If at any time in the history of India the mind of the nation as a whole has been diseased, it was in the Tantric age, or the period immediately preceding the Muhammadan conquest of India. . . . The story related in the pages of . . . Tantric works is so repugnant that excepting a few, all respectable scholars have condemned them wholesale. . . . No one should forget that the Hindu population of India as a whole is even today in the grip of this very Tantra in its daily life; . . . and is suffering from the same disease which originated 1300 years ago and consumed its vitality. . . .

Someone should take up the study comprising the diagnosis, etiology, pathology and prognosis of the disease so that more capable men may take up its treatment and eradication.

Benyotosh Bhattacharyya,

An Introduction to Buddhist Esoterism (1932)

The category “Tantra” is a basic and familiar one today in the vocabulary of most scholars of religions and generally considered one of the most important and controversial forms of Asian religion. In academic discourse, Tantra usually refers to a specific brand of religious practice common to the Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions since at least the seventh century; above all, it is identified as a particularly radical and dangerous practice that involves activities normally prohibited in mainstream society, such as sexual intercourse with lower-class partners and consumption of meat and wine. Not surprisingly, given the rather racy nature of the subject, interest in Tantra has skyrocketed in the past two decades in both the popular and scholarly imaginations. On the academic level, Tantra has become one of the hottest topics in the field of South Asian studies, generating a large body of provocative (and often controversial) new scholarship.1 Still more strikingly, Tantra has also become an object of fascination in the popular imagination, where usually it is defined as “sacred sex” and often is confused with Eastern sexual manuals such as the Kāma Sūtra and Western occult traditions such as Aleister Crowley’s “sex magick.” As we can see on the shelves of any bookstore, Tantra pervades Western pop culture, appearing in an endless array of books, videos, and slick web sites. Indeed, the phrase “American Tantra” is now even a registered trademark, representing a whole line of books, videos, and “ceremonial sensual” merchandise.2

And yet, as André Padoux points out, the category “Tantrism”—as a singular, coherent entity—is itself a relatively recent invention, in large part the product of nineteenth-century scholarship, with a tangled and labyrinthine history.3 When it was first discovered by Orientalist scholars and missionaries in the eighteenth century, Tantra was quickly singled out as the most horrifying and degenerate aspect of the Indian mind. Identified as the extreme example of all the polytheism and licentiousness believed to have corrupted Hinduism, Tantra was something “too abominable to enter the ears of man and impossible to reveal to a Christian public,” or simply “an array of magic rites drawn from the most ignorant and stupid classes.”4 Yet in our own generation, Tantra has been praised as “a cult of ecstasy, focused on a vision of cosmic sexuality,” and as a much needed celebration of the body, sexuality, and material existence.5

This ambivalence has grown even more intense in our own day. On the one hand, the scholarly literature often laments that Tantra has been woefully neglected in the study of Asian religions as “the unwanted stepchild of Hindu studies.”6 On the other, if we peruse the shelves of most popular bookstores or scan the rapidly proliferating web sites on the Internet, it would seem that Tantra is anything but neglected in modern discourse. As we see in endless publications, bearing titles like Tantric Secrets of Sex and Spirit or Ecstatica: Hypno Trance Love Dance, Tantra has become among the most marketable aspects of the “exotic Orient.” Borrowing some insights from Michel Foucault and his work on sexuality in the Victorian era, I will argue that Tantra has by no means been repressed or marginalized; on the contrary, like sex itself, Tantra has become the subject of an endless proliferation of discourse and exploited as “the secret.”7 Indeed, one might say even that Tantra represents the ideal religion for contemporary Western society. A religion that seems to combine spirituality with sensuality, and mystical experience with wine, women, and wealth, Tantra could be called the ideal path for spiritual consumers in the strange world of “late capitalism.”8

But despite the contradictory and wildly diverse constructions of Tantra, both popular and scholarly, there is still one key element that all of these imaginings share, namely, the very extremity of Tantra, its radical Otherness, the fact that it is considered to be the most radical aspect of Indian spirituality, the one most diametrically opposed to the modern West. As Ron Inden has argued, the India of Orientalist scholarship was constructed as the quintessential Other in comparison to the West. Conceived as an essentially passionate, irrational, effeminate world, a land of “disorderly imagination,” India was set in opposition to the progressive, rational, masculine, and scientific world of modern Europe.9 And Tantra was quickly singled out as India’s darkest, most irrational element—as the Extreme Orient, the most exotic aspect of the exotic Orient itself.10

This book traces the complex genealogy of the category of Tantra in the history of religions, as it has been formed through the interplay of Eastern and Western, and popular and scholarly, imaginations. What I hope to achieve is by no means just another anti-Orientalist critique or postcolonial deconstruction of an established category—an exercise that has become all too easy in recent years. Rather, I suggest that Tantra is a far messier product of the mirroring and misrepresentation at work between both East and West. It is a dialectical category—similar to what Walter Benjamin has called a dialectical image—born out of the mirroring and mimesis that goes on between Western and Indian minds.11 Neither simply the result of an indigenous evolution nor a mere Orientalist fabrication, Tantra is a shifting amalgam of fantasies, fears, and wish fulfillments, at once native and Other, which strikes to the heart of our constructions of the exotic Orient and of the contemporary West.

I hope that this book will offer not only a valuable contribution to our knowledge of South Asian religions, but also, more important, a keen insight into the very nature of cross-cultural dialogue, the mutual re- and misrepresentations of the Other that occur in every cross-cultural encounter. In the chapters that follow I explore a series of reciprocal exchanges between East and West, played out in several key historical encounters—from the severe criticisms of Tantra by early European scholars and the reactions of Hindu reformers, to the paranoid imaginings of British authorities and the uses of Tantra by the revolutionary Indian nationalists, to the wildly exoticized representations of Tantra in English and Indian fiction, to the role of Tantra in contemporary New Age and New Religious movements. Finally, I explore some possible ways to redefine and reimagine Tantra in a more useful form in contemporary discourse.

The moment one hears the word “Tantrism,” various wild and lurid associations spring forth in the Western mind which add up to a pastiche of psychospiritual science fiction and sexual acrobatics that would put to shame the most imaginative of our contemporary pornographers.

Jacob Needleman, The New Religions (1970)

But just what is Tantra? Few terms, it would seem, are at once so pervasive, so widely used, and yet so ill-defined in contemporary discourse, both popular and academic. As Herbert Guenther put it, Tantra is perhaps “one of the haziest misconceptions the Western mind has evolved.”12 It is a term that permeates literature, movies, and the Internet, as we now find alternative-rock groups described as “Tantric” and pop stars like Sting claiming to have achieved seven-hour orgasms by means of Tantric sexual techniques.13 Yet it is a term that most people would be hard pressed to define.

As we will see in more detail, the Sanskrit word tantra has appeared since Vedic times with an enormous diversity of meanings; it has been used to denote everything from a warp or a loom (e.g., AV 10.7.42), to the “chief potion or essence of a thing,” to simply “any rule, theory or scientific work” (Mahābhārata 13.48.6).14 Probably derived from the root tan, “to weave or stretch,” tantra is most often used to refer to a particular kind of text, which is “woven” of the extended threads of many words. Yet, as Padoux points out, such texts may or may not contain materials that we today think of as “Tantric.”15

For most American readers today, Tantra is usually defined as “sacred sexuality,” “spiritual sex,” or “sex magic”—that is, the unique synthesis of religion and sexuality, which is also often identified with diverse spiritual traditions from around the world, such as European sexual magic, Wicca, Kabbalah, and even certain Native American practices. “Tantra is the only spiritual path that says that sex is sacred and not a sin,” as one recent author, Swami Nostradamus Virato, defines it. “The art of Tantra . . . could be called spiritual hedonism, which says ‘eat drink and be merry but with full awareness.’ . . . Tantra says yes! to sex; yes! to love.”16 According to an even more explicit New Age appropriation—the “American Tantra” espoused by California eros-guru Paul Ramana Das—the sexual magic of Tantra has now become a hyperorgasmic event of truly cosmic proportions:

American Tantra (tm) is a fresh eclectic weaving of sacred sexual philosophies drawn from around the world, both ancient and modern. . . . Making love is a galactic event! . . . We intend to co-create neo-tribal post-dysfunctional sex and spirit positive . . . generations of gods and goddesses in the flesh. On the Starship Intercourse we greet and part with: orgasm long and prosper!17

Thus, according to many popular accounts, such as that of the great “neo-Tantric” master, the notorious Osho-Rajneesh, Tantra is not even a definable religion or philosophy; it is more of a nonreligion, an antiphilosophy, which insists on direct experience, not rational thought or dogmatic belief: “The Tantric attitude . . . is not an attitude. It has no concepts, it is not a philosophy. It is not even a religion, it has no theology. It doesn’t believe in words, theories, doctrines. . . . It wants to look at life as it is. . . . It is a non-attitude.”18

Unlike many recent scholars, however, I do not think that the popular American and New Age versions of Tantra can be dismissed as the mere products of “for-profit purveyors of Tantric sex,” who “peddle their shoddy wares.”19 Rather, I see these contemporary neo-tāntrikas (however absurd they might appear to those in the academy) as important representations of the ongoing transformations of Tantra in culture and in history.

