CHAPTER 8

The People Have Lost Their Pep

The Great Recession is the twenty-first century’s bubonic plague. If the Great Depression was anything to go by, there were inevitably going to be consequences from the crisis that started in the U.S. housing market and just spread around the world like an economic pandemic. The Great Crash of 1929 was followed by what Keynes called the long, dragging conditions of semi-slump. Unemployment in the 1930s hit 25 percent, living standards fell, and right-wing populist movements emerged in Austria, Germany, and Italy and in many other countries. That led to war. Rearmament spending in the UK at the end of the 1930s and war spending itself brought full employment. Women workers were central to the war effort.

John M. Barry, in his classic The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, documents how the 1918 flu pandemic “reached everywhere … even a mild to moderate pandemic is something to worry about” (453, 456). Older people had built up antibodies to the flu from previous milder infections; it mostly impacted the young who had no immunity. The later the disease attacked the lesser the blow (372).

Young men infected with the disease joined the armed forces and were not isolated, and the flu spread as they went from camp to camp, troop ship to troop ship. Then they went back to their hometowns and passed the disease on to women. Soldiers were posted around the world by generals who refused to isolate them, and the disease spread even wider. The most conservative estimate is that it killed twenty million people. “New York City was panicking, terrified” (276). The spreading pandemic was driven by ignorance and the failure of public (health) authorities. There were too few nurses, and “the federal government was giving no guidance that a reasoning person could credit. Few local governments did better. They left a vacuum. Fear filled it” (410, 333). In the end science prevailed. But war and the flu especially impacted men.

Barry reported that Cincinnati Health Commissioner Dr. William Peters told the American Public Health Association meeting almost a year after the epidemic that phrases like “I am not feeling right,” “I don’t have my usual pep,” and “I am all in since I had the flu” had become commonplace (392).

Months after recovering from the flu, Dartmouth’s Robert Frost wondered, Barry reported, “what bones are they that rub together so unpleasantly in the middle of extreme emaciation …? I don’t know whether or not I’m strong enough to write a letter yet.”1

Barry’s final three paragraphs in his magnum opus seem especially apt.

So, the final lesson of 1918, a simple one yet one most difficult to execute is that those who occupy positions of authority must lessen the panic that can alienate all within a society. Society cannot function if it is every man for himself.

By definition society cannot survive that. Those in authority must retain the public’s trust. The way to do that is to distort nothing, to put the best face on nothing, to try to manipulate no one. Lincoln said that first, and best.

A leader must make whatever horror exists concrete. Only then will people be able to break it apart. (461)

In 2018 many people have lost their “usual pep.” The effects of the Great Recession and the long, dragging conditions of semi-slump and subnormal prosperity that follow have lingered.

The Great Recession of 2008 and 2009 started in the U.S. housing market and spread, just like the bubonic plague, to the rest of the advanced world and beyond. People lost their houses, their jobs, and their pensions. Many just lost hope. Thankfully the authorities put in fiscal and monetary stimulus in 2008 and 2009 that prevented the unemployment rates in most countries from reaching the levels seen in the 1930s. The exceptions were Greece and Spain, which saw rates rise to interwar levels with youth unemployment rates even higher. Recovery started in 2009 and it seemed that the battle had been won.

Sadly, though, the imposition of austerity from 2010 onward meant that there was going to be slow progress from there. Policymakers found Keynes for a short while and then ditched him all in the name of debt. GDP growth since then has been weak and living standards have been hit hard. The UK recovery was the slowest in three hundred years. Simon Wren-Lewis was absolutely right when he said “without austerity in the UK we could have had a recovery that was strong and long” (2018, 285). In a tweet to me Simon argued, and I agree, “I just don’t think enough people realise how different everything would have been with strong and long recoveries.” I asked him if he thought that recovery had been long and weak and whether he thought austerity led to Brexit. In a subsequent tweet he replied, “In the US yes. In the UK it has been more standstill, weak and now very weak. In the Eurozone there was of course a double dip recession. Given the narrow margin of victory, probably austerity did help cause Brexit.” The United States has an employment rate that is 3 percentage points below its level at the start of recession.

Public spending cuts hit the weak, the disabled, and the vulnerable. Coal jobs, construction jobs, manufacturing jobs were gone, and nothing replaced them especially outside the big cities. Flyover America did badly while the exam-taking classes prospered. It is clear there was going to be a price to pay for too many years of hurt. In the United States the real earnings of workers in 2018 were still 10 percent below those of their parents in 1973. The American Dream is certainly broken and maybe gone.

In this chapter I look at the consequences of the Great Recession that hit in 2008 and the lost decade that followed. The first piece of evidence we look at suggests that people are in pain. Their mental and physical health has deteriorated, and life expectancy in the United States and the UK has fallen. There has been a rise in what Anne Case and Angus Deaton (2017b) have called “deaths of despair” in the United States, and an exploding opioid crisis shows no signs of abating. Of particular concern are the bad outcomes we observe for less-educated prime-age adults, especially whites, in the United States. This includes increases in deaths from drug overdoses, liver disease, and suicide.

“When people are in pain they need to find someone to blame. Immigrants fit the bill, and that is the subject of chapter 9. Pain has inevitably had an impact on politics, which is the subject of chapter 10. Recessions and long periods of semi-slump, of subnormal prosperity, have consequences. It remains unclear the extent to which the recession caused these changes. More likely it exposed deep underlying wounds. The people most affected by these changes disproportionately voted for Trump, who offered hope from despair.

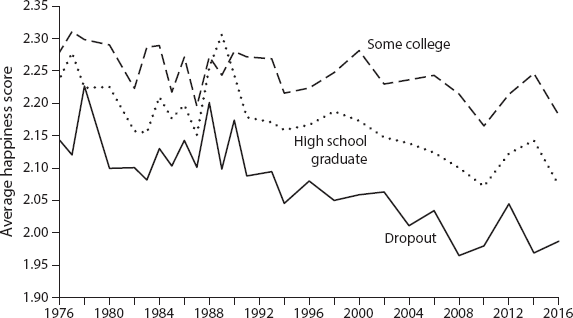

Figure 8.1. Declining happiness in the United States from the General Social Survey, 1976–2016. The figure plots average happiness “scores” based on answers to the question, “Taken all together, how would you say things are these days—would you say that you are very happy (= 3), pretty happy (= 2), or not too happy (= 1)?” (GSS question 157). Source: Blanchflower and Oswald 2018.

