Congenital Anomalies of the Larynx, Trachea, and Bronchi

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

The larynx functions as a breathing passage, a valve to protect the lungs, and the primary organ of communication; symptoms of laryngeal anomalies are those of airway obstruction, noisy breathing, difficulty feeding, and abnormalities of phonation (see Chapter 400 ). Obstructive congenital lesions of the upper airway produce turbulent airflow according to the laws of fluid dynamics. This rapid, turbulent airflow across a narrowed segment of respiratory tract produces distinctive sounds that are diagnostically useful. The location of the obstruction produces characteristic changes in the sound of inspiration and/or expiration. Intrathoracic lesions typically cause expiratory wheezing and stridor, often masquerading as asthma. The expiratory wheezing contrasts to the inspiratory stridor caused by the extrathoracic lesions of congenital laryngeal anomalies, specifically laryngomalacia and bilateral vocal cord paralysis. Stertor describes the low-pitched inspiratory snoring sound typically produced by nasal or nasopharyngeal obstruction.

The timing of noisy breathing in relation to the sleep–wake cycle is important. Obstruction of the pharyngeal airway (by enlarged tonsils, adenoids, tongue, or syndromes with midface hypoplasia) typically produces worse obstruction during sleep than during waking. Obstruction that is worse when awake is typically laryngeal, tracheal, or bronchial and is exacerbated by exertion. The location of the obstruction dictates the respiratory phase, tone, and nature of the sound, and these qualities direct the differential diagnosis.

With airway obstruction, the severity of the obstructing lesion, the work of breathing, determines the necessity for diagnostic procedures and surgical intervention. Obstructive symptoms vary from mild to severe stridor with episodes of apnea, cyanosis, suprasternal (tracheal tugging) and subcostal retractions, dyspnea, and tachypnea. Congenital anomalies of the trachea and bronchi can create serious respiratory difficulties from the 1st min of life and may sometimes be diagnosed in the prenatal period. If a severe obstruction is suspected prenatally, an airway birth plan should be developed by a high-risk maternal fetal medicine expert, a neonatologist, and a pediatric airway surgeon. Congenital high airway obstruction syndrome, or CHAOS , can lead to immediate postnatal distress. Chronic obstruction can cause failure to thrive and chronic hypoxemia and may have long-term effects on growth and development.

Laryngomalacia

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

Clinical Manifestations

Laryngomalacia accounts for 45% to 75% of congenital laryngeal anomalies in children with stridor. Stridor is inspiratory, low-pitched, and exacerbated by any exertion: crying, agitation, or feeding. The stridor is caused, in part, by decreased laryngeal tone leading to supraglottic collapse during inspiration. Symptoms usually appear within the 1st 2 wk and increase in severity for up to 6 mo, although gradual improvement can begin at any time. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, laryngopharyngeal reflux disease, and neurologic disease influence the severity of the disease and thereby the clinical course.

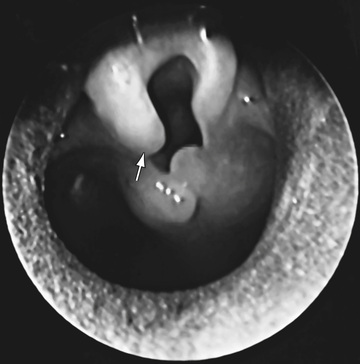

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made primarily based on symptoms. The diagnosis is confirmed by outpatient flexible laryngoscopy (Fig. 413.1 ). When the work of breathing is moderate to severe, airway films and chest radiographs are indicated. Laryngomalacia can contribute to feeding difficulties and dysphagia in some children because of decreased laryngeal sensation and poor suck-swallow-breath coordination. When the inspiratory stridor sounds wet or is associated with a cough or when there is a history of repeat upper respiratory illness or pneumonia, dysphagia should be considered. When dysphagia is suspected, a contrast swallow study and/or a fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) may be considered. Because 15–60% of infants with laryngomalacia have synchronous airway anomalies, complete bronchoscopy is undertaken for patients with moderate to severe obstruction.

