Dyslexia

Sally E. Shaywitz, Bennett A. Shaywitz

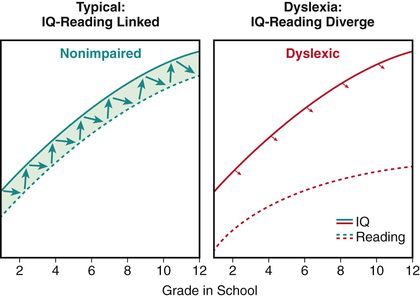

The most current definition of dyslexia is now codified in U.S. Federal law (First Step Act of 2018, PL: 115–391): “The term dyslexia means an unexpected difficulty in reading for an individual who has the intelligence to be a much better reader, most commonly caused by a difficulty in the phonological processing (the appreciation of the individual sounds of spoken language), which affects the ability of an individual to speak, read, and spell.” In typical readers, development of reading and intelligence quotient (IQ) are dynamically linked over time. In dyslexic readers, however, a developmental uncoupling occurs between reading and IQ (Fig. 50.1 ), such that reading achievement is significantly below what would be expected given the individual's IQ. The discrepancy between reading achievement and IQ provides the long-sought empirical evidence for the seeming paradox between cognition and reading in individuals with developmental dyslexia, and this discrepancy is now recognized in the Federal definition as unexpected difficulty in reading.

Etiology

Dyslexia is familial, occurring in 50% of children who have a parent with dyslexia, in 50% of the siblings of dyslexic persons, and in 50% of the parents of dyslexic persons. Such observations have naturally led to a search for genes responsible for dyslexia, and at one point there was hope that heritability would be related to a small number of genes. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), however, have demonstrated that a large number of genes are involved, each producing a small effect. Advances in genetics have confirmed what the GWAS suggested, that complex traits such as reading are the work of thousands of genetic variants, working in concert (see Chapter 99 ). Thus, pediatricians should be wary of recommending any genetic test to their patients that purports to diagnose dyslexia in infancy or before language and reading have even emerged. It is unlikely that a single gene or even a few genes will reliably identify people with dyslexia. Rather, dyslexia is best explained by multiple genes , each contributing a small amount toward the expression of dyslexia.

Epidemiology

Dyslexia is the most common and most comprehensively studied of the learning disabilities, affecting 80% of children identified as having a learning disability. Dyslexia may be the most common neurobehavioral disorder affecting children, with prevalence rates ranging from 20% in unselected population-based samples to much lower rates in school-identified samples. The low prevalence rate in school-identified samples may reflect the reluctance of schools to identify dyslexia. Dyslexia occurs with equal frequency in boys and girls in survey samples in which all children are assessed. Despite such well-documented findings, schools continue to identify more boys than girls, probably reflecting the more rambunctious behavior of boys who come to the teacher's attention because of misbehavior, while girls with reading difficulty, who are less likely to be misbehaving, are also less likely to be identified by the schools. Dyslexia fits a dimensional model in which reading ability and disability occur along a continuum, with dyslexia representing the lower tail of a normal distribution of reading ability.

Pathogenesis

Evidence from a number of lines of investigation indicates that dyslexia reflects deficits within the language system, and more specifically, within the phonologic component of the language system engaged in processing the sounds of speech. Individuals with dyslexia have difficulty developing an awareness that spoken words can be segmented into smaller elemental units of sound (phonemes), an essential ability given that reading requires that the reader map or link printed symbols to sound. Increasing evidence indicates that disruption of attentional mechanisms may also play an important role in reading difficulties.

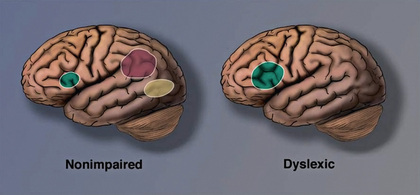

Functional brain imaging in both children and adults with dyslexia demonstrates an inefficient functioning of left hemisphere posterior brain systems, a pattern referred to as the neural signature of dyslexia (Fig. 50.2 ). Although functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) consistently demonstrates differences between groups of dyslexic compared to typical readers, brain imaging is not able to differentiate an individual case of a dyslexic reader from a typical reader and thus is not useful in diagnosing dyslexia.

Clinical Manifestations

Reflecting the underlying phonologic weakness, children and adults with dyslexia manifest problems in both spoken and written language. Spoken language difficulties are typically manifest by mispronunciations, lack of glibness, speech that lacks fluency with many pauses or hesitations and “ums,” word-finding difficulties with the need for time to summon an oral response, and the inability to come up with a verbal response quickly when questioned; these reflect sound-based, not semantic or knowledge-based, difficulties.

