The cure for this ill is not to sit still.

Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936)

The osteopathic techniques that I have developed to treat CFS/ME patients are based on standard procedures used by trained osteopathic practitioners.1,2 The manual treatment of each CFS/ME patient consists of a number of stages. I will describe these in some technical detail now before setting out recommendations for self-care. In particular I use a lot of anatomical terms which are necessary for precision. Non-practitioners may wish to turn immediately to ‘Self-help advice’ on page 103, but interested general readers can find the anatomical terms explained in a number of excellent books including Principles of Anatomy and Physiology: the Maintenance and Continuity of the Human Body by G. Totora et al (publisher, John Wiley & Sons Inc).

Stages of treatment

- Effleurage (massage) to aid drainage in thoracic and cervical lymphatic vessels.

- Gentle articulation of thoracic and upper lumbar spine, and the ribs. This is achieved by both long and short lever techniques.

- Soft tissue massage of certain muscles: the paravertebral muscles, the trapezii, levator scapulae, rhomboids and muscles of respiration.

- High and low velocity manipulation of the thoracic and upper lumbar spinal segments using supine (back-lying) and side-lying combined leverage and thrust techniques.

- Functional techniques to the suboccipital region and the sacrum.

- Stimulation of the cranio-sacral rhythm by functional cranial techniques.

- Exercises are prescribed to improve the quality of thoracic spine mobility and the coordination of the patient.

The stages of treatment, as shown above, form the protocol followed throughout the clinical trials in the years 1996–7 and 2000–2001. It altered slightly, depending on the physical state of the patient and on the symptom picture at that particular stage in their therapy.

Effleurage to aid drainage in thoracic and cervical lymphatic vessels

Congested lymph and oedematous changes (swelling) are relieved by ‘effleurage’, a method of massage that requires stroking motions along the surface of the trunk and the neck.

The gentle strokes are carried out rhythmically towards the subclavian region, superficial to the subclavian veins, which drain all the lymph fluid into the blood stream. Effleurage stimulates the lymphatic drainage through direct routes into the thoracic duct and hence into the venous return (see Fig. 16. page 94). Care is taken to avoid stimulating drainage into the axillary lymph nodes, which are prone to swelling and congestion in CFS/ME sufferers. It is hypothesised that the more direct route forces a high pressure within the smaller parasternal vessels, which creates enough force within the thoracic duct to alleviate the back-pressure and restore a healthy drainage of toxins into the venous return.

With female patients effleurage to the breast tissue is carried out in the presence of a chaperone, after explaining the exact nature of the treatment, and using consent forms usually supplied by the practitioner’s governing body. The gentle stroking is applied upwards covering the entire breast tissue towards the clavicle (collar bone).

The effleurage technique is used on the lymphatic vessels of the neck, head and back, stroking downwards along the back and sides of the neck and head and upwards along each side of the thoracic spine. Each stroking motion finishes at the level of the subclavian vein, creating the pressure required to restore a healthy drainage of toxins.

Figure 16. Effleurage down neck and up chest to clavicle.

The arrows show the direction of the massage technique, which is always towards either clavicle (collarbone) on both sides. This is the region above the drainage of lymphatic fluid from the right lymphatic duct and the thoracic duct into the right and left subclavian veins respectively.

Gentle articulation of thoracic and upper lumbar spine and the ribs

The main objective of the articulatory, soft tissue techniques and high velocity manipulation (stages 2, 3 and 4) is to improve the structure and overall quality of movement of the dorsal and upper lumbar spine.

The two sympathetic trunks are integrally related to the overall structure of the area. By reducing mechanical irritation at this region, as well as relaxing disturbed afferent impulses, the dysfunction of the sympathetic nervous system can be corrected.

In cases of hypermobility, which is rarely found in the patient’s thoracic spine, mobility of the adjoining areas of the spine is improved by articulation and manipulation. This takes the strain off the hypermobile segments. What is predominantly found in patients with CFS/ME is a restricted dorsal spine. Frequently, the entire thoracic region is stiff, and occasionally just a few segments are affected.

Treatment to increase mobility of the spine can take many forms. The general articulatory manoeuvres employed are short lever mobilisation, using gentle pressure on the pars articularis and spinal processes, together with long lever rhythmic stretching of the dorsal and lumbar spinal segments, using the arms and legs for the appropriate leverage. All the articulatory techniques are slowly and gently applied with minimal force in order to avoid irritating spinal inflammation and to reduce any reactive spasm from the surrounding muscles.

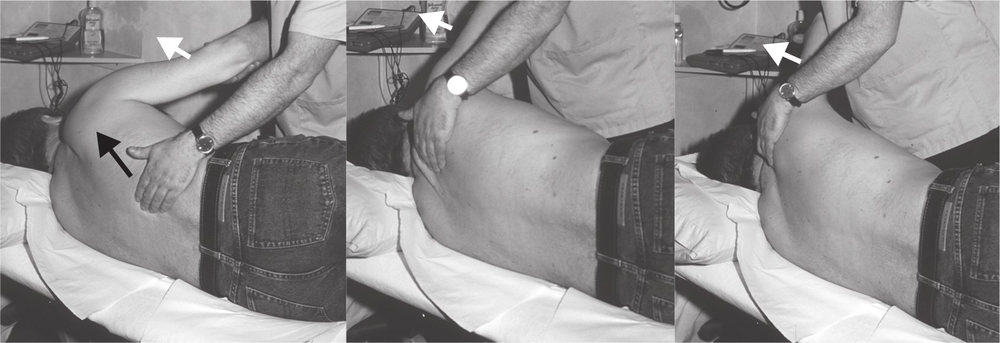

This method is usually carried out with the patient lying on his or her side to allow a gentle stretch of periscapular and paravertebral muscles together with gentle massage upwards along the spine to improve lymphatic flow. This is often combined with a gentle stretch of the ribs, which is performed by holding the patient’s arm with one hand, fixing the ribs with the other hand, and gently moving the held arm upwards, stretching the thorax above the fixed rib. Combined stretch and massage, using the patient’s arm as a long-lever, produces excellent results, with movement of the ribs increased by articulatory stretch techniques (see Fig. 17).

