Othello

Shakespeare’s claustrophobic tragedy of jealousy and slander belongs to the same period of his career as three plays with equally dark views of sexuality, Troilus and Cressida, Measure for Measure, and All’s Well That Ends Well: it is close in its use of rare vocabulary to the former tragedy, and similar in its versification to the two comedies. According to the *Revels accounts, it was acted at court in November 1604, and it is apparently echoed in a play by Thomas *Dekker and Thomas *Middleton, 1 The Honest Whore, composed in the same year. It is just possible that Othello was already in the King’s Company’s touring repertoire towards the end of 1603 (some commentators find echoes of its phrasing in the 1603 quarto of Hamlet, a reported text compiled by an actor perhaps influenced by recollections of Othello), but it seems likeliest that the play was composed in late 1603–4 and first acted in 1604, especially since its account of the Turkish navy is informed by Richard Knolles’s History of the Turks, published only in autumn 1603.

Text: The play first appeared in quarto in 1622, and reappeared in the Folio the following year. The differences between these two texts make Othello one of the most complicated plays to edit in the canon, and they are compounded by the fact that both seem to have been set from manuscripts that had already been transcribed by fairly independent-minded scribes. The quarto, the only Shakespearian quarto divided into acts, seems to derive from a presentation copy of the play prepared from Shakespeare’s *foul papers by a scribe who sometimes had trouble making sense of their details, and who sometimes intervened to expand and clarify stage directions for the benefit of readers. The Folio text, 160 lines longer and different in wording at over 1,000 points, seems to have been set from a later manuscript incorporating Shakespeare’s subsequent revisions, prepared by an even more intrusive scribe with different tastes. As well as having been expurgated in compliance with the *Act to Restrain the Abuses of Players (1606), the Folio has fewer and less detailed stage directions, and more punctuation, and insists on spelling out in full some words and expressions contracted in the quarto. The Oxford edition, favouring Shakespeare’s revisions, incorporates the new passages found only in the Folio (which include Desdemona’s Willow song, and an increased emphasis on Emilia’s role in the last act), but in other respects follows the unexpurgated and less scribally sophisticated quarto.

Sources: Shakespeare derived most of the plot for Othello from a story in *Cinthio’s Hecatommithi (1565), which he must have read either in the original Italian or in a French translation published in 1584. In this rather squalid prose tale, an ensign lusts after his Moorish captain’s Venetian wife Disdemona, and avenges her rejection of his advances by persuading the Moor that she has committed adultery with his friend, a captain. The ensign substantiates his allegation by stealing a handkerchief from Disdemona while she is fondling her baby, planting it in the captain’s room, and showing the Moor the captain’s wife copying its embroidery. Convinced of his wife’s guilt, the Moor collaborates with the ensign to beat her to death in her chamber with a sand-filled stocking, and they then pull down the ceiling in order to make the murder look like an accident. Disdemona’s relatives, though, learn the truth and eventually kill the Moor in revenge, and the ensign dies horribly under torture. Shakespeare both promoted and ennobled the Moor to create the first black tragic hero in Western literature, though the name he gave him may consciously echo a comedy: in Ben *Jonson’s Every Man in his Humour (1598), the obsessively (and groundlessly) jealous husband is called Thorello (later renamed Kitely when Jonson rewrote the play to set it in London instead of Italy). Shakespeare moved the action to the earliest days of Othello and Desdemona’s marriage, adding the characters of Brabanzio and the gullible disappointed suitor Roderigo, and set this relationship between a Moor and a Venetian against the backdrop of Venice’s wars against the Ottoman Empire. Cyprus was attacked by the Turks in 1570 and fell the following year, but in the play military conflict gives place to marital once the characters reach Cyprus. Exotic details in Othello’s speeches suggest a familiarity with *Pliny’s Natural History (translated by Philemon Holland in 1601): see also travel, trade, and colonialism, moors.

Synopsis: 1.1 The ensign Iago, enraged that the Moorish general Othello has made Cassio his lieutenant instead of him, has Roderigo awaken the Venetian senator Brabanzio and inform him that his daughter Desdemona has eloped with Othello. Horrified, Brabanzio raises a hue and cry.

1.2 Iago, concealing his enmity, warns Othello against Brabanzio’s wrath. Cassio brings Othello a summons to the Duke. Brabanzio arrives with officers, accusing a calm Othello of having seduced his daughter by sorcery: all depart for the palace, Brabanzio confident that the Duke will support him.

