f

F. The bibliographic abbreviation for *folio: hence ‘F1 [title of work]’ means ‘the first folio edition of [that work]’, ‘F2 [title of work]’ means ‘the second folio edition of [that work]’, and so on. In Shakespeare studies ‘F1’ almost invariably means the Shakespeare Folio of 1623 (Mr William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories and Tragedies).

Michael Dobson

Fabian is Olivia’s servant who joins in with the plot against *Malvolio in Twelfth Night.

Anne Button

Fabyan, Robert (d. 1513), clothier and sheriff of London. Fabyan was also an amateur historian who expanded his private diary into The New Chronicles of England and France, published posthumously in 1516. Holinshed, Grafton, and Halle would all turn to this history though it was Fabyan’s anecdotes rather than his analysis of cause and effect that made him popular.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

facsimile editions. Pioneered in 1807, reproductions of the First Folio and the quarto editions of Shakespeare’s plays proliterated after the advent of photography in the 19th century. Such facsimile editions are widely used by bibliographers and textual critics, as well as readers who wish to encounter Shakespeare’s texts in their original form. Although it is generally assumed that photographic reprints present a technically exact facsimile of the original, the notoriously unreliable facsimile of the First Folio prepared by J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps in 1876 was heavily retouched in pen and ink on nearly every page. Charlton Hinman’s Norton facsimile (1968) is made up of various leaves containing corrected formes from a number of actual copies, thus creating an ‘ideal’ copy that exists only in the facsimile.

Eric Rasmussen

Fair Em. The first quarto edition of this romantic comedy was published anonymously in 1590. It was catalogued as Shakespeare’s in the library of King Charles II, and unconvincingly attributed to *Greene in 1675.

Sonia Massai

Fairholt, Frederick William (1818–66), English genre painter. He produced fictional mises-en-scène from works by English poets, a series of which, entitled Passages from the Poets, included scenes inspired by Shakespearian drama. The works display little artistic accomplishment, but were engraved and published in weekly magazines, serving to broaden the popular appeal of the works they illustrated.

Catherine Tite

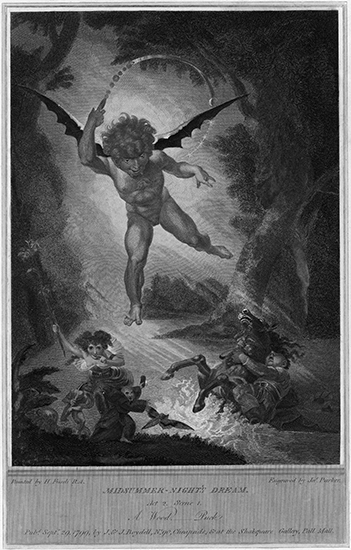

fairies are impossible to define accurately, because the term is used for beings who range from the angry or jealous dead of a family to small and benevolent nature-spirits, with many categories in between. Fairy beliefs originate in the ancient world of the Mediterranean, where fairies take the form of childhood demons or nymphs, and by the Renaissance stories about fairies were widespread in the European countryside. Such stories were especially common in Scotland, Ireland, the Mediterranean, and Eastern Europe, and in remote parts of England like the West Country and Romney Marsh, and these stories were often cautionary tales about dangerous beings who could draw those who saw them into illness, madness, or death. Fairies could also heal, however, and many cunning folk relied on them for information about healing and also about prognostication and finding lost or buried treasure. The fairies became increasingly sought after as possible sources of wealth towards the end of the 16th century as part of both elite and popular enthusiasm for conjuration as a means of advancement, and there are numerous accounts of how these beliefs were used by the unscrupulous to rob the unwary, as celebrated in *Jonson’s The Alchemist. Such beliefs often stemmed from Paracelsian doctrines of spirits, through which fairies came to be elected honorary servants to magicians, and that may be how demonologists began identifying them as devils. Another kind of fairy altogether came from the medieval romance, and was transformed by *Spenser’s Faerie Queene into a rather troubled symbol of benevolence; this was a fairy who signified wealth and aristocracy, though even she could not quite escape the connotations of trickery and ambition that clustered around her diminutive relations.

Shakespeare’s fairies were preceded by *Lyly and followed by others. As with his depictions of *witches, Shakespeare knew little and cared less about popular beliefs; he was no folklorist. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, his fairies are an amalgam of fragments of Reginald *Scot pasted on to *Ovidian gods and goddesses. *Robin Goodfellow (Puck), for example, is much more like the Ovidian and Anacreontic Cupid than like an English hob. Nevertheless, it was Puck’s speeches about his mischief-making that were influential, producing some imitative poems and prose fictions which are often mistaken for folkloric sources. In fact fairies and fairy lore are supreme instances of Shakespeare’s power to create popular culture; it is because of him, and specifically because of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, that fairies become associated with lyrical bucolic idylls, and this notion in turn influences Jonson, Herrick, *Milton, and the numerous poets of the 18th century whose weakly pretty fairy verse gives fairies a bad name. Shakespeare fixed the idea of fairies, consigning some fairies forever to the dustheap and conferring immortality on his own creations. His most important portraits of fairies occur in The Merry Wives of Windsor, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and The Tempest (if *Ariel is really a fairy, as Trinculo claims, and not a familiar) but there are many other references, most memorably the Queen Mab speech in Romeo and Juliet, which exerted an enormous influence over other, later, literary fairies. All Shakespeare’s fairies are associated with jokes, tricks, and disguise; all are linked with the countryside and country life. Apart from a reference to the fairy as a fate (Antony and Cleopatra 4.8.12), which recalls *Holinshed’s use of the term fate for the Weird Sisters, most brief references see fairies as one amongst many vague menaces of the night, with a few more specific allusions to fairies as child-stealers, generally as part of scenes concerning children lost to their parents in pastoral settings (esp. Cymbeline 3.7.14, 2.2.10, 4.2.217, 5.4.133, and Pericles 21.142). After Shakespeare, all fairies in English poetry became more or less funny and kindly, until the *Romantic poets revived the menacing fairy of earlier eras. In so far as his own attitude might be reconstructed, it approximates Horatio’s response to a long harangue about fairies and ghosts: ‘So I have heard, and do in part believe it.’

Diane Purkiss

Fairies, The. David *Garrick’s musical adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was performed anonymously in 1755, and Garrick never printed it under his own name, clearly anxious about the response which an attempt to assimilate Shakespeare to the suspect continental genre of all-sung opera might inspire. The opera, which achieved a respectable eleven performances, omits the mechanicals entirely, and introduces songs from a wide variety of other sources, including the works of Ben *Jonson: its score was by John Smith, a pupil of Handel.

Michael Dobson

Fairy. She talks to *Robin Goodfellow, A Midsummer Night’s Dream 2.1.

Anne Button

‘Fair Youth’. Some of the poems numbered 1 to 126 in the usual arrangement of Shakespeare’s Sonnets are addressed to a young man. Under the supposition that he is the same man throughout, he is sometimes referred to as ‘the fair youth’, although the phrase does not occur. A vast amount of commentary has been devoted to attempts to determine the exact nature of the relationship, especially whether it was, or became, sexual (ostensibly denied in 20). Many attempts have been made to identify the youth (or youths) with a real person (or persons). Various words have been interpreted as clues—frequent use of ‘fair’, ‘youth’, ‘beauty’; ‘lovely boy’ (126); incitements to marry (1–17); puns on ‘will’ (135–6), possible pun on ‘hues’ (20), and so on. He has often been supposed to be the dedicatee, *‘Mr W.H.’, described by the publisher as ‘the only begetter of these ensuing sonnets’. A favourite candidate in both roles has been Henry Wriothesley, Earl of *Southampton, dedicatee of Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece, who was nine years younger than Shakespeare. Another is William Herbert, 3rd Earl of *Pembroke, born in 1580, dedicatee, along with his brother Philip, of the First Folio. But if ‘begetter’ means ‘procurer’ rather than ‘inspirer’, other possibilities open up. The name of Robert Devereux, Earl of *Essex, has often been canvassed, especially by Baconians. Hamnet Shakespeare (who died at the age of 11) has been found behind some of the poems, as has Shakespeare’s brother Edmund. Father Robert Southwell, executed in 1596, the actor Will *Kempe, and Prince Harry (of the history plays) are among the more improbable candidates.

Stanley Wells

Fairy Queen, The. This adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with ‘singing, dancing and machines interwoven, after the manner of an opera’, was first performed at Dorset Garden theatre in London in 1692 and revived, with a revised score, the following year. The script, printed anonymously, was probably prepared by Thomas *Betterton: the score was certainly composed by Henry Purcell, and, though it uses none of the original play’s text, is the closest thing we have to a Purcell setting of Shakespeare. The adaptation cuts the mechanicals entirely, and adds a number of lavish special effects, including a representation of China and a masque in which Juno appears in a chariot drawn by mechanical peacocks. The huge revival of interest in baroque music since the middle of the 20th century has led to Purcell’s score being recorded several times, most notably by John Eliot Gardiner in 1982, and the semi-opera has been revived in its entirety with some success, particularly by the English National Opera.

