Cutaneous Bacterial Infections

Impetigo

Daren A. Diiorio, Stephen R. Humphrey

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Impetigo is the most common skin infection in children throughout the world. There are 2 classic forms of impetigo: nonbullous and bullous.

Staphylococcus aureus is the predominant organism of nonbullous impetigo in the United States (see Chapter 208 ); group A β-hemolytic streptococci (GABHS) are implicated in the development of some lesions (see Chapter 210 ). The staphylococcal types that cause nonbullous impetigo are variable but are not generally from phage group 2, the group that is associated with scalded skin and toxic shock syndromes. Staphylococci generally spread from the nose to normal skin and then infect the skin. In contrast, the skin becomes colonized with GABHS an average of 10 days before development of impetigo. The skin serves as the source for acquisition of GABHS and is the probable primary source for spread of impetigo. Lesions of nonbullous impetigo that grow staphylococci in culture cannot be distinguished clinically from those that grow pure cultures of GABHS.

Bullous impetigo is always caused by S. aureus strains that produce exfoliative toxins. The staphylococcal exfoliative toxins (ETA, ETB, ETD) blister the superficial epidermis by hydrolyzing human desmoglein 1, resulting in a subcorneal vesicle. This is also the target antigen of the autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus.

Clinical Manifestations

Nonbullous Impetigo

Nonbullous impetigo accounts for more than 70% of cases. Lesions typically begin on the skin of the face or on extremities that have been traumatized. The most common lesions that precede nonbullous impetigo are insect bites, abrasions, lacerations, chickenpox, scabies pediculosis, and burns. A tiny vesicle or pustule forms initially and rapidly develops into a honey-colored crusted plaque that is generally <2 cm in diameter (Fig. 685.1 ). The infection may be spread to other parts of the body by the fingers, clothing, and towels. Lesions are associated with little to no pain or surrounding erythema, and constitutional symptoms are generally absent. Pruritus occurs occasionally, regional adenopathy is found in up to 90% of cases, and leukocytosis is present in approximately 50%.

Bullous Impetigo

Bullous impetigo is mainly an infection of infants and young children. Flaccid, transparent bullae develop most commonly on skin of the face, buttocks, trunk, perineum, and extremities. Neonatal bullous impetigo can begin in the diaper area. Rupture of a bulla occurs easily, leaving a narrow rim of scale at the edge of shallow, moist erosion. Surrounding erythema and regional adenopathy are generally absent. Unlike those of nonbullous impetigo, lesions of bullous impetigo are a manifestation of localized staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and develop on intact skin.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of nonbullous impetigo includes viruses (herpes simplex, varicella-zoster), fungi (tinea corporis, kerion), arthropod bites, and parasitic infestations (scabies, pediculosis capitis), all of which may become impetiginized.

The differential diagnosis of bullous impetigo in neonates includes epidermolysis bullosa, bullous mastocytosis, herpetic infection, and early staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. In older children, allergic contact dermatitis, burns, erythema multiforme, linear immunoglobulin A dermatosis, pemphigus, and bullous pemphigoid must be considered, particularly if the lesions do not respond to therapy.

Complications

Potential but very rare complications of either nonbullous or bullous impetigo include bacteremia with subsequent osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, pneumonia, and septicemia. Positive blood culture results are very rare in otherwise healthy children with localized lesions. Cellulitis has been reported in up to 10% of patients with nonbullous impetigo and rarely follows the bullous form. Lymphangitis, suppurative lymphadenitis, guttate psoriasis, and scarlet fever occasionally follow streptococcal disease. There is no correlation between number of lesions and clinical involvement of the lymphatics or development of cellulitis in association with streptococcal impetigo.

Infection with nephritogenic strains of GABHS may result in acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (see Chapter 537.4 ). The clinical character of impetigo lesions does not predict the development of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Children 3-7 yr of age are most commonly affected. The latent period from onset of impetigo to development of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis averages 18-21 days, which is longer than the 10-day latency period after pharyngitis. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis occurs epidemically after either pharyngeal or skin infection. Impetigo-associated epidemics have been caused by M groups 2, 49, 53, 55, 56, 57, and 60. Strains of GABHS that are associated with endemic impetigo in the United States have little or no nephritogenic potential. Acute rheumatic fever does not occur as a result of impetigo.

Treatment

The decision on how to treat impetigo depends on the number of lesions and their locations. Topical therapy with mupirocin 2%, and retapamulin 1% 2-3 times a day for 10-14 days is acceptable for localized disease caused by S. aureus.

Systemic therapy with oral antibiotics should be prescribed for patients with streptococcal or widespread involvement of staphylococcal infections; when lesions are near the mouth, where topical medication may be licked off; or in cases with evidence of deep involvement, including cellulitis, furunculosis, abscess formation, or suppurative lymphadenitis. Cephalexin, 25-50 mg/kg/day in 3-4 divided doses for 7 days, is an excellent choice for initial therapy. A culture should be performed, as the emergence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) typically requires a different antibiotic choice based on antibiotic susceptibility patterns. If MRSA is suspected, clindamycin, doxycycline or sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is indicated. No evidence suggests that a 10-day course of therapy is superior to a 7-day course; twice daily sulfamethoxazole trimethoprim for 3 days has been comparable to once daily for 5 days. Benzathine benzylpenicillin IM has been used when compliance with multiple dose and day oral antibiotics may be poor.

Bibliography

Bangert S, Levy M, Herbert AA. Bacterial resistance and impetigo treatment trends: a review. Pediatr Dermatol . 2012;29:243–248.

Bowen AC, Tong SYC, Andrews RM, et al. Short-course oral co-trimoxazole versus intramuscular benzathine benzylpenicillin for impetigo in a highly endemic region: an open-label, randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet . 2014;384:2132–2140.

Chen AE, Carroll KC, Diener-West M. Randomized controlled trial of cephalexin versus clindamycin for uncomplicated pediatric skin infections. Pediatrics . 2011;127(3):e573–e580.

Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician . 2014;90(4):229–235.

Koning S, van der Sande R, Verhagen AP, et al. Interventions for impetigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2012;(1) [CD003261].

Subcutaneous Tissue Infections

Daren A. Diiorio, Stephen R. Humphrey

The principal determinations for soft-tissue infections is whether it is nonnecrotizing or necrotizing, as well as purulent or nonpurulent (see Fig. 685.2 ). The former responds to antibiotic therapy alone, whereas the latter requires prompt surgical removal of all devitalized tissue in addition to antimicrobial therapy. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections are life-threatening conditions that are characterized by rapidly advancing local tissue destruction and systemic toxicity including shock. Tissue necrosis distinguishes them from cellulitis. In cellulitis, an inflammatory infectious process involves subcutaneous tissue but does not destroy it. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections may initially manifest with a paucity of early cutaneous signs relative to the rapidity and degree of destruction of the subcutaneous tissues.

Cellulitis

Etiology

Cellulitis is characterized by infection and inflammation of loose connective tissue, with limited involvement of the dermis and relative sparing of the epidermis. A break in the skin from previous trauma, surgery, or an underlying skin lesion predisposes to cellulitis. Cellulitis is also more common in individuals with lymphatic stasis, diabetes mellitus, or immunosuppression.

