Neurodevelopmental and Executive Function and Dysfunction

Desmond P. Kelly, Mindo J. Natale

Terminology and Epidemiology

A neurodevelopmental function is a basic brain process needed for learning and productivity. Executive function (EF) is an umbrella term used to describe specific neurocognitive processes involved in the regulating, guiding, organizing, and monitoring of thoughts and actions to achieve a specific goal. Processes considered to be “executive” in nature include inhibition/impulse control, cognitive/mental flexibility, emotional control, initiation skills, planning, organization, working memory, and self-monitoring. Neurodevelopmental and/or executive dysfunctions reflect any disruptions or weaknesses in these processes, which may result from neuroanatomic or psychophysiologic malfunctioning. Neurodevelopmental variation refers to differences in neurodevelopmental functioning. Wide variations in these functions exist within and between individuals. These differences can change over time and need not represent pathology or abnormality.

Neurodevelopmental and/or executive dysfunction places a child at risk for developmental, cognitive, emotional, behavioral, psychosocial, and adaptive challenges. Preschool-age children with neurodevelopmental or executive dysfunction may manifest delays in developmental domains such as language, motor, self-help, or social-emotional development and self-regulation. For the school-age child, an area of particular focus is academic skill development. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) classifies academic disorder within the group of neurodevelopmental disorders as specific learning disorder (SLD) , with broadened diagnostic criteria recognizing impairments in reading, written expression, and mathematics. In the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), neurodevelopmental disorders include specific developmental disorders of scholastic skills with specific reading disorder, mathematics disorder, and disorder of written expression. Dyslexia is categorized separately in ICD-10 under “Symptoms and Signs Not Elsewhere Classified.” Frontal lobe and executive function deficit is also included in this category. Disorders of executive function have traditionally been viewed as a component of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder ( ADHD) , which is also classified in DSM-5 as a neurodevelopmental disorder.

There are no prevalence estimates specifically for neurodevelopmental dysfunction, but overall estimates for learning disorders range from 3–10% with a similar range reported for ADHD. These disorders frequently co-occur. The range in prevalence is likely related to differences in definitions and criteria used for classification and diagnosis, as well as differences in methods of assessment.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Neurodevelopmental and executive dysfunction may result from a broad range of etiologic factors, including genetic, medical, psychological, environmental, and sociocultural influences.

There is a high degree of heritability reported in learning and attention disorders, with estimates ranging from 45–80%. Specific genes have been identified that are associated with reading disorders, including the DYX2 locus on chromosome 6p22 and the DYX3 locus on 2p12. Neuroimaging studies have confirmed links between gene variations and variations in cortical thickness in areas of the brain known to be associated with learning and academic performance, such as the temporal regions. Chromosomal abnormalities can lead to unique patterns of dysfunction, such as visual-spatial deficits in girls diagnosed with Turner syndrome (see Chapter 98.4 ) or executive and language deficits in children with fragile X syndrome (Chapter 98.5 ). Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (velocardiofacial-DiGeorge syndrome; Chapter 98.3 ) has been associated with predictable patterns of neurodevelopmental and executive dysfunction that can be progressive, including a higher prevalence of intellectual disability, as well as deficits in visual-spatial processing, attention, working memory, verbal learning, arithmetic, and language.

Genetic vulnerabilities may be further influenced by perinatal factors, including very low birthweight, severe intrauterine growth restriction, perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and prenatal exposure to substances such as alcohol and drugs. Increased risk of neurodevelopmental and executive dysfunction has also been associated with environmental toxins, including lead (see Chapter 739 ); drugs such as cocaine; infections such as meningitis, HIV, and Zika; and brain injury secondary to intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, or head trauma. The academic effects of concussion in children and adolescents, although usually temporary, have been well characterized, including impaired concentration and slowed processing speed. Repeated injuries have a much higher likelihood of long-term negative neurocognitive effects.

Early psychological trauma may result in both structural and neurochemical changes in the developing brain, which may contribute to neurodevelopmental and executive dysfunction. Findings suggest that the effects of exposure to trauma or abuse early in the developmental course can induce disruption of the brain's regulatory system and may influence right hemisphere function with associated risk for problems with information processing, memory, focus, and self-regulation. Environmental and sociocultural deprivation can lead to, or potentiate, neurodevelopmental and executive dysfunction, and numerous studies have indicated that parent/caregiver executive functioning impacts the development of EFs in offspring.

With regard to pathogenesis , investigations of neuroanatomic substrates have yielded important information about the underlying mechanisms in neurodevelopmental and executive dysfunction. Multiple neurobiologic investigations have identified differences in the left parietotemporal and left occipitotemporal brain regions of individuals with dyslexia compared to those without reading difficulties (see Chapter 50 ). Studies have also described the neural circuitry, primarily in the parietal cortex, underlying mathematical competencies such as the processing of numerical magnitude and mental arithmetic. The associations between executive dysfunction and the prefrontal/frontal cortex have been well established, and insults to the frontal lobe regions often result in dysfunction of executive abilities (e.g., poor inhibitory control). Although the prefrontal/frontal cortex may be the primary control region for EFs, there is considerable interconnectivity between the brain's frontal regions and other areas, such as arousal systems (reticular activating system), motivational and emotional systems (limbic system), cortical association systems (posterior/anterior; left/right hemispheres), and input/output systems (frontal motor/posterior sensory areas).

Core Neurodevelopmental Functions

The neurodevelopmental processes that are critical to a child's successful functioning may best be understood as falling within core neurodevelopmental domains . Notwithstanding such classification of domains, the clinical distinctions often made regarding “cognitive” processes (e.g., intelligence, EF, attention, language, memory) are relatively artificial because these brain functions are highly integrated.

