Pulmonary Embolism, Infarction, and Hemorrhage

Pulmonary Embolus and Infarction

Mary A. Nevin

Venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) has become an increasingly recognized critical problem in children and adolescents with chronic disease, as well as in patients without identifiable risk factors (Table 436.1 ). Improvements in survival with chronic illness have likely contributed to the larger number of children presenting with these thromboembolic events; they are a significant source of morbidity and mortality and may only be recognized on postmortem examination. A high level of clinical suspicion and appropriate identification of at-risk individuals is therefore recommended.

Table 436.1

Risk Factors for Pulmonary Embolism

| ENVIRONMENTAL |

| WOMEN'S HEALTH |

| MEDICAL ILLNESS |

| SURGICAL |

| THROMBOPHILIA |

| NONTHROMBOTIC |

Modified from Goldhaber SZ: Pulmonary embolism, Lancet 363:1295–1305, 2004.

Etiology

A number of risk factors may be identified in children and adolescents; the presence of immobility, malignancy, pregnancy, infection, indwelling central venous catheters, and a number of inherited and acquired thrombophilic conditions have all been identified as placing an individual at risk. In children, a significantly greater percentage of VTEs are risk associated as compared with their adult counterparts. Children with deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) are much more likely to have one or more identifiable conditions or circumstances placing them at risk. In contrast to adults, idiopathic thrombosis is a rare occurrence in the pediatric population. In a retrospective cohort of patients with VTE in U.S. children's hospitals from 2001 to 2007, the majority (63%) of affected children were found to have one or more chronic medical comorbidities. In a large Canadian registry, 96% of pediatric patients were found to have one risk factor and 90% had two or more risk factors. In contrast, approximately 60% of adults with this disorder have an identifiable risk factor (see Table 436.1 ). The most common identified risk factors in children include infection, congenital heart disease, and the presence of an indwelling central venous catheter.

Embolic disease in children is varied in its origin. An embolus can contain thrombus, air, amniotic fluid, septic material, or metastatic neoplastic tissue. Thromboemboli are the type most commonly encountered. A commonly encountered risk factor for DVT and PE in the pediatric population is the presence of a central venous catheter. More than 50% of DVTs in children and more than 80% in newborns are found in patients with indwelling central venous lines. The presence of a catheter in a vessel lumen, as well as instilled medications, can induce endothelial damage and favor thrombus formation.

Children with malignancies are also at considerable risk. Although PE has been described in children with leukemia, the risk of PE is more significant in children with solid rather than hematologic malignancies. A child with malignancy may have numerous risk factors related to the primary disease process and the therapeutic interventions. Infection from chronic immunosuppression may interact with hypercoagulability of malignancy and chemotherapeutic effects on the endothelium. In a retrospective cohort of patients with VTE from 2001 to 2007, pediatric malignancy was the medical condition most strongly associated with recurrent VTE.

In the neonatal period, thromboembolic disease and PE may be related to indwelling catheters used for parenteral nutrition and medication delivery. Pulmonary thromboemboli in neonates generally occurs as a complication of underlying disease; the most common associated diagnosis is congenital heart disease, but sepsis and birth asphyxia are also notable associated conditions. Other risk factors include a relative immaturity of newborn infants’ coagulation; plasma concentrations of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors (II, VII, IX, X); factors XII, XI, and prekallikrein and high molecular weight kininogen are only approximately half of adult levels (see Chapter 502 ). PE in neonates may occasionally reflect maternal risk factors, such as diabetes and toxemia of pregnancy. Infants with congenitally acquired homozygous deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C, and protein S are also more likely to present with thromboembolic disease in the neonatal period (see Chapter 505 ).

Pulmonary air embolism is a defined entity in the newborn or young infant and is attributed to the conventional ventilation of critically ill (and generally premature) infants with severe pulmonary disease. In the majority of instances, the pulmonary air embolism is preceded by an air-leak syndrome. Infants may become symptomatic and critically compromised by as little as 0.4 mL/kg of intravascular air; these physiologic derangements are thought to be secondary to the effects of nitrogen.

Prothrombotic disease can also manifest in older infants and children. Disease can be congenital or acquired. Inherited thrombophilic conditions include deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C, and protein S, as well as mutations of factor V Leiden (G1691A) (see Chapter 505 ) and prothrombin (factor II 20210A mutation) (see Chapter 505 ), and elevated values of lipoprotein A. In addition, multiple acquired thrombophilic conditions exist; these include the presence of lupus anticoagulant (may be present without the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus), anticardiolipin antibody, and anti–β2 -glycoprotein 1 antibody. Finally, conditions such as hyperhomocysteinemia (see Chapter 104 ) may have both inheritable and dietary determinants. All have all been linked to thromboembolic disease. DVT/PE may be the initial presentation.

