Diagnostic Approach to Respiratory Disease

Julie Ryu, James S. Hagood, Gabriel G. Haddad

History

The history begins with a narrative provided by the parent/caretaker with input from the patient. It should include questions about respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough, pain, wheezing, snoring, apnea, cyanosis, exercise intolerance), as well as their chronicity, timing during day or night, and associations with activities including exercise or food intake. The respiratory system interacts with a number of other systems, and questions related to cardiac, gastrointestinal, central nervous, hematologic, and immune systems may be relevant. Questions related to gastrointestinal reflux, congenital abnormalities (airway anomalies, ciliary dyskinesia), or immune status may be important in a patient with repeated pneumonia. The family history is essential and should include inquiries about siblings and other close relatives with similar symptoms, or any chronic disease with respiratory components.

Physical Examination

Respiratory dysfunction usually produces detectable alterations in the pattern of breathing. Values for normal respiratory rates are presented in Table 81.1 and depend on many factors—most importantly, age. Repeated respiratory rate measurements are necessary because respiratory rates, especially in the young, are exquisitely sensitive to extraneous stimuli. Sleeping respiratory rates are more reproducible in infants than those obtained during feeding or activity. These rates vary among infants but average 40-50 breaths/min in the 1st few wk of life and usually <60 breaths/min in the 1st few days of life.

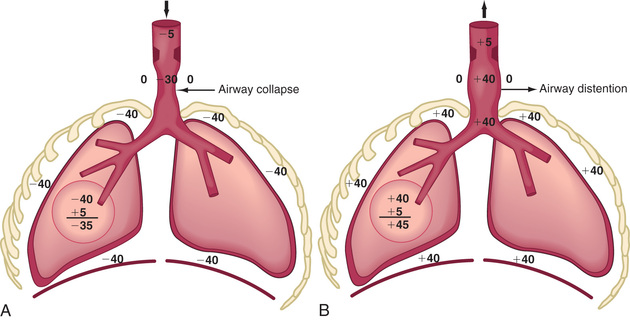

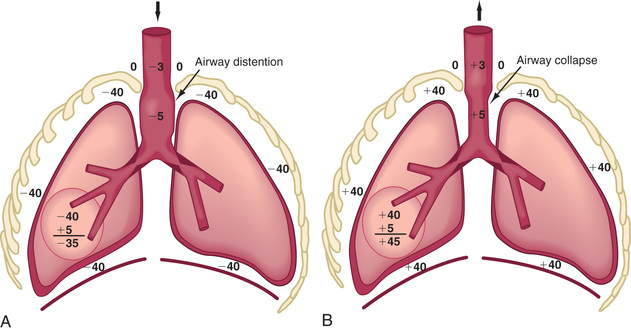

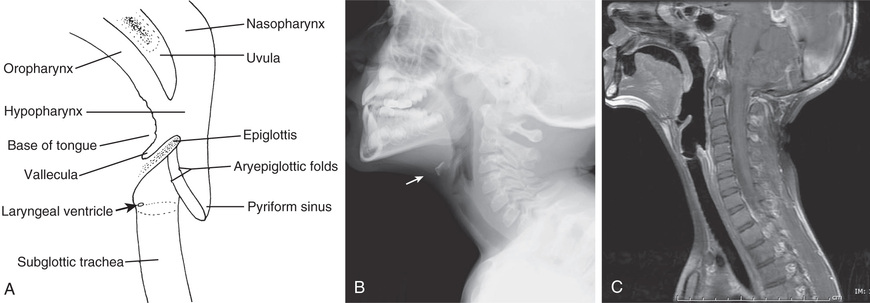

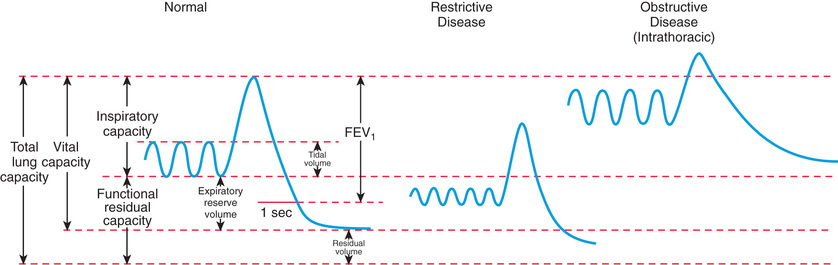

Respiratory control abnormalities can cause the child to breathe at a low rate or periodically. Mechanical abnormalities produce compensatory changes that are generally directed at altering minute ventilation to maintain alveolar ventilation. Decreases in lung compliance require increases in muscular force and breathing rate, leading to variable increases in chest wall retractions and nasal flaring. The respiratory excursions of children with restrictive disease are shallow. An expiratory grunt is common as the child attempts to raise the functional residual capacity (FRC) by closing the glottis at the end of expiration. The FRC is the amount of air left in the lungs after tidal expiration. Children with obstructive disease might take slower, deeper breaths. When the obstruction is extrathoracic (from the nose to the mid-trachea), inspiration is more prolonged than expiration, and an inspiratory stridor (a predominant inspiratory monophonic noise) can usually be heard (Fig. 400.1 ). When the obstruction is intrathoracic , expiration is more prolonged than inspiration, and the patient often has to make use of accessory expiratory muscles. Intrathoracic obstruction results in air trapping and, therefore, a larger residual volume, as well as a possible increase in FRC (Fig. 400.2 ).

Lung percussion has limited value in small infants because it cannot discriminate between noises originating from tissues that are close to each other. In adolescents and adults, percussion is usually dull in restrictive lung disease, with a pleural effusion, pneumonia, and atelectasis, but it is tympanitic in obstructive disease (asthma, pneumothorax).

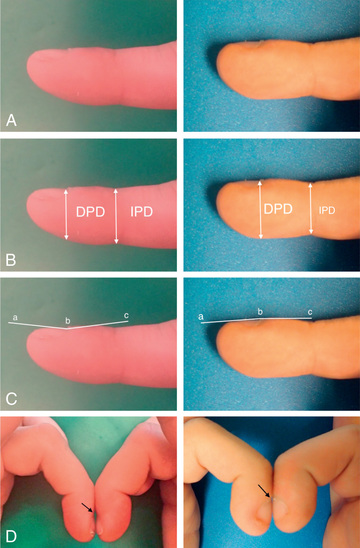

Auscultation confirms the presence of inspiratory or expiratory prolongation and provides information about the symmetry and quality of air movement. In addition, it often detects abnormal or adventitious sounds such as stridor ; crackles or rales , high-pitched, interrupted sounds found during inspiration and more rarely during early expiration, which denote opening of previously closed air spaces; or wheezes , musical, continuous sounds usually caused by the development of turbulent flow in narrow airways (Table 400.1 ). Digital clubbing is a sign of chronic hypoxia and chronic lung disease (Fig. 400.3 ) but may be a result of nonpulmonary etiologies (Table 400.2 ).

