c

Cade, Jack. A rebel leader, Cade is slain by Iden (The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI) 4.10). Shakespeare largely follows *Holinshed’s account of the rebellion.

Anne Button

‘Cadwal’ is the name given to Arviragus by Belarius in Cymbeline.

Anne Button

Caesar, Julius (102–44 bc), dictator of Rome. See Julius Caesar .

Anne Button

Caesar, Octavius (63 bc–ad 14). In Julius Caesar he becomes one of the triumvirs after the murder of Caesar, and in Antony and Cleopatra after eliminating the other triumvirs he assumes sole leadership of the Roman Empire.

Anne Button

caesura, a pause within a line of verse, often coinciding with a break between clauses or sentences. In English iambic pentameter (unlike classical verse), a caesura or phrasal break may fall after any syllable from the first to the ninth.

Chris Baldick

caesura, epic (feminine). Within an iambic pentameter line, epic caesura is a phrasal break preceded by an extra unstressed syllable. Older (mainly 15th-century) poets used this pattern as a standard variation, but most 16th-century poets avoided it. Shakespeare, too, avoids it in his poems but uses it fairly frequently in his middle and later plays, evidently to vary and complicate the metrical design:

Stealing and giv | ing odour. | Enough, no more

(Twelfth Night, 1.1.7)

George T. Wright

Cahiers élisabéthains, the chief French journal of late medieval and English Renaissance studies, was launched in 1972. It was originally published by the Centre d’Études et de Recherches sur la Renaissance Anglaise (Université Paul-Valéry, Montpellier, France) and is intended as a link between scholars working in its field in France and those working elsewhere in the world. An international editorial board screens submissions. Nearly all texts are written in English: abstracts in both French and English are systematically included. Two numbers are published each year, including articles, notes, and reviews of relevant critical works, theatre performances, and films. In 2014 it partnered with Manchester University Press, which is now responsible for its publication both in print and online.

Jean-Marie Maguin, rev. Erin Sullivan

Caithness, Thane of. He marches against Macbeth, Macbeth Act 5.

Anne Button

Caius is one of Titus’ kinsmen in Titus Andronicus (mute part).

Anne Button

‘Caius’. See Kent, Earl of.

Caius, Dr. He is a French physician in love with Anne Page in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Anne Button

Caius Cassius. See Cassius, Caius.

Caius Ligarius. See Ligarius, Caius.

Caius Lucius. See Lucius, Caius.

Caius Marius, The History and Fall of. First performed in 1679, Thomas Otway’s play is heavily and explicitly indebted to Romeo and Juliet, transferring its action to the Roman civil wars of Marius and Sylla. Shakespeare’s love story serves as a tragic sub-plot to Otway’s depiction of the struggle between the patricians Metellus and Sylla and the plebeians’ leader Marius: Marius’ son is in love with Metellus’ daughter Lavinia, to whom he was betrothed before Metellus defected to Sylla’s rival faction, and they marry in secret despite their parents’ enmity. (‘O Marius, Marius, wherefore art thou Marius?’, wonders Lavinia). Although Young Marius and Lavinia are more blameless than their Shakespearian counterparts (they fall in love in compliance with their parents’ original wishes, and he kills no Tybalt), they finish up in the tomb just the same, and Otway enhances the pathos of their deaths by having Lavinia awaken before Young Marius has finished dying of the poison so that they can enjoy one last brief and tormented interview. Otway’s play was still being revived at intervals as late as the 1760s, and its final dialogue between the lovers was imitated in acting texts of Romeo and Juliet from its return to the repertory in the 1740s until well into the 19th century.

Michael Dobson

Calchas, father of Cressida, is a Trojan priest who has defected to the Greeks in Troilus and Cressida.

Anne Button

calendar, Shakespeare’s. Protestant countries, including England, still used the Julian calendar (established by Julius Caesar) in Shakespeare’s day, though Catholic countries had accepted the more accurate ‘New Style’ Gregorian calendar in 1582 (named after Pope Gregory XIII). Consequently dates were the subject of debate, particularly the date of Easter, which was five weeks apart for Catholics and Protestants by 1599. Britain and its colonies only converted to the Gregorian calendar in 1752. At the same time New Year’s Day was moved from 25 March (the feast of the Annunciation and Lady Day) to 1 January (a date which had been originally rejected by Christians because it was associated with a celebration of the god Janus). In Shakespeare’s day the date of the year changed in March not January.

The following list gives the dates of festivals and other significant days, many of which are no longer celebrated, mentioned by Shakespeare in his plays.

Twelfth Night—6 January

The last day of the Christmas festival was an opportunity for carnivalesque misrule: carousing, practical jokes, and ribald impersonation of authority figures (elements which appear in Twelfth Night).

St Valentine’s Day—14 February

Valentine’s Day was traditionally associated with the pairing of birds, and is mentioned in this context in A Midsummer Night’s Dream 4.1.138 (see also Chaucer’s The Parliament of Fowls (?1381). In Elizabethan England it was celebrated with games and an atmosphere of sexual opportunity (as expressed in one of Ophelia’s songs, Hamlet 4.5.47). It is probably no coincidence that the ancient Roman festival of Lupercalia, also a celebration of fertility, was held on the same day or thereabouts. The Luperci would gather in a sacred cave, sacrifice goats, and clothe themselves in the goats’ skins from which they also made straps. They ran down the Palatine Hill striking anyone they met with their straps: being struck was supposed to cure infertility in women. Julius Caesar 1.2 is set during the celebration of Lupercalia.

Ides of March

Instead of using weeks the Romans divided their months in an irregular way originally based on the phases of the moon. Ides, from iduare, ‘to divide’, occurred in the middle of the month, on the 13th or 15th day, according to the length of the month, and originally represented the period during the full moon. Caesar is told to ‘Beware the ides of March’, Julius Caesar 1.2.20.

Dates associated with Easter

As it is today, Easter was a movable feast. In Elizabethan times the first of the dates associated with Easter, Shrove Tuesday, could fall as early as 3 February or as late as 9 March. The earliest possible date for Easter itself was 25 March. Shrove Tuesday, or Pancake Day, as it is still popularly known, is mentioned in All’s Well That Ends Well 2.2.22–3. Shrovetide, mentioned in 2 Henry IV 5.3.36., is the period of the few days before *Lent, when feasting and sports were customary (including football matches between villages, as at Easter). Ash Wednesday is the day after Shrove Tuesday and the beginning of fasting and abstinence of the 40-day period of Lent (ending on Easter Monday). It is mentioned in The Merchant of Venice 2.5.26. Friday of Easter week, Good Friday, is mentioned as a day of fasting, King John 1.1.235, 1 Henry IV 1.2.114. Ascension Day is the 40th day after Easter: ‘Holy Thursday’. Peter of Pomfret says John must give up his crown ‘ere the next Ascension Day at noon’, King John 4.2.151. The week succeeding the seventh Sunday after Easter, Whitsun, was a time for sports and games (especially morris dancing) and carousing (even in the churchyard itself, hence the term ‘church ale’). Whitsun is mentioned: The Winter’s Tale 4.4.134; Henry V 2.4.25; and is pronounced ‘Wheeson’ by Mistress Quickly in 2 Henry IV 2.1.91.

May Day—1 May

Morris dancing, decorating and dancing round the maypole, the election of a summer King and Queen, and general frolicking in the woods (particularly among young people) were popular May Day activities. May Day morris dancing is mentioned in All’s Well That Ends Well 2.2.23 and dramatized in The Two Noble Kinsmen 3.5; May Day morning is mentioned in All Is True (Henry VIII) 5.3.14.

Midsummer—24 June

The 24th of June was celebrated as the summer solstice (though it was actually 12 June then and 21 June now) and the feast of St John the Baptist. Midsummer is mentioned in As You Like It (4.1.95) and 1 Henry IV (4.1.103), as well as in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Olivia says that Malvolio suffers from ‘midsummer madness’, Twelfth Night 3.4.54, referring to the revelry, magic, and atmosphere of disorientation that was associated with the moon at the summer solstice.

Lammas—1 August

Lammas Eve, the day before Lammas, is mentioned as Juliet’s birthday, Romeo and Juliet 1.3.19. Lammastide, the season of Lammas, is mentioned in Romeo and Juliet 1.3.16. Lammas is from the Anglo-Saxon hlaf-maesse, ‘loaf mass’—it was originally a harvest festival, but by Elizabethan times was merely the date on which pastures were opened for common grazing.

St Bartholomew’s Day—24 August

Bartholomew-tide is mentioned in Henry V 5.2.306 as the hottest day of summer.

Holy-rood Day—14 September

It is mentioned in 1 Henry IV 1.1.52 as the day of the battle between Hotspur and Douglas. Holy-rood Day was a festival commemorating the exaltation of Christ’s cross after its recovery from the Persians by Heraclius in ad 628, but by Shakespeare’s day was principally associated with the custom of ‘going a-nutting’—like May Day, an opportunity for young people to meet in the woods.

