Sleep Medicine

Judith A. Owens

Basics of Sleep and Chronobiology

Sleep, with its counterpart of wakefulness, is a highly complex and intricately regulated neurobiologic system that both influences and is influenced by all physiologic systems in the body, as well as by the environment and sociocultural practices. The concept of sleep regulation is based on what is usually referred to as the “2-process model” because it requires the simultaneous operation of 2 basic, highly coupled processes that govern sleep and wakefulness. The homeostatic process (“Process S”), regulates the length and depth of sleep and is thought to be related to the accumulation of adenosine and other sleep-promoting chemicals (“somnogens”), such as cytokines, during prolonged periods of wakefulness. This sleep pressure appears to build more quickly in infants and young children, thus limiting the duration that wakefulness can be sustained during the day and necessitating periods of daytime sleep (i.e., naps). The endogenous circadian rhythms (“Process C”) influence the internal organization of sleep and the timing and duration of daily sleep–wake cycles and govern predictable patterns of alertness throughout the 24 hr day.

The “master circadian clock” that controls sleep–wake patterns, of which melatonin secretion is the principal biomarker, is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the ventral hypothalamus. In addition, “circadian clocks” are present in virtually every cell in the body, which in turn govern the timing of multiple other physiologic systems (e.g., cardiovascular reactivity, hormone levels, renal and pulmonary functions). Because the human circadian clock is slightly longer than 24 hr, intrinsic circadian rhythms must be synchronized or “entrained” to the 24 hr day cycle by environmental cues called zeitgebers. The dark–light cycle is the most powerful of the zeitgebers; light signals are transmitted to the suprachiasmatic nucleus via the circadian photoreceptor system within the retina (functionally and anatomically separate from the visual system), which switch the pineal gland's production of the hormone melatonin off (light) or on (dark). Circadian rhythms are also synchronized by other external time cues, such as timing of meals and alarm clocks.

Sleep propensity, the relative level of sleepiness or alertness experienced at any given time during a 24 hr period, is partially determined by the homeostatic sleep drive , which in turn depends on the duration and quality of previous sleep and the amount of time awake since the last sleep period. Interacting with this sleep homeostat is the 24 hr cyclic pattern or rhythm characterized by clock-dependent periods of maximum sleepiness (circadian troughs ) and maximum alertness (circadian nadirs ). There are two periods of maximum sleepiness, one in the late afternoon (approximately 3:00-5:00 PM ) and one toward the end of the night (around 3:00-5:00 AM ), and two periods of maximum alertness, one in mid-morning and one in the evening just before the onset of natural sleep, the so-called forbidden zone or second-wind phenomenon, which allows for the maintenance of wakefulness in the face of accumulated sleep drive.

There are significant health, safety, and performance consequences of failure to meet basic sleep needs, termed insufficient/inadequate sleep or sleep loss . Sufficient sleep is a biologic imperative, necessary for optimal brain and body functioning. Slow-wave sleep (SWS) (i.e., N3, delta, or deep sleep) appears to be the most restorative form of sleep; it is entered relatively quickly after sleep onset, is preserved in the face of reduced total sleep time, and increases (rebounds) after a night of restricted sleep. These restorative properties of sleep may be linked to the “glymphatic system,” which increases clearance of metabolic waste products, including β-amyloid, produced by neural activity in the awake brain. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (stage R or “dream” sleep) appears to be involved in numerous important brain processes, including completion of vital cognitive functions (e.g., consolidation of memory), promoting the plasticity of the central nervous system (CNS), and protecting the brain from injury. Sufficient amounts of these sleep stages are necessary for optimal cognitive functioning and emotional and behavioral self-regulation.

Partial sleep loss (i.e., sleep restriction) on a chronic basis accumulates in a sleep debt and over several days produces deficits equivalent to those seen under conditions of 1 night of total sleep deprivation. If the sleep debt becomes large enough and is not voluntarily repaid by obtaining sufficient recovery sleep, the body may respond by overriding voluntary control of wakefulness. This results in periods of decreased alertness, dozing off, and unplanned napping, recognized as excessive daytime sleepiness. The sleep-restricted individual may also experience very brief (several seconds) repeated daytime microsleeps, of which the individual may be completely unaware, but which nonetheless may result in significant lapses in attention and vigilance. There is also a relationship between the amount of sleep restriction and performance on cognitive tasks, particularly those requiring sustained attention and higher-level cognitive skills (executive functions ; see Chapter 48 ), with a decay in performance correlating with declines in sleep amounts.

It has also been increasingly recognized that what may be globally described as “deficient” sleep involves alterations in both amount and timing of sleep. Misalignment of intrinsic circadian rhythms with extrinsic societal demands, such a shift work and early school start times, is associated with deficits in cognitive function and self-regulation, increased emotional and behavioral problems and risk-taking behaviors, and negative impacts on health, such as increased risk of cardiovascular disease, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction.

Insufficient quantity of sleep, mistimed sleep, and poor-quality sleep in children and adolescents frequently result in excessive daytime sleepiness and decreased daytime alertness levels. Sleepiness in children may be recognizable as drowsiness, yawning, and other classic “sleepy behaviors,” but can also manifest as mood disturbance, including complaints of moodiness, irritability, emotional lability, depression, and anger; fatigue and daytime lethargy, including increased somatic complaints (headaches, muscle aches); cognitive impairment, including problems with memory, attention, concentration, decision-making, and problem solving; daytime behavior problems, including hyperactivity, impulsivity, and noncompliance; and academic problems, including chronic tardiness related to insufficient sleep and school failure resulting from chronic daytime sleepiness.

Developmental Changes in Sleep

Sleep disturbances, as well as many characteristics of sleep itself, have some distinctly different features in children from sleep and sleep disorders in adults. Changes in sleep architecture and the evolution of sleep patterns and behaviors reflect the physiologic/chronobiologic, developmental, and social/environmental changes that are occurring across childhood. These trends may be summarized as the gradual assumption of more adult sleep patterns as children mature:

- 1. Sleep is the primary activity of the brain during early development; for example, by age 2 yr, the average child has spent 9500 hr (approximately 13 mo) asleep vs 8000 hr awake, and between 2 and 5 yr, the time asleep is equal to the time awake.

- 2. There is a gradual decline in the average 24 hr sleep duration from infancy through adolescence, which involves a decrease in both diurnal and nocturnal sleep amounts. The decline in daytime sleep (scheduled napping) results in termination of naps typically by age 5 yr. There is also a gradual continued decrease in nocturnal sleep amounts into late adolescence; however, the typical adolescent still requires 8-10 hr of sleep per night.

- 3. There is also a decline in the relative percentage of REM sleep from birth (50% of sleep) through early childhood into adulthood (25–30%), and a similar initial predominance of SWS that peaks in early childhood, drops off abruptly after puberty (40–60% decline), and then further decreases over the life span. This SWS preponderance in early life has clinical significance; for example, the high prevalence of partial arousal parasomnias (sleepwalking and sleep terrors) in preschool and early school-age children is related to the relative increased percentage of SWS in this age-group.

- 4. The within-sleep ultradian cycle lengthens from about 50 min in the term infant to 90-110 min in the school-age child. This has clinical significance in that typically a brief arousal or awakening occurs during the night at the termination of each ultradian cycle. As the length of the cycles increase, there is a concomitant decrease in the number of these end-of-cycle arousals (night wakings).

- 5. A gradual shift in the circadian sleep–wake rhythm to a delayed (later) sleep onset and offset time, linked to pubertal stage rather than chronological age, begins with pubertal onset in middle childhood and accelerates in early to mid-adolescence. This biologic phenomenon often coincides with environmental factors, which further delay bedtime and advance wake time and result in insufficient sleep duration, including exposure to electronic “screens” (television, computer) in the evening, social networking, academic and extracurricular demands, and early (before 8:30 AM ) high school start times.