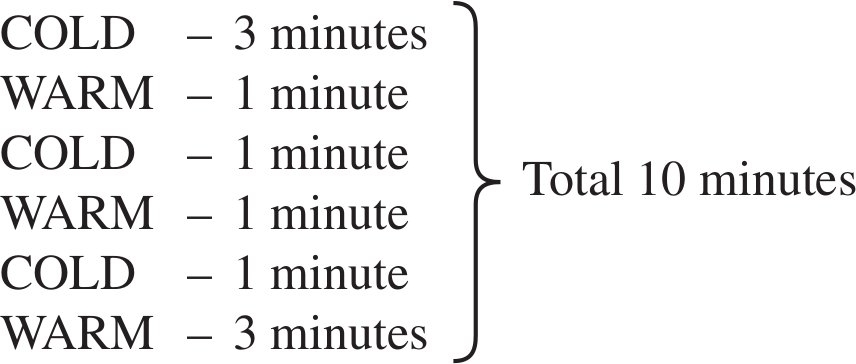

To remedy the problems caused by hypermobile joints, as with restricted joints, the first task is to reduce any possible inflammation present at the damaged segments. This can be achieved in various ways. Some practitioners would prescribe anti-inflammatory drugs. However, contrast (hot alternating with cold) bathing is deemed preferable, as it has no toxic side effects. The hot compress usually consists of a warm (not hot) water bottle. Too hot a compress could scald the patient’s skin. The ‘cold’ is as cold as the patient can tolerate; it is safer if a frozen pack is wrapped with a cover, especially as CFS/ME patients often cannot tolerate extremes of temperature. Frozen peas, which easily mould around the back, can be used, although special cold compress packs, which remain soft even when frozen, are more suitable.

My clinical experience has shown that the sequence of contrast bathing that gives the best results in reducing the inflammation in CFS/ME is as follows:

This process has no adverse side-effects, and so it is safe to use as many times as required. Applications of at least three times a day to the upper thoracic region is recommended if there is inflammation in the neck and shoulders (or there are cerebral symptoms such as cognitive difficulties) and the lower thoracic area when the abdominal or lower extremities are affected. The main advantage of contrast bathing over anti-inflammatory drugs is that it works quickly and directly on the affected area. Even when there is no palpable or visible inflammation, shown by heat and redness, contrast bathing to improve circulation in the thoracic region is still advised.

Soft tissue massage of the paravertebral muscles, trapezii, levator scapulae, rhomboids and muscles of respiration

Generally, the massage technique for the relaxation of the above mentioned muscle groups takes the form of gentle longitudinal and cross-fibre stretching. Almond oil is recommended as it is the most common base oil used in massage and seems in most cases to be hypoallergenic.

With the patient lying on his or her side, paravertebral muscles, primarily the dorsal erector spinae, are manually stretched using direct longitudinal pressure up to a level parallel with the first thoracic vertebra. Combined with long lever stretching, via movement of the patient’s arm and shoulder joint, this method has the added advantage of increasing rib movement and stimulating deep lymphatic drainage from the spine (see Fig. 17).

I try to avoid having the patient lie in a prone (on his or her front) position. However, if the practitioner finds it necessary for the patient to lie prone, his or her face should be placed into a breathing hole in the practice bed to avoid unnecessary strain on the neck. The patient should be moved on to the side as soon as possible to carry out the paravertebral soft tissue work in this healthier position, while keeping the head level and knees apart with the aid of pillows.

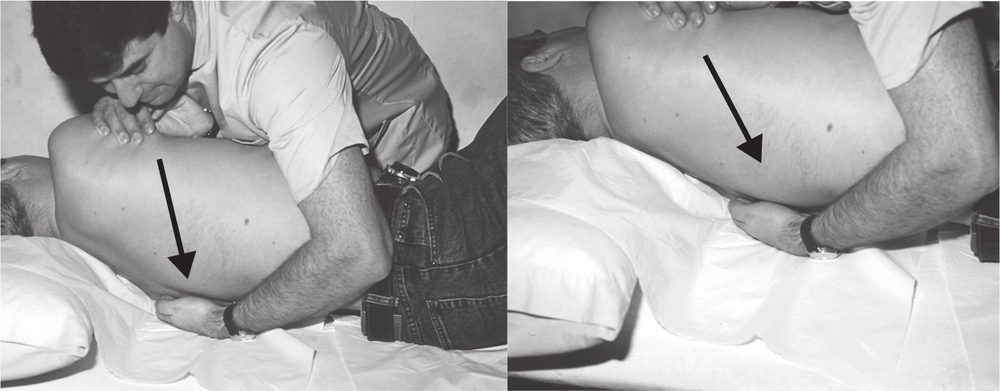

Treatment is given to relax the trapezii (see Fig. 18) and periscapular muscles, for example, the rhomboids, as well as any other hypertonic back and shoulder muscles. Besides stretching, occasionally inhibition or functional techniques are used to reduce the tone of the tightened musculature (see Fig. 22).

After increasing movement of the restricted spine and relaxing the surrounding musculature, I attempt to improve the respiratory mechanics. This is important in CFS/ME patients, since the amount of oxygen in the body affects its chemical content, and has a direct effect on the functioning of the body’s tissues. Reduced oxygen produces greater fatigue in the patient and will aggravate the symptoms. By improving the mechanics of respiration in the rib cage, the patient’s lung capacity is increased during inspiration, thus raising the patient’s oxygen intake. Although increasing spinal mobility and relaxing paravertebral muscles will enhance movement of the ribs, the specific respiratory muscles should also be treated in order to improve the respiratory mechanics. These include the intercostal muscles, serratus anterior and posterior, pectorals, abdominals and, most importantly, the diaphragm. Gentle inhibition to the edge of the diaphragm dome will usually reduce the tone of the muscle and aid breathing. This technique is known as ‘diaphragmatic release’.

Figure 17. Combined articulation, soft tissue stretch and paraspinal effleurage.

This method is a combination of three soft tissue techniques: long lever stretch of the intercostals, using the patient’s arm as a lever; direct longitudinal stretch of the dorsal erector spinae with the fingertips; and effleurage to the paravertebral lymphatics. The black arrow illustrates the direction of the massage and the white arrows show the direction of movement of the patient’s arm.

Figure 18. Cross fibre stretching of lower neck and shoulders.

This technique involves a slow rhythmic kneading action applied across the fibres of the lower cervical erector spinae, trapezii and levator scapulae.

After increasing mobility of the thorax by articulation and stretching, as well as relaxing the musculature, the patient is usually feeling more comfortable and can lie in a supine position with knees slightly bent in readiness for the next stage of therapy.