Table 400.1

| BASIC SOUNDS | MECHANISMS | ORIGIN | ACOUSTICS | RELEVANCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Turbulent flow, vortices, other | Central (expiration), lobar to segmental airways (inspiration) | Low pass filtered noise (<100 to >1,000 Hz) | Regional ventilation, airway caliber |

| Tracheal | Turbulent flow, flow impinging on airway walls | Pharynx, larynx, trachea, large airways | Noise with resonances (<100 to >3,000 Hz) | Upper airway configuration |

| ADVENTITIOUS SOUNDS | ||||

| Wheezes | Airway wall flutter, vortex shedding, other | Central and lower airways | Sinusoidal (<100 to >1,000 Hz, duration typically >80 msec) | Airway obstruction, flow limitation |

| Rhonchi | Rupture of fluid films, airway wall vibration | Larger airways | Series of rapidly dampened sinusoids (typically <300 Hz and duration <100 msec) | Secretions, abnormal airway collapsibility |

| Crackles | Airway wall stress-relaxation | Central and lower airways | Rapidly dampened wave deflections (duration typically <20 msec) | Airway closure, secretions |

Modified from Pasterkamp H, Kraman SS, Wodicka GR: Respiratory sounds. Advances beyond the stethoscope, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156[3]:974–987, 1997.

Table 400.2

Nonpulmonary Diseases Associated With Clubbing

| CARDIAC |

| HEMATOLOGIC |

| GASTROINTESTINAL |

| OTHER |

| UNILATERAL CLUBBING |

From Pasterkamp H: The history and physical examination. In Wilmott RW, Boat TF, Bush A, et al, editors: Kendig and Chernick's disorders of the respiratory tract in children, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2012, Elsevier.

Blood Gas Analysis

The main function of the respiratory system is to remove carbon dioxide from and add oxygen to the systemic venous blood brought to the lung. The composition of the inspired gas, ventilation, perfusion, diffusion, and tissue metabolism has a significant influence on the arterial blood gases.

The total pressure of the atmosphere at sea level is 760 torr. With increasing altitude, the atmospheric pressure decreases. The total atmospheric pressure is equal to the sum of partial pressures exerted by each of its component gases. Alveolar air is 100% humidified, so in alveolar gas calculations, the inspired gas is also presumed to be 100% humidified. At a temperature of 37°C (98.6°F) and 100% humidity, water vapor exerts pressure of 47 torr, regardless of altitude. In a natural setting, the atmosphere consists of 20.93% oxygen. Partial pressure of oxygen in inspired gas (PiO 2 ) at sea level is therefore (760 − 47) × 20.93% = 149 torr. When breathing 40% oxygen at sea level, PiO 2 is (760 − 47) × 40% = 285 torr. At higher altitudes, breathing different concentrations of oxygen, PiO 2 is less than at sea level, depending on the prevalent atmospheric pressures. In Denver (altitude of 5,000 feet and barometric pressure of 632 torr), PiO 2 in room air is (632 − 47) × 20.93% = 122 torr, and in 40% oxygen, it is (632 − 47) × 40% = 234 torr.

Minute volume is a product of VT and respiratory rate. Part of the VT occupies the conducting airways (anatomic dead space), which does not contribute to gas exchange in the alveoli. Alveolar ventilation is the volume of atmospheric air entering the alveoli and is calculated as (VT − dead space) × respiratory rate. Alveolar ventilation is inversely proportional to arterial PCO 2 (PaCO 2 ). When alveolar ventilation is halved, PaCO 2 is doubled. Conversely, doubling of alveolar ventilation decreases PaCO 2 by 50%. Alveolar PO 2 (PaO 2 ) is calculated by the alveolar air equation as follows, where R is the respiratory quotient. For practical purposes, PACO 2 is substituted by arterial PCO 2 (PaCO 2 ), and R is assumed to be 0.8. According to the alveolar air equation, for a given PiO 2 , a rise in PaCO 2 of 10 torr results in a decrease in PAO 2 by 10 ÷ 0.8, or 10 × 1.25, or 12.5 torr. Thus proportionately inverse changes in PAO 2 occur to the extent of 1.25× the changes in PACO 2 (or PaCO 2 ).

After the alveolar gas composition is determined by the inspired gas conditions and process of ventilation, gas exchange occurs by the process of diffusion and equilibration of alveolar gas with pulmonary capillary blood. Diffusion depends on the alveolar capillary barrier and the amount of available time for equilibration. In health, the equilibration of alveolar gas and pulmonary capillary blood is complete for both oxygen and carbon dioxide. In diseases in which the alveolar capillary barrier is abnormally increased (alveolar interstitial diseases) and/or when the time available for equilibration is decreased (increased blood flow velocity), diffusion is incomplete. Because of its greater solubility in liquid medium, carbon dioxide is 20 times more diffusible than oxygen. Therefore, diseases with diffusion defects are characterized by marked alveolar-arterial oxygen (A-aO2 ) gradients and hypoxemia. Significant elevation of CO2 does not occur as a result of a diffusion defect unless there is coexistent hypoventilation.

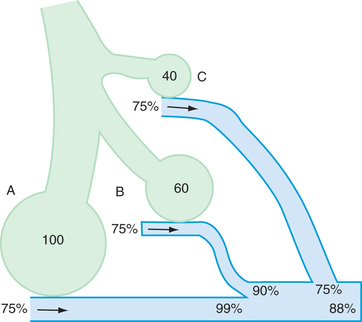

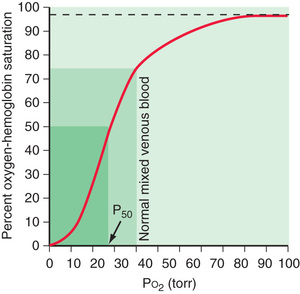

Venous blood brought to the lungs is “arterialized” after diffusion is complete. After complete arterialization, the pulmonary capillary blood should have the same PO 2 and PCO 2 as in the alveoli. The arterial blood gas composition is different from that in the alveoli, even in normal conditions, because there is a certain amount of dead space ventilation as well as venous admixture in a normal lung. Dead space ventilation results in a higher PaCO 2 than PACO 2 , whereas venous admixture or right-to-left shunting results in a lower PaO 2 compared with the alveolar gas composition (Fig. 400.4 ). PaO 2 is a reflection of the amount of oxygen dissolved in blood, which is a relatively minor component of total blood oxygen content. For every 100 torr PO 2 , there is 0.3 mL of dissolved O2 in 100 mL of blood. The total blood oxygen content is composed of the dissolved oxygen and the oxygen bound to hemoglobin (Hb). Each gram of Hb carries 1.34 mL of O2 when 100% saturated with oxygen. Thus 15 g of Hb carries 20.1 mL of oxygen. Arterial oxygen content (CaO 2 ) , expressed as mL O2 /dL blood, can be calculated as (PaO 2 × 0.003) + (Hb × 1.34 × SO 2 ), where Hb is grams of Hb per deciliter of blood and SO 2 is percentage of oxyhemoglobin saturation. The relationship of PO 2 and the amount of oxygen carried by the Hb is the basis of the O2 -Hb dissociation curve (Fig. 400.5 ). The PO 2 at which Hb is 50% saturated is referred to as P50 . At a normal pH, Hb is 94% saturated at PO 2 of 70, and little further gain in saturation is accomplished at a higher PO 2 . At PO 2 <50, there is a steep decline in saturation and therefore the oxygen content.

Oxygen delivery to tissues is a product of oxygen content and cardiac output. When Hb is near 100% saturated, blood contains approximately 20 mL oxygen per 100 mL or 200 mL/L. In a healthy adult, cardiac output is approximately 5 L/min, oxygen delivery 1,000 mL/min, and oxygen consumption 250 mL/min. Mixed venous blood returning to the heart has a PO 2 of 40 torr and is 75% saturated with oxygen. Blood oxygen content, cardiac output, and oxygen consumption are important determinants of mixed venous oxygen saturation. Given a steady-state blood oxygen content and oxygen consumption, the mixed venous saturation is an important indicator of cardiac output. A declining mixed venous saturation in such a state indicates decreasing cardiac output.

