Chapter 45 NURSING MANAGEMENT: renal and urological problems

1. Differentiate between the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, multidisciplinary care and drug therapy of cystitis, urethritis and pyelonephritis.

2. Explain the nursing management of urinary tract infections.

3. Describe the immunological mechanisms involved in glomerulonephritis.

4. Differentiate between the clinical manifestations and nursing and collaborative management of acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, Goodpasture’s syndrome and chronic glomerulonephritis.

5. Describe the common causes, clinical manifestations, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of nephrotic syndrome.

6. Compare and contrast the aetiology, clinical manifestations, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of various types of urinary calculi.

7. Evaluate the common causes and management of renal trauma, renal vascular problems and hereditary renal problems.

8. Describe the mechanisms of renal involvement in metabolic and connective tissue disorders.

9. Describe the clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of kidney cancer and bladder cancer.

10. Describe the common causes and management of bladder dysfunctions, particularly urinary incontinence and urinary retention.

11. Differentiate between ureteral, suprapubic, nephrostomy, urethral and external catheters with regard to indications for use and nursing responsibilities.

12. Analyse the nursing management of the patient undergoing nephrectomy or urinary diversion surgery.

Renal and urological disorders encompass a wide spectrum of clinical problems. The diverse causes of these disorders may involve infectious, immunological, obstructive, metabolic, collagen-vascular, traumatic, congenital, neoplastic and neurological mechanisms. This chapter discusses specific disorders of the upper urinary tract (kidneys and ureter) and lower urinary tract (bladder and urethra). Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease are discussed in Chapter 46. Female reproductive problems are discussed in Chapter 53, and male genitourinary problems are discussed in Chapter 54.

Urinary tract infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the second most common bacterial disease and the most common bacterial infection in women, with at least one-third of women developing a UTI before age 24. During their lifetime, more than half of all women will have a UTI and up to 50% of these will have another infection within a year.1 Pregnant women are at increased risk for UTIs,2 and UTIs are a frequently reported problem to general practitioners. In some situations people require hospitalisation because of a UTI. More than 15% of patients who develop Gram-negative bacteraemia die, and one-third of these cases are caused by bacterial infections originating in the urinary tract.1,3

Inflammation of the urinary tract may be attributable to a variety of disorders, but bacterial infection is by far the most common.1 The bladder and its contents are free from bacteria in the majority of healthy persons. Nevertheless, a minority of otherwise healthy individuals, including many sexually active, young adult women and older women and men, have some bacteria colonising the bladder. This condition is called asymptomatic bacteriuria and does not justify screening or treatment except in pregnant women.4 In contrast, an infection of the urinary system is diagnosed when bacterial invasion of the urinary tract occurs.

Escherichia coli (see Box 45-1) is the most common pathogen to cause a UTI, and is primarily seen in women. Bacterial counts of 105 colony-forming units per millilitre (CFU/mL) or higher typically indicate a clinically significant UTI. However, counts as low as 102–103 CFU/mL in a person with signs and symptoms are indicative of UTI. Although fungal and parasitic infections may also cause UTIs, they are uncommon. UTIs from these causes are sometimes observed in patients who are immunosuppressed, have diabetes mellitus or have undergone multiple courses of antibiotic therapy. Travelling in hot countries with poor access to clean water may also increase the risk of developing a UTI.

BOX 45-1 Microorganisms causing urinary tract infections

*Causative microorganism for urinary tract infection (UTI) in 80% of cases without urinary tract structural abnormalities or calculi.

†Typically identified as the causative microorganism for UTI associated with broad-spectrum antimicrobial antibiotic therapy and/or in patients with an indwelling catheter.

CLASSIFICATION

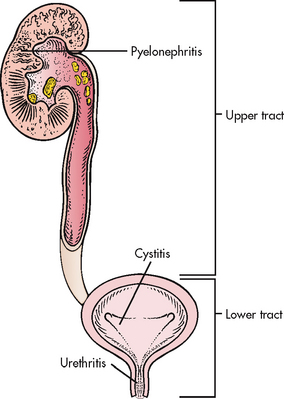

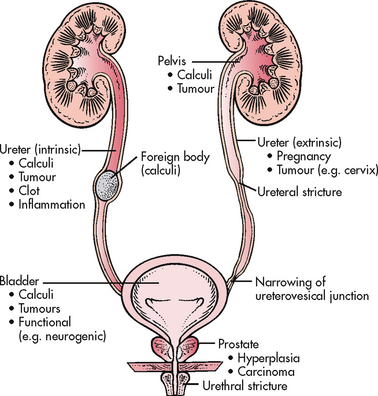

Several classification systems can be used for UTIs.1,3 For example, a UTI can be broadly classified as an upper or lower UTI according to its location within the urinary system (see Fig 45-1). Infection of the upper urinary tract (involving the renal parenchyma, pelvis and ureters) typically causes fever, chills and flank pain, whereas a UTI confined to the lower urinary tract does not usually have systemic manifestations. Specific terms are used to further delineate the location of a UTI or inflammation. For example, pyelonephritis implies inflammation (usually due to infection) of the renal parenchyma and collecting system, cystitis indicates inflammation of the bladder wall and urethritis means inflammation of the urethra. Urosepsis is a UTI that has spread into the systemic circulation and is a life-threatening condition requiring emergency treatment.

Classifying a UTI as complicated or uncomplicated is also useful.1,3 Uncomplicated infections are those that occur in an otherwise normal urinary tract and usually only involve the bladder.2 Complicated infections include those with coexisting presence of obstruction, stones or catheters; existing diabetes mellitus or neurological diseases; pregnancy-induced changes; or an infection that is recurrent. The individual with a complicated infection is at risk for pyelonephritis, urosepsis and renal damage.

UTIs can also be classified according to their natural history.4 An initial infection (sometimes called a first or isolated infection) refers to an uncomplicated UTI in a person who has never had an infection or experiences one that is remote from any previous UTI (usually separated by a period of years). In contrast, a recurrent UTI is a reinfection caused by a second pathogen in a person who experienced a previous infection that was successfully eradicated. If a recurrent UTI occurs because the original infection is not adequately eradicated, it is classified as unresolved bacteriuria or bacterial persistence. Unresolved bacteriuria occurs when bacteria are initially resistant to the antibiotic used to treat an infection, when the antibiotic agent fails to achieve adequate concentrations in the urine or bloodstream to kill bacteria, or when the drug is discontinued before the underlying bacteriuria is completely eradicated. Bacterial persistence may occur when bacteria develop resistance to the antibiotic agent selected for treatment or when a foreign body in the urinary system serves as a harbour or anchor allowing bacteria to survive despite appropriate therapy.3,5

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The urinary tract above the urethra is normally sterile. Several mechanical and physiological defence mechanisms assist in maintaining sterility and preventing UTIs. These defences include normal voiding with complete emptying of the bladder, ureterovesical junction competence and peristaltic activity that propels urine towards the bladder. Antibacterial characteristics of urine are maintained by an acidic pH (less than 6.0), high urea concentration and abundant glycoproteins that interfere with the growth of bacteria. An alteration in any of these defence mechanisms increases the risk of contracting a UTI. Box 45-2 lists predisposing factors to UTIs.

Menopause also appears to be a factor in the incidence of UTIs in women. Before menopause, glycogen-rich epithelial cells and the normal bacterial flora Lactobacillus keep the vaginal pH acidic (3.5–4.5). This acidic environment helps prevent the overgrowth of organisms that usually only proliferate in a pH above 4.5. In postmenopausal women, lower oestrogen levels cause vaginal atrophy, a decrease in vaginal lactobacilli and an increase in vaginal pH. This leads to an overgrowth of other organisms, specifically E. coli, and increases susceptibility to UTIs. Giving women low-dose intravaginal oestrogen replacement acidifies the vagina and may be effective in treating recurrent UTI.6

The organisms that usually cause UTIs are introduced via the ascending route from the urethra and originate in the perineum. Other less common routes are via the bloodstream or lymphatic system. Most infections are due to Gram-negative bacilli normally found in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, although Gram-positive organisms such as streptococci, enterococci and Staphylococcus saprophyticus can also cause urinary infections. A common factor contributing to ascending infection is urological instrumentation (e.g. catheterisation, cystoscopic examinations). Instrumentation allows bacteria that are normally present at the opening of the urethra to enter the urethra or bladder. Sexual intercourse promotes ‘milking’ of bacteria from the vagina and perineum and may cause minor urethral trauma that predisposes women to UTIs.

Rarely do UTIs result from a haematogenous route, where blood-borne bacteria secondarily invade the kidneys, ureters or bladder from elsewhere in the body. There must be prior injury to the urinary tract, such as obstruction of the ureter, damage caused by stones or renal scars, for a kidney infection to occur from haematogenous transmission.