High velocity-low amplitude manipulation

If any of the joints are severely immobile, it may prove necessary to increase movement by high velocity low amplitude thrust techniques (see Figs 19, 20 and 21). In osteopathy, this technique is called High Velocity-Low Amplitude (HVLA) or simply the high velocity thrust (HVT). In chiropractic, this manoeuvre is called an ‘adjustment’ and is commonly known as a manipulation. It is the best known technique in the osteopath’s armoury and involves a short, sharp motion usually applied to the spine. This procedure is designed to release structures with a restricted range of movement. There are various methods of delivering a high velocity thrust. Chiropractors are more likely to push on vertebrae with their hands, whereas osteopaths tend to use the limbs to make levered thrusts. That said, osteopathic and chiropractic techniques are converging, and much of their therapeutic repertoire is shared. This technique may produce a ‘cracking’ sound.

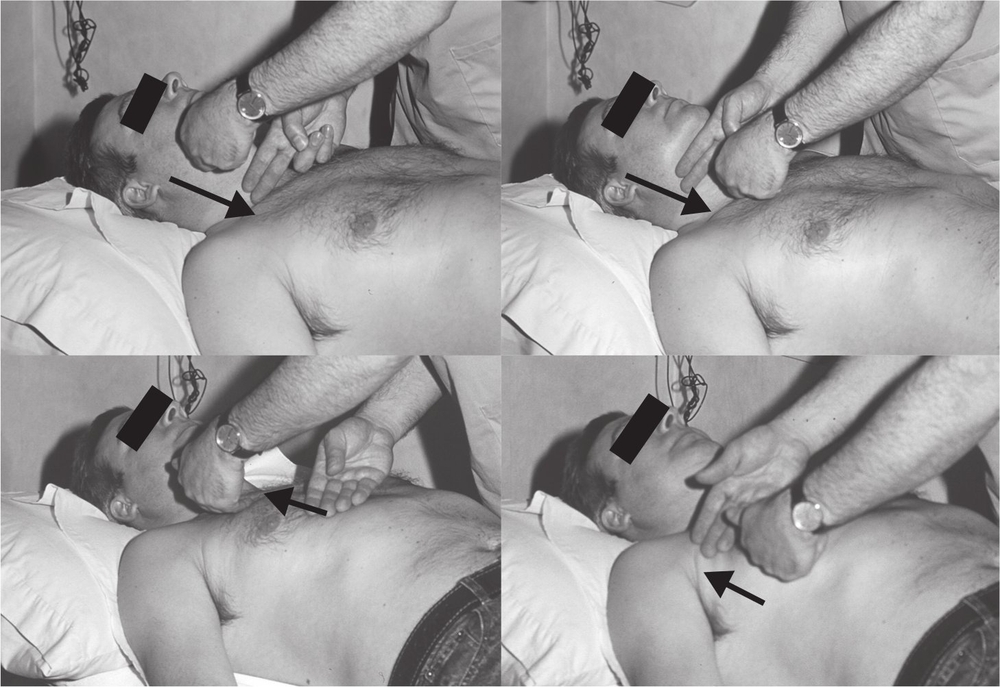

Figure 19. Combined leverage and thrust of mid-thoracic vertebrae.

My left hand is positioned in a loose fist around the spinous process of the vertebra. As pressure is exerted from my right hand, through the patient’s body, the facet joints at the side of the adjacent vertebrae will open to gap the facet joints. When the tension has built up by positioning the patient’s upper spine in a flexed and rotated position, a fast but gentle pressure is applied through the direction of force as illustrated by the arrow which further gaps the joint and brings about a long-lasting increase in mobility.

Figure 20. Combined leverage and thrust on the upper lumbar spine.

The upper lumbar vertebrae are gently rotated, creating a tension at a restricted joint. By applying a further quick thrust with my hands across the joint, it opens and creates more overall movement.

Figure 21. Gentle combined leverage and thrust on the lower cervical spine.

This manipulative procedure involves bending the patient’s neck to the left while rotating the cervical spine towards his right. Gentle pressure is placed towards the direction of the arrow, gapping the joints at the side of the restricted vertebrae and creating more movement.

The HVTs can be achieved with the patient lying prone, but it is preferable and safer to turn the patient on to their back and manipulate them in a supine position. Vertebral joints in some patients may appear slightly fused and therefore strong manipulation should be avoided in order to prevent any damage to the bone.

The sequence, strength and duration of all the above techniques are based on each individual case, but care is taken not to over-manipulate, especially in the lower cervical region, as this can exacerbate the symptoms.

Functional techniques to the suboccipital region and the sacrum

It is important when one treats posturo-mechanical strain of the spine to balance the suboccipital and lumbosacral segments. Any abnormal curvature will alter muscular tone along the spinal column and thus place an extra load on the uppermost section and base of the spine. Similarly, positional alterations at the top and bottom of the spinal column will affect the overall mechanics of the entire spine. Osteopaths and chiropractors may use an effective procedure in these regions known as the functional technique (see Fig 22). If, during subtle movement of the spine, a restriction is detected, however slight, the back is held at the point of restriction until a release of muscle tension occurs. In practice, osteopaths rely on finely developed palpatory skills. The main principle of any osteopathic treatment is that structure governs function (see Chapter 9). The principle of the functional technique is that by placing a joint or a group of muscles in a certain position that is functionally suited for that particular bodily part, the result is a relaxation of tissues and an overall improvement in muscular and fascial tone in the region.

The suboccipital muscles and the pelvic and lower lumbar muscles can be relaxed efficiently and painlessly by gentle positioning of the occiput and sacrum respectively. With the patient lying supine, the osteopath’s hands are placed at each side, cradling the occiput, which is then lifted slightly off the pillow. The cervical spine is then gently extended and slowly rotated and bent towards the right. Traction or compression is applied and by asking the patient to breathe deeply, it is possible to utilise exhalation as a relaxation tool.

