Math and Writing Disabilities

Math Disabilities

Kenneth L. Grizzle

Data from the U.S. National Center for Educational Statistics for 2009 showed that 69% of U.S. high school graduates had taken algebra 1, 88% geometry, 76% algebra 2/trigonometry, and 35% precalculus. These percentages are considerably higher than those for 20 years earlier. However, concerns remain about the limited literacy level in mathematics for children, adolescents, and those entering the workforce; poor math skills predict numerous social, employment, and emotional challenges. The need for number and math literacy extends beyond the workplace and into daily lives, and weaknesses in this area can negatively impact daily functioning. Research into the etiology and treatment of math disabilities falls far behind the study of reading disabilities (see Chapter 50 ). Therefore the knowledge needed to identify, treat, and minimize the impact of math challenges on daily functioning and education is limited.

Math Learning Disability Defined

Understanding learning challenges associated with mathematics requires a basic appreciation of domain-specific terminology and operations. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) has published diagnostic criteria for learning disorders. Specific types of learning challenges are subsumed under the broad term of specific learning disorder (SLD) . The DSM identifies the following features of a SLD with an impairment in math: difficulties mastering number sense, number facts, or fluent calculation and difficulties with math reasoning. Symptoms must be present for a minimum of 6 mo and persist despite interventions to address the learning challenges. Number sense refers to a basic understanding of quantity, number, and operations and is represented as nonverbal and symbolic. Examples of number sense include an understanding that each number is 1 more or 1 less than the previous or following number; knowledge of number words and symbols; and the ability to compare the relative magnitude of numbers and perform simple arithmetic calculations.

The DSM-5 definition can be contrasted with an education-defined learning disability in mathematics . Two math-related areas are identified as part of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA): mathematics calculation and mathematics problem solving. Operationally, this is reflected in age-level competency in arithmetic and math calculation, word problems, interpreting graphs, understanding money and time concepts, and applying math concepts to solve quantitative problems. The federal government allows states to choose the way a learning disability (LD) is identified if the procedure is “research based.” Referred to specifically in IDEA as methods for identifying an LD are a discrepancy model and “use of a process based on the child's response to scientific, research-based intervention.” The former refers to identifying a LD based on a pronounced discrepancy between intellectual functioning and academic achievement. The latter, referred to as a response to intervention (RtI) model, requires school systems to screen for a disability, intervene using empirically supported treatments for the identified disability, closely monitor progress, and make necessary adjustments to the intervention as needed. If a child is not responding adequately, a multidisciplinary team evaluation is used to develop an individualized educational plan (IEP) .

It is important that primary care providers understand the RtI process because many states require or encourage this approach to identifying LDs. Confusion can be avoided by helping concerned parents understand that a school may review their child's records, screen the skills of concern, and provide intervention with close progress monitoring, before initiating the process for an IEP. Traditional psychoeducation testing (IQ and achievement) may only be completed if a child has not responded well to specific interventions. The RtI approach is a valuable, empirically supported way to approach and identify a potential learning disability, but very different from a medical approach to diagnosis and treatment.

Terminology

The term dyscalculia , often used in medicine and research but seldom used by educators, is reserved for children with a SLD in math when there is a pattern of deficits in learning arithmetic facts and accurate, fluent calculations. The term math learning disability (MLD ) is used generically here, with dyscalculia used when limiting the discussion to children with deficient math calculation skills. A distinction is also made between children with a MLD and those who are low achieving (LA) in math; both groups have received considerable research focus. Although not included in either definition above, research into math deficits typically requires that individuals identified with MLD have math achievement scores below the 10th percentile across multiple grade levels. These children start out poorly in math and continue poor performance across grades, despite interventions. LA math students consistently score below the 25th percentile on math achievement tests across grades, but show more typical entry-level math skills.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

Depending on how MLD is defined and assessed, the prevalence varies. Based on findings from multiple studies, approximately 7% of children will show a MLD profile before high school graduation. An additional 10% of students will be identified as LA. Because research in the area typically requires that individuals show deficits for consecutive years, the respective prevalence estimates are lower than the 10th percentile cutoff for being identified as MLD or the 25th percentile cutoff for being identified as LA. It is not unusual for children to score below the criterion one year and above the criterion in subsequent years. These children do not show the same cognitive deficits associated with a MLD. Unlike dyslexia, boys are at greater risk to experience MLD. This is found in epidemiologic research in the United States (risk ratio, 1.6-2.2 : 1) and various European countries.