Struggles in decoding and word recognition can vary according to age and developmental level. The cardinal signs of dyslexia observed in school-age children and adults are a labored, effortful approach to reading involving decoding, word recognition, and text reading. Listening comprehension is typically robust. Older children improve reading accuracy over time, but without commensurate gains in reading fluency; they remain slow readers. Difficulties in spelling typically reflect the phonologically based difficulties observed in oral reading. Handwriting is often affected as well.

History often reveals early subtle language difficulties in dyslexic children. During the preschool and kindergarten years, at-risk children display difficulties playing rhyming games and learning the names for letters and numbers. Kindergarten assessments of these language skills can help identify children at risk for dyslexia. Although a dyslexic child enjoys and benefits from being read to, the child might avoid reading aloud to the parent or reading independently.

Dyslexia may coexist with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (see Chapter 49 ); this comorbidity has been documented in both referred samples (40% comorbidity) and nonreferred samples (15% comorbidity).

Diagnosis

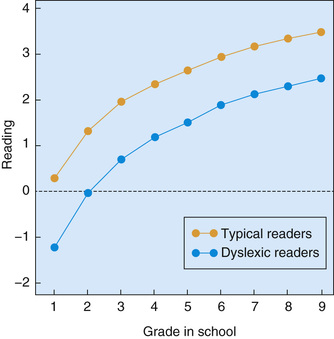

A large achievement gap between typical and dyslexic readers is evident as early as 1st grade and persists (Fig. 50.3 ). These findings provide strong evidence and impetus for early screening and identification of and early intervention for young children at risk for dyslexia. One source of potentially powerful and highly accessible screening information is the teacher's judgment about the child's reading and reading-related skills. Evidence-based screening can be carried out as early as kindergarten, and also in grades 1-3, by the child's teacher. The teachers' responses to a small set of questions (10-12 questions) predict a pool of children who are at risk for dyslexia with a high degree of accuracy. Screening takes less than 10 minutes, is completed on a tablet, and is extremely efficient and economical. Children found to be at-risk will then have further assessment and, if diagnosed as dyslexic, should receive evidence-based intervention.

Dyslexia is a clinical diagnosis, and history is especially critical. The clinician seeks to determine through history, observation, and psychometric assessment, if there are unexpected difficulties in reading (based on the person's intelligence, chronological/grade, level of education or professional status) and associated linguistic problems at the level of phonologic processing. No single test score is pathognomonic of dyslexia. The diagnosis of dyslexia should reflect a thoughtful synthesis of all clinical data available.

Dyslexia is distinguished from other disorders that can prominently feature reading difficulties by the unique, circumscribed nature of the phonologic deficit, one that does not intrude into other linguistic or cognitive domains. A core assessment for the diagnosis of dyslexia in children includes tests of language, particularly phonology; reading, including real and pseudowords; reading fluency; spelling; and tests of intellectual ability. Additional tests of memory, general language skills, and mathematics may be administered as part of a more comprehensive evaluation of cognitive, linguistic, and academic function. Some schools use a response to intervention (RtI) approach to identifying reading disabilities (see Chapter 51.1 ). Once a diagnosis has been made, dyslexia is a permanent diagnosis and need not be reconfirmed by new assessments.

For informal screening, in addition to a careful history, the primary care physician in an office setting can listen to the child read aloud from the child's own grade-level reader. Keeping a set of graded readers available in the office serves the same purpose and eliminates the need for the child to bring in schoolbooks. Oral reading is a sensitive measure of reading accuracy and fluency. The most consistent and telling sign of a reading disability in an accomplished young adult is slow and laborious reading and writing. In attempting to read aloud, most children and adults with dyslexia display an effortful approach to decoding and recognizing single words, an approach in children characterized by hesitations, mispronunciations, and repeated attempts to sound out unfamiliar words. In contrast to the difficulties they experience in decoding single words, persons with dyslexia typically possess the vocabulary, syntax, and other higher-level abilities involved in comprehension.

The failure either to recognize or to measure the lack of fluency in reading is perhaps the most common error in the diagnosis of dyslexia in older children and accomplished young adults. Simple word identification tasks will not detect dyslexia in a person who is accomplished enough to be in honors high school classes or to graduate from college or obtain a graduate degree. Tests relying on the accuracy of word identification alone are inappropriate to use to diagnose dyslexia because they show little to nothing of the struggle to read. Because they assess reading accuracy but not automaticity (speed), the types of reading tests used for school-age children might provide misleading data on bright adolescents and young adults. The most critical tests are those that are timed ; they are the most sensitive in detecting dyslexia in a bright adult. Few standardized tests for young adult readers are administered under timed and untimed conditions; the Nelson-Denny Reading Test is an exception. The helpful Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE) examines simple word reading under timed conditions. Any scores obtained on testing must be considered relative to peers with the same degree of education or professional training.

