t

tabor, a double-headed drum with gut snares on one or both heads, associated with dance when played together with the three-holed *pipe by one person (see The Winter’s Tale 4.4.183).

Jeremy Barlow

Tailor. In The Taming of the Shrew 4.3 he brings a gown for Katherine which Petruccio rejects.

Anne Button

Taine, Hippolyte (1821–93), French historian and critic. Taine’s rationalist objections to the passionate and absurd excesses of Shakespeare, particularly in language and style, owe something to *Voltaire; but he ends by acknowledging Shakespeare’s prodigious, if extravagant and frenzied, genius (see A History of English Literature, 1865).

Tom Matheson

‘Take, O take those lips away’, sung by a boy in Measure for Measure 4.1.1. A setting by John *Wilson, published in 1652, may date back to an early revival of the play. Later settings include those by Alcock, Chilcot, Galliard, Giordani, Jackson, Weldon (18th century); *Bishop, Chausson, Macfarren, Parry, Pearsall (19th century); and van Dieren, Quilter, Rubbra, Warlock, *Vaughan Williams (20th century).

Jeremy Barlow

Talbot, Lord. Commander of the English forces in France, he is reported as having been made prisoner, 1 Henry VI 1.1.145. He returns from captivity, 1.6, and enjoys great military success until killed with his son *John Talbot at Bordeaux, 4.7. Also called John (c. 1388–1453), the real 6th Baron Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, died with his son at Castillon 22 years after *Joan la Pucelle was executed.

Anne Button

Talbot, Young. See John Talbot.

Tamayo y Baus, Manuel (1829–98), one of the most significant Spanish playwrights of the 19th century. His play Un drama nuevo (A New Drama, 1867) is set in Elizabethan England, and the protagonists are Shakespeare’s company of actors. It is the third and most important 19th-century Spanish play in which Shakespeare is a stage character. It contains a hero who is jealous on stage and in real life, and an Iago-figure who feeds his jealousy. It was performed in English as Yorick and Yorick’s Love. There is also a published English translation: A New Drama: A Tragedy in Three Acts from the Spanish, trans. John Driscoll Fitz-Gerald and Thacher Howland Guild (1915). The play was made into a film in Spain in 1946 by Juan de Orduña.

A. Luis Pujante

Tamer Tamed, The See Fletcher, John; Taming of the Shrew, The.

Taming of a Shrew, The, an anonymous play, entered in the Stationers’ Register in 1594 and first printed in the same year, whose precise relation to Shakespeare’s longer and more sophisticated The Taming of the Shrew has long puzzled scholars. Efforts to date it or track its performance history are complicated by the existence of Shakespeare’s play, which on stylistic grounds must have been written before The Taming of a Shrew was published: *Henslowe’s ‘Diary’, for example, records a performance of ‘the Tamynge of A Shrowe’ at Newington Butts on 11 June 1594 (by either the Admiral’s Men or the *Chamberlain’s Men or both), which could be either play. The Taming of a Shrew has a similar main plot and sub-plot to The Taming of the Shrew, though some characters have different names—Ferando (Petruccio) tames Kate, while her sister Philema (Bianca) is won by Aurelius (Lucentio). More strikingly, it has a similar frame-narrative, only here it is completed. Christopher Sly, duped into thinking himself a lord, watches the whole of the inset play, interrupting it from time to time with ribald and impertinent comments, and afterwards is taken back, drunkenly asleep, to the refuse heap where he was found, where he wakes up and decides that the whole experience must have been a dream—an instructive one, however, since he means to employ Ferando’s methods on his own wife. This final phase of the Christopher Sly Induction has often been transplanted from The Taming of a Shrew into productions of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, which at some stage in its existence probably offered a similar closure.

Most of the possible hypotheses about the connections between this play and The Taming of the Shrew have been argued at some point: some scholars have seen it as a source, some a first draft, some a garbled reported text, some a botched plagiarism, some an alternative version of a common lost source. What is certain is that The Taming of a Shrew is a highly derivative play—some passages are taken almost verbatim from *Marlowe—and the balance of probability, supported by early allusions to passages found only in The Taming of the Shrew—suggests that it borrows from Shakespeare rather than vice versa.

Michael Dobson

Taming of the Shrew, The See centre section.

Tamora, Queen of the Goths, vainly pleads for the life of her son Alarbus, Titus Andronicus 1.1; she becomes Saturninus’ Empress while remaining Aaron’s mistress; she is able to avenge her son before falling victim to terrible revenge herself.

Anne Button

Tarlton, Richard (d. 1588), actor (Sussex’s Men 1578, Queen’s Men 1583–8), jester, and writer. The earliest record of Tarlton is as author of a ballad in 1570 and by the end of the 1570s he was also being alluded to as an actor. In 1585 he wrote The Seven Deadly Sins for the Queen’s Men which Gabriel Harvey claimed that Thomas *Nashe plagiarized for his Piers Penniless (1592). Dozens of allusions to Tarlton’s comic improvisations survive in Elizabethan verse and prose and a collection of his so-called ‘jests’ was published in the late 1590s, although the earliest surviving edition is from 1611. This jest-book gives a sense of his clowning talents (which included fencing, verse improvisation, and playing instruments) and some biographical detail: he performed his clowning at inns and at court, he was Protestant, he ran an inn and an ‘ordinary’ (eatery), and he had facial deformities considered comic. The woodcut of Tarlton printed with his jest-book was copied from a Flemish model and is no more than a general guide to his appearance, and John Scottowe’s copy of this woodcut cramps Tarlton’s body to fit it into a prescribed space on the page, introducing deformities which cannot be presumed in the man. One of Tarlton’s trademarks was to thrust his head through a curtain at the back of a stage and peer at the audience before the performance, and he was famous too for his *jigs performed after a theatrical performance.

Gabriel Egan

Tarquin. See Rape of Lucrece, The.

Tate, Nahum (1652–1715), poet and playwright. Reviled by early 20th-century critics for daring to adapt Shakespeare, and successfully at that, Tate was in his own time a highly respected writer, made Poet Laureate in 1692: his achievements include the libretto for Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (1689) and collaborations with John *Dryden on The Second Part of Absalom and Achitophel (1682) and with Nicholas Brady on the New Version of the Psalms (1696). Born in Ireland and educated at Trinity College, Dublin, Tate had settled in London by his mid-twenties, and was soon writing plays, many based on pre-Restoration originals (including *Jonson’s Eastward Ho and The Devil is an Ass and *Webster’s The White Devil). Of his three adaptations of Shakespeare, his topical Richard II (1680) was banned and *The Ingratitude of a Commonwealth (a gory version of Coriolanus, 1681) was never popular, but *The History of King Lear (complete with happy ending, 1681) held the stage, with some progressive alterations, for a century and a half. Despite this success, however, Tate died in hiding from his creditors.

Michael Dobson

Taurus commands Caesar’s land force at Actium, Antony and Cleopatra 3.8 and 3.10.

Anne Button

Tawyer, William (d. 1625), musician and actor (King’s Men by 1624). Tawyer was apprenticed to John *Heminges and appears in a stage direction in the 1623 Folio text of A Midsummer Night’s Dream 5.1 and in a list of King’s Men musicians protected from arrest by Henry *Herbert in 1624.

Gabriel Egan

Taylor, John (1580–1653), the ‘water poet’. Raised in Gloucester and apprenticed to a London waterman, Taylor was pressed into the navy, but he eventually became a waterman again. In his versified The Price of Hempseed (1620), he cites Shakespeare among thirteen English poets who, through paper’s medium, live ‘immortally’.

Park Honan

Taylor, Joseph (c. 1586–1652), actor (York’s Men 1610, Lady Elizabeth’s Men 1611–16, Charles’s Men 1616–19, King’s Men 1619–42). Taylor enters the theatrical record with his unauthorized transfer from York’s Men to Lady Elizabeth’s Men in 1610–11 and had established himself sufficiently to replace Richard *Burbage as the leading King’s Man on the latter’s death in March 1619. In his Roscius Anglicanus (1708) John Downes claimed that Thomas *Betterton’s performance as Hamlet was derived, via William *Davenant, from ‘Mr. Taylor of the Black-Fryars Company’ who was ‘instructed by the Author Mr. Shakespear’. Downes’s reference to the playhouse might suggest the Blackfriars Boys (1600–8) rather than the King’s Men, in which case Shakespeare instructed the adolescent Taylor in something other than Hamlet. Certainly by the time Taylor joined the King’s Men in 1619—between their patent of 27 March, from which he is absent, and their livery warrant of 19 May where he appears—Shakespeare and Burbage were dead. Taylor appears in the 1623 Folio list of players, and he played Ferdinand in Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, Hamlet, Iago, Truewit in Jonson’s Epicoene, and Face in Jonson’s The Alchemist. After John Heminges’s death in 1630 Taylor became a housekeeper of the Globe and the Blackfriars and he and John Lowin took over as joint managers of the King’s Men.

