Cystic Diseases of the Biliary Tract and Liver

Frederick J. Suchy, Amy G. Feldman

Cystic lesions of liver may be initially recognized during infancy and childhood. Hepatic fibrosis can also occur as part of an associated developmental defect (Table 392.1 ). Cystic renal disease is usually associated and often determines the clinical presentation and prognosis. Virtually all proteins encoded by genes mutated in combined cystic diseases of the liver and kidney are at least partially localized to primary cilia in renal tubular cells and cholangiocytes.

Table 392.1

After Suchy FJ, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF, editors: Liver disease in children, ed 3, New York, 2014, Cambridge University Press, p. 713.

A solitary, congenital liver cyst (nonparasitic) can occur in childhood and has been identified in some cases on prenatal ultrasound. Abdominal distention and pain may be present, and a poorly defined right-upper-quadrant mass may be palpable. These benign lesions are best left undisturbed unless they compress adjacent structures or a complication occurs, such as hemorrhage into the cyst. Operative management is generally reserved for symptomatic patients and enlarging cysts.

Choledochal Cysts

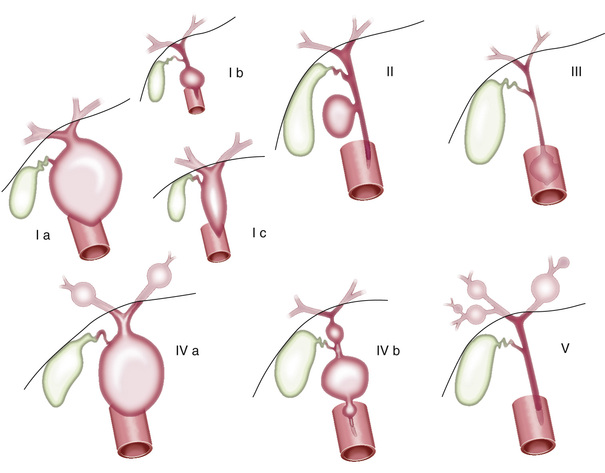

Choledochal cysts are congenital dilatations of the common bile duct that can cause progressive biliary obstruction and biliary cirrhosis. Cylindrical (fusiform) and spherical (saccular) cysts of the extrahepatic ducts are the most common types (see Table 392.1 ). Choledochal cysts are classified according to the Todani method (Fig. 392.1 ). Type 1 choledochal cysts, the most common variant, involve a saccular or fusiform dilation of the common bile duct. Type II cysts are congenital diverticula protruding from the common bile duct. Type III cysts or choledochoceles involve a herniation of the intraduodenal segment of the common bile duct into the duodenum. Type IVa cysts or Caroli disease involve multiple intrahepatic and extrahepatic cysts. Type IVb cysts involve only the extrahepatic duct. Solitary liver cysts (type V) are very rare.

The pathogenesis of choledochal cysts remains uncertain. Some reports suggest that junction of the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct before their entry into the sphincter of Oddi might allow reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the common bile duct, causing inflammation, localized weakness, and dilation of the duct. It has also been proposed that a distal congenital stenotic segment of the biliary tree leads to increased intraluminal pressure and proximal biliary dilation. Other possibilities are that choledochal cysts represent malformations of the common duct or that they occur as part of the spectrum of an infectious disease that includes neonatal hepatitis and biliary atresia.

Approximately 75% of cases appear during childhood. The infant typically presents with cholestatic jaundice; severe liver dysfunction including ascites and coagulopathy can rapidly evolve if biliary obstruction is not relieved. An abdominal mass is rarely palpable. In an older child, the classic triad of abdominal pain, jaundice, and mass occurs in <33% of patients. Features of acute cholangitis (fever, right-upper-quadrant tenderness, jaundice, and leukocytosis) may be present. The diagnosis is made by ultrasonography; choledochal cysts have been identified prenatally using this technique. Magnetic resonance cholangiography is useful in the preoperative assessment of choledochal cyst anatomy.

Choledochal cysts have the potential to develop into cholangiocarcinoma; therefore the treatment of choice is primary excision of the cyst and a Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy. The postoperative course can be complicated by recurrent cholangitis or stricture at the anastomotic site. Long-term follow-up is necessary to ensure that no malignancy develops.

Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) manifests predominantly in childhood (see Chapter 541.2 ). Bilateral enlargement of the kidneys is caused by a generalized dilation of the collecting tubules. The disorder is invariably associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis and various degrees of biliary ductal ectasia, discussed in detail later.

The polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1 (PKHD1) gene, mutated in ARPKD, encodes a protein that is called fibrocystin/polyductin, which is localized to cilia on the apical domain of renal collecting cells and cholangiocytes. The primary defect in ARPKD may be ciliary dysfunction related to the abnormality in this protein. Fibrocystin/polyductin appears to have a role in the regulation of cellular adhesion, repulsion, and proliferation and/or the regulation and maintenance of renal collecting tubules and bile ducts, but its exact role in normal and cystic epithelia remains unknown. Kidney and liver disease are independent and variable in severity; they are not explainable by the type of PKHD1 mutation. Phenotypic variability among affected siblings suggests the importance of modifier genes as well as possibly environmental influences.

In ARPKD, the cysts arise as ectatic expansions of the collecting tubules and bile ducts, which remain in continuity with their structures of origin. ARPKD normally presents in early life, often shortly after birth, and is generally more severe than autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Fetal ultrasound may visualize large echogenic kidneys, also described as bright, with low or absent amniotic fluid (oligohydramnios). However, in many instances the features of ARPKD are not visualized on sonography until the 3rd trimester or after birth.

Patients with ARPKD can die in the perinatal period owing to renal failure or lung dysgenesis. The kidneys in these patients are usually markedly enlarged and dysfunctional. Respiratory failure can result from compression of the chest by grossly enlarged kidneys, from fluid retention, or from concomitant pulmonary hypoplasia. The clinical pathologic findings within a family tend to breed true, although there has been some variability in the severity of the disease and the time for presentation within the same family. In patients surviving infancy because of a milder renal phenotype, liver disease may be a prominent part of the disorder. The liver disease in ARPKD is related to congenital malformation of the liver with varying degrees of periportal fibrosis, bile ductular hyperplasia, ectasia, and dysgenesis. Initial symptoms are liver related in approximately 26% of patients. This can manifest clinically as variable cystic dilation of the intrahepatic biliary tree with congenital hepatic fibrosis. Congenital hepatic fibrosis and Caroli disease likely result from an abnormality in remodeling of the embryonic ductal plate of the liver. Ductal plate malformation refers to the persistence of excess embryonic bile duct structures in the portal tracts. ARPKD patients with recurrent cholangitis or complications of portal hypertension may require combined liver-kidney transplant.

Cystic Dilation of the Intrahepatic Bile Ducts (Caroli Disease/Caroli Syndrome)

In Caroli disease there is isolated ectasia or nonobstructing segmental dilatation of the larger intrahepatic ducts. Caroli syndrome is the more common variant, in which malformations of small bile ducts are associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis. Congenital saccular dilation can affect several segments of the intrahepatic bile ducts; the dilated ducts are lined by cuboidal epithelium and are in continuity with the main duct system, which is usually normal. Choledochal cysts have also been associated with Caroli disease. Bile duct dilation leads to stagnation of bile and formation of biliary sludge and intraductal lithiasis. There is a marked predisposition to ascending cholangitis, which may be exacerbated by calculus formation within the abnormal bile ducts.

Affected patients usually experience symptoms of acute cholangitis as children or young adults. Fever, abdominal pain, mild jaundice, and pruritus occur, and a slightly enlarged, tender liver is palpable. Elevated alkaline phosphatase activity, direct-reacting bilirubin levels, and leukocytosis may be observed during episodes of acute infection. In patients with Caroli disease, clinical features may be the result of a combination of recurring bouts of cholangitis, reflecting the intrahepatic ductal abnormalities and portal hypertensive bleeding resulting from hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasonography shows the dilated intrahepatic ducts, but definitive diagnosis and extent of disease must be determined by percutaneous transhepatic, endoscopic, or magnetic resonance cholangiography.

Cholangitis and sepsis should be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Calculi can require surgery. Partial hepatectomy may be curative in rare cases in which cystic disease is confined to a single lobe. The prognosis is otherwise guarded, largely owing to difficulties in controlling cholangitis and biliary lithiasis and to a significant risk for developing cholangiocarcinoma.

Congenital Hepatic Fibrosis

Congenital hepatic fibrosis is usually associated with ARPKD and is characterized pathologically by diffuse periportal and perilobular fibrosis in broad bands that contain distorted bile duct–like structures and that often compress or incorporate central or sublobular veins (see Table 392.1 ). Irregularly shaped islands of liver parenchyma contain normal-appearing hepatocytes. Caroli disease and choledochal cysts are associated. Most patients have renal disease, mostly autosomal recessive polycystic renal disease and rarely nephronophthisis. Congenital hepatic fibrosis also occurs as part of the COACH syndrome (cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, oligophrenia, congenital ataxia, coloboma, and hepatic fibrosis). Congenital hepatic fibrosis has been described in children with a congenital disorder of glycosylation caused by mutations in the gene encoding phosphomannose isomerase (see Chapter 105.6 ).

