a

Aaron, a *Moor and Tamora’s lover, is ultimately sentenced to be buried and starved, Titus Andronicus 5.3.

Anne Button

Abbess. She reveals herself to be Emilia, mother of the Antipholus twins, at the end of The Comedy of Errors.

Anne Button

Abbott, E(dwin) A(bbott) (1838–1926), English headmaster and grammarian, who addressed the first meeting of the New Shakespeare Society (13 March 1874). His A Shakespearian Grammar: An Attempt to Illustrate Some of the Differences between Elizabethan and Modern English (1869, repr. 1966) is an important attempt to describe Elizabethan syntax and idiom.

Tom Matheson

Abergavenny, Lord. He complains about Wolsey’s pride and is imprisoned alongside Buckingham in All Is True (Henry VIII) 1.1. The historical figure was George Neville, 3rd Baron Abergavenny (c. 1461–1535).

Anne Button

Abhorson, an executioner, defends his profession in Measure for Measure 4.2 and attempts to rouse drunken Barnadine for execution, 4.3.

Anne Button

‘above’. About half of Shakespeare’s plays need an elevated playing space which is often signalled by a stage direction of the kind ‘enter above’, and most of these use this location just once or twice. An actor appearing ‘above’ is usually to be thought of as appearing at a window, or upon the walls of a castle or fortified town. Contemporary accounts and drawings (most clearly the de Witt drawing of the *Swan) indicate a balcony set in the back wall of the stage which could be used as a spectating position but also would be ideal to provide the occasional ‘above’ acting space.

Gabriel Egan

Abraham (Abram), Montague’s servant, participates in a fight in Romeo and Juliet 1.1.

Anne Button

academic drama. See university performances.

Achilles, the treacherous champion of the Greek army (he appears in a more sympathetic light in *Homer’s Iliad), instructs his followers to kill the unarmed Hector, Troilus and Cressida 5.9.

Anne Button

act and scene divisions. Of the original quartos of Shakespeare’s plays, none is divided into numbered scenes (although in Q1 Romeo and Juliet a printer’s ornament occasionally appears where new scenes begin) and only Othello (1622) is divided into acts. In the First Folio, nineteen of the plays are divided into acts and scenes, and another ten are divided into acts. Nicholas Rowe’s edition (1709) was the first to divide all of the plays into numbered acts and scenes.

Division into scenes was a structural element of early English plays—a new scene began whenever the stage was clear and the action not continuous—but division into acts was a later convention, perhaps adopted from classical drama. Although very few plays written for the adult dramatic companies before 1607 are divided into acts, nearly every one of the extant printed plays written for those companies thereafter is divided into five acts. Gary Taylor has suggested that the transition to act-intervals occurred when the adult companies moved from outdoor to indoor theatres (the King’s Men acquired the Blackfriars playhouse in August of 1608). Pauses between acts would not only have been better facilitated in indoor theatres, but might also have been required so that candles could be trimmed. Shakespeare’s later plays were thus apparently written for a different convention from his early and middle ones.

Eric Rasmussen

acting, Elizabethan. The Elizabethan word for what we call acting was ‘playing’, and the word ‘acting’ was reserved for the gesticulations of an orator. We have little direct evidence about the style of Elizabethan acting, although a few general principles can be derived from the conditions of performance. The relative shortness of rehearsal periods and the large number of plays in the repertory at any one time suggest that an actor was not likely to think of his character as having a unique and complex human psychology in the way which, in our time, the *Stanislavskian technique encourages. Likewise, the distribution of parts as individual rolls of paper giving only the particular speeches needed for one character suggests that what we think of as dramatic interaction was less important than the individual’s interpretation of his speeches. Modern ensemble acting requires lengthy rehearsals which were unknown on the early modern stage. But this should not be taken as evidence that the acting was mere declamation without emotion. When the King’s Men played Othello at Oxford in 1610 an eyewitness was moved to report that Desdemona ‘killed by her husband, in her death moved us especially when, as she lay in her bed, her face alone implored the pity of the audience’. Likewise Simon Forman’s records of performances of Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale, Macbeth, and a play about Richard II clearly express his enjoyment of the intensity of the emotional experience, and hence the quality of the acting. The mere fact that boys played great tragic roles such as a Cleopatra, Desdemona, Hermione, and Lady Macbeth indicates that a degree of unrealistic formalism (symbolic gestures and convention) must have been used, but scholars do not agree about precisely how ‘naturalistic’ or ‘formalistic’ the acting usually was, or whether perhaps some mixed style was used.

There was hardly a professional acting tradition in existence in 1576 when James Burbage built the Theatre, and until the early 1600s most actors were men who had taken up this career having first trained in something else. Once the profession was established the system of apprenticeship must have helped systematize an actor’s training, although without a governing guild practice might have varied greatly from one master to another. Acting was taught as part of a standard grammar-school education and of course actors had to be literate, so despite the apparent low status of the profession actors were amongst the better-educated Elizabethans. Scholars have looked to the education system, and especially the instruction in oratory, for evidence of the acting style of the period; educational policy at least is well documented. Bernard Beckerman thought that the styles and conventional gestures of the Elizabethan orator and actor were essentially the same but found manuals of oratory rather vague: a number of gestures were offered to accompany a particular emotion and the individual orator was left to choose whichever best suited the occasion.

Another source of information about acting styles is the drama itself, and the most overused piece of evidence is Hamlet’s advice to the players (3.2.1–45) which includes ‘Speak the speech … trippingly on the tongue’, ‘do not saw the air too much with your hand’, and avoid imitating those who have ‘strutted and bellowed’ on the stage. This does not tell us much, and indeed the conscious contradiction of the general and transcendent (‘hold as ’twere the mirror up to nature, to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image’) and the particular and contingent (‘[show] the very age and body of the time his form and pressure’) makes this if anything an evasion of detailed instruction in acting style. Commentators have relied heavily upon Hamlet’s advice because we have no direct description of Elizabethan acting.

Despite the lack of direct evidence, certain trends which impinged upon acting can be traced across the period. The drama of the 1570s used strong rhyme and rhythm (especially the ‘galloping’ fourteen-syllable line) which gave an actor little scope for personal interpretation, whereas Marlowe’s looser verse style and increasingly subtle characterization gave the Admiral’s Men new opportunities for virtuoso acting. Stable long-term residences at the Rose and the Globe after 1594 allowed a star system to develop with Edward Alleyn for the Admiral’s and Richard Burbage for the Chamberlain’s Men being the most highly praised actors of their time. T. W. Baldwin developed a complex model of the character types (‘lines’) which were the special skills of particular actors of the period but other scholars feel that flexibility, not specialization, was the most valued attribute in an actor. Whether Shakespeare ever got the performances he wanted is uncertain. Shakespeare’s characters use acting as a metaphor for public behaviour of all kinds but, as M. C. Bradbrook noted, the descriptions (‘strutting player’, ‘frets’, ‘wooden dialogue’) are seldom complimentary.

The differences in conditions at different venues appear to have had an effect on the acting. Indoor theatres were smaller than the open-air amphitheatres and had less extraneous noise, so actors could afford to soften their voices and make smaller physical gestures. Players at the northern playhouses, especially the Fortune and Red Bull, were more commonly attacked for exaggerated acting once the private theatres had developed their own subtle style. Also, an actor in an amphitheatre is effectively surrounded on all sides by spectators and may choose to keep moving so that everyone has a chance to see him. The indoor theatres, however, had a greater mass of spectators directly in front of the stage and this probably encouraged playing ‘out front’ rather than ‘in the round’ as we would now call it. Adjusting between the two modes must have been fairly easy for the actors, however, as on tour they were unlikely to find many venues which provided the ‘in-the-round’ experience of the London amphitheatres.

Gabriel Egan

acting profession, Elizabethan and Jacobean. The Elizabethan word for an actor was ‘player’ and there were three classes: the sharer, the hired man, and the apprentice. The nucleus of the company was the sharers, typically between four and ten men, who were named on the patent which gave them the authority to perform and which identified their aristocratic patron. The sharers owned the capital of the company, its playbooks and costumes, in common and shared the profits earned. All other actors were the employees of the sharers. The sharers were not necessarily the finest actors but they would have to bring a significant contribution to the company in the form either of capital or, as in the case of Shakespeare, writing ability. The sharing took place after the rent on the venue—often simply consisting of the takings from the galleries—had been paid and the hired men had received their wages. There was no guild system in place to regulate the industry, so an apprentice was in the unusual position of being legally apprenticed in the secondary trade practised by the individual sharer who was his master.

The sharers of London companies selected a new play by audition reading and, if purchased, they would rehearse it in the morning while playing items from the current repertory in the afternoon. The inconclusive evidence from Henslowe’s account book suggests that at least two weeks were allowed for rehearsal of a new play, including time needed for the player to privately ‘study’ (memorize) his part. With no cheap mechanical means of reproducing an entire play, players were issued with rolls of paper containing only their own lines plus their cues. This practice and the short rehearsal periods suggests that acting skill was largely considered to reside in expressing the meanings and emotions in one’s part rather than reacting to the speeches of others.