Michael Dobson

Fairy Tale, A, a two-act adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream hurriedly abbreviated by George Colman the elder at Drury Lane from a full-length version of the play which, prepared in association with David *Garrick, proved a disastrous failure in November 1763. A Fairy Tale opened only three days after the longer version closed, and makes something of a hasty mess of the original’s structure: Theseus, Hippolyta, and the lovers disappear, leaving only the fairies and the mechanicals, who rehearse Pyramus and Thisbe but never get to perform it.

Michael Dobson

Faithorne engraving, attributed to William Faithorne (1616–91), English engraver. In this work, a bust of Shakespeare surmounts a representation of Lucretia and Collatius. The engraving was prefixed to an early edition of The Rape of Lucrece (1655).

Catherine Tite

Falconbridge, Lady. Mother of Robert Falconbridge and the Bastard, she admits the latter’s father was Richard Cœur-de-lion, King John 1.1.253–8.

Anne Button

Falconbridge, Philip. See Bastard, Philip the.

Falconbridge, Robert. He claims his father’s estate on the grounds of his elder brother’s illegitimacy, King John 1.1.

Anne Button

Falstaff, Sir John. See Henry IV Part 1 and Part 2; Merry Wives of Windsor, The; Fastolf, Sir John; Oldcastle, Sir John.

Falstaff’s Wedding (1760), William *Kenrick’s humorous sequel to 2 Henry IV, was dedicated to James *Quin, a particularly popular Falstaff. In a loose political setting, the plot exploits Falstaffian stereotypes: he marries Ursula for her inheritance and fights a duel with Shallow who is vainly pursuing a loan.

Catherine Alexander

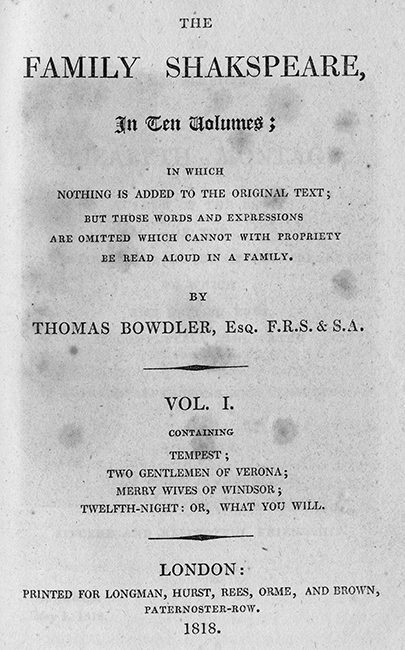

Family Shakespeare. The Revd Thomas Bowdler (1754–1825) published the 10-volume ‘Family Shakespeare’ in 1818 under his own name, completing the 20-play edition published anonymously by his sister in 1807. His stated object was to remove from the works ‘only those words and expressions which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family’. In practice, he (in collaboration with his unmarried sister Henrietta, whose name was kept off the title pages lest her reputation suffer) cut any passage which in his view smacked of obscenity. So, for example, he omitted the Porter scene in Macbeth, and Hamlet’s teasing of Ophelia before the play-within-the-play. Bowdler claimed on the title page of each volume that he added nothing to Shakespeare’s text, but in fact he made changes, as at the end of Measure for Measure, where the last lines are replaced by an invented passage in which the Duke looks forward to reigning with Isabella as his wife, and closes with the ‘royal maxim’, ‘To rule ourselves before we rule mankind’. The edition was attacked in the British Critic in April 1822, and Bowdler responded with a long defence. By 1836 the verb ‘to bowdlerize’ was current, with implications of crass and insensitive censoring.

The first complete edition of ‘The Family Shakespeare’. The enormous assistance Bowdler received from his unmarried sister Henrietta is not acknowledged on the title page, since a public admission that she understood the obscene passages she marked for omission would have harmed her reputation.

R. A. Foakes

Famous History of the Life of King Henry the Eight, The. See centre section.

Famous Victories of Henry V, The an anonymous play, first performed c.1586 and published in 1598, perhaps used by Shakespeare for 1 and 2 Henry IV and Henry V. The text we have of the Famous Victories is debased and possibly piratical. The original play may have been a two-part history, concerned with the Prince’s misdeeds and his development into a warrior-king. Similarities between the Famous Victories and Shakespeare’s plays allow for the possibility that Shakespeare knew this debased version but also provide glimpses of what the earlier play, perhaps his main source, was like. The Famous Victories provides the setting of the Eastcheap tavern and prototypes for the characters who gather there: Ned Poins and Gadshill, the reprobate Prince, even *Oldcastle, though as a shadow of his future self. The Famous Victories includes scenes that are central to Henry IV including the robbery at Gadshill, the derision of authority through role play, and the events surrounding the King’s death. Shakespeare may also have caught the saturnalian spirit of the earlier play.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

fanfare. Not a term used by Shakespeare; the various signals indicated in his plays for *trumpets, *drums, etc. May be divided into the military (*alarums, charge, *parley, *retreat) and the ceremonial (*flourish, *sennet, *tucket). The music for these in Shakespeare’s plays does not survive, though an idea of some military signals may be gained from battaglia pieces of the period, such as *Byrd’s The Battell.

Jeremy Barlow

Fang and Snare are two officers who attempt to arrest Falstaff, 2 Henry IV 2.1.

Anne Button

‘Farewell, dear heart, for I must needs be gone’, fragment of a song by Robert *Jones (from The First Book of Songs and Airs, 1600), sung by Sir Toby, with further extracts contributed by Feste and Malvolio, in Twelfth Night 2.3.98.

Jeremy Barlow

Farmer, Richard (1735–97), English classicist and scholar, author of An Essay on the Learning of Shakespeare (2nd edn. 1767). Farmer’s work responds to earlier critics who claimed that Shakespeare was skilled in both Latin and Greek. He argues instead that Shakespeare relied on contemporary translations of the ancients.

Jean Marsden

Farr, David (b. 1969), British theatre director. artistic director of the Gate Theatre, London, 1995–98, joint artistic director of Bristol Old Vic 2002–05, and artistic director of the Lyric Theatre Hammersmith 2005–09, Farr joined the *RSC as an associate director in 2009, beginning by directing Greg *Hicks as Leontes in The Winter’s Tale (2009) and as the title role in King Lear (2010). He went on to oversee ‘What Country Friends Is This?’, the RSC’s main entry in the 2012 *World Shakespeare Festival, a trilogy of plays comprising The Comedy of Errors, Twelfth Night, and The Tempest (the latter two directed by Farr), conceived around Shakespeare’s imaginative engagements with exile, asylum, travel, and shipwreck. In 2013 he directed Jonathan *Slinger as Hamlet in a spare, dark production haunted by formative memories, evoked by the empty school hall-cum-fencing-gym in which much of the action was set. His previous successes with the company were an award-winning samurai-era production of Coriolanus, starring Greg *Hicks (2002), and a heavily mediatized Julius Caesar (2004).

Will Sharpe

Fastolf, Sir John. In 1 Henry VI he deserts Talbot before Orléans (1.1.130–4) and again at Rouen (3.5). The outraged Talbot tears Fastolf’s garter from his leg, 4.1.15. The real Sir John Fastolf (d. 1459) had been awarded the Order of the Garter in 1429 but had it taken from him ‘for doubt of misdealing’ (*Holinshed), though he had also deserted Talbot at Orléans. He is thought to have been part of the inspiration for Sir John Falstaff.

Anne Button

Father who has killed his son. See Soldier who has killed his father.

Faucit, Helen (Saville) (1817–98), English actress from a theatrical family. She made her debut in 1836 at Covent Garden, playing Juliet, Katherine, Portia, Desdemona, and Constance in her first season. In 1837 she commenced her professional partnership with *Macready, during which she added Cordelia, Hermione, Rosalind, and Beatrice to her repertoire, performing them in her customary—increasingly dated—idealized style.

Helen Faucit’s marriage to Theodore Martin (knighted in 1880 for his biography of Prince Albert) coincided with Macready’s retirement and thereafter she acted only on special occasions such as the opening of the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, in 1879, when she appeared as Beatrice to Barry Sullivan’s Benedick. Later that year in the Calvert Memorial Performance—her age, vocal delivery, and costume notwithstanding—she evoked ‘intense admiration’ as Rosalind. Helen Faucit’s On Some of Shakespeare’s Female Characters (1892) was dedicated ‘by permission’ to Queen Victoria.

Richard Foulkes

Fauré, Gabriel (1845–1924), French composer. In 1889 he composed incidental music for Edmond Haraucourt’s play Shylock (based on The Merchant of Venice), which he revised as a concert suite for tenor soloist and orchestra in 1890. His incidental music for Julius Caesar (Théâtre Antique d’Orange, 1905) is a reworking of music originally written for Caligula (1888).

Irena Cholij

‘Fear no more the heat o’ the sun’, spoken or sung by Guiderius and Arviragus in Cymbeline 4.2.259. Early settings are unknown, but the lyrics became popular with English composers in the 20th century, including Geoffrey Bush, Dankworth, Walford Davies, Finzi, Gardiner, Gardner (two versions), Jacob, Lambert, Parry, Quilter, Vaughan Williams.