Children with sickle cell disease are also at high risk for pulmonary embolus and infarction. Acquired prothrombotic disease is seen in conditions such as nephrotic syndrome (see Chapter 545 ) and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. From one-quarter to one-half of children with systemic lupus erythematosus (see Chapter 183 ) have thromboembolic disease. There is a significant association with VTE onset in children for each inherited thrombophilic trait evaluated, thereby illuminating the importance of screening for thrombophilic conditions for those at risk for VTE. Septic emboli are rare in children but may be caused by osteomyelitis, jugular vein or umbilical thrombophlebitis, cellulitis, urinary tract infection, and right-sided endocarditis.

Other risk factors include infection, cardiac disease, recent surgery, and trauma. Surgical risk is thought to be more significant when immobility will be a prominent feature of the recovery. Use of oral contraceptives confers additional risk, although the level of risk in patients taking these medications appears to be decreasing, perhaps because of the lower amounts of estrogen in current formulations. In a previously healthy adolescent patient, the risk factors are often unknown or are similar to adults (see Tables 436.1 and 436.2 ).

Table 436.2

Clinical Decision Rules for Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

| WELLS' SCORE FOR DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS * | ||

| Active cancer | +1 | NA |

| Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster cast on lower extremities | +1 | NA |

| Recent immobilization >3 days or major surgery within the past 4 wk | +1 | NA |

| Localized tenderness of deep venous system | +1 | NA |

| Swelling of entire leg | +1 | NA |

| Calf swelling >3 cm compared to asymptomatic side | +1 | NA |

| Unilateral pitting edema | +1 | NA |

| Collateral superficial veins | +1 | NA |

| Previously documented deep vein thrombosis | +1 | NA |

| Alternative diagnosis at least as likely as deep vein thrombosis | −2 | NA |

| WELLS' SCORE FOR PULMONARY EMBOLISM † , ‡ | ||

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than pulmonary embolism | +3 | +1 |

| Clinical signs and symptoms of deep vein thrombosis | +3 | +1 |

| Heart rate >100 beats/min | +1⋅5 | +1 |

| Previous deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism | +1⋅5 | +1 |

| Immobilization or surgery within the past 4 wk | +1⋅5 | +1 |

| Active cancer | +1 | +1 |

| Hemoptysis | +1 | +1 |

| REVISED GENEVA SCORE FOR PULMONARY EMBOLISM § , || | ||

| Heart rate ≥95 beats/min | +5 | +2 |

| Heart rate 75–94 beats/min | +3 | +1 |

| Pain on lower-limb deep venous palpation and unilateral edema | +4 | +1 |

| Unilateral lower-limb pain | +3 | +1 |

| Previous deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism | +3 | +1 |

| Active cancer | +2 | +1 |

| Hemoptysis | +2 | +1 |

| Surgery or fracture within the past 4 wk | +2 | +1 |

| Age >65 yr | +1 | +1 |

* Classification for original Wells' score for deep vein thrombosis: deep vein thrombosis unlikely if score ≤2; deep vein thrombosis likely if score >2.

† Classification for original Wells' score for pulmonary embolism: pulmonary embolism unlikely if score ≤4; pulmonary embolism likely if score >4.

‡ Classification for simplified Wells' score for pulmonary embolism: pulmonary embolism unlikely if score ≤1; pulmonary embolism likely if score >1.

§ Classification for original revised Geneva score for pulmonary embolism: non-high probability of pulmonary embolism if score ≤10; high probability of pulmonary embolism if score >10.

|| Classification for simplified revised Geneva score for pulmonary embolism: non-high probability of pulmonary embolism if score ≤4; high probability of pulmonary embolism if score >4.

From Di Nisio M, van Es N, Büller HR: Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, Lancet 388:3060–3069, 2016 (Table 1, p. 3062).

Epidemiology

A retrospective cohort study was performed with patients younger than 18 yr of age, discharged from 35 to 40 children's hospitals across the United States from 2001 to 2007. During this time, a dramatic increase was noted in the incidence of VTE; the annual rate of VTE increased by 70% from 34 to 58 cases per 10,000 hospital admissions. Although this increased incidence was noted in all age groups, a bimodal distribution of patient ages was found, consistent with prior studies; infants younger than 1 yr of age and adolescents made up the majority of admissions with VTE, but neonates continue to be at greatest risk. The peak incidence for VTE in childhood appears to occur in the 1st mo of life. It is in this neonatal period that thromboembolic events are more problematic, likely as a result of an imbalance between procoagulant factors and fibrinolysis. The yearly incidence of venous events was estimated at 5.3/10,000 hospital admissions in children and 24/10,000 in the neonatal intensive care.