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), previously called nosocomial infections, are an important source of UTIs. Indeed, 31% of all HAIs are UTIs.7 The cause of HAIs is often E. coli and, less frequently, Pseudomonas organisms. Catheter-acquired urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) are the most common HAIs and are caused by the development of bacterial biofilms that are found on the inner surface of the catheter.8 Most often these infections are underrecognised and undertreated, leading to complications such as renal abscesses, arthritis, epididymitis, periurethral gland infections and bacteraemia.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

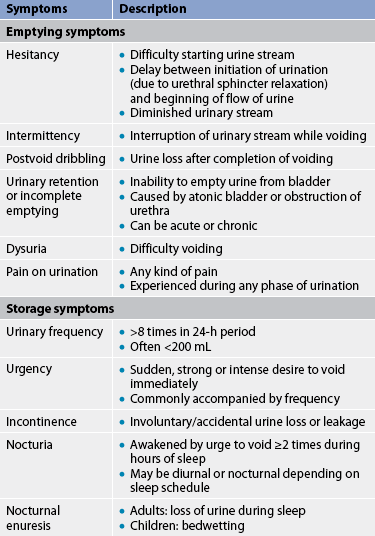

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are experienced in patients who have UTIs of the upper urinary tracts, as well as those confined to the lower tract.9 Symptoms are related to either bladder storage or bladder emptying. These symptoms are defined in Table 45-1. They include dysuria, frequent urination (more than every 2 hours), urgency and suprapubic discomfort or pressure. The urine may contain grossly visible blood (haematuria) or sediment, giving it a cloudy appearance. Flank pain, chills and the presence of a fever indicate an infection involving the upper urinary tract (pyelonephritis). People with significant bacteriuria may have no symptoms or may have non-specific symptoms such as fatigue or anorexia. (See Fig 45-2, which illustrates the mucosa of a person with acute cystitis.)

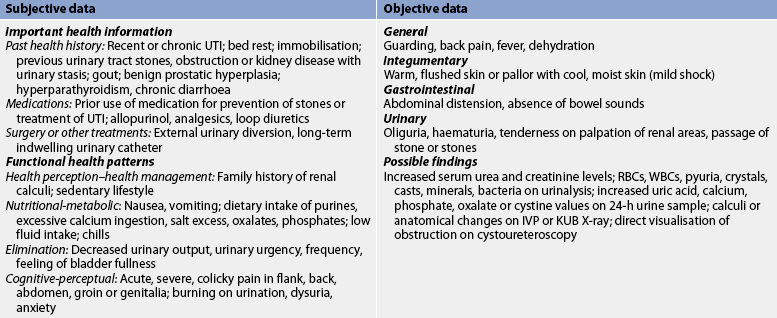

Figure 45-2 Acute cystitis. The mucosa of the bladder is red and swollen.

Source: Craft J, Gordon G, Tiziani A. Understanding pathophysiology. Sydney: Elsevier; 2011.

It is important to remember that these symptoms, considered characteristic of a UTI, are often absent in older adults. Older adults tend to experience non-localised abdominal discomfort rather than dysuria and suprapubic pain.10 In addition, they may have cognitive impairment or generalised clinical deterioration. Because older adults are less likely to experience a fever with a UTI, the value of body temperature as an indicator of a UTI is unreliable. Patients over the age of 80 years may experience a slight decline in temperature.

Multiple factors may produce LUTS similar to a UTI. For example, patients with bladder tumours or those receiving intravesical chemotherapy or pelvic radiation usually experience urinary frequency, urgency and dysuria. Interstitial cystitis, a chronic inflammatory condition of unknown aetiology, also produces urinary symptoms that are sometimes confused with a UTI.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Dipstick urinalysis should be obtained initially to identify the presence of nitrites (indicating bacteriuria), white blood cells (WBCs) and leucocyte esterase (an enzyme present in WBCs indicating pyuria). These findings can be confirmed by microscopic urinalysis.11 Following confirmation of bacteriuria and pyuria, a urine culture may be obtained. A urine culture is indicated in complicated or healthcare-associated UTIs, persistent bacteriuria or frequently recurring UTIs (more than two to three episodes per year). Urine may also be cultured when the infection is unresponsive to empirical therapy or the diagnosis is questionable.

A voided midstream technique yielding a clean-catch urine sample is preferred for obtaining a urine culture in most circumstances. Women should spread the labia and wipe the periurethral area from front to back using a moistened, clean gauze sponge (no antiseptic is used, as it could contaminate the specimen and cause false positives); then, keeping the labia spread, collect the specimen 1–2 seconds after voiding starts. Men should wipe the glans penis around the urethra and collect the specimen 1–2 seconds after voiding begins.

The urine should be refrigerated immediately on collection. The urine should be cultured within 24 hours of refrigeration. However, a specimen obtained by catheterisation or suprapubic needle aspiration provides more accurate results and may be necessary when an adequate clean-catch specimen cannot be readily obtained.

A urine culture is accompanied by sensitivity testing to determine the bacteria’s susceptibility to a variety of antibiotic drugs. The results of this test allow the healthcare provider to select an antibiotic known to be capable of destroying the bacterial strain producing a UTI in a specific patient.

Imaging studies of the urinary tract are indicated in selected cases. An intravenous pyelogram (IVP) or abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan may be obtained when obstruction of the urinary system is suspected of causing a UTI. In patients with recurrent UTIs, renal ultrasound is the preferred urinary tract imaging technique because it is non-invasive, easy to perform and relatively inexpensive. However, studies have shown that patients with symptoms can effectively diagnose their own UTIs and self-initiate treatments with the same success rate as medical practitioners.2,3

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE AND DRUG THERAPY

Once a UTI has been diagnosed, appropriate antimicrobial therapy is initiated. An antibiotic may be selected based on the health care provider’s best judgement (empirical therapy) or the results of sensitivity testing. The multidisciplinary care and drug therapy of cystitis are summarised in Box 45-3. Uncomplicated cystitis can be treated by a short-term course of antibiotics, typically for 1–3 days. In contrast, complicated UTIs require longer-term treatment, lasting 7–14 days or longer.2,5 Because many residents of long-term care facilities (approximately 30–50%), especially women, have chronic asymptomatic bacteriuria, the research literature suggests treating only symptomatic UTIs. Therefore, continued bacteriuria without clinical symptoms does not warrant repeat or continued antibiotic therapy.7

BOX 45-3 Urinary tract infection

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

Recurrent, uncomplicated UTI

Urine culture and sensitivity testing

Imaging study of urinary tract (if indicated)

Sensitivity-guided antibiotic therapy

Consider 3- to 6-month trial of suppressive or prophylactic antibiotic regimen

Consider postcoital antibiotic prophylaxis: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, cephalexin

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) or nitrofurantoin is often used to empirically treat uncomplicated or initial UTIs. TMP/SMX has the advantage of being relatively inexpensive and is taken twice daily. The disadvantage is that E. coli resistance to TMP/SMX is an increasing problem. Nitrofurantoin is normally given 3–4 times daily, but a long-acting preparation (Macrobid) is available that is taken twice daily. However, long-term use of nitrofurantoin can result in pulmonary fibrosis and neuropathies.3 Ampicillin and amoxicillin are not frequently selected when empirically treating a non-complicated UTI because they must be administered 3–4 times daily. In addition to these agents, the fluoroquinolones (including ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and gatifloxacin) may be used to treat complicated UTIs. In patients with UTIs secondary to fungi, amphotericin or fluconazole is the preferred therapy.

A number of over-the-counter or prescription drugs may be used in combination with antibiotic agents to relieve the discomfort associated with a UTI. Phenazopyridine is an over-the-counter drug that provides a soothing effect on the urinary tract mucosa. However, it stains the urine a reddish-orange that may be mistaken for blood in the urine and it may permanently stain underclothing. Although this drug is typically effective in relieving the transient acute discomfort associated with a UTI, patients should be advised to avoid long-term use of phenazopyridine because it can produce haemolytic anaemia. Combination agents such as Urised (methenamine, phenyl salicylate, methylene blue, benzoic acid, atropine and hyoscyamine) may also be used to relieve the symptoms associated with a UTI. Patients taking a combination agent such as Urised should be advised that preparations containing methylene blue are expected to tint the urine blue or green.

