Sinusitis

Diane E. Pappas, J. Owen Hendley †

Sinusitis is a common illness of childhood and adolescence. There are 2 common types of acute sinusitis—viral and bacterial—with significant acute and chronic morbidity as well as the potential for serious complications. Fungal sinusitis is rare in immunocompetent patients but can also occur. The common cold produces a viral, self-limited rhinosinusitis (see Chapter 407 ). Approximately 0.5–2% of viral upper respiratory tract infections in children and adolescents are complicated by acute symptomatic bacterial sinusitis. Some children with underlying predisposing conditions have chronic sinus disease that does not appear to be infectious. The means for appropriate diagnosis and optimal treatment of sinusitis remain controversial.

Typically, the ethmoidal and maxillary sinuses are present at birth, but only the ethmoidal sinuses are pneumatized. The maxillary sinuses are not pneumatized until 4 yr of age. The sphenoidal sinuses are present by 5 yr of age, whereas the frontal sinuses begin development at age 7-8 yr and are not completely developed until adolescence. The ostia draining the sinuses are narrow (1-3 mm) and drain into the ostiomeatal complex in the middle meatus. The paranasal sinuses are normally sterile, maintained by the mucociliary clearance system.

Etiology

The bacterial pathogens causing acute bacterial sinusitis in children and adolescents include Streptococcus pneumoniae (~30%; see Chapter 209 ), nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (~30%; see Chapter 221 ), and Moraxella catarrhalis (~10%; see Chapter 223 ). Approximately 50% of H. influenzae and 100% of M. catarrhalis are β-lactamase positive. Approximately 25% of S. pneumoniae may be penicillin resistant. Staphylococcus aureus, other streptococci, and anaerobes are uncommon causes of acute bacterial sinusitis in children. Although S. aureus (see Chapter 208.1 ) is an uncommon pathogen for acute sinusitis in children, the increasing prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus is a significant concern. H. influenzae , α- and β-hemolytic streptococci, M. catarrhalis , S. pneumoniae , and coagulase-negative staphylococci are commonly recovered from children with chronic sinus disease.

Epidemiology

Acute bacterial sinusitis can occur at any age. Predisposing conditions include viral upper respiratory tract infections (associated with out-of-home daycare or a school-age sibling), allergic rhinitis, and tobacco smoke exposure. Children with immune deficiencies, particularly of antibody production (immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgG subclasses, IgA; see Chapter 150 ), cystic fibrosis (see Chapter 432 ), ciliary dysfunction (see Chapter 433 ), abnormalities of phagocyte function, gastroesophageal reflux, anatomic defects (cleft palate), nasal polyps, cocaine abuse, and nasal foreign bodies (including nasogastric tubes), can develop chronic or recurrent sinus disease. Immunosuppression for bone marrow transplantation or malignancy with profound neutropenia and lymphopenia predisposes to severe fungal (aspergillus, mucor) sinusitis, often with intracranial extension. Patients with nasotracheal intubation or nasogastric tubes may have obstruction of the sinus ostia and develop sinusitis with the multiple-drug resistant organisms of the intensive care unit.

Acute sinusitis is defined by a duration of <30 days, subacute by a duration of 1-3 mo, and chronic by a duration of longer than 3 mo.

Pathogenesis

Acute bacterial sinusitis typically follows a viral upper respiratory tract infection. Initially, the viral infection produces a viral rhinosinusitis; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation of the paranasal sinuses demonstrates abnormalities (mucosal thickening, edema, inflammation) of the paranasal sinuses in 68% of healthy children in the normal course of the common cold. Nose blowing has been demonstrated to generate sufficient force to propel nasal secretions into the sinus cavities. Bacteria from the nasopharynx that enter the sinuses are normally cleared readily, but during viral rhinosinusitis, inflammation and edema can block sinus drainage and impair mucociliary clearance of bacteria. The growth conditions are favorable, and high titers of bacteria are produced.