Over the last few decades measured happiness has fallen in the United States. Figure 8.1 illustrates; it shows the decline in happiness by education groups using self-reported happiness data from the General Social Survey. It measures responses to the question, “Taken all together, how would you say things are these days—would you say that you are very happy (= 3), pretty happy (= 2), or not too happy (= 1)?” In 2016, the average happiness score was 2.12 versus 2.14 in 1972 and 2.21 in 2000. This is especially notable among high school dropouts.

Other countries have seen rising levels of happiness. For example, in the UK happiness has risen, using a scale of 1–10, from 7.3 in the period April 2011—March 2012 to 7.5 between July 2016 and June 2017.2 Germany saw a rise from 2.9 to 3.2 in 2017. UK life satisfaction over this period rose from 3.2 in 2006 to 3.4 in 2017. France saw flat life satisfaction on a 4-point scale, using Eurobarometer surveys, at 3.0. Italy saw a fall—from 2.9 to 2.7, as did Greece from 2.71 to 2.23—but these countries all had high levels of unemployment. According to Helliwell et al. (2019) writing in the 2019 World Happiness Report, the United States ranks nineteenth in the world happiness rankings, ahead of the Czech Republic (twentieth) and the United Arab Emirates (twenty-first). Germany is seventeenth, the UK fifteenth, Canada ninth. The top seven countries, in order, were Finland, Denmark, Norway, Iceland, Netherlands, Switzerland, and Sweden, where the distribution of income is relatively flat. The United States looks different.

Pain, Depression, and Despair

Pain in the United States is especially high compared with other countries, and its incidence has risen sharply over time. One-quarter of patients seen in primary care settings in the United States say they suffer from pain so intense that it interferes with the activities of daily living. There has also been a dramatic rise in opioid prescriptions in the United States but not elsewhere. Sadly, the evidence shows that opioids are ineffective in treating pain; it is better to take Advil or Tylenol. Plus, opioids are highly addictive; withdrawal is extremely difficult.

Dr. Donald Teater of the National Safety Council, founded in 1918 and chartered by Congress, examined the evidence on the effectiveness of opiates and non-opiates in treating pain. He concluded, “Opioids have been used for thousands of years in the treatment of pain and mental illness. Essentially everyone believes that opioids are powerful pain relievers. However, recent studies have shown that taking acetaminophen and ibuprofen together is actually more effective in treating pain.” Teater cites a couple of review articles with supporting evidence. First, Moore and Hersh (2013, 898) in the Journal of the American Dental Association addressed the treatment of dental pain following wisdom tooth extraction and concluded that 325 milligrams of acetaminophen taken with 200 milligrams of ibuprofen provides better pain relief than oral opioids. Second, a review article in the Spine Journal (Lewis et al. 2013) looked at multiple treatment options for sciatica (back pain with a pinched nerve with symptoms radiating down one leg) and found that non-opioid medications provided some positive global effect on the treatment of the disorder, while the opioids did not.

My endodontists have a similar view about managing dental pain (Blicher and Pryles 2017). They only prescribe Advil after root canals, trust me! Their view is that opioids are not in fact the best means to manage dental pain: “800mg of ibuprofen is demonstrably more effective in managing severe dental pain than other available prescription analgesics, including narcotic compounds. Furthermore, the combination of ibuprofen (Advil) and acetaminophen (Tylenol) offers greater pain relief than either medication alone and significantly more than the combination of acetaminophen and opioid medication both following endodontic treatment and third molar extraction” (2017, 56). In his brilliant book Sam Quinones noted that in the last decade or so entire families grew up on Social Security Disability Insurance (SSI), which paid only a few hundred dollars a month. SSI had a major benefit: it came with a Medicaid card and that made all the difference when Oxycontin arrived. Having a Medicaid card, Quinones pointed out, allowed you to get a monthly supply of pills worth several thousand dollars. With Oxycontin, “a Medicaid card became [a license] to print money” (2015, 211). A Medicaid card provides health insurance, and part of that insurance pays for medicine, whatever pills the doctor determines appropriate. For a three-dollar Medicaid co-pay, an addict got pills priced at a thousand dollars with a street value of ten thousand dollars: “Some of the most potent early vectors were newly christened junkies from eastern Kentucky, where coal mines were closing, and SSI and Medicaid cards sustained life” (Quinones 2015, 242).

Ethicist Travis Rieder told his own story of addiction after a devastating injury. Rieder had a serious motorcycle accident, necessitating multiple surgeries. He documents the heart-rending nightmare of trying to deal with withdrawal from the pain killers he was given. The doctors just kept prescribing.

Physicians are the gatekeepers of medication for a reason: They are supposed to protect their patients from the harm that could come from unregulated use of those medications. Physicians, public health officials, and even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tell us that we are in the midst of an “opioid epidemic,” due to the incredible addictive power of these drugs. Yet when people become addicted to painkillers after suffering a trauma, the best advice they might get from physicians when coping with withdrawal is to go back on it to feel better. Can we really do no better than that? (Rieder 2017)

In private communication with me, Travis Rieder noted that the United States has 5 percent of the global population and 80 percent of its opioid use. As we shall see, this is much less of a phenomenon in Europe. In the United States, there were over 62,000 deaths due to opioid overdose in 2017, which is more than the number of people killed in homicides or auto accidents. The states with high drug-poisoning deaths, obesity rates, and low happiness levels disproportionately voted for Trump. West Virginia ranks worst on almost all dimensions. Why is this not happening in the UK? One reason is that prescription medicines cannot be advertised directly to the public. My doctor friends tell me they think the big reason for the difference is that British patients can’t shop doctors if their general practitioner refuses to oblige with a prescription whereas they can in the United States.

Andrew Oswald and I (2004a, 2008, 2009, 2016, 2017) have found that those in middle age tend to suffer more than other age groups when it comes to such measures as happiness, enjoyment, pain, the number of “bad mental health days,” worry, stress, fatigue, depression, sadness, and anxiety. The use of antidepressants peaks in middle age, as does the difficulty in paying bills and the incidence of obesity. In the United States, the number of bad mental health days is especially high and peaks in middle age, particularly for the nonworking, least educated.