Not surprisingly, given the vast semantic range of the term and the diversity of texts and traditions using it, modern scholars struggled for generations to come up with some kind of usable definition for Tantrism. Not only is the very notion of Tantrism, as a unified, singular, abstract entity, itself largely the product of modern scholarship, but it has been subjected to an enormous variety of conflicting and contradictory interpretations. As Benyotosh Bhattacharyya commented in 1932, “Many scholars have tried to define the Tantras; but every one of their descriptions is insufficient. . . . The definitions of Tantra given by students of Sanskrit literature are not unlike the descriptions of an elephant given by blind men.”20

At one end of the scholarly spectrum, as we see in the earliest Orientalist and missionary accounts, Tantrism was defined as the most debased form of Hindu idolatry and the most shocking confusion of sexuality with religion. The “so-called Tantric religion,” as Talboys Wheeler defined it in 1874, is essentially a cult wherein “nudity is worshipped in Bacchanalian orgies which cannot be described.”21 At the complete opposite end of the hermeneutic spectrum, however, there is Sir John Woodroffe’s highly apologetic, sanitized definition, which largely excises or rationalizes Tantra’s alleged sexual content: indeed, in Woodroffe’s redefinition, far from being a decline into depraved licentiousness, Tantra becomes a noble and orthodox tradition in continuity with the most ancient teachings of the Vedas and Vedānta: indeed, “Tāntrikism is nothing but the Vedic religion struggling . . . to reassert itself.”22

In more recent years, there appears to have been a remarkable shift back to the opposite end of the spectrum, toward an emphasis on Tantra’s sexual and scandalous aspects—though this time in a far more positive, even celebratory sense. As we see in the more romantic definitions of Mircea Eliade and other European historians of religions, Tantra represents a much needed affirmation of sexuality and bodily existence, much older than the Vedic Aryan tradition with its patriarchal ideology; it is a “great underground current of autochthonous and popular spirituality,” centering around the worship of the Mother Goddess, which later burst forth into mainstream Hindu and Buddhist traditions.23 For other, still more enthusiastic authors like Philip Rawson, Tantra is nothing less than “a cult of ecstasy” that “offers a uniquely successful antidote to the anxieties of our time.”24 As we will see, it is in large part through the dialectical play between these extremes—from Victorian horror at Tantric licentiousness, to Woodroffe’s sanitization and defense of Tantric philosophy, to the neoromantic celebration of Tantric sexual liberation—that the notion of Tantrism has been formed in the modern imagination.

In the face of this intense confusion and contradiction, many scholars have abandoned the very idea of asserting a singular, monothetic definition for Tantra.25 As Douglas Brooks argues, Tantra is not something that can be defined as a singular, unified category; rather, it can only be described by what Jonathan Z. Smith calls a “polythetic classification,” in which a large number of characteristics are possessed by a large number of class members. Various scholars have offered different enumerations of such characteristics, ranging from six (Jeffrey Kripal) to eighteen (Teun Goudriaan).26 Brooks, for example, suggests the following ten properties of Tantric phenomena: (1) they are extra-Vedic; that is, not part of the conventional canon of Hindu scriptures; (2) they involve special forms of physical discipline, such as kuṇḍalinī yoga; (3) they are at once theistic and nondualistic; (4) they contain elaborate speculations on the nature of sound and the use of mantras; (5) they involve the use of symbolic diagrams, such as yantras or maṇḍalas; (6) they place special stress on the importance of the guru; (7) they employ the bipolar symbolism of the god and goddess; (8) they are secret; (9) they prescribe the use of conventionally prohibited substances (e.g., wine, meat, sexual intercourse); (10) they require special forms of initiation in which caste and gender are not the primary qualifications.27 Unfortunately, however, Brooks gives no indication as to just how many or which of these characteristics a given phenomenon must have to be usefully identified as Tantric; nor does he account for the large number of traditions that share most or all of these characteristics and yet would deny vehemently that they have anything to do with the “scandal and smut” of Tantrism.28

In sum, as Donald Lopez puts it, tantra has long been and still remains one of the most elusive terms in the study of Asian religions—a kind of “floating signifier . . . gathering to itself a range of contradictory qualities, a zero symbolic value, marking the necessity of a supplementary content over and above that which the signified contains.”29 Yet the reasons for this difficulty in defining Tantra are not far to seek. As I will argue, Tantra is a highly variable and shifting category, whose meaning may differ depending on the particular historical moment, cultural milieu, and political context. We might say that Tantra serves as a kind of Rorschach test or psychological mirror of the changing moral and sexual attitudes of the past two hundred years. As N. N. Bhattacharyya comments:

Most of the modern writers on this subject insist solely on its sexual elements, minimal though they are compared to the vastness of the subject, and purport to popularize certain modern ideas pertaining to sex problems in the name of Tantra. Thus the historical study of Tantrism has been handicapped, complicated and conditioned by the preoccupation of those working in the field.30

For this very reason, however, the various definitions of Tantra also offer us a fascinating window onto the history of the history of religions, revealing the particular historical moments and political contexts of those who have defined it.

Tantrism . . . is India’s most radical contribution to spirituality. The underlying idea of Tantrism is that even the most mundane occurrence can serve as a means of transcendence. . . . Sex is no longer feared as a spiritual trap but is employed as a gateway to heaven.

Georg Feuerstein, Holy Madness (1990)

In the United States, sex is everywhere except in sex.

Roland Barthes, Empire of Signs (1982)

One of the most pervasive themes in contemporary literature on Tantra—in both its popular and scholarly forms—is the notion that this tradition has been ignored, marginalized, and repressed consistently by Western scholarship. As Brooks argues, this “unwanted stepchild of Hindu Studies” has been a persistent source of embarrassment to scholarship. Brooks presents his own work as an act of retrieval and restoration that will completely revise our prejudiced and distorted understanding of Hinduism: “The Tantric traditions . . . are routinely treated as trivial or tangential to the mainstreams. . . . Just as our previously deficient understanding of Christianity has been corrected by considering mysticism . . . so our understanding of Hinduism will be revised when Tantrism . . . [is] given appropriate scholarly attention.”31

While I have great respect for Brooks’s work on South Indian Tantra, I must point out that this claim is, so far as I can tell, quite inaccurate. It is true that the body of texts known as tantras have long been misunderstood by Western scholars; yet even in the nineteenth century, Western scholars and popular writers appear not to have trivialized or marginalized the tantras, but in fact to have been fascinated by, often preoccupied and obsessed with, the seedy, dangerous world of the Tantras. And surely, since the pioneering work of John Woodroffe, and continuing with historians of religions like Mircea Eliade, Heinrich Zimmer, Agehananda Bharati, and many others, Tantra has become one of the most popular and pervasive topics in contemporary discourse about Indian religions. In short, far from being denied and ignored in modern literature, Tantra has arguably become one of the most widely discussed, fashionable, and marketable forms of South Asian religion. As Guenther remarked as early as 1952, “There is hardly any other kind of literature that has met with so much abuse . . . or has so much fascinated those who . . . thought the Tantras to be a most powerful and hence strictly guarded means for the gratification of biological urges.”32

This fascination with the Tantras—and this complex mixture of prudish repugnance and tantalizing allure—has only grown all the more intense in recent years. According to one of the most common tropes in recent New Age and popular religious literature, our sexuality has been repressed and denied by the stifling institutions of Christianity; therefore, to realize our true potential, we must turn to the ancient arts of the Orient—above all to the sexual magic of Tantra—to liberate the immense wellspring of power within us. So reads an article on the tantra.com web site:

Sex as an art form has yet to mature in the West. Social repression and internalized guilt have prevented Westerners from a frank and joyous exploration of sexuality. . . . The Orient did not consider sex apart from . . . spirituality. . . . All variations of sexual postures were . . . venerated. Sex was given a place of honor. . . . The parameters of sexual behavior in the East extend way beyond the West’s narrow spectrum of normalcy.33

Surely few other forms of Hinduism or Buddhism have generated as much literature in the past twenty years, both scholarly and popular, as the Tantras. One need only peruse the shelves of any bookstore or surf the Internet to see that Tantra has come to capture the Western popular imagination no less than it has the academic. Now books such as Ecstasy through Tantra and Tantra: The Art of Conscious Loving are commonly available; as are any number of videos on “Tantric massage,” workshops such as “Extended Orgasms: A Sexual Training Class,” and web sites where we encounter the “Church of Tantra,” the “alchemy of ecstasy,” and so on.34 Indeed, we now also can order a wide range of sexual-spiritual commodities from the online “Tantra gift shop,” including herbs, aphrodisiacs, and other stimulating elixirs. In short, as Rachel McDermott aptly observes in her study of the recent explosion of interest in the Tantric goddess Kālī: “Interest in Tantra, while strong in the last decade, has skyrocketed in recent years, with magazines championing it, Web sites whose sole purpose is to explicate and illustrate it, and newsgroups whose conversations center around its use.”35