Prophylactic or suppressive antibiotics are sometimes administered to patients who experience repeated UTIs. A low dose of TMP/SMX, nitrofurantoin or another antibiotic may be administered on a daily basis in an attempt to prevent recurring UTIs, or a single dose may be taken before an event likely to provoke a UTI, such as sexual intercourse. Although suppressive therapy is often effective on a short-term basis, this strategy is limited because of the risk of antibiotic resistance, which ultimately leads to breakthrough infections with increasingly virulent pathogens.1,3

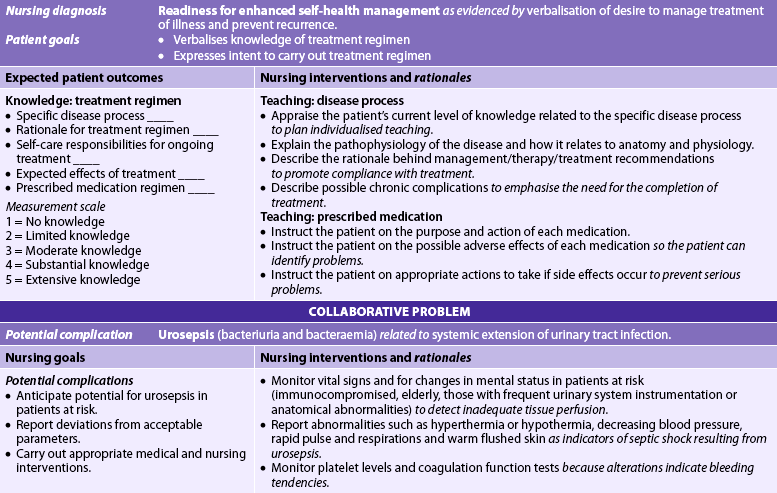

NURSING MANAGEMENT: URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

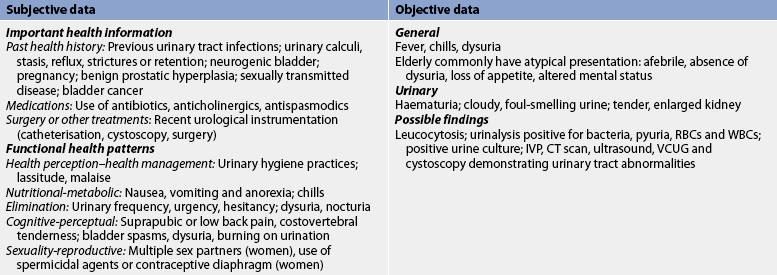

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with a UTI are presented in Table 45-2.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

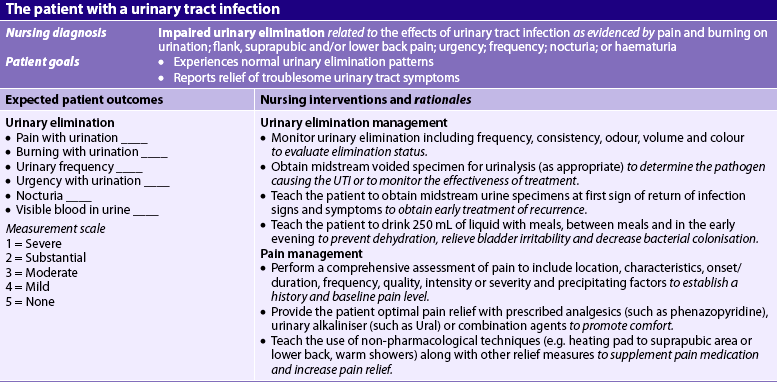

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with a UTI may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 45-1.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with a UTI will have: (1) relief from troublesome LUTS; (2) prevention of upper urinary tract involvement; and (3) prevention of recurrence.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

Health promotion measures include recognising individuals who are at risk for a UTI. Debilitated persons, older adults, patients who are immunocompromised due to comorbid diseases (e.g. cancer, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], diabetes mellitus) and patients treated with immunosuppressive drugs or corticosteroids are at high risk for UTIs. Health promotion activities, particularly for these individuals, can help decrease the frequency of infections and promote early detection of infection. Health promotion activities include teaching preventative measures such as: (1) emptying the bladder regularly and completely; (2) evacuating the bowel regularly; (3) wiping the perineal area from front to back after urination and defecation; and (4) drinking an adequate amount of liquid each day. The recommended daily liquid intake for the ambulatory adult is approximately 30 mL per kilogram of body weight per day. Thus a 75-kg person requires 2250 mL each day. Because the person will obtain approximately 20% of this fluid from food, this leaves 1800 mL to be obtained by drinking—or just over seven 250-mL glasses of fluid. Daily intake of cranberry juice or cranberry essence tablets may reduce the number of UTIs in women with recurrent UTIs.12 It is thought that enzymes found in cranberries inhibit the attachment of urinary pathogens (especially E. coli) to the bladder epithelium. Suppressive antibiotics are not generally recommended to prevent UTIs, but it is important to teach the patient to seek early treatment once symptoms occur.

The nurse has a major role in the prevention of HAIs. Avoiding unnecessary catheterisation and ensuring the early removal of indwelling catheters are the most effective means for reducing healthcare-associated UTIs. All patients undergoing instrumentation of the urinary tract are at risk for developing a healthcare-associated UTI. The nurse should always follow aseptic technique during these procedures. Washing hands before and after contact with each patient and wearing gloves for care involving the urinary system are especially important. When a catheter has been inserted, special measures should be used, as explained in the section on urethral catheterisation later in this chapter.

Routine and thorough perineal hygiene is important for all hospitalised patients, especially when a bedpan is used, following a bowel movement or if faecal incontinence is present. The nurse should answer patient calls quickly and offer the bedpan or urinal to bedridden patients at frequent intervals. These measures can prevent incontinence and decrease the number of incontinent episodes.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Acute intervention for a patient with a UTI includes ensuring adequate fluid intake if it is not contraindicated. It is sometimes difficult to get the patient to maintain an adequate fluid intake because the person may think it will worsen the discomfort and frequency associated with a UTI. Patients should be advised that fluids will increase the frequency of urination at first but they will also dilute the urine, making the bladder less irritable. Fluids will help flush out bacteria before they have a chance to colonise in the bladder. Caffeine, alcohol, citrus juices, chocolate and highly spiced foods or beverages should be avoided because they are potential bladder irritants.

Application of local heat to the suprapubic area or lower back may relieve the discomfort associated with a UTI. The patient can apply a heating pad (turned to its lowest setting) against the back or suprapubic area. A warm shower or sitting in a tub of warm water filled above the waist can also be effective in providing temporary relief.

The nurse should instruct the patient about the prescribed drug therapy, including side effects, and emphasise the importance of taking the full course of antibiotics. Often patients stop antibiotic therapy once symptoms disappear. This practice can lead to inadequate treatment and recurrence of infection, or to bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Sometimes a second drug or a reduced dose of drug is ordered after the initial course to suppress bacterial growth in patients susceptible to recurrent UTI. The patient should be instructed to watch for any changes in the colour or consistency of the urine and a decrease in or cessation of symptoms as a sign of the effectiveness of therapy. Patients should promptly report any of the following to their healthcare provider: (1) persistence of troublesome LUTS beyond the antibiotic treatment course; (2) onset of flank pain; or (3) fever.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

Home care for the patient with a UTI should emphasise the patient’s compliance with the drug regimen. The nurse’s responsibility is to teach the patient and carer about the need for ongoing care (see Box 45-4). This includes taking antimicrobial drugs as ordered, maintaining adequate daily fluid intake, regular voiding (approximately every 3–4 hours), urinating before and after intercourse, and temporarily discontinuing the use of a diaphragm.

BOX 45-4 Urinary tract infection

PATIENT & CAREGIVER TEACHING GUIDE

The following are important to teach the patient with a UTI to prevent recurrence.

1. Explain the importance of taking all antibiotics as prescribed. Symptoms may improve after 1 or 2 days of therapy, but organisms may still be present.

2. Instruct the patient on appropriate hygiene, including the following:

3. Explain the importance of emptying the bladder before and after sexual intercourse.

4. Instruct the patient to urinate regularly, approximately every 3 or 4 h during the day.

5. Instruct the patient to maintain adequate fluid intake.

6. Instruct the patient to avoid using vaginal douches and/or harsh soaps, bubble baths, powders and sprays in the perineal area.

7. Advise the patient to report symptoms or signs of recurrent UTI (e.g. fever, cloudy urine, pain on urination, urgency, frequency).

8. Suggest possible use of unsweetened cranberry juice (250 mL 3 times a day) or extract tablets 300–400 mg/day for UTI prevention.

The nurse should help the patient to understand the need for follow-up care if symptoms do not resolve, worsen or return once treatment is completed. Recurrent symptoms because of bacterial persistence or inadequate treatment typically occur within 1–2 weeks after completion of therapy. If the patient has been compliant with treatment, a relapse indicates the need for further evaluation.

Acute pyelonephritis

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

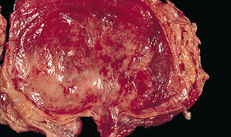

Pyelonephritis is an inflammation of the renal parenchyma (see Fig 45-3) and collecting system (including the renal pelvis). The most common cause is bacterial infection, but fungi, protozoa or viruses sometimes infect the kidney.13

Figure 45-3 Acute pyelonephritis. Cortical surface shows greyish white areas of inflammation and abscess formation.

Urosepsis is a systemic infection arising from a urological source. Its prompt diagnosis and effective treatment are critical because it can lead to septic shock and death in 15% of cases unless promptly eradicated. Septic shock is the outcome of unresolved bacteraemia involving a Gram-negative organism.14 (Septic shock is discussed in Ch 66.)