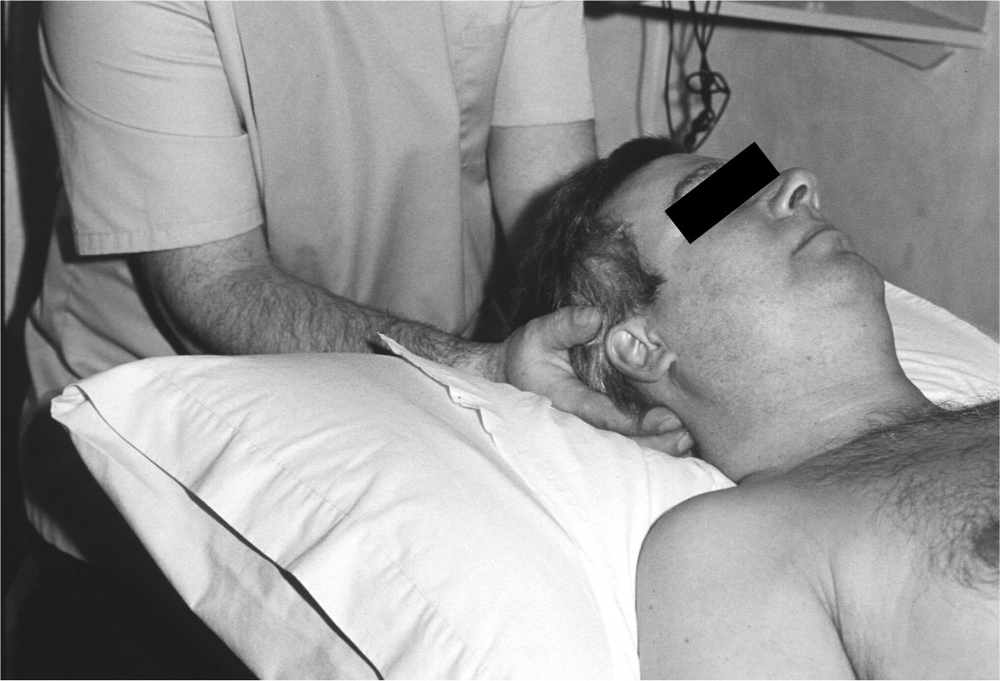

Figure 22. Functional technique to the suboccipital region.

With the patient lying supine, the osteopath’s hands are placed at each side, cradling the occiput, which is then slightly lifted off the pillow and held in a fixed position to produce comfort and relaxation of the tissues in the upper cervical region.

There is a fixed position where, by palpating the muscular tone just beneath the occiput, using the fingertips, one is able to feel the point of maximum relaxation for the suboccipital muscles. This position is held for a few seconds, resulting in a reduction of tone in this muscle group (see Fig 22).

The same technique is applied to the pelvic and lower lumbar region by cradling one hand under the patient’s sacrum and palpating the muscular tone in the lumbarsacral region.

Stimulation of the cranio-sacral rhythm

Stage six commences near the end of each consultation (see Fig 23). This useful technique is very effective at restoring energy and improving the cognitive ability of the patient.

The fluctuating slow wave previously identified by Sutherland,3,4 and described in Chapters 8 and 9, is known as the cranial rhythmic impulse (CRI). The CRI has a flexion (inspiration) phase and an extension (expiration) phase, faintly changing the shape of the ventricles. Similar to the thoracic duct pump exerting an influence upon the entire lymphatic system, the CRI can be palpated throughout the body.

Figure 23. Cranial treatment.

The osteopath’s hand is placed in two different positions, cradling the head laterally and antero-posteriorly. The cranial procedure involves very gentle pressure and minimal movements.

The main cranial technique that I use is similar to a procedure known as a CV4 (the compression of the fourth ventricle). This compression is achieved by gentle force applied with both hands, pressing medially at the lateral angles of the occiput.

It is my belief that by using this technique, the volume within the ventricular system is reduced, forcing the cerebrospinal fluid out; by this means, drainage through the cribriform plate and down the spine is enhanced. Accordingly, the technique plays an important part in overall treatment.

Care should be taken not to over-stimulate the cranial rhythm with too long or forceful a treatment. After resuming a seated position, the patient is advised to remain sitting for a moment and not to stand abruptly. This is aimed at reducing dizziness due to the neural mediated hypotension commonly found in CFS/ME (see Chapter 5).

This first section of Chapter 10 has touched upon the osteopathic techniques I use in the treatment of CFS/ME. Some of the excellent books written about the entire spectrum of osteopathic techniques are listed in the Further Reading section at the end of the book.

Self-help advice

Osteopathic treatment is not synonymous with manipulation. Many treatments of numerous conditions would be found to be insufficient if they relied on manual therapy alone.2 As in standard osteopathic practice, advice is given to patients to help improve their general health.

Dorsal rotation exercise

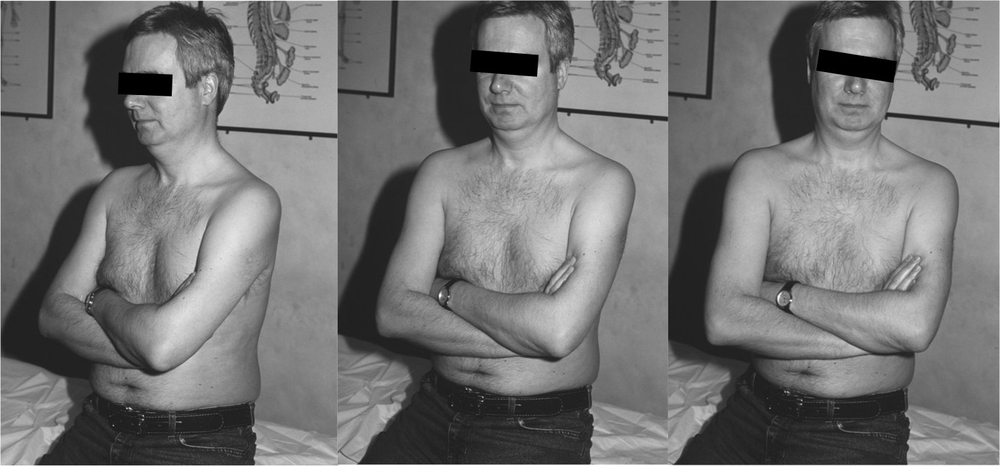

I have observed that manual treatment improves function of the thorax and the spine, especially when enhanced by routine mobility exercises. An effective exercise prescribed to improve and maintain the quality of movement of the dorsal spine is as follows (see Figs 24, 25 and 26):

1. The patient should be seated and place his/her hands around the side of the neck (see Fig 24). S/he should slowly rotate the trunk, together with the head and neck. This gentle rotation is designed not to stretch muscles and joints, but gradually and subtly to increase movement of the upper thoracic vertebrae. The arc of rotation should be only about 45 degrees in total from right to left. This should be repeated five times each way, without stopping in the middle. The movement must be rhythmic, with the patient feeling relaxed throughout the process.

2. The patient should cross his/her arms and hug his/her shoulders with his/her hands (see Fig 25). The movement to the right and left should be repeated five times each way as above, making sure that the head, neck and shoulders all move in unison. This part of the exercise encourages movement in the middle section of the thoracic spine.

3. With the patient remaining seated, the exercise should be repeated, once again five times each way, with the arms folded at the waist (see Fig 26). Rotating the trunk in this position improves mobility of the lower dorsal and upper lumbar segments of the spine.