St Lambert’s Day—17 September

The day is mentioned in Richard II 1.1.199 as the date set by Richard for Bolingbroke and Mowbray’s combat.

Michaelmas—29 September

The festival of St Michael and All Angels is mentioned in 1 Henry IV 2.5.53 as Francis’s birthday; and in The Merry Wives of Windsor 1.1.188 (see also Allhallowmas). It was the day on which the universities of Oxford and Cambridge and the law schools and courts of London began their terms. As with Lammas, by the Elizabethan period most of the customs associated with this day had lapsed, though it remained a time for hiring servants, initiating lawsuits, signing contracts, and harvesting and selling crops.

All Hallows Eve—31 October

The eve of All Saints is mentioned in Measure for Measure 2.1.121. In Shakespeare’s day games were organized in order to ward off the spirits of the dead and exploit the magic associated with this night.

Allhallowmas/Hallowmas—1 November

The feast of All Saints. Simple says Allhallowmas falls a fortnight before Michaelmas (29 September), either having confused it with Holy-rood Day (14 September), or having confused Martinmas (11 November) with Michaelmas, The Merry Wives of Windsor 1.1.187. Prince Harry calls *Oldcastle ‘All-hallown summer’, 1 Henry IV 1.2.156, a term referring to a spell of fine weather in late autumn. ‘Hallowmas’ and ‘Hollowmas’ are abbreviated forms of ‘Allhallowmas’, mentioned in Two Gentlemen of Verona 2.1.24; and Measure for Measure 2.1.120. Richard compares Hallowmas to the ‘short’st of day’ Richard II 5.1.80. Because of discrepancies in the Julian calendar the winter solstice was ten days earlier than it is now, consequently this made rather more sense in Shakespeare’s day than it does in ours.

All Souls’ Day—2 November

Catholics offer prayers for the dead on All Souls’ Day, and it is the day of Buckingham’s doom, Richard III 5.1.

St Martin’s Day/Martinmas—11 November

Joan la Pucelle means a spell of unseasonably fine weather when she refers to ‘Saint Martin’s summer’ 1 Henry VI 1.3.110. Martlemas is another term for ‘Martinmas’. Poins calls Falstaff ‘Martlemas’ 2 Henry IV 2.2.95, perhaps alluding to St Martin’s summer (compare Prince Harry’s ‘All-hallown summer’); or to Martinmas beef, fattened for slaughter by that date.

Anne Button

Calhern, Louis (1895–1956), American actor-director who progressed from undistinguished stage work to a high-profile career in film (playing the title role in the 1953 MGM film of Julius Caesar), returning to the theatre occasionally, including King Lear in 1950.

Richard Foulkes

Caliban. Long before the action of The Tempest begins, Prospero arrives on the island to find its sole inhabitant, the son of the deceased witch Sycorax. At first their relationship is harmonious: Caliban loves Prospero and shows him ‘all the qualities o’th’isle’ (1.2.339); and Prospero treats him ‘with human care’ (1.2.348) and teaches him language. However, when Caliban attempts to rape Miranda, Prospero enslaves him. During the course of the play Caliban offers his services to Trinculo and Stefano, who he mistakenly believes will be able to help him vanquish Prospero.

Critics, audiences, writers, and artists have shared a long fascination with Caliban. In the *Dryden/Davenant adaptation the low comedy of Caliban’s situation was given extra impact by the addition of a female version of him, a sister. Later generations have been more interested in the tragedy of his situation: his occasionally beautiful language and miserable situation seem to invite sympathy despite his ugly appearance and violent intentions. In the last two decades of the 20th century criticism and theatre productions have often seen Caliban as a native islander. To be precise, however, he is a second-generation immigrant and the mythologies and psychology of Europeans are just as important as postcolonial perspectives in the debate over his identity.

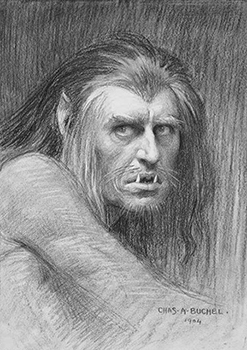

Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Caliban, 1904. Tree played Caliban as a sensitive, potentially noble creature, a tragic missing link.

Anne Button

‘Calin o custure me’, a *ballad tune title, probably Gaelic in origin, quoted by Pistol in Henry V 4.4.4.

Jeremy Barlow

Calpurnia is Caesar’s wife in Julius Caesar. Frightened by a dream and ill portents she tries to persuade him not to go to the Capitol, 2.2.

Anne Button

Calvert, Charles (1828–79), actor, born in London. His early engagements included Southampton (1853–4, Romeo and Laertes with his future wife Adelaide Biddles as Juliet and Ophelia) and the Surrey (1855–6, Hal, Othello), but it was with Hamlet (1859) at the Theatre Royal, Manchester, that Calvert showed his ability to co-ordinate all the arts of the theatre in the service of the play. At the Prince’s theatre, Manchester, between 1864 and 1874, he mounted eleven major Shakespeare revivals, of which Richard III and Henry V were transferred to New York.

A disciple of Charles *Kean, Calvert upheld the principles of pictorial Shakespeare and showed his intelligence and originality as an actor in his sympathetic Shylock and thoughtful Henry V.

Richard Foulkes

Calvert, Louis (1859–1923), English actor-manager who upheld the Shakespearian tradition of his parents Charles and Adelaide Calvert. His career encompassed the diversity of Shakespearian staging on both sides of the Atlantic—and beyond—for half a century. Calvert acted with *Benson and *Tree, assisting the latter with his ambitious revival of Julius Caesar (1898), as he did Richard Flanagan with his sumptuous Shakespearian productions in Manchester where—in contrast—Calvert also staged Richard II (1895) in the Elizabethan style for the Manchester branch of the Independent Theatre. In 1909 Calvert was recruited for the ill-fated New Theatre, New York, where his production of The Winter’s Tale (1910) prefigured *Granville-Barker’s. Calvert remained in America, contributing an Elizabethan-style The Tempest to the Shakespeare tercentenary of 1916, but devoting himself increasingly to training actors in the traditions of Shakespearian acting, about which he wrote in Problems of the Actor (1918).

Richard Foulkes

Cambridge, Richard, Earl of. He is Richard Plantagenet (d. 1415), father of the Duke of York of the Henry VI plays. His plot with Henry le Scrope (3rd Baron of Masham, eldest son of Sir Stephen Scrope) and Sir Thomas Grey is discovered and they are sent to execution, Henry V 2.2.

Anne Button

Cambridge Shakespeare. The Works of William Shakespeare (1863–6), edited by William George Clark, with at first W. Aldis Wright and later John Glover as collaborators, was published in nine volumes by Macmillan, but printed at the University Press, so that it became known as the Cambridge Shakespeare. This important edition was based on a ‘thorough collation of the four Folios and of all the Quarto editions of the separate plays, and of subsequent editions and commentaries’ (preface), so that in textual matters it constitutes a virtual variorum. Prefaces provide accounts of the early textual history of each of the works, and the volumes include the texts of first quartos of Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet, as well as the quartos relating to Henry V, The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI), and Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI). Clark and Wright used the Cambridge edition as the basis for the influential one-volume *Globe Shakespeare. Both the Cambridge and the Globe editions were revised in 1891.

R. A. Foakes

Cambridge Shakespeare, New (1984–2012) This edition was a replacement for the *New Shakespeare, completed in 1966. Whereas the New Shakespeare was edited by British scholars, the New Cambridge Shakespeare recruited editors from other countries, especially the United States. The series aimed to reflect ‘current critical interests’ and to be attentive ‘to the realisation of the plays on the stage, and to their social and cultural settings’, according to the first general editor, Philip Brockbank. The volumes are handsomely printed, with notes and collations on the same page as the text. Textual problems are treated in a ‘Textual Analysis’ that follows the text, as in the New Shakespeare. The well-illustrated critical introductions in the first volumes added a separate stage history, but some later introductions have sought to integrate commentary on stage and film performances into critical accounts of the plays. Most of the earlier volumes have been re-issued in recent years with updated introductory material attempting to cover ever-shifting scholarly grounds, a process the series treats as ongoing. Beginning in 1994 with the first quarto of King Lear, it also added several critical editions of the early quartos. The New Cambridge began to appear roughly at the same time as, and in competition with, the *Oxford Shakespeare, with Romeo and Juliet, The Taming of the Shrew, Othello, Richard II, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the first year, completed in 2012 with the publication of The Two Noble Kinsmen.

R. A. Foakes, rev. Will Sharpe

Cambridge University’s major resource for the study of Shakespeare is the collection at Trinity College presented in 1799 by Edward *Capell of Shakespeare editions used in the preparation of his own edition of 1768 and his Notes and Readings (1774, 1779–83).