Pyelonephritis usually begins with colonisation and infection of the lower urinary tract via the ascending urethral route. Bacteria normally found in the intestinal tract, such as E. coli, Proteus, Klebsiella or Enterobacter species, frequently cause pyelonephritis. A pre-existing factor is often present, such as vesicoureteral reflux (retrograde or backward movement of urine from the lower to upper urinary tract) or dysfunction of lower urinary tract function such as obstruction from benign prostatic hyperplasia, a stricture or urinary stone. In residents of long-term care facilities, urinary tract catheterisation and the use of indwelling catheters is a common cause of pyelonephritis and urosepsis.

Acute pyelonephritis commonly starts in the renal medulla and spreads to the adjacent cortex. One of the most important risk factors for acute pyelonephritis is related to pregnancy-induced physiological changes in the urinary system.13,14 Recurring episodes of pyelonephritis, especially in the presence of obstructive abnormalities, can lead to a scarred, poorly functioning kidney(s) and a condition called chronic pyelonephritis.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The clinical manifestations of acute pyelonephritis vary from mild fatigue to the sudden onset of chills, fever, vomiting, malaise, flank pain and the LUTS characteristic of cystitis, including dysuria, urinary urgency and frequency. Costovertebral tenderness (costovertebral angle [CVA] pain) is typically present on the affected side. The clinical manifestations usually subside within a few days, even without specific therapy, but bacteriuria and pyuria usually persist.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Urinalysis shows pyuria, bacteriuria and varying degrees of haematuria. WBC casts may be found in the urine, indicating involvement of the renal parenchyma. A complete blood count will show leucocytosis and a shift to the left with an increase in immature neutrophils (bands). Urine cultures must be obtained when pyelonephritis is suspected. In patients with more severe illness who are hospitalised, blood cultures are also obtained.

Imaging studies, such as an IVP or CT scan, requiring intravenous (IV) injection of contrast materials are usually not obtained in the early stages of pyelonephritis to prevent the possible spread of infection. Alternatively, ultrasonography of the urinary system may be obtained to identify anatomical abnormalities, hydronephrosis, renal abscesses or the presence of an obstructing stone. Imaging studies are also used to assess for complications of pyelonephritis such as impaired renal function, scarring, chronic pyelonephritis or abscesses.

Urosepsis is characterised by bacteriuria and bacteraemia (presence of bacteria in blood). If bacteraemia is a possibility, close observation and vital sign monitoring are essential. Prompt recognition and treatment of septic shock may prevent irreversible damage or death.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE AND DRUG THERAPY

The diagnostic tests and collaborative therapy of acute pyelonephritis are summarised in Box 45-5. Patients with severe infections or complicating factors such as nausea and vomiting with dehydration require hospital admission.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative therapy

Mild symptoms (uncomplicated infection)

Outpatient management or short hospitalisation

Fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin

Severe symptoms

Oral antibiotics when patient tolerates oral intake

Adequate fluid intake (parenteral initially; switch to oral fluids as nausea, vomiting and dehydration subside)

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory or antipyretic drugs to reverse fever and relieve discomfort

The patient with mild symptoms may be treated as an outpatient with antibiotics for 14–21 days (see Box 45-5). Parenteral antibiotics are often given initially in the hospital to rapidly establish high serum and urinary drug levels. When initial treatment resolves acute symptoms and the patient is able to tolerate oral fluids and drugs, they may be discharged on a regimen of oral antibiotics for an additional 14–21 days. Symptoms and signs typically improve or resolve within 48–72 hours after starting therapy.15

Relapses may be treated with a 6-week course of antibiotics. Reinfections may be treated as individual episodes of disease or managed with long-term antibiotic therapy. Antibiotic prophylaxis may also be used for recurrent infections. The effectiveness of therapy is evaluated in accordance with the presence or absence of bacterial growth on urine culture.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE PYELONEPHRITIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE PYELONEPHRITIS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with pyelonephritis are similar to those for the patient with a UTI (see Table 45-2).

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with pyelonephritis include, but are not limited to, those for the patient with a UTI (see NCP 45-1).

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with pyelonephritis will have: (1) normal renal function; (2) normal body temperature; (3) no complications; (4) relief of pain; and (5) no recurrence of symptoms.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

Health promotion and maintenance measures are similar to those for UTI (see pp 1253–1255). In addition, it is important for the patient to receive early treatment for cystitis to prevent ascending infections. Because the patient with structural abnormalities of the urinary tract is at high risk for infection, the nurse should stress the need for regular medical care.

Acute intervention and home and ambulatory care

Acute intervention and home and ambulatory care

Nursing interventions vary depending on the severity of symptoms. These interventions include teaching the patient about the disease process with emphasis on: (1) the need to continue medications as prescribed; (2) the need for a follow-up urine culture to ensure proper management; and (3) identification of risk for recurrence or relapse (see Table 45-2 and NCP 45-1). In addition to antibiotic therapy, the patient should be encouraged to drink at least eight glasses of fluid every day, even after the infection has been treated. Rest is often indicated to increase patient comfort. The patient who has frequent relapses or reinfections may be treated with long-term, low-dose antibiotics. Understanding the rationale for therapy is important to enhance patient compliance.

Evaluation

Evaluation

The expected outcomes for the patient with pyelonephritis are the same as for UTI presented in NCP 45-1.

Chronic pyelonephritis

In chronic pyelonephritis the kidney has become small, atrophic and shrunken and has lost function owing to scarring or fibrosis.16 It is usually the outcome of recurring infections involving the upper urinary tract. However, it may also occur in the absence of an existing infection, recent infection or history of UTIs. Alternative terms used to describe this condition include interstitial nephritis, chronic atrophic pyelonephritis and reflux nephropathy (when scarring occurs in the presence of vesicoureteral reflux).

Radiological imaging and histological testing, rather than clinical features, are used to confirm the diagnosis of chronic pyelonephritis. Imaging studies reveal a small, contracted kidney with a thinned parenchyma. The collecting system may be small or hydronephrotic. Pathological analysis reveals loss of functioning nephrons, infiltration of the parenchyma with inflammatory cells and fibrosis.

The level of renal function in chronic pyelonephritis varies depending on whether one or both kidneys are affected, the magnitude of scarring and the presence of coexisting infection. Chronic pyelonephritis often progresses to end-stage kidney disease when both kidneys are involved, even if the underlying infection is successfully eradicated. Nursing and collaborative management of the patient with chronic kidney disease is discussed in Chapter 46.

Urethritis

Urethritis is an inflammation of the urethra. Causes of urethritis include a bacterial or viral infection, Trichomonas and Candida infection (especially in women), Chlamydia and gonorrhoea (especially in men).

Among men, the causes of urethritis are usually sexually transmitted. Purulent discharge usually indicates a gonococcal urethritis, whereas a clear discharge typically signifies a non-gonococcal urethritis.17 (Sexually transmitted infections are discussed in Ch 52.) Urethritis also produces troublesome LUTS, including dysuria, urgency and frequent urination, similar to those seen with cystitis.

In women, urethritis is difficult to diagnose. It frequently produces troublesome symptoms as described previously, but urethral discharge may not be present. Cultures on split urine collections (taken at the beginning of urine flow and then midstream) or any urethral discharge may confirm a diagnosis of urethral infection.

Treatment is based on identifying and treating the cause and providing symptomatic relief. Drugs used for bacterial infections include trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and nitrofurantoin. Metronidazole may be used for treating Trichomonas. Drugs such as nystatin or fluconazole may be prescribed for Candida infections. In Chlamydia infections, doxycycline may be used. Women with negative urine cultures and no pyuria do not usually respond to antibiotics. Warm sitz baths may temporarily relieve troublesome symptoms. The patient should be instructed to avoid the use of vaginal deodorant sprays, to properly cleanse the perineal area after bowel movements and urination, and to avoid sexual intercourse until symptoms subside. Patients with sexually transmitted urethritis should refer their sex partners for evaluation and testing if they had sexual contact in the 60 days preceding onset of their symptoms or diagnosis.

Urethral diverticula

Urethral diverticula are the result of obstruction and subsequent rupture of the periurethral glands into the urethral lumen with epithelialisation (regrowth of tissue) over the opening of the resulting periurethral cavity.18 Women have a 1–5% incidence of urethral diverticuli, and they have a higher incidence than men. The rare cases reported in males generally have been associated with lower urinary tract congenital anomalies or surgical trauma. The periurethral glands are found along the entire length of the urethra, with the majority draining into the distal third of the urethra. Skene’s glands are the largest and most distal of these glands. Urethral diverticula mostly occur in the area of these glands. In many cases, a person may have more than one diverticulum. Causes include urethral trauma from childbearing, urethral instrumentation, dilation and infection with gonococcal organisms. Urethral diverticula present some of the more challenging diagnostic and reconstructive cases in urology.