Risk Factors

Genetics

The heritability of math skills is estimated to be approximately 0.50. The heritability or genetic influence on math skills is consistent across the continuum from high to low math skills. This research emphasizes that although math skills are learned across time, the stability of math performance is the result of genetic influences. Math heritability appears to be the product of multiple genetic markers, each having a small effect.

Medical/Genetic Conditions

Numerous genetic syndromes are associated with math problems. Although most children with fragile X syndrome have an intellectual disability (ID), approximately 50% of girls with the condition do not. Of those without an ID, ≥75% have a math disability by the end of 3rd grade and are already scoring below average in mathematics in kindergarten and 1st grade. For girls with fragile X MLD, weak working memory seems to play an important role. The frequency of MLD in girls with Turner syndrome (TS) is the same as found in girls with fragile X syndrome. A consistent finding is girls with TS complete math calculations at significantly slower speed than typically developing students. Although girls with TS have weak calculation skills, their ability to complete math problems not requiring explicit calculation is similar to that of their peers. The percentage of children with the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2ds) with MLD is not clear. Younger children with this genetic condition (6-10 yr old) showed similar number sense and calculation skills as typically developing children but weaker math problem solving. Older children with 22q11.2ds showed slower speed in their general number sense and calculations, but accuracy was maintained. Weak counting skills and magnitude comparison have been found in this group of children, suggesting weak visual-spatial processing. Children with myelomeningocele are at greater risk for math difficulties than their unaffected peers. Almost 30% of these children have MLD without an additional diagnosed learning disorder, and >50% have both math and reading learning disorders. While broad, deficits are most pronounced in speed of math calculation and written computation.

Comorbidities

It is estimated that 30–70% of those with MLD will also have reading disability. This is especially important because children with MLD are less likely to be referred for additional educational assistance and intervention than students with reading problems. Unfortunately, children identified with both learning challenges perform poorer across psychosocial and academic measures than children with MLD alone. Having a MLD places a child at greater risk for not only other learning challenges but also psychiatric disorders, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and major depressive disorder. Individuals with MLD have been found to have increased social isolation and difficulties developing social relationships in general.

Causes of Math Learning Disability

There is a consensus that individuals with MLD are a heterogeneous group, with multiple potential broad and specific deficits driving their learning difficulties. Research into the causes of MLD has focused on math-specific processes and broad cognitive deficits, with an appreciation that these two factors are not always independent.

Broad Cognitive Processes

Intelligence

Intelligence affects learning, but if intellectual functioning were the primary driver of poor math performance, the math skills of low-IQ children would be similar or worse than individuals with MLD. On the contrary, children with MLD have significantly poorer math achievement than children with low IQ. Children with MLD have severe deficits in math not accounted for by their cognitive functioning. Individuals with lower cognition may have difficulty learning mathematics, but their math skills are likely to be commensurate with their intelligence.

Working Memory

Working memory refers to the ability to keep information in mind while using the information in other mental processes. Working memory is composed of 3 core systems: the central executive, the language-related phonologic loop, and the visual-based sketch pad. The central executive coordinates the functioning of the other two systems. All three play a role in various aspects of learning and in the development and application of math skills in particular; children with MLD have shown deficits in each area.

Processing Speed

Individuals with MLD are often slower to complete math problems than their typically developing peers, a result of their poor fact retrieval rather than broader speed of processing deficits. However, young children later identified with a MLD when beginning school have number-processing speed that is considerably slower than same-age same-grade peers.

