k

Kames, Henry Home, Lord (1696–1782), Scottish judge and philosopher. Kames uses Shakespeare as an example of genius in his popular study of moral aesthetics Elements of Criticism (1762). Focusing on universal human nature rather than critical rules, Kames’s work examines how drama arouses emotions and passions in its audiences.

Jean Marsden

Katherine (Catherine; Katharina; Katharine; Kate). (1) For Katherine/Kate, see The Taming of the Shrew. (2) Love’s Labour’s Lost. See Catherine. (3) 1 and 2 Henry IV. See Percy, Lady. (4) Henry V. See Catherine. (5) Queen Katherine/Princess Dowager in All Is True (Henry VIII) (Henry VIII’s first Queen) pleads her case in court, 2.4, but dies shortly after her divorce, 4.2. She is based on Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536), daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, married in 1509 to Henry VIII. Her first four children died in infancy, but her fifth, Mary, lived to become queen.

Anne Button

Kean, Charles (1811–68), English actor-manager, son of the great Edmund *Kean, who sent him to Eton. Plump of figure, facially expressionless, and vocally nasal, Charles Kean was not well endowed to enter the profession in which he was bound to be compared—unfavourably—with his father. Nevertheless, despite or because of the family name, Charles Kean had early opportunities to play Shakespearian leads in London: Romeo (1829), Richard III (1830), Iago (1833) to his father’s Othello, Othello and Hamlet (both 1838); in addition to which he undertook engagements in the provinces and America. Charles Kean’s Shakespeare performances were criticized for ‘clap-trap effects’, misplaced emphases and unceasing—but pointless—locomotion. Nevertheless, in 1848 Queen Victoria appointed Kean director of the Royal Theatricals at Windsor Castle, whither he marshalled fellow thespians to perform before their sovereign in a range of plays old and new in which the works of Shakespeare, who was rapidly assuming the status of national bard, were respectfully represented.

When, in 1851, Kean set up in management at the Princess’s theatre, the Queen’s patronage was undoubtedly highly conducive to attendance by those (upper) classes who had not hitherto considered theatre-going to be a proper activity. The prominence of Shakespeare’s plays in the repertoire was a further inducement especially as they were produced with such painstaking antiquarian accuracy of sets, costumes, and other accoutrements as to constitute lessons in (principally British) history. In the decade of the Great Exhibition, the *Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, and early photography, Kean captured and catered for the public taste for reconstructing and animating the past with all the accuracy that art, antiquarianism, and technology could deploy.

Although Kean did venture to distant places (The Merchant of Venice, Hamlet, The Tempest) and times (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Winter’s Tale), his most ambitious and successful productions were rooted in the homestead of history: King John (1852), Macbeth (1853), All Is True (Henry VIII) (1855 and 1858), Richard II (1858), King Lear (1858), and Henry V (1859). In addition to the historical accuracy of their every facet, these revivals were characterized by large-scale, carefully orchestrated crowd effects (foreshadowing the Saxe-Meiningen company) often in interpolated episodes, such as the entry of Bolingbroke and Richard II into London which Shakespeare was content just to describe, which were accommodated by huge (a third or more) cuts in and rearrangement of the text.

Acting tended to be subservient to scenery, but Kean’s company included his formidable and talented wife Ellen (Tree) and the forthright John Ryder. Of Kean himself G. H. Lewes remarked that he is ‘changing his style to a natural one’. Undoubtedly in the context of his own productions Kean’s performances exceeded his youthful (lack of) promise, notably his sympathetic Richard II. To their intense disappointment the Keans’ unstinting efforts on behalf of their monarch and national dramatist did not result in the hoped-for knighthood, and the couple set off on an exhausting (though remunerative) tour of America and Australia. Thus it was that the Shakespeare tercentenary found the Keans in Melbourne, where they performed four acts, each from a different play: ‘so there’s a hard night’s work’, as Mrs Kean observed.

Richard Foulkes

Kean, Edmund (1787/9–1833), English actor, who pre-eminently gave expression to *Romanticism on the stage. Kean’s parentage and early life are cloaked in mystery. Born and brought up in London, he was evidently something of an infant prodigy, becoming a proficient singer, dancer, fencer, acrobat, and mime. He performed on the legitimate stage as Prince Arthur at Drury Lane (1801), but, save for appearances—Rosencrantz, Polonius, and First Gravedigger—at the Haymarket (1806), spent the next thirteen years in the provinces, including York where he was a youthful Hamlet (1802). Kean resisted the temptation of making his London debut prematurely, but when he played Shylock at Drury Lane on 26 January 1814, he caused a sensation. The Thames was frozen and the vast (3,060) auditorium less than a third full, but from his first appearance the small, swarthy actor electrified the audience. Instead of the red-haired, unkempt, conventional Jew, Kean, in a black wig, cut a presentable figure, who provoked pity and fear as well as loathing and contempt. With each of Shylock’s appearances Kean’s performance grew in power and passion and by curtain-fall that privileged audience knew that—in *Coleridge’s memorial words—‘To see him [Kean] act is like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning.’ The impact of Kean’s performance was heightened by the contrast which it provided with the self-conscious classicism of the *Kembles (especially John Philip), prompting *Hazlitt to write (1816) that Kean had ‘destroyed the Kemble religion…in which we were brought up’.

