q

Q, the bibliographic abbreviation for *quarto: hence ‘Q1 Hamlet’ (or Hamlet Q1’) means ‘the first quarto edition of Hamlet’, ‘Q2 Hamlet’ means ‘the second quarto edition of Hamlet’, and so on.

Michael Dobson

‘Q’. See Quiller-Couch, Sir Arthur.

quartos. A book in which the printed sheet is folded in half twice, making four leaves or eight pages, is known as a quarto. Renaissance play quartos were about the size and shape of modern comic books and sold for sixpence. About half of Shakespeare’s plays were printed during his lifetime, usually in quarto format (see printing and publishing).

The acting companies for which Shakespeare wrote held the legal copy rights to his manuscripts. Theatre historians have traditionally maintained that the players were reluctant to allow their plays to be printed, either because they feared losing exclusive acting rights to another company or because they believed that the sale of printed texts might reduce the demand for performance. Thomas *Heywood referred to certain play-texts as being ‘still retained in the hands of some actors, who think it against their peculiar profit to have them come in print’. And yet, when unauthorized versions of Shakespeare’s plays occasionally reached print, the acting companies—whether motivated by commercial interests or pride—moved quickly to supersede these texts with authorized versions: Q1 Romeo and Juliet (1597) was soon followed by Q2 (1599), advertised as ‘newly corrected, augmented, and amended’; similarly, Q1 Hamlet (1603) was followed hard upon by Q2 (1604/5), which claimed to be ‘newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much again as it was, according to the true and perfect copy’. The earliest extant quarto of Love’s Labour’s Lost (1598), advertised as ‘newly corrected and augmented’, may also have been intended to replace an earlier and incomplete edition.

The first of Shakespeare’s plays to appear in print—Titus Andronicus (1594), The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI) (1594), and The True Tragedy of Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI) (1595)—were part of a wave of 27 play quartos printed between December of 1593 and May of 1595. Given that the theatres had been closed in the *plague years 1592–3, A. W. Pollard argued that the unemployed players were motivated by financial hardship to sell their manuscripts during this period. But since most of these quartos were, in fact, published after the theatres reopened, Peter W. M. Blayney has suggested that acting companies may have been prompted to flood the market with printed plays as a means of advertising the reopening and generating renewed interest in the stage after a two-year lull. Observing that a large number of plays owned by the Chamberlain’s Men were printed in the years 1599–1600, Gary Taylor has proposed that the company may have been trying to raise capital around the time of their move into the *Globe theatre.

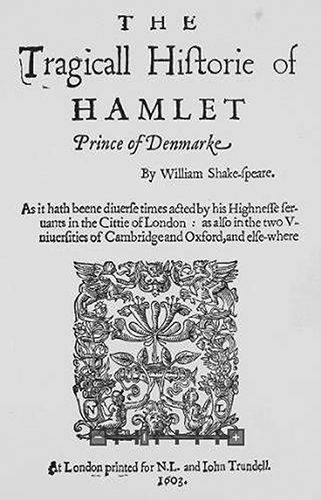

Nine early quartos were printed from Shakespeare’s own *foul paper manuscripts: Titus Andronicus (1594), Richard II (1597), Love’s Labour’s Lost (1598), Q2 Romeo and Juliet (1599), Much Ado About Nothing (1600), 2 Henry IV (1600), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1600), Q2 Hamlet (1604), and The History of King Lear (1608). Another four quartos seem to have been printed from fair copy transcripts of the foul papers: 1 Henry IV (1598), The Merchant of Venice (1600), Troilus and Cressida (1609), and Othello (1622). Eight quartos may represent reported texts: The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI) (1594), Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI) (1595; technically an octavo rather than a quarto), Q1 Romeo and Juliet (1597), Richard III (1597), Henry V (1600), The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602), Q1 Hamlet (1603), and Pericles (1609). (For a list of the printers and publishers of each of these quarto editions, see printing and publishing.)