Susan Brock

Camden, William (1551–1623), antiquarian, historian, and teacher. Born in London, Camden was a distinguished compiler of British history and a gifted headmaster of Westminster School who won his pupil Ben Jonson’s unreserved praise. Having written Britannia (1586), he drew partly on that work for Remains of a Greater Work Concerning Britain (1605), in which he glances at modern poets. In a list of nine ‘pregnant wits’, Camden merely cites Shakespeare’s name, but on more congenial antiquarian ground, he explores the name’s antecedents and variants: ‘Strong-shield’ or ‘Breake-speare, Shake-Speare, Shotbolt, Wagstaffe’.

Park Honan

Camidius is given command of Antony’s land army, Antony and Cleopatra 3.7.57–9.

Anne Button

Camillo, a lord at Leontes’ court, helps Polixenes escape and is eventually betrothed to Paulina, The Winter’s Tale 5.3.144–7.

Anne Button

Campeius, Cardinal. Sent by the Pope, he, with Wolsey, considers King Henry’s proposed divorce of Katherine, All Is True (Henry VIII) 2.4.

Anne Button

Campion, Thomas (1567–1620). He wrote three masques, and published four Bookes of Ayres (1610–17). Campion’s Lord’s Masque, commissioned by the Howards for Princess Elizabeth’s wedding celebrations (1612–13), contains a moment reminiscent of Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale, also performed at Elizabeth’s wedding, when a row of women-statues step alive from their niches.

Cathy Shrank

Canada has most often employed Shakespeare as a bulwark against other traditions or cultures. In English Canada, Shakespeare served as protection against the incursions of American commercialism; in French Canada, against ‘double colonialism’ by the French and the English.

Despite the burden of wholesomeness imposed both by English-Scots Puritanism and French Roman Catholicism, there has been a nearly unbroken tradition of playing Shakespeare since at least the 18th century. The genealogy of Shakespeare productions may be traced back to two significant roots: British soldiers and touring companies. After the Conquest (1763), British soldiers staged plays to relieve the tedium of garrison life. However, most Shakespeare in the 18th century and up to 1914 was supplied by touring companies and by such actors as Edmund *Kean, William Charles *Macready, Ellen *Terry, Tommaso *Salvini, Sarah *Bernhardt, and Edwin *Booth.

In the 1840s, Shakespeare societies sprang up to fill a variety of cultural needs, including self-improvement. Ladies’ clubs admired Shakespeare for his creation of strong female characters; gentlemen lionized Shakespeare, the self-made man. Fuelled by British patriotism and fear of American domination, later societies (such as that founded in Toronto in the 20th century), celebrated Shakespeare’s birthday, organized reading groups and competitive recitations, and occasionally produced his plays.

A wider assimilation of Shakespeare came through provincial regulation of educational institutions, where excerpts, then plays, were used as rhetorical training in schools. By the 1860s in Ontario, and shortly thereafter at all other Canadian universities, Shakespeare was firmly in place as the keystone of the honours English undergraduate programme. Canadian Shakespearian scholarship was launched with Sir Daniel Wilson’s Caliban: The Missing Link (1873), but acquired eminence only with the extensive theoretical, interpretative, and editorial work of Northrop *Frye.

The real explosion of interest in Shakespeare, both in English and French Canada, occurred after 1945 and coincided with the growth of cities, the influx of many immigrant groups, the rapid development of technology, and debates about national identity and culture. Between 1944 and 1955, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation presented over 60 radio adaptations of Shakespeare, including the first ever complete and chronologically arranged performance of Shakespeare’s English history plays (1953–4).

Undoubtedly a major event was the creation of the Stratford Festival in Stratford, Ontario (1953), at the initiative of Tom Patterson, who recruited British director Tyrone *Guthrie and designer Tanya *Moiseiwitsch. Once a tent affair, the Stratford Festival is now the largest classical theatre in North America. Its inaugural production, Richard III with Alec *Guinness, was greeted with wild enthusiasm and set high standards. Michael Langham’s Henry V (1957), in which French-Canadians played the French, suggested that a unique Canadian Shakespeare might be possible. Instead, for many years, the Festival’s British roots often led to a dependency upon ‘hired hands’—British and American directors and actors. Later, the main stage gave way to an increasingly Hollywood-like emphasis on costumes, props, and gimmicks. Although the Festival has produced great actors such as Christopher Plummer and William Hutt, on the whole, the Festival’s international influence has been more architectural rather than theatrical; its thrust stage became the model for, among others, the Olivier auditorium at the National Theatre in London, and the Chichester Festival Theatre in Sussex.

While some scholars claim that the distinctiveness of Canadian Shakespeare lies in the ‘conversational vitality’ of its Shakespearian language, said to lack the ‘operatic excesses’ of the English and the ‘harshness’ of the American, others find distinctiveness elsewhere: for example, in Canadians’ preference for Shakespeare paired with a beautiful landscape. Since the 1980s, boisterous summer Shakespeare is found not only a mare usque ad mare (Wolfville, Halifax, St John’s, Montreal, Prescott, Toronto, Saskatoon, Calgary, Victoria, Vancouver, and Ottawa), but also by the sea, in a park, or on a golf course.

In Quebec, ‘Le grand Will’ was historically neither part of the school curriculum nor part of the repertoire of local professional acting companies. Not translated into Québécois (rather than a ‘placeless’ French) until 1978 by Michel Garneau, Shakespeare was, in the next two decades, often confined to being a vehicle, parodic or legitimizing, of cultural nationalism. Shakespeare’s political face may be clearly seen in Robert Gurik’s Hamlet, prince du Québec (1968), an allegory on Quebec politics with Hamlet as Québec, Claudius as l’Anglophonie (the English economic and political power), Gertrude as the Church (in alliance with the political power in Ottawa), and the Ghost as Charles de Gaulle.

By the 1990s, Quebec became more comfortable with Shakespeare and his works are now regularly staged. Best known is director/playwright/actor Robert *Lepage, who turned many times to Shakespeare in his explorations into multimedia, sexuality, and the act of creation itself.

Despite Canada’s diversity, until recently, multicultural and native Shakespeare was rare. A notable early effort was David Gardner’s Inuit-themed King Lear (1961–2). More recently, at the National Arts Centre, Peter Hinton directed an all-aboriginal cast of King Lear (2012) in a production set in 17th-century Canada and emphasizing the first early contacts and conflicts between Europeans and native peoples.

Shakespeare’s influence on Canadian culture, and drama in particular, has been mixed. The more unfortunate aspects of Shakespeare adoration may be seen in such imitative works as Charles Heavysege’s Saul (1857), described by Coventry Patmore in its day but never since as ‘scarcely short of Shakespearean’. Particularly in his status as Canada’s most popular playwright, Shakespeare has also come under increasing attack for impeding the growth of a Canadian drama. Yet Canadians feel impelled to engage his works. A strong, even acerbic, tradition of rewriting Shakespeare to satirize local politics began in the 18th century. Twentieth-century rewritings, of which there are more than 100, span a much wider spectrum of themes and issues and range from the serious to the outrageous: among them are John Herbert’s Fortune and Men’s Eyes (1967), a meditation on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29; Ann Marie MacDonald’s Good Night, Desdemona (Good Morning, Juliet) (1990), a comic consideration of gender and genre; Norman Chaurette’s Les Reines (1991; The Queens, 1992), Richard III reimagined from the point of view of the women of the play; Cliff Jones’s Kronberg: 1582 (1974), a pop/rock musical based on Hamlet, David Belke’s farcical mystery The Maltese Bodkin (1997); Tibor Egervari’s Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice in Auschwitz (1977, 1998; trans. 2009); Vern Thiessen’s Shakespeare’s Will (2002), a one-woman play exploring Anne Hathaway’s ‘reminiscences’; and Yvette Nolan and Cathy MacKinnon’s Death of a Chief (2008), a First Nations’ adaptation of Julius Caesar. Shakespearian adaptations, inspirations, and revisions have found their way into fiction, poetry, music, radio, television, online arcade games, the Internet, and smart phone apps. New theatre companies dedicated to staging Shakespeare continue to pop up, although they are sometimes short-lived. Toronto’s Shakespeare in Action aims at attracting high school students and educators, while Ottawa’s Company of Adventurers produces full-length plays with school-age children. Shakespeare’s Canadian presence has achieved international notoriety with the Sanders portrait. Revealing a puckish, red-haired, and youngish Shakespeare, the 1603 image owned by Lloyd Sullivan has entered the lists as a prime candidate for the only portrait of the Bard painted during his lifetime. Now firmly entrenched in schools, universities, theatres, and the public consciousness, Shakespeare has become a byword for literacy itself: Book Day Canada is celebrated on his birthday, 23 April.

Irena Makaryk

canaries, dance steps including percussive use of feet, or a lively, virtuosic couple dance involving those steps (see Love’s Labour’s Lost 3.1.11 and All’s Well That Ends Well 2.1.73); also a tune associated with the dance. The origin of the name is unknown, despite obvious speculation about the Canary Islands.

Jeremy Barlow

cancel. The technical term for a page that replaces one that has been removed by the printer. The original *title page of the 1609 *quarto of Troilus and Cressida, for instance, which advertised the play ‘As it was acted by the Kings Majesty’s servants at the Globe’, was cancelled during the printing process and replaced with a title page that makes no mention of a company or a theatre.