Kean was fortunate in his chroniclers—Hazlitt, Leigh *Hunt, Coleridge, and *Keats—who, as well as being aficionados of the finer points of performance, were in sympathy with his radical—Romantic—style. When Hazlitt returned to Drury Lane on 15 February to see Kean as Richard III, he was again struck by the actor’s originality (‘it is entirely his own, without any traces of imitation’), the animation and vigour which he brought to the role in which ‘He filled every part of the stage.’ With Hamlet, a month later, Kean was departing from the vein of energetic malignity which had characterized his Drury Lane performances to date, but though Hazlitt considered him ‘too strong and pointed’ for the pensive Prince, he nevertheless commended the ingenuity of his interpretation and the ‘tone of fine, clear and natural recitation’ in which he executed the major speeches, judging overall that ‘To point out the defects of Mr. Kean’s performance of the part, is a less grateful but a much shorter task than to enumerate the many striking beauties which he gave to it, both by the power of his action and by the true feeling of nature.’

Although Kean had added the melancholy Dane to his credits, it was with roles rather more in tune with his own restless, mercurial, arrogant—and increasingly alcoholic—disposition that he consolidated his success. In Othello and Iago—both at Drury Lane in 1814—his ‘deficiency of dignity’ in the former was offset by his instinctive delicacy and in the latter he added to his portraits of restless malignity. Though his early experience had equipped him to do so, Kean did not include comedy in his mature repertoire; nevetheless, he invested some of his serious (villainous) roles with humour. Kean continued to create more Shakespeare roles. He was a rather disappointing Romeo and Macbeth, and an improbable Richard II. He reclaimed Timon of Athens, whose paroxysms he took beyond the bounds of nature; Richard, Duke of York, in an adaptation of 1–3 Henry VI; and Posthumus (surprisingly in preference to Iachimo), along with King John, Hotspur, Coriolanus, Cardinal Wolsey, and (belatedly—in 1830—and uncomfortably) Henry V.

In June 1820, following the death of King George III, during whose prolonged period of mental instability the play had not been performed, Kean assumed the title role in King Lear. Hazlitt found that ‘the gigantic, outspread sorrows’ of Lear seemed to ‘elude his [Kean’s] grasp, and baffle his comprehension’, whereas he rose to the intensity of passion in the curse of Goneril, achieving ‘the only moment worthy of himself, and the character’.

Kean’s increasingly dissolute private life inevitably had a deleterious effect on his stage work. He toured America in 1820 and in 1825, following the scandal—and trial—arising from his affair with Charlotte Cox, whose husband was an alderman and member of the Drury Lane committee. On his return from America Kean played at Covent Garden, but it was back at Drury Lane that he recovered some of his former brio as Othello to the Iago of his, now formidable, rival *Macready in 1832. The following year he gave what was to be his last performance as Othello to his son Charles’s Iago. As he collapsed he moaned, ‘I am dying—speak to them for me.’

Edmund Kean as Richard III, 1814; characteristically, the moment Cruikshank has chosen to illustrate is a convincingly abrupt start. ‘To see him act is like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning,’ claimed Coleridge.

Richard Foulkes

Keats, John (1795–1821), English poet. Keats is best known in this context for his celebration (after *Hazlitt) in his letters and marginalia of a Shakespeare of protean sympathies, generous redundancy of imagination, and natural feeling, declared the epitome of ‘negative capability’—a ‘chameleon’ poetic stance which he contrasted to the egotistical *Milton and *Wordsworth and to which he himself aspired.

Nicola Watson

Keeling, Captain William (d. 1620), naval commander. According to an addition to the journals of an early East India Company voyage, the crew of Keeling’s ship the Red Dragon performed Hamlet and Richard II in 1607 and 1608; but the document in question is now widely believed to be a *forgery by J. Payne *Collier.

Park Honan

keepers, Mortimer’s. They accompany the imprisoned *Mortimer, 1 Henry VI 2.5.

Anne Button

Kemble, Charles (1775–1854), English actor, manager, and playwright, and the younger brother of Sarah *Siddons and John Philip *Kemble. His first named role was Orlando in Sheffield and he played the provinces until his 1794 London debut at Drury Lane as Malcolm to his brother’s Macbeth. After a succession of minor roles he joined Covent Garden in 1803 and played Romeo but toured at home and abroad (including opening the new theatre at Brighton playing Hamlet to his wife’s Ophelia) to escape the ‘younger Kemble’ tag. His greatest success came on his return to Covent Garden, particularly from 1820 when he became a shareholder, and he staged intelligent productions of Macbeth, Julius Caesar, 1 Henry IV, and a memorable King John with historically accurate costumes by Planché. Popular performances with his daughter Fanny helped relieve the financial difficulties of management. He took the company to Paris, and in 1832 made a successful tour of North America playing Hamlet, Romeo, Benedick, and Falconbridge. He retired from the stage in 1836 with a further performance of Benedick opposite Helen Faucit’s Beatrice, was persuaded to return briefly to perform for Queen Victoria, and continued to give Shakespeare readings.