Jeremy Barlow

Fechter, Charles Albert (1822–79), actor, born in London, brought up in France where, after studying sculpture, he joined the Théâtre Français. In 1860 Fechter moved to London where he performed his innovatory Hamlet—in English—the next year. Fechter’s Prince was a pale Norseman in a flaxen wig whom he embodied with subtlety and depth, eschewing the traditions of the English stage. In contrast his Othello (also 1861) was a disaster, only partially redeemed by his subsequent Iago. The attempts of the Revd J. C. M. Bellew to secure a prominent place for his protégé in the Shakespeare tercentenary were thwarted; Fechter spent his declining years in the United States.

Richard Foulkes

Feeble, Francis. He is drafted into the army by Shallow and Falstaff, 2 Henry IV 3.2.

Anne Button

Felix and Philiomena. According to Elizabethan Revels accounts, a performance of ‘The history of felix and philiomena’ by the Queen’s Men took place shortly after New Year, 1585. This lost play was probably based on Jorge de Montemayor’s Diana enamorada, and may have served as a source for The Two Gentlemen of Verona.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

Felton portrait. See Burdett-Coutts portrait.

Feminine ending, the appearance of an additional unstressed syllable at the end of a verse line; thus in pentameter verse an eleventh syllable, as in most lines of Sonnet 87.

Chris Baldick

feminist criticism. Women’s critical engagements with Shakespeare date from Margaret Cavendish’s discussion of his plays in her Sociable Letters (1664), and have taken many forms, embracing fiction and performance as well as literary scholarship and criticism. Such engagements have often been motivated by a desire to defend or praise Shakespeare’s female characters which can be described as broadly feminist. When a feminist perspective on Shakespeare began to emerge within academic literary criticism in the 1970s, it was initially informed by a similar approach. This was counterbalanced, though, by a more challenging critique of Shakespearian constructions of femininity, which argued that by underwriting certain versions of womanhood with the power of the bard, they had a pernicious cultural effect. In subsequent decades, feminist Shakespeare criticism has flourished and diversified. Committed to making connections between the critic’s cultural moment and the Renaissance, feminist criticism of Shakespeare seeks both to intervene in contemporary cultural politics and to recover a fuller sense of the sexual politics of the literary heritage. If its primary effect has been to elicit fresh interpretations of the texts and their original historical location, it is also changing the way that Shakespeare is reproduced and consumed in education and in popular culture.

Kate Chedgzoy

Fencing. See hunting and sports.

Fenton, Geoffrey. See Bandello, Matteo.

Fenton, Master. He is in love with Anne Page in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Anne Button

Fenton, Richard (1746–1821), English author. He claimed in his anonymous Tour in Quest of Genealogy through Several Parts of Wales to own a manuscript of Shakespeare’s autobiography in Anne Hathaway’s handwriting, from which this work quotes. The quoted passages, however, are hardly to be taken seriously, and the whole section seems to be a satirical allusion to the Shakespearian *forgeries of William Henry Ireland.

Michael Dobson

Ferdinand, Prince of Naples, is separated from his father in the carefully managed shipwreck that opens The Tempest, and is subsequently introduced to Miranda, with all the hoped-for consequences, 1.2.368 ff.

Anne Button

Ferdinand, King of Navarre. See Navarre, Ferdinand, King of.

Feste, Olivia’s jester, scorned as ‘a barren rascal’ (1.5.80) by *Malvolio, plots revenge in Twelfth Night.

Anne Button

fiction. In addition to his many appearances as a fictional character (see Shakespeare as a character) in novels for both adults and children, Shakespeare has been important to novelists and fiction-writers in a number of ways. From very early on in the novel’s development as a genre, it was remarked that Shakespeare had affinities with the novel, not least as himself a plunderer of prose tales. Charlotte *Lennox in her Shakespeare Illustrated (1753–4) was the first to note his debts to the continental novella and to remark on how much clearer characters’ motivations were in the originals. Eighteenth-century novelists, such as William Goodall in his Adventures of Captain Greenland (1752), frequently invoked Shakespeare as a precursor because he was felt to break literary decorums in much the same way as did the new form. Hence certain great novelists have been dubbed ‘Shakespearian’, a term of approval meant to connote a certain large inclusiveness of sympathy and social range—such novelists have included Sir Walter *Scott, James Fenimore Cooper, George Eliot, James *Joyce, and Victor *Hugo, to name the most outstanding.

Since *Richardson published his first novel, Pamela (1740), it has been commonplace to use a liking for Shakespeare as a moral touchstone by which to try heroines—this has been true from Richardson’s Pamela, Clarissa, and Harriet Byron, Francis Burney’s Evelina, and so to Jane *Austen’s Fanny Price. Equally, it has been a common technique to include a staging or reading of a Shakespeare play within the novel upon which characters comment self-revealingly or in which they participate. Perhaps the most famous examples of this would be *Dickens’s Great Expectations (1860–1), in which, appropriately enough given the novel’s concern with the absent or embarrassing father, Hamlet is performed, or the performance of a spurious Shakespearian medley by the King and the Duke in Mark *Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

More generally, certain novelistic genres have been since their inception especially prone to Shakespearian quotation and allusion, a practice that became particularly widespread in the Romantic period. (See, for example, the references to Coriolanus which structure the discussion of industrial relations throughout Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley, 1849). Hence the early *Gothic novels of Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe, and Charles Maturin and the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott are permeated with Shakespearian epigraph, quotation, and allusion. There are several reasons for this: Shakespeare’s plays, themselves regarded as committed to the messy complexities of real life in defiance of literary convention, offered an important model to chroniclers of contemporary alienation for the depiction of extreme states of consciousness, while for novelists more interested in reanimating history the varieties of his characters’ personal languages, and the double-plot mechanism of the history plays themselves, modelled ways of representing the imagined past.

Finally, Shakespeare’s plots have served as the armature for many novels. Measure for Measure is reworked in Matthew *Lewis’s The Monk (1796); As You Like It serves as a reference point for the heroine of George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1874–6), Gwendolen Harleth, while Hamlet underscores the irresolution of Eliot’s eponymous hero. In the 20th century Lear underpins Jane Smiley’s novel A Thousand Acres and Falstaff haunts Robert *Nye’s novels. The plots of the last plays, most especially The Tempest, have structured romance from Scott’s tales of inheritance reinstated through to the modernities and postmodernities of John Fowles’s The Magus (1966/1977), Iris *Murdoch’s The Sea, the Sea (1978), Margaret Laurence’s The Diviners (1974), and Isak Dinesen’s short story ‘Tempests’ in Anecdotes of Destiny (1958).

Of all of the plays, Hamlet and Macbeth have undoubtedly been the most influential in this fashion, underlying early Gothic (such as Charles Brockden Brown’s Edgar Huntly, 1799) and its descendant, classic modern detective fictions, including Michael Innes’s Hamlet Revenge! (1937), Marvin Kaye’s Bullets for Macbeth (1976), and numerous others, not to mention the spoof by James Thurber, The Macbeth Murder Mystery (in itself a mini-essay on why these plays should have proved so tempting to the detective aesthetic). (Detective fiction has also amused itself with discovering, only in the end to destroy, sundry lost Shakespearian manuscripts: the most notable examples are Edmund Crispin’s Love Lies Bleeding, 1948, and Michael Innes’s The Long Farewell, 1958.) More generally, Hamlet underpins mainstream novels as diverse as Laurence *Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759–67) and A Sentimental Journey (1768), Johann Wolfgang von *Goethe’s Werther (1774) and his Wilhelm Meister series (1777–1829), Lillie Wyman’s Gertrude of Denmark (1924), Virginia *Woolf’s Between the Acts (1941), Iris Murdoch’s The Black Prince (1973), and John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius (1999).

The most influential of late 20th-century critical work on Shakespeare and the novel was directed towards examining how women novelists have rethought Shakespeare’s plots within their home genre (hence, in part, a resurgence of interest in Mary Cowden *Clarke’s supplementary short stories The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines, 1851–2). Here, The Tempest has been overwhelmingly influential, especially among women writing from a consciously postcolonial perspective—not merely American and Canadian (such as Constance Beresford-Howe’s Prospero’s Daughter, 1988, and Sarah Murphy’s The Measure of Miranda, 1987), but also Indian and Caribbean (Suniti Nahijoshi’s work, for example). African-American women writers have also found The Tempest peculiarly hospitable to an exploration of the intersection of race and gender: both Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day (1988) and Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby (1981) can be seen as critical readings of Shakespeare’s last romance.

Nicola Watson

fiddler, a broader musical term in Shakespeare’s time than now, applied to players of the *rebec and *lute as well as the violin (then a relatively new instrument in England), or used abusively to imply a professional musician of low status, as in The Taming of the Shrew 2.1.157.

Jeremy Barlow

‘Fidele’ is the name used by Innogen when disguised as a man in Cymbeline.