- 6. Increasing irregularity of sleep–wake patterns is typically observed across childhood into adolescence; this is characterized by increasingly larger discrepancies between school night and non–school night bedtimes and wake times, and increased “weekend oversleep” in an attempt to compensate for chronic weekday sleep insufficiency. This phenomenon, often referred to as “social jet lag,” not only fails to adequately address performance deficits associated with insufficient sleep on school nights, but further exacerbates the normal adolescent phase delay and results in additional circadian disruption (analogous to that experienced by shift workers).

Table 31.1 lists normal developmental changes in children's sleep.

Table 31.1

Normal Developmental Changes in Children's Sleep

| AGE CATEGORY | SLEEP DURATION* AND SLEEP PATTERNS | ADDITIONAL SLEEP ISSUES | SLEEP DISORDERS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn (0-2 mo) |

Total sleep: 10-19 hr per 24 hr (average, 13-14.5 hr), may be higher in premature babies Bottle-fed babies generally sleep for longer periods (2-5 hr bouts) than breastfed babies (1-3 hr). Sleep periods are separated by 1-2 hr awake. No established nocturnal-diurnal pattern in 1st few wk; sleep is evenly distributed throughout the day and night, averaging 8.5 hr at night and 5.75 hr during day. |

American Academy of Pediatrics issued a revised recommendation in 2016 advocating against bed-sharing in the 1st yr of life, instead encouraging proximate but separate sleeping surfaces for mother and infant for at least the 1st 6 mo and preferably 1st yr of life. Safe sleep practices for infants: • Place baby on his or her back to sleep at night and during nap times. • Place baby on a firm mattress with well-fitting sheet in safety-approved crib. • Do not use pillows or comforters. •

Standards require crib bars to be no farther apart than • Make sure baby's face and head stay uncovered and clear of blankets and other coverings during sleep. |

Most sleep issues perceived as problematic at this stage represent a discrepancy between parental expectations and developmentally appropriate sleep behaviors. Newborns who are extremely fussy and persistently difficult to console, as noted by parents, are more likely to have underlying medical issues such as colic, gastroesophageal reflux, and formula intolerance. |

| Infant (2-12 mo) | Recommended sleep duration (4-12 mo) is 12-16 hr (note that there is great individual variability in sleep times during infancy). |

Sleep regulation or self-soothing involves the infant's ability to negotiate the sleep–wake transition, both at sleep onset and following normal awakenings throughout the night. The capacity to self-soothe begins to develop in the 1st 12 wk of life and is a reflection of both neurodevelopmental maturation and learning. Sleep consolidation, or “sleeping through the night,” is usually defined by parents as a continuous sleep episode without the need for parental intervention (e.g., feeding, soothing) from the child's bedtime through the early morning. Infants develop the ability to consolidate sleep between 6 wk and 3 mo. |

Behavioral insomnia of childhood; sleep-onset association type Sleep-related rhythmic movements (head banging, body rocking) |

| Toddler (1-2 yr) |

Recommended sleep amount is 11-14 hr (including naps). Naps decrease from 2 to 1 nap at average age of 18 mo. |

Cognitive, motor, social, and language developmental issues impact sleep. Nighttime fears develop; transitional objects and bedtime routines are important. |

Behavioral insomnia of childhood, sleep-onset association type Behavioral insomnia of childhood, limit-setting type |

| Preschool (3-5 yr) |

Recommended sleep amount is 10-13 hr (including naps). Overall, 26% of 4 yr olds and just 15% of 5 yr olds nap. |

Persistent cosleeping tends to be highly associated with sleep problems in this age-group. | Behavioral insomnia of childhood, limit-setting type |

| Sleep problems may become chronic. | Sleepwalking, sleep terrors, nighttime fears/nightmares, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome | ||

| Middle childhood (6-12 yr) | Recommended sleep amount is 9-12 hr. | School and behavior problems may be related to sleep problems. | Nightmares |

|

Media and electronics, such as television, computer, video games, and the Internet, increasingly compete for sleep time. Irregularity of sleep–wake schedules reflects increasing discrepancy between school and non–school night bedtimes and wake times. |

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome | ||

| Insufficient sleep | |||

| Adolescence (13-18 yr) |

Recommended sleep amount is 8-10 hr. Later bedtimes; increased discrepancy between sleep patterns on weekdays and weekends |

Puberty-mediated phase delay (later sleep onset and wake times), relative to sleep-wake cycles in middle childhood Earlier required wake times Environmental competing priorities for sleep |

Insufficient sleep Delayed sleep–wake phase disorder Narcolepsy Restless legs syndrome/periodic limb movement disorder |

* All recommended sleep amounts from Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D'Ambrosio C, et al: Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 12:785–786, 2016.

Common Sleep Disorders

Childhood sleep problems may be conceptualized as resulting from (1) inadequate duration of sleep for age and sleep needs (insufficient sleep quantity); (2) disruption and fragmentation of sleep (poor sleep quality) as a result of frequent, repetitive, and brief arousals during sleep; and (3) misalignment of sleep–wake timing with circadian rhythms or CNS-mediated hypersomnia (excessive daytime sleepiness and increased sleep needs). Insufficient sleep is usually the result of difficulty initiating (delayed sleep onset ) or maintaining sleep (prolonged night wakings ), but, especially in older children and adolescents, may also represent a conscious lifestyle decision to sacrifice sleep in favor of competing priorities, such as homework and social activities. The underlying causes of delayed sleep onset/prolonged night wakings or sleep fragmentation may in turn be related to primarily behavioral factors (e.g., bedtime resistance resulting in shortened sleep duration) or medical causes (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea causing frequent, brief arousals).

Certain pediatric populations are relatively more vulnerable to acute or chronic sleep problems. These include children with medical problems, such as chronic illnesses or pain conditions (e.g., cystic fibrosis, asthma, idiopathic juvenile arthritis) and acute illnesses (e.g., otitis media); children taking stimulants s (e.g., psychostimulants, caffeine), sleep-disrupting medications (e.g., corticosteroids), or daytime-sedating medications (some anticonvulsants, α-agonists); hospitalized children; and children with a variety of psychiatric disorders, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders. Children with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism, intellectual disability, blindness, and some chromosomal syndromes (e.g., Smith-Magenis, fragile X) have especially high rates of sleep disturbances for a wide variety of reasons. They may have comorbid medical issues or may be taking sleep-disrupting medications, may be more prone to nocturnal seizures, may be less easily entrained by environmental cues and thus more vulnerable to circadian disruption, and are more likely to have psychiatric and behavioral comorbidities that further predispose them to disrupted sleep.

Insomnia of Childhood

Insomnia is defined as difficulty initiating and/or maintaining sleep that occurs despite age-appropriate time and opportunity for sleep and results in some degree of impairment in daytime functioning for the child and/or family (ranging from fatigue, irritability, lack of energy, and mild cognitive impairment to effects on mood, school performance, and quality of life). Insomnia may be of a short-term and transient nature (usually related to an acute event) or may be characterized as long-term and chronic. Insomnia is a set of symptoms with many possible etiologies (e.g., pain, medication, medical/psychiatric conditions, learned behaviors). As with many behavioral issues in children, insomnia is often primarily defined by parental concerns rather than by objective criteria, and therefore should be viewed in the context of family (maternal depression, stress), child (temperament, developmental level), and environmental (cultural practices, sleeping space) considerations.

While current terminology (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, 2015; International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition, 2014) groups most types of insomnia in both children and adults under a single category of Chronic Insomnia Disorder, the descriptor of Behavioral Insomnia of Childhood and its subtypes (Sleep Onset Association and Limit Setting) remains a useful construct, particularly for young children (0-5 yr) in clinical practice. One of the most common presentations of insomnia found in infants and toddlers is the sleep-onset association type. In this situation the child learns to fall asleep only under certain conditions or associations, which typically require parental presence, such as being rocked or fed, and does not develop the ability to self-soothe. During the night, when the child experiences the type of brief arousal that normally occurs at the end of an ultradian sleep cycle or awakens for other reasons, the child is not able to get back to sleep without those same associations being present. The infant then “signals” the parent by crying (or coming into the parents' bedroom, if the child is ambulatory) until the necessary associations are provided. The presenting complaint is typically one of prolonged night waking requiring caregiver intervention and resulting in insufficient sleep (for both child and parent).