The majority of players were hired men, and amongst these there was not a strict distinction between what we now call ‘front of house’ and ‘stage’ work: an entrance-fee gatherer or costumer might well be expected to take a minor role at need, and those providing musical accompaniment might have to portray onstage musicians. Fee-gathering was the only job open to women as well as men; apart from ambiguous evidence concerning Middleton and Dekker’s The Roaring Girl (1611) there is nothing to suggest that women ever acted. Usually the apprentices played the female roles in the drama but because of the anomalous lack of a guild governing the acting profession we do not know the precise extent of an apprentice’s responsibilities, or if indeed any standard arrangements existed other than the customary provision of board, keep, and training.

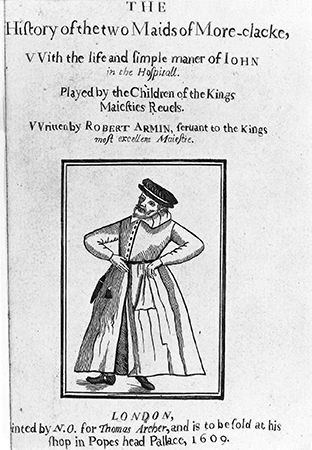

There is little evidence that players were typecast although a dramatist attached to a company, as Shakespeare was, would have thought about his human resources during composition. However, there was a distinct position of ‘clown’ or ‘fool’ in each of the major companies and Richard Tarlton of the Queen’s Men and William Kempe and later Robert Armin of the Chamberlain’s Men had roles written to suit their abilities and did not perform in plays which lacked a ‘clown’ or ‘fool’ character. The emergence of actor ‘stars’ in the early 1590s appears to be related to the increasingly long residences at London playhouses which allowed audiences to follow the particular development of an individual’s career. Star actors could expect to take just one of the major roles in a play, but other actors, and especially hired men, would be expected to ‘double’ as needed.

Gabriel Egan

act-intervals. See act and scene divisions.

Act to Restrain Abuses of Players (1606), a parliamentary bill introducing a fine of £10 for each occasion upon which an actor ‘jestingly or profanely’ spoke the name of God or Jesus Christ. Plays written after this date have little or no such profanity, and plays already written show alteration of the offending phrases when revived, although the original unexpurgated text could safely be printed. Words such as ‘zounds’ (a contraction of ‘God’s wounds’) could be replaced by ‘why’ or ‘come’, and exclamations such as ‘O God!’ softened to ‘O heaven!’

Gabriel Egan

‘A cup of wine that’s brisk and fine’, sung by Silence in 2 Henry IV, 5.3.46; the original tune is unknown.

Jeremy Barlow

Adam, Oliver’s servant in As You Like It, helps Orlando escape into the forest of Ardenne.

Anne Button

Adams, J(ohn), C(ranford) (1903–86), American scholar, author of The Globe Playhouse: Its Design and Equipment (1942, 2nd edn. 1961), giving considerable prominence to the inner and the upper areas of the stage, now largely superseded. He was responsible for a reconstruction of the Globe for the Hofstra College Shakespeare Festival.

Tom Matheson

Adams, Joseph Quincy (1881–1946), American scholar, first director of the Folger Shakespeare Library (1934) and an editor of the New Variorum edition of Shakespeare. He was author of A Life of William Shakespeare (1916) and, using Revels records, Shakespearean Playhouses: A History of English Theatres from the Beginnings to the Restoration (1917).

Tom Matheson

adaptation. The practice of rewriting plays to fit them for conditions of performance different from those for which they were originally composed, in ways which go beyond cutting and the transposition of occasional scenes. Even leaving aside the questions as to whether Shakespeare’s use of dramatic sources itself constitutes adaptation (e.g. whether King Lear can be regarded as an adaptation of The True Chronicle History of King Leir), or whether his own *revisions to plays such as Hamlet and King Lear might be classed as such, the altering of Shakespeare’s scripts for later revivals certainly dates to before the publication of the *First Folio, which prints Macbeth in a form revised by Thomas *Middleton.

The adaptation of Shakespeare was at its most widespread, however, between the Restoration in 1660 and the middle of the 18th century (see Restoration and eighteenth-century Shakespearian production), when drastic changes in the design of playhouses (with the inception of elaborate changeable scenery), in the composition of theatre companies (with the advent of the professional actress), and in literary language and tastes (with the vogue for French neoclassicism, and its patriotic aftermath) motivated many playwrights and actor-managers to stage Shakespearian plays in heavily rewritten forms. The pioneer of adaptation was Sir William *Davenant, whose The Law against Lovers (1662) transplants Beatrice and Benedick into a sanitized Measure for Measure cast largely in rhyming couplets: this was followed by his immensely popular semi-operatic versions of Macbeth (1664) and The Tempest (1667), the latter co-written with one of his most successful followers in this vein, John *Dryden, who went on to write his own Antony and Cleopatra play All for Love (1677) and alter Troilus and Cressida (1679). Other major adaptors include Nahum *Tate (most famous for giving King Lear back the happy ending it had enjoyed in its sources, in 1681), Colley *Cibber, and David *Garrick.

An increasing veneration for Shakespeare’s original texts had brought the practice of adaptation into disrepute in England by the middle of the 19th century, and while certain less canonical plays have regularly been retouched for performance since (notably the Henry VI plays, condensed at different times by both John *Barton and Adrian *Noble for the *Royal Shakespeare Company alone), full-scale adaptation has in modern times been more frequently associated with the work of translators fitting Shakespeare’s plays to performance traditions far removed from his own, and with the transformation of his plays into *ballets, *operas, and *films.

Although many adaptations of Shakespeare may now seem objectionable, or at best merely quaint (simplifying his language, plotting, characterization, and morality alike), some constitute intelligent and engaged contemporary critical responses to his plays, and a few more recent playwrights have continued to use the medium as a form of practical Shakespeare criticism, notably Charles *Marowitz. In certain cases successful adaptations or offshoots can affect the way the Shakespearian source itself is read and performed; Tom *Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead has left an indelible mark on the performance of Hamlet’s two school friends in modern productions, and Jane Smiley’s suggestion in A Thousand Acres of an incestuous back story in King Lear has resurfaced in some ‘straight’ productions of Shakespeare’s tragedy.

With the global expansion of interest in Shakespeare in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has also come a greater focus on the relationship between the processes of translation and adaptation. In 2012 the *World Shakespeare Festival and *Globe to Globe Festival featured many productions, both non-English and English, adapted from one or more Shakespeare texts and made into something wholly new. This appreciation for new work based on Shakespearian source material seems set to continue: for 2016 the Hogarth Press, an imprint of Vintage, is planning a series of Shakespeare re-tellings by prominent 21st century novelists including Margaret Atwood (The Tempest), Jo Nesbø (Macbeth), Tracy Chevalier (Othello), and Gillian Flynn (Hamlet).

Michael Dobson, rev. Erin Sullivan

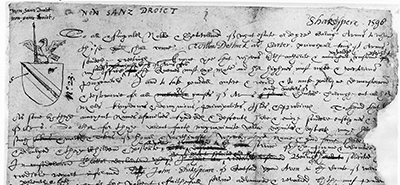

Addenbrooke, John, a ‘gentleman’ whom Shakespeare sued in the Stratford court of record for a debt of £6 in 1608. The case dragged on from 17 August 1608 to 7 June 1609. Addenbrooke was arrested but freed when Thomas Hornby, a blacksmith, stood surety for him. A jury awarded Shakespeare his debt and 24s. in costs which he tried to recover from Hornby as Addenbrooke could not be found.

Stanley Wells

Addison, Joseph (1672–1719), poet, playwright, and essayist, most famous as an author, with Sir Richard Steele, of the Spectator papers. In Spectator 40 he voiced one of the first attacks on Nahum Tate’s adaptation of King Lear, in particular its addition of a happy ending and use of poetic justice.

Jean Marsden

Admiral’s Men, the players of Charles Howard, second Lord Effingham—made Lord Admiral in 1585 and Earl of Nottingham in 1597—who were the main rivals of Shakespeare’s company. Also known as the Lord Howard’s Men (1576–85), the Earl of Nottingham’s Men (1597–1603), Prince Henry’s Men (1603–12), and Elector Palatine’s Men (1613–24), their greatest asset in the 1590s and 1600s was the actor Edward Alleyn, whose stepfather-in-law Philip Henslowe owned the Rose and Fortune playhouses used by the company.

Gabriel Egan

Adonis. See Venus and Adonis.

Adrian. (1) A Volscian who hears from the Roman Nicanor that Coriolanus has been banished from *Rome, Coriolanus 4.3.

(2) A lord shipwrecked with Alonso on Prospero’s island in The Tempest.

Anne Button

Adriana, wife to Antipholus of Ephesus in The Comedy of Errors, is unable to distinguish between him and his twin.