Sensory and Motor Function

Sensory development (e.g., auditory, visual, tactile, proprioceptive) begins well before birth. This neurodevelopmental process is crucial in helping children experience, understand, and manipulate their environments. Sensory development progresses in association with environmental exposure and with the development of other cognitive processes, such as motor development. Through sensory experiences, children's brains mature as new neuronal pathways are created and existing pathways are strengthened.

There are three distinct, yet related, forms of neuromotor ability: fine motor, graphomotor, and gross motor coordination. Fine motor function reflects the ability to control the muscles and bones to produce small, exact movements. Deficits in fine motor function can disrupt the ability to communicate in written form, to excel in artistic and crafts activities, and can interfere with learning a musical instrument or mastering a computer keyboard. The term dyspraxia relates to difficulty in developing an ideomotor plan and activating coordinated and integrated visual-motor actions to complete a task or solve a motor problem, such as assembling a model. Graphomotor function refers to the specific motor aspects of written output. Several subtypes of graphomotor dysfunction can significantly impede writing. Children who harbor weaknesses of visualization during writing have trouble picturing the configurations of letters and words as they write (orthographics), with poorly legible written output with inconsistent spacing between words. Others have weaknesses in orthographic memory and may labor over individual letters and prefer printing (manuscript) to cursive writing. Some exhibit signs of finger agnosia and have trouble localizing their fingers while they write, needing to keep their eyes very close to the page and applying excessive pressure to the pencil. Others struggle producing the highly coordinated motor sequences needed for writing, a phenomenon also described as dyspraxic dysgraphia . It is important to emphasize that a child may show excellent fine motor dexterity (as revealed in mechanical or artistic domains) but very poor graphomotor fluency (with labored or poorly legible writing).

Gross motor function refers to control of large muscles. Children with gross motor incoordination often have problems in processing “outer spatial” information to guide gross motor actions. Affected children may be inept at catching or throwing a ball because they cannot form accurate judgments about trajectories in space. Others demonstrate diminished body position sense. They do not efficiently receive or interpret proprioceptive and kinesthetic feedback from peripheral joints and muscles. They are likely to evidence difficulties when activities demand balance and ongoing tracking of body movement. Others are unable to satisfy the motor praxis demands of certain gross motor activities. It may be difficult for them to recall or plan complex motor procedures such as those needed for dancing, gymnastics, or swimming.

Language

Language is one of the most critical and complex cognitive functions and can be broadly divided into receptive (auditory comprehension/understanding) and expressive (speech and language production and/or communication) functions. Children who primarily experience receptive language problems may have difficulty understanding verbal information, following instructions and explanations, and interpreting what they hear. Expressive language weaknesses can result from problems with speech production and/or problems with higher-level language development. Speech production difficulties include oromotor problems affecting articulation, verbal fluency, and naming. Some children have trouble with sound sequencing within words. Others find it difficult to regulate the rhythm or prosody of their verbal output. Their speech may be dysfluent, hesitant, and inappropriate in tone. Problems with word retrieval can result in difficulty finding exact words when needed (as in a class discussion) or substituting definitions for words (circumlocution).

The basic components of language include phonology (ability to process and integrate the individual sounds in words), semantics (understanding the meaning of words), syntax (mastery of word order and grammatical rules), discourse (processing and producing paragraphs and passages), metalinguistics (ability to think about and analyze how language works and draw inferences), and pragmatics (social understanding and application of language). Children who evidence higher-level expressive language impediments have trouble formulating sentences, using grammar acceptably, and organizing spoken (and possibly written) narratives.

To one degree or another, all academic skills are taught largely through language, and thus it is not surprising that children who experience language dysfunction often experience problems with academic performance. In fact, some studies suggest that up to 80% of children who present with a specific learning disorder also experience language-based weaknesses. Additionally, the role of language in executive functioning cannot be understated, since language serves to guide cognition and behavior.

Visual-Spatial/Visual-Perceptual Function

Important structures involved in the development and function of the visual system include the retina, optic cells (e.g., rods and cones), the optic chiasm, the optic nerves, the brainstem (control of automatic responses, e.g., pupil dilation), the thalamus (e.g., lateral geniculate nucleus for form, motion, color), and the primary (visual space and orientation) and secondary (color perception) visual processing regions located in and around the occipital lobe. Other brain areas, considered to be outside of the primary visual system, are also important to visual function, helping to process what (temporal lobe) is seen and where it is located in space (parietal lobe). It is now well documented that the left and right cerebral hemispheres interact considerably in visual processes, with each hemisphere possessing more specialized functions, including left hemisphere processing of details, patterns, and linear information and right hemisphere processing of the gestalt and overall form.

Critical aspects of visual processing development in the child include appreciation of spatial relations (ability to perceive objects accurately in space in relation to other objects), visual discrimination (ability to differentiate and identify objects based on their individual attributes, e.g., size, shape, color, form, position), and visual closure (ability to recognize or identify an object even when the entire object cannot be seen). Visual-spatial processing dysfunctions are rarely the cause of reading disorders, but some investigations have established that deficits in orthographic coding (visual-spatial analysis of character-based systems) can contribute to reading disorders. Spelling and writing can emerge as a weakness because children with visual processing problems usually have trouble with the precise visual configurations of words. In mathematics, these children often have difficulty with visual-spatial orientation, with resultant difficulty aligning digits in columns when performing calculations and difficulty managing geometric material. In the social realm, intact visual processing allows a child to make use of visual or physical cues when communicating and interpreting the paralinguistic aspects of language. Secure visual functions are also necessary to process proprioceptive and kinesthetic feedback and to coordinate movements during physical activities.

Intellectual Function

A useful definition of intellectual function is the capacity to think in the abstract, reason, problem-solve, and comprehend. The concept of intelligence has had many definitions and theoretical models, including Spearman's unitary concept of “the g-factor,” the “verbal and nonverbal” theories (e.g., Binet, Thorndike), the 2-factor theory from Catell (crystallized vs fluid intelligence), Luria's simultaneous and successive processing model, and more recent models that view intelligence as a global construct composed of more-specific cognitive functions (e.g., auditory and visual-perceptual processing, spatial abilities, processing speed, working memory).