Management of night wakings should include establishment of a set sleep schedule and bedtime routine and implementation of a behavioral program. The treatment approach typically involves a program of rapid withdrawal (extinction) or more gradual withdrawal (graduated extinction) of parental assistance at sleep onset and during the night. Extinction (“cry it out”) involves putting the child to bed at a designated bedtime, “drowsy but awake,” to maximize sleep propensity and then systematically ignoring any protests by the child until a set time the next morning. Although it has considerable empirical support, extinction is often not an acceptable choice for families. Graduated extinction involves gradually weaning the child from dependence on parental presence; typically, the parent leaves the room at “lights out” and then returns or “checks” periodically at fixed or successively longer intervals during the sleep–wake transition to provide brief reassurance until the child falls asleep. The exact interval between checks is generally determined by the parents' tolerance for crying and the child's temperament. The goal is to allow the infant or child to develop skills in self-soothing during the night, as well as at bedtime. In older infants and young children, the introduction of more appropriate sleep associations that will be readily available to the child during the night (transitional objects, such as a blanket or toy), in addition to positive reinforcement (stickers for remaining in bed), is often beneficial. If the child has become habituated to awaken for nighttime feedings (learned hunger), these feedings should be slowly eliminated. Parents must be consistent in applying behavioral programs to avoid inadvertent, intermittent reinforcement of night wakings. They should also be forewarned that crying behavior often temporarily escalates at the beginning of treatment (postextinction burst ).

Bedtime problems, including stalling and refusing to go to bed, are more common in preschool-age and older children. This type of insomnia is frequently related to inadequate limit setting and is often the result of parental difficulties in setting limits and managing behavior in general and the inability or unwillingness to set consistent bedtime rules and enforce a regular bedtime. The situation may be exacerbated by the child's oppositional behavior. In some cases the child's resistance at bedtime is the result of an underlying problem in falling asleep that is caused by other factors (medical conditions such as asthma or medication use; a sleep disorder such as restless legs syndrome; anxiety) or a mismatch between the child's intrinsic circadian rhythm (“night owl”) and parental expectations regarding an “appropriate” bedtime.

Successful treatment of limit-setting sleep problems generally involves a combination of parent education regarding appropriate limit setting, decreased parental attention for bedtime-delaying behavior, establishment of bedtime routines, and positive reinforcement (sticker charts) for appropriate behavior at bedtime. Other behavioral management strategies that have empirical support include bedtime fading , or temporarily setting the bedtime closer to the actual sleep-onset time and then gradually advancing the bedtime to an earlier target bedtime. Older children may benefit from being taught relaxation techniques to help themselves fall asleep more readily. Following the principles of healthy sleep practices for children is essential (Table 31.2 ).

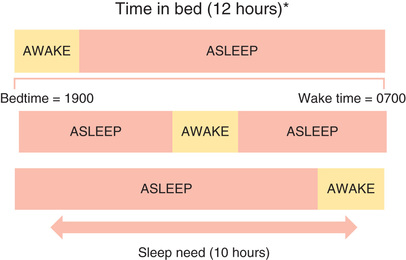

A 3rd type of childhood insomnia is related to a mismatch between parental expectations regarding time in bed and the child's intrinsic sleep needs. If, as illustrated in Fig. 31.1 , a child's typical sleep time is 10 hr but the “sleep window” is set for 12 hr (7 PM to 7 AM ), the result is likely to be a prolonged sleep onset of 2 hr, an extended period of wakefulness during the night, or early morning waking (or a combination); these periods are usually characterized by “normal” wakefulness in the child that is not accompanied by excessive distress. This situation is important to recognize because the solution—reducing the time in bed to actual sleep time—is typically simple and effective.

Another form of insomnia that is more common in older children and adolescents is often referred to as psychophysiologic, primary, or learned insomnia. Primary insomnia occurs mainly in adolescents and is characterized by a combination of learned sleep-preventing associations and heightened physiologic arousal resulting in a complaint of sleeplessness and decreased daytime functioning. A hallmark of primary insomnia is excessive worry about sleep and an exaggerated concern of the potential daytime consequences. The physiologic arousal can be in the form of cognitive hypervigilance , such as “racing” thoughts; in many individuals with insomnia, an increased baseline level of arousal is further intensified by this secondary anxiety about sleeplessness. Treatment usually involves educating the adolescent about the principles of healthy sleep practices (Table 31.3 ), institution of a consistent sleep–wake schedule, avoidance of daytime napping, instructions to use the bed for sleep only and to get out of bed if unable to fall asleep (stimulus control ), restricting time in bed to the actual time asleep (sleep restriction ), addressing maladaptive cognitions about sleep, and teaching relaxation techniques to reduce anxiety.

Behavioral treatments for insomnia, even in young children, appear to be highly effective and well tolerated. Several studies have failed to demonstrate long-term negative effects of behavioral strategies such as “sleep training” on parent–child relationships and attachment, psychosocial-emotional functioning, and chronic stress. In general, hypnotic medications or supplements such as melatonin are infrequently needed as an adjunct to behavioral therapy to treat insomnia in typically developing and healthy children.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

Sleep-related breathing disorder (SRBD ) in children encompasses a broad spectrum of respiratory disorders that occur exclusively in sleep or that are exacerbated by sleep, including primary snoring and upper airway resistance syndrome, as well as apnea of prematurity (see Chapter 122.2 ) and central apnea (see Chapter 446.2 ). Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) , the most important clinical entity within the SRBD spectrum, is characterized by repeated episodes of prolonged upper airway obstruction during sleep despite continued or increased respiratory effort, resulting in complete (apnea ) or partial (hypopnea ; ≥30% reduction in airflow accompanied by ≥3% O2 desaturation and/or arousal) cessation of airflow at the nose and/or mouth, as well as in disrupted sleep. Both intermittent hypoxia and the multiple arousals resulting from these obstructive events likely contribute to significant metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurocognitive-neurobehavioral morbidity.

Primary snoring is defined as snoring without associated ventilatory abnormalities on overnight polysomnogram (e.g., apneas or hypopneas, hypoxemia, hypercapnia) or respiratory-related arousals and is a manifestation of the vibrations of the oropharyngeal soft tissue walls that occur when an individual attempts to breathe against increased upper airway resistance during sleep. Although generally considered nonpathologic, primary snoring in children may still be associated with subtle breathing abnormalities during sleep, including evidence of increased respiratory effort, which in turn may be associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Etiology

OSAS results from an anatomically or functionally narrowed upper airway; this typically involves some combination of decreased upper airway patency (upper airway obstruction and/or decreased upper airway diameter), increased upper airway collapsibility (reduced pharyngeal muscle tone), and decreased drive to breathe in the face of reduced upper airway patency (reduced central ventilatory drive) (Table 31.4 ). Upper airway obstruction varies in degree and level (i.e., nose, nasopharynx/oropharynx, hypopharynx) and is most frequently caused by adenotonsillar hypertrophy, although tonsillar size does not necessarily correlate with degree of obstruction, especially in older children. Other causes of airway obstruction include allergies associated with chronic rhinitis or nasal obstruction; craniofacial abnormalities, including hypoplasia or displacement of the maxilla and mandible; gastroesophageal reflux with resulting pharyngeal reactive edema (see Chapter 349 ); nasal septal deviation (Chapter 404 ); and velopharyngeal flap cleft palate repair. Reduced upper airway tone may result from neuromuscular diseases, including hypotonic cerebral palsy and muscular dystrophies (see Chapter 627 ), or hypothyroidism (Chapter 581 ). Reduced central ventilatory drive may be present in some children with Arnold-Chiari malformation (see Chapter 446 ); rapid-onset obesity with hypothalamic dysfunction, hypoventilation, and autonomic dysregulation (Chapter 60.1 ); and meningomyelocele (Chapter 609.4 ). In other situations the etiology is mixed; individuals with Down syndrome (see Chapter 98.2 ), because of their facial anatomy, hypotonia, macroglossia, and central adiposity, as well as the increased incidence of hypothyroidism, are at particularly high risk for OSAS, with some estimates of prevalence as high as 70%.

