p

Pacino, Al. See Richard III; United States of America.

Pacorus, son of Orodes I, King of Parthia, invaded Syria unsuccessfully, dying in battle 38 bc. His body is paraded in triumph by Ventidius, Antony and Cleopatra 3.1.

Anne Button

Padua, in the north of Italy, was a famous university town and a centre of art and literature in the Middle Ages. It is the scene of much of The Taming of the Shrew.

Anne Button

Page, Anne. In The Merry Wives of Windsor she elopes with Fenton, but is forgiven by her mother and father, who had intended her for Caius and Slender respectively.

Anne Button

Page, Master (George). Father of Anne and William, he rejects Nim’s information that Falstaff is pursuing his wife, The Merry Wives of Windsor 2.1, and advises Ford to do the same.

Anne Button

Page, Mistress Margaret. See Ford, Mistress Alice.

Page, William. Younger brother of Anne Page, his Latin grammar is tested by Sir Hugh Evans, The Merry Wives of Windsor 4.1.

pageants. Professional players were hired to perform in public events celebrating the installation of officials such as the lord mayor of London. On 31 May 1610 the investiture of Prince *Henry as Prince of Wales was celebrated with a sea-pageant on the Thames in which Richard *Burbage and John *Rice performed as tritons. In recompense, Burbage and Rice were allowed to keep their costumes which probably were reused for *Caliban and *Ariel-as-sea-nymph in The Tempest.

Gabriel Egan

pages. (1) Taming of the Shrew. See Bartholomew. (2) In Richard III a page is sent to fetch Tyrrell, 4.2. (3) Love’s Labour’s Lost. See Mote. (4) Mercutio’s Page is sent to fetch a surgeon, Romeo and Juliet 3.1.94. Paris’s Page alerts the watch, Romeo and Juliet 5.3. (5) The Merry Wives of Windsor. See Robin. (6) Falstaff has a page in 2 Henry IV, possibly the same person as Robin and the Boy in The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry V respectively. (7) Two pages sing *‘It was a lover and his lass’ to Touchstone and Audrey, As You Like It 5.3. (8) A page summons Paroles, All’s Well That Ends Well 1.1.183. (9) A page banters with Apemantus, Timon of Athens 2.2. (10) A page attends Gardiner, All Is True (Henry VIII) 5.1.

Anne Button

Painter. (1) He and a Poet present their work to Timon, Timon of Athens 1.1; they are reviled by him in the woods, 5.1. (2) The Painter, Bazardo, visits Hieronimo to beg for justice for his murdered son in the Fourth Addition to the 1602 text of The Spanish Tragedy, a passage inconclusively attributed to Shakespeare.

Anne Button, rev. Will Sharpe

Painter, William (c. 1540–94), schoolmaster, fraudulent clerk at the Tower of London, translator. Painter’s Palace of Pleasure (1566–7) is a collection of prose tales, mainly from *Boccaccio, *Bandello, and *Cinthio, in Painter’s own English translations. As a repository of plot material, it may have been a particular favourite of Shakespeare’s: the outlines of The Rape of Lucrece, Romeo and Juliet, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Timon of Athens, and All’s Well That Ends Well are all found in these volumes. Painter translated with such conscientiousness that he made few alterations to his sources, though he may have been responsible for the protagonist’s name in Romeo and Juliet being Romeo, not Romeus as in *Brooke.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

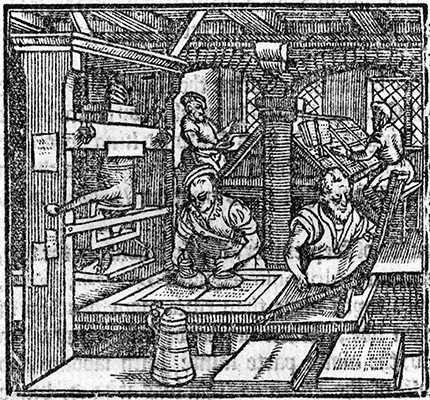

painting. Although illustrators had been providing frontispieces to the plays since *Rowe’s edition of 1709, the first depictions on canvas of scenes from Shakespeare belong to the 1730s, when British artists such as *Hogarth identified these as a properly native subject matter at a time of increasing cultural nationalism. As the century progressed the search for sublime and national-historical subjects brought painters repeatedly to the great tragedies, especially King Lear, depicted, for example, in Francis *Hayman’s decorations for Vauxhall Gardens (1741), James *Barry’s Lear Weeping over the Body of the Dead Cordelia (1786–8, now in the Tate Gallery), and the early drawings of William *Blake. *Fuseli, meanwhile, found inspiration in the live theatre (returning repeatedly, for example, to compositions derived from actors’ movements in Macbeth), and in the supernatural characters of the tragedies and comedies alike. Art and politics were again compounded in the opening of *Boydell’s Shakespeare *Gallery in 1789, which appealed to national sentiment as Britain prepared for war with revolutionary France. Paradoxically, it was the collapse of the print trade with France that also contributed to the gallery’s sale in 1803.

Later in the 19th century, scenes from plays by Shakespeare set in Italy and in historically distant eras provided material that met the artistic agenda of the *Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who aspired to pre-industrial standards of artistic production, while less idealistic history painters mined the Roman plays for subjects of classical violence and voluptuousness. The 20th century’s preference for abstraction, however, led to the virtual disappearance of Shakespearian scenes as a subject for major painters, and despite some noteworthy commissioned portraits of actors in Shakespearian roles (such as those held in the *RSC Collection in Stratford) it is hard to imagine the plays being rediscovered as such in the age of Damien Hirst.

Catherine Tite

Palamon, Arcite’s rival for Emilia, is to marry her at the end of The Two Noble Kinsmen.

Anne Button

Palestine. During the two last decades of the 20th century, Palestinian theatre has experienced a modest revival within the *Arab world. In 1994, in East Jerusalem, the Palestinian company Al Kasaba, set up by Georges Ibrahim, played Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. The producers were the Israeli Eran Baniel and the Palestinian Fouad Awad. The Capulets were played by *Israelis in Hebrew, and their rivals, the Montagues, by Palestinians in Arabic. The intention behind this original treatment was expressed by Ibrahim himself in 2003 to a French journalist: ‘Pour que Palestiniens et Israéliens puissent se connaître autrement qu’à travers l’armée et l’Intifada’ (‘To enable Palestinians and Israelis to know one another through another way than the army and the Intifada’) (Le Monde, 22 June 1994). During the 2012 *Globe to Globe Festival, the Ashtar Theatre Company, based in the Palestinian town of Ramallah, presented Richard II at the London Globe. The text was an Egyptian word-by-word translation of the Shakespearian play, re-interpreted into modern classical Arabic by the Palestinian poet Ghassan Zaqtan. The play is about a malevolent tyrant, overthrown by popular uprising. It opens with a dumb show of a horrible murder followed by the entrance of King Richard II, dressed in a military uniform.

Rafik Darragi

Palladio, Andrea (1508–80), Italian architect, builder of the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza in 1583. Palladio’s neoclassical designs were based on principles of harmonious proportion derived from mathematical ratios, especially 1:2, 3:4, 2:3, and 3:5. Inigo *Jones’s absorption of Palladian principles is evidenced in his Whitehall Banqueting House of 1622 and the Cockpit-at-Court playhouse conversion of 1629.

Gabriel Egan

Palmer, John, actors: ‘Gentleman’ Palmer (1728–68) made his Drury Lane debut in the 1748–9 season playing Graziano, Lennox, and Cassio. At his illness and death his roles were inherited by ‘Plausible Jack’ Palmer (1744–98, no relation) who, after an indifferent career to that point, became one of the most versatile actors and best comedians of his day with successes as Falstaff, Sir Toby Belch, and Henry VIII.

Catherine Alexander

Pandarus. Owing much more to *Chaucer’s version of the character than *Homer’s Greek hero, he is the uncle of Cressida and intermediary between her and Troilus in Troilus and Cressida.

Anne Button

Pander. Sometimes given the proper name ‘Pandar’, he owns the brothel in Pericles.

Anne Button

Pandolf, Cardinal. He is a papal legate who excommunicates John, King John 3.1, forcing King Philip of France to end his new alliance. (He is ‘Pandolph’ or ‘Pandulpho’ in the *First Folio and ‘Pandulph’ in *Holinshed.)

Anne Button

Panthino. The servant of Antonio, he advises him to send Proteus to the Emperor’s court, The Two Gentlemen of Verona 1.3.

Anne Button

paradox, an expression that is or appears puzzlingly self-contradictory: ‘the truest poetry is the most feigning’ (As You Like It 3.3.16–17).

Chris Baldick

parallel texts. Several of Shakespeare’s plays, including Hamlet and King Lear, survive in two or more early versions. Editors since the 19th century have often printed the textual versions in parallel columns in order to facilitate study and analysis of their differences.

Eric Rasmussen

‘Pardon, goddess of the night’, sung, probably by a musician or musicians (the text is unclear), in Much Ado About Nothing 5.3.12. The original music is unknown.