S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus) are the most common etiologic agents. In patients who are immunocompromised or have diabetes mellitus, other bacterial or fungal agents may be involved, notably Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Aeromonas hydrophila and, occasionally, other Enterobacteriaceae; Legionella spp.; the Mucorales, particularly Rhizopus spp., Mucor spp., and Absidia spp.; and Cryptococcus neoformans. Children with relapsed nephrotic syndrome may experience cellulitis caused by Escherichia coli. In children 3 mo to 5 yr of age, Haemophilus influenzae type b was once an important cause of facial cellulitis, but its incidence has declined significantly since the institution of immunization against this organism.

Clinical Manifestations

Cellulitis manifests clinically as a localized area of edema, warmth, erythema, and tenderness. The lateral margins tend to be indistinct because the process is deep in the skin, primarily involving the subcutaneous tissues in addition to the dermis. Application of pressure may produce pitting. Although distinction cannot be made with certainty in any particular patient, cellulitis due to S. aureus tends to be more localized and may suppurate, whereas infections caused by S. pyogenes (group A streptococci) tend to spread more rapidly and may be associated with lymphangitis. Regional adenopathy and constitutional signs and symptoms such as fever, chills, and malaise are common. Complications of cellulitis are uncommon but include subcutaneous abscess, bacteremia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, thrombophlebitis, endocarditis, and necrotizing fasciitis. Lymphangitis or glomerulonephritis can also follow infection with S. pyogenes.

Diagnosis

Cellulitis in a neonate should prompt assessment for invasive bacterial infection, including blood culture; lumbar puncture is also usually performed though its necessity for mild cases of cellulitis is controversial in this age group. In older children, cultures of blood or cutaneous aspirates, biopsies or swabs are not routinely recommended. However, blood cultures should be considered if the patient is younger than 1 yr of age, if signs of systemic toxicity are present, if an adequate examination cannot be carried out, or if an immunocompromising condition (e.g., malignancy, neutropenia) is present. Aspirates from the site of inflammation, skin biopsy, and blood cultures allow identification of the causal organism in approximately 25% of cases of cellulitis. Yield of the causative organism is approximately 30% when the site of origin of the cellulitis is apparent, such as an abrasion or ulcer. An aspirate taken from the point of maximum inflammation yields the causal organism more often than a leading-edge aspirate. Lack of success in isolating an organism stems primarily from the low number of organisms present within the lesion. Ultrasonography can be performed if an associated subcutaneous abscess is suspected.

The differential diagnosis includes an exuberant immune-allergic reaction to insect bites particularly mosquito bites (Skeeter syndromes) (see Chapter 171 ). The Skeeter syndrome is characterized by swelling disproportionate to erythema; there is pruritus but usually no tenderness. In addition, cold panniculitis may appear as an erythematous but usually nontender swelling after exposure to cold, such as sledding or eating a cold Popsicle (see Chapter 680.1 ).

Treatment

Empirical antibiotic therapy for cellulitis and the initial route of administration should be guided by the age and immune status of the patient, history of the illness, and location and severity of the cellulitis (Fig. 685.2 ).

Neonates should receive an intravenous antibiotic with a β-lactamase–stable antistaphylococcal antibiotic such as nafcillin, cefazolin, or vancomycin, and an aminoglycoside such as gentamicin or a 3rd-generation cephalosporin such as cefotaxime.

In infants and children older than 2 mo with mild to moderate infections, particularly if fever, lymphadenopathy, and other constitutional signs are absent, treatment of cellulitis may be initiated orally on an outpatient basis with a penicillinase-resistant penicillin such as dicloxacillin or a 1st-generation cephalosporin such as cephalexin or, if MRSA is suspected, with clindamycin. Some recommend trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole although it does not provide ideal coverage against S. pyogenes , a potential cause of cellulitis without abscess. A randomized trial of 500 children >12 yr and adults did not demonstrate significant differences in treatment failure between those treated with cephalexin alone compared with those treated with a combination of cephalexin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Intravenous antibiotics may be necessary if improvement is not noted or the disease progresses significantly in the 1st 24-48 hr of therapy. Infants and children older than 2 mo with signs of systemic infection, including fever, lymphadenopathy, or constitutional signs, also require hospitalization and treatment with intravenous antibiotics effective against S. pyogenes and S. aureus , such as clindamycin or a 1st-generation cephalosporin (cefazolin). If the child is severely ill or toxic appearing, consideration should be given to the addition of clindamycin or vancomycin if these antibiotics were not started initially. Other agents for complicated skin and skin structure infections caused by MRSA or S. pyogenes have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in adults, including dalbavancin (intravenous given once weekly), ceftaroline (IV), telavancin (IV), linezolid (oral or IV), tedizolid (oral or IV), and oritavancin (IV). Dalbavacin also provides activity against vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

In unimmunized patients, antibiotic treatment may include a 3rd-generation cephalosporin (cefepime, ceftriaxone, or if available cefotaxime) or a β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combination (e.g., ampicillin-sulbactam), which provide coverage for H. influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae .

Once the erythema, warmth, edema, and fever have decreased significantly, a 5- to 7-day total course of treatment may be completed on an outpatient basis though treatment should be extended if the infection has not substantially improved with this time period. Elevation of an affected limb, particularly early in the course of therapy, may help reduce swelling and pain. If present, a subcutaneous abscess should be drained.

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Etiology

Necrotizing fasciitis is a subcutaneous tissue infection that involves the deep layer of superficial fascia but may spare adjacent epidermis, deep fascia, and muscle.

Relatively few organisms possess sufficient virulence to cause necrotizing fasciitis when acting alone. Most (55–75%) cases of necrotizing fasciitis are polymicrobial (synergistic necrotizing fasciitis), with an average of 4 different organisms isolated. The organisms most commonly isolated in polymicrobial necrotizing fasciitis are S. aureus , streptococcal species, Klebsiella species, E. coli, and anaerobic bacteria.

The rest of the cases and the most fulminant infections, associated with toxic shock syndrome and a high case fatality rate, are usually caused by S. pyogenes (group A streptococcus) (see Chapter 210 ). Streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis may occur in the absence of toxic shock–like syndrome and is potentially fatal and associated with substantial morbidity. Necrotizing fasciitis can occasionally be caused by S. aureus; Clostridium perfringens; Clostridium septicum; P. aeruginosa; Vibrio spp., particularly Vibrio vulnificus; and fungi of the order Mucorales, particularly Rhizopus spp., Mucor spp., and Absidia spp. Necrotizing fasciitis has also been reported, on rare occasions, to result from nongroup A streptococci such as group B, C, F, or G streptococci, S. pneumoniae, or H. influenzae type b.

Infections caused by any organism or combination of organisms cannot be distinguished clinically from one another, although development of crepitus signals the presence of gas-forming organisms: Clostridium spp. or Gram-negative bacilli such as E. coli, Klebsiella, Proteus, or Aeromonas.

Clinical Manifestations

Necrotizing fasciitis may occur anywhere on the body. Polymicrobial infections tend to occur on perineal and trunk areas. The incidence of necrotizing fasciitis is highest in hosts with systemic or local tissue immunocompromise, such as those with diabetes mellitus, neoplasia, or peripheral vascular disease as well as those who have recently undergone surgery, who abuse intravenous drugs, or who are undergoing immunosuppressive treatment, particularly with corticosteroids. The infection can also occur in healthy individuals after minor puncture wounds, abrasions, or lacerations; blunt trauma; surgical procedures, particularly of the abdomen, gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts, or the perineum; or hypodermic needle injection.