A similar narrative of “repression” and the present need for “liberation” centers around the role of women in the Tantras. From its origins, discourse on Tantra has focused particularly on the role of women in Tantric practice, and above all, their alleged role in sexual rituals. Yet many recent authors, such as Miranda Shaw, have fiercely argued that the role of women in Tantra has been consistently ignored, repressed, or marginalized by the (mostly male) scholars in the academy. According to Shaw, this is nothing other than a lingering residual effect of European colonialism and prudish Victorian attitudes: “The scholarly characterizations of the Tantric Buddhist yoginis as ‘lewd,’ ‘sluts,’ ‘depraved and debauched’ betray a vestige of Victorian indignation not only at non-marital sexual activity of women but also at the religious exaltation . . . of women.”36

At this point, I must wonder whether Shaw has been reading the same scholarship as I have. The available literature seems to me to demonstrate that the role of women by no means has been ignored or excluded but, on the contrary, often has been celebrated and exaggerated. While it is true that some authors have pointed out the exploitative use of women in Tantric ritual, the majority of modern scholars appear to have celebrated the status of women in Tantra as a much needed affirmation of femininity, motherhood, and the forces of nature. Consider, for example, the works of some of the most influential scholars like Mircea Eliade and Heinrich Zimmer: “Tantrism,” Eliade suggests, represents nothing less than “a religious rediscovery of the mystery of woman, for . . . every woman becomes the incarnation of the Śakti. . . . Woman incarnates both the mystery of creation and the mystery of Being, of everything that is, that becomes and dies and is reborn. . . . We must never lose sight of this primacy. . . of the Divine Woman . . . in Tantrism.”37 And of course, even more audacious assertions of the freedom and power of women in Tantra can be found in the seemingly endless array of New Age and popular religious literature in the contemporary West. In one recent and very enthusiastic work, Tantra: The Cult of the Feminine, the Woman of the Tantras is now praised as “the Erotic Champion,” holding a role far greater than that offered by any contemporary feminist movement.38

In sum, it would seem that neither Tantrism nor the women of Tantra have been marginalized or repressed in Western discourse: it is perhaps more accurate to say that Tantra has been exaggerated and, ultimately, commercialized—celebrated as the sexiest, most tantalizing offering of the exotic Orient. Despite the claims to liberate and redeem Tantra, much of the recent literature on the subject in fact only continues the worst tendencies of Western “Orientalism” and exoticism identified by Said and other postcolonial critics: the long-held image of India as the quintessential, irrational “Other” of the West.39

In this sense, Tantra would appear to play much the same role in the modern imagination as did “sexuality” during the Victorian era, as Michel Foucault has described it. Far from being simply prudish and repressive—as the predominant modern rhetoric would have it—the Victorian era was in fact pervaded by a deeper interest in and endless discourse about sexuality: “What is peculiar to modern societies . . . is not that they consigned sex to a shadow existence, but that they dedicated themselves to speaking of it ad infinitum, while exploiting it as the secret.”40 Conversely, our own generation—the generation of we “other Victorians”—is seemingly obsessed with the rhetoric of “unveiling” and “liberation,” of coming out of the closet and freeing itself of the prudish bonds of the Victorian era.

If sex is repressed, that is, condemned to prohibition . . . then the mere fact that one is speaking about it has the appearance of a deliberate transgression . . . we are conscious of defying established power . . . we know we are being subversive.

What stimulates our eagerness to speak of sex in terms of repression is doubtless this opportunity to speak out against the powers that be, to utter truths and promise bliss, to link together enlightenment, liberation and manifold pleasures.41

So too, I would argue, much of the contemporary rhetoric about the repression of Tantra reflects an obsession with the scandalous, seedy, sexy side of Tantra, and a similar claim to “liberate” it from the prudish Victorian biases of our scholarly forefathers.

“Oh it’s something post-colonial” . . . the latest catchall term to dazzle the academic mind.

Russel Jacoby, “Marginal Return” (1995)

From the outset of a study like this, however, I feel I need to address a few of the anticipated objections of my readers. No doubt, some will groan in tired dismay at the very suggestion of this project—a project that might appear, at first glance, to be just one more of the many Saidian critiques of Orientalism or another clever deconstruction of a familiar category. Let me make it clear, first of all, that my aim is by no means to prove that Tantra “never existed” or that it is purely a colonialist fantasy or a “Western category imposed upon Asian traditions.”42 Rather, I aim to reveal the complexity, plurality, and fluidity of the many varied traditions that we now call Tantra. The abstract concept of Tantrism, like “Hinduism,” is a relatively recent creation. Like religion itself, as Jonathan Z. Smith reminds us, it is the product of human imagination and our own “imaginative acts of comparison and generalization.”43 But it is not solely the product either of the Western mind or the scholarly imagination; rather, it is a complex hybrid creation of Eastern and Western and scholarly and popular imaginings. Moreover, this does not mean that we cannot still speak of Tantric texts, Tantric people, and Tantric practices. In short, rather than constructing abstract monolithic isms, it is perhaps more fruitful to look at specific forms of discourse, ritual acts, and historical actors, located in particular social, political, and economic contexts, which we, as scholars “imagining religion,” find it useful to label as Tantra.

Thus, what I hope to do here is something a bit more subtle and nuanced than a just another postcolonial white-male-bashing. In fact, I am in many ways skeptical of the recent proliferation of postcolonial discourse in the academy. As critics like Aijaz Ahmad have pointed out, there are a number of troubling problems inherent in the discourse of post-colonialism. First, it tends to oversimplify the colonial situation, portraying it as a simple Manichean binarism of colonizer and colonized, imperial oppressor and native victim.44 By overemphasizing the radical impact of Western power on the rest of the world, much postcolonial discourse, dividing global history into pre- and postimperial epochs, risks lapsing into a more subtle form of imperialism, viewing all human history from the standpoint of European expansion and the progress of modern capitalism.45

As Benita Parry and others argue, much of the anti-Orientalist discourse tends to place more or less all of the agency, knowledge, and power on the side of the colonizer. In so doing, it tends to reduce the colonized to a mere passive materia to be reformed in the imperial gaze, a helpless victim lacking the possibility to resist, challenge, and subvert Western representations.46 What we need, in short, is a more complex and interactive model of the encounter between East and West. This does not, however, have to be a simple romantic celebration of the colonized Other in its noble struggle to resist colonial domination—a cause that has become increasingly popular in recent years. Rather, we must examine both the ability of indigenous cultures to resist or contest and their tendency to mimic, cooperate, or collude with Western representations of the exotic Orient. Instead of a simple process of imperial domination and native resistance, we seem to find “a dense web of relations between coercion, complicity, refusal, mimicry, compromise, affiliation and revolt.”47

Finally and perhaps most problematically, much of the recent post-colonial literature tends to ignore, elide, or gloss over the more subtle forms of neocolonialism and cultural imperialism still very much at work in the West’s dealings with formerly colonized (and yet to be colonized) peoples in the Third World. As Ahmad has powerfully argued, much of the postcolonial literature is in fact complicit with a new form of economic imperialism, as consumer capitalism now spreads to virtually every corner of the globe. Just as capitalist industries have appropriated the material resources of Third World peoples and mass-marketed them to a Western audience, so too postcolonial theorists have capitalized upon the exotic cultural goods of formerly colonized peoples, packaged them in sexy, attractive wrappings, and marketed them to a host of intellectual consumers in the Western academy.48

We need to move beyond a predictable, postcolonial, anti-Orientalist reading of Tantra, to examine the more interesting ways in which this category has functioned in precolonial, neocolonial—and also quite non-colonial—contexts alike.

Genealogy does not pretend to go back in time to restore an unbroken continuity that operates beyond the dispersion of forgotten things; its duty is not to demonstrate that the past . . . continues secretly to dominate the present. . . . Genealogy does not resemble the evolution of a species. . . . On the contrary, to follow the complex course of descent is to maintain events in their dispersion; it is to identify the accidents, the minute deviations—or the complete reversals—the errors . . . and the faulty calculations that gave birth to those things that continue to exist and have value for us.

Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History” (1984)

My approach to the problem of Tantra will be that of an historian of religions, in the full sense—that is, an historian who critically interrogates those phenomena claiming to be eternal or transcendent, in the light of their most concrete social and political contexts. Here, I understand the task of the historian of religions to go beyond a simple Eliadean quest for universal symbolic patterns or a search for the sui generis essence of religion as the product of homo religiosus; rather, we must also examine myths and symbols as the works of living, historically situated human beings, as products of homo faber, inextricably enmeshed in social, political, and material struggles.49 The history of religions, as Bruce Lincoln points out, therefore bears a deep tension at its very heart: for the historian of religions must examine the most material, human, and temporal aspects of those phenomena that claim to be suprahuman and ahistorical: “To practice history of religions . . . is to insist on the temporal, contextual, situated, interested, human and material dimensions of those discourses . . . that represent themselves as eternal, transcendent, spiritual and divine.”50

Going still further, however, I will also approach the problem of Tantra as an historian of the history of religions; that is, I will trace the genealogies of (this particular category of) religion by critically examining the ways in which we scholars have constructed and manipulated our own objects of inquiry, grounding our own imaginings of Tantra firmly in their unique social, historical, and political contexts.51 The genealogy of Tantra will therefore turn out to be something of a political history of the history of the history of religions, tracing the ways in which both Western and Indian authors have defined and redefined “Tantra” in relation to specific scholarly, ideological, and political interests.

The imagining of Tantra, we will find, has been anything but a simple process or the result of a straightforward, linear narrative. Rather, it is the result of a tangled genealogy, as conflicted and contested as the history of encounters between India and the West over the past several hundred years. To trace this genealogy is not a matter of reconstructing a tidy historical progression leading up to our own era, but rather of piecing together the fragmented, contradictory, and often quite erroneous tangle of discourses that have given birth to this strange hybrid construction. It is a matter of tracing, as Foucault puts it, “the accidents . . . the complete reversals—the errors, the false appraisals and the faulty calculations that gave birth to those things that continue to have value for us.”

Where thought comes to a standstill in a constellation saturated with tension, there appears the dialectical image, it is the caesura in the movement of thought. It is to be sought at the point where the tension between the dialectical oppositions is the greatest.

Walter Benjamin,

“Erkenntnistheoretisches, Theorie des Fortschritts” (ca. 1937)

If my general method is that of an historian of religions, the various hermeneutic tools I employ to make sense of this category are drawn from a wide range of disciplines, employing a number of comparative insights borrowed from many cultures and fields. Above all, I hope to use some of the insights of Michael Taussig, specifically the key notions of the “dialectical image” and the cross-cultural play of “mimesis,” which he in turn adapts from Walter Benjamin. As a dialectical category, Tantra is a complex, shifting fusion of both Western and Indian discourse, a composite construction of Orientalist projections, indigenous counterprojections, and the play of misrepresentation between them.

On one side, the image of Tantra clearly has been the result of a certain displacement of many deep-seated fears, anxieties, and desires within the Western imagination, projected onto the screen of the exoticized Other of India. As Gustavo Benevides comments in his study of Giuseppe Tucci, one of Europe’s greatest scholars of Buddhist Tantra, “The vision of the Orient nurtured by these intellectuals was in most cases a screen upon which they could project their own understanding of the Occident: either the triumphant discovery that the West was superior to the East, or the melancholy realization that the East possessed a magic no longer present in West.”52 Richard King has recently explored a similar dynamic in his study of Western scholarship on mysticism and the construction of India as the “mystic East” in the Orientalist imagination. Rather strangely, however, King makes absolutely no reference either to the role of sexuality in mysticism or to Tantra—a category that was a key, I will argue, in the Western imagining of India, and a crucial part of the modern imagining of mysticism, particularly in its most dangerous and aberrant forms.53

In this sense, the image of Tantra is closely related to the broader construction of “the primitive” or “savage” in modern anthropological and popular discourse. As Torgovnick puts it, “the primitive is the screen upon which we project our deepest fears and desires”; indeed, “the West seems to need the primitive as a precondition and supplement to its sense of self: it always creates heightened versions of the primitive as nightmare or pleasant dream.”54

Yet surely it would be a mistake to assume that this has been an entirely one-way process of projection, an imaginal creation of the Western mind. The category of Tantra is every bit as much a product of the Indian imagination’s counterimagining, mimicry, and mirroring. As Wilhelm Halbfass has argued, Indian intellectuals have consistently redefined themselves in the face of the encounter with the West—often by adapting Western categories and constructions: “Indians reinterpreted key concepts of their traditional self-understanding, adjusting them to Western modes of understanding. By appealing to the West, by using its conceptual tools they tried to defend the identity of their tradition.”55 Since at least the mid-nineteenth century, the category of Tantra has been reappropriated and reinterpreted by Indian authors as a basic part of the ways in which they understand their own traditions. The idea of Tantra—with all its immoral and scandalous connotations—has become a basic part of the way in which many Indians now interpret their own history: “We cannot look at Tantrism as mere perversion without at the same time looking at ourselves as a nation of perverts. . . . It is necessary to know how our ancestors had such absurd beliefs in order to understand how we have become what we are today.”56 The imagining of Tantrism is thus very similar to that of “Lamaism” in the case of Tibetan Buddhism. As Donald Lopez observes in his incisive study of the modern imagining of Shangri-La, “the abstract noun, coined in the West, has become naturalized as if it were an empirical object, the manipulation of which has effects beyond the realm of rhetoric.”57

Thus the construction of Tantra is neither a simple indigenous fact nor the mere product of Western projection and fantasy: it is the complex result of a long history of mutual misrepresentation and mirroring at work between both Western and Eastern imaginations—a kind of “curry effect” (to play on Agehananda Bharati’s metaphor of the “pizza effect”) or a game of cross-cultural Ping-Pong.58 This is an especially acute example of what Friedrich Max Müller long ago called “that world wide circle through which, like an electric current, Oriental thought could run to the West and Western thought returns to the East.”59

It is in precisely this sense, I would suggest, that Tantra can be understood as a unique example of a dialectical image, to borrow Walter Benjamin’s apt phrase. As a “constellation saturated with tension,” the dialectical image brings together past and present, ancient myth and contemporary meaning in a single, highly charged, symbolic form.60 In contrast to the romantic notion of the “symbol”—imagined as a unified, coherent cipher of some hidden meaning—the dialectical image is a powerful juxtaposition of conflicting and contradictory elements that “crystallizes antithetical elements by providing the axes for their alignment.”61 The image of Tantra is precisely this kind of juxtaposition of conflicting forces—or rather, a complex series of such juxtapositions—which brings together sex and spirituality, hedonism and transcendence, the profane and the sacred, even consumer capitalism and mystical ecstasy, in a variety of shifting configurations.

This dialectical image of Tantra, in turn, lies at the pivot of a complex play of representations and imaginary projections—a play of mimesis. As Michael Taussig defines it, elaborating upon Benjamin’s essay “On the Mimetic Faculty,” mimesis is the basic human power of imitation and representation of the Other. It is our capacity to grasp alterity, to make sense of the foreign or unknown, which takes place in all cultures and historical periods. But it becomes especially intense in periods of colonial contact, when cultures are dramatically confronted with a radical Otherness that brings domination and imperial control. The colonizing powers, for their part, construct a variety of imaginary representations of native peoples—as savage, primitive, feminine, emotional, or violent, rather than rational or scientific. Projecting their own deepest fears of disorder or subversion, together within their own repressed desires and fantasies, the colonizers construct a kind of negative antitype of themselves within the mirror of the colonized Other.62

And yet, particularly in cases of colonial contact, mimesis is a two-way street. Colonized peoples also have their own forms of mimesis, their own ways of imaginatively representing the colonial Other. Not only do they frequently mimic, parody, and satirize their colonial rulers in various ways, using the mimetic faculty to appropriate the mysterious power of the white man, but they also seize upon the imaginings of the colonizers, often by turning those notions on their heads and manipulating them as a source of “counterhegemonic discourse.” The play of mimesis is, in short, a complex back-and-forth dialectic of interlocking images, a “circulation of imageric power between selves and antiselves, their ominous need for and their feeding off each other’s correspondence.”63

