Anatomic Abnormalities Associated With Hematuria

Congenital Anomalies

Prasad Devarajan

Gross or microscopic hematuria may be associated with many different types of malformations of the urinary tract. The sudden onset of gross hematuria after minor trauma to the flank is often associated with ureteropelvic junction obstruction, cystic kidneys, or enlarged kidneys from any cause (see Chapter 555 ).

Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease

Prasad Devarajan

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) (also known as ARPKD-congenital hepatic fibrosis [CHF]) is an autosomal recessive disorder occurring with an incidence of 1 : 10,000 to 1 : 40,000 and a gene carrier rate in the general population of 1/70. The gene for ARPKD (PKHD1 [polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1]) encodes fibrocystin, a large protein (>4,000 amino acids) with multiple isoforms.

Pathology

Both kidneys are markedly enlarged and grossly show innumerable small cysts throughout the cortex and medulla. Microscopic studies demonstrate dilated, ectatic collecting ducts radiating from the medulla to the cortex. The development of progressive interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy during the advanced stages of the disease eventually leads to renal failure. ARPKD causes dual-organ disease; hence, the term ARPKD/congenital hepatic fibrosis. Liver involvement is characterized by a basic ductal plate abnormality that leads to bile duct proliferation and ectasia, as well as progressive hepatic fibrosis.

Pathogenesis

Fibrocystin may form a multimeric complex with proteins of other primary genetic cystic diseases. It appears that altered intracellular signaling from these complexes, located at epithelial apical cell surfaces, intercellular junctions, and basolateral cell surfaces in association with the focal adhesion complex, is a critical feature of the disease pathophysiology.

Over 300 mutations in PKHD1 (without identified specific hot spots) cause disease, and the same mutation can give variable degrees of disease severity in the same family. This clinical observation is consistent with preclinical data demonstrating many environmental and unknown genetic factors affecting disease expression. The false-negative rate for genetic diagnosis is approximately 10%. Limited available information suggests only a gross genotype–phenotype correlation: mutations that modify fibrocystin appear to cause less-severe disease than those that truncate fibrocystin.

Clinical Manifestations

The diagnosis is often made antenatally by the demonstration of oligohydramnios and bilateral enlarged kidneys on prenatal ultrasound. The typical infant presents with bilateral flank masses during the neonatal period or in early infancy. ARPKD may be associated with respiratory distress and spontaneous pneumothorax in the neonatal period. Perinatal demise (25–30%) appears to be associated with truncating mutations. Components of the oligohydramnios complex (Potter syndrome), including low-set ears, micrognathia, flattened nose, limb-positioning defects, and intrauterine growth restriction, may be present at death from pulmonary hypoplasia. Respiratory distress may also be secondary to large kidneys that compromise the diaphragm function. Hypertension is usually noted within the first few weeks of life, is often severe, and requires aggressive multidrug therapy for control. Oliguria and acute renal failure are uncommon, but transient hyponatremia, often in the presence of acute renal failure, often responds to diuresis. Renal function is usually impaired but may be initially normal in 20–30% of patients. Approximately 50% of patients with a neonatal-perinatal presentation develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD) by age 10 yr.

ARPKD is increasingly recognized in infants (and, rarely, in adolescents and young adults) with a mixed renal-hepatic clinical picture. Such children and young adults often present with predominantly hepatic manifestations in combination with variable degrees of renal disease. Hepatic fibrosis manifests as portal hypertension, hepatosplenomegaly, gastroesophageal varices, episodes of ascending cholangitis, prominent cutaneous periumbilical veins, reversal of portal vein flow, and thrombocytopenia. Congenital hepatic fibrosis may manifest with cholangiodysplastic changes or a frank Caroli type with marked intrahepatic bile duct dilation, affecting the whole liver or just one segment; biliary tract disease increases the risk of ascending cholangitis. Renal findings in patients with a hepatic presentation may range from asymptomatic abnormal renal ultrasonography to systemic hypertension and renal insufficiency. In the newborn, clinical evidence of liver disease by radiologic or clinical laboratory assessment is present in approximately 50% of children and believed to be universal by microscopic evaluation. Natural history studies of ARPKD patients presenting as infants and young children have classified this group in terms of the severity of their dual-organ phenotype: 40% have the severe kidney/severe liver phenotype and 20% each have the severe kidney/mild liver, severe liver/mild kidney, and mild kidney/mild liver phenotype.