Pediatric autopsy reviews have estimated the incidence of thromboembolic disease in children as between 1% and 4%, although not all were clinically significant. Thromboembolic pulmonary disease is often unrecognized, and antemortem studies may underestimate the true incidence. Pediatric deaths from isolated pulmonary emboli are rare. Most thromboemboli are related to central venous catheters. The source of the emboli may be lower or upper extremity veins as well as the pelvis and right heart. In adults, the most common location for DVT is the lower leg. However, one of the largest pediatric VTE/PE registries found two-thirds of DVTs occurring in the upper extremity.

Pathophysiology

Favorable conditions for thrombus formation include injury to the vessel endothelium, hemostasis, and hypercoagulability. In the case of PE, a thrombus is dislodged from a vein, travels through the right atrium, and lodges within the pulmonary arteries. In children, emboli that obstruct <50% of the pulmonary circulation are generally clinically silent unless there is significant coexistent cardiopulmonary disease. In severe disease, right ventricular afterload is increased with resultant right ventricular dilation and increases in right ventricular and pulmonary arterial pressures. In severe cases, a reduction of cardiac output and hypotension may result from concomitant decreases in left ventricular filling. In rare instances of death from massive pulmonary embolus, marked increases in pulmonary vascular resistance and heart failure are usually present.

Arterial hypoxemia results from unequal ventilation and perfusion; the occlusion of the involved vessel prevents perfusion of distal alveolar units, thereby creating an increase in dead space and hypoxia with an elevated alveolar–arterial oxygen tension difference (see Chapter 400 ). Most patients are hypocarbic secondary to hyperventilation, which often persists even when oxygenation is optimized. Abnormalities of oxygenation and ventilation are likely to be less significant in the pediatric population, possibly owing to less underlying cardiopulmonary disease and greater reserve. The vascular supply to lung tissue is abundant, and pulmonary infarction is unusual with pulmonary embolus but may result from distal arterial occlusion and alveolar hemorrhage.

Clinical Manifestations

Presentation is variable, and many pulmonary emboli are silent. Rarely, a massive PE may manifest as cardiopulmonary failure. Children are more likely to have underlying disease processes or risk factors but might still present asymptomatically with small emboli. Common symptoms and signs of PE caused by larger emboli include hypoxia (cyanosis), dyspnea, tachycardia, cough, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis. Pleuritic chest pain is the most common presenting symptom in adolescents (84%), whereas unexplained and persistent tachypnea may suggest PE in all pediatric patients. Localized crackles may occasionally be appreciated on examination. A high level of clinical suspicion is required because a variety of diagnoses may cause similar symptoms; nonspecific complaints may frequently be attributed to an underlying disease process or an unrelated/incorrect diagnosis. Confirmatory testing should follow a clinical suspicion for PE. In older adolescents and adults, clinical prediction rules have been published and are based on risk factors, clinical signs, and symptoms (see Table 436.2 ). No such clinical prediction rules have been validated in the pediatric population.

Laboratory Findings and Diagnosis

The electrocardiogram, arterial blood gas, and chest radiograph may be used to rule out contributing or comorbid disease but are not sensitive or specific in the diagnosis of PE. Electrocardiographs may reveal ST-segment changes or evidence of pulmonary hypertension with right ventricular failure (cor pulmonale); such changes are nonspecific and nondiagnostic. Radiographic images of the chest are often normal in a child with PE and any abnormalities are likely to be nonspecific. Patients with septic emboli may have multiple areas of nodularity and cavitation, which are typically located peripherally in both lung fields. Many patients with PE have hypoxemia. The alveolar–arterial oxygen tension difference gradient is more sensitive in detecting gas exchange derangements.

A review of results of a complete blood count, urinalysis, and coagulation profile is warranted. Prothrombotic diseases should be highly suspected on the basis of past medical or family history; additional laboratory evaluations include fibrinogen assays, protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III studies, and analysis for factor V Leiden mutation, as well as evaluation for lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies.

Echocardiograms may be warranted to assess ventricular size and function. An echocardiogram is required if there is any suspicion of intracardiac thrombi or endocarditis.

Noninvasive venous ultrasound testing with Doppler flow can be used to confirm DVT in the lower extremities; ultrasonography may not detect thrombi in the upper extremities or pelvis (Fig. 436.1A ). In patients with significant venous thrombosis, D dimers are usually elevated. It is a sensitive but nonspecific test for venous thrombosis. The D dimer may not be clinically relevant in the children with PE as this group is more likely to have an underlying comorbid condition that is also associated with an increased level of D dimers. When a high level of suspicion exists, confirmatory testing with venography should be pursued. DVT can be recurrent and multifocal and may lead to repeated episodes of PE.