Management

The management of dyslexia demands a life-span perspective. Early in life the focus is on remediation of the reading problem. Applying knowledge of the importance of early language, including vocabulary and phonologic skills, leads to significant improvements in children's reading accuracy, even in predisposed children. As a child matures and enters the more time-demanding setting of middle and then high school, the emphasis shifts to the important role of providing accommodations. Based on the work of the National Reading Panel, evidence-based reading intervention methods and programs are identified. Effective intervention programs provide systematic instruction in 5 key areas: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension strategies. These programs also provide ample opportunities for writing, reading, and discussing literature.

Taking each component of the reading process in turn, effective interventions improve phonemic awareness: the ability to focus on and manipulate phonemes (speech sounds) in spoken syllables and words. The elements found to be most effective in enhancing phonemic awareness , reading, and spelling skills include teaching children to manipulate phonemes with letters; focusing the instruction on 1 or 2 types of phoneme manipulations rather than multiple types; and teaching children in small groups. Providing instruction in phonemic awareness is necessary but not sufficient to teach children to read. Effective intervention programs include teaching phonics , or making sure that the beginning reader understands how letters are linked to sounds (phonemes) to form letter-sound correspondences and spelling patterns. The instruction should be explicit and systematic; phonics instruction enhances children's success in learning to read, and systematic phonics instruction is more effective than instruction that teaches little or no phonics or teaches phonics casually or haphazardly. Important but often overlooked is starting children on reading connected text early on, optimally at or near the beginning of reading instruction.

Fluency is of critical importance because it allows the automatic, rapid recognition of words, and while it is generally recognized that fluency is an important component of skilled reading, it has proved difficult to teach. Interventions for vocabulary development and reading comprehension are not as well established. The most effective methods to teach reading comprehension involve teaching vocabulary and strategies that encourage active interaction between the reader and the text. Emerging science indicates that it is not only teacher content knowledge but the teacher's skill in engaging the student and focusing the student's attention on the reading task at hand that is required for effective instruction.

For those in high school, college, and graduate school, provision of accommodations most often represents a highly effective approach to dyslexia. Imaging studies now provide neurobiologic evidence of the need for extra time for dyslexic students; accordingly, college students with a childhood history of dyslexia require extra time in reading and writing assignments as well as examinations. Many adolescent and adult students have been able to improve their reading accuracy, but without commensurate gains in reading speed. The accommodation of extra time reconciles the individual's often high cognitive ability and slow reading, so that the exam is a measure of that person's ability rather than his disability. Another important accommodation is teaching the dyslexic student to listen to texts. Excellent text-to-speech programs and apps available for Apple and Android systems include Voice Dream Reader, Immersive Reader (in OneNote as part of Microsoft Office), Kurzweil Firefly, Read & Write Gold, Read: OutLoud, and Natural Reader. Voice-to-text programs are also helpful, often part of the suite of programs as well as the popular Dragon Dictate. Voice to text is found on many smartphones. Other helpful accommodations include the use of laptop computers with spelling checkers, access to lecture notes, tutorial services, and a separate quiet room for taking tests.

In addition, the impact of the primary phonologic weakness in dyslexia mandates special consideration during oral examinations so that students are not graded on their lack of glibness or speech hesitancies but on their content knowledge. Unfortunately, speech hesitancies or difficulties in word retrieval often are wrongly confused with insecure content knowledge. The major difficulty in dyslexia, reflecting problems accessing the sound system of spoken language, causes great difficulty learning a 2nd language. As a result, an often-necessary accommodation is a waiver or partial waiver of the foreign language requirement; the dyslexic student may enroll in a course on the history or culture of a non–English-speaking country.

Prognosis

Application of evidence-based methods to young children (kindergarten to grade 3), when provided with sufficient intensity and duration, can result in improvements in reading accuracy and, to a much lesser extent, fluency. In older children and adults, interventions result in improved accuracy, but not an appreciable improvement in fluency. Accommodations are critical in allowing the dyslexic child to demonstrate his or her knowledge. Parents should be informed that with proper support, dyslexic children can succeed in a range of future occupations that might seem out of their reach, including medicine, law, journalism, and writing.