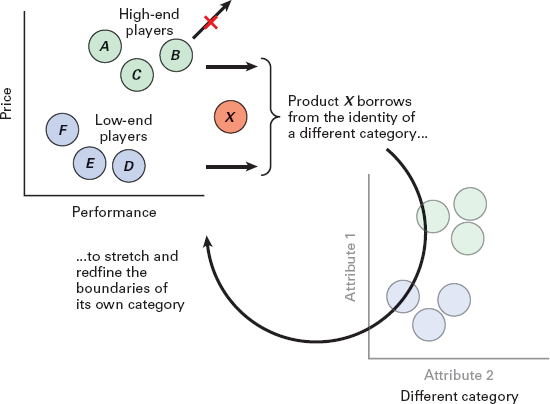

Breakaway Positioning

The second class of breakout positioning involves “breakaway” products, so named because of the way some companies have chosen to redefine how consumers perceive their products by borrowing features drawn from an entirely different product category. A company might choose such an approach in order to distance itself from the conventional image consumers associate with a given category—which I have shown often limits meaningful differentiation. Companies pursuing a breakaway positioning strategy imbue their products with attributes never before seen, thereby creating a uniquely appealing and sharply differentiated consumer value proposition (figure 11.4).17 I’ve already described a quintessential example of successful breakaway positioning in chapter 6: Swatch.

Figure 11.4 Breakaway positioning

In the 1980s, Nicolas Hayek, CEO of Société de Microélectronique et d’Horlogerie (SMH), one of Switzerland’s largest watchmakers, faced an existential threat from low-cost quartz digital watch imports from Asia, which were gaining global market share at an alarming rate.18

Traditionally, Hayek’s company competed at the high end of the watch market, selling handcrafted timepieces under the Omega, Tissot, and Longines brand names. These luxury items were sold and repaired in jewelry stores and priced on par with heirloom jewelry.

The advent of lower-cost digital technology in the 1970s spurred rapid growth of a new class of watches, which served as accurate, if not particularly stylish, functional tools. Hayek’s problem was that SMH was not well positioned to compete effectively in this rapidly growing segment, which favored competitors with low-cost mass production and distribution through mass merchandisers.

To complicate matters, the emergence of quartz digital watches reinforced the category norm that most consumers only needed to own one or two watches, at most. For purely practical purposes, a low-priced entry from Casio or Seiko could reliably serve a consumer’s functional timekeeping needs for under $20. At the high end, some consumers with the requisite income might also opt for an additional watch as an aspirational showpiece. Under any circumstances, most adults who required a watch already had what they needed. With high reliability at both ends of the market, replacement demand was relatively low.

Under these circumstances, SMH had to break away from the conventional watch category in which it was poorly positioned to compete. Hayek needed to create a new product that would stimulate significant new consumer demand and distinguish the company from traditional watch manufacturers, enabling SMH to capture a dominant share of this newly created demand.

In other words, rather than join a dogfight in the watch industry against stronger combatants, Hayek needed to become a cat.

To do so, Hayek designed a radically new product, which borrowed heavily from the fashion accessory category. Why fashion? If consumers were prepared to own several scarves, pairs of designer shoes, or pieces of costume jewelry, why wouldn’t they similarly choose to own a number of affordable watches from a wide selection of colorful and boldly styled designs?

Everything Hayek did in managing the launch of Swatch was thoughtfully conceived to cultivate a brand image more aligned with the fashion industry than with traditional watches. To understand how Hayek executed his breakaway positioning strategy, consider the 4Ps associated with Swatch’s market entry.

Swatch’s Product

Swatch was the first watch company to introduce boldly colored plastic casings across its product range. Its Milan-based design studio turned out hundreds of creative styles every year to appeal to a variety of tastes. Swatch rotated its entire product lineup on a seasonal basis and never repeated a design, regardless of popularity (figure 11.5). In addition, Swatch frequently teamed up with globally recognized designers, like Keith Haring and Mimmo Paladino, to introduce special edition models that further piqued consumer interest.19

Figure 11.5 Representative Swatch watch designs

Such product cues, while unheard of in the watch industry, were commonplace in the fashion industry. Not only did Swatch’s frequent design changes encourage fashion enthusiasts to purchase multiple watches for their personal collection, but the company also stimulated entirely new demand from consumers historically ignored by the watch industry: tweens.

Swatch’s Promotion

Prior to Swatch, Swiss watches were (and to this day, still are) promoted with classy print ads in magazines catering to high-income readers. Since Swatch was intent on shattering the staid image consumers traditionally associated with the Swiss watch industry, it deliberately crafted a radically different marketing approach. Swatch’s earliest print ads featured provocatively clad models set against colorful backgrounds to highlight Swatch’s unusual product designs. In its television ads that followed, models gyrated to heavy rock music while adorned with colorful Swatches.

To further break from longstanding tradition, Swatch used guerilla marketing to create market buzz when entering a new country. For example, to celebrate its entry into the German market, Swatch created a five-hundred-foot working model of a Swatch watch mounted on the tallest skyscraper in Frankfurt. The message emanating from all of these promotional initiatives was crystal clear: Swatch was not just another watch brand in an already crowded category.

Swatch’s Price

Historically, Swiss watches carried high price tags—often topping $1,000—necessitating a deliberate consumer purchase process. At the opposite end of the spectrum, cheap quartz digital watches from Asia, generally priced below $20, were largely viewed as disposable functional tools. For Hayek, neither of these price points was relevant to Swatch’s desired positioning. Instead, the company chose to price Swatch on par with stylish costume jewelry, like a colorful bracelet, necklace, or brooch. Accordingly, Hayek initially set the price of a Swatch at $40—low enough to stimulate impulse purchases, but high enough to reflect the product’s emotive appeal.

Hayek’s pricing strategy also reinforced other distinctive aspects of Swatch’s breakaway product positioning. Across the globe, Hayek priced his products in simple round numbers—$40 in the United States, SF 50 in Switzerland, DM 60 in Germany, and ¥7,000 in Japan.20 Swatch prices were transparent and memorable, and every model carried the exact same price tag, including limited-edition designer pieces, which sold out within hours of launch. Swatch’s price strategy signaled that none of its products was more valuable than another. It was up to consumers to express their own preferences in selecting from Swatch’s broad and whimsical product line.