Although much more commonly encountered in the adult population, thrombus migration to the pulmonary circulation in children and adolescents may be prevented through surgical placement of an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter. This may be considered when DVT is detected and risk of pulmonary thrombus is high or when there is a medical contraindication to or intolerance for anticoagulant therapy. IVC filter may also be considered prophylactically in the setting of trauma.

Although a ventilation–perfusion (V̇ − Q̇) radionuclide scan is a noninvasive and potentially sensitive method of pulmonary embolus detection, the interpretation of V̇ − Q̇ scans can be problematic. Helical or spiral CT with an intravenous contrast agent is valuable and the diagnostic test of choice to detect a PE (see Fig. 436.1B ). CT studies detect emboli in lobar and segmental vessels with acceptable sensitivities. Poorer sensitivities may be encountered in the evaluation of the subsegmental pulmonary vasculature. Pulmonary angiography is the gold standard for diagnosis of PE, but with availability of multidetector spiral CT angiography, it is not necessary except in unusual cases.

MRI may be emerging as a diagnostic option for patients with VTE. The accuracy of this method is similar to that of multidetector CT. It may be preferable in patients with allergic reactions to contrast material and in pediatric patients in whom the risk of early exposure to ionizing radiation has been established.

Treatment

Initial treatment should always be directed toward stabilization of the patient. Careful approaches to ventilation, fluid resuscitation, and inotropic support are always indicated, because improvement in one area of decompensation can often exacerbate coexisting pathology.

After the patient with a PE has been stabilized, the next therapeutic step is anticoagulation. Evaluations for prothrombotic disease must precede anticoagulation. Acute-phase anticoagulation therapy may be provided with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). Heparins act by enhancing the activity of antithrombin. LMWH is generally preferred in children; this drug can be administered subcutaneously and the need for serum monitoring is decreased. The risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is also decreased with LMWH as compared to UFH. Alternatively, UFH is preferred with patients who have an elevated risk of bleeding as UFH has a shorter half-life than LMWH. UFH is also used preferentially in patients with compromised renal function. In monitoring of drug levels, laboratories must be aware of the drug chosen in order to use the appropriate assay. For UFH, the therapeutic range is 0.3-0.7 anti-Xa activity units/mL. In LMWH, the therapeutic range is 0.5-1.0 units/mL. When the anti-Xa assay is not available, the activated partial thromboplastin time may be used with a goal of 60-85 sec or approximately 1.5-2 times the upper limit of age appropriate normal values. The recommended duration of heparinization during acute treatment is 5-10 days; this length of therapy has been extrapolated from adult data. Long-term therapy with heparin should be avoided whenever possible. Side effects include the aforementioned heparin-induced thrombocytopenia as well as bleeding and osteoporosis.

Extension of anticoagulation therapy occurs in the subacute phase and may utilize LMWH or warfarin. Warfarin is generally initiated after establishing effective anticoagulation with heparin because severe congenital deficiencies of protein C may be associated with warfarin skin necrosis. When the international normalized ratio (INR) is measured between 1.0 and 1.3, the starting dose for warfarin in children is recommended as 0.2-0.3 mg/kg administered orally once daily. Titration of dosing may be needed to achieve a therapeutic INR of 2 to 3. Dosing requirements may vary and clinical pharmacologic correlation is required. The INR is generally monitored 5 days after initiating therapy or a similar period after dose changes and weekly thereafter until stable. The INR should be obtained with any evidence of abnormal bleeding and should be discontinued at least 5 days prior to invasive procedures. The utilization of an anticoagulation team and/or established treatment algorithms is recommended in order to optimize patient safety. With a first occurrence of VTE, anticoagulation is recommended for 3-6 mo in the setting of an identifiable, reversible, and resolved risk factor (e.g., postoperative state). Longer treatment is indicated in patients with idiopathic VTE (6-12 mo) and in those with chronic clinical risk factors (12 mo-lifelong). In the setting of a congenital thrombophilic condition, the duration of therapy is often indefinite. Inhibitors of factor Xa (rivaroxaban, etc.) may become an alternate therapy for both acute PE and long-term treatment (Table 436.3 ).

