The Two Noble Kinsmen

This bitter-sweet tragicomedy of love and death, co-written with John *Fletcher, includes what was almost certainly Shakespeare’s last writing for the stage. Excluded from the *Folio, presumably because of its collaborative authorship, the play was not published until 1634: both the *Stationers’ Register entry and the quarto’s title page attribute it to ‘William Shakespeare and John Fletcher’. The play borrows its *morris dance (3.5) from Francis *Beaumont’s Masque of the Inner Temple and Gray’s Inn (February 1613), while its prologue’s reference to ‘our losses’ almost certainly alludes to the burning down of the *Globe (June 1613). Probably composed during 1613–14, The Two Noble Kinsmen may well have been the first play to appear at the rebuilt Globe on its opening in 1614: certainly two sarcastic allusions to ‘Palamon’ in Ben *Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair (premièred in October 1614) suggest that Jonson expected this play to be fresh in his spectators’ minds.

Text: The 1634 quarto provides the only substantive text of The Two Noble Kinsmen, and its various inconsistencies—including variant spellings, such as ‘Perithous’ and ‘Pirithous’, ‘Ialor’ and ‘Iaylor’—suggest that it was set from *foul papers in the hands of both playwrights, though these had probably been annotated with reference to later performances (some stage directions, for example, accidentally mention the actors Curtis Greville and Thomas Tuckfield, who were both members of the King’s Company only between 1625 and mid-1626). The general scholarly consensus, based on variant spellings in the text and, especially, considerations of style, metre, and vocabulary, is that Shakespeare wrote Act 1, 2.1, 3.1–2, and most of Act 5 (excluding 5.4), and Fletcher the rest (including the Prologue and Epilogue). Although both playwrights presumably agreed on the overall structure of the play, it appears from minor discrepancies between their respective shares that they wrote independently of one another, Shakespeare concentrating on the Theseus frame-narrative and the establishment and closure of the Palamon–Arcite plot, Fletcher on the intervening rivalry between Palamon and Arcite and the sub-plot of the Jailer’s Daughter.

Sources: The play is primarily a dramatization of Geoffrey *Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale, the first and one of the most highly regarded of The Canterbury Tales: this well-known work had already been dramatized at least twice, once by Richard Edwards as Palaemon and Arcyte (performed before Queen Elizabeth at Christ Church, Oxford, in 1566, but never printed) and once as another lost play with the same title, acted in 1594. Surviving eyewitness accounts of Edwards’s play suggest that Shakespeare and Fletcher may have remembered it at some points (their Palamon, for example, recalls at 5.6.44–5 that he has said Venus is false: in fact he has not done so, though his counterpart in Edwards’s play did). Shakespeare and Fletcher may also have known Chaucer’s source, *Boccaccio’s Teseida (in which Arcite’s horse falls backwards onto him, as in the play, rather than pitching him off forwards as in Chaucer). Their chief alterations to Chaucer are the addition of the three queens and their interruption to Theseus’ wedding procession (itself influenced by Shakespeare’s earlier treatment of Theseus’ wedding preparations in A Midsummer Night’s Dream), the stipulation that the loser of the Palamon–Arcite duel must die, and the added sub-plot of the Jailer’s Daughter. This sub-plot itself recalls earlier motifs in the Shakespeare canon: most obviously her madness recalls Ophelia and Desdemona’s remembered maid Barbara, but her position as lovestruck helper of her father’s prisoner (and her obsession with storms at sea) also recalls Miranda’s role in The Tempest 3.1.

Synopsis: A prologue, comparing new plays to maidenhoods, boasts that this one derives from Chaucer and ought to please.

1.1 Preceded by a boy who sings an epithalamium, ‘Roses, their sharp spines being gone’, Theseus and his bride Hippolyta pass towards their wedding, accompanied by Theseus’ comrade Pirithous and sister Emilia: they are stopped, however, by three mourning queens, whose husbands, killed fighting against the evil Creon of Thebes, have been denied burial. Their kneeling plea that Theseus should postpone his wedding until he has defeated Creon is seconded by Hippolyta and Emilia, and Theseus complies.

1.2 In Thebes, the inseparable cousins Palamon and Arcite, though anxious about the vicious state of their uncle Creon’s regime, prepare to fight against Theseus.