Swatch did not change its prices around the globe for over a decade, further reinforcing the company’s distinctive brand identity.

Swatch’s Place

Not surprisingly, Swatch eschewed traditional channels of distribution. Rather than placing its unusual product line in department stores or jeweler’s display cases alongside conventional watches, Swatch opted for unique points of sale. The company opened over two dozen dedicated Swatch stores in the fashion districts of major cities and located boutiques within upscale department stores like Bloomingdales and Neiman Marcus. The company also opened pop-up stores in unusual locations—for example, selling its popular Veggie line of watches in urban fruit and vegetable markets.

Reflecting on Swatch’s breakaway positioning strategy, Nicolas Hayek observed that “everything we do and the way we do everything sends a message.”21 Within a decade of its launch, Swatch sold over one hundred million watches worldwide, making it the best-selling watch of all time.

If Swatch’s strategic playbook sounds familiar, it should. While Steve Jobs has earned accolades for his visionary leadership of Apple, in many respects Jobs followed the same playbook that proved highly successful for Nicolas Hayek at Swatch, twenty years earlier.

• Both companies were in deep trouble when the CEO took control (in Apple’s case, when Steve Jobs returned after a twelve-year absence).

• Both created products that enabled consumers to think in a completely different way about the value proposition in the categories they entered.

• Both utilized elegant design as a key element of the brand promise for every new product release.

• Both developed products which elicited a strong emotive appeal, above technical merits.

• Both relied on “big bang” product launches with tightly choreographed event management and effective public relations. As a result, long lines at company stores greeted each new product release.

• Both CEOs had a healthy disregard for conventional market research.

• Both used simple pricing as a distinguishing element of their product offer: Swatch watches priced at $40 and Apple iTunes songs priced at ninety-nine cents.

• Both tightly controlled all aspects of brand management and consumer touchpoints affecting the consumer experience.

• Both employed high levels of vertical integration, including company-owned and branded retail outlets.

• Both maintained strong brand discipline in order to reinforce their brand promise in the long term.

• Both CEOs were revered within their company.

In addition to Swatch, breakaway positioning has also been successfully deployed in a number of other categories, such as diapers, snack bars, and household liquid cleaners (table 11.5). In each of these cases, an incumbent market leader created a new product by borrowing attributes from an entirely different category. This enabled the company to break away from competition and expand the size of its addressable market.

TABLE 11.5

Breakaway Positioning Examples

| Original Product |

Traditional Basis of Competition |

Breakaway Product/Borrowed Category |

New Basis of Competition |

| Huggies Diapers |

Absorbency Comfort

Ease of application |

Pull-Ups Training Pants/Children’s underpants |

Transition product for entirely new market (children ages 3–4) |

| Mr. Clean Liquid Cleaner |

Cleaning power Price/Value |

Swiffer/Dry and wet mops |

Convenience Effectiveness Speed of use |

| Special K Cereal |

Vitamin/Health benefits

Taste |

Special K Cereal Bars/Snack bars |

On-the-go consumption

Guiltless snacking |

Take the diaper category for example. For years, Kimberly Clark (Huggies) and Procter & Gamble (Pampers) engaged in a zero-sum game for market-share leadership in a category constrained by the relatively slow growth in the number of babies under two years old. Each product improvement introduced by one competitor was quickly replicated by the other, nullifying the possibility for sustained competitive advantage. Moreover, both companies undoubtedly found it frustrating to compete in a category where buyers (parents) and users (toddlers) couldn’t wait to stop using their product.

In 1989, Kimberly Clark launched a breakaway product called Pull-Ups that instantaneously doubled the size of its addressable market and gave the company unchallenged access to new consumer demand. By combining the product attributes of diapers with a different category (children’s underwear), Pull-Ups were designed as a potty-training transition product that three- and four-year-old children could use on their own. Toddlers loved Pull-Ups because it made them feel like bigger kids. Parents loved Pull-Ups because they helped to avoid the messy accidents that children experience transitioning from diapers. Kimberly Clark loved Pull-Ups because it took Procter & Gamble over a decade to mount a competitive response. As a breakaway product, Pull-Ups figuratively caught Procter & Gamble with its pants down.

In another category, Procter & Gamble enjoyed its own breakaway product success with Swiffer dry and wet mops. For years, Procter & Gamble was the leading household liquid cleaner provider, led by their Mr. Clean brand. But Mr. Clean faced three problems that constrained its profitable growth.

First, the market for liquid household cleaners was mature and slow growing. Second, consumers dreaded the chores that used Mr. Clean, particularly wet mopping the floor, so household usage rates were low. Third, profit margins for Mr. Clean were depressed by competition from value and store brands.

Procter & Gamble overcame these headwinds by breaking away from the traditional household liquid cleaner category. To do so, it borrowed product attributes from a different category to create the Swiffer floor-cleaning system. With Swiffer, there was no need for buckets, water, or liquid cleaners like Mr. Clean. Instead, a consumer buys a Swiffer mop, designed to be used with proprietary replaceable cleaning pads for dry sweeping or wet mopping.22

Given Swiffer’s simplicity and ease of use, consumers tended to clean their floors more often, thereby increasing overall demand. Because of its design and dominant share in the newly created category, Procter & Gamble was able to earn attractive margins from its “razor and blade” business model. The company’s breakaway launch of Swiffer redefined the floor-cleaning product category and created a new billion-dollar brand.23

As a final example, it should be clear how Kellogg’s extended beyond its breakfast cereal roots to create a new line of Special K cereal bars by borrowing the eat anywhere/anytime convenience associated with snack foods. In so doing, Kellogg’s created a new demand for guilt-free snacking which reached consumers through new channels of distribution.

The examples in this section illustrate how reverse and breakaway positioning challenges the industry norms that confine most businesses to operate within the boundaries of established bases of competition. New products pursuing reverse positioning identify opportunities to attack poorly served segments of the market by reconfiguring product attributes within a given category in different ways. Successful reverse positioning practitioners surprise and delight poorly served customers to gain significant market share at attractive margins.

Strategies grounded in breakaway positioning seek to attract new customers by creating hybrid products that combine the attributes of products from different categories. When successful, breakaway positioning can dramatically expand the size of the addressable market and give the pioneer a dominant share for many years.