Anne Button

advertising. The use of Shakespeare in advertising can be traced back to the adoption of an image based on the *Chandos portrait as the publisher Jacob Tonson’s trademark in 1710. More recently, some of the more famous characters from Shakespeare’s plays have provided manufacturers with richly associative brand names (the tobacco sector alone has given us Hamlet cigars, Romeo Y Julietta panatellas, and Falstaff cigars). Shakespeare’s characters also supply television commercials with conveniently familiar dramatic situations which can be rapidly established and then usually debased, for comic effect. Thus King Lear, ready to divide his kingdom, overlooks his two daughters who speak of love and loyalty for a third who offers a supply of ice-cold drinks (Coca-Cola, USA, 1997). Romeo woos Juliet, but only after her rumbling stomach has been prevented from joining in the dialogue (Shreddies Cereals, UK, 2000). Hamlet, about to meditate on Yorick’s skull, drops it, improvises a football pass, and is endorsed as a lager drinker who ‘gets it right’ (Carling Black Label, UK, 1986). True Shakespearian dialogue is rarely used, but longer speeches may be quoted for effect; John of Gaunt’s major speech from Richard II has been both used to convince consumers as to the Englishness of a certain tea (Typhoo, UK, 1994) and counterposed against images of dropped litter, to urge the use of refuse bins (Central Office of Information, UK, 1983). Likewise Prospero’s pronouncement that ‘We are such stuff as dreams are made on’ has been used to inspire admiration for high-end cars (Alfa Romeo ‘Giulietta’, Europe, 2010) and flat-pack beds (Ikea, worldwide, 2014). Although The Merchant of Venice and Timon of Athens show that Shakespeare held much mercantile practice in low esteem, the epilogue to As You Like It suggests he took a more tolerant view of the advertising, such as it was, of his own day.

Charity Charity, rev. Erin Sullivan

aediles, assistants to the tribunes Brutus and Sicinius, appear in Coriolanus, speaking at 3.1 and 3.3.

Anne Button

Aemilius, a messenger in Titus Andronicus 4.4 and 5.1, presents Lucius as emperor, 5.3.

Anne Button

Aeneas, a Trojan commander in Troilus and Cressida (drawn from *Homer and *Virgil), gives Troilus the news that Cressida must be given to the Greeks, 4.3.

Anne Button

Aeschines, a lord of Tyre, appears with Helicanus, Pericles 3 and 8.

Anne Button

Aeschylus. See critical history; Greek drama.

East Africa.

Bishop Steere’s 1867 translation of *Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare into Swahili is an early instance of the missionary use of Shakespeare in what became in British East Africa common colonial and missionary pedagogic practice. In 1900, the University Missions to Central Africa in Zanzibar produced Hadithi Ingereza, a prose *translation into Swahili of versions of several plays. Kenya’s premier secondary school, Alliance High School, founded by a coalition of missionary groups in 1926, not only taught but put on annual productions of Shakespeare. Ngugi wa Thiong’o writes that, as a pupil at the school, between 1955 and 1958 he saw As You Like It, 1 Henry IV, King Lear, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The presence of Shakespeare within education was strengthened during the 1950s when Makerere University College in Uganda, for a long time the only university college in East and Central Africa, developed its links with the University of London. Alan Warner in his Makerere Inaugural Lecture ‘Shakespeare in the Tropics’ (1954) argued that the study of English literature would make Africans ‘citizens of the world’ but his compatriot David Cook, also at Makerere, contributed to the study of local literatures as well as to Shakespeare. Productions of Shakespeare included one of Macbeth, directed by an American with the first all-black cast in the Ugandan national theatre in 1964. Milton Obote is said, as a student, to have played Caesar in Julius Caesar. During the colonial period expatriate colonials organized performances for regular East African Shakespeare festivals.

During and since the period leading to independence for African states, some writers have continued to promote the presence and use of Shakespeare within cultural and educative practice. Ali Mazrui, head of the Department of Political Science at Makerere, wrote in 1967 of Shakespeare’s importance to African culture as ‘master of the English Language’ and ‘great creator of human characters and eternal situations’, also recommending Hamlet as good training for self-government. The first Swahili translations of complete Shakespeare plays are by Julius K. Nyere, as well the first president of Tanzania. In the 1960s he translated Julius Caesar and then The Merchant of Venice, the latter as Mabepari wa Venisi which means literally ‘the capitalists of Venice’. This version, unlike his earlier translation, is said to reflect more directly his socialist position and is an instance of the attempt by some African writers to appropriate Shakespeare in the context of immediate political struggle. Nyere’s translations were published by OUP in Kenya while, in 1968, S. S. Mushi’s translation of Macbeth was published by Tanzania Publishing House. Shakespeare has been appropriated to argue more explicitly the problematics of colonialism and neo-colonialism in a series of works, notably by Ngugi in his novel A Grain of Wheat (1968), by Murray Carlin, whose appropriation of Othello in Not now, Sweet Desdemona was first produced at the National Theatre of Uganda, Kampala, in 1968, and, further north, by the Sudanese author Tayib Salih who narrates the experiences of a contemporary North African version of Othello in Season of Migration to the North (1969).

Shakespeare has also been received in other ways in various countries in Central and East Africa as a problematic and complex phenomenon. In 1948 Octav Mannoni, using Prospero and Caliban as prototypes, evolved an inferiority-dependence theory of colonialism based on his experience of the Madagascan uprising of 1947–8, ideas later to be developed by Philip Mason, a colonial official who had worked in Africa. These ideas were strongly criticized by Franz Fanon and Aimé *Césaire, famous opponents of colonialism. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who criticized in 1981 the way in which Shakespeare, ‘who had the sharpest and most penetrating observations on the European bourgeois culture’, was taught to him in Kenya and Makerere as if ‘the only concern was with the universal themes of love, fear, birth and death’, and who, even more recently, in 1993 uses the Prospero–Caliban relationship to argue against what he sees as the neo-colonial hegemony of English, traces the beginnings of the rejection of Shakespeare and a move to the Africanization of education to the 1950s. In 1971 Wanjandey Songa was still calling for Africanization, arguing that Shakespeare was being promoted at Makerere and elsewhere at the expense of local cultures. After 1985 Shakespeare was in fact dropped from the Kenyan secondary school syllabus, but, as a result of the intervention of President Danial arap Moi, who in a public address on 25 July 1989 paid tribute to the ‘universal genius’ of Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet was restored as a set text for the 1992 national examination.

At the end of the 20th century, while Shakespeare still features in secondary education in East African countries, there is little or no evidence of any current research at tertiary level or in the field of Shakespeare studies in general. Although, as late as 1996, F. Abiola Irene wrote in Research in African Literatures that ‘Shakespeare’s privileged position in African letters has been ensured essentially through the commanding force of his unique genius’, dearth of evidence of recent new publications or performances in East African countries suggests that Shakespeare’s influence, although still present, may be on the wane.

Southern Africa.

The history of Shakespeare in Southern Africa provides an object lesson for the argument that Shakespeare is always a political matter. As elsewhere, Shakespeare was introduced by missionaries and colonists and remained consistently important to settler communities, particularly those of British extraction. Nathaniel James Merriman, in a series of lectures delivered at Grahamstown halfway through the 19th century, recommended Shakespeare as exemplar of ‘mankind’, a sentiment echoed by the last prime minister of the Cape, John X. Merriman, in 1916 at the celebrations on the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s death. Lovedale Seminary, founded by the Glasgow Missionary Society in 1841, was in the 1920s teaching plays such as The Merchant of Venice, Macbeth, Julius Caesar, and The Tempest. Both during the segregation and apartheid periods and after, Shakespeare has featured in secondary and tertiary education. The kind of Shakespeare taught for much of the 20th century has been strongly influenced by the teachings of Matthew *Arnold, the work of A. C. *Bradley, versions of *New Criticism, and the Scrutiny critics. As the inevitability of the demise of apartheid became clear the Shakespeare’s Schools Text Project, created by the chairman’s fund of Anglo-American Corporation in 1987, declared its intention, in a transitional and post-apartheid society, of promoting the survival of the teaching of Shakespeare at all South African secondary schools. Contributions to Shakespeare scholarship in the first half of the 20th century include F. C. Kolbe’s Shakespeare’s Way: A Psychological Study (1930), a study of key motifs in the texts. Geoffrey Durrant, Christina van Heyningen, Colin Gardner, and Derek Marsh (who emigrated to Australia) applied traditional South African approaches during the 1950s and beyond. By contrast, Wulf Sachs’s Black Hamlet (1937) offers in some respects a more adventurous approach. Sachs, a training psychoanalyst from Lithuania, attempts, in a discussion of the life of John Chavafambira, to explore the intersections between psychoanalysis, Hamlet as version of the universal condition, and the colonial/racial situation.