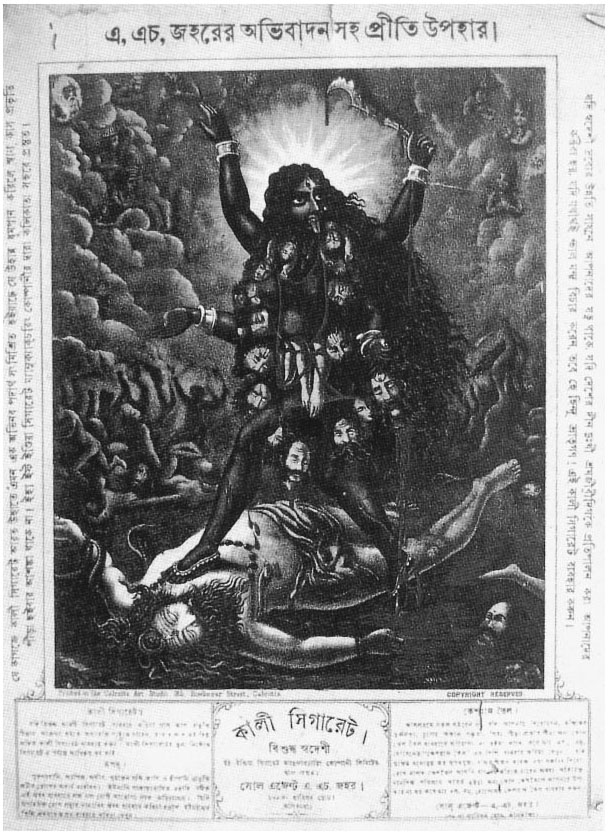

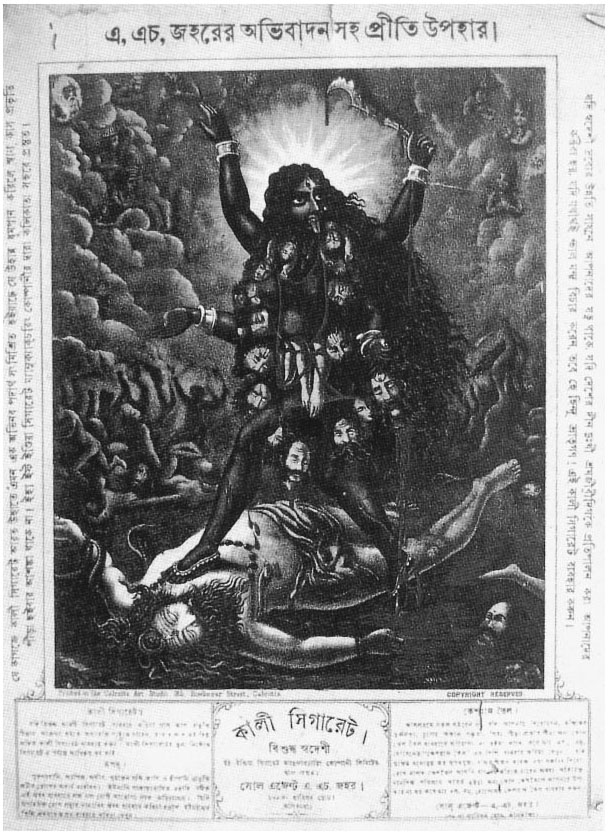

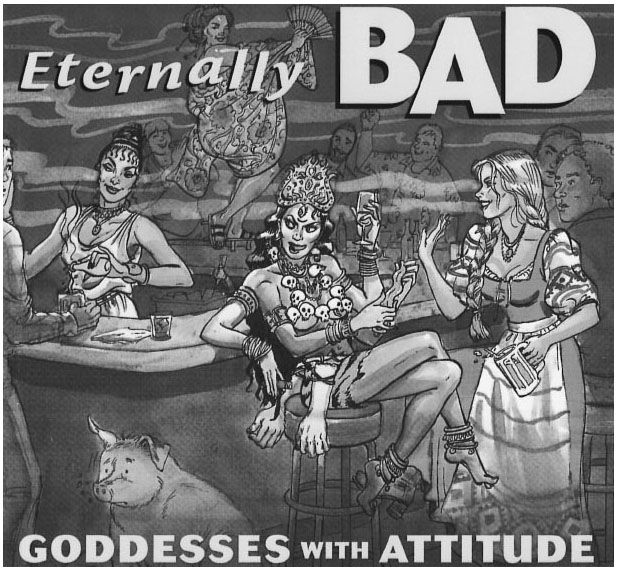

It is just this kind of circular play of images between Eastern and Western imaginings, I would suggest, that has given birth to the complex category of Tantra. And it is the ongoing dialectic of images that has led to the constantly shifting nature of the category, which assumes new valences in changing historical and social contexts. Like the concept of the primitive or the shaman, Tantra is a profoundly Janus-faced category: attacked in some historical periods as uncivilized or subhuman, and celebrated in other periods (particularly our own) as a precivilized “unsullied original state, a sort of Eden before the fall when harmony prevailed,” when sex was free and unrepressed, when the body had not yet been subjected to modern Western prudishness and hypocrisy.64 As we see, for example, in the strikingly “dialectical” image of Kālī (figures 1–3), Tantra lies at a nexus of contradictory forces at work between India and the West. For European Orientalists and colonial authorities, the image of Kālī was singled out as the most extreme example of the dangerous immorality and depravity that were running rampant in the subcontinent; yet for the radical leaders of the revolutionary movement in Bengal, this same image could be seized and exploited, transforming the Tantric goddess into a symbol of Mother India in violent revolt against her colonial masters (see chapter 2). In our own day, Kālī has been taken up by feminist writers, in both India and in the West, as a radical symbol of women’s liberation and empowerment (see chapter 6). I hope, then, to trace the tangled genealogy of these dialectical imaginings of Tantra as they have been transformed and reconfigured over the last several hundred years.

Figure 1. Illustration for Kālī Cigarettes, a nationalist brand. Calcutta Art Studio (1879).

There is no privilege to the so-called exotic . . . it is all history. There is no “other.” . . . Nevertheless the historian of religion will . . . gain insight from the study of materials which at first glance appear uncommon or remote. For there is extraordinary cognitive power in . . . “defamiliarization”—making the familiar seem strange in order to enhance our perception of the familiar.

Jonathan Z. Smith, Imagining Religion (1986)

We penetrate the mystery only to the degree that we recognize it in the everyday world, by virtue of a dialectical optic that perceives the everyday as impenetrable, the impenetrable as everyday.

Mirroring the dialectical, hybrid, and shifting nature of the category of Tantra, this book will proceed in a dialectical fashion, tacking back and forth between Western and Indian imaginations. Each chapter will be structured around the reciprocal exchanges, the reactions and counter-reactions, between East and West, as they have been played out in a series of key historical encounters. In so doing we will discover that the various discourses surrounding Tantra may not always tell us much that is terribly useful about any particular form of Asian religion, but they do tell us a great deal indeed about the concrete social, political, and moral contexts in which these discourses emerged. Indeed, the discourses about Tantra are an integral part of larger cultural and governmental issues—the ruling of British India, the regulation of the colonial body and its sexuality, the construction of a reformed Hindu identity, the fight for Indian independence, the politics of scholarship in the modern study of religions, and the global spread of consumer capitalism at the start of the millennium.

Figure 2. Kālī, goddess of destruction. From Augustus Somerville, Crime and Religious Belief in India (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink, 1931).

I begin, later in this introduction, with a brief genealogy of the term tantra in Indian literature, retracing the many tangled ways in which the “thread” of tantra has been stretched and interwoven throughout Indian history. Chapter 1 will then discuss the age of Orientalism, examining the first British depictions of Tantra and the ways in which they played into the colonial political programs and the sexual-moral ideals of Victorian culture. At the same time, I will also explore the many ways in which these images were in turn reappropriated and transformed by nineteenth-century Indian authors, for example, Rāmmohun Roy and the leaders of the Bengal Renaissance.

Figure 3. A modern Kālī. Cover illustration, by Mary Wilshire, for Trina Robbins, Eternally Bad: Goddesses with Attitude (Berkeley, Calif.: Conari Press, 2001). Courtesy of the artist.

In chapter 2, I will explore the political role of Tantra in the imaginations of the British authorities, particularly in their fears of criminal activity and the association of secret Tantric cults with revolutionary agitation. Indian revolutionaries of the early twentieth century in turn played upon and exploited those very fears, using Tantric imagery to express nationalist ideals and terrorist violence.

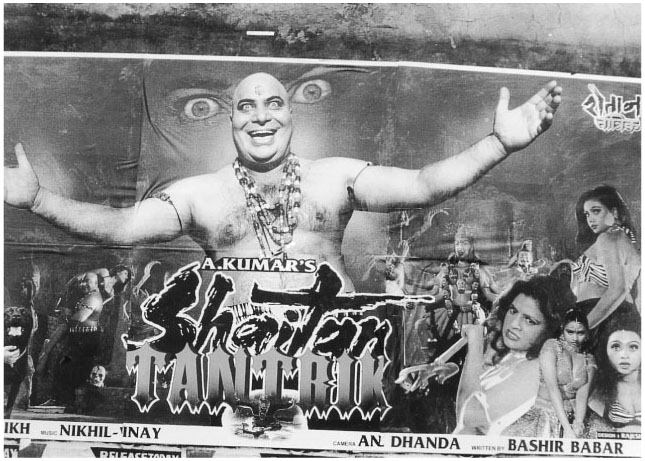

Chapter 3 will delve into the realm of the popular imagination, examining the often wildly exaggerated and exoticized image of Tantra in Victorian novels and Indian popular literature. Here I will explore the rich confluence of Orientalist constructions, colonial paranoia, and poetic license that fed into the literary portrayals, both Eastern and Western, of the seedy Indian underworld in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In chapter 4, I will examine the various attempts, on the part of both Western and Indian authors, to deodorize, sanitize, or reform Tantra. The most famous of these is the eccentric Supreme Court judge and secret tāntrika (practitioner of Tantra), Sir John Woodroffe, who is regarded as the founding father of Tantric studies. His legacy of reform and sanitization of Tantra would be mirrored and echoed in various ways by a great many Indian authors, such as Swami Vivekenanda and the disciples of Sri Ramakrishna.