The rise in the prevalence of pain has been apparent for some time, and its incidence is highest among those with less education. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) reported (2011) a marked rise in pain between 2000 and 2009, especially for those ages 45–64 and for white non-Hispanics. The IOM found that in 2009 there was little difference in knee, shoulder, neck, finger, and hip pain between those with less than a high school diploma and those with some college. But there were marked differences in the incidence of low back pain and severe headaches between the least and most educated groups.

Non-Hispanic whites had a higher incidence of back and neck pain than other racial groups.3 Older adults, women, Caucasians, and people who did not graduate from high school were all more likely to report frequent or constant pain.4 The prevalence of chronic, impairing lower-back pain in the United States has risen significantly over time.5 Increases were seen for all adult age strata (men and women, white and black).

Data from England also suggest a rise in back pain,6 although data from Finland7 and Germany8 showed little change. It is unclear why there are such marked differences across countries or whether the differences are real and there has been an increase in back pain in the United States and the UK just in self-reports.

To try to put the high levels of pain observed in the United States into perspective, Andrew Oswald and I (Blanchflower and Oswald, forthcoming) examined microdata from the 2011 International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), which is a survey of thirty-two countries. Respondents in the United States reported the most pain. Respondents were asked, “How often during the past 4 weeks have you had bodily aches or pains? Never (= 1); seldom (= 2); sometimes (= 3); often (= 4); very often (= 5); or can’t choose (set to missing)?” The proportions saying “often” or “very often” were 22 percent for France; 21 percent in Germany; 22 percent in Italy and the Netherlands; 17 percent in Spain; 28 percent in Great Britain; and 32 percent in the United States.9

Case and Deaton (2015) examined data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey and looked at changes between the mean for 2011–13 and 1997–99 for those ages 45–54 with regard to neck pain, facial pain, chronic joint pain, and sciatica, all of which showed significant increases. One in three white non-Hispanics aged 45–54 reported chronic joint pain in the 2011–13 period. This rise in pain is correlated with the rise in pain medication prescriptions. They found that the prevalence of pain was highest for those ages 35–54 with less than a high school education.

The U.S. 2015 National Health Interview Survey also reported on levels of pain, including lower-back, neck, and face pain. It turns out that lower-back pain is especially prevalent with a mean of 30 percent, compared with 16 percent for neck pain and 4 percent for face pain. It is notable that lower-back pain varies by education and is especially high for dropouts (35%) compared with high school graduates (31%) and those with some college (28%).

Nahin (2015) reported that a remarkable 126 million or 56 percent of American adults experienced some type of pain in 2012. Of these, 20 percent had pain daily (i.e., chronic pain). Women were more likely than men to have such pain. White non-Hispanics had the highest incidence of pain versus other minorities. In both sexes, lower-back pain was most common. Krueger (2016) found that about half of prime-age men who are not in the U.S. labor force (NILF) may have a serious health condition that is a barrier to work. Nearly half of prime-age NILF men, he found, take pain medication daily, and in nearly two-thirds of cases they take prescription pain medication. The extent of the feelings of bodily pain is an obvious problem given that Muhuri and coauthors (2013) document that it leads to heroin use.

Tsang and coauthors (2008) found that the prevalence of any chronic pain condition was higher among women than men in both developed and developing countries. The prevalence of any chronic pain condition in the preceding twelve months in developed countries was highest in France (50%), followed by Italy (46%) and the United States (44%), with Germany (32%) and Japan the lowest (28%).

Diener and Chan (2011) show that there is evidence in the literature of a relation between pain and well-being. They cite four intriguing papers. Pressman and Cohen (2005) discovered that positive emotions, by which they mean happiness, joy, excitement, enthusiasm, and contentment, are related to lower pain and greater tolerance of pain. They argue there is considerable evidence linking positive emotions to reports of fewer symptoms, less pain, and better health. In a meta-analysis, Ryan Howell et al. (2007) reported that there was a strong association between measures of well-being and pain tolerance. Tang and coauthors (2008) found that, in patients with chronic back pain, experimentally induced negative mood increases self-reported pain and decreases tolerance for a pain-relevant task, with positive mood having the opposite effect.

Depression, feelings of hopelessness, and stress are also on the rise in the United States and elsewhere. Data for 2009–12 show that 7.6 percent of Americans aged 12 and over had depression in the two weeks prior to being interviewed.10 This was up from 5.4 percent during the period 2005–6. Consistent with these data, table 8.1 reports the extent to which antidepressants for depression and related disorders were used in the previous thirty days in the United States, in 1999–2002 and 2009–12. There has been a sharp increase in the prevalence of antidepressant use for all ages and for both men and women.11

Assari and Lankarani (2016) found that depressive symptoms accompany more hopelessness among U.S. whites than blacks. Hopelessness, they found, positively correlates with depression and suicidality and negatively correlates with happiness. Whites are less resilient, had higher suicide rates, and reported higher levels of pain in their daily lives than blacks did. This finding may explain, they suggest, why blacks with depression have a lower tendency to commit suicide.

Graham and Pinto (2016) found the odds of experiencing stress were highest among poor whites, who were 9 percent more likely to have stress than middle-class whites. Poor blacks were half as likely to experience stress. They also found that reported pain is higher in rural areas than in urban areas, where optimism about future life satisfaction is significantly lower.

A new article by Goldman and colleagues (2018) investigates whether the psychological health of Americans has worsened over time, as suggested by the “deaths of despair” narrative, linking rising mortality in midlife to drugs, alcohol, and suicide. The results show that distress is not just a midlife phenomenon but a scenario plaguing disadvantaged Americans across the life course. They investigated whether mental health had deteriorated since the mid-1990s, a time period known for increased opioid use and rising mortality from suicide, drugs, and alcohol. They used data from two cross-sectional waves of the Midlife in the U.S. Study (MIDUS) to assess trends in psychological distress and well-being. MIDUS conducted interviews with national samples of adults in 1995 and 1996 and another sample again between 2011 and 2014, which closely spans the period of rising substance abuse. The researchers looked at measures of distress and well-being to better capture overall mental health.

Table 8.1. Antidepressants (Depression and Related Disorders) Used in the Past 30 Days, United States (%)

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics,” table 80, “Health, United States, 2015,” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf.

