Julius Caesar

Shakespeare’s most classical tragedy, as well as one of his most polished, was seen by a Swiss visitor, Thomas *Platter, on 21 September 1599: since Julius Caesar is not mentioned among Shakespeare’s works by *Meres the previous year, draws incidentally on two works published in 1599 (Samuel Daniel’s Musophilus and Sir John Davies’s Nosce teipsum), and is itself alluded to in a third (Ben Jonson’s Every Man in his Humour), this is likely to have been an early performance. In vocabulary the play has links with Shakespeare’s next tragedy, Hamlet, while in metre it is closest to Henry V and As You Like It: it was probably composed between the two latter plays, during 1599.

Text: The play’s only authoritative text is that provided by the First Folio (1623), for the most part an unusually good one, apparently prepared from a promptbook. It may record some alterations to the play made long after its première: 2.2 and 3.1, for example, seem to have been modified to allow an actor to double the roles of Cassius and Ligarius, while a line of Caesar’s ridiculed as self-contradictory by Ben *Jonson in his prologue to The Staple of News (1625) and again in Discoveries (c.1630), ‘Know Caesar doth not wrong but with just cause’ (3.1.47), appears in the Folio with the offending last four words removed.

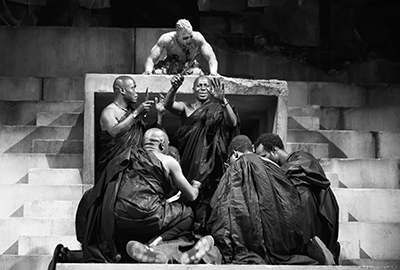

‘Stoop, then, and wash’. Cyril Nri’s Cassius proclaims tyranny dead, watched over by Brutus (Paterson Joseph) and the Soothsayer (Theo Ogundipe) in Gregory Doran’s 2012 African-set production.

Sources: This was Shakespeare’s first play to use *Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans: it closely follows the relevant sections of Plutarch’s biographies of Caesar, Brutus, and Antony, although Shakespeare compresses and transposes events at will. The Lupercal and the Ides of March, for example, which in the play seem to be successive days, are actually a month apart (see Calendar, Shakespeare’s), while the battle of Philippi was actually two battles, the deaths of Cassius and Brutus separated by 20 days rather than the few hours which seem to intervene in the play. Plutarch, however, supplies only the barest summaries of the speeches made at Caesar’s funeral by Brutus and Antony, the latter of which becomes the turning point of Shakespeare’s play, as well as one of the most frequently quoted passages in the entire canon. Although here he adds material to Plutarch, in one crucial respect Shakespeare removes some: the play suppresses the detail that Brutus was suspected by many of being Caesar’s illegitimate son (and that his ‘unkindest cut’ was delivered to Caesar’s groin), exonerating him from parricide.

Synopsis: 1.1 The tribunes Flavius and Murellus rebuke a group of commoners for celebrating Caesar’s victory over Pompey in the civil wars.

1.2 At the festival of the Lupercal, Caesar reminds Antony to touch his wife Calpurnia while running the ceremonial race in the hopes of curing her infertility. A soothsayer urges him to beware the Ides of March, but is dismissed as a dreamer. Left together when Caesar’s party leave for the race, Brutus and Cassius discuss Caesar’s increasing power, anxious, when they hear an offstage shout, that he may be proclaimed king: Cassius, working on Brutus, reminds him of his republican ancestor Lucius Junius Brutus. When Caesar returns with his followers he is angry, and asks Antony in private about the malcontented-looking Cassius: after their departure the sardonic Casca tells Cassius and Brutus how Antony offered Caesar a crown three times but he refused it, to the applause of the watching crowd, and that Murellus and Flavius have been condemned to death for removing festive decorations from images of Caesar. Brutus agrees to discuss the political situation further with Cassius, who resolves, in soliloquy, to have anonymous letters delivered to Brutus encouraging him to take an active part in a conspiracy against Caesar.

1.3 At night Casca speaks in terror of the prodigies he has seen, first to Cicero and then to Cassius, who welcomes them as omens commenting on Caesar’s ambition and admits Casca to the conspiracy. Cassius sends Cinna to deliver further anonymous messages to Brutus before he and Casca go to Brutus’ house to continue persuading him to join them.