Chapter 5 will then look at the “revalorized” place of Tantra—and perhaps even Tantro-centrism—in the work of twentieth-century historians of religions, such as Mircea Eliade, Heinrich Zimmer, and Julius Evola. As we will see, there were often many political—and in Evola’s case, explicitly fascist—ramifications in their scholarly reconstructions of Tantrism. However, we will also examine the role of Tantra in modern Indian scholarship, where it likewise has become a key part of various cultural and political discourses surrounding Indian national identity and even the rise of communism in regions like West Bengal.

Finally, chapter 6 will engage the increasing fusion between East and West, as in our own time Tantra becomes more and more a part of popular culture and New Age religion. I will examine the widespread popular impact of Tantra as manifest in the Tantrik Order in America, the “sex magick” of Aleister Crowley, the cult of Osho-Rajneesh, and the growing the search for Tantric ecstasy online, in the strange new world of cyber space. We might even say that the contemporary appropriation of Tantra—with its fusion of spirituality and materialism, sacred transcendence and this-worldly profit—has in many ways become the ideal religion of late-twentieth-century Western consumer culture, or perhaps even the “spiritual logic of late capitalism.”

In the conclusion I try to go beyond a mere deconstructive genealogy, offering instead some constructive comments as to how we might begin to reimagine the category of Tantra in contemporary discourse. Above all, I will argue, we need to move beyond both the early Orientalist horror of Tantra as a scandalous perversion and the contemporary celebration of Tantra as an affirmation of sensual pleasure. Instead, I will argue for a more historical, contextual, socially, and politically embodied approach to Tantra that roots these traditions solidly in their material circumstances and lived contingencies.

A very common expression in English writings is “the Tantra”; but its use is often due to a misconception. For what does Tantra mean? The word denotes injunction (vidhi), regulation (niyama), śāstra generally or treatise. . . . A secular writing may be called Tantra.

We cannot speak of “the Treatise” nor of “the Tantra,” any more than we can or do speak of the Purāṇa, the Saṃhitā. We can speak of “the Tantras” as we do of “the Purāṇas.”

Sir John Woodroffe, Shakti and Shākta (1918)

. . . as in spinning a thread we twist fibre by fibre . . .

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations (1958)

Given the profound ambiguity of the category and the conflicting Western interpretations of its content, perhaps we should begin with a brief analysis of the term tantra in Indian literature. Not only is tantra a kind of “floating signifier . . . gathering to itself a range of contradictory qualities”; but to use perhaps a more fitting Indian metaphor, tantra is a tangled “thread” that has been spun out, intertwined, and often snarled in myriad complex ways throughout the dense history of Indian religions.65

The historical origins of the vast body of traditions that we call Tantra are today lost in a mire of obscure Indian history and muddled scholarly conjecture. As Padoux observes, “the history of Tantrism is impossible to write” based on the sheer poverty of data at present.66 In what follows, I will by no means attempt to reconstruct this history—a formidable, perhaps hopeless task that has already been attempted by more capable scholars. Instead, I will try to retrace the complex genealogy of the term tantra itself, in order to show the diverse and heterogeneous body of concepts and traditions this term has been used to designate. For the sake of simplicity, I will focus here primarily on Indian, Sanskrit, and vernacular uses of the term tantra; I will not engage the interesting problem of related terms in other languages, such as the Tibetan rgyd, the Chinese mi-chiao, or the Japanese mikkyo, or the complex genealogy of tantra outside the Indian context.67

There is of course no lack of myths and legends about the origins of particular tantras. Many of the Hindu tantras offer their own narrative of a mythic origin, often in the form of the tantrāvatāra or “descent of the text,” in which Lord Śiva or the Goddess reveals the scripture. According to the narrative of the Tantrarāja Tantra, for example, the teaching was originally revealed by Siva to the supreme Śakti at the dawn of the first cosmic age; it was then transmitted through a series of nine Nāthas, or perfected masters, who descended in a chain from Siva’s realm to earth, through whom the tantra was revealed to humankind: “by these nine, the tantra was spread throughout this world; the Primordial Supreme Śakti revealed it in the Kṛta Yuga.”68

Meanwhile, contemporary scholars have come up with a variety of quasi-mythical origin-narratives of their own. The two most common ones are (a) the pre-Aryan/tribal–origin narrative and (b) the Vedic-origin narrative. The former had its origins in nineteenth-century Orientalist literature, was later popularized by historians of religions like Mircea Eliade, and has now become a standard trope in most New Age versions of Tantra. According to this view, Tantra is rooted in the ancient Indus Valley civilization, which is alleged to have been a matriarchal culture centering around goddess worship and fertility cults. With the coming of the Indo-Europeans or “Aryan invaders,” sometime around 1700 B.C.E., the story goes, sexual practices and goddess worship were pushed underground, where they survived as the “autochthonous substratum” of later Hinduism; only a millennium later did they resurface and work their way into the textual record. At the same time, Eliade and others have argued that Tantra is closely tied to non-Hindu, indigenous, and “aboriginal” traditions, such as the many tribal groups that survive today, above all in the marginal areas like Bengal, Assam, and the northwest mountains.69

The other common scholarly narrative takes the opposite stance. Since the time of Woodroffe, many defenders of the Tantras have argued that they are not only in continuity with Brahmanical Vedic traditions, but that they are in fact the very essence and inner core of Vedic teachings.70 This emphasis on the elite, nonpopular, and Sanskritic side of Tantra continues in a more nuanced form in much of the recent scholarship on Tantra. Downplaying its antinomian, radical, and transgressive aspects, many authors appear to have followed Woodroffe in trying to present a version of Tantra that is “not based upon a popular movement but was the outgrowth of the specialized position of an intellectual elite of religious functionaries from the upper classes, as a rule, of Brahmans.”71

Yet the genealogy of tantra, I think we will find, turns out to be far messier, more ambiguous, and more interesting than either of these scholarly narratives. In keeping with its etymological meaning of “stretching” and “weaving,” tantra will perhaps turn out to be less a unified singular entity than a series of complex threads that have been woven, spread out, and extended in manifold ways throughout the rich fabric of Indian history.

The poets stretched forth the seven threads to weave the warp and woof [of the ritual].

Ṛg Veda (RV 1.164.4–5)

The Sanskrit word tantra can be found in the earliest known texts of ancient India, appearing as a key term in the hymns of the Ṛg and Atharva Vedas (ca. 1500–1000 B.C.E.), and woven throughout the later history of Indian literature. Yet its meaning is by no means either simple or fixed. A number of authors have suggested possible etymologies for the term, some defining it as “shortening” or “reduction,” others tracing it to the noun tanu (body), and still others deriving it from tantrī (to explain) or tatrī (to understand).72 However, most scholars seem to agree (with Pānini, a Sanskrit grammarian) that the term probably derives from the root tan, which means basically to stretch, to spread, or to weave, and, metaphorically, to lay out, to explain, or to espouse.73 As William Mahony suggests, the imagery of thread and weaving is one of the most evocative themes throughout the early Vedic literature; it is used to describe both the language of the Vedic poets, who “weave their words out of the fabric of a timeless language,” and the creation of the universe out of the supreme Brahman, which is likened to “the finely drawn thread on which creatures are woven” (AV 10.8.38).74 Perhaps most significantly, tan is a key verb used in the classic cosmogonic hymn (RV 10.90), which describes the origin of the universe out of the sacrificial dismemberment of the primordial man, Purusa. The body of Purusa is divided up and “spread out” into the parts of the universe, just as a thread is spun and woven by a loom: “When the gods spread out [atanvata] the sacrifice with the Man as the offering, spring was the clarified butter, summer the fuel, autumn the oblation. . . . [T]he gods, spreading the sacrifice, bound the Man as the sacrificial beast” (RV 10.90.6, 15). Hence, as Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty notes, this key verb tan is used simultaneously to refer to the performance of the sacrifice, which is spread out over the ritual ground, and to the origin of the universe, which is “spread upon the cosmic waters, or woven, like a fabric.”75

The Upaniṣads (700–400 B.C.E.) continue this play upon the imagery of weaving evoked by the root tan, adding to it the metaphor of the spider spinning its threads (tantu). Just as a spider covers itself with its own web, so too “the one God covers himself with things issuing from the primal source . . . as a spider with the threads [tantubhih].”76 “As a spider sends forth its thread . . . so do all the vital functions, all the worlds, all the gods and all beings spring forth from this Self.”77 Thus all of reality, along with the sacred language that reflects it, is the product of this stretching out of the One into the variegated fabric of the universe.