Diagnosis

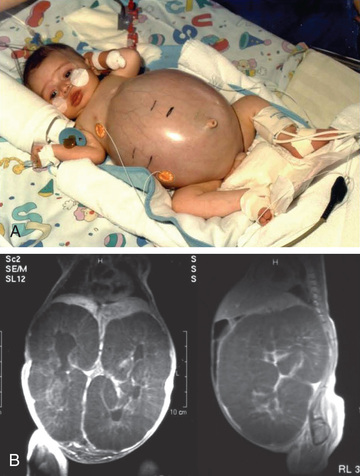

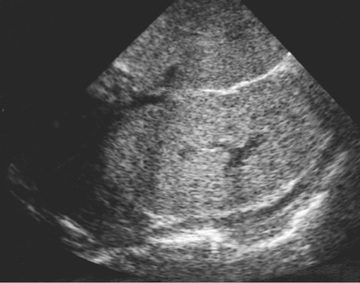

The diagnosis of ARPKD is strongly suggested by bilateral palpable flank masses in an infant with pulmonary hypoplasia, oligohydramnios, and hypertension and the absence of renal cysts by sonography of the parents (Fig. 541.1 ). Markedly enlarged and uniformly hyperechogenic kidneys with poor corticomedullary differentiation are commonly seen on ultrasonography (Fig. 541.2 ). The diagnosis is supported by clinical and laboratory signs of hepatic fibrosis, pathologic findings of ductal plate abnormalities seen on liver biopsy, anatomic and pathologic proof of ARPKD in a sibling, or parental consanguinity. The diagnosis can be confirmed by genetic testing. The differential diagnosis includes other causes of bilateral renal enlargement and/or cysts, such as multicystic dysplasia, hydronephrosis, Wilms tumor, and bilateral renal vein thrombosis (Tables 541.1 and 541.2 ).

Table 541.1

Comparison of Clinical Features of Cystic Kidney Diseases

| DISEASE | INHERITANCE | FREQUENCY | GENE PRODUCT | AGE OF ONSET | CYST ORIGIN | RENOMEGALY | CAUSE OF ESRD | OTHER MANIFESTATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADPKD | AD | 1:400-1,000 |

PKD1 PKD2 |

20s and 30s; <2% before age 15 Occasional perinatal onset |

Anywhere (including the Bowman capsule) | Yes | Yes | Liver cysts |

| Cerebral aneurysms | ||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Mitral valve prolapse | ||||||||

| Kidney stones | ||||||||

| UTIs | ||||||||

| ARPKD | AR | 1:6,000-10,000 | PKHD1 | First year of life; perinatal onset | Distal nephron, CD | Yes | Yes | Hepatic fibrosis |

| Pulmonary hypoplasia | ||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| ACKD | No | 90% of ESRD patients at 8 yr | None | Years after onset of ESRD | Proximal and distal tubules | Rarely | No | None |

| Simple cysts | No | 50% in those older than 40 yr | None | Adulthood | Anywhere (usually cortical) | No | No | None |

| Nephronophthisis | AR | 1:80,000 | Nephrocystins (NPHP1-9) | Childhood or adolescence | Medullary DCT | No | Yes | Retinal degeneration; neurologic, skeletal, hepatic, cardiac malformations |

| MCKD | AD | Rare | Uromodulin, others | Adulthood | Medullary DCT | No | Yes | Hyperuricemia, gout |

| MSK | No | 1:5,000-20,000 | None | 30s | Medullary CD | No | No | Kidney stones |

| Hypercalciuria | ||||||||

| Tuberous sclerosis | AD | 1:10,000 |

Hamartin (TSC1) Tuberin (TSC2) |

Childhood | Loop of Henle, DCT | Rarely | Rarely | Renal cell carcinoma |

| Tubers, seizures | ||||||||

| Angiomyolipoma | ||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| VHL syndrome | AD | 1:40,000 | VHL protein | 20s | Cortical nephrons | Rarely | Rarely | Retinal angioma, CNS hemangioblastoma, renal cell carcinoma, pheochromocytoma |

| Oral-facial-digital syndrome | XD | 1:250,000 | OFD1 protein | Childhood or adulthood | Renal glomeruli | Rarely | Yes | Malformation of the face, oral cavity, and digits; liver cysts; mental retardation |

| Bardet-Biedl syndrome | AR | 1:65,000-160,000 | BBS 14 | Adulthood | Renal calyces | Rarely | Yes | Syndactyly and polydactyly, obesity, retinal dystrophy, male hypogenitalism, hypertension, intellectual disability |

ACKD, acquired cystic kidney disease; AD, autosomal dominant; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; AR, autosomal recessive; ARPKD, autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease; CD, collecting duct; CNS, central nervous system; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; MCKD, medullary cystic kidney disease; MSK, medullary sponge kidney; UTI, urinary tract infection; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau; XD, X-linked dominant.

