Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Fern R. Hauck, Rebecca F. Carlin, Rachel Y. Moon, Carl E. Hunt

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is defined as the sudden, unexpected death of an infant that is unexplained by a thorough postmortem examination, which includes a complete autopsy, investigation of the scene of death, and review of the medical history. An autopsy is essential to identify possible natural explanations for sudden unexpected death such as congenital anomalies or infection and to diagnose traumatic child abuse (Tables 402.1 to 402.3 ; see Chapter 16 ). The autopsy typically cannot distinguish between SIDS and intentional suffocation, but the scene investigation and medical history may be of help if inconsistencies are evident. Sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) is a term that generally encompasses all SUIDs that occur during sleep, including SIDS (ICD-10 R95), accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed (ICD-10 W75), and ill-defined deaths, also known as undetermined (ICD-10 R99).

Table 402.1

Differential Diagnosis of Sudden Unexpected Infant Death

| CAUSE OF DEATH | PRIMARY DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA | POTENTIAL CONFOUNDING DIAGNOSES | FREQUENCY DISTRIBUTION (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EXPLAINED AT AUTOPSY | |||

| Natural | 18–20* | ||

| Infections | History, autopsy, and cultures | If minimal findings: SIDS | 35–46 † |

| Congenital anomaly | History and autopsy | If minimal findings: SIDS | 14–24 † |

| Unintentional injury | History, scene investigation, autopsy | Traumatic child abuse | 15* |

| Traumatic child abuse | Autopsy and scene investigation | Unintentional injury | 13–24* |

| Other natural causes | History and autopsy | If minimal findings: SIDS, or intentional suffocation | 12–17* |

| UNEXPLAINED AT AUTOPSY | |||

| SIDS | History, scene investigation, absence of explainable cause at autopsy | Intentional suffocation | 80–82 |

| Intentional suffocation (filicide) | Perpetrator confession, absence of explainable cause at autopsy | SIDS | Unknown, but <5% of all SUID |

| Accidental suffocation or strangulation in bed (ASSB) | History and scene investigation, ideally including doll re-enactment |

Assigned to ICD-10 code (SIDS) for US vital statistics database Unexplained Undetermined |

Varies with individual medical examiners and coroners |

| Genetic mutations | SCN5A , SCN1B-4B , SCN4A, long QT syndromes, plus Table 402.4 | May have negative family history secondary to recessive mutations, de novo mutation, or incomplete penetrance | Unknown, perhaps <10% |

* As a percentage of all sudden unexpected infant deaths explained at autopsy.

† As a percentage of all natural causes of sudden unexpected infant deaths explained at autopsy.

ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Version 10; SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome; SUID, sudden unexpected infant death.

Modified from Hunt CE: Sudden infant death syndrome and other causes of infant mortality: diagnosis, mechanisms and risk for recurrence in siblings, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164(3):346–357, 2001.

Table 402.2

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM |

| Arteriovenous malformation |

| Subdural hematoma |

| Seizures |

| Congenital central hypoventilation |

| Neuromuscular disorders (Werdnig-Hoffmann disease) |

| Chiari crisis |

| Leigh syndrome |

| CARDIAC |

| Subendocardial fibroelastosis |

| Aortic stenosis |

| Anomalous coronary artery |

| Myocarditis |

| Cardiomyopathy |

| Arrhythmias (prolonged QT syndrome, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, congenital heart block) |

| PULMONARY |

| Pulmonary hypertension |

| Vocal cord paralysis |

| Aspiration |

| Laryngotracheal disease |

| GASTROINTESTINAL |

| Diarrhea and/or dehydration |

| Gastroesophageal reflux |

| Volvulus |

| ENDOCRINE–METABOLIC |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia |

| Malignant hyperpyrexia |

| Long- or medium-chain acyl coenzyme A deficiency |

| Hyperammonemias (urea cycle enzyme deficiencies) |

| Glutaric aciduria |

| Carnitine deficiency (systemic or secondary) |

| Glycogen storage disease type I |

| Maple syrup urine disease |

| Congenital lactic acidosis |

| Biotinidase deficiency |

| INFECTION |

| Sepsis |

| Meningitis |

| Encephalitis |

| Brain abscess |

| Pyelonephritis |

| Bronchiolitis (respiratory syncytial virus) |

| Infant botulism |

| Pertussis |

| TRAUMA |

| Child abuse |

| Accidental or intentional suffocation |

| Physical trauma |

| Factitious syndrome (formerly Munchausen syndrome) by proxy |

| POISONING (INTENTIONAL OR UNINTENTIONAL) |

| Boric acid |

| Carbon monoxide |

| Salicylates |

| Barbiturates |

| Ipecac |

| Cocaine |

| Insulin |

| Others |

* Recommended terminology now is “brief resolved unexplained events.”

From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy , ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier Saunders, p. 98.

Table 402.3

| IDIOPATHIC |

| Recurrent sudden infant death syndrome |

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM |

| Congenital central hypoventilation |

| Neuromuscular disorders |

| Leigh syndrome |

| CARDIAC |

| Endocardial fibroelastosis |

| Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome |

| Prolonged QT syndrome or other cardiac channelopathy |

| Congenital heart block |

| PULMONARY |

| Pulmonary hypertension |

| ENDOCRINE–METABOLIC |

| See Table 402.2 |

| INFECTION |

| Disorders of immune host defense |

| CHILD ABUSE |

| Filicide or infanticide |

| Factitious syndrome (formerly Munchausen syndrome) by proxy |

From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy , ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier Saunders, p 101.

Epidemiology

SIDS is the 3rd leading cause of infant mortality in the United States, accounting for approximately 7% of all infant deaths. It is the most common cause of postneonatal infant mortality, accounting for 21% of all deaths between 1 mo and 1 yr of age. The annual rate of SIDS in the United States was stable at 1.3-1.4 per 1,000 live births (approximately 7,000 infants per year) before 1992, when it was recommended that infants sleep nonprone as a way to reduce the risk for SIDS. Since then, particularly after initiation of the national Back to Sleep campaign in 1994, the rate of SIDS progressively declined and then leveled off in 2001 at 0.55 per 1,000 live births (2,234 infants). There has been a slower rate of decline since that time; in 2015 the rate was 0.39 per 1,000 live births (1,568 infants). The decline in the number of SIDS deaths in the United States and other countries has been attributed to increasing use of the supine position for sleep. In 1992, 82% of sampled infants in the United States were placed prone for sleep. Although several other countries have decreased prone sleeping prevalence to ≤2%, in the United States in 2010 (the last year for which these data were collected by the National Infant Sleep Position study), 13.5% of infants were still being placed prone for sleep and 11.9% were being placed in the side position. Among black infants, these rates were even higher: 27.6% prone and 16.1% side in 2010.

