Romeo and Juliet

Shakespeare composed his definitive version of what is often called ‘the greatest love story ever told’ during the lyrical period of his career which also produced Richard II and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, probably in the same year as these two plays, 1595. The play first appeared in print in 1597, in an unlicensed quarto edition apparently produced from a *reported text assembled by actors who had played Romeo and Paris. The title page proclaims that Romeo and Juliet has ‘been often (with great applause) played publicly, by the Right Honourable Lord Hunsdon his servants’: since Shakespeare’s company was renamed the Lord Chamberlain’s Men as of 17 March 1597, this edition must have gone to press before then. Furthermore, the work of producing it was interrupted by the seizure of its original printer’s presses, an event which took place between 9 February and 27 March 1597, by which time the first four sheets had already been printed. Allowing time for the play’s reportedly numerous performances and the compilation from memory of the manuscript, Romeo and Juliet could not very well have been written before late 1596. Its influence on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, particularly visible in the changes Shakespeare made to his source for ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’, would place it just before that play. In any event the play cannot be earlier than 1593, since it shows the influence of English translations of two poems by Du Bartas only published in that year (in John Eliot’s Ortho-Epia Gallica). The dating of Romeo and Juliet to 1595 is perhaps confirmed by the Nurse’s remark that ‘’Tis since the earthquake now eleven years’ (1.3.25), which may be a topical allusion to the earthquake which shook England in 1584.

Text: A second quarto, which calls the play The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, appeared in 1599, fuller and more reliable than the first: its variations in speech-prefixes, permissive stage directions, and accidental preservations of deleted false starts show that it was produced from Shakespeare’s rough draft of the play, which its compositors, unfortunately, had trouble deciphering, sometimes resorting to the illicit first quarto for guidance. This edition was reprinted in 1609, 1623, and 1637, and a copy of the 1609 reprint served as the basis for the text published in the Folio in 1623, though some improvements to speech prefixes and stage directions suggest that this copy had been annotated by reference to a promptbook. Most recent editions of the play are based on the second quarto, but supplement it by reference both to the first quarto and to the Folio, particularly over details of staging.

Sources: Although it is undeniably more romantic to pretend that Shakespeare either made up the plot of Romeo and Juliet or transcribed it more or less directly from his own experience (as did the popular film Shakespeare in Love), the story of Verona’s star-crossed couple had been popular throughout Europe for half a century before Shakespeare’s dramatization. Tales of unfortunate aristocratic lovers proliferated in the Italian Renaissance: one early anticipation of the Romeo and Juliet story is that by Masuccio Salernitano, published in Il novellino (1474), but the first to use the names Romeo and Giulietta, and to set the tale in Verona against the backdrop of a feud between Montagues and Capulets, is Luigi da Porto’s Istoria novellamente ritrovata di due nobile amanti (1535). This story was adapted by *Bandello, whose version appeared in Le novelle di Bandello (1560): his novella was translated into English in William *Painter’s Palace of Pleasure (1566–7), and was the source of a French version by Pierre Boaisteau, published in *Belleforest’s Histoires tragiques (1559–82).

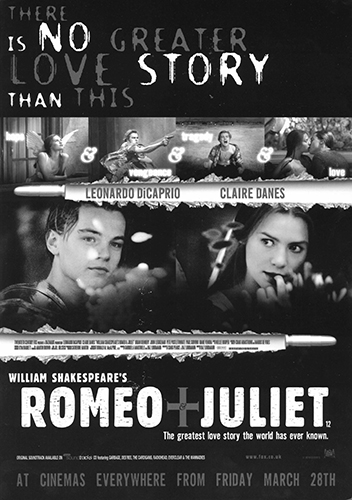

Poster of Baz Luhrman’s sensationally popular film Romeo + Juliet (1996): Shakespeare, allegedly, had never been this sexy.