Clinical observations and interpretation of blood gas values are critical in localizing the site of the lesion and estimating its severity (Table 400.3 ). In airway obstruction above the carina (subglottic stenosis, vascular ring), blood gases reflect overall alveolar hypoventilation. This is manifested by an elevated PACO 2 and a proportionate decrease in PaO 2 as determined by the alveolar air equation. A rise in PaCO 2 of 20 torr decreases PaO 2 by 20 × 1.25 or 25 torr. In the absence of significant parenchymal disease and intrapulmonary shunting, such lesions respond very well to supplemental oxygen in reversing hypoxemia. Similar blood gas values, demonstrating alveolar hypoventilation and response to supplemental oxygen, are observed in patients with a depressed respiratory center and ineffective neuromuscular function, resulting in respiratory insufficiency. Such patients can be easily distinguished from those with airway obstruction by their poor respiratory effort.

Table 400.3

ABG , Arterial blood gas.

In intrapulmonary airway obstruction (asthma, bronchiolitis), blood gases reflect ventilation-perfusion imbalance and venous admixture. In these diseases, the obstruction is not uniform throughout the lungs, resulting in areas that are hyperventilated and others that are hypoventilated. Pulmonary capillary blood coming from hyperventilated areas has a higher PO 2 and lower PCO 2 , whereas that coming from hypoventilated regions has a lower PO 2 and higher PCO 2 . A lower blood PCO 2 can compensate for the higher PCO 2 because the Hb-CO2 dissociation curve is relatively linear. In mild disease, the hyperventilated areas predominate, resulting in hypocarbia. An elevated PaO 2 in hyperventilated areas cannot compensate for the decreased PaO 2 in hypoventilated areas because of the shape of the O2 -Hb dissociation curve. This results in venous admixture, arterial desaturation, and decreased PaO 2 (see Fig. 400.4 ). With increasing disease severity, more areas become hypoventilated, resulting in normalization of PaCO 2 with a further decrease in PaO 2 . A normal or slightly elevated PaCO 2 in asthma should be viewed with concern as a potential indicator of impending respiratory failure. In severe intrapulmonary airway obstruction, hypoventilated areas predominate, leading to hypercarbia, respiratory acidosis, and hypoxemia. The degree to which supplemental oxygenation raises PaO 2 depends on the severity of the illness and the degree of venous admixture.

In alveolar and interstitial diseases, blood gas values reflect both intrapulmonary right-to-left shunting and a diffusion barrier. Hypoxemia is a hallmark of such conditions occurring early in the disease process. PaCO 2 is either normal or decreased. An increase in PaCO 2 is observed only later in the course, as muscle fatigue and exhaustion result in hypoventilation. Response to supplemental oxygen is relatively poor with shunting and diffusion disorders compared with other lesions.

Most clinical entities present with mixed lesions. A child with a vascular ring might also have an area of atelectasis; the arterial blood gas reflects both processes. The blood gas values reflect the more dominant lesion.

An arterial blood gas analysis is probably the single most useful rapid test of pulmonary function. Although this analysis does not specify the cause of the condition or the specific nature of the disease process, it can give an overall assessment of the functional state of the respiratory system and clues about the pathogenesis of the disease. Because the detection of cyanosis is influenced by skin color, perfusion, and blood Hb concentration, the clinical detection by inspection is an unreliable sign of hypoxemia. Arterial hypertension, tachycardia, and diaphoresis are late, and not exclusive, signs of hypoventilation.

Blood gas exchange is evaluated most accurately by the direct measurement of arterial pressure of oxygen (PO 2 ), pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO 2 ), and pH. The blood specimen is best collected anaerobically in a heparinized syringe containing only enough heparin solution to displace the air from the syringe. The syringe should be sealed, placed in ice, and analyzed immediately. Although these measurements have no substitute in many conditions, they require arterial puncture and have been replaced to a great extent by noninvasive monitoring, such as capillary samples and/or oxygen saturation.

The age and clinical condition of the patient need to be taken into account when interpreting blood gas tensions. With the exception of neonates, values of arterial PO 2 <85 mm Hg are usually abnormal for a child breathing room air at sea level. Calculation of the alveolar–arterial oxygen gradient is useful in the analysis of arterial oxygenation, particularly when the patient is not breathing room air or in the presence of hypercarbia. Values of arterial PCO 2 >45 mm Hg usually indicate hypoventilation or a severe ventilation–perfusion mismatch, unless they reflect respiratory compensation for metabolic alkalosis (see Chapter 68 ).

Transillumination of the Chest

In infants up to at least 6 mo of age, a pneumothorax (see Chapter 122.14 ) can often be diagnosed by transilluminating the chest wall using a fiberoptic light probe. Free air in the pleural space often results in an unusually large halo of light in the skin surrounding the probe. Comparison with the contralateral chest is often very helpful in interpreting findings. This test is unreliable in older patients and in those with subcutaneous emphysema or atelectasis.

Radiographic Techniques

Chest X-Rays

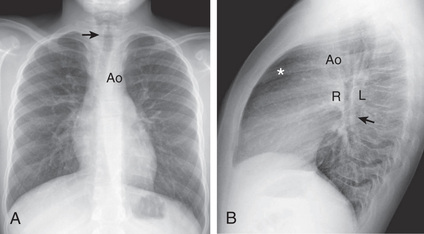

A posteroanterior and a lateral view (upright and in full inspiration) should be obtained, except in situations in which the child is medically unstable (Fig. 400.6 ). Portable images although useful in the latter situation, can give a somewhat distorted image. Expiratory images can be misinterpreted, although a comparison of expiratory and inspiratory images may be useful in evaluating a child with a suspected foreign body (localized failure of the lung to empty reflects bronchial obstruction: Chapter 414 ). Although images taken in a recumbent position are difficult to interpret when there is fluid within the pleural space or a cavity, if pleural fluid is suspected (see Chapter 429 ), decubitus images are indicated.

Upper Airway Film

A lateral view of the neck can yield invaluable information about upper airway obstruction (see Chapter 412 ) and particularly about the condition of the retropharyngeal, supraglottic, and subglottic spaces (which should also be viewed in an anteroposterior projection) (Fig. 400.7 ). Knowing the phase of respiration during which the film was taken is often essential for accurate interpretation. Magnified airway images are often helpful in delineating the upper airways. Patients with suggested obstruction should not be unattended in the radiology department.

Sinus and Nasal Images

The general utility of radiologic examination of the sinuses is uncertain because a large number of images have positive findings (low sensitivity and specificity). Imaging studies are not necessary to confirm the diagnosis of sinusitis in children younger than age 6 yr. CT scans are indicated if surgery is required, in cases of complications caused by sinus infection, in immunodeficient patients, and for recurrent infections that are not responsive to medical management.