From Arnaout MA: Cystic kidney disease. In Goldman L, Schafer AI (eds): Goldman's Cecil medicine, 24/e, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders, Table 129-1.

Table 541.2

Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease and Hepatorenal Fibrocystic Disease Phenocopies

| DISEASE | GENE(S) | RENAL DISEASE | HEPATIC DISEASE | SYSTEMIC FEATURES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARPKD | PKHD1 | Collecting duct dilation | CHF; Caroli disease | No |

| ADPKD | PKD1; PKD2 | Cysts along entire nephron | Biliary cysts; CHF (rare) | Yes: adults |

| NPHP | NPHP1-NPHP16 | Cysts at the corticomedullary junction | CHF | +/− |

| Joubert syndrome and related disorders | JBTS1-JBTS20 | Cystic dysplasia; NPHP | CHF; Caroli disease | Yes |

| Bardet-Biedl syndrome | BBS1-BBS18 | Cystic dysplasia; NPHP | CHF | Yes |

| Meckel-Gruber syndrome | MKS1-MKS10 | Cystic dysplasia | CHF | Yes |

| Oral-facial-digital syndrome, type I | OFD1 | Glomerular cysts | CHF (rare) | Yes |

| Glomerulocystic disease | PKD1; HNF1B; UMOD | Enlarged; normal or hypoplastic kidneys | CHF (with PKD1 mutations) | +/− |

| Jeune syndrome (asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy) | IFT80 (ATD2) DYNC2H1 (ADT3) ADT1, ADT4, ADT5 | Cystic dysplasia | CHF; Caroli disease | Yes |

| Renal-hepatic-pancreatic dysplasia (Ivemark II) | NPHP3, NEK8 | Cystic dysplasia | Intrahepatic biliary dysgenesis | Yes |

| Zellweger syndrome | PEX1-3;5-6;10-11;13;14;16;19;26 | Renal cortical microcysts | Intrahepatic biliary dysgenesis | Yes |

CHF, congenital hepatic fibrosis; NPHP, nephronophthisis.

Modified from Guay-Woodford LM, Bissler JJ, Braun MC, et al: Consensus expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: report of an international conference, J Pediatr 165:611-617, 2014.

Nephronophthisis, an autosomal recessive disorder with renal fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and cyst formation, is a common cause of ESRD in children and adolescents (see Tables 541.1 and 541.2 ) (see also Chapter 539 ). Associated external findings include retinal degeneration (Senior-Loken syndrome), cerebellar ataxia (Joubert syndrome), and hepatic fibrosis (Boichis disease). Symptoms include polyuria (salt wasting, poor concentrating ability), failure to thrive, and anemia. Hypertension and edema are seen later when ESRD develops. Prenatal diagnostic testing using genetic linkage analysis or direct mutation analysis is available in families with a previously affected child.

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis with in vitro fertilization may avoid the birth of another affected child with ARPKD.

Treatment

The treatment of ARPKD is supportive. Aggressive ventilatory support is often necessary in the neonatal period secondary to pulmonary hypoplasia, hypoventilation, and the respiratory illnesses of prematurity. Careful management of hypertension (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and other antihypertensive medications as needed), fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, osteopenia, and clinical manifestations of renal insufficiency are essential. Children with severe respiratory failure or feeding intolerance from enlarged kidneys can require unilateral or, more commonly, bilateral nephrectomies, prompting the need for renal replacement therapy. For many children approaching ESRD therapy, significant portal hypertension is present. This in combination with the dramatic improvement in liver transplantation survival has led to consideration of dual renal and hepatic transplantation in a carefully selected group of patients. Dual transplantation thus avoids the later development of end-stage liver disease despite successful renal transplantation.

Prognosis

Mortality rates have improved dramatically, although approximately 30% of patients die in the neonatal period from complications of pulmonary hypoplasia. Neonatal respiratory support and renal replacement therapies have increased the 10-yr survival of children surviving beyond the first year of life to > 80%. The fifteen-year survival rate is currently estimated at 70–80%. Consideration of dual renal and hepatic transplantation and the development of disease-specific therapies for pediatric clinical trials will further positively impact the natural history of ARPKD. An important resource for families of patients is the ARPKD/CHF Alliance ( www.arpkdchf.org ).