Eric Rasmussen

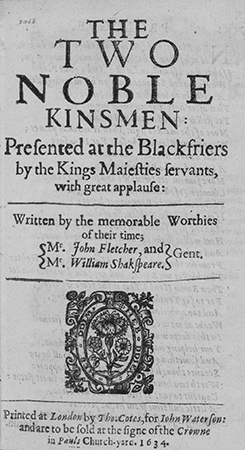

canon. The thirty-six plays in the First Folio form the authoritative canon of Shakespeare’s dramatic work. But, like the universe, the Shakespearian canon is ever expanding. Heminges and Condell may have deliberately excluded collaborative plays from their collection. Pericles, for instance, although ascribed to Shakespeare on the title page of the 1609 quarto, was omitted from the First Folio; the play later appeared in the Third and Fourth Folios and in Rowe’s editions, was excluded by Pope, but has been included in most collected editions of Shakespeare since Malone’s Supplement (1780) to Steevens’s edition. The Two Noble Kinsmen, ascribed to John Fletcher and Shakespeare on the title page of the 1634 quarto, appeared in the Beaumont and Fletcher Second Folio (1679) and in all subsequent editions of Beaumont and Fletcher’s works, but it was not until the 20th century that the play began to be included in editions of Shakespeare.

Scholars have explored a variety of forms of internal evidence (including tests of vocabulary, imagery, verbal and structural parallels, metrical evidence, stylometry, and function word tests) in the hopes of establishing the authenticity of other plays that are attributed to Shakespeare in early printed texts, such as The London Prodigal, Thomas Lord Cromwell, Sir John Oldcastle, The Puritan, A Yorkshire Tragedy, and Locrine. While none of these plays in the ‘Shakespeare Apocrypha’ has been admitted to the canon, others—which, with the exception of Double Falsehood, do not name Shakespeare in their earliest textual states—have. The 168 lines that Shakespeare contributed to the manuscript play Sir Thomas More, which was discovered in the British Museum in 1844, are widely accepted as genuine and often included in collected editions. Compelling arguments that Shakespeare was responsible for a few scenes in Edward III (c.1592) have recently propelled that play into some collected editions of Shakespeare’s work, bringing the total number of plays in the canon to 40. In 2010 the Arden *Shakespeare added to the number with Double Falsehood (see Cardenio), and convincing studies have amassed in recent years suggesting Shakespeare’s presence in *Arden of Faversham and in the 1602 revised text of *Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy.

Eric Rasmussen, rev. Will Sharpe

Canterbury, Archbishop of. (1) Based on Henry Chicheley (Chichele) (c. 1362–1443), his speech ‘proving’ King Harry’s title to the French Crown (Henry V 1.2) is taken largely from *Holinshed. (2) See Cranmer, Thomas.

Anne Button

Capell, Edward (1713–81), English Shakespearian editor. Capell’s ten-volume edition of Mr William Shakespeare his Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies (1768) was the first to be prepared according to recognizably ‘modern’ principles of eclectic editing. By a process of thorough collation Capell established which of the ‘old editions’ would be used as the ‘ground-work’ for the text of each play, and incorporated into this base text readings from the other early editions at points of variance, as his editorial judgement dictated. The 1768 edition was a beautifully printed ‘clean’ text, accompanied by only the briefest textual notes. It was belatedly followed by Capell’s remarkable explanatory apparatus, his Notes and Various Readings (vol. i, 1774; vols. i–iii, 1779–83), which included the School of Shakespeare, a collection of passages from Elizabethan and Jacobean literature chosen as illustrations of particular Shakespearian usages and cruces. The depth and originality of Capell’s textual work and contextualizing scholarship was matched and exceeded only by the great variorum editors *Steevens (who was not above unacknowledged borrowing from Capell) and *Malone.

Marcus Walsh

Caphis is the servant of one of Timon’s creditors in Timon of Athens.

Anne Button

Capilet, Diana. See Diana.

Capilet, Widow. See widows.

capitalization. Capitals were used in the early modern period not only to dignify names and proper nouns, but also to provide emphasis. Capitalization, like spelling, was largely a matter of individual preference. Shakespeare’s three pages in the Sir Thomas More manuscript reveal his characteristic habit of capitalizing initial ‘C’ in mid-sentence verbal forms (‘Come’, ‘Charg’, ‘Cannot’, ‘Cry’, ‘hath Chidd’, ‘Charterd’).

Eric Rasmussen

captains. (1) A captain of a ship condemns Suffolk to death, The First Part of the Contention (2 Henry VI) 4.1.71–103. (2) A captain announces the arrival of Titus, Titus Andronicus 1.1.64–9. (3) A captain of the Welsh army announces the dispersal of his troops, Richard II 2.4. (4) A captain is sent by Fortinbras to Claudius, Hamlet 4.4. He explains Fortinbras’ expedition to Hamlet in the second *quarto (see Hamlet Additional Passages ‘J’, lines 1–21). (5) A sea captain agrees to help Viola disguise herself as a eunuch, Twelfth Night 1.2. (6) A captain reports on the battle between Macbeth and Macdonald, Macbeth 1.2. (7) A Roman captain gives information to Lucius, Cymbeline 4.2. Two British captains arrest Posthumus, Cymbeline 5.5.92–5.

Anne Button

Capucius. See Caputius, Lord.

Capulet, Juliet’s father in Romeo and Juliet, is the head of the family opposed to the Montagues.

Anne Button

Capulet, Diana. See Diana.

Capulet, Lady. See Capulet’s Wife.

Capulet, Widow. See widows.

Capulet’s Cousin converses with Capulet, Romeo and Juliet 1.5.

Anne Button

Capulet’s Wife supports her husband in the proposed marriage of Juliet to Paris in Romeo and Juliet.

Anne Button

Caputius, Lord. He visits the dying Katherine and takes a letter from her to Henry, All Is True (Henry VIII) 4.2. He is based on the ambassador Eustace Chapuys, mentioned in *Holinshed.

Anne Button

Cardenio. The King’s Men were paid for performing a play referred to as Cardenno or Cardenna at court on 20 May and 9 July 1613, presumably based on the story of Cardenio told in Cervantes’ Don Quixote, which had first appeared in English translation in 1612. In September 1653 Humphrey *Moseley entered ‘The History of Cardenio, by Mr Fletcher and Shakespeare’ in the Stationers’ Register, but there is no evidence that he ever published it. (Some, however, suspect that the words ‘and Shakespeare’ are a later addition.) While he might have known that *Fletcher had dramatized material from Don Quixote elsewhere, and that he had collaborated with Shakespeare on The Two Noble Kinsmen (though not when), Moseley is very unlikely to have known that Shakespeare’s company had given performances of a play called Cardenno at court—at exactly the same time, moreover, that Shakespeare and Fletcher were also collaborating on All Is True (Henry VIII) and The Two Noble Kinsmen. Although Heminges and Condell, for whatever reason, omitted it from the *folio (just as they excluded Pericles, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and the mysterious *Love’s Labour’s Won: see canon), it seems likely that Shakespeare co-wrote Cardenio with Fletcher in 1612–13, and that a manuscript of the play was still extant in the 1650s.

Tantalizing glimpses of this otherwise lost play were provided in 1728 by the publication of Double Falsehood; or, The Distressed Lovers, ‘Written Originally by w. shakespeare; and now Revised and Adapted to the Stage by Mr. theobald’. Lewis *Theobald’s preface to this play, which was acted with considerable success at Drury Lane, states that it is an adaptation of an otherwise unknown work by Shakespeare, of which he claims to possess three copies in manuscript. (One of these was said to be in the library of Covent Garden theatre as late as 1770, but the playhouse burned down in 1808). Theobald’s preface, though arguing strenuously for the play’s authenticity, betrays no knowledge of either Moseley’s entry in the Stationers’ Register or the traces of Cardenio’s performances at court, so the otherwise extraordinary coincidence that Double Falsehood is in fact a version of the Cardenio story suggests that whatever Theobald possessed in manuscript must at least have derived from the missing Fletcher–Shakespeare Cardenio.

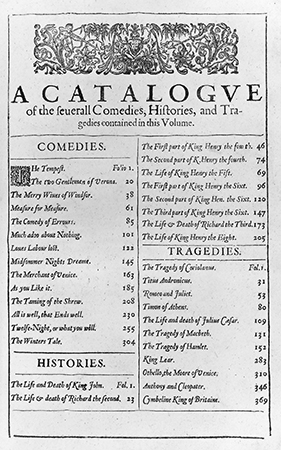

The catalogue of Shakespeare’s plays from the First Folio (1623). Troilus and Cressida, only included in the volume at the last minute, came too late to be listed; Pericles, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and the missing Love’s Labour’s Won and Cardenio were left out entirely.

