The sounds of music seem to be everywhere in our twenty-first-century world. We hear everything from classic to pop, jazz to the world's many musical traditions, and fusions of all kinds. Being able to experience music of diverse genres and cultures has never been easier! Given technological developments and electronic media, not to mention social and education reforms, it is no surprise that the wide, wide world of music is open to all of us.

The elementary music curriculum should reflect this diversity and include the wealth of childhood songs of many traditions as well as classical music, music of many different cultures, the uniquely American music jazz, and popular music. Children need to open their ears to the entire world of music as they expand their musical skills and understanding. In fact, "research suggests that inclusion of more styles of music, including popular music and music from various cultures, will increase student participation and creativity" (College Board, 2011: 25).

What follows is specific information about classical music, world music, jazz, and popular music; their place in the elementary curriculum; and some suggestions and examples for instructional approaches.

Classical music is a term for art music of the Western civilization, usually created by a trained composer. Western art music is the music of Bach (1685–1750) and Beethoven (1770–1827), or of Clara Schumann (1819–1896) and Ellen Taaffe Zwilich (b. 1939), and certainly should be an important part of the school curriculum. Many model experiences in this text make use of Western art music, e.g., the music of Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Gabrieli, and Stravinsky. To have a frame of reference for the timeline of Western art music, the chart that follows identifies the historical musical style periods, with approximate dates and a small sampling of composers from each period.

Some children may have had very little exposure to classical music in their preschool years. Therefore, introducing them to the beauty and excitement of Western art music in their elementary school years can open the door to a lifetime of musical

Table 4.1 Western art music timeline

| Style Periods |

Approximate Dates |

Selected Composers |

|

| Medieval |

500-1420 |

Leonin, Hildegard, Machaut |

| Renaissance |

1420-1600 |

Palestrina, Gabrieli, Monteverdi |

| Baroque |

1600-1750 |

Bach, Vivaldi, Handel |

| Classic |

1750-1820 |

Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven |

| Romantic |

1820-1900 |

Schumann, Chopin, Tchaikovsky |

| Modern |

1900-1975 |

Schoenberg, Ravel, Stravinsky |

| Contemporary |

1975-present |

Glass, Reich, Zwilich |

enjoyment! Having a teacher who is not only knowledgeable, but also enthusiastic, and shows his or her own enjoyment of the music helps children appreciate and enjoy the musical experience even more.

The musical experiences in this text are designed to engage children actively in the listening experience and turn them on to classical music. In general, the Level I and II lessons use shorter, "brighter" instrumental pieces with a variety of dynamic levels, driving rhythm, and melodic repeats. For example, "Chinese Dance"  from The Nutcracker Suite (Tchaikovsky) is presented in Model 19 to introduce students to alternating high-pitched and low-pitched phrases while Model 25 engages children in performing beat groupings of three while listening to Bach's "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring."

from The Nutcracker Suite (Tchaikovsky) is presented in Model 19 to introduce students to alternating high-pitched and low-pitched phrases while Model 25 engages children in performing beat groupings of three while listening to Bach's "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring."

More complex compositions are included in Level III. Each model experience focuses on the elements of music, and a student's attention is specifically directed to a music element such as melody, timbre, or form. For example, Models 33 and 34 focus on sectional form engaging students in discovering that the piece "Carillon"  by Bizet is in ABA form while the "Viennese Musical Clock"

by Bizet is in ABA form while the "Viennese Musical Clock"  by Kodály is in rondo form. The same approach or a similar one to The Musical Classroom's is used in lessons presenting classical pieces in the elementary music series print and online materials (see Appendix D). Many of the planning steps and ideas presented in Chapter 3, "Listening," work especially well with presenting classical music.

by Kodály is in rondo form. The same approach or a similar one to The Musical Classroom's is used in lessons presenting classical pieces in the elementary music series print and online materials (see Appendix D). Many of the planning steps and ideas presented in Chapter 3, "Listening," work especially well with presenting classical music.