Math-Specific Processes

Procedural Errors

The type of errors made by children with a MLD are typical for any child, the difference being that children with a learning disability show a 2-3 yr lag in understanding the concept. An example of a common error a 1st grade child with a MLD might make when “counting on” is to undercount: “6 + 2= ?;” “6, 7” rather than starting at 6 and counting an additional 2 numbers. As children with math deficits get older, it is common to subtract a larger number from a smaller number. For example, in the problem “63 − 29 = 46,” the child makes the mistake of subtracting 3 from 9. Another common error is not decreasing the number in the 10s column when borrowing: “64 − 39 = 35.” For both adding and subtracting, there is a lack of understanding of the commutative property of numbers and a tendency to use repeated addition rather than fact retrieval. It is not that children with a MLD do not develop these skills, it is that they develop them much later than their peers, thereby making the transition to complicated math concepts much more challenging.

Memory for Math Facts

Committing math facts to or retrieving facts from memory have consistently been found to be problematic for children with MLD. Weak fact encoding or retrieval alone do not determine a MLD diagnosis. Many math curricula in the United States do not include development of math facts as a part of the instructional process, resulting in children not knowing basic facts.

Unlike dyslexia, in which deficits have been isolated and identified as causal (see Chapter 50 ), factors involved in the development of a MLD are much more heterogeneous. Alone, none of the processes previously outlined fully accounts for MLD, although all have been implicated as problematic for those struggling with math.

Treatment and Interventions

The most effective interventions for MLD are those that include explicit instruction on solving specific types of problems and that take place over several weeks to several months. Skill-based instruction is a critical component; general math problem solving will not carry over across various math skills, unless the skill is part of a more complex math concept. Clear, comprehensive guidelines for effective interventions for students struggling with math have been provided by the U.S. Department of Education in the form of a Practice Guide released through the What Works Clearinghouse. This document gives excellent direction in the identification and treatment of children with math difficulties in the educational system. Although not intended for medical personnel or parents, the guide is available free of charge and can be helpful for parents when talking to teachers about their child's learning. Table 51.1 lists additional resources for parents concerned about their young child's development of math facts.

Awareness that most public school systems have implemented some form of a RtI to identify learning disabilities allows the primary care physician to encourage parents to return to the school seeking an intervention to address their child's concern. Receiving special education services in the form of an IEP may be necessary for some children. However, the current approach to identifying children with a learning disability allows school systems to intervene earlier, when problems arise, and potentially avoid the need for an IEP. Pediatricians with patients whose parents have received feedback from school with any of the risk factors outlined in Table 51.2 should encourage the parents to discuss an intervention plan with the child's teacher.

Bibliography

Bartelet D, Ansari D, Vaessen A, Blomert L. Cognitive subtypes of mathematics learning difficulties in primary education. Res Dev Disabil . 2014;35(3):657–670.

Chodura S, Kuhn JT, Holling H. Interventions for children with mathematical difficulties: a meta-analysis. Z Psychol . 2015;223(2):129–144.

Docherty SJ, Davis OSP, Kovas Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple loci associated with mathematics ability and disability. Genes Brain Behav . 2010;9:234–247.

Geary DC. Mathematical cognition deficits in children with learning disabilities and persistent low achievement: a five-year prospective study. J Educ Psychol . 2012;104(1):206–223.

Kaufman L, Mazzocco MM, Dowker A, et al. Dyscalculia from a developmental and differential perspective. Front Psychol . 2013;4:1–5.

Kucian K. Developmental dyscalculia and the brain. Berch DB, Geary DC, Koepke KM. Development of mathematical cognition: neural substrates and genetic influences . Elsevier: New York; 2016:165–193.

Mazzocco M. Mathematics awareness month: why should pediatricians be aware of mathematics and numeracy? J Dev Behav Pediatr . 2016;37:251–253.

Mazzocco MM, Quintero AI, Murphy MM, McCloskey M. Genetic syndromes as model pathways to mathematical learning difficulties: fragile X, Turner and 22q deletion syndromes. Berch DB, Geary DC, Koepke KM. Development of mathematical cognition: neural substrates and genetic influences . Elsevier: New York; 2016:325–357.

Petrill SA, Kovas Y. Individual differences in mathematics ability: a behavioral genetic approach. Berch DB, Geary DC, Koepke KM. Development of mathematical cognition: neural substrates and genetic influences . Elsevier: New York; 2016:299–324.

