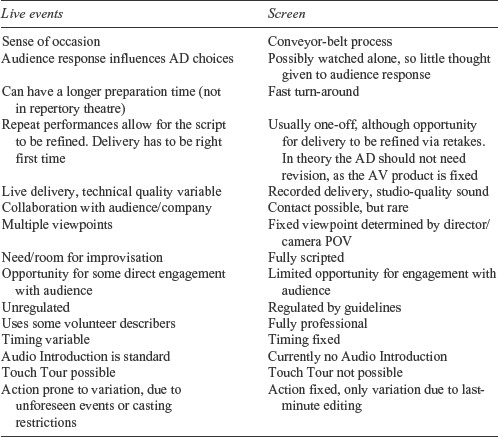

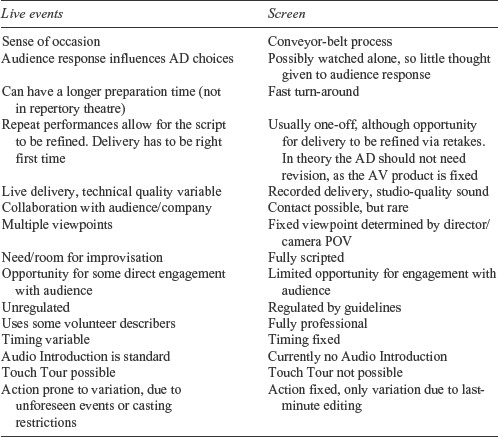

Table 2.1 Differences between AD for live events and screen AD

2 A brief history, legislation and guidelines

This chapter examines the formal side of AD, namely the legislation that governs it and its development in different countries. It also contrasts the two forms with which this book is concerned: AD for screen and AD for live events. It stresses that BPS people have often been instrumental in fostering the development of AD. Although legislation has also been crucial, the practice is unregulated in many contexts, leaving the specifics open to evolution and debate. This has been to the advantage of (unregulated) live AD, allowing it to be more creative and adventurous.

Although many believe that the history of AD can be traced back to the United States, Díaz Cintas et al. (2007) claims its first reported use was in Spain in the 1940s. More recent research has uncovered an article from 1917 in the RNIB’s journal The Beacon (ADA, 2014) reporting how Eleanor, Lady Waterlow, wife of the English watercolour painter Ernest Waterlow, enabled soldiers blinded during the First World War to enjoy a ‘cinematograph lecture’ about Scott’s expedition to the Antarctic by describing the images. The same article also reports that ‘experiments at theatrical performances had already met with success’, so the origins of AD may date back further and be more diverse than previously thought. The first AD transmission on TV was in 1983 by NTV a commercial broadcaster in Japan (ITC, 2000). Japanese benshi (live performers) had been adding a verbal commentary to make silent films accessible from the dawn of cinema (Washburn and Cavanaugh, 2001). The art of the film explainer was not limited to Japan (Marcus, 2007) but also included Germany, the Netherlands and Scotland. Arguably, these lecturers did not actually explain films but made them accessible to audiences who were not sufficiently literate to read the intertitles or to understand the ‘language of cinema’. With the advent of talking cinema, film explainers gradually became redundant.

AD, in the sense of a sighted person painting a verbal picture for a friend or family member with impaired vision, has taken place informally for hundreds if not thousands of years. But as American AD pioneer Margaret Pfanstiehl has pointed out, ‘doing it in a prepared scheduled way is of course quite another matter’ (Pfanstiehl and Pfanstiehl, 1985: 92). Margaret Pfanstiehl had a direct impact on live AD in the UK, although AD for screen in the UK arguably owes its existence to another American, Gregory Frazier. He was a professor at San Francisco State University who developed what he called ‘television for the blind’ for his Master’s thesis in the 1970s. In the early 1980s, Margaret Ptfanstiel applied Frazier’s ideas and began a live service for the Arena stage in Washington, extending the reading service she had established for the blind, called The Washington Ear. The first play to be audio described was Major Barbara by George Bernard Shaw. In England, Monique Raffray, who worked for the South Regional Association for the Blind, was on the editorial board of the British Journal of Visual Impairment, and who was herself blind, read about The Washington Ear in the bulletin produced by a BBC radio programme In Touch that deals with matters of blindness. Together with her colleague Mary Lambert, Monique determined to bring AD to the UK and they corresponded with the Pfanstiehls. Mary visited the Pfanstiehls in Washington in 1987, attending an audio-described performance of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Cats. The previous year, the RNIB had set up a working party on AD. An informal described performance of A Delicate Balance by Edward Albee took place at the Robin Hood theatre in Averham, near Newark, in 1986. Although this is sometimes cited as the first audio description in the UK, in an email sent to the author on 16 April 2015 Mary Lambert stressed the description’s informal nature, as the describers did not have proper equipment: ‘I seem to remember we had a box on our laps, and obviously some headphones. I remember the describer . . . saying at the appropriate time, “Mary and Monique, it’s time to leave for your train” and we had to “creep” out of the theatre and get our cab!’