Jeremy Barlow

Paris. One of Priam’s sons in Troilus and Cressida, he is wounded by Menelaus (mentioned 1.1.110), whose wife Helen he has abducted. They fight again, 5.8.

Anne Button

Paris, County. Intended by Capulet for Juliet, he bitterly laments her supposed death, Romeo and Juliet 4.4.68–73. He is slain by Romeo, 5.3.73.

Anne Button

Paris Garden. See animal shows; theatres, Elizabethan and Jacobean.

parison, parallelism of construction in successive clauses or lines:

My manors, rents, revenues, I forgo;

My acts, decrees, and statutes I deny

(Richard II 4.1.212–13)

Chris Baldick

parley, a *trumpet signal indicating a meeting between opposing parties, or a ceasing of hostilities (e.g. 1 Henry IV 4.3.31).

Jeremy Barlow

Parnassus plays, the collective name for three anonymous plays, The Pilgrimage to Parnassus, The First Part of the Return from Parnassus, and The Second Part of the Return from Parnassus, written between 1598 and 1602 and performed at St John’s College, Cambridge. The theme is several young scholars’ attempts to find occupations, and in the final part two of them try to join the *Chamberlain’s Men. During their audition, William *Kempe disparages university plays and university men, in particular *Jonson, to whom Shakespeare has given ‘a purge that made him beray his credit’, which suggests that Shakespeare too indulged in personal satire. In First Part of the Return from Parnassus are disparaging allusions to Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

Gabriel Egan

Paroles, a cowardly braggart who falls victim to the conspiracy of his comrades in All’s Well That Ends Well.

Anne Button

Parry, Sir Hubert (1848–1918), English composer. He set a large number of Shakespeare’s songs and sonnets, either as solo songs or as partsongs. Many were published in his twelve-volume collection English Lyrics (1885–1920) or in A Garland of Shakespearian and Other Old Fashioned Songs, Op. 21 (1874).

Irena Cholij

parts. Players of Shakespeare’s time were not given the entire script of a play to rehearse, but only their ‘part’ or ‘side’ written out with cues indicating when to commence a speech (cf. A Midsummer Night’s Dream 3.1.92–5). The only extant ‘part’ is for Edward *Alleyn’s title role in Robert *Greene’s Orlando furioso, in the form of a scroll over 17 feet (5 m) long.

Gabriel Egan

Pasco, Richard (1926–2014), British actor. Having won attention as Berowne, Henry V, Angelo, and Hamlet at the Bristol Old Vic, he went on to play leading parts for the *Royal Shakespeare Company, notably both Richard II and Bolingbroke (alternating with Ian *Richardson) in 1973 and Timon of Athens in 1980.

Michael Jamieson

passamezzo (passy-measures), a livelier version of the *pavan; also chord sequences, associated originally with the dance, which formed the basis for many popular song and dance tunes throughout Europe from the late 16th century onwards: *‘Greensleeves’ is based on the minor or Dorian mode passamezzo antico. The eight-bar phrase structure may explain Sir Toby (Twelfth Night, 5.1.198) calling the drunk surgeon (whose eyes are set at ‘eight i’th’ morning’) a ‘passy-measures pavan’.

Jeremy Barlow

Passionate Pilgrim, The, a collection, ascribed to Shakespeare, of 20 short poems, mostly amorous, some of them mildly erotic, published in 1599 by William *Jaggard. The first edition survives only in part of one copy; the second followed in the same year. It opens with versions of two of Shakespeare’s Sonnets (138 and 144), perhaps in order to capitalize on Francis *Meres’s reference, in the previous year, to Shakespeare’s ‘sugared sonnets among his private friends’. The remaining poems include three extracts from Love’s Labour’s Lost along with several other short poems known to be by writers other than Shakespeare: two by Richard *Barnfield, one by Bartholomew Griffin, a version of *Marlowe’s ‘Come live with me and be my love’, and the last stanza of the reply to that poem attributed to Sir Walter *Ralegh. For no clear reason, the first fourteen poems are followed by a second title page promising ‘Sonnets to Several Notes of Music’. The eleven poems not definitely known to be by writers other than Shakespeare are included in the Oxford edition, with a statement that the ascription is very doubtful.

A third edition, of 1612, adds poems from Thomas *Heywood’s Troia Britannica (1609). In his Apology for Actors, published in the same year, Heywood protested against the ‘manifest injury’ of printing writings by him ‘in a less volume, under the name of another, which may put the world in opinion I might steal them from him’. Acknowledging his lines unworthy of Shakespeare, Heywood declared ‘the author’—i.e. Shakespeare—‘much offended with Master Jaggard that, altogether unknown to him, presumed to make bold with his name’. Probably as a result, the original title page was cancelled and replaced with one that did not mention Shakespeare.

Stanley Wells

passy-measures. See passamezzo.

Pasternak, Boris (1890–1960), Russian novelist, poet, and translator. Unable to publish his own poetry under the tyrant Stalin, he became the official translator of Shakespeare into Russian. His Gamlet (Hamlet) and Korol Lir (King Lear) were used in films by *Kozintsev. A poem linking Hamlet and Christ is the first of the hero’s poems printed at the end of his banned novel Doctor Zhivago (1958).

Tom Matheson

pastoral, a kind of imaginative literature taking its characters and settings from an idealized conception of the unhurried life of shepherds and shepherdesses. In prose or verse, in drama or lyric, it provides an escapist picture of rural tranquillity and idleness in which actual sheep-tending is displaced by amorous conversation and song, and real shepherds by noble exiles from the corruptions of city and court. Paradoxically a sophisticated literary treatment of imagined simplicity, this tradition originated in ancient Greek and Latin poetry—the Idylls of Theocritus, the Eclogues of *Virgil—and was revived in 16th-century Italy, notably by Sannazzaro, Tasso, and Guarini. English pastoral was inaugurated by *Spenser’s verse eclogues in The Shepheardes Calendar (1579) and further developed in The Arcadia (1590), a prose romance by *Sidney. Shakespeare’s use of pastoral conventions, which can include an element of apparently ‘anti-pastoral’ realism about country matters, is most evident in As You Like It and The Winter’s Tale, and fainter echoes of them can be felt in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Love’s Labour’s Lost. For these works he drew upon contemporary English pastoral romances, notably *Greene’s Pandosto (1588) and *Lodge’s Rosalynde (1590).

Chris Baldick

Pater, Walter Horatio (1839–94), English academic, influential in the fin de siècle aesthetic movement with Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) and Marius the Epicurean (1885). Essays on Measure for Measure (1874), Love’s Labour’s Lost (1878), and Shakespeare’s English Kings were collected in Appreciations (1889).

Tom Matheson

pathetic fallacy, a mild form of poetic personification in which human motives are attributed to inanimate nature or non-human creatures (e.g. ‘the scolding winds’, Julius Caesar 1.3.5). John Ruskin, who coined the term, commended Shakespeare for his sparing use of such metaphors, by comparison with later ‘morbid’ poets.

Chris Baldick

Patience, Katherine’s waiting woman, attends her All Is True (Henry VIII) 4.2.

Anne Button

Paton, Sir (Joseph) Noel (1821–1901), Scottish painter and illustrator. Paton earned recognition for himself and the proliferating genre of *fairy painting with The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania, winning a prize in the high-profile 1847 Westminster Hall competition. Characterized by a profusion of minutely observed detail, The Reconciliation and its pendant The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania (1849) teem with encounters between naked fairies—generating sexual undertones absent from his later Oberon and the Mermaid (1883). Paton illustrated Shakespeare’s plays throughout his career: from The Tempest (Chapman & Hall, 1845) through to William Mackenzie’s The National Shakespeare (1888–9).

Kate Newman

Patroclus, based on *Homer’s character of the same name, is killed by the Trojans (his body is produced, Troilus and Cressida 5.5.16), spurring his friend Achilles back into action.

Anne Button

patronage, in a Renaissance literary context, the social convention by which authors (and acting companies (see companies, playing)) would receive protection, support, or subsidy from wealthy individuals, families, or institutions, in return for furthering their reputations, either simply by associating them with their work or by actively praising them in it (in flattering dedications, if nowhere else). More broadly, ‘patronage’ is a term for the entire pyramid-shaped social structure by which a network of mutual favours and obligations extended from the monarch downwards through the aristocracy and beyond.

Until well into the 18th century, most writers seeking to publish works with any literary pretensions at all both needed and sought patronage: Shakespeare was no exception, dedicating his narrative poems to the Earl of *Southampton and later, according to the dedication of the First Folio, attracting the benign attention of the Earls of *Pembroke. The development of the commercial theatre, however, could offer writers an alternative source of income—albeit a meagre and precarious one if, as most did, they remained freelance. Although the Lord *Chamberlain’s Men of course depended collectively on the patronage of the Lord Chamberlain, Shakespeare was from the mid-1590s onwards—as a shareholder in the theatre company for which he wrote—more independent of individual patronage than were many of his literary contemporaries.