Bibliography

Bergman C. ARPKD and early manifestations of ADPKD: the original polycystic kidney disease and phenocopies. Pediatr Nephrol . 2015;30:15–30.

Cramer MT, Guay-Woodford LM. Cystic kidney disease: a primer. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis . 2015;22(4):297–305.

Dell KM, Avner ED. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease . [In Gene Clinics: Clinical Genetic Information Resource (database online ); Available from:] http://www.geneclinics.org/ [last revised 2011].

Guay-Woodford LM, Bissler JJ, Braun MC, et al. Consensus expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: report of an international conference. J Pediatr . 2014;165:611–617.

Hartung EA, Guay-Woodford LM. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: a hepatorenal fibrocystic disorder with pleiotropic effects. Pediatrics . 2014;134:e833–e845.

Hoyer PF. Clinical manifestations of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2015;27(2):186–192.

Sweeney WE Jr, Avner ED. Emerging therapies for childhood polycystic kidney disease. Front Pediatr . 2017;5:77.

Telega G, Cronin D, Avner ED. New approaches to the ARPKD patient with dual kidney-liver complications. Pediatr Transplant . 2013;17:328–335.

Wehrman A, Kriegermeier A, Wen J. Diagnosis and management of hepatobiliary complications in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Front Pediatr . 2017;5:124.

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

Prasad Devarajan

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), also known as adult-onset polycystic kidney disease, is the most common hereditary human kidney disease, with an incidence of 1/400 to 1/1,000. It is a systemic disorder with possible cyst formation in multiple organs (liver, pancreas, spleen, brain) and the development of saccular cerebral aneurysms.

Pathology

Both kidneys are enlarged and show large cortical and medullary cysts originating from all regions of the nephron.

Pathogenesis

Approximately 85% of patients with ADPKD have mutations that map to the PKD1 gene on the short arm of chromosome 16, which encodes polycystin, a transmembrane glycoprotein. Another 10–15% of ADPKD mutations map to the PKD2 gene on the long arm of chromosome 4, which encodes polycystin 2, a proposed nonselective cation channel. The majority of mutations appear to be unique to a given family. At present, a mutation can be found in 85% of patients with well-characterized disease. Approximately 8–10% of patients will have de novo, disease-causing mutations. Mutations of PKD1 are associated with more severe renal disease than mutations of PKD2 . The pathophysiology of the disease appears to be related to the disruption of normal multimeric cystoprotein complexes, with consequent abnormal intracellular signaling resulting in abnormal proliferation, tubular secretion, and cyst formation. Abnormal growth factor expression, coupled with low intracellular calcium and elevated cyclic adenosine monophosphate, appear to be important features leading to formation of cysts and progressive enlargement. Mutations in GANAB have been reported in PKD1- and PKD2- negative patients.

Clinical Presentation

The severity of renal disease and the clinical manifestations of ADPKD are highly variable. Symptomatic ADPKD most commonly occurs in the fourth or fifth decade of life. However, symptoms, including gross or microscopic hematuria, bilateral flank pain, abdominal masses, hypertension, and urinary tract infection, may be seen in neonates, children, and adolescents. With the increased utilization of abdominal sonography in the pediatric population, as well as ADPKD families requesting possible screening in their asymptomatic, at-risk offspring (with the passage of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act in the United States), most children with ADPKD are diagnosed by abnormal renal sonography in the absence of symptoms. Renal ultrasonography usually demonstrates multiple bilateral macrocysts in enlarged kidneys (Fig. 541.3 ), although normal kidney size and unilateral disease may be seen in the early phase of the disease in children.

ADPKD is a multiorgan disorder affecting many tissue types. Cysts may be asymptomatic but present within the liver, pancreas, spleen, and ovaries and when present help confirm the diagnosis in childhood. Intracranial aneurysms, which appear to segregate within certain families, have an overall prevalence of 15% and are an important cause of mortality in adults, but occasionally occur in children. Mitral valve prolapse is seen in approximately 12% of children; aortic and coronary artery aneurysms and aortic valve insufficiency are noted in affected adults. Hernias, bronchiectasis, and intestinal diverticula can also occur in these children.