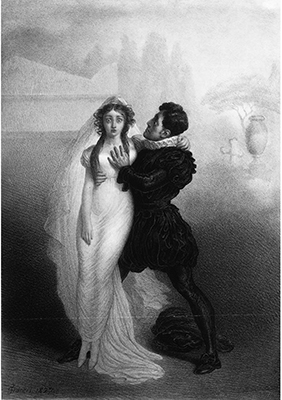

Charles Kemble as Romeo with Harriet Smithson as Juliet in the tomb scene, Paris, 1827. The composer Berlioz became obsessed with Smithson after seeing this production and later married her.

Catherine Alexander

Kemble, Fanny (Frances Anne) (1809–93), English actress, who made her debut as Juliet under her father Charles’s—ailing—management at Covent Garden on 5 October 1829. With no previous professional experience and just three weeks’ rehearsal the young actress relied on her emotional identification with the character rather than technique. Within two years of her triumph as Juliet, Fanny played Lady Macbeth, Portia, Beatrice, and Constance. During her 1832–3 American tour her father played opposite her as Romeo. Following her ill-fated marriage, Fanny returned to the stage in 1847, appearing as Desdemona with Macready in 1848, but thereafter she devoted herself to performing her Shakespearian readings on both sides of the Atlantic. The author of a play—Francis I, 1832—on the Shakespearian model, Fanny produced multiple volumes of memoirs and has attracted several biographers.

Richard Foulkes

Kemble, John Philip (1757–1823), English actor, manager, and playwright, the son of provincial theatre manager Roger Kemble, and brother of Charles *Kemble and Sarah *Siddons. He began to train for the priesthood at Douai but left in 1775 to become an actor, first joining a travelling company and then playing provincial theatres: he appeared as Othello to Siddons’s Desdemona at Liverpool in 1778. That year he wrote to Tate Wilkinson, appending a list of the 68 roles in tragedies and 58 in comedies that he was able to play, and was employed to perform in the north-east. During his time with Wilkinson he wrote his first Shakespearian adaptation (28 more would follow): Oh! It’s Impossible, a version of The Comedy of Errors. After appearing with Daly’s company in Dublin he made his London debut at Drury Lane in 1783 playing Hamlet, shortly followed by Richard III and Shylock. From 1785 he appeared regularly opposite his sister: Othello to her Desdemona, Macbeth to Lady Macbeth, Posthumus to Imogen, Mark Antony to Cleopatra, and Lear to Cordelia.

His work was characterized by research and thorough preparation, leading to suggestions that some of his roles were too studious—and he was certainly less successful in romance and comedy—but such study effectively informed his Macbeth Reconsidered; an Essay: Intended as an Answer to Part of the Remarks on Some of the Characters of Shakespeare (1786), dedicated to Edmond *Malone and written as a response to Thomas Whately’s Remarks on Some of the Characters of Shakespeare which claimed that Macbeth was a coward.

In 1788 he took over the management at Drury Lane and his great success as Coriolanus (with Sarah as Volumnia) led to his enduring identification with Roman roles. He opened the new theatre at Drury Lane in 1794 with Macbeth, extending his reputation for authenticity, stage effects, and a visual playing style (largely earned from the processions and tableaux of his 1788 All Is True (Henry VIII) ) with crowds of flying witches and a full, loud orchestra. In 1803 he became the manager of Covent Garden and extended its Shakespearian repertoire, playing Wolsey, Prospero, Iago, Valentine, and Macbeth. Many of his great roles were recorded in paint, most famously in the portraits by Lawrence. He retired from the stage in 1817 with a final performance as Coriolanus, widely respected as a great tragedian and as *Garrick’s successor in the promotion and playing of Shakespeare.

Catherine Alexander

Kempe (Kemp), William (d. 1603), comic actor (Leicester’s Men 1585–6, Strange’s Men 1592, Chamberlain’s Men 1594–9). Kempe’s fame grew in the late 1580s and early 1590s from his work with Leicester’s and then Strange’s Men. Richard Tarlton established the improvisational clowning tradition which Kempe inherited and refined although his particular skill was in dancing and playing musical instruments rather than mockery and he wrote a number of highly popular *jigs. Kempe’s name appears in a stage direction in the 1599 quarto of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet where we should expect Peter and in the speech prefixes of the 1600 quarto of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing where we should expect Dogberry, so we may be confident that he took these roles. Other roles are speculative but David Wiles saw Kempe’s style in the Clown in Titus Andronicus, Lance in The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Costard in Love’s Labour’s Lost, Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Lancelot in The Merchant of Venice, and, his acme, Falstaff in the Henry IV plays and in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