The expression of intellect is mediated by many factors, including language development, sensorimotor abilities, genetics, heredity, environment, and neurodevelopmental function. When an individual's measured intelligence is >2 standard deviations below the mean (a standard score of <70 on most IQ tests) and accompanied by significant weaknesses in adaptive skills, the diagnosis of intellectual disability may be warranted (see Chapter 53 ).

Functionally, some common characteristics distinguish children with deficient intellectual functioning from those with average or above-average abilities. Typically, those at the lowest end of the spectrum (e.g., profound or severe intellectual deficiencies) are incapable of independent function and require a highly structured environment with constant aid and supervision. At the other end of the spectrum are those with unusually well-developed intellect (“gifted”). Although this level of intellectual functioning offers many opportunities, it can also be associated with functional challenges related to socialization and learning and communication style. Individuals whose intellect falls in the below-average range (sometimes referred to as the “borderline” or “slow learner” range) tend to experience greater difficulty processing and managing information that is abstract, making connections between concepts and ideas, and generalizing information (e.g., may be able to comprehend a concept in one setting but are unable to carry it over and apply it in different situation). In general, these individuals tend to do better when information is presented in more concrete and explicit terms, and when working with rote information (e.g., memorizing specific material). Stronger intellect has been associated with better-developed concept formation, critical thinking, problem solving, understanding and formulation of rules, brainstorming and creativity, and metacognition (ability to “think about thinking”).

Memory

Memory is a term used to describe the cognitive mechanism by which information is acquired, retained, and recalled. Structurally, some major brain areas involved in memory processing include the hippocampus, fornix, temporal lobes, and cerebellum, with connections in and between most brain regions. The memory system can be partitioned into subsystems based on processing sequences; the form, time span, and method of recall; whether memories are conscious or unconsciously recalled; and the types of memory impairments that can occur.

Once information has been identified (through auditory, visual, tactile, and/or other sensory processes), it needs to be encoded and registered , a mental process that constructs a representation of the information into the memory system. The period (typically seconds) during which this information is being held and/or manipulated for registration, and ultimately encoded, consolidated, and retained, is referred to as working memory . Other descriptors include short-term memory and immediate memory . Consolidation and storage represent the process by which information in short-term memory is transferred into long-term memory . Information in long-term memory can be available for hours or as long as a life span. Long-term memories are generally thought to be housed, in whole or in part, in specific brain regions (e.g., cortex, cerebellum). Ordinarily, consolidation in long-term memory is accomplished in 1 or more of 4 ways: pairing 2 bits of information (e.g., a group of letters and the English sound it represents); storing procedures (consolidating new skills, e.g., the steps in solving mathematics problems); classifying data in categories (filing all insects together in memory); and linking new information to established rules, patterns, or systems of organization (rule-based learning).

Once information finds its way into long-term memory, it must be accessed. In general, information can be retrieved spontaneously (a process known as free recall ) or with the aid of cues (cued or recognition recall ). Some other common descriptors of memory include anterograde memory (capacity to learn from a single point in time forward), retrograde memory (capacity to recall information that was already learned), and explicit memory (conscious awareness of recall), implicit memory (subconscious recall: no awareness that the memory system is being activated), procedural memory (memory for how to do things), and prospective memory or remembering to remember . Automatization reflects the ability to instantaneously access what has been learned in the past with no expenditure of effort. Successful students are able to automatically form letters, master mathematical facts, and decode words.

Social Cognition

The development of effective social skills is heavily dependent on secure social cognition, which consists of mental processes that allow an individual to understand and interact with the social environment. Although some evidence shows that social cognition exists as a discrete area of neurodevelopmental function, multiple cognitive processes are involved with social cognition. These include the ability to recognize, interpret, and make sense of the thoughts, communications (verbal and nonverbal), and actions of others; the ability to understand that others' perceptions, perspectives, and intentions might differ from one's own (commonly referred to as “theory of mind”); the ability to use language to communicate with others socially (pragmatic language); and the ability to make inferences about others and the environment based on contextual information. It can also be argued that social cognition involves processes associated with memory and EFs such as flexibility.

Executive Function

The development of EFs begins very early on in the developmental course (early indications of inhibitory control and even working memory have been found in infancy), matures significantly during the preschool years, and continues to develop through adolescence and well into adulthood. Some studies suggest that secure EF may be more important than intellectual ability for academic success and have revealed that a child's ability to delay gratification early in life predicts competency, attention, self-regulation, frustration tolerance, aptitude, physical and mental health, and even substance dependency in adolescence and adulthood. Conversely, deficits in other areas of neurodevelopment, such as language development, impact EF.

Attention is far from a unitary, independent, or specific brain function. This may be best illustrated through the phenotype associated with ADHD) (see Chapter 49 ). Disordered attention can result from faulty mechanisms in and across subdomains of attention. These subdomains include selective attention (ability to focus attention on a particular stimulus and to discriminate relevant from irrelevant information), divided attention (ability to orient to more than one stimulus at a given time), sustained attention (ability to maintain one's focus), and alternating attention (capacity to shift focus between stimuli).

Attention problems in children can manifest at any point, from arousal through output. Children with diminished alertness and arousal can exhibit signs of mental fatigue in a classroom or when engaged in any activity requiring sustained focus. They are apt to have difficulty allocating and sustaining their concentration, and their efforts may be erratic and unpredictable, with extreme performance inconsistency. Weaknesses of determining saliency often result in focusing on the wrong stimuli, at home, in school, and socially, and missing important information. Distractibility can take the form of listening to extraneous noises instead of a teacher, staring out the window, or constantly thinking about the future. Attention dysfunction can affect the output of work, behavior, and social activity. It is important to appreciate that most children with attentional dysfunction also harbor other forms of neurodevelopmental dysfunction that can be associated with academic disorders (with some estimates suggesting up to 60% comorbidity).