1.3 The Duke learns that a hostile Turkish fleet is bound for Cyprus. When Othello arrives the Duke says he must be sent immediately against the Turks, before Brabanzio makes his accusation against the Moor. Sending for Desdemona as a witness, Othello eloquently describes how she fell in love with him when, invited by her father, he related his past military escapades and exotic adventures. Challenged by Brabanzio on her arrival, Desdemona says her first duty is now not to him but to her husband Othello: heartbroken, Brabanzio refuses the Duke’s consolation. The Duke sends Othello to defend Cyprus: neither Brabanzio nor Othello wishes Desdemona to stay at her father’s house during his absence, and she herself insists on accompanying her husband. Othello gives order that she shall travel to Cyprus in the conduct of Iago. Left with Iago, Roderigo despairs of ever enjoying Desdemona, but Iago, promising that her marriage to Othello will prove fragile, urges Roderigo to provide himself with money and come to Cyprus, undertaking to help him cuckold the Moor as part of his own revenge. Alone, Iago speaks of his hatred of Othello and a rumour that the Moor has cuckolded him, and hatches a plan to persuade Othello that his wife is unfaithful with Cassio.

2.1 Montano, governor of Cyprus, awaits news of the Turkish fleet, soon reported to have been wrecked in continuing storms. Cassio arrives from Venice, anxious for the safety of Othello’s ship. Iago, his wife Emilia, Desdemona, and Roderigo arrive on another vessel, and receive a courtly welcome from Cassio. Iago banters misogynistically with Desdemona as she awaits Othello’s arrival, and watches as she speaks with Cassio, certain he can use their friendship to their undoing. Othello arrives and is blissfully reunited with Desdemona before confirming the destruction of the Turkish fleet. Left with Roderigo, Iago tells him Desdemona is in love with Cassio, and outlines a scheme by which this new rival may be discredited: placed in charge of the watch that night, Roderigo will provoke Cassio into a brawl. Alone, Iago claims he too desires Desdemona, to avenge his own alleged cuckolding by Othello, and hopes that by convincing the Moor she is false with Cassio he may enjoy Othello’s favour.

2.2 A herald announces feasting in honour of Othello’s marriage.

2.3 Leaving Cassio in charge, Othello retires to bed with Desdemona. Iago gets Cassio drunk among members of the Cypriot garrison, singing ‘And let me the cannikin clink’ and ‘King Stephen was a worthy peer’. Iago alleges that Cassio is a drunkard, a story apparently confirmed when Cassio drives in Roderigo, who has succeeded in provoking him to fight. Montano tells Cassio he is drunk, and they also fight. An alarm bell summons Othello to quell this brawl: he interrogates the participants, and Iago, feigning to defend Cassio, blames the incident on the lieutenant. Othello cashiers Cassio before leading Desdemona, roused by the fray, back to bed. Alone with Iago, Cassio laments the loss of his reputation: Iago advises him to woo Desdemona to plead for his reinstatement. Alone, Iago reflects with satisfaction on his hypocrisy. A bruised Roderigo arrives, dissatisfied with Iago’s progress on his behalf, and is reassured. Alone again, Iago plans to have his wife advise Desdemona to support Cassio’s suit, and to arrange for Othello to find Cassio soliciting Desdemona.

3.1 The next morning Cassio has musicians play outside Othello’s apartments: they are dismissed by a clown, whom Cassio sends to fetch Emilia. Iago arrives and undertakes to lead Othello away while Cassio speaks with Desdemona. A sympathetic Emilia promises to bring Cassio to her.

3.2 Othello arranges to meet Iago at the citadel.

3.3 Desdemona and Emilia promise Cassio to do all they can to persuade Othello to reinstate him: he takes his leave when he sees Othello and Iago approaching, a departure to which Iago insinuatingly draws Othello’s attention. Desdemona speaks on Cassio’s behalf, but Othello postpones the subject and asks to be left alone for a while. Iago, alone with the Moor, questions him about Cassio’s role in his courtship, and at Othello’s increasingly anxious and impatient promptings suggests that Othello should watch Desdemona carefully lest she be engaged in an affair with Cassio, warning against jealousy, and promising to help Othello investigate the situation. Alone, Othello, trusting Iago’s supposed honesty, is convinced of Desdemona’s infidelity, though when she returns his faith revives: nonetheless he complains of a headache, for which she offers a handkerchief to bind his brow, which he drops. When the troubled couple leave Emilia picks the handkerchief up, recognizing it as Othello’s first gift to Desdemona, for which Iago has been asking, and which she gives him on his return. Iago, alone, plans to leave it in Cassio’s lodging. Othello returns, already visibly distracted with jealousy, and demands that Iago prove the truth of his allegations. Iago claims he has overheard Cassio dreaming of illicit encounters with Desdemona and has seen him with the handkerchief. Othello vows revenge: Iago vows to serve it. Othello commands Iago to kill Cassio and means to kill Desdemona himself.