There has been a resurgence of fulminant necrotizing soft-tissue infections caused by S. pyogenes, which may occur in previously healthy individuals. Streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis is classically located on an extremity. There may be a history of recent trauma to or operation in the area. Necrotizing fasciitis due to S. pyogenes may also occur after superinfection of varicella lesions. Children with this disease have tended to display onset, recrudescence, or persistence of high fever and signs of toxicity after the 3rd or 4th day of varicella. Common predisposing conditions in neonates are omphalitis and balanitis after circumcision.

Necrotizing fasciitis begins with acute onset of local, and at times tense, edema, erythema, tenderness, and heat. Fever is usually present, and pain, tenderness, and constitutional signs are disproportionate to cutaneous signs, especially with involvement of fascia and muscle. Lymphangitis and lymphadenitis may or may not be present. The infection advances along the superficial fascial plane, and initially there may be few cutaneous signs to herald the serious nature and extent of the subcutaneous tissue necrosis that is occurring. Skin changes may appear over 24-48 hr as nutrient vessels are thrombosed and cutaneous ischemia develops. Early clinical findings include ill-defined cutaneous erythema and edema that extends beyond the area of erythema. Additional signs include formation of bullae filled initially with straw-colored and later bluish to hemorrhagic fluid, and darkening of affected tissues from red to purple to blue. Skin anesthesia and, finally, frank tissue gangrene and slough develop owing to the ischemia and necrosis. Vesiculation or bulla formation, ecchymoses, crepitus, anesthesia, and necrosis are ominous signs indicative of advanced disease. Children with varicella lesions may initially show no cutaneous signs of superinfection with invasive S. pyogenes, such as erythema or swelling. Significant systemic toxicity may accompany necrotizing fasciitis, including shock, organ failure, and death. Advance of the infection in this setting can be rapid, progressing to death within hours. Patients with involvement of the superficial or deep fascia and muscle tend to be more acutely and systemically ill and have more rapidly advancing disease than those with infection confined solely to subcutaneous tissues above the fascia. In an extremity, a compartment syndrome may develop, manifesting as tight edema, pain on motion, and loss of distal sensation and pulses; this is a surgical emergency.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis is made by surgical exploration, which should be undertaken as soon as the diagnosis is suspected. Necrotic fascia and subcutaneous tissue are gray and offer little resistance to blunt probing. Although CT and MRI aid in delineating the extent and tissue planes of involvement, these procedures should not delay surgical intervention. Frozen-section incisional biopsy specimens obtained early in the course of the infection can aid management by decreasing the time to diagnosis and helping to establish the margins of involvement. Gram staining of tissue can be particularly useful if chains of Gram-positive cocci, indicative of infection with S. pyogenes, are seen.

Treatment

Early supportive care, surgical debridement, and parenteral antibiotic administration are mandatory for necrotizing fasciitis. All devitalized tissue should be removed to freely bleeding edges, and repeat exploration is generally indicated within 24-36 hr to confirm that no necrotic tissue remains. This procedure may need to be repeated on several occasions until devitalized tissue has ceased to form. Meticulous daily wound care is also paramount.

Parenteral antibiotic therapy should be initiated as soon as possible with broad-spectrum agents against all potential pathogens. Initial empirical therapy should be instituted with vancomycin, linezolid, or daptomycin to cover Gram-positive organisms, and piperacillin-tazobactam to cover Gram-negative organisms. An alternative is to add ceftriaxone with metronidazole to cover mixed aerobic–anaerobic organisms. Definitive therapy should then be based on sensitivity of isolated organisms. Penicillin with clindamycin is indicated for necrotizing fasciitis caused by either group A streptococcus or Clostridium spp. For group A streptococcus infections, clindamycin is administered until the patient is hemodynamically stable and no longer requires surgical debridement. Unlike penicillin, the effectiveness of clindamycin is not influenced by the infectious burden or bacterial stage of growth, thus its addition early in the course of infection may lead to more rapid bacterial killing. Doxycycline plus either ciprofloxacin or ceftazidime is recommended for Vibrio vulnificus necrotizing fasciitis. Duration of therapy for necrotizing fasciitis depends on the course of the illness. Antibiotics are generally continued for at least 5 days after signs and symptoms of local signs and symptoms have resolved; the typical duration of therapy is 4 wk. Many centers employ hyperbaric oxygen therapy, although it should not delay resuscitation of shock or surgical debridement.

Prognosis

The combined case fatality rate among children and adults with necrotizing fasciitis and syndrome due to polymicrobial infection or S. pyogenes has been as high as 60%. However, death is less common in children and in cases not complicated by toxic shock–like syndrome.

Bibliography

Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, et al. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med . 2014;370:2169–2178.

Cardona AF, Wilson SE. Skin and soft-tissue infections: a critical review and the role of telavancin in their treatment. Clin Infect Dis . 2015;61(Suppl 2):S69–S79.

Halilovic J, Heintz BH, Brown J. Risk factors for clinical failure in patients hospitalized with cellulitis and cutaneous abscess. J Infect . 2012;65:128–134.

King E, Chun R, Sulman C. Pediatric cervicofacial necrotizing fasciitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2012;138:372–375.

Malone JR, Durica SR, Thompson DM, et al. Blood cultures in the evaluation of uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatrics . 2013;132:454–459.

Marin JR, Dean AJ, Bilker WB, et al. Emergency ultrasound-assisted examination of skin and soft tissue infections in the pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med . 2013;20:545–553.

Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Mower WR, et al. Effect of cephalexin plus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole vs. cephalexin alone on clinical cure of uncomplicated cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2017;317(20):2088–2096.

Phoenix G, Das S, Joshi M. Diagnosis and management of cellulitis. BMJ . 2012;345:e4955.

Prokocimer P, De Anda C, Fang E, et al. Tedizolid phosphate vs linezolid for treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. JAMA . 2013;309:559–568.

Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: a review. JAMA . 2016;316:325–337.

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis . 2014;59:147–159.

Sultan HY, Boyle AA, Sheppard N. Necrotising fasciitis. BMJ . 2012;344:e2865.

The Medical Letter. Two new drugs for skin and skin structure infections. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2014;56:73–76.

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Orbactiv to treat skin infections . http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm408475.htm .

Zabielinski M, McLeod MP, Aber C, et al. Trends and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus in an outpatient dermatology facility. JAMA Dermatol . 2013;149:427–432.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (Ritter Disease)

Daren A. Diiorio, Stephen R. Humphrey

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is caused predominantly by phage group 2 staphylococci, particularly strains 71 and 55, which are present at localized sites of infection. Foci of infection include the nasopharynx and, less commonly, the umbilicus, urinary tract, a superficial abrasion, conjunctivae, and blood. The clinical manifestations of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome are mediated by hematogenous spread, in the absence of specific antitoxin antibody of staphylococcal epidermolytic or exfoliative toxins A or B. The toxins have reproduced the disease in both animal models and human volunteers. Decreased renal clearance of the toxins may account for the fact that the disease is most common in infants and young children, as well as a lack of protection from antitoxin antibodies. Epidermolytic toxin A is heat stable and is encoded by bacterial chromosomal genes. Epidermolytic toxin B is heat labile and is encoded on a 37.5 kb plasmid. The site of blister cleavage is subcorneal. The epidermolytic toxins produce the split by binding to and cleaving desmoglein 1. Intact bullae are consistently sterile, unlike those of bullous impetigo, but culture specimens should be obtained from all suspected sites of localized infection and from the blood to identify the source for elaboration of the epidermolytic toxins.