Symptoms include dysuria, postvoid dribbling, frequent urination (more often than every 2 hours), urgency, suprapubic discomfort or pressure, dyspareunia and a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying. Urinary incontinence is frequently seen. However, one in four women may have no symptoms.

The urine may contain gross haematuria or sediment, giving it a cloudy appearance. An anterior vaginal wall mass may be noted on physical examination. When palpated, it may be quite tender and express purulent discharge through the urethra. Radiographic studies such as voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) should be used to confirm the diagnosis. Additional studies include ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to determine the size of the diverticulum in relation to the urethral lumen.

Surgical options include transurethral incision of the diverticular neck, marsupialisation (creation of a permanent opening) of the diverticular sac into the vagina (often referred to as a Spence procedure) and surgical excision. Surgical excision of a urethral diverticulum should be performed with caution as the diverticular sac may be adherent to the adjacent urethral lumen, and careless excision of the sac may result in a large urethral defect requiring construction of a neourethra (new urethra). Other important considerations during surgery include identification and closure of the diverticular neck, complete removal of the mucosal lining of the diverticular sac to prevent recurrence, and a multiple-layered closure to prevent postoperative urethrovaginal fistula formation. Stress urinary incontinence may be a complication of the surgery.

Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a chronic, painful inflammatory disease of the bladder characterised by symptoms of urgency/frequency and pain in the bladder and/or pelvis. Painful bladder syndrome (PBS) is suprapubic pain related to bladder filling. It occurs with other symptoms such as frequency, but the patient does not have a UTI or other obvious pathology.19

IC/PBS affects approximately 5% of the Australian and New Zealand population. The average age at onset is 40 years. The ratio of women to men with IC/PBS is 10:1 to 12:1. Although the aetiology remains unknown, a contributing factor is chronic inflammation with mast cell invasion of the bladder wall (possibly provoked by an infection or an autoimmune disorder). Other aetiological factors include defects of the glycosaminoglycan layer that protects the bladder mucosa from the irritating effects of urine exposure, abnormal constituents in the urine, dysfunction of the sympathetic innervation of the lower urinary tract and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.

The two primary clinical manifestations that characterise IC/PBS are pain and troublesome LUTS (e.g. frequency, urgency). The pain associated with IC/PBS is usually located in the suprapubic area but may involve the vagina, labia or entire perineal region. It varies from moderate to severe in intensity and is exacerbated by bladder filling, postponing urination, physical exertion, pressure against the suprapubic area, eating certain foods and emotional distress. The pain is transiently relieved by urination. Troublesome LUTS are similar to a UTI, and the condition is often misdiagnosed as a recurring or chronic UTI or, in men, chronic prostatitis. The pain and troublesome voiding symptoms produced by IC/PBS remit and exacerbate over time. Women will report that pain occurs premenstrually and is aggravated by sexual intercourse and/or emotional stress. Some patients experience an onset of symptoms that disappears altogether after a period of weeks to months, whereas others have persistent symptoms over a period of months to years.

IC/PBS is a diagnosis of exclusion. The condition is suspected whenever a patient experiences symptoms of a UTI despite the absence of bacteriuria, pyuria or a positive urine culture (see Box 45-6). A careful history and physical examination are necessary to exclude a variety of disorders that may produce somewhat similar symptoms, such as UTI or endometriosis. This evaluation must include at least one negative urine culture during a period of active symptoms. In IC, cystoscopic examination may reveal a small bladder capacity and superficial ulcerations with bladder filling called glomerulations, but these findings are frequently absent in PBS.

BOX 45-6 Criteria for the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE AND DRUG THERAPY

Because the aetiology of IC/PBS is unknown, no single treatment has been identified that consistently reverses or relieves symptoms. Various therapies have been effective in alleviating or relieving troublesome symptoms in most patients.20

Dietary and lifestyle alterations are used to relieve pain and diminish voiding frequency and nocturia.20 Dietary alterations include eliminating foods and beverages likely to exacerbate the symptoms. A diet low in acidic foods and avoiding beverages such as coffee, tea and carbonated and alcoholic drinks can be helpful in reducing IC/PBS symptoms. An over-the-counter dietary supplement called calcium phosphorus alkalinises the urine and can provide relief from the irritating effects of certain foods. This agent may be particularly helpful when dining away from home, where the patient has less control over the preparation of foods. Stress can exacerbate or cause flare-ups of IC/PBS symptoms, so basic relaxation techniques (e.g. sitz baths, application of heat or cold to the perineum or bladder, stress reduction tapes) may be helpful. Use of lubrication or altering positions may decrease the pain associated with sexual intercourse.

Two tricyclic antidepressants, amitriptyline and nortriptyline, are used to reduce the burning pain and urinary frequency. Pentosan is the only oral agent approved for the treatment of patients with symptoms of IC. It is used to enhance the protective effects of the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder and is thought to relieve pain associated with IC/PBS by reducing the irritative effects of urine on the bladder wall.22,21 These drugs are effective over time (weeks to months), but they do not provide immediate relief that may be needed when a patient experiences an acute exacerbation of symptoms. For immediate relief, a short course of opioid analgesics may be given.

Several agents may be instilled directly into the bladder through a small catheter. Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to act by desensitising pain receptors in the bladder wall. Heparin and hyaluronic acid also may be instilled into the bladder to relieve symptoms. Like pentosan, these agents are thought to enhance the protective properties of the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder. Instillations are often administered with lignocaine, which rapidly desensitises the bladder wall, rendering the patient better able to tolerate instillation of additional heparin or hyaluronic acid and providing transient relief from pain. Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), an attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, administered intravesically is a common treatment for IC. The mechanism of action of BCG is unclear, but it may alleviate a possible autoimmune disorder provoking the chronic inflammation characteristic of the disorder.21

Distension of the bladder during endoscopic examination relieves IC/PBS-related pain, urgency and voiding frequency, probably by temporarily disrupting sensory nerve endings in the bladder wall. Several surgical procedures have been used in an attempt to relieve severe, debilitating pain.21 Surgical urinary diversion, such as an ileal conduit, is an approach that can be used when other measures fail. Unfortunately, some patients have reported pain within the urinary diversion, possibly indicating that components of the urine may contribute to IC/PBS in certain cases.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS/PAINFUL BLADDER SYNDROME

NURSING MANAGEMENT: INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS/PAINFUL BLADDER SYNDROME

Assessment focuses on characterisation of the pain associated with IC/PBS. The nurse should ask the patient about specific dietary or lifestyle factors known to exacerbate or alleviate pain and about the intensity of the pain.21 Objective data collection includes a bladder log or voiding diary kept over a period of at least 3 days to determine voiding frequency and patterns of nocturia. A simultaneous pain record may be useful.

Reassurance that IC/PBS is a real condition experienced by others and that it can be effectively treated may relieve the anxiety, anger, guilt and frustration related to experiences of chronic pain and voiding dysfunction in the absence of a clear-cut diagnosis and treatment strategy. A UTI may occur during the course of IC/PBS management due to diagnostic instrumentation and frequent bladder instillations. A UTI is likely to produce an acute exacerbation of troublesome LUTS and urinary frequency, as well as dysuria (not typically associated with IC/PBS) and odorous urine, possibly with haematuria.

The patient should be instructed about the need to maintain good nutrition, particularly in the light of the broad dietary restrictions often necessary to control IC-related pain. Specifically, the patient should be advised to take a multivitamin containing no more than the recommended dietary allowance for essential vitamins and to avoid high-potency vitamins because these formulations may irritate the bladder. The nurse can assist the patient to obtain information from the Interstitial Cystitis Support Group found in both New Zealand and Australia (see the Resources on p 1291), which includes recipes and menus for a well-balanced diet that is specifically designed to avoid bladder-irritating foods and beverages.

Eliminating a variety of foods and beverages from the diet that are likely to irritate the bladder typically provides modest to profound relief from symptoms. Typical bladder irritants include caffeine, alcohol, citrus products, aged cheeses, nuts and foods containing vinegar, curries or hot peppers, as well as foods or beverages likely to lower urinary pH. In addition, the patient should use sodium citrotartrate and avoid wearing clothes that create suprapubic pressure, including pants with tight belts or restrictive waistlines.21

Written educational materials concerning diet, coping with the need for frequent urination and strategies for coping with the emotional burden of IC/PBS are available from the Interstitial Cystitis Support Group. Providing these materials gives the nurse an excellent opportunity to introduce the patient to the existence of this patient advocacy group and to the possibility of participating in local support groups.