Performance of Shakespeare was also supported by settler communities in the 19th century. Early recorded productions of Shakespeare in Southern Africa include a performance of Hamlet by soldiers of the garrison at Port Elizabeth in 1799. In 1829 the first civilian theatre company was formed in Cape Town to provide, over the years, a number of Shakespeare productions for the homesick colonial populace. Othello was a much performed play during the 19th century—in what appear to be uniformly racist interpretations—whilst by contrast segregationist and apartheid South Africa in the 20th century avoided it. During the 20th century, productions of Shakespeare, whether in white schools, universities, or by local professional companies, have been mostly tied to current matriculation set plays; a more recent performance of Julius Caesar with black actors and a black director hardly challenged a long tradition of uninspired productions for captive audiences, providing profits for theatre practitioners but no new admirers for Shakespeare. Against this trend, Welcome Msomi’s Zulu appropriation of Macbeth, called Umabatha, first performed in the early 1970s and subsequently abroad including a run at London’s Aldwych theatre and more recently at the *Globe, engaged in part with an evocation of Zulu nationalism, although the conditions of its production and marketing have been criticized. Janet *Suzman’s Market Theatre production of Othello with John Kani in the title role during the late 1980s was a much-fêted attack upon racist and misogynist phobias, especially around interracial love.

In 1904 Beerbohm *Tree’s production of The Tempest elicited a response from W. T. Stead, reading it in the context of King Lobengula and the Matebele uprising. Despite the use of Shakespeare within colonial, segregationist, and apartheid institutions, Shakespeare in the 20th century attracted the interest of an impressive list of black writers, politicians, activists, and thinkers in ways that evidence varying degrees of affiliation, appropriation, or active resistance. His plays have been frequently translated, most famously by Solomon T. Plaatje, who translated six plays into Sechuana only two of which, his version of The Comedy of Errors, Diphoshoso-Phoso (1930), and Julius Caesar (1937), survive. Other plays have also been translated into Sechuana, Xhosa, and Afrikaans. Plaatje, who contributed to Israel *Gollancz’s tercentenary collection A Book of Homage to Shakespeare, is also author of Native Life in South Africa, which offered a powerful argument against the anti-black land policies of the government of his day, as well as a founder member of what was to become the African National Congress. Recently his translations of Shakespeare have been viewed as appropriations designed to empower Sechuana culture rather than to promote Shakespeare. Z. K. Matthews, who wrote Freedom for my People, records the positive impact upon him of the study of Shakespeare at school in 1915–16. In the 1950s, Lewis Nkosi notes that knowledge of Shakespeare became for black students, as well as a status symbol, a means of affiliation with the erstwhile colonial centre—then perceived as more enlightened than apartheid South Africa. Ndabaningi Sithole of Zimbabwe in 1959 argued that a knowledge of Shakespeare contributed to African Nationalism. Others who have drawn on Shakespeare include Can Themba, Es’kia Mphahlele, Peter Abrahams, Bloke Modisane, the assassinated head of the South African Communist Party Chris Hani, and the former South African president Thabo Mbeki.

Since 1980 debate over the historical and present or future use of Shakespeare has intensified. In 1987 Martin Orkin, prompting an outcry from traditionalist South African Shakespearians, maintained that Shakespeare had been used within cultural and educational institutions in ways that complemented apartheid, and has argued then and on other occasions for appropriation of the text in struggles against reactionary or neo-colonial usages of it. David Johnson, almost a decade later, positions Shakespeare as always part of colonial conspiracy and use of him as always evidence of false consciousness. By contrast, the traditionalists, as apartheid seemed finally to be reaching its nadir, established in the 1980s the Shakespeare Society of Southern Africa, the activities of which remain determinedly Arnoldian and unrepentantly bardolatrous in inclination. More interrogative enquiry occurred at the conference entitled ‘Shakespeare—Postcoloniality—Johannesburg 1996’ which, held in Johannesburg, attracted an unprecedented number of international scholars not only from the West but from Asian, Middle Eastern, Australasian, as well as Southern African countries and which resulted in the appearance of the volume Postcolonial Shakespeares. In the 21st century, constituencies advocating a focus on local literatures argue for the abandonment of Shakespeare, described by some as already ‘dust in the townships’, university courses on Shakespeare dwindle noticeably, and little or no research is being undertaken. On the other hand his work continues to be admired, although mainly by South Africans of European descent. It is still performed on stage fairly regularly although, as earlier, mostly in tandem with current school curricula, where, again, its presence so far has been maintained.

West Africa.

Shakespeare is said to have first reached African waters on board a ship, anchored off Sierra Leone in 1607, where performances of Hamlet and Richard II were given, see *Keeling. As was the case in *East Africa, missionary and colonial activity from the 19th century on ensured the presence of Shakespeare in various educational and cultural practices. The Church Missionary Society established the Grammar School for Boys in Freetown, Sierre Leone, in 1849; Lemuel Johnson, who attended the school in the 20th century, recalls studying Macbeth, The Merchant of Venice, Julius Caesar, 1 Henry IV, Henry V, and King Lear. Dependence on Cambridge University School and Higher School Certificate requirements during the colonial period and beyond ensured the continuing influence of Shakespeare. E. T. Johnson translated Julius Caesar into Yoruba in the 1930s and G. E. Hood of Achimota College, Accra, records performances at his school of Twelfth Night in the 1930s. Performances of Shakespeare in West Africa include a screen adaptation of Hamlet, shot in Ghana and shown at a Commonwealth Arts Festival, and, during the colonial period, visits by performers of Shakespeare arranged by the British Council. In 1954 Molly Mahood delivered her Inaugural Lecture at the University of Ibadan. Both she and Eldred Jones (Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone) have made significant contributions to Shakespeare studies, Jones contributing as well to the study of local literatures. Michael Echeruo (Nigeria) and Lemuel Johnson (Sierra Leone), who have also worked on Shakespeare, now work in the United States.

In an essay that has since become a ‘classic’ of cultural anthropology, Laura Bohannan gives an account of her attempt to impart Hamlet to the Tiv; the essay provides an example of the misrecognitions that may occur for all the participants in any cultural encounter or clash. However, in comparison with East, Central, and *Southern Africa, the reception of Shakespeare in West African countries appears markedly less interrogative of the problematics of a colonial Shakespeare. Hints of potentially complex views of the Shakespeare text are to be found in Ben Okri’s response in 1987 in the journal West Africa to an RSC production of Othello with Ben *Kingsley in the title role as well as in Lemuel Johnson’s recent work and in his appropriation in the 1970s of the figure of Caliban, relocated in Freetown and presented as victim of neocolonialism. Even so, as late as the early 1990s Shakespeare was still a compulsory text at secondary level in Sierra Leone, prompting Handel Kashope Wright to wonder, rather belatedly in comparison with the debate in other parts of Africa, why this continues at the expense of local literatures.

As in other parts of Africa, the reception of Shakespeare has involved politicians and cultural activists as well as writers. James Kwegyir Aggrey, who left the Gold Coast for the United States, cited Shakespeare as an important influence; a pamphlet in 1952 salutes Kwame Nkrumah by means of Shakespeare allusion; and in 1960 Nigeria’s Chief Awolowo insisted that ‘some of the mighty lines of Shakespeare must have influenced my outlook on life’. The specific influence of Shakespeare on a number of West African writers has also been remarked upon. Wole *Soyinka read English under George Wilson *Knight and the influence of Shakespeare on his work has been noted, especially that of A Midsummer Night’s Dream as well as of Macbeth on A Dance in the Forests. Soyinka himself has noted that between 1899 and 1950 some sixteen plays of Shakespeare had been translated or adapted by *Arab poets and dramatists. The Nigerian playwright John Pepper Clark argues for the example of Shakespeare as model, taking up the instance of Caliban to advocate a variety of registers within African writing. Shakespeare’s influence has been detected too in the work of other Nigerians including the Onitsha Market Pamphleteers.

Martin Orkin

Agamemnon, leader of the Greek army (based on the character in *Homer’s Iliad) presides over meetings of his commanders in Troilus and Cressida.

Anne Button

Agrippa, friend to Caesar in Antony and Cleopatra, suggests Antony should marry Octavia and hears Enobarbus’ description of Cleopatra, 2.2.

Anne Button

Aguecheek, Sir Andrew, Sir Toby Belch’s drinking companion in Twelfth Night.

Anne Button

Ajax, a Greek commander (based on the character in *Homer’s Iliad), fights Hector, Troilus and Cressida 4.7. When the fight is abandoned, he invites Hector to dine at the Greek camp.

Anne Button

Alarbus, Tamora’s eldest son in Titus Andronicus, is sacrificed to avenge the deaths of Titus’ sons, 1.1.

Anne Button

alarums, a battle call or signal, usually for *drum(s), but exceptionally for *trumpet; it occurs more than 80 times in stage directions and texts of Shakespeare’s plays.

Jeremy Barlow

Albany, Duke of. Husband of Goneril in King Lear, he moves from unease with Goneril, Regan, and Cornwall to defiance.