There is increasing evidence that infant deaths previously classified as SIDS are now being classified by medical examiners and coroners as due to other causes, notably accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed and ill-defined deaths . Between 1994 and 2013, there has been a 7-fold increase in the rate of accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed, from 0.03 to 0.21 deaths per 1,000 live births. There has also been an increase in the rate of ill-defined deaths between 1995 and 2013, from 0.21 to 0.28 deaths per 1,000 live births. These sudden and unexpected infant deaths are primarily associated with unsafe sleeping environments, including prone positioning, sharing a sleep surface with others, and soft bedding in the sleep environment. Based on these trends and the commonality of many of the sleep environment risk factors that are associated with both SIDS and other sleep-related SUID, risk reduction measures that will be later described are applicable to all sleep-related SUID.

Pathology

Although there are no autopsy findings pathognomonic for SIDS and no findings are required for the diagnosis, there are some that are commonly seen on postmortem examination. Petechial hemorrhages are found in 68–95% of infants who died of SIDS and are more extensive than in explained causes of infant mortality. Pulmonary edema is often present and may be substantial. The reasons for these findings are unknown. Infants who died of SIDS have higher levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the cerebrospinal fluid. These increases may be related to VEGF polymorphisms (see “Genetic Risk Factors” later and Table 402.4 ) or might indicate recent hypoxemic events because VEGF is upregulated by hypoxia.

Table 402.4

Modified from Hunt CE, Hauck FR: Sudden infant death syndrome: gene-environment interactions. In Brugada R, Brugada J, Brugada P, editors: Clinical care in inherited cardiac syndromes , Guildford, UK, 2009, Springer-Verlag London.

SIDS infants have several identifiable changes in the lungs and other organs. Nearly 65% of these infants have structural evidence of preexisting, chronic, low-grade asphyxia, and other studies have identified biochemical markers of asphyxia. Some studies have shown carotid body abnormalities, consistent with a role for impaired peripheral arterial chemoreceptor function in SIDS. Numerous studies have shown brain abnormalities that could cause or contribute to an impaired autonomic response to an exogenous stressor, including in the hippocampus and brainstem, the latter being the major area responsible for respiratory and autonomic regulation. The affected brainstem nuclei include the retrotrapezoid nucleus and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, primary sites of central chemoreception and respiratory drive. Abnormalities in both the structure and expression of the PHOX2B gene, which is involved in neuronal maturation, have also been reported in significantly more SIDS infants than controls.

The ventral medulla has been a particular focus for studies in infants who died of SIDS. It is an integrative area for vital autonomic functions including breathing, arousal, and chemosensory function. Some SIDS infants have hypoplasia of the arcuate nucleus and up to 60% have histopathologic evidence of less-extensive bilateral or unilateral hypoplasia. Consistent with the apparent overlap between putative mechanisms for SIDS and for unexpected late fetal deaths, approximately 30% of sudden intrauterine unexplained deaths also have hypoplasia of the arcuate nucleus. Imaging mass spectroscopy of postmortem medullary tissue has identified abnormal expression of 41 peptides, especially in the raphe, hypoglossal, and pyramidal nuclei that include components for developmental neuronal/glial/axonal growth, cell metabolism, cytoarchitecture, and apoptosis. These findings suggest that SIDS infants have abnormal neurologic development contributing to pathogenesis, with the impairments suggesting delayed neurologic maturation.

Neurotransmitter studies of the arcuate nucleus have also identified several receptor abnormalities relevant to state-dependent autonomic control overall and to ventilatory and arousal responsiveness in particular. These deficits include significant decreases in binding to kainate, muscarinic cholinergic, and serotonin (5-HT) receptors. Studies of the ventral medulla have identified morphologic and biochemical deficits in 5-HT neurons and decreased γ-aminobutyric acid receptor A receptor binding in the medullary serotonergic system. Immunohistochemical analyses reveal an increased number of 5-HT neurons and an increase in the fraction of 5-HT neurons showing an immature morphology, suggesting a failure or delay in the maturation of these neurons. High neuronal levels of interleukin (IL)-1β are present in the arcuate and dorsal vagal nuclei in SIDS infants compared with controls, perhaps contributing to molecular interactions affecting cardiorespiratory and arousal responses.

The neuropathologic data provide compelling evidence for altered 5-HT homeostasis, creating an underlying vulnerability contributing to SIDS. 5-HT is an important neurotransmitter, and the 5-HT neurons in the medulla project extensively to neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord that influence respiratory drive and arousal, cardiovascular control including blood pressure, circadian regulation, and non–rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, thermoregulation, and upper airway reflexes. Decreases in 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptor immunoreactivity have been observed in the dorsal nucleus of the vagus, solitary nucleus, and ventrolateral medulla. There are extensive serotoninergic brainstem abnormalities in SIDS infants, including increased 5-HT neuronal count, a lower density of 5-HT1A receptor-binding sites in regions of the medulla involved in homeostatic function, and a lower ratio of 5-HT transporter (5-HTT) binding density to 5-HT neuronal count in the medulla. Male SIDS infants have lower receptor-binding density than do female SIDS infants. Overall, these 5-HT–related studies suggest that the synthesis and availability of 5-HT are decreased within 5-HT pathways, and medullary tissue levels of 5-HT and its primary biosynthetic enzyme (tryptophan hydroxylase) are lower in SIDS infants compared with age-matched controls.

Environmental Risk Factors

Declines of 50% or more in rates of SIDS in the United States and around the world have occurred following national education campaigns directed at reducing risk factors associated with SIDS (Table 402.5 ). Although many risk factors are nonmodifiable and most of the modifiable factors have not changed appreciably, self-reported maternal smoking prevalence during pregnancy has decreased by 25% in the past decade in the United States.

Table 402.5

Nonmodifiable Environmental Risk Factors

Lower socioeconomic status has consistently been associated with higher risk, although SIDS affects infants from all social strata. In the United States, African-American, American Indian, and Alaska Native infants are 2-3 times more likely than white infants to die of SIDS, whereas Asian, Pacific Islander, and Hispanic infants have the lowest incidence. Some of this disparity may be related to the higher concentration of poverty and other adverse environmental factors found within some, but not all, of the communities with higher incidence.

Infants are at greatest risk of SIDS at 1-4 mo of age, with most deaths having occurred by 6 mo. This characteristic age has decreased in some countries as the SIDS incidence has declined, with deaths occurring at earlier ages and with a flattening of the peak age incidence. Similarly, the commonly observed winter seasonal predominance of SIDS has declined or disappeared in some countries as prone prevalence has decreased, supporting prior findings of an interaction between sleep position and factors more common in colder months (overheating as a consequence of elevated interior temperatures or bundling with blankets and heavy clothing, or infection). Male infants are 30–50% more likely to be affected by SIDS than are female infants.