Mary Lambert states that the first UK description was of the musical Stepping Out at the Theatre Royal, Windsor, in November 1987. Over the next five years, theatre AD proliferated in the UK, coming to the Duke of York Theatre in London in February 1988 and the West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds in September 1991. Other early adopters were the Chichester Festival Theatre; the Churchill Theatre, Bromley; The Octagon Theatre, Bolton; The Citizens Theatre, Glasgow; The Sherman Theatre, Cardiff; and the Derby Playhouse. The development of AD was supported and fostered by the RNIB’s Working Party on Audio Description, energetically championed by Marcus Weisen (incorrectly named as Marcus Weiss in some sources, e.g. Orero [2007]).

At first, all describers in the UK were volunteers, until the National Theatre of Great Britain decided to train a group of professional actors, believing that an understanding of the medium was essential for AD quality. Training at the National Theatre of Great Britain was carried out by Diana Hull and Monique Raffray. Diana had been on a study visit to the USA with a particular focus on training. Forty-five visually impaired people attended the first description at the National Theatre of Great Britain of Trelawney of the Wells in March 1993. Currently, theatre AD in the UK is delivered by a mixture of volunteer and professional describers. Some theatres offer little more than an honorarium, others pay a more reasonable freelance rate. Fees vary not only from theatre to theatre but even within the same venue, taking into account the number of described performances in a show’s run and the fact that some shows take longer to prepare than others. The process is outlined in Chapter 6.

After AD for theatre, AD for screen soon followed. In the USA in 1987, the broadcasting station WGBH in Boston set up its ‘descriptive video’ service. In Europe the pilot TV audio description service AUDETEL was organised in the early 1990s by a conglomerate of European broadcasters, academics and the RNIB (Lodge, 1993). In 1994, the RNIB established its home video service. This was a library of videos with audio description mixed onto the soundtrack.

Just as with subtitles or captions, there are two methods of delivering AD: it can be ‘open’, so that everybody hears it, or it can be ‘closed’, i.e. carried on a separate sound channel accessed by headset only by those who need it. In the theatre the AD content may be delivered to a headset on a short-range radio frequency or via an infrared signal in the auditorium while users listen to the dialogue either on the same headset or direct from the stage. There are pros and cons. Listening to the show sound on the headset means that it can be heard at an enhanced volume, if required; however, the AD user can feel cut off from the rest of the audience. It is essential that the volume of the AD can be controlled independently from the volume of the show sound. Otherwise, in a loud show, it is not possible to make the AD sufficiently loud that it can be heard over the top. On DVD, AD (where available) can be selected, commonly from the languages menu. On digital TV, AD can usually be accessed via the audio button on the remote control.

The quantity of live AD in the UK increased in 1998 with the arrival of VocalEyes, founded by one of the National Theatre of Great Britain describers, Andrew Holland, together with James Williams, who was the Executive Director of the theatre company Method & Madness. VocalEyes was funded by Arts Council England, and its aim was to describe touring productions so that the AD would not have to be reinvented for each venue. From this beginning, VocalEyes expanded into descriptions for West End Theatre, of dance and ballet and of the visual arts. By the summer 2013, VocalEyes had described over 1,500 performances at over 100 different venues around the UK.