If this is the case, however, Double Falsehood represents Cardenio only at one or more removes, its language heavily rewritten for a post-Restoration stage which found Fletcher’s style much more congenial than that of Shakespeare’s late romances (as is demonstrated by *Davenant’s version of The Two Noble Kinsmen, *The Rivals, which cuts most of the lines now attributed to Shakespeare). Nonetheless, some commentators have found lingering traces of Shakespearian imagery, and others have been impressed by the way in which Double Falsehood assimilates the Cardenio story to the characteristic patterns of Shakespearian romance. The play was even included in the *Arden 3 edition of Shakespeare’s works in 2010.

Various attempts have been made to ‘reconstruct’ Cardenio for performance, principally with student drama groups: the most notable of these has been Gregory *Doran’s ‘reimagining’ of Cardenio, performed by the *Royal Shakespeare Company in 2011.

Michael Dobson

Cardinal. In Richard III he reluctantly agrees that the Duke of York and his mother Queen Elizabeth should be brought out of the sanctuary (3.1) that he led them to in the previous scene. He is based on Thomas Bourchier (or Bouchier) (c. 1404–1486). In folio editions it is the Archbishop of York who leads them to sanctuary.

Anne Button

Carew, Richard (1555–1620), poet and antiquary. In his epistle The Excellencie of the English Tongue, printed in 1614, Carew cites Shakespeare as the lyric equal of the Roman poet Catullus. He adds, nevertheless, that for prose and verse the ‘miracle of our age’ is Sir Philip *Sidney (whom Carew had met at Oxford).

Park Honan

Carey, Elizabeth (d. 1635). She was the daughter of Elizabeth and Sir George Carey, and god-daughter of Lord Hunsdon, patron of the Chamberlain’s Men, and Elizabeth I. Carey’s marriage to Sir Thomas Berkeley on 19 February 1596 was possibly the occasion on which A Midsummer Night’s Dream was first performed.

Cathy Shrank

Caribbean. Rarely mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays, the Caribbean has been the site of some of the most exciting readings, adaptations, and appropriations of The Tempest.

The connections between The Tempest and the Caribbean have long been recognized, even if their significance has been disputed. One of the play’s accepted sources is William *Strachey’s account of the ‘wreck and redemption’ of a party of English colonists heading for Virginia who were shipwrecked on the islands of the Bermudas in 1609. This is at least a New World and even North Atlantic reference point, if not quite a Caribbean one. More tellingly, Caliban is usually regarded as an anagram of the word ‘can[n]ibal’, which has its root in the same indigenous word that also gives the term ‘Caribbean’. (See travel, trade, and colonialism).

When read from the Caribbean, the relationship between Prospero and Caliban has usually been seen as that between master and slave, the word by which Caliban is described in the play’s ‘Names of the Actors’, and the play therefore read as pertaining to the history of slavery. However, the uncertainty over Caliban’s parentage, provenance, and colour has allowed a considerable variation in the interpretations offered, even by those claiming to speak from Caliban’s position.

The three landmarks of the reading and adaptation of The Tempest from the Caribbean come from three different language traditions, those of Barbados, Martinique, and Cuba: George Lamming’s essay ‘A Monster, A Child, A Slave’, which appeared in his collection The Pleasures of Exile (1960); Aimé Césaire’s play Une tempête (1969); and Roberto Fernández Retamar’s essay ‘Calibán’, first published in the Havana journal Casa de las Américas in 1971.

Lamming refers to his own reading of The Tempest as ‘blasphemous’, conscious as he was both of the sacred status of Shakespeare, even in the twilight of British imperialism, and of the marginal status of a West Indian writer recently arrived in London. Ignored when it was first published, his insertion of the play into the history of the British slave trade, his probing questions about Prospero’s wife, and his openly disrespectful interrogation of Prospero’s psychological state subsequently became staple ingredients of the postcolonial approach to The Tempest. Lamming also insisted that the tide of colonial aftermath washes up on metropolitan shores, as it does with particular force in his novel Water with Berries (1971), in which a version of the Tempest story forms a violent colonial prehistory to the struggles of West Indian immigrants to make lives for themselves in London.

Césaire’s Une tempête offers a serious and complex involvement with the Shakespearian play, an ‘adaptation’ which keeps close enough to its original for the variations to be striking, and which also responds to Ernest Renan’s earlier continuation of the play, Caliban: Suite de ‘La Tempête’ (1878); although Césaire moves ‘back’ to the Caribbean (and back to Shakespeare) and therefore away from Renan’s concern with European politics. The main contexts for Une tempête were third-world and racial issues in the late 1960s: the extended confrontation between the coloured (mixed-race) Ariel and the black Caliban becomes as central to the play as the relationship between Prospero and Caliban.

The intertexts of Roberto Fernández Retamar’s 1970 essay ‘Calibán’ stretch back to the Uruguayan essayist José Enrique Rodó’s Ariel (1900), to which ‘Calibán’ is openly responding by placing the Caribbean, in the form of Cuba, at the centre of debates about Latin American cultural identity. Fernández Retamar’s defiant question was ‘what is our history, what is our culture, if not the history and culture of Caliban?’; a question which has continued to form a crucial part of the cultural-political agenda in Latin America.

Creative engagements with Shakespeare have similarly emphasized The Tempest. The Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite has often responded to the play, as have the Guyanese writers David Dabydeen and Pauline Melville. Marina Warner’s novel Indigo (1992) is largely set in the Caribbean and uses elements of the Tempest story and characters to tell a fictional version of the early history of English settlement in the area. In a striking variation, A Branch of the Blue Nile (1983), by Nobel laureate Derek Walcott, uses the Brechtian device of a group of Trinidadian actors rehearsing Antony and Cleopatra.

Shakespeare has been performed in the Caribbean at least since the later 17th century, with plays such as Hamlet, Macbeth, and Romeo and Juliet staged by travelling companies on the major islands. Jamaica, for example, where the best records survive, saw eight Shakespeare plays performed in 1781–2. Othello was not performed in the Caribbean until after Emancipation in 1834.

The end of the 20th century saw two Caribbean productions of Shakespeare visit the United Kingdom. In 1998 the Cuban company Teatro Buendía staged Otra tempestad at the reconstructed Globe (London). Otra tempestad goes further than other adaptations of The Tempest through its introduction of two new sets of characters, several from Shakespeare’s other plays as well as the orishas (Afro-Cuban deities) who double the European parts. Then Kit Hesketh-Harvey’s The Caribbean Tempest, equipped with new Caribbean music and spectacle but otherwise close to Shakespeare’s original, and first performed in Barbados, was staged in the Royal Botanic Gardens as part of the 1999 Edinburgh Festival.

Peter Hulme

Carlisle, Bishop of. One of Richard’s loyal supporters (Thomas Merke, d. 1409), he is spared by King Henry, Richard II 5.6.

Anne Button

Carlyle, Thomas (1795–1881), Scottish author of On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (1841). In his Hero as Poet he presents both Dante and Shakespeare (‘the greatest of Intellects’) struggling heroically to transcend constricting limitations, in Shakespeare’s case almost crushing his great soul to write for the Globe playhouse.

Tom Matheson

‘Carman’s Whistle’, the title of a ribald ballad, quoted by Falstaff in 2 Henry IV, quarto additional passage after 3.2.309; carmen or carters had a reputation for musical and sexual prowess. The ballad tune was set for *virginals by William *Byrd.

Jeremy Barlow

Carriers, two. They converse with each other, and briefly with Gadshill, in an inn yard, 1 Henry IV 2.1.

Anne Button

cartoon Shakespeare. See strip-cartoon Shakespeare.

Casca is the first of the conspirators to stab Caesar (following the account in *Plutarch), Julius Caesar 3.1.76.

Anne Button

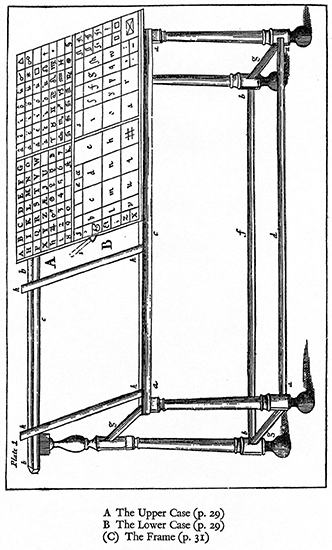

cases, large wooden trays divided into compartments used for sorting and storing type. Two cases, positioned one above the other on the *compositor’s frames, were traditionally employed in early English printing-houses. Capitals were placed in the boxes of the upper case, small letters in the boxes of the lower case. Even in the current age of computer-generated type fonts, capitals are still known as ‘upper case’, small letters as ‘lower case’.

A 17th-century type-case. From Joseph Moxon, Mechanical Exercises in the Whole Art of Printing (1683–4).

Eric Rasmussen

Cassandra is a Trojan prophetess and daughter of Priam in Troilus and Cressida (drawn originally from *Homer).

Anne Button

Cassio, Michael. Othello’s lieutenant, unwittingly involved in *Iago’s plot against Othello, he is injured, 5.1, but given governorship of Cyprus, 5.2.341.