The Shakespeare canon abounds in depictions of patron–client relations, both artistic—as in Timon’s dealings with the Poet and the Painter in Timon of Athens—and more general—as in the relationship between Antonio and Bassanio in The Merchant of Venice. As this latter example may suggest, the terms in which a client solicits the favours of a patron, and those by which a patron promises favours, can be close to the language of love, and some have detected an erotic dimension to Shakespeare’s own dealings with Southampton on the strength of the dedications to Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

Michael Dobson

Paulina, Antigonus’ wife in The Winter’s Tale, defends Hermione in spite of Leontes’ anger in Acts 2 and 3. She reunites them, and, long since bereaved of Antigonus, agrees to marry Camillo, 5.3.

Anne Button

pavan, a sedate dance in common time performed by one couple or in procession; it went out of fashion during Shakespeare’s lifetime. Musically it was often succeeded by the livelier *galliard.

Jeremy Barlow

Pavier, Thomas. See quartos.

Payton, John (fl. 1760–1800), a Stratford alderman who lived in Shottery. A street in modern Stratford is named after him. The master bricklayer Joseph Mosely, who found the document known as the Spiritual Last Will and Testament of John *Shakespeare in the *Birthplace in 1757, later gave it to Payton, who around 1789 sent it to *Malone, who printed it in 1790. In the interim John *Jordan had tried unsuccessfully to publish a copy in the Gentleman’s Magazine.

Stanley Wells

Peacham, Henry (?1576–?1643), author and artist. His Truth of our Times (1638) contains an account of *Tarlton playing when Peacham was a London schoolboy; his Complete Gentleman (1622) provides insight into London playgoing. A sketch of Titus Andronicus with an extended quotation (c.1595) is attributed to Peacham: see Longleat manuscript.

Cathy Shrank

Peaseblossom is one of Titania’s fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Anne Button

Pedant. He is a travelling schoolmaster whom Tranio persuades to impersonate Vincentio in The Taming of the Shrew 4.2.

Anne Button

Pedro, Don. He arranges the betrothal of Claudio to Hero, but becomes convinced of her infidelity, in Much Ado About Nothing.

Anne Button

Peele, George (1556–96), playwright and poet. After attending Christ Church, Oxford, he wrote a series of plays and entertainments which helped revolutionize the theatrical use of verse. His best-known plays are The Arraignment of Paris (1584) and The Old Wives Tale (1595). The first is a pastoral play—one of the earliest in English—which ends with *Elizabeth I being offered a golden apple by the goddess Diana; the second is a cheerful adaptation of various motifs from folk tale and romance. He also wrote two energetic history plays and a melodious biblical drama, David and Bethsabe (1599), and is now generally accepted as the author of the first act of Titus Andronicus.

Robert Maslen

‘Peg a Ramsay’, the title of a popular dance and ballad tune, quoted by Sir Toby in Twelfth Night 2.3.73.

Jeremy Barlow

Pelican Shakespeare. This paperback edition, designed for an American market, was produced between 1956 and 1967. Shakespeare’s works were separately edited by noted scholars under the general guidance of Alfred Harbage. He emphasized the flow of action in the plays by omitting scene locations and relegating act and scene divisions to the margins. With very brief introductions and light glossing at the foot of the page, the volumes offered attractively presented texts at an initial price, in the USA, of 65c: in many respects they resembled the *Penguin and New Penguin editions. The Pelican series was revived in 1999 under the general editorship of A. L. Braunmuller and Stephen Orgel.

R. A. Foakes

Pembroke, Earl of. (1) Edward IV orders Pembroke and Lord Stafford (both mute) to ‘prepare for war’ against Henry, Richard Duke of York (3 Henry VI) 4.1.127–8. (2) He vows revenge for Arthur’s death, King John 4.3, and joins the French, but returns to John in time to see him die.

Anne Button

Pembroke, Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of. See Pembroke’s Men.

Pembroke, Mary Herbert, Countess of (1561–1621), third wife to Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, and sister of Philip *Sidney. A patroness of poets, including Ben *Jonson, Herbert initiated courtly interest in *Seneca, translating Garnier’s Marc Antonie (1592), echoes of which occur in Antony and Cleopatra. Dover *Wilson speculates that Herbert commissioned Shakespeare’s first seventeen sonnets.

Cathy Shrank

Pembroke, Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of (1584–1650), younger son of Henry and Mary Herbert. Possibly called Philip after his uncle Philip *Sidney, he was a munificent patron and lifelong benefactor of the artist Van Dyck and playwright Philip *Massinger. John *Heminges and Henry *Condell, joint editors of Shakespeare’s posthumous *First Folio in 1623, dedicated the work to Philip and his brother William. The dedicatory epistle to this ‘incomparable pair of brethren’ is testimony to an established connection between Shakespeare and the Herberts, and their long-standing generosity towards the playwright, noted in the dedication as their ‘servant Shakespeare’. As Heminges and Condell wrote, ‘your [lordships] have been pleased to think these trifles something heretofore, and have prosecuted both them and their author living, with so much favour [that…] the Volume asked to be yours’.

Philip was known for his hasty temper, and was frequently embroiled in brawls at court, including a quarrel with Shakespeare’s patron, the Earl of *Southampton, over a game of tennis in 1610. Despite this, Philip remained a firm favourite of *James I, becoming gentleman of the bedchamber in 1605, and retaining the position until James’s death in 1625—continued favour that owed much to the comeliness of his person, and his passion for *hunting and field sports.

Philip married Susan Vere, daughter of the 17th Earl of Oxford, in 1604, and was created Earl of Montgomery in 1605, succeeding his brother William as Earl of Pembroke in 1630.

Cathy Shrank

Pembroke, William Herbert, 3rd Earl of (1580–1630), eldest son of Henry and Mary Herbert, educated by the poet Samuel *Daniel. Like his brother Philip, co-dedicatee of Shakespeare’s *First Folio (1623), William was an enthusiastic patron of the arts. His beneficiaries included Ben *Jonson, Philip *Massinger, and Inigo *Jones. John *Aubrey remembers William as ‘the greatest Maecenas to learned men of any peer of his time or since’, and according to Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, his liberality exceeded both his own considerable fortune, and that of his wife Mary Talbolt.

William was disgraced, and imprisoned briefly in 1601, for an affair with Mary Fitton, believed by some to be Shakespeare’s *Dark Lady. Despite getting Fitton pregnant, William refused to marry her, making her at least the fourth well-born woman he had declined to wed—the previous three being Elizabeth *Carey (1595); Bridget Vere, Lord Burghley’s granddaughter and daughter of the 17th Earl of Oxford (1597); and a niece of Charles Howard, Earl of Nottingham (1599).

Dover *Wilson conjectures that William’s reluctance to marry induced his mother Mary to commission Shakespeare to write seventeen sonnets advocating marriage to mark William’s 17th birthday in 1597 (Sonnets 1–17). This identification of William Herbert as *‘Mr W.H.’, to whom the publisher Thomas Thorpe dedicated the Sonnets in 1609, was first floated by James Boaden in 1837.

Supporters of William Herbert as ‘W.H.’ find further evidence in Francis Davison’s Poeticall Rhapsody (1602), in which Davison celebrates William’s ‘lovely…shape’. Another suggestive allusion is Thorpe’s reference to himself as ‘the Well-wishing Adventurer’, which may celebrate William’s incorporation as a member of the King’s Virginia Company in 1609. This connection with the Virginia Company may have allowed Shakespeare access to unpublished accounts of the wreck of the Sea-Adventure in 1609, an incident on which he based The Tempest, especially William *Strachey’s Reportary, later published in Samuel Purchas’s Pilgrims (1625).

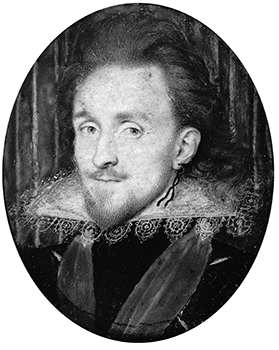

William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, by Isaac Oliver, certainly an important patron of Shakespeare (and as such a co-dedicatee of the First Folio), and possibly the ‘Mr W.H.’ of the Sonnets.

Cathy Shrank

Pembroke’s Men, an obscure playing company, under the patronage of Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (?1534–1601), known mostly from the title pages of their plays. Their The Taming of a Shrew has some relation to Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, their Richard Duke of York is a memorial reconstruction of the play printed as 3 Henry VI in the Shakespeare Folio of 1623, and their Titus Andronicus is Shakespeare’s. It seems likely that Shakespeare was one of Pembroke’s Men before he, and several of the others, joined the *Chamberlain’s Men in 1594. Other Pembroke’s Men were John *Sincler, Gabriel *Spencer, Robert Shaw, and possibly Richard *Burbage. The company probably played at the *Theatre in 1592–3 and broke in 1594, to be reformed in 1597 for a brief season at Langley’s *Swan playhouse before their production of The Isle of Dogs caused that playhouse’s closure. The company survived Ben *Jonson’s murder of Gabriel Spencer in 1598, occupying the *Rose after the Admiral’s Men left it for the Fortune in 1600, only to break forever with the death of their patron on 9 January 1601.