Clinical Manifestations

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, which occurs predominantly in infants and children younger than 5 yr of age, includes a range of disease from localized bullous impetigo to generalized cutaneous involvement with systemic illness. Onset of the rash may be preceded by malaise, fever, irritability, and exquisite tenderness of the skin. Scarlatiniform erythema develops diffusely and is accentuated in flexural and periorificial areas. The conjunctivae are inflamed and occasionally become purulent. The brightly erythematous skin may rapidly acquire a wrinkled appearance, and in severe cases, sterile, flaccid blisters and erosions develop diffusely. Circumoral erythema is characteristically prominent, as is radial crusting and fissuring around the eyes, mouth, and nose. At this stage, areas of the epidermis may separate in response to gentle shear force (Nikolsky sign; Fig. 685.3 ). As large sheets of epidermis peel away, moist, glistening, denuded areas become apparent, initially in the flexures and subsequently over much of the body surface (Fig. 685.4 ). This development may lead to secondary cutaneous infection, sepsis, and fluid and electrolyte disturbances. The desquamative phase begins after 2-5 days of cutaneous erythema; healing occurs without scarring in 10-14 days. Patients may have pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, and superficial erosions of the lips, but intraoral mucosal surfaces are spared. Although some patients appear ill, many are reasonably comfortable except for the marked skin tenderness.

Differential Diagnosis

A presumed abortive form of the disease manifests as diffuse, scarlatiniform, tender erythroderma that is accentuated in the flexural areas but does not progress to blister formation. In patients with this form, Nikolsky sign may be absent. Although the exanthem is similar to that of streptococcal scarlet fever, strawberry tongue and palatal petechiae are absent. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome may be mistaken for a number of other blistering and exfoliating disorders, including bullous impetigo, epidermolysis bullosa, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, pemphigus, drug eruption, erythema multiforme, and drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis. Toxic epidermal necrolysis can often be distinguished by a history of drug ingestion, the presence of Nikolsky sign only at sites of erythema, the absence of perioral crusting, full-thickness epidermal necrosis, and a blister cleavage plane in the lowermost epidermis.

Histology

A subcorneal, granular layer split can be identified on skin biopsy. Absence of an inflammatory infiltrate is characteristic. Histology is identical to that seen in pemphigus foliaceus, bullous impetigo, and subcorneal pustular dermatosis.

Treatment

Systemic therapy, given either orally in cases of localized involvement or parenterally with a semisynthetic antistaphylococcal penicillin (e.g., nafcillin), first-generation cephalosporin (e.g., cefazolin), clindamycin, or vancomycin if MRSA is considered, should be prescribed. Clindamycin is typically used in addition to other agents, as it is thought to inhibit bacterial protein (toxin) synthesis. The skin should be gently moistened and cleansed. Application of an emollient provides lubrication and decreases discomfort. Topical antibiotics are unnecessary. In neonates, or in infants or children with severe infection, hospitalization is mandatory, with attention to fluid and electrolyte management, infection control measures, pain management, and meticulous wound care with contact isolation. In particularly severe disease, care in an intensive care or burn unit is required. Recovery is usually rapid, but complications, such as excessive fluid loss, electrolyte imbalance, faulty temperature regulation, pneumonia, septicemia, and cellulitis, may cause increased morbidity.

Bibliography

Braunstein I, Wanat KA, Abuabara K, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol . 2014;31:305–308.

Courjon J, Hubiche T, Phan A, et al. Skin findings of Staphylococcus aureus toxin-mediated infection in relation to toxin encoding genes. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 2013 Jul;32(7):727–730; 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828e89f5 .

Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol . 2014;28(11):1418–1423.

Ecthyma

Daren A. Diiorio, Stephen R. Humphrey

See also Chapters 208 , 210 , and 232 .

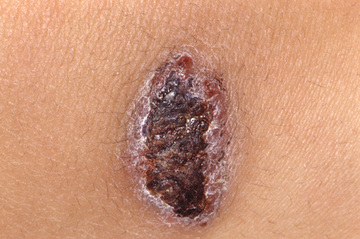

Ecthyma resembles nonbullous impetigo in onset and appearance but gradually evolves into a deeper, more chronic infection. The initial lesion is a vesicle or vesicular pustule with an erythematous base that erodes through the epidermis into the dermis to form an ulcer with elevated margins. The ulcer becomes obscured by a dry, heaped-up, tightly adherent crust (Fig. 685.5 ) that contributes to the persistence of the infection and scar formation. Lesions may be spread by autoinoculation, may be as large as 4 cm, and occur most frequently on the legs. Predisposing factors include the presence of pruritic lesions, such as insect bites, scabies, or pediculosis, that are subject to frequent scratching; poor hygiene; and malnutrition. Complications include lymphangitis, cellulitis, and, rarely, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. The causative agent is usually GABHS; S. aureus is also cultured from most lesions but is probably a secondary pathogen. Crusts should be softened with warm compresses and removed. Systemic antibiotic therapy, as for impetigo, is indicated; almost all lesions are responsive to treatment with penicillin.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is a necrotic ulcer covered with a gray-black eschar. It is usually a sign of P. aeruginosa infection, most often occurring in immunosuppressed patients. Neutropenia is a risk factor for ecthyma gangrenosum. Ecthyma gangrenosum occurs in up to 6% of patients with systemic P. aeruginosa infection but can also occur as a primary cutaneous infection by inoculation. The lesion begins as a red or purpuric macule that vesiculates and then ulcerates. There is a surrounding rim of pink to violaceous skin. The punched-out ulcer develops raised edges with a dense, black, depressed, crusted center. Lesions may be single or multiple. Patients with bacteremia commonly have lesions in apocrine areas. Clinically similar lesions may also develop as a result of infection with other agents, such as S. aureus, A. hydrophila, Enterobacter spp., Proteus spp., Burkholderia cepacia, Serratia marcescens, Aspergillus spp., Mucorales, E. coli, and Candida spp. There is bacterial invasion of the adventitia and media of dermal veins but not arteries. The intima and lumina are spared. Blood and skin biopsy specimens for culture should be obtained, and empirical broad-spectrum, systemic therapy that includes coverage for P. aeruginosa (e.g., antipseudomonal penicillin and an aminoglycoside, cefepime) should be initiated as soon as possible.

Bibliography

Goolamali SI, Fogo A, Killian L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum: an important feature of pseudomonal sepsis in a previously well child. Clin Exp Dermatol . 2008;34:e180–e182.

Paller AS, Mancini AJ. Hurwitz clinical pediatric dermatology: a textbook of skin disorders of childhood and adolescence . ed 5. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2016:334–359.

Vaiman M, Lazarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum and ecthyma-like lesions: review article. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis . 2015;34(4):633–669.