Diagnosis

ADPKD is confirmed by the presence of enlarged kidneys with bilateral macrocysts in a patient with an affected first-degree relative. De novo mutations occur in 8–10% of patients with newly diagnosed disease. The diagnosis might be made in children before their affected parent, making parental renal sonography an important diagnostic test to be performed in families with no apparent family history. Among patients with genetically defined ADPKD, screening renal ultrasonography results may be normal in ≤ 20% by 20 yr of age and < 5% by 30 yr of age.

Prenatal diagnosis is suggested from the presence of enlarged kidneys with or without cysts on ultrasonography in families with known ADPKD. Prenatal DNA testing is available in families with affected members whose disease is caused by identified mutations in the PKD1 or PKD2 genes.

The differential diagnosis includes renal cysts associated with glomerulocystic kidney disease, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau disease, which may be inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (see Table 541.1 ). The neonatal manifestations of ADPKD and ARPKD may rarely be indistinguishable.

Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment of ADPKD is primarily supportive. Control of blood pressure is critical because the rate of disease progression in ADPKD correlates with the presence of hypertension. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor antagonists are agents of choice. Obesity, dietary salt and protein excess, caffeine ingestion, smoking, multiple pregnancies, and male gender appear to accelerate the disease progression. Older patients with a family history of intracranial aneurysm rupture should be screened for cerebral aneurysms.

Although neonatal ADPKD may be fatal, long-term survival of the patient and the kidneys is possible for children surviving the neonatal period. ADPKD that occurs initially in older children has a favorable prognosis, with normal renal function during childhood seen in > 80% of children. Pain may be a manifestation of infection, hemorrhage, cyst rupture, stones, or tumors and should be managed appropriately with pain medications and specifically based on its etiology.

Although disease-specific therapy is not yet available, clinical trials are in progress based on promising preclinical laboratory investigations. These potential therapies include renin–angiotensin blockade, vasopressin V2 receptor antagonism (tolvaptan), and somatostatin analogues. A valuable resource for patients and their families is the Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation (www.pkdcure.org ).

Bibliography

Beck L, Bombeck AS, Choi MJ, et al. KDOQI vs commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis . 2013;63:403–441.

Cadnapaphornchai MA. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in children. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2015;27:193–200.

Cadnapaphornchai MA. Clinical trials in pediatric autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Front Pediatr . 2017;5:53.

Mao Z, Chong J, Ong AC. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: recent advances in clinical management. F1000Res . 2016;5:2029.

Ong AC, Devuyst O, Knebelmann B, et al. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the changing face of clinical management. Lancet . 2015;385(9981):1993–2002.

Ong ACM. Making sense of polycystic kidney disease. Lancet . 2017;389:1780–1782.

Reddy BV, Chapman AB. The spectrum of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in children and adolescents. Pediatr Nephrol . 2017;32(1):31–42.

Simms RJ. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. BMJ . 2016;352:i679.

Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, et al. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med . 2012;267(25):2407–2418.

Trauma

Prasad Devarajan

Infants and children are more susceptible to renal injury following blunt or penetrating injury to the back or abdomen because of their decreased muscle mass “protecting” the kidney. Gross or microscopic hematuria, flank pain, and abdominal rigidity can occur; associated injuries may be present (see Chapter 82 ). In the absence of hemodynamic instability, most renal trauma can be managed nonoperatively. Urethral trauma can result from crush injury, often associated with a fractured pelvis or from direct injury. Such injury is suspected in the appropriate clinical setting when gross blood appears at the external urethral meatus. Rhabdomyolysis and consequent renal failure is another complication of crush injury that can be ameliorated by vigorous fluid resuscitation. There may be a relationship between microscopic hematuria and recreational accidents in individuals > 16 yr of age, none of whom exhibited hypotension or required surgical intervention.

Bibliography

Chouhan JD, Winer AG, Johnson C, et al. Contemporary evaluation and management of renal trauma. Can J Urol . 2016;23(2):8191–8197.

Dane B, Baxter AB, Bernstein MP. Imaging genitourinary trauma. Radiol Clin North Am . 2017;55(2):321–335.

LeeVan E, Zmora O, Cazzulino F, et al. Management of pediatric blunt renal trauma: a systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg . 2016;80(3):519–528.

Lloyd GL, Slade S, McWilliams KL, et al. Renal trauma from recreational accidents manifests different injury patterns than urban renal trauma. J Urol . 2012;188:163–168.