Treatment

Expectant observation is suitable for most infants because most symptoms resolve spontaneously as the child and airway grow. Laryngopharyngeal reflux is managed aggressively with antireflux medications, such as histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Risk:benefit ratio should be assessed in each patient because these medications, particularly PPIs, have been associated with iron-deficiency anemia, increased incidence of pneumonia, gastroenteritis, and Clostridium difficile infections, among others. In 15–20% of patients, symptoms are severe enough to cause progressive respiratory distress, cyanosis, failure to thrive, or cor pulmonale. In these patients, surgical intervention via supraglottoplasty is considered. Supraglottoplasty is 90% successful in relieving upper airway obstruction caused by laryngomalacia. Some comorbidities, such as cardiac disease, neurologic disease, pulmonary disorders, or craniofacial anomalies may be poor prognostic indicators that would suggest earlier intervention.

Bibliography

Bedwell J, Zalzal G. Laryngomalacia. Semin Pediatr Surg . 2016;25(3):119–122.

Carter J, et al: International Pediatric ORL Group (IPOG) Laryngomalacia Consensus Recommendations.

D'Agostino JA, Passarella M, Martin AE, Lorch SA. Use of gastroesophageal reflux medications in premature infants after NICU discharge. Pediatrics . 2016;138(6):e20161977.

Dickson JM, Richter GT, Derr JM, et al. Secondary airway lesions in infants with laryngomalacia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol . 2009;118:37–43.

Schroeder J, Tharrar K, Poznanovic S, et al. Aspiration following CO2 laser assisted supraglattoplasty. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol . 2008;77:985–990.

Thompson D. Abnormal integrative function in laryngomalacia. Laryngoscope . 2007;117(6 Pt 2 Suppl 114):1–33.

Thompson DM. Laryngomalacia: factors that influence disease severity and outcomes of management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2010;18(6):564–570.

Congenital Subglottic Stenosis

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

Clinical Manifestations

Congenital subglottic stenosis is the second most common cause of stridor. The subglottis is the narrowest part of the upper airway in a child and is located in the space extending from the undersurface of the true vocal folds to the inferior margin of the cricoid cartilage. Subglottic stenosis is a narrowing of the subglottic larynx and manifests in the infant with respiratory distress and biphasic or primarily inspiratory stridor. It may be congenital or acquired. Symptoms often occur with a respiratory tract infection as the edema and thickened secretions of a common cold narrow an already compromised airway leading to recurrent or persistent croup-like symptoms.

Biphasic or primarily inspiratory stridor is the typical presenting symptom for congenital subglottic stenosis. The edema and thickened secretions of the common cold further narrow an already marginal airway that leads to croup-like symptoms. In a child with recurrent bronchiolitis, diagnosis of congenital subglottic stenosis should be considered. The stenosis can be caused by an abnormally shaped cricoid cartilage; by a tracheal ring that becomes trapped underneath the cricoid cartilage; or by soft tissue thickening caused by ductal cysts, submucosal gland hyperplasia, or fibrosis. Acquired subglottic stenosis refers to stenosis caused by extrinsic factors, most commonly resulting from prolonged intubation, and is discussed in further detail in Chapter 415 .