Gabriel Egan

Penguin Shakespeare. Penguin Books began a revolution in publishing with their sixpenny pocket paperbacks, and included in their early lists an edition of Shakespeare. The first six titles appeared in 1937, attractively printed, with a plain text uncluttered by scene locations, a very brief introduction, and some notes and a short glossary at the end. The editor, G. B. Harrison, preferred Folio texts as closer to what he supposed was acted, but included in brackets passages found only in quartos. The series was superseded by the New Penguin Shakespeare (1967– ), which retained the plain text format, but gave individual editors of the various works freedom to determine the text in the light of current scholarship. This new edition also provided much more substantial critical introductions, extensive commentaries, and accounts of textual problems. The general editor, T. J. B. Spencer, soon brought in Stanley Wells as his associate editor. In the plays the scenes are numbered in the margins, so that the stage directions and text seem to run on from one scene to the next. Both series have been very popular, and the New Penguin Shakespeare have been much used by schools, and also by acting companies. From 2005–8 the series was updated under the general editorship of Stanley Wells, largely retaining the texts and commentaries of the previous editions, with new introductory material commissioned from a wide range of contemporary Shakespeare scholars, and added sections on each play in performance for the first time in the series’ history.

R. A. Foakes, rev. Will Sharpe

Pennington, Michael (b. 1943), British actor, renowned for his grace of movement and mellifluous speaking of verse. Having acted at Cambridge, he played Angelo, Berowne, and Hamlet with the *Royal Shakespeare Company, 1974–81. He co-founded with Michael *Bogdanov the *English Shakespeare Company and toured worldwide in their popular seven-play Wars of the Roses (1986–9), later videotaped. He rejoined the RSC in 1999 to play Timon of Athens, directed by Gregory *Doran. The two worked together again on both the RSC’s 2004 marionette production of Venus and Adonis, which Pennington narrated, and the 2013 Richard II, in which he played John of Gaunt to David *Tennant’s Richard. He has authored A User’s Guide titles on Hamlet, Twelfth Night, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, as well as a memoir of his 20,000 hours performing, directing, and writing about Shakespeare, Sweet William.

Michael Jamieson

pentameter, a verse line of five feet. Although there are other kinds (such as anapaestic pentameter, occasionally used by Browning), the most important form of pentameter is iambic. In English, iambic pentameter (five predominantly iambic feet) is the standard metre of blank verse, heroic couplets, sonnets, and rhyme royal.

Chris Baldick/George T. Wright

Pepys, Samuel (1633–1703), diarist. He began writing his Diary in 1660 when a civil servant in the Naval Office and continued the record, in cipher and shorthand, until 1669 when his eyesight began to fail. Among much else, it provides a remarkable account of the social experience of theatre-going and of the *Restoration theatre’s innovations (particularly the introduction of actresses, Shakespearian *adaptations, and the development of stage effects), in addition to commenting on performers and performances. For example, he records visits to Macbeth (in *Davenant’s adaptation): ‘From hence to the Duke’s house, and there saw “Macbeth” most excellently acted, and a most excellent play for variety’ (28 December 1666); ‘and thence to the Duke’s house, and saw “Macbeth”, which, though I saw it lately, yet appears a most excellent play in all respects, but especially in divertisement, though it be a deep tragedy; which is a strange perfection in a tragedy, it being most proper here, and suitable’ (7 January 1667); ‘So to the playhouse, not much company come, which I impute to the heat of the weather, it being very hot. Here we saw “Macbeth”, which, though I have seen it often, yet is it one of the best plays for a stage, and variety of dancing and music, that I ever saw’ (19 April 1667); ‘I was vexed to see Young (who is but a bad actor at best) act Macbeth in the room of Betterton, who, poor man! is sick: but, Lord! What a prejudice it wrought in me against the whole play’ (16 October 1667); ‘Thence to the Duke’s playhouse, and saw “Macbeth.” The King and Court there; and we sat just under them and my Lady Castlemayne, and close to the woman that comes into the pit, a kind of loose gossip, that pretends to be like her’ (21 December 1668). Pepys was nearly as fond of the Davenant–Dryden adaptation of The Tempest, but other Shakespearian comedies pleased him less: he dismissed A Midsummer Night’s Dream, for example, as ‘the most insipid ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life’ (29 September 1662).

Catherine Alexander

Percy, Henry. (1) See Northumberland, Earl of. (2) See Hotspur.

Anne Button

Percy, Lady. *Hotspur’s wife (b. 1371), called ‘Kate’ by him, appears in 1 Henry IV 2.4 and 3.1, and as a widow in 2 Henry IV 2.3.

Anne Button

Percy, Thomas. See Worcester, Earl of.

Perdita is the daughter of Hermione and Leontes in The Winter’s Tale. The parallel character is Fawnia in *Greene’s Pandosto, Shakespeare’s chief source.

Anne Button

Perdita; or, The Royal Milkmaid. See burlesques and travesties of Shakespeare’s plays.

performance criticism, in Shakespeare studies, a term for the kind of analysis of Shakespeare’s plays which considers them as scripts only fully realized in performance, rather than solely as literary works to be read on the page.

Despite the anti-theatrical perspective of many 18th-century editors, and the dominant *Romantic and 19th-century view of Shakespeare as a poet whose works only happened to take the form of plays, this has always been a strong element in Shakespeare criticism (exemplified, for example, by *Hazlitt, and by professional theatre reviewers from Leigh *Hunt onwards), but it has been newly prominent since the mid-20th century, as the academic study of Shakespearian drama has extended from the library and the classroom and into the theatre. The amount of space which major editions of the plays such as the *Arden devote to considerations of performance (both in Shakespeare’s time and since) has increased immensely since the 1970s, for example, while series such as Shakespeare in Performance (Manchester University Press, 1984– ) and Shakespeare in Production (Cambridge University Press, 1996–, the successor to Plays in Performance, 1981– ) have proliferated.

Much contemporary performance criticism draws on semiotics, and, in reading performance as a social as well as an aesthetic event, incorporates some form of cultural theory. An influential work was Raymond Williams’s chapter on Antony and Cleopatra in his Drama in Performance (1954): since then important exponents of performance criticism have included J. L. Styan, Dennis Kennedy, and Peter Holland.

Michael Dobson

performance times, lengths. Ordinarily at open-air and indoor hall playhouses the performances began at 2 p.m. and 3 p.m. and lasted two to three hours; the elite indoor venues probably had more latitude to run late than did the amphitheatres. At court the performances were always at night, and quite possibly the authorities in towns visited by touring companies were flexible, since an unanticipated performance would draw a larger crowd if it began after the working day was finished. No contemporary reference to performance lengths is shorter than the Romeo and Juliet Prologue’s ‘two-hours’ traffic’ and a few go as high as three hours, which is a variation of +/− 20% around a norm of 2.5 hours. Surviving play-texts, on the other hand, vary by as much as +/− 50% around a norm of about 2,600 lines, with a tendency to longer plays in the later years. Whether plays were routinely cut for performance remains a matter of argument.

Gabriel Egan

periphrasis, a figure of speech in which something is referred to by circumlocution where a more direct expression is available:

As he is but my father’s brother’s son

(Richard II 1.1.117)

Chris Baldick

perspective. Stage scenery can be made to appear three dimensional by illusionistic techniques of painting based upon perspective foreshortening, but this technique was not used in the theatres until the Restoration. Artificial perspective effects require spectators to view from within a predefined focal area and so demand a seated audience all of whose members are looking in approximately the same direction, as in a hall playhouse; open-air playhouse conditions, with spectators all around the stage, are quite unsuited to perspective effects. Sebastiano Serlio’s mid-16th-century work on theatre perspective illusions was absorbed by Inigo *Jones and his assistant-nephew John Webb and emerged in the elaborate *court masques and in the perspective techniques of the Restoration theatres.

Gabriel Egan

Peter (1) Peter is the Nurse’s servant in Romeo and Juliet. (2) See Joseph.

Anne Button

Peter, Friar. See Friar Peter.

Peter of Pomfret is a prophet hanged by John, King John 4.2.

Anne Button

Peter Thump. See Horner, Thomas.

Peto brings news to Prince Harry, 2 Henry IV 2.4.358–63. See also Russell.

Anne Button

Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca) (1304–74), Italian humanist and poet who combined diplomatic missions abroad with the humanist quest for long-neglected classical works. He translated and published many such works while writing some of his own prose and verse compositions in Latin. Petrarch’s sonnets, dedicated to his beloved Laura, were published in collections called the Canzoniere and Trionfi. Their structure, themes, and conceits established a convention in sonneteering which lasted for more than 200 years, first imitated in England at the court of Henry VIII by Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. Shakespeare often wrote in the Petrarchan style, most notably in his own Sonnets and in Romeo and Juliet which includes a direct reference to Petrarch (2.3.36–7), but he was also part of a contemporary anti-Petrarchan movement and sometimes ridiculed the pretensions and frustrations of the Petrarchan lover.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

Petruccio (Petruchio). See Taming of the Shrew, The.

Phaonius, Marcus. See poets.

Phelps, Samuel (1804–78), English actor-manager, born in Devon. After an eleven-year provincial apprenticeship, which included Richard III, Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello, and Lear, Phelps made his London debut (for Ben Webster at the Haymarket in 1837) as Shylock, reviewed as judicious and correct rather than striking or remarkable. In the engagements with *Macready which followed Phelps generally found himself cast in subservient roles, or kept idle, though he seized such opportunities as Macduff (1837), Hubert (1842), and, alternating with Macready, Othello and Iago (1839).