Currently around ninety-nine theatres in the UK regularly provide audio described performances (RNIB, 2015). This number is hard to confirm because there is little consensus as to what constitutes a theatre. Impromptu ‘fringe’ venues, for instance, may spring up for short periods only. Also the frequency of described performances varies: there may be just one described performance or several in a production’s run. For long-running shows in the West End of London, such as The Lion King (dir. Taymor, 2000) or Billy Elliot (dir. Daldry, 2005) for example, a couple of performances may be described each year. Although the AD is in some senses repeated, the describers always deliver the description live to accommodate slight variations in performance. While they are expected to write a script (covered in detail in Chapter 5), they must also be prepared to improvise when, for example, an actor forgets his or her lines, mislays a prop or introduces a spontaneous piece of stage business, or some feature of a complex set breaks down. In Spain and in the USA there have been some attempts to use pre-recorded AD, accessed via a mobile phone app (Snyder and Padro, 2015). This is easier for shows with a pre-recorded soundtrack, such as Cirque du Soleil, so that the AD can be kept in synch. Apps are also being trialled to help more people receive AD in cinemas (RNIB, 2015) via their tablet or mobile phone. In France, pre-recorded AD for live shows is the norm.

Table 2.1 Differences between AD for live events and screen AD

Table 2.1 sets out some of the main differences between describing for live events and screen AD. One key difference between the two is that a film or TV programme has been directed and the camera shots determined, so that the audience all share a single point of view (POV). In the theatre the describer is free to select which part of the stage picture they will describe. In addition, the duration and location or ‘gaps’ where an audio-descriptive utterance might be inserted is fixed for AV media, but the length and position of those ‘gaps’ may change from one live performance to another. In situations where apps have been trialled, the AD is synchronised with a show’s recorded soundtrack (Snyder and Padro, 2015). In such cases, the AD is synchronised with a show’s recorded soundtrack (Snyder and Padro, 2015). Alternatively, AD for live events is pre-recorded but triggered live, its delivery cued by a member of the stage crew, such as the stage manager. The variability of this ‘window’ in which AD can be delivered has implications for the way in which AD script is constructed (see Chapter 6). Often, and in accordance with the original model disseminated by the Pfantstiels, two describers will prepare and deliver the live description. In smaller venues there may be only one describer. Wherever possible, best practice involves feedback from at least one BPS person during the preparation process. In TV AD, Bayerische Rundfunk in Germany and Italy’s Sensa Barriere, consistently involve blind people at the preparation stage, while some AD scripts in Poland are also created by a mixed team (one sighted and one blind describer) (Mazur and Chmiel, 2012).

The growth of AD in the UK has been significantly assisted by legislation. The Disability Discrimination Act (DDA, 1995; updated 2005) made it unlawful for any organisation or business to treat a disabled person less favourably than an able-bodied person. Businesses were required to make ‘reasonable’ adjustments, such as installing wheelchair ramps or altering working hours. For BPS people, reasonable adjustments included providing information in an audio format or Braille or offering an AD service for films, plays and exhibitions. This provision was carried over into the Equality Act, which replaced the DDA in 2010. In the wake of AUDETEL, the Communications Acts (1996, 2003) required digital terrestrial broadcasters to audio describe a prescribed percentage of their programmes. While the quota for programmes to be subtitled for people who are deaf or hard of hearing (SDH) was set at 60 per cent after five years of a digital terrestrial channel’s coming into service, for AD the quota was only 10 per cent. This reflected the paucity of affordable technology available to receive the service. The arrival of digital platforms has improved this, yet the quota has remained unchanged. Several channels in the UK voluntarily exceed the legal quota: Sky, for example, currently describes around 20 percent of its programmes (Sky, 2015). A few channels are exempt, for example BBC News. The effects of programme genre on AD are discussed in Chapter 8. Since 2001, the Canadian Radio Television and Telecommunications Commission has made it compulsory for an AD commitment to be made before it renews broadcasting licenses.

It remains to be seen whether media laws have teeth. In Australia, in July 2015, a blind woman launched ‘a case of unlawful discrimination against the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) for their failure to provide audio description as part of their regular programming’ (Blind Citizens Australia, 2015).

In Europe, the Audiovisual Media Directive 2007/65/EC acknowledges that:

Cultural activities, goods and services have both an economic and a cultural nature, because they convey identities, values and meanings, and must therefore not be treated as solely having commercial value . . . regulatory policy in that sector has to safeguard certain public interests, such as cultural diversity, the right to information, media pluralism, the protection of minors and consumer protection and to enhance public awareness and media literacy, now and in the future.