Inhibitory control (IC) can be described as one's ability to restrain, resist, and not act (cognitively or behaviorally/emotionally) on a thought. IC may also be seen as one's ability to stop thoughts or ongoing actions. Deficits in this behavioral/impulse regulation mechanism are a core feature of the combined or hyperactive impulsive presentation of ADHD and have a significant adverse impact on a child's overall functioning. In everyday settings, children with weak IC may exhibit difficulties with self-control and self-monitoring of their behavior and output (e.g., impulsivity), may not recognize their own errors or mistakes, and often act prematurely and without consideration of the potential consequences of their actions. In the social context, disinhibited children may interrupt others and demonstrate other impulsive behaviors that often interfere with interpersonal relationships. The indirect consequences of poor IC often lead to challenges with behavior, emotional, and academic functioning and social interaction (Table 48.1 ).

Table 48.1

Working memory (WM) can be defined as the ability to hold, manipulate, and store information for short periods. This function is critical to be able to complete multistep problems and more complex instructions and tasks. In its simplest form, WM involves the interaction of short-term verbal and visual processes (e.g., memory, phonologic, awareness, and spatial skills) with a centralized control mechanism that is responsible for coordinating all the cognitive processes involved (e.g., temporarily suspending information in memory while working with it). Developmentally, WM capacity can double or triple between the preschool years and adolescence. When doing math, a child with WM dysfunction might carry a number and then forget what he intended to do after carrying that number. WM is an equally important underlying function for reading, where it enables the child to remember the beginning of a paragraph when she arrives at the end of it. In writing, WM helps children remember what they intend to express in written form while they are performing another task, such as placing a comma or working on spelling a word correctly. WM also enables the linkage between new incoming information in short-term memory with prior knowledge or skills held in longer-term memory.

Initiation refers to the ability to independently begin an activity, a task, or thought process (e.g., problem-solve). Children who present with initiation difficulties often have trouble “getting going” or “getting started.” This can be exhibited behaviorally, such that the child struggles to start on physical activities such as getting out of bed or beginning chores. Cognitively, weaknesses in initiation may manifest as difficulty coming up with ideas or generating plans. In school, children who have poor initiation abilities may be delayed in or unable to start homework assignments or tests. In social situations, initiation challenges may cause a child to have difficulty beginning conversations, calling on friends, or going out to be with friends.

Deficits in “primary” initiation are relatively rare and are often associated with significant neurologic conditions and treatments (e.g., traumatic brain injury, anoxia, effects of radiation treatment in childhood cancer). More often, initiation deficits are secondary to other executive problems (e.g., disorganization) or behavioral (e.g., oppositional/defiant behaviors), developmental (e.g., autism spectrum disorder), or emotional (e.g., depression, anxiety) disorders.

Planning refers to the ability to effectively generate, sequence, and put into motion the steps and procedures necessary to realize a specific goal. In real-world settings, children who struggle with planning are typically described by caregivers and teachers as being inept at independently gathering what is required to solve a problem, or as unable to complete more weighty assignments. Another common complaint is that these children exhibit poor time management skills. Organization is an ability that represents a child's proficiency in arranging, ordering, classifying, and categorizing information. Common daily life challenges associated with organizational difficulties in childhood include problems with gathering and managing materials or items. When children struggle with organization, indirect consequences may include becoming overwhelmed with information and being unable to complete a task or activity. Effective organization is a vital component in learning (more specifically, in memory/retention); many studies along with clinical experience have shown that poor organization significantly impacts how well a child recalls information. Planning and organizing depend on discrimination ability, which refers to the child's ability to determine what is and is not valuable when trying to problem-solve or organize.

Emotional control is the ability to regulate emotions in order to realize goals and direct one's behavior, thoughts, and actions. It has been well established that affective/emotional states have an impact on many aspects of functioning. Conversely, executive function or dysfunction often contributes to modulation or affect. While emotional control is highly interrelated with different EFs (e.g., disinhibition, self-monitoring), separating it conceptually facilitates an appreciation for and recognition of the often-overlooked role that a child's emotional state plays in cognitive and behavioral functioning. Children with weak emotional control may exhibit explosive outbursts, poor temper/anger control, and oversensitivity. Clearly, understanding a child's emotional state is vital to understanding its impact not only on executive functioning, but also on functioning as a whole (e.g., socially, mentally, behaviorally, academically).

Any discussion involving emotional control should also recognize motivation . Motivation/effort may be defined as the reason or reasons one acts or behaves in a certain way. Less motivated children are less likely to engage and utilize all their abilities. Such a disposition not only interferes with application of executive skills, but also results in less than optimal performance and functioning. The less success a child feels, the less likely the child is to put forth effort and to persevere when things become more challenging. If a child's initial efforts are met with a negative reaction, the likelihood that the child will continue putting forth adequate effort diminishes. If left unchecked, a child's overall level of functioning will likely be compromised. More importantly, the child's sense of personal efficacy (e.g., self-esteem) and competence may suffer.

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms and clinical manifestations of neurodevelopmental and executive dysfunction differ with age. Preschool-age children might present with delayed language development, including problems with articulation, vocabulary development, word finding, and rhyming. They often experience early challenges with learning colors, shapes, letters, and numbers; the alphabet; and days of the week. Children with visual processing deficits may have difficulty learning to draw and write and have problems with art activities. These children might also have trouble discriminating between left and right. They might encounter problems recognizing letters and words. Difficulty following instructions, overactivity, and distractibility may be early symptoms of emerging executive dysfunction. Difficulties with fine motor development (e.g., grasping crayons/pencils, coloring, drawing) and social interaction may develop.