Other Cutaneous Bacterial Infections

Daren A. Diiorio, Stephen R. Humphrey

Blastomycosis-Like Pyoderma (Pyoderma Vegetans)

Blastomycosis-like pyoderma is an exuberant cutaneous reaction to bacterial infection that occurs primarily in children who are malnourished and immunosuppressed. The organisms most commonly isolated from lesions are S. aureus and group A streptococcus, but several other organisms have been associated with these lesions, including P. aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, diphtheroids, Bacillus spp., and C. perfringens. Crusted, hyperplastic plaques on the extremities are characteristic, sometimes forming from the coalescence of many pinpoint, purulent, crusted abscesses (Fig. 685.6 ). Ulceration and sinus tract formation may develop, and additional lesions may appear at sites distant from the site of inoculation. Regional lymphadenopathy is common, but fever is not. Histopathologic examination reveals pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses composed of neutrophils and/or eosinophils. Giant cells are usually lacking. The differential diagnosis includes deep fungal infection, particularly blastomycosis (Fig. 685.7 ) and tuberculous and atypical mycobacterial infection. Underlying immunodeficiency should be ruled out, and the selection of antibiotics should be guided by susceptibility testing because the response to antibiotics is often poor.

Blistering Distal Dactylitis

Blistering distal dactylitis is a superficial blistering infection of the volar fat pad on the distal portion of the finger or thumb that typically affects infants and young children. (Fig. 685.8 ). More than 1 finger may be involved, as may the volar surfaces of the proximal phalanges, palms, and toes. Blisters are filled with a watery purulent fluid; polymorphonuclear leukocytes and Gram-positive cocci are identified on Gram stain. Patients commonly have no preceding history of trauma, and systemic symptoms are generally absent. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis has not occurred after blistering distal dactylitis. The infection is caused most commonly by group A streptococcus but has also occurred as a result of infection with S. aureus. If left untreated, blisters may continue to enlarge and extend to the paronychial area. The infection responds to incision and drainage and a 10-day course of an antibiotic effective against group A Streptococcus and S. aureus (e.g., amoxicillin-clavulanate, clindamycin, cephalexin); patients may require initial intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Perianal Infectious Dermatitis

Perianal infectious dermatitis presents most commonly in boys (70% of cases) between the ages of 6 mo and 10 yr as perianal dermatitis (90% of cases) and pruritus (80% of cases; Fig. 685.9 ). The incidence of perianal infectious dermatitis is not known precisely but ranges from 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 218 patient visits. When GABHS is suspected, it is often referred to as perianal streptococcal dermatitis. The rash is superficial, erythematous, well marginated, nonindurated, and confluent from the anus outward. Acutely (<6 wk), the rash tends to be bright red, moist, and tender to touch. At this stage, a white pseudomembrane may be present. As the rash becomes more chronic, the perianal eruption may consist of painful fissures, a dried mucoid discharge, or psoriasiform plaques with yellow peripheral crust. In girls, the perianal rash may be associated with vulvovaginitis. In boys, the penis may be involved. Approximately 50% of patients have rectal pain, most commonly described as burning inside the anus during defecation, and 33% have blood-streaked stools. Fecal retention is a frequent behavioral response to the infection. Patients also have presented with guttate psoriasis. Although local induration or edema may occur, constitutional symptoms, such as fever, headache, and malaise, are absent, suggesting that subcutaneous involvement, as in cellulitis, is absent. Familial spread of perianal infectious dermatitis is common, particularly when family members bathe together or use the same water.

Perianal infectious dermatitis is usually caused by GABHS, but it may also be caused by S. aureus. The index case and family members should undergo culture; follow-up cultures to document bacteriologic cure after a course of treatment are recommended.

The differential diagnosis of perianal infectious dermatitis includes psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, candidiasis, pinworm infestation, sexual abuse, and inflammatory bowel disease.

For GABHS perianal infectious dermatitis, treatment with a 7-day course of cefuroxime (20 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses) is superior to treatment with penicillin. Concomitant topical mupirocin ointment 2-3 times a day also may be used. If S. aureus is cultured, treatment should be based on sensitivities.

Erysipelas

See Chapter 210 .

Folliculitis

Folliculitis, or superficial infection of the hair follicle, is most often caused by S. aureus (Bockhart impetigo). The lesions are typically small, discrete, dome-shaped pustules with an erythematous base, located at the ostium of the pilosebaceous canals (Fig. 685.10 ). Hair growth is unimpaired, and the lesions heal without scarring. Favored sites include the scalp, buttocks, and extremities. Poor hygiene, maceration, drainage from wounds and abscesses, and shaving of the legs can be provocative factors. Folliculitis can also occur as a result of tar therapy or occlusive wraps. The moist environment encourages bacterial proliferation. In HIV-infected patients, S. aureus may produce confluent erythematous patches with satellite pustules in intertriginous areas and violaceous plaques composed of superficial follicular pustules in the scalp, axillae, or groin. The differential diagnosis includes Candida, which may cause satellite follicular papules and pustules surrounding erythematous patches of intertrigo (particularly in groin/buttocks), and Malassezia furfur, which produces 2-3 mm, pruritic, erythematous, perifollicular papules and pustules on the back, chest, and extremities, particularly in patients who have diabetes mellitus or are taking corticosteroids or antibiotics. Diagnosis is made by examining potassium hydroxide–treated scrapings from lesions. Detection of Malassezia may require a skin biopsy, demonstrating clusters of yeast and short, branching hyphae (“macaroni and meatballs”) in widened follicular ostia mixed with keratinous debris.

Topical antibiotic therapy (e.g., clindamycin 1% lotion or solution twice a day) is usually all that is needed for mild cases, but more severe cases may require the use of a systemic antibiotic such as dicloxacillin or cephalexin. Bacterial culture should be performed in treatment-resistant cases. In chronic recurrent folliculitis, daily application of a benzoyl peroxide 5% gel or wash may facilitate resolution. Dilute bleach baths may also be effective in reducing recurrence.

Folliculitis barbae (sycosis barbae) is a deeper, more severe recurrent inflammatory form of folliculitis caused by S. aureus that involves the entire depth of the follicle. Erythematous follicular papules and pustules develop on the chin, upper lip, and angle of the jaw, primarily in young black males. Papules may coalesce into plaques, and healing may occur with scarring. Affected individuals are frequently found to be S. aureus carriers. Treatment with warm saline compresses and topical antibiotics, such as mupirocin, generally clear the infection. More extensive, recalcitrant cases may require therapy with β-lactamase–resistant systemic antibiotics for several weeks, and elimination of S. aureus from the sites of carriage.

Pseudomonal folliculitis (hot tub folliculitis) is attributable to P. aeruginosa, predominantly serotype O-11. It occurs after exposure to poorly chlorinated hot tubs/whirlpools and swimming pools, as well as to a contaminated water slide, or loofah sponge. The lesions are pruritic papules and pustules or deeply erythematous to violaceous nodules that develop 8-48 hr after exposure and are most dense in areas covered by a bathing suit (Fig. 685.11 ). Patients occasionally experience fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. The organism is readily cultured from pus. The eruption usually resolves spontaneously in 1-2 wk, often leaving postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Consideration should be given to the use of systemic antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) in adolescent patients with constitutional symptoms. Immunocompromised children are susceptible to complications of Pseudomonas folliculitis (cellulitis) and should avoid hot tubs.