Anne Button

Field, Nathan (1587–1620), actor (Blackfriars Boys 1600–13, Lady Elizabeth’s Men 1613–15, King’s Men 1615–20) and dramatist. Nathan Field’s father, the Puritan anti-theatricalist John Field, wrote A Godly Exhortation by Occasion of the Late Judgement of God at Parris-garden (1583) which attributed to divine displeasure the Bear Garden’s fatal collapse during a Sunday performance, but he died before Nathan was old enough to be dissuaded from the theatrical life. Nathan Field’s name occurs in the Blackfriars Boys’ cast lists for Jonson’s Cynthia’s Revels and Poetaster. In the Sharers Papers of 1635 Cuthbert Burbage described Nathan as one of the ‘boys growing up to be men’ (the others were John Underwood and William Ostler) who joined the King’s Men after the Blackfriars reverted to the Burbages in 1608, but in Field’s case this happened ‘in process of time’, since he appears in the cast list for Jonson’s Epicoene which was first performed in 1609 by the Blackfriars Boys, renamed the Children of the Queen’s Revels, in their new venue the Whitefriars playhouse. In 1613 the Queen’s Revels Children merged with the Lady Elizabeth’s Men and Field stayed with this new company until he joined the King’s Men, apparently in 1615. As an actor Field was at the height of his powers (second only to Burbage and subsequently Taylor in the King’s Men) when he died. Field sole-authored two successful plays, A Woman is a Weathercock and Amends for Ladies, before becoming a King’s Man, and he collaborated on six after: Four Plays, or Moral Representations, in One with Fletcher; The Honest Man’s Fortune with Fletcher and possibly Massinger; The Jeweller of Amsterdam with Fletcher and Massinger; The Queen of Corinth with Fletcher and possibly Massinger; The Knight of Malta with Fletcher and Massinger; and The Fatal Dowry with Massinger.

Gabriel Egan

Field, Richard. See ‘Dark Lady’; printing and publishing; Sonnets.

Fiends. Joan la Pucelle invokes them in vain, 1 Henry VI 5.3 (they are mute).

Anne Button

Fiennes, James. See Saye, Lord.

Fiennes, Joseph (b. 1970), British theatre and film actor. Most notable among Shakespearian circles for his performance as Shakespeare in John Madden’s 1998 film *Shakespeare in Love, scripted by Marc Norman and Sir Tom *Stoppard, for which Fiennes was nominated for a Best Actor in a Leading Role BAFTA. He also played Troilus at the RSC in 1996–7, Edward II in Michael *Grandage’s 2001 production of *Marlowe’s play at the Crucible Theatre, Sheffield, and Berowne in Trevor *Nunn’s Love’s Labour’s Lost at the *National (2003).

Will Sharpe

Fiennes, Ralph (b. 1962), English actor. After training at RADA, Fiennes first worked in Shakespeare at the *Open-Air Theatre in Regent’s Park in the mid-1980s, where his roles included Cobweb, but after playing Romeo there under the direction of Declan Donnellan he was signed to the *Royal Shakespeare Company. Here his roles included Claudio in Much Ado About Nothing (1988), Henry VI (in Adrian Noble’s redaction of the first tetralogy The Plantagenets, 1988–9), the Dauphin (in Deborah Warner’s production of King John, 1989), Edgar, Berowne, and a fine Troilus (for Sam Mendes, 1990). He played Hamlet at the Hackney Empire in 1995, and the title roles in back-to-back productions of Richard II and Coriolanus at Gainsborough Studios, Shoreditch, in 2000. Despite increasing film commitments he has returned periodically to Shakespeare since, playing Prospero for Trevor *Nunn at the Haymarket in 2011 and combining cinema and Shakespeare with his own film version of Coriolanus, with himself in the title role, released in 2011.

Michael Dobson

‘Fie on sinful fantasy’, dance song performed by the fairies in The Merry Wives of Windsor 5.5.92; the original music is unknown.

Jeremy Barlow

fife, a small transverse *flute for military use, played with *drum (separately, unlike the one-person *tabor and *pipe combination); see Much Ado About Nothing 2.3.14–15.

Jeremy Barlow

Fife, Thane of. See Macduff.

Filario (Philario) is present when Posthumus and *Giacomo set the wager on Innogen’s fidelity in Cymbeline 1.4.

Anne Button

‘Fill the cup and let it come’, song fragment quoted by Silence in 2 Henry IV 5.3.54; the original music is unknown.

Jeremy Barlow

film. See silent films; Shakespeare on sound film.

Finland. Finland was introduced to Shakespeare through travelling groups of players, mainly from Sweden but also from Germany and Russia. In 1768 a troupe led by Carl Gottfried Seuerling (1727–95) performed Romeo and Juliet, which is likely to have been the first production in Swedish. Other prominent troupes were led by Pierre Deland (1805–62) and C. W. Westerlund (1809–79). In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the vernacular languages, Finnish and Finnish-Swedish, were thought unsuitable for the stage, so performances were usually in Swedish or German.

In the mid-19th century, after Finland had been ceded from Sweden to Russia, members of the educated elite such as J. V. Snellman (1806-81) began considering the role the translation of Shakespeare and other classics might play in promoting a Finnish national identity based on Finnish as a language of education and culture. The first ‘translation’ of Shakespeare into Finnish was by Jaakko Fredrik Lagervall (1787–1865), entitled Ruunulinna (1824). Very loosely based on Macbeth, it is set in Finland and written in rollicking trochaic tetrameter couplets.

In the 1870s, Finnish-language Shakespeare took a great leap forward. The Finnish Literature Society, working in close cooperation with the newly formed Finnish Theatre (later Finnish National Theatre), embarked upon the first complete works translation project, with the poet Paavo Cajander (1846–1913) as translator. Cajander began with Hamlet in 1879 and continued at the rate of one or two plays per year until 1912, when he had translated 36 plays. In addition to the English, Cajander consulted the Schlegel-Tieck German translation and Karl August Hagberg’s Swedish translation. When Aleksander III was crowned in Moscow in 1883, Finnish celebrations included a performance of Cajander’s translation of The Merchant of Venice.

By the early 20th century Shakespeare was well established in Finland, though not always the biggest box office draw. One significant landmark came in 1913, when Elli Tompuri played Hamlet, arguing that women should get to play intelligent roles (another female Hamlet was Leea Klemola in 1995). In 1916, Eino Leino, Finland’s leading poet at the time, published a tribute to Shakespeare that ended in a call for Finnish freedom (censored in its initial printing, the poem was later published in full after independence in 1917). The Finnish composer Jean Sibelius wrote incidental music for The Tempest in 1925, and for Sibelius’s 80th birthday in 1946, Maggie Gripenberg choreographed a one-act ballet to this music.

Cajander’s translations were performed for decades, though later directors began wishing for a more flexible and modern language that was truer to the native rhythms of Finnish. Yrjö Jylhä (1903–56) translated seven Shakespeare plays (as well as John Milton’s Paradise Lost), mainly in the 1930s. Another prominent Shakespeare translator was the poet Eeva-Liisa Manner (1921–95), who translated seven plays in the 1960s–80s, and whose translations are still valued today for their exquisite poetic qualities. In 2002 the publishing company WSOY embarked upon a second complete works translation project, now including 38 plays, which finished in 2013. Sixteen of the translations were done by Matti Rossi, whose early translations in the 1960s helped transform Finnish Shakespeare.

Rossi worked closely with the influential director Kalle Holmberg, whose productions of Richard III (1968, 1997), King Lear (1972), Macbeth (1989), and Henry IV (1991) brought a new ruggedness to Shakespearian production and took influences from Jan Kott and Peter Brook. In 1988 Ritva Siikala directed an all-female production of the Henry VI plays, with 34 actresses alternating between roles. Romeo and Juliet continues to be popular, and has also inspired a number of experiments, such as Otso Kautto’s all-male production (Teatteri Pieni Suomi, 1992) and Hilda Hellwig’s bilingual production at Lilla Teatern (1999), where the Capulets spoke Finnish and the Montagues Swedish. The most well-known Finnish Shakespeare film is Aki Kaurismäki’s Hamlet Goes Business (1987); another noteworthy production is Jotaarkka Pennanen’s eerie Hamlet (1992), with Heikki Kinnunen in the lead role.

In a small nation of just over five million people, famously able to be silent in two languages, Shakespeare translation and performance have by contrast proved rather voluble, playing a small but significant role in the development of literary Finnish and Finnish theatre.

Nely Keinänen

Finney, Albert (b. 1936), English actor. He proved his worth as Henry V at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre before playing lesser parts at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1959 during which he triumphantly took over from an indisposed Laurence *Olivier in Coriolanus. He worked in plays by John Osborne and others and in neo-realist British cinema and became an international star. He played Hamlet in the production which opened the National Theatre building on the South Bank in 1976; he also played Macbeth there in 1978. He evoked the spirit of the great Shakespearian actor-manager Donald *Wolfit in the film of The Dresser (1983).

Michael Jamieson

Finsbury. Fenland immediately north of the City, the manor of Finsbury was acquired by lease, by the city of London, from the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s in 1514. Golden Lane which runs through the manor was the location of the Fortune theatre, built by Philip *Henslowe in 1600.

Simon Blatherwick

fires in Stratford-upon-Avon. There were three great fires in Stratford during Shakespeare’s life, in 1594, 1595, and 1614. The first two, said to have broken out on a Sunday, were popularly ascribed to sabbath-breaking. The third, which started on Saturday, 9 July, destroyed 54 houses and much other property.

Stanley Wells

First Folio. See folios.

First Part of the Contention of the Two Famous Houses of York and Lancaster, The. See centre section.

Fisher, Thomas. See printing and publishing.

Fishermen, three. They take pity on the shipwrecked Pericles, Pericles 5.

