Neoplasms of the Larynx, Trachea, and Bronchi

Saied Ghadersohi, James W. Schroeder Jr

Vocal Nodules

Saied Ghadersohi, James W. Schroeder Jr

Vocal nodules , which are not true neoplasms, are the most common cause of chronic hoarseness in children. Chronic vocal abuse or misuse (i.e., frequent yelling and screaming) produces localized vascular congestion, edema, hyalinization, and epithelial thickening in the bilateral vocal cords. This grossly appears as nodules that disrupt the normal vibration of the cords during phonation. Vocal abuse is the main factor, and the voice is worse in the evenings. Differential can include unilateral lesions such as vocal cord cysts and polyps; however, these usually have an acute inciting event and are rarer in children.

Treatment is primarily nonsurgical with voice therapy used in children >4 yr of age who can participate in therapy, and clinical monitoring with behavioral therapy in younger children or those with developmental delay. In addition, laryngopharyngeal reflux commonly exacerbates vocal abuse–induced irritation of the cord, Therefore antireflux therapy can also be implemented (see Chapter 349 ). Surgical excision of vocal cord lesions in children is controversial and is rarely indicated but may be necessary if the child is unable to communicate adequately, becomes aphonic, or requires tension and straining to make any utterance whatsoever.

Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis

Saied Ghadersohi, James W. Schroeder Jr

Papillomas are the most common respiratory tract neoplasms in children, occurring in 4.3 in 100,000. They are simply warts—benign tumors— caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), most commonly types 6 and 11 (see Chapter 293 ). Seventy-five percent of recurrent respiratory papilloma cases occur in children younger than age 5 yr, but the diagnosis may be made at any age. In general, neonatal-onset disease is a negative prognostic factor with higher mortality and need for tracheostomy. Sixty-seven percent of children with RRP are born to mothers who had condylomas during pregnancy or parturition. The mode of HPV transmission is still not clear. Neonates have been reported to have RRP, suggesting intrauterine transmission of HPV. Despite close association with vaginal condylomata, only 1 in 231 to 400 vaginal births go on to develop respiratory papillomatosis. Therefore other risk factors contribute to transmission, and C-section delivery for prevention cannot be recommended. However, preventive measures can include the prospective widespread use of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine to help eliminate maternal and paternal HPV reservoirs and possibly decrease cases of RRP caused by HPV 6 and 11.

Clinical Manifestations

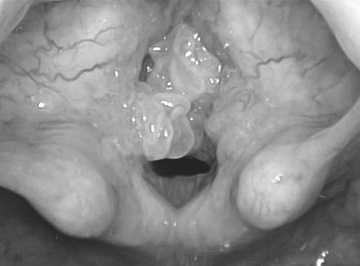

The clinical course involves remissions and exacerbations of recurrent papillomas most commonly on the larynx (usually the vocal cords), causing progressively worsening hoarseness, sleep-disordered breathing, exertional dyspnea, stridor, and, if left untreated, eventually severe airway obstruction (Fig. 417.1 ). Although it is a benign disease, lesions can spread throughout the aerodigestive tract in 31% of patients, most commonly the oral cavity, trachea, and bronchi. Rarely these lesions can undergo malignant conversion (1.6%); however, some patients may have spontaneous remission. Patients may be initially diagnosed with asthma, croup, vocal nodules, or allergies.

Treatment

The treatment of RRP is endoscopic surgical removal with three goals. First, debulking/complete removal of the lesions, secondly, preservation of normal structures, and finally, prevention of scar formation in the affected areas. Most surgeons in North America prefer the microdebrider, although microsurgery, CO2 , and KTP laser techniques have been described. Despite these techniques, some form of adjunct therapy may be needed in up to 20% of cases. The most widely accepted indications for adjunct therapy are a need for more than four surgical procedures per year, rapid regrowth of papillomata with airway compromise, or distal multisite spread of disease. Adjunct therapies can be inhaled or administered intralesionally or systemically and include antiviral modalities (interferon, ribavirin, acyclovir, cidofovir), antiangiogenic agents such as bevacizumab (Avastin), photodynamic therapy, dietary supplement (indole-3-carbinol), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (COX2 inhibitors, Celebrex), retinoids, and mumps vaccination.

Bibliography

Derkay CS, Wiatrak B. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: a review. Laryngoscope . 2008;118:1236–1245.

Hawks M, Campisi P, Zafar R, et al. Time course of juvenile onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis caused by human papillomavirus. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 2008;27:149–154.

Maturo SC, Hartnick CJ. Juvenile-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Adv Otorhinolaryngol . 2012;73:105–108.

Shah KV, Stern WF, Shah FK, et al. Risk factors for juvenile onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 1998;17:372 [PMID] 9613648.

Syrjanen S. HPV in head and neck cancer. J ClinVirol. 2005;32(Suppl 1):S59–S66.

Zeitels SM, Barbu AM, Landau-Zemer T, et al. Local injection of bevacizumab (Avastin) and angiolytic KTP laser treatment of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis of the vocal folds: a prospective study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol . 2011;120(10):627–634 [PMID] 22097147.

Congenital Subglottic Hemangioma

Saied Ghadersohi, James W. Schroeder Jr

Clinical Manifestations

Typically, congenital subglottic hemangiomas are symptomatic within the first 2 mo of life, almost all occurring before 6 mo of age. Much like the cutaneous infantile hemangiomas, these lesions have 2 phases: a proliferative phase with rapid growth in the first 6 mo of life, then they stabilize by 1 yr, and a slow involution phase typically by age 3. Patients present with usually inspiratory but sometimes biphasic stridor. The infant can have a barking cough and temporarily respond to steroids, similar to persistent croup. Fifty percent of congenital subglottic hemangiomas are associated with facial lesions, but the converse is not true. Radiographs classically delineate an asymmetric subglottic narrowing. The diagnosis is made by direct laryngoscopy.