Distress was represented by two measures: depression and what’s called “negative affect,” which includes reports of sadness, hopelessness, and worthlessness. Well-being was assessed by four measures that reflect emotions such as happiness, fulfillment, life satisfaction, and meaning in life. The results revealed the influence of socioeconomic status. In both time periods studied, disadvantaged Americans reported higher levels of distress and lower levels of well-being compared to those of higher socioeconomic status. Importantly, between the two different waves of people studied, distress increased substantially among disadvantaged Americans, while those of higher socioeconomic status saw less change and even improvement.

In the UK, the report “Prescriptions Dispensed in the Community” for 2005–15 shows that the number of antidepressant items prescribed and dispensed in England has more than doubled in the last decade.12 In 2015, there were 61 million antidepressant items prescribed—32 million more than in 2005 and 3.9 million more than in 2014. Between 2015 and 2016 the number of prescriptions for antidepressants rose 6 percent, from 61 million to 65 million.13 The UK government noted this was the biggest single growth rate of any prescription medication.

Vandoros and coauthors (2018) examined whether the number of prescriptions for antidepressants in the UK increased after the Brexit referendum, benchmarking them against other drug classes. They used general practitioners’ prescribing data to compile the number of defined daily doses per capita every month in each of the 326 voting areas in England over the period 2011–16. They found that antidepressant prescribing continued to increase after the referendum but at a slower pace. Therapeutic classes used as controls showed a decrease. The authors argue that “major political and economic shocks may have unanticipated consequences on population health, even before they directly affect employment, business or migration patterns” (2018, 7).

David Bell and I (2018c) examined data from the UK Labour Force Surveys where respondents report on whether they have a health problem and if so what it is. It is possible to report more than one, but respondents determine which problem is the main one. One of the options was “mental illness, or suffers from phobia, panics, or other nervous disorders.” We found that there was no evidence of any rise over time in these serious forms of mental ill health. We did find evidence of a rise in the proportion who reported having “depressions, bad nerves or anxiety” as their main health problem. The incidence was broadly flat from 2004 through 2010 but then more than doubled between 2010 and 2018 with the implementation of austerity.14

The consumption of antidepressants around the world has been little studied in the economics literature.15 One article does show that job loss caused by plant closure leads to greater antidepressant consumption; another argues that an increase in sales of one antidepressant—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—by one pill per capita produces a large reduction (of 5%) in a country’s suicide rate. A further exception in the wider literature examines data on the timing of people’s Google searches on antidepressants’ side effects.16 For Europe, Knapp et al. (2007) document a near-doubling of antidepressant consumption in the ten years from 1990 to 2000.

Recent data on antidepressant medication usage from the OECD reveal a continuing upward trend across all countries. Antidepressant consumption in daily doses per thousand population rose, in the UK, for example, from 20 in 1995 to 87 in 2014. This rate, in 2014, was higher than in France (50 in 2008), Italy (47), or Germany (55).

Well-Being, Health, Healing, and Longevity

This all matters. It turns out that happy people heal faster. A meta-analysis assessed the impact of stress on the healing of a variety of wound types in different contexts, including acute and chronic clinical wounds, experimentally created punch biopsy and blister wounds, and minor damage to the skin caused by tape stripping.17 The results reveal a robust negative relationship whereby stress is associated with the impairment of healing and disregulation of biomarkers associated with wound healing. This is broadly consistent across a variety of clinical and experimental, acute and chronic wound types in cutaneous and mucosal tissue. The relationship was evident across different measures of stress.

Later work also concluded that evidence from experimental and clinical models of wound healing indicate that psychological stress leads to clinically relevant delays in wound healing.18 Dental students who were given a standardized wound healed more quickly during the summer than during final exams.19 It has also been found that surgical patients heal more quickly if they report high levels of life satisfaction.20

Hemingway and Marmot (1990) found that depression and anxiety predicted coronary heart disease in healthy people. Analogously, Zaninotto, Wardle, and Steptoe (2016) studied a national representative sample of English men and women age 50 and over and examined measures of enjoyment of life. Subsequent mortality was inversely correlated with the number of occasions on which participants reported high enjoyment of life. Chida and Steptoe (2008) conducted a meta-analysis and found that positive psychological well-being was related to lower mortality. Joy, happiness, and energy, as well as life satisfaction, hopefulness, optimism, and a sense of humor, lowered the risk of mortality.

Obesity is also correlated with depression, but the direction of causation is not obvious.21 Obesity makes people depressed, or depression makes people eat, which causes depression or possibly both in a downward spiral. Luppino et al. (2010) addressed this issue with a meta-analysis of studies using longitudinal data and examined whether depression is predictive of the development of overweight and obesity and, in turn, whether overweight and obesity are predictive of the development of depression. Importantly they found the direction of causation ran from depression to obesity; depression was found to be predictive of developing obesity. This was especially strong in American studies, where the average BMI is higher than in other countries.

Obesity, depression, and pain seem to go together. Obesity has trended up over time, in the United States, from 30.7 percent in 1999–2000 to 37.7 percent in 2013–14.22 State rankings show that West Virginia has the highest rate of obesity, as well as the highest incidence of drug-poisoning deaths of any state according to the NHCS. The ten states with the highest obesity rates voted for Trump.23 Pratt and Brody (2014b) found that 53 percent of U.S. adults with depression were obese. Fifty-five percent of adults who were taking antidepressant medication, but still reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms, were obese.

Relative things also appear to matter for obesity. The United States has far and away the highest BMI of any OECD country. According to the OECD, 40 percent of the adult population in 2016 in the United States was obese, measured by whether their BMI is 30 or over, which is the highest in the OECD. This compares with 28 percent in Canada; 26 percent in the UK; 24 percent in Germany; 17 percent in France and Spain; and 4 percent in Japan.24 Obesity levels are one indicator of poor physical and mental health.

There Is Growing Evidence of a Midlife Crisis for the Jobless

A good deal of the evidence in this chapter suggests there is an ongoing midlife crisis. This is especially apparent for white, less-educated people.

Happiness is U-shaped with regard to age while unhappiness has the opposite shape. The rates of depression and antidepressant usage according to age have an inverted U-shape as do the incidence of obesity and pain (including neck and lower-back) and the rates of fatigue and stress. It also turns out that views on many other variables, including household finances and the state of the economy, have a U-shape according to age.