Following the abolition of the patent theatres’ monopoly in 1843, Phelps set up in management (initially with Mrs Warner) at *Sadler’s Wells theatre in Islington with the professed objective of presenting ‘the first stock drama in the world…[performed by] a Company of acknowledged talent…in a theatre where all can see and hear, and at a price fairly within the habitual means of all’. In the opening production of Macbeth, Phelps as the Thane was acclaimed by experienced critics (who credited him with greater energy and reality than Macready) as well as local audiences. Thenceforward Shakespeare was established as the ‘house dramatist’, with revivals of 32 of his plays during the next eighteen years. These productions were characterized by a (relatively) full text, ensemble acting, and costumes and sets, of which gauzes and dioramas were regular features, which illuminated rather than swamped the play. Although he was indisputably the leading actor Phelps ensured that his performances harmonized with the production as a whole. Thus Henry Morley wrote that Phelps’s Bottom ‘was completely incorporated with the Midsummer Night’s Dream, made an essential part of it, as unsubstantial, as airy and refined as all the rest’.

Following the termination of his management in 1862, Phelps continued to work as an actor in London and the provinces (especially in Manchester with *Calvert), where his Shakespearian performances established a tradition for young actors to follow, notably Johnston *Forbes-Robertson, who played Hal to Phelps’s Henry IV, which the veteran actor doubled with Justice Shallow. The high point came in the Jerusalem chamber encounter between father and son, with Phelps’s broken emphasis on ‘Harry’ (‘Come hither, Harry’) maximizing the pathos of their affectionate reconciliation.

Richard Foulkes

Philemon is Cerimon’s servant, Pericles 12.

Anne Button

Philharmonus. See soothsayers.

Philip, King of France. He supports Arthur’s claim to the English throne in King John.

Anne Button

Phillips, Augustine (d. 1605), actor (Strange’s Men 1593, Chamberlain’s/King’s Men 1598–1605). Phillips is named as taking the role of Sardanapalus in ‘Sloth’ in the plot of 2 Seven Deadly Sins which was performed before 1594, possibly by Strange’s Men. A touring licence issued to Strange’s Men by the Privy Council names Phillips, but by 1598 he had joined the Chamberlain’s Men, appearing in the actor lists for *Jonson’s Every Man in his Humour and Every Man out of his Humour, and Sejanus, as printed in the 1616 folio. When the syndicate to run the Globe was formed in 1599 Phillips was a member, and on 18 February 1601 he was called upon to explain to Chief Justice Popham and Justice Fenner why the company had performed Shakespeare’s Richard II, which dramatizes usurpation, at the Globe on the eve of *Essex’s rebellion and at the request of his supporters. Phillips’s name appears in the King’s Men’s patent of 1603 and the actor list of the 1623 Folio of Shakespeare’s plays. The circumstances of Phillips’s marriage are unclear, but Simon *Forman’s notes suggest that he was twice rejected in marriage suits before being accepted by Anne, who survived him. In his will Phillips left money to his fellow actors (including Shakespeare) and costumes, properties, and musical instruments to his apprentice Samuel *Gilburne.

Gabriel Egan

Philo, Antony’s friend in Antony and Cleopatra, only appears in the first scene.

Anne Button

Philostrate, Theseus’ Master of the Revels, appears (mute) in the first scene of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. (In *quarto editions he also introduces the interlude of the ‘hard-handed men’ in Act 5, but the Folio reassigns these speeches to Egeus).

Anne Button

Philoten, the daughter of Dioniza, is described by Gower, Pericles 15, but does not appear.

Anne Button

Philotus’ Servant. See Hortensius’ Servant.

Phoebe (Phebe in the *Folio), loved by Silvius in As You Like It, herself falls in love with *‘Ganymede’.

Anne Button

‘Phoenix and Turtle, The’, a *lyric poem—also known as ‘The Phoenix and the Turtle’—ascribed to Shakespeare when it appeared, untitled, as one of the ‘Poetical Essays’ by various authors, including the playwrights Ben *Jonson, George *Chapman, and John *Marston, in Robert *Chester’s Love’s Martyr; or, Rosalind’s Complaint (1601, repr. 1611). It was later included in John Benson’s 1640 edition of Shakespeare’s poems.

Chester’s Love’s Martyr is a long poem described as ‘allegorically showing the truth of love in the constant fate of the phoenix and turtle’ (i.e. turtle dove). The ‘poetical essays’ appended to it are called ‘Divers poetical essays on the former subject, viz. the turtle and phoenix, done by the best and chiefest of our modern writers, with their names subscribed to their particular works; never before extant.’ How Shakespeare came to be involved in the enterprise is not known; he appears to have read Chester’s poem before writing his own, a 67-line allegorical elegy which mounts in intensity through its three parts. First it summons a convocation of benevolent birds, with a swan as priest, to celebrate the funeral rites of the phoenix and the turtle dove, who have ‘fled | In a mutual flame from hence’. Then the birds sing an anthem in which the death of the lovers is seen as marking the end of all ‘love and constancy’.

So they loved as love in twain

Had the essence but in one,

Two distincts, division none.

Number there in love was slain.

Their mutuality was such that ‘Either was the other’s mine’. Finally Love makes a funeral song

To the phoenix and the dove,

Co-supremes and stars of love,

As chorus to their tragic scene.

This threnos—funeral song—is set off by being written in an even more incantatory style than what precedes it; each of its five stanzas has three rhyming lines, and the tone is one of grave simplicity.

The poem, often regarded as one of the most intensely if mysteriously beautiful of Shakespeare’s works, is usually assumed to have been composed not long before publication, though Honigmann (see Chester, Robert) dates it as early as 1586. Its affinities and poetical style seem to lie rather with Shakespeare’s later than his earlier work. In subject matter it appears to have irrecoverable allegorical significance. Various scholars have identified one or other of the phoenix and the turtle with the dedicatee Sir John Salisbury and his wife, Queen Elizabeth, her collective subjects, the Earl of *Essex, Shakespeare himself, and even the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno (who died at the stake in 1600). G. Wilson *Knight, one of the poem’s most passionate advocates, supposed that ‘the Turtle signifies the female aspect of the male poet’s soul’.

Stanley Wells

Phoenix theatre. See Beeston, Christopher.

Phrynia and Timandra (Tymandra), both mistresses of Alcibiades, are given gold and verbal abuse by Timon, Timon of Athens 4.3.

Anne Button

Picasso, Pablo (1881–1973), Spanish artist. In 1964 Picasso made a series of twelve drawings on the theme of Shakespeare and Hamlet to commemorate the quatercentenary of Shakespeare’s birth, as well as a number of related ‘portrait’ heads of the poet. The Hamlet series was published the following year in Louis Aragon’s Shakespeare (published by Éditions Cercle d’Art, 1965).

Richard Johns

Pimlico, an anonymous pamphlet printed in 1609, refers to a crowd swarming as if at a ‘new-play’ such as ‘Pericles’. Hence Pericles must have existed, and still been relatively new, when Pimlico was registered on 15 April 1609.

Park Honan

Pimlott, Steven (1953–2007), English opera and theatre director. Pimlott started out with the English National Opera in the mid-1970s, moving on to work with several opera companies, including a regional stint at the Crucible Theatre, Sheffield, where he made his first forays into directing Shakespeare in 1987, helming productions of Twelfth Night and The Winter’s Tale. In the early 1990s he worked with the *RSC under Adrian *Noble, beginning with a production of Julius Caesar in 1991 with Sir Robert *Stephens in the title role, and David *Bradley as Cassius. Between 1994 and 1996 Pimlott mounted three more productions, all of which enjoyed successful London transfers, Measure for Measure starring Alex Jennings as Angelo, a sinisterly comic Richard III led by David Troughton, and an As You Like It starring a then-unknown David *Tennant as Touchstone. Perhaps his most enduringly popular works for the company remain his two ‘white box’ productions: a dazzlingly spare and intimate Richard II in the *Other Place in 2000, and a vast, haunting and lonely Hamlet in the old *Royal Shakespeare Theatre stage-space the following year, with Samuel *West impressing in the title roles of both. Pimlott was awarded the OBE in the 2007 New Year Honours list.

Will Sharpe

Pinch, Dr. He attempts to exorcize the supposedly possessed Antipholus of Ephesus and Dromio of Ephesus in The Comedy of Errors 4.4: he derives from ‘Medicus’ in *Plautus’ Menaechmi.

Anne Button

Pindarus. See Cassius, Caius.

pipe, in Shakespearian usage, specifically the three-holed pipe played with the *tabor (see Much Ado About Nothing 2.3.15); also used as a term for wind instruments generally.

Jeremy Barlow

piracy. See reported text.

Pirithous (Perithous), Theseus’ friend and attendant, describes Arcite’s fatal accident, The Two Noble Kinsmen 5.6.48–85.

Anne Button

Pisanio, Posthumus’ servant, is commanded by him to kill Innogen in Cymbeline.