The French prose tale supplied the basis for Shakespeare’s principal direct source, an English poem by Arthur *Brooke, The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet (1562), which Shakespeare had already used when composing an earlier play with the same setting, The Two Gentlemen of Verona. (Brooke’s preface refers to a now-lost English play on the same subject, but there is no evidence to suggest that Shakespeare knew this dramatic precedent.) Shakespeare follows Brooke’s poem quite closely, retaining the emphasis on fate which Brooke had imitated from *Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, reusing some of Brooke’s imagery, and denying the lovers the last interview in the tomb which they enjoy in most other versions of the story. Shakespeare, however, greatly develops some of the poem’s minor characters—most spectacularly, Mercutio, the Nurse, and Tybalt—and fundamentally alters its perspective. Brooke’s poem is mainly on the side of the lovers’ parents, moralizing against ‘dishonest desire’ and disobedience: his Juliet, for example, is a ‘wily wench’ who takes pleasure in deceiving her mother into thinking she prefers Paris to Romeo, and the lovers’ deaths are represented as righteous punishments for their own sins. As well as returning the story’s principal sympathies to Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare greatly compresses its action, to produce a fast-moving, tightly plotted play (punctuated by urgent references to the passage of time, and formally organized around the three successive interventions of the Prince at 1.1, 3.1, and 5.3) whose events take place over days rather than months. Within this controlled structure, Shakespeare produces some of his most exuberant poetry, for details of which he draws at times on other sources: these include Chaucer’s The Parliament of Fowls for Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech (1.4.53–94), a poem by Guillaume Du Bartas (1544–90) for the discussion of the nightingale and the lark in the ‘aubade’ scene (3.5.1–36), and *Daniel’s Complaint of Rosamond (1592) for Romeo’s description of Juliet’s apparently dead body in the tomb (5.3.92–6).

Synopsis: Prologue: a Chorus outlines the story, requesting a patient hearing.

1.1 Servants of the Capulet family provoke a quarrel with their Montague counterparts, which, with the Capulet Tybalt’s encouragement, develops into a full-scale brawl involving Capulet and Montague themselves, despite attempts by Benvolio, members of the Watch, and the wives of Capulet and Montague to restore order. The fighting is stilled by the arrival of the Prince, who threatens that if the feud breaks out once more Capulet and Montague will be executed. Left with Benvolio, Montague and his wife ask after their absent son Romeo, and employ Benvolio to investigate the cause of his solitary melancholy. Romeo reveals to Benvolio that he is suffering from unrequited love.

1.2 Capulet, bound to the peace, tells the Prince’s kinsman Paris that if he can win his 13-year-old daughter Juliet’s acceptance he may marry her. He invites Paris to a feast that night, and gives a list of the other intended guests to his servant Peter. Alone, Peter admits he cannot read, and when Romeo and Benvolio arrive he seeks their help. Learning of Capulet’s feast, Benvolio hopes to cure Romeo’s melancholy by taking him there and showing that his beloved Rosaline has no monopoly on beauty.

1.3 Capulet’s wife, much interrupted by the digressive Nurse, tells Juliet of Paris’s suit: they are called to the feast.

1.4 Romeo, Benvolio, and their friend Mercutio have masks and torches ready for their uninvited arrival at the Capulets’ feast. Romeo has dreamed the occasion will be fatal to him, but Mercutio ridicules this notion, attributing dreams to the fairy Queen Mab.

1.5 During the dancing at the feast, Romeo is captivated by Juliet’s beauty, renouncing his infatuation with Rosaline. Despite his mask he is recognized by Tybalt, whom Capulet has to restrain from challenging him. Romeo accosts Juliet and begs a kiss, subsequently learning her identity from the Nurse before he and his friends depart. Juliet similarly learns his.

2.0 The Chorus speaks of the mutual love of Romeo and Juliet, which they will pursue despite the dangers posed by their parents’ enmity.

2.1 Returning from the feast, Romeo doubles back, concealing himself despite the mocking summons of Benvolio and Mercutio. Hidden, he sees Juliet emerge onto her balcony: when she sighs his name, wishing he were not a Montague, he reveals himself, and in the lyrical conversation which follows they exchange vows of love. Juliet promises to send by nine the following morning to Romeo, who is to arrange their marriage.

2.2 Friar Laurence is gathering medicinal herbs early the following morning when Romeo tells him of the night’s events: at first chiding Romeo for so quickly abandoning his passion for Rosaline, he agrees to marry him to Juliet in the hopes of ending the feud between Montagues and Capulets.

2.3 Benvolio and Mercutio at last meet Romeo, and Mercutio banters with him against love. The Nurse arrives with Peter, and after much mockery from Mercutio is able to speak privately with Romeo: Juliet is to come to Laurence’s cell that afternoon, and Romeo will send a rope-ladder by which she may later admit him at her window to consummate their secret marriage.

2.4 The Nurse teases an impatient Juliet before passing on Romeo’s message.

2.5 Friar Laurence warns Romeo against immoderate love before Juliet arrives to be married.

3.1 Benvolio and Mercutio are accosted by Tybalt, who wishes to challenge Romeo: when Romeo arrives, however, he refuses to be provoked to fight, to the disgust of Mercutio, who draws his own sword. As Romeo tries to part the combatants, Mercutio is mortally wounded by Tybalt: incensed, Romeo fights and kills Tybalt before fleeing, aghast at what he has done. The Montagues and Capulets gather, with the Prince, Mercutio’s kinsman, who, learning what has happened from Benvolio, sentences Romeo to immediate banishment.