The bottom line is that when companies find themselves caught in a competitive dogfight, breakout positioning strategies provide an effective way to change the rules of engagement.

Blue Ocean Strategy

The term Blue Ocean conjures up an image of uncharted open waters, which is precisely the connotation that W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne had in mind when they published their acclaimed 2006 book entitled Blue Ocean Strategy.24

Similarly to breakout positioning, Blue Ocean thinking starts with the recognition that most companies operate according to self-imposed industry norms, where the paramount objective is to steal market share by outperforming competition with better products or lower cost. Kim and Mauborgne characterize such competitive environments as Red Oceans, symbolizing the bloody battles between sharks (companies) fighting for the same prey (current customers) in well-defined hunting areas (current markets and channels). Most mature products compete in Red Ocean markets that limit opportunities for attractive growth and profitability, as shown in table 11.6.25

TABLE 11.6

Blue Ocean vs. Red Ocean Strategies

| Red Ocean Strategy |

Blue Ocean Strategy |

| Compete in existing market space |

Create uncontested market space |

| Beat the competition |

Make competition irrelevant |

| Exploit existing demand; steal share |

Create and capture new demand |

| Optimize the value/cost tradeoff |

Break the value/cost tradeoff |

| Align the whole system of a company’s activities with its strategic choice of product superiority or low cost |

Align the whole system of a company’s activities with its strategic choice of differentiation and low cost |

| Red Ocean Characteristics |

Blue Ocean Characteristics |

| Well-defined industry norms and category structure |

New rules unlocks new demand, fueling high growth |

| Low growth, high concentration, and intense competition |

Blue Ocean entrant captures dominant share at attractive margins |

| Low margins (except perhaps for industry leaders and niche specialists) |

Incumbents poorly positioned to effectively respond |

In contrast, Blue Ocean players consciously reject Red Ocean behaviors by fundamentally reconstructing the basis of competition within their product category. The focal point is targeting new customers who are poorly (or not at all) served by Red Ocean incumbents. Responding to the unmet needs, Blue Ocean entrants design new products and services with the objective of increasing perceived value, while also lowering cost. Unlike conventional industry thinking that assumes companies must choose between best product and lowest cost, Blue Ocean strategies strive to deliver both.26

How is this possible? The key lies in recognizing that beauty lies in the eye of the beholder. The definition of “best product” depends entirely on the preferences, values, and needs of a particular class of consumer. By designing new product features to appeal to customers who are not interested in current best-in-class offerings, Blue Ocean entrants can deliver extremely high value for the consumer (which may translate into a higher consumer WTP) and lower costs.

For example, Kim and Mauborgne cite Cirque du Soleil as an archetype of successful Blue Ocean strategy. At first glance, the circus industry appeared to be an unattractive sector for a new player to enter in the early 1980s. Attendance had been falling for years because of an expanding array of entertainment alternatives and growing consumer concern over the poor treatment of circus animals. High costs and the need to keep ticket prices low to attract a child-centric audience also constrained margins for traditional circus operators.

But Guy Laliberté, a Canadian former street performer, recognized the opportunity to fundamentally reinvent the circus to appeal to types of customers long ignored by traditional circus producers: upscale adults unaccompanied by children, and corporate clientele. To appeal to this mature consumer target, Laliberté eliminated costly, low-value features found in traditional circuses—most notably, animal acts—and added a unique combination of gymnastics, ballet, music, and sophisticated set designs to create an entirely new entertainment experience.

Not only did Cirque du Soleil’s customers not miss the signature animal acts of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus shows, but they actually preferred Laliberté’s alternative entertainment genre. As it turns out, the highest-cost activities associated with operating a traditional circus are the care, feeding, training, and transporting of animals. By reinventing the circus, Cirque du Soleil was able to lower costs, charge higher prices, and achieve unprecedented growth. Cirque du Soleil turned a Red Ocean business into a Blue Ocean phenomenon.

How can your company (or entrepreneurial endeavor) identify and create Blue Ocean opportunities? With any successful new product-development initiative, the starting point is to identify the target group of customers that can be better served by a new product or service. The appropriate target is dissatisfied consumers of current products, or those sitting on the sidelines because no available products deliver sufficient value.

Armed with an understanding of unmet consumer needs, the next step is to apply the four-actions framework to fundamentally reconstruct the value proposition offered by products and services currently in the marketplace.27 The four actions refer to how products can be reconfigured as Blue Ocean entries to unlock untapped demand from target customers:

• Eliminate Which elements of current products should be eliminated because they deliver little (or negative) value to target users?

• Reduce Which elements should be reduced because, at current levels, they overserve customers, adding more cost than value?

• Raise Which factors should be raised because, at current industry levels, they underserve customers, compromising value creation?

• Create Which factors should be created, opening an entirely new path to value creation never before offered in the industry?

Table 11.7 illustrates how Cirque du Soleil applied the four-actions framework to transform the Red Ocean circus category into a Blue Ocean market opportunity.28

TABLE 11.7

Cirque du Soleil’s Four Actions Framework

| Eliminate |

Reduce |

| Star performers |

Clowns |

| Wild animal shows |

Slapstick humor |

| Aisle concession sales |

Thrill and danger |

| Multiple show arena |

|

| Raise |

Create |

| Unique venue design |

Theme-based shows |

| |

Refined environment |

| |

Multiple productions |

| |

Artistic music and dance |

To see another example of how the four-actions framework has been applied to create a Blue Ocean opportunity, consider the fitness center sector. At the beginning of each semester, when I ask my MBA students to identify their favorite brands, one of the most frequent mentions is Equinox, a high-end fitness club featuring sophisticated training equipment, a wide range of fitness classes, plush changing rooms, eco-chic amenities, healthy snacks and smoothies, and inviting lounge spaces—with commensurately high monthly membership fees. This combination of features plays well in the upwardly mobile and generally fit group of millennials attending Columbia Business School. But what about a different consumer segment, personified by a fictitious persona I’ll call Betty?

Betty is a forty-one-year-old homemaker and part-time worker with two young children, living in an inner suburb of a major metropolitan area. Like many of her peers, Betty constantly feels stressed by juggling her many responsibilities and has neither the discretionary budget nor the perceived freedom for much “me-time.” Consequently, she hasn’t worked out since college and is admittedly out of shape. Her situation has taken a toll on her figure, fitness, and body image.