Anne Button

Fiske, Minnie Maddern (1865–1932), American actress, who, although she made early appearances as the Duke of York in Richard III (1868) and Prince Arthur in King John (1874), showed little interest in Shakespeare, her only adult role being Mistress Page (1928).

Richard Foulkes

Fitton, Mary. See ‘Dark Lady’; Pembroke, William Herbert, 3rd Earl of; Tyler, Thomas.

Fitzwalter (Fitz-walter, Fitzwater), Lord. He challenges Aumerle and is himself challenged by the Duke of Surrey, Richard II 4.1. He announces the execution of two traitors, 5.6.13–16.

Anne Button

flags were flown over the theatres on days when performances were to be given. The de Witt drawing clearly shows one at the *Swan, the ‘Utrecht’ engraving shows flags over the Theatre and the Curtain, John Norden’s engraved panorama Civitas Londini shows flags over the Globe, the Rose, the Swan, and the Beargarden, and Wenzel Hollar’s Long View of London shows a particularly tall flagpole at the Hope, but none at the second Globe. It is possible that the colour of the flag indicated the genre of the play but more likely that, as with an inn sign, the flag told the illiterate the name of the venue. De Witt shows the Swan’s flag bearing a swan, and an inset in Norden’s Civitas Londini mislabels the Rose ‘The Star’, which is easily a misreading of a flag emblem.

Gabriel Egan

Flaminius is a loyal servant of Timon in Timon of Athens.

Anne Button

Flanders. See Dutch wars; Low Countries.

flats/shutters. Before the Restoration the theatres used little or no scenery, but thereafter it became usual to paint a realistic background onto canvas stretched over wooden frames (flats), often using the principle of perspective foreshortening. A shutter was two flats, each holding half the background, which could be run on grooves cut in the stage floor in order to meet on the stage. Before the Civil War masques and, less often, plays performed at court used this technology and John Webb, nephew and assistant to Inigo *Jones, brought it to the Restoration stage in his designs for William Davenant’s The Siege of Rhodes in 1661.

Gabriel Egan

Flavius. (1) The two tribunes Flavius and Murellus (spelled ‘Marullus’ by *Theobald and later editors), hostile to Caesar, expostulate with the commoners, Julius Caesar 1.1. (2) Also in Julius Caesar, Flavius is a follower of Brutus (mute, appearing 5.3 (under the name Flavio) and 5.4). (3) He is Timon’s steward, acknowledged by Timon as the ‘One honest man’, Timon of Athens 4.3.498.

Anne Button

Fleance, son of Banquo, escapes when his father is murdered, Macbeth 3.3. (Fleance is an invention of Horace Boece, on whose Scotorum historiae (1527) *Holinshed based the Scottish part of his Chronicles, a source for Macbeth.)

Anne Button

Fleay, Frederick Gard (1831–1909), English Shakespeare scholar associated with the Victorian ‘disintegrators’ of the New Shakespeare Society (1873–94). Fleay championed versification analysis as an application of positivist scientific methods to literary scholarship and as the key to solving questions of chronology and authorship in the Shakespeare canon, which his analysis led him to conclude contained the work of a number of playwrights besides Shakespeare.

Hugh Grady

Fleetwood, Charles (d. 1747), controversial English manager whose period at Drury Lane 1734–44 was significant for the appointments of *Macklin as artistic manager and *Garrick as a senior player.

Catherine Alexander

Fletcher, John (1579–1625), dramatist. Like his collaborator Francis *Beaumont, Fletcher was born into a well-connected family, but was driven to writing for the stage by financial need. Again like Beaumont, he did badly at first. His first play, an experiment in pastoral tragicomedy called The Faithful Shepherdess (1609), was a box-office failure, although it was admired by poets such as Ben *Jonson and George *Chapman, who contributed commendatory verses to the first edition, and later John *Milton, who echoed it in Comus. He preceded the printed version with a preface ‘To the Reader’, which defines tragicomedy for the benefit of the uncomprehending Jacobean public: ‘A tragicomedy is not so called in respect of mirth and killing, but in respect it wants deaths, which is enough to make it no tragedy, yet brings some near it, which is enough to make it no comedy, which must be a representation of familiar people, with such kind of trouble as no life be questioned; so that a god is as lawful in this as in a tragedy, and mean people as in a comedy’. This definition fits many of Shakespeare’s comedies as well as his late plays: in Twelfth Night, for instance, Viola’s life is threatened by Duke Orsino, while Measure for Measure is heavy with the fear of death. Accordingly, the first successful tragicomedy written by Beaumont and Fletcher together, Philaster (1620), features a woman disguised as a page who is sent, like Viola, to woo another woman for the man she loves, and is later stabbed by him in a fit of jealousy, as if to fulfil Orsino’s threats. The man, Philaster, is one of a series of tormented heroes in the Beaumont and Fletcher canon, a fusion of Hamlet and Othello, always balancing on a knife-edge between hysteria and madness. Philaster has much in common with Shakespeare’s Cymbeline—both were written in about 1609—but it is not clear which came first: both Shakespeare and Fletcher had already written tragicomedies to which these plays were natural successors. It would seem that tragicomedy was simply the new genre of the moment, and that Shakespeare, Fletcher, and Beaumont sparked each other off in their efforts to develop that genre to its full potential.

Beaumont and Fletcher had good professional reasons for drawing on situations and characters from Shakespeare’s work. They began by writing for children’s companies, including the Children of the Queen’s Revels, who were based at the Blackfriars theatre. When Shakespeare’s company, the King’s Men, took over the Blackfriars in 1608, Beaumont and Fletcher began to write for them, producing three of their finest plays between 1609 and 1611: Philaster, A King and No King (published 1619), and The Maid’s Tragedy (also published 1619). After this Fletcher seems to have been groomed to succeed Shakespeare as principal dramatist for the company. He wrote three plays in collaboration with Shakespeare—the lost Cardenio (c. 1612–13), All Is True (Henry VIII) (1623), and The Two Noble Kinsmen (1634)—before Shakespeare gave up writing for the stage. Beaumont stopped writing at about the same time as Shakespeare, and Fletcher went on to write many more plays—tragedies, comedies, and tragicomedies—both alone and with others (his chief partner after Fletcher was Philip Massinger). But when his dramatic works were published in 1647, they bore the title Comedies and Tragedies Written by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, and it is as Beaumont’s collaborator that he has entered the mythology of the theatre.

The extraordinary unity of Beaumont and Fletcher’s work together provoked endless speculation about the nature of their relationship. John *Aubrey wrote: ‘They lived together on the Bankside, not far from the Playhouse, both bachelors; lay together; had one wench in the house between them, which they did so admire; the same clothes and cloak, etc., between them.’ After Shakespeare’s retirement their plays rapidly outstripped his in popularity, and remained the most popular and influential works of the Jacobean theatre for most of the 17th century. They deserve to be better known.

Robert Maslen

Florence, the capital of Tuscany, figures in All’s Well That Ends Well (Florence is the setting of 3.5 and successive scenes). Florence is also mentioned in The Taming of the Shrew (1.1.14 and 4.2.91) and ‘Florentines’ (people from Florence) in Much Ado About Nothing (1.1.10) and Othello (1.1.19 and 3.1.39).

Anne Button

Florence, Duke of. He appoints Bertram ‘general of our horse’ in All’s Well That Ends Well 3.3.1.

Anne Button

Florio, Giovanni (John) (?1554–?1625), translator. The English-born son of an Italian Protestant refugee, Florio graduated from Oxford University and began to translate Italian texts into English. He produced two grammars, Florio his First Fruits (1578) and Second Fruits (1591), and an Italian–English dictionary (1598), works that Shakespeare probably knew if, as seems likely, he studied Italian himself. But Florio was most renowned for his translation of Montaigne’s Essais, published in 1603. In a copy of Volpone that he gave to Florio, Ben Jonson acknowledged his debt to the translator and called him a friend to the theatre. He was certainly a friend to Shakespeare’s drama and possibly to the man himself. Shakespeare and Florio may have been acquainted with one another through their shared patron Henry Wriothesley, Earl of *Southampton. Hence, Shakespeare may have had access to Florio’s famous library, and the Italianate aspects of his plays may have been inspired by the literature he found there. Florio’s own book, his translation of *Montaigne, is the most obvious connection between them. Passages in The Tempest suggest Shakespeare’s use of Florio’s translation, in particular Gonzalo’s speech on his ideal commonwealth. King Lear features more than 100 words, new to Shakespeare’s work, that could have been found in Florio’s Montaigne. In 2013 Saul Frampton published a lengthy article in the Guardian, arguing, ahead of a book-length study on the subject, that Florio edited the First Folio of Shakespeare, introducing many lexical items aimed at correction and improvement in the process.

Jane Kingsley-Smith, rev. Will Sharpe

Florizel, the son of Polixenes, woos Perdita (who he thinks is a shepherdess) disguised as ‘Doricles’, a shepherd, in The Winter’s Tale 4.4.

Anne Button

Florizel and Perdita. See Winter’s Tale, The; Garrick, David.

Flourish, a call on *trumpets or *cornets, perhaps extemporized, usually heralding a processional entrance; see The Two Noble Kinsmen 2.5 opening (‘short flourish’), and also Richard II 1.3.122 (‘long flourish’).