Although many children with OSAS are of normal weight, an increasingly large percentage are overweight or obese, and many of these children are school-age or younger (see Chapter 60 ). There is a significant correlation between weight and SRBD (e.g., habitual snoring, OSAS, sleep-related hypoventilation). Although adenotonsillar hypertrophy also plays an important etiologic role in overweight/obese children with OSAS, mechanical factors related to an increase in the amount of adipose tissue in the throat (pharyngeal fat pads), neck (increased neck circumference), and chest wall and abdomen can increase upper airway resistance, worsen gas exchange, and increase the work of breathing, particularly in the supine position and during REM sleep. A component of blunted central ventilatory drive in response to hypoxia/hypercapnia and hypoventilation may occur as well (see Chapter 446.3 ), particularly in children with morbid or syndrome-based (e.g., Prader-Willi) obesity. Overweight and obese children and adolescents are at particularly high risk for metabolic and cardiovascular complications of SRBD, such as insulin resistance and systemic hypertension. Morbidly obese children are also at increased risk for postoperative complications as well as residual OSAS after adenotonsillectomy.

Epidemiology

Overall prevalence of parent-reported snoring in the pediatric population is approximately 8%; “always” snoring is reported in 1.5–6%, and “often” snoring in 3–15%. When defined by parent-reported symptoms, the prevalence of OSAS is 4–11%. The prevalence of pediatric OSAS as documented by overnight sleep studies using ventilatory monitoring procedures (e.g., in-lab polysomnography, home studies) is 1–4% overall, with a reported range of 0.1–13%. Prevalence is also affected by the demographic characteristics such as age (increased prevalence between 2 and 8 yr), gender (more common in boys, especially after puberty), race/ethnicity (increased prevalence in African American and Asian children), history of prematurity, and family history of OSAS.

Pathogenesis

The upregulation of inflammatory pathways, as indicated by an increase in peripheral markers of inflammation (e.g., C-reactive protein, interleukins), appears to be linked to metabolic dysfunction (e.g., insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, alterations in neurohormone levels such as leptin) in both obese and nonobese children with OSAS. Systemic inflammation and arousal-mediated increases in sympathetic autonomic nervous system activity with altered vasomotor tone may be key contributors to increased cardiovascular risk due to alterations in vascular endothelium in both adults and children with OSA. Other potential mechanisms that may mediate cardiovascular sequelae in adults and children with OSA include elevated systemic blood pressure and ventricular dysfunction. Mechanical stress on the upper airway induced by chronic snoring may also result in both local mucosal inflammation of adenotonsillar tissues and subsequent upregulation of inflammatory molecules, most notably leukotrienes.

One of the primary mechanisms by which OSAS is believed to exert negative influences on cognitive function appears to involve repeated episodic arousals from sleep leading to sleep fragmentation and sleepiness. Equally important, intermittent hypoxia may lead directly to systemic inflammatory vascular changes in the brain. Levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 are elevated in children with OSAS and are also associated with cognitive dysfunction.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of OSAS may be divided into sleep-related and daytime symptoms. The most common nocturnal manifestations of OSAS in children and adolescents are loud, frequent, and disruptive snoring; breathing pauses; choking or gasping arousals; restless sleep; and nocturnal diaphoresis. Many children who snore do not have OSAS, but few children with OSAS do not snore (caregivers may not be aware of snoring in older children and adolescents). Children, like adults, tend to have more frequent and more severe obstructive events in REM sleep and when sleeping in the supine position. Children with OSAS may adopt unusual sleeping positions, keeping their necks hyperextended to maintain airway patency. Frequent arousals associated with obstruction may result in nocturnal awakenings but are more likely to cause fragmented sleep.

Daytime symptoms of OSAS include mouth breathing and dry mouth, chronic nasal congestion or rhinorrhea, hyponasal speech, morning headaches, difficulty swallowing, and poor appetite. Children with OSAS may have secondary enuresis, postulated to result from the disruption of the normal nocturnal pattern of atrial natriuretic peptide secretion by changes in intrathoracic pressure associated with OSAS. Partial arousal parasomnias (sleepwalking and sleep terrors) may occur more frequently in children with OSAS, related to the frequent associated arousals and an increased percentage of SWS.

One of the most important but frequently overlooked sequelae of OSAS in children is the effect on mood, behavior, learning, and academic functioning. The neurobehavioral consequences of OSAS in children include daytime sleepiness with drowsiness, difficulty in morning waking, and unplanned napping or dozing off during activities, although evidence of frank hypersomnolence tends to be less common in children compared to adults with OSA (except in very obese children or those with severe disease). Mood changes include increased irritability, mood instability and emotional dysregulation, low frustration tolerance, and depression or anxiety. Behavioral issues include both “internalizing” (i.e., increased somatic complaints and social withdrawal) and “externalizing” behaviors, including aggression, impulsivity, hyperactivity, oppositional behavior, and conduct problems. There is substantial overlap between the clinical impairments associated with OSAS and the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, including inattention, poor concentration, and distractibility (see Chapter 49 ).

Many of the studies that have looked at changes in behavior and neuropsychologic functioning in children after treatment (usually adenotonsillectomy) for OSAS have largely documented significant improvement in outcomes, both short term and long term, including daytime sleepiness, mood, behavior, academics, and quality of life. However, most studies failed to find a dose-dependent relationship between OSAS in children and specific neurobehavioral-neurocognitive deficits, suggesting that other factors may influence neurocognitive outcomes, including individual genetic susceptibility, racial/ethnic background, environmental influences (e.g., passive smoking exposure), and comorbid conditions, such as obesity, shortened sleep duration, and other sleep disorders.

Diagnosis

The 2012 revised American Academy of Pediatrics clinical practice guidelines provide excellent information for the evaluation and management of uncomplicated childhood OSAS (Table 31.5 ). No physical examination findings are truly pathognomonic for OSAS, and most healthy children with OSAS appear normal; however, certain physical examination findings may suggest OSAS. Growth parameters may be abnormal (obesity, or less frequently, failure to thrive), and there may be evidence of chronic nasal obstruction (hyponasal speech, mouth breathing, septal deviation, “adenoidal facies”) as well as signs of atopic disease (i.e., “allergic shiners”). Oropharyngeal examination may reveal enlarged tonsils, excess soft tissue in the posterior pharynx, and a narrowed posterior pharyngeal space, as well as dental features consistent with obstruction (e.g., teeth crowding, narrow palate, short frenulum). Any abnormalities of head position, such as forward head posture, and facial structure, such as retrognathia, micrognathia, and midfacial hypoplasia, best appreciated by inspection of the lateral facial profile, increase the likelihood of OSAS and should be noted. In severe cases the child may have evidence of pulmonary hypertension, right-sided heart failure, and cor pulmonale; systemic hypertension may occur, especially in obese children.

Because no combination of clinical history and physical findings can accurately predict which children with snoring have OSAS, the gold standard for diagnosing OSAS remains an in-lab overnight polysomnogram (PSG) . Overnight PSG is a technician-supervised, monitored study that documents physiologic variables during sleep; sleep staging, arousal measurement, cardiovascular parameters, and body movements (electroencephalography, electrooculography, chin and leg electromyography, electrocardiogram, body position sensors, and video recording), and a combination of breathing monitors (oronasal thermal sensor and nasal air pressure transducer for airflow), chest/abdominal monitors (e.g., inductance plethysmography for respiratory effort, pulse oximeter for O2 saturation, end-tidal or transcutaneous CO2 for CO2 retention, snore microphone). The PSG parameter most often used in evaluating for sleep-disordered breathing is the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) , which indicates the number of apneic and hypopneic (both obstructive and central) events per hour of sleep. Currently, there are no universally accepted PSG normal reference values or parameters for diagnosing OSAS in children, and it is still unclear which parameters best predict morbidity. Normal preschool and school-age children generally have a total AHI <1.5 (obstructive AHI <1), and this is the most widely used cutoff value for OSA in children ≤12 yr old; in older adolescents the adult cutoff of an AHI ≥5 is generally used. When AHI is between 1 and 5 obstructive events per hour, assessment of additional PSG parameters (e.g., elevated CO2 indicating obstructive hypoventilation, O2 desaturation, respiratory-related arousals), clinical judgment regarding risk factors for SRBD, presence and severity of clinical symptoms, and evidence of daytime sequelae should determine further management.