Other approaches introduce classical music by playing recordings (without specific conceptual goals) during snack or naptime, artwork, or movement, or have students create mental images while listening. Children are often fascinated by stories about the famous composers and there are numerous children's books available to peak their interest (see Appendix E). September is Classical Music Month and a great time for orchestras in major cities to offer special events. Many orchestras have a dedicated interactive website for children and regularly offer concerts for school groups. Check out the websites for the San Francisco Symphony, Dallas Symphony, and the New York Philharmonic (Appendix E). Teachers and musicians throughout the United States are working together to bring more children (and adults) in touch with classical music.

There is an astonishing variety of music in every part of the globe. Those who study music and its place in culture (ethnomusicologists) have shown us that there is no universal language of music but a multiplicity of musical languages. Each expresses the aesthetic principles of its culture. Each has a history and a repertoire of pieces; each has its own special approach to composition, performance, and use of instruments. Each preserves its tradition for future generations—even though styles are changing and mixing continuously (acculturation).

Introducing the music of different cultures to our children is a must! Not only do they need to understand that the classical tradition is just one of the musical languages that exists, but they should experience and learn about the glorious sounds coming to them from around the world. Given the culturally diverse society that we live in, children are learning from their classmates and friends about the special holidays, celebrations, and customs of many different cultures. It is only natural that they should also experience and learn about the musical traditions of selected cultures and open their ears (and minds) to the many, many enchanting world musics.

Figure 4.1 Malaysian boys in traditional dress playing the kompang.

Photo by Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia/ISME 2006.

The multicultural music curriculum can have both musical and nonmusical goals. The nonmusical goals of a music curriculum are similar to social science goals. Both share humanistic goals to promote self-awareness and self-esteem, build empathy for others, and encourage respect for the dignity of all human beings. In exploring world music, children also (ideally) explore a people's customs, history, geography, and beliefs; combining music with social studies enriches both subjects. Such experiences align with social and global rationales for including world music in schools (Fung, 1995).

Musical goals of the multicultural music curriculum are to help children learn about the language of music. Teachers can implement musical goals by focusing on music concepts, performance, and listening. Musical goals are the basis for the model experiences in Section II of this text. Practical applications of integrated learning (e.g., social studies, dance) are presented and highlighted in activities that follow the model experiences. Integrated learning is also presented in Chapter 6, along with practical applications from model experiences.

What follows are some examples of model experiences that focus on selected world cultures. As with all models in this text, music concepts serve as the focus for music-learning experiences. For example, a music concept is explored in Model 37 "Corn Grinding Song"  in which students focus on a Navajo melody that moves high and low, and repeats. This is expanded to concepts about vocal timbre and rhythm, suggested in an extension activity, and students notice details such as pulsation in the singer's voice. They are also encouraged to learn more about the Navajos in suggested books for young readers.

in which students focus on a Navajo melody that moves high and low, and repeats. This is expanded to concepts about vocal timbre and rhythm, suggested in an extension activity, and students notice details such as pulsation in the singer's voice. They are also encouraged to learn more about the Navajos in suggested books for young readers.

Focused listening is necessary when students explore vibrating objects and identify the timbre (tone color) of two different African instruments from Nigeria and Uganda in Model 13. They learn about the importance of drumming in African music and the special features of a kalimba/mbira/sansa (thumb pianos). Most importantly, they discover a wider palette of musical sounds.

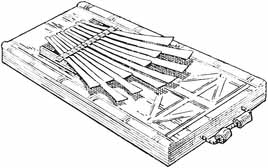

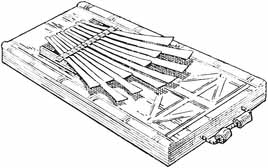

Figure 4.2 Thumb “piano,” kalimba, mbira or sansa.

Even a larger palette is explored in a listening experience in Model 38 in which music of North Africa, Vietnam, and Bali is introduced as students identify instruments by their vibrating material and sound in a classification system used by ethnomusicologists and organologists (see below.) Extensions to Model 38 include planning a world music week featuring cultures in the local community. In Level III, fourth and fifth graders can explore a multicultural unit featuring four model experiences (Models 35, 36, 37 and 38).