Patients should carry out the entire sequence three times a day. Since it is a very gentle exercise, even severe CFS/ME should not prevent the patient from doing the exercise. However, the patient is advised to cease exercises if pain develops at any time during or following the routine. The complete routine in all three positions takes about one minute, when performed at the correct speed.

Figure 24. Upper thoracic rotation exercise.

The patient slowly rotates his upper back five times each way, through an arc of 45 degrees while sitting. When holding the side of his neck, the patient finds that this rotation gently stretches the upper thoracic spine.

Figure 25. Mid-thoracic rotation exercise.

The patient slowly rotates his back five times each way, through an arc of 45 degrees while sitting. When holding the shoulders, this rotation exercise gently stretches the mid-thoracic spine.

Figure 26. Lower thoracic rotation exercise.

The patient slowly rotates his back five times each way, through an arc of 45 degrees while sitting. When folding the arms, the patient finds that this rotation exercise gently stretches the lower thoracic spine.

Following the above exercise, the patient is advised to stand up, and gently shrug his/her shoulders, rolling them slowly forward five times and then slowly repeating with backward rolls five times. This exercise should be carried out at least three times a day (see Fig. 27).

Cross-crawl

One can stimulate both halves of the brain to work together in harmony with the whole body by the exercise known as cross-crawl. The cross-crawl exercise is marching on the spot. The marching action should be slow and deliberate, with the patient’s right arm moving in unison with the left leg. This action is repeated, moving the left arm forward together with the right leg. CFS/ME patients usually find this simple task difficult to perform at the beginning of therapy, since their bodies are so un-coordinated. It is very important not to move the arm and leg of the same side together, as this will succeed in throwing the body (and mind) further out of balance. After practising for a while, patients are able to carry out the cross-crawl exercise without much difficulty. The marching routine is to be done for up to five minutes in total in an entire day, a minute or so at a time. Any exercises that overexert the patient are to be avoided.

Figure 27. Shoulder shrug exercise.

While standing, the patient gently shrugs his shoulders, rolling them slowly forward five times and then slowly repeating with backward rolls five times.

Self-massage routine

The patient is advised to aid the lymphatic drainage of the head and spine through a self-massage routine.

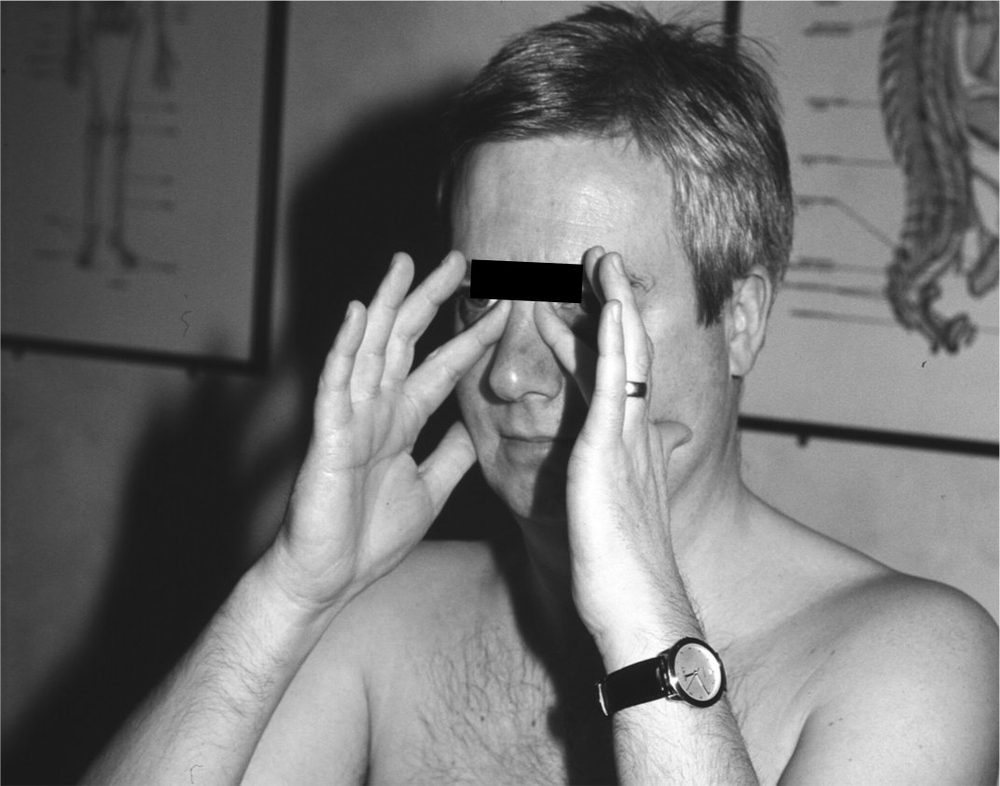

Nasal release

This massage schedule begins with the patient, seated, applying gentle pressure to open the junction between the forehead and nose and aid drainage into the mucous membrane of the nasal sinuses. The minimal force required is accomplished by mildly pressing the pads of both second fingers up against the inner canthus (inside corner of the eye) or conversely, pulling slightly down just above the bridge of the nose. The patient should choose the technique with which s/he feels most comfortable and which enables him/her to breathe easily through the nose. During the first ten days of self-treatment, the pressure with the fingers should be held for a seven-minute period. This has been shown to bring about a lasting release of the region by enhancing breathing and lymphatic drainage. After the first ten days, patients should continue with nasal release for a one-minute period each day in order to maintain the improvement (see Fig. 28).