Pain is highest in middle age. Drug-poisoning deaths are also highest among those in middle age. There was an especially large jump in the U.S. suicide rate of white non-Hispanic men ages 45–64 between 1999 and 2014. Deaths of despair, due to drug and alcohol poisoning and suicide, are up in the United States, particularly for white non-Hispanics with low education levels, but they are not for Hispanics, Asians, or blacks.

In a 2008 article Andrew Oswald and I showed that happiness is U-shaped with regard to age in seventy-two countries around the world.25 In many countries, the U-shape can be found without any control variables. The United States does not have a well-being U-shape in age until control variables are included.26

In a 2017 paper Andrew and I reexamined the U-shape pattern for happiness in six data sets. These include the UK with data on life satisfaction, happiness, and worthwhileness from the Well-Being Supplement to the Labour Force Survey for 2011–15, as well as data from the EU28 from the Eurobarometer Surveys and the European Social Surveys from 2002–14, plus the multicountry International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) for 2012. All six surveys, for around seventy countries, show a convincing U-shape. Happiness also rises with income level. Those with the lowest incomes are the least happy. The unemployed are especially unhappy.

Andrew Clark and I have examined the unexpected finding in the happiness literature that children lower happiness. In a study of a million Europeans we find that children actually raise happiness once account is taken of the difficulty parents have in paying their bills.

In the 2016 European Social Survey taken across eighteen European countries, approximately 35,000 respondents were asked about their life satisfaction as well as their satisfaction with the economy; the national government; the way democracy works in their country; the state of education; and the state of health services in their country. Answers were recorded on a 1–10 scale where 1 = extremely dissatisfied and 10 = extremely satisfied. In all six cases satisfaction followed a U-shape in age, all of which had satisfaction levels minimizing around age 55.27

Just to extend the idea that the U-shape in well-being broadens beyond simply happiness and life satisfaction, there are also data in a large number of Eurobarometer surveys on other topics. As an example, a survey taken in May 2017 asked about life satisfaction: “On the whole, are you very satisfied (= 4), fairly satisfied (= 3), not very satisfied (= 2), or not at all satisfied (= 1) with the life you lead?” The approximately 33,000 respondents in the survey were also asked: “How would you judge the current state of a) the situation of the national economy, b) the financial situation of your household, c) the employment situation in your country, d) the provision of public services in your country?” Responses were very good (= 4), rather good (= 3), rather bad (= 2), and bad (= 1). In every case responses followed a U-shape in age, with a low point in age ranging from 44 to 56.28

A Eurobarometer survey conducted between February and March 2010 asked respondents in thirty European countries the following question: “How often over the past four weeks did you feel a) tired and b) worn out?” Responses were never (= 1), rarely (= 2), sometimes (= 3), most of the time (= 4), and all the time (= 5). Tiredness and being worn out both maximize in the mid-40s and then fall away. There was also a question in the survey about depression, which also had an inverted U-shape in age.

Graham and Pozuelo (2017) found that stress had an inverted U-shape in age in 34 out of 46 countries they studied, including Germany, the UK, and the United States. The question used was: “Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about stress?” A recent U.S. study using Gallup Healthways data on over 1.5 million respondents analyzed a question asking about stress felt the previous day and found that ratings of daily, perceived stressfulness rose from age 20 through to about age 50, followed by a precipitous decline after age 70.29 Data from the American Time Use Survey also confirmed that the level of stress rose to around age 54 and then declined.

Another study using the Gallup Healthways data file reported results on the relationship between stress and age. The study showed there was a correlation between stress and age in high-income English-speaking countries for men but not women; however, it was present for both genders in sub-Saharan Africa, in countries of the former Soviet Union, and in Latin America and the Caribbean (their figure 3).30 The researchers also found evidence of an inverted U-shape in age for whether respondents had experienced “a lot of worry yesterday” in English-speaking countries, Latin America, and the Caribbean.31

A recent study used data from a telephone survey conducted in 2008 by the Gallup organization to examine well-being in the United States.32 The authors found that enjoyment showed a U-shaped pattern in age, along with happiness, with the low point at age 50. Sadness and worry both had an inverted U-shape in age. Stress, though, rose from the youngest age group (18–21) to ages 22–25 and then fell steadily thereafter; anger also declined after the mid-20s.

There is evidence of a U-shape curve in relationship satisfaction. Specifically, it decreases during the first years of a relationship but increases subsequently.33 It also turns out that happiness with one’s marriage is U-shaped in age as well. In the U.S. General Social Survey from 1973 to 2016, respondents were asked how happy they were with their marriage: not too happy (= 1); pretty happy (= 2); and very happy (= 3). I examined how this varied by age and restricted the sample to those who were married; with a sample of 29,500 it turns out that happiness minimizes at age 47.34

It is also possible to look at the number of bad mental health days people report having in one month. I examined microdata files for the United States from the 2000 and 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). The BRFSS asks respondents how many bad mental health days they have experienced over the previous month. These data were reported on by Case and Deaton (2015), who found that men and women ages 45–54 for the periods 1997–99 and 2011–13 reported an additional day of bad mental health on the month. It turns out that the states with the highest number of bad mental health days in 2015 were Kentucky (47), Alabama (48), West Virginia (49), and Tennessee (50).35 Hawaii and South Dakota had the lowest number of bad mental health days.