3.4 Desdemona sends the clown to fetch Cassio. She is troubled about the loss of the handkerchief, which Emilia denies having seen. Othello arrives, and Desdemona tells him she has summoned Cassio: he feigns a cold and asks for the handkerchief. When she says she has lost it he tells her it was magically charmed to ensure the continuance of mutual love, given to his mother by a sorceress, and that its loss is ominous: as his questioning about it grows more urgent, she attempts to change the subject back to Cassio, which enrages him further until he leaves. Desdemona and Emilia are alarmed by this unwonted behaviour. Cassio arrives with Iago, but Desdemona explains that Othello is uncharacteristically vexed and will not hear his suit. Desdemona decides Othello must be anxious about state affairs, and the two women go to seek him. Cassio is accosted by his mistress Bianca, who is suspicious when he asks her to copy the embroidery on Desdemona’s handkerchief, which he has found in his chamber.

4.1 Othello, told by Iago that Cassio has admitted sleeping with Desdemona, falls into a fit. While Iago gloats, Cassio arrives: Iago has him wait nearby. When Othello recovers, Iago hides him where he may watch Cassio talking, as Iago claims, about his liaison with Desdemona: he then converses flippantly with Cassio about the doting Bianca. Othello, watching, is convinced Cassio is laughing about Desdemona, and is even more enraged when he sees Bianca give Cassio back the handkerchief. Alone again with Iago, Othello asks Iago to fetch him poison for Desdemona: Iago persuades him instead to strangle her in bed, and promises to kill Cassio before midnight. Desdemona arrives with Lodovico, a Venetian senator who has brought letters: Othello, with increasing fury, reads that he is to return to Venice, leaving Cassio in his place, and strikes Desdemona. She is leaving in tears, but he calls her back before dismissing her again, eventually storming off himself. Lodovico is astonished.

4.2 Emilia tells Othello Desdemona is innocent, but he dismisses her as a bawd, telling her to keep the door while he speaks with Desdemona. He accuses his wife of whoredom, discounts her denials, and insultingly gives Emilia money as he leaves. Desdemona, weeping, speaks with Iago and Emilia, vowing eternal fidelity despite Othello’s mistreatment. After the women leave, Roderigo comes to accuse Iago of merely leading him on: Iago promises he will soon enjoy Desdemona so long as he is prepared to kill Cassio.

4.3 After supper, Othello, leaving to walk with Lodovico, bids Desdemona prepare for bed and dismiss Emilia. Undressing with Emilia’s help, Desdemona sings the Willow song (‘The poor soul sat sighing by a sycamore tree’). The two women discuss infidelity, which Desdemona can hardly believe any woman would commit: Emilia, however, argues that wives should revenge themselves in kind against unfaithful husbands.

5.1 Iago sets Roderigo on to kill Cassio in the dark, but Cassio wounds Roderigo, and Iago, attacking unseen from behind, is able to wound Cassio only in the leg. Hearing his cries, Othello is satisfied that Cassio is dying and, inspired by Iago’s example, goes to kill Desdemona. Lodovico, with Brabanzio’s brother Graziano, hears the wounded men: Iago, feigning to help, stabs Roderigo, then pretends horror on finding him dead. When Bianca arrives Iago accuses her of being behind the incident, and when Emilia comes he sends her to tell Othello of what has happened.

5.2 Othello comes, with a light, to the sleeping Desdemona and kisses her tenderly, though convinced of her guilt. When she awakens he tells her to pray, as he is about to kill her. Desdemona protests her innocence and that of Cassio, weeping when Othello tells her he is dead: he smothers her and conceals her body behind the bed curtains as Emilia calls for admittance, bringing the dismaying news that Roderigo is dead and Cassio wounded. Desdemona, regaining consciousness, tells Emilia she has been falsely murdered but insists Othello was not her killer before dying. Othello, however, admits killing her, explaining to a horrified Emilia that he did so because he learned from Iago that she had committed adultery with Cassio. Emilia calls for help and confronts Iago, who arrives with Montano and Graziano. Graziano says the sight of Desdemona’s body would drive Brabanzio to despair had he not already died of grief over her marriage. Othello says he saw Cassio with Desdemona’s handkerchief: aghast, Emilia declares how she gave the handkerchief to her husband. Realizing the truth, Othello runs at Iago, but Montano disarms him: Iago stabs Emilia before fleeing, pursued by Montano. Emilia, still reproaching Othello with Desdemona’s innocence, dies. Othello produces another sword and laments over Desdemona’s body, intending suicide. Lodovico, Montano, and a crippled Cassio enter with Iago under guard, whom Othello wounds before being again disarmed: Othello asks forgiveness of Cassio, and asks why Iago has so conspired against him. Iago says he will never speak again. Cassio and Lodovico, with the help of letters found on Roderigo, unravel Iago’s machinations: Lodovico says Othello must be taken to Venice. Othello, however, asking to be remembered fairly, along with his services to the state, stabs himself, just as he once stabbed a Turk who had beaten a Venetian. He dies kissing Desdemona. Lodovico, leaving to report these tragic events in Venice, urges Cassio, now governor of Cyprus, to have Iago tortured to death.