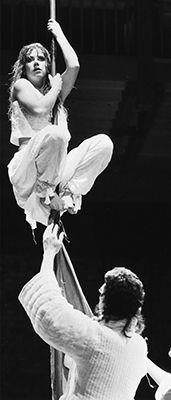

Imogen Stubbs as the Jailer’s Daughter in Barry Kyle’s production of The Two Noble Kinsmen which opened the RSC’s new Swan theatre in Stratford, 1986.

1.3 Pirithous parts from Hippolyta and Emilia in order to rejoin Theseus. The women discuss the rival claims of same-sex friendship and love, Emilia tenderly remembering her dead friend Flavina.

1.4 The three queens bless Theseus for defeating Creon. Seeing the wounded and unconscious Palamon and Arcite, who have fought nobly, he orders they should be tended but kept prisoner.

1.5 The three queens process towards the separate funerals of their husbands to the dirge ‘Urns and odours, bring away’, and bid one another a solemn farewell.

2.1 A wooer talks with the Jailer about his projected marriage to the Jailer’s Daughter, who speaks enthusiastically about the prisoners Palamon and Arcite.

2.2 Palamon and Arcite are consoling one another for their lost liberty with promises of eternal friendship when Palamon sees Emilia from the window, gathering flowers with her woman in the garden beneath. He falls in love with her, as does Arcite, and the two immediately quarrel as rivals for her. The Jailer takes Arcite away, released by Theseus but banished to Thebes, and takes Palamon to a cell with no view of the garden.

2.3 Arcite resolves to disguise himself so that he may remain near Emilia: learning from some countrymen of a sporting contest before Theseus, he decides to compete in it.

2.4 The Jailer’s Daughter, in love with Palamon, decides to arrange his escape in the hope of earning his love.

2.5 The disguised Arcite is victor in the wrestling before Theseus, and Pirithous makes him master of horse to Emilia.

2.6 The Jailer’s Daughter has freed Palamon and is about to run away from her father’s house to meet him in the woods with food and a file to remove his manacles.

3.1 Arcite, who has followed Theseus, Emilia, and their party into the woods on their May morning hunt, is reflecting on how Palamon would envy him his position when Palamon, overhearing him, emerges from a bush. They agree that Arcite will fetch food and a file, and duel with Palamon when he has recovered his strength.

3.2 Sleepless and hungry, the Jailer’s Daughter has failed to find Palamon, who she imagines has been eaten by wolves: full of self-reproach, she is beginning to lose her wits.

3.3 Arcite brings Palamon food: as he eats, the rivals reminisce about each other’s past loves.

3.4 The Jailer’s Daughter, mad, imagines a shipwreck.

3.5 Gerald the schoolmaster is rehearsing five countrymen, five countrywomen, and a taborer in the morris dance they are to perform before Theseus when they realize they are a woman short: however, they recruit the mad Jailer’s Daughter, and when Theseus and his party arrive they perform their elaborate dance, prefaced by Gerald’s rhyming oration, as planned.

3.6 Arcite brings Palamon sword and armour: they arm each other carefully, but their duel is interrupted by the arrival of Theseus, Hippolyta, Emilia, and Pirithous. Learning of their identities and purposes, Theseus sentences both to death, but they are reprieved at the suit of Hippolyta and Emilia. However, they refuse Emilia’s offer of peaceable banishment, refusing to renounce their quarrel over her, and when Emilia will not choose between them Theseus finally agrees that their mortal duel must resume. In a month’s time each is to return with three knights: the winner of the contest will marry Emilia, the loser will be executed along with his three seconds.

4.1 The Jailer is relieved to learn that Palamon has cleared him of treason by explaining that it was his daughter who let him out of prison, but the Wooer brings the news of the Jailer’s Daughter’s madness, narrating how he found her wandering and singing and had to rescue her from drowning in a lake. She arrives herself with the Jailer’s Brother, full of mad tales of Palamon’s potency, and imagines sailing a ship to find Palamon in the woods: they do what they can to humour her.

4.2 Emilia, studying portraits of Arcite and of Palamon, is still unable to prefer one to the other. Theseus and Pirithous speak admiringly of the knights with whom the two rivals have returned to fight for Emilia.

4.3 A doctor, summoned by the Jailer and the Wooer, interviews the Jailer’s Daughter, and prescribes that the Wooer should pretend to be Palamon.