School-age children with neurodevelopmental and executive dysfunctions can vary widely in clinical presentations. Their specific patterns of academic performance and behavior represent final common pathways of neurodevelopmental strengths and deficits interacting with environmental, social, or cultural factors; temperament; educational experience; and intrinsic resilience (Table 48.2 ). Children with language weaknesses might have problems integrating and associating letters and sounds, decoding words, deriving meaning, and being able to comprehend passages. Children with early signs of a mathematics weakness might have difficulty with concepts of quantity or with adding or subtracting without using concrete representation (e.g., their fingers when calculating). Difficulty learning time concepts and confusion with directions (right/left) might also be observed. Poor fine motor control and coordination and poor planning can lead to writing problems. Attention and behavioral regulation weaknesses observed earlier can continue, and together with other executive functioning weaknesses (e.g., organization, initiation skills), further complicate the child's ability to acquire and generalize new knowledge. Children with weaknesses in WM may struggle to remember the steps necessary to complete an activity or problem-solve. In social settings, these children often have difficulty keeping up with more complex conversations.

Table 48.2

| ACADEMIC DISORDER | POTENTIAL UNDERLYING NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DYSFUNCTION |

|---|---|

| Reading |

Language Phonologic processing Verbal fluency Syntactic and semantic skills Memory Working memory Sequencing Visual-spatial Attention |

| Written expression, spelling |

Language Phonologic processing Syntactic and semantic skills Graphomotor Visual-spatial Memory Working memory Sequencing Attention |

| Mathematics |

Visual-spatial Memory Working memory Language Sequencing Graphomotor Attention |

* Isolated neurodevelopmental dysfunction can lead to a specific academic disorder, but more often there is a combination of factors underlying weak academic performance. In addition to the dysfunction in neurodevelopmental domains as listed in the table, the clinician must also consider the possibility of limitations of intellectual and cognitive abilities or associated social and emotional problems.

In middle school children the shift in cognitive, academic, and regulatory demands can cause further difficulties for those with existing neurodevelopmental and executive challenges. In reading and writing, middle school children might present with transposition and sequencing errors; might struggle with root words, prefixes, and suffixes; might have difficulty with written expression; and might avoid reading and writing altogether. Challenges completing word problems in math are common. Difficulty with recall of information might also be experienced. Although observable in both lower and more advanced grades, behavioral, emotional, and social difficulties tend to become more salient in middle school children who experience cognitive or academic problems.

High school students can present with deficient reading comprehension, written expression, and slower processing efficiency. Difficulty in answering open-ended questions, dealing with abstract information, and producing executive control (e.g., self-monitoring, organization, planning, self-starting) is often reported.

Academic Problems

Reading disorders (see Chapter 50 ) can stem from any number of neurodevelopmental dysfunctions, as described earlier (see Table 48.2 ). Most often, language and auditory processing weaknesses are present, as evidenced by poor phonologic processing that results in deficiencies at the level of decoding individual words and, consequently, a delay in automaticity (e.g., acquiring a repertoire of words readers can identify instantly) that causes reading to be slow, laborious, and frustrating. Deficits in other core neurodevelopmental domains might also be present. Weak WM might make it difficult for a child to hold sounds and symbols in mind while breaking down words into their component sounds, or might cause reading comprehension problems. Some children experience temporal-ordering weaknesses and struggle with reblending phonemes into correct sequences. Memory dysfunction can cause problems with recall and summarization of what was read. Some children with higher-order cognitive deficiencies have trouble understanding what they read because they lack a strong grasp of the concepts in a text. Although relatively rare as a cause of reading difficulty, problems with visual-spatial functions (e.g., visual perception) can cause children difficulty in recognizing letters. It is not unusual for children with reading problems to avoid reading practice, and a delay in reading proficiency becomes increasingly pronounced and difficult to remediate.

Spelling and writing impairments share many related underlying processing deficits with reading, so it is not surprising that the 2 disorders often occur simultaneously in school-age children (see Table 48.2 ). Core neurodevelopmental weaknesses that underlie spelling difficulties include phonologic and decoding difficulties, orthographic problems (coding letters and words into memory), and morphologic deficits (use of suffixes, prefixes, and root words). Problems in these areas can manifest as phonetically poor, yet visually comparable approximations to the actual word (faght for fight ), spelling that is phonetically correct but visually incorrect (fite for fight ), and inadequate spelling patterns (played as plade). Children with memory disorders might misspell words because of coding weaknesses. Others misspell because of poor auditory WM that interferes with their ability to process letters. Sequencing weaknesses often result in transposition errors when spelling.

Writing difficulties have been classified as disorder of written expression , or dysgraphia (see Table 48.2 ). Although many of the same dysfunctions described for reading and spelling can contribute to problems with writing, written expression is the most complex of the language arts, requiring synthesis of many neurodevelopmental functions (e.g., auditory, visual-spatial, memory, executive; see Chapter 51.2 ). Weaknesses in these functions can result in written output that is difficult to comprehend, disjointed, and poorly organized. The child with WM challenges can lose track of what the child intended to write. Attention deficits can make it difficult for a child to mobilize and sustain the mental effort, pacing, and self-monitoring demands necessary for writing. In many cases, writing is laborious because of an underlying graphomotor dysfunction (e.g., fluency does not keep pace with ideation and language production). Thoughts may also be forgotten or underdeveloped during writing because the mechanical effort is so taxing.