Modifiable Environmental Risk Factors

Pregnancy-Related Factors

An increased SIDS risk is associated with numerous obstetric factors, suggesting that the in utero environment of future SIDS infants is suboptimal. SIDS infants are more commonly of higher birth order, independent of maternal age, and of gestations after shorter interpregnancy intervals. Mothers of SIDS infants generally receive less prenatal care and initiate care later in pregnancy. In addition, low birthweight, preterm birth, and slower intrauterine and postnatal growth rates are risk factors.

Cigarette Smoking

There is a major association between intrauterine exposure to cigarette smoking and risk for SIDS. The incidence of SIDS was 2-3 times greater among infants of mothers who smoked in studies conducted before SIDS risk-reduction campaigns and 4 times higher in studies after implementation of risk-reduction campaigns. The risk of death is progressively greater as daily cigarette use increases. The effects of smoking by the infant's father and other household members are more difficult to interpret because they are highly correlated with maternal smoking. There appears to be a small independent effect of paternal smoking, but data on other household members have been inconsistent. The effect of prenatal smoking on SIDS risk is not believed to be caused by lower birthweight, which is often found among infants of smoking mothers.

It is very difficult to assess the independent effect of infant exposure to environmental tobacco smoke because parental smoking behaviors during and after pregnancy are also highly correlated. However, a 2-fold increased risk of SIDS is found for infants exposed only to postnatal maternal environmental tobacco smoke. There is a dose-response for the number of household smokers, number of people smoking in the same room as the infant, and the number of cigarettes smoked. These data suggest that keeping the infant free of environmental tobacco smoke can further reduce an infant's risk of SIDS.

Drug and Alcohol Use

Most studies link maternal prenatal drug use, especially opiates, with an increased risk of SIDS, ranging from a 2- to 15-fold increased risk. Studies looking at the association between maternal alcohol use prenatally or postnatally and SIDS have conflicting results. In one study of Northern Plains Indians, periconceptional alcohol use and binge drinking in the 1st trimester were associated with a 6-fold and an 8-fold increased risk of SIDS, respectively. A Danish cohort study found that mothers admitted to the hospital for an alcohol- or a drug-related disorder at any time before or after the birth of their infants had a 3-time higher risk of their infant dying from SIDS, and a Dutch study reported that maternal alcohol consumption in the 24 hr before the infant died carried an 8-fold increased risk of SIDS. Siblings of infants with fetal alcohol syndrome have a 10-fold increased risk of SIDS compared with controls. Although there are conflicting reports of illicit drug use and SIDS overall, prenatal drug use, especially opiates, is associated with an increased risk of SIDS, ranging from 2- to 15-fold. Data on cannabis use and SIDS are extremely limited, with only one study from New Zealand reporting results for postpartum maternal use. This study found that nighttime cannabis use was associated with a 2-fold increased risk of SIDS, whereas daytime use was not associated with increased risk.

Infant Sleep Environment

Sleeping prone has consistently been shown to increase the risk of SIDS. As rates of prone positioning have decreased in the general population, the odds ratios for SIDS in infants still sleeping prone have increased. The highest risk of SIDS occurs in infants who are usually placed nonprone but placed prone for last sleep (“unaccustomed prone”) or found prone (“secondary prone”). The “unaccustomed prone” position may be more likely to occur in daycare or other settings outside the home and highlights the need for all infant caretakers to be educated about appropriate sleep positioning.

Side-Sleeping: Significant Risk Factor.

The initial SIDS risk-reduction campaign recommendations considered side-sleeping to be nearly equivalent to the supine position in reducing the risk of SIDS. Subsequent studies documented that side-sleeping infants were twice as likely to die of SIDS as infants sleeping supine. This increased risk may be related to the relative instability of the position. Infants who are placed on their side and roll to prone are at exceptional risk, with one study finding they are almost 9 times more likely to die of SIDS than those placed supine. Although the majority of SIDS occurrences are still associated with infants being found prone, a higher proportion of SIDS is now attributed to being placed on the side for sleeping than for being placed prone. The current recommendations call for supine position for sleeping for all infants except those few with specific medical conditions for which recommending a different position may be justified, in infants with anatomic or functional upper airway compromise.

Many parents and healthcare providers were initially concerned that supine sleeping would be associated with an increase in adverse consequences, such as difficulty sleeping, vomiting, or aspiration. However, evidence suggests that the risk of regurgitation and choking is highest for prone-sleeping infants. Some newborn nursery staff still tend to favor side positioning, which models inappropriate infant care practice to parents. Infants sleeping on their backs do not have more episodes of cyanosis or apnea, and reports of apparent life-threatening events actually decreased in Scandinavia after increased use of the supine position. Among infants in the United States who maintained the same sleep position at 1, 3, and 6 mo of age, no clinical symptoms or reasons for outpatient visits (including fever, cough, wheezing, trouble breathing or sleeping, vomiting, diarrhea, or respiratory illness) were more common in infants sleeping supine or on their sides compared with infants sleeping prone. Three symptoms were actually less common in infants sleeping supine or on their sides: fever at 1 mo, stuffy nose at 6 mo, and trouble sleeping at 6 mo. Outpatient visits for ear infection were less common at 3 and 6 mo for infants sleeping supine and also less common at 3 mo for infants sleeping on their side. These results provide reassurance for parents and healthcare providers and should contribute to universal acceptance of supine as the safest and optimal sleep position for infants.

Soft Sleep Surfaces and Soft or Loose Bedding.

Soft sleep surfaces and soft or loose bedding , including comforters, pillows, bumper pads, stuffed animals, mattress toppers, pillow-top mattresses, sheepskins, polystyrene bean pillows, and old or soft mattresses, are associated with increased risk of SIDS. Infant sleep positioners, including pillows and wedges, which are often marketed to hold infants on their side or at an angle to help with reflux, are also not recommended. Based on available research, swaddling infants , or wrapping them in a blanket, is not recommended as a strategy to reduce SIDS. Infants who roll to the prone position while swaddled are at particularly high risk of SIDS. Wearable blankets, which may have a built-in swaddle, are an acceptable alternative.

Overheating.

Overheating, based on indicators such as higher room temperature, a history of fever, sweating, and excessive clothing or bedding, has been associated with increased risk of SIDS. Some studies have identified an interaction between overheating and prone sleeping, with overheating increasing the risk of SIDS only when infants are sleeping prone. Higher external environmental temperatures have not been associated with increased SIDS incidence in the United States.

Bed Sharing.