3.2 Juliet’s eager anticipation of her wedding night is cut short by the Nurse, who brings the news of Tybalt’s death and Romeo’s banishment: moved by her grief, the Nurse promises to find Romeo and bring him despite everything.

3.3 Friar Laurence brings Romeo, hidden at his cell, the news of his sentence, to his inconsolable despair. The Nurse arrives, and has to prevent Romeo from stabbing himself: the Friar reproaches Romeo for his frenzy, telling him to go to Juliet as arranged but leave for Mantua before the setting of the Watch.

3.4 Capulet agrees with his wife and Paris that Juliet shall marry Paris the following Thursday.

3.5 Early the following morning Romeo reluctantly parts from Juliet, descending from her window. Her mother brings Juliet the news that, to dispel the sorrow they attribute to Tybalt’s death, she is to marry Paris: Capulet arrives and, angry at Juliet’s refusal, threatens to disown her unless she agrees to the match. After her parents’ departure, the Nurse advises Juliet to marry Paris. Juliet feigns to agree, but resolves that unless Friar Laurence can help her she will kill herself.

4.1 Paris is with Friar Laurence when Juliet arrives: after his departure, the Friar advises Juliet that she should pretend to agree to the marriage, but that on its eve she should take a drug which he will give her, which will make her seem dead for 24 hours. She will be laid in the Capulets’ tomb, where Romeo, summoned from Mantua by letter, can await her waking before taking her back with him.

4.2 The Capulets and the Nurse are making preparations for Juliet’s wedding to Paris, to which she, returning, pretends to consent. Capulet brings forward its date to the following day.

4.3 Left alone in her chamber that night, Juliet, despite her apprehension at the prospect of awakening in the tomb, takes the Friar’s potion.

4.4 The Capulets’ busy preparations on the wedding morning are laid aside when the Nurse finds Juliet apparently dead: in the midst of their grief Friar Laurence takes charge of funeral arrangements. Hired musicians, no longer needed, jest with Peter.

5.1 In Mantua Romeo has dreamed he died but was awakened by Juliet when his servant Balthasar brings the news that Juliet is dead: intending to return to Verona and kill himself, Romeo buys poison from a needy apothecary.

5.2 Friar Laurence learns that his colleague Friar John has been prevented by plague quarantine restrictions from delivering his explanatory letter to Romeo: he hurries towards the Capulets’ tomb.

5.3 Paris is strewing flowers at the tomb and reciting an epitaph for Juliet when Romeo arrives, sending an apprehensive Balthasar away: Paris attempts to arrest Romeo and is killed in the fight that ensues, asking, as he dies, to be laid with Juliet. Romeo opens the tomb and brings Paris’s body inside. He speaks to the apparently dead Juliet, bidding her a last farewell, drinks the poison, kisses her, and dies. Friar Laurence arrives as Juliet begins to awaken: frightened by the approach of the Watch, he attempts to persuade her to fly with him and enter a nunnery, but she will not leave. She finds that Romeo has taken poison, but there is none left for her: hearing the Watch approaching, she takes his dagger and stabs herself. The Watch, finding the bodies, summon the Prince, the Capulets, and the Montagues (though Lady Montague has just died, in grief at her son’s exile) and arrest Balthasar and Friar Laurence, who are able to explain the whole story to the assembled families. The Prince regards the deaths of Romeo, Juliet, Paris, and Mercutio as the families’ punishments for their feud and his own for failing to quell it. Montague and Capulet shake hands, promising to build statues of the dead lovers.

Artistic features: Romeo and Juliet is, among much else, Shakespeare’s greatest dramatic contribution to the boom in love sonnets which swept literary London in the late 1580s and early 1590s. The play teems with sonnets including its Chorus speeches and, most famously, the first dialogue between Romeo and Juliet, 1.5.92–106. Mercutio aptly observes of the enamoured Romeo that ‘Now is he for the numbers that Petrarch flowed in’ (2.3.36–7), and the play’s entire plot brilliantly reanimates the clichéd Petrarchan *oxymoron whereby the adored mistress is referred to as a ‘beloved enemy’ (cf. 1.5.116–17, 137–40). Like a Petrarchan sonnet, too, the entire play changes in mood at a key turning point, resembling a romantic comedy during its ebullient early scenes but modulating decisively into tragedy with the death of Mercutio in 3.1.