Treatment

At present, no universally accepted guidelines exist regarding the indications for treatment of pediatric SRBD, including primary snoring and OSAS. Current recommendations largely emphasize weighing what is known about the potential cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurocognitive sequelae of SRBD in children in combination with the individual healthcare professional's clinical judgment. The decision of whether and how to treat OSAS specifically in children depends on several parameters, including severity (nocturnal symptoms, daytime sequelae, sleep study results), duration of disease, and individual patient variables such as age, comorbid conditions, and underlying etiologic factors. In the case of moderate (AHI 5-10) to severe (AHI >10) disease, the decision to treat is usually straightforward, and most pediatric sleep experts recommend that any child with AHI >5 should be treated. However, a large randomized trial of early adenotonsillectomy vs watchful waiting with supportive care demonstrated that 46% of the control group children normalized on PSG (vs 79% of early adenotonsillectomy group) during the 7 mo observation period.

In the majority of cases of pediatric OSAS, adenotonsillectomy is the first-line treatment in any child with significant adenotonsillar hypertrophy, even in the presence of additional risk factors such as obesity. Adenotonsillectomy in uncomplicated cases generally (70–90% of children) results in complete resolution of symptoms; regrowth of adenoidal tissue after surgical removal occurs in some cases. Groups considered at high risk include young children (<3 yr) as well as those with severe OSAS documented by PSG, significant clinical sequelae of OSAS (e.g., failure to thrive), or associated medical conditions, such as craniofacial syndromes, morbid obesity, and hypotonia. All patients should be reevaluated postoperatively to determine whether additional evaluation, a repeat PSG, and treatment are required. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that in high-risk groups (children with obesity, craniofacial anomalies, Down syndrome, or moderate-severe OSAS) or in children with continued symptoms of OSAS, a follow-up sleep study about 6 wk after adenotonsillectomy is indicated. Also, a number of studies have suggested that children who are underweight, normal weight, or overweight/obese at baseline all tend to gain weight after AT, and thus clinical vigilance is required during follow-up.

Additional treatment measures that may be appropriate include weight loss, positional therapy (attaching a firm object, such as a tennis ball, to the back of a sleep garment to prevent the child from sleeping in the supine position) and aggressive treatment of additional risk factors when present, such as asthma, seasonal allergies, and gastroesophageal reflux. Evidence suggests that intranasal corticosteroids and leukotriene inhibitors may be helpful in reducing upper airway inflammation in mild OSAS. Other surgical procedures (e.g., uvulopharyngopalatoplasty) and maxillofacial surgery (e.g., mandibular distraction osteogenesis) are seldom performed in children. Oral appliances, such as mandibular advancing devices and palatal expanders, may be considered in select cases; consultation with a pediatric dentist or orthodontist is recommended. Neuromuscular reeducation or repatterning of the oral and facial muscles with exercises to address abnormal tongue position and low upper airway tone (i.e., myofunctional therapy ) have been shown to be beneficial in addressing pediatric OSAS as well as alleviating chewing and swallowing problems in children able to cooperate with the behavioral program.

Continuous or bilevel positive airway pressure (CPAP or BiPAP) is the most common treatment for OSAS in adults and can be used successfully in children and adolescents. Positive airway pressure (PAP) may be recommended if removing the adenoids and tonsils is not indicated, if there is residual disease following adenotonsillectomy, or if there are major risk factors not amenable to surgery (obesity, hypotonia). PAP delivers humidified, warmed air through an interface (mask, nasal pillows) that, under pressure, effectively “splints” the upper airway open. Optimal pressure settings (that abolish or significantly reduce respiratory events without increasing arousals or central apneas) are determined in the sleep lab during a full-night PAP titration. Careful attention should be paid to education of the child and family, and desensitization protocols should usually be implemented to increase the likelihood of adherence. Efficacy studies at the current pressure and retitrations should be conducted periodically with long-term use (at least annually) or in association with significant weight changes or resurgence of SRBD symptoms.

Parasomnias

Parasomnias are episodic nocturnal behaviors that often involve cognitive disorientation and autonomic and skeletal muscle disturbance. Parasomnias may be further characterized as occurring primarily during non-REM sleep (partial arousal parasomnias) or in association with REM sleep, including nightmares, hypnogogic hallucinations, and sleep paralysis; other common parasomnias include sleep-talking and hypnic jerks or “sleep starts.”

Etiology

Partial arousal parasomnias represent a dissociated sleep–wake state, the neurobiology of which remains unclear, although genetic factors and an intrinsic oscillation of subcortical-cortical arousal with sleep have been proposed. These episodic events, which include sleepwalking, sleep terrors, and confusional arousals, are more common in preschool and school-age children because of the relatively higher percentage of SWS in younger children. Partial arousal parasomnias typically occur when SWS predominates, in the 1st third of the night. In contrast, nightmares , which are much more common than partial arousal parasomnias but are often confused with them, tend to be concentrated in the last third of the night, when REM sleep is most prominent. Any factor associated with an increase in the relative percentage of SWS (certain medications, previous sleep restriction) may increase the frequency of events in a predisposed child. There appears to be a genetic predisposition for both sleepwalking and night terrors. Partial arousal parasomnias may also be difficult to distinguish from nocturnal seizures. Table 31.6 summarizes similarities and differences among these nocturnal arousal events.

Table 31.6

Key Similarities and Differentiating Features Between Non-REM and REM Parasomnias as Well as Nocturnal Seizures

| CONFUSIONAL AROUSALS | SLEEP TERRORS | SLEEPWALKING | NIGHTMARES | NOCTURNAL SEIZURES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Early | Early | Early-mid | Late | Any |

| Sleep stage | SWA | SWA | SWA | REM | Any |

| EEG discharges | − | − | − | − | + |

| Scream | − | ++++ | − | ++ | + |

| Autonomic activation | + | ++++ | + | + | + |

| Motor activity | − | + | +++ | + | ++++ |

| Awakens | − | − | − | + | + |

| Duration (min) | 0.5-10; more gradual offset | 1-10; more gradual offset | 2-30; more gradual offset | 3-20 | 5-15; abrupt onset and offset |

| Postevent confusion | + | + | + | − | + |

| Age | Child | Child | Child | Child, young adult | Adolescent, young adult |

| Genetics | + | + | + | − | ± |

| Organic CNS lesion | − | − | − | − | ++++ |

CNS, Central nervous system; EEG, electroencephalogram; REM, rapid eye movement; SWA, slow-wave arousal.

From Avidan A, Kaplish N: The parasomnias: epidemiology, clinical features and diagnostic approach. Clin Chest Med 31:353–370, 2010.

Epidemiology

Many children sleepwalk on at least one occasion; the lifetime prevalence by age 10 yr is 13%. Sleepwalking (somnambulism) may persist into adulthood, with the prevalence in adults of approximately 4%. The prevalence is approximately 10 times greater in children with a family history of sleepwalking. The peak prevalence of sleep terrors is 34% at age 1-5 yr, decreasing to 10% by age 7; the age at onset is usually between 4 and 12 yr. Because of the common genetic predisposition, the likelihood of developing sleepwalking after age 5 is almost 2-fold higher in children with a history of sleep terrors. Although sleep terrors can occur at any age from infancy through adulthood, most individuals outgrow sleep terrors by adolescence. Confusional arousals (sleep drunkenness, sleep inertia) usually occur with sleepwalking and sleep terrors; prevalence rates have been estimated at >15% in children age 3-13 yr.