One day, Betty’s friend suggests that she take advantage of a complimentary guest pass for the local Equinox club. With some trepidation, Betty arranges a time to meet, and, upon arrival, is given a tour and sales pitch by the club manager. But, almost immediately, Betty finds that every feature proudly showcased by her Equinox guide leaves her feeling anxious and dispirited, as noted in table 11.8.

TABLE 11.8

Incongruity Between Value Proposition and Selected Customer Needs

| Equinox Feature |

Betty’s Reaction |

| Impressively classy and chic lobby design. |

Looks expensive. |

| Large array of sophisticated fitness devices. |

Way too complicated and overwhelming. |

| Muscular men and fit women using exercise equipment, weights, and cardio machines. |

I’ve never looked as fit and strong as they do, particularly now. |

| Mirrors everywhere. |

A constant reminder of my pudgy figure. |

| Healthy-snack bar. |

I would never spend $9 for a smoothie. |

| Plush women’s locker room, sauna, and pool area. |

I wouldn’t feel comfortable here, given my poor body image. |

Despite its ostensible amenities and charms, the Equinox did not serve Betty’s needs well.

After recounting her experience at Equinox, another friend suggests that Betty check out the local Curves fitness club, located in a nearby strip mall. From the instant Betty enters Curves, her experience is completely different and comfortably reassuring. There isn’t a mirror in sight (or men, for that matter), the equipment looks simple and easy to use. A friendly-looking coach is encouraging a small group of women, and most importantly, the club members look just like her (figure 11.6).

Figure 11.6 Equinox (top) vs. Curves (bottom)

Betty learns that the guided workout sessions are designed to last only thirty minutes to accommodate busy schedules, and members come already dressed for their workouts because Curves fitness centers have no changing rooms. By eschewing expensive equipment and amenities, Curves can offer Betty monthly membership fees that are 80 percent lower than those of Equinox.

By understanding the needs of a large segment of consumers like Betty, who were poorly served by traditional fitness centers (and, as a result, were largely ignored by fitness center providers), Curves configured its Blue Ocean entry as depicted in table 11.9. By appropriately eliminating, reducing, raising, and creating fitness center attributes to better serve the needs of women similar to Betty, Curves created an entirely new customer experience, perceived to be better and cheaper than available alternatives. As a result, Curves avoided the fitness center dogfight for current customer market share, and instead unlocked new demand in the category. From its founding in 1992, Curves grew to over seven thousand locations within a decade, peaking at nearly ten thousand facilities in eighty-five countries, with more than four million members in 2006.29 As the Curves example demonstrates, Blue Ocean strategies can create enormous opportunities for growth.

TABLE 11.9

Four Actions Framework for Curves

| Eliminate |

Reduce |

| Men! |

Equipment complexity |

| Mirrors |

Time for workout |

| Changing rooms |

Monthly fees |

| |

Intimidation |

| Raise |

Create |

| Coaching |

Supportive/social environment |

| Ease of getting started |

Comfort of working out with people “just like me” |

| Fun |

|

| Accessibility |

New friends |

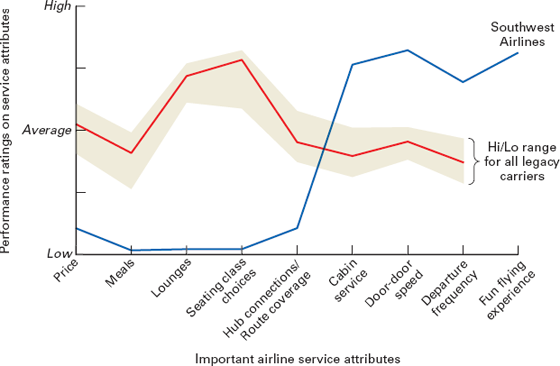

Companies executing effective Blue Ocean strategies are distinguished from traditional competitors by their focus and differentiation. For an example of these distinctions, imagine conducting a survey of a representative sample of experienced air travelers back in the 1990s to ascertain which airline attributes were most important and how each carrier rated on those factors. The results might, hypothetically, look like those depicted in figure 11.7.30

Figure 11.7 Airline industry strategy canvas

The airline attributes most frequently mentioned as being important to experienced flyers are displayed along the horizontal axis, including price, route coverage, seating-class choices, departure frequency, etc. The red line in figure 11.7 displays how consumers rated one particular legacy airline on a scale of 1 to 5 for each of these attributes. Note that the performance ratings for the highlighted airline all hover around an average score. Seating-class choices and loungers are rated a bit higher than average, while meals and cabin service are rated somewhat lower.

Repeating this exercise for the other legacy airlines yields ratings that fall within a relatively narrow range, as shown by the shaded band in figure 11.7. In this example, American Airlines might be rated slightly higher than competitors in departure frequency, but lags behind US Airways on price, United on meals, and Delta on route coverage. In essence, this “strategy canvas” suggests that all airlines compete aggressively on the same performance attributes, but no individual carrier achieves dominant superiority on any single attribute, let alone broad-based market leadership. From this perspective, consumers tend to view all legacy airlines as relatively undifferentiated and mediocre.

The pictorial image conveyed by this strategy canvas is representative of many Red Ocean product categories that conform to tit-for-tat feature replication and performance augmentation across common product attributes. In such circumstances, effective differentiation between incumbent players within the category becomes more blurred over time. Thus, the race toward ever-higher performance on multiple attributes leaves an increasingly large number of consumers poorly served or priced completely out of the market.

Such circumstances create an opportunity for a new entrant to launch a radically reconfigured product or service that addresses the needs of consumers largely ignored by market incumbents. This can be done by incorporating two salient characteristics of effective Blue Ocean strategies: focus and meaningful differentiation.

Focus

Blue Ocean strategies focus on a few select attributes that offer the greatest value to poorly served customers and nonconsumers. As shown in figure 11.7, Southwest Airlines chose to focus on low price, friendly cabin service, door-to-door travel time, and an entirely new attribute: a fun flying experience. Simultaneously, they eliminated many service attributes that had been routinely offered by incumbent airlines, such as meals, seating-class choices (with assigned seats), airport lounges, and hub-and-spoke route networks.