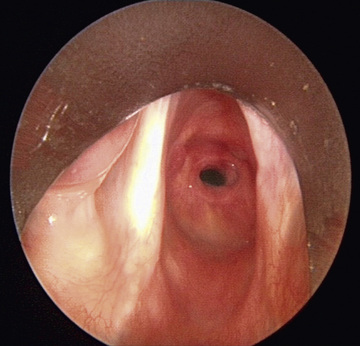

Diagnosis

The diagnosis made by airway radiographs is confirmed by direct laryngoscopy. During diagnostic laryngoscopy the subglottic larynx is visualized directly and sized objectively using endotracheal tubes (Fig. 413.2 ). The percentage of stenosis is determined by comparing the size of the patients’ larynx to a standard of laryngeal dimensions based on age. Stenosis >50% is usually symptomatic and often requires treatment. As with all cases of upper airway obstruction, tracheostomy is avoided when possible. Subglottic stenosis is typically measured using the Myer-Cotton system, with grade I through grade IV subglottic stenosis indicating the severity of narrowing. Dilation and endoscopic laser surgery can be attempted in grade I and II, although they may not be effective because most congenital stenoses are cartilaginous. Anterior cricoid split or laryngotracheal reconstruction with cartilage graft augmentation is typically used in grade III and IV subglottic stenosis. The differential diagnosis includes other anatomic anomalies, as well as a hemangioma or papillomatosis.

Bibliography

Myer CM, O'Conner DM, Cotton RT. Proposed grading system for subglottic stenosis based on endotracheal tube sizes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol . 1994;103(4 Pt 1):319–323.

Sandu K, Monnier P. Cricotracheal resection. Otolaryngol Clin North Am . 2008;41:988–998.

Schroeder JW Jr, Holinger LD. Congenital laryngeal stenosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am . 2008;41:865–875.

Vocal Cord Paralysis

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

Vocal cord paralysis is the third most common congenital laryngeal anomaly that produces stridor in infants and children. Congenital central nervous system lesions such as Chiari malformation, myelomeningocele, and hydrocephalus or birth trauma may be associated with bilateral paralysis. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis produces airway obstruction manifested by respiratory distress and high-pitched inspiratory stridor, aphonatory or dysphonic sound, or inspiratory weak cry.

Unilateral vocal cord paralysis is most often iatrogenic, as a result of surgical treatment for aerodigestive (tracheoesophageal fistula) and cardiovascular (patent ductus arteriosus repair) anomalies, although they may also be idiopathic. Unilateral paralysis causes aspiration, coughing, and choking; the cry is weak and breathy, but stridor and other symptoms of airway obstruction are less common. Vocal cord paralysis in older children may be due to a Chiari malformation or tumors compressing the vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of vocal cord paralysis is made by awake flexible laryngoscopy. The examination will demonstrate an inability or weakness to abduct the involved vocal cord. A thorough investigation for the underlying primary cause is indicated. Because of the association with other congenital lesions, evaluation includes neurology and cardiology consultations, imaging of the course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and diagnostic endoscopy of the larynx, trachea, and bronchi.

Treatment

Treatment is based on the severity of the symptoms. Idiopathic vocal cord paralysis in infants usually resolves spontaneously within 6-12 mo. If it is not resolved by 2-3 yr of age, function typically does not recover.

For unilateral vocal cord paralysis, injection laterally to the paralyzed vocal cord moves it medially to reduce aspiration and related complications. Reinnervation procedures using the ansa cervicalis have been successful in regaining some function of unilateral vocal cord.

Bilateral paralysis may require temporary tracheotomy in 50% of patients. Airway augmentation procedures in bilateral vocal cord paralysis typically focus on widening the posterior glottis, such as an endoscopically placed or open posterior glottis cartilage graft, arytenoidectomy, or arytenoid lateralization. These procedures are generally successful in reducing the obstruction; however, they may result in dysphagia and aspiration.