Anne Button

Cassius, Caius. Instigator of the plot against Caesar, he commands his slave Pindarus to kill him when faced with military defeat, Julius Caesar 5.3.45.

Anne Button

Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Mario See Italy; opera.

Castiglione, Baldassare (1478–1529), Italian diplomat and writer whose prose work Il libro del cortegiano (The Book of the Courtier), published in an English translation by Sir Thomas Hoby in 1591, was a seminal text in the definition of Elizabethan chivalry and courtliness. Through a series of debates between various historical figures, Castiglione considered questions such as the ideal qualities of the courtier and his duty to the prince. The influence of the Courtier upon English Renaissance literature was one of both content and style. Not only did it inspire succeeding courtesy books, its witty exchanges may have influenced the courtship of Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

cast-off copy. In order to facilitate setting by *formes, a *compositor would attempt to calculate in advance how much of his *copy would be needed to fill each printed page (so that pages 1 and 4 of a *folio, for instance, could be set and sent to the press before pages 2 and 3). Compositors who made errors in their calculations would reach the end of their stints with too little or too much copy and be forced to fill out or contract the page using such expedients as setting *prose as verse or vice versa.

Eric Rasmussen

catch, a simple part-song or round, e.g. *‘Hold thy peace’ in Twelfth Night 2.3.66.

Jeremy Barlow

Catch my Soul. See musicals.

Catesby, Sir William. Drawn largely from *Holinshed, Catesby (d. 1485) is Richard’s ally throughout Richard III.

Anne Button

Catharine and Petruchio. David *Garrick’s three-act abbreviation of The Taming of the Shrew, first performed in 1754 and still in use in the 1880s, softens the play by insisting that Petruchio’s mistreatment of Kate and his servants is only a temporary pretence, but nonetheless reallocates most of her speech of wifely submission to him as a concluding sermon.

Michael Dobson

Catherine. (1) A lady attending the Princess of France, she is wooed by Dumain in Love’s Labour’s Lost. (2) She is wooed by King Harry, Henry V 5.2, and claimed as his bride as part of the peace treaty with France. She is based on Catherine of Valois, 1401–37, daughter of Charles VI of France, mother of Henry VI, and grandmother of Henry VII.

Anne Button

Catherine the Great (1729–96), Empress of all the Russias from 1762. A fluent and avid reader of Shakespeare, albeit in French translations, Catherine corresponded extensively on Shakespeare with *Voltaire, among others: in 1786 she translated The Merry Wives of Windsor into Russian, and wrote a play of her own, The Spendthrift, based on Timon of Athens. Another of her own plays, The Initial Instruction of Oleg (1791), is a professed imitation of Shakespeare’s style.

Michael Dobson

Catholicism. See religion.

Cato, Young. Son of Marcus Porcius Cato (95–46 bc), the younger Cato becomes Brutus’ ally and dies at Philippi, Julius Caesar 5.4.8.

Anne Button

Cattermole, Charles (1832–1900), English painter and illustrator. Amongst numerous 17th-century figure subjects, Cattermole, like his uncle George Cattermole, produced small-scale watercolours of Shakespearian scenes, with Macbeth a favoured theme of his stage-inspired compositions. He also executed a series of thirteen anecdotal watercolours illustrating Shakespeare’s life from Christening to Last Hours.

Kate Newman

Cawdor, Thane of. This title is given to Macbeth, Macbeth 1.2.63–5.

Anne Button

Caxton, William (1421–91), translator and the first English printer. Caxton worked in the Low Countries as an agent for silk merchants and came upon printing during a business trip to Cologne. On his return to England, he set up his own press and printed the first book in English, The Recuyell of the Histories of Troy, in 1475. He went on to print over 70 books including Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Troilus and Criseyde, Gower’s Confessio amantis, and Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. Shakespeare referred to The Recuyell, Caxton’s own translation of a French history by Le Fevre, in the writing of Troilus and Cressida.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

Cayatte, André (1909–89). He produced the colour film Les Amants de Vérone based on Romeo and Juliet in 1949 (script by the poet Jacques Prévert, music by Joseph Kosma). The highly talented cast plays the beautiful love story as a timeless adventure. The carefully chosen settings of Verona create an atmosphere of mystical painting.

Isabelle Schwartz-Gastine

Cecil, Robert (1563–1612), and his father William (1520–98), the most powerful ministers of their age. Comparisons between the Cecils and politic counsellors Nestor and Ulysses, who appear in Troilus and Cressida, were familiar from 1594. Secretary of State 1596–1608, Robert was one target of *Essex’s 1601 rebellion, to which Richard II is linked. Robert’s position as Sir William Brooke’s son-in-law may have induced William Cecil (Baron Burghley from 1571) to oblige Shakespeare to change Oldcastle’s name to Falstaff in 1 Henry IV. William B. Long suggests Burghley commissioned Sir Thomas More to tackle anti-alien sentiment.

Cathy Shrank

Celia, daughter of Duke Frederick and cousin of Rosalind in As You Like It, disguises herself as ‘Aliena’ (like Alinda in *Lodge’s Rosalynde) and marries Oliver.

Anne Button

censorship. The official government censor of drama in Shakespeare’s time was the Master of the Revels, to whom a playing company had to submit each playbook together with a fee. The censor’s remit was never precisely defined, but successive postholders took their responsibility to be the excision of material offensive to the Church and state, broadly interpreted to include not only sedition and personal satire but also foul language and excessive sexuality. If the Master of the Revels allowed the play, he would attach his licence (a signed statement of his approval) at the end of the manuscript. Often the licence would state conditions such as ‘may with the reformations [i.e. changes] be acted’ or ‘[with] all the oaths left out’. The office of the Master of the Revels was originally established to select plays for the entertainment of Queen Elizabeth, but in 1581 Edmund Tilney was given a new patent which required ‘all and every player or players…to present and recite before our said servant’ any new work. The volume of new plays made recitation by the actors impractical and Tilney was content to read the drama by himself. Tilney was succeeded by George *Buc (who was not, as formerly thought, his nephew) in 1610, and Buc was succeeded by John Astley in 1622, who was himself succeeded by Henry Herbert in 1623. Herbert kept the job until the closure of 1642 and managed to resume some of the same functions when the playhouses opened again in the Restoration. Herbert’s office book was extant until the 19th century and it provides most of what we know about the detailed operation of the censor, although it is rather later than Shakespeare’s working life. If the Master of the Revels was sufficiently unhappy about a play he might refuse even a conditional licence, but we have only one record of Herbert exacting the extreme penalty: ‘Received of Mr Kirke for a new play which I burnt for the ribaldry that was in it…£2.’

Not infrequently a play in performance at one of the London playhouses caused offence to an important person and the players were held to account. Thomas *Nashe and Ben *Jonson’s The Isle of Dogs (now lost) was highly critical of the government and its performance at the Swan resulted in a temporary closure of all the London playhouses. Presumably the Master of the Revels could have been held responsible if such a play had been licensed, and in 1633 the players tried to blame Herbert’s negligence for the offence caused by Jonson’s The Magnetic Lady, although the Court of Commission exonerated him. An entirely separate system of censorship governed the publication of plays. Getting ‘authority’ or ‘allowance’ was a prerequisite demanded of a stationer by a Star Chamber decree of 1586, and until 1606 the authority for playbook publication was in the hands of the Bishop of London and the Archbishop of Canterbury, who governed publication generally. Unlike the performance licence which was a strict necessity, failure to secure authority for printing seems to have been casually ignored unless someone was actually offended by the work. From 1606 George Buc, later to become Master of the Revels, took over the licensing of play publication. The ‘authority’ needed for publication should not be confused with licence for printing given by the *Stationers’ Company, the guild association for the printing trade. The Stationers’ Company regulations were designed to protect the individual interests of stationers, and in particular to prevent conflicts where more than one stationer wanted to print a given text, but in deciding whether or not to give the licence the company officers would also take into consideration whether the book had authority and whether it was likely to give offence. If they were unhappy, they might license the book on condition that it not be printed until ‘further’, ‘better’, or ‘lawful’ authority had been obtained.

On 27 May 1606 an *‘Act to Restrain Abuses of Players’ was passed which made it an offence to ‘jestingly or profanely speak or use the holy Name of God or of Christ Jesus, or of the Holy Ghost or of the Trinity’ in a stage play, on penalty of a £10 fine. As well as effectively censoring new works, this Act also required old plays to be expurgated if they were to be revived for the stage. The Act did not cover printing, however, and the 1623 Folio of Shakespeare contains a mixture of expurgated and unexpurgated plays according to the provenance of the manuscript underlying each of them. In many cases what looks like censorship of printed plays might be something else. The first, second, and third quartos of Shakespeare’s Richard II do not have the deposition scene which is present in the fourth and fifth quartos, and it is often assumed that the first three editions represent censorship of the potentially offensive scene. Much clearer evidence of censorship is the response of the lords *Cobham to what they perceived as satire of their ancestor Sir John *Oldcastle in Shakespeare’s 1 Henry IV. Shakespeare was forced to give Sir John a new surname, and he chose Falstaff for 2 Henry IV.