Gabriel Egan

Taymor, Julie (b. 1952), American director. Taymor’s eclectic and experimental career has spanned theatre, opera, happenings, and Broadway musicals. Her engagements with Shakespeare have included a puppet version of The Tempest (Classic Stage Company, New York, 1986) and, more conspicuously, two films: the stylized but harrowing Titus (with Sir Anthony Hopkins in the title role, 1999), and the less well-received The Tempest (2011, with Helen *Mirren as ‘Prospera’).

Michael Dobson

Tchaikovsky, Pyotr (Ilyich) (1840–93), Russian composer. He composed orchestral works based on The Tempest (1873) and Hamlet (1888), but is best known for his fantasy overture Romeo and Juliet (1869, rev. 1870, 1880), which was first choreographed as a ballet in 1937. He also composed incidental music for Hamlet (1891) and considered writing *operas based on Othello and Romeo and Juliet; for the latter there survives an uncompleted duet.

Irena Cholij

Tearsheet, Doll. Falstaff’s mistress, she appears in 2 Henry IV 2.4, and is arrested, 5.4.

Anne Button

television. Televised Shakespeare has been performance history’s disdained foster-child. Whether broadcast live as in the earliest years or filmed for television from original scripts, cut from big-screen versions or filmed from a stage production, it has rarely achieved the status of large-screen *film (itself something of a stepchild). The reasons are simple: television Shakespeare may be interrupted by commercials, shaped to fit a specific time-slot (particularly in the USA), prepared on the cheap without the production values of big-time film, and the victim of small image size, fuzzy contrast, shallow depth of field, and other defects of low-resolution output. In spite of these shortcomings, Shakespeare on television has had a notable past and is becoming even more significant in the wake of HDTV, DVD box sets, and live broadcast screenings. More than any other form, TV has brought Shakespeare to the millions. No one has made a film of All’s Well That Ends Well, but there have been four TV versions, three extant. No excellent film of Antony and Cleopatra exists, but Trevor *Nunn’s 1974 adaptation of his RSC production, with Janet *Suzman, Richard Johnson, and Patrick *Stewart, stands out as a splendid performance in any medium. To understand the potential of TV, one must look at its strongest, not its weakest, productions.

The BBC broadcast the first full-length Shakespeare in the infancy of television, before the Second World War: Julius Caesar in modern dress, enhanced by newsreel film footage (1938). The BBC broadened its achievement with ambitious series, such as An Age of Kings—Richard II; 1 and 2 Henry IV; Henry V; 1, 2, and 3 Henry VI; and Richard III—over a period of fifteen weeks in 1960. These broadcasts proved that a generous budget, seasoned cast, and intelligent production choices could yield impressive results in made-for-television Shakespeare. The BBC also demonstrated that television could respect the language and the setting of a fine stage production, adapting The Wars of the Roses—the *Royal Shakespeare Company’s productions of the Henry VI plays and Richard III—into three television productions.

Like these two series of history plays, the best received of the 36 BBC Shakespeare plays, broadcast 1978–85, were those rarely seen on stage or film, such as, from the first season, All Is True (Henry VIII). The spare and symbolic sets and action of the Henry VI plays (1982–3) and Titus Andronicus (1984–5), directed brilliantly by Jane Howell, confirm that television can accommodate diverse scenic styles, from her austere vision to the lushly realistic All’s Well That Ends Well (1981) directed by Elijah Moshinsky. Hamlet (1981) and Macbeth (1982) are also creditable thanks to Derek *Jacobi’s and Nicol *Williamson’s inventive performances in the eponymous roles rather than to production choices. But the series, even at its worst, repays study, with many bright moments. In 2012, the BBC returned once again to Shakespeare’s history plays with its Hollow Crown series, this time producing four feature-length productions of Richard II, 1 and 2 Henry IV, and Henry V. Created as part of the London 2012 Olympic celebrations and with a reported budget of £9 million, the films boasted the involvement of high-profile theatre and film directors such as Sam *Mendes, Rupert *Goold, Richard *Eyre, and Thea Sharrock, and an array of stars from the stage and screen, including Tom *Hiddleston as Prince Hal, *Patrick Stewart as John of Gaunt, Ben *Whishaw as Richard II, and Simon *Russell Beale as Falstaff. PBS Television aired the series in the *United States in autumn 2013.

In America, the leading sponsor of early Shakespeare on television was the Hallmark Greeting Card Company, whose Hallmark Hall of Fame productions broadcast Hamlet live in 1953, starring Maurice *Evans, directed by George Schaefer. The pair had produced their ‘GI’ Hamlet during the Second World War for service personnel overseas; meant for a mass audience, it served as a template for their TV production. The best of the eight Hallmark productions is probably The Tempest (1960), which avoids the problematic side of the play and focuses on pastel delight, with Lee Remick as Miranda, Evans as a kindly but magisterial Prospero, and Richard *Burton as Caliban. NBC-TV had broadcast Hallmark’s first Macbeth, with Evans and Judith *Anderson, in colour, but few people had colour sets in 1954. By 1960, when the same principals (Evans, Anderson, Schaefer) made Macbeth again, it was filmed in colour on location, meant for cinema release as well as for broadcast. One misses the scary immediacy of live performance—a stagehand makes an unscheduled appearance in the 1953 Hamlet. A second Hamlet—filmed in 1970, with Richard Chamberlain as Hamlet, Richard Johnson as Claudius, and directed by Peter Wood—marked the end of Hallmark Shakespeare productions. Chamberlain’s was the first Hamlet that Kenneth *Branagh saw, and one can recognize in his design for his 1996 film some hints of Peter Roden’s television setting, featuring a large hall dominated by a grand stairway. Hallmark, of course, was not the only American sponsor: Kenneth Rothwell reports that, between 1949 and 1979, ‘nearly fifty televised Shakespeare programs appeared in the United States’ (1999).

Some films fatten their budgets from television connections (the Olivier Richard III, simultaneously released in cinemas and broadcast in 1956, is a case in point, as is Adrian *Noble’s Channel 4 Films screen adaptation of his RSC A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1996–7). And feature films are of course now routinely made available on DVD and for Internet download after their cinematic runs. Celebrated individual productions have been produced specifically for television and these too are released on DVD. In Britain Granada TV produced King Lear, starring Laurence *Olivier, directed by Michael Elliott (1983), affording viewers an excellent opportunity to see Olivier in a full-length production when a stage performance would have overtaxed him. The prehistoric setting, the King’s gentleness at first with Cordelia, played with tender rectitude by Anna Calder-Marshall, and the chillingly beautiful Diana *Rigg as Regan, make this a fascinating addition to the Lear collection. Ragnar Lyth’s Hamlet (1984), for Swedish television, is a visually striking low-budget adaptation, unfortunately not yet available on video. Straight-to-video productions need not be listed in detail here (see Rothwell, ‘Electronic Shakespeare’). A commendable example, however, is the first and best of the Bard Series, the 1979 Merry Wives of Windsor, produced by R. Thad Taylor and recorded on the stage of the Los Angeles Globe theatre.

Live staged Shakespeare has sometimes also appeared on TV. The PBS Television broadcast of William Ball’s sprightly American Conservatory Theatre of San Francisco Taming of the Shrew (1976) releases the play’s antic energy. Another more serious Shrew, filmed with audience in view at the Stratford, Ontario, Shakespeare Festival (1981), uses the Sly frame to good advantage. Kiss me, Petruchio (1981), a glimpse of a performance, stars Raul Julia and Meryl Streep as Petruchio and Kate and as themselves backstage during a performance of The Taming of the Shrew in the Park (the *New York Shakespeare Festival, 1978). This documentary improves upon the full production, extracting the gold and leaving the dross behind. Multiple video versions of plays like The Taming of the Shrew allow viewers to compare choices as no other medium can. The rise of live-broadcasting to cinema has raised questions as to whether live theatre on television might also enjoy a comeback in future years.

Often producers separate the filming of a play from its editing rather than edit on the spot in the control room. That distance from its stage origin can make for a disappointing translation. But for those who did not have the opportunity to see a stage production or who seek to recall details, video is a blessing. Hamlet with Richard Burton, directed by John *Gielgud, was recorded on film from 17 camera angles during a performance in 1964. The footage was used to create a film shown in nearly 1,000 cinemas for two days only, but it was eventually made available on video too and captures the musicality and variety of Burton’s delivery. This production and its video records later became the basis for the *Wooster Group’s multimedia stage reconstruction of the Gielgud-Burton Hamlet in 2013. In 1989–90, Michael *Bogdanov and Michael *Pennington caught with multiple cameras during performance at least some of the energy of their postmodern, seven-part, *English Shakespeare Company Wars of the Roses (Richard II to Richard III).

