Thrombotic Disorders in Children

Leslie J. Raffini, J. Paul Scott

Advancements in the treatment and supportive care of critically ill children, coupled with a heightened awareness of genetic risk factors for thrombosis , have led to an increase in the diagnosis of thromboembolic events (TEs) in children. TEs are seen in pediatric tertiary care centers and may result in significant acute and chronic morbidity. Despite increasing in relative terms, TEs in children are still rare. Diagnosis and treatment are often extrapolated from adult data.

Epidemiology

Studies have confirmed a significant increase in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pediatric tertiary hospitals across the United States. Although the overall incidence of thrombosis in the general pediatric population is quite low (0.07/100,000), the rate of VTE in hospitalized children is 60 per 10,000 admissions. Infants <1 yr old account for the largest proportion of pediatric VTEs, with a 2nd peak during adolescence.

The majority of children who develop a TE have multiple risk factors that may be acquired, inherited, or anatomic (Table 506.1 ). The presence of a central venous catheter (CVC, peripherally inserted central venous catheter) is the most important risk factor for VTE in pediatric patients, associated with approximately 90% of neonatal VTE and 60% of childhood VTE. CVCs are often necessary for the care of premature neonates and children with acute and chronic diseases and are used for intravenous (IV) hyperalimentation, chemotherapy, dialysis, antibiotics, or supportive therapy. CVCs may damage the endothelial lining and/or cause blood flow disruption, increasing the risk of thrombosis. Many other acquired risk factors are associated with thrombosis, including trauma, infection, chronic medical illnesses, and medications. Cancer, congenital heart disease, and prematurity are the most common medical conditions associated with TEs.

Table 506.1

PICC, Peripherally inserted central venous catheter.

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) is a well-described syndrome in adults characterized by recurrent fetal loss and/or thrombosis. Antiphospholipid antibodies are associated with both venous and arterial thrombosis. The mechanism by which these antibodies cause thrombosis is not well understood. A diagnosis of APS requires the presence of both clinical and laboratory abnormalities (see Laboratory Testing ). The laboratory abnormalities must be persistent for 12 wk. Because of the high risk of recurrence, patients with APS often require long-term anticoagulation. It is important to note that healthy children may have a transient lupus anticoagulant, often diagnosed because of a prolonged partial thromboplastin time (PTT) on routine preoperative testing. In this setting, transient antibodies may be associated with a recent viral infection and are not a risk factor for thrombosis. APS is noted in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (see Chapter 183 ) and may also be associated with livedo reticularis, neuropsychiatric complications, thrombocytopenia, or anemia; these patients are often persistently positive for the antiphospholipid antibody. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome is a rare and potentially fatal disorder characterized by rapid onset of multiorgan thrombosis and/or thrombotic microangiopathies.

Anatomic abnormalities that impede blood flow also predispose patients to thrombosis at an earlier age. Atresia of the inferior vena cava has been described in association with acute and chronic lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT ). Compression of the left iliac vein by the overlying right iliac artery (May-Thurner syndrome ) should be considered in patients who present spontaneously with left iliofemoral thrombosis, and thoracic outlet obstruction (Paget-Schroetter syndrome ) frequently presents with effort-related axillary-subclavian vein thrombosis.

Clinical Manifestations

Extremity Deep Vein Thrombosis

Children with acute DVT often present with extremity pain, swelling, and discoloration. A history of a current or recent CVC in that extremity should be very suggestive. Many times, symptoms of CVC-associated thrombosis are more subtle and chronic, including repeated CVC occlusion or sepsis, or prominent venous collaterals on the chest, face, and neck.

Pulmonary Embolism

Symptoms of pulmonary embolism (PE ) include shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, cough, hemoptysis, fever, and, in the case of massive PE, hypotension and right-sided heart failure. Based on autopsy studies in pediatric centers, PE is often undiagnosed, because young children are unable to describe their symptoms accurately and their respiratory deterioration may be masked by other conditions (see Chapter 436.1 ).

Cerebral Sinovenous Thrombosis

Symptoms may be subtle and may develop over many hours or days. Neonates with cerebral sinovenous thrombosis often present with seizures, whereas older children often complain of headache, vomiting, seizures, and focal signs. They may also have papilledema and abducens palsy. Older patients may have a concurrent sinusitis or mastoiditis that has contributed to the thrombosis.