Congenital Laryngeal Webs and Atresia

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

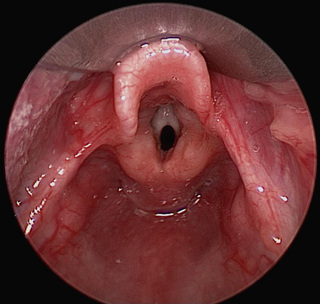

Congenital laryngeal webs are typically located in the anterior glottis with subglottic extension and associated subglottic stenosis, and they result from incomplete recanalization of the laryngotracheal tube. They may be asymptomatic. Thick webs may be suspected in lateral radiographs of the airway. Chromosomal and cardiovascular anomalies, as well as chromosome 22q11 deletion, are common in patients with congenital laryngeal web. Diagnosis is made by direct laryngoscopy (Fig. 413.3 ). Treatment might require only incision or dilation. Webs with associated subglottic stenosis are likely to require cartilage augmentation of the cricoid cartilage (laryngotracheal reconstruction). Laryngeal atresia occurs as a complete glottic web due to failure of laryngeal and tracheal recanalization and may be associated with tracheal agenesis and tracheoesophageal fistula. Laryngeal atresia may be detected in the prenatal period, and preparations should be made for establishment of definitive airway at birth. Other times, congenital laryngeal atresia is a cause of respiratory distress in the newborn and is diagnosed only upon initial direct laryngoscopy.

Bibliography

Ambrosiom A, Magit A. Respiratory distress of the newborn: congenital laryngeal atresia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol . 2012;76(11):1685–1687.

McElhinney DB, Jacobs I, McDonald-McGinn DM, et al. Chromosomal and cardiovascular anomalies associated with congenital laryngeal web. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol . 2002;66(1):23–27.

Shah J, White K, Dohar J. Vocal characteristics of congenital anterior glottic webs in children: a case report. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol . 2015;79(6):941–945.

Congenital Subglottic Hemangioma

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

Subglottic hemangioma is a rare cause of early infancy respiratory distress. Symptoms typically present within the 1st 2-6 mo of life. The most common presenting symptom is biphasic stridor, somewhat more prominent during inspiration. This is exacerbated by crying and acute viral illnesses. A barking cough, hoarseness, and symptoms of recurrent or persistent croup are typical. Only 1% of children who have cutaneous hemangiomas will have a subglottic hemangioma. However, 50% of those with a subglottic hemangioma will have a cutaneous hemangioma. A facial hemangioma is not always present, but when it is evident, it is in the beard distribution, and thus, respiratory distress in a child with a vascular lesion in this area should prompt further investigation. Chest and neck radiographs can show the characteristic asymmetric narrowing of the subglottic larynx. Airway vascular lesions may also be associated with PHACES syndrome , characterized by Posterior Fossa Malformations, Hemangioma, Arterial lesions of head and neck, Cardiac anomalies, Eye Anomalies, and Sternal cleft. More than 50% of children with PHACES syndrome have an airway vascular lesion. Treatment options range from conservative monitoring, steroid injection to tracheotomy and airway reconstruction. Propranolol has become a mainstay in initial therapy of subglottic hemangioma; however, it is estimated that up to 50% of patients with subglottic hemangioma may not have a long-term response to propranolol, indicating a need for close airway monitoring in these patients (Fig. 413.4 ). Treatment is further discussed in Chapter 417.3 .

Bibliography

Durr ML, Meyer NK, Huoh KC, et al. Airway hemangiomas in PHACE syndrome. Laryngoscope . 2012;122:2323–2329.

Hardison S, Wan W, Dodson KM. The use of propranolol in the treatment of subglottic hemangiomas: a literature review and Meta-analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol . 2016;90:175–180.

Rahbar R, et al. The biology and management of subglottic hemangioma: past, Present, Future. Laryngoscope . 2004;114(11):1880–1891.

Saetti R, Silvestrini M, Cutrone C, et al. Treatment of congenital subglottic hemangiomas: our experience compared with reports in the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2008;134(8):848–851.

Siegel B, Mehta D. Open airway surgery for subglottic hemangioma in the era of propranolol: is it still indicated. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol . 2015;79(7):1124–1127.