Clinical Manifestations

Children and adolescents with sinusitis can present with nonspecific complaints, including nasal congestion, purulent nasal discharge (unilateral or bilateral), fever, and cough. Less-common symptoms include bad breath (halitosis), a decreased sense of smell (hyposmia), and periorbital edema (Table 408.1 ). Complaints of headache and facial pain are rare in children. Additional symptoms include maxillary tooth discomfort and pain or pressure exacerbated by bending forward. Physical examination might reveal erythema and swelling of the nasal mucosa with purulent nasal discharge. Sinus tenderness may be detectable in adolescents and adults. Transillumination reveals an opaque sinus that transmits light poorly.

Table 408.1

Conventional Criteria for the Diagnosis of Sinusitis Based on the Presence of at Least 2 Major or 1 Major and ≥2 Minor Symptoms

| MAJOR SYMPTOMS | MINOR SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|

From Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al: IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. CID 54:e72–e112, 2012, Table 2, p. e78.

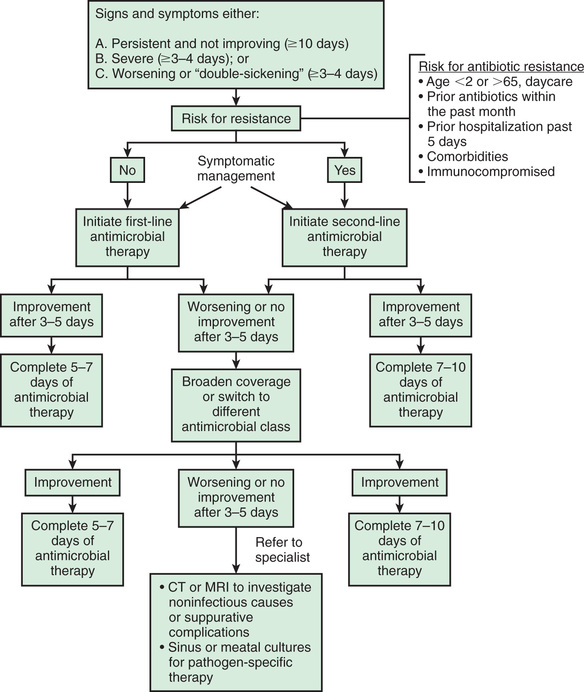

Differentiating bacterial sinusitis from a cold may be difficult, but certain patterns suggestive of sinusitis have been identified. These include persistence of nasal congestion, rhinorrhea (of any quality), and daytime cough ≥10 days without improvement; severe symptoms of temperature ≥39°C (102°F) with purulent nasal discharge for 3 days or longer; and worsening symptoms either by recurrence of symptoms after an initial improvement or new symptoms of fever, nasal discharge, and daytime cough (double sickening; Fig. 408.1 ).

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of acute bacterial sinusitis is based on history. Persistent symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection, including nasal discharge and cough, for longer than 10 days without improvement, or severe respiratory symptoms, including temperature of at least 39°C (102°F) and purulent nasal discharge for 3-4 consecutive days, suggest a complicating acute bacterial sinusitis. Bacteria are recovered from maxillary sinus aspirates in 70% of children with such persistent or severe symptoms studied. Children with chronic sinusitis have a history of persistent respiratory symptoms, including cough, nasal discharge, or nasal congestion, lasting longer than 90 days.

Sinus aspirate culture is the only accurate method of diagnosis but is not practical for routine use for immunocompetent patients. It may be a necessary procedure for immunosuppressed patients with suspected fungal sinusitis. In adults, rigid nasal endoscopy is a less-invasive method for obtaining culture material from the sinus but detects a great excess of positive cultures compared with aspirates. Findings on radiographic studies (sinus plain films, computed tomography [CT] scans), including opacification, mucosal thickening, or presence of an air-fluid level, are not diagnostic and are not recommended in otherwise healthy children. Such findings can confirm the presence of sinus inflammation but cannot be used to differentiate among viral, bacterial, or allergic causes of inflammation.