Member States shall encourage media service providers under their jurisdiction to ensure that their services are gradually made accessible to people with a visual or hearing disability. Sight- and hearing-impaired persons as well as elderly people shall participate in the social and cultural life of the European Union. Therefore, they shall have access to audiovisual media services. Governments must encourage media companies under their jurisdiction to do this, e.g. by sign language, subtitling, audio-description . . .

In addition to the European Union, legally enshrined responsibilities for AD also exist in the USA (21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act, 2010), which prescribes four hours of described programmes per TV channel per week. Within Europe numerous countries have their own legal obligation to provide AD, including Germany (Rundfunkstaatsvertrag), Poland (Polish Radio and Television Act), Spain (2009 Ley general audiovisual) and Flanders in Belgium (Mediadecreet, 2013). Portugal’s Television law (2011) is no longer in effect, although its public broadcasters have long been required to fulfill quotas for subtitling and AD. Legislation was introduced in Finland at the start of 2014. Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR) was the first public radio and TV broadcaster in Germany to introduce a regular description service. There is more information about the development of European AD services on the following website: http://hub.eaccessplus.eu/wiki/Audio_description_in_Europe.

Increasingly, AD is expanding beyond Europe and North America, reaching Iceland, Thailand and Korea. Dawning Leung (2015) states that, in the last few years, AD services haves been regularly provided in Hong Kong and on Mainland China, although in the latter ‘AD services seem to be very limited, and restricted only to films’.

Although AD has developed at different rates and been applied to different art forms at different times in different countries, a common theme in its instigation has been lobbying by user groups or by an individual describer, or when individuals involved in the relevant production company have a particular interest such as having a family member who is blind. From this, we might conclude that the concept of AD is mystifying in the abstract (as Jankowska (2015: 52) says, ‘a blind viewer sounds like an oxymoron’) but its benefits are self-evident to anyone with direct experience of visual impairment.

European legislation distinguishes between linear and non-linear services, with the latter referring to non-traditional services where the user can ‘pull’ programmes of their choice (on demand) and the former being more traditional services that are ‘pushed’ to viewers. Non-linear services have recently become more accessible, following the decision of Netflix to caption all of its content by the end of 2014 (Nikul, 2015). This was the result of legal action on the part of the American National Association of the Deaf, and a commitment to audio-describe selected titles was announced in April 2015. The director of content operations at Netflix, Tracy Wright (2015), stated that, ‘Over time, we expect audio description to be available for major Netflix original series, as well as select other shows and movies. We are working with studios and other content owners to increase the amount of audio description across a range of devices including smart TVs, tablets and smartphones.’ It’s a fast-changing scene. According to a report into video on demand (VOD) by Media Access Australia,

The only VOD providers to currently provide audio description are the BBC’s iPlayer, 4oD (which provided audio description on 15% of programmes in 2014), Channel Entertainment (7% of programs in, 2014) and Sky (which did not provide comprehensive figures to the regulator, the Authority for TV on Demand (ATVOD). Channel 5 and ITV have expressed an intention to introduce the service. ATVOD states that encouraging the provision of audio description will be a particular focus for it in 2015.

(Nikul, 2015: 8)

The importance of VOD services is that they are less constrained than traditional broadcast services, allowing, for example, for the provision of extra information such as audio introductions (see Chapter 12). This is being trialled for hybrid services by the HBB4All (Hybrid Broadband Broadcasting for All) project (http://www.hbb4all.eu/).

Despite the dual focus of this book – both on-screen and live description – in practice the bulk of AD is produced for screen media, in particular film and TV. It is in these industries that graduates from programmes in AVT are most likely to find employment. In the UK, the first commercial AD units were formed in London in 2000, and the first-audio described cinema releases in the UK followed in 2002. Currently, AD in the UK is produced by translation bureaux and facilities houses, including Deluxe, Ericsson, IMS, ITFC, Red Bee Media and SDI Media. These companies also produce multilingual subtitles and SDH. In fact, some companies switch subtitlers to AD duties when they have a tight AD deadline to meet. Some of them also provide sign language translation.