Chest Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Chest CT and MRI can potentially provide images of higher quality and sensitivity than is possible with other imaging modalities. Chest CT identifies early abnormalities in young children with cystic fibrosis before pathologic changes are detectable by either plain chest radiographs or pulmonary function testing. However, several caveats must be noted. Conventional chest CT involves considerably higher radiation doses than plain images (see Chapter 736 ). The time required to perform chest CT examinations and the complications of respiratory and body motion mandates the use of sedation for this procedure in many infants and young children. However, improvements in imaging hardware and software have drastically reduced required radiation doses as well as imaging time, obviating the need for sedation in many patients. Chest CT is particularly useful in evaluating very small lesions (e.g., early metastases, mediastinal and pleural lesions, solid or cystic parenchymal lesions, pulmonary embolism, and bronchiectasis). The use of intravenous contrast material during CT imaging enhances vascular structures, distinguishing vessels from other soft-tissue densities. MRI does not involve ionizing radiation, but long imaging times are still involved, and sedation will be necessary to limit spontaneous movement. The utility of MRI of the chest is largely limited to the analysis of mediastinal, hilar, and vascular anatomy. Parenchymal structures and lesions are not well evaluated by MRI.

Fluoroscopy

Fluoroscopy is especially useful for evaluating stridor and abnormal movement of the diaphragm or mediastinum. Many procedures, such as needle aspiration or biopsy of a peripheral lesion, are also best accomplished with the aid of fluoroscopy, CT, or ultrasonography. Videotape recording, which does not increase radiation exposure, can allow detailed study during a brief exposure to fluoroscopy, through its replay capabilities.

Barium Swallow

A barium swallow study, performed with fluoroscopy and spot images is indicated in the evaluation of patients with recurrent pneumonia, persistent cough of undetermined cause, stridor, or persistent wheezing. The technique can be modified by using barium of different textures and thicknesses, ranging from thin liquid to solids, to evaluate swallowing mechanics, the presence of vascular rings (see Chapter 413 ), and tracheoesophageal fistulas (see Chapter 345 ), especially when aspiration is suspected. A contrast esophagram has been used in evaluating newborns with suggested esophageal atresia, but this procedure entails a high risk of pulmonary aspiration and is not usually recommended. Barium swallows are useful in evaluating suggested gastroesophageal reflux (see Chapter 349 ), but because of the high incidence of asymptomatic reflux in infants, the applicability of the findings to the clinical problem may be complicated.

Pulmonary Arteriography and Aortograms

Pulmonary arteriography has been used to allow detailed evaluation of the pulmonary vasculature. This imaging technique has also been helpful in assessing pulmonary blood flow and in diagnosing congenital anomalies, such as lobar agenesis, unilateral hyperlucent lung, vascular rings, and arteriovenous malformations. In addition, pulmonary arteriography is sometimes useful in evaluating solid or cystic lesions. Thoracic aortograms demonstrate the aortic arch, its major vessels, and the systemic (bronchial) pulmonary circulation. They are useful in evaluating vascular rings and suspected pulmonary sequestration. Although most hemoptysis is from the bronchial arteries, bronchial arteriography is seldom helpful in diagnosing or treating intrapulmonary bleeding in children. Real-time and Doppler echocardiography, as well as thoracic CT with contrast, are 2 noninvasive methods that often reveal similar information; therefore arteriography is now rarely performed.

Ventilation-Perfusion Relation and Radionuclide Lung Scans

Gravitational force pulls the lung away from the nondependent part of the parietal pleura. Consequently, alveoli and airways in the nondependent parts (the upper lobes in upright position) of the lung are subjected to greater negative intrapleural pressure during tidal respiration and are kept relatively more inflated compared with the dependent alveoli and airways (the lower lobes in upright position). The nondependent alveoli are less compliant because they are already more inflated. Ventilation therefore occurs preferentially in the dependent portions of the lung that are more amenable to expansion during tidal inspiration. Although perfusion is also greater in the dependent portions of the lung because of greater pulmonary arterial hydrostatic pressure from gravity, the increase in perfusion is greater than the increase in ventilation in the dependent portions of the lung. Thus the ratios favor ventilation in the nondependent portions and perfusion in the dependent portions. Because the airways in the dependent portion of the lung are narrower, they close earlier during expiration. The lung volume at which the dependent airways start to close is referred to as the closing capacity . In normal children, the FRC is greater than the closing capacity. During tidal respiration, airways remain patent both in the dependent and the nondependent portions of the lung. In newborns, the closing capacity is greater than the FRC, resulting in perfusion of poorly ventilated alveoli during tidal respiration. Therefore, normal neonates have a lower PaO 2 compared with older children.

The relationship is adversely affected in a variety of pathophysiologic states. Air movement in areas that are poorly perfused is referred to as dead space ventilation . Examples of dead space ventilation include pulmonary thromboembolism and hypovolemia. Perfusion of poorly ventilated alveoli is referred to as intrapulmonary right-to-left shunting or venous admixture . Examples include pneumonia, asthma, and hyaline membrane disease. In intrapulmonary airway obstruction, the closing capacity is abnormally increased and can exceed the FRC. In such situations, perfusion of poorly ventilated alveoli during tidal respiration results in venous admixture.

The usual scan uses intravenous injection of material (macroaggregated human serum albumin labeled with 99m Tc) that will be trapped in the pulmonary capillary bed. The distribution of radioactivity, proportional to pulmonary capillary blood flow, is useful in evaluating pulmonary embolism, as well as congenital cardiovascular and pulmonary defects. Acute changes in the distribution of pulmonary perfusion can reflect alterations of pulmonary ventilation.

The distribution of pulmonary ventilation can also be determined by scanning after the patient inhales a radioactive gas such as xenon-133. After the intravenous injection of xenon-133 dissolved in saline, pulmonary perfusion and ventilation can be evaluated by continuous recording of the rate of appearance and disappearance of the xenon over the lung. Appearance of xenon early after injection is a measure of perfusion, and the rate of washout during breathing is a measure of ventilation in the pediatric population. The most important indication for this test is the demonstration of defects in the pulmonary arterial distribution that can occur with congenital malformations or pulmonary embolism. Spiral reconstruction CT with contrast medium enhancement is very helpful in evaluating pulmonary thrombi and emboli. Abnormalities in regional ventilation are also easily demonstrable in congenital lobar emphysema, cystic fibrosis, and asthma.

Pulmonary Function Testing

Traditionally, lung volumes are measured with a spirogram (Fig. 400.8 ). Tidal volume (VT ) is the amount of air moved in and out of the lungs during each breath; at rest, VT is normally 6-7 mL/kg body weight. Inspiratory capacity is the amount of air inspired by maximum inspiratory effort after tidal expiration. Expiratory reserve volume is the amount of air exhaled by maximum expiratory effort after tidal expiration. The volume of gas remaining in the lungs after maximum expiration is residual volume. Vital capacity (VC) is defined as the amount of air moved in and out of the lungs through maximum inspiration and expiration. VC, inspiratory capacity, and expiratory reserve volume are decreased in lung pathology but are also effort dependent. Total lung capacity (TLC) is the volume of gas occupying the lungs after maximum inhalation.