5.1 Palamon and Arcite, accompanied by their seconds, bid a solemn farewell. Arcite prays at the altar of Mars for success in the combat, and is encouraged by a sound of thunder and arms.

5.2 Palamon prays at the altar of Venus for success in his quest for Emilia, and is encouraged by music and fluttering doves.

5.3 Emilia prays at the altar of Diana that if she is not to remain a maid she should be won by the contender who loves her best or has the truest title to her. A rose falls from the tree on the altar.

5.4 Despite the Jailer’s misgivings, the Wooer, impersonating Palamon, takes the Doctor’s advice to lead the Jailer’s Daughter away to bed.

5.5 Emilia cannot bear to watch the combat, but hears its progress by offstage shouts and the reports of a servant: Palamon almost wins, but is defeated by Arcite. The victorious Arcite is presented to her by Theseus, who speaks regretfully of the doomed Palamon’s valour.

5.6 Palamon and his three knights are about to be executed: Palamon bequeathes the Jailer his money as a wedding portion for his daughter. Pirithous arrives just in time to halt the execution, reporting that in the midst of his triumphal entry into Athens Arcite has been fatally injured, his horse rearing up and falling backwards onto him. Theseus, Hippolyta, and Emilia return, with the dying Arcite carried in a chair. Arcite bequeathes Emilia to Palamon. Theseus reflects on the ambiguous justice with which the gods have fulfilled their omens, and on humanity’s restless impatience with what it has in favour of desire for what it lacks. An epilogue wonders anxiously how the audience have liked the play, assuring them it was intended only to please.

Artistic features: Shakespeare’s sections of the play share their densely figured, knotty syntax and imagery with his other late romances, and display a similar interest in spectacularly rendered ritual. The play’s stagecraft suggests it was composed with the *Blackfriars theatre in mind, and as a large-cast play with a classical-cum-medieval setting which makes extensive use of music it has much in common with other plays in the King’s Company’s Jacobean repertoire, not only Pericles but Thomas *Heywood’s The Golden Age, The Silver Age, and The Brazen Age.

Critical history: Although some 19th-century critics accepted the quarto’s attribution, The Two Noble Kinsmen was generally accepted into the Shakespeare canon only in the 20th century, and much critical writing about it continues to be preoccupied with the question of its authorship. Its restoration to the Shakespeare corpus, however, coincided with *modernism’s high valuation for the complexities of Shakespeare’s later style and with the ritual elements of drama. It coincided, too, with a *Freudian interest in the representation of *sexuality, and in recent years the Jailer’s Daughter’s ‘green-sickness’ and the controversial therapy applied to it have attracted a good deal of attention, as has the juxtaposition between the kinsmen’s homosocial rivalry and the near-lesbianism of Emilia’s passionate championing of female friendship.

Stage history: The play reappeared after the Restoration as *Davenant’s cheerful adaptation *The Rivals (1664), its action transferred to a harmless Arcadia in which Celania (the Jailer’s Daughter) marries Philander (Palamon) and Arcite survives to marry Heraclia (Emilia). This version influenced two later 18th-century rewritings, the much darker Palamon and Arcite; or, The Two Noble Kinsmen by Richard Cumberland (1779), and a musical, Midsummer Night’s Dream-like version by F. G. Waldron, Love and Madness; or, The Two Noble Kinsmen (1795). The play was not revived professionally again until an *Old Vic production in 1928, designed to suggest a pretty homage to a Chaucerian Merry England. Despite many student productions it then disappeared from the professional stage until a more symbolic, morris-dance-free revival at the *Open Air Theatre in Regent’s Park in 1974. Since then The Two Noble Kinsmen has been successfully revived at, among other venues, the Los Angeles Globe Playhouse (1979), the Edinburgh Festival (in a highly sexualized all-male production by the Cherub Theatre, 1979), the Centre Dramatique de Courneuve (also 1979), the Oregon Shakespeare Festival (1994), and the reconstructed *Globe (2000), but its most celebrated modern production remains Barry Kyle’s, which opened the RSC’s Swan auditorium in 1986. The main plot was given a stylized, samurai look, the rituals were impressive, and as the Jailer’s Daughter Imogen Stubbs morris-danced away with the entire show, as performers in that challenging but wonderfully showy role often do. The play has yet to be filmed.

Michael Dobson