Jeremy Barlow

‘Flout ’em and cout ’em’, fragment sung by Stefano and Trinculo in The Tempest 3.2.123; the original music is unknown; Caliban tells the pair that their tune is wrong; they are corrected by Ariel on *tabor and *pipe.

Jeremy Barlow

Flower family. See Flower portrait; Shakespeare Memorial Theatre; Shakespeare tercentenary of 1864.

Flower portrait, half-length, oil on panel, dated 1609, inscribed ‘W. Shakespeare’. Now in the *RSC collection in Stratford, the portrait is named after its former owner Mrs Charles Flower, of the Stratford brewing dynasty. Following a late 19th-century trend for identifying likely originals for Martin *Droeshout’s engraved portrait, the Flower portrait was described as an original for the First Folio engraving by M. H. Speilmann in 1906. Recent scientific examination has shown that it makes use of pigment that was not available until the early 18th century.

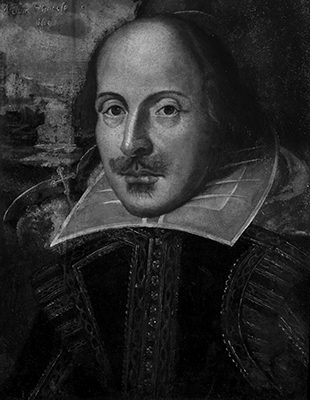

The ‘Flower’ portrait of Shakespeare, now in the RSC Collection in Stratford. The painting probably derives from Martin Droeshout’s title-page engraving for the First Folio rather than being, as some have claimed, the original on which the engraving is based.

Catherine Tite

Fluchère, Henri (1898–1987), French scholar. Fluchère gave a decisive impulse to Elizabethan studies in France after the Second World War with his Shakespeare, dramaturge élisabéthain (1948). He edited and prefaced Shakespeare’s works for the Pléiade two-volume Shakespeare (1959). Many books followed including a prose translation of and introduction to Coriolan (1980). In 1946 he created and directed the Maison Française d’Oxford College, and in 1968 was elected Dean of the Arts Faculty at the Université d’Aix-en-Provence. In 1977, with other scholars specializing in 16th-century English literature, he launched the Société Française Shakespeare, a branch of the International Shakespeare Association, and chaired it for the first term.

Isabelle Schwartz-Gastine

Fluellen, Captain. A Welshman in Henry V, he quarrels with Macmorris (3.3), Williams (4.8), and *Pistol (5.1).

Anne Button

flute, in Shakespeare’s time a plain wooden tube with six finger holes; it came in various sizes, the most usual being the middle-sized instrument in D. The term ‘flute’ then might also indicate *recorder.

Jeremy Barlow

Flute, Francis. A bellows-mender in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, he plays Thisbe in the play-within-the-play of 5.1.

Anne Button

flying. In the drama a supernatural character (for example a classical god) might best enter by being lowered from the ‘heavens’ over the stage, suggesting flight. The actor sat in a carriage attached by ropes to a winch in the stage cover, and the first playhouse to have a full stage cover was the Rose. In 1595 *Henslowe paid carpenters for ‘making the throne in the heavens’, which was the first known descent machine for flying. The Globe seems not to have been fitted with a flight machine until around 1608–9 when the King’s Men brought it into conformity with their other playhouse, the Blackfriars, which had one. Shakespeare’s pre-1608 supernatural characters—Hymen in As You Like It and Diana in Pericles—walk rather than fly onto the stage. Sound effects (for example thunder) or celestial music added to the impact of a supernatural descent and also helped drown the creaking of the winch.

Gabriel Egan

Foakes, R.A. (Reginald Anthony Foakes) (1923–2013), British Shakespeare scholar. One of the most eminent and influential Shakespeare scholars of the second half of the 20th century, and the first decade of the 21st, Foakes was one of the founding fellows under Allardyce Nicoll of the *Shakespeare Institute, an institution that has greatly advanced international postgraduate research in many areas of the English Renaissance, and been the training ground for a number of notable academics. He went on to teach at Durham, and then Kent, where he founded the department of English and served as Dean of Humanities. His later career was spent at UCLA, where he moved in 1982 as Professor Emeritus, enjoying a period of enormous productivity in his semi-retirement. Foakes’ great scholarly range and bequests to Shakespeare studies cover the archival and editorial in his editions of Philip *Henslowe’s Diary (1961, repr. 2002) and King Lear for the Arden Shakespeare (1997); the historical, in Illustrations of the English Stage: 1580–1642 (1985); practical, humane, and precise literary criticism most famously manifested in his great study Hamlet Versus Lear (1993), as well as a more thematic and theoretical approach as seen in Shakespeare and Violence (2002).

Will Sharpe

Foersom, Peter (1777–1817), Danish actor and translator. The first to translate Shakespeare into Danish verse, he acted Hamlet in the first ever Shakespeare production at the Royal Theatre, Copenhagen, 1813. His translations of ten of the tragedies and histories (1807–18) have remained influential.

Inga-Stina Ewbank

Folger Collection. See Folger Shakespeare Library.

Folger Shakespeare. This pocket paperback edition of individual plays issued in Washington and New York between 1957 and 1964 was edited by the director of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Louis B. Wright, with Virginia A. Lamar. It was aimed at ‘the general reader’, and proved, with its brief and simple notes on pages facing the text, and illustrations drawn from old documents and books in the Folger Library, to be very popular for use in schools. Using the same basic format, Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine are re-editing the series in the light of current thinking about Shakespeare’s texts.

R. A. Foakes

Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington. It houses the world’s largest collection of Shakespeare’s printed works, including 82 copies of the First Folio and 204 quartos, among them a unique copy of Titus Andronicus (1594). The collection also comprises an estimated 27,000 paintings, drawings, engravings, and prints representing or associated with Shakespeare, including the *Ashbourne (Kingston) portrait. The collection was amassed and then given to the nation in 1928 by Henry Clay Folger (1857–1930) and his wife.

Susan Brock

folios. A book in which the printed sheet is folded in half, making two leaves or four pages, is known as a folio. The prestigious folio format was used for works by the leading theologians, philosophers, and historians of the day: Holinshed’s Chronicles (1587), Richard Hooker’s Laws (1611), Sir Walter Ralegh’s History of the World (1614), and William Camden’s Annals (1615). The groundbreaking edition of Ben Jonson’s Workes (1616) marked the first time that the œuvre of a playwright had ever been published in folio. But the Jonson folio had included prose and poetry as well as dramatic texts. A folio devoted entirely to plays was unprecedented before the publication in 1623 of Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, the First Folio.

We know very little about the planning stages of the First Folio. It may be that Shakespeare’s friends and fellow actors in the King’s Men—chief among them John Heminges and Henry Condell—were planning an authorized collection of his plays when they got wind of Thomas Pavier’s plans to bring out an unauthorized collection in 1619, or perhaps they got the idea from Pavier.

In their epistle ‘To the great Variety of Readers’, Heminges and Condell describe their task: ‘It has been a thing, we confess, worthy to have been wished, that the author himself had lived to have set forth, and overseen his own writings. But since it hath been ordained otherwise, and he by death departed from that right, we pray you do not envy his friends, the office of their care, and pain, to have collected and published them.’

A syndicate of publishers was at some point formed to underwrite the venture. The colophon on the last page of the Folio is unusual in that it emphasizes the financial costs of the undertaking: ‘Printed at the Charges of W. Jaggard, Ed. Blount, I. Smithweeke, and W. Aspley, 1623’. Jaggard’s association with Pavier’s project no doubt involved the accumulation of rights to plays that had been printed earlier, a vital component for the production of the Folio. John Smethwick was probably invited to join the cartel because he held the copy rights to Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Love’s Labour’s Lost, and The Taming of the Shrew. Similarly, William Aspley held the rights to 2 Henry IV and Much Ado About Nothing.

The imprint claims that the book was ‘printed by Isaac Iaggard, and Ed. Blount’. However, Blount was only a publisher; the printing of the Folio was done entirely in the shop of William Jaggard and his son Isaac. Charlton Hinman, in his reconstruction of the events in the Jaggard printing-house, demonstrated that the printing of the 907-page Folio began early in 1622 and took nearly two years to complete, during which time as many as nine compositors worked on the project. Hinman established that the Folio was set by formes (not seriatim, as had been previously thought) and identified the pairs of type-cases used by the compositors. Apparently the copy was cast off so that two compositors could work simultaneously on the same forme, thereby speeding up composition in relation to presswork. In setting the text of The Two Gentlemen of Verona, for instance, Compositor C set page 30 (signature C3v) while Compositor A simultaneously set page 31 (signature C4r).

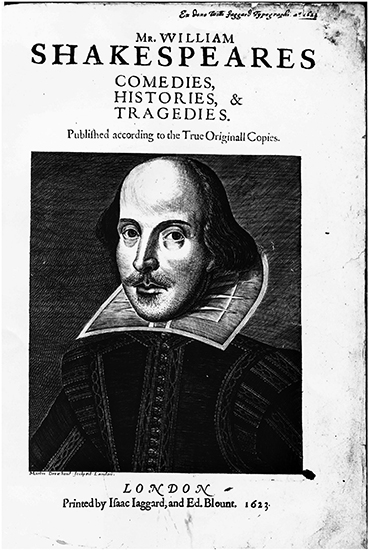

The title page of the First Folio, 1623. This presentation copy from the publisher William Jaggard is now, along with more than 70 other copies, in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington.