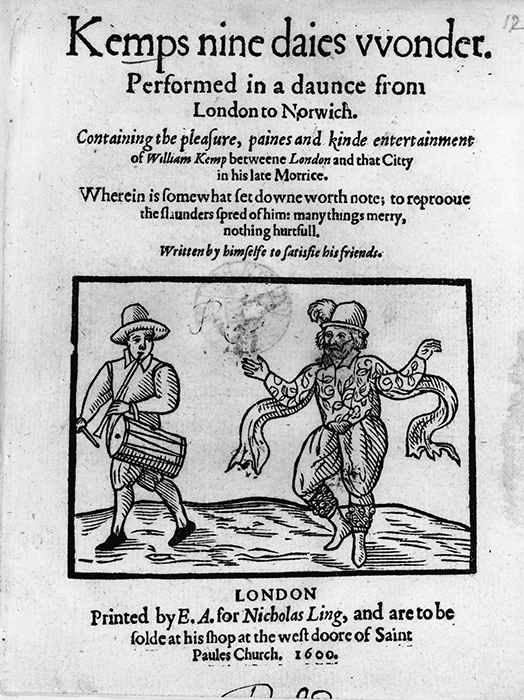

Kempe sold his *Globe share soon after the building was complete in 1599 and early in 1600 he demonstrated his extraordinary endurance by *morris dancing from London to Norwich, a feat he described in his pamphlet Kempe’s Nine Days Wonder. It is not clear why Kempe left the King’s Men, but the mocking of his style of clowning in The Return to Parnassus and Hamlet’s demand that clowns should ‘speak no more than is set down for them’ (3.2.39) suggest that improvisation became unfashionable. Robert *Armin replaced Kempe as the Chamberlain’s Men’s clown and after a continental sojourn in 1601 Kempe was acting with Worcester’s Men at the Boar’s Head and the *Rose in 1602. Thereafter Kempe disappears from records until the burial of ‘Kempe a man’ at St Saviour’s.

The title page of Kempe’s Nine Days Wonder (1600), shows the former clown of Shakespeare’s company, certainly the original Dogberry and probably the creator of such roles as Bottom and Falstaff, engaged in his publicity-stunt morris dance from London to Norwich, with his taborer Thomas Sly.

Gabriel Egan

Kenilworth, a town 12 miles (19 km) north-east of Stratford with a splendid castle, now in ruins, where Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, entertained Queen Elizabeth for nineteen days in 1575. It has been speculated that Shakespeare’s father took him to see the elaborate entertainments, and that the presentation of Arion in a water pageant suggested allusions in Twelfth Night (1.2.14) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2.1.149–54).

Robert Bearman

Kenrick, William (?1725–1779), notoriously acerbic hack writer and reviewer for the Monthly Review. Kenrick viciously attacked Samuel *Johnson’s edition of Shakespeare and subsequently lost his job. He also wrote Falstaff’s Wedding, a comic sequel to Henry IV performed once at Drury Lane in 1766.

Jean Marsden

Kent, the English county, is mentioned in some of the history plays: in The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI) it is where the rebel *Cade comes from and where he meets his end. Its prominence in King Lear may be related to the fact that Kent retained different inheritance laws from the rest of England, dividing estates between all the testator’s children instead of passing the whole to the eldest son.

Anne Button

Kent, Earl of. Banished by Lear, he is taken back into his service disguised under the name of ‘Caius’ (see The History of King Lear 24.278 and The Tragedy of King Lear 5.3.259).

Anne Button

Keysar, Robert (fl. 1605–19), a goldsmith and financier who bought an interest in the Children of the Queen’s Revels in 1605 and later managed the company. They originally acted at the *Blackfriars, and in 1610 Keysar initiated an action against *Burbage and other members of the King’s Men alleging that the theatre had been transferred without his agreement and claiming a share of their profits.

Stanley Wells

Killigrew, Thomas (1612–81), actor, dramatist, and manager. A strong supporter of the Royalist cause, at the Restoration he was awarded one of the two royal patents giving exclusive rights to form an acting company and build a theatre. In choosing a group of actors who had been active before the Civil War, acquiring the rights to plays performed by the old King’s Company pre-1642, and in the bare staging style he adopted at his first venue, the Tennis Court in Vere Street, he was less successful than his forward-looking rival William *Davenant. In 1663 his King’s Company moved to the new Theatre Royal (rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren after a fire in 1672). Despite having exclusive rights to perform 20 Shakespeare plays, in the period to 1682, when it was joined by the Duke’s Company, it produced only four: Othello, 1 Henry IV, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and Julius Caesar.

Catherine Alexander

King, Thomas (1730–1805), English actor. Drury Lane’s principal comedian, he played *Garrick’s foppish foil at the *Stratford Jubilee and in the London version processed as Touchstone, the role in which he was later painted by Zoffany.

Catherine Alexander

‘King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid’, a ballad title mentioned in several plays, including Love’s Labour’s Lost 4.1.65; Romeo and Juliet 2.1.14; Richard II 5.3.78; 2 Henry IV 5.3.103.

Jeremy Barlow

King Henry IV Part 1. See centre section.

King Henry IV Part 2. See centre section.

King Henry V. See centre section.

King Henry the Fifth; or The Conquest of France by the English. Aaron Hill’s adaptation of Henry V, first acted in 1723, keeps the battle of Agincourt offstage (it is narrated in song by the Genius of England) and replaces Pistol and his associates with a new, romantic sub-plot. King Harry’s spurned ex-mistress Harriet, niece of the conspirator Scroop, acts as his go-between to Princess Catherine while disguised as a page before finally stabbing herself in despair.

Michael Dobson

King Henry VI Part 1. See centre section.

King Henry VI Part 2. See centre section.

King Henry VI Part 3. See centre section.

King Henry VIII. See centre section.