Several studies have implicated bed sharing as a risk factor for SIDS. Bed sharing is particularly hazardous when other children are in the same bed, when the parent is sleeping with an infant on a couch, sofa, or other soft or confining sleeping surface, when the mother is a smoker, and when the bed sharer has used alcohol or arousal-altering drugs or medications. Infants younger than 4 mo of age are at increased risk even when mothers are nonsmokers. A meta-analysis of 19 studies found that low-risk infants (i.e., those who were breastfed and never exposed to cigarette smoke in utero or after birth) still had a 5-fold increased risk of SIDS until the age of 3 mo if bed sharing. Risk is also increased with longer duration of bed sharing during the night, whereas returning the infant to the infant's own crib has not been associated with increased risk. Room sharing without bed sharing is associated with lower SIDS rates and is therefore recommended.

Infant Feeding Care Practices and Exposures

Breastfeeding is Associated With a Lower Risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

A meta-analysis found that breastfeeding was associated with a 45% reduction in SIDS after adjusting for confounding variables and that this protective effect increased for exclusive breastfeeding compared with partial breastfeeding.

Pacifier (dummy) use is associated with a lower risk of SIDS in the majority of studies. Although it is not known if this is a direct effect of the pacifier itself or from associated infant or parental behaviors, use of the pacifier is protective even if it is dislodged during sleep. Concerns have been expressed about recommending pacifiers as a means of reducing the risk of SIDS for fear of adverse consequences, particularly interference with breastfeeding. However, well-designed clinical trials have found no association between pacifiers and breastfeeding duration.

Upper respiratory tract infections have generally not been found to be an independent risk factor for SIDS, but these and other minor infections may still have a role in the causal pathway of SIDS when other risk factors are present. Risk for SIDS has been found to be increased after illness among prone sleepers, those who were heavily wrapped, and those whose heads were covered during sleep.

No adverse association between immunizations and SIDS has been found. Indeed, SIDS infants are less likely to be immunized than control infants, and, in immunized infants, no temporal relationship between vaccine administration and death has been identified. In a meta-analysis of case-control studies that adjusted for potentially confounding factors, the risk of SIDS for infants immunized with diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis was half that for nonimmunized infants.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Rates Remain Higher Among American Indians, Alaska Natives, and African Americans.

This may be due, in part, to group differences in adopting supine sleeping or other risk-reduction practices. Greater efforts are needed to address this persistent disparity and to ensure that SIDS risk-reduction education reaches all parents and other care providers, including other family members and personnel at daycare centers.

Genetic Risk Factors

As summarized in Table 402.4 , there are numerous genetic differences identified in infants who died of SIDS compared with healthy infants and to infants dying from other causes. Polymorphisms occurring at higher incidence in SIDS infants compared with controls include multiple cardiac ion channelopathy genes that are proarrhythmic, autonomic nervous system development genes, proinflammatory genes related to infection and immunity, and several 5-HT genes.

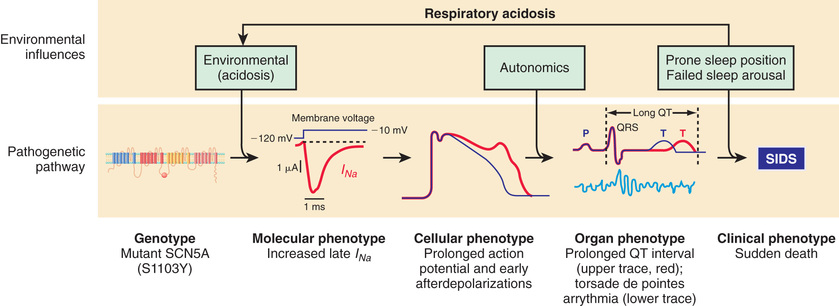

Multiple studies have established the importance of a pathway to SIDS that involves cardiac sodium or potassium channel dysfunction resulting in either long QT syndrome (LQTS) or other proarrhythmic conditions. LQTS is a known cause of sudden unexpected death in children and adults as the result of a prolonged cardiac action potential causing either increased depolarization or decreased repolarization current (Fig. 402.1 ). The first evidence supporting a causal role for LQTS in SIDS was a large Italian study in which a corrected QT interval >440 msec on an electrocardiogram performed on days 3-4 of life was associated with an odds ratio of 41 for SIDS. Several case reports have subsequently provided proof of concept that cardiac channelopathy polymorphisms are associated with SIDS. LQTS is associated with polymorphisms related mainly to gain-of-function mutations in the sodium channel gene (SCN5A) that encode critical channel pore-forming α subunits or essential channel-interacting proteins. LQTS also is associated with mainly loss-of-function polymorphisms in potassium channel genes. Short QT syndrome (SQTS) is more recently recognized as another cause of life-threatening arrhythmia or sudden death, often during rest or sleep. Gain-of-function mutations in genes including KCNH2 and KCNQ1 have been causally linked to SQTS, and some of these deaths have occurred in infants, suggesting that SQTS may also be causally linked to SIDS.

In addition to LQTS and SQTS, the other cardiac ion-related channelopathy polymorphisms are also proarrhythmic, including Brugada syndrome (BrS1, BrS2) and catecholaminergic paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia (CPVT1). Collectively, these mutations in cardiac ion channels provide a lethal proarrhythmic substrate in some infants (see Fig. 402.1 ) and may account for 10% or more of SIDS cases.

Impaired central respiratory regulation is an important biologic abnormality in SIDS, and genetic polymorphisms have been identified in SIDS infants that affect both serotonergic and adrenergic neurons. Monoamine oxidase A metabolizes both of these neurotransmitters, and a recent study has observed a high association between SIDS and low expressing alleles in males, perhaps contributing to the higher incidence of SIDS in males. Many genes are involved in the control of 5-HT synthesis, storage, membrane uptake, and metabolism. Polymorphisms in the promoter region of the 5-HTT protein gene occur with greater frequency in SIDS than control infants. The long “L” allele increases effectiveness of the promoter and reduces extracellular 5-HT concentrations at nerve endings, compared with the short “S” allele. White, African-American, and Japanese SIDS infants were more likely than ethnicity-matched controls to have the “L” (long) allele, and there was also a negative association between SIDS and the S/S genotype. The L/L genotype was associated with increased 5-HT transporters on neuroimaging and postmortem binding studies. However, in a large San Diego dataset of SIDS infants, no relationship was found between SIDS and the L allele or the LL genotype.

An association has also been observed between SIDS and a 5-HTT intron 2 polymorphism, which differentially regulates 5-HTT expression. There were positive associations between SIDS and the intron 2 genotype distributions in African-American infants who died of SIDS, compared with African-American controls. The human FEV gene is specifically expressed in central 5-HT neurons in the brain, with a predicted role in specification and maintenance of the serotoninergic neuronal phenotype. An insertion mutation has been identified in intron 2 of the FEV gene, and the distribution of this mutation differs significantly in SIDS compared with control infants.