Shin MS, Bryant DP. A synthesis of mathematical and cognitive performances of students with mathematics learning disabilities. J Learn Disabil . 2015;48:96–112.

Writing Disabilities

Kenneth L. Grizzle

Oral language is a complex process that typically develops in the absence of formal instruction. In contrast, written language requires instruction in acquisition (word reading), understanding (reading comprehension), and expression (spelling and composition). Unfortunately, despite reasonable pedagogy, a subset of children struggle with development in one or several of these areas. The disordered output of written language is currently referred to within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as a specific learning disorder with impairment in written expression (Table 51.3 ).

Various terminology has been used when referring to individuals with writing deficits; this subchapter uses the term impairment in written expression (IWE) rather than “writing disorder” or “disorder of written expression.” Dysgraphia is often used when referring to children with writing problems, sometimes synonymously with IWE, although the two are related but distinct conditions. Dysgraphia is primarily a deficit in motor output (paper/pencil skills), and IWE is a conceptual weakness in developing, organizing, and elaborating on ideas in writing.

The diagnoses of a IWE and dysgraphia are made largely based on phenotypical presentation; spelling, punctuation, grammar, clarity, and organization are factors to consider with IWE concerns. Aside from these potentially weak writing characteristics, however, no other guidelines are offered. Based on clinical experience and research into the features of writing samples of children with disordered writing skills, one would expect to see limited output, poor organization, repetition of content, and weak sentence structure and spelling, despite the child taking considerable time to produce a small amount of content. For those with comorbid dysgraphia, the legibility of their writing product will also be poor, sometimes illegible.

Epidemiology

The incidence of IWE is estimated at 6.9–14.7%, with the relative risk for IWE 2-2.9 times higher for boys than girls. One study covering three U.S. geographic regions found considerably higher rates of IWE in the Midwest and Southeast than in the West.

The risk for writing problems is much greater among select populations; >50% of children with oral language disorders reportedly have IWE. The relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and learning disorders in general is well established, including IWE estimates in the 60% range for the combined and inattentive presentations of ADHD. Because of the importance of working memory and other executive functions in the writing process, any child with weakness in these areas will likely find the writing process difficult (see Chapter 48 ).

Skill Deficits Associated With Impaired Writing

Written language, much like reading, occurs along a developmental trajectory that can be seamless as children master skills critical to the next step in the process. Mastery of motor control that allows a child to produce letters and letter sequences frees up cognitive energy to devote to spelling words and eventually stringing words into sentences, paragraphs, and complex composition. Early in the development of each individual skill, considerable cognitive effort is required, although ideally the lower-level skills of motor production, spelling, punctuation, and capitalization (referred to as writing mechanics or writing conventions ) will gradually become automatic and require progressively less mental effort. This effort can then be devoted to higher-level skills, such as planning, organization, application of knowledge, and use of varied vocabulary. For children with writing deficits, breakdowns can occur at one, some, or every stage.

Transcription

Among preschool and primary grade children, there is a wide range of what is considered “developmentally typical” as it relates to letter production and spelling. However, evidence indicates that poor writers in later grades are slow to produce letters and write their name in preschool and kindergarten. Weak early spelling and reading skills (letter identification and phonologic awareness; see Chapter 50 ) and weak oral language have also been found to predict weak writing skills in later elementary grades. Children struggling to master early transcription skills tend to write slowly, or when writing at reasonable speed, the legibility of their writing degrades. Output in quantity and variety is limited, and vocabulary use in poor spellers is often restricted to words they can spell.

As children progress into upper elementary school and beyond, a new set of challenges arise. They are now expected to have mastered lower-level transcription skills, and the focus turns to the application of these skills to more complex text generation. In addition to transcription, this next step requires the integration of additional cognitive skills that have yet to be tapped by young learners.

Oral Language

Language, although not speech, has been found to be related to writing skills. Writing difficulties are associated with deficits in both expression and comprehension of oral language. Writing characteristics of children with specific language impairment (SLI) can differ from their unimpaired peers early in the school experience, and persist through high school (see Chapter 52 ). In preschool and kindergarten, as a group, children with language disorders show poorer letter production and ability to print their name. Poor spelling and weak vocabulary also contribute to the poor writing skills. Beyond primary grades, the written narratives of SLI children tend to be evaluated as “lower quality with poor organization” and weaker use of varied vocabulary.