2.1 In his orchard Brutus decides Caesar must be prevented from becoming a tyrant by assassination, a decision in which he is confirmed by reading the anonymous letters. His servant Lucius confirms that tomorrow is the Ides of March. Cassius, Casca, and other conspirators arrive, their faces hidden, and after a private discussion with Cassius, Brutus shakes their hands (declining to take a formal oath), ratifying their plan to kill Caesar the following day. Brutus overrules Cassius’ suggestion that Caesar’s close friend Antony should be killed too. Decius promises to flatter Caesar to ensure that he comes to the Capitol, where they will stab him. After the conspirators depart, Brutus’ wife Portia implores him to tell her what has been on his mind, finally showing that she has wounded her own thigh to prove her stoicism: Brutus promises he will, but first admits the sickly Caius Ligarius, who is eager to join the conspiracy.

2.2 Caesar, alarmed by the omens, orders that augurers sacrifice an animal, which proves to have no heart. Calpurnia, who has dreamed of his murder, begs Caesar not to go to the Capitol, and he eventually agrees. Decius arrives, however, and persuades Caesar to change his mind, assuring him that the Senate means to crown him. Brutus and the conspirators, and Antony, arrive to accompany him to the Capitol.

2.3 Artemidorus has a letter for Caesar warning him against the conspirators.

2.4 Portia is desperately anxious for news from the Capitol.

3.1 Caesar and his party are met by the Soothsayer, who points out that the Ides of March are not yet over, and by Artemidorus, whose letter Caesar sets aside unread on the grounds that it concerns him personally. Cassius is worried that the conspiracy is about to be discovered, but Trebonius leads Antony out of the way as planned, and Metellus Cimber petitions Caesar for the repeal of his banished brother. The other conspirators kneel in his support, but Caesar insists that he is above being swayed from his purposes. Casca stabs him, followed by all the conspirators, lastly Brutus, and Caesar dies. The other senators and citizens flee: the conspirators wash their hands in Caesar’s blood, planning to proclaim their act and its libertarian motives in the Forum. Antony arrives, and after asking whether they wish to kill him too, willing to die alongside Caesar, he shakes their hands, looking forward to hearing their reasons for the murder. Brutus, against Cassius’ advice, permits Antony to speak at Caesar’s funeral. Left alone with Caesar’s body, Antony vows revenge. He tells the servant of Caesar’s nephew Octavius that he means to see what his oratory can do to win over the people, after which he will discuss the future with Octavius.

3.2 Brutus ascends the pulpit before the plebeians and assures them, in prose, that though he loved Caesar he had to kill him to preserve their country’s liberty: they hail him as a hero, but at his insistence they remain after his departure to hear Antony. Antony, praising the conspirators with an irony that becomes increasingly obvious, reminds the people of Caesar’s virtues, shows a document he claims is his will, and, coming down from the pulpit, shows them Caesar’s corpse and its wounds, inflaming them against the conspirators. Feigning unwillingness, he finally reads Caesar’s will, in which according to Antony each Roman is left money and Caesar’s private gardens will become public parks, upon which the crowd disperses to attack the conspirators. Hearing that Brutus and Cassius have fled the city, while Octavius and Lepidus are both at Caesar’s house, he goes to join the latter.

3.3 Rioting citizens kill a poet called Cinna even though he insists that he is not the Cinna who was among the conspirators, before departing to burn the conspirators’ houses.

4.1 Antony, Octavius, and Lepidus negotiate a proscription list, which includes Lepidus’ brother and Antony’s nephew. After Lepidus’ departure Antony argues that he is not fit to share the government of Rome with them, but Octavius disagrees. They set about mustering allies and troops to meet those being raised by Brutus and Cassius.

4.2 At a private conference, Brutus accuses Cassius of betraying the conspiracy’s ideals by accepting bribes: eventually they make up their quarrel, Brutus explaining his temper by revealing that he has just learned that Portia, distracted with anxiety, has killed herself. Their lieutenants Titinius and Messala are admitted to discuss strategy: Messala reports Portia’s death, of which Brutus feigns a stoical acceptance. Brutus overrules Cassius, insisting that they should march immediately to Philippi to fight Antony and Octavius. After his colleagues’ departure, when his staff have gone to sleep, Brutus is visited by Caesar’s ghost, which promises to meet him at Philippi.