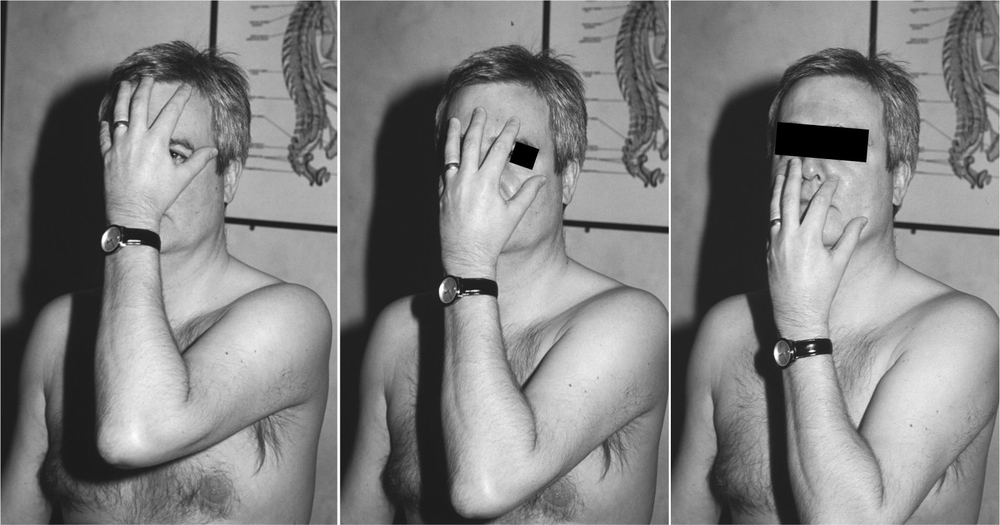

Facial massage

The patient, while remaining seated, should gently stroke the fingertips of one spread hand down his/her faces to the chin (see Fig. 29). This gentle facial effleurage should be carried out for twenty seconds with a rate of one stroke roughly every four seconds.

Head massage

The above gentle stroking method should be repeated for twenty seconds at a time on both sides and the back of the head down to the neck (see Fig. 30).

Figure 28. Nasal release.

The seated patient gently presses the pads of both second digits up against the inner canthus (inside corner of the eye) or conversely, pulls slightly down just above the bridge of the nose.

Figure 29. Facial self massage.

The patient gently strokes the fingertips of one spread hand down his face to the chin for twenty seconds.

Anterior neck massage

The patient should lie down and, using almond oil or baby oil, continue with bilateral effleurage of the neck down to the clavicles (shoulder blades) for twenty seconds each side (see Fig. 31)

Breast massage

The patient massages the lateral, central and medial sections of the breast in turn for twenty seconds, with a slow rhythmic stroking manoeuvre up towards the clavicles, thus directing the lymph away from the axillary (in the arm pits) lymph nodes to avoid risk of glandular swelling (see Fig. 32).

Back massage

Having adopted a prone position, the patient receives back massage from a family member or friend. The massage routine consists of one minute of gentle upward effleurage to the sides of the spine, finishing in the shoulder region at a level with the clavicles. If no help is available from another individual, patients should use back brushes to accomplish the back massage.

Figure 30. Self massage to head.

The patient gently strokes the fingers of both spread hands down the sides of his head to the neck for twenty seconds.

Figure 31. Anterior neck self massage.

The arrows show the direction of the self-massage technique, which is always towards each clavicle, on both sides for twenty seconds. The pressure applied by the patient should be much less than during a treatment session, concentrating only on the superficial lymphatics in the self-massage.

Figure 32. Self massage of the breast.

The arrows show the direction of the self-massage technique. The patient massages the lateral, central and medial sections of each breast in turn for twenty seconds, with a slow rhythmic stroking manoeuvre up towards the clavicles. The pressure applied by the patient should be much less than during a treatment session, concentrating only on the superficial lymphatics in the self massage.

Posterior neck massage

The self-massage routine should be completed with downward effleurage of the back of the neck for twenty seconds on both sides, just in case the upward back massage is too vigorous and upward pressure is applied too high above the clavicles.

Returning to good health

Patients are advised to avoid any stress whether physical, mental or emotional whenever possible. Activities that exert strain on the body are to be avoided. If the patient’s occupation involves too much physical activity, they are advised to stop work temporarily or reduce their workload. This especially applies to tasks that put extra mechanical strain on the thoracic spine.

Physical tasks that exert too much strain on the patient are, if possible, to be done by a helpful colleague. Members of the patient’s family are advised to share the workload at home, to make life as bearable as possible, until treatment has restored the sufferer to better health.

If the patient usually spends time in front of a computer or if they are desk-bound at work, they are advised to stand up every half-hour for a minute or two, and walk around the office. They should also take a fifteen-minute break every two hours.

The patient is instructed to avoid slumping into a soft chair. When relaxing, patients are advised to lie on their side on a couch or a bed with their head well supported and a pillow between their knees. Lying on the side puts minimal strain on the spine.

Patients are advised to vary their diet as much as possible. This reduces the possibility of placing strain on any particular region of the gastrointestinal system. Processed foods are to be avoided and wholemeal flour and brown sugar should replace the white variety. Stimulants such as caffeine are to be avoided particularly in CFS/ME. Decaffeinated coffee and decaffeinated tea or herbal tea can be drunk instead, but, because decaffeinated coffee has been shown to increase cholesterol levels, this should be taken only in moderation.

Patients should eat regular, healthy meals and drink plenty of healthy fluids, preferably mineral or filtered water – 2 litres a day should be enough. The intake of tobacco, alcohol and too much medication may exert a strain on the gut, and thus the sympathetic nervous system. This will undoubtedly make the symptoms of CFS/ME worse. Smoking, drinking alcohol and the taking of medication should be kept to a minimum, and avoided completely if possible.

As well as a healthy diet, I prescribe a supplement of vitamins C and B complex. The former increases the patient’s resistance to infection, while B complex improves general functioning of the nervous system. A high dose vitamin C pill of 1000 mg is recommended three times a week and a strong, or whole B complex tablet once a day. Vitamins B and C are both water-soluble so that any excess is excreted from the body and cannot be stored. However, as there is a risk of developing kidney stones if the vitamin C intake is too high or if the patient suffers from kidney disease, it is wise not to take the 1000 mg pill every day.