Clinical Manifestations

The partial arousal parasomnias have several features in common. Because they typically occur at the transition out of “deep” sleep or SWS, partial arousal parasomnias have clinical features of both the awake (ambulation, vocalizations) and the sleeping (high arousal threshold, unresponsiveness to environment) states, usually with amnesia for the events. External (noise) or internal (obstruction) factors may trigger events in some individuals. The duration is typically a few minutes (sleep terrors) up to 30-40 min (confusional arousals). Sleep terrors are sudden in onset and characteristically involve a high degree of autonomic arousal (tachycardia, dilated pupils). Confusional arousals typically arise more gradually from sleep, may involve thrashing around but usually not displacement from bed, and are often accompanied by slow mentation, disorientation, and confusion on forced arousal from SWS or on waking in the morning. Sleepwalking may be associated with safety concerns (e.g., falling out of windows, wandering outside). The child's avoidance of, or increased agitation with, comforting by parents or attempts at awakening is also common to all partial arousal parasomnias.

Treatment

Management of partial arousal parasomnias involves some combination of parental education and reassurance, healthy sleep practices, and avoidance of exacerbating factors such as sleep restriction and caffeine. Particularly in the case of sleepwalking, it is important to institute safety precautions such as use of gates in doorways and at the top of staircases, locking of outside doors and windows, and installation of parent notification systems such as bedroom door alarms. Scheduled awakenings is a behavioral intervention that involves having the parent wake the child 15-30 min before the time of night that the 1st parasomnia episode occurs and is most likely to be successful in situations where partial arousal episodes occur on a nightly basis. Pharmacotherapy is rarely necessary but may be indicated in cases of frequent or severe episodes, high risk of injury, violent behavior, or serious disruption to the family. The primary pharmacologic agents used are potent SWS suppressants, primarily benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants.

Sleep-Related Movement Disorders: Restless Legs Syndrome/Periodic Limb Movement Disorder and Rhythmic Movements

Restless legs syndrome (RLS ), also termed Willis-Ekbom disease , is a chronic neurologic disorder characterized by an almost irresistible urge to move the legs, often accompanied by uncomfortable sensations in the lower extremities. Both the urge to move and the sensations are usually worse at rest and in the evening and are at least partially relieved by movement, including walking, stretching, and rubbing, but only if the motion continues. RLS is a clinical diagnosis that is based on the presence of these key symptoms (Table 31.7 ).

Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD ) is characterized by periodic, repetitive, brief (0.5-10 sec), and highly stereotyped limb jerks typically occurring at 20-40 sec intervals. These movements occur primarily during sleep, usually occur in the legs, and frequently consist of rhythmic extension of the big toe and dorsiflexion at the ankle. The diagnosis of periodic limb movements (PLMs) requires overnight PSG to document the characteristic limb movements with anterior tibialis electromyography leads.

Etiology

“Early-onset” RLS (onset of symptoms before 35-40 yr of age), often termed primary RLS, appears to have a particularly strong genetic component, with a 6-7–fold increase in prevalence in first-degree relatives of RLS patients. The mode of inheritance is complex, and several genetic loci have been identified (MEIS1, BTBD9, MAP2K5 ). Low serum iron levels (even without anemia) in both adults and children may be an important etiologic factor for the presence and severity of both RLS symptoms and PLMs. As a marker of decreased iron stores, serum ferritin levels in both children and adults with RLS are frequently low; (<50 µg/mL). The postulated underlying mechanism is related to the role of iron as a cofactor in tyrosine hydroxylation, a rate-limiting step in dopamine synthesis; in turn, dopaminergic dysfunction has been implicated, particularly in the genesis of the sensory component of RLS, as well as in PLMD. Certain medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, cancer, idiopathic juvenile arthritis, hypothyroidism, and pregnancy, may also be associated with RLS/PLMD, as are specific medications (e.g., antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, antidepressants, H2 blockers such as cimetidine) and substances (notably, caffeine).

Epidemiology

Previous studies found prevalence rates of RLS in the pediatric population ranging from 1–6%; approximately 2% of 8-17 yr olds meet the criteria for “definite” RLS. Prevalence rates of PLMs >5 per hour in clinical populations of children referred for sleep studies range from 5–27%; in survey studies of PLM symptoms, rates are 8–12%. About 40% of adults with RLS have symptoms before age 20 yr; 20% report symptoms before age 10. Familial cases usually have a younger age of onset. Several studies in referral populations have found that PLMs occur in as many as 25% of children diagnosed with ADHD.

Clinical Manifestations

In addition to the urge to move the legs and the sensory component (paresthesia-like, tingling, burning, itching, crawling), most RLS episodes are initiated or exacerbated by rest or inactivity, such as lying in bed to fall asleep or riding in a car for prolonged periods. A unique feature of RLS is that the timing of symptoms also appears to have a circadian component, in that they often peak in the evening hours. Some children may complain of “growing pains,” although this is considered a nonspecific feature. Because RLS symptoms are usually worse in the evening, bedtime struggles and difficulty falling asleep are two of the most common presenting complaints. In contrast to patients with RLS, individuals with PLMs are usually unaware of these movements, but children may complain of morning muscle pain or fatigue; these movements may result in arousals during sleep and consequent significant sleep disruption. Parents of children with RLS/PLMD may report that their child is a restless sleeper, moves around, or even falls out of bed during the night.

The differential diagnosis includes growing pains, leg cramps, neuropathy, arthritis, myalgias, nerve compression (“leg fell asleep”), and dopamine antagonist–associated akathisia.

Treatment

The decision of whether and how to treat RLS depends on the level of severity (intensity, frequency, and periodicity) of sensory symptoms, the degree of interference with sleep, and the impact of daytime sequelae in a particular child or adolescent. With PLMs, for an index (PLMs/hr) <5, usually no treatment is recommended; for an index >5, the decision to specifically treat PLMs should be based on the presence or absence of nocturnal symptoms (restless or nonrestorative sleep) and daytime clinical sequelae.

The acronym AIMS represents a comprehensive approach to the treatment of RLS: avoidance of exacerbating factors, such as caffeine and drugs, that increase symptoms; iron supplementation when appropriate; muscle activity, with increased physical activity, muscle relaxation, and application of heat/cold compresses; and sleep, with a regular sleep schedule and sufficient sleep for age. Iron supplements should be instituted if serum ferritin levels are <50 µg/L; it should be kept in mind that ferritin is an acute-phase reactant and thus may be falsely elevated (i.e., normal) in the setting of a concomitant illness. The recommended dose of oral ferrous sulfate is typically 3-6 mg/kg/day for 3 mo. If there is no response to oral iron, intravenous iron compounds may be needed. Medications that increase dopamine levels in the CNS, such as ropinirole and pramipexole, are effective in relieving RLS/PLMD symptoms in adults; data in children are extremely limited. Dopaminergic therapy may lead to a loss of therapeutic response. Some recommend gabapentin enacarbil or other related alpha-2 delta ligands that bind to the alpha-2 delta subunit of the voltage-activated calcium channel.

Sleep-related rhythmic movements , including head banging, body rocking, and head rolling, are characterized by repetitive, stereotyped, and rhythmic movements or behaviors that involve large muscle groups. These behaviors typically occur with the transition to sleep at bedtime, but also at nap times and after nighttime arousals. Children typically engage in these behaviors as a means of soothing themselves to (or back to) sleep; these are much more common in the 1st yr of life and usually disappear by preschool age. In most cases, rhythmic movement behaviors are benign, because sleep is not significantly disrupted, and associated significant injury is rare. These behaviors typically occur in normally developing children and in the majority of cases do not indicate some underlying neurologic or psychologic problem. Usually, the most important aspect in management of sleep-related rhythmic movements is reassurance to the family that this behavior is normal, common, benign, and self-limited.