Renal Vein Thrombosis

Renal vein thrombosis is the most common spontaneous VTE in neonates. Affected infants may present with hematuria, an abdominal mass, and thrombocytopenia. Infants of diabetic mothers are at increased risk for renal vein thrombosis, although the mechanism for the increased risk is unknown. Approximately 25% of cases are bilateral.

Peripheral Arterial Thrombosis

With the exception of stroke, the majority of arterial TEs in children are secondary to catheters, often in neonates related to umbilical artery lines or in patients with cardiac defects undergoing cardiac catheterization. Patients with an arterial thrombosis affecting blood flow to an extremity will present with a cold, pale, blue extremity with poor or absent pulses.

Stroke

Ischemic stroke typically presents with hemiparesis, loss of consciousness, or seizures. This condition may occur secondary to pathology that affects the intracranial arteries (e.g., sickle cell disease, vasculopathy, or traumatic arterial dissection) or may result from venous thrombi that embolize to the arterial circulation (placental thrombi, children with congenital heart disease or patent foramen ovale).

Rapidly Progressive Thrombosis (Thrombotic Storm)

Rapid progression or multifocal thrombosis is a rare complication of APS, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with thrombosis, or thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura during appropriate antithrombotic therapy. Multiorgan dysfunctions develop in the presence of small vessel occlusion and elevated D-dimer levels. Recurrences and postthrombotic syndrome (PTS) may occur. Treatment includes aggressive anticoagulation, often with direct thrombin inhibitors or fondaparinux, followed by prolonged warfarin therapy. In rare cases, plasmapheresis or immunosuppression may be warranted.

Diagnosis

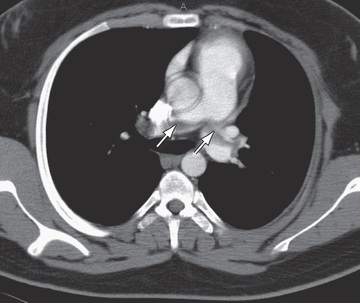

Ultrasound with Doppler flow is the most commonly employed imaging study for the diagnosis of upper-extremity, or more often lower-extremity, VTE. Spiral CT is used most frequently for the diagnosis of PE (Fig. 506.1 ). Other diagnostic imaging options include CT and MR venography, which are noninvasive, although the sensitivity and specificity of these studies is not known. These studies may be particularly helpful in evaluating proximal or abdominal thrombosis. For the diagnosis of cerebral sinovenous thrombosis and acute ischemic stroke, the most sensitive imaging study is brain MRI with venography or diffusion-weighted imaging.

Laboratory Testing

All children with a VTE should have a complete blood count and a baseline prothrombin time (PT) and PTT to assess their coagulation status. In adults with suspected DVT, the D-dimer level has a high negative predictive value, but the predictive value is not as well established for children. The D-dimer is a fragment produced when fibrin is degraded by plasmin and is a measure of fibrinolysis. Based on the clinical scenario, other laboratory studies, such as renal and hepatic function, may be indicated. Testing for APS includes evaluation for the lupus anticoagulant as well as anticardiolipin and anti–β2 -glycoprotein antibodies, and should be considered in patients with inflammatory disorders or those who present with thrombosis and no other obvious risk factors.

There is debate regarding which patients should have testing for inherited risk factors. Thrombophilia testing rarely influences the acute management of a child with a thrombotic event. Identification of an inherited thrombophilia may influence the duration of treatment, particularly for those with a strong thrombophilia, and may aid in counseling patients about their risk of recurrence.

The evaluation and interpretation of coagulation studies in pediatric patients may be complicated by the developing hemostatic system and the differences in normal ranges between infants and adults (see Chapter 505 ).

Treatment

Therapeutic options for children with thrombosis include observation, anticoagulation, thrombolysis, and surgery. In premature neonates and critically ill children who are at high risk of bleeding, the potential benefits must be weighed against the risks, and close observation with repeat imaging may be an option. The majority of non-neonates with symptomatic thrombosis are treated with anticoagulant therapy. The goal of anticoagulation is to reduce the risk of embolism, halt clot extension, and prevent recurrence (see Chapter 506.1 ). Systemic or endovascular thrombolysis may be indicated for organ- or limb-threatening thrombosis. Surgery may be necessary for life- or limb-threatening thrombosis when there is a contraindication to thrombolysis. The optimal treatment for a child with acute ischemic stroke depends on the likely etiology and the size of the infarct. Children with sickle cell disease who develop stroke are treated with chronic red blood cell transfusions to reduce recurrence.