Derived from this seminal root tan, the noun tantra is thus first used in the Vedic hymns to denote a kind of weaving machine, a loom or, specifically, the warp and woof (RV 10.71.9; AV 10.7.42). Even here, however, it often has the extended meaning of the “weaving” of speech: the visionary poets who composed the Vedas wove them with the threads of words as if upon a loom. However, as J. C. Heesterman points out, tantra as “loom” is also a metaphor standardly used for the sacrificial ritual, which is similarly stretched and spread out through the many interwoven threads of the ritual acts.78 As the Ṛg Veda puts it:

The sacrifice that is spread out with threads on all sides, drawn tight with a hundred and one divine acts, is woven by these fathers as they come near: Weave forward, weave backward, they say as they sit by the loom that is stretched tight. The Man stretches the warp and draws the weft; the Man has spread it out upon this dome of the sky. (RV 10.130.1–2)

Later, in the Brāhmaṇas (ca. 1200–900 B.C.E.), tantra is extended from the sense of “weaving words” and “weaving rituals” to a more abstract level, whereby it refers to the essential part of a thing, the main point or characteristic feature of a given system.79 And by the period of the great Sanskrit epic the Mahābhārata (ca. 500 B.C.E.–500 C.E.), the range of tantra has been expanded to refer simply to “any rule, theory, or scientific work” (13.48.6). Thus, later authors like the great philosopher Śaṇkara use tantra simply to refer to any system of thought (e.g., Kapilasya Tantra, meaning the Sāṃkhya system).80 However, according to Sir Monier-Williams, the term would eventually be extended and used throughout Sanskrit literature in an almost infinite variety of ways, to denote everything from “an army, row, number or series” (BP 10.54.15), to a magical device or diagram (often synonymous with yantra) to “a drug or chief remedy.”81

But perhaps most commonly, tantra is used much like the term sūtra, which derives from the verb suc, “to sew,” to designate a particular kind of discourse or treatise. According to one common definition, a tantra is simply “a scripture by which knowledge is spread” (tanyate vistāryate jñānam anena iti tantram)—a text, however, that may or may not contain any of the secret and transgressive materials that today we think of as Tantric (for example, the Pañcatantra, a popular collection of fables).82

In sum, as Padoux observes, the substantive noun “Tantrism” appears nowhere in Indian literature prior to the modern period. It is “assuredly a Western creation,” with a fairly recent history.83 However, we do find the adjective tāntrika, which has been used sometimes as a counterpart and contrast to the adjective vaidika (Vedic, pertaining to the Vedas). One of the passages most often cited by modern scholars is a brief one in Kullūka Bhaṭṭa’s commentary on the Laws of Manu, “revelation [śruti] is twofold, vaidika and tāntrika.”84 In other words, revealed scripture can be classified into that which belongs to the traditional canon of the Vedic texts and that which appeals to an extra-Vedic source of authority. Yet, rather oddly, despite the frequency with which this passage is cited by modern scholars, Bhaṭṭa does not elaborate this point at all beyond this one terse statement and provides no further explanation of what tāntrika means. Moreover, this vaidika/tāntrika distinction by no means resolves the semantic muddle presented by tantra. If anything, it only compounds it a hundredfold, for now tāntrika seems to be a generic term referring not just to what we today think of as Tantra, but to all non-Vedic texts that claim revealed status. So we are left wondering how to distinguish Tantra as a category apart from any other Indian literature that claims an extra-Vedic origin and authority.

Some of the Purāṇas also use the vaidika/tāntrika distinction to describe the primary ways of worshiping of the deity, in accordance with different social and spiritual types (see BP 11.3.47). According to the Padma Purāṇa, vaidika worship is prescribed for Brahmans and the other twice-born classes, while tāntrika offers even lowly śūdras a way to worship God: “The worship of Viṣṇu is of three kinds: as laid down in the Vedas, as laid down in the Tantras, and mixed. The vaidika or the mixed one is laid down for brāhmaṇas and others. The tāntrika is enjoined for even a śūdra who is Viṣṇu’s devotee.”85 Yet quite strikingly, these texts do not associate tāntrika with any of the sexy, scandalous, or transgressive practices that we associate with the term; nor do they identify tāntrika worship with those deviant sects—such as the Kāpālikas, Pāśupatas, and Vāmas—who are, elsewhere in the Purāṇas, vilified as dangerous and deluded cults, and who are typically identified by modern scholars as quintessential tāntrikas.

Since it is unalterably present, like the sky (in everything) beginning with sentient beings and ending with Buddhas, it is termed “Tantra as actuality” because of its continuousness.

Padma dkar-po (trans. Guenther, The Tantric View of Life)

As for the smile, the gaze, the embrace, and the union, even by the tantras the secret language of these four is not mentioned.

Hevajra Tantra (HT 2.3.53–54)

Given the incredible semantic polyvalence of the term tantra in Sanskrit literature, we might wonder if we can find any clearer definition of the term within the tantras themselves. There is of course a vast body of texts called tantras, as well as related texts called yāmalas, āgamas, nigamas, and saṃhitās, which spread throughout the Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist communities over the past twelve hundred years. The Tibetan canon, for example, preserves almost five hundred such texts, along with over two thousand commentaries and interpretive works. Within the Hindu tradition, we find tantras composed by the Vaiṣṇava Pāñcarātra school, the lost tantras of the Sauras, as well as the more famous tantras of the Saivites and Śāktas. Tantras are found in more or less every corner of the subcontinent, with powerful strongholds in the northeast (Bengal, Orissa, and Assam) and the northwest (Kashmir), and later spreading to the far south (Tamilnadu and Kerala). Buddhist tantras would eventually spread not only throughout India, but also to Nepal, Tibet, China, Japan, and parts of Southeast Asia.86

Yet precisely when or where these texts emerged is largely a mystery. In fact, we cannot find any concrete reference to Hindu texts called tantras until the ninth century, at the earliest; the tantras are nowhere mentioned in the Mahābhārata, which claims that there is nothing in the world that is not contained within it; nor do any of the early Chinese pilgrims to India make any reference to the tantras. Even more striking is the fact that none of the great compendiums of Indian philosophical systems—such as Mādhava’s Sarvadarśanasaṃgraha (fourteenth century) or the Sarvasiddhāntasaṃgraha—contains any section on Tantra, even though they do contain discussions of specific traditions such as āgama, pratyabhijñā, and so on.87

The earliest known reference to texts called tantras seems to lie in Bāṇabhaṭṭa’s classic fantasy tale, Kādambarī (seventh century), where we meet a strange, crazy, and rather comical old sādhu (holy man) from South India, who “had a collection of palm-leaf manuscripts, tantras and mantras.” Yet we are told virtually nothing about these manuscripts, nor is it clear exactly what tantra means in this context.88 Thus, as Gupta and Goudriaan admit, “the existence of the Hindu Tantras cannot as yet be proved for the period before 800,” when we find the oldest epigraphic mention of specific tantras. According to an inscription of Sdok kak Thom in Cambodia, at the beginning of the ninth century (802?), King Jayavarman II’s court priest Śivakaivalya installed a royal cult based on the doctrine of four tantras brought from elsewhere. Of these texts, named as the Śirascheda, Nayottara, Sammohana, and Vīṇāśikha Tantras, only the last survives.89

There has also been a long, heated, and never resolved debate over the question of the primacy of Hindu or Buddhist Tantra. Scholars on both sides have argued fiercely for either a Buddhist or Hindu basis for Tantra, with some arguing for Vedic origins and others for inherently non-Vedic roots within the Buddhist tradition.90 But in any case, it seems likely that the oldest known texts called tantras are the Buddhist Guhyasāmāmaja Tantra and Hevajra Tantra. The older of these, the Guhyasamāja, has been dated anywhere from the third to the eighth century.91 Even here, however, the use of the term tantra is by no means either clear or particularly helpful in understanding the category of “Tantrism.”92

In one terse and cryptic passage, we are told that tantra can be defined as prabandha. This term prabandha, in turn, is one that carries a wide range of meanings, denoting everything from a “ligament” to a “poetic composition”; but here it seems to mean something like “continuity” or “continuous series.” And this continuous series consists of three things: “Tantra is explained as ‘continuity’; that continuity is threefold, divided into Ground [ādhāra], Nature [prakṛti], and Inviolability [asaṛhārya]. Nature is the Cause; Inviolability is the Fruit; and Ground is the Means—thus the threefold meaning of tantra” (GST 18.34–35).93 According to the interpretations of later Tibetan commentators, the threefold “continuous series” here is the progress of the initiate along the path to nirvāṇa. It is the path that leads from the unenlightened state, through the means of spiritual practice, to the fruit of awakening or Vajradhāra (“diamond bearer”): “The Tantra shows the continuous progress of a candidate (Tantra of Cause) along the Tantric Path (Tantra of Means) to the high goal of Vajradhāra (Tantra of Fruit).”94 Tantra thus seems to be the “thread of continuity” that carries the disciple along the path from ignorance to liberation.