Table 4.2 Classification system for instruments of the world

| Aerophones |

(Aero means "air" and phone means "sound" from Greek and Latin roots) are instruments in which the sound-producing agent is a vibrating column of air. Examples are flutes, trumpets, oboes, and recorders. |

| Chordophones |

(Chord means "rope or string") are instruments that produce their sound by setting up vibrations in a stretched string. Examples are ukuleles, sitars, violins, and guitars. |

| Electrophones |

(Electro means "electric") are instruments that produce vibrations that must be passed through a loudspeaker before they are heard as sound. Examples are electric guitar and electric bass. |

| Idiophones |

(Ideo means "personal" or "self") are instruments in which the sound-producing agent is a solid material capable of producing sound by setting up vibrations in the substance of the instrument, such as wood or metal. Examples are gongs, chimes, and xylophones. |

| Membranophones |

(Membran means "skin") are instruments in which sound is produced by vibrations in a stretched membrane (skin). Examples are mainly drums. |

Integrated learning incorporates cultural traditions into the music-learning experience, and is not developed around a music concept. Though a music concept may not be the focus, music performance will be included, and music concepts can be introduced as appropriate. Cultural topics for children in elementary grades would include some of the following: the people, their land, language, education, ways of making a living, customs, courtesies, music, recreation, holidays, and even food! For example, in an extension to Model 32 "Haiku Sound Piece," students create the environment of a Japanese home, and also learn about culture, customs, and music. Well-planned integrated learning experiences also can meet musical goals in the curriculum.

Resources for the Multicultural Music Curriculum

Ethnic musicians (and parents) in the community are a valuable resource, and they often are delighted to perform for students and introduce their culture. Culturally authentic materials of the highest quality are readily available to use in the elementary classroom. The elementary music series publications and their online materials offer all kinds of music from around the world, performed by standard-bearers of the cultural traditions, with indigenous language and instruments (see Appendix D). Numerous websites, books, recordings, etc., exist to offer musical avenues for exploring music of specific cultures (see Appendix D). The Smithsonian Folkways recordings are particularly excellent and offer a wealth of music from around the world (www.folkways.si.edu). A helpful "Checklist for Evaluating Multicultural Materials" is available on the World Music Press website (www.worldmusicpress.com). Instruments from a wide variety of ethnic groups can be purchased from a number of sources (see Appendix D, "Music Suppliers"). And the Musical Instrument Museum (www.mim.org) is a valuable resource for instruments (and music) from around the world.

Figure 4.3 An exhibit featuring the country of Nigeria including instruments, audio, video, and costumes associated with the masquerades’ tradition of the Yoruba people.

Courtesy of Musical Instrument Museum.

For examples of selected ethnic celebrations that occur throughout the year, see the chart below and the Monthly Planners in Section II.

Table 4.3 Selected ethnic celebrations

| January |

Martin Luther King Jr. Day (3rd Monday), Chinese New Year (China, Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, variable) |

| February |

African American History Month, Chinese New Year (variable) |

| March |

Irish American Heritage Month, Greek American Heritage Month |

| May |

Asian and Pacific American Heritage Month, Lei Day (Hawaii, May 1), Cinco de Mayo (May 5), Jewish American Heritage Month |

| June |

Caribbean American Heritage Month |

| August |

Bon Festival (Japan) |

| September |

Hispanic Heritage Month |

| October |

Italian American Heritage and Culture Month |

| November |

National American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month, Chinese and Vietnamese Moon Festivals |

African Americans created jazz, one of America's original art forms. Blues and ragtime music of the late 1800s were influential in the development of traditional (or Dixieland) jazz at the beginning of the twentieth century in New Orleans. Two main musical features of jazz are syncopation (putting accents in unexpected places) and improvisation (creating music spontaneously).