Abscesses and Furuncles

Etiology

The causative agent in furuncles (“boils”) and carbuncles is usually S. aureus, which penetrates abraded perifollicular skin. Conditions predisposing to furuncle formation include obesity, hyperhidrosis, maceration, friction, and preexisting dermatitis. Furunculosis is also more common in individuals with low serum iron levels, diabetes, malnutrition, HIV infection, or other immunodeficiency states. Recurrent furunculosis is frequently associated with carriage of S. aureus in the nares, axillae, or perineum, or close contact with someone such as a family member who is a carrier. Other bacteria or fungi may occasionally cause furuncles or carbuncles.

Community-acquired MRSA abscesses can also complicate folliculitis. Community-acquired MRSA infections commonly affect children and young adults, especially athletes where spread of the infection is enhanced by skin-to-skin contact. Infection can also be spread by crowding conditions, shared personal hygiene items, and a compromised skin barrier. They may occur in any location; however, they are most common on the lower abdomen, buttocks, and legs.

Clinical Manifestations

This follicular lesion may originate from a preceding folliculitis or may arise initially as a deep-seated, tender, erythematous, perifollicular nodule. Although lesions are initially indurated, central necrosis and suppuration follow, leading to rupture and discharge of a central core of necrotic tissue and destruction of the follicle (Fig. 685.12 ). Healing occurs with scar formation. Sites of predilection are the hair-bearing areas on the face, neck, axillae, buttocks, and groin. Pain may be intense if the lesion is situated in an area where the skin is relatively fixed, such as in the external auditory canal or over the nasal cartilages. Patients with furuncles usually have no constitutional symptoms; bacteremia may occasionally ensue. Rarely, lesions on the upper lip or cheek may lead to cavernous sinus thrombosis. Infection of a group of contiguous follicles, with multiple drainage points, accompanied by inflammatory changes in surrounding connective tissue is a carbuncle . Carbuncles may be accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, and bacteremia.

Treatment

Treatment for furuncle and carbuncle includes regular bathing with antimicrobial soaps (chlorhexidine) and wearing of loose-fitting clothing to minimize predisposing factors for furuncle formation. Frequent application of a hot, moist compress may facilitate the drainage of lesions. Large lesions should be drained by a small incision. Carbuncles and large or numerous furuncles should be treated with systemic antibiotics chosen based on culture and sensitivity testing results.

Abscesses are treated with incision and drainage and oral antibiotics (for 7-10 days). Antibiotics with coverage against MRSA are recommended and commonly include oral clindamycin (10-30 mg/kg/day in divided doses) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (8-12 mg trimethoprim/kg/day in divided doses every 12 hr). Children older than 8 yr may receive doxycycline. To reduce colonization and hence reinfection in children with recurrent infections, mupirocin intranasally (twice daily) and either chlorhexidine (in lieu of soap during showers) or diluted bleach baths [1 teaspoon per gallon of water or  cup per

cup per  tub (~13 gallons) of water] (once daily) for 5 days in patients and in family members has been recommended. Recolonization often occurs, typically within 3 mo of the decolonization attempt.

tub (~13 gallons) of water] (once daily) for 5 days in patients and in family members has been recommended. Recolonization often occurs, typically within 3 mo of the decolonization attempt.

Pitted Keratolysis

Pitted keratolysis occurs most frequently in humid tropical and subtropical climates, particularly in individuals whose feet are moist for prolonged periods, for example, as a result of hyperhidrosis, prolonged wearing of boots, or immersion in water. It occurs most commonly in young males from early adolescence to the late 20s. The lesions consist of 1-7 mm, irregularly shaped, superficial erosions of the horny layer on the soles, particularly at weight-bearing sites (Fig. 685.13 ). Brownish discoloration of involved areas may be apparent. A rare variant manifests as thinned, erythematous to violaceous plaques in addition to the typical pitted lesions. The condition is frequently malodorous and is painful in approximately 50% of cases. The most likely etiologic agent is Corynebacterium (Kytococcus) sedentarius. Treatment of hyperhidrosis is mandatory with prescription-strength aluminum chloride products or 40% formaldehyde in petrolatum ointment. Avoidance of moisture and maceration produces slow, spontaneous resolution of the infection. Topical or systemic erythromycin and topical imidazole creams are standard therapy.

Erythrasma

Erythrasma is a benign chronic superficial infection caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum. Predisposing factors include heat, humidity, obesity, skin maceration, diabetes mellitus, and poor hygiene. Approximately 20% of affected patients have involvement of the toe webs. Other frequently affected sites are moist, intertriginous areas such as the groin and axillae. The inframammary and perianal regions are occasionally involved. Sharply demarcated, irregularly bordered, slightly scaly, brownish red patches are characteristic of the disease. Mild pruritus is the only constant symptom. C. minutissimum is a complex of related organisms that produce porphyrins that fluoresce brilliant coral red under ultraviolet light. The diagnosis is readily made, and erythrasma is differentiated from dermatophyte infection and from tinea versicolor on Wood lamp examination. However, bathing within 20 hr of Wood lamp examination may remove the water-soluble porphyrins. Staining of skin scrapings with methylene blue or Gram stain reveals the pleomorphic, filamentous coccobacillary forms.

Effective treatment can be achieved with topical erythromycin, clindamycin, miconazole, or a 10-14 day course of oral erythromycin or an oral tetracycline (in those older than 8 yr of age).

Erysipeloid

A rare cutaneous infection, erysipeloid is caused by inoculation of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae from handling contaminated animals, birds, fish, or their products. The localized cutaneous form is most common, characterized by well-demarcated diamond-shaped erythematous to violaceous patches at sites of inoculation. Local symptoms are generally not severe, constitutional symptoms are rare, and the lesions resolve spontaneously after weeks but can recur at the same site or develop elsewhere weeks to months later. The diffuse cutaneous form manifests as lesions at several areas of the body in addition to the site of inoculation. It is also self-limited. The systemic form, caused by hematogenous spread, is accompanied by constitutional symptoms and may include endocarditis, septic arthritis, cerebral infarct and abscess, meningitis, and pulmonary effusion. Diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy, which reveals the Gram-positive organisms, and culture. The treatment of choice for localized cutaneous infection is oral penicillin for 7 days; ciprofloxacin or a combination of erythromycin and rifampin may be used for penicillin allergic patients. Severe diffuse cutaneous or systemic infection may require parenteral penicillin or ceftriaxone.

Tuberculosis of the Skin

See Chapters 242 and 244 .

Cutaneous tuberculosis infection occurs worldwide, particularly in association with HIV infection, malnutrition, and poor sanitary conditions. Primary cutaneous tuberculosis is rare in the United States. Cutaneous disease is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis, and, occasionally, by the bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), an attenuated vaccine form of M. bovis. The manifestations caused by a given organism are indistinguishable from one another. After invasion of the skin, mycobacteria either multiply intracellularly within macrophages, leading to progressive disease, or are controlled by the host immune reaction.