The title page advertises the plays within as ‘published according to the true original copies’ and Heminges and Condell distinguish their authoritative texts from some of the previously published quarto editions: ‘before you were abused with diverse stolen and surreptitious copies, maimed, and deformed by the frauds and stealths of injurious impostors that exposed them; even those are now offered to your view cured and perfect of their limbs; and all the rest absolute in their numbers as he conceived them.’ The publishers apparently commissioned the professional scribe Ralph *Crane to prepare transcripts of the original manuscripts to be used as printer’s copy for The Tempest, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Measure for Measure, The Winter’s Tale, and possibly Cymbeline. These were among the first plays to be printed, so it appears that Crane had an association with the Folio enterprise only in its early stages. In addition to Crane’s transcripts, the Folio compositors had access to a wide variety of copy. Of the 36 plays in the Folio, twelve appear to have been set up from earlier printed quartos that had been annotated from a manuscript playbook: Titus Andronicus, Richard III, Love’s Labour’s Lost, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet, Richard II, The Merchant of Venice, 1 Henry IV, Much Ado About Nothing, Hamlet, Troilus and Cressida, and The Tragedy of King Lear; the playbooks themselves were apparently used as copy for only three plays in the Folio: Julius Caesar, As You Like It, and Macbeth; another nine were set from Shakespeare’s foul papers: The Taming of the Shrew, The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI), Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI), 1 Henry VI, The Comedy of Errors, Henry V, All’s Well That Ends Well, Timon of Athens, and Antony and Cleopatra; and six from transcripts made by unidentified scribes: King John, 2 Henry IV, Twelfth Night, Othello, Coriolanus, and All Is True (Henry VIII).

Heminges and Condell divided the plays into the generic categories of the volume’s title—Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies—and apparently exercised some care in ordering the plays so that each section begins and ends with plays that had not previously appeared in quarto. The only exception to this rule is Troilus and Cressida, the first page of which was initially printed on the verso of the last page of Romeo and Juliet, in the middle of the tragedies section; the text was then reset and re-placed to come first among the tragedies—or last among the histories; the table of contents for the Folio omits the play and thus does not make it clear to which category it belongs. Heminges and Condell seem to have made a conscious decision not to include Shakespeare’s poems in the collection, and they may have intentionally omitted some of the late collaborative plays as well (Pericles, Cardenio, and The Two Noble Kinsmen).

The first preliminary page of the First Folio consists of a verse by Ben Jonson on the *Droeshout portrait, which appears on the facing title page:

This figure, that thou here seest put

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut;

Wherein the Graver had a strife

With Nature, to out-do the life:

O, could he but have drawn his wit

As well in brass, as he hath hit

His face; the Print would then surpass

All that was ever writ in brass.

But, since he cannot, reader, look

Not on his picture, but his book.

B. J.

Then follows the dedication to William Herbert, 3rd Earl of *Pembroke, and his brother Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery. The next item is Heminges and Condell’s epistle ‘To the Great Variety of Readers’, two commendatory poems by Ben Jonson and Hugh Holland, the ‘Catalogue of the several Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies contained in this Volume’, two more commendatory verses, and finally a list of the ‘Principal Actors’ in the plays.

The First Folio was expected to be on the market by mid-1622; it was included in the Frankfurt book fair’s catalogue as one of the books printed between April 1622 and October 1622. In the event, however, the Folio did not actually appear until very late in 1623. On 8 November 1623, Blount and Isaac Jaggard entered in the Stationers’ Register their copy rights to the plays that had not been previously published:

Mr William Shakspeers Comedyes, Histories, and Tragedies soe manie of the said Copies as are not formerly entred to other men. vizt. Comedyes. The Tempest. The two gentlemen of Verona. Measure for Measure. The Comedy of Errors. As you Like it. All’s well that ends well. Twelft night. The winters tale. Histories. The thirde parte of Henry the sixt. Henry the eight. Coriolanus. Timon of Athens. Julius Caesar. Tragedies. Mackbeth. Anthonie and Cleopatra. Cymbeline.

The printing of the Folio was probably completed shortly thereafter—a copy at the Bodleian Library in Oxford was sent for binding on 17 February 1624—and the book was then available in bookshops for the princely sum of £1 (40 times the cost of an individual quarto).

The volume was so successful and demand apparently so great that a second edition was required within less than a decade. In 1632, Thomas Cotes, who had taken over the Jaggard shop following Isaac’s death in 1627, printed the Second Folio for a syndicate of publishers that again included Smethwick and Aspley. The Second Folio was a carefully corrected page-for-page reprint of the first that made hundreds of minor changes in the text, the majority of which have been accepted by modern editors. The preliminaries of the Second Folio include John Milton’s first published poem, ‘An Epitaph on the Admirable Dramatic Poet W. Shakespeare’. The elegant paper stock used for the Second Folio occasioned William Prynne to lament in Histrio-mastix (1633) that ‘playbooks are grown from quarto into folio’ and that ‘Shakespeare’s plays are printed in the best crown paper, far better than most Bibles.’

The Third Folio appeared in 1663, with a second issue in 1664 that added Pericles and six apocryphal plays: The London Prodigal, Thomas, Lord Cromwell, Sir John Oldcastle, The Puritan, A Yorkshire Tragedy, and Locrine. The Fourth Folio was published in 1685; 70 pages of this edition were reprinted c.1700 to make up a shortage and may be considered a Fifth Folio printing. There are 233 copies of the First Folio known to survive, the *Folger Shakespeare Library housing the largest single collection. New copies surface very infrequently, but one was discovered in the library of Saint-Omer in 2014.

Eric Rasmussen

Folio Society Shakespeare. The 37 volumes of this handsomely printed edition were issued between 1950 and 1976, using the text of the New Temple Shakespeare. They are chiefly notable for the introductions, of varying interest, written mainly by well-known actors and directors, among them Laurence *Olivier, Paul *Scofield, Richard *Burton, Peter *Brook, and Peter *Hall. The texts are illustrated with reproductions of costume and stage designs from the period. Thirty-five of the introductions were published as a separate book in 1978. The Folio Society has since reprinted the *Oxford edition twice and also offers each work in a boxed set in a fine, letterpress edition which reprints the text of the Oxford multi-volume edition along with a reprint of the full version of that edition.

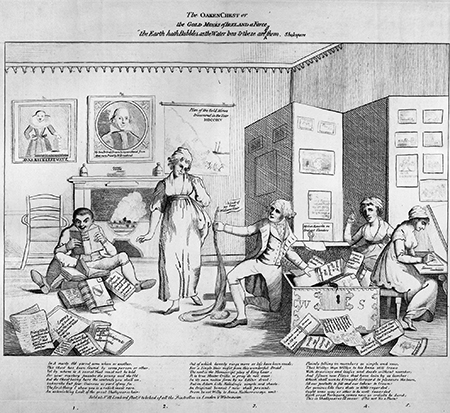

Shakespeare’s greatest glutton, Sir John Falstaff: a popular engraving published by Bowles and Carver, c.1790, loosely based on earlier depictions of the actor James Quin in what became his best-loved role.

R. A. Foakes, rev. Stanley Wells

food and drink. The Elizabethan year (see calendar) fell into feast and fast periods: both Wednesdays and Fridays were fish-eating days until 1585 and the six weeks of Lent were equally meatless except in the case of pregnant women, children, and invalids. At such times the poor ate saltfish (such as the ‘poor-john’ Caliban is said to smell like, The Tempest 2.2.25–7), while the rich might eat sprats or herrings, fresh, dried, smoked, or salted. Christmas feasting, during which open house was kept by big households, ran from 1 November right through to Twelfth Night (6 January): its special dishes included boar brawn, mince pies (still made with spiced meat), and the ‘flapdragon’ mentioned in Love’s Labour’s Lost (5.1.42). Other feasts would include funerals (cf. Hamlet on the reuse of leftovers, 1.2.179–80), weddings (cf. Taming of the Shrew 3.3), sheep-shearing (as in The Winter’s Tale, at which the shepherds plan to eat ‘warden pie’, a pear pie coloured with saffron and spiced with mace, nutmegs, ginger, prunes, and sultanas, 4.3.44–8), and harvest-home.

The richer ate three meals a day, the poorer more like two. Breakfast, served generally between 6 and 8 a.m., varied widely from the big hunting breakfasts recorded as being given for Elizabeth to private collations: the food ranged from ale, beer, or wine, boiled beef or mutton, and bread, to eggs, milk, and butter. In Antony and Cleopatra there is admiring talk of ‘eight wild-boars roasted whole at a breakfast’ (2.2.186–7). The poor would be more likely to eat some sort of cereal made into a pottage.