Complications

Complications of VTE include recurrent thrombosis (local or distant), and development of PTS. A thrombosed blood vessel may partially or fully recanalize or may remain occluded. Over time, an occluded deep vein may cause venous hypertension, resulting in blood flow being directed from the deep system into the superficial veins and potentially producing pain, swelling, edema, discoloration, and ulceration. This clinical picture is known as postthrombotic syndrome and may be chronically disabling. Several prospective studies in adults have shown PTS to be present in 17–50% of patients with a history of thrombosis. The likelihood of developing PTS is highest in the 1st 2 yr of life but continues to increase over time.

Anticoagulant and Thrombolytic Therapy

Leslie J. Raffini, J. Paul Scott

Initial options for anticoagulation in children generally include unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), followed by LMWH or warfarin for outpatient management (Table 506.2 ). Several direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) approved for treatment of TE in patients >18 yr old are currently in phase III clinical trials in children. These drugs act by inhibiting factor Xa or thrombin (Table 506.3 ). DOACs are recommended for acute and long term anticoagulant therapy for adults with VTE.

Table 506.2

Comparison of Antithrombotic Agents

| rTPA | UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN | WARFARIN | LMW HEPARIN (ENOXAPARIN) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | Recent onset of life- or limb-threatening thrombus | Acute or chronic thrombus, prophylaxis | Subacute or chronic thrombosis, thromboprophylaxis for cardiac valves | Acute or chronic thrombus, prophylaxis |

| Administration | IV continuous infusion | IV continuous infusion | PO once daily | SC injection twice daily |

| Monitoring | “Lytic state”: FDP or D-dimer | PTT | INR | Anti–factor Xa activity |

| Other | Higher risk of bleeding | Difficult to titrate; requires frequent dose adjustments; higher dose required in newborns | Heavily influenced by drug and diet | More stable and easy to titrate; concern of osteopenia with long-term use |

FDP, Fibrin degradation products; INR, international normalized ratio; IV, intravenous; LMW, low-molecular-weight; PO, oral; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; rTPA, recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator; SC, subcutaneous.

Table 506.3

Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs)

| DABIGATRAN | RIVAROXABAN | APIXABAN | EDOXABAN | BETRIXABAN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor target | IIa | Xa | Xa | Xa | Xa |

| Half-life (hr) | 12-17 | 5-13 | 8-14 | 10-14 | 20-30 |

| Renal clearance (%) | 80 | 33 | 25 | 35-50 | 5-7 |

| Drug metabolism | P-glycoprotein | P-glycoprotein and CYP34A | P-glycoprotein and CYP34A | P-glycoprotein | P-glycoprotein |

| Drug reversal | Idarucizumab | Andexanet-alpha | Andexanet-alpha | Andexanet-alpha | Andexanet-alpha |

The optimal duration of anticoagulation for children with TEs is not well established. Current guidelines recommend that neonates receive 6 wk to 3 mo of therapy for VTE, and that older children receive 3-6 mo of therapy. Patients with strong inherited thrombophilia, recurrent thrombosis, and APS may require indefinite anticoagulation.

Unfractionated Heparin

Both UFH and LMWH act by catalyzing the action of antithrombin III (AT III). UFH consists of large-molecular-weight polysaccharide chains that interact with AT III, catalyzing the inhibition of factor Xa and thrombin, as well as other serine proteases.

Heparin Dosing

Based on adult data, a therapeutic heparin dose achieves a prolongation of the PTT of 1.5-2.5 the upper limit of normal. A bolus dose of 75-100 units/kg results in a therapeutic PTT in the majority of children. This bolus should be followed by a continuous infusion. Initial dosing is based on age, with infants having the highest requirements. It is important to continue to monitor the PTT closely. In some situations, such as patients with a lupus anticoagulant, those with elevated factor VIII, or neonates, the PTT may not accurately reflect the degree of anticoagulation, and heparin can be monitored using a heparin anti-Xa level of 0.35-0.7 units/mL.