King James Bible. The occasionally expressed popular belief that Shakespeare must have helped prepare the translation of the *Bible completed for King James in 1610 is based solely on the circumstance that a few famous passages from that translation and from Shakespeare’s tragedies are the only specimens of Jacobean English most people ever hear. Rudyard Kipling, however, composed a whimsical short story, Proofs of Holy Writ, in which one of the translators consults Shakespeare and *Jonson, and in 1970 Anthony *Burgess pointed out that in the King James Bible the 46th word of the 46th psalm, translated in Shakespeare’s 46th year, is ‘shake’, while the 46th word from the end (if one cheats by leaving out the last, cadential word, ‘selah’), is ‘spear’. Burgess was not rash enough to make anything of this coincidence, however.

Michael Dobson

King Leir, an anonymous verse drama of the early 1590s, and the most important source for Shakespeare’s King Lear. The play is a romance chronicle with a happy ending, and it was in existence by April 1594. It was printed in 1605 as The True Chronicle History of King Leir and his Three Daughters, a year before Shakespeare’s King Lear was first performed at Whitehall on 26 December 1606.

Shakespeare’s use of King Leir is instructive in a number of ways. Among the more noteworthy changes are his conflating two of the source’s characters into the plain-speaking Kent, giving the name Oswald to its villainous Messenger, and, above all, introducing the Fool and having Cordelia die in the play. Leir’s ‘I am as kind as is the Pellican’ (512) anticipates the ‘pelican daughters’ in King Lear, and at times Shakespeare appears to conduct a seamless cross-textual dialogue with the source, as in his casual reference to ‘thy mother’s tomb’, an echo of the funeral of Leir’s wife which opens the source play.

René Weis

King Richard II. See centre section.

King Richard III. See centre section.

King’s Company, formed by Thomas Killigrew, one of the two companies granted a patent by Charles II at the Restoration in 1660. Performing initially at the Red Bull and moving into the new Theatre Royal in Drury Lane in 1663, it acquired the rights to the Shakespearian plays performed by the old King’s Men pre-1642 and included actors from the old company.

Catherine Alexander

Kingsley, Sir Ben (b. 1943), British stage and screen actor. The son of an English-educated Gujarati father, he won international fame in the film Ghandi (1980). His association with the *Royal Shakespeare Company began in 1970 with Peter *Brook’s seminal A Midsummer Night’s Dream and he was the Prince in Buzz *Goodbody’s revelatory studio production of Hamlet. He returned to the RSC in 1988 to play Othello as a North African Arab and was Feste in Trevor *Nunn’s film Twelfth Night (1996).

Michael Jamieson

King’s Men. See Chamberlain’s Men/King’s Men.

‘King Stephen was and a worthy peer’, sung by Iago in Othello 2.3.82. His last line, ‘Then take thy auld cloak about thee’, is the title of a Scots ballad with related words; Sternfeld’s Music in Shakespeare Tragedy (1964) gives the tune.

Jeremy Barlow

Kinnear, Rory (b.1978), son of beloved British character actor Roy Kinnear and godson to Dame Judi *Dench. The younger Kinnear has made a name for himself in his own right as an accomplished Shakespearian actor, chiefly for his work at the *National Theatre as Hamlet (2010) and Iago (2012) in artistic director Nicholas *Hytner’s productions.

Erin Sullivan

Kinoshita, Junji (1914–2006), Japanese writer. Kinoshita majored in English at the University of Tokyo, and became a successful playwright in the 1940s. Many of his plays deal with subjects with socio-political relevance, and his translations of Shakespeare can be best understood as conscientious attempts to reproduce the energy of the original in a language with entirely different linguistic principles.

Tetsuo Kishi

Kirkman, Francis See drolls.

Kittredge, G. L. (1860–1941), American scholar. The one-volume edition of the Complete Works by G. L. Kittredge published in 1936 by Ginn and Co., Boston, was eagerly welcomed. It was based on a fresh collation of the early printed texts, and retained stage directions found in quartos and the *First Folio, printing added directions and scene locations in square brackets. Brief introductions preface each text, which is printed in double columns on the page, and there is a full glossary at the end of the book. Kittredge also published over a period of some years separate annotated editions of some of the plays, and these were gathered by A. C. Sprague in Sixteen Plays of Shakespeare issued by Ginn in 1946. Kittredge’s learned notes on the plays still repay attention, and they are notable for his concern about the sequence and timing of scenes and other problems of staging them.

R. A. Foakes

Kneller, Sir Godfrey (?1649–1723), German painter active in England 1674–1723. He produced a full-length portrait of Shakespeare, a copy of which was presented to the poet and dramatist John *Dryden.

Catherine Tite

Knight, Charles (1791–1873), English publisher, editor, and author. Knight, himself largely self-taught, was an indefatigable promoter of useful general knowledge in the 1830s and 1840s, through a series of weekly magazines. A founding member of the Shakespeare Society (1840), he published his Pictorial Shakespeare in weekly illustrated parts (1838–41) and his Library Edition (12 vols., 1842–4). Knight was the first to point out the extent of Anne *Hathaway’s dower rights as a widow in Shakespeare’s estate, even without specific acknowledgement in the *will. His own library, bequeathed to the City of Birmingham, forms the basis of a major Shakespeare collection.