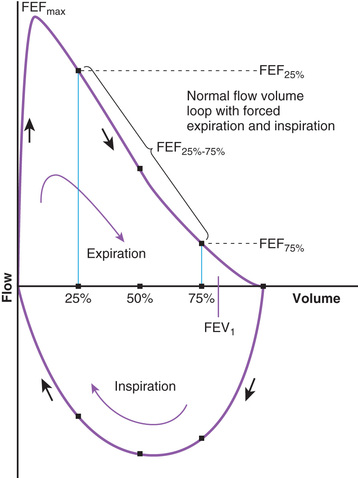

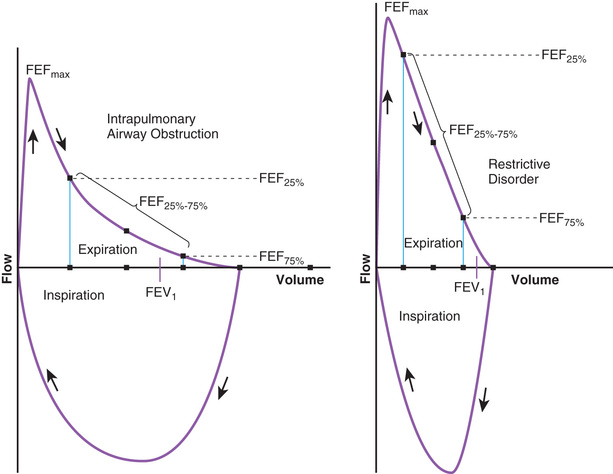

The flow volume relationship offers a valuable means at the bedside or in an office setting to detect abnormal pulmonary mechanics and response to therapy with relatively inexpensive and easy-to-use devices. After maximum inhalation, the patient forcefully exhales through a mouthpiece into the device until residual volume is reached, followed by maximum inhalation (Fig. 400.9 ). Flow is plotted against volume. Maximum forced expiratory flow (FEF max ) is generated in the early part of exhalation, and it is a commonly used indicator of airway obstruction in asthma and other obstructive lesions. Provided maximum pressure is generated consistently during exhalation, a decrease in flow is a reflection of increased airway resistance (RAW ). The total volume exhaled during this maneuver is forced vital capacity (FVC) . Volume exhaled in 1 sec is referred to as forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1 ) . FEV1 /FVC is expressed as a percentage of FVC. FEF25–75% is the mean flow between 25% and 75% of FVC, and is considered relatively effort independent. Individual values and shapes of flow-volume curves show characteristic changes in obstructive and restrictive respiratory disorders (Fig. 400.10 ). In intrapulmonary airway obstruction such as asthma or cystic fibrosis, there is a reduction of FEFmax , FEF25–75% , FVC, and FEV1 /FVC. Also, there is a characteristic concavity in the middle part of the expiratory curve. In restrictive lung disease such as interstitial pneumonia (see Chapter 327.5) and kyphoscoliosis (see Chapter 445.5 ), FVC is decreased with relative preservation of airflow and FEV1 /FVC. The flow volume curve assumes a vertically oblong shape compared with normal. Changes in shape of the flow volume loop and individual values depend on the type of disease and the extent of severity. Serial determinations provide valuable information regarding disease evolution and response to therapy.

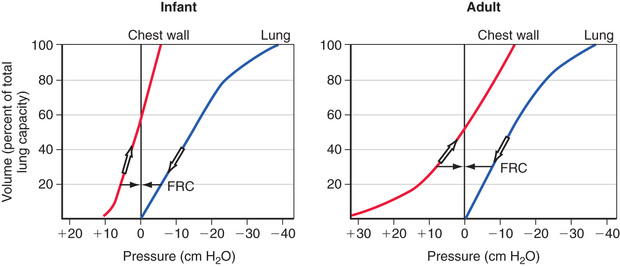

FRC has important pathophysiologic implications. Chest wall compliance is a major determinant of FRC. Because the chest wall and the lungs recoil in opposite directions at rest, FRC is reached at the point where the outward elastic recoil of the thoracic cage counterbalances the inward lung recoil. This balance is attained at a lower lung volume in a young infant's ribs because they are oriented much more horizontally and the diaphragm is flatter and less domed. Consequently, the infant is unable to duplicate the efficiency of upward and outward movement of obliquely oriented ribs or the downward displacement of a domed diaphragm in an adult to expand the thoracic capacity. This creates an extremely high thoracic compliance compared with older children and adults (Fig. 400.11 ). The measured FRC in infants is higher than expected because infant respiratory muscles maintain the thoracic cage in an inspiratory position at all times. In addition, young infants experience some amount of air trapping during expiration.

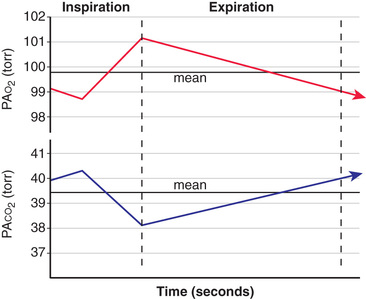

Alveolar gas composition changes during inspiration and expiration. Alveolar PO 2 (PAO 2 ) increases and alveolar PCO 2 (PACO 2 ) decreases during inspiration as fresh atmospheric gas enters the lungs. During exhalation, PAO 2 decreases and PACO 2 increases as pulmonary capillary blood continues to remove oxygen from and add CO2 into the alveoli (Fig. 400.12 ). FRC acts as a buffer, minimizing the changes in PAO 2 and PACO 2 during inspiration and expiration. FRC represents the environment available for pulmonary capillary blood for gas exchange at all times.

A decrease in FRC is often encountered in alveolar interstitial diseases and thoracic deformities. The major pathophysiologic consequence of decreased FRC is hypoxemia . Reduced FRC results in a sharp decline in PAO 2 during exhalation because a limited volume is available for gas exchange. PO 2 of pulmonary capillary blood therefore falls excessively during exhalation, leading to a decline in arterial PO 2 (PAO 2 ) . Any increase in PAO 2 (and therefore PaO 2 ) during inspiration cannot compensate for the decreased PaO 2 during expiration. The explanation for this lies in the shape of O2 -Hb dissociation curve, which is sigmoid shaped (see Fig. 400.5 ). Because most of the oxygen in blood is combined with Hb, it is the percentage of oxyhemoglobin (SO 2 ) that gets averaged rather than the PO 2 . Although an increase in arterial PO 2 cannot increase O2 -Hb saturation >100%, there is a steep desaturation of Hb below a PO 2 of 50 torr; thus decreased SO 2 during exhalation as a result of low FRC leads to overall arterial desaturation and hypoxemia. The adverse pathophysiologic consequences of decreased FRC are ameliorated by applying positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and increasing the inspiratory time during mechanical ventilation.

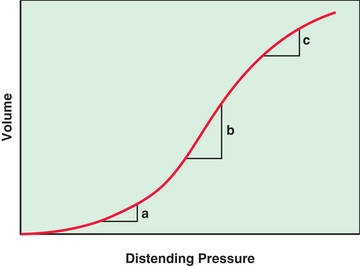

The lung pressure–volume relationship is markedly influenced by FRC (Fig. 400.13 ). Pulmonary compliance is decreased at abnormally low or high FRC.

FRC is abnormally increased in intrathoracic airway obstruction, which results in incomplete exhalation, and abnormally decreased in alveolar-interstitial diseases. At excessively low or high FRC, tidal respiration requires higher inflation pressures compared to normal FRC. Abnormalities of FRC result in increased work of breathing with spontaneous respiration and increased barotrauma in mechanical ventilation.

The measurement of respiratory function in infants and young children can be difficult because of the lack of cooperation. Attempts have been made to overcome this limitation by creating standard tests that do not require the patient's active participation. Respiratory function tests still provide only a partial insight into the mechanisms of respiratory disease at early ages.