Molecular genetic studies in SIDS victims have also identified mutations pertinent to early embryologic development of the autonomic nervous system (see Table 402.4 ). Protein-changing mutations related to the PHOX2a, RET, ECE1, TLX3, and EN1 genes have been identified, particularly in African-American infants who died of SIDS. Eight polymorphisms in the PHOX2B gene occurred significantly more frequently in SIDS compared with control infants. One study has reported an association between SIDS and a distinct tyrosine hydroxylase gene (THO1) allele, which regulates gene expression and catecholamine production.

Multiple studies have observed altered expression of genes involved in the inflammatory process and immune system regulation. Differences in SIDS infants, compared with controls, have been reported for 2 complement C4 genes. Some SIDS infants have loss-of-function polymorphisms in the gene promoter region for IL-10, another antiinflammatory cytokine. IL-10 polymorphisms associated with decreased IL-10 levels could contribute to SIDS by delaying initiation of protective antibody production or reducing capacity to inhibit inflammatory cytokine production. However, other studies have not found differences in IL-10 genes in SIDS infants compared with age-matched controls.

An association has been reported between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the proinflammatory gene encoding IL-8 and SIDS infants found prone, compared with SIDS infants found in other sleep positions. IL-1 is another proinflammatory gene, and a higher prevalence of the IL-1 receptor antagonist, which would predispose to higher risk for infection, has been reported in infants who died of SIDS. Significant associations with SIDS are also reported for polymorphisms in VEGF, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα). These 3 cytokines are proinflammatory, and these gain-of-function polymorphisms would result in increased inflammatory response to infectious or inflammatory stimuli and hence contribute to an adverse imbalance between proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines. As apparent proof of principle, elevated levels of IL-6 and VEGF have been reported from cerebrospinal fluid in SIDS infants. There were no group differences in the IL6-174G/C polymorphism in a Norwegian SIDS study, but the aggregate evidence nevertheless suggested an activated immune system in SIDS and implicated genes involved in the immune system. Almost all SIDS infants in one study had positive histories for prone sleeping and fever prior to death and positive HLA-DR expression in laryngeal mucosa, and high HLA-DR expression was associated with high levels of IL-6 in cerebrospinal fluid.

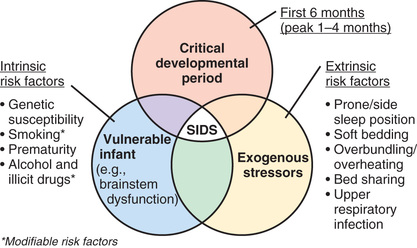

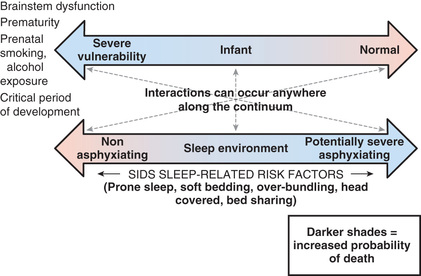

Gene-Environment Interactions

Interactions between genetic and environmental risk factors determine the actual risk for SIDS in individual infants (Fig. 402.2 ). Equally important, there is a dynamic interaction between genetic or intrinsic vulnerability and the sleep environment (Fig. 402.3 ). There appears to be an interaction between prone sleep position and impaired ventilatory and arousal responsiveness. Facedown or nearly facedown sleeping does occasionally occur in prone-sleeping infants, but normal healthy infants arouse before such episodes become life-threatening. However, infants with insufficient arousal responsiveness to hypoxia may be at risk for sudden death from resulting episodes of airway obstruction and asphyxia. There may also be links between modifiable risk factors (such as soft bedding, prone sleep position, and thermal stress) and genetic risk factors, such as ventilatory and arousal abnormalities and temperature or metabolic regulation deficits. Cardiorespiratory control deficits could be related to 5-HTT polymorphisms, for example, or to polymorphisms in genes pertinent to autonomic nervous system development. Affected infants could be at increased risk for sleep-related hypoxemia and hence more susceptible to adverse effects associated with unsafe sleep position or bedding. Infants at increased risk for sleep-related hypoxemia could also be at greater risk for fatal arrhythmias in the presence of a cardiac ion channelopathy polymorphism.

In >50% of SIDS victims, recent febrile illnesses, often related to upper respiratory infection, have been documented (see Table 402.5 ). Benign infections might increase risk for SIDS if interacting with genetically determined proinflammatory or impaired immune responses. Deficient inflammatory responsiveness can also occur as a result of mast cell degranulation, which has been reported in SIDS infants. This is consistent with an anaphylactic reaction to a bacterial toxin, and some family members of SIDS infants also have mast cell hyperreleasability and degranulation, suggesting that increased susceptibility to an anaphylactic reaction is another genetic factor influencing fatal outcomes to otherwise minor infections. Interactions between upper respiratory infections or other minor illnesses and factors such as prone sleeping might also play a role in the pathogenesis of SIDS.

The increased risk of SIDS associated with fetal and postnatal exposure to cigarette smoke may be related at least in part to genetic or epigenetic factors, including those affecting brainstem autonomic control. Infant studies document decreased ventilatory and arousal responsiveness to hypoxia following fetal nicotine exposure, and impaired autoresuscitation after apnea has been associated with postnatal nicotine exposure. Decreased brainstem immunoreactivity to selected protein kinase C and neuronal nitric oxide synthase isoforms occurs in rats exposed to cigarette smoke prenatally, another potential cause of impaired hypoxic responsiveness. Smoking exposure also increases susceptibility to viral and bacterial infections and increases bacterial binding after passive coating of mucosal surfaces with smoke components, implicating interactions between smoking, cardiorespiratory control, and immune status. Flavin-monooxygenase 3 (FMO3) is one of the enzymes that metabolizes nicotine, and a polymorphism has recently been identified that occurs more frequently in SIDS infants compared with controls and more frequently in infants whose mothers reported heavy smoking (see Table 402.4 ). This polymorphism would result in increased nicotine levels and hence is a potential genetic risk factor for SIDS in infants exposed to cigarette smoke.

In infants with a cardiac ion channelopathy, risk for a fatal arrhythmia during sleep may be substantially enhanced by predisposing perturbations that increase electrical instability. These perturbations could include REM sleep with bursts of vagal and sympathetic activation, minor respiratory infections, or any other cause of sleep-related hypoxemia or hypercarbia, especially those resulting in acidosis. The prone sleeping position is associated with increased sympathetic activity.