Heparin Complications

Maintaining the PTT in the therapeutic range can be difficult in young children for several reasons. The bioavailability of heparin is difficult to predict and may be influenced by plasma proteins. In many patients, this results in multiple dose adjustments requiring close monitoring with frequent venipuncture. UFH also requires continuous IV access, which may be difficult to maintain in young children.

The most common adverse effect related to heparin therapy is bleeding . This is well documented in the adult medical literature, and there are case reports of life-threatening bleeding in children treated with heparin. The true frequency of bleeding in pediatric patients receiving heparin has not been well established and is reported as 1–24%. If the anticoagulant effect of heparin must be reversed immediately, protamine sulfate may be administered to neutralize the heparin.

Other adverse effects include osteoporosis and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) . Although rare in pediatric populations, HIT is a prothrombotic, immune-mediated complication in which antibodies develop to a complex of heparin and platelet factor 4. These antibodies result in platelet activation, stimulation of coagulation, thrombocytopenia, and in some cases, life-threatening thrombosis. If HIT is strongly suspected, heparin must be discontinued immediately. An alternative parenteral anticoagulant, such as argatroban or bivalirudin, may be used in this situation.

Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin

In contrast to UFH, LMWH contains smaller-molecular-weight polysaccharide chains. The interaction of the smaller chains with AT III results primarily in the inhibition of factor Xa, with less of an effect on thrombin. The several LMWHs available have variable inhibitory effects on thrombin. For this reason, the PTT is not a reliable measure of the anticoagulant effect of LMWH, and the anti–factor Xa activity is used instead. Because of the ease of dosing and need for less monitoring, LMWH is the most frequently used anticoagulant in pediatric patients. The LMWH formulation that has been used most often in pediatric patients is enoxaparin.

Enoxaparin Dosing

The recommended standard starting dose of enoxaparin for infants <2 mo old is 1.5 mg/kg/dose subcutaneously every 12 hr and for patients >2 mo old, 1 mg/kg every 12 hr, although many centers use slightly higher doses for children <2 yr old. In general, peak levels are achieved 3-6 hr after injection. A therapeutic anti–factor Xa level, drawn 4 hr after the 2nd or 3rd dose, should be 0.5-1.0 IU/mL; the dose can be titrated to achieve this range. The elimination half-life of enoxaparin is 4-6 hr. Enoxaparin is cleared by the kidney and should be used with caution in patients with renal insufficiency. It should be avoided in patients with renal failure.

After an initial period of anticoagulation with heparin or LMWH, patients may continue to receive LMWH as an outpatient for the duration of therapy or may be transitioned to an oral anticoagulant such as warfarin.

Warfarin

Warfarin is an oral anticoagulant that competitively interferes with vitamin K metabolism, exerting its action by decreasing concentrations of the vitamin K–dependent coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X, as well as protein C and protein S. Therapy should be started while a patient is anticoagulated with heparin or LMWH because of the risk of warfarin-induced skin necrosis. This transient hypercoagulable condition may occur when levels of protein C drop more rapidly than the procoagulant factors.

Dosing

Warfarin therapy is often initiated with a loading dose, with subsequent dose adjustments made according to a nomogram. When initiating warfarin therapy, UFH or LMWH should be continued until the international normalized ratio (INR) is therapeutic for 2 days. In most patients, this takes 5-7 days. The PT is used to monitor the anticoagulant effect of warfarin. Because the thromboplastin reagents used in PT assays have widely varying sensitivities, the PT performed in one laboratory cannot be compared to that performed in another laboratory. As a result, the INR was developed as a mechanism to standardize the variation in the thromboplastin reagent. The target INR range depends on the clinical situation. In general, a range of 2.0-3.0 is the target for the treatment of VTE. High-risk patients, such as those with mechanical heart valves, APS, or recurrent thrombosis, may require a higher target range.

Polymorphisms in CYP2C9 and VKORC1 affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin. Pharmacogenetic testing can identify wild-type responders, as well as those who are sensitive (increased risk of bleeding) and highly sensitive. Genotyping in adults may help select warfarin dose, monitor for bleeding, or choose a DOAC instead of warfarin for patients highly sensitive and at risk for hemorrhage.