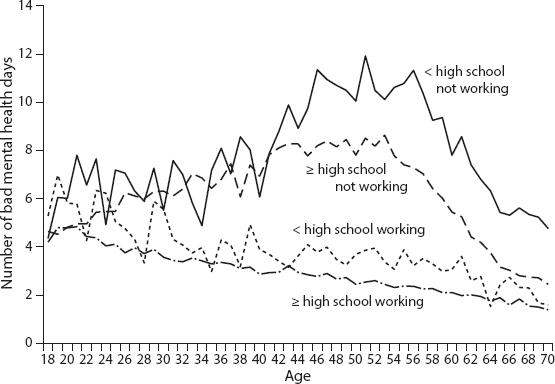

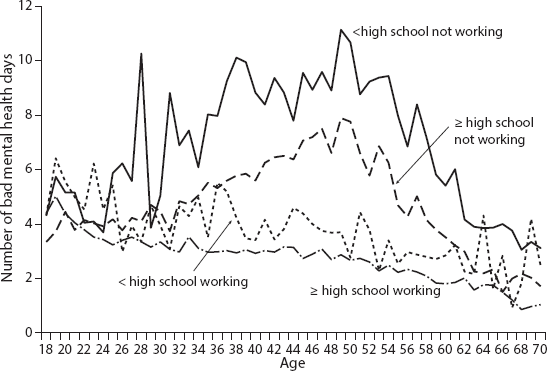

I plotted the number of bad mental health days by single year of age separated out by low and high levels of education and whether the respondent was working or not working. Here low education is defined as a high school graduate/GED or less and high education is at least some college. Figure 8.2 shows, for 2016, that the number of bad mental health days declines with age for those who work. There is a clear inverted U-shape for those who are not working, whether with a low or a high education. Both peak around age 50. The peak for the less educated is 12 bad mental health days, whereas it is nearly 9 for the more educated. Figure 8.3 is for 2000 and also shows the same pattern although the minimum is further to the left.

Not working is bad for mental health, especially for those with less than a high school education. There were markedly fewer people employed as a proportion of the population in 2016 than there were in 2000. In 2000 the employment rate was 64 percent. In 2016 it was just under 60 percent.

In another article I wrote with Andrew Oswald (2016), we found that antidepressant use took the form of an inverted U-shape in age across twenty-seven EU countries. We also found that, despite the advantages of modern living, one in thirteen Europeans had taken an antidepressant in the previous twelve months. The rates of antidepressant use are greatest in Portugal, Lithuania, France, and the UK. Rather robustly, the probability of using an antidepressant attains a maximum in the late 40s. This seems to suggest that mental distress is particularly acute in midlife. In addition, the probability of taking antidepressants is also greater among those who are female, unemployed, poorly educated, or divorced or separated.

Figure 8.2. U.S. number of bad mental health days by age. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/data_documentation/index.htm.

Figure 8.3. U.S. number of bad mental health days by age. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2000, https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/data_documentation/index.htm.

Cumulative Disadvantage and Deaths of Despair

Anne Case and Angus Deaton documented rising mortality rates for white non-Hispanic men and women ages 45–54 in the United States between 1999 and 2013 (Case and Deaton 2015). Death rates for this group rose both absolutely and relative to other racial and ethnic groups. The rising rate of “deaths of despair,” as they call them, is due to drug and alcohol poisoning and suicide, which disproportionately impact the middle-aged but especially white non-Hispanic middle-aged.

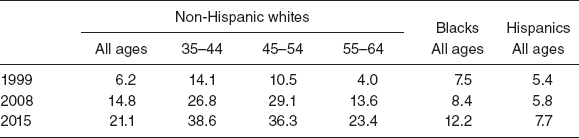

Table 8.2 reports death rates from drug poisoning by age in 1999, 2008, and 2015. It shows the white non-Hispanic rate more than tripled between 1999 and 2015. The rate for blacks and Hispanics rose by a lot less. The increase for white non-Hispanic women and men aged 45–54 was especially marked (8 to 32% for women and 13 to 41% for men). Among patients receiving opioid prescriptions for pain, higher opioid doses were associated with increased risk of opioid overdose death.36 Specifically, the risk of drug-related adverse events is higher among individuals prescribed opioids at doses equal to 50 milligrams per day or more of morphine. More is worse, less is better.

Table 8.2. Age-Adjusted Death Rates (%) Due to Drug Poisonings: United States, 1999–2015

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, “Drug Poisoning Mortality in the United States, 1999–2016,” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-visualization/drug-poisoning-mortality/#tables.

Over the fifteen-year period, midlife all-cause mortality fell by more than 200 per 100,000 for black non-Hispanics, and by more than 60 per 100,000 for Hispanics. By contrast, white non-Hispanic mortality rose by 34 per 100,000. Case and Deaton (2015) find that the change is largely accounted for by an increasing death rate from external causes, mostly increases in drug and alcohol poisonings and in suicide. In contrast to earlier years, drug overdoses were not concentrated among minorities. In 1999, poisoning mortality for ages 45–54 was 10.2 per 100,000 higher for black non-Hispanics than white non-Hispanics; by 2013, poisoning mortality was 8.4 per 100,000 higher for whites. Death from cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases fell for blacks and rose for whites.

After 2006, death rates from alcohol- and drug-induced causes for white non-Hispanics exceeded those for black non-Hispanics; in 2013, rates for white non-Hispanics exceeded those for black non-Hispanics by 19 per 100,000. Case and Deaton found that all education groups saw increases in mortality from suicide and poisonings, as well as an overall increase in external-cause mortality; those with less education saw the most marked increases. This increase in all-cause mortality for those ages 45–54 was not seen in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Sweden, or the UK.

In a follow-up paper Case and Deaton (2017b) noted that increases in all-cause mortality continued unabated to 2015, with additional increases in drug overdoses, suicides, and alcoholic-related liver mortality, particularly among those with a high school degree or less. The decline in mortality from heart disease, they reported, has slowed and, most recently, stopped, and this combined with the three other causes is responsible for the increase in all-cause mortality. Their main finding is that educational differences in mortality among whites are increasing, but mortality is rising for those without, and falling for those with, a college degree. This is true for white non-Hispanic men and women in all age groups from 25–29 through 60–64. Mortality rates among blacks and Hispanics continue to fall; in 1999, the mortality rate of white non-Hispanics aged 50–54 with only a high school degree was 30 percent lower than the mortality rate of blacks in the same age group; by 2015, it was 30 percent higher.

Alcohol-poisoning deaths are high for two distinct groups: (1) men ages 45–54, and (2) white non-Hispanics, although markedly lower than for drug poisonings.37 Using the most recent data we have available for the United States, we can track changes in death rates due to alcohol poisoning between 1999 and 2014.38 The number of deaths from chronic liver disease for those ages 45–54 rose from 17.4 to 19.9 per 100,000, with the biggest rise for those ages 55–64, from 23.7 to 31.9. Death rates from chronic liver disease in the United States were 18 per 100,000 for white non-Hispanic men versus 9.5 for black men and 4.1 for Asians. Rates were second highest in West Virginia (14.3), behind New Mexico (22.5).