Artistic features: The diction of Othello is unusually polarized between the glamorous, exotic music of the Moor’s poetry and the harsh cynicism of his ensign’s soliloquies: this has contributed to the play’s attractiveness to operatic composers such as *Verdi, who have translated Othello into a tenor and Iago into a baritone. Partly through these soliloquies, Othello exploits *dramatic irony more relentlessly than any other play in the canon, letting us know of ‘honest’ Iago’s treachery from its opening scene onwards but denying that knowledge to the rest of the cast until the final act. The play’s intensity is assisted by the absence of any sub-plot, and by the skill with which Shakespeare compresses the narrative he found in Cinthio: it is this compression which gives rise to the famous ‘double time’ effect, whereby the play’s events seem at once to take place with terrible swiftness over only two or three days (so that there is no time for Othello to realize the truth) and yet to encompass enough time for Iago’s allegations to be plausible.

Critical history: The subject of more 17th-century allusions than any other Shakespeare play except The Tempest, Othello was already established as one of Shakespeare’s greatest achievements long before Thomas *Rymer made his ineffectual attack on it in 1693 (describing it as ‘a bloody farce’, a view which would be developed more sympathetically in W. H. *Auden’s account of Iago’s scheme as a terrible practical joke). Samuel *Johnson and William *Hazlitt alike praised the rich contrasts between its characters and the skill of its design. *Iago influenced *Milton’s dramatization of Satan, and would fascinate the *Romantics, *Coleridge finding in his soliloquies (with their excess of potential rationalizations for his crimes) ‘the motive-hunting of motiveless malignity’. Although some 19th-century Americans (including Joseph Quincy *Adams) found the play’s depiction of interracial marriage objectionable (and even Coleridge refused to see Othello as black, preferring to envisage him as an aristocratic Arab), most 19th-century critics found Othello convincingly noble. It was only in the 20th century, when T. S. *Eliot took issue with A. C. *Bradley’s account of the play, that some began to adopt Iago’s view of Othello as a bombastic self-deceiver. This argument between pro- and anti-Othello factions has now been largely displaced by the discussion of Shakespeare’s attitude to *Moors, and whether Othello’s unquestioning assumption that adulterous wives should die is intended to be seen as confirming the racist views expressed by Brabanzio and Iago. Iago’s interconnected obsessions with class, race, and gender have indeed helped to keep the play central to much current critical discourse, whether *feminist, *Marxist, or *psychoanalytic.