Pragmatic language and higher-level language deficits also negatively impact writing skills. Pragmatic language refers to the social use of language, including, though not limited to greeting and making requests; adjustments to language used to meet the need of the situation or listener; and following conversation rules verbally and nonverbally. Higher-level language goes beyond basic vocabulary, word form, and grammatical skills and includes making inferences, understanding and appropriately using figurative language, and making cause-and-effect judgments. Weaknesses in these areas, with or without intact foundational language, can present challenges for students in all academic areas that require writing. For example, whether producing an analytic or narrative piece, the writer must understand the extent of the reader's background knowledge and in turn what information to include and omit, make an argument for a cause-and-effect relationship, and use content-specific vocabulary or vocabulary rich in imagery and nonliteral interpretation.

Executive Functions

Writing is a complicated process and, when done well, requires the effective integration of multiple processes. Executive functions (EFs) are a set of skills that include planning, problem solving, monitoring and making adjustments as needed (see Chapter 48 ). Three recursive processes have consistently been reported as involved in the writing process: translation of thought into written output, planning, and reviewing. Coming up with ideas, while challenging for many, is simply the first step when writing a narrative (story). Once an idea has emerged, the concept must be developed to include a plot, characters, and story line and then coordinated into a coherent whole that is well organized and flows from beginning to end. Even if one develops ideas and begins to write them down, persistence is required to complete the task, which requires self-regulation. Effective writers rely heavily on EFs, and children with IWE struggle with this set of skills. Poor writers seldom engage in the necessary planning and struggle to self-monitor and revise effectively.

Working Memory

Working memory (WM) refers to the ability to hold, manipulate, and store information for short periods. The more space available, the more memory can be devoted to problem solving and thinking tasks. Nevertheless, there is limited space in which information can be held, and the more effort devoted to one task, the less space is available to devote to other tasks. WM has consistently been shown to play an important role in the writing process, because weak WM limits the space available. Further, when writing skills that are expected to be automatic continue to require effort, precious memory is required, taking away what would otherwise be available for higher-level language.

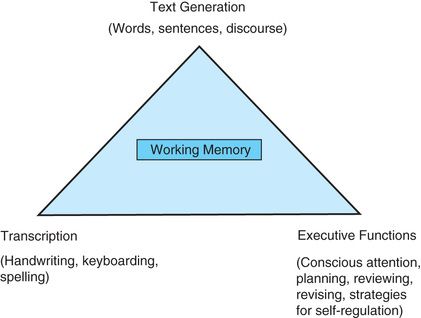

The Simple View of Writing is an approach that integrates each of the 4 ideas just outlined to describe the writing process (Fig. 51.1 ). At the base of the triangle are transcription and executive functions, which support, within WM, the ability to produce text. Breakdowns in any of these areas can lead to poor writing, and identifying where the deficit(s) are occurring is essential when deciding to treat the writing problem. For example, children with weak graphomotor skills (e.g., dysgraphia) must devote considerable effort to the accurate production of written language, thereby increasing WM use devoted to lower-level transcription and limiting memory that can be used for developing discourse. The result might be painfully slow production of a legible story, or a passage that is largely illegible. If, on the other hand, a child's penmanship and spelling have developed well, but their ability to persist with challenging tasks or to organize their thoughts and develop a coordinated plan for their paper is limited, one might see very little information written on the paper despite considerable time devoted to the task. Lastly, even when skills residing at the base of this triangle are in place, students with a language disorder will likely produce text that is more consistent with their language functioning than their chronological grade or age (Fig. 51.1 ).

Treatment

Poor writing skills can improve with effective treatment. Weak graphomotor skills may not necessarily require intervention from an occupational therapist (OT), although Handwriting Without Tears is a curriculum frequently used by OTs when working with children with poor penmanship. An empirically supported writing program has been developed by Berninger, but it is not widely used inside or outside school systems (PAL Research-Based Reading and Writing Lessons). For children with dysgraphia, lower-level transcription skills should be emphasized to the point of becoming automatic. The connection between transcription skills and composition should be included in the instructional process; that is, children need to see how their work at letter production is related to broader components of writing. Further, because of WM constraints that frequently impact the instructional process for students with learning disorders, all components of writing should be taught within the same lesson.