Whether restrictive or obstructive, most forms of respiratory disease cause alterations in lung volume and its subdivisions. Restrictive diseases typically decrease TLC . TLC includes residual volume, which is not accessible to direct determinations. It must therefore be measured indirectly by gas dilution methods or, preferably, by plethysmography . Restrictive disease also decreases VC . Obstructive diseases produce gas trapping and thus increase residual volume and FRC, particularly when these measurements are considered with respect to TLC.

Airway obstruction is most commonly evaluated from determinations of gas flow in the course of a forced expiratory maneuver. The peak expiratory flow is reduced in advanced obstructive disease. The wide availability of simple devices that perform this measurement at the bedside makes it useful for assessing children who have airway obstruction. Evaluation of peak flows requires a voluntary effort, and peak flows may not be altered when the obstruction is moderate or mild. Other gas flow measurements require that the child inhale to TLC and then exhale as far and as fast as possible for several seconds. Cooperation and good muscle strength are therefore necessary for the measurements to be reproducible. FEV1 correlates well with the severity of obstructive diseases. The maximal midexpiratory flow rate , the average flow during the middle 50% of the forced VC, is a more reliable indicator of mild airway obstruction. Its sensitivity to changes in residual volume and VC, however, limits its use in children with more severe disease. The construction of flow-volume relationships during the forced VC maneuvers overcomes some of these limitations by expressing the expiratory flows as a function of lung volume.

A spirometer is used to measure VC and its subdivisions and expiratory (or inspiratory) flow rates (see Fig. 400.8 ). A simple manometer can measure the maximal inspiratory and expiratory force a subject generates, normally at least 30 cm H2 O. This is useful in evaluating the neuromuscular component of ventilation. Expected normal values for VC, FRC, TLC, and residual volume are obtained from prediction equations based on body height.

Flow rates measured by spirometry usually include the FEV1 and the maximal midexpiratory flow rate . More information results from a maximal expiratory flow-volume curve, in which expiratory flow rate is plotted against expired lung volume (expressed in terms of either VC or TLC). Flow rates at lung volumes less than approximately 75% VC are relatively independent of effort. Expiratory flow rates at low lung volumes (<50% VC) are influenced much more by small airways than flow rates at high lung volumes (FEV1 ). The flow rate at 25% VC is a useful index of small airway function. Low flow rates at high lung volumes associated with normal flow at low lung volumes suggest upper airway obstruction.

Airway resistance (RAW ) is measured in a plethysmograph, or alternatively, the reciprocal of RAW , airway conductance , may be used. Because RAW measurements vary with the lung volume at which they are taken, it is convenient to use specific airway resistance , SRAW (SRAW = RAW /lung volume), which is nearly constant in subjects older than age 6 yr (normally <7 sec/cm H2 O).

The diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide is related to oxygen diffusion and is measured by rebreathing from a container having a known initial concentration of carbon monoxide or by using a single-breath technique. Decreases in diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide reflect decreases in effective alveolar capillary surface area or decreases in diffusibility of the gas across the alveolar-capillary membrane. Primary diffusion abnormalities are unusual in children; therefore, this test is most commonly employed in children with rheumatologic or autoimmune diseases and in children exposed to toxic drugs to the lungs (e.g., oncology patients) or chest wall radiation. Regional gas exchange can be conveniently estimated with the perfusion-ventilation xenon scan. Determining arterial blood gas levels also discloses the effectiveness of alveolar gas exchange.

Pulmonary function testing, although rarely resulting in a diagnosis, is helpful in defining the type of process (obstruction, restriction) and the degree of functional impairment, in following the course and treatment of disease, and in estimating the prognosis. It is also useful in preoperative evaluation and in confirmation of functional impairment in patients having subjective complaints but a normal physical examination. In most patients with obstructive disease, a repeat test after administering a bronchodilator is warranted.

Most tests require some cooperation and understanding by the patient. Interpretation is greatly facilitated if the test conditions and the patient's behavior during the test are known. Infants and young children who cannot or will not cooperate with test procedures can be studied in a limited number of ways, which often require sedation. Flow rates and pressures during tidal breathing, with or without transient interruption of the flow, may be useful to assess some aspects of RAW or obstruction and to measure compliance of the lungs and thorax. Expiratory flow rates can be studied in sedated infants with passive compression of the chest and abdomen using a rapidly inflatable jacket. Gas dilution or plethysmographic methods can also be used in sedated infants to measure FRC and RAW .

The measurement of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) is used as a surrogate measure for eosinophilic inflammation of the lower airways. It can be used as a part of a diagnostic evaluation for asthma, a tool for predicting or assessing an individual's response to antiinflammatory therapy, and in monitoring adherence to treatment. There are a number of commercially available devices for measurement of FENO. Some degree of cooperation is required, but FENO has been measured in preschool-aged children. Normal cutoff values vary by age and device. FENO has been used to distinguish asthma (particularly allergic asthma) from other wheezing phenotypes. FENO achieves moderate diagnostic performance for the detection of asthma in children, with sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic odds ratios of 0.79, 0.81, and 16.52, respectively. Children managed using FENO may have fewer asthma exacerbations. A decrease of FENO by 20% is considered indicative of a positive response to antiinflammatory therapy. Some studies using FENO have contradictory results, and it is likely that FENO may be more useful in some asthma phenotypes than others.

The measurement of nasal nitric oxide (nNO) is accomplished by collecting exhaled gas from a nostril during glottic closure, and correlates to nasal mucosal inflammation. There is a great deal of interest in use of nNO to diagnose primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD, see Chapter 404 ), because of challenges diagnosing PCD with currently available techniques. A cutoff value of less than or equal to 77 nL/min showed excellent sensitivity and specificity using a standardized technique at multiple centers. The sensitivity and specificity of 0.95 and 0.94 is excellent. Equipment for measurement of nNO is not yet FDA-approved in the USA.

Microbiology: Examination of Lung Secretions

The specific diagnosis of infection in the lower respiratory tract depends on the proper handling of an adequate specimen obtained in an appropriate fashion. Nasopharyngeal or throat cultures are often used but might not correlate with cultures obtained by more direct techniques from the lower airways. Sputum specimens are preferred and are often obtained from patients who do not expectorate by deep throat swab immediately after coughing or by saline nebulization. Specimens can also be obtained directly from the tracheobronchial tree by nasotracheal aspiration (usually heavily contaminated), by transtracheal aspiration through the cricothyroid membrane (useful in adults and adolescents but hazardous in children), and in infants and children by a sterile catheter inserted into the trachea either during direct laryngoscopy or through a freshly inserted endotracheal tube. A specimen can also be obtained at bronchoscopy. A percutaneous lung tap or an open biopsy is the only way to obtain a specimen absolutely free of oral flora.

A specimen obtained by direct expectoration is usually assumed to be of tracheobronchial origin, but often, especially in children, it is not from this source. The presence of alveolar macrophages (large mononuclear cells) is the hallmark of tracheobronchial secretions. Nasopharyngeal and tracheobronchial secretions can contain ciliated epithelial cells, which are more commonly found in sputum. Nasopharyngeal and oral secretions often contain large numbers of squamous epithelial cells. Sputum can contain both ciliated and squamous epithelial cells.

During sleep, mucociliary transport continually brings tracheobronchial secretions to the pharynx, where they are swallowed. An early-morning fasting gastric aspirate often contains material from the tracheobronchial tract that is suitable for culture for acid-fast bacilli.