Anne Button

Pistol is at the centre of the tavern brawl in 2 Henry IV 2.4. In 5.3 he announces the death of Henry IV and in 5.4 witnesses Sir John’s rejection by the new King and is taken with Sir John and others to prison. In The Merry Wives of Windsor he refuses to act as Sir John’s go-between and betrays him to Ford (2.1). In Henry V, now married to Mistress Quickly, he joins Harry’s French campaign after Sir John’s death. In France his quarrels with Fluellen culminate when the latter forces him to eat a leek: by now the revelations of his dishonesty and cowardice render him a pathetic as much as a comical figure, completing the picture of the disintegration and decay of Harry’s old set of acquaintances.

Actors have made the most of the flamboyantly bombastic side of the role: most famously, Theophilus *Cibber was nicknamed ‘Pistol’, both for his superlative performance as such and for his alleged offstage resemblance to the character. In modern times, though, the role, with its swaggering mock-Marlovian jargon, has become less easily comprehensible, and directors have often resorted to elaborate comic stage business: in Trevor *Nunn’s 1982 2 Henry IV, for example, Pistol’s eviction from the tavern was accompanied by much chasing up and down the immense set and firing of his gun. Michael *Bogdanov (1986) had him in motorbike leathers bearing the label ‘Hal’s Angels’ and a T-shirt which, alluding to the punk group the Sex Pistols and the title of their collected works, read ‘Never mind the bollocks; Here comes Pistol’.

Anne Button

pit. The area of ground-level seating nearest the stage of an indoor hall playhouse such as the Blackfriars, corresponding in location and relative low cost to the yard in the open-air amphitheatres. A thrust stage projecting into the pit would be surrounded by seats.

Gabriel Egan

Pitt Press Shakespeare. This early *schools edition of the individual plays began to appear in 1893, and was intended by the editor, A. W. Verity, for ‘schoolboys’ aged 14 and up. It offered them a short introduction describing aspects of each play, its characters, and giving an outline of the story. The plain text was followed by extensive notes and a glossary, so no schoolboy could complain of shortage of information.

R. A. Foakes

Place Calling Itself Rome, A (1973), a modernized English version of Coriolanus by John Osborne (1929–94). Given Germany’s turbulent modern history, Bertolt *Brecht (Coriolanus, 1951–3) and Günter Grass (The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising, 1966) have produced the major 20th-century dramatic reactions to Shakespeare’s republican Rome. However, Caius Martius’ reactionary political opinions, capacity for demotic invective, and mother-fixated sexual nausea make Osborne a powerful apologist in this angry play.

Tom Matheson

plague was unhappily frequent in Shakespeare’s London, but its causation was not known. The disease is transmitted by the bite of an infected rat flea. The flea, though, will only bite humans when it has infected and killed all the local rats. This means that there are no rats around when an epidemic breaks out and their part in the process is not evident. Moreover the rat flea, unlike the human one, cannot hop far, so that people who are just visiting the sick are unlikely to get infected. However the flea can live for weeks without food if the humidity and temperature are right for it. The clothing and bedding of plague victims are particularly dangerous, as are wooden buildings, earthen floors, rubbish heaps, and dunghills. Hence the poor suffered far more in an epidemic than the rich.

Medical opinion never suspected the flea or the rat, and the disease was normally thought to be spread by contagion from the air and from infected sufferers (see medicine). Therefore, when plague struck, one of the first measures taken by the authorities to prevent it spreading was to close the playhouses. This was no light matter for the actors’ companies—for instance between 1603 and 1613 the theatres were closed for a total of 78 months. Even if they managed to get engagements to play outside London it still meant a curtailment of their activities. Indeed it has been suggested, on the plausible assumption that Shakespeare only wrote a play when there was an immediate demand for one, that the gaps in his dramatic creativity and his seemingly early retirement can be largely accounted for by these closings of the theatre.

If so, epidemics of the plague were more important for Shakespeare than for his characters, who neither catch it nor die from it. Plague and pestilence are words more often used in cursing than to describe a real medical event. Once or twice they are used jokingly to refer to falling in love, as when Biron says, ‘They have the plague, and caught it of your eyes’ (Love’s Labour’s Lost 5.2.422). And there is an even more unexpected, though perfectly logical, use. If bad air helped spread the disease, good air should prevent it. Pomanders were used for this purpose. But one could extend the principle to young and healthy people. ‘The plague is banished by thy breath’, says Venus, dreamingly, of Adonis (Venus and Adonis 510). ‘Methought she purged the air of pestilence’, says Orsino of Olivia (Twelfth Night 1.1.19). It is an attractive thought: one only wishes it could have been true.

Maurice Pope

plague regulations. A large crowd gathering in a confined space, such as a playhouse, was thought to give ideal conditions for transmission of the plague, and the Privy Council closed the playhouses when the weekly death toll exceeded 50 (reduced under James I to 30).

Gabriel Egan

Planché, James Robinson (1796–1880), English playwright and antiquarian, who became Somerset Herald (1866). His prolific and diverse output extended to some 150 theatrical pieces (extravaganzas, pantomimes, and librettos, including Weber’s Oberon, 1826), scholarly works such as his History of British Costume (1834), his Recollections and Reflections (1872), and designs for several Shakespeare plays. His costumes for Charles *Kemble’s King John (1823) broke new ground by setting the play in its historical period, even citing ‘Authorities for the Costumes’ on the playbill. Planché worked on Madame *Vestris’s notable productions of Love’s Labour’s Lost and A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Ben Webster’s Elizabethan-style The Taming of the Shrew (1844).

Richard Foulkes

Planchon, Roger (1931–2009), French actor, director (Théâtre de la Cité, Villeurbanne, near Lyon) and playwright, who explored the full range of the French repertoire. His Richard III (1966 Avignon Festival, then Villeurbanne) was influenced by post-*Brechtian theories. He played the title roles in Antony and Cleopatra and Pericles (1978) in sets recalling well-known epic films.

Isabelle Schwartz-Gastine

Plantagenet, Edward. See Aumerle, Duke of; York, Duke of.

Plantagenet, Lady Margaret. See Clarence’s Son.

Plantagenet, Richard. (1) Duke of York, see 1 Henry VI; The First Part of the Contention; Richard Duke of York. (2) See Cambridge, Richard, Earl of.

Plants. Plants are ubiquitous in Shakespeare’s plays and poems. It might be presumed that the dramatist was primarily influenced by his native Warwickshire: the vigour of folklore and the variety of colourful local plant names offered a rich source of suggestion, but the language of plants, a common currency of the rural world, was augmented in Shakespeare’s London by ‘green desire’, a new-found passion for plants and gardens. The second half of the 16th century witnessed an unprecedented exploration of the botanic world and an outpouring of related publications which peaked in the 1590s. A network of enthusiasts, the development of markets in seeds and plants and the construction of hugely expensive private gardens all testify to the magnitude of intellectual and financial investment in botanical capital. Plant hunters, researchers, apothecaries, herb-women, physicians, and grandees were caught up in a cooperative enterprise. Just as Marlowe’s eponymous Jew of Malta relishes being at the centre of a global trading and financial nexus (1.1.1–48), these horticulturalists revelled in the commerce of a botanical universe. Responding to this heightened sensibility the dramatist was able to express conceptually and figuratively the ideas and discoveries in the botanical world, confident that the intended resonances would be acknowledged. Plants were freighted with meaning.

The dominant botanical text was the herbal. Initially a guide to plant identification and their medicinal applications, the herbal became an encyclopaedia with detailed descriptions and pictorial representations supported by information on habitat and the various names attaching to each plant. William Turner (c. 1508–68), regarded as the father of English botany, records almost 400 plants in The Names of Herbes (1548). Locating each plant in its natural habitat he was the first to provide detailed descriptions of British native flora. By happy coincidence the final part of England’s first plant book of genuine originality, Turner’s A new herball (1564), was published in the year of Shakespeare’s birth. Gerard’s Herbal of 1597 commandeered the endeavours of a generation of botanical writers—including those of a brilliant group of refugees located in Lime Street. A pictorial and literary cornucopia, referencing around 2,000 plants, it embodies the spirit of the age.