Meaningful Differentiation

By focusing its value proposition, Southwest Airlines could align its entire business model toward operational excellence on selected performance attributes. Southwest achieved competitively advantaged productivity levels by utilizing a single aircraft type on point-to-point flights from secondary airports, with one class of service and no free meals or assigned seating. Thus, Southwest wasn’t just more focused than its legacy airline competitors; it was meaningfully differentiated by being better on cost, departure frequency, door-to-door speed, and an appealing in-flight experience.31

As a result, Southwest has consistently scored at or near the top of customer satisfaction ratings among U.S. airlines while consistently offering the lowest fares, helping the airline to become the largest U.S. domestic carrier. Southwest Airlines successfully executed a Blue Ocean strategy that unlocked significant new demand previously not served by incumbent market leaders.32

Companies that remain true to their Blue Ocean roots can build exceptionally strong brand images, reflecting a clear consumer understanding of their strategic intent to deliver meaningful differentiation. For example, both IKEA and CrossFit applied Blue Ocean strategy concepts to develop meaningfully differentiated offerings within their respective categories. While IKEA may not appeal to all consumer tastes, its image for stylish low-priced home furnishings—reinforced since the company’s founding in 1943—has established IKEA as one of the most valuable brands in the world.33 CrossFit, whose Blue Ocean brand promise of “Forging Elite Fitness,” is resonating with a growing number of extreme exercise enthusiasts (even as it repels less athletically inclined consumers), propelling strong global growth.34

Southwest Airlines has also remained true to its Blue Ocean founding principles and has consistently reinforced its brand image for value and friendly service. For example, in the early 1990s, Southwest’s print ads rhetorically asked consumers, “Can you name the airline with low fares on every seat of every flight, everywhere it flies?” Two decades later, Southwest’s print ads reinforced the same themes, proclaiming, “Low fares. No hidden fees. What you see is what you pay.”

In contrast, legacy airlines have struggled to define a distinct brand promise in the competitive airline marketplace. By attempting to appeal to virtually all consumers, legacy airlines have found it difficult to establish a credible and compelling basis of meaningful differentiation. This challenge is evident in Delta’s nondescript advertising taglines over the past forty years, which provide little evidence of distinct competitive advantage.35

Delta Airlines Advertising Taglines

1972: Fly the Best with Delta

1974: Delta Is My Airline

1980: Delta Is the Best

1983: That’s the Delta Spirit

1984: Delta Gets You There with Care

1986: The Official Airline of Walt Disney World

1987: The Best Get Better

1987: We Love to Fly, and It Shows

1991: Delta Is Your Choice for Flying

1994: You’ll Love the Way We Fly

1996: On Top of the World

2000: Fly Me Home

2005: Good Goes Around

2009: Together in Style

2010: Keep Climbing

2012: The Only Way Is Up

I began this section by noting that most companies conceive and execute predictable Red Ocean strategies within well-established business boundaries. Over time, this common management mindset leads to a blurring of meaningful differentiation between companies competing on the same terms for the same customers. The appropriate Blue Ocean response is to break away from the pack by redefining one or more of the boundaries that have historically constrained industry behaviors. There are six pathways to expand strategic scope in formulating Blue Ocean strategies that have been exploited across a wide variety of industries, products, and service categories.36

Industry

Rather than compete directly in the hotel sector (as citizenM successfully did), Airbnb challenged the very definition of the hospitality industry, which had always assumed that hoteliers needed to manage dedicated facilities. By creating a platform and business model that brings the world’s entire housing stock within the addressable scope of a redefined hospitality industry, Airbnb has enjoyed unprecedented growth. Within seven years of its founding in 2008, Airbnb’s valuation equaled that of the Hyatt and Marriott hotel chains combined.37

Figure 11.8 Blue Ocean Six-Paths framework

Market Segment

I have covered numerous examples throughout this book of new entrants designing a new product or service to appeal to a market segment that had been largely ignored or poorly served by incumbents. Curves, CrossFit, Casella Family Brands, Southwest Airlines, and citizenM all fall into this category.

Buyer Group

A variation on strategies designed to serve a different market segment of customers occurs when a company challenges the defined roles of the individuals who purchase, use, or influence the choice of products. One good example is Novo Nordisk, a Danish pharmaceutical company that has aggressively competed against Eli Lilly in the global market for insulin for many decades. Historically, the two drug giants targeted doctors as the primary customer and promoted their respective products on the basis of their purity, efficacy, and safety. As such, doctors served as product choice influencers by writing prescriptions for patients who rarely knew or cared which company manufactured the product.

But in the mid-1980s, Novo Nordisk recognized the opportunity to change the basis of competition by focusing on the ease with which insulin could be administered by patients. With the company’s NovoPen, patients could administer their required dose of insulin with a single click of a pen-like device, providing a significant improvement in convenience over the prior need for syringes and vials.

This change in the basis of competition enabled Novo Nordisk to market directly to consumers, who in turn asked their doctors to prescribe the desired NovoPen product. In the years that followed, Novo Nordisk gained considerable market share against Eli Lilly, who lagged behind in developing improved insulin delivery systems.

More recently, pharmaceutical benefits managers like Express Scripts have redefined the traditional role of drug companies, doctors, and independent pharmacies in the distribution of prescription medications.

Scope

Internet technologies have radically altered the value chain across multiple industries, empowering consumers to be directly involved in the consumption, production, and recommendation of products and services that were once provided by intermediaries.

Historically, the underlying raison d’être for many companies was to sell a product or service that was too complex, inconvenient, or expensive for consumers to provide for themselves. But technology-enabled self-empowerment has already ravaged a number of industries, including travel agencies, record labels, encyclopedias, daily newspapers, accounting, and book publishing.

In each of these cases, jobs that were initially considered too complex for individuals to perform on their own are now easily handled by the average consumer, in ways that are perceived to be better and much cheaper. For example, who needs a commissioned travel agent when Expedia, KAYAK, or TripAdvisor empowers consumers to plan and reserve trips on their own? The same is true for the impact of streaming music providers on record labels and music retailers, Google News and the Huffington Post on metro dailies, TurboTax and QuickBooks on accounting, and Amazon and Goodreads on book publishers and retailers.