5.1 Antony and Octavius quarrel as to which shall lead the right flank of their attack before defying Cassius and Brutus to immediate battle at a parley. Cassius and Brutus part, resolved to kill themselves if defeated.

5.2–3 Brutus’ forces assault those of Octavius, but leave Cassius’ army at the mercy of Antony: Cassius sends Titinius to report from his camp. Seeing Titinius surrounded by cavalry, Cassius’ servant Pindarus reports that all is lost, and Cassius has himself killed by him. The cavalry, however, were those of Brutus’ army: finding Cassius’ body, Titinius kills himself. Brutus, young Cato, and others find their bodies, but rally for another assault.

5.4 Young Cato is killed: Lucillius, claiming to be Brutus, is captured, but Antony is not deceived.

5.5 Brutus, among a few defeated followers, pauses to rest: one by one he asks three of them to kill him, saying he has seen Caesar’s ghost again and knows his time has come, but each refuses. After the others fly, however, Strato agrees to hold Brutus’ sword while he runs upon it, and Brutus dies saying he killed Caesar less willingly. Octavius and Antony find his body and speak of his virtues, distinguishing his high motives from those of the other conspirators.

Artistic features: Julius Caesar is both a triumphant display of rhetoric and a stringent examination of its uses and abuses, its characters lucid and eloquent even when persuading others to adopt the most violent and primitive behaviour. It employs a much higher proportion of verse than any other play composed at this period of Shakespeare’s career, determined to match its canonical classical subject with a consistently dignified style: the comic plebeians of 1.1 are swiftly dismissed, as is the comic poet who intrudes on Brutus and Cassius in 4.2.

Critical history: For precisely these reasons, the play has often been more admired than loved, seen as representing Shakespeare rather self-consciously on his best artistic behaviour. It has often been chosen as a school set text, due to its edifying subject and absence of bawdy (see schools, Shakespeare in), and has consequently retained an unfortunate aura of the classroom for many readers and commentators. Nonetheless, the admiration Julius Caesar has enjoyed has been genuine, consistent, and well deserved. Praised by *Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, during the Restoration, it became for the 18th century one of the most important plays in the canon, with Shakespeare seen as a sympathizer with Brutus’ libertarian ideals: Francis *Gentleman, commenting in *Bell’s edition in 1773, felt it should be a compulsory part of the syllabus at all major private schools and that all members of Parliament should be made to memorize it. (This wish was perhaps in part fulfilled by the election of a Prime Minister, Tony Blair, who as a private schoolboy was aptly cast as Antony.) It has always been especially valued in the United States, where phrases from its text littered the rhetoric of colonists during the War of Independence. Discussions of this perennially topical play have traditionally centred on the question of where its political sympathies finally lie. Brutus has generally been taken as its tragic hero (Charles *Gildon was the first critic to suggest the play should be renamed after him, in 1710), and he has been variously considered as an unambiguously endorsed personification of republican values, a Hamlet-like contemplative idealist too naive for public life, or a zealot committed to bloodless theories at the expense of flesh and blood. In the earlier 20th century the play’s structural kinship with two plays about regicide, Richard III and, especially, Macbeth, was frequently noted. Since the Second World War Julius Caesar has enjoyed the attention of *feminist critics interested in Portia’s wound and the play’s general relegation of women to the margins of a political world dominated by intense relationships between men, while *poststructuralists have been fascinated by its interest in the interpretation and misinterpretation of signs and its dramatization of the relations between texts, bodies, and wills.