Anne Button

Albret, Charles d’. See Constable of France.

alchemy. See Scot, Reginald.

Alcibiades, exiled and disaffected, leads an army against his native Athens in Timon of Athens.

Anne Button

Aldridge, Ira (1807–67), African-American actor who, following the closure of the African Theatre in New York where he had played Romeo, moved to England where he appeared as Othello at the Royal Coburg in 1825. Though he added Lear, Macbeth, Richard III, and Aaron (in a drastically adapted version of Titus Andronicus) to his repertoire, it was with Othello that he was most closely identified in a career which was spent touring all over Europe. When he made his overdue West End debut at the Lyceum in 1858, Aldridge was praised for the originality of his interpretation in which Othello’s softer elements were to the fore. Lolita Chakrabarti dramatized Aldridge’s story in the play Red Velvet (2012), starring her husband Adrian *Lester. Lester went on to play Othello at the Royal National Theatre the following year.

Richard Foulkes, rev. Erin Sullivan

Alençon, Duke of. He gives militant advice to Charles the Dauphin, 1 Henry VI 5.2 and 5.7.

Anne Button

Alexander, servant to Cressida in Troilus and Cressida, describes Hector and Ajax to her, 1.2.

Anne Button

‘Alexander’. See Nathaniel, Sir.

Alexander, Peter (1894–1969), Scottish editor, biographer, and textual and literary critic. His Shakespeare’s Henry VI and Richard III (1929) argues that the First Part of the Contention and The True Tragedy of Richard III (both 1594) are not independent source plays but pirated ‘bad’ quartos of the second and third parts of Shakespeare’s Henry VI. This radical revision of the early canon is reflected in Alexander’s later Shakespeare’s Life and Art (1939), A Shakespeare Primer (1951), and Shakespeare (1964). His one-volume modernized edition of The Complete Works (1951) was adopted as a standard text by the BBC and many academic institutions.

Tom Matheson

alexandrine, the twelve-syllable line of classical French verse; or an English six-stress line (hexameter); sometimes found as a variant line in Shakespeare’s dramatic verse, also as the line of *Biron’s sonnet in Love’s Labour’s Lost (4.2.106–19).

Chris Baldick

Alexas is one of Cleopatra’s attendants. His treachery and execution are related in Antony and Cleopatra 4.6.

Anne Button

Algeria. Following independence, theatrical activity in Algeria experienced a great development within the *Arab world. During the years of 1963–87, prestigious directors and playwrights such as Kateb Yacine (1929–89), Rachid Ksentini (1887–1944), and Mahieddine Bachetarzi (1899–1986) contributed to this flourishing. Most of the works were either about the Algerian national liberation war, or were famous masterpieces by socialist playwrights such as Maxim Gorki, *Bertolt Brecht, or Nikolai Gogol. In the 1960s a localized adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew was written by M. Kasdarli and directed by Allel El Mouhib. The play, written in Algerian Arabic, was performed by the newly created (1963) Algerian National Theatre Company and Agoumi Sid Ahmed and Abdelkader Alloula (1929–94), two great figures of the Algerian theatre, were in the cast. Unfortunately this period of glory was short lived. For more than a decade Algeria suffered an undeclared civil war in which several playwrights and artists were brutally murdered, including Alloula, Azzedine Medjoubi, and Tahar Djaout. Consequently several theatres were closed and performances came to a standstill. It is only since the turn of the 21st century that theatrical life has started to regain momentum. In 2004, during the Experimental Theatre Festival in Cairo, the Constantine National Theatre group successfully presented Word and Al-Bandir, written and produced by Al-Taybe, where three famous characters, Antara Ibn Chaddad, Al-Hallag, and Othello, are striving to destroy modern myths. The Professional Theatre Festival opened anew in 2006 with Twelfth Night. Adapted and produced by Ahmed Khoudi with the ISMA Group, the play was in Algerian Arabic and presented without scenery. In 2007 in Mostaganem a young director, Kamel Attouche, staged Ophelia’s Cry, an adaptation based on the Iraqi Khazaal El *Majidi’s translation. The play won three prizes in the *Moroccan Agadir Academic Theatre Festival the same year. In 2014 during the National Feminine Theatre Festival in Annaba, Meriem Allak presented a much-discussed work entitled Shakespeare’s Return. The work, which has no specific relation with the English Bard, is a sharp criticism against the prevailing conditions of the Algerian theatres today. The same year, Djamel Guermi directed a faithful rendering of Macbeth in Skikda.

Rafik Darragi

Alice, Catherine’s gentlewoman in Henry V, teaches her English, 3.4, and interprets for King Harry and Catherine, 5.2.

Anne Button

Allam, Roger (b. 1953), British actor of fine voice and presence. He joined the *Royal Shakespeare Company in 1981; his roles for them include Mercutio (1984), Theseus doubling Oberon (1984), Brutus, Duke Vincentio, and Toby Belch (1987), and Benedick (1990). He played Ulysses at the *National Theatre in 1999, and scored a great success as Falstaff at *Shakespeare’s Globe in 2010 and Prospero in 2013.

Michael Dobson

Allde, Edward. See printing and publishing.

Allen, Giles (d. 1608), owner of the site upon which the Theatre was built. On 13 April 1576 Allen leased a plot of land in Shoreditch to James Burbage who, with his brother-in-law John Brayne, built the Theatre on it. Allen and the Burbages failed to reach agreement on renewal of the lease in 1597, and December/January 1598–9 the Burbages removed their playhouse to re-erect it as the Bankside Globe. Allen’s ensuing legal battles with the Burbages provide much of our knowledge about the Theatre and the Globe.

Gabriel Egan

Alleyn, Edward (1566–1626), actor (Worcester’s Men 1583, Admiral’s/Prince Henry’s 1589–97 and 1600–6) and housekeeper. The 17-year-old Alleyn was named as one of Worcester’s Men in a licence of 14 January 1583 and he was already a renowned actor when, on 22 October 1592, he married Joan Woodward, the stepdaughter of Philip Henslowe, at whose Rose playhouse he had led Lord Strange’s Men from February to June that year. We know of Alleyn’s personal life through charming letters which passed between him and Joan while he led Lord Strange’s Men on tour in 1593, and we hear of his ever-rising professional fame through glowing reports by Thomas Nashe, amongst others. Contemporary allusions suggest that Alleyn was an unusually large man—which undoubtedly helped his celebrated presentation of Marlowe’s anti-hero Tamburlaine—and a surviving portrait and signet ring confirm that he was about 6 feet (2 m) tall, well above the period’s average. To augment his bulk Alleyn apparently developed a powerful style of large gestures and loud speaking which others mocked as ‘stalking’ or ‘strutting’ and ‘roaring’. Alleyn took the lead roles in Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta and Doctor Faustus, Greene’s Orlando furioso, and also Sebastian in the anonymous Frederick and Basilea, Muly Mahamet in Peele’s The Battle of Alcazar, and Tamar Cam in the anonymous 1 Tamar Cam. After three more years at the Rose (1594–7) Alleyn retired but he returned to the stage when Henslowe’s Fortune opened in 1600 and continued until some time before 30 April 1606 when the Prince’s Men were issued a patent which lacks his name. In early May 1608 Alleyn performed in an entertainment for James I at Salisbury House on the Strand and received £20. On 13 September 1619 Alleyn founded the College of God’s Gift at Dulwich which received Alleyn’s and Henslowe’s papers, most importantly the latter’s Diary, upon which much of our knowledge of the theatre is based. Joan Alleyn died on 28 June 1623 and on 3 December that year Alleyn married Constance, the eldest daughter of John Donne, the Dean of St Paul’s.

Gabriel Egan

All for Love. See Antony and Cleopatra.

All Is True See centre section.

alliteration, repetition of similar sounds (usually initial consonants) within any sequence of words:

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard

(Sonnet 12)

Alliteration may also link the initial stressed consonant of a word with that of a stressed syllable within a word: ‘Beated and chopp’d with tann’d antiquity’ (Sonnet 62, l. 10); ‘When I did speak of some distressful stroke’ (Othello 1.3.157).

Chris Baldick

All’s Well that Ends Well. See centre section.

allusion, a passing or indirect reference to something (e.g. a written work, a legend, a historical figure) assumed to be understood by the audience or reader, as with the reference to the mythical Phoenix in Sonnet 19.

Chris Baldick

Alonso is the King of Naples in The Tempest. His son Ferdinand and Prospero’s daughter (Miranda) become betrothed, reconciling him to Prospero.