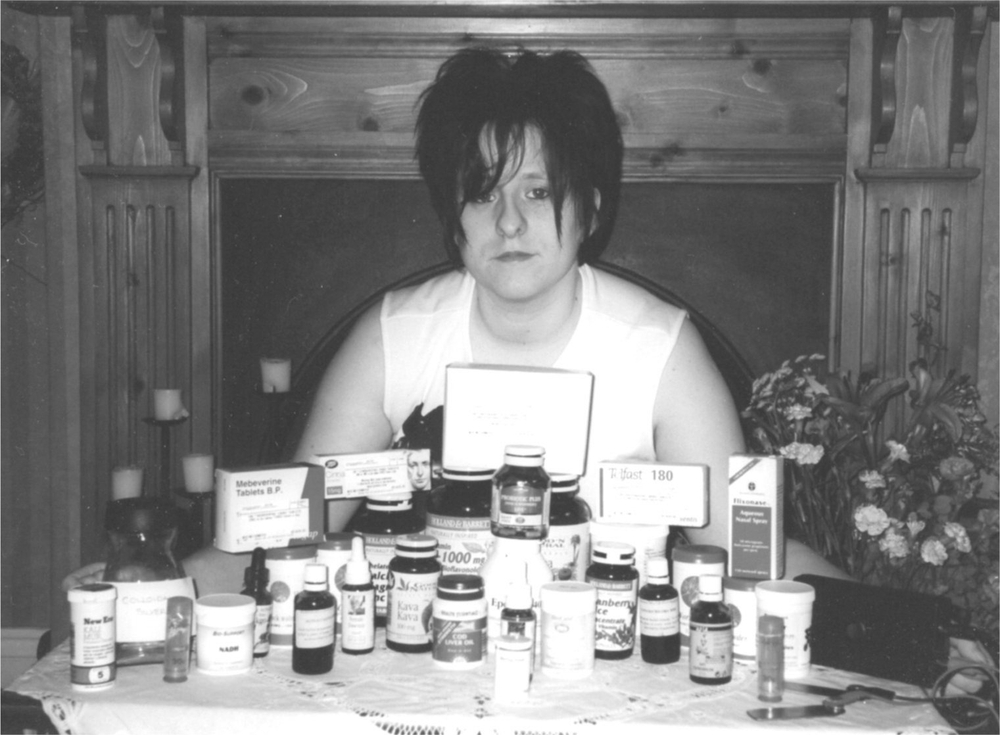

Beware of taking so many different supplements that any possible benefit is likely to be outweighed by undesirable side-effects (see Fig. 33), EPA and virgin evening primrose oil excepted.

Even though excessive supplements are harmful, occasionally they may be needed. If a patient develops a cold or flu, it is a sign that the immune system is starting to work properly. In the early stages of CFS/ME there is an upward regulation of the immune response, so, while a patient with CFS/ME rarely experiences colds or flu, they just feel constantly ill. Eventually, as the system balances, there is more and more chance of developing colds and other upper respiratory tract infections.

For colds and flu

I recommend a combination of Echinacea – a good natural immune system stimulant, one of nature’s natural antibiotics – bee propolis, and the most effective and probably the most hideous tasting supplement, grapefruit seed extract, known as citracidal.

Figure 33. A CFS/ME patient and her daily medication.

Flu jabs are at the patient’s discretion. Some vaccines, including the flu vaccine, contain mercury so you should be wary, but some patients’ immune systems are very poor. These tend to be the very severe long-term sufferers who struggle to respond to treatment. Immunisation in these cases may be the only option.

Sleep can sometimes be helped by having an extra small meal an hour before going to bed. As the hypothalamus controls sleep as well as satiety and hunger, this sometimes tricks it into switching on the sleep centres. Self-hypnosis also can often help the patient switch off and relieve sleep problems.

Frequency of treatment

At the beginning of treatment it is important that the patient is treated once a week and that the treatment remains regular and weekly. This usually continues for the first 12 weeks and, slowly, as symptoms improve, there is a gradual increase in the time between consultations. With severe cases, weekly treatments may be necessary for much longer than three months. Eventually, when patients remain symptom-free between their six monthly check-ups and are able to perform all reasonable activities with no after-effects, I will score them 10 out of 10 and they are pronounced cured. While acknowledging that every patient is different, I have devised a chart (see Table 2, page 114) that is a guide to both the patient and practitioner predicting the likely length of treatment.

This is a sliding scale and should be used as a general guide only, as there may be other factors to take into account. In other words, if at the start of treatment a patient is scored 5/10 on CFS/ME, but is also suffering from another disorder, the overall score may be 4/10 or lower. If the physical findings during the examination are very pronounced, the overall score is lowered. I often find that the patient is trying to appear healthier than s/he really is. This fits the profile of most CFS/ME sufferers who try as hard as they can to keep going until, eventually, they have to admit they cannot carry on or they just collapse.

The body cannot lie and, after physically examining the patient together with taking a detailed history, the trained practitioner should be able to give a reasonably accurate score that informs the patient how long the treatment programme may take. As the treatment progresses and the symptoms improve, a periodic reassessment of the score, based on the symptoms and physical signs, is useful.

It is a wonderful feeling for both sufferer and practitioner when a patient’s score is 10/10. This means that, without any treatment in the previous six months, the patient is and has been totally symptom-free, and, in addition, has been able to do everything s/he could do before s/he was ill, within reason, without suffering any side effects. The patient is then discharged.

Annual check-up

Whether the treatment proves to be a lasting cure or just remission depends on many factors that will affect the patient after being discharged. If the patient habitually overstrains their body, s/he may experience the return of symptoms. The patient should seek treatment as soon as the symptoms reappear in order to avoid a long-lasting relapse. The predisposition to developing CFS/ME takes the form of a disturbed drainage system and consequently, the patient should continue the dorsal rotation exercises for life after being discharged, and occasionally, maybe once a week, do the self-massage routine in the shower. Annual check-ups are a good idea, although I appreciate that some patients prefer to put the whole episode behind them.

Table 2 The outlook

| Score | Description | Prognosis |

| 1 | Extreme symptoms and signs for more than a year. Totally bed-ridden or sitting all day, little cranial flow palpable. | 3 years + |

| 2 | Severe symptoms and signs for more than a year. Bed-ridden or sitting all day, little cranial flow palpable. | 2 years+ |

| 3 | Severe symptoms and signs for more than a year, resting most of the day, little cranial flow palpable. | 2 years |

| 4 | Severe symptoms and signs for 6–12 months, resting most of the day, little cranial flow palpable. | 18 months+ |

| 5 | Severe symptoms and signs for at least 6 months; able to carry out light tasks but requires regular rest periods. | 12–18 months |

| 6 | Moderate symptoms and signs for at least 6 months; able to work part-time with a struggle. | 8–12 months |

| 7 | Moderate symptoms and signs for at least 6 months; able to work full time with difficulty. | 8 months |

| 8 | Moderate symptoms and signs for at least 6 months; daily life slightly limited. Symptoms worsen on activity. | 6 months |

| 9 | No symptoms but still signs of slight lymphatic engorgement and experiences mild symptoms following over-exertion | 3 months |

| 10 | Symptom-free for at least 6 months. Able to live a full active life …within reason. | Discharged |

Toxins in the brain don’t cause pain

One indication that the Perrin Technique is not a placebo is the fact that most patients feel a great deal worse at the beginning of their treatment. Placebo treatments do not, generally, make you feel worse. The reason for this initial exacerbation in the symptoms is due to the fact that, for the first time, the toxins embedded (possibly for years) in the central nervous system are being released into the rest of the body.