After more than a century of development, jazz is celebrated as an important art form in the United States. In fact, the U.S. Congress passed legislation in 2003 declaring April to be "Jazz Appreciation Month," or JAM. (Even the acronym refers to jazz—improvisation in a jam session!) Congress further noted that Americans should "explore, perpetuate, and honor jazz as a national and world treasure."

Some major jazz styles and performers of jazz are identified below. Keep in mind that dates shown are approximate, new styles do not necessarily extinguish earlier ones, and most styles continue to be popular today.

Table 4.4 Jazz styles and performers

| Styles |

Approximate Dates |

Performers |

|

| Traditional (or Dixieland) |

early 1900s |

Joe "King" Oliver |

| Chicago Style |

1920s |

Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke |

| Swing, Big Band |

mid-1930s-mid-1940s |

Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Mary Lou Williams |

| Bebop |

1940s-1950s |

Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie |

| Cool |

1950s-1960s |

Dave Brubeck, Miles Davis |

| Fusion |

1970s |

Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock |

| Current |

present |

Wynton Marsalis, Joshua Redman |

Elementary school children should have experiences with this exciting, distinctive American creation. Jazz can be explored through its musical elements (e.g., melody, rhythm, and form) and through singing, playing instruments, movement, listening, and creating. In this text, two early forms of jazz—the 12-bar blues and boogie-woogie—are presented. Fourth and fifth graders discover the three phrases in the 12-bar blues form of "Lost Your Head Blues"  (Model 40), while kindergarteners and first graders explore the fast and slow tempi of "Boogie-Woogie Walk"

(Model 40), while kindergarteners and first graders explore the fast and slow tempi of "Boogie-Woogie Walk"  (Model 5). Ragtime music, another influence on jazz, is the focus in Model 41 "Piffle Rag."

(Model 5). Ragtime music, another influence on jazz, is the focus in Model 41 "Piffle Rag."  Sections of this rag may be accompanied by improvised movements that repeat in accordance with the phrases and sections of the rag. In Model 42 "Take Five," the Dave Brubeck Quartet's "cool jazz" composition, students are challenged to perform the five-beat groupings (meter) using body movements.

Sections of this rag may be accompanied by improvised movements that repeat in accordance with the phrases and sections of the rag. In Model 42 "Take Five," the Dave Brubeck Quartet's "cool jazz" composition, students are challenged to perform the five-beat groupings (meter) using body movements.

Models 40, 41, and 42 can serve as the basis for a jazz unit for fourth and fifth graders. In addition, jazz pieces are listed in the "Other Music" suggestions of the model experiences throughout Section II.

Resources for Jazz

Some examples of jazz are included in the elementary music series books and their online materials (see Appendix D). Specific publications have been released to help teachers introduce jazz to children. Chop-Monster Jr. is a jazz handbook that helps elementary teachers discover and explore jazz performance techniques with children. The Jazz for Young People™ Curriculum provides a wealth of teacher and student materials for jazz appreciation. The Smithsonian Institution has produced a fine series of online lessons on jazz for young people, ages 8 to 15, called Groovin' to Jazz. In Appendix E, you will find a list of the many available children's books about jazz performers.

Popular music includes rock, soul, country/bluegrass, rap, Broadway musicals, and many other genres. Often popular music is the choice of students outside of school today. For many years, music educators avoided introducing popular music in the classroom—mainly questioning its musical merit. However, when suitable materials are available, popular music can be presented in a way that has musical integrity—and not just as a social or psychological support for students (Cutietta, 1991: 27).

This means that instruction should be standards-based and focused on the elements of music (e.g., melody, harmony, rhythm, form) and on the special sound (expressive quality) of pop instruments. From this perspective, popular music can be integrated into the curriculum on the same basis as classical music, world music, and jazz.

The challenge is being able to include popular music in instructional materials for the classroom. Copyright fees are extremely expensive, lyrics may not be appropriate, currently popular songs may have a very short "shelf life," and the list goes on. In fact, these are the same reasons that popular music is not included in this text. A bluegrass example is part of Model 39 and follow-ups to models often suggest online searches for popular music illustrating a particular concept. Some popular music is nominally represented in the elementary music series books and online materials—usually older pop songs and Broadway show tunes, but few rock or Top 40 songs.