Complications

As with the other anticoagulants, bleeding is the most common adverse effect. The risk of serious bleeding in children receiving warfarin for the treatment of VTE has been reported at 0.5% per year. Children who have supratherapeutic INR are at higher risk. There is considerable interpatient variation in dose. Diet, medications, and illness may influence the metabolism of warfarin, requiring frequent dose adjustments and laboratory studies. Numerous medications can affect the pharmacokinetics of warfarin by altering its clearance or rate of absorption. These effects can have a profound impact on the INR and must be considered when monitoring a patient receiving warfarin.

The strategies used to reverse warfarin therapy depend on the clinical situation and whether or not there is bleeding. Vitamin K can be administered to reverse the effect of warfarin but takes some time to have effect. If the patient is having significant bleeding, fresh-frozen plasma (FFP, 15 mL/kg) should be given along with the vitamin K. A nonactivated plasma-derived 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate is approved for use in adults on vitamin K antagonists who have major bleeding.

Nonhemorrhagic complications are uncommon in children. Warfarin is a teratogen, particularly in the first trimester. Warfarin embryopathy is characterized by bone and cartilage abnormalities known as chondrodysplasia punctata. Affected infants may have nasal hypoplasia and excessive calcifications in the epiphyses and vertebrae.

Direct Oral Anticoagulants

Oral direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) or inhibitors of factor Xa (apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban) are approved agents for the prevention or treatment of thrombosis in patients >18 yr old (see Table 506.3 ). Fixed dosing, oral administration, no dietary interference with vitamin K, and no need to monitor laboratory tests, as well as initial results suggesting noninferiority to warfarin and fewer bleeding episodes, have favored the use of DOACs. Drugs are available to reverse the effects of DOACs if indicated. There is a paucity of evidence of their utility in children, although there are several ongoing clinical trials.

Thrombolytic Therapy

Although anticoagulation alone is often effective at managing thrombosis, more rapid clot resolution may be necessary or desirable. In these situations, a thrombolytic agent that can activate the fibrinolytic system is of potential benefit. The pharmacologic activity of thrombolytic agents depends on the conversion of endogenous plasminogen to plasmin. Plasmin is then able to degrade several plasma proteins, including fibrin and fibrinogen. Because of the high risk of bleeding, thrombolytic therapy is generally reserved for patients with life- or limb-threatening thrombosis.

Tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) is available as a recombinant product and has become the primary agent used for thrombolysis in children, although proper dose finding studies have not been performed.

Dosing

An extremely wide range of doses of TPA has been used for systemic therapy, and no consensus exists as to the optimal dose. Systemic TPA doses of 0.1-0.6 mg/kg/hr were previously recommended, although recent reports indicate successful therapy with fewer bleeding complications using prolonged infusions with very low doses—0.01-0.06 mg/kg/hr.

Monitoring

There is no specific laboratory test to document a “therapeutic range” for thrombolytic therapy. It is important to maintain the fibrinogen >100 mg/dL and the platelet count >75,000 × 109 /L during treatment. Supplementation of plasminogen using FFP is generally recommended in neonates before initiating thrombolysis because of their low baseline levels.

The clinical and radiologic response to thrombolysis should be closely monitored. The duration of therapy depends on the clinical response. Invasive procedures, including urinary catheterization, arterial puncture, and rectal temperatures, should be avoided.

The role of adjuvant UFH during thrombolytic therapy is controversial. Animal models have demonstrated that thrombolytic therapy can induce a procoagulant state with activation of the coagulation system, generation of thrombin, and extension or reocclusion of the thrombosis. In pediatric patients thought to be at low risk for bleeding, adjuvant UFH should be considered using doses of 10-20 units/kg/hr.

Complications

The most serious complication from thrombolysis is bleeding, which has been reported in 0–40% of patients. Absolute contraindications to thrombolysis include major surgery within 7 days, history of significant bleeding (intracranial, pulmonary, or gastrointestinal), peripartum asphyxia with brain damage, uncontrolled hypertension, and severe thrombocytopenia. In the event of serious bleeding, thrombolysis should be stopped and cryoprecipitate given to replace fibrinogen.

Thromboprophylaxis

There have been no formal trials of VTE prevention in children. Hospitalized adolescents with multiple risk factors for thrombosis who are immobilized for a prolonged period may benefit from prophylactic treatment with enoxaparin, 0.5 mg/kg every 12 hr (maximum 30 mg).