During Shakespeare’s lifetime, there was a thriving industry devoted to reprinting his plays, especially the histories: Richard II, Richard III, and 1 Henry IV were each reprinted five times in quarto between the years 1597 and 1615. Remarkably, there was not a single Shakespearian play published in the three years following the dramatist’s death in 1616. In 1619, Thomas Pavier, who owned the rights to several history plays, reprinted ten of Shakespeare’s works, including The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI) and The True Tragedy of Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI), which were joined together with a common title, The Whole Contention, along with Q3 Pericles, Q2 The Merry Wives of Windsor, Q2 The Merchant of Venice, Q2 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Q2 King Lear, and Q3 Henry V. The supposition that these individual quartos were intended to be bound together to form a collection of Shakespeare’s plays is encouraged by the signatures, which are continuous from The Whole Contention through to Pericles. The King’s Men apparently heard about Pavier’s planned collection and invoked the protection of authority. On 3 May 1619, the court of the Stationers’ Company had before it a letter from the Lord Chamberlain, whereupon it was ordered that in the future ‘no plays that his majesty’s players do play’ should be printed without the consent of the King’s Men. It seems that presswork was already completed on a number of Pavier’s texts, which are correctly dated 1619; but the question was what to do with the plays yet to be printed. W. W. Greg suggested that since ‘it was no longer safe to put the current date on the titles … it was decided that the dates on the titles should be those of the editions that were being reprinted, so that if necessary the reprints could be passed off as copies of the same, or at any rate as twin editions of the same date’. Thus, Pavier’s quartos of King Lear and Henry V were dated ‘1608’, and The Merchant of Venice and A Midsummer Night’s Dream were dated ‘1600’.

The substantial number of quartos that appeared in 1622—Q1 Othello, Q6 Richard III, Q6 1 Henry IV, Q4 Romeo and Juliet, and Q4 Hamlet—may indicate that publishers were attempting to capitalize on the renewed interest in Shakespeare generated by the advance publicity for the *First Folio. Another spate of quarto reprints appeared in and around 1632, the year in which the Second Folio was published, suggesting again that quartos were being offered as less expensive alternatives for readers who could not afford to purchase folio volumes.

The Shakespearian quartos published in the latter half of the 17th century often present the version of the play that was then current on the Restoration stage. In the ‘players’ quartos’ of Hamlet (1676, 1683, 1695), for instance, the diction is modernized and the scenes and passages that were omitted from the production (which starred Thomas *Betterton) are marked with marginal inverted commas. The 1674 and 1695 quartos of Macbeth reproduce *Davenant’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s play, ‘with all the alterations, amendments, and additions’.

The title page of the ‘bad’, first quarto of Hamlet, 1603.

The title page of the ‘good’, second quarto of Hamlet, 1604.

Eric Rasmussen

Quayle, Sir Antony (1913–89), British actor and director. Having played at the *Old Vic before distinguished war service, he impressed as Enobarbus in a London Antony and Cleopatra. At Stratford-upon-Avon in 1948 he played Claudius, Iago, and Petruchio and directed two plays, impressing the governors, who appointed him director, 1949–56. An astute administrator, he enlisted actors of the calibre of Peggy *Ashcroft and John *Gielgud. His major achievement was the 1951 cycle of history plays; he co-directed and played Falstaff. His other comic parts included Bottom and Pandarus. He was impressive as Coriolanus and as Aaron in Titus Andronicus. Playing Othello on an Australian tour he was outshone by Leo McKern as Iago (who was soon replaced). He later acted *Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great in North America, toured Britain as King Lear for the Prospect Theatre Company (1978), and in 1981 set up his own, unsubsidized touring company, Orbit, for which his roles included Prospero.

Michael Jamieson

Queen Anne’s Men. See companies, playing; Stratford-upon-Avon, Elizabethan, and the theatre.