The absence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in a Wright-stained smear of sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid containing adequate numbers of macrophages may be significant evidence against a bacterial infectious process in the lower respiratory tract, assuming that the patient has normal neutrophil counts and function. Eosinophils suggest allergic disease. Iron stains can reveal hemosiderin granules within macrophages, suggesting pulmonary hemosiderosis. Specimens should also be examined by Gram stain. Bacteria within or near macrophages and neutrophils can be significant. Viral pneumonia may be accompanied by intranuclear or cytoplasmic inclusion bodies visible on Wright-stained smears, and fungal forms may be identifiable on Gram or silver stains.

With advances in the area of genomics and the speed with which it is possible to identify microbes, microbiologic analysis has been expanded. Specific bacteria in the lungs of children with cystic fibrosis (see Chapter 432 ) are linked to morbidity and mortality. There is a correlation between patient age and morbidity and mortality (as expected), but that there are important microbes that are correlated either negatively or positively with early or late pathogenic processes. Haemophilus influenzae (see Chapter 221 ) is negatively correlated, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (see Chapter 232.3 ) have a strong positive correlation with patient age in cystic fibrosis. The microbiota diversity is much broader in those who are healthier individuals or those who are younger patients with cystic fibrosis than the older and sicker population.

In addition, the microbiomes (see Chapter 196 ) in the respiratory tract of smokers and nonsmokers differ substantially. In all patients, most of the bacteria found in the lungs are also present in the oral cavity, but some bacteria, such as Haemophilus and enterobacteria, are much more represented in the lungs than in the mouth. Principal differences in microbiome composition between smokers and nonsmokers are found in the mouth. For example, Neisseria levels are much lower in smokers as compared with nonsmokers.

The Microbiome (see Chapter 196 )

Exercise Testing

Exercise testing (see Chapter 450.5 ) is a more-direct approach for detecting diffusion impairment and other forms of respiratory disease. Exercise is a strong provocateur of bronchospasm in susceptible patients, so exercise testing can be useful in the diagnosis of patients with asthma that is only apparent with activity. Measurements of heart and respiratory rate, minute ventilation, oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and arterial blood gases during incremental exercise loads often provide invaluable information about the functional nature of the disease. Often a simple assessment of the patient's exercise tolerance in conjunction with other, more static forms of respiratory function testing can allow a distinction between respiratory and nonrespiratory disease in children.

Sleep Studies

See Chapter 31 .

Airway Visualization and Lung Specimen–Based Diagnostic Tests

Laryngoscopy

The evaluation of stridor, problems with vocalization, and other upper airway abnormalities usually requires direct inspection. Although indirect (mirror) laryngoscopy may be reasonable in older children and adults, it is rarely feasible in infants and small children. Direct laryngoscopy may be performed with either a rigid or a flexible instrument. The safe use of the rigid scope for examining the upper airway requires topical anesthesia and either sedation or general anesthesia, whereas the flexible laryngoscope can often be used in the office setting with or without sedation. Further advantages to the flexible scope include the ability to assess the airway without the distortion that may be introduced by the use of the rigid scope and the ability to assess airway dynamics more accurately. Because there is a relatively high incidence of concomitant lesions in the upper and lower airways, it is often prudent to examine the airways above and below the glottis, even when the primary indication is in the upper airway (stridor).

Bronchoscopy and Bronchoalveolar Lavage

Bronchoscopy is the inspection of the airways. Flexible bronchoscopy is commonly used in pediatrics to visualize the airways. There are several sizes of scopes that enable visualization of the proximal and distal airways. Many fiberoptic bronchoscopes also have a channel that allows for the collection of fluids, or in larger scopes allows for the insertion of tools such as forceps, baskets, or brushes. The smallest scope is a 2.2 mm outer diameter bronchoscope that does not have a channel; therefore only visualization of the airways is possible. The smallest bronchoscope with a channel is a 2.8 mm outer diameter scope, which has a 1.2 mm working channel. This scope is commonly used in pediatrics and is predominately used to visualize the airways and to collect a lavage sample. In larger “adult” scopes (4.9-5.5 mm outer diameter and 2.0 mm working channel), small instruments such as forceps can be inserted. Therapeutic bronchoscopes require an even larger channel (2.8 mm working channel, which requires a larger outer diameter of 6.0-6.3 mm), so they are not used often in the pediatric population. A smaller scope (4.1 mm outer diameter) with a larger working channel (2.0 mm) has become available and may make interventional pediatric bronchoscopy more common in the future.

Visualization of the airway has improved through new advances in optics and insertable tools. Narrow-band imaging and autofluorescence imaging bronchoscopes are 2 types of bronchoscopes that can aid in the detection of airway lesions. These scopes appear no different than the conventional bronchoscope but utilize different bandwidths of lights to highlight mucosal and submucosal vasculature. These bronchoscopes allow the operator to see airway mucosal lesions that would be difficult or not seen under normal white light. The autofluorescence imaging bronchoscope uses the fluorophores, such as tryptophan, collagen, elastin and porphyrins, within the airway tissue to emit fluorescence when irradiated with a light source. Changes in concentrations of the fluorophores in bronchial mucosa would appear as an irregular lesion when viewed with an autofluorescence imaging bronchoscope. The narrow-band imaging bronchoscope also uses light absorption characteristics of Hb to enhance images of blood vessels. This bronchoscope uses blue wavelengths in the range of 390-445 nm to visualize the mucosal layer capillaries and green wavelengths at 530 and 550 nm to detect deeper submucosal thick blood vessels. Both types of bronchoscopes allow the operator to detect findings that would not be seen under normal white light. These scopes are being used more often in adults where lesions are biopsied to detect premalignant and malignant lesions. These scopes are noninvasive and would be well tolerated in children, but are currently only available in larger “adult” sizes.

The EBUS , endobronchial ultrasound , is a scope that allows ultrasound images to be captured from the tip of the scope and also contains a working channel to collect a needle biopsy. This technology is particularly useful in the evaluation of mediastinal lymph nodes. This scope may be useful in the diagnosis of other conditions such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and the staging of lung cancers. The EBUS is currently being investigated in older pediatric patients as an alternative to CT-guided transthoracic fine needle aspiration for the evaluation of mediastinal lymph nodes. EBUS has the benefit of no radiation, but has not been extensively studied in pediatrics.

Bronchial thermoplasty (BT) is a technology that can be used to treat patients with severe asthma. This technique uses the working channel of a fiberoptic bronchoscope to deliver targeted thermal energy to the airways to ablate the airway smooth muscle (ASM). The ablation of ASM may reduce the ability to bronchoconstrict. It may also impact the ASM's role in immunomodulation, ultimately altering the pathophysiology of asthma. BT requires a minimum of a 2.0 mm working channel, which limits this technology to bronchoscopes of at least an outer diameter of 4.1 mm. In general, BT is performed over 3 bronchoscopy sessions to ablate different sections of the lung: right lower lobe, left lower lobe, and bilateral upper lobes. The right middle lobe is usually not ablated for the potential risk of stenosis. The treatments are divided into 3 separate procedures to allow for shorter procedure times (30-60 min per session) and decrease the risk of widespread irritation. Patients are also given oral steroids for 3 days prior to the procedure to decrease airway inflammation associated with the ablation procedure. While BT is gaining momentum in the treatment of severe asthma in the adult population, the long-term ramifications of airway smooth muscle ablation in a child are still unknown. In adult studies that investigated BT as a therapeutic tool for asthma, small studies demonstrated an improvement in clinical symptoms, and in a smaller cohort of patients (12 patients), no significant structural abnormalities were seen on chest radiographs 5 yr after the procedure.

The most common diagnostic tool used in conjunction with fiberoptic bronchoscopy is bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) . BAL is a method used to obtain a representative specimen of fluid and secretions from the lower respiratory tract, which is useful for the cytologic and microbiologic diagnosis of lung diseases, especially in those who are unable to expectorate sputum. BAL is performed after the general inspection of the airways and before tissue sampling with a brush or biopsy forceps. It is accomplished by gently wedging the scope into a lobar, segmental, or subsegmental bronchus, and sequentially instilling and withdrawing sterile nonbacteriostatic saline in a volume sufficient to ensure that some of the aspirated fluid contains material that originated from the alveolar space. Nonbronchoscopic BAL can be performed in intubated patients by instilling and withdrawing saline through a catheter passed though the artificial airway and blindly wedged into a distal airway, although nonbronchoscopic BAL is less accurate and therefore has less-reliable results. In either case, the presence of alveolar macrophages documents that an alveolar sample has been obtained. Because the methods used to perform BAL involve passage of the equipment through the upper airway, there is a risk of contamination of the specimen by upper airway secretions. Careful cytologic examination and quantitative microbiologic cultures are important for correct interpretation of the data. BAL can often obviate the need for more-invasive procedures such as open lung biopsy, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Indications for diagnostic bronchoscopy and BAL include recurrent or persistent pneumonia or atelectasis, unexplained or localized and persistent wheeze, the suspected presence of a foreign body, hemoptysis, suspected congenital anomalies, mass lesions, interstitial disease, and pneumonia in the immunocompromised host. Indications for therapeutic bronchoscopy and BAL include bronchial obstruction by mass lesions, foreign bodies or mucus plugs, and general bronchial toilet and bronchopulmonary lavage. The patient undergoing bronchoscopy ventilates around the flexible scope, whereas with the rigid scope, ventilation is accomplished through the scope. Rigid bronchoscopy is preferentially indicated for extracting foreign bodies and removing tissue masses. It is also indicated in patients with massive hemoptysis. In other cases, the flexible scope has multiple advantages: it can be passed through endotracheal or tracheostomy tubes, can be introduced into bronchi that come off the airway at acute angles, and can be safely and effectively inserted with topical anesthesia and conscious sedation.

Regardless of the instrument used, the procedure performed, or the resulting indications, the most common complications are related to sedation. The relatively more common complications related to the bronchoscopy itself include transient hypoxemia, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and cardiac arrhythmias. Iatrogenic infection, bleeding, pneumothorax, and pneumomediastinum are rare but reported complications of bronchoscopy or BAL. Bronchoscopy in the setting of possible pulmonary abscess or hemoptysis must be undertaken with advance preparations for definitive airway control, mindful of the possibility that pus or blood might flood the airway. Subglottic edema is a more common complication of rigid bronchoscopy than of flexible procedures, in which the scopes are smaller and less likely to traumatize the mucosa. Postbronchoscopy croup is treated with oxygen, mist, vasoconstrictor aerosols, and corticosteroids as necessary.

Thoracoscopy

The pleural cavity can be examined through a thoracoscope, which is similar to a rigid bronchoscope. The thoracoscope is inserted through an intercostal space and the lung is partially deflated, allowing the operator to view the surface of the lung, the pleural surface of the mediastinum and the diaphragm, and the parietal pleura. Multiple thoracoscopic instruments can be inserted, allowing endoscopic biopsy of the lung or pleura, resection of blebs, abrasion of the pleura, and ligation of vascular rings.

Thoracentesis

For diagnostic or therapeutic purposes, fluid can be removed from the pleural space by needle. In general, as much fluid as possible should be withdrawn, and an upright chest roentgenogram should be obtained after the procedure. Complications of thoracentesis include infection, pneumothorax, and bleeding. Thoracentesis on the right may be complicated by puncture or laceration of the capsule of the liver and, on the left, by puncture or laceration of the capsule of the spleen. Specimens obtained should always be cultured, examined microscopically for evidence of bacterial infection, and evaluated for total protein and total differential cell counts. Lactic acid dehydrogenase, glucose, cholesterol, triglyceride (chylous), and amylase determinations may also be useful. If malignancy is suspected, cytologic examination is imperative.

Transudates result from mechanical factors influencing the rate of formation or reabsorption of pleural fluid and generally require no further diagnostic evaluation. Exudates result from inflammation or other disease of the pleural surface and underlying lung, so they require a more complete diagnostic evaluation. In general, transudates have a total protein of <3 g/dL or a ratio of pleural protein to serum protein <0.5, a total leukocyte count of fewer than 2,000/mm3 with a predominance of mononuclear cells, and low lactate dehydrogenase levels. Exudates have high protein levels and a predominance of polymorphonuclear cells (although malignant or tuberculous effusions can have a higher percentage of mononuclear cells). Complicated exudates often require continuous chest tube drainage and have a pH <7.2. Tuberculous effusions can have low glucose and high cholesterol content.

Lung Tap

Using a technique similar to that used for thoracentesis, a percutaneous lung tap is the most direct method of obtaining bacteriologic specimens from the pulmonary parenchyma and is the only technique other than open lung biopsy not associated with at least some risk of contamination by oral flora. After local anesthesia, a needle attached to a syringe containing nonbacteriostatic sterile saline is inserted using aseptic technique through the inferior aspect of an intercostal space in the area of interest. The needle is rapidly advanced into the lung; the saline is injected and reaspirated, and the needle is withdrawn. These actions are performed as quickly as possible. This procedure usually yields a few drops of fluid from the lung, which should be cultured and examined microscopically.

Major indications for a lung tap are infiltrates of undetermined cause, especially those unresponsive to therapy in immunosuppressed patients who are susceptible to unusual organisms. Complications are the same as for thoracentesis, but the incidence of pneumothorax is higher and somewhat dependent on the nature of the underlying disease process. In patients with poor pulmonary compliance, such as children with Pneumocystis pneumonia, the rate can approach 30%, with 5% requiring chest tubes. Bronchopulmonary lavage has replaced lung taps for most purposes.

Lung Biopsy

Lung biopsy may be the only way to establish a diagnosis, especially in protracted, noninfectious disease. In infants and small children, thoracoscopic or open surgical biopsies are the procedures of choice, and in expert hands there is low morbidity. Biopsy through the 3.5 mm diameter pediatric bronchoscopes limits the sample size and diagnostic abilities. In addition to ensuring that an adequate specimen is obtained, the surgeon can inspect the lung surface and choose the site of biopsy. In older children, transbronchial biopsies can be performed using flexible forceps through a bronchoscope, an endotracheal tube, a rigid bronchoscope, or an endotracheal tube, usually with fluoroscopic guidance. This technique is most appropriately used when the disease is diffuse, as in the case of Pneumocystis pneumonia, or after rejection of a transplanted lung. The diagnostic limitations related to the small size of the biopsy specimens can be mitigated by the ability to obtain several samples. The risk of pneumothorax related to bronchoscopy is increased when transbronchial biopsies are part of the procedure; however, the ability to obtain biopsy specimens in a procedure performed with topical anesthesia and conscious sedation offers is advantageous.

Sweat Testing

See Chapter 432 .