Tom Matheson

Knight, G(eorge) Wilson (1897–1985), leading mid-20th-century English Shakespeare critic who helped pioneer ‘spatial’ or *imagery-based study in the 1930s in a development closely connected with the contemporaneous literary *modernism of T. S. *Eliot. Knight is best remembered for his books of ‘interpretation’ of Shakespeare plays (he thought the term ‘criticism’ implied an ill-suited judgemental approach to art and avoided the term) in which he developed his interpretative method in exuberant, impressionistic essays on the poetic images and symbols seen as forming unified patterns central to the meaning of the individual plays. He was widely read and imitated in mid-century North America and the UK. Most influential of his books were: The Wheel of Fire: Interpretations of Shakespeare’s Tragedy (1930); The Imperial Theme: Further Interpretations of Shakespeare’s Tragedies (1931); and The Crown of Life: Essays in Interpretation of Shakespeare’s Final Plays (1947). He wrote several other books on Shakespeare and other literary figures, increasingly influenced in his later works by a belief in Spiritualism and communication with his dead brother.

Hugh Grady

knights, five. They are *Thaisa’s suitors, Pericles 6, 7, and 9.

Anne Button

Knights, L(ionel) C(harles) (1906–97), English academic. His polemical How Many Children Had Lady Macbeth? (1933) seeks to discredit A. C. *Bradley’s extra-textual speculations. Shakespeare’s Politics (British Academy Lecture, 1957), Some Shakespearean Themes (1959), and An Approach to Hamlet (1960) demonstrate the evaluative approach to literature and society associated with the Scrutiny critic F. R. *Leavis.

Tom Matheson

knights, six. Three accompany Arcite and three Palamon, The Two Noble Kinsmen, Act 5.

Anne Button

Knolles, Richard (?1550–1610), author of The General History of the Turks (1603). This 1,000-page work provides details of the Venetian–Turkish wars which are the backdrop to Othello, while Knolles’s story of Basso Ionuses, who murdered his wife Manto through irrational jealousy, is a possible precursor for Othello’s plot.

Cathy Shrank

Knyvet (Knevet), Charles. See Surveyor, Buckingham’s.

Komisarjevsky, Theodore (1882–1954), Russian director, designer, and author. Born Fyodor Komissarzhevsy in Venice, the half-brother of the actress Vera Komissarzhevskaya, he worked in the Russian avant-garde or synthetic style at important theatres in St Petersburg and Moscow until he emigrated in 1919. Thereafter he directed widely in England and Europe, becoming known especially as an interpreter of Russian plays (and becoming the second husband of Peggy *Ashcroft). Invited to Stratford by W. Bridges-Adams, he directed and designed a series of fanciful productions of Shakespeare that despite their outrageousness were much admired. The Merchant of Venice in 1932 showed a tilting view of the city, Macbeth in 1933 used metallic scenery, while The Merry Wives of Windsor in 1935 was treated as a Viennese operetta. King Lear (1936), with Randle Ayrton in the title role, was handled respectfully, though its setting of steep steps was unusual for Stratford. The Comedy of Errors (1938) and The Taming of the Shrew (1939), both exotic and farcical, were his most popular productions. He moved to New York soon afterwards, where he spent the last part of his career.

The advent of designer Shakespeare at Stratford: Theodore Komisarjevsky’s surreally out-of-drawing Venice, his own set design for The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, 1932.

Dennis Kennedy

Korea. Shakespeare made his first appearance in Korea in an anonymous translation (1906), from the Japanese (1871), of Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help (1859). Smiles’s book was partially translated under the title of ‘Jajoron’ (The Principles of Self-Help) in Joyangbo, a monthly journal, with a view to selecting passages suitable to the spirit of the age, as descriptions of the virtues of perseverance and hard work required for the formation of a new world of enlightenment. In a prologue, Shakespeare was portrayed as the greatest mind of his day who influenced the promotion of English cultural nationalism. He was admired as an exemplary man of discipline who rose to prominence from a humble background. This image of Shakespeare was associated with the moral code of frugality and propriety which the declining Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) was eagerly seeking in order to westernize or modernize the nation in the face of Japanese imperialism.

The treatment of Shakespeare in the 1910s characterized him as a radiant figure of wisdom. A Shakespeare quotation became a resource in cultural discourse and provided a point of reference that reinforced educational and fundamental principles of moral rectitude. A monthly journal Sonyeon (The Youth, 1908–11) was characteristic in employing Shakespeare quotations for didactic and utilitarian purposes. Its use of quotations was bound up with the need to urge young people to stand up to the Japanese occupation.

The first Shakespeare film shown in Korea was Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s Macbeth in 1917. It was with this film that Shakespeare entered the public consciousness. When Shakespeare began to have a public life, however, it was only with educated and politically conscious circles in Seoul. In the 1920s this small group of elite intellectuals were not introduced to Shakespeare’s own words but to translations, via the Japanese, of Mary and Charles *Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, which had been already influential in making the plays known in *Japan. The moral value of, and the lessons to be learned from, the Tales communicated ethical significance in relation to the values of Confucian patriarchal culture. They demonstrated that the narrative and plot elements of Shakespeare were susceptible to transference into Korean sensibility.