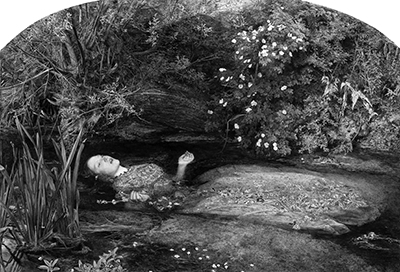

Several plants mentioned by Shakespeare are denoted by two or more names e.g. bay/laurel, blackberry/bramble, clover/honeystalks, cuckoo-flower/lady-smocks, Cupid’s flower/love-in-idleness/pansy. Sometimes one name is applied to two different plants. ‘Bramble’ signifying a blackberry bush can also intimate the wild rose. Many named plants have defied all efforts at identification. Several, such as ‘long purples’ or ‘dead men’s fingers’, ‘cuckoo-buds’, ‘Dian’s bud’, ‘kecksy’, ‘hardock’, ‘hebona’, names first recorded in Shakespeare, give rise to uncertainty and speculation, whereas there is general agreement about other first usages like ‘eringo’ (sea-holly), ‘honeystalks’ (clover) and ‘mary-bud’ (marigold). Some plants, ‘Cupid’s flower’, ‘Arabian tree’, ‘crow-flower’ and ‘cuckoo-bud’, defy definitive identification; ‘chimney sweeper’ and ‘centaury’ pose the question as to whether any plant is alluded to. Potential ambiguities include ‘canker’, which can mean wild rose, or more frequently, the grub that destroys flower buds. ‘Peonied’ (The Tempest 4.1.64) is sometimes glossed as ‘peony’—a well-known flower of the period described by Gerard—but a woven structure supporting the riverbank is a more likely meaning. Problems of identification are particularly frustrating when symbolism is implicated. Notable examples are Ophelia’s carefully allocated flowers and herbs, the plants included in Gertrude’s narration of Ophelia’s drowning, and Lear’s floral crown. Some plant names are used to designate characters (Viola, Fluellen, Cicely, Pimpernel, Dogberry, Costard); Angelica is unique: the appellation may refer to the culinary herb or to a person. There is a discrepancy, therefore, between the number of named plants (almost 200 individual names plus c. 10 generic names) and the number of plants that are present in Shakespeare’s work.

With over 120 mentions the rose is the most frequently named plant, followed by the lily, then the violet. Introduced from Turkey in the 1570s the most recently arrived exotic mentioned in Shakespeare is the ‘crown imperial’ (The Winter’s Tale 4.4.126), Flowers are important not only because of their symbolic significance but also for the poetic potential carried in their names—often heightened by the epithets Shakespeare attaches to them: ‘pale primroses’, ‘bold oxlips’, ‘freckled cowslip’, ‘azured harebell’, ‘daisies pied’. The gillyflower is ‘streaked’, violets are ‘dim’ or ‘blue-veined’, the rose is ‘crimson’, ‘vermilion’, ‘blushing’, ‘milk-white’, ‘fragrant’. The visual and atmospheric frequently cohere: ‘daffodils | That come before the swallow dares, and take | The winds of March with beauty’ (The Winter’s Tale 4.4.118–20). The water iris, subject to the sway of the current, is designated ‘a vagabond flag’ (Antony and Cleopatra 1.4.45). At his death Adonis is metamorphosed into a flower (Venus and Adonis 1165–76). Often the focus is on the fruit of a plant. Here again epithets can be significant: the ‘rubied cherry’ and ‘clust’ring filberts’ catch both the eye and the ear. The peach is mentioned only for its colour. Fruits are frequently sources of exoticism and eroticism e.g. A Midsummer Night’s Dream 3.1.158–9. The names of the fruits, accentuated by alliteration and assonance, promote a sensual atmosphere. Both ‘apricocks’ and ‘figs’ are sexually suggestive. Prunes are associated with brothels e.g. 2 Henry IV 2.4.140–2; Measure for Measure 2.1.87–104. Trees both native and exotic abound: apricot, Arabian tree (date/palm), ash, aspen, balsamum, bay, beech, cedar, cypress, ebony, elder, elm, holly, myrtle, oak, olive, palm, pine, plane, pomegranate, sycamore, willow. A plant is sometimes mentioned for just one aspect: ginger is specified as a culinary ingredient; ebony is celebrated for its black, lustrous quality. Some plants have generally accepted symbolic significance: the willow is the emblem of forsaken love; the lily represents purity; both cypress and yew are linked to sadness, death, and graveyards; the sycamore signifies sadness or melancholy; the palm is a symbol of victory but also serves to validate a pilgrimage; the oaken garland commemorates triumph. On occasion contrasting, even antithetical meanings are ascribed to some plants. The strawberry can represent abundance, chastity, fertility, humility, modesty, purity and paradise, but can also symbolize sensuality and eroticism. Weeds, besides implying neglect, were imaged as emblematic of the fallen world.

The dramatist uses the natural world as analogy, simile, metaphor, and as a contributor to other rhetorical devices. Chastising Wolsey for burdening the populace with excessive taxation, Henry VIII delivers his economic analysis by way of an arboreal analogy (All Is True 1.2.96–9). Acknowledging his irrevocable loss of power, Cardinal Wolsey expresses his predicament in terms of the growth, blossoming and blighting of plants (3.2.353–9).

Plants and their immediate environment are frequently a source of delicate imagery: Antony’s makeshift ambassador likens himself to ‘the morn-dew on the myrtle leaf’ (Antony and Cleopatra 3.12.9); Lavinia’s ‘lily hands | Tremble like aspen leaves upon a lute’ (Titus Andronicus 2.4.44–5); Aufidius claims Coriolanus ‘watered his new plants with dews of flattery’ (Coriolanus 5.6.22); Innogen’s birthmark is ‘cinque-spotted, like the crimson drops | I’th’ bottom of a cowslip’ (Cymbeline 2.2.38–9); later, as the seemingly dead Fidele, Innogen is promised, ‘Thou shalt not lack | The flower that’s like thy face, pale primrose, nor | The azured harebell, like thy veins; no, nor | The leaf of eglantine, whom not to slander | Outsweetened not thy breath’ (4.2.221–5). The tradition of the cherry symbolizing closeness or twinning, usually feminine, is best captured in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (3.2.209–12) where ‘two in oneness’ is the conceptual nucleus of the play. Oberon’s evocation of the profusion of plants in the Athenian wood is intoxicating (2.1.249–52); Hamlet reviles the burgeoning corruption of the world: ‘’Tis an unweeded garden | That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature | Possess it merely’ (Hamlet 1.2.135–7). The dramatist generates pressure not only through imagery but also by his orchestration of sound values and the associated potential of plants. Exploiting the assonance and alliteration of two soporifics, Iago savours Othello’s anguish: ‘Not poppy nor mandragora | Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world | Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep | Which thou owedst yesterday’ (Othello 3.3.334–7). Again Iago extracts maximum effect from his deployment of richly resonant sounds when assuring Roderigo that Othello’s passion for Desdemona will be short-lived: ‘The food that to him now is as luscious as locusts shall be to him shortly as bitter as coloquintida’ (1.3.347–9). Luxuriating in assonance, Iago’s contrast between the sweet locust fruit of the Cyprian carob tree and the equally exotic ‘bitter apple’ creates plausibility through verbal alchemy. The single mention of samphire brings into view an entire landscape (King Lear 4.5.11–24).

Plants freighted with meaning frequently resist interpretation: Ophelia’s dispensation of herbs and flowers (Hamlet 4.5.175–84); Gertrude’s description of Ophelia’s drowning (4.7.138–55); the garland worn by the Jailer’s Daughter (The Two Noble Kinsmen 4.1.82–90) and Lear’s ‘crown’ of weeds and flowers (King Lear 4.3.1–6). The longest speech embracing the largest number of plants is Burgundy’s representation of the desecration of French agriculture and landscape (‘this best garden of the world’) by the invading army of Henry V (Henry V 5.2.31–55). The garden scene in Richard II (3.4.), emblematic of the body politic, encompasses a dialogue on plant husbandry. Iago provides an extended analogy between the garden and the soul (Othello 1.3.319–32). Mentioned only twice, the potato was viewed as an aphrodisiac. For his assignation with the merry wives Falstaff seeks renewal of his enfeebled sexual prowess: ‘Let the sky rain potatoes’ (The Merry Wives of Windsor 5.5.18–19). Its role in Troilus and Cressida is more sordid than comic (5.2.55–7).

‘Leaf’ can mean ‘petal’, as instanced by Basset’s reference to the rose and ‘the sanguine colour of the leaves’ (1 Henry VI 4.1.92). ‘Petal’ found its way into English via John Ray in 1682. The generic use of ‘herb’ to cover a range of plants including flowers is apparent in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Oberon instructs Puck: ‘Fetch me that flower; the herb I showed thee once’ (2.1.169) and uses the word ‘herb’ three more times when alluding to a flower. In Venus and Adonis distinctions are made by the narrator when portraying the response of the natural world to Adonis’ fatal wound: ‘No flower was nigh, no grass, herb, leaf, or weed, | But stole his blood, and seemed with him to bleed’ (1055–6). The difference between salad herbs and ‘nose herbs’, valued for their scent, emerges in a dialogue between Lafeu and Lavatch in All’s Well That Ends Well (4.5.13–19). Rosemary had diverse uses but symbolically it represented remembrance, something made explicit by Ophelia (Hamlet 4.5.175). Less obvious in meaning is its culinary function. Rosemary, as a garnish, was viewed as ostentatious. Hence its figurative application in Pericles where the Bawd derides Marina as ‘my dish of chastity with rosemary and bays’ (19.175–6).