Imaginative teachers can find ingenious ways to bring popular music into the classroom. For example, by finding out what students are listening to outside of school and asking them to download and share with you (on their electronic device), the suitability of lyrics, etc., can be checked. Also, assignments can be given for finding a popular song that illustrates one of the music concepts that they have been studying in class. Teachers can also explore how popular music techniques can enhance a classroom song students know by adding dance movements, changing the dynamics, or creating "iffs" ostinatos) on different instruments.

Projects

- Search the Internet for information about the music of a selected culture. Prepare a presentation using PowerPoint or similar presentation software to share what you have learned.

- Visit the Musical Instrument Museum's website (www.mim.org) and review the education section for information about instruments of various cultures. Summarize and share the educator resources that can be helpful for elementary teachers.

- Check out teaching videos on YouTube that engage children in music of other cultures, classical music, jazz or popular music.

References

College Board. (December 2011). Child Development and Arts Education: A Review of Current Research and Best Practices. New York: The College Board. www.advocacy.collegeboard.org/preparation-access/arts-core.

Cutietta, R.A. (1991). "Popular Music: An Ongoing Challenge." Music Educators Journal 77(8): 26-29.

Fitzgerald, M., McCord, K., and Berg, S. (2003). Chop-Monster Jr. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred Publications, Inc.

Fung, C.V. (July 1995). "Rationales for Teaching World Musics." Music Educators Journal 82(2): 36-40.

Marsalis, W. (2002). Jazz for Young People Curriculum. Miami: Warner Bros.

Smithsonian Institution (2004). Groovin' to Jazz. www.americanhistory.si.edu/Smithsonian-jazz/education/grooving-jazz-ages-8-13.

from The Nutcracker Suite (Tchaikovsky) is presented in Model 19 to introduce students to alternating high-pitched and low-pitched phrases while Model 25 engages children in performing beat groupings of three while listening to Bach's "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring."

from The Nutcracker Suite (Tchaikovsky) is presented in Model 19 to introduce students to alternating high-pitched and low-pitched phrases while Model 25 engages children in performing beat groupings of three while listening to Bach's "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring."

by Bizet is in ABA form while the "Viennese Musical Clock"

by Bizet is in ABA form while the "Viennese Musical Clock"  by Kodály is in rondo form. The same approach or a similar one to

by Kodály is in rondo form. The same approach or a similar one to

in which students focus on a Navajo melody that moves high and low, and repeats. This is expanded to concepts about vocal timbre and rhythm, suggested in an extension activity, and students notice details such as pulsation in the singer's voice. They are also encouraged to learn more about the Navajos in suggested books for young readers.

in which students focus on a Navajo melody that moves high and low, and repeats. This is expanded to concepts about vocal timbre and rhythm, suggested in an extension activity, and students notice details such as pulsation in the singer's voice. They are also encouraged to learn more about the Navajos in suggested books for young readers.

(Model 40), while kindergarteners and first graders explore the fast and slow tempi of "Boogie-Woogie Walk"

(Model 40), while kindergarteners and first graders explore the fast and slow tempi of "Boogie-Woogie Walk"  (Model 5). Ragtime music, another influence on jazz, is the focus in Model 41 "Piffle Rag."

(Model 5). Ragtime music, another influence on jazz, is the focus in Model 41 "Piffle Rag."  Sections of this rag may be accompanied by improvised movements that repeat in accordance with the phrases and sections of the rag. In Model 42 "Take Five," the Dave Brubeck Quartet's "cool jazz" composition, students are challenged to perform the five-beat groupings (meter) using body movements.

Sections of this rag may be accompanied by improvised movements that repeat in accordance with the phrases and sections of the rag. In Model 42 "Take Five," the Dave Brubeck Quartet's "cool jazz" composition, students are challenged to perform the five-beat groupings (meter) using body movements.