The first attempt to translate a Shakespeare play in its entirety was made, via Japanese renderings, by Hyeon Cheol in his Hamlet (1923), which was a compilation of parts he published in 1921–2 as serials in a monthly journal Gaebyeok (Dawn of Civilisation 1920–6). The first theatrical adaptation of Shakespeare was King Lear and his Daughters (1924), a two-act play, designed for girl students. Its provision of a happy ending, après *Tate, was regarded as morally and socially justifiable, and gave the play tones of emotion and sentimentality. It was printed in Sinyeoseong (The New Woman, 1923–34), a monthly journal for female intellectuals.

The first Shakespeare performance in English was the Forum scene (3.2) of Julius Caesar, played by the drama group of Gyeongseong School of Commerce in December 1925. This scene attracted most attention in the 1920s, along with the trial scene in The Merchant of Venice. Their popularity had much to do with the strong current of nationalism and resistance to Japanese colonial rule. The formulation of ‘Geugyesul Yeonguhoe’ (The Theatre Arts Research Association, 1931–8) proved to be a turning point in the history of Shakespearian stage production in Korea. In 1933 it held a Shakespeare Exhibition and staged The Merchant of Venice—The Trial Scene in Joseon Theatre. This event saw the shift in Shakespearian performance from the school or college stage to the public theatre.

Shakespeare provided sources for contemporary popular plays such as Maui Taeja wa Nangnang Gonju (The Crown Prince Maui and Princess Nangnang, 1941), Jamyeong Go (The Self-Tolling Drum, 1946), and Byeol (The Stars, 1948). The stories of Hamlet the prince who couldn’t rule state affairs, and Romeo and Juliet the star-crossed lovers who couldn’t avoid familial enmities, were the most fruitful of Shakespearian themes. They were appropriated to social and political issues during the last years of the Japanese colonial occupation and after the Independence of 1945, when the country was in turmoil due to ideological conflicts between the right and the left. During the Korean War (1950–3) Shakespeare’s tragedies came to the forefront of the theatrical scene. Their astonishing popularity can be interpreted as an intellectual retreat from ideological pigeon-holing to a world of imaginative communings with the tragic characters’ mental processes.

After the war Shakespeare became a subject of serious academic and critical study in universities. The first conferment of a PhD in Shakespeare studies in 1961, the establishment of the Shakespeare Society (Association from 1982) of Korea in 1963, and its journal Shakespeare Review in 1971 were important steps forward in the recognition of Shakespeare’s pre-eminence amongst English-speaking writers. A special landmark was the celebrations marking the quatercentenary of Shakespeare’s birth in 1964. The year witnessed the publication of two different issues of a Korean translation of the complete works—one was done by Kim Jae-Nam, the other by a group of 19 Shakespearian scholars—and the unprecedented popularity of Shakespearian performances. The two translations gained international notice at the First World Shakespeare Congress in 1971, and secured a position for Korea on the elected Executive Committee of the International Shakespeare Association at the Second World Shakespeare Congress in 1976.

Shakespeare scholarship and performance were gradually diffused and adopted into the global sphere. Since the 1990s, together with growing numbers of Shakespearian academics obtaining PhDs from renowned universities in the UK and US, large numbers of theatre companies have been invited to stage Koreanized Shakespeares at international festivals around the world. The most performed productions include Mokwha Repertory Company’s Romeo and Juliet, and Yohangza Theatre Company’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which proudly participated in the *Globe to Globe Festival at Shakespeare’s Globe in 2012, as part of the *World Shakespeare Festival in line with the London Olympic Games.

The National Theatre of Korea has been at the centre of the ongoing process of Korean affiliations with Shakespeare since its official opening production of Wonsullang (Macbeth) in 1950; amongst its innovations are the National Dance Company’s Moorang (Othello) in 1996, the whole theatre musical King Uru (King Lear) (the largest scale Korean Shakespeare involving 103 performers from all resident companies in 2000), the National Theatre Company’s Terrorist Hamlet in 2007, the National Ballet Company’s Romeo and Juliet in 2008, and the National Changgeuk (classical Korean opera) Company’s Romeo and Juliet in 2009. Its global projects include the invitation of Shakespeare’s Globe production of Love’s Labour’s Lost to its First World Festival of National Theatres in 2007, and the screening of the Donmar Warehouse’s Coriolanus and the Royal National Theatre’s King Lear in association with the National Theatre Live programme in 2014. These screenings celebrated Shakespeare’s 450th anniversary and set a record for sales, with all the seats being fully booked within four hours of going on sale. In the 21st century, Korean Shakespeares are firmly established as familiar and welcome contributors to academic and theatrical discourses.

Younglim Han

Kortner, Fritz (1892–1970), Austrian actor and director. In the 1920s he was Richard III in L. Jessner’s expressionist production (1920) and, adopting a more realist style, Hamlet (1926) and Shylock (1927). Returning from emigration during the Third Reich in 1950, he directed numerous impressive Shakespeare productions, mainly in Munich and Berlin. He last played Shylock on television (1969).

Werner Habicht

Kott, Jan (1914–2001), Polish critic. Shakespeare our Contemporary (1964) invigorated popular attitudes with a Shakespeare to be performed and spoken of in the same terms as Bertolt *Brecht or Samuel *Beckett. In some respects journalistic, the book presented a ‘cruel and true’ playwright who might have experienced the political oppressions and military conflicts of the 20th century.