Increasing plant availability stimulated scientific experimentation in both curative medicine and poisons by physicians, apothecaries and the curious. A thriving market-place for herbs, London’s Bucklersbury, alluded to by Falstaff (The Merry Wives of Windsor 3.3.67), was indicative of demand for and a ready supply of these plants for culinary, aromatic, and medicinal uses (referred to as ‘simples’). A division of labour is apparent in Pericles where the skilful physician Cerimon hands a prescription to a servant, ‘Give this to th’ pothecary | And tell me how it works’ (12.8–9). Here is also an indication of empiricism central to the scientific project. The Friar in Romeo and Juliet, fully aware of the duality possessed by plants integral to pharmacopoeia, distinguishes between ‘baleful weeds and precious-juiced flowers’, and acknowledges that within a single flower, ‘Poison hath residence and medicine power’ (Romeo and Juliet 2.3.8–24). The impoverished apothecary who provides Romeo with poison is subject to strict legal constraints (5.1.66–7). Laertes acquires his deadly poison from an unlicensed ‘mountebank’ (Hamlet 4.7.114). The Queen in Cymbeline has a predilection to experiment with poisons (1.5.1–44).

The most significant botanical exchange in Shakespeare foregrounds the relationship between art and nature. Perdita’s reluctance to grow ‘carnations and streaked gillyvors | Which some call nature’s bastards’ arises from her understanding that ‘There is an art which in their piedness shares | With great creating nature’. Unconvinced by Polixenes’ assurance that techniques used to enhance plant variety are rational—mankind is not a usurper of nature but a collaborator—she links such artifice with the impropriety of face painting (4.4.79–103). Polixenes was over-estimating the prevailing state of horticultural knowledge or ‘art’. Hybridization was not understood at the time, but the obsession with new forms and varieties led to vigorous though ineffectual efforts to enhance this process by human intervention. Where diversity occurred it was a natural phenomenon. The divergent views of Polixenes and Perdita reverberated throughout the 17th century and became the subject of theological unease for another two centuries. Andrew Marvell’s poem ‘The Mower, Against Gardens’ is a severe indictment of human arrogance and duplicity: Perdita is clearly visible in Marvell’s mirror.

Vivian Thomas

Platter, Thomas (1574–1682), Swiss traveller. Born in Basle, Platter took his medical baccalaureate at the Université de Montpellier, and later visited England from 18 September to 20 October 1599. Writing in a difficult German dialect, he noted that on 21 September he crossed the Thames and observed a tragedy about Julius Caesar, performed ‘with approximately fifteen characters’, in ‘the straw-thatched house’ (‘steüwine Dachhaus’). He may report on an unknown ‘Caesar’ drama; but it is probable that he saw Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, and that he offers the earliest report of any dramatic performance at the newly built *Globe. The most approved modern translation of Platter’s remarks on the play is Ernest Schanzer’s, in ‘Thomas Platter on the Elizabethan Stage’, Notes and Queries, 201 (1956).

Park Honan

Plautus (c. 254–184 bc), Roman comic dramatist who wrote in the tradition of the New Comedy, popular in 4th-century Greece and exemplified by the work of Menander. Of the 130 plays attributed to Plautus in the 1st century bc, 21 survive, more than any other classical playwright and a testament to his contemporary success. Plautus was one of the causes célèbres of Renaissance humanism, admired for his witty and vivacious style and for the intricacy of his comic plots. Henry VIII commanded the performance of two of his plays at court and throughout the 16th century there were numerous continental translations and adaptations of his plays. Stephen Gosson complained that early English drama ‘smelt of Plautus’. The Plautine mode of comedy was based upon stock characters, including the crafty servant or the braggart soldier (miles gloriosus), which often figured in early English comedy. Perhaps most Plautine, however, was the plot of confusion or error based on mistaken identity in which these characters appeared. This could be the deliberate deception practised by the stock character of the trickster or that practised by nature through the phenomenon of twins. In The Comedy of Errors, Shakespeare combined the ‘errors’ of two Plautine comedies, Menaechmi and Amphitruo, to compound the possible confusion. The Comedy of Errors also employs the Plautine convention of a child lost and found, and of a family reunited. The Taming of the Shrew, Twelfth Night, and All’s Well That Ends Well all contain elements of Plautine comedy. Shakespeare probably read the Menaechmi, and other Plautine plays (Amphitruo, Rudens, and Mostellaria), in Latin.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

playbills, public notices advertising that plays were to be performed, attached to posts in the surrounding district. No playbills have survived from Shakespeare’s time, so we cannot be sure how much detail was given. Richard Vennar’s advertisement for his entertainment England’s Joy at the Swan in 1603 was fraudulent—he planned to steal the receipts without giving a performance—so it cannot be regarded as a typical playbill.

Gabriel Egan

playbook, the official play-text manuscript (or ‘book’), containing the essential licence from the Master of the Revels. From this valuable document—which ordinarily never left the theatre—the bookkeeper would have actors’ parts copied, and he might also annotate the playbook with reminders and additional directions to help him run the performance from offstage. The word promptbook is equivalent, although prompting (in the sense of reminding actors of their lines) does not seem to have happened in Shakespeare’s time.

Gabriel Egan

‘Player King’. See players.

‘Player Queen’. See players.

Players. (1) As part of a lord’s deception of Sly in the Induction, they perform the bulk of The Taming of the Shrew. (2) After much advice from the Prince, they perform the play presented by Hamlet to King Claudius, Hamlet 3.2. The Player King plays Duke Gonzago, and the Player Queen his wife Baptista. Other parts are the Prologue and the poisoner Lucianus.

Anne Button

players’ quartos. See quartos.

Players’ Shakespeare. This rather grand large-paper limited edition, published by Ernest Benn, set out to print Shakespeare’s plays ‘litteratim from the First Folio of 1623’, with line-blocks by various artists, among them Paul Nash, and long introductions by Harley *Granville-Barker. The edition ran out of steam after seven plays had been published between 1923 and 1927. It provided the occasion for Granville-Barker to develop *performance criticism’ in what later became well known as his ‘Prefaces’ to Shakespeare; the first three of these (to Julius Caesar, King Lear, and Love’s Labour’s Lost) were published in a separate volume in 1927.

R. A. Foakes

playhouses. See theatres, Elizabethan and Jacobean.

playing companies. See companies, playing.

Pléiade, French literary movement founded in 1549 by five university students including Joachim du Bellay and Pierre de Ronsard. Named after the Alexandrian society of the 3rd century bc, the group was inspired by the great writers of Greece and Rome, in particular Pindar and Anacreon, and by contemporary Italian literature. In dismay at the state of French literature, the Pléaide set out to reform it by importing the style, vocabulary, and themes of these classical and contemporary models into French poetry. The Pléiade’s translations and imitations of classical lyric, and its innovations in the sonnet form, influenced English Renaissance poetry.

Jane Kingsley-Smith

Pliny (ad 23/24–79), equestrian, rhetorician, and author of many works of history and rhetoric of which only the Naturalis historia survives. This is a study of the physical universe with sections on botany, geography, metallurgy, and human and animal biology. It was translated as Natural History or History of the World by Philemon Holland in 1601. That Shakespeare knew Pliny’s work is suggested by descriptions of exotic lands and peoples in Othello. Features drawn from Pliny include the Anthropophagi, Arabian trees which drop medicinal gum, and a description of the Pontic Sea (1.3.127–44, 5.2.359–60, 3.3.456–63).

Jane Kingsley-Smith

‘plots’. Scene-by-scene outlines of plays written on large sheets of paper and posted in early playhouses. Plots reminded actors when and in what character they were to appear, while alerting backstage personnel when specific properties were required and when music or noises were called for. Seven ‘plots’ or ‘platts’ from the period are extant, including two from the *Admiral’s or Strange’s Men c.1590 and five dating from 1597–1602.

Eric Rasmussen

Plummer, Christopher (b. 1929), Canadian actor. With Broadway experience behind him, he was the first Canadian-born actor to play leading parts in the Stratford Festival, Ontario, 1956–67, beginning with Henry V and going on to Hamlet, Leontes, Mercutio, Macbeth, Aguecheek, and Antony—absenting himself in 1961–2 to play Richard III and Benedick for the *Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford and London. In New York he has played Iago in Othello (1982) and the title role in a disastrous production of Macbeth with Glenda Jackson (1988). He also starred in a one-man show Barrymore, based on the life of the self-destructive Shakespearian player.

Michael Jamieson

Plutarch (L.[?] Mestrius Plutarchus) was born in Chaeronea to the west of Delphi in c.ad 46, and he died after ad 120. This makes him a direct contemporary of the great Roman historian Tacitus and, during his younger years, of the Emperors Claudius and Nero.

Plutarch wrote in his native Greek and was a prolific essayist, philosopher, biographer, and historian. He was best known in the Renaissance for his Parallel Lives, of which 23 have survived. In nineteen of them the biographies of famous Greeks and Romans such as Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar are compared.

Plutarch is an accomplished narrator who uses vivid anecdotes and colourful cameos to bring his characters to life. In the ‘Life of Alexander’ he famously noted that, as Sir Thomas North’s translation puts it, ‘The noblest deeds do not always show men’s virtues and vices, but oftentimes a light occasion, a word, or some sport, makes men’s natural dispositions and manners appear more plain than the famous battles won.’ For Plutarch history was a stage on which great men shaped the world according to their moral inclinations. It is fitting that the other collection of extant works by this much-travelled writer, who quietly ended his life at Delphi as a priest, should be called the Moralia.