Until relatively recently, most stage-to-screen productions did not risk filming a stage performance but instead shot it in a studio or on a location set, without an audience. Ian *McKellen and Judi *Dench appear in Trevor Nunn’s powerful version of Macbeth, staged at the Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon (1976); adapted for Thames Television (1979), it was shot on a sound set. Kevin Kline reconceived for television his 1990 performance, as actor and director, of Hamlet at the New York Public Theater. More recently, Greg *Doran transposed his 2008 production of Hamlet, starring David *Tennant and Patrick Stewart, to the small screen for a Boxing Day broadcast in the UK in 2009, and Rupert Goold likewise adapted his 2007 Macbeth, also starring Stewart, for television screening in 2010. Both directors chose to retain the theatrical casting and concept but to film the action on location in a real-world setting. Each of these productions suggest stage while taking advantage of studio technology.

Televised Shakespeare has led to its integration into general consciousness. A 1998 episode of the American series Mystery Science Theatre 3000 showcases Peter Wirth’s Hamlet, starring Maximilian Schell. While the black and white production unfolds with its dubbed-in English, the serial’s characters, a human and two robotic friends, make snide remarks. Imagine that! A 40-year-old German Hamlet for television making an almost full-length appearance (80 minutes of the original 127) on a cult comedy sci-fi show. Shakespeare appears everywhere on TV (accounting for perhaps 0.01% of allusions); and with Shakespeare more available on video, a mass audience may recognize such allusions whether on The Simpsons or Star Trek. (See also popular culture.)

Any generalization about the medium can be overturned by contrary examples, but a few suggest themselves: TV is an intimate medium, on both sides of the tube. Actors in dialogue are apt to be close together; they can whisper; their expressions in close-up drive the drama. The audience is close, alone or with a few others, at ease, requiring energy from the screen to focus its attention. Directed by the actors and the mise-en-scène, the audience will pay careful attention to the language. On the other hand, viewing large scenes on news programmes (the movement of armies, New Year’s Eve fireworks) readies audiences for at least occasional panoramas. Though TV partakes of aspects of film, stage, and *radio, televised Shakespeare is not exactly like Shakespeare in any other medium, and its possibilities are enormous. In recent years, however, TV has faced increasing competition from the Internet, both in terms of the Internet as a provider of filmed entertainment and, increasingly, as a creator of it. Internet-based companies such as Digital Theatre sell downloadable and rentable copies of live-filmed theatre, including many Shakespearian productions, and more grassroots production companies have distributed recordings of their work freely through YouTube and similar platforms. TV as a medium distinct from the Internet is quickly disappearing, and TV Shakespeare is necessarily changing with the platform.

Bernice Kliman, rev. Erin Sullivan

‘Tell me, where is Fancy bred?’, sung by a member of Portia’s train in The Merchant of Venice 3.2.63. The original music is unknown.

Jeremy Barlow

Tempest, The See centre section.

Temple Grafton, one of the ‘Shakespeare villages’, 5 miles (8 km) west of Stratford. On her marriage, Anne *Hathaway was described as being ‘of Temple Grafton’. A conjectured explanation is that the marriage took place there. If so it is likely to have been performed by the vicar John Frith, described in a Puritan survey of 1576 as ‘an old priest and unsound in religion’ (implying that he was a Catholic), who ‘can neither preach nor read well’, and whose ‘chiefest trade is to cure hawks that are hurt or diseased, for which purpose many do usually repair to him’.

Stanley Wells

Temple Shakespeare, a pocket hardback edition for the general reader edited by Israel Gollancz with minimal prefaces and glossaries between 1894 and 1896. The later *New Temple edition preserves the pocket format, but is in other respects quite different.

R. A. Foakes

Tennant, David (b. 1971), Scottish actor. Tennant’s childhood enthusiasm for acting is said to have arisen from his love for the children’s television science-fiction series Dr Who, in which he played the title role between 2005 and 2010, but he has performed in Shakespeare with equal success. He joined the *Royal Shakespeare Company to play Touchstone in As You Like It in 1996, and then played a fine Edgar in King Lear at the Royal Exchange in Manchester (1999) before returning to Stratford to play Antipholus of Syracuse in The Comedy of Errors, Romeo, and Jack Absolute in Sheridan’s The Rivals in 2001–2. Towards the end of his spell as Dr Who he returned to the RSC once more to play a stylish, quizzical Berowne and an equally convincing Hamlet, under the direction of Gregory *Doran (2008). The rising star who had left some seven years earlier returned to the Stratford stage a superstar. Tennant’s enormous crossover appeal meant that both shows sold out for the duration of the Stratford run and the transfer to the *Barbican, helping sell the RSC brand to a more diverse youth audience. Even after his Tenth Doctor regenerated into Matt Smith’s Eleventh, Tennant’s enduring association with the role meant that subsequent forays into stage Shakespeare remained ‘event’ productions. He played Benedick alongside Dr Who co-star Catherine Tate’s Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing at Wyndham’s Theatre in 2011, and helped inaugurate Doran’s tenure as artistic director of the RSC in late 2013 in a traditionally grandiose and expensive star-vehicle Richard II, a production that marked a significant change from the ensemble driven, Russian-influenced asceticism of Michael *Boyd’s reign.

MD(WS) Michael Dobson (rev. Will Sharpe)

Tennyson, Alfred Tennyson, Baron (known as Alfred, Lord Tennyson) (1809–92), English Poet Laureate. Tennyson, like most eminent literary Victorians, was steeped in Shakespeare from childhood, through reading rather than the stage, although he saw Fanny *Kemble perform at Christmas in 1829 and discussed Hamlet with Henry *Irving after a Lyceum performance in March 1874. He even thought to emulate Shakespeare with Queen Mary: A Drama (1874; abridged and performed 18 April 1876). Among his poems, ‘Mariana’ (from Poems, Chiefly Lyrical, 1830) is inspired by Measure for Measure; a satirical poem addressed to Bulwer Lytton, The New Timon, and the Poets, appeared in Punch (28 February 1846); the intense elegiac emotion expressed for Arthur Henry Hallam in In Memoriam (1850) is sometimes compared to the Sonnets; and the introspective inactivity of the hero of Maud (1855) is often identified with Hamlet. On his deathbed Tennyson called out for Shakespeare, and he was buried with a copy of Cymbeline in his hand.

Tom Matheson

Terence (?190–?159 bc), Roman comic dramatist, brought to Rome from Carthage as a slave but later freed for his literary talents. Like *Plautus, he adapted the Greek New Comedy, specifically the plays of Menander, to produce six plays based on the same stock characters and intrigue plots. Terence’s style and plotting were studied in 16th-century grammar schools, where he was also attributed with the invention of the five-act structure. Shakespeare’s debt to the Roman may include echoes from his plays Andrian and The Eunuch, in The Taming of the Shrew, Love’s Labour’s Lost, and Much Ado About Nothing.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

Terry, Dame Ellen (1847–1928), English actress, who made her debut under the exacting tutelage of Charles and Ellen *Kean at the Princess’s theatre, where (between 1854 and 1859) she played the Duke of York (Richard III), Mamillius, Puck, Prince Arthur, and Fleance, attracting the attention of Lewis Carroll. In her early teens Terry alternated engagements in London and Bath/Bristol, where she was admired as Titania and Desdemona.

Although her marriage in 1864 to the artist G. F. Watts deprived the stage of her talents for several years, she was not entirely lost to Shakespeare; her husband’s several portraits of her included one as Ophelia. Ellen Terry’s ravishing beauty (in particular her golden hair) made her—in W. Graham Robertson’s words—‘par excellence the Painter’s actress’, but more significantly it also made her the visual embodiment of ideal femininity during the apogee of stage pictorialism.

In 1875, one year after returning to the stage, she appeared as Portia—‘so fresh and charming…so fair and gentle…it is the very poetry of acting’ wrote Clement Scott—in the Bancrofts’ scenically innovative revival of The Merchant of Venice with designs by the architect E. W. Godwin, who was the father of her two—illegitimate—children. In 1878 Ellen Terry became Henry *Irving’s leading lady at the Lyceum where, beginning with Ophelia (1878) and ending with Volumnia (1901), she also played Portia, Lady Anne, Beatrice, Juliet, Viola, Lady Macbeth, Queen Katherine, Cordelia, and Imogen. As the main quality which Ellen Terry brought to these roles, in addition to her beauty, grace, and charm, was a seemingly artless naturalness and spontaneity, her success tended to be in ratio to the congruence between her and the part. Thus Lady Macbeth and Queen Katherine were mistakes, but Henry *James, who had been totally unsusceptible to the charms of Terry’s Portia, wrote of her Imogen (1896), ‘no part she has played in late years is so much of the exact fit of her particular gifts’. At the Lyceum the display of Ellen Terry’s gifts was never the determining factor: that was Irving’s role. Thus as Ophelia and Lady Macbeth she had to defer in costume and interpretation (respectively) to Irving’s Hamlet and Macbeth, and she never played Rosalind, to whom she was ideally suited.