Infant Groups at Increased Risk for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Subsequent Siblings of an Infant who Died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

The next-born siblings of first-born infants dying of any noninfectious natural cause are at significantly increased risk for infant death from the same cause, including SIDS. The relative risk is 9.1 for the same cause of recurrent death versus 1.6 for a different cause of death. The relative risk for recurrent SIDS (range: 5.4-5.8) is similar to the relative risk for non-SIDS causes of recurrent death (range: 4.6-12.5). The risk for recurrent infant mortality from the same cause as in the index sibling thus appears to be increased to a similar degree in subsequent siblings for both explained causes and for SIDS. This increased risk for recurrent SIDS in families is consistent with genetic risk factors interacting with environmental risk factors (see Tables 402.4 and 402.5 and Figs. 402.2 and 402.3 ). However, recurrent SIDS in a family should also alert the clinician to consider other causes of sudden and unexpected death (see Table 402.2 ).

Prematurity

Despite reductions of more than 50% in SIDS and SUID among infants born preterm since initiation of the Back to Sleep campaign in the United States in 1994, the risk of death remains significantly higher for these infants than for those born full term. The risk increases as gestational age decreases. Compared with infants born at 37-42 wk, the odds ratio for SIDS is greatest for infants born at 24-28 wk gestation (2.57, 95% confidence interval 2.08, 3.17). Even at 33-36 wk gestational age at birth, the risk of SIDS remains significantly increased compared with infants born at term. The peak chronologic age for SIDS is later in infants born preterm; chronologic age at death is inversely proportional to gestational age at birth.

Although infants born preterm are at increased risk for apnea, apnea of prematurity per se does not seem to be related to the increased SIDS risk. This increased risk is instead likely related in part to immaturity of brainstem responses; physiologic studies have found impaired cortical arousals, lower baroreflex sensitivity, and impaired autonomic control. Sociodemographic and environmental risk are also important. Infants born preterm have more sociodemographic risk factors overall than infants born at term. In addition, infants born preterm are more likely to be placed prone at home; this may be in part because these infants are often placed prone while mechanically ventilated in the neonatal intensive care unit, and safe sleep practices are often not well-modeled during the remainder of the NICU admission. The association between prone position and SIDS in preterm and low birthweight infants is equal or greater than this association in infants born full term.

Physiologic Studies

Physiologic studies have been performed in healthy infants in early infancy, a few of whom later died of SIDS. Physiologic studies have also been performed on infant groups who were believed to be at increased risk for SIDS, especially those with brief resolved unexplained events (BRUE; formerly known as apparent life-threatening events; Chapter 403 ) and subsequent siblings of infants who died of SIDS. In the aggregate, these studies have indicated brainstem abnormalities in the neuroregulation of cardiorespiratory control or other autonomic functions and are consistent with the autopsy findings and genetic studies in infants who died of SIDS (see “Pathology ” and “Genetic Risk Factors ”). In addition to physiologic abnormalities in chemoreceptor sensitivity, other observed physiologic abnormalities have been found in respiratory pattern, control of heart and respiratory rate or variability, and asphyxic arousal responsiveness. A deficit in arousal responsiveness may be a necessary prerequisite for SIDS to occur but may be insufficient to cause SIDS in the absence of other genetic or environmental risk factors. Autoresuscitation (gasping) is a critical component of the asphyxic arousal response, and a failure of autoresuscitation in SIDS infants may be the final and most devastating physiologic failure. In one study, most normal full-term infants younger than 9 postnatal wk of age aroused in response to mild hypoxia, whereas only 10–15% of infants older than 9 wk of age aroused. These data suggest that ability to arouse to mild to moderate hypoxic stimuli may be at a nadir at the age range of greatest risk for SIDS.

The ability to shorten the QT interval as heart rate increases appears to be impaired in some infants who died of SIDS, suggesting that such infants may be predisposed to ventricular arrhythmia. Although this is consistent with the observations of cardiac ion channel gene polymorphisms in some SIDS infants (see Table 402.4 ), there are no antemortem QT interval data for these infants that confirm the importance of this finding. Infants who were studied physiologically and then died of SIDS a few weeks later had higher heart rates and lower heart rate variability in all sleep–wake states and diminished heart rate variability during wakefulness. These SIDS infants also had longer QT intervals than control infants during both REM and non-REM sleep, especially in the late hours of the night when most SIDS likely occurs. However, the QT interval exceeded 440 msec in only one of these SIDS infants.

It has been postulated that the decreased heart rate variability and increased heart rate observed in infants who later died of SIDS may in part be related to decreased vagal tone, perhaps from vagal neuropathy or brainstem damage in areas responsible for parasympathetic cardiac control. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability is 1 way to assess sympathetic and parasympathetic cardiac control. In a comparison of heart rate power spectra before and after obstructive apneas in clinically asymptomatic infants, infants later dying of SIDS did not have the decreases in low-frequency to high-frequency power ratios observed in infants who survived. Some infants may thus have different autonomic responsiveness to obstructive apnea, perhaps indicating impaired autonomic nervous system control associated with higher vulnerability to external or endogenous stresses, and hence reduced electrical stability of the heart; this may create a vulnerability for SIDS.

Home cardiorespiratory monitors with memory capability have recorded the terminal events in some infants who died of SIDS. However, these recordings did not include pulse oximetry and could not identify obstructed breaths due to reliance on transthoracic impedance for breath detection. In most instances, there was sudden and rapid progression of severe bradycardia that was either unassociated with central apnea or appeared to occur too soon to be explained by the central apnea. These observations are consistent with an abnormality in autonomic control of heart rate variability or with obstructed breaths resulting in bradycardia or hypoxemia and associated with impaired autoresuscitation or arousal.

Clinical Strategies

Home Monitoring

SIDS cannot be prevented in individual infants because it is not possible to identify prospective SIDS infants, and no effective intervention has been established even if infants at risk could be prospectively identified. Studies of cardiorespiratory pattern or other autonomic abnormalities do not have sufficient sensitivity and specificity to be clinically useful as screening tests. Home electronic surveillance using existing technology does not reduce the risk of SIDS. Although a prolonged QT interval in an infant may be treated if diagnosed, neither the role of routine postnatal electrocardiographic screening, the cost-effectiveness of diagnosis and treatment, nor the safety of treatment in infants has been established (see Chapter 456 ). Parental electrocardiographic screening is not helpful, in part because spontaneous mutations are common.