Category Image

By challenging long-standing category images, such as “socks are boring,” “wine is for special occasions,” and “watches are for telling time,” LittleMissMatched, Yellow Tail, and Swatch unlocked latent demand that had not previously been served by industry incumbents. By breaking down stereotypical category images, Blue Ocean strategies can increase the size of a new product’s addressable market.

Time and Place

Changing when and where products are consumed can dramatically alter the competitive landscape. A prime example is CNN’s ascendance, which successfully challenged conventional assumptions on when television news could or should be consumed. More broadly, mobile devices and streaming services have freed customers to consume content wherever and whenever they choose, creating enormous growth opportunities for companies such as Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, WatchESPN, Coursera, and edX.

The breadth of these examples suggests that there are numerous opportunities to break from the industry norms and category structures that often confine companies within mature industries to sluggish growth, copycat competition, and tight margins. In such cases, the resulting loss of meaningful differentiation reflects management choices, not inevitable outcomes. Blue Ocean strategies and breakout positioning can enable companies to reignite profitable growth.

Clayton Christensen’s disruptive technology framework provides a fitting capstone in my quest to better explain how companies can break away from the pack and achieve long-term profitable growth. In his 1997 book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, he provided groundbreaking insight on three key questions:

• Why do companies have such a difficult time sustaining market leadership?

• Why is it so often that newcomers, rather than incumbent market leaders, introduce disruptive technologies and business models?

• How can incumbents avoid this innovator’s dilemma?

To answer these questions, let’s start with Christensen’s definition of disruptive technology. Despite its name, the disruptive technology framework actually can be applied to many new products or services, whether high or low tech. Under his broad conceptual umbrella, Christensen divided product and service launches into one of just two possible categories. The first, sustaining technologies, reflects the routine improvements that every company makes to its products over time in order to appeal to current customers and to respond to competitive pressures. Examples of sustaining technology improvements are echoed in the advertising messages consumers are exposed to every day, like “buy new, improved Crest Toothpaste, now with extra Whitener” or “check out the latest Lenovo desktop computer, now with the 5th Generation Intel Core Processor.”

The second class, disruptive technologies, is aimed specifically at consumers who are overserved by existing products, and may target nonconsumers who simply have no interest in, or are priced out of, the current marketplace. Developing an understanding of the reason mainstream products do not appeal to a large segment of the current market is exactly what gives new entrants ideas for disruptive product and service opportunities.

In chapter 1, I cited several examples of disruptive technologies, like digital cameras, online travel services, ultrasound, and walk-in medical clinics (see table 1.1). The tendency of incumbent market leaders to relentlessly augment product performance through continuous technology improvements eventually alienates a growing number of overserved consumers, who neither value, nor are willing to pay for, the panoply of features in mainstream products. When this situation emerges, new players recognize the opportunity to attract consumers with simpler, “good enough” solutions, possibly including a few unexpected new features which surprise and delight overserved consumers.

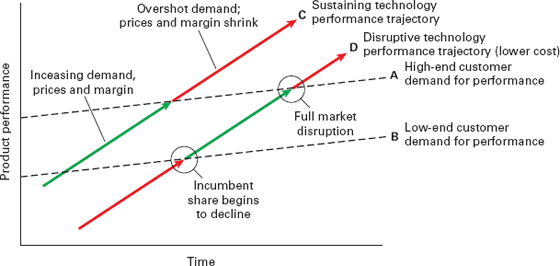

As an example of how low-end disruptive technology dynamics play out, consider the evolution of the personal computer industry, illustrated in simplified terms in figure 11.9.38 In this schematic, the vertical axis measures product performance, whether storage capacity, screen resolution, or processor speed, while the horizontal axis represents the passage of time, as new generations of products are introduced.

Figure 11.9 Sustaining and low-end disruptive technology dynamics

If you happened to be one of the incumbent market leaders in the early stages of the PC business, you probably would have observed at least two large segments of customers in the marketplace. Consumers at the low end of the marketplace didn’t really need the most sophisticated PC products and weren’t willing to pay huge premiums for top performance. This group is depicted as dotted line B in figure 11.9.

At the opposite end of the market were the high-end power users that expected higher performance and were willing to pay more to obtain state-of-the-art technology. Accordingly, in figure 11.9, dotted line A is positioned above dotted line B, indicative of the differentiated needs of low- and high-end consumers.

Another marketplace dynamic that PC providers discovered over time is that customers expect product performance to improve with each new product generation, as a consequence of several factors:

• Human nature Across an array of products, marketers have trained consumers to expect each new product to be better than the one it replaces. Personal computers are no exception, as consumers expect continuous improvements in sustaining technology performance.

• New product uses As consumers gain more experience with products on the market, they often seek new uses, requiring enhanced product performance. As consumers gained an interest in using PCs for gaming, streaming video, storing photos, and business analytics, demand grew for improved processor speed, storage capacity, and screen resolution.

• Competitive pressures With competitors playing leapfrog to gain temporary product performance superiority, the augmentation dynamic I described earlier conditioned consumers to expect continuous improvements in PC performance.

The net result of these marketplace dynamics is depicted in figure 11.9 by the upward slope of lines A and B, which reflects the increase in expected performance by both low- and high-end consumers in the PC market.

One of the breakthrough insights of Christensen’s disruptive technology theory is his recognition that in virtually all industries, engineers are capable of improving product performance at a more rapid rate than is demanded by consumers. This dynamic is illustrated in figure 11.9 by the solid line C, which depicts the rate of product performance improvement from an engineering delivery standpoint. The slope of line C is much steeper than the slope of consumer expectations for improved product performance represented by lines A and B. The difference between the inherent supply of, and demand for, product performance in most industries has profound business consequences.

In the early stages of development of a new product category, the ability to rapidly improve product performance helps drive profitable growth. In the PC industry, for example, a pioneering incumbent would benefit by exploiting the steep sustaining technology performance-improvement curve because in doing so it could go from initially serving the performance needs of low-end consumers in the marketplace (where lines B and C intersect), to appealing to high-end power users (where lines A and C intersect). By moving upward to serve the full range of needs in the marketplace, a PC competitor could thus be in a position to increase market share, price realization, and margins.