Treatment

The medical treatment of hemangiomas traditionally was with long-term systemic steroids, which often had severe side effects, including growth retardation and adrenal suppression. Prednisone 2-4 mg/kg/day is given orally for 4-6 wk, typically with partial regression of the lesion. The dosage is then tapered. If there is no response, the drug is discontinued. Propranolol was introduced in 2008 and rapidly became the first-line treatment of infantile and subglottic hemangiomas, including in a recent randomized clinical trial comparing it with systemic steroids. The mechanism is thought to be through VEGF or adrenergic vasoconstriction pathways and can involute the lesion in a few days. Typically, treatment is with 1-3 mg/kg/day of propranolol for 4-12 mo, based on clinical monitoring as noted in a 2011 consensus guideline. Prescreening patients with cardiology workup (i.e., electrocardiogram) is advised. Side effects include hypotension, bradycardia, bronchospasm, and hypoglycemia; children treated with propranolol need to be monitored closely.

Surgical management can range from intralesional steroid injection to avoid systemic steroid side effects, CO2 , or KTP laser endoscopic excision, and ultimately as a last resort tracheostomy can establish a safe airway, allowing time for the lesion to involute per its natural course.

Bibliography

Bauman N, McCarter R, Guzzetta P, et al. Propranolol vs prednisolone for symptomatic proliferating infantile hemangiomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2014;140(4):323.

Drolet BA, et al. Initiation and use of propranolol for infantile hemangioma: a report of a consensus conference. Pediatrics . 2013;131:128–140 [PMID] 23266923.

England R, Banerjee D, Shawber C, et al. Propranolol action is mediated via the beta-2 adrenergic receptor in hemangioma stem cells. Plast Reconstr Surg . 2013;131(5):62.

Hoff SR, Rastatter JC, Richter GT. Head and neck vascular lesions. Otolaryngol Clin North Am . 2015;48(1):29–45.

Vascular Anomalies

Saied Ghadersohi, James W. Schroeder Jr

Based on the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies classification system, these lesions can be classified into vascular malformations and vascular tumors. The most common vascular tumors are infantile/subglottic hemangiomas and were previously discussed. Vascular malformations are not true neoplastic lesions. They have a normal rate of endothelial turnover and various channel abnormalities. They are subcategorized based on high or low flow and by their predominant type (capillary, venous, arterial, lymphatic, or a combination thereof). Overall, vascular malformations are uncommon, and they rarely occur in the larynx and airway. When they do occur, they are often an extension from elsewhere in the head and neck. It should be noted that these lesions can expand with a viral upper respiratory infection. They can be diagnosed with direct visualization during laryngoscopy or bronchoscopy or seen on CT/MRI imaging. Treatment usually entails a multidisciplinary team approach with early surgical or laser resection or sclerotherapy.

Bibliography

Behr GG, Johnson C. Vascular anomalies: hemangiomas and beyond—part 1, Fast-flow lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol . 2013;200(2):414–422.

Behr GG, Johnson CM. Vascular anomalies: hemangiomas and beyond—part 2, Slow-flow lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol . 2013;200(2):423–436.

Hoff SR, Rastatter JC, Richter GT. Head and neck vascular lesions. Otolaryngol Clin North Am . 2015;48(1):29–45.

Other Laryngeal Neoplasms

James W. Schroeder Jr, Lauren D. Holinger

Neurofibromatosis (see Chapter 614.1 ) rarely involves the larynx. When children are affected, limited local resection is undertaken to maintain an airway and optimize the voice. Complete surgical extirpation is virtually impossible without debilitating resection of vital laryngeal structures. Most surgeons select the option of less-aggressive symptomatic surgery because of the poorly circumscribed and infiltrative nature of these fibromas. Rhabdomyosarcoma (see Chapter 527 ) and other malignant tumors of the larynx are rare. Symptoms of hoarseness and progressive airway obstruction prompt initial evaluation by flexible laryngoscopy in the office.

Tracheal Neoplasms

Saied Ghadersohi, James W. Schroeder Jr, Lauren D. Holinger

Tracheal tumors are extremely rare and include malignant and benign neoplasms; they may initially be misdiagnosed as asthma. The 2 most common benign tumors are inflammatory pseudotumor and hamartoma. The inflammatory pseudotumor is probably a reaction to a previous bronchial infection or traumatic insult. Growth is slow, and the tumor may be locally invasive. Hamartomas are tumors of primary tissue elements that are abnormal in proportion and arrangement.

Tracheal neoplasms manifest with stridor, wheezing, cough, or pneumonia and are rarely diagnosed until 75% of the lumen has been obstructed (Fig. 417.2 ). Chest radiographs or airway films can identify the obstruction. Pulmonary function studies demonstrate an abnormal flow-volume loop. A mild response to bronchodilator therapy may be misleading. Treatment is based upon the histopathology.

Bibliography

Desai DP, Holinger LD, Gonzalez-Crussi F. Tracheal neoplasms in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol . 1998;107(9 Pt 1):790–796.

Pugnale MJ, Maresh A, Sinha P, et al. Pediatric tracheal tumor masked by a history of travel: case report and literature review. Laryngoscope . 2015;125:1004–1007; 10.1002/lary.24968 .

Bronchial Tumors

Saied Ghadersohi, James W. Schroeder Jr

Bronchial tumors are rare. In 1 series, carcinoid tumors were the most common, followed by mucoepidermoid and pseudotumors. These patients can present with persistent pneumonia despite adequate treatment. The diagnosis is confirmed at bronchoscopy and biopsy; treatment depends on the histopathology.