Critical history: By now the impact of Romeo and Juliet extends across most artistic media (particularly *ballet, *opera, and *film) and across most of the world. It was sufficiently well thought of, in some circles at least, for an Oxford divine, Nicholas *Richardson, to quote it in a sermon in 1620, though it was sometimes criticized over the next two centuries for an over-indulgence in punning and rhyming. Because of the citizen status of its protagonists and the generic blending of its construction—its hospitality to the Nurse’s comic garrulity and Mercutio’s bawdy wordplay as well as to Romeo’s sense of fate and the Prince’s moralizing—the play was less acceptable than the other tragedies to *Neoclassical tastes during the Restoration, but was decisively restored to critical favour thereafter. Although John *Dryden reported a tradition that Shakespeare had once remarked that he had been obliged to kill Mercutio in the third act ‘lest he would have been killed by him’, Dr *Johnson, who regarded Romeo and Juliet as one of Shakespeare’s best plays, rejected this story, praising the death of Mercutio as an integral part of the play’s structure. *Romantic writers and artists across the English-speaking world and continental Europe, from *Coleridge to *Berlioz, regarded the play as an unqualified presentation of an ideal love too good for the corrupt world. It was only later in the 19th century that some commentators began to express misgivings that the play was not sufficiently tragic, its conclusion produced too much by malign coincidence rather than character, and from the time of F. S. *Boas onwards various attempts were made to prove the lovers as properly blameworthy as they are in Brooke’s poem. Others, meanwhile, insisted that the play’s main theme was really the feud rather than the relationship between the innocent Romeo and Juliet. Since the later 20th century, critical writing about Romeo and Juliet, while still interested in the question of its genre, has concentrated more heavily on the play’s notions of *sexuality, on its account of Veronese society and family structure, and on its language.

Stage history: Although the early quartos attest to the play’s popularity in the theatres, no specific performances of Romeo and Juliet are recorded before the Restoration. When it reappeared in 1662, with *Betterton as Mercutio, both its style and its fusion of the comic and the tragic were hopelessly out of fashion (‘It is a play of itself the worst that ever I heard in my life’, opined *Pepys), and it was subsequently rewritten by Sir James Howard, who gave it a happy ending (though the tragic ending was performed on alternate nights). Howard’s version, sadly, does not survive, but it had in any case been set aside by the time Romeo and Juliet was supplanted by Thomas Otway’s successful adaptation *The History and Fall of Caius Marius (1679). Otway returned to the play’s earlier sources to have his Juliet (Lavinia) awaken before Romeo (Young Marius) has finished dying of the poison, and a final dialogue between the lovers was retained when Romeo and Juliet returned to the stage in the 1740s, first as Theophilus *Cibber’s heavily Otway-based Romeo and Juliet: A Tragedy, Revised and Altered from Shakespeare (acted at the Haymarket from 1744 onwards and printed in 1748) and then in David *Garrick’s adaptation of 1748. Garrick’s version was closer to the original, though he increased Juliet’s age to 18 and eliminated much of what he dismissed as ‘jingle and quibble’, cutting puns, simplifying diction, and rewriting rhyme as blank verse (shortening even Romeo and Juliet’s sonnet on meeting at the feast). In 1750 he further removed Romeo’s initial crush on Rosaline and added an elaborate funeral procession for Juliet. In one of the most famous theatrical rivalries of all time, Garrick’s Romeo at *Drury Lane competed with Spranger *Barry’s at *Covent Garden for twelve successive nights in 1750 (ending only when Susannah *Cibber, Covent Garden’s Juliet, fell ill), and the play was rarely out of the repertory of either theatre thereafter, acted more often than any other Shakespeare play during the remainder of the 18th century.