After her long partnership with Irving ended, Ellen Terry pursued her career elsewhere. In 1902 she appeared as Mistress Page with Beerbohm *Tree and in 1903 she gave a reprise as Beatrice in her son Edward Gordon *Craig’s production of Much Ado at the Imperial theatre. Increasingly subject to poor sight and failing memory, Ellen Terry devoted herself to her Shakespeare lectures, which she gave in Britain, America, and Australia 1910–21. These form the basis of her Four Lectures on Shakespeare, published posthumously in 1932. Ellen Terry died at her home in Smallhythe (Kent), which is now the property of the National Trust and houses the extensive archive which is an indispensable resource for biographers not only of Ellen Terry but also of her daughter Edy Craig.

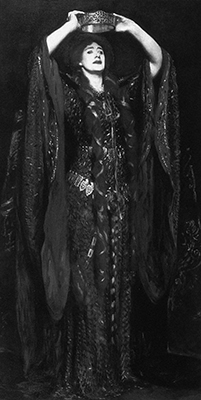

John Singer Sargent’s celebrated portrait of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, 1889: the dress she wore in the role, still preserved at her house in Kent, is embroidered with the wing-cases of beetles.

Richard Foulkes

Tetralogy, First, a term for Shakespeare’s first four English history plays—1 Henry VI, The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI), Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI), and Richard III—when they are discussed as a multi-part narrative and/or performed as a cycle. Though composed first, chronologically they follow the reigns of Richard II, Henry IV, and Henry V dramatized in the Second Tetralogy.

Randall Martin

Tetralogy, Second, a term for Richard II, 1 and 2 Henry IV, and Henry V when they are discussed as a group or performed as a cycle: see also Henriad.

Michael Dobson

tetrameter, a verse line of four feet, used by Shakespeare principally (1) as an occasional variation from *pentameter, (2) as the basic metre of *songs (‘Take, O, take those lips away’ (Measure for Measure 4.1.1 ff.) ), (3) for the rhymed and songlike speeches of special kinds of characters: the *fairies sometimes in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the witches in Macbeth, or lovers who are would-be poets (Love’s Labour’s Lost 4.3.99–118).

George T. Wright

textual criticism. A. E. Housman famously defined textual criticism as ‘the science of discovering errors in texts, and the art of removing them’. The traditional goal of textual criticism is to reconstruct the process by which a text was transmitted to an existing document and to restore that text to its original form. Shakespearian textual critics are primarily interested in the nature of the lost manuscripts that served as printers’ copy for the early *quartos and *folios.

The principles of modern textual criticism are articulated in W. W. *Greg’s ‘The Rationale of Copy-Text’ (1950). Greg argues that an editor may best approximate an author’s finally intended text by adopting as ‘copy text’ the printed text closest to the author’s manuscript and then emending that copy text with any later variants judged to be authorial based upon an understanding of how the error occurred in the transmission of the text.

In the case of Hamlet, analysis of textual features in the second quarto (1604/5) suggests that it was set into type from Shakespeare’s *foul papers. This hypothesis would explain a number of readings in the Q2 text—such as the spelling ‘Gertrad’—as instances in which the compositor misread Shakespeare’s *handwriting, in the known examples of which the letter a and the letter u are often indistinguishable. In the Folio text of the play, which appears to derive from a theatrical playbook, Hamlet’s mother is named ‘Gertrude’. Since Q2 represents the text closest to the author’s manuscript it might be chosen as the copy text for a critical edition. But an exercise in textual criticism reveals compelling reasons for believing that the name that Shakespeare intended and the name that was spoken onstage was ‘Gertrude’ and therefore provides an editor with a rationale for emending the quarto text by reference to the Folio variant.

Eric Rasmussen

Thaisa, daughter of King Simonides, marries Pericles. She is thought to have died giving birth to Marina, Pericles 11, but survives to be reunited with her family, 22.

Anne Button

Thaliart (Thaliard) is Antiochus’ henchman in Pericles 1 and 3.

Anne Button

Theatre, the first substantial purpose-built London playhouse in England since Roman times, built in 1576 by James *Burbage and his brother-in-law John Brayne in the grounds of the former Hollywell Priory in the Shoreditch district just north-east of the City and hence beyond the jurisdiction of the anti-theatrical Puritan city fathers. Much of what we know about the Theatre is preserved through the legal squabbling between the partners and their heirs. Although the *Red Lion was earlier (built 1567), the Theatre appears to have been considerably more substantial than its predecessor and indeed its timbers survived in the form of the *Globe until the fire of 1613. The only possible contemporary picture of the Theatre is the sketch belonging to Abram Booth now in the University of Utrecht library, which may be a depiction of either the Theatre or the *Curtain. This shows an apparently round open-air structure with a superstructural hut like that at the *Swan, but artistic distortion of proportion (especially height) limits this picture’s usefulness concerning the Theatre’s size. The presence of the superstructural hut does not prove that the Theatre (or indeed the Curtain) had a stage cover and posts similar to those of the Swan since this might be merely the top of a ‘turret’ like that at the Red Lion. Patrons could apparently stand in the yard around the stage and either stand or sit in the galleries which enclosed the yard.

The location of the Theatre had been determined by W. H. Braines in 1917 and archaeological excavations found it there in 2008. This work, continued in 2010–11, has revealed the Theatre to be a polygonal building—probably the first such playhouse in this now familiar form—with a diameter of about 72 ft (22 m). It had two gallery walls, enclosing a yard with traces of an ‘ingressus’ (an entry from the yard into the galleries named after the feature so labelled in the Swan drawing) and possibly the edge of a stage at its western end. There was a paved entrance ‘piazza’ on its eastern side off what is now New Inn Broadway and other ancilliary buildings to the north.

When it was built the Theatre was available to any playing company to use and Burbage’s own company, Leicester’s Men, may have played there in its early days. There are references to Oxford’s Men there in 1580 and the newly founded Queen’s company in 1583. The nascent Admiral’s Men were there by 1590, but after a row with Burbage the next year, they left for the Rose on Bankside. However, the precise occupancy is largely untraceable before the settlement of 1594 which licensed the *Chamberlain’s Men to use the Theatre and the Admiral’s Men to use the Rose. Shakespeare’s plays written in the latter half of the 1590s, Love’s Labour’s Lost, Richard II, Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, King John, The Merchant of Venice, 1 and 2 Henry IV, and Much Ado About Nothing, would have been written for the Theatre. The nearby *Curtain playhouse was described as an ‘esore’ to the Theatre in 1585, which suggests an obscure financial connection which might have involved the Chamberlain’s Men playing at the Curtain. The lease on the site expired in 1597, and when negotiations for its renewal stalled and the Blackfriars project was thwarted the Burbages engaged the master carpenter Peter *Street to pull it down. That some of its building material was used in their new venture, the Globe south of the river, gave rise to a myth that the Globe was merely the Theatre reassembled.

Gabriel Egan, rev. Julian Bowsher

Theatre Museum, evolved from Gabrielle Enthoven’s Shakespeare-rich collection of theatrical memorabilia, bequeathed to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1924. It operated independently in Covent Garden from 1987 to 2007 and is now part of the V&A in Kensington.

Susan Brock

theatres, Elizabethan and Jacobean. The Romans built amphitheatres in Britain during their occupation, but we know of no purpose-built theatres erected between their departure and the construction of the open-air galleries and stage of the *Red Lion in Stepney in 1567. More substantial than the Red Lion were James *Burbage’s *Theatre in Shoreditch built in 1576 and Henry Lanham’s nearby *Curtain built in 1577, both of which echoed the circular shape of the Roman amphitheatres. Also in 1576 Richard Farrant began to use the Upper Frater of the *Blackfriars Dominican monastery as a playhouse and some time in the 1570s the Paul’s playhouse opened. The first playhouse south of the river was probably the one at Newington Butts, about which almost nothing is known, but in 1587 Philip *Henslowe built his open-air *Rose theatre on *Bankside and this was joined by its neighbours the *Swan (1595) and the *Globe (1599). There had long been an animal-baiting ring in the south bank area known as Paris Garden, but the theory that open-air playhouses developed out of the tradition of placing a touring company’s portable stage and booth inside a baiting ring is unproven. In truth we do not know where the open-air circular playhouse design came from, other than imitation of the Roman style. In 1599–1600 Henslowe built a new open-air playhouse, the Fortune, north of the river, but broke with tradition in making the gallery ranges in the form of a square. This was however more likely based on the shape and size of the available building plot than as a conscious attempt to define a new building type; theatrical impresarios were nothing if not pragmatic.

