Chapter 53 NURSING MANAGEMENT: female reproductive problems

1. Summarise the aetiologies of infertility and the strategies for diagnosis and treatment of the infertile woman.

2. Describe the aetiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of menstrual problems and abnormal vaginal bleeding.

3. Analyse the risk factors, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of ectopic pregnancy.

4. Describe the changes related to menopause and the nursing and collaborative management of the patient with menopausal symptoms.

5. Explore common problems that affect the vulva, vagina and cervix and the related nursing and collaborative management.

6. Apply knowledge of assessment, multidisciplinary care and nursing management to women with pelvic inflammatory disease and endometriosis.

7. Explain the clinical manifestations, diagnostic studies, multidisciplinary care and surgical therapy for cervical, endometrial, ovarian and vulvar cancers.

8. Summarise the preoperative and postoperative nursing management for the patient requiring surgery of the female reproductive system.

9. Differentiate between the common problems that occur with cystoceles, rectoceles and fistulas and the related nursing and collaborative management.

10. Summarise the clinical manifestations of sexual assault and the appropriate nursing and collaborative management of the patient who has been sexually assaulted.

Infertility

Infertility is the inability to conceive after 2 years of regular unprotected intercourse.1 During their reproductive years approximately 15% of couples in Australia and New Zealand take longer than 1 year to achieve a planned pregnancy.2 Assessment and therapy measures can be invasive, expensive and lengthy. Understandably, infertility can constitute both a physical and an emotional crisis.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Infertility may be caused by either female or male factors, or combined factors. Conditions that cause male infertility are discussed in Chapter 54. However, in up to 30% of couples evaluated, the cause of infertility may not be identified. The factors most frequently causing female infertility include ovulation (anovulation or inadequate corpus luteum), tubal obstruction or dysfunction (endometriosis or damage from pelvic infection) and uterine or cervical factors (fibroid tumours or structural anomalies). Risk factors for infertility include tobacco and illicit drug use and an abnormal body mass index (BMI) indicating obesity or low body weight. In women the risk for infertility increases with age. In particular, the probability of becoming pregnant begins decreasing at age 35 and decreases even further after age 40.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A detailed history and a general physical examination of the woman and her partner provide the basis for selecting diagnostic studies (see Box 53-1). The possibility of medical, genetic or gynaecological diseases is explored before tests are performed to determine problems affecting general health, as well as fertility. These tests include hormone levels, ovulatory studies, tubal patency studies and postcoital studies.3

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Diagnostic studies

Ovulatory studies

A basal body temperature record is kept to determine whether there is regular ovulation (see Fig 53-1). The woman is instructed to take and graph her temperature, referred to as basal body temperature, on awakening before any activity. The same site for taking the temperature (e.g. oral, rectal) should be used each time. Any cause for variation, such as sleep problems or illness, should be noted. As ovulation approaches, the production of oestrogen increases. This may cause a drop in temperature. When ovulation occurs, progesterone is produced, causing a rise in temperature. The temperature graph thus helps detect ovulation and suggests the timing of intercourse if pregnancy is desired. Rigid adherence to a schedule for intercourse may produce psychological stress sufficient to inhibit sexual relations.

Figure 53-1 Basal body temperature chart. A, Typical biphasic temperature curve indicative of ovulation and normal progesterone effect. B, Irregular monophasic curve characteristic of anovulatory cycles. C, Ovulatory curve with sustained temperature elevation following conception and the first missed period.

Ovulation prediction kits are now available for use by women at home. These kits are generally used daily to measure luteinising hormone (LH) levels in urine samples. Ovulation occurs about 28–36 hours after the first rise of LH, so intercourse can be timed accordingly. Other tests for ovulation include cervical and vaginal smears, endometrial biopsy and plasma progesterone levels.

Tubal patency studies

Tubal factors (occlusion or deformity) are assessed most commonly by means of a hysterosalpingogram. This procedure consists of the radiographic visualisation of the uterus and tubes by injecting a radio-opaque dye through the cervix. Tubal patency, shape, position and any distortions of the endometrial cavity can be determined. Laparoscopy may be used when a hysterosalpingogram is contraindicated or other pelvic pathology appears likely.

Postcoital studies

Examination of the cervical mucus can reveal whether it undergoes favourable changes at ovulation, enabling penetration, survival and normal motility of the sperm. A postcoital test can determine whether the cervical environment is favourable for the sperm. The couple is asked to have intercourse about the time ovulation is expected and 2–12 hours before the surgery visit. Douching or bathing should be avoided before the test. The cervical and vaginal secretions are aspirated and examined for the number and motility of sperm present. Other screening tests for infertility include semen analysis and pelvic ultrasound.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: INFERTILITY

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: INFERTILITY

The management of infertility problems depends on the cause. If infertility is secondary to an alteration in ovarian function, supplemental hormone therapy to restore and maintain ovulation may be attempted.4 Drug therapy used to treat infertility is presented in Table 53-1. Chronic cervicitis and inadequate oestrogenic stimulation are cervical factors causing infertility. Antibiotic therapy is