Table 436.3

Anticoagulant Therapies for Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

| ROUTE OF ADMINISTRATION | RENAL CLEARANCE (%) | HALF-LIFE | INITIAL TREATMENT DOSING | MAINTENANCE TREATMENT DOSING | EXTENDED TREATMENT DOSING | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfractionated heparin (UFH) | Intravenous | ∼30 | ∼1.5 hr | Maintain aPTT 1.5-times upper limit of normal | ||

| Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) | Subcutaneous | ∼80 | 3-4 hr | Weight-based dosing | Weight-based dosing* | |

| Fondaparinux | Subcutaneous | 100 | 17-21 hr | Weight-based dosing | Weight-based dosing | |

| Vitamin K antagonists | Oral | Negligible | Acenocoumarol 8-11 hr; warfarin 36 hr; phenprocoumon 160 hr | Target at INR at 2.0-3.0 and give parallel heparin treatment for at least 5 days | Maintain INR at 2.0-3.0 | Maintain INR at 2.0-3.0 |

| Dabigatran | Oral | ∼80 † | 14-17 hr | Requires at least 5 days heparin lead-in | 150 mg twice a day | 150 mg twice a day |

| Rivaroxaban | Oral | ∼33 ‡ | 7-11 hr | 15 mg twice a day for 3 wk | 20 mg once a day | 20 mg once a day |

| Apixaban | Oral | ∼25 ‡ | 8-12 hr | 10 mg twice a day for 1 wk | 5 mg twice a day | 2.5 mg twice a day |

| Edoxaban | Oral | ∼35 ‡ | 6-11 hr | Requires at least 5 days heparin lead-in | 60 mg once a day § | 60 mg once a day § |

| Aspirin | Oral | ∼10 | 15 min | 80–100 mg once a day |

* Treatment with low molecular weight heparin is recommended for patients with active cancer and pregnant women.

† Dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with a creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min.

‡ Apixaban, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban are contraindicated in patients with a creatinine clearance below 15 mL/min.

§ The recommended edoxaban dose is 30 mg once a day for patients with a creatinine clearance of 30–50 mL/min, a bodyweight less than or equal to 60 kg, or for those on certain strong P-glycoprotein inhibitors.

Medication dosing may vary with regard to primary diagnosis, age, comorbidities, and other factors. Clinical-pharmacologic correlation is advocated.

aPTT , activated partial thromboplastin time; INR , international normalized ratio.

From Di Nisio M, van Es N, Büller HR: Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, Lancet 388:3060–3069, 2016 (Table 2, p. 3065).

Thrombolytic agents such as recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, may be utilized in combination with anticoagulants in the early stages of treatment; their use is most likely to be considered in children with hemodynamically significant PE (echocardiogram evidence of right ventricular dysfunction) or other severe potential clinical sequelae of VTE. Combined therapy may reduce the incidences of progressive thromboembolism, pulmonary embolus, and postthrombotic syndrome. Mortality rate appears to be unaffected by additional therapies; nonetheless, the additional theoretic risk of hemorrhage limits the use of combination therapy in all but the most compromised patients. The use of thrombolytic agents in patients with active bleeding, recent cerebrovascular accidents, or trauma is contraindicated.

Surgical embolectomy is invasive and is associated with significant mortality. Its application should be limited to those with large emboli that result in persistent hemodynamic compromise refractory to standard therapy.

Prognosis

Mortality in pediatric patients with PE is likely to be attributable to an underlying disease process rather than to the embolus itself. Short-term complications include major hemorrhage (either due to the thrombosis or secondary to anticoagulation). Conditions associated with a poorer prognosis include malignancy, infection, and cardiac disease. The mortality rate in children from PE is 2.2%. Recurrent thromboembolic disease may complicate recovery. The practitioner must conduct an extensive evaluation for underlying pathology so as to prevent progressive disease. Postthrombotic syndrome is another recognized complication of pediatric thrombotic disease. Venous valvular damage can be initiated by the presence of DVT, leading to persistent venous hypertension with ambulation and valvular reflux. Symptoms include edema, pain, increases in pigmentation, and ulcerations. Affected pediatric patients may suffer lifelong disability.

Bibliography

Agha BS, Sturm JJ, Simon HK, et al. Pulmonary embolism in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics . 2013;132:663–667.

Askegard-Giesmann JR, Caniano DA, Kenney BD. Rare but serious complications of central line insertion. Semin Pediatr Surg . 2009;18:73–83.

Baird JS, Killinger JS, Kalkbrenner KJ, et al. Massive pulmonary embolism in children. J Pediatr . 2010;156:148–151.

Bonduel M, Hepner M, Sciuccati G, et al. Prothrombotic abnormalities in children with venous thromboembolism. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol . 2000;22:66–72.

Chalmers EA. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in neonates and children. Thromb Res . 2006;118:3–12.

Chatterjee S, Chakraburty A, Weinberg I, et al. Thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism and risk of all-cause mortality, majority bleeding, and intracranial hemorrhage a meta-analysis. JAMA . 2014;311:2414–2421.

Dijk FN, Curtin J, Lord D, Fitzgerald DA. Pulmonary embolism in children. Paediatr Respir Rev . 2012;13:112–122.