Until 1608, when the King’s Men regained the Blackfriars, the indoor theatres were used exclusively by companies of child actors and the open-air playhouses dominated the adult industry. So that the candles might be trimmed, it was necessary at the indoor playhouses to divide the performance into five acts and for short musical interludes to fill the intervals, and act intervals spread to the outdoor playhouses with the King’s Men’s acquisition of the Blackfriars. The terminology ‘public’ and ‘private’ theatre for the open-air and indoor theatres respectively is misleading as both kinds were open to the public, although the considerably higher cost of entrance to the indoor theatres kept out all but the middle and upper classes. In 1616 Christopher *Beeston built the indoor Cockpit theatre in Drury Lane which competed directly with the Blackfriars for the elite market, and a number of new theatres followed before the Civil War. All the theatres were closed by order of Parliament in 1642 as war became inevitable and those which were still structurally sound were converted into dwellings or their timbers stripped for reuse elsewhere.

Gabriel Egan, rev. Julian Bowsher

‘Then they for sudden joy did weep’, a misquoted mid-16th-century ballad, sung by the Fool in The Tragedy of King Lear 1.4.156. F. W. Sternfeld’s Songs from Shakespeare’s Tragedies (1964) gives a tune from an early 17th-century source.

Jeremy Barlow

Theobald, Lewis (1688–1744), English Shakespearian editor. In his Shakespeare Restored (1726), which was a response to the inadequacies of Alexander *Pope’s edition, and in his own edition of The Works of Shakespeare (1733), Theobald was the first to bring to Shakespeare methods previously developed and employed in classical and biblical editing and commentary. Rejecting Pope’s free and aesthetic approach to the Shakespearian text, Theobald insisted that, at points of apparent corruption, the editor must resort in the first place to collation of ‘the older Copies’, and avoid imposing alterations on the basis of a modern taste. At the same time he argued that, where surviving texts were apparently irrecoverably corrupt, the editor must resort to a responsible and essentially interpretative process of conjectural textual *emendation founded upon ‘Reason or Authorities’. For such an editorial task Theobald was well qualified by his critical intelligence, professional familiarity with the theatre, acquaintance with secretary hand, and above all by his exceptionally extensive reading in the drama and other writings of Shakespeare’s time. Alexander Pope, stung by the demolition of his own editorial work in Shakespeare Restored, and lacking and despising Theobald’s knowledge of ‘all such reading as was never read’, constructed in his first Dunciad (1728) a distorted but influential picture of Theobald as a dull and pedantic verbal critic. Nevertheless, Theobald’s edition was reprinted seven times in its own century, and his textual and interpretative judgements have been drawn on by many later editors, including virtually all his 18th-century successors.

Marcus Walsh

‘There dwelt a man in Babylon’, the opening of a mid-16th-century *broadside, ‘The Ballad of Constant Susanna’, quoted or sung by Sir Toby in Twelfth Night 2.3.75. The tune is ‘Would not good King Solomon’, also known as ‘Guerre guerre gay’.

Jeremy Barlow

Thersites inveighs against his fellow Greeks throughout Troilus and Cressida. A cowardly figure with a small part in *Homer’s Iliad, he does not appear in medieval romances.

Anne Button

Theseus advises Hermia to obey her father Egeus in A Midsummer Night’s Dream 1.1. He and his followers find the sleeping lovers in the wood, 4.1, and he announces that their weddings will be celebrated with his own to Hippolyta. In The Two Noble Kinsmen he postpones his wedding to Hippolyta in order to make war on Creon at the three queens’ request: he imprisons Palamon and Arcite, and eventually decrees the terms on which they will conclude their rivalry: after a formal combat, the winner will marry Emilia; the loser will be executed. He is a legendary Greek hero, best known for defeating the Minotaur and seducing a long series of women.

Anne Button

‘They bore him barefaced on the bier’, sung by Ophelia in Hamlet 4.5.165, often to the tune ‘Walsingham’; see ‘How should I your true love know’.

Jeremy Barlow

Thidias is Caesar’s messenger to Cleopatra: Antony orders him to be whipped for kissing her hand, Antony and Cleopatra 3.13. He is called Thyreus by *Plutarch (*Theobald and many later editors have followed this spelling).

Anne Button

Thirlby, Styan (?1686–1753), English theologian and critic, whose annotated copy of *Pope’s edition of Shakespeare (1723–5), together with a list of emendations and a commentary, were used by *Theobald when preparing his edition. Thirlby’s notes were consulted again by Dr *Johnson when he was preparing his own edition: he borrowed them from Edward Walpole, to whom Thirlby had bequeathed his library.

Catherine Alexander

‘Thisbe’. See Flute, Francis.

Thomas, Ambroise. See opera; Shakespeare as a character.

Thomas, Friar. See Friar Thomas.

Thomas, Lord Cromwell. Derived from *Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, this anonymous play is tentatively attributed to Wentworth Smith. The ascription to Shakespeare is not sustainable, despite the initials ‘W.S.’ printed on the 1602 and 1613 quartos.

Sonia Massai

Thomas of Woodstock, an anonymous play, unpublished during Shakespeare’s lifetime though perhaps written c. 1592–5, which influenced Richard II. Woodstock was also known as The First Part of the Reign of King Richard the Second and Shakespeare’s play has been proposed as Part 2. This theory is based on the fact that Shakespeare omitted some of the obvious events of Richard’s reign or referred only briefly to them, in particular the blank charters and the murder of Gloucester, as if confident that they were already known to his audience. But the latter would not have needed to know Woodstock to have filled in these gaps and the two-part play theory is further problematized by the considerable overlap between the plays and their differences in tone and emphasis. Bolingbroke does not appear at all in Woodstock and the representation of Richard is far less sympathetic than that of Shakespeare. Nevertheless, the portrayal of Gloucester as a man of honesty, loyalty, and integrity, in defiance of *Holinshed’s Chronicles, is common to both and may have been a source for Gaunt. It is in 2.1, where Gaunt describes Richard’s abuses of England, that the verbal correspondences between the two plays are clustered.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

Thorndike, Dame Sybil (1882–1976), English actress. Brought up in a high Anglican clergy-house, she spent three years in North America playing out of doors on a far-flung tour of pastoral plays with Ben *Greet. Back in England she worked in pioneering modern drama, marrying Lewis Casson. During the First World War years, as a member of the first regular Shakespearian company at the *Old Vic, she played many of Shakespeare’s women and (men being at the front) Lear’s Fool and Prince Hal. She was admired as a tragedienne, playing in Gilbert Murray’s translations from the Greek and Shaw’s St Joan but also Queen Katherine in All Is True (Henry VIII), Volumnia to Laurence *Olivier’s Coriolanus, and Constance in King John. Early in the Second World War she toured Welsh mining villages as Lady Macbeth, and in the famous Old Vic seasons at the New Theatre she was Queen Margaret to Olivier’s Richard III and Mistress Quickly to Ralph *Richardson’s Falstaff. A passionate Christian Socialist and a pacifist, she was made a Companion of Honour and, when her ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey, John *Gielgud described her as the most greatly loved English actress since Ellen Terry.

Michael Jamieson

Thorpe, Thomas. See Mr W. H.; printing and publishing; Sonnets.

three-man songs, simple songs for three voices (see The Winter’s Tale 4.3.41). Also known as ‘free-men’s songs’.

Jeremy Barlow

‘Three merry men be we’, a snatch of song quoted in many 17th-century plays and lyrics, including by Sir Toby in Twelfth Night 2.3.73.

Jeremy Barlow

throne (state). The official chair of a monarch was set on a raised dais under a canopy and the combined property, or either of its components, could be called a throne or state. An ordinary chair placed within a multi-purpose stage booth was the simplest way to represent the state. In 1595 Philip *Henslowe paid carpenters for ‘making the throne in the heavens’ at the Rose and in the prologue to Every Man in his Humour *Jonson mocked plays in which a ‘creaking throne comes down’ from above the stage, but in these cases ‘throne’ means simply ‘chair used for descents’ rather than the monarchical state which would have been carried or pushed onto the stage.

Gabriel Egan

Throne of Blood. See Kurosawa, Akira.

Thump, Peter. See Horner, Thomas.

Thurio is one of Valentine’s rivals for Silvia in The Two Gentlemen of Verona.

Anne Button

Tieck, Ludwig (1773–1853), German Romantic author. He translated anonymous Elizabethan plays, many of which he ascribed to Shakespeare (Alt-Englisches Theater, 1811; Shakespeares Vorschule, 1923–9), but his projected ‘Book on Shakespeare’ remained fragmentary. Tieck supervised his daughter Dorothea and W. von Baudissin’s completion of A. W. *Schlegel’s translation (‘Schlegel–Tieck’ Shakespeare, 1825–33). In novellas he dealt with Shakespeare’s life and theatre (Dichterleben, 1826; Der junge Tischlermeister, 1836). He staged an exemplary Midsummer Night’s Dream in Berlin (1843).