Scholars are not in agreement about how, or indeed whether, to undo changes apparently forced onto unwilling dramatists, and modern socio-cultural studies of the entire system of relations between the theatre industry, the monarchy, and the Parliament (such as Richard Dutton’s) find the Master of the Revels ‘as much a friend of the actors as their overlord’. For the opposite interpretation, summarized in her book’s title, see Janet Clare.

Gabriel Egan

Central Park. See United States of America.

ceramics. Amongst the spate of Shakespeare representations produced around the *Shakespeare Jubilee of 1769 were fanciful figurines of the dramatist and John *Milton made by the Derby factory c. 1765–70. Similar groups including Milton and Shakespeare were later produced in Chelsea and Bow porcelain. The production of Shakespeare ceramics increased in quantity, although not necessarily in quality, throughout the 19th century, when likenesses of the poet based on the two principal *portrait types appeared on items such as memorial plates, toby jugs, and the tops of walking sticks. The 19th century also gave rise to the growth of curious compounds involving Shakespeare portraits, such as Staffordshire figurines of c.1850, founded on *Scheemakers’s celebrated statue, but bearing the facial features and ermine cloak of Albert, Prince Consort. The production of Shakespeare-inspired ceramics declined during the 20th century. (See Shakespeariana).

Catherine Tite

‘Ceres’, the goddess of agriculture, is a part played by a spirit in The Tempest’s *masque of 4.1.

Anne Button

Cerimon, a physician of Ephesus, restores the apparently dead Thaisa, Pericles 12.

Anne Button

Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de (1547–1616), Spanish novelist, dramatist, and poet. His patriotic career included fighting at the battle of Lepanto (1571), and service as a government agent, before he turned to writing plays and romances. The first part of Don Quixote was published to immediate Spanish acclaim in 1605, though Cervantes also made many powerful enemies among those who feared Quixote was a lampoon of themselves. Part 2 was published in 1615. In the following year Cervantes died, within days of Shakespeare. Available in Thomas Shelton’s translation of 1612, Don Quixote also proved popular in England particularly with the dramatist John Fletcher. In 1625 Fletcher adapted Cervantes’ story La Señora Cornelia into the comedy The Chances. His reading of Don Quixote, particularly the inset story of Cardenio and Lucinda, may have inspired *Cardenio, a lost play, thought to have been a collaboration between Fletcher and Shakespeare.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

Césaire, Aimé (1913–2008), Martinican poet, playwright, and political leader; founder of the black French-language négritude movement. Une tempête (1969; A Tempest, 1986) is a postcolonial critique of Prospero’s brave new world as a sinister dictatorship, with Caliban as a black slave stirring revolt.

Tom Matheson

‘Cesario’ is the name used by Viola when disguised as a eunuch in Twelfth Night.

Michael Dobson

Challis Shakespeare. This paperback edition of individual plays began to appear in 1980 as the first designed specifically for the ‘student or non-specialist reader in Australia’. It offers a modernized text with brief notes and introductions. It was named after John Henry Challis, who died in 1880, and whose bequest made possible the foundation of a number of professorships at Sydney University.

R. A. Foakes

Chalmers, Alexander (1759–1834), a prolific editor and biographer, who produced a glossary to Shakespeare in 1797 and an attractive nine-volume edition of Shakespeare in 1805, illustrated by *Fuseli. Based on Steevens’s text it reprinted prefatory material by Pope, Johnson, and Malone, and included Chalmers’s own biography of Shakespeare.

Catherine Alexander

Chalmers, George (1742–1825), a Scottish historian and antiquarian who believed in the authenticity of William Henry Ireland’s forged Shakespeare-Papers (1795). On Ireland’s confession Chalmers first wrote an Apology for the Believers in the Shakespeare-Papers and subsequently justified his initial belief in the Supplementary Apology (1799). (See forgery).

Catherine Alexander

Chamber Accounts. The accounting records of the Treasurer of the Chamber who paid out for court entertainments. This is a major source of our knowledge concerning the professional players’ court performances.

Gabriel Egan

Chamberlain. He tells Gadshill that some wealthy travellers are about to set out, 1 Henry IV 2.1.

Anne Button

Chamberlain, John (1553–1627), scholar and letter-writer. After fire destroyed Shakespeare’s Globe in June 1613, the theatre was rebuilt. A letter which Chamberlain, a Londoner, sent to Alice Carleton establishes that the ‘new’ Globe, the ‘fairest’ playhouse ‘that ever was in England’, had opened its doors by 30 June 1614.

Park Honan

Chamberlain, Lord. See Lord Chamberlain.

Chamberlain’s Men/King’s Men. In May 1594 two privy counsellors, Henry Carey (the Lord Chamberlain) and Charles Howard (the Lord Admiral), established two acting companies, the Chamberlain’s Men and the Admiral’s Men, and gave them exclusive rights to perform in London at the Theatre and the Rose respectively. Shakespeare appears to have been one of the new Chamberlain’s Men from the company’s inception and his plays came with him, whether in his own possession or in the hands of fellow actors who performed in them for other companies we do not know.

The difficulty of distinguishing different plays on the same theme (there appears to have been more than one ‘Hamlet’ play in the 1590s) and of identifying single plays which might be known by more than one name (as might be the case with ‘The Taming of a/the Shrew’) makes the precise limits of the early Shakespeare canon uncertain. The nucleus of the company was composed of the actor-sharers George *Bryan, Richard *Burbage, John *Heminges, Will *Kemp, Augustine *Phillips, Thomas *Pope, William Shakespeare, and William *Sly. The distinctive John Sincler was not a sharer but his career can be traced through a number of Shakespeare’s ‘thin man’ roles including Nym and Slender in 2 Henry IV, Henry V, and The Merry Wives of Windsor, and Sir Andrew Aguecheek in Twelfth Night. In 1598 Francis *Meres praised Shakespeare’s The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Comedy of Errors, Love’s Labour’s Lost, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, Richard II, Richard III, Henry IV, King John, Titus Andronicus, and Romeo and Juliet. Together with Shakespeare’s Henry VI plays and The Taming of the Shrew this makes an impressive body of work and it is hardly surprising that the Chamberlain’s Men, with such a repertory and with a state-enforced monopoly on playing on the north side of the Thames, were hugely successful. On 22 July 1596 the company’s patron, Henry Carey the Lord Chamberlain, died and Lord Cobham was made Lord Chamberlain in his place. The patronage of the company passed to Henry Carey’s son George, so for a while the company was officially Lord Hunsdon’s Men, but in early 1597 Lord Cobham also died and George Carey received the chamberlainship, thus restoring the more impressive name to his players. Also early in 1597 died James Burbage, owner of the Theatre and the Blackfriars and father to the Chamberlain’s Men’s leading actor Richard Burbage. The lease on the land underneath the Theatre expired on 13 April 1597 and sometime before September 1598 the company must have started using another venue, presumably the nearby Curtain whose owner, Henry Lanham, made a profit-sharing deal with James Burbage in 1585. Unable to settle the dispute over the site of the Theatre and unable to move into the Blackfriars playhouse built by James Burbage in 1596, the Chamberlain’s Men dismantled the timbers of the Theatre and reassembled them on a new site on Bankside to form the Globe, which opened some time between June and September 1599. James Burbage’s sons Richard and Cuthbert inherited his Theatre and Blackfriars venues but had insufficient cash to finance the Globe project alone and so they formed a syndicate to bring in John Heminges, William Kemp, Augustine Phillips, Thomas Pope, and William Shakespeare. These actors became not only sharers in the playing company but also ‘housekeepers’ owning their own venue and this alignment of interests proved to be a powerful stabilizing force in the company’s fortunes. William Sly stayed out of the deal initially but took up Pope’s share after the latter’s death in 1603. Some time after 1596 one of the original Chamberlain’s Men sharers, George Bryan, dropped out and was probably replaced by Henry Condell, who became a ‘housekeeper’ too after Phillips died in 1605.

While the Globe was being erected in 1599 the clown William Kemp left the company and was replaced by Robert Armin, whose subtler style of humour seems to be reflected in Shakespeare’s subsequent creation of reflective intellectual ‘fools’. On 25 March 1603 Queen Elizabeth died and was succeeded by the King of Scotland, James VI, who became James I of England. The new monarch showed greater interest in drama than his predecessor and on 19 May 1603 he became the company’s patron, changing their name to the King’s Men. The following winter James demanded eight performances at court from his players, more than they had ever been asked for by Elizabeth. The company also began to tour more frequently and more widely under James’s patronage, which might indicate that the new King saw his playing company as a travelling advertisement for the new reign.