Eurostat provides evidence on death rates from alcohol between 2011 and 2013 for the UK plus France, Germany, and Italy. These have not changed much over time and remain at low levels. Drug-poisoning deaths are a lot higher in the UK than the other three countries, confirming the findings of Case and Deaton that trends in mortality due to drugs, alcohol, and suicide were especially high in other English-speaking countries. They found that the UK, Ireland, Canada, and Australia stand alone among the comparison countries in having substantial positive trends in mortality from drugs, alcohol, and suicide over this period. However, their increases are dwarfed by the increase among U.S. whites.

Suicide is a leading cause of death in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has found that since 1999 there has been a steady climb in the rate of Caucasian suicides, from 11.5 in 1999 to 15.4 in 2014.39 Age-adjusted suicide rates for females rose from 4.0 in 1999 to 5.8 in 2014.40 For males, the rate rose from 17.8 to 20.7. A majority of Caucasian suicide victims were male, with a rate of 24 per 100,000 (compared to a rate of 7 for women). There was an especially large jump in the suicide rate of white non-Hispanic males aged 45–64 between 1999 and 2014, from 7.0 to 12.6. There also appears to be an inverted U-shape in age in suicide especially among females in the United States, although not so obviously for men.41

Between 1999 and 2015, suicide rates increased across all levels of urbanization, with the gap in rates between less urban and more urban areas widening over time, most conspicuously over the later part of this period. Geographic disparities in suicide rates, Kegler, Stone, and Holland (2017) suggest, might reflect suicide risk factors known to be prevalent in less urban areas, such as limited access to mental health care, social isolation, and the opioid overdose epidemic, because opioid misuse is associated with increased risk for suicide. The gap in rates began to widen more noticeably after 2007–8, which might reflect the influence of the economic recession, which disproportionately had less impact on urban areas.

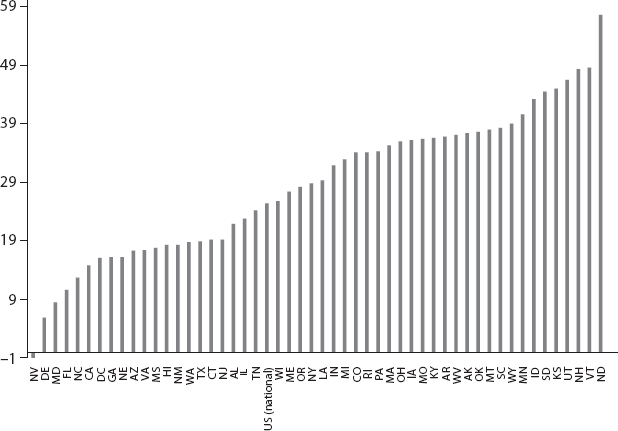

In June 2018 the CDC reported that nearly 45,000 lives were lost due to suicide in 2016, a few days after the suicides of fashion designer Kate Spade and chef and raconteur Anthony Bourdain. Suicides were up 25 percent nationally and by more than 30 percent in half of the states since 1999 and were only down in Nevada. More than half of the people who died by suicide did not have a known mental health condition, which may just show the inadequacy of mental health care provision. Figure 8.4 reveals the suicide rate changes by state; North Dakota had the highest change in the suicide rate, followed by Vermont and New Hampshire. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, an average of twenty veterans a day committed suicide in 2014.42 These data are scary.

Figure 8.4. Suicide rate changes by state, 1999–2016. Sources: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/; https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/infographic.html#graphic1.

Stuckler and Basu (2013) have argued that austerity kills. They estimate that 4,750 “excess” suicides, that is, deaths above what preexisting trends would predict, occurred from 2007 to 2010. Rates of such suicides were significantly greater in the states that experienced the greatest job losses. Deaths from suicide, they note, in the UK overtook deaths from car crashes in 2009.

Mary Daly, who has recently become the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Federal and who in 2018 had a vote on interest rates, and her coauthors (2011) present evidence to suggest that others’ happiness may be a risk factor for suicides. Using international and U.S. data, they note a paradox: the happiest places tend to have the highest suicide rates. Denmark and Sweden have a positive correlation between suicide rates and life satisfaction levels. What they call “dark contrasts” may in turn increase the risk of suicide. This is comparable to the finding that in Italy, suicide rates of the unemployed seem to be higher in low-unemployment regions.43

As one might expect, happy people themselves are less likely to commit suicide. At baseline, Koivumaa-Honkanen et al. (2003) found that in a sample of 29,000 adult Finns, unhappiness was associated with older age groups, being male, sickness, living alone, smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and belonging to an intermediate social class. The risk of suicide over the next twenty years increased with decreasing happiness.

Case and Deaton in their 2015 article examine the relationship between suicide, age, and well-being and find that suicide has little to do with own life satisfaction. However, they do find at the county level that suicide rates are higher where life evaluation is higher, confirming the findings of the 2011 Daly et al. paper. They note that suicides are most likely to occur on Mondays: 16 percent of suicides occur on that day of the week. The Boomtown Rats were right when they sang, “I don’t like Mondays.” Apparently mental health episodes are more likely to occur at holiday times as well.44 In addition, Case and Deaton (2015) find that the prevalence of pain, which is increasing in middle-aged Americans, is strongly predictive of suicides.

A recent study explored the relationship between mortality and a plausibly exogenous change in U.S. trade policy in October 2000: granting Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) to China that differentially exposed U.S. counties to increased international competition via their industry structure.45 The authors of the study found that counties more exposed to trade liberalization exhibit higher rates of suicide among whites and especially white men.

Case and Deaton argue that the rise in mortality of prime-age, less-educated whites in the United States is explained by cumulative disadvantage, which they suggest is “rooted in the steady deterioration in job opportunities for people with low education. Ultimately, we see our story as about the collapse of the white, high school educated, working class after its heyday in the early 1970s, and the pathologies that accompany that decline” (2017b, 438–39). Cherlin concurs, arguing that what he calls the fall in the working-class family occurred because less-educated people lack strong connections to mainstream institutions such as marriage, the labor market, and organized religion: “The hollowing out of the labor market—the loss of industrial jobs to offshoring and computerization—has removed the economic foundation of the kind of working-class lives their mothers and fathers led” (2014, 175).