Weaknesses in mathematical ability, known as mathematics disorder or dyscalculia , require early intervention because math involves the assimilation of both procedural knowledge (e.g., calculations) and higher-order cognitive processes (e.g., WM) (see Table 48.2 ). There are many reasons why children experience failure in mathematics (see Chapter 51.1 ). It may be difficult for some to grasp and apply math concepts effectively and systematically; good mathematicians are able to use both verbal and perceptual conceptualization to understand such concepts as fractions, percentages, equations, and proportion. Children with language dysfunctions have difficulty in mathematics because they have trouble understanding their teachers' verbal explanations of quantitative concepts and operations and are likely to experience frustration in solving word problems and in processing the vast network of technical vocabulary in math. Mathematics also relies on visualization. Children who have difficulty forming and recalling visual imagery may be at a disadvantage in acquiring mathematical skills. They might experience problems writing numbers correctly, placing value locations, and processing geometric shapes or fractions. Children with executive dysfunction may be unable to focus on fine detail (e.g., operational signs), might take an impulsive approach to problem solving, engage in little or no self-monitoring, forget components of the problem, or commit careless errors. When a child's memory system is weak, the child might have difficulty recalling appropriate procedures and automatizing mathematical facts (e.g., multiplication tables). Moreover, children with mathematical disabilities can have superimposed mathematics phobias ; anxiety over mathematics can be especially debilitating.

Nonacademic Problems

The impulsivity and lack of effective self-monitoring of children with executive dysfunction can lead to unacceptable actions that were unintentional. Children struggling with neurodevelopmental dysfunction can experience excessive performance anxiety, sadness, or clinical depression; declining self-esteem; and chronic fatigue. Some children lose motivation. They tend to give up and exhibit learned helplessness, a sense that they have no control over their destiny. Therefore they feel no need to exert effort and develop future goals. These children may be easily led toward dysfunctional interpersonal relationships, detrimental behaviors (e.g., delinquency), and the development of mental health disorders, such as mood disorders (see Chapter 39 ) or conduct disorder (Chapter 42 ).

Assessment and Diagnosis

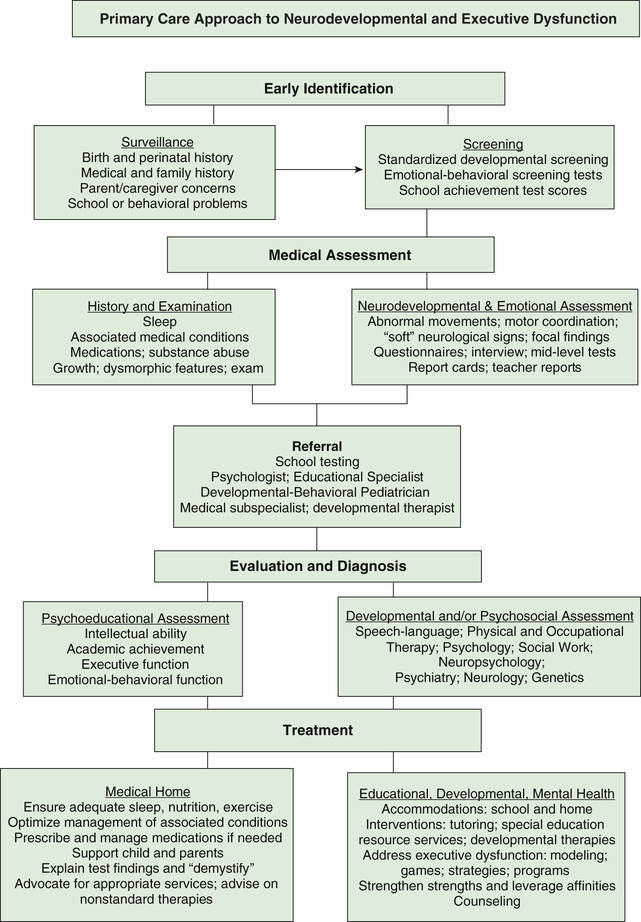

Pediatricians have a critical role in identifying and treating the child with neurodevelopmental or executive dysfunction (Fig. 48.1 ). They have knowledge of the child's medical and family history and social-environmental circumstances and have the benefit of longitudinal contact over the course of routine health visits. Focused surveillance and screening will lead to early identification of developmental-behavioral and preacademic difficulties and interventions to facilitate optimal outcomes.

A family history of a parent who still struggles with reading or time management, or an older sibling who has failed at school, should spur an increased level of monitoring. Risk factors in the medical history, such as extreme prematurity or chronic medical conditions, should likewise be flagged. Children with low birthweight and those born prematurely who appear to have been spared more serious neurologic problems might only manifest academic problems later in their school career. Nonspecific physical complaints or unexpected changes in behavior might be presenting symptoms. Warning signs might be subtle or absent, and parents might have concerns about their child's learning progress but may be reluctant to share these with the pediatrician unless prompted, such as through completion of standardized developmental screening questionnaires or direct questioning regarding possible concerns. There should be a low threshold for initiating further school performance screening and assessment if there are any “red flags.”

Review of school report cards can provide very useful information. In addition to patterns of grades in the various academic skill areas, it is also important to review ratings of classroom behavior and work habits. Group-administered standardized tests provide further information, although interpretation is required because poor scores could result from a learning disorder, ADHD, anxiety, lack of motivation, or some combination. Conversely, a discrepancy between above-average scores on standardized tests and unsatisfactory classroom performance could signal motivation or adjustment issues. Challenges related to homework can provide further insight regarding executive, academic skill, and behavioral factors.

Underlying or associated medical problems should be ruled out. Any suspicion of sensory difficulty should warrant referral for vision or hearing testing . The influence of chronic medical problems or potential side effects of medications should be considered. Sleep deprivation is increasingly being recognized as a contributor to academic problems, especially in middle and high school. Substance abuse must always be a consideration as well, especially in the adolescent previously achieving well who has shown a rapid decline in academic performance.

The physician should be alert for dysmorphic physical features, minor congenital anomalies, or constellations of physical findings (e.g., cardiac and palatal anomalies in velocardiofacial syndrome) and should perform a detailed neurologic examination, including an assessment of fine and gross motor coordination and any involuntary movements or soft neurologic signs. Special investigations (e.g., genetic deletion-duplication microarray, electroencephalogram, MRI) are not always indicated in the absence of specific medical findings or a family history. Measures of brain function, such as functional MRI, offer insight into possible areas of neurodevelopmental dysfunction but remain primarily research tools.