The most common symptoms in the early stages are nausea, headaches and general pain. These complaints can be easily explained. Nausea is caused, usually, by the liver having to cope with the extra toxins, which are draining via the lymphatic drainage into the blood. This is why I advise patients to take milk thistle extract (silymarin) and plenty of drinking water, as they are useful in helping the liver cope with the increased level of toxins. If you cannot tolerate milk thistle, try ginger. Those patients who cannot cope with any supplements should drink plenty of water and follow as healthy and balanced a diet as possible.

If patients have a dental appointment, they should remember the instructions given in Chapter 7 (see page 66), regarding type of filling and anaesthetic.

Headaches and pain may also be due to excess toxicity. As the treatment encourages the toxins to leave the brain, the toxins will initially affect the superficial tissues in the head and, as they drain down to the rest of the body, pain may follow. The toxins inside the brain do not cause pain as there are no pain receptors within the brain. However, toxins do affect the function of the brain, and this accounts for most of the symptoms of CFS/ME.

The first few weeks, or sometimes months in severe cases, are always the most trying for the patients. The worse the patient is in the early stages of treatment, the better, usually, it bodes for their prognosis.

While the body’s drainage system is improving with the treatment, another unpleasant sign is the appearance of spots, boils and other skin eruptions. Until the lymphatic channels are working properly, the toxins have to go somewhere and the quickest way out of the body is often through the skin. These skin problems normally clear up as the treatment progresses.

The main aspects for CFS/ME sufferers to focus upon are the changes occurring with the treatment. (If change has not occurred in any way during the first twelve weeks of treatment, the patient may have to take an alternative route in their search for a cure.) My treatment often hugely improves the patient’s health, but some may need other treatments in tandem in order to alleviate all symptoms. I have noticed that other treatments – whether they are dietetically or pharmacologically based – work better after the patient’s neurolymphatic pathways have been improved. Patients who have tried supplements before treatment to no avail, are advised to try some of the supplements again after undergoing the Perrin Technique, as they may now prove more effective.

Remember that there are other conditions that can commonly occur together with CFS/ME that may require an additional or slightly different approach. For example, fibromyalgia is often seen in CFS/ME patients. This condition, which features painful muscles, can be detected by palpating 18 known trigger points throughout the body. If at least 11 of the 18 are tender, fibromyalgia is diagnosed. There are many books on the subject with illustrations of the trigger points. Because the massage used in my treatment plan may aggravate the pain in fibromyalgia, the massage should be kept to the minimum in these cases. The painful joints should be gently stretched with plenty of cold compresses laid only on the spine (cold, not frozen, ice pops placed longitudinally are useful for this) and warm compresses placed on the surrounding paravertebral muscles.

CFS/ME in children

There are thousands of childhood cases of CFS/ME a year recorded in the UK. However, you rarely see children younger than five with the condition,5 due to the fact that CFS/ME (1) takes time to develop and (2) is linked to postural problems in the spine, affecting the body’s drainage of toxins. A child starts to walk at about one year and it takes a few years to develop a painful, bad posture. A major spinal trauma may precipitate the onset of CFS/ME in the very young, but this is extremely rare.

It is difficult to persuade children to reduce their level of activity when they want to do so much. It is hard to help the parents maintain a positive attitude when, initially, they may see their child becoming more ill. However, some patients do improve immediately, for patients do not necessarily get worse before starting to recover. One patient improved so quickly that within weeks he was able to take up football and tennis; I think it was lucky that I treated him at just the right time for the body quickly and safely to return to normal. However, most patients are not that fortunate and may suffer to begin with during treatment. Often the parent looks at me, thinking, perhaps, ‘What are you doing to my child?’

I have a great deal of sympathy with the parents of any sick child. CFS/ME affects the whole family, so I often try to have as many members of the family as possible at the consultation so that they can understand what is going on.

Our son, Max

I empathise with parents who see their lovely child go from a healthy, active boy or girl to a wheelchair-bound invalid. When my son, Max, was only five, he started exhibiting signs and symptoms of fatigue. My wife and I began to be concerned when he complained of constant headaches. We became very worried when he started projectile vomiting every morning and so we took him to our GP who referred him to the hospital. There he was examined by a paediatrician and a trainee doctor who refused to scan his brain, saying that it was a virus. I told them that I had spent years studying the brain and that his signs bore the hallmarks of increased intracranial pressure. He had banged his head a week before and I was concerned that this was the reason. They took a chest X-ray, but refused a scan and sent us home. Another two trips to the doctor’s and we were again told that it was a virus. One doctor said remarkably to me that Max, who by then had to be carried into the surgery, was suffering from ‘sibling rivalry’: his little brother was born the year that Max fell ill, so, maintained the doctor, he was seeking attention.

A week later he was undergoing surgery to remove a pylocytic astrocytoma from his cerebellum or, to put it into lay terms, a tumour from the back of his brain. The pressure caused by the tumour had damaged the ventricular system in the brain, affecting the drainage of cerebrospinal fluid. He therefore required a further operation in which the surgeons implanted a ventricular peritoneal shunt. This is a tube with a valve, placed under the skin, which drains the cerebrospinal fluid from the brain to the abdomen where it is absorbed back into the blood.

Watching a child suffer – even when the techniques and operations are life-saving – is an experience that no parent should have to endure. I fully understand the anxieties of young patients’ parents and the long wait for the child to start to recover. Seeing the child re-emerge from CFS/ME is an exhilarating experience, both for parents and the practitioner, and helps maintain the practitioner’s enthusiasm during the long and sometimes arduous treatment programme.

It will get better

As I have already said, while a patient is on the road to recovery, certain additional signs and symptoms may be seen and pain experienced. This is usually a case of it gets worse before it gets better.

Despite these unpleasant signs and symptoms initially, it is now only a matter of time for most CFS/ME sufferers before my treatment starts to work and the characteristics of this debilitating disease begin to recede.

Notes

1. Hartman L. Handbook of Osteopathic Technique. NMK Publishers. Herts; 1983.

2. Stoddard A. Manual of Osteopathic Technique. 3rd edition. Hutchinson, London, 1982.

3. Sutherland WG. The Cranial Bowl. Mankato, Minnesota, US: Free Press Company; 1939.

4. Sutherland WG. In: Wales AL (ed) Teachings in the Science of Osteopathy. Sutherland Cranial Teaching Foundation, Fort Worth, Texas, US; 1990.

5. Saidi G, Haines L. The management of children with chronic fatigue syndrome-like illness in primary care: a cross-sectional study. British Journal of General Practice 2006; 56(522): 43–47.