Stage history: The quarto reports that the play was acted at both the *Blackfriars and the *Globe, and an eyewitness account of a performance in Oxford in 1610 confirms the power the play exerted on the Jacobean stage. Still in the repertory through the 1630s, it was revived in unadapted form at the Restoration (so that *Desdemona was one of the first roles to be played by a woman on the English professional stage) and few seasons have gone by without a revival since. Outside the English-speaking world, the play has been especially popular in *Russia. The roles of Desdemona and Iago are discussed elsewhere. Great Othellos have included *Betterton, *Quin, Spranger *Barry, J. P. *Kemble, and Edmund *Kean, whose frightening, animalistic performance in the role was one of his greatest from 1814 until his death (after collapsing onstage in Act 4) in 1833. The American Ira *Aldridge was the first black actor to play Othello, a role he played almost everywhere except in his own country between 1826 and 1865, but the role remained predominantly a blackface one (from *Forrest and *Booth to *Salvini and *Forbes-Robertson) until the advent of Paul *Robeson, who first played it at the *Old Vic in 1930 and last in Stratford in 1958 and whose record-breaking Broadway run in the role in 1943 greatly distressed white supremacists. Laurence *Olivier’s Othello for the *National Theatre in 1963, a magnificent egotist who reverts to barbarism, was in retrospect the last possible flowering of the blackface tradition: non-black actors who have played the role since (such as Anthony Hopkins and Ben *Kingsley) have preferred to make the role less African. Patrick *Stewart even played a white Othello among an otherwise all-black cast in Washington in 1998. Nowadays some black actors refuse the part on the grounds that in making an exotic spectacle of Othello’s blackness the play is innately racist, but it has elicited towering performances from the likes of James Earl *Jones and Willard White, and Janet *Suzman’s production at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg in the late 1980s, with John Kani in the title role, made an eloquent protest against apartheid. The casting of the South African actors Sello Maake ka-Ncube and Sir Antony *Sher—who played Iago as an uncharismatic and sexually warped middle ranking careerist in a Suez-era military setting (RSC, 2004)—summoned an apartheid context, though militarism and psycho-sexual motives were heavily foregrounded to defuse somewhat the play’s racial divisiveness. Nonetheless, the production’s intimate, austere sorrows, heightened by the use of the *Swan space, reconfirmed the deservedness of the play’s particular reputation for inflicting emotional wounds. Nicholas Hytner’s Othello (National, 2013), starring Adrian *Lester and Rory *Kinnear, similarly invested in the significance of the backdrop of war as key to Iago’s mysterious, paranoid hatred, Othello’s jealousy, and, in a world in which soldiers rely on each other for life, the trust between the two men. Summoning Iraq and Afghanistan in a modern army in which women serve alongside men and post-traumatic stress disorder undoes the judgement, it again sought largely to obviate uncomfortable engagement with racially charged motives. The cost was to some ugly and complex questions the play asks, and a certain degree of dramatic irony about ‘honest’ Iago, despite virtuoso performances from both leads.

Michael Dobson, rev. Will Sharpe

On the screen: The most interesting *silent film is the 93-minute German Othello (1922) directed by Dmitri Buchowetzki, with Emil Jannings as the Moor. The four best-known sound cinema films are those made by Orson *Welles (1952) and Sergei Yutkevich (1955), Stuart Burge’s film with Olivier as Othello (1965), and the Othello directed by Oliver Parker (1995). Pre-eminent among those filmed for television are Janet Suzman’s Johannesburg production (1988) and Trevor *Nunn’s RSC production with Willard White as the Moor (1990).

Despite its unimpressive Venice sequences, Welles’s film, with its Moroccan location brilliantly exploited for dramatic contrasts, stands in a class of its own. Yutkevich’s Othello, shot in colour and originally with Russian dialogue, is profoundly memorable for its visual impact, with stone, sea, and sky as elements in the film’s language. Burge’s film of John Dexter’s National Theatre production is historically important for its capturing of Olivier’s immense performance, though his stage projection is somewhat overpowering for the camera. While Jonathan *Miller’s BBC TV Othello (1981) featuring Anthony Hopkins was criticized for its failure to give Othello the necessary dramatic weight, the two stage productions filmed for television focus well on characters other than the Moor. Parker’s Othello was Laurence Fishburne, an American black actor whose portrayal has been seen as capitalizing on the media dramatization of the O. J. Simpson trial. Kenneth *Branagh played Iago. Tim Blake Nelson’s O (2001) starred Mekhi Phifer as Odin James, captain of the school basketball team, and Josh Hartnett as Hugo, the embittered, steroid-addicted son of the team’s coach, overshadowed by James both on court and in his father’s attentions. It engaged the racial tensions of its setting, with Phifer’s James a gifted scholarship athlete and the only black student in a privileged South Carolina private school, needed for his abilities in much the same way as Othello is needed by the state for his. Some critics saw a heavy-handed parallelism at work, and an exploitative grasp at soft-core pornography in the sex scene between Phifer and Julia Stiles’ Desi, in crucial contradiction of the play’s ambiguity on this matter. But their relationship is tender and plausibly drawn, and its descent into violence powerfully affecting.

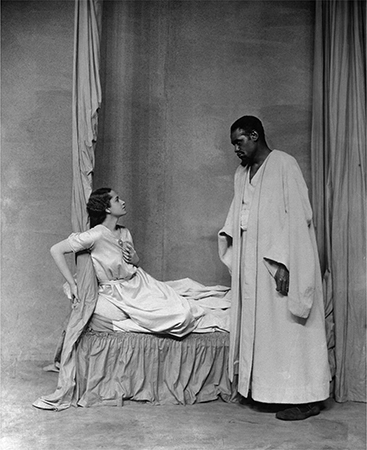

The 23-year-old Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona, with Paul Robeson as Othello, Savoy Theatre 1930.

Anthony Davies, rev. Will Sharpe