Several different forms of congenital hepatic fibrosis have been defined clinically: portal hypertensive (most common) cholangitic, mixed, and latent. The disorder usually has its onset in childhood, with hepatosplenomegaly or with bleeding secondary to portal hypertension. In a recent study, splenomegaly, as a marker for portal hypertension, developed early in life and was present in 60% of children younger than 5 yr of age.

Cholangitis can occur in these patients, as they have abnormal biliary tracts even without Caroli disease. Hepatocellular function is usually well preserved. Serum aminotransferase activities and bilirubin levels are usually normal in the absence of cholangitis and choledocholithiasis; serum alkaline phosphatase activity may be slightly elevated. The serum albumin level and prothrombin time are normal. Liver biopsy is rarely required for diagnosis, particularly in patients with obvious renal disease.

Treatment of this disorder should focus on control of bleeding from esophageal varices and aggressive antibiotic treatment of cholangitis. Infrequent mild bleeding episodes may be managed by endoscopic sclerotherapy or band ligation of the varices. After more severe hemorrhage, portacaval anastomosis can relieve portal hypertension. The prognosis may be greatly improved by a shunting procedure, but survival in some patients may be limited by renal failure.

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

ADPKD (see Chapter 541.3 ), the most commonly inherited cystic kidney disease, affects 1 in 1,000 live births. It is characterized by progressive renal cyst development and cyst enlargement and an array of extrarenal manifestations. There is a high degree of intrafamilial and interfamilial variability in the clinical expression of the disease.

ADPKD is caused by mutation in 1 of 2 genes, PKD1 or PKD2 , which account for 85–90% and 10–15% of cases, respectively. The proteins encoded by these genes, polycystin-1 and polycystin-2, are expressed in renal tubule cells and in cholangiocytes. Polycystin-1 functions as a mechanosensor in cilia, detecting the movement of fluid through tubules and transmitting the signal through polycystin-2, which acts as a calcium channel.

Dilated noncommunicating cysts are most commonly observed. Other hepatic lesions are rarely associated with ADPKD, including the ductal plate malformation, congenital hepatic fibrosis, and biliary microhamartomas (the von Meyenburg complexes). Approximately 50% of patients with renal failure have demonstrable hepatic cysts that are derived from the biliary tract but not in continuity with it. The hepatic cysts increase with age. In one study the prevalence of hepatic cysts was 58% in patients 15-24 yr old. Hepatic cystogenesis appears to be influenced by estrogens. Although the frequency of cysts is similar in males and females, the development of large hepatic cysts is mainly a complication in females. Hepatic cysts are often asymptomatic but can cause pain and are occasionally complicated by hemorrhage, infection, jaundice from bile duct compression, portal hypertension with variceal bleeding, or hepatic venous outflow obstruction from mechanical compression of hepatic veins, resulting in tender hepatomegaly and exudative ascites. Cholangiocarcinoma can occur. Subarachnoid hemorrhage can result from the associated cerebral arterial aneurysms.

Selected patients with severe symptomatic polycystic liver disease and favorable anatomy benefit from liver resection or fenestration. Combined liver-kidney transplantation may be required. There is considerable evidence for a role of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in epithelial proliferation and fluid secretion in experimental renal and hepatic cystic disease. Several clinical trials in adults have shown that somatostatin analogs can blunt hepatic cyst expansion by blocking secretin-induced cyclic adenosine monophosphate generation and fluid secretion by cholangiocytes.

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Liver Disease

Autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease is a distinct clinical and genetic identity in which multiple cysts develop and are unassociated with cystic kidney disease. Liver cysts arise from but are not in continuity with the biliary tract. Girls are more commonly affected than boys, and the cysts often enlarge during pregnancy. Cysts are rarely identified in children. Cyst complications are related to effects of local compression, infection, hemorrhage, or rupture. The genes associated with autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease are PRKCSH and SEC63 , which encode hepatocystin and Sec63, respectively. Hepatocystin is a protein kinase C substrate adK-H, which is involved in the proper folding and maturation of glycoproteins. It has been localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. SEC63 encodes the protein SEC63P, which is a component of the protein translocation machinery in the endoplasmic reticulum.