Renal tuberculosis

Renal tuberculosis (TB) is rarely a primary lesion. It is usually secondary to TB of the lung. In a small percentage of patients with pulmonary TB, the tubercle bacilli reach the kidneys via the bloodstream. Onset occurs 5–8 years after the primary infection. The patient is often asymptomatic when the kidney is initially infiltrated with bacilli. Sometimes the patient complains of fatigue and develops a low-grade fever. As the lesions ulcerate, infection descends to the bladder and other genitourinary organs, and the patient experiences cystitis, frequent urination, burning on voiding and epididymitis (in men).22

Symptoms of a UTI are the first sign in the majority of patients with renal TB. Renal lesions may calcify as they heal. Infrequently, renal colic, lumbar and iliac pain, and haematuria may be present. A diagnosis is based on localisation of tubercle bacilli in the urine and on IVP findings.

Long-term complications of renal TB depend on the duration of the disease before treatment. Scarring of the renal parenchyma and the development of ureteral strictures occur. The earlier treatment is initiated, the less likely kidney failure will develop. Reduced bladder volume may be irreversible in advanced disease. The patient may require long-term urological follow-up. Nursing and collaborative management for the patient with TB is discussed in Chapter 27.

Glomerulonephritis

Immunological processes involving the urinary tract predominantly affect the renal glomerulus. The disease process results in glomerulonephritis (inflammation of the glomeruli), which affects both kidneys equally and is the second leading cause of renal failure in Australia and New Zealand.23 Although the glomerulus is the primary site of inflammation, tubular, interstitial and vascular changes also occur. Glomerulonephritis is divided into a number of classifications, which may describe: (1) the extent of damage (diffuse or focal); (2) the initial cause of the disorder (systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis [scleroderma], streptococcal infection); or (3) the extent of changes (minimal or widespread). The major glomerular disorders seen in Australia and New Zealand are IgA mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, focal sclerosing glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome.23

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Two types of antibody-induced injury can initiate glomerular damage. In the first type, the antibodies have specificity for antigens within the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). These are termed anti-GBM antibodies. Immunoglobulins and complement are deposited along the basement membrane. The mechanism that causes a person to develop antibodies against their own GBM is not known. Production of autoantibodies (antibodies to one’s own tissue) may be stimulated by a structural alteration in the GBM or by a reaction of the basement membrane with an exogenous agent (e.g. hydrocarbon, viruses).

In the second type, the antibodies react with circulating non-glomerular antigens and are randomly deposited as immune complexes along the GBM. On electron microscopy of renal tissue sections, the deposits appear ‘lumpy-bumpy’. In this immune complex process, the antigens do not come from the glomeruli but rather from either endogenous circulating native deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or exogenous sources (e.g. bacteria, viruses, chemicals, drugs). Bacterial products appear to be important in post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis. Viral agents have been recognised in rare cases of glomerulonephritis that developed after hepatitis B or C and rubella.

All forms of immune complex disease are characterised by an accumulation of antigen, antibody and complement in the glomeruli, which can result in tissue injury. The immune complexes activate complement (see Chs 12 and 13). Complement activation results in the release of chemotactic factors that attract polymorphonuclear leucocytes, histamine and other inflammatory mediators. The end result of these processes is glomerular injury.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Clinical manifestations of glomerulonephritis include varying degrees of haematuria (ranging from microscopic to gross) and urinary excretion of various formed elements, including red blood cells (RBCs), WBCs and casts. Proteinuria and elevated serum urea and creatinine levels are other manifestations. In most cases, recovery from the acute illness is complete. However, if progressive involvement occurs, the result is destruction of renal tissue and marked renal insufficiency.

The patient’s history provides important information related to glomerulonephritis. It is necessary to assess exposure to drugs, immunisations, microbial infections and viral infections such as hepatitis. It is also important to evaluate the patient for more generalised conditions involving immune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis.

IgA mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis

IgA mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis (IgAGN) is most common in young men, but all age groups can be affected. It is the most common type of glomerulonephritis worldwide.24 IgAGN develops due to the deposition of the antibody immunoglobulin A (IgA) in the glomerular mesangium often following a respiratory tract infection. The deposited IgA causes an inflammatory response that affects the permeability of the glomerulus. This results in the development of haematuria, proteinuria and hypertension. The disease can range from a benign condition to a rapidly progressive form of glomerulonephritis. Early diagnosis with a renal biopsy can lead to early intervention to slow the progression of the disease.

Acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

Acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN) is most common in children and young adults, but all age groups can be affected.25 There is a high incidence of streptococcal skin and throat infections in Indigenous Australians, which is believed to contribute to the high numbers of Indigenous people with APSGN. APSGN develops 5–21 days after an infection of the tonsils, pharynx or skin (e.g. streptococcal sore throat, impetigo) by nephrotoxic strains of group A β-haemolytic streptococci. The person produces antibodies to the streptococcal antigen. Although the specific mechanism is not known, tissue injury occurs as the antigen-antibody complexes are deposited in the glomeruli and complement is activated. Complement activation causes an inflammatory reaction to the injury. The response to the injury is also a decrease in the filtration of metabolic waste products from the blood and an increase in the permeability of the glomerulus to larger protein molecules.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

The clinical manifestations of APSGN appear as a variety of signs and symptoms. Generalised body oedema, hypertension, oliguria, haematuria with a smoky or rusty appearance and proteinuria may occur. Fluid retention occurs as a result of decreased glomerular filtration. The oedema appears initially in low-pressure tissues, such as around the eyes (periorbital oedema), but later progresses to involve the total body as ascites or peripheral oedema in the legs. Smoky urine indicates bleeding in the upper urinary tract. The degree of proteinuria varies with the severity of the glomerulonephropathy. Hypertension primarily results from increased extracellular fluid volume. The patient with APSGN may have abdominal or flank pain. At times the patient has no symptoms, with the problem found on routine urinalysis.

More than 95% of patients with APSGN recover completely or improve rapidly with conservative management. Accurate recognition and assessment is critical as chronic glomerulonephritis develops in 5–15% of affected people and irreversible kidney failure occurs in 1% of patients.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The diagnosis of APSGN is based on a complete history and physical examination and laboratory studies (see Box 45-7) to determine the presence or history of a group A β-haemolytic streptococcus in a throat or skin lesion. An immune response to the streptococcus is often demonstrated by assessment of antistreptolysin-O (ASO) titres. The finding of decreased complement components (especially C3 and CH50) indicates an immune-mediated response. A renal biopsy may be performed to confirm the presence of the disease.

Dipstick urinalysis and urine sediment microscopy will reveal the presence of erythrocytes in significant numbers. Erythrocyte casts are highly suggestive of APSGN. Proteinuria may range from mild to severe. Screening blood tests include serum urea and creatinine to assess the extent of kidney impairment.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ACUTE POST-STREPTOCOCCAL GLOMERULONEPHRITIS

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ACUTE POST-STREPTOCOCCAL GLOMERULONEPHRITIS

The management of APSGN focuses on symptomatic relief (see Box 45-7). Rest is recommended until the signs of glomerular inflammation (proteinuria, haematuria) and hypertension subside. Oedema is treated by restricting sodium and fluid intake and by administrating diuretics. Severe hypertension is treated with antihypertensive drugs. Dietary protein intake may be restricted if there is evidence of an increase in nitrogenous wastes (e.g. elevated urea value). The restriction varies with the degree of proteinuria. Low-protein, low-sodium, fluid-restricted diets are discussed in Chapter 46.

Antibiotics should be given only if the streptococcal infection is still present. Corticosteroids and cytotoxic drugs have not been shown to be of value in the treatment of APSGN.

One of the most important ways to prevent the development of APSGN is to encourage early diagnosis and treatment of sore throats and skin lesions. If streptococci are found in the culture, treatment with appropriate antibiotic therapy (usually penicillin) is essential. The patient must be encouraged to take the full course of antibiotics to ensure that the bacteria have been eradicated. Good personal hygiene is an important factor in preventing the spread of cutaneous streptococcal infections.

Goodpasture’s syndrome

Goodpasture’s syndrome, an example of cytotoxic (type II) autoimmune disease, is characterised by the presence of circulating antibodies against glomerular and alveolar basement membrane and is a rare autoimmune disease.25 Although the primary target organ is the kidneys, the lungs are also involved. Damage to the kidneys and lungs results when binding of the antibody causes an inflammatory reaction mediated by complement fixation and activation (see Chs 12 and 13). The causative factors for development of autoantibody production are unknown, although type A influenza viruses, hydrocarbons, penicillamine and unknown genetic factors may be involved.