Reducing the Risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Reducing risk behaviors and increasing protective behaviors among infant caregivers to achieve further reductions and eventual elimination of SIDS is a critical goal. Recent plateaus in placing infants supine for sleep in the United States at approximately 75% for all races and only 56% for African Americans are cause for concern and require renewed educational efforts. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines to reduce the risk of SIDS were updated in 2016 and are aimed at reducing the risk of all sudden and unexpected sleep-related infant deaths. The guidelines are appropriate for most infants, but physicians and other healthcare providers might, on occasion, need to consider alternative approaches. The major components of the AAP guidelines are:

- • Full-term and premature infants should be placed for sleep in the supine position. There are no adverse health outcomes from supine sleeping. Side-sleeping is not recommended.

- • Infants should be put to sleep on a firm mattress. Waterbeds, sofas, soft mattresses, or other soft surfaces should not be used. In addition, car seats, strollers, swings, and other sitting devices should not be used for sleeping. Sleeping in an upright position can lead to gastroesophageal reflux or upper airway obstruction from head flexion.

- • Breastfeeding is recommended. If possible, mothers should exclusively breastfeed or feed with expressed human milk until the infant is 6 mo of age.

- • It is recommended that infants sleep in the same room as their parents but in their own crib or bassinet that conforms to the safety standards of the Consumer Product Safety Commission. Placing the crib or bassinet near the mother's bed facilitates nursing and contact. If parents bring the infant into the adult bed for feeding or comforting, the infant should be returned to a separate sleep surface when the parents are ready for sleep.

- • Soft materials and loose bedding in the infant's sleep environment—over, under, or near the infant—should be avoided. These include pillows, comforters, quilts, sheepskins, bumper pads, and stuffed toys. Sleep clothing, such as a wearable blanket, can be used in place of blankets.

- • Consider offering a pacifier at bedtime and naptime. The pacifier should be used when placing the infant down for sleep and need not be reinserted once it falls out. For breastfed infants, delay introduction of the pacifier until breastfeeding is well established.

- • Mothers should not smoke during pregnancy or after birth, and infants should not be exposed to second-hand smoke.

- • Mothers should avoid alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy and after birth.

- • Avoid overheating and overbundling. The infant should be lightly clothed for sleep and the thermostat set at a comfortable temperature.

- • Pregnant women should obtain regular prenatal care, following guidelines for prenatal visits.

- • Infants should be immunized in accordance with recommendations of the AAP and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There is no evidence that immunizations increase the risk of SIDS. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that immunizations may have a protective effect against SIDS.

- • Avoid the use of commercial devices that are inconsistent with safe sleep recommendations. Devices advertised to maintain sleep position, “protect” a bed sharing infant, or reduce the risk of rebreathing are not recommended because there is no evidence to support their safety or efficacy.

- • Home cardiorespiratory and/or O2 saturation monitoring may be of value for selected infants who have extreme instability, but there is no evidence that monitoring decreases the incidence of SIDS, and it is therefore not recommended for this purpose.

- • Infants should have some time in the prone position (tummy time) while awake and observed. Alternating the placement of the infant's head, as well as orientation in the crib, can also minimize the risk of head flattening from supine sleeping (positional plagiocephaly).

- • Swaddling cannot be recommended as a strategy to reduce SIDS. If infants are placed in a swaddle it should be using a light blanket that is snug around the shoulders but looser around the hips to avoid hip dysplasia. Swaddled infants should always be placed supine, and once infants can roll to the prone position all swaddling should be discontinued.

- • Healthcare professionals, staff in newborn nurseries and neonatal intensive care units, and child care providers should adopt the SIDS reduction recommendations beginning at birth to model safe sleep for caregivers.

- • Media and manufacturers should follow safe sleep guidelines in their messaging and advertising.

- • The national “Safe to Sleep” campaign should be continued with additional emphasis placed on strategies to increase breastfeeding while decreasing bed sharing and tobacco smoke exposure. The campaign should continue to have a special focus on the groups with higher rates of SIDS, including educational strategies tailored to individual racial-ethnic groups. Secondary care providers need to be targeted to receive these educational messages, including daycare providers, grandparents, foster parents, and baby sitters. Efforts should also be made to introduce sleep recommendations before pregnancy and ideally in secondary school curricula.

- • Research and surveillance should be continued on the risk factors, causes, and pathophysiologic mechanisms of SIDS and other sleep-related SUID, with the ultimate goal of preventing these deaths entirely. Federal and private funding agencies need to remain committed to this research.

Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse

Sarah Vepraskas

Epidemiology

Sudden unexplained postnatal collapse (SUPC) is a rare but potentially fatal event in an otherwise healthy term newborn that includes any condition resulting in temporary or permanent cessation of breathing or cardiorespiratory failure. SUPC results in death in about half of the infants and significant impairment in many survivors.

SUPC, in some definitions, includes both severe apparent life-threatening events (currently referred to as BRUE) and SUID, occurring within the 1st postnatal week of life. In general, SUID is a term that encompasses all SUIDs. Some BRUEs may be low risk and require simple interventions such as positional changes, brief stimulation, or procedures to resolve the airway obstruction; these seemingly more benign events are in contrast to SUPC, which can be potentially fatal.

The definition of SUPC used in the AAP report on safe sleep and skin-to-skin care is by the British Association of Perinatal Medicine and includes any term or near-term (defined as >35 wk gestation) infant who meets the following criteria: (1) is well at birth (normal 5-min Apgar and deemed well enough for routine care), (2) collapses unexpectedly in a state of cardiorespiratory extremis such that resuscitation with intermittent positive-pressure ventilation is required, (3) collapses within the 1st 7 days of life, and (4) either dies, goes on to require intensive care, or develops encephalopathy. A majority of reported events occur within 2 hr after birth, often at the time of the 1st breastfeeding attempt. Other potential medical conditions that place infants at higher risk, such as prematurity (<35 wk gestation), perinatal asphyxia, sepsis, or congenital malformations, should be excluded for SUPC to be diagnosed.

The incidence of SUPC is estimated to be 2.6-133 per 100,000 live births. However, the incidence varies widely because there is a lack of consensus on the definition, differing inclusion and exclusion criteria exist, and no standardized reporting system. In addition, a consensus for coding SUPC has not been established, which likely contributes to it being underreported.

The published estimations of SUPC are lower than what occur in the hospital and reflect only the critical events. When a defined time for the SUPC event is described, approximately one third of reported events occur during the 1st 2 hr, another one third between 2 and 24 hr, and another one third between 1 and 7 days after birth.

Pathogenesis

The mechanism for SUPC is not completely known. Many of the events may be related to suffocation or entrapment. It is also hypothesized that the transition from fetal to extrauterine life could make the newborn more vulnerable during the 1st hr of life. During birth there is an initial surge of adenosine and prostaglandins, followed by a postnatal surge of catecholamines. A healthy newborn baby is aroused and awake after birth and starts continuous breathing movements. Shortly after birth, there is a rapid decrease in the inhibitory neuromodulator adenosine as the partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood rapidly increases and contributes to the increased activity in the newborn infant compared with the fetus. Following the hormone surges, there is a period of diminished responsiveness to external stimuli and increased vagal tone; it is possible that autonomic instability could make infants vulnerable during this transitioning period.