Douma RA, Mos ICM, Erkens PMG, et al. Performance of 4 clinical decision rules in the diagnostic management of acute pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med . 2011;154:709–718.

Goldenberg NA, Bernard TJ. Venous thromboembolism in children. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am . 2010;24:151–166.

Goldenberg NA, Knapp-Clevenger R, Durham JD, et al. A thrombolytic regimen for high-risk deep venous thrombosis may substantially reduce the risk of post thrombotic syndrome in children. Blood . 2007;110:45–53.

Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Lancet . 2012;379:1835–1844.

Hochhegger B, Ley-Zaporo zhan J, Marchiori E, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in acute pulmonary embolism. Br J Radiol . 2011;84:282–287.

Holzer R, Peart I, Ciotti G, et al. Successful treatment with rTPA. Pediatr Cardiol . 2002;23:548–552.

Hull RD. Diagnosing pulmonary embolism with improved certainty and simplicity. JAMA . 2006;295:213–215.

Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. New diagnostic strategies for pulmonary embolism. Lancet . 2008;371:1312–1314.

Lapner ST, Kearon C. Diagnosis and management of pulmonary embolism. BMJ . 2013;346:f757.

Lucassen W, Geersing GJ, Erkens PMG, et al. Clinical decision rules for excluding pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med . 2011;155:448–460.

Meyer G, Vicaut E, Danays T, et al. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med . 2014;370:1402–1410.

Monagle P, Adams M, Mahoney M, et al. Outcome of pediatric thromboembolic disease: a report from the Canadian childhood thrombophilia registry. Pediatr Res . 2000;47:763–766.

Nowak-Gottl U, Bidlingmaier C, et al. Pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of LMWHs in venous thrombosis and stroke in neonates, infants and children. Br J Pharmacol . 2008;153:1120–1127.

Nowak-Gottl U, Janssen V, Manner D, et al. Venous thromboembolism in neonates and children–update 2013. Thromb Res . 2013;131:S39–S41.

Paes BA, Nagel K, Sunak I, et al. Neonatal and infant pulmonary thromboembolism: a literature review. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis . 2012;23:653–662.

Parker RI. Thrombosis in the pediatric population. Crit Care Med . 2010;38:S71–S75.

Patocka C, Nemeth J. Pulmonary embolism in pediatrics. J Emerg Med . 2012;42:105–116.

Perrier A, Roy PM, Sanchez O, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med . 2005;352:1760–1768.

Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, et al. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children's hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics . 2009;124:1001–1008.

Stein P, Kayali F, Olson R. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in infants and children: data from the national hospital discharge survey. J Pediatr . 2004;145:563–565.

Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med . 2006;354:2317–2326.

Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med . 2008;358:1037–1052.

The EINSTEIN-PE Investigators. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med . 2012;366:1287–1296.

Van Belle A, Buller HR, Huisman MV, et al. Christopher study investigators: effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and computed tomography. JAMA . 2006;295:172–179.

Young G, Albisetti M, Bonduel M, et al. Impact of inherited thrombophilia on venous thromboembolism in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Circulation . 2008;118:1373–1382.

Zöller B, Li X, Sundquist J, et al. Risk of PE in patients with autoimmune disorders: a nationwide follow-up study from Sweden. Lancet . 2012;379:244–249.

Pulmonary Hemorrhage and Hemoptysis

Mary A. Nevin

Pulmonary hemorrhage is relatively uncommon but a potentially fatal occurrence in children. The patient with suspected hemoptysis may present acutely or subacutely and to a variety of different practitioners with distinct areas of specialty. Diffuse, slow bleeding in the lower airways may become severe and manifest as anemia, fatigue, or respiratory compromise without the patient ever experiencing episodes of hemoptysis. Hemoptysis must also be separated from episodes of hematemesis or epistaxis, each of which may have indistinguishable presentations in the young patient.

Etiology

Table 436.4 and Table 435.1 (in Chapter 435 ) present conditions that can manifest as pulmonary hemorrhage or hemoptysis in children. The chronic (opposed to an acute) presence of a foreign body can lead to inflammation and/or infection, thereby inducing hemorrhage. Bleeding is more likely to occur in association with a chronically retained foreign body of vegetable origin.

Table 436.4

Etiology of Pulmonary Hemorrhage (Hemoptysis)

See also Table 435.1 .

Hemorrhage most commonly reflects chronic inflammation and infection such as that seen with bronchiectasis due to cystic fibrosis or with cavitary disease in association with infectious tuberculosis. Hemoptysis may occasionally reflect an acute and intense infectious condition such as bronchitis or bronchopneumonia.