Tom Matheson

Kozintsev, Grigori (1905–73), Russian film director. He made Hamlet (1964) and King Lear (1971), monochrome films which articulate the dramatic substance of the plays through a uniquely imaginative cinematic language. He is also known for his books Shakespeare, Time and Conscience (1967) and King Lear, The Space of Tragedy (1977).

Anthony Davies

Krauss, Werner (1884–1959), German actor, famous for his intense characterization. In Berlin he played Shylock (in Max *Reinhardt’s production, 1921) and Richard III (1936). He starred in the Nazi propaganda film Jud Süss, and his Shylock in Vienna (1943) was notoriously and predictably anti-Semitic.

Werner Habicht

Kurosawa, Akira (1910–98), Japanese film director, whose films include Kumonosu Djo (The Castle of the Spider’s Web, also known as Throne of Blood, 1957), based on Macbeth, and Ran, based on King Lear (1985). In both, the dramatic structure of the source plays is closely followed. His The Bad Sleep Well (1960) has looser affinities with Hamlet.

Anthony Davies

Kuwait The main Shakespearian adaptations are the work of Sulayman Al-Bassam, a talented Anglo-Kuwaiti director. After writing Hamlet in Kuwait, which was first performed in the country of its title, and another adaptation called The Arab League Hamlet presented in *Tunisia, Al-Bassam came out with a third version, The Al-Hamlet Summit. This play may be considered as a landmark in the history of *Arab theatre. Its success, mainly in Europe, has been due to its political allusions to contemporary events and specific situations brought to a highly grotesque degree, yet clearly referring to the Arab Middle East countries. Performed by the director’s London-based company, Zaoum Theatre, it has been awarded several international prizes since its premiere in Edinburgh in 2002, including the Edinburgh Fringe First Award for innovation in writing and directing, as well as the Best Performance and Best Director Awards from the 2002 Cairo International Festival of Experimental Theatre.

Rafik Darragi

Kyd, Thomas (1558–94), dramatist. Little is known about Kyd’s life except that it ended badly. He was arrested in 1593 on suspicion of fostering xenophobia in London. Heretical papers were found among his possessions, which he said belonged to his former room-mate Christopher *Marlowe. He was imprisoned and tortured, and died not long after his release. In the preface to Robert *Greene’s Menaphon (1589), Thomas *Nashe hints that Kyd had written a play called Hamlet, now lost (and now known as the *‘ur-Hamlet’), but presumed to have been a source of Shakespeare’s play. Kyd also wrote Soliman and Perseda (c.1592), and translated a French neoclassical tragedy, Cornelia (1594). But his fame rests on just one dramatic achievement, The Spanish Tragedy (1592). This was perhaps the most influential tragedy of its time. It was printed at least ten times between 1592 and 1633, was mentioned more often in English plays than any of its competitors, and was popular on the Continent throughout the 17th century. It initiated a vogue for revenge theatre that lasted for decades, and it shares many elements with the greatest of all revenge tragedies, Hamlet.

Like Hamlet, The Spanish Tragedy opens with a ghost calling for retribution. The chief revenger is a father, Hieronimo, who has lost his son. Like Hamlet he is driven mad by his inability to get justice for his relative’s murder, and at one stage contemplates suicide as an escape from his impasse. Hieronimo’s wife too goes mad, like Ophelia, and kills herself amid a riot of devastated plants. The instrument Hieronimo finally chooses for his revenge is a play-within-a-play, anticipating Hamlet’s ‘Mousetrap’. He persuades the murderers to take part in his production, each of them speaking his part in a different language, and the cacophony that results graphically illustrates the terminal breakdown of communication in the Spanish court. In the course of the performance the murderers are murdered. Afterwards Hieronimo explains what has happened, then bites out his tongue to prevent the Spanish authorities from forcing him to change his story. The play ends when Hieronimo commits suicide with a penknife. In the process he asserts his right to narrate his own history more effectively than Hamlet, who left his best friend to tell the tale instead of telling it himself.

The most popular part of the tragedy seems to have been the section in which Hieronimo runs mad. Ben *Jonson was paid by Philip *Henslowe to write ‘additions to Hieronimo’, and these were thought for a long time to be the new mad scenes printed in the 1602 edition of the play, which amount to some 350 extra lines across five separate additions. There is, however, a burgeoning weight of acceptance, based on detailed stylistic analyses, that Shakespeare is the most likely of all Renaissance dramatists to have written these passages, albeit the question is not resolved. Douglas Bruster compared the orthographic features of the passages with what is known of Shakespeare’s idiosyncratic spelling habits to push the case further. Despite an uneven quality the passages are very powerful at their best, although for them and for the question of Shakespeare’s involvement more broadly to eclipse the play would be an undoubted injustice. Something about Hieronimo’s frustrated quest for justice left an indelible mark on Kyd’s first audiences, and to watch or read The Spanish Tragedy is to encounter one of the seminal texts of the early modern theatre.

Robert Maslen, rev.Will Sharpe

Kynaston, Edward (?1643–1712), actor. He was recruited at the Restoration to play women’s roles and was an outstanding female impersonator, praised for his prettiness by Samuel *Pepys. He became a leading actor–shareholder of the King’s Company until its amalgamation with Duke’s in 1682, and for the new United Company was successful in male roles including Antony (in Julius Caesar) and Clarence.

Catherine Alexander