Antiplatelet Therapy

Inhibition of platelet function using agents such as aspirin is more likely to be protective against arterial TEs than VTEs. Aspirin , or acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), exerts its antiplatelet effect by irreversibly inhibiting cyclooxygenase, preventing platelet thromboxane A2 production. Aspirin is used routinely in children with Kawasaki disease and may also be useful in children with stroke, ventricular assist devices, and single-ventricle cardiac defects. The recommended dose of aspirin to achieve an antiplatelet effect in children is 1-5 mg/kg/day.

Bibliography

Aguiar CL, Soybilgic A, Avcin T, Myones BL. Pediatric antiphospholipid syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep . 2015;17:27.

Alberts MJ. Genetic of warfarin dosing: one polymorphism at a time. Lancet . 2013;382:749–751.

Ansah DA, Patel KN, Montegna L, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator use in children: bleeding complications and thrombus resolution. J Pediatr . 2016;171:67–72.

Baskin JL, Pui CH, Reiss U, et al. Management of occlusion and thrombosis associated with long-term indwelling central venous catheters. Lancet . 2009;374:159–169.

Brandão LR, Williams S, Kahr WHA, et al. Exercise-induced deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity. Acta Haematol . 2006;115:221–229.

Büller HR, ten Cate-Hoek AJ, Hoes AW, et al. Safely ruling out deep venous thrombosis in primary care. Ann Intern Med . 2009;150:229–235.

Castellucci LA, Cameron C, Le Gal G, et al. Clinical and safety outcomes associated with treatment of acute venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA . 2014;312:1122–1134.

Chang K, Graf E, Davis K, et al. Spectrum of thoracic outlet syndrome presentation in adolescents. Arch Surg . 2011;146:1383–1387.

Chopra V, Anand S, Hickner A, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet . 2013;382:311–324.

Cohen AT, Harrington RA, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Extended thromboprophylaxis with betrixaban in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med . 2016;375(6):534–544.

Di Nisio M, van Es N, Büller HR. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Lancet . 2016;388:3060–3069.

Eikelboom JW, Weitz JI. Selective factor xa inhibition for thromboprophylaxis. Lancet . 2008;372:6–8.

Eikelboom JW, Weitz JI. Idrabiotaparinux treatment for venous thromboembolism. Lancet . 2012;379:96–98.

Enden T, Haig Y, Klow NE, et al. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVent study): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet . 2012;379:31–38.

Fischer HD, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, et al. Hemorrhage during warfarin therapy associated with cotrimoxazole and other urinary tract anti-infective agents. Arch Intern Med . 2010;170:617–621.

Gaballah M, Shi J, Kukreja K, et al. Endovascular thrombolysis in the management of iliofemoral thrombosis in children: a multi-institutional experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol . 2016;27:524–530.

Gage BF, Bass AR, Lin H, et al. Effect of genotype-guided warfarin dosing on clinical events and anticoagulation control among patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty. JAMA . 2017;318:1115–1124.

Giannakopoulos B, Krilis SA. The pathogenesis of the antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med . 2013;368:1033–1042.

Giordano P, Tesse R, Lassandro G, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of children positive for antiphospholipid antibodies. Blood Transfus . 2012;10:296–301.

Goldenberg NA. Long-term outcomes of venous thrombosis in children. Curr Opin Hematol . 2005;12:370–376.

Goldenberg NA, Durham JD, Knapp-Clevenger R, et al. A thrombolytic regimen for high-risk deep venous thrombosis may substantially reduce the risk of postthrombotic syndrome in children. Blood . 2007;110:45–53.

Goldenberg NA, Pounder E, Knapp-Clevenger R, et al. Validation of upper extremity post-thrombotic syndrome outcome measurement in children. J Pediatr . 2010;157:852–855.

Gupta A, Johnson DH, Nagalla S. Antiphospholipid antibodies. JAMA . 2017;318:959–960.

The Hokusai-VTE Investigators. Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med . 2013;369:1406–1414.

Hunt BJ. Pediatric antiphospholipid antibodies and antiphospholipid syndrome. Semin Thromb Hemost . 2008;34:274–281.

Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest . 2016;149:315–352.

Kuhle S, Eulmesekian P, Massicotte P, et al. A clinically significant incidence of bleeding in critically ill children receiving therapeutic doses of unfractionated heparin: a prospective cohort study. Haematologica . 2007;92:244–247.

Kyrle PA. Vitamin K antagonists: self-determination by self-monitoring? Lancet . 2012;379:292–293.

Landenfeld CS. Noninvasive diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. JAMA . 2008;300:1696–1697.

Le Gal G, Kercret G, Yahmed KB, et al. Diagnostic value of single compete compression ultrasonography in pregnant and postpartum women with suspected deep vein thrombosis: prospective study. BMJ . 2012;344:16.

Lee A, Crowther M. Practical issues with vitamin K antagonists: elevated INRs, low time-in-therapeutic range, and warfarin failure. J Thromb Thrombolysis . 2011;31:249–258.

Lyle CA, Sidonio RF, Goldenberg NA. New developments in pediatric venous thromboembolism and anticoagulation, including the target-specific oral anticoagulants. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2015;27:18–25.

Manco-Johnson MJ. How I treat venous thrombosis in children. Blood . 2007;107:21–29.

Manco-Johnson MJ, Wang M, Goldenberg NA, et al. Treatment, survival, and thromboembolic outcomes of thrombotic storm in children. J Pediatr . 2012;161:682–688.

The Medical Letter. Antithrombotic drugs. Med Lett . 2014;56:103–108.

The Medical Letter. Dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa)—a new oral anticoagulant. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2010;52(1351):89–90.

The Medical Letter. Prothrombin complex concentrates to reverse warfarin-related bleeding. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2011;53:78–80.

The Medical Letter. Rethinking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2013;55:77–78.

The Medical Letter. Apixaban (Eliquis)—a new oral anticoagulant for atrial fibrillation. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2013;55:9–10.

The Medical Letter. Kcentra: a 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate for reversal of warfarin anticoagulation. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2013;55:53.

The Medical Letter. Edoxaban (Savaysa): the fourth new oral anticoagulant. Med Lett . 2015;57:43–46.

Miyawaki Y, Suzuki A, Fujita J, et al. Thrombosis from a prothrombin mutation conveying antithrombin resistance. N Engl J Med . 2012;366:2390–2396.

Monagle P, Chan A, Goldenberg N, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: American college of chest physicians Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest . 2012;141:e737S–801S.

Pollack CV Jr, Reilly PA, van Ryn J, et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal: full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med . 2017;377:431–441.

Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, et al. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children's hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics . 2009;124:1001–1008.

Richard AA, Kim S, Moffett BS, et al. Comparison of anti-xa levels in obese and non-obese pediatric patients receiving treatment doses of enoxaparin. J Pediatr . 2013;162:293–296.

Riley TR, Gauthier-Lewis ML, Sanchez CK, Douglas JS. Role of agents for reversing the effects of target-specific oral anticoagulants. Am J Health Syst Pharm . 2017;74:54–61.

Rondina MT, Pendleton RC, Wheeler M, et al. The treatment of venous thromboembolism in special populations. Thromb Res . 2007;119:391–402.

Roy PM. Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. BMJ . 2009;339:412–413.

Ruiz-Irastorza G, Crowther M, Branch W, et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Lancet . 2010;376:1498–1506.

Saracco P, Bagna R, Gentilomo C, et al. Clinical data of neonatal systemic thrombosis. J Pediatr . 2016;171:60–66.

Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AJ, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med . 2009;361:2342–2352.

Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med . 2013;368:709–718.

Siegel DM, Curnutte JT, Connolly SJ, et al. Andexanet alfa for the reversal of factor xa inhibitor activity. N Engl J Med . 2015;373:2413–2424.

Stegeman BH, de Bastos M, Rosendaal FR, et al. Different combined oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ . 2013;347:11.

Tremor CC III, Chung RJ, Michelson AD, et al. Hormonal contraception and thrombotic risk: a multidisciplinary approach. Pediatrics . 2011;127:347–357.

Tuckuviene R, Christensen AL, Helgestad J, et al. Pediatric venous and arterial noncerebral thromboembolism in Denmark: a nationwide population-based study. J Pediatr . 2011;159:663–669.

Van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood . 2014;124:1968–1975.

Verheugt FWA, Granger CB. Oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: current status, special situations, and unmet needs. Lancet . 2015;386:303–310.

Wells PS, Forgie MA, Rodger MA. Treatment of venous thromboembolism. JAMA . 2014;311:717–726.

Young G, Albisetti M, Bonduel M, et al. Impact of inherited thrombophilia on venous thromboembolism in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Circulation . 2008;118:1373–1382.