Garrick ceased to play Romeo in 1760, considering himself too old for the part, and the youth and naivety of the role deterred many subsequent actor-managers from attempting it at all, though the many actresses who made successful debuts as Juliet were rarely in any hurry to forsake the role, easily one of the longest and most attractive in Shakespearian tragedy. J. P. *Kemble and Sarah *Siddons gave up the parts after 1789, passing them on to Charles *Kemble and Dorothea *Jordan (later succeeded by Fanny *Kemble): Edmund *Kean failed as Romeo in 1815, and two of the most successful Romeos of the ensuing decades were women, Priscilla Horton (1834) and Charlotte *Cushman (1845–6, 1855), whose production was the first to abandon Garrick’s added dialogue in the tomb. (Lydia Kelly had played the role in New York in 1829: the last major female Romeo was Fay Templeton in 1875.) Henry *Irving failed to convince opposite Ellen *Terry in a scenically elaborate production in 1882, which was better received when William Terriss and Mary *Anderson took over the leads during Irving’s absence in America in 1884. (Terry later excelled as the Nurse.) Since then the play has remained immensely popular despite the continuing difficulties leading actors have experienced with the lyrical but comparatively unreflective leading role: *Gielgud, for example, was criticized for relying on his voice at the expense of his body when he played Romeo at 20 in 1924, but returned to it repeatedly, in 1929, for *Oxford University Dramatic Society in 1932 (with Peggy *Ashcroft, and Edith *Evans as the Nurse), and finally at the New Theatre in 1935, playing Mercutio to Laurence *Olivier’s Romeo (again with Ashcroft and Evans). During this record-breaking production, Gielgud and Olivier exchanged roles, Olivier finally more comfortable as Mercutio, although he would play Romeo again (disastrously) in America in 1940. Juliet, however, has been a success for actresses including Claire *Bloom (1952, 1956), Dorothy *Tutin (1958), and Judi *Dench (in *Zeffirelli’s production, 1960). Directors, meanwhile, have increasingly shied away from Romeo’s traditional tights and short tunic to set the play in *modern dress (sometimes glibly translating the feud as a recognizable, topical equivalent), particularly since the success of *West Side Story. Rupert *Goold’s RSC production of 2010, the first new show to be seen in the remodelled *Royal Shakespeare Theatre, compromised by dressing Romeo and Juliet in modern dress and the rest of the cast in Elizabethan.

Michael Dobson

On the screen: Romeo and Juliet has been more filmed than any other Shakespeare play except Hamlet, and in more languages (seven, at the last count): the earliest film (1902) was followed by a number of other silents including one from Italy (1911), the first to use Veronese locations, which anticipated later films in delivering both impressive spectacle and athletic sword-fights. George Cukor’s 1936 sound version included Leslie Howard (Romeo), Norma Shearer (Juliet), Basil Rathbone (Tybalt), and John *Barrymore (Mercutio) among the cast, on a lavishly constructed set. Renato Castellani’s colourful film (1954) aimed at a neo-realist style at the expense of dramatic impact.

Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (1968) caught the fashionable waves of the 1960s and, championing the sincere innocence of the young amid inflexible parental attitudes, was immensely attractive to an adolescent viewing public. Zeffirelli used young inexperienced actors, Olivia Hussey (Juliet) and Leonard Whiting (Romeo), giving the action its visual youthfulness but losing poetic weight in the lines. Notwithstanding some gratuitous sentimentality, the screen is filled with colour, atmospheric contrasts, and passionate energy.

Alvin Rakoff’s production for BBC TV (1978), a disappointing opening to the BBC/Time Life complete plays, set out to make the closeness of the Capulet family a dominant motif, thereby challenging the youth-centred priorities of Zeffirelli’s. Forbidden by the series’ commitment to full texts to sacrifice long speeches in the interests of dramatic pace, this production compensates for the inadequacy of the young performers in its leads by its detailed and sensitive exploration of family relationships, projecting an unusual sympathy for the older generation (notably Michael *Hordern’s Capulet). As such it strives intelligently to use the medium to dramatize feeling rather than athletic action.

Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 William Shakespeare’s Romeo+Juliet, commercially the most successful of all films based on Shakespeare, is both disturbing and clever in juxtaposing the controlled manipulation of the world as the mass media deliver it with the confused but essentially sacrificial love of the teenage Romeo (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Juliet (Claire Danes). The film presents, with the speed and energy of MTV, images which reflect a postmodern American society and environment choked with the obsolescent and the discarded, including a good deal of religious kitsch. Encapsulating the dislocated action within the ephemerality of television news presentations highlights the confusion between a world in which order has disintegrated and one which is presented as managed. Although the play’s script is heavily cut and sometimes almost inaudible over the film’s pop music soundtrack, this is a witty and compelling attempt to translate the story into the terms of contemporary culture and the play into those of contemporary popular cinema. Carlo Carlei’s 2013 film returned to Zeffirelli’s Renaissance Italian aesthetic, and cast two leads unmistakably reminiscent of Hussey and Whiting in Hailee Steinfeld and Douglas Booth. Worse than the sense of aesthetic retread, however, was a frequently cringeworthy script by Julian Fellowes that attempted—sometimes subtly, sometimes blockishly, always inexplicably—to modernize the play’s language.

Anthony Davies; rev. Will Sharpe