Given the nonspecific clinical picture, differential diagnostic considerations include viral upper respiratory tract infection, allergic rhinitis, nonallergic rhinitis, and nasal foreign body. Viral upper respiratory tract infections are characterized by clear and usually nonpurulent nasal discharge, cough, and initial fever; symptoms do not usually persist beyond 10-14 days, although a few children (10%) have persistent symptoms even at 14 days. In a recent study using nasal sampling, new viruses were present in 29% of sinusitis episodes in children, suggesting sequential URIs as the cause of persistent symptoms in many cases. Allergic rhinitis can be seasonal; evaluation of nasal secretions should reveal significant eosinophilia.

Treatment

It is unclear whether antimicrobial treatment of clinically diagnosed acute bacterial sinusitis offers any substantial benefit. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing 14-day treatment of children with clinically diagnosed sinusitis with amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or placebo found that antimicrobial therapy did not affect resolution of symptoms, duration of symptoms, or days missed from school. A similar study in adults demonstrated improved symptoms at day 7 but not day 10 of treatment. Major guidelines recommend antimicrobial treatment for acute bacterial sinusitis with severe onset or a worsening course to promote resolution of symptoms and prevent suppurative complications, although 50–60% of children with acute bacterial sinusitis may recover without antimicrobial therapy.

Initial therapy with amoxicillin (45 mg/kg/day divided bid) is adequate for most children with uncomplicated mild to moderate severity acute bacterial sinusitis (Table 408.2 ). Alternative treatments for the penicillin-allergic patient include cefdinir, cefuroxime axetil, cefpodoxime, or cefixime. In older children, levofloxacin is an alternative antibiotic. Azithromycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are no longer indicated because of a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance. For children with risk factors (antibiotic treatment in the preceding 1-3 mo, daycare attendance, or age younger than 2 yr) for the presence of resistant bacterial species, and for children who fail to respond to initial therapy with amoxicillin within 72 hr, or with severe sinusitis, treatment with high-dose amoxicillin-clavulanate (80-90 mg/kg/day of amoxicillin) should be initiated. Ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg, IV or IM) may be given to children who are vomiting or who are at risk for poor compliance; it should be followed by a course of oral antibiotics. Failure to respond to these regimens necessitates referral to an otolaryngologist for further evaluation because maxillary sinus aspiration for culture and susceptibility testing may be necessary (Table 408.3 ). The appropriate duration of therapy for sinusitis has yet to be determined; individualization of therapy is a reasonable approach, with treatment recommended for a minimum of 10 days or 7 days after resolution of symptoms (see Fig. 408.1 ).

Table 408.2

Antimicrobial Regimens for Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis in Children

| INDICATION | FIRST-LINE (DAILY DOSE) | SECOND-LINE (DAILY DOSE) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial empirical therapy | Amoxicillin-clavulanate (45 mg/kg/day PO bid) | |

| β-Lactam allergy | ||

| Type I hypersensitivity | ||

| Non-type I hypersensitivity |

• Clindamycin* (30-40 mg/kg/day PO tid) plus cefixime (8 mg/kg/day PO bid) or cefpodoxime (10 mg/kg/day PO bid) |

|

| Risk for antibiotic resistance or failed initial therapy | ||

|

• Clindamycin* (30-40 mg/kg/day PO tid) plus cefixime (8 mg/kg/day PO bid) or cefpodoxime (10 mg/kg/day PO bid) |

||

| Severe infection requiring hospitalization | ||

* Resistance to clindamycin (~31%) is found frequently among Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19A isolates in different regions of the United States.

bid, 2 times daily; IV, intravenously; PO, orally; qd, daily; tid, 3 times a day.

From Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al: IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. CID 54:e72–e112, 2012, Table 9, p. e94.

Table 408.3

Indications for Referral to a Specialist

From Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al: IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. CID 54:e72–e112, 2012, Table 14, p. e106.