However, the difference in the rate of performance improvement between what consumers expect and what engineers deliver inevitably leads industry players to overshoot the market. In other words, they provide more PC performance than even high-end consumers need or are willing to pay for. When this happens, incumbents begin to experience a slowdown in demand and increased pressure on price realization and margins. Fewer and fewer consumers value the new performance thresholds.

To see the consequences of an overshot market, consider the computer that you currently own. If you learned that the manufacturer of your PC just came out with a new model that is 50 percent faster, has twice the storage capacity, and sells for $100 less than what you paid for your current computer, would you feel compelled to rush out and buy the improved new product? I suspect not; the reason being that most consumers believe the performance of their PC is sufficient to meet their current needs. The consequences of overshooting the market are already evident in the PC sector: the average selling price and unit sales of PCs have been declining steadily for many years.39

When incumbent players overshoot the needs of a significant segment of the market, it opens the door to disruptive entrants who recognize the opportunity to appeal to overserved consumers with simpler, cheaper products. In the PC market, this led to the introduction of netbooks. In 2007, Asus released the first lightweight netbook, with a small screen, a cramped keyboard, and a slow processor. Despite these limitations, it was more portable than the commonly available Windows laptops at the time and was less than half the price of better-featured laptops on the market. Competing netbook models quickly followed from other players at prices below $250, and netbook sales became the fastest-growing segment of the PC market over the next three years, unlocking PC demand from consumers who had previously been priced out of the market.

Once a low-end disruptive technology like netbooks is introduced, it tends to experience rapid sustaining technology improvements, expanding its basis of appeal beyond the least demanding consumers. As shown by line D in figure 11.9, if a disruptive technology improves enough over time to serve even the expectations of high-end consumers, a category can become fully disrupted, wiping out most of the original industry incumbents whose products are generally no longer deemed competitive. This is exactly what happened many times in the computer industry: successive, disruptive waves of new technology transformed the industry from a predominant focus on mainframes, to minicomputers, to PCs, to mobile computing devices. Each disruptive transformation wiped out most of the incumbents wedded to the prior technology, while creating enormous growth opportunities for disruptive entrants. As it turned out, netbooks did not fully disrupt the PC industry; mobile computing became an even more disruptive influence.

The marketplace dynamics described in the previous few pages have broad-based implications for business strategy. As Clayton Christensen has noted, a company that finds itself in an overshot market can’t win by staying the course. Either entrants will steal its customers or commoditization will steal its profits.40

I’ve described such scenarios many times throughout this book. For instance, in Red Ocean marketplaces, companies in a mature industry compete on the same terms for the same customers in a slow-growth, low-profit environment. Kim and Mauborgne cited overshot markets in the airline, fitness center, and pharmaceutical industries.41 Competitors get caught in tit-for-tat product replication and augmentation, causing categories as a whole to lose meaningful differentiation. Youngme Moon’s reference to the “bed wars” in the hotel industry and my examples of loss of distinctiveness in the wine, sock, and household cleaning product categories provide additional examples.42

Given such widespread industry disruption, a pivotal question arises: why do executives so often mire themselves in such dire circumstances? Ironically, the reason that companies so often overshoot their markets is that managers repeatedly do what good managers are supposed to do, like listening and responding to the needs of their best customers. A company’s highest-spending and most sophisticated customers are the ones most likely to clamor for (if not necessarily be willing to pay for) better product performance. Since most companies are understandably motivated to respond to power users who are willing to pay the highest prices for top performance, competitive dynamics drives most executives to overshoot mainstream consumer needs.

Low-end disruptive technologies represent one way to avoid this feature–function arms race and create profitable growth by appealing to overserved consumers. Low-end disruptive entries are initially inferior to mainstream products based on traditional performance metrics. However, they deliver a more appealing value proposition to many price-sensitive buyers. For example, the first netbooks performed well below the standards of state-of-the art PCs when they were first introduced, but at a strikingly lower price. Similarly, online travel agency (OTA) sites initially lacked the breadth of coverage and depth of expertise offered by the traditional travel agent industry. Instead, they provided greater convenience, significantly lower fees, and the availability of peer reviews. Over time, the performance of OTAs improved rapidly, and wound up wiping out most traditional travel agencies.

Another way to avoid the consequences of stalemated competition in overserved markets is to pursue new-market disruptive technologies, which attract nonconsumers by focusing on entirely different performance attributes that were previously ignored by industry incumbents. For example, for-profit higher education providers chose not to compete directly against existing colleges on prestige or price. Instead, these new-market disruptors focused on a different attribute: flexible access to education, which allowed students to maintain their jobs while pursuing a college degree. As such, for-profit colleges unlocked a huge untapped, addressable market that had previously been ignored by traditional colleges and universities.

Walk-in medical clinics also unlocked untapped demand by providing more convenient and less expensive access to routine medical services than was traditionally offered by the medical profession. For decades, a patient’s only choice to deal with a health issue was to schedule a doctor’s appointment during normal business hours or to go to a hospital emergency room. Given the inconvenience and cost associated with either of these alternatives, many consumer ailments simply went untreated, creating a significant untapped opportunity for new-market disruptors. Walk-in medical clinics, located in pharmacies, grocery stores, and other major retailers, now offer access to a wide range of affordable routine medical services seven days a week, including evening hours. By 2015, MinuteClinic (CVS), Healthcare Clinic (Walgreens), and The Clinic at Walmart, among others, were operating more than three thousand walk-in medical facilities in what has become one of the fastest growing sectors of the health-care industry.43

As a final example of new-market disruptive technologies, Apple’s highly successful iPad (launched in 2010) disrupted the PC industry by appealing to a previously untapped consumer demand for mobile computing and content streaming. As such, Apple expanded the size of the market for computing devices, rather than simply trying to steal market share from existing PC players.

While Christensen is widely acclaimed for introducing a groundbreaking business theory, he has recently been criticized for being too narrowly focused on only two forms of disruptive technologies, low end and new market, which both focus on overserved customers.44 In fact, as shown in table 11.10, there are four types of disruptive technologies that can fundamentally transform the competitive dynamics of an industry.