Werner Habicht

Tillyard, E(ustace) M(andeville) W(etenhall) (1889–1962), English academic, long one of the most widely consulted of modern critics. Shakespeare’s Last Plays (1938), Shakespeare’s History Plays (1944), and Shakespeare’s Problem Plays (1950) all argue for a pattern of organic relations and development between plays often considered discretely. His The Elizabethan World Picture (1943), once the almost canonical account of commonly held Elizabethan beliefs about man’s place in the universe, has recently come under fierce attack, particularly by *cultural materialists, for disguising the scepticism, tension, and equivocation underlying conventional orthodoxy. Its dogmatic stance may be questionable, but its usefulness in transmitting esoteric ideas persists.

Tom Matheson

Tilney, Sir Edmund. See censorship; Master of the Revels; Sir Thomas More.

Time is a personification who acts as ‘Chorus’, The Winter’s Tale 4.1, to explain the passing of sixteen years.

Anne Button

Timon of Athens See centre section.

Tippett, Sir Michael (1905–98), English composer. Tippett’s first major opera, The Midsummer Marriage (1955), though clearly influenced by A Midsummer Night’s Dream in mood and theme, uses none of Shakespeare’s text. The Knot Garden (1970), however, draws heavily on The Tempest: it includes quotations from his Songs from Ariel, written for a production of The Tempest at the Old Vic in May 1962.

Irena Cholij

tireman, the wardrobe-keeper in a playhouse, responsible for the acquisition and orderly (moth-free) storage of the costumes and for repairs and alterations. Like other non-performing hired men, the tireman could be called upon for small roles.

Gabriel Egan

tiring house. Any place concealed from the audience could be used as the actors’ dressing (or ‘tiring’) place, but in the purpose-built playhouses the back wall of the stage (or frons scenae), pierced by the stage doors, was also the front wall of the tiring house. As well as a changing room, the tiring house was a storage space for the properties, the costumes, and presumably the playbooks. In de Witt’s drawing of the *Swan the tiring house is labelled ‘mimorum aedes’ (actors’ house) and its roof forms the floor of the balcony over the stage which could be used for playing ‘above’.

Gabriel Egan

Titania, the queen of the *fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, refuses to give up a changeling boy she has adopted to Oberon. When asleep, he drugs her so that she will fall madly in love with the first person she sees. This is Bottom, who has an ass’s head (also by fairy magic): she takes him to her bower. After obtaining the changeling from her, Oberon takes pity and removes the enchantment. Now disgusted by Bottom, she is reconciled to Oberon.

Before the Second World War, actresses who played Titania usually aimed at an ethereal, queenly elegance and beauty. In the last half of the 20th century, however, her sexual desires have come under investigation, notably by Jan *Kott who argued that ‘The slender, tender and lyrical Titania longs for animal love.…Sleep frees her from inhibitions. The monstrous ass is being raped by the poetic Titania, while she still keeps on chattering about flowers’ (Shakespeare our Contemporary, 1963). This interpretation influenced Peter *Brook’s groundbreaking 1970 production, which started what has almost become a modern stage convention of ‘doubling’ the actors who play Titania and Oberon with Hippolyta and Theseus, so that sexual issues in the mortal world are seen to be reflected in the dreamlike fairy world.

Anne Button

Titinius is sent on a mission by Cassius at Philippi, Julius Caesar 5.3. Cassius despairs and kills himself when he thinks Titinius has been slain. Titinius kills himself with Cassius’ sword.

Anne Button

title pages were affixed to early Shakespearian *quartos to identify their contents and were often tacked on walls to advertise them. These title pages generally provide the title of the play, the name of the dramatist, and the printer’s *device and *imprint. They also frequently give the name of the acting company and the theatre (‘his Majesty’s Servants, at the Globe on the Bankside’) or details of the play’s performance history (‘As it was presented before her Highness this last Christmas’), the text’s claims to authority (‘according to the true and perfect copy’), its publication history (‘Newly imprinted and enlarged’), and even a capsule summary (‘With the extreme cruelty of Shylock the Jew towards the said Merchant, in cutting a just pound of his flesh: and the obtaining of Portia by the choice of three chests’).

Eric Rasmussen

Titus Andronicus See centre section.

Titus Lartius. See Lartius, Titus.

Titus’ Servant. See Hortensius’ Servant.

tobacco, made from the dried leaves of the south American plant Nicotiana tabacum, was first introduced to England in the 1560s.

William Harrison wrote in 1573, ‘In these days the taking-in of the smoke of the Indian herb called Tobacco, by an instrument formed like a little ladle, whereby it passes from the mouth into the head and stomach, is greatly taken-up and used in England.’

Sir Walter *Ralegh is credited with popularizing the smoking of tobacco at the English court, and it is enthusiastically recommended in his protégé Edmund *Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. References to tobacco, and depictions of smoking (generally, using clay pipes), occur in the writings of several playwrights, including Ben *Jonson (‘He does take this same filthy roguish tobacco, the finest, and cleanliest!’, Every Man in his Humour 1.4): *Middleton and *Dekker’s The Roaring Girl even puts a tobacconist’s shop on the stage. The Shakespeare canon, however, is strictly a non-smoking area: there are no occurrences of the word ‘tobacco’ in Shakespeare’s works, nor appropriate usages of the allied terms ‘smoke’, ‘smoking’, or ‘pipe’.

Numerous late 16th-century woodcuts and paintings portray pipe-smoking, but the widespread use of tobacco had many opponents, the first important English book against it being Opinions of the Late and Best Physicians Concerning Tobacco (1595). The most notable anti-tobacconist was King *James who, in A Counterblast to Tobacco (1604), called smoking ‘a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs and in the black stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless’.

In 1614 the Star Chamber imposed a tax on tobacco and in 1619 the Privy Council forbade its planting in England, to safeguard the monopoly of the Virginia colonists.

Mairi MacDonald

Tolstoy, Count Leo (Lev) Nikolayevich (1828–1910), Russian novelist, frequently compared to Shakespeare for his universality, invention of character, steadiness of vision, breadth of life represented, and devotion to truth. Yet Tolstoy is probably the most implacable dissenter to Shakespeare’s reputation in modern times, complaining (in Shakespeare and the Drama, 1904) of his unnaturalness, implausibility, cheap theatricality, aristocratic sympathies, moral indifference, and hyperbolic language—preferring, for example, the source play King Leir to Shakespeare’s. G. Wilson *Knight’s Shakespeare and Tolstoy (1934) considers the objections, while George Orwell’s essay ‘Lear, Tolstoy, and the Fool’ (1947) argues for a degree of identification on Tolstoy’s part. It is ironic that Tolstoy’s own final flight with his daughter Alexandra (Sasha) and death in a stationmaster’s cottage in Astopovo resemble nothing more than the tragic fate of Lear and Cordelia.

Tom Matheson

‘Tomorrow is Saint Valentine’s day’, sung by Ophelia in Hamlet 4.5.47. As with *‘How should I your true love know’, a tune traditionally sung at Drury Lane in the late 18th century (‘The Soldier’s Life’) can be traced back to Shakespeare’s time, but in this case without any link between lyrics and tune title.

Jeremy Barlow

Tooley, Nicholas (?1582/3–1623), actor (King’s Men by 1605 to 1623). If Edmond’s identification is correct, Tooley was a wealthy Anglo-Flemish orphan whose Warwickshire relatives Shakespeare would have known from childhood. In his will Tooley thanked Cuthbert *Burbage’s wife for her ‘motherly care’ of him. Augustine *Phillips in his will called Tooley his ‘fellow’, which indicates that Tooley was by then a sharer in the King’s Men. A surviving annotated cast list indicates that Tooley played Ananias in Jonson’s The Alchemist and Corvino in Jonson’s Volpone. The 1619 King’s Men patent names Tooley after *Heminges, Burbage, Condell, and *Lowin and the 1623 Folio, published after his death, names him as principal actor.

Gabriel Egan

Topsell, Edward (1572–c. 1625), cleric and writer on natural history. He compiled The History of Four-Footed Beasts (1607) and The History of Serpents (1608). These exhaustive accounts of prevailing zoological traditions provide much of the beast lore found in Shakespeare’s plays, along with illustrations of *monsters, half-man, half-beast, akin to Caliban’s description in The Tempest.

Cathy Shrank

‘To shallow rivers, to whose falls’, sung by Sir Hugh Evans in The Merry Wives of Windsor 3.1.16, misquoting part of *Marlowe’s song ‘Come live with me and be my love’; the lyrics have been wrongly attributed to Shakespeare because of their inclusion in *The Passionate Pilgrim. The original tune survives, and was used for several *broadside ballads.

Jeremy Barlow

Tottel, Richard (d. 1594), author of an anthology of poetry called Songs and Sonnets popularly known as Tottel’s Miscellany, published in 1557. It included work by *Chaucer, Wyatt, and Surrey and was obviously familiar to Shakespeare. The Gravedigger’s song in Hamlet derives from a poem in the Miscellany, and Slender refers to it as the ‘Book of Songs and Sonnets’ in The Merry Wives of Windsor (1.1.181–2).