Anne Button

Amateur performance. Appropriately for a body of plays willing to depict forms of recreational performance in comedy, history, or tragedy—from the artisans’ efforts at ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ in A Midsummer Night’s Dream to Falstaff’s ‘play extempore’ in 1 Henry IV to Hamlet’s dilettante attempt at the death of Priam—the Shakespeare canon has been central to the development of amateur drama in the Anglophone world and beyond. A Midsummer Night’s Dream was itself being performed recreationally by apprentices as early as the 1650s (in the form of Robert *Cox’s *droll The Merry Conceited Humours of Bottom the Weaver), but over the ensuing two centuries non-professional productions of Shakespeare belonged more often to a pan-European vogue for aristocratic private theatricals, anticipated in 1623 by Sir Edward *Dering’s domestic performances of a conflation of 1 and 2 Henry IV. By the 19th century, such home theatricals generally preferred to stage only abbreviations or *burlesques of the plays, but at the same time many urban literary societies devoted to artisan-class self-improvement (such as the Manchester Athenaeum) were beginning to diversify into full-scale public theatrical production. In 1902 the first show mounted by the Stockport Garrick Society—a dressy Merchant of Venice at the Stockport Mechanics’ Institute—set an important precedent by which civic amateur dramatic societies sought to meet a demand for the kinds of serious drama which commercial managers regarded as too risky: in this the society was consciously anticipating and seeking to encourage the establishment of the subsidized companies which would take over this task after the Second World War, largely eclipsing their amateur colleagues. The *Royal Shakespeare Company celebrated its long-unacknowledged kinship with amateur Shakespearians with its ‘Open Stages’ project of 2011–12, lending personnel to help train the casts of amateur productions which competed to perform on the company’s stages during the 2012 World Shakespeare Festival.

In addition to its roles within British society, non-professional Shakespeare has also been a recurrent pursuit of military personnel (in situations which have sometimes preserved the single-sex traditions of the Renaissance stage: Ulysses S. Grant, for instance, played Desdemona while a young lieutenant in the 1840s) and among expatriates.

Michael Dobson

ambassadors. (1) French ambassadors bring ‘treasure’ (actually tennis balls) on behalf of the Dauphin to King Harry, Henry V 1.2.245–57. (2) Ambassadors from England announce the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Hamlet 5.2.321–6. (3) Antony uses his schoolmaster (see 3.11.71–2) as an ambassador, Antony and Cleopatra 3.12 and 3.13 (he was first named as Euphronius by *Capell, following Shakespeare’s source *Plutarch).

Anne Button

America. See United States of America; Latin America.

Amiens, one of Duke Senior’s attendants in As You Like It, sings in 2.5 and 2.7.

Anne Button

Amyot, Jacques. See Plutarch.

anachronism, the introduction of anything not belonging to the supposed time of a play’s action: most famously the clock in Julius Caesar (2.1.192). The term may also be applied to modern-dress productions of Shakespearian plays.

Chris Baldick

anacoluthon, a change of grammatical construction in mid-sentence, leaving the initial utterance unfinished:

Today as I came by I callèd there—

But I shall grieve you to report the rest

(Richard II 2.2.94–5)

Chris Baldick

anadiplosis, a rhetorical figure in which clauses, lines, or sentences are linked by repetition of the final word or phrase of the first in the initial word or phrase of the second:

My brain I’ll prove the female to my soul,

My soul the father …

(Richard II 5.5.6–7)

Chris Baldick

anagnorisis (Greek, ‘recognition’), the turning point in a drama at which the protagonist discovers the true state of affairs to which he or she had been blind—as with Othello’s recognition that Desdemona had not betrayed him.

Chris Baldick

anapaest, a metrical unit (‘foot’) comprising two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable, rarely found as the basis of full lines:

With a hey, and a ho, and a hey-nonny-no

(As You Like It 5.3.16)

Chris Baldick

anaphora, repetition of the same word or phrase at the start of successive clauses or lines:

This blessèd plot, this earth, this realm, this

England

(Richard II 2.1.50)

Chris Baldick

anaptyxis, insertion of an extra vowel, usually before a medial r or l and after the word’s principal accent. This occurs sometimes in words like ang-ry, Hen-ry, monst-rous, child-ren, fidd-ler, wrast-ler, and even Eng-land (Hamlet 4.3.46). Cf. Lady Macbeth’s ‘The raven himself is hoarse | That croaks the fatal ent-rance of Duncan | Under my battlements’ (1.5.38–40).

Chris Baldick

Anatomy of Abuses, The. See Stubbes, Philip.

Anderson, Dame Judith (1898–1992), American actress, who arrived in the USA from Australia in 1918. Throughout her career she specialized in operatic, grande dame roles, and came to be regarded as the last of the grand-style tragedy queens. Her Shakespearian roles included Gertrude (in John *Gielgud’s Hamlet in New York, 1936), Hamlet (in which she toured, remarkably, at the age of 71), and—famously and self-definingly—Lady Macbeth, first opposite *Olivier in London in 1937, and later opposite Maurice Evans in New York (1941, and again on film in 1960). Her last role was in an American daytime soap opera called Santa Barbara (1984).

Michael Dobson

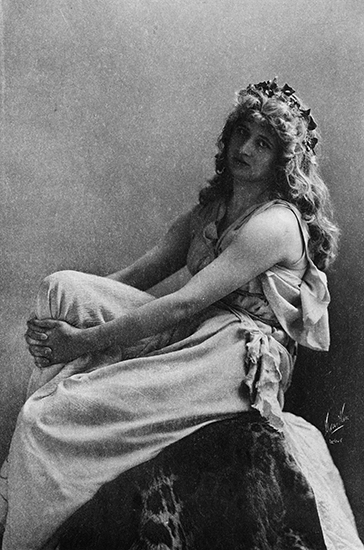

Anderson, Mary (1858–1940), American actress, who made her debut in 1875 at Louisville, aged 16, as Juliet, a role to which her natural gifts of stature, face, and voice were well suited, as they were to Rosalind, Hermione, and Perdita. Within this limited range Mary Anderson adorned the stage on both sides of the Atlantic. Her Romeo and Juliet at the Lyceum (1884), with William Terriss as Romeo and designs by Lewis Wingfield, enhanced her reputation at home as much as in London and she was fêted during her 1885–6 US tour, but later resentment at her European pretensions contributed to her breakdown (1889) and subsequent retirement to Broadway, England, where she wrote several volumes of memoirs.

The American actress Mary Anderson (1859–1940) as Perdita. She was the first to double the roles of Hermione and Perdita in The Winter’s Tale.

Richard Foulkes

‘And let me the cannikin clink’, sung by Iago in Othello 2.3.63; the original tune is unknown.

Jeremy Barlow

Andrewes, Robert, a scrivener who drew up and witnessed the documents for Shakespeare’s purchase of the *Blackfriars Gatehouse in 1613. Another possible though faint Shakespearian connection is his preparing the will of Marie James, mother of the brewer Elias James, whose epitaph Shakespeare may have written.

Stanley Wells

‘And Robin Hood, Scarlet and John’, snatch of a *broadside ballad sung by Silence in 2 Henry IV 5.3.104; also alluded to by Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor 1.1.158. The original tune is unknown.

Jeremy Barlow

Andromache, Hector’s wife in Troilus and Cressida, tries to dissuade him from going into battle, 5.3.

Anne Button

Andronicus, Marcus, a Roman tribune in Titus Andronicus who helps his brother Titus take revenge.

Anne Button

Andronicus, Titus. See Titus Andronicus.

‘And sword and shield | In bloody field’, fragment sung by Pistol in Henry V 3.2.9; the original tune is unknown.

Jeremy Barlow

‘And will a not come again’, sung by Ophelia in Hamlet 4.5.188. A tune with 17th-century origins (a variant of ‘The merry, merry milkmaids’) was apparently sung to the words at Drury Lane in the late 18th century.

Jeremy Barlow

Angelo. (1) A goldsmith in The Comedy of Errors, he has Antipholus of Ephesus arrested, 4.1.

(2) Given absolute power by the resigning Duke Vincentio, he threatens Isabella’s brother with execution if she refuses to have sex with him in Measure for Measure.

Anne Button

Angers, Citizen of. See Citizen of Angers.

Angus, a thane, announces Cawdor’s lost thaneship in Macbeth 1.2.107–14 and marches against Macbeth in Act 5.

Anne Button

animal shows. Baiting of bulls and bears using dogs was already a popular entertainment on Bankside when the first playhouses were constructed. Like open-air playhouses, baiting rings were wooden structures, approximately round, and scholars have conjectured that a travelling players’ booth placed within a baiting ring gave the design for the playhouses. However, baiting rings do not elevate the lowest auditorium gallery—which is essential in a playhouse else the yardlings obscure the view—because the baiting ring yard is necessarily free of spectators. Also, the barriers needed to contain animals make for poor sightlines. Philip Henslowe, joint Master and Keeper of the King’s Bears with Edward Alleyn from 1604, built the first combined playhouse and baiting ring, the Hope, in 1614.

Gabriel Egan

Animated Tales, The. See Shakespeare: The Animated Tales.

Anjou, Margaret of. See Margaret.

Anjou, René, Duke of. See René, Duke of Anjou, King of Naples.

Anne, Lady. She curses Richard and any future wife of his but is wooed and won by him, Richard III 1.2 (based on Anne Neville (1456–85), daughter of Warwick ‘the Kingmaker’).