Primary cutaneous tuberculosis (tuberculous chancre) results when M. tuberculosis or M. bovis gains access to the skin or mucous membranes through trauma in a previously uninfected individual without immunity to the organism. Sites of predilection are the face, lower extremities, and genitals. The initial lesion develops 2-4 wk after introduction of the organism into the damaged tissue. A red-brown papule gradually enlarges to form a shallow, firm, sharply demarcated ulcer. Satellite abscesses may be present. Some lesions acquire a crust resembling impetigo, and others become heaped up and verrucous at the margins. The primary lesion can also manifest as a painless ulcer on the conjunctiva, gingiva, or palate and occasionally as a painless acute paronychia. Painless regional adenopathy may appear several weeks after the development of the primary lesion and may be accompanied by lymphangitis, lymphadenitis, or perforation of the skin surface, forming scrofuloderma . Untreated lesions heal with scarring within 12 mo but may reactivate, may form lupus vulgaris (sharply defined red-brown nodules with a gelatinous consistency that represent progressive infection), or, rarely, may progress to the acute miliary form. Therefore, antituberculous therapy is indicated (see Chapter 242 ).

M. tuberculosis or M. bovis can be cultured from the skin lesion and local lymph nodes, but acid-fast staining of histologic sections, particularly of a well-controlled infection, often does not reveal the organism. The differential diagnosis is broad, including a syphilitic chancre; deep fungal or atypical mycobacterial infection; leprosy; tularemia; cat-scratch disease; sporotrichosis; nocardiosis; leishmaniasis; reaction to foreign substances such as zirconium, beryllium, silk or nylon sutures, talc, and starch; papular acne rosacea; and lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei.

Scrofuloderma results from enlargement, cold abscess formation, and breakdown of a lymph node, most frequently in a cervical chain, with extension to the overlying skin from underlying foci of tuberculous infection. Linear or serpiginous ulcers and dissecting fistulas and subcutaneous tracts studded with soft nodules may develop. Spontaneous healing may take years, eventuating in cordlike keloid scars. Lupus vulgaris may also develop. Lesions may also originate from an underlying infected joint, tendon, bone, or epididymis. The differential diagnosis includes syphilitic gumma, deep fungal infections, actinomycosis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. The course is indolent, and constitutional symptoms are typically absent. Antituberculous therapy is indicated (see Chapter 242 ).

Direct cutaneous inoculation of the tubercle bacillus into a previously infected individual with a moderate to high degree of immunity initially produces a small papule with surrounding inflammation. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (warty tuberculosis) forms when the papule becomes hyperkeratotic and warty, and several adjacent papules coalesce or a single papule expands peripherally to form a brownish red to violaceous, exudative, crusted verrucous plaque. Irregular extension of the margins of the plaque produces a serpiginous border. Children have the lesions most commonly on the lower extremities after trauma and contact with infected material such as sputum or soil. Regional lymph nodes are involved only rarely. Spontaneous healing with atrophic scarring takes place over months to years. Healing is also gradual with antituberculous therapy.

Lupus vulgaris is a rare, chronic, progressive form of cutaneous tuberculosis that develops in individuals with a moderate to high degree of tuberculin sensitivity induced by previous infection. The incidence is greater in cool, moist climates, particularly in females. Lupus vulgaris develops as a result of direct extension from underlying joints or lymph nodes; through lymphatic or hematogenous spread; or, rarely, by cutaneous inoculation with the BCG vaccine. It most commonly follows cervical adenitis or pulmonary tuberculosis. Approximately 33% of cases are preceded by scrofuloderma, and 90% of cases manifest on the head and neck, most commonly on the nose or cheek. Involvement of the trunk is uncommon. A typical solitary lesion consists of a soft, brownish red papule that has an apple-jelly color when examined by diascopy. Peripheral expansion of the papule or, occasionally, the coalescence of several papules forms an irregular lesion of variable size and form. One or several lesions may develop, including nodules or plaques that are flat and serpiginous, hypertrophic and verrucous, or edematous in appearance. Spontaneous healing occurs centrally, and lesions characteristically reappear within the area of atrophy. Chronicity is characteristic, and persistence and progression of plaques over many years is common. Lymphadenitis is present in 40% of those with lupus vulgaris, and 10–20% has infection of the lungs, bones, or joints. Extensive deformities may be caused by vegetative masses and ulceration involving the nasal, buccal, or conjunctival mucosa; the palate; the gingiva; or the oropharynx. Squamous cell carcinoma, with a relatively high metastatic potential, may develop, usually after several years of the disease. After a temporary impairment in immunity, particularly after measles infection (lupus exanthematicus), multiple lesions may form at distant sites as a result of hematogenous spread from a latent focus of infection. The histopathology reveals a tuberculoid granuloma without caseation; organisms are extremely difficult to demonstrate. The differential diagnosis includes sarcoidosis, atypical mycobacterial infection, blastomycosis, chromoblastomycosis, actinomycosis, leishmaniasis, tertiary syphilis, leprosy, hypertrophic lichen planus, psoriasis, lupus erythematosus, lymphocytoma, and Bowen disease. Small lesions can be excised. Antituberculous drug therapy usually halts further spread and induces involution.

Orificial tuberculosis (tuberculosis cutis orificialis) appears on the mucous membranes and periorificial skin after autoinoculation of mycobacteria from sites of progressive infection. It is a sign of advanced internal disease and carries a poor prognosis, and it occurs in a sensitized host with impaired cellular immunity. Lesions appear as painful, yellowish or red nodules that form punched-out ulcers with inflammation and edema of the surrounding mucosa. Treatment consists of identification of the source of infection and initiation of antituberculous therapy.

Miliary tuberculosis (hematogenous primary tuberculosis) rarely manifests cutaneously and occurs most commonly in infants and in individuals who are immunosuppressed after chemotherapy or infection with measles or HIV. The eruption consists of crops of symmetrically distributed, minute, erythematous to purpuric macules, papules, or vesicles. The lesions may ulcerate, drain, crust, and form sinus tracts or may form subcutaneous gummas, especially in malnourished children with impaired immunity. Constitutional signs and symptoms are common, and a leukemoid reaction or aplastic anemia may develop. Tubercle bacilli are readily identified in an active lesion. A fulminant course should be anticipated, and aggressive antituberculous therapy is indicated.

Single or multiple metastatic tuberculous abscesses (tuberculous gummas ) may develop on the extremities and trunk by hematogenous spread from a primary focus of infection during a period of decreased immunity, particularly in malnourished and immunosuppressed children. The fluctuant, nontender, erythematous subcutaneous nodules may ulcerate and form fistulas.

Vaccination with BCG characteristically produces a papule approximately 2 wk after vaccination. The papule expands in size, typically ulcerates within 2-4 mo, and heals slowly with scarring. In 1-2 per million vaccinations, a complication caused specifically by the BCG organism occurs, including regional lymphadenitis, lupus vulgaris, scrofuloderma, and subcutaneous abscess formation.

Tuberculids are skin reactions that exhibit tuberculoid features histologically but do not contain detectable mycobacteria. The lesions appear in a host who usually has moderate to strong tuberculin reactivity, has a history of previous tuberculosis of other organs, and usually shows a therapeutic response to antituberculous therapy. The cause of tuberculids is poorly understood. Most affected patients are in good health with no clear focus of disease at the time of the eruption. The most commonly observed tuberculid is the papulonecrotic tuberculid. Recurrent crops of symmetrically distributed, asymptomatic, firm, sterile, dusky-red papules appear on the extensor aspects of the limbs, the dorsum of the hands and feet, and the buttocks. The papules may undergo central ulceration and eventually heal, leaving sharply delineated, circular, depressed scars. The duration of the eruption is variable, but it usually disappears promptly after treatment of the primary infection. Lichen scrofulosorum, another form of tuberculid, is characterized by asymptomatic, grouped, pinhead-sized, often follicular pink or red papules that form discoid plaques, mainly on the trunk. Healing occurs without scarring.