The main meal of the day, dinner, was served at 11 a.m. for the gentry, the middling sort eating at noon. It was laid with great ceremony on a long table, with the wine, wine cups, and basin and ewer for washing on the ‘court-cupboard’ (not unlike a modern sideboard; cf. Romeo and Juliet 1.5.6–7). The guests would for the most part be seated on joint-stools in order of social rank—hence the dramatic social solecism of Lady Macbeth’s hasty command to her guests to ‘stand not upon the order of your going’ (Macbeth 3.4.118). The meal might last two, three, or four hours, and would consist of two courses, laid in prescribed patterns on the table for the diners to help themselves. The first course would consist of ‘gross meats’ or the equivalent on fish-days, perhaps buttered and spiced fish pies of sturgeon or salmon; the second of poultry, raised pies in ‘coffiins’ of pastry (cf. Titus’s cannibal version, Titus Andronicus 5.2.185–90), puddings, ‘kickshaws’, or ‘made dishes’ (e.g. fricasses, carbonadoes, hashes, collops), and salads of cooked, pickled, or raw vegetables, herbs, and flowers. The third course was the ‘banquet’ course. Whereas the first two courses would have been eaten in either the hall (now steadily shrinking in size) or the newly fashionable private dining parlour, the banquet ‘to close our stomachs up | After our great good cheer’ (Taming of the Shrew 5.2.9–10) would be taken in another location entirely—another room (such as the ‘privy chamber’ to which Wolsey’s most privileged guests withdraw for their banquet, All Is True (Henry VIII) 1.3.101–2), an outside summer house, temporary or permanent, or perhaps a gazebo on the roof. There guests would be regaled on expensive sweetmeats skilfully prepared by the lady of the house—sweet biscuits and tarts, a marchpane, wet and dry ‘suckets’ (preserved fruits), and fresh fruit, all preceded by a ‘conceited’ dish of sugar sculpture made to represent a bird, animal, fish, or even, on one occasion, a castle made of sugar firing tiny guns with real gunpowder at its besiegers. The witty, whimsical, and luxurious nature of this food is reflected in Benedick’s description of Claudio’s affected language in Much Ado About Nothing as a ‘fantastical banquet’ (2.3.15). All told, there might be of the order of thirty different dishes for a humblish feast, though more like five or six for the country gentleman not expecting guests (compare Justice Shallow’s menu in 2 Henry IV 5.1.22–4). While the main courses were eaten on wooden, pewter, or silver trenchers depending on the wealth of the household, the banquet was served on glass plates (often hired) and eaten off wafer-thin wooden or sugar plate trenchers often decorated on the underside with a verse or epigram called a ‘roundel’ and read out at the end of the meal. Food was carved with a knife (often worn at the man’s belt) but eaten with the fingers—forks were still a novel luxury item. Fingers were washed at the end of every course in bowls of rose-water. In between courses there might be entertainment laid on, music, a masque, or dancing—hence the appositeness of the masquing Ariel at the magic banquet in The Tempest (3.3.52ff.).

Supper, by contrast, was usually very much an afterthought. Gentry supped between 5 and 6 p.m., farmers and merchants not before 7 or 8 p.m., and labourers at dusk. The meal was light—perhaps eggs and a posset (hot milk fortified with sugar, spices, eggs, and wine, brandy, or ale, and on one notable occasion with additional soporifics by Lady Macbeth, Macbeth 2.2.6–8).

Elizabethan England was full of the excitement of new food imports, and Shakespeare’s plays reflect this. New fruits and vegetables from the Americas made their appearance: tomatoes, and potatoes both sweet and common. With Dutch refugees came asparagus, cardoons, globe artichokes, and cauliflowers, and from southern Europe the apricot, quince, fig, and melon (the real Richard II’s garden would not have featured the ‘dangling apricot’ of 3.4.30). The more expensive or exotic the food, the more likely it was to be regarded as an aphrodisiac—hence Falstaff’s excited invocation of potatoes, eringoes (the candied root of sea-holly), and kissing-comfits in The Merry Wives of Windsor (5.5.18–21).

In drinks, too, Falstaff proves to have expensive tastes. The generality drank ale or beer, but large quantities of claret, malmsey, madeira, and sack (a dry Spanish wine not unlike sherry), sometimes ‘burnt’, that is to say, heated (see Twelfth Night 2.3.184), were shipped in from France, Crete, Madeira, and Spain respectively. Households also produced flower and fruit wines, often for medicinal use.

Food as a source of Shakespeare’s imagery was well studied by *Spurgeon, in particular bread and candy. Feasts and interrupted feasts feature importantly; see in particular The Taming of the Shrew, Macbeth, Titus Andronicus, Timon of Athens, Antony and Cleopatra, As You Like It, and The Tempest. But delight in food and drink in Shakespeare is synonymous with Falstaff, whose tastes provide such a sharp profile of fashionable gluttony.

Nicola Watson

fools. In Shakespeare’s time, fools or jesters were retained as providers of entertainment to both the royal court and well-to-do households like those of Olivia in Twelfth Night and Leonato in Much Ado About Nothing. They were usually male, and would often wear a distinctive costume of ‘motley’ (parti-coloured cloth), wear a coxcomb on their head (not the belled hood of later tradition but a removable cap), and carry a ‘bauble’ or carved stick, which was often a focus for phallic humour. Some were professional comedians who adopted a façade of folly, others mentally handicapped individuals, known as ‘naturals’, whose innocent antics were considered humorous. Their remarks could also be sharply satirical: both types of fool would be granted much greater latitude in speaking than would ordinary courtiers, although King Lear’s fool is threatened with whipping when he goes too far.

Shakespeare began to use fools as stage characters with Touchstone in As You Like It. Scholars have postulated that he may have been responding to an innovation in a lost play by George Chapman for a rival acting company, or to the arrival in his own company of a new principal comic actor, Robert *Armin. Most of these figures, including Feste in Twelfth Night and Lavatch in All’s Well That Ends Well, are professionals who are consciously wiser than the jesting roles they adopt, though the Fool in King Lear may be a ‘natural’. All of them see and describe the plays’ events in meaningful ways that are not available in normal social discourse.

Martin Wiggins

fools. (1) Servant of a prostitute, a fool appears briefly in Timon of Athens 2.2. (2) In The Tragedy of King Lear a fool accompanies Lear into the storm, but does not appear after 3.6 (History of King Lear 13).

Anne Button

foot, a patterned metrical unit (iambic, trochaic, pyrrhic, spondaic, anapaestic). See metre.

George T. Wright

Foote, Samuel (1721–77), controversial English actor and writer. He was trained by *Macklin and first appeared as Othello to his mentor’s Iago. Best known as a satirist (and from 1767 as owner of the Haymarket), he was particularly scornful of the *Stratford Jubilee but was himself the subject of ridicule—and some dreadful puns on his name—following the amputation of a leg.

Catherine Alexander

Forbes-Robertson, Sir Johnston (1853–1937), English actor, who at the outset of his career (1874) came under the influence of the veteran Shakespearian actor Samuel Phelps and thereafter sought to uphold his ‘histrionic pedigree’. Described by Shaw as ‘essentially a classical actor’, Forbes-Robertson put his natural gifts and personality to the service of his roles. In juvenile parts (Hal to Phelps’s Henry IV in Manchester, 1874; Claudio with Irving and Terry at the Lyceum, 1882; and Romeo between 1880 and 1895 to a succession of Juliets, including in 1895 Mrs Patrick Campbell who also partnered him in Macbeth in 1898) he was judged by some to be rather insipid, but coming to Hamlet (rather late at 44 in 1897) he captured the grace, intellect and melancholy of the Dane in what for many was the definitive performance of its day. In 1913 (aged 60) he committed his legendary Hamlet to—silent—film.

Richard Foulkes

Forbidden Planet, 1956, American science-fiction film, inspired by Shakespeare’s The Tempest, directed by Fred M. Wilcox. The film is set in ad 2200. On the planet Altair Four a Prospero-like Dr Morbius (with his Miranda-like daughter Altaira) unleashes uncontrollable monstrous forces, apparently from his own id. The rock musical Return to the Forbidden Planet (1981) develops this.

Tom Matheson

‘For Bonny sweet Robin is all my joy’, snatch of a ballad sung by Ophelia in Hamlet 4.5.185. The tune, under a variety of titles with the word ‘Robin’, survives in many arrangements from the period.

Jeremy Barlow

Ford, Master Frank. He tests his wife by bribing Falstaff to woo her (having taken the name Brooke (Broome in the *First Folio) to conceal his identity) in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Anne Button

Ford, Mistress Alice. With Mistress Page she devises a punishment for Falstaff, after they find he has sent them identical love letters, in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Anne Button

Fordham, John. See Ely, Bishop of.

foreign words. The renaissance of learning in 16th-century England led to the enrichment of the English vocabulary with foreign words largely introduced from classical sources (often in Anglicized form) via translations from Latin and French literary and scientific texts. Because of the association of Latin with scholarship, unusual Latin loans became known as ‘inkhorn’ terms, whose introduction was strongly supported by some, like Sir Thomas Elyot (1490–1546), and opposed by others, like Sir John Cheke (1514–57). Shakespeare employed their misuse by lower-class speakers, like Dogberry, and their excessive use by courtly speakers, like Osric, as sources of humour and satire.

Vivian Salmon

forestage, another name for an apron stage, or an extension to an apron stage.

Gabriel Egan

forgery, the practice of counterfeiting an author’s personal documents or works; specifically in the case of Shakespeare, counterfeiting his signature, manuscripts of his plays and poems, annotations in printed copies of his works, and historical and theatrical documents pertaining to his career.