Goodpasture’s syndrome is seen mostly in young male smokers. The clinical manifestations include flu-like symptoms with pulmonary symptoms that include cough, mild shortness of breath, haemoptysis, crackles, rhonchi and pulmonary insufficiency. Renal involvement causes haematuria, weakness, pallor, anaemia and kidney failure. Pulmonary haemorrhage usually occurs and may precede glomerular abnormalities by weeks or months. Abnormal diagnostic findings include low haematocrit and haemoglobin levels, elevated serum urea and creatinine levels, haematuria and proteinuria. Circulating serum anti-GBM antibodies parallel the activity of the kidney disease and are diagnostic of this syndrome.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: GOODPASTURE’S SYNDROME

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: GOODPASTURE’S SYNDROME

Until recently, the prognosis for the patient with Goodpasture’s syndrome was poor, with a mean survival time of less than 4 months. Current management with corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. cyclophosphamide, azathioprine), plasmapheresis (see Ch 13) and dialysis has reduced the mortality rate to less than 20%.26

Plasmapheresis removes the circulating anti-GBM antibodies, and immunosuppressive therapy inhibits further antibody production. Kidney transplantation can be attempted after the circulating anti-GBM antibody titre decreases. Although recurrences may develop, the disease is not a contraindication to transplantation. In selected patients with severe pulmonary haemorrhage, bilateral nephrectomy has been helpful. The exact mechanism for improvement has not been determined.

Nursing management appropriate for a critically ill patient who is experiencing symptoms of acute kidney injury and respiratory distress is instituted. Death is often secondary to haemorrhage in the lungs and respiratory failure. (Nursing interventions for a patient in acute kidney injury are discussed in Ch 46, and nursing interventions for a patient with respiratory failure are discussed in Ch 67.) Because this syndrome is rare and primarily affects previously healthy young adults, support and understanding of the patient and family are of major importance. The patient and family need instructions concerning current therapy, drugs and complications of the disease process.

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) is glomerular disease associated with acute kidney injury where there is rapid, progressive loss of kidney function over days to weeks. Kidney failure may occur within weeks to months, in contrast to chronic glomerulonephritis, which develops insidiously and progresses over many years. The manifestations of RPGN are hypertension, oedema, proteinuria, haematuria and RBC casts.

RPGN can occur in a variety of situations: (1) as a complication of inflammatory or infectious disease (e.g. APSGN); (2) as a complication of a multisystemic disease (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus, Goodpasture’s syndrome); (3) as an idiopathic disease; or (4) with the use of certain drugs (e.g. penicillamine).

Prompt diagnosis and treatment is directed towards correction of fluid overload, hypertension, uraemia and inflammatory injury to the kidney. Treatment includes corticosteroids, cytotoxic agents and plasmapheresis. Dialysis therapy and transplantation are used as maintenance therapy for the patient with RPGN. Following kidney transplantation, RPGN may recur.

Chronic glomerulonephritis

Chronic glomerulonephritis is a syndrome that reflects the end stage of glomerular inflammatory disease. Most types of glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome can eventually lead to chronic glomerulonephritis.

The syndrome is characterised by proteinuria, haematuria and the slow development of uraemia (see Ch 46) as a result of decreasing kidney function. Chronic glomerulonephritis progresses insidiously towards kidney failure over a few to as many as 30 years.

Chronic glomerulonephritis is often found coincidentally when an abnormality on a urinalysis or elevated blood pressure is detected. It is common to find that the patient has no recollection or history of acute nephritis or any renal problems. A renal biopsy may be performed to determine the exact cause and nature of the glomerulonephritis. However, ultrasound and CT scanning are generally preferred as diagnostic measures.

Treatment is supportive and symptomatic. Hypertension and UTIs are treated vigorously. Protein and phosphate restrictions may slow the progression of kidney disease. Management of chronic kidney disease is discussed in Chapter 46.

Nephrotic syndrome

AETIOLOGY AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Nephrotic syndrome results when the glomerulus is excessively permeable to plasma protein, causing proteinuria that leads to low plasma albumin and tissue oedema. Some of the more common causes of nephrotic syndrome are listed in Box 45-8. In adults about one-third of patients with nephrotic syndrome have a systemic disease such as diabetes mellitus or systemic lupus erythematosus. The remainder are categorised as having idiopathic nephrotic syndrome.27

The characteristic manifestations include peripheral oedema, massive proteinuria, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and hypoalbuminaemia. Characteristic blood chemistry results include decreased serum albumin, decreased total serum protein and elevated serum cholesterol. The increased glomerular membrane permeability found in nephrotic syndrome is responsible for the massive excretion of protein in the urine. This results in decreased serum protein and subsequent oedema formation. Ascites and anasarca (massive generalised oedema) develop if there is severe hypoalbuminaemia.

The diminished plasma oncotic pressure from the decreased serum proteins stimulates hepatic lipoprotein synthesis, which results in hyperlipidaemia. Initially, cholesterol and low-density lipoproteins are elevated. Later, the triglyceride level is also increased. Fat bodies (fatty casts) commonly appear in the urine.

Immune responses, both humoral and cellular, are altered in nephrotic syndrome. As a result, infection is a primary cause of morbidity and mortality. Calcium and skeletal abnormalities may occur, including hypocalcaemia, blunted calcaemic response to parathyroid hormone, hyperparathyroidism and osteomalacia.

With nephrotic proteinuria, loss of clotting factors can result in a relative hypercoagulable state. Hypercoagulability with thromboembolism is a serious complication of nephrotic syndrome. The renal vein is the most common site for thrombus formation. Pulmonary emboli occur in about 40% of nephrotic patients with thrombosis.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: NEPHROTIC SYNDROME

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: NEPHROTIC SYNDROME

Treatment of nephrotic syndrome is based on symptom management.27 The goals are to relieve oedema and cure or control the primary disease. Management of oedema includes the cautious use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and a low-sodium (2–3 g/day), low-to-moderate protein (0.5–0.6 g/kg/day) diet. Dietary salt restrictions are a key to managing oedema. In some individuals, thiazide or loop diuretics may be needed. If urine protein loss exceeds 10 g/day, additional dietary protein may be needed.

The treatment of hyperlipidaemia is often unsuccessful. However, treatment with lipid-lowering agents, such as colestipol and simvastatin, may result in moderate decreases in serum cholesterol levels. If thrombosis is detected, anticoagulant therapy may be necessary for up to 6 months.

Corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide may be used for the treatment of severe cases of nephrotic syndrome. Prednisolone has been effective to varying degrees in patients with early-stage nephrosis, membranous glomerulonephritis, proliferative glomerulonephritis and lupus nephritis. Management of diabetes and treatment of oedema are the only measures used for nephrotic syndrome related to diabetes.

A major nursing intervention for the patient with nephrotic syndrome is related to oedema. It is important to assess the oedema by weighing the patient daily, accurately recording intake and output and measuring abdominal girth or extremity size. Comparing this information daily provides the nurse with a tool for assessing the effectiveness of treatment. The oedematous skin should be cleaned carefully and trauma should be avoided. The nurse also needs to monitor the effectiveness of diuretic therapy.

The patient with nephrotic syndrome has the potential to become malnourished from the excessive loss of protein in the urine. Maintaining a low-to-moderate protein diet that is also low in sodium is not always easy. The patient is usually anorexic, but serving small, frequent meals in a pleasant setting may encourage better dietary intake. The patient will also be susceptible to infection, so it is important to take measures to avoid exposure to persons with known infections. Providing support for the patient, in terms of coping with an altered body image, is essential, because patients are often embarrassed and ashamed by their oedematous appearance.

OBSTRUCTIVE UROPATHIES

Urinary obstruction refers to any anatomical or functional condition that blocks or impedes the flow of urine (see Fig 45-4). It may be congenital or acquired.

Damaging effects from urinary tract obstruction affect the system above the level of the obstruction. The severity of these effects depends on the location, the duration of obstruction, the amount of pressure or dilation, the presence of urinary stasis and whether infection is present. Infection increases the risk of irreversible damage.

Although obstruction distal to the prostate in men or the bladder neck in women causes mucosal scarring and a slower urinary stream, it rarely results in major obstructive uropathy because the urethral wall pressure is less than that of the bladder neck and bladder. Urethral obstruction may contribute to outlet resistance and cause lower or upper urinary tract damage when other obstructive or dysfunctional factors are also present. For example, there is an increased risk of compromised kidney function in the patient with a spinal cord injury with vesicosphincter dyssynergia.

When obstruction occurs at the level of the bladder neck or prostate, significant bladder changes can occur. Detrusor muscle fibres hypertrophy (increase in size) to contract harder to push urine out of a narrower pathway. Over a long period, the detrusor loses its ability to compensate for this resistance. Muscle bundles separate and become less compliant. This separation is called trabeculation. Trabeculation is caused by the deposition of collagen in the bladder wall that separates the smooth muscle fascicles. Trabeculation may hasten the decompensation of the detrusor. The areas between these muscle bundles are called cellules. Because these areas have no muscle support, the bladder mucosa can herniate between detrusor muscle bundles, forming sacs that drain poorly, called diverticula. Residual urine volume can be very high in a non-compensating bladder.