TABLE 11.10

Different Types of Disruptive Technologies

| Disruptive Technology Type |

Customer Target |

Product Characteristics |

Examples |

| Low End |

Overserved consumers |

Current products are considerably more sophisticated and expensive than many consumers need. |

Southwest Airlines

Netbooks |

| New Market |

Nonconsumers |

Remove a constraint that previously prevented consumers from participating in the market (e.g., where or when products could be consumed, usually at a more affordable price). |

Walk-in Medical Clinics

Online Higher Education |

| High End |

Underserved consumers |

Breakthrough product performance at a premium price. |

iPod

FedEx |

| Big Bang |

Mass market |

Dramatic improvements in product performance and lower prices than current products. |

Google Maps

Uber |

In addition to low-end and new-market disruptors, there is a third way to break the no-win stalemate of commoditized markets; by exploiting a technological breakthrough, enabling high-end disruptive technology providers to dramatically improve current performance levels. Such products appeal to consumers who value and are willing to pay a premium for demonstratively superior product performance. Examples in this category include Apple’s original iPod and FedEx’s overnight package delivery service. Over time, high-end disruptors often seek to expand the size of their addressable market by steadily lowering prices to penetrate the mainstream consumer market.

A current example of a high-end disruptive technology that is rapidly expanding the size of an industry’s addressable market is the e-bike. One player in this emerging market, Pedego, focuses on baby boomers seeking recreation or wanting to keep up with their grandkids. As Pedego’s CEO noted, “99 percent of our customers would never have purchased another bike in their lifetime, if not for us.”45 The price of many e-bikes on the market in 2015 exceeds $2,000, but similar to the trajectory of other high-end disruptive technologies, e-bike prices are expected to decline in the years ahead, fueling greater market adoption.

A fourth form of highly disruptive technology has emerged in recent years that offers vastly superior performance and lower prices over current products. That’s precisely the compelling value proposition of “big bang” disruptors that can overwhelm stable businesses very rapidly.46

For example, the integrated software and hardware capabilities of smartphones are creating big-bang disruptions in a number of product categories, including cameras, pagers, wristwatches, maps, books, travel guides, flashlights, home telephones, dictation recorders, cash registers, alarm clocks, answering machines, yellow pages, wallets, keys, phrase books, transistor radios, personal digital assistants, remote controls, newspapers and magazines, directory assistance, restaurant guides, and pocket calculators.

The taxi industry is currently experiencing the challenges of big-bang disruption, as many riders perceive Uber as offering better service and lower fares. As a measure of the explosive growth potential of big-bang disruption, Uber achieved a valuation of $50 billion within five years, becoming the fastest company ever to reach such a milestone.47

Given the huge potential of successful disruptive technologies, why don’t more companies disrupt themselves? The consequences of ignoring disruption are grave. Every company is subject to product life cycles that eventually erode the customer appeal, sales, and profitability of products in their business portfolio. Companies like Apple and Amazon have continuously identified and exploited opportunities to disrupt themselves before competition beats them to it, and as a result have achieved the rare feat of sustained profitable growth.48 Yet continuous disruptive renewal remains the exception, rather than the rule, for a number of reasons.

Customer Focus

As already noted, most companies tend to predominantly focus on the needs of their best customers, leading to continuous sustaining-technology improvements for their current products, rather than disruptive technologies that expand market reach.

Competitor Focus

In the same vein, the tendency of large market incumbents is to look over their shoulder at their traditional competitors. If you’re an established player in an industry, you already have a large revenue base, and the fastest way to grow is to steal customers from your closest competitors. But your archenemies are similarly motivated, which reinforces feature–function arms races that open the door for low-end and new-market disruptive entrants. For example, in the luxury automobile market, the Big Three German luxury carmakers—BMW, Mercedes-Benz, and Audi—were so focused on matching each other’s product offerings that they ignored the opportunity identified by newcomer Tesla to usher in a new generation of high-performance electric cars. Similarly, Boeing and Airbus have been so absorbed in shadowing each other’s jumbo-jet airliner development programs that both missed the opportunity to pursue the rapidly growing regional jet sector, now dominated by Embraer and Bombardier.

Resource Constraints

A third barrier to disruptive technology development is the allocation of corporate resources. Ironically, sustaining technology improvements to existing products often require higher levels of R&D investment than the launch of disruptive technologies. The reason for this is that continuous improvements to mature products often require sophisticated new technologies to push the envelope of achievable performance. In contrast, low-end and new-market disruptive technologies often rely on mashups of off-the-shelf components and low-cost business-model innovations that are cheaper to realize.

In the health-care sector, for example, the leading practitioners of sophisticated CT scanners and MRI equipment—GE, Siemens, and Philips—invested heavily over many years to improve the image quality and accuracy of their advanced diagnostic products. But for many applications, ultrasound (a low-end disruptive technology) provides adequate diagnostic accuracy at a far lower cost. Ultrasound equipment is relatively inexpensive, simpler to use, and allows less-skilled professionals to provide diagnostic services in more affordable, accessible settings. Since GE, Siemens, and Philips were so heavily invested in sophisticated product-development programs, none of them incorporated low-cost ultrasound solutions into their medical-equipment product portfolios for many years, until more recent industry acquisitions.

Similar industry dynamics also played out in the markets for PCs, cameras, photocopiers, steel mills, and many others, where incumbent market leaders continued to invest heavily in sustaining technology improvements, while ignoring the opportunity and need to transition to new disruptive technologies.49

Organizational Barriers

A number of common organizational behaviors impede corporate entrepreneurship and obstruct the development of disruptive technologies. For example, monetary incentives typically reward employees who meet short-term business-performance targets, understandably keeping most managers focused on current revenue generators, rather than long-term opportunities for game-changing disruptive technologies. Moreover, most corporations tend to be intolerant of failure, lacking the patience to nurture disruptive product development that can take years before yielding material financial results. Under such circumstances, many would-be intrapreneurs are reluctant to risk their own compensation and career development by committing to uncertain disruptive product initiatives. Finally, new disruptive technologies that threaten to cannibalize a company’s current products usually engender fierce internal opposition.

In addition to these factors, the biggest barriers to disruptive technology development in many companies are management mindsets that are ill-suited to promoting an entrepreneurial spirit of continuous innovation. There are four common dysfunctional management mindsets that warrant particular attention.

Pride in Current Product Technologies