Narcolepsy

Hypersomnia is a clinical term that is used to describe a group of disorders characterized by recurrent episodes of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) , reduced baseline alertness, and/or prolonged nighttime sleep periods that interfere with normal daily functioning (Table 31.8 ). The many potential causes of EDS can be broadly grouped as “extrinsic” (e.g., secondary to insufficient and/or fragmented sleep) or “intrinsic” (e.g., resulting from an increased need for sleep). Narcolepsy is a chronic, lifelong CNS disorder, typically presenting in adolescence and early adulthood, characterized by profound daytime sleepiness resulting in significant functional impairment. More than half of patients with narcolepsy also present with cataplexy (type 1), defined as the sudden, brief, partial or complete loss of skeletal muscle tone, typically triggered by strong emotion (e.g., laughter, surprise, anger), with retained consciousness. Other symptoms frequently associated with narcolepsy, including hypnogogic/hypnopompic (immediately before falling asleep/awakening) typically visual hallucinations and sleep paralysis, may be conceptualized as representing the “intrusion” of REM sleep features into the waking state. Other REM-related features include observance of eye movements and twitches at sleep onset and vivid dreams. Rapid weight gain, especially near symptom onset, is frequently observed, and young children with narcolepsy have been reported to develop precocious puberty.

Etiology

The genesis of narcolepsy with cataplexy (type 1) is thought to be related to a specific deficit in the hypothalamic orexin/hypocretin neurotransmitter system involving the selective loss of cells that secrete hypocretin/orexin in the lateral hypothalamus. Hypocretin neurons stimulate a range of wake-promoting neurons in the brainstem, hypothalamus, and cortex and basal forebrain that produce neurochemicals to sustain the wake state and prevent lapses into sleep.

The development of narcolepsy most likely involves autoimmune mechanisms, possibly triggered by streptococcal, influenza virus, H1N1, and other viral infections, likely in combination with a genetic predisposition and environmental factors. A 12-13–fold increase in narcolepsy type 1 cases, especially in children, was reported in parts of Europe in 2009–2010 following immunization with the AS03 adjuvanted H1N1 influenza vaccine. Human leukocyte antigen testing also shows a strong association with narcolepsy; the majority of individuals with this antigen do not have narcolepsy, but most (>90%) patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy are HLA-DQB1*0602–positive. Patients with narcolepsy without cataplexy (type 2) are increasingly thought to have a significantly different pathophysiology; they are much less likely to be HLA-DQB1*0602–positive (4–50%), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hypocretin levels are normal in most patients.

Although the majority of cases of narcolepsy are considered idiopathic (autoimmune), secondary narcolepsy can be caused by lesions to the posterior hypothalamus induced by traumatic brain injury, tumor, stroke, and neuroinflammatory processes such as post-streptococcal PANDAS (see Chapter 210 ), as well as by neurogenetic diseases such as Prader-Willi syndrome (Chapter 98.8 ), Niemann-Pick type C (Chapter 104.4 ), myotonic dystrophy (Chapter 627.6 ), and Norrie disease.

Epidemiology

Narcolepsy is a rare disorder with a prevalence of approximately 0.025–0.05%. The risk of developing narcolepsy with cataplexy in a first-degree relative of a narcoleptic patient is estimated at 1–2%. This represents an increase of 10-40–fold compared to the general population, but the risk remains very low, reinforcing the likely role for other etiologic factors.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The typical onset of symptoms of narcolepsy is in adolescence and early adulthood, although symptoms may initially present in school-age and even younger children. The early manifestations of narcolepsy are often ignored, misinterpreted, or misdiagnosed as other medical, neurologic, or psychiatric conditions, and the appropriate diagnosis is frequently delayed for years. The onset may be abrupt or slowly progressive.

The most prominent clinical manifestation of narcolepsy is profound daytime sleepiness, characterized by both an increased baseline level of daytime drowsiness and the repeated occurrence of sudden and unpredictable sleep episodes. These “sleep attacks” are often described as “irresistible,” in that the child or adolescent is unable to stay awake despite considerable effort, and occur even in the context of normally stimulating activities (e.g., during meals, in conversation). Very brief (several seconds) sleep attacks may also occur in which the individual may “stare off,” appear unresponsive, or continue to engage in an ongoing activity (automatic behavior ). EDS may also be manifested by increased nighttime sleep needs and extreme difficulty waking in the morning or after a nap.

Cataplexy is considered virtually pathognomonic for narcolepsy but can develop several years after the onset of EDS. Manifestations are triggered by strong positive (laughing, joy) or negative (fright, anger, frustration) emotions and predominantly include facial slackening, head nodding, jaw dropping, and less often, knees buckling or complete collapse with falling to the ground. The cataplectic attacks are typically brief (seconds to minutes), the patient is awake and aware, and episodes are fully reversible, with complete recovery of normal tone when the episode ends. A form of cataplexy unique to children known as cataplectic facies is characterized by prolonged tongue protrusion, ptosis, slack jaw, slurred speech, grimacing, and gait instability. Additionally, children may have positive motor phenomenon similar to dyskinesias or motor tics, with repetitive grimacing and tongue thrusting. The cataplectic attacks are typically brief (seconds to minutes) but in children may last for hours or days (status cataplecticus ).

Hypnogogic/hypnopompic hallucinations usually involve vivid visual but also auditory and sometimes tactile sensory experiences during transitions between sleep and wakefulness, either at sleep offset (hypnopompic) or sleep onset (hypnogogic). Sleep paralysis is the inability to move or speak for a few seconds or minutes at sleep onset or offset and often accompanies the hallucinations. Other symptoms associated with narcolepsy include disrupted nocturnal sleep, impaired cognition, inattention and ADHD-like symptoms, and behavioral and mood dysregulation.

Several pediatric screening questionnaires for EDS, including the modified Epworth Sleepiness Scale, help to guide the need for further evaluation in clinical practice when faced with the presenting complaint of daytime sleepiness. Physical examination should include a detailed neurologic assessment. Overnight PSG and a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) are strongly recommended components in the evaluation of a patient with profound unexplained daytime sleepiness or suspected narcolepsy. The purpose of the overnight PSG is to evaluate for primary sleep disorders (e.g., OSAS) that may cause EDS. The MSLT involves a series of 5 opportunities to nap (20 min long), during which patients with narcolepsy demonstrate a pathologically shortened mean sleep-onset latency (≤8 min, typically <5 min) as well as at least 2 periods of REM sleep occurring immediately after sleep onset. Alternatively, a diagnosis can be made by findings of low CSF hypocretin-1 concentration (typically ≤110 pg/mL) with a standardized assay.

Treatment

An individualized narcolepsy treatment plan usually involves education, good sleep hygiene, behavioral changes, and medication. Scheduled naps during the day are often helpful. Wake-promoting medications such as modafinil or armodafinil may be prescribed to control the EDS, although these are not approved for use in children by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and potential side effects include rare reports of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and reduced efficacy of hormone-based contraceptives. Psychostimulants are approved for ADHD in children and can be used for EDS; side effects include appetite suppression, mood lability, and cardiovascular effects. Antidepressants (serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine) may be used to reduce cataplexy. Sodium oxybate, also not currently FDA-approved for use in children, is a unique drug that appears to have a positive impact on daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, and nocturnal sleep disruption; reported side effects include dizziness, weight loss, enuresis, exacerbation of OSAS, depression, and risk of respiratory depression, especially when combined with CNS depressants, including alcohol. Pitolisant, a histamine (H3 ) receptor agonist, has been shown to improve cataplexy and EDS in adult patients with narcolepsy. The goal for the child should be to allow the fullest possible return of normal functioning in school, at home, and in social situations.

Delayed Sleep–Wake Phase Disorder

Delayed sleep–wake phase disorder (DSWPD ), a circadian rhythm disorder, involves a significant, persistent, and intractable phase shift in sleep–wake schedule (later sleep onset and wake time) that conflicts with the individual's normal school, work, and lifestyle demands. DSWPD may occur at any age but is most common in adolescents and young adults.