In 1608 the children’s company at Blackfriars disbanded temporarily after performing a play which offended James, and their manager Henry Evans surrendered his lease on the Blackfriars back to Richard Burbage. Now with royal patronage, the King’s Men were able to occupy the playhouse James Burbage had built just before his death. The shareholding arrangement at the Globe had apparently proved successful for the players because they now made the same arrangement to run the Blackfriars. The new syndicate formed on 9 August 1608 was comprised of Richard and Cuthbert Burbage, John Heminges, William Shakespeare, William Sly, Henry Condell, and an outsider named Thomas Evans. Plague closure probably prevented the company using the Blackfriars until late in 1609 and, assuming that they opened it with a new play by their resident dramatist, the first performance in their new home was either Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale or his Cymbeline. With two playhouses at their disposal, the King’s Men were able to use the Globe from May to September and, when the weather began to make outdoor performances uncomfortable, to move to the indoor Blackfriars for the winter. Outdoor performances had traditionally used no intervals but the tradition at the Blackfriars was to have a short break, a musical interlude, after each act. The King’s Men normalized their practices by introducing act-intervals at the Globe and by moving its music room from an unseen position inside the tiring house to the balcony in the back wall of the stage. The practicalities of staging differed in the company’s indoor and outdoor venues. Woodwind instruments are suitable indoors, brass outdoors, but more pressingly the small stage of the Blackfriars made swordfighting difficult. Despite this, and presumably because they had the ingrained touring habit of accommodating to whatever space is available, the company did not immediately develop different repertories for each playhouse.

Although the Blackfriars attracted an elite audience paying high prices, the Globe’s importance to the company is attested by their decision to rebuild it ‘in far fairer manner than before’, as Edmond Howes put it, after it burned down in 1613. Shakespeare retired around this time and was replaced by the partnership of Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher. Richard Burbage died in 1619 and was replaced by Joseph Taylor. A new patent was issued to the company on 27 March 1619, but only Heminges and Condell remained from the first patent of 1603. Heminges was by this time primarily an administrator for the company, and Condell seems to have stopped acting by the end of the 1610s. It was these two men who organized the publication of the first collected works of Shakespeare, the Folio of 1623. Playing the established masterpieces of Shakespeare and the new works of Beaumont and Fletcher, the King’s Men survived intact until the general theatrical closure of 1642.

Gabriel Egan

Chambers, Sir Edmund Kerchever (1866–1953), English civil servant and scholar. His thoroughly researched and documented Medieval Stage (2 vols., 1903), Elizabethan Stage (4 vols., 1923), and William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems (2 vols., 1930) are still unsurpassed as reference works, although necessarily supplemented by later investigations, including G. E. Bentley’s continuation and development of The Elizabethan Stage into the Jacobean and Caroline era, and Samuel *Schoenbaum’s documentary life of Shakespeare. After *Malone, in the 18th century, Chambers is the greatest modern researcher into original, official documents relating to dramatic history and biography, such as the records in the Patent Rolls, the Privy Council Register, the Lansdowne Manuscripts, and the Remembrancia of the City of London. Schoenbaum, his chief successor in biographical study, regarded Chambers’s article on Shakespeare for the 1911 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica as the most authoritative distillation of information about Shakespeare for the next 50 years, and claimed that his British Academy lecture on The Disintegration of Shakespeare (1924) effectively disposed for a generation of attempts to reassign passages and sometimes whole works by Shakespeare. The fact that Chambers’s logical precision and clarity of mind probably exceeded his critical sensibility cannot be regarded as a serious limitation.

Tom Matheson

Chancellor, Lord. See Lord Chancellor.

Chandos portrait, oil on canvas, 552×438 mm, National Portrait Gallery. This celebrated portrait, dated c.1610, is the only likeness of Shakespeare thought to have been executed before his death. Traditionally attributed to John Taylor, the complex attribution history of this portrait includes George Vertue’s claim that the work was painted by Richard Burbage, a celebrated actor and friend of the poet and dramatist. Vertue later made a modified notebook entry (see British Library Add. MSS, 21, 111) in which he names John Taylor as the producer of the work, information its owner (then Mr Robert Keck of the Temple, London) had gleaned from the actor Thomas Betterton, who had sold him the portrait. John Taylor (first recorded 1623, d. 1651) was identified by Mary Edmond as a Renter Warden of the Painter-Stainers’ Company. Taylor is recorded in the Court Minute Books of the company several times. The Chandos portrait was bequeathed to the collection which later became the National Portrait Gallery in 1856.

The Chandos portrait (formerly a possession of the Dukes of Chandos), the most convincing of all the paintings which have been identified as contemporary likenesses of Shakespeare. It was given to the National Portrait Gallery in 1856, where it is still catalogued as item number 1.

Catherine Tite

Changeling Boy. He is the cause of the quarrel between *Oberon and *Titania, described in A Midsummer Night’s Dream 2.1.18–31.

Anne Button

Chapel Lane Cottage. In 1602 Shakespeare acquired a copyhold from Walter Getley in a cottage with a garden of about a quarter of an acre (0.1 ha) in Chapel Lane, Stratford, across the road from New Place garden. On his death it passed to his daughter Susanna.

Stanley Wells

Chapel Royal, a part of the London royal household which existed to provide a children’s choir, and later an acting troupe, for court entertainments. There was also a Windsor Chapel with which the Chapel Royal appears to have merged in 1576 when Richard Farrant, in association with the Chapel Royal Master William Hunnis, installed the Chapel Children in the first Blackfriars playhouse.

Gabriel Egan

Chaplain. See Rutland’s Tutor.

Chapman, George (c. 1559–1634), poet and dramatist, now famous as the first translator of Homer into English, but in his time a highly successful playwright and a passionate advocate in verse of the dignity of the poet’s profession. His first poems, published as The Shadow of Night (1594), recommend the cultivation of obscurity in poetry (making it comprehensible only to select readers), and the establishment of an intellectual meritocracy capable of competing with the Elizabethan social order. For some scholars, this book identifies him as a member of an exclusive group of intellectuals who surrounded Sir Walter *Ralegh. In 1592 the group was dubbed the ‘school of atheism’ by a querulous pamphleteer. One theory, now discredited, holds that Love’s Labour’s Lost (c.1594) is an attack on the Ralegh circle, and that Shakespeare alludes to this ‘school of atheism’ as the ‘school of night’ (4.3.251), with The Shadow of Night as its poetic manifesto. This theory also proposes that Chapman was the rival poet referred to in Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Chapman’s second book, Ovid’s Banquet of Senses (1595), burlesques the genre of the erotic narrative poem popularized by Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis (1593). Its obscurity makes it less approachable than his second contribution to the genre, a pensive continuation of *Marlowe’s unfinished Hero and Leander (1598). Chapman’s translation of Seven Books of Homer’s Iliad (1598) transformed Homer’s heroes into Elizabethan soldiers and politicians, and helped Shakespeare do the same in Troilus and Cressida (1601–2). His best-known comedy is All Fools (1599), his most celebrated tragedy the extravagant Bussy D’Ambois (1604). Shakespeare may have modelled his late tragic heroes on the heroes of Chapman’s tragedies.

Robert Maslen

Chapuys, Eustace. See Caputius, Lord.

Charlecote. See Lucy, Sir Thomas.

Charles, Duke Frederick’s servant, is defeated in a wrestling match by Orlando, As You Like It 1.2.204.

Anne Button

Charles, Dauphin of France. He agrees to be viceroy of his dominions subject to King Henry VI after having been captured by the English, 1 Henry VI 5.7.

Anne Button

Charles I (1600–49), King of England (reigned 1625–49). In his youth he was in the shadow of his outgoing and charismatic elder brother *Henry, whose unexpected death in 1612 placed him in a position he was poorly equipped by either nature or training to fill. His father made no secret of his disappointment in his second son, and publicly declared his preference for the favourite Buckingham. Nevertheless, and despite numerous quarrels, Buckingham became Charles’s closest adviser. Together they travelled to Spain in 1623 to negotiate—unsuccessfully—a Spanish match, and his subsequent marriage in 1625, shortly after his father’s death, to the French Catholic princess Henrietta *Maria, fulfilled James’s great hope of an ecumenical alliance.

Charles was a quiet and intellectual man, shy to the point of prudishness, and instituted radical reforms in the court, the most visible having to do with decorum and his own privacy. He was a passionate connoisseur of all the arts, and amassed one of the greatest collections of paintings in Europe. Both he and his wife loved theatre, and Charles took an active interest in the management of the public stage, in 1634 even overruling Sir Henry Herbert on a question of censoring oaths in *Davenant’s The Wits. During the 1630s, the decade of prerogative rule when Charles undertook to reinvent both the nation and the monarchy, the masque and drama too underwent significant developments through royal patronage. Inigo Jones’s stage machinery was greatly refined and elaborated for productions at Whitehall, and perspective settings were for the first time regularly employed for drama. Few of the plays at the Caroline court were by Shakespeare; but among all the Shirley, *Beaumont and *Fletcher, *Massinger, Brome, Strode, Davenant, Townshend, and Suckling the King and Queen saw Richard III, The Taming of the Shrew, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, Hamlet, and Julius Caesar. Charles’s copy of the Second Folio, now at Windsor Castle, includes annotations in his own handwriting, one of them retitling Much Ado About Nothing as ‘Beatrice and Benedict’.