Case and Deaton’s conclusions have been attacked by Auerbach and Gelman for aggregating the data too much by race.46 In addition, Harris47 criticized Case and Deaton for disaggregating the data too much by education levels and ignoring selection effects. Noah Smith effectively disposes of these criticisms, arguing that they are overblown and concluding that these critiques “don’t invalidate the result.” Smith argues that “most of the critics have overstated their case pretty severely. The Case-Deaton result is not bunk—it’s a real and striking finding.” He suggests that a lot of the eagerness to discredit Case and Deaton’s results stems from political reasons. He concludes, “The critiques of Case-Deaton are overdone. Maybe Case and Deaton should have focused less on disaggregating by education, and more on disaggregating by gender, age, and region. But those are quibbles. The main results are real and important.48 I agree.

Things Are Worse in Rural Areas

There is a big contrast between rural areas and the big cities. In an interesting column Paul Overberg identifies several factors distinguishing rural from urban areas, not least that few immigrants are moving to rural areas. Most seek work and neighbors in places that are familiar, which largely means urban areas.49 This, Overberg argues, has opened a cultural gulf between diverse, growing cities and mostly white, aging small towns. Rural areas have only 3.8 percent of their populations that are foreign born versus 22 percent in large metro areas.

Overberg notes that in the 1990s, a few rural areas began to record more deaths than births. Then the recession of 2007–9 lowered U.S. birth rates and slowed migration and immigration. Rural America now faces the “grim prospect” of natural decrease, meaning more deaths than births over time. More jobs, especially full-time jobs with benefits, require a bachelor’s or advanced degree. Without a larger share of college graduates, small towns have little hope of closing the income gap. Rural America seems to be anti-immigrant even though they have relatively few immigrants. Rural America voted for Trump.

There is new evidence from the CDC that the death rate in rural areas from the five leading causes of death—heart disease, cancer, unintentional injury, chronic lower respiratory disease, and stroke—is much higher than in urban areas.50 Moy and coauthors (2017) note that it is well known that residents in rural areas have higher rates of health risk factors for the leading causes of death, including factors such as cigarette smoking, obesity, physical inactivity during leisure time, and not wearing seatbelts. They also tend to have less access to health care and preventive services.

The authors examine “excess death,” which the CDC defines as deaths among persons less than 80 years old over the number that would be expected if the age-specific death rates of the three states with the lowest rates (i.e., benchmark states) occurred across all states. They find that approximately half of deaths among persons less than 80 years old from unintentional injury (57.5%) in nonmetropolitan areas were potentially excess deaths, compared with 39.2 percent in metropolitan areas. Over the period 1999–2014 deaths from unintentional injury rose in metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas, and in all years, they were approximately 50 percent higher in rural areas than urban areas.

Garcia et al. (2017) suggest that several factors explain the wide gap in rural-urban death rates from unintentional injuries. First, unintentional injury burden is higher in rural areas because of severe trauma associated with high-speed motor vehicle traffic-related deaths. Second, rates of opioid analgesic misuse and overdose death are highest among poor and rural populations. Third, behavioral factors (e.g., alcohol-impaired driving, seatbelt use, and opioid prescribing) contribute to higher injury rates in rural areas. Fourth, access to treatment for trauma and drug poisoning is often delayed when the injury occurs in rural areas. For life-threatening injury, higher survival is associated with rapid emergency treatment. Because of the geographic distance involved, emergency medical service (EMS) providers who operate ambulances take longer to reach injured or poisoned patients in rural areas.

Moreover, the authors note, ambulatory transport to the optimal treatment facility also can take longer because of increased distance to the treatment facility. Most life-threatening trauma is best treated in advanced trauma centers, which are usually located in urban areas; care at these centers has been associated with 25 percent lower mortality.51 Folks in rural areas, whose health care has been left behind, voted for Trump.

In October 2017 the CDC noted that in 2015, approximately six times as many drug-overdose deaths occurred in metropolitan areas than occurred in nonmetropolitan areas (metropolitan: 45,059; nonmetropolitan: 7,345). Drug-overdose death rates (per 100,000 people) for metropolitan areas were higher than in nonmetropolitan areas in 1999 (6.4 versus 4.0); however, the rates converged in 2004, and by 2015, the nonmetropolitan rate (17.0) was slightly higher than the metropolitan rate (16.2).52

In November 2018 the CDC released new data showing that life expectancy at birth in the United States in 2017 was 78.6 years, down from 78.7 in 2016 (Murphy et al. 2018). The CDC also reported (Hedegaard, Miniño, and Warner 2018) that there were 70,237 drug-overdose deaths in the United States in 2017. The age-adjusted rate of drug overdoses was 9.6 percent higher in 2017 compared with 2016. There was a sharp increase in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol, from 2016 to 2017. The age-adjusted rate of drug-overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone increased by 45 percent. While the average rate of drug-overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids increased by 8 percent per year from 1999 to 2013, the average rate increased by 71 percent per year from 2013 to 2017. West Virginia (57.8 deaths per 100,000 people), Ohio (46.3), and Pennsylvania (44.3) had the highest age-adjusted drug-overdose rates.

The suicide rate among the U.S. working-age population increased 34 percent during 2000–2016 (Hedegaard, Curtin, and Warner 2018). In 2012 and 2015, suicide rates were highest among males in the “construction and extraction” occupational group (43.6 and 53.2 per 100,000 civilian noninstitutionalized working persons, respectively), who were especially hard hit by the housing crash in the Great Recession.53 The age-adjusted suicide rate for urban counties in 2017 was 16 percent higher than the rate in 1999, whereas in rural counties in 2017 it was 53 percent higher. By 2017 the suicide rate in rural counties (20 per 100,000) was nearly double that of urban counties (11.1).

Globalization, automation, and falling real wages do seem to be the cause of the long-term patterns of mortality and morbidity I have documented. The Great Recession didn’t cause them but simply exposed underlying trouble. Alarmingly, life expectancy in the United States at 78.6 years in 2017 was down 0.1 percent from 2016, which was the second year in a row of a 0.1 percent decline.54 After decades of steady improvements in the UK, in the most recent data for 2015–17 life expectancy at birth saw no improvement from the previous national life tables.

A lack of well-paying jobs was always going to have consequences. Joblessness worsens mental health. Rural areas in the United States have been hit especially hard. Rural areas voted for Trump. Society cannot function if it is every man for himself. By definition society cannot survive that. Those in authority must retain the public’s trust.