Etiology

Individuals with DSPD may start out as “night owls”; that is, they have an underlying predisposition or circadian “eveningness” preference for staying up late at night and sleeping late in the morning, especially on weekends, holidays, and summer vacations. The underlying pathophysiology of DSWPD is still unknown, although some theorize that it involves an intrinsic abnormality in the circadian oscillators that govern the timing of the sleep period.

Epidemiology

Studies indicate that the prevalence of DSWPD may be as high as 7–16% in adolescents and young adults.

Clinical Manifestations

The most common clinical presentation is sleep-initiation insomnia when the individual attempts to fall asleep at a “socially acceptable” desired bedtime and experiences very delayed sleep onset (often after 1-2 AM ), accompanied by daytime sleepiness. Patients may have extreme difficulty arising in the morning even for desired activities, with pronounced confusion on waking (sleep inertia ). Sleep maintenance is generally not problematic, and no sleep-onset insomnia is experienced if bedtime coincides with the preferred sleep-onset time (e.g., on weekends, school vacations). School tardiness and frequent absenteeism with a decline in academic performance often occur. Patients may also develop “secondary” psychophysiologic insomnia as a result of spending prolonged time in bed attempting to fall asleep at bedtime.

Treatment

The treatment of DSWPD usually has three components, all directed toward the goals of shifting the sleep–wake schedule to an earlier, more desirable time and maintaining the new schedule. The initial step involves shifting the sleep–wake schedule to the desired earlier times, usually with gradual (i.e., in 15-30 min increments every few days) advancement of bedtime in the evening and rise time in the morning. More significant phase delays (i.e., larger difference between current sleep onset and desired bedtime) may require chronotherapy, which involves delaying bedtime and wake time by 2-3 hr every 24 hr “forward around the clock” until the target bedtime is reached. Because melatonin secretion is highly sensitive to light, exposure to light in the morning (either natural light or a “light box,” which typically produces light at around 10,000 lux) and avoidance of evening light exposure (especially from screens emitting predominantly blue light, such as computers and laptops) are often beneficial. Exogenous oral melatonin supplementation may also be used; larger, mildly sedating doses (5 mg) are typically given at bedtime, but some studies have suggested that physiologic doses of oral melatonin (0.3-0.5 mg) administered in the afternoon or early evening (5-7 hr before the habitual sleep-onset time) may be more effective in advancing the sleep phase.

Health Supervision

It is especially important for pediatricians to screen for and recognize sleep disorders in children and adolescents during healthcare encounters. The well-child visit is an opportunity to educate parents about normal sleep in children and to teach strategies to prevent sleep problems from developing (primary prevention) or becoming chronic, if problems already exist (secondary prevention). Developmentally appropriate screening for sleep disturbances should take place in the context of every well-child visit and should include a range of potential sleep problems; Table 31.9 outlines a simple sleep screening algorithm, the “BEARS.” Because parents may not always be aware of sleep problems, especially in older children and adolescents, it is also important to question the child directly about sleep concerns. The recognition and evaluation of sleep problems in children require both an understanding of the association between sleep disturbances and daytime consequences (e.g., irritability, inattention, poor impulse control) and familiarity with the developmentally appropriate differential diagnoses of common presenting sleep complaints (difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep, episodic nocturnal events). An assessment of sleep patterns and possible sleep problems should be part of the initial evaluation of every child presenting with behavioral or academic problems, especially ADHD.

Table 31.9

BEARS Sleep Screening Algorithm

|

The BEARS instrument is divided into 5 major sleep domains, providing a comprehensive screen for the major sleep disorders affecting children 2-18 yr old. Each sleep domain has a set of age-appropriate “trigger questions” for use in the clinical interview. B = Bedtime problems E = Excessive daytime sleepiness A = Awakenings during the night R = Regularity and duration of sleep S = Snoring |

|||

| EXAMPLES OF DEVELOPMENTALLY APPROPRIATE TRIGGER QUESTIONS | |||

| Toddler/Preschool Child (2-5 yr) | School-Age Child (6-12 yr) | Adolescent (13-18 yr) | |

| Does your child have any problems going to bed? Falling asleep? |

Does your child have any problems at bedtime? (P) Do you any problems going to bed? (C) |

Do you have any problems falling asleep at bedtime? (C) | |

| Does your child seem overtired or sleepy a lot during the day? Does your child still take naps? |

Does your child have difficulty waking in the morning, seem sleepy during the day, or take naps? (P) Do you feel tired a lot? (C) |

Do you feel sleepy a lot during the day? In school? While driving? (C) | |

| Does your child wake up a lot at night? |

Does your child seem to wake up a lot at night? Any sleepwalking or nightmares? (P) Do you wake up a lot at night? Do you have trouble getting back to sleep? (C) |

Do you wake up a lot at night? Do you have trouble getting back to sleep? (C) | |

| Does your child have a regular bedtime and wake time? What are they? | What time does your child go to bed and get up on school days? Weekends? Do you think your child is getting enough sleep? (P) | What time do you usually go to bed on school nights? Weekends? How much sleep do you usually get? (C) | |

| Does your child snore a lot or have difficulty breathing at night? | Does your child have loud or nightly snoring or any breathing difficulties at night? (P) | Does your teenager snore loudly or nightly? (P) | |

C, Child; P, parent.

Effective preventive measures include educating parents of newborns about normal sleep amounts and patterns. The ability to regulate sleep, or control internal states of arousal to fall asleep at bedtime and to fall back asleep during the night, begins to develop in the 1st 8-12 wk of life. Thus it is important to recommend that parents put their 2-4 mo old infants to bed “drowsy but awake” if they want to avoid dependence on parental presence at sleep onset and foster the infant's ability to self-soothe. Other important sleep issues include discussing the importance of regular bedtimes, bedtime routines, and transitional objects for toddlers, and providing parents and children with basic information about healthy sleep practices, recommended sleep amounts at different ages, and signs that a child is not getting sufficient sleep (wakes with difficulty at required time in morning, sleeps longer given opportunity on weekends and vacation days).

The cultural and family context within which sleep problems in children occur should be considered. For example, bed-sharing of infants and parents is a common and accepted practice in many racial/ethnic groups, and these families may not share the goal of independent self-soothing in young infants. Anticipatory guidance needs to balance cultural awareness with the critical importance of “safe sleep” conditions in sudden infant death syndrome prevention (i.e., sleeping in the supine position, avoidance of bed-sharing but encouragement of room-sharing in the 1st yr of life) (see Chapter 402 ). On the other hand, the institution of cosleeping by parents as an attempt to address a child's underlying sleep problem (so-called reactive cosleeping), rather than as a conscious family decision, is likely to yield only a temporary respite from the problem and may set the stage for more significant sleep issues.

Evaluation of Pediatric Sleep Problems

The clinical evaluation of a child presenting with a sleep problem involves obtaining a careful medical history to assess for potential medical causes of sleep disturbances, such as allergies, concomitant medications, and acute or chronic pain conditions. A developmental history is important because of the increased risk of sleep problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Assessment of the child's current level of functioning (school, home) is a key part of evaluating possible mood, behavioral, and neurocognitive sequelae of sleep problems. Current sleep patterns, including the usual sleep duration and sleep–wake schedule, are often best assessed with a sleep diary, in which a parent (or adolescent) records daily sleep behaviors for an extended period (1-2 wk). A review of sleep habits, such as bedtime routines, daily caffeine intake, and the sleeping environment (e.g., temperature, noise level), may reveal environmental factors that contribute to the sleep problems. Nocturnal symptoms that may be indicative of a medically based sleep disorder, such as OSAS (loud snoring, choking or gasping, sweating) or PLMs (restless sleep, repetitive kicking movements), should be elicited. Home video recording may be helpful in the evaluation of potential parasomnia episodes and the assessment of snoring and increased work of breathing in children with OSAS. An overnight sleep study (PSG) is not routinely warranted in the evaluation of a child with sleep problems unless there are symptoms suggestive of OSAS or PLMs, unusual features of episodic nocturnal events, or unexplained daytime sleepiness.

in.

in.