Queen Margaret; or, Shakespeare Goes to the Falklands, an anonymous satirical parody published in The Economist (Christmas 1982), exemplifies the survival of Shakespearian *burlesque. In this skit 213 extracts from Shakespeare’s plays are adapted, with embarrassing appropriateness, into a three-act drama for Margaret Thatcher and the other political protagonists (British, American, and Argentine) of the Falklands military campaign.

Tom Matheson

queens. (1) Wife of Cymbeline and mother of Cloten (by her first husband), she hatches various evil plots which are uncovered in her deathbed confession, reported by Cornelius, Cymbeline 5.6.25–61. (2) Wife of Richard II, she last sees him on his way to the Tower, Richard II 5.1. Historically, Richard’s wife at this time (Isabella, daughter of Charles VI of France) was only 11 or 12 years old. (3) Three queens successfully plead with Theseus to avenge their husbands by raising a force against Creon, The Two Noble Kinsmen 1.1.

Anne Button

Queen’s Men. See companies, playing; Stratford-upon-Avon, Elizabethan, and the theatre.

Quickly, Mistress. In 1 Henry IV she appears as the hostess of a tavern in Eastcheap and has an argument with Sir John (3.3). In 2 Henry IV, now a widow, she tries to have him arrested for debt, 2.1, and claims that he has promised to marry her. She is one of the protagonists in the ‘tavern brawl’ scene (2.4) and is taken to prison with Doll Tearsheet in 5.4. In Henry V, now married to Pistol, she describes the death of Falstaff in a celebrated prose speech which is at once comic and moving, 2.3.9–25, and her own death is announced, 5.1.77. In The Merry Wives of Windsor she is *Caius’ housekeeper. Falstaff does not know her when he meets her (is she the same character as in the other plays?—compare 2 Henry IV 2.4.386–8). She appears disguised as the fairy queen at the end of the play. She is frequently mistaken or unwittingly tactless in her choice of words, sometimes producing double entendres (conceding of Falstaff’s conversation, for example, ‘A did in some sort, indeed, handle women’, Henry V 2.3.34). Shakespearian critics, consequently, often prefer the term ‘Quicklyism’ for this comic device to the commoner but here anachronistic ‘malapropism’ (a term derived from Sheridan’s Mrs Malaprop in The Rivals, 1775).

Mistress Quickly’s lines were severely bowdlerized in the 19th century. The tavern brawl scene was often omitted because, according to Constance Benson, who played the role in the 1890s, ‘no principal actress will condescend to speak but two speeches’. Twentieth-century directors have also cut her lines: the arrest of Quickly and Tearsheet has often been dispensed with, for example, because it has appeared digressive, though it has also been played as a brutal prefiguration of a police-state to come under Henry V (as in Michael Attenborough’s RSC production, 2000). Memorable Mistress Quicklys have included June Watson in Michael *Bogdanov’s 1986 production (who repeatedly hit the men on stage in the groin with her shopping bag), Judi *Dench in Kenneth Branagh’s film of Henry V (1989), and Margaret Rutherford in Orson *Welles’s Chimes at Midnight (1966), an ageing female counterpart to Falstaff.

Anne Button

Quiller-Couch, Sir Arthur (1863–1944), English writer, editor, and critic, in some respects the archetypal ‘liberal man of letters’. Known as ‘Q’, he edited several influential Oxford Books: of English Verse; Ballads; Victorian Verse; and English Prose. Shakespeare’s Workmanship, based on his Cambridge lectures, dates from 1918, but his widest readership was gathered by the earlier volumes of the Cambridge *New Shakespeare, jointly edited with John Dover *Wilson, for which ‘Q’ wrote the general introduction as part of the first volume, The Tempest (1921).

Tom Matheson

Quin, James (1693–1766), actor and manager. He was born in London and gave his earliest performances in Dublin. He came to prominence in the 1716–17 season at Drury Lane where his roles included Gloucester and Guildenstern. His subsequent popularity and reputation rests largely on his personation of Falstaff, whose lifestyle his was thought to resemble, and the role is recorded in pictures by *Hayman and McArdell, and in Bow, Derby, and Staffordshire figurines. He is also the subject of portraits by *Hogarth, Gainsborough, and Hudson.