Live AD refers to the AD of live events. While the AD for such events is almost always delivered live, it is usually prepared in advance. Venues offering live AD may also be employing professionals, although payment is generally very low relative to the large amount of time it takes to prepare a live description. The process is set out in Chapter 6. In the UK, some production houses such as the National Theatre of Great Britain and the Royal Shakespeare Company use their own in-house teams; others buy in services from individual freelance describers or small, independent companies such as VocalEyes, Mind’s Eye and Sightlines. There is a very small market for script exchange between these companies. However, it is rare that another person’s AD script can be used with no changes. In addition to variation in writing and delivery style from one describer to another, the production might move to a different-sized venue, and a character reaching his position more quickly on a smaller stage leaves less time for description. In a larger venue, more may be said. Alternatively, a production might stay in the same theatre and be recast. One major dance sequence in the musical Billy Elliot, for example, is specifically choreographed around the dance skills of the particular boy playing the role of Billy, and hence may change quite radically from one child star to the next (Fryer, 2009).

Variation is not limited to recasting; three different boys may play Billy in a single week – not accounting for illness or injury. This is a particular issue with shows involving children, whose work, at least in the UK, is restricted by law. Similarly, although not legally regulated, opera singers may insist in their contract that they do not appear at every performance, in order not to strain their voice. While theatre describers in the UK are encouraged to write a script, they must also be prepared to improvise, for the reasons outlined here. In addition, some of the best actors are the most difficult to describe, as they like to keep each performance ‘fresh’ rather than replicate their gestures and expressions from one performance to the next. In screen AD a script will always be written, as, in addition to fixing the words, the script also provides the cues to trigger the recording process. This is explained further in Chapter 6.

There is no regulation of AD in live settings. However, UK legislation requires the broadcasting regulator (now Ofcom, formerly the Independent Television Commission (ITC)) to draw up and ‘from time to time review a code giving guidance as to how digital programme services should promote the understanding and enjoyment of programmes by sensory impaired people including those who are blind and partially-sighted . . . ’ (ITC, 2000). The original code (ibid.) was developed in the wake of AUDETEL, providing guidelines that have been the basis of AD practice for screen media in the UK and elsewhere ever since. According to Anna Jankowska ‘the guidelines or standards existing in many countries . . . are often established with reference to the personal experience of their creators or to similar guidelines used on foreign markets which are often derivative of other sources’ (Jankowska, 2015: 24). Gert Vercauteren (2007: 147) complains: ‘The current guidelines in Flanders, Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom are . . . little more than a starting point since they remain rather vague on some issues, whereas in other instances they lack structure and even miss some basic information.’ Since the year 2000, European scholars have been researching the grey areas and exposing flaws, false assumptions and cultural differences. The RNIB’s comparative survey (Rai et al., 2010: 6) concludes that: ‘Though, in principal [sic] the guidelines and/or standards studied in this paper are very similar in nature, there are minor differences in a few of the recommendations.’ The authors show that differences emerge in advice on naming characters; in the use of adjectives that are regarded by some as subjective; and in including mention of colour. However, it is important to note that the ITC Guidance (ITC, 2000) specifies that ‘these notes are presented in the form of guidelines only, with no absolute rules’. The advantage is that this should allow the art of AD to change and develop; the disadvantage is that it leaves areas of AD practice open to debate and to Vercauteren’s accusation of ‘vagueness’. This can be regarded as a positive rather than a failing. This book, refers to the results of reception studies to inform the advice given where it departs from the ITC Guidance. As stated, there are no official guidelines for the AD of live events, perhaps because there is no official body to police these descriptions; or perhaps because it is not clear whether the responsibility for provision of AD lies with the venue or the production company. Perhaps it is assumed that AD users will ‘vote with their feet’, choosing not to attend theatres that provide what they regard as description of poor quality. The author believes that, because of the lack of guidelines, AD in theatre is often more adventurous and less hidebound than screen AD. This is one reason why many examples of live AD are included to illustrate points in the chapters that follow.

This chapter has outlined the development of AD, expanding from its earliest origins in the UK to its recent emergence in China and elsewhere. It has pointed out the important role played by pioneers in America such as the Pfanstiehls and Gregory Frazier. It has stressed differences in the process of AD for screen and for live events. The situation is fluid, owing to new ways of accessing AV media. Although legislation has often been crucial for the development of AD, the practice is unregulated in many contexts, leaving the specifics open to evolution and debate.

2.8 Exercises and points for discussion

1 Does audio description happen in your country? Is there a legal framework or guidelines governing the provision of AD where you live? If so, find out what they say.