Anne Button

Anne Hathaway’s Cottage (Hewland) is a timber-framed and thatched building in Shottery, a hamlet within the parish of Stratford-upon-Avon but just over a mile (1.5 km) from the town centre. It is known to have been held by the Hathaway family from at least 1543, as part of copyhold property granted then to John Hathaway. Hewland was the name attached to land belonging to one of two messuages included in this grant, and has come to be taken as the original name for Anne Hathaway’s Cottage itself. John’s holdings subsequently passed to Richard Hathaway, probably his son, whose daughter Anne married William Shakespeare in November 1582. Richard died in September 1581, when his property passed to his widow Joan, probably his second wife. She lived until 1599.

The term ‘cottage’ hardly does justice to the Hathaway family home, which, by the standards of the day, was a substantial residence of a well-to-do yeoman farmer. It appears to have been built in two stages. The lower part, adjoining the road, has been conclusively dated to the 1460s and consisted of a cross-passage, where the visitor enters today, with a hall to the left and kitchen to the right. The hall, when originally built, would probably have been open to the roof. On the first floor, above the cross-passage, is a space of matching size where the early construction of this part of the house is clearly visible. The evidence for this is a cruck, a pair of large and matching curved timbers reaching from the ground to the apex of the roof, a characteristic of medieval timber-framed buildings. On either side are bedchambers, the one to the west created when a floor was inserted into the open hall. The chimney stack, which runs up through this part of the house, probably dates from the time of this alteration: outside, it bears a plaque, with the date 1697 and the initials I. H. (for John Hathaway): this would seem rather late for the alterations to the hall and may simply record repairs or rebuilding of the exterior stonework.

In 1610, Richard’s son and heir Bartholomew Hathaway acquired the freehold of the family’s property and it may have been he who added a taller section to the house at the orchard end. This is now divided into three small rooms on the ground floor, with two bedchambers above. Ownership descended in the male line of the Hathaway family until the death, in 1746, of John Hathaway. It then passed, through his sister Susanna, to his nephew John Hathaway Taylor, whose son William Taylor lived there until his death in 1846. Financial problems had led to the division of the house into two cottages by 1836 and to its sale two years later, but Taylor had remained in occupation as tenant of one half. His daughter Mary, the wife of George Baker, was still living there in 1892 (in one of three cottages into which the house had been further divided), when the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust purchased the property. Mary Baker, who died in 1899, was appointed first custodian. Subsequent changes have primarily affected the building’s setting, notably the redesign of the garden in the 1920s under the supervision of Ellen Ann Wilmot.

The earliest published attribution of the house as the home of Anne Hathaway, together with the first known drawing, is to be found in Samuel Ireland’s Picturesque Views on the Warwickshire Avon of 1795, although it is clear from his account that the tradition was well established, perhaps reaching back to the time of the Shakespeare Jubilee of 1769. Nicholas Rowe had been the first to record a local tradition that Anne’s maiden name was Hathaway, but it was not until the middle of the century that her name had first been linked to the Shottery family of that name. It is worth noting, in this instance, that the discovery, over 50 years later, of the documents recording Shakespeare’s marriage confirmed rather than disproved this tradition.

The substantial farmhouse owned by the Hathaways of Shottery, originally known as ‘Hewland’ but now almost universally famous as Anne Hathaway’s Cottage.

Robert Bearman

Anne of Denmark, Queen of England and Scotland (1574–1619), consort of James I and VI. Independent and literate, she studied Italian with John *Florio, who dedicated both his Montaigne translation and his dictionary to her. For the first decade of the reign, she was the principal patron of the court masque, and *Jonson essentially reinvented the form to her taste. It is probably in deference to her that the references to drunkenness as a Danish national trait in Hamlet 1.4 are omitted from Q2 (1604).

Stephen Orgel

Anne Page. See Page, Anne.

‘An old hare hoar’, sung by Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet 2.3.125; the original tune is unknown.

Jeremy Barlow

Anonymous A film (2011), directed by Roland Emmerich, in which Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, is portrayed as the author of Shakespeare’s works. Shakespeare himself is depicted as an illiterate and drunken buffoon.

Stanley Wells

anonymous publications. The earliest *quarto texts of Shakespeare’s plays—Titus Andronicus (1594), The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI) (1594), Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI) (*octavo, 1595), Romeo and Juliet (1597), Richard II (1597), Richard III (1597)—were printed without naming the dramatist on the *title page. Shakespeare’s name first appeared on the 1598 quarto of Love’s Labour’s Lost, although in the same year 1 Henry IV was published anonymously, as was Henry V in 1600. Later quartos prominently advertised their texts as ‘Written by William Shakespeare’. The dramatist received top billing in the largest type-font on the title page of King Lear (1608), and the publisher of Othello (1622) wrote that ‘the author’s name is sufficient to vent his work’. In recent years two anonymous publications considered part of the Shakespeare *apocrypha, Arden of Faversham (1592) and Edward III (1596), have come increasingly to be viewed as part-authored by Shakespeare.

Eric Rasmussen, rev. Will Sharpe

Antenor, based on the character from *Homer’s Iliad, is exchanged for Cressida in Troilus and Cressida, Act 4.

Anne Button

Anthony, Mark. See Antony and Cleopatra; Julius Caesar.

anticlimax, a deflating descent into banality, usually knowingly—as distinct from inadvertent bathos:

And then he drew a dial from his poke,

And looking on it with lack-lustre eye

Says very wisely, ‘It is ten o’clock.’

(As You Like It 2.7.20–2)

Chris Baldick

Antigonus, husband of Paulina in The Winter’s Tale, is killed by a bear as he attempts to abandon baby Perdita.

Anne Button

Antiochus is King of Antioch. His incest with his daughter is discovered by Pericles, Pericles 1.1.

Anne Button

Antiochus’ Daughter. See Antiochus.

Antipholus of Ephesus, long estranged from his family, is eventually reunited with his parents and twin of the same name (who has come to Ephesus from Syracuse to seek him) in The Comedy of Errors.

Anne Button

Antipholus of Syracuse. See Antipholus of Ephesus.

anti-theatrical polemic. The first important attack on the theatre was Stephen Gosson’s rather mild The School of Abuse (1579), followed by the stronger Plays Confuted in Five Actions (1582). The former was dedicated, without authority, to Philip Sidney, whose Defence of Poetry partly answers it. In January 1583 the bear-baiting stadium at Paris Garden collapsed killing many in the lowest gallery and Puritan preachers hailed this as God’s judgement. Later the same year Philip Stubbes, in his Anatomy of Abuses (1583), complained that ‘the running to Theaters and Curtains, daily and hourly, time and tide, to see plays and interludes’ was bound to ‘insinuate foolery, and renew the remembrance of heathen idolatory’ and to ‘induce whoredom and uncleanness’. Two aspects of playing were subject to criticism in these attacks. The subject matter was likely to incite irreligious sensual pleasure via spectacles of ‘wrath, cruelty, incest, injury [and] murder’ in the tragedies and ‘love, cozenage, flattery, bawdry [and] sly conveyance of whoredom’ in the comedies, as Gosson put it. Furthermore, acting itself was suspect because commoners feigned the actions of monarchs and men the actions of women, which might suggest that God-given social and sexual distinctions were matters merely of conduct rather than being.

In a sermon at Paul’s Cross delivered on 3 November 1577, Thomas White broke off his attack on Sunday pleasures in general to focus on playing: ‘behold the sumptuous Theatre houses, a continual monument of London’s prodigality and folly.’ White welcomed the cessation of playing due to the plague and saw a spiritual as well as a practical causal connection: ‘the cause of plagues is sin, if you look to it well, and the cause of sin are plays; therefore the cause of plagues are plays.’ Puritanism had initially been a movement to expunge remaining elements of Catholicism from the Church of England, but the reform movement fragmented and there was no simple Puritan objection to the stage. John *Milton was a Puritan playgoer and many reformist aristocrats patronized playing companies. Dramatists often represented Puritans as anti-sensual hypocrites (Zeal-of-the-Land Busy in Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair is a fine example) but historians no longer see the court as essentially pro-theatre and the city authorities (dominated by Puritans) as essentially anti-theatre. Rather, the theatre industry was one of the sites upon which was played out the larger political conflict between court and city. The longest anti-theatrical polemic was William Prynne’s Histrio-mastix: The Players’ Scourge of 1633 which specifically laments the folio format, once reserved for Bibles and other high-quality work, being used for play anthologies such as ‘Ben Johnsons, Shackspeers and others’. Prynne was imprisoned and his ears were removed because his condemnation of women acting was taken to be a direct reference to Queen *Henrietta Maria’s participation in a masque, but his book was influential in the suppression of playing in 1642.

Gabriel Egan

antithesis, an effect of contrast produced by framing opposed terms in parallel syntactical constructions: ‘Before, a joy proposed; behind, a dream’ (Sonnet 129).