Explicit instruction of writing strategies combined with implementation and coaching in self-regulation will likely produce the greatest gains for students with writing deficits. Emphasis will vary depending on the deficit specific to the child. A well-researched and well-supported intervention for poor writers is self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) . The 6 stages in this model include developing and activating a child's background knowledge; introducing and discussing the strategy that is being taught; modeling the strategy for the student; assisting the child in memorization of the strategy; supporting the child's use of the strategy during implementation; and independent use of the strategy. SRSD can be applied across various writing situations and is supported until the student has developed mastery. The model can emphasize or deemphasize the areas most needed by the child.

Educational Resources

Children with identified learning disorders can potentially qualify for formal education programming through special education or a section 504 plan. Special education is guided on a federal level by the Individual with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and includes development of an individual education plan (see Chapter 48 ). A 504 plan provides accommodations to help children succeed in the regular classroom. Accommodations that might be provided to a child with IWE, through an IEP or a 504 plan, include dictation to a scribe when confronted with lengthy writing tasks, additional time to complete exams that require writing, and use of technology such as keyboarding, speech-to-text software, and writing devices that record teacher instruction. When recommending that parents pursue assistive technology for their child as a potential accommodation, the physician should emphasize the importance of instruction to mastery of the device being used. Learning to use technology effectively requires considerable time and is initially likely to require additional effort, which can result in frustration and avoidance.

Bibliography

Andrews JE, Lombardino LJ. Strategies for teaching handwriting to children with writing disabilities. Perspect Lang Learn Educ . 2014;21:114–126.

Berninger VW. Preventing written expression disabilities through early and continuing assessment and intervention for handwriting and/or spelling problems: research into practice. Swanson HL, Harris KR, Graham S. Handbook of learning disabilities . The Guilford Press: New York; 2003:35–363.

Berninger VW. Process assessment of the learner (PAL): research-based reading and writing lessons . Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX; 2003.

Berninger VW. Interdisciplinary frameworks for schools: best professional practices for serving the needs of all students . American Psychological Association: Washington, DC; 2015.

Berninger VW, May MO. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment for specific learning disabilities involving impairments in written and/or oral language. J Learn Disabil . 2011;44(2):167–183.

Dockrell JE. Developmental variations in the production of written text: challenges for students who struggle with writing. Stone CA, Silliman ER, Ehren BJ, Wallach GP. Handbook of language and literacy . ed 2. The Guilford Press: New York; 2014:505–523.

Dockrell JE, Lindsay G, Connelly V. The impact of specific language impairment on adolescents' written text. Except Child . 2009;75(4):427–446.

Graham S, Harris KR. Writing better: effective strategies for teaching students with learning difficulties . Paul H Brookes Publishing: Baltimore; 2005.

Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Barbaresi WJ. The forgotten learning disability: epidemiology of written-language disorder in a population-based birth cohort (1976-1982), Rochester, Minnesota. Pediatrics . 2009;123(5):1306–1313.

Paul R, Norbury C. Language disorders from infancy through adolescence: listening, speaking, reading, writing, and communicating . Elsevier: St Louis; 2012.

Silliman ER, Berninger VW. Cross-disciplinary dialogue about the nature of oral and written language problems in the context of developmental, academic, and phenotypic profiles. Top Lang Disord . 2011;31:6–23.

Stoeckel RE, Colligan RC, Barbaresi WJ, et al. Early speech-language impairment and risk for written language disorder: a population-based study. J Dev Behav Pediatr . 2013;34(1):38–44.

Sun L, Wallach GP. Language disorders are learning disabilities: challenges on the divergent and diverse paths to language learning disability. Top Lang Disord . 2014;34:25–38.

Williams GJ, Larkin RF, Blaggan S. Written language skills in children with specific language impairment. Int J Lang Commun Disord . 2013;48(2):160–171.