In fact Quin had a large Shakespearian repertoire: from 1718 he was at Lincoln’s Inn Fields where he played Othello, Cymbeline, Hector and Thersites, Lear, Buckingham, and the Duke in Measure for Measure, as well as Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor and 1 Henry IV. He played Apemantus in the opening season (1732) of the new *Covent Garden theatre, and Othello, Falstaff, Brutus, and the Ghost in Hamlet at Drury Lane the following year, roles to which he added Jaques in 1740. For most of the 1740s and early 1750s he appeared regularly at Covent Garden and with his contrasting, somewhat old-fashioned declamatory style was seen as the rival of the more naturalistic *Garrick at Drury Lane. The two were friends and occasionally performed together (Quin as Falstaff and Garrick as Hotspur in 1746), and Garrick wrote the epitaph for Quin’s tomb in Bath abbey.

Catherine Alexander

Quince, Peter. He is a carpenter in A Midsummer Night’s Dream who allots the parts to the actors of ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ and himself speaks the prologue, 5.1.126–50.

Anne Button

Quiney, Richard (before 1577–1602). Father of Judith *Shakespeare’s husband, and writer of the only surviving letter addressed to Shakespeare. Alderman of Stratford-upon-Avon in 1588 and bailiff in 1592, he regularly visited London on town affairs. In 1598 he was there to petition for a more favourable charter and for tax relief because of declining trade and hardship caused by fires in 1594 and 1595. On 25 October 1598 while staying at an inn near St Paul’s he wrote a letter endorsed ‘To my loving good friend and countryman Mr William Shakespeare deliver these.’ Whoever was to bear the letter appears to have been expected to know where to find him—presumably in London. It reads:Loving countryman,

I am bold of you as of a friend, craving your help with £30 upon Mr Bushell’s and my security or Mr Mytton’s with me. Mr Roswell [probably Thomas *Russell] is not come to London as yet and I have especial cause. You shall friend me much in helping me out of all the debts I owe in London, I thank God, and much quiet my mind which would not be indebted. I am now towards the court in hope of answer for the dispatch of my business. You shall neither lose credit nor money by me, the Lord willing, and now but persuade yourself so as I hope and you shall not need to fear but with all hearty thankfulness I will hold my time and content your friend and if we bargain farther you shall be the paymaster yourself. My time bids me hasten to an end and so I commit this [to] your care and hope of your help. I fear I shall not be back this night from the court. Haste. The Lord be with you and with us all, Amen. From the Bell in Carter Lane, the 25 October 1598.

Yours in all kindness,Ric[hard]. Quiney

Stanley Wells

Quiney, Thomas (1589–?1662–3), Shakespeare’s son-in-law, husband of Judith *Shakespeare. He was baptized at Stratford on 26 February 1589, the third son of Richard *Quiney. By 1608 he was managing his widowed mother’s business as a tavern-keeper and wine merchant, and in 1611 rented the tavern next to his mother’s house in High Street. He married Judith Shakespeare on 10 February 1616 and less than six weeks later, on 26 March, was prosecuted for ‘incontinence’ with Margaret Wheeler, who, with her child, had been buried on 15 March. In July, Thomas and Judith moved to the Cage, a building which still stands on the corner of High Street and Bridge Street. They had three sons (see Shakespeare, Judith). His name appears from time to time in Stratford records until at least 1650, and in 1655 his brother Richard left him an annuity. His death is not recorded, but there is a gap in the register in 1662–3.

Stanley Wells

Quintus is one of Titus’ sons in Titus Andronicus. With his brother Martius he is executed for the murder of Bassianus, 3.1, who has really been killed by Demetrius and Chiron.

Anne Button