Jane Kingsley-Smith

Touchstone is a court jester who follows Rosalind and Celia to the forest of *Ardenne in As You Like It.

Anne Button

tragedy. The rise of modernity coincided with the enthusiastic rediscovery of the classics and a renewed interest in tragedy, the most theorized and admired dramatic form since Aristotle identified its main structural features in his Poetics. *Seneca was the most widely imitated model among early English playwrights, after the example set by Thomas Sackville and Thomas Norton’s Gorboduc (1565) and Thomas *Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy (1592). Imitation of classical models was however never slavish or pedantic. In his Apology for Poetry, the classicist Sir Philip *Sidney praised Gorboduc for ‘climbing the heights of Seneca’s style’, but regretted the interference of native influences which spoil the formal purity of the original. The main influences Sidney had in mind are the *English morality play and the de casibus tradition, a typically medieval form best exemplified by the tragic narrative accounts of the fall of illustrious men collected in The *Mirror for Magistrates, one of the most popular sources of tragic plots used by Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

Shakespeare was affected by both the classic and the native traditions, but he consistently departed from received conventions and aimed for a more sophisticated realism by ‘suit[ing] the action to the word, the word to the action’ (Hamlet 3.2.17–18). Shakespeare notoriously disregarded the Aristotelian doctrine of the three unities of time, space, and action. He also put more emphasis on character than on fate by reducing the omnipresent gods of classical tragedy to significant but relatively rare manifestations of the supernatural, such as the *ghost in Hamlet or the *witches in Macbeth. The gods are invoked but they remain silent. Unlike classical tragedy, Shakespearian tragedy often denies its audience cathartic relief. In Shakespeare’s tragedies, recognition is not necessarily followed by redemption. *Johnson famously claimed to find Cordelia’s death at the end of King Lear unbearable and to prefer the happy ending devised by Nahum *Tate for its 1681 adaptation.

Shakespeare departed as radically from the de casibus tradition as from his classical models. Far from exemplifying the medieval notion of the ‘Wheel of Fortune’, which denies human agency, Shakespeare’s tragedies suggest that catastrophe ultimately proceeds from his characters’ actions. Psychological realism is therefore heightened at the expense of tragic irony. The result of Shakespeare’s highly experimental use of earlier dramatic conventions is a corpus of tragedies as diverse as Titus Andronicus and Romeo and Juliet or Hamlet and Coriolanus, or as innovative as Othello, a domestic tragedy featuring the first black tragic hero in English dramatic literature.

Shakespeare’s mature tragedies are often interpreted as the dramatist’s response to the political unrest and ideological uncertainties which characterized the last years of *Elizabeth I’s reign and the period following *James I’s accession to the throne of England. The radical quality of Shakespeare’s tragic imagination is particularly evident in King Lear, where the King’s painful and gradual realization of his fallibility and frailty represents a clear challenge to the basic tenets of absolutism and the doctrine of the divine right of kings, as expounded by James I in Basilikon Doron (pub. 1599).

Sonia Massai

Tragedy of King Lear, The. See centre section.

Tragical History of King Richard III, The. See centre section.

tragicomedy is a Renaissance invention. Aristotle never mentioned it in his Poetics and Cicero expressed his disapproval of any ‘mixed-mood’ dramatic form in his famous maxim ‘turpe comicum in tragedia et turpe tragicum in comedia’ (the comic is abhorrent in tragedy and the tragic is abhorrent in comedy).

*Cinthio (1504–73) and Giovanni Battista Guarini (1538–1612) first theorized tragicomedy in connection with the pastoral tradition. Some English dramatists retained the pastoral setting: see, for example, *Fletcher’s The Faithful Shepherdess (1609–10), Samuel *Daniel’s Hymen’s Triumph (1615), or Ben *Jonson’s Sad Shepherd (1629). Others, however, concentrated on the double structure of tragicomedy, which often stretches the plot to the limits of verisimilitude by hinging on a sudden change of fortune which leads to the comic resolution of a potentially tragic situation.

Despite adverse criticism, such as *Sidney’s, who dismissed ‘mongrel tragicomedy’ as a corruption of the formal purity of the classical forms, Shakespeare ‘flirted’ with both forms of tragicomedy. In The Winter’s Tale, the comic resolution of a potentially tragic situation takes place against the backdrop of pastoral Bohemia. In Measure for Measure, on the other hand, Shakespeare retains the double structure of tragicomedy but dispenses with the pastoral setting.

Sonia Massai

Tranio, Lucentio’s servant in The Taming of the Shrew, takes on his master’s identity at his request (see 1.1.196–215).

Anne Button

transcripts. Shakespeare’s original *‘foul paper’ manuscripts would probably have been transcribed, either by the playwright or by a professional scribe, to provide a ‘fair copy’ of the play for use in the playhouse. Other manuscript copies may also have been in circulation. The publisher Humphrey *Moseley speaks of the seemingly common practice of plays being ‘transcribed’ by the actors for their ‘private friends’.

Eric Rasmussen

translation, the rendering of Shakespeare texts into another language, is inalienably part of the process whereby Shakespeare has been, and is being, received in non-English-speaking countries. Hence Shakespeare translation has not only (1) linguistic but also (2) theatrical and cultural—even political—aspects. As translations multiply throughout the world, each language offers its own resistance or adaptability to Shakespeare’s ways with his native language; and each country, as part of its cultural programme, has its own history of Shakespeare translation. Within that context, each individual translator becomes an interpreter of Shakespearian texts, with results which vary from faithful imitation to radical *adaptation.

Inga-Stina Ewbank, rev. Erin Sullivan

trapdoors. Access to the understage ‘hell’ was provided by a trapdoor set in the floor of the stage, probably near the centre. Hellish characters ascended and descended through this trapdoor, most easily by provision of a ladder placed underneath the hole, although the technology for a mechanical elevator platform was available. Left open, the trapdoor could also make a useful grave such as that needed for Ophelia’s burial in Shakespeare’s Hamlet 5.1.

Gabriel Egan

travel, trade, and colonialism. Travel tales of voyages constituted one of the largest categories of popular reading of Shakespeare’s period. To Richard *Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations (1 vol., 1589; 3 vols., 1599–1603), with its title page announcing the intention of celebrating the ‘navigations, voyages, traffiques and discoveries of the English nation’, can be added those by William Biddulph (1609), John Cartwright (1611), Anthony Sherley (1613), and William Lithgow (1614) to the Orient, North Africa, and Asia, and by Sir John Hawkins (1569), Thomas Hariot (1588), Walter *Ralegh (1596), and John Smith (1608) to the New World. Works by the Frenchman Cartier (1580), the merchant of Venice Cesare Federici (1588), and the Dutchman Jan Huyghen van Linschoten (1598) were available in translation.

Shakespeare’s plays abound with references to travel literature. The tale related by Othello is a superb encapsulation of many of the key elements of the genre, including ‘Of being taken by the insolent foe | And sold to slavery, of my redemption thence, | And portance in my traveller’s history…and of the cannibals that each other eat, | The Anthropopaghi, and men whose heads | Do grow beneath their shoulders’ (Othello 1.3.136–44). The prediction made by the host of the Garter Inn that Falstaff will ‘speak like an Anthropophaginian unto thee’ (The Merry Wives of Windsor 4.5.8) can be traced back to the dubious but much-read travel accounts by the 14th-century Sir John Mandeville, still treated as authoritative well into the 16th century, while the story told by the First Witch about the woman whose ‘husband’s to Aleppo gone, master o’the Tiger’ (Macbeth 1.3.6) might well refer to public awareness of the tribulations of the sailors on a vessel of that name that had sailed for Aleppo in December 1604 and had returned in June 1606.

Tales are also discounted. At the sight of strange shapes bringing in a banquet, Sebastian observes that he will from now on believe in unicorns as well as that there is in Arabia a tree in which a phoenix reigns—to which Antonio, the usurping Duke of Naples, responds: ‘Travellers ne’er did lie, | Though fools at home condemn ’em’ (The Tempest 3.3.26–7): itself, perhaps, an echo of the saying later collected in Camden’s Remains (1614): ‘Old men and travellers may lie by authority.’

The majority of references to voyages highlight the benefits, notably the economic. Egeon tells the Duke of Ephesus that ‘Our wealth increased | By prosperous voyages I often made’ (The Comedy of Errors 1.1.39–40); Titania refuses to hand over the changeling boy to Oberon because the child’s dead mother would sometimes return to her with goods ‘As from a voyage, rich with merchandise’ (A Midsummer Night’s Dream 2.1.134). Panthino criticizes his master because he lets his son stay at home while ‘other men of slender reputation | Put forth their sons to seek preferment’ by sending them ‘to discover islands far away’ (The Two Gentlemen of Verona 1.3.6–9). When Falstaff woos both Mistress Page and Mistress Ford he is candid about his objectives: ‘I will be cheaters to them both, and they shall be exchequers to me. They shall be my East and West Indies, and I will trade to them both’ (The Merry Wives of Windsor 1.4.62–5).