Laryngoceles and Saccular Cysts

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

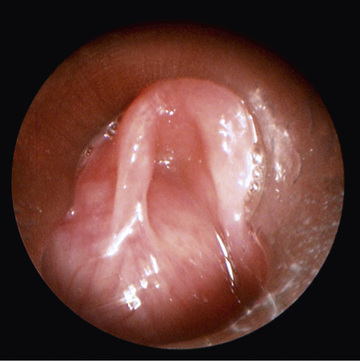

A laryngocele is an abnormal air-filled dilation of the laryngeal saccule that arises vertically between the false vocal cord, the base of the epiglottis, and the inner surface of the thyroid cartilage. It communicates with the laryngeal lumen and, when intermittently filled with air, causes hoarseness and dyspnea. A saccular cyst (congenital cyst of the larynx) is distinguished from the laryngocele in that its lumen is isolated from the interior of the larynx and it contains mucus, not air. In infants and children, laryngoceles cause hoarseness and dyspnea that may increase with crying. Saccular cysts may cause respiratory distress and stridor at birth and may require early airway intervention. Intubation can be challenging because the supraglottic and laryngeal anatomy may be distorted. In addition, complete airway obstruction may occur on induction with neuromuscular blockade acting on laryngeal tone. A saccular cyst may be visible on radiography, but the diagnosis is made by laryngoscopy (Fig. 413.5 ). Needle aspiration of the cyst confirms the diagnosis but rarely provides a cure. Surgical excision is the therapy of choice for management of saccular cysts and laryngoceles. Approaches include endoscopic CO2 laser excision, endoscopic extended ventriculotomy (marsupialization or unroofing), or, traditionally, external excision.

Bibliography

Civantos FJ, Holinger LD. Laryngoceles and saccular cysts in infants and children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 1992;118:296–300.

Kirse DJ, Rees CJ, Celmer AW, et al. Endoscopic extended ventriculotomy for congenital saccular cysts of the larynx in infants. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2006;132(7):724–728.

Parkes WJ, Propst EJ. Advances in the diagnosis, Management, and treatment of neonates with laryngeal disorders. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med . 2016 http://dx.doi.org.10.1016/j.siny.2016.03.003 .

Posterior Laryngeal Cleft and Laryngotracheoesophageal Cleft

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

The posterior laryngeal cleft is characterized by aspiration and is the result of a deficiency in the midline of the posterior larynx. Posterior laryngeal clefts are categorized into 4 types. Type 1 clefts are mild and the interarytenoid notch extends only down to the level of the true vocal cords; 60% of these will cause no symptoms and will not require surgical repair. In severe cases, the cleft (type 4) extends inferiorly into the cervical or thoracic trachea so there is no separation between the trachea and esophagus, creating a laryngotracheoesophageal cleft. Laryngeal clefts can occur in families and are likely to be associated with tracheal agenesis, tracheoesophageal fistula, and multiple congenital anomalies, as with G syndrome, Opitz-Frias syndrome, and Pallister-Hall syndrome.

Initial symptoms are those of aspiration and recurrent respiratory infections. Esophagogram is undertaken to evaluate presence of aspiration or laryngeal penetration of ingested contrast material. A FEES exam may be undertaken by an otolaryngologist with assistance of a speech language and pathology team to observe pattern of liquid spillage during swallow and may identify a cleft. However, the gold standard of diagnosis remains operative laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy with palpation of the posterior larynx. This assists in determining length of the cleft and guides treatment options. A type I cleft extends to, but not beyond, the vocal cords. A type II cleft extends beyond the vocal cords to, but not through, the cricoid cartilage. A type III cleft extends through cricoid into cervical trachea. A type IV cleft extends into thoracic trachea. Treatment is based on the cleft type and the symptoms; in general, a type I cleft may be managed endoscopically, whereas higher grades may require an open procedure. Stabilization of the airway is the first priority. Gastroesophageal reflux must be controlled and a careful assessment for other congenital anomalies is undertaken before repair. Several endoscopic and open cervical and transthoracic surgical repairs have been described.

Bibliography

Alexander NS, et al. Postoperative observation of children after endoscopic type I posterior laryngeal cleft repair. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2015;152(1):153–158.

Moungthong G, Holinger LD. Laryngotracheoesophageal clefts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol . 1997;106:1002–1011.