Stage history: The play remained in the theatrical repertory down to the closing of the theatres in 1642 (court performances are recorded in 1612–13, 1637, and 1638), and its power in the theatre is highly praised by Leonard *Digges in his commendatory verse to Shakespeare’s poems (1640). After the Restoration its potentially sympathetic depiction of an assassination easily read as regicide kept it from being revived at once, but it was back on the boards by 1671, and after 1684 Thomas *Betterton took over the role of Brutus, with lasting success. Around 1688 the version of the play in use in London theatres was slightly rewritten to make Brutus more unambiguously sympathetic (adding, for example, a last defiant dialogue with Caesar’s ghost at Philippi, which remained part of its text until the retirement of J. P. *Kemble), but while it has frequently undergone minor cuts and transpositions the play was never supplanted by a full-scale adaptation (although the Jacobite statesman John Sheffield, Earl of Mulgrave, composed a heavily pro-Caesar version in two parts, The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, Altered and The Tragedy of Marcus Brutus, completed around 1716 but never performed). James *Quin played Antony in 1718 but in later years was an important Brutus, first at Drury Lane and then, throughout the 1740s and 1750s, at Covent Garden: David *Garrick, unsuccessful as Antony in Antony and Cleopatra, did not find any of the leading roles sufficiently commanding, and the play was not revived at Drury Lane during his entire management. Kemble’s 1812 production was notable both for his upright Brutus and for its attention to the historical accuracy of the actors’ togas: his most important immediate successor in the part was *Macready, who had earlier played Cassius. The play had first been performed in America in 1774, in Charleston, but enjoyed its greatest vogue during the following century (when it was played in 51 different theatres in New York alone): most famously (and infamously), it was a favourite of the *Booths, Edwin playing Brutus on tours throughout the States. A benefit performance of the play in 1738 had helped pay for *Scheemakers’s statue of Shakespeare in Westminster Abbey, and another took place in New York in 1864 to pay for the statue of Shakespeare in Central Park. Edwin Booth played Brutus, Junius Booth was Cassius, and John Wilkes Booth played Antony; a year later he shot Abraham Lincoln. The play was less popular in England during the later 19th century, but enjoyed considerable success in Beerbohm *Tree’s lavish production of 1898, with himself as Antony. Thereafter it became a standard feature of the repertory at Stratford under Frank *Benson, who played Caesar: it was chosen as the command performance to commemorate the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s death in 1916, at the close of which Benson, still in costume, was knighted by George V. Julius Caesar also became a fixture at the Old Vic, where it was revived in every season from 1914 to 1923, and again in 1932, with Ralph *Richardson as a much-praised Brutus. The most famous inter-war production, however, took place at the Mercury theatre in New York, when Orson *Welles directed the play in modern dress, giving the conspiracy strong anti-fascist overtones: the idea was imitated at the Embassy theatre in London soon after the outbreak of war. Notable post-war productions have included Anthony *Quayle’s in Stratford in 1950 (with Quayle as Antony and John *Gielgud as Cassius), Minos Volanakis’s production of 1962 (with Robert Eddison as Cassius), and Peter *Hall’s interval-free production for the RSC in 1996, with Hugh Quarshie as Antony. The play has remained popular on the stage, both as star vehicle and political think piece, with David Farr’s heavily mediatized production (RSC, 2004) examining the nexus between behind-the-scenes power brokering and the concomitant interview spin doctoring, so redolent of the coverage of the Iraq invasion at the time. Deborah *Warner’s modern-dress, politically unspecific 2006 production at the Barbican went for raw star power, with Ralph *Fiennes as Antony, Simon *Russell Beale as Cassius, and Anton *Lesser as a tetchy Brutus. Harriet *Walter played Brutus in opposition to Frances Barber’s Caesar in Phyllida Lloyd’s 2012 Donmar production, set in a high-security women’s penitentiary, while Gregory *Doran’s 2012 RSC production, set in an unspecified African nation with Jeffery Kissoon’s Caesar its Mugabe-esque dictator figure, was a source of tangled audience debate both for its geopolitical and racial representations.

Michael Dobson, rev. Will Sharpe

On the screen: Nine silent versions (the first made by Georges Méliès) emerged between 1907 and 1914. Material from the play was among the earliest Shakespeare scenes broadcast on BBC television (1937) and in 1938 the BBC televised the Embassy’s modern-dress production, reflecting the play’s relevance to the political turmoil in 1930s Europe. The film with the strongest resonance remains the 1953 cinema film directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz with Louis Calhern (Caesar), James Mason (Brutus), John Gielgud (Cassius), and Marlon Brando as Mark Antony. The most recent screen version since the 1979 BBC TV production, with Charles Gray as Caesar and Richard *Pasco as Brutus, is the BBC version of Gregory Doran’s 2012 production, which combined scenes filmed in the original stage space with location shots. The lengthy clandestine dialogue between Paterson Joseph’s Brutus and Cyril Nri’s Cassius in 1.2, for example, moves off the stage into a deserted corridor, and thence to an equally deserted men’s toilet as the need for conspiratorial privacy heightens.

Anthony Davies, rev. Will Sharpe