References to trade should be read in the context of the emergence, in England, of arguments in favour of mercantilism and for a break with the times of Drake, Frobisher, Hawkins, Ralegh, and others, several of whom were keener on shipping slaves to New World colonies of other European nations than in trading. Profit, for them, was in plunder and in privateering—often at the patriotic expense of other Europeans.

That central difference thus calls into question the validity of speculations concerning the playwright’s views on colonialism. England, in Shakespeare’s lifetime, was not a colonial power. More importantly, there was no desire, at that time, to embark on such a project. Even though Grenville had (1574) proposed that South America be colonized, England had only one colony—Bermuda (1609) in the West Indies. Attempts on the North American mainland at Roanoke (1587) had failed and the settlement at Virginia (1607) did not begin to take root until 1612. While the Levant Company had a presence in Constantinople and in cities such as Aleppo, and the English East India Company in Agra, the ambassadors sent to the Ottoman, Persian, and Mughal rulers went there not as dispossessors but as supplicants begging for permission for the right to trade—often in contest with other Europeans.

The plays mirror that imperative of being able to discriminate: not only between persons—‘Which is the merchant here, and which the Jew?’ (The Merchant of Venice 4.1.172)—but also between categories (Amazons; pagans; cannibals; savages; etc.) and geographical spaces (Africa; the Orient; India; the New World; the Antipodes). It is more likely that the origins of the stories about these categories are in the Greek and Roman classics (themselves infused with Arabic elements) rather than directly traceable to the travel accounts.

References to Africa illustrate the reliance on antecedent classical sources. Egypt is known because of the Nile, the pyramids, and serpents. Then there are the ‘black Ethiopes’—a favourite image for making comparisons between women: Sylvia’s fairness ‘Shows Julia but a swarthy Ethiope’ (The Two Gentlemen of Verona 2.6.26); the sonnet written by Dumaine: ‘Thou for whom great Jove would swear | Juno but an Ethiop were’ (Love’s Labour’s Lost 4.3.115–16). But if Rosalind’s charge that she is being defied ‘Like Turk to Christian. Women’s gentle brain | Could not drop forth such giant-rude invention, | Such Ethiop words, blacker in their effect | Than in their countenance’ (As You Like It 4.3.34–7) is the often-cited view, then recall that Thaisa describes to King Simonides ‘A knight of Sparta…| And the device he bears upon his shield | Is a black Ethiop reaching at the sun’ (Pericles 6.18–20).

The distinctions, as well as the consequences which follow, are clearest with regard to the Indies. The ‘dead Indian’ the English will pay tenfold to see yet ‘will not give a doit to relieve a lame beggar’ (The Tempest 2.2.30–3) and Othello’s ‘base Indian’ who ‘threw a pearl away | Richer than all his tribe’ (Othello 5.2.356–7) are probably from the New World. Their subcontinental counterpart is seen as much more dangerous: the image of ‘the rude and savage man of Ind | At the first op’ning of the gorgeous east, | Bows…his vassal head and, strucken blind, | Kisses the base ground with obedient breast’ (Love’s Labour’s Lost 4.3.223). Still, against cultural and religious difference is ranged the tangible wealth of ‘metal of India’ (Twelfth Night 2.5.12) that makes trade worthwhile: Troilus casts himself in the role of ‘merchant’ who will negotiate with Pandarus in order to succeed with Cressida, whose ‘bed is India; there she lies, a pearl’ (Troilus and Cressida 1.1.103, 100). Finally, not only can the Duke of Norfolk claim that, in their triumphant splendour at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, the English had ‘Made Britain India’; there is also the observation that, having married Anne Boleyn, ‘Our King has all the Indies in his arms’ (All Is True (Henry VIII) 1.1.21, 4.1.45).

Then there are the differences between Indians and Turks. Turks are the common enemy of Christians. The Bishop of Carlisle reminds that ‘banished Norfolk fought | For Jesu Christ in glorious Christian field, | Streaming the ensign of the Christian cross | Against black pagans, Turks, and Saracens’ (Richard II 4.1.83–6). Henry hopes that the son born from his marriage with Catherine will ‘compound a boy, half-French, half-English, that shall go to Constantinople and take the Turk by the beard’ (Henry V 5.2.205–7). Indeed he can already, as the newly crowned King at the end of 2 Henry IV, confidently forget how his father had acquired the crown by observing: ‘This is the English not the Turkish court; | Not Amurath [Murad] an Amurath succeeds | But Harry Harry’ (5.2.47–9). While Turks, in Shakespeare’s texts, are never once referred to by the epithet of ‘the terrible Turk’ that will later become common, there is at least one reference to a predecessor view, that of the Turk as liar. Iago defends his lie to his wife Emilia: ‘Nay, it is true, or else I am a Turk’ (Othello 2.1.116).

All in all, it is the complexity of the differences that matter. The Christian Duke of Venice can, when it suits him, require a ‘gentle answer’ from that alien Other, Shylock the Jew. Such behaviour is not to be expected ‘From stubborn Turks and Tartars never trained | To offices of tender courtesy’ (The Merchant of Venice 4.1.31–2). It is fascinatingly fitting, then, that it is a differently placed Other, that in-between figure the *Moor, without whose military skill Venice would be in peril, who can ask the brawlers Iago and Cassio: ‘Are we turned Turks, and to ourselves do that | Which heaven hath forbid the Ottomites? | For Christian shame, put by this barbarous brawl’ (Othello 2.3.163–5).

Kenneth Parker

travellers are robbed by Sir John and his companions, 1 Henry IV 2.2.

Anne Button

Travers gives Northumberland the first news of his son Hotspur’s death, 2 Henry IV 1.1.34–48.

Anne Button

Trebonius is one of the conspirators in Julius Caesar, based on Caius Trebonius, consul in 45 bc.

Anne Button

Tree, Sir Herbert Beerbohm (1853–1917), English actor-manager, in whose early career Shakespeare barely featured, but whose sixteen sumptuous Shakespearian revivals were the centrepiece of his management at Her/His Majesty’s theatre (1897–1915).

Tree defended his principles of Shakespearian production in ‘The Living Shakespeare: A Defence of Modern Taste’ (in Thoughts and After-Thoughts, 1913): historically accurate spectacular theatre achieved with all the resources and care lavished on modern plays. Thus Tree engaged antiquarians, Academicians (Alma-Tadema), scenic artists (Joseph Harker), pageant masters (L. N. Parker), and crowd-commandants (Louis Calvert) to achieve some of the most spectacular revivals of Shakespeare ever. Though vulnerable amongst so much ‘scenic embellishment’, Tree upheld the importance of ‘all-round casts’ and in productions such as Julius Caesar (1898), with himself as Mark Antony, Louis Calvert as Casca, Lewis Waller as Brutus, and Frank McLeay as Cassius, he achieved an effective synthesis of all the theatre arts. Elsewhere he erred—far—on the side of excess. The interpolation of ‘The Signing of Magna Carta’ in King John (1899) was not without precedent and could be forgiven; Shylock’s extended—room by room—search of his house for his missing daughter and Malvolio’s entourage of four miniature, aping Malvolios could not be.

For Tree public taste was the ultimate arbiter and he pointed to the long runs and huge attendances (Julius Caesar 240,000, King John 170,000, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream 220,000 in London alone). Not that Tree was indifferent to the higher claims upon him as a leader of his profession; he undertook tours of Germany (1907) and America (1915–16) and in 1905 inaugurated his annual Shakespeare Festival in which six plays were performed in six days, including productions by *Benson and *Poel. A brief excerpt of Tree’s King John, the first Shakespeare film, is included in Silent Shakespeare (BFI, 1999). The Tree archive at the University of Bristol is a major resource.

Richard Foulkes

tribunes, Roman. They receive orders from Rome, Cymbeline 3.7.

Anne Button

trimeter, a verse line of three feet, used by Shakespeare as an occasional variation from pentameter, or occasionally in songs or the bad verse of lovesick characters (Hamlet 2.2.116–19).

George T. Wright

Trinculo is Alonso’s jester in The Tempest. He and Stefano (Alonso’s butler) are separated from the rest of the royal party when they are shipwrecked. They become drunk and plot against Prospero with Caliban.

Anne Button

trochee, a metrical unit (‘foot’) comprising one stressed syllable followed by one unstressed syllable. Shakespeare’s trochaic verse appears in many dramatic songs and in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, e.g. ‘Hearts remote yet not asunder’. Trochees are often used as a variation in iambic verse, especially in the first foot or after a midline break in syntax: ‘Spūr thĕm | to youthful work, | rĕin thĕm | from ruth’ (Troilus and Cressida 5.3.48).

Chris Baldick/George T. Wright

Troilus and Cressida See centre section.