2 Should AD be regulated? Discuss the advantages and limitations.

3 In what way does AVT differ from any other form of translation?

21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act, 2010. Retrieved from https://www.fcc.gov/guides/21st-century-communications-and-video-accessibility-act-2010 [accessed 24.08.15].

Audio Description Association (ADA) (2014). ‘Commemorating the Great War’. Notepad (December), 107–112.

Audiovisual Media Directive 2007/65/EC. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/archives/information_society/avpolicy/reg/tvwf/access/index_en.htm [accessed 9.08.15].

Blind Citizens Australia (2015). Press release retrieved from https://wordpress.bca.org.au/media-release-audio-description-abc-sued-for-unlawful-discrimination/ [accessed 11.08.15].

Communications Act (2003). Retrieved from www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/21/pdfs/ukpga_20030021_en.pdf [accessed 24.08.15].

Díaz Cintas, Jorge, Pilar Orero and Aline Remael (2007). Media for all: subtitling for the deaf, audio description, and sign language. Approaches to Translation Studies, vol. 30. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Disability Discrimination Act (2005). Retrieved from www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/13/contents [accessed 24.08.15].

Fryer, L. (2009). Talking dance: the audio describer’s guide to dance in theatre. Apt Description Series, 3. ADA Publications, ISBN 978-0-9560306-2-7.

ITC (2000). ITC guidance on standards for audio description. Retrieved from www.ofcom.org.uk/static/archive/itc/itc_publications/codes_guidance/audio_description/index.asp.html [accessed 22.12.15].

Jankowska, Anna (2015). Translating audio description scripts: translation as a new strategy of creating audio description, trans. Anna Mrzyglodzka and Anna Chociej. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Leung, D. (2015). ‘Audio description in Hong Kong: gauging the needs of the audience’. Paper presented at the Advanced Research Seminar in Audio Description (ARSAD) 2015, Barcelona (March).

Lodge, N. K. (1993). ‘The European AUDETEL project – enhancing television for visually impaired people’. In IEE Colloquium on Information Access for People with Disability, London: IEEE, pp. 7/1–7/7. Retrieved from http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=160418 [accessed 7.01.2016].

Marcus, Laura. (2007). The tenth muse: writing about cinema in the modernist period. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mazur, Iwona and Agnieszka Chmiel (2012). ‘Audio description made to measure: reflections on interpretation in AD based on the Pear Tree Project data’. In Aline Remael, Orero Pilar and Mary Carroll (eds) Audiovisual translation and media accessibility at the crossroads. Media for All 3. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, p. 173.

Nikul, Chris (2015). ‘Access on demand: captioning and audio description on video on demand services’. In Media Access Australia report series, available from www.mediaaccess.org.au/latest_news/international-policy-and-legislation/video-on-demand-access-builds-up.

Pfanstiehl, Margaret and Cody Pfanstiehl (1985). ‘The play’s the thing – audio description in the theatre’. British Journal of Visual Impairment 3, no. 3: 91–92.

Rai, Sonali, Joan Greening and Leen Petré (2010). ‘A comparative study of audio description guidelines prevalent in different countries’. London: RNIB, Media and Culture Department.

RNIB (2015). Retrieved from www.rnib.org.uk/audio-description-app [accessed 24.08.15].

Sky (2015). Accessibility page. Retrieved from http://accessibility.sky.com/faqs/why-not-audio-describe-all-sky-programmes [accessed 25.08.15].

Snyder, Joel and Simon Padro (2015). ‘Audio description and the Smartphone: AD access in the future’. Paper presented at Advanced Research Seminar on Audio Description (ARSAD) 2015, Barcelona (March).

Vercauteren, Gert (2007). ‘Towards a European guideline for audio description’. In J. Díaz Cintas, P. Orero and A. Remael (eds) Media for all: subtitling for the deaf, audio description and sign language. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 139–150.

Washburn, Dennis and Carole Cavanaugh (2001). Word and image in Japanese cinema. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wright, Tracy (2015). Netflix blog. Retrieved from http://blog.netflix.com/2015/04/netflix-begins-audio-description-for.html [accessed 24.08.15].

References to live performances

Billy Elliot, dir. S. Daldry (2005–2016), Victoria Palace Theatre, London.

The Lion King, dir. J. Taymor (2000–ongoing), Lyceum Theatre, London.