Atypical mycobacterial infection may cause cutaneous lesions in children. Mycobacterium marinum is found in saltwater, freshwater, and diseased fish. In the United States, it is most commonly acquired from tropical fish tanks and swimming pools. Traumatic abrasion of the skin serves as a portal of entry for the organism. Approximately 3 wk after inoculation, a single reddish papule develops and enlarges slowly to form a violaceous nodule or, occasionally, a warty plaque (Fig. 685.14 ). The lesion occasionally breaks down to form a crusted ulcer or a suppurating abscess. Sporotrichoid erythematous nodules along lymphatics may also suppurate and drain. Lesions are most common on the elbows, knees, and feet of swimmers, and on the hands and fingers in persons with aquarium-acquired infection. Systemic signs and symptoms are absent. Regional lymph nodes occasionally become slightly enlarged but do not break down. Rarely, the infection becomes disseminated, particularly in an immunosuppressed host. A biopsy specimen of a fully developed lesion demonstrates a granulomatous infiltrate with tuberculoid architecture. Treatment with 2 active agents is generally recommended with a combination of clarithromycin and ethambutol providing a reasonable balance between effectiveness and tolerability. Rifampin should be added to clarithromycin and ethambutol for deep tissue involvement. Other agents with activity against M. marinum include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, minocycline, and ciprofloxacin. While azithromycin has been used as an alternative to clarithromycin for some mycobacterial infections, its effectiveness against M. marinum is not known. Treatment should continue for 1-2 mo after resolution of lesions with a minimum treatment duration of 6 mo. The application of heat to the affected site may be a useful adjunctive therapy (see Chapter 244 ).

Mycobacterium kansasii primarily causes pulmonary disease; skin disease is rare, often occurring in an immunocompromised host. Most commonly, sporotrichoid nodules develop after inoculation of traumatized skin. Lesions may develop into ulcerated, crusted, or verrucous plaques. The organism is relatively sensitive to antituberculous medications, which should be chosen on the basis of susceptibility testing.

Mycobacterium scrofulaceum causes cervical lymphadenitis (scrofuloderma) in young children, typically in the submandibular region. Nodes enlarge over several weeks, ulcerate, and drain. The local reaction is nontender and circumscribed, constitutional symptoms are absent, and there generally is no evidence of lung or other organ involvement. Other atypical mycobacteria may cause a similar presentation, including Mycobacterium avium complex, Mycobacterium kansasii, and Mycobacterium fortuitum. Treatment is accomplished by excision and administration of antituberculous drugs (see Chapter 244 ).

Mycobacterium ulcerans (Buruli ulcer) causes a painless subcutaneous nodule after inoculation of abraded skin. Most infections occur in children in tropical rain forests. The nodule usually ulcerates, develops undermined edges, and may spread over large areas, most commonly on an extremity. Local necrosis of subcutaneous fat, producing a septal panniculitis, is characteristic. Ulcers persist for months to years before healing spontaneously with scarring, sometimes with contractures (if over a joint) and lymphedema. Constitutional symptoms and lymphadenopathy are absent. Diagnosis is made by culturing the organism at 32-33°C (89.6-91.4°F). Treatment of choice is an 8-wk course of rifampin and streptomycin with surgical debridement for larger lesions. Local heat therapy and oral chemotherapy may benefit some patients.

M. avium complex, composed of more than 20 subtypes, most commonly causes chronic pulmonary infection. Cervical lymphadenitis and osteomyelitis occur occasionally, and papules or purulent leg ulcers occur rarely by primary inoculation. Skin lesions may be an early sign of disseminated infection. The lesions may take various forms, including erythematous papules, pustules, nodules, abscesses, ulcers, panniculitis, and sporotrichoid spread along lymphatics. For treatment, see Chapter 244 .

M. fortuitum complex causes disease in an immunocompetent host principally by primary cutaneous inoculation after traumatic injury, injection, or surgery. A nodule, abscess, or cellulitis develops 4-6 wk after inoculation. In an immunocompromised host, numerous subcutaneous nodules may form, break down, and drain. Treatment is based on identification and susceptibility testing of the organism. Isolates are usually susceptible to fluoroquinolones, doxycycline, minocycline, sulfonamides, cefoxitin, and imipenem; macrolides should be used with caution because many M. fortuitum isolates have the erythromycin methylase (erm) gene, which confers inducible resistance to macrolides despite “susceptible” minimum inhibitory concentrations.

Bibliography

Blaise G, Nikkels AF, Hermanns-Le T, et al. Corynebacterium -associated skin infections. Int J Dermatol . 2008;47:884–890.

Boyd AS, Ritchie C, Fenton JS. Cutaneous Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae (erysipeloid) infection in an immunocompromised child. Pediatr Dermatol . 2014;31(2):232–235.

Bradley J, Glasser C, Patino H, et al. Daptomycin for complicated skin infections: a randomized trial. Pediatrics . 2017;139(3):e20162477.

Daum RS, Miller LG, Immergluck L, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of antibiotics for smaller skin abscesses. N Engl J Med . 2017;376(26):2545–2554.

Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculosis mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin . 2015;33(3):563–577.

Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastcomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin . 2015;33(3):595–607.

Holmes L, Ma C, Qiao H, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy reduces failure and recurrence in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin abscesses after surgical drainage. J Pediatr . 2016;169:128–134.

Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection . 2015 Dec;43(6):655–662; 10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8 [Epub 2015 Apr 14].

McClain SL, Bohan JG, Stevens DL. Advances in the medical management of skin and soft tissue infections. BMJ . 2016;355:i6004.

Meury SN, Erb T, Schaad UB, et al. Randomized, comparative efficacy trial of oral penicillin versus cefuroxime for perianal streptococcal dermatitis. J Pediatr . 2008;153:799–802.

Miller LG, Daum RS, Creech CB, et al. Clindamycin versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for uncomplicated skin infections. N Engl J Med . 2015;372(12):1093–1102.

Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Mower WR, et al. Effect of cephalexin plus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole vs cephalexin alone on clinical cure of uncomplicated cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2017;317(20):2088–2096.

Obaitan I, Dwyer R, Lipworth AD, et al. Failure of antibiotics in cellulitis trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med . 2016;34(8):1645–1652.

Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: a review. JAMA . 2016;316(3):325–336.

Rentala M, Andrews S, Tiberio A, et al. Intravenous home infusion therapy instituted from a 24-hour clinical decision unit for patients with cellulitis. Am J Emerg Med . 2016;34(7):1273–1275.

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis . 2014;59(2):e10–e52.

Sethuraman G, Ramesh V. Cutaneous tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Dermatol . 2013;30(1):7–16.

Talan DA, Mower WR, Krishnadasan A, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus placebo for uncomplicated skin abscess. N Engl J Med . 2016;374(9):823–832.

Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol . 2017;153(2):141–146.