It is also possible that impaired cardiorespiratory control due to hypoxic ischemic injury occurring days before birth could contribute to fatal cases of SUPC. Mild gliosis in brainstem areas involved in cardiorespiratory control was found at autopsy of 7 infants with SUPC. However, there are insufficient data to support an association between in utero hypoxic events and SUPC.

Risk Factors

Many of reported SUPC cases occur while the infant is in prone position, during skin-to-skin contact (SSC) with their mothers. SSC is traditionally defined as beginning at birth and lasting continually until the end of the first breastfeeding.

Additional risk factors for SUPC include the first breastfeeding attempt, cosleeping, a mother in the episiotomy position, a primiparous mother, and parents left alone with baby during the 1st hr after birth.

SSC and rooming-in have become common practice for healthy newborns and align with Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), a global program launched by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) to encourage and recognize hospitals and birthing centers that promote the optimal level of care for infant feeding and mother/baby bonding. The BFHI recognizes and awards birthing facilities that successfully implement the “Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding,” with step 4 being to initiate breastfeeding within 1 hr of birth and step 7 recommending the practice of rooming-in. The AAP clinical report on safe sleep and SSC in the newborn period both reviews the evidence supporting SSC and rooming-in during the newborn period, while addressing the safety concerns and providing suggestions to improve safety after delivery. The literature supporting SSC also emphasizes the importance that mother and baby should not be left unattended during this early period.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of SUPC should be made only after other pathologic causes are excluded. One study consisting of 45 cases of unexpected collapse in newborns found that one third of infants had an underlying pathologic or clinical condition, such as sepsis, ductal dependent congenital heart disease, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, intracranial hemorrhage, or a metabolic disorder (1 infant with Zellweger syndrome and another infant with an unidentified metabolic disorder). Additional etiologies to consider include airway obstruction, pneumonia, respiratory distress syndrome, hypoglycemia, vascular thrombosis or embolism, and pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. The differential diagnosis of SUPC is broad, and many conditions overlap with the differential diagnoses for BRUE (Chapter 403 ), SUID, and SIDS.

For those infants who survive the event, testing to screen for an underlying pathology should be performed and tailored to the specific details of each case. A thorough history and physical exam should be performed prior to initiating the diagnostic workup to assist one in focusing the evaluation. Laboratory tests to consider include electrolytes; metabolic evaluation including glucose, ammonia, and lactate; an infectious evaluation including blood cultures, urinalysis, and urine cultures; and CSF analysis with CSF culture. Chest radiography, neuroimaging, echocardiogram, electrocardiogram, and comprehensive metabolic screening (included as part of the newborn screen in most states) could also be useful diagnostic tools. Postmortem examination in the case of death from presumed SUPC should also be considered because underlying etiology of the event may be discovered during autopsy.

Outcome

Approximately half of SUPC cases are thought to result in death. A review of 17 and 45 SUPC cases in Germany and United Kingdom showed a mortality rate of 42% and 27%, respectively. In the German study, almost two-thirds of the surviving cases had neurologic deficits, and in the United Kingdom study, one third of infants either died or had residual neurologic deficits. Rates of death and neurologic abnormalities reported in the 2 aforementioned studies are comparable with other available case reports.

Treatment

There are data suggesting that hypothermia treatment may improve neurologic outcomes after a SUPC event that results in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) (see Chapter 120.4 ). The hypothermia treatment of 4 patients with HIE after SUPC were deemed successful, with follow-up at 24 mo having 3 children being developmentally normal and 1 child having mild cerebral palsy.

Prevention

The known risk factors for SUPC can be used to aid in preventive efforts. Specifically, safety during SSC and rooming-in should be emphasized.

Initiatives developed to standardize the procedure for immediate postnatal SSC have not proven to reduce the risk of SUPC. Frequent assessments of newborns should be performed, including observation of breathing, activity, color, tone, and position, to ensure they are in a position to avoid obstructive breathing or events leading to SUPC. It has also been suggested that continuous monitoring by trained staff members be done during SSC. However, that may be obtrusive to mother-infant bonding. Some have suggested continuous pulse oximetry during this period, but there is no evidence to support this practice and this overmonitoring could lead to unnecessary parental concern. Because many cases of SUPC occur within the 1st few hr of life, the delivery unit should be staffed to permit frequent newborn assessments, while preserving the developing mother-child bond.

Many of the same safety concerns that occur during SSC immediately after birth continue to be a concern during rooming-in, if mother is not given guidance on the safe rooming-in practices. Cosleeping should not be permitted on the postpartum unit. Mothers and families need to be informed of the risks of cosleeping. Staffing ratios should be determined to meet the needs of both mother and infant to allow for frequent assessments, rapid response time to call lights, and time for maternal education.

Bibliography

Bass JL, Gartley T, Kleinman R. Unintended consequences of current breastfeeding initiatives. JAMA Pediatr . 2016;170(10):923–924.

Becher JC, Bushan SS, Lyon AJ. Unexpected collapse in apparent healthy newborns—a prospective national study of a missing cohort of neonatal deaths and near-death events. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2012;97:F30–F34.

Feldman-Winter L, Goldsmith JP, AAP Committee On Fetus And Newborn, AAP Task Force On Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Safe sleep and Skin-to-skin care in the neonatal period for healthy term newborns. Pediatrics . 2016;138(3):e20161889.

Herlenius E, Kuhn P. Sudden unexpected postnatal collapse of newborn infants: a review of cases, definitions, risks, and preventative measures. Transl Stroke Res . 2013;4(2):236–247.

Moore ER, Bergman N, Anderson GC, Medley N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2016;(11); 10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub4 [Art. No.: CD003519].

Nassi N, Piumelli R, Nardini V, et al. Sudden unexpected perinatal collapse and sudden unexpected early neonatal death. Early Hum Dev . 2013;89(Suppl 4):S25–S26.

Pejovic NJ, Herlenius E. Unexpected collapse of healthy newborn infants: risk factors, supervision and hypothermia treatment. Acta Paediatr . 2013;102(7):680–688.

Poets A, Steinfeldt R, Poets CF. Sudden deaths and severe apparent life-threatening events in term infants within 24 hours of birth. Pediatrics . 2011;127(4):e1073–e1076.

Thach BT. Deaths and near deaths of healthy newborn infants while bed sharing on maternity wards. J Perinatol . 2014;34(4):275–279.