Chris Baldick

Antium, Citizen of. See Citizen of Antium.

Antoine, Théâtre, founded by the naturalist director André Antoine (1858–1948) in 1897 on a Parisian ‘Boulevard’ and still operating independently. Its innovative electrical fittings allowed for safe, complete darkness on stage and in the auditorium. Antoine staged his first memorable Shakespearian drama, King Lear (1904), in Loti and Vedel’s integral translation.

Isabelle Schwartz-Gastine

Antonio. (1) He is the father of Proteus in The Two Gentlemen of Verona. (2) Having failed to repay a debt to Shylock, he narrowly escapes having to give him a pound of his flesh in The Merchant of Venice. (3) He is Leonato’s brother in Much Ado About Nothing. (4) He lends Sebastian his purse and is dismayed when ‘Cesario’—whom he believes to be Sebastian—disavows him when he is arrested in Twelfth Night. (5) Having usurped his brother Prospero’s dukedom of *Milan many years before the action of the play, he is shipwrecked on Prospero’s island in The Tempest.

Anne Button

Antony, Mark (Marcus Antonius). See Antony and Cleopatra; Julius Caesar.

Antony and Cleopatra See centre section.

Apemantus, ‘a churlish philosopher’ in Timon of Athens, anticipates Timon’s misanthropy with his own, but is reviled by Timon in the woods, 4.3.

Anne Button

apocrypha, a term, borrowed from biblical studies, used to denote works which have at one time or another been attributed to Shakespeare but are not currently regarded as part of the *canon. Pericles, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and the small Shakespearian portion of Sir Thomas More, though excluded from the First Folio, are no longer regarded as apocryphal, but seven plays which the Third Folio (1664), following the example of their Jacobean quartos, did attribute to Shakespeare are no longer considered to be by Shakespeare, namely *Locrine, The *London Prodigal, The *Puritan, *Sir John Oldcastle, *Thomas, Lord Cromwell, and A *Yorkshire Tragedy. Other apocryphal plays attributed to Shakespeare by 17th-century printers or booksellers are The *Troublesome Reign of King John, The *Birth of Merlin, *Arden of Faversham, *Fair Em, and *Mucedorus. The apocrypha also include some plays never attributed to Shakespeare in his own time at all, but claimed as his by modern scholars on internal evidence alone. These include Edmund Ironside, and the apocryphal play with the strongest claim to be considered genuine, *Edward III, which has come to be considered as securely part-Shakespearian as Sir Thomas More by many scholars, albeit the latter identification rests on palaeographic as well as stylistic evidence. Strong and convincing claims have likewise been made for parts of Arden of Faversham, the 1602 revised text of *Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy, and *Double Falsehood as genuine additions to the Shakespeare canon in recent years, though the circumstances of Shakespeare’s input in each seem to vary greatly, and can by no means straightforwardly be reconstructed or explained. *Mucedorus is also beginning to attract fresh critical attention as a Shakespearian maybe.

Michael Dobson, rev. Will Sharpe

Apology for Actors, An. See Heywood, Thomas.

aporia, a rhetorical figure in which the speaker hesitates between alternatives. Hamlet’s ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy is the most celebrated extended example.

Chris Baldick

Apothecary He sells poison to Romeo, Romeo and Juliet 5.1.

Anne Button

apparitions, three. In turn they tell Macbeth to ‘beware Macduff’, that ‘none of woman born’ shall harm him, and that he ‘shall never vanquished be’ until Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane, Macbeth 4.1.

Anne Button

apprentices. See boy actors.

appropriation, the more aggressive cousin of *adaptation. Although there is no absolute distinction between these two categories of creative intervention, appropriation literally means ‘to make one’s own’, and appropriations of Shakespeare are often taken to be those re-envisionings that dramatically and sometimes almost unrecognizably rework elements of character, genre, narrative, and especially ideology in their source texts. Some poststructural and postcolonial appropriations of Shakespeare have sought to draw attention to and deconstruct the plays’ canonical authority, wresting from them their status as tools of empire and giving voice to alternative perspectives in the process. Less political appropriations may use Shakespeare as a form of intertext or allusive echo, creating new stories that eschew direct comparison with their Shakespearian predecessors.

Erin Sullivan

apron stage, the technical name for the part of the modern stage projecting in front of the curtain, but used anachronistically to refer to the entire stage of Shakespeare’s time which projected into the audience (seated at the indoor theatres and standing at the open-air theatres) who thus surrounded it on three sides. Also known as the thrust stage and to be contrasted with the proscenium arch stage.

Gabriel Egan

Apuleius, Lucius (b. c.ad 123), Roman writer and rhetorician, educated at Carthage and Athens, who travelled in the East before returning to Africa to marry a rich widow. The Golden Ass, translated into English by William Adlington in 1566, with reprints in 1571, 1582, and 1596, is the only surviving Latin novel. Recycling Greek and Roman narratives, including the Ovidian tale of Midas’ transformation into an ass, it tells how one Lucius, in this asinine shape, attracts the attention of a powerful woman, but is finally restored to human form by Isis. This precursor of A Midsummer Night’s Dream may also have influenced Venus and Adonis, Macbeth, and Cymbeline.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

Arab world. The first translator of Shakespeare in the Arab world was the Egyptian writer Najib El Haddad (1867–99) and the first Shakespearian play ever performed in *Egypt was Othello (produced by Suleimen Effendi Kerdahy in November 1887).

Several prestigious Arab poets and writers felt the need to translate or adapt Shakespeare such as Tanyus Abduh (Hamlet, 1902), Khalil Mutran (Othello, 1912, Macbeth, Hamlet, and The Merchant of Venice), Muhammad Hamdi (Julius Caesar, 1912), Sami Al-Juraidini (Julius Caesar, 1912), Muhammad Lutfi Jumʿa (Hamlet), Muhammad Al-Sibaʿi (Coriolanus), Mahmood Ahmed Al-ʿAqqad (Julius Caesar), Muhammad Awad Ibraheem (Antony and Cleopatra, As You Like It), Jabra Ibraheem Jabra (most of Shakespeare’s works, including the Sonnets), Ali Al-Raʿi, Muhammad Teymour, Mahmood Teymour, Iz Al-Deen Ismaʿil, Lewis Awad, Abdel Oadir Al-Out, etc.

Because they had to comply with the prevailing taste of the public, the early translators did not hesitate to change the titles of some plays and even to give Arabic names to popular dramatis personae: Utail or AttaʿUllah for Othello, Ghalban for Caliban, Yaʿqub for lago, etc. Given the operatic trend in that period, not a single play, including Hamlet, was ever performed without songs. The Egyptian actor and producer Cheik Salama El Higazy, whose company had staged successfully a musical comedy with a happy ending adapted from Romeo and Juliet under the title The Martyrs of Love in 1906, gave up the songs when he produced Hamlet the following year, but the public was so much disappointed that he thought fit to ask his friend, the great poet Ahmed Shawky, for some songs. The success of the Shakespearian play, in which the hero does not die on stage, lasted until 1914.

Hamlet inspired many Arab playwrights such as Alfred Farag (Sulaiman Al-Halabv and Ali Janah Al-Tabrizi Wa-Tabia Ghufa), Salah Abdul Sabour (Leila and Majnoun), and Mamdouh Adwan (Hamlet Yastaghs Mutaakhar). Great actors including Youssef Wahby, Abdelaziz Khalil, Aly El Kassar, and George Abyadh staged it not only in Egypt but also in many Arab countries. It was Suleimen Effendi Kerdahy who performed Hamlet for the first time in 1909 in Tunis, along with Othello and Romeo and Juliet, before he died a few weeks later. In *Algeria, Hamlet was played by the great actor Muhiʿl-Din in 1953.

Most of the translators used literary Arabic prose; however, there were a few attempts at verse translations by Muhammad Iffat (Macbeth, 1911, The Tempest, 1909), but without much success. Other translators, like Ahmed Zaky Abu Shady (The Tempest, 1930), Muhammad Ferid Abu Hadid (Macbeth, 1934), and Aly Ahmad Bakathir (Romeo and Juliet, 1936), adopted the Shakespearian blank verse.

Aziz Abadah’s Qaysar is almost a faithful adaptation of Julius Caesar. Though inspired by Garnier’s work, Shawky’s Masr’a Cleopatra (The Death of Cleopatra, 1929) evokes the Shakespearian play in so far as the two heroines experience through death the same catharsis, heralding the same message of love and freedom. More recent works are Saad Al-Khadim’s Dr Othello and Abdul Karim Barsheed’s Othello Wal-Kail Wal-Baroud (1965).

Shakespeare’s Sonnets and poems, known to the Arab world through F. T. Palgrave’s popular anthology, The Golden Treasury of the Best Songs and Lyrical Poems in the English Language (1861), influenced several Arab poets, such as Abderrahman Chokry, Al Aqqad (Egypt), Abul Kacem Echebbi (*Tunisia), and Nazek Al-Malayika (*Iraq).