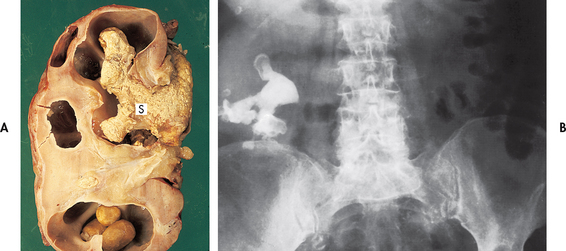

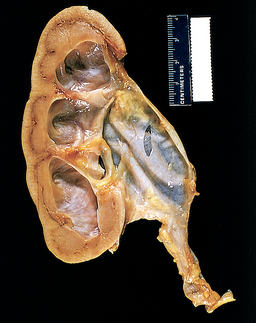

Pressure increases during bladder filling or storage and can be transmitted to the ureter when bladder outlet obstruction is present. This pressure overcomes the normal peristaltic pressure and leads to reflux (a backflow of urine); ureteral dilation, kinking and tortuosity; hydroureter (dilation of the renal pelvis); vesicoureteral reflux (backflow or backward movement of urine from the lower to upper urinary tracts); and hydronephrosis (dilation or enlargement of the renal pelvises and calyces; see Fig 45-5) and consequent chronic pyelonephritis and renal atrophy. If only one kidney is obstructed, the other kidney may try to compensate by hypertrophy, but the ureter will not be dilated on this contralateral side.

Figure 45-5 Hydronephrosis of the kidney. Note the marked dilation of the pelvis and calyces and thinning of the renal parenchyma.

Partial obstruction may occur in the ureter or at the pelvicouteric junction (PUJ). If the pressure remains low or moderate, the kidney may continue to dilate with no noticeable loss of function. There is an increased risk of pyelonephritis because of urinary stasis and reflux. If only one kidney is involved and the other kidney is functioning, the patient may be free of symptoms. If both kidneys are involved, or only one functioning kidney is involved (e.g. if the patient has only one kidney), alterations in kidney function (e.g. increased serum urea and creatinine levels) are found. Progressive obstruction can lead to the development of oliguria or anuria. Often, episodes of oliguria are followed by polyuria if the obstruction is a stone that becomes dislodged. Treatment requires location and relief of the blockage. This can include insertion of a tube (e.g. urethral or ureteral), surgical correction of the disease process or diversion of the urinary stream above the level of blockage.

Urinary tract calculi

It is hypothesised that Australia’s hot, dry climate causes more stone formation than occurs in many other countries in the world.28 Nephrolithiasis (kidney stone disease) is common and many people require hospitalisation. Except for struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) stones associated with UTI, stone disorders are more common in men than in women. The majority of patients are between 20 and 55 years of age. The incidence is also higher in people with a family history of stone formation. Recurrence of stones can occur in up to 50% of patients.28 Stone formation occurs more often in the summer months, thus supporting the role of dehydration in this process. Kidney stone formation also seems to increase in incidence as countries become more industrialised, whereas the incidence of bladder stones decreases.

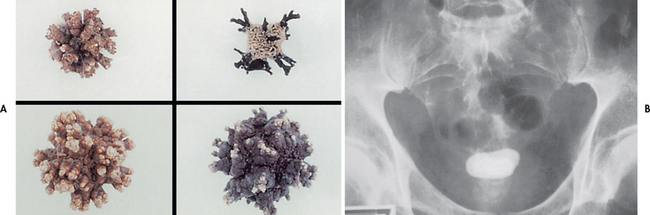

TYPES

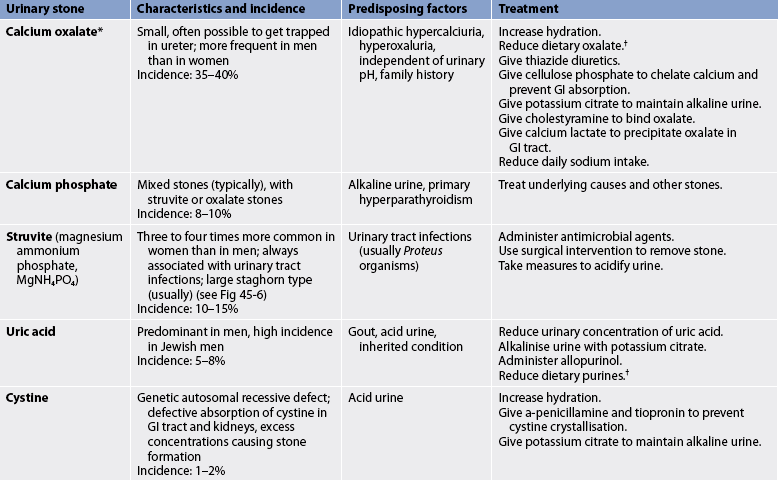

The term calculus refers to the stone, and lithiasis refers to stone formation. The five major categories of stones are: (1) calcium phosphate; (2) calcium oxalate; (3) uric acid; (4) cysteine; and (5) struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate; see Table 45-3). Stone composition may be mixed, although calcium stones are the most common. Calculi can be found in various locations in the urinary tract (see Figs 45-6 and 45-7).

TABLE 45-3 Types of urinary tract calculi

* Calcium stones can exist as calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate, or a mixture of both. Calcium stones account for the majority of all stones.

† See Box 45-10.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Many factors are involved in the incidence and type of stone formation, including metabolic, dietary, climatic, genetic, lifestyle and occupational influences (see Box 45-9). Although many theories have been proposed, no single theory can account for stone formation in all cases. Crystals, when in a supersaturated concentration, can precipitate and unite to form a stone. Keeping urine dilute and free flowing reduces the risk of recurrent stone formation in many individuals. A mucoprotein is formed (the matrix for the stone) in kidneys that form stones. Urinary pH, solute load and inhibitors in the urine affect the formation of stones. The higher the pH (alkaline), the less soluble are calcium and phosphate. The lower the pH (acidic), the less soluble are uric acid and cystine.

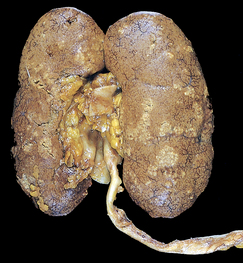

Other important factors in the development of stones include obstruction with urinary stasis and urinary tract infection with urea-splitting bacteria (e.g. Proteus, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas and some species of staphylococci). These bacteria cause the urine to become alkaline and contribute to the formation of struvite stones.28 Infected stones, entrapped in the kidney (see Fig 45-6), may assume a staghorn configuration as the stone branches to occupy a large portion of the collecting system. These stones can lead to a renal infection, hydronephrosis and loss of kidney function.29 Infected stones are frequent in the patient with an external urinary diversion, long-term indwelling catheter, neurogenic bladder or urinary retention. Genetic factors may also contribute to urine stone formation. Cystinuria, an autosomal recessive disorder, is characterised by a marked increase in the excretion of cystine.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Urinary stones cause clinical manifestations when they obstruct urinary flow. Common sites of complete obstruction are at the PUJ (the point at which the ureter crosses the iliac vessels) and the vesicoureteric junction (VUJ). Symptoms include abdominal or flank pain (typically severe), haematuria and renal colic. Renal colic is due to an increase in ureteral peristalsis in response to the passage of small stones along the inner lumen of the ureter. The pain may be associated with nausea and vomiting. The type of pain is determined by the location of the stone. If the stone is non-obstructing, pain may be absent. If the obstruction is in a calyx or at the PUJ, the patient may experience dull costovertebral flank pain or renal colic. Pain resulting from the passage of a calculus down the ureter is intense and colicky. The patient may be in mild shock with cool, moist skin. As a stone nears the VUJ, pain will be felt in the lateral flank. Men may experience testicular pain, whereas women may complain of labial pain; and both men and women may experience pain within the groin. The patient may have concomitant manifestations of urinary infection with fever and chills.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Diagnostic studies useful in the evaluation and management of renal lithiasis include urinalysis, urine culture, CT scan, IVP, retrograde pyelogram, ultrasound and cystoscopy.29 A plain film of the abdomen and renal ultrasound will identify larger, radio-opaque stones. A CT scan may be used to differentiate a non-opaque stone from a tumour. An IVP or retrograde pyelogram may be used to localise the degree and site of obstruction or to confirm the presence of a radiolucent stone, such as a uric acid calculus (cystine calculus) or a staghorn calculus (see Fig 45-6). IVP should not be performed in patients with kidney failure. Ultrasonography can be used to identify a radio-opaque or radiolucent calculus in the renal pelvis, calyx or proximal ureter.

Retrieval and analysis of the stones are important in the diagnosis of the underlying problem contributing to stone formation. The patient’s serum calcium, phosphate, sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, uric acid, urea and creatinine levels are also measured. A careful history, including previous stone formation, prescribed and over-the-counter medications, dietary supplements and family history of urinary calculi, is useful. Measurement of urine pH is useful in the diagnosis of struvite stones and renal tubular acidosis (tendency to alkaline or high pH) and uric acid stones (tendency to acidic or low pH). Patients who are recurrent stone formers should undergo a 24-hour urinary measurement of calcium, phosphate, magnesium, sodium, oxalate, citrate, sulfate, potassium, uric acid and total volume.30

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE