Congenital Disorders of the Nose

Joseph Haddad Jr, Sonam N. Dodhia

Normal Newborn Nose

In contrast to children and adults who preferentially breathe through their nose unless nasal obstruction interferes, most newborn infants are obligate nasal breathers. Significant nasal obstruction presenting at birth, such as choanal atresia, may be a life-threatening situation for the infant unless an alternative to the nasal airway is established. Nasal congestion with obstruction is common in the 1st year of life and can affect the quality of breathing during sleep; it may be associated with a narrow nasal airway, viral or bacterial infection, enlarged adenoids, or maternal estrogenic stimuli similar to rhinitis of pregnancy. The internal nasal airway doubles in size in the 1st 6 mo of life, leading to resolution of symptoms in many infants. Supportive care with a bulb syringe and saline nose drops, topical nasal decongestants, and antibiotics, when indicated, improve symptoms in affected infants.

Physiology

The nose is responsible for the initial warming and humidification of inspired air and olfaction. In the anterior nasal cavity, turbulent airflow and coarse hairs enhance the deposition of large particulate matter; the remaining nasal airways filter out particles as small as 6 µm in diameter. In the turbinate region, the airflow becomes laminar and the airstream is narrowed and directed superiorly, enhancing particle deposition, warming, and humidification. Nasal passages contribute as much as 50% of the total resistance of normal breathing. Nasal flaring, a sign of respiratory distress, reduces the resistance to inspiratory airflow through the nose and can improve ventilation (see Chapter 400 ).

Although the nasal mucosa is more vascular (especially in the turbinate region) than in the lower airways, the surface epithelium is similar, with ciliated cells, goblet cells, submucosal glands, and a covering blanket of mucus. The nasal secretions contain lysozyme and secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA), both of which have antimicrobial activity, and IgG, IgE, albumin, histamine, bacteria, lactoferrin, and cellular debris, as well as mucous glycoproteins, which provide viscoelastic properties. Aided by the ciliated cells, mucus flows toward the nasopharynx, where the airstream widens, the epithelium becomes squamous, and secretions are wiped away by swallowing. Replacement of the mucous layers occurs about every 10-20 min. Estimates of daily mucus production vary from 0.1 to 0.3 mg/kg/24 hr, with most of the mucus being produced by the submucosal glands.

Congenital Disorders

Congenital structural nasal malformations are uncommon compared with acquired abnormalities. The nasal bones can be congenitally absent so that the bridge of the nose fails to develop, resulting in nasal hypoplasia. Congenital absence of the nose (arhinia), complete or partial duplication, or a single centrally placed nostril can occur in isolation but is usually part of a malformation syndrome. Rarely, supernumerary teeth are found in the nose, or teeth grow into it from the maxilla.

Nasal bones can be sufficiently malformed to produce severe narrowing of the nasal passages. Often, such narrowing is associated with a high and narrow hard palate. Children with these defects can have significant obstruction to airflow during infections of the upper airways and are more susceptible to the development of chronic or recurrent hypoventilation (see Chapter 31 ). Rarely, the alae nasi are sufficiently thin and poorly supported to result in inspiratory obstruction, or there may be congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction with cystic extension into the nasopharynx, causing respiratory distress.

Choanal Atresia

This is the most common congenital anomaly of the nose and has a frequency of approximately 1 in 7,000 live births. It consists of a unilateral or bilateral bony (90%) or membranous (10%) septum between the nose and the pharynx; most cases are a combination of bony and membranous atresia. The pathogenesis is unknown, but theories include persistence of the buccopharyngeal membranes or failure of the oronasal membrane to rupture. The unilateral defect is more common and the female:male ratio is approximately 2 : 1. Approximately 50–70% of affected infants have other congenital anomalies (CHARGE syndrome [see later], Treacher-Collins, Kallmann syndrome, VATER [vertebral defects, imperforate anus, tracheoesophageal fistula, and renal defects] association, Pfeiffer syndrome), with the anomalies occurring more often in bilateral cases.

The CHARGE syndrome (c oloboma, h eart disease, a tresia or stenosis of the choanae, r etarded growth and development or central nervous system (CNS) anomalies or both, g enital anomalies or hypogonadism or both, and e ar [external, middle, inner ear] anomalies or deafness or both) is one of the more common anomalies associated with choanal atresia—approximately 10–20% of patients with choanal atresia have it. The CNS involvement (~90%) includes reduced function of cranial nerves I, V, VII, VIII, IX, and X, as well as vision and hearing deficits. Most (~90%) patients with CHARGE syndrome have autosomal dominant de novo mutations in the CHD7 gene, which is involved in chromatin organization. Immunologic deficiencies may be noted that overlap with the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome.

Clinical Manifestations

Newborn infants have a variable ability to breathe through their mouths, so nasal obstruction does not produce the same symptoms in every infant. When the obstruction is unilateral, the infant may be asymptomatic for a prolonged period, often until the first respiratory infection, when unilateral nasal discharge or persistent nasal obstruction can suggest the diagnosis. Infants with bilateral choanal atresia who have difficulty with mouth breathing make vigorous attempts to inspire, often suck in their lips, and develop cyanosis. Distressed children then cry (which relieves the cyanosis) and become calmer, with normal skin color, only to repeat the cycle after closing their mouths. Those who are able to breathe through their mouths at once experience difficulty when sucking and swallowing, becoming cyanotic when they attempt to feed.

Diagnosis

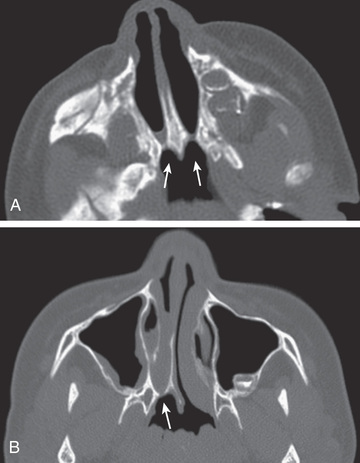

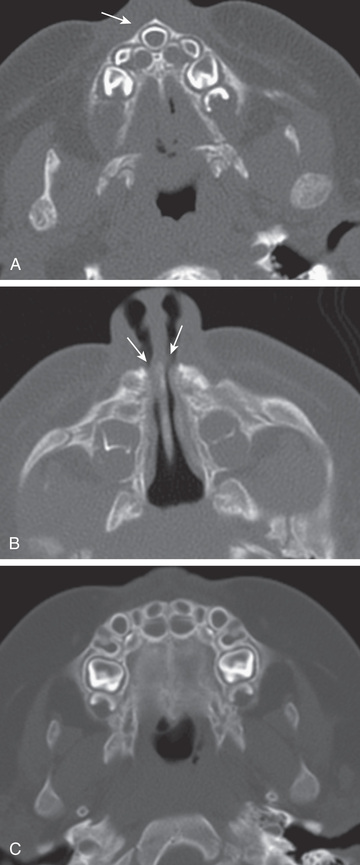

Diagnosis is established by the inability to pass a firm catheter through each nostril 3-4 cm into the nasopharynx. The atretic plate may be seen directly with fiberoptic rhinoscopy. The anatomy is best evaluated by using high-resolution CT (Fig. 404.1 ).

Treatment

Initial treatment consists of prompt placement of an oral airway, maintaining the mouth in an open position, or intubation. A standard oral airway (such as that used in anesthesia) can be used, or a feeding nipple can be fashioned with large holes at the tip to facilitate air passage. Once an oral airway is established, the infant can be fed by gavage until breathing and eating without the assisted airway is possible. In bilateral cases, intubation or, less often, tracheotomy may be indicated. If the child is free of other serious medical problems, operative intervention is considered in the neonate; transnasal repair is the treatment of choice, with the introduction of small magnifying endoscopes and smaller surgical instruments and drills. Stents are usually left in place for weeks after the repair to prevent closure or stenosis, although a large meta-analysis demonstrated that there is no benefit to stenting. Another option is a transpalatal repair, and this is done when a transnasal endoscope cannot be placed through the nose due to thick bony atresia or stenosis. Tracheotomy should be considered in cases of bilateral atresia in which the child has other potentially life-threatening problems and in whom early surgical repair of the choanal atresia may not be appropriate or feasible. Operative correction of unilateral obstruction may be deferred for several years. In both unilateral and bilateral cases, restenosis necessitating dilation or reoperation, or both, is common. Mitomycin C has been used to help prevent the development of granulation tissue and stenosis, although its efficacy is questionable.

Congenital Defects of the Nasal Septum

Perforation of the septum is most commonly acquired after birth secondary to infection, such as syphilis or tuberculosis, or trauma; rarely, it is developmental. Continuous positive airway pressure cannulas are a cause of iatrogenic perforation. Trauma from delivery is the most common cause of septal deviation noted at birth. When recognized early, it can be corrected with immediate realignment using blunt probes, cotton applicators, and topical anesthesia. Formal surgical correction, when required, is usually postponed to avoid disturbance of midface growth.

Mild septal deviations are common and usually asymptomatic; abnormal formation of the septum is uncommon unless other malformations are present, such as cleft lip or palate.

Congenital isolated absence of a membranous nasal septum has also been reported.

Pyriform Aperture Stenosis

Infants with this bony abnormality of the anterior nasal aperture present at birth or shortly thereafter with severe nasal obstruction leading to noisy breathing and respiratory distress that worsen with feeding and improve with crying. It can occur in isolation or in association with other malformations including holoprosencephaly, hypopituitarism, and cardiac and urogenital malformations. Diagnosis is made by CT of the nose (Fig. 404.2 ) with a pyriform aperture width less than ~11 mm. Medical management (nasal decongestants, humidification, nasopharyngeal airway insertion, management of reflux) is typically attempted for about 2 wk; if the child still cannot feed or breathe without difficulty, then surgical repair by means of an anterior, sublabial approach may be needed. A drill is used to enlarge the stenotic anterior bone apertures.

mo old infant with episodes of respiratory distress during breastfeeding.

A,

Axial CT image shows a triangular hard palate and solitary central maxillary mega-incisor (arrow)

. B,

An axial CT image shows narrowing of the anterior and inferior nasal passages (arrows).

C,

Normal infant maxilla for comparison.

(From Coley BD (ed): Caffey's pediatric diagnostic imaging,

ed 12, vol 1, Philadelphia, 2013, Saunders, Fig. 8.14.)

mo old infant with episodes of respiratory distress during breastfeeding.

A,

Axial CT image shows a triangular hard palate and solitary central maxillary mega-incisor (arrow)

. B,

An axial CT image shows narrowing of the anterior and inferior nasal passages (arrows).

C,

Normal infant maxilla for comparison.

(From Coley BD (ed): Caffey's pediatric diagnostic imaging,

ed 12, vol 1, Philadelphia, 2013, Saunders, Fig. 8.14.)

Congenital Midline Nasal Masses

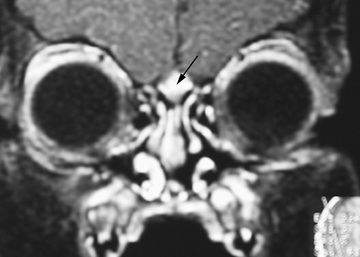

Dermoids, gliomas, and encephaloceles (in descending order of frequency) occur intranasally or extranasally and can have intracranial connections or extend intracranially with communication to the subarachnoid space. The theory for the embryologic development of congenital midline nasal masses is faulty retraction of the dural diverticulum. Dermoids and epidermoids are the most common type of congenital midline nasal mass and have been reported to represent up to 61% of lesions. Nasal dermoids are firm, noncompressible, and painless, and often have a dimple or pit on the nasal dorsum (sometimes with hair being present). They can predispose to intracranial infections if an intracranial fistula or sinus is present, although recurrent infection of the dermoid itself is more common; given the risk for serious infection, surgical excision is always indicated for nasal dermoids. Gliomas or heterotopic brain tissue are firm, whereas encephaloceles are soft and enlarge with crying or the Valsalva maneuver. Diagnosis is based on physical examination findings and results from imaging studies. CT provides the best bony detail, but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also helpful because of its superior ability to define intracranial extension (Fig. 404.3 ). Surgical excision of these masses is generally required, with the extent and surgical approach based on the type and size of the mass.

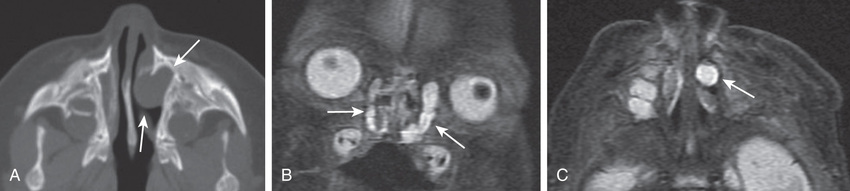

Other nasal masses include hemangiomas, congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (which can occur as an intranasal mass) (Fig. 404.4 ), nasal polyps, and tumors such as rhabdomyosarcoma (see Chapter 527 ). Nasal polyps are rarely present at birth, but the other masses often present at birth or in early infancy (see Chapter 406 ).

Poor development of the paranasal sinuses and a narrow nasal airway are associated with recurrent or chronic upper airway infection in Down syndrome (see Chapter 98.2 ).

Diagnosis and Treatment

In children with congenital nasal disorders, supportive care of the airway is given until the diagnosis is established. Diagnosis is made through a combination of flexible scoping and imaging studies, primarily CT scan. In the case of surgically correctable congenital problems such as choanal atresia, surgery is performed after the child is deemed healthy and free of life-threatening problems such as congenital heart disease.