Early signs of executive dysfunction can also be subtle and easily overlooked or misinterpreted. Informal inquiry might include questions about how children complete schoolwork or tasks, how organized or disorganized they are, how much guidance they need, whether they think through problems or respond and react too quickly, what circumstances or individuals affect their ability to employ EFs, how easily they begin tasks and activities, and how well they plan, manage belongings, and control their emotions.

Pediatricians who are interested in performing further assessment before referral, or who are practicing in areas where psychological testing resources are limited, can utilize standardized rating scales and inventories or brief, individually administered tests to narrow potential diagnoses and guide next steps in diagnosis and treatment. Such instruments, completed by the parents, teachers, and the child (if old enough), can provide information about emotions and behavior, patterns of academic performance, and traits associated with specific neurodevelopmental dysfunctions (see Chapter 32 ). Screening instruments such as the Pediatric Symptom Checklist and behavioral questionnaires such as the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (BASC-2) can aid in evaluation. Instruments more specifically focused on academic disorders, such as the Learning Disabilities Diagnostic Inventory, can be completed by the child's teacher to reveal the extent to which skill patterns in a particular area (e.g., reading, writing) are consistent with those of individuals known to have a learning disability.

Executive functions can be further assessed by instruments such as the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function, Second Edition (BRIEF2), which provides a comprehensive measure of real-world behaviors that are closely tied to executive functioning in children age 5-18 yr. An alternative rating inventory of EF in children is the Comprehensive Executive Function Inventory (CEFI). Tests that can be directly administered to gauge intellectual functioning include the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (KBIT-2) and Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edi tion (PPVT 4; assessing receptive vocabulary). A relatively brief test of academic skills is the Wide Range Achievement Test 4 (WRAT4). It should be recognized that these are midlevel tests that can provide descriptive estimates of function but are not diagnostic.

Children who are struggling academically are entitled to evaluations in school. Such assessments are guaranteed in the United States under Public Law 101-476, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) . One increasingly common type of evaluation supported by IDEA is referred to as a response to intervention (RtI) model (see Chapter 51.1 ). In this model, students who are struggling with academic skills are initially provided research-based instruction. If a child does not respond to this instruction, an individualized evaluation by a multidisciplinary team is conducted. Children found to have attentional dysfunction and other disorders might qualify for educational accommodations in the regular classroom under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (504 plan ).

The pediatrician should advise and support parents regarding steps to request evaluations by the school. Multidisciplinary evaluations are focused primarily on determining whether a student meets the eligibility criteria for special education services and to assist in developing an individualized educational plan (IEP) for those eligible for these services. Independent evaluations can provide second opinions outside the school setting. The multidisciplinary team should include a psychologist and preferably an educational diagnostician who can undertake a detailed analysis of academic skills and subskills to pinpoint where breakdowns are occurring in the processes of reading, spelling, writing, and mathematics. Other professionals should become involved, as needed, such as a speech-language pathologist, occupational therapist, and social worker. A mental health specialist can be valuable in identifying family-based issues or psychiatric disorders that may be complicating or aggravating neurodevelopmental dysfunctions.

In some cases, more in-depth examination of a child's neurocognitive status is warranted. This is particularly true for children who present with developmental or cognitive difficulties in the presence of a medical condition (e.g., epilepsy, traumatic brain injury, childhood cancers/brain tumors, genetic conditions). A neuropsychological evaluation involves comprehensive assessment to understand brain functions across domains. Neuropsychological data are often analyzed together with other tests, such as MRI, to look for supporting evidence of any areas of difficulty (e.g., memory weaknesses associated with temporal lobe anomalies). Neuropsychologists can also provide more in-depth evaluation of EFs. Assessment of EFs is typically completed in an examination setting using tools specifically designed to identify any weaknesses in these functions. Although few tools are currently available to assess EF in preschool-age children, the assessment of school-age children is better established. Problems with EFs should be evaluated across measures and in different settings, particularly within the context of the child's daily demands.

Treatment

In addition to addressing any underlying or associated medical problems, the pediatrician can play an important role as a consultant and advocate in overseeing and monitoring the implementation of a comprehensive multidisciplinary management plan for children with neurodevelopmental dysfunctions. Most children require several of the following forms of intervention.

Demystification

Many children with neurodevelopmental dysfunctions have little or no understanding of the nature or sources of their academic difficulties. Once an appropriate descriptive assessment has been performed, it is important to explain to the child the nature of the dysfunction while delineating the child's strengths. This explanation should be provided in nontechnical language, communicating a sense of optimism and a desire to be helpful and supportive.

Bypass Strategies (Accommodations)

Numerous techniques can enable a child to circumvent neurodevelopmental dysfunctions. Such bypass strategies are ordinarily used in the regular classroom. Examples of bypass strategies include using a calculator while solving mathematical problems, writing essays with a word processor, presenting oral instead of written reports, solving fewer mathematical problems, being seated near the teacher to minimize distraction, presenting correctly solved mathematical problems visually, and taking standardized tests untimed. These bypass strategies do not cure neurodevelopmental dysfunctions, but they minimize their academic and nonacademic effects and can provide a scaffold for more successful academic achievement.

Treatment of Neurodevelopmental Dysfunctions

Interventions can be implemented at home and in school to strengthen the weak links in academic skills. Reading specialists, mathematics tutors, and other professionals can use diagnostic data to select techniques that use a student's neurodevelopmental strengths to improve decoding skills, writing ability, or mathematical computation skills. Remediation need not focus exclusively on specific academic areas. Many students need assistance in acquiring study skills, cognitive strategies, and productive organizational habits.

Early identification is critical so that appropriate instructional interventions can be introduced to minimize the long-term effects of academic disorders. Any interventions should be empirically supported (e.g., phonologically based reading intervention has been shown to significantly improve reading skills in school-age children). Remediation may take place in a resource room or learning center at school and is usually limited to children who have met the educational criteria for special education resource services described earlier.