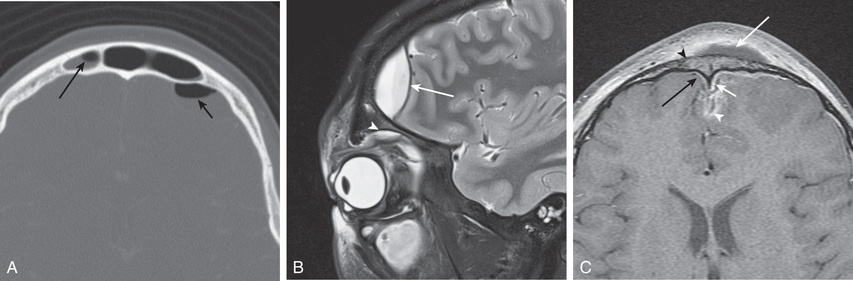

Frontal sinusitis can rapidly progress to serious intracranial complications and necessitates initiation of parenteral ceftriaxone until substantial clinical improvement is achieved (Figs. 408.2 and 408.3 ). Treatment is then completed with oral antibiotic therapy.

The use of decongestants, antihistamines, mucolytics, and intranasal corticosteroids has not been adequately studied in children and is not recommended for the treatment of acute uncomplicated bacterial sinusitis. Likewise, saline nasal washes or nasal sprays can help liquefy secretions and act as a mild vasoconstrictor, but the effects have not been systematically evaluated in children.

Complications

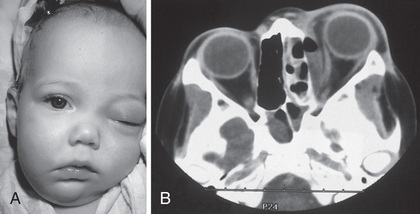

Because of the close proximity of the paranasal sinuses to the brain and eyes, serious orbital and/or intracranial complications can result from acute bacterial sinusitis and progress rapidly. Orbital complications, including periorbital cellulitis and more often orbital cellulitis (see Chapter 634 ), are most often secondary to acute bacterial ethmoiditis. Infection can spread directly through the lamina papyracea, the thin bone that forms the lateral wall of the ethmoidal sinus. Periorbital cellulitis produces erythema and swelling of the tissues surrounding the globe, whereas orbital cellulitis involves the intraorbital structures and produces proptosis, chemosis, decreased visual acuity, double vision and impaired extraocular movements, and eye pain (Fig. 408.4 ). Evaluation should include CT scan of the orbits and sinuses with ophthalmology and otolaryngology consultations. Treatment with intravenous antibiotics should be initiated. Orbital cellulitis may require surgical drainage of the ethmoidal sinuses or orbit.

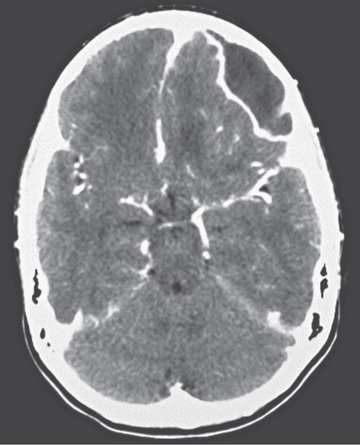

Intracranial complications can include epidural abscess, meningitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, subdural empyema, and brain abscess (see Chapter 622 ). Children with altered mental status, nuchal rigidity, severe headache, focal neurologic findings, or signs of increased intracranial pressure (headache, vomiting) require immediate CT scan of the brain, orbits, and sinuses to evaluate for the presence of intracranial complications of acute bacterial sinusitis. Black children and males are at increased risk, but there is no evidence of increased risk due to socioeconomic status. Treatment with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (usually cefotaxime or ceftriaxone combined with vancomycin) should be initiated immediately, pending culture and susceptibility results. In 50% the abscess is a polymicrobial infection. Abscesses can require surgical drainage. Other complications include osteomyelitis of the frontal bone (Pott puffy tumor ), which is characterized by edema and swelling of the forehead (see Fig. 408.2 ), and mucoceles , which are chronic inflammatory lesions commonly located in the frontal sinuses that can expand, causing displacement of the eye with resultant diplopia. Surgical drainage is usually required.

Prevention

Prevention is best accomplished by frequent handwashing and avoiding persons with colds. Because acute bacterial sinusitis can complicate influenza infection, prevention of influenza infection by yearly influenza vaccine will prevent some cases of complicating sinusitis. Immunization or chemoprophylaxis against influenza with oseltamivir or zanamivir may be useful for prevention of colds caused by this pathogen and the associated complications; influenza is responsible for only a small proportion of all colds.