When we turn to the second early Buddhist tantra, the Hevajra, which probably reached its final form by the eighth century, we find other occasional uses of the term tantra. Indeed, the Hevajra itself claims to be the revelation of the inner core of all the tantras—“That which is concealed in all the tantras is here finally made manifest” (HT 2.5.66), now revealed by Lord Buddha as the heart of all the most esoteric practices: “Then the adamantine Lord spoke to the yoginīs of the Means, which are the basis of all tantras [sarvatantranidānam], of the Union, of consecrations, and of secret language, of the different Joys and moments, of feasting and the rest” (HT 2.3.1). Yet it seems clear that in both the Guhyasamāja and in the Hevajra, tantra is not used to refer to a unique religious movement or overarching category; it simply refers to a kind of text, and thus to one of the many elements that comprise the path to liberation, neither more nor less important than the other meditations, rites, or initiations.95

In general, it would seem that the term tantra is not the one most often used in Buddhist literature; much more common are the terms Vajrayāna (diamond or thunderbolt vehicle) or Mantrayāna (mantra vehicle), which designate a new spiritual path, going beyond both the Hīnayāna (lesser vehicle) and the Mahāyāna (great vehicle) (GST 5). Yet even these are by no means easily defined terms. As Dasgupta comments, all we get from the Buddhist literature are “mere cursory descriptions, none of which suggests any correct definition of Vajrayāna. In fact, Vajrayāna cannot be defined; for it incorporated so many heterogeneous elements that any attempt at strict definition would be futile.”96

Eventually, the Vajrayāna Buddhists would elaborate a hierarchical classification of texts into four kinds of tantras. This is often traced back to one cryptic passage in the Hevajra Tantra, which speaks in very elusive terms of the four gestures—the “smile,” “gaze,” “embrace,” and “union”—which are said to be even more secret than all the tantras: “What may be said of the secret language, that great convention of the yoginīs, which the śrāvakas (disciples) and others cannot unriddle? . . . As for the smile, the gaze, the embrace, and the union, even by the tantras the secret language of these four is not mentioned” (HT 2.3.53–54).

Although it is by no means clear what the precise meaning of this verse might be, it had become common by the time of the great Tibetan theologian and founder of the dGe lugs pa school, Tsong-ka-pa (1357–1419), to associate these enigmatic “gestures” with four classes of tantras. Thus we have a progression of kriyā (action), caryā (practice), yoga, and anuttara-yoga (supreme yoga) tantras, revealed through a series of increasingly esoteric consecrations. However, as Tucci points out, this well-known fourfold division of the dGe lug school was by no means the only way of carving up the vast body of Vajrayāna literature; rather, there were a variety of fourfold, fivefold, sixfold, and other divisions common in different schools.97

In sum, it would seem that the Buddhist literature provides us neither with a clear definition of tantra nor with a simple or consistent classification of all the many texts called tantras. As Lopez concludes in his own insightful deconstruction of the term in the Buddhist tradition, tantra perhaps cannot be understood as any kind of substantive, unified category by itself; rather, it seems to function in a contrastive relation to the term sūtra. The path of the tantras is thus a kind of “supplement” to the path of the sūtras, just as the Vajrayāna imagines itself to be the supplement to the Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna traditions.98

A tantra always spreads and saves . . .

[tanute trāyate nityaṃ tantramithaṃ . . .]

Piṅgalāmata (1174)

It should be carefully kept secret, this essence of the tantras which is difficult to obtain [gopitavyaṃ prayatnena tantrasāraṃ sudurlabham].

Vīṇāśikhatantra (VST 312)

When we turn to the Hindu tradition, we find little help in discerning a clear or simple definition of tantra. It is true, of course, that many Hindu texts do speak of the “essence of the tantras” (tantrasāra), the “essential meaning discussed in the tantras” (tantrapratipādyam arthatattvaṃ), and the “established truth of the tantras” (tantra-siddhānta) (NUT 1.1; VST 100). Yet one is hard pressed to find any clear definition of tantra in these texts, much less any notion of larger movement or tradition conceived as “Tantrism.”

The Vaiṣṇava Pāñcarātra tradition, for example, produced a large body of esoteric ritual and philosophical texts beginning around the fifth century. As F. Otto Schrader points out, the Pāñcarātras use tantra interchangeably with the more common term saṃhitā to refer to particular compositions; both terms, moreover, are used rather generically to refer to “the main topics of a philosophical or religious system”; for example, “Pāśa Tantra,” meaning the Pāśupata school of Śaivism. Thus the Pāñcarātra text Ahirbudhnya Saṃhitā (AS 60.20) describes itself as tantrasāra, which Schrader renders simply as “the essence of philosophy.”99

Many later texts of the Śaiva and Śākta schools do give us occasional hints as to possible definitions of the term tantra. According to one often-cited definition that appears in the Kāmika Āgama, “It is called ‘tantra’ because it promulgates great knowledge concerning Truth and mantra, and because it saves [tanoti vipulān arthāṃs tattvamantrasamāśritān/trā-ṇaṃca kurute yasmāt tantram ityabhidhīyate].”100 Other texts, such as the Svacchanda Tantra, also give some partial definition of the adjective tāntrika. For example, one who pursues the tāntrika method or way (tāntriko nyāyah) is described as follows: “He by whom the senses are conquered and whose mind is fixed . . . he whose intellect is still with regard to his own affairs or those of others . . . this, in short, is said to be the tāntrika method” (SvT 10.71–73). The Niruttara Tantra also uses the vaidika/tāntrika distinction to contrast the consecration ceremony of kings with that of the truly wise (jñānins). Whereas royal consecration is based on Vedic injunctions, the esoteric consecration of truer knowers is concealed in the tantras. “The consecration of kings follows the vaidika procedures; but the consecration of the truly wise is hidden within all the tantras. The wise perform the consecration by preparing the kula cakra” (NUT 7.2–3). Yet none of these definitions indicates that these authors think of themselves as belonging to a particular school, movement, or religious tradition called “Tantrism.” And the definitions they provide of tantra, as a text which spreads knowledge and saves, or tāntrika, as a method based on conquering the senses and stilling the mind, do little to distinguish this from any other yogic path aimed at spiritual liberation.

However, if the authors of the tantras don’t seem to think of themselves as belonging to a “Tantric tradition” or to Tantrism as a distinct movement, they do think of themselves as belonging to other sorts of traditions and lineages: that is, they describe themselves as Śākta (worshipers of Śakti), Śaiva (worshipers of Śiva), Krama (literally, “gradation,” “method,” or “way”), or Trika (“triadic”), but not typically as “Tantric.” Among the most important of these schools is the Kula, which is often identified with the semimythical Siddha Matsyendranāth (see TA 29.32).101 Thus the classic Kulārṇava Tantra, one of the most influential tantras of the medieval period, speaks frequently of the kula path (kulamārga), kula dharma, kula scriptures (kulaśāstra), and “Kaula” is used as a substantive noun for the tradition as a whole (KT 1.119, 12.43, 2.23, 11.98). In several places we find a hierarchy of schools, ascending from the Vedic, to the Vaiṣṇava, to the Śaiva, to the highest path of Kaula:

Vedic worship is greater than all others. But greater than that is Vaiṣṇava worship; and greater than that is Śaiva worship; and greater than that is Dakṣiṇācāra. Greater than Dakṣiṇācāra is Vāmācāra; and greater than Vāma is Siddhānta; greater than Siddhānta is Kaula—and there is none superior to Kaula. Devī, this Kula is more secret than secret, more essential than the essence, greater than the supreme, given directly by Śiva, proceeding from ear to ear. (KT 2.4–9; cf. NUT 1.13, 1.25)102

Yet nowhere here do we find “Tantrism” imagined as a coherent movement or school.

Many later works would eventually attempt to construct some sort of classificatory schema in order to organize all of the various literature proliferating under the titles of āgama, nigama, tantra, yāmala, and so on. Thus, we find a number of varying lists of the major texts: for example, the Navamīsiṃha mentions forty-nine tantras, seventeen saṃhitās, eight yāmalas, four cūḍāmanis, three pāñcarātras, and more. However, probably the most common way of carving up the vast territory covered by these various traditions is the threefold division into saṃhitā, āgama, and tantra. Thus the saṃhitās of the Pāñcarātra school are traditionally said to be 108 in number, the āgamas of the Śaivas said to be 28, and the usual number for the tantras is held to be 64 (VST 9). Yet there is significant disagreement as to precisely which texts belong among these tantras.103 Such formalized lists of texts are quite common in Hindu literature, and can also be seen in the enumerations of the principle Upaniṣads or the lists of the eighteen major Purāṇas.104 However, as Woodroffe pointed out, this by no means indicates existence of a distinct religious movement or tradition; no one, for example, would use a term like “Purāṇism” to describe the wide range of philosophical systems and devotional traditions covered in the vast body of literature called Purāṇas.

Just as stars, remaining in the clouds, do not shine in the sunlight, so too the tantras of the siddhāntas do not shine in the kula āgama [siddhāntatantrāṇi na vibhānti kulāgame].

Jayaratha (TAV 1.6)