Interventions that can be implemented at home could include drills to aid the automatization of subskills, such as arithmetic facts or letter formations, or the use of phonologically based reading programs.

Treatment of Executive Dysfunction

Interventions to strengthen EFs can be implemented throughout childhood but are most effective if started at a young age. Preschool-age children first experience EFs by way of the modeling, boundaries, and rules observed and put in place by their parents/caregivers, and this modeled behavior must gradually become “internalized” by the child. Early play has been shown to be effective in promoting executive skills in younger children with games such as peek-a-boo (WM); pat-a-cake (WM and IC); follow the leader, Simon says, and “ring around the rosie” (self-control); imitation activities (attention and impulse control); matching and sorting games (organization and attention); and imaginary play (attention, WM, IC, self-monitoring, cognitive flexibility).

In school-age children it is crucial to establish consistent cognitive and behavioral routines that foster and maximize independent, goal-oriented problem solving and performance through mechanisms that include modification of the child's environment, modeling and guidance with the child, and positive reinforcement strategies. Interventions should promote generalization (teaching executive routines in the context of a problem, not as a separate skill) and should move from the external to the internal (from “external support” with active and directive modeling to an “internal process”). An intervention could proceed from external modeling of multistep problem-solving routines and external guidance in developing and implementing everyday routines, to practicing application and use of routines in everyday situations, to a gradual fading of external support and cueing of internal generation and use of executive skills. Such approaches should make the child a part of intervention planning, should avoid labeling, reward effort not outcomes, make interventions positive, and hold the child responsible for his or her efforts. Studies have consistently shown that a combination of medication and behavioral treatments are most effective, although evidence for long term efficacy is lacking. It is important that any treatment plans aimed at bolstering attention and executive functioning also include interventions that address the specific deficits associated with any comorbid diagnoses.

In addition to behavioral approaches, computerized training programs have been shown to strengthen WM skills in children using a computer game model. Generalized and lasting improvements in WM have been reported. Also evidencing positive outcomes are curriculum-based classroom programs , such as the Tools of the Mind (Tools) and Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS). Other promising approaches to EF intervention include aerobic exercise, shown to improve EFs through prefrontal cortex stimulation. Martial arts such as tae kwon do, which stresses discipline and self-regulation, has demonstrated improvements that generalize in many aspects of EFs and attention (e.g., sustained focus). Approaches that use mindfulness techniques are also gaining prominence. Formal parenting interventions have also demonstrated strong evidence for effectiveness. Four programs that have the most empirical support are the Triple P, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), Incredible Years, and New Forest Parenting Programme .

Table 48.3 outlines interventions to target the specific components of EF. Although interventions may target each component separately, success will be determined by how well treatments can be integrated across settings and generalized to other areas of function. Whenever possible, working with more than one EF simultaneously is encouraged as a means of scaffolding intervention and building on previously mastered skills.

Table 48.3

Developmental Therapy

Speech-language pathologists offer intervention for children with various forms of language disability. Occupational therapists focus on sensorimotor skills, including the motor skills of students with writing problems, and physical therapists address gross motor incoordination.

Curriculum Modifications

Many children with neurodevelopmental dysfunctions require alterations in the school curriculum to succeed, especially as they progress through secondary school. Students with memory weaknesses might need to have their courses selected for them so that they do not have an inordinate cumulative memory load in any single semester. The timing of foreign language learning, the selection of a mathematics curriculum, and the choice of science courses are critical issues for many of these struggling adolescents.

Strengthening of Strengths

Affected children need to have their affinities, potentials, and talents identified clearly and exploited widely. It is as important to augment strengths as it is to attempt to remedy deficiencies. Athletic skills, artistic inclinations, creative talents, and mechanical abilities are among the potential assets of certain students who are underachieving academically. Parents and school personnel need to create opportunities for such students to build on these assets and to achieve respect and praise for their efforts. These well-developed personal assets can ultimately have implications for the transition into young adulthood, including career or college selection.

Individual and Family Counseling

When academic difficulties are complicated by family problems or identifiable psychiatric disorders, psychotherapy may be indicated. Mental health professionals may offer long-term or short-term therapy. Such intervention may involve the child alone or the entire family. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is especially effective for mood and anxiety disorders. It is essential that the therapist have a firm understanding of the nature of a child's neurodevelopmental dysfunctions.

Nonstandard Therapies

A variety of treatment methods for neurodevelopmental dysfunctions have been proposed that currently have little to no known scientific evidence of efficacy. This list includes dietary interventions (vitamins, elimination of food additives or potential allergens), neuromotor programs or medications to address vestibular dysfunction, eye exercises, filters, tinted lenses, and various technologic devices. Parents should be cautioned against expending the excessive amounts of time and financial resources usually demanded by these remedies. In many cases, it is difficult to distinguish the nonspecific beneficial effects of increased support and attention paid to the child from the supposed target effects of the intervention.

Medication

Psychopharmacologic agents may be helpful in lessening the toll of some neurodevelopmental dysfunctions. Most often, stimulants are used in the treatment of children with attention deficits. Although most children with attention deficits have other associated dysfunctions, such as language disorders, memory problems, motor weaknesses, or social skill deficits, medications such as methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, and mixed amphetamine salts, as well as nonstimulants such as α2 -adrenergic agonists and atomoxetine , can be important adjuncts to treatment by helping some children focus more selectively and control their impulsivity. When depression or excessive anxiety is a significant component of the clinical picture, antidepressants or anxiolytics may be helpful. Other drugs may improve behavioral control (see Chapter 33 ). Children receiving medication need regular follow-up visits that include a history to check for side effects, a review of current behavioral checklists, a complete physical examination, and appropriate modifications of the medication dose. Periodic trials off medication are recommended to establish whether the medication is still necessary.