Other relatively common etiologies are congenital heart disease and trauma. Pulmonary hypertension secondary to cardiac disease is a prominent etiology for hemoptysis in those patients without cystic fibrosis. Traumatic irritation or damage in the airway may be accidental in nature. Traumatic injury to the airway and pulmonary contusion may result from motor vehicle crashes or other direct force injuries. Bleeding can also be related to instrumentation or iatrogenic irritation of the airway as is commonly seen in a child with a tracheostomy or a child with repeated suction trauma to the upper airway. Children who have been victims of nonaccidental trauma or deliberate suffocation can also be found to have blood in the mouth or airway (see Chapter 16 ). Factitious hemoptysis may rarely be encountered in the setting of Factitious Disorder by Proxy (formerly Munchausen's by proxy; see Chapter 16.2 ).

Rare causes for hemoptysis include tumors and vascular anomalies such as arteriovenous malformations (Fig. 436.2 ). Congenital vascular malformations in the lung may also be associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia . Tumors must be cautiously investigated when encountered with a flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope as bleeding may be massive and difficult to control.

Syndromes associated with vasculitic, autoimmune, and idiopathic disorders can be associated with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (see Chapter 435 ).

Acute idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage of infancy is a distinct entity and is described as an episode of pulmonary hemorrhage in a previously healthy infant born at greater than 32 wk of gestation and whose age is less than 1 yr with the following: (1) abrupt or sudden onset of overt bleeding or frank evidence of blood in the airway, (2) severe presentation leading to acute respiratory distress or failure and requiring intensive care and invasive ventilatory support, and (3) diffuse bilateral infiltration on chest radiographs or computed tomography. Prior suggestions of an association between acute idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage of infancy and toxic mold exposure have not been supported on subsequent review.

Epidemiology

The frequency with which pulmonary hemorrhage occurs in the pediatric population is difficult to define. This difficulty is largely related to the variability in disease presentation. Chronic bronchiectasis as seen in cystic fibrosis (see Chapter 432 ) or ciliary dyskinesia (see Chapter 433 ) can cause hemoptysis, but usually occurs in children older than 10 yr of age. The incidence of pulmonary hemorrhage may be significantly underestimated because many children and young adults swallow rather than expectorate mucus, a behavior that may prevent recognition of hemoptysis, the primary presenting symptom of the disorder.

Pathophysiology

Pulmonary hemorrhage can be localized or diffuse. Focal hemorrhage from an isolated bronchial lesion is often secondary to infection or chronic inflammation. Erosion through a chronically inflamed airway into the adjacent bronchial artery is a mechanism for potentially massive hemorrhage. Bleeding from such a lesion is more likely to be bright red, brisk, and secondary to enlarged bronchial arteries and systemic arterial pressures. The severity of more diffuse hemorrhage can be difficult to ascertain. The rate of blood loss may be insufficient to reach the proximal airways. Therefore, the patient may present without hemoptysis. The diagnosis of pulmonary hemorrhage is generally achieved by finding evidence of blood or hemosiderin in the lung. Within 48-72 hr of an episode of bleeding, alveolar macrophages convert the iron from erythrocytes into hemosiderin. It may take weeks to clear these hemosiderin-laden macrophages completely from the alveolar spaces. This fact may allow differentiation between acute and chronic hemorrhage. Hemorrhage is often followed by the influx of neutrophils and other proinflammatory mediators. With repeated or chronic hemorrhage, pulmonary fibrosis can become a prominent pathologic finding.

Clinical Manifestations

The severity of presentation in patients with hemoptysis and pulmonary hemorrhage is highly variable. Older children and young adults with a focal hemorrhage may complain of warmth or a “bubbling” sensation in the chest wall. This can occasionally aid the clinician in locating the area involved. Rapid and large-volume blood loss manifests as symptoms of cyanosis, respiratory distress, and shock. Chronic, subclinical blood loss may manifest as anemia, fatigue, dyspnea, or altered activity tolerance. Less commonly, patients present with persistent infiltrates on chest radiograph or symptoms of chronic illness such as failure to thrive. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations may present with hemoptysis, hemothorax, a round localized mass on x-ray or CT, clubbing, cyanosis, or embolic phenomenon (central nervous system).

Laboratory Findings and Diagnosis

A patient with suspected hemorrhage should have a laboratory evaluation with complete blood count and coagulation studies. The complete blood count result may demonstrate a microcytic, hypochromic anemia but may be normal early in an acute bleeding episode. If iron stores are sufficient, a reticulocytosis may be present. Other laboratory findings are highly dependent on the underlying diagnosis. A urinalysis may show evidence of nephritis in patients with a comorbid pulmonary renal syndrome. The classic and definitive finding in pulmonary hemorrhage is that of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in pulmonary secretions. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages may be detected by sputum analysis with Prussian blue staining when a patient is able to successfully expectorate sputum from the lower airways. In younger children, or in weak or neurodevelopmentally compromised patients unable to expectorate sputum, induced sputum may provide an acceptable specimen; alternatively, a flexible bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage may be required for specimen retrieval.