Rahbar R, Roullon I, Roger G, et al. The presentation and management of laryngeal cleft. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2006;132:1335–1341.

Shehab ZP, Bailey CM. Type IV laryngotracheoesophageal clefts—recent 5 year experience at great ormond street hospital for children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol . 2001;60(1):1–9.

Vascular and Cardiac Anomalies

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

Aberrant cardiopulmonary vascular anatomy may directly impact the trachea and bronchi. The aberrant innominate artery is the most common cause of secondary tracheomalacia (see Chapter 459 ). It may be asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, or it may cause severe symptoms. Expiratory wheezing and cough occur and, rarely, reflex apnea or “dying spells.” Surgical intervention is rarely necessary. Infants are most commonly treated expectantly because the problem is often self-limited.

The term vascular ring is used to describe vascular anomalies that result from abnormal development of the aortic arch complex. The double aortic arch is the most common complete vascular ring, encircling both the trachea and esophagus, compressing both. With few exceptions, these patients are symptomatic by 3 mo of age. Respiratory symptoms predominate, but dysphagia may be present. The diagnosis is established by barium esophagogram that shows a posterior indentation of the esophagus by the vascular ring (see Fig. 459.2 in Chapter 459 ). CT or MRI with angiography provides the surgeon the information needed.

Other vascular anomalies include the pulmonary artery sling, which also requires surgical correction. The most common open (incomplete) vascular ring is the left aortic arch with aberrant right subclavian artery. Although common, it is usually asymptomatic, although dysphagia lusoria may be described. This is characterized as dysphagia caused by an aberrant subclavian coursing behind the esophagus, leading to esophageal compression and difficulty with bolus transit.

Congenital cardiac defects are likely to compress the left main bronchus or lower trachea. Any condition that produces significant pulmonary hypertension increases the size of the pulmonary arteries, which in turn cause compression of the left main bronchus. Surgical correction of the underlying pathology to relieve pulmonary hypertension relieves the airway compression.

Bibliography

Backer CL, Monge MC, Popescu AR, et al. Vascular rings. Semin Pediatr Surg . 2016;25(3):165–175.

Backer CM, Mavroudis C, Gerber ME, et al. Tracheal surgery in children: an 18-year review of four techniques. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg . 2001;19:777–784.

Hannemann K, Newman B, Chan F. Congenital variants and anomalies of the aortic arch. Radiographics . 2017;37(1):32–51.

Hofferberth SG, Watters K, Rahbar R, Fynn-Thompson F: Management of congenital tracheal stenosis.

Tracheal Stenoses, Webs, and Atresia

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

Long segment congenital tracheal stenosis with complete tracheal rings typically occurs within the 1st yr of life, usually after a crisis has been precipitated by an acute respiratory illness. The diagnosis may be suggested by plain radiographs. CT with contrast delineates associated intrathoracic anomalies such as the pulmonary artery sling, which occurs in one third of patients; one-fourth have associated cardiac anomalies. Bronchoscopy is the best method to define the degree and extent of the stenosis and the associated abnormal bronchial branching pattern. Treatment of clinically significant stenosis involves tracheal resection of short segment stenosis, slide tracheoplasty for long segment stenosis or tracheal rings. Congenital soft tissue stenosis and thin webs are rare. Dilation may be all that is required.

Foregut Cysts

Jill N. D'Souza, James W. Schroeder Jr

The embryologic foregut gives rise to the pharynx, lower respiratory tract, esophagus, stomach, duodenum, and hepatobiliary tract, and duplication cysts can occur anywhere along this tract. Foregut duplications account for approximately one third of all duplications. The bronchogenic cyst, intramural esophageal cyst (esophageal duplication), and enteric cyst can all produce symptoms of respiratory obstruction and dysphagia. The diagnosis is suspected when chest radiographs or CT scan delineate the mass and, in the case of enteric cyst, the associated vertebral anomaly. The treatment of all foregut cysts is surgical excision.