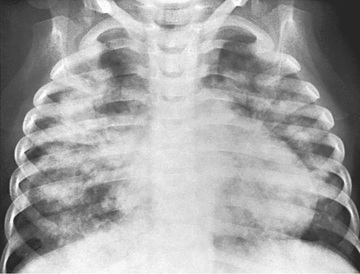

Chest radiographs may demonstrate fluffy bilateral densities, as seen in acute idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage of infancy (Fig. 436.3 ) or the patchy consolidation seen in idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis (Fig. 436.4 ). Alveolar infiltrates seen on chest radiograph may be regarded as a representation of recent bleeding, but their absence does not rule out the occurrence of pulmonary hemorrhage. Infiltrates, when present, are often symmetric and diffuse and may be preferentially located in the perihilar regions and lower lobes. The costophrenic angles and lung apices are frequently spared. CT may be indicated to assess for underlying disease processes.

Lung biopsy is rarely necessary unless bleeding is chronic or an etiology cannot be determined with other methods. Pulmonary function testing, including a determination of gas exchange, is important to assess the severity of the ventilatory defect. In older children, spirometry may demonstrate evidence of predominantly obstructive disease in the acute period. Restrictive disease secondary to fibrosis is typically seen with more chronic disease. Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide measurements are typically elevated in the setting of pulmonary hemorrhage because of the strong affinity of the intra-alveolar hemoglobin for carbon monoxide.

Treatment

In the setting of massive blood loss, volume resuscitation and transfusion of blood products are necessary. Maintenance of adequate ventilation and circulatory function is crucial. Rigid bronchoscopy may be utilized for localization of bleeding and for removal of debris, but active bleeding may be exacerbated by airway manipulation. Flexible bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage may be required for diagnosis. Ideally, treatment is directed at the specific pathologic process responsible for the hemorrhage. When bronchiectasis is a known entity and a damaged artery can be localized, bronchial artery embolization is often the therapy of choice. If embolization fails, total or partial lobectomy may be required. Embolization is the initial treatment of choice for an arteriovenous malformation. In circumstances of diffuse hemorrhage, corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents have been shown to be of benefit. Transcatheter vaso-occlusive embolotherapy with detachable stainless-steel coils or other occlusive devices is the treatment of choice for pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (pulmonary AVM). Prognosis depends largely on the underlying disease process and the chronicity of bleeding.

Bibliography

Bartyik K, Bede O, Tiszlavicz L, et al. Pulmonary capillary haemangiomatosis in children and adolescents: report of a new case and a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr . 2004;163:731–737.

Brown CM, Redd SC, Damon SA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Acute idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage among infants: recommendations from the working group for investigation and surveillance. MMWR Recomm Rep . 2004;53:1–12.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Investigation of acute idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage among infants—Massachusetts, December 2002-June 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2004;53:817–820.

Coss-Bu JA, Sachdeva RC, Bricker JT, et al. Hemoptysis: a 10-year retrospective study. Pediatrics . 1997;100:E7.

Cottin V, Chinet T, Lavolé A, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: a series of 126 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) . 2007;86:1–17.

Di Nisio M, van Es N, Büller HR. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Lancet . 2016;388:3060–3069.

Godfrey S. Pulmonary hemorrhage/hemoptysis in children. Pediatr Pulmonol . 2004;37:476–484.

Grzela K, Krenke K, Kulus M. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: clinical and radiological presentation. J Pediatr . 2011;158:856.

Hennelly KE, Baskin MN, Monuteuax MC, et al. Detection of pulmonary embolism in high-risk children. J Pediatr . 2016;178:214–218.

Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Chest . 2016;149(2):315–352.

Konstantinides SV, Barco S, Lankeit M, Meyer G. Management of pulmonary embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2016;67(8):976–990.

Mismetti P, Laporte S, Pellerin O, et al. Effect of retrievable inferior vena cava filter plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone on risk of recurrent pulmonary embolism—a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2015;313(16):1627–1635.

Ryu JS, Song ES, Lee KH, et al. Natural history and therapeutic implications of patients with catamenial hemoptysis. Respir Med . 2007;101:1022–1036.

van der Hulle T, Dronkers CEA, Klok FA, Huisman MV. Recent developments in the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary embolism. J Intern Med . 2016;279:16–29.

van der Hulle T, van Es N, den Exter PL, et al. Is a normal computed tomography pulmonary angiography safe to rule out acute pulmonary embolism in patients with a likely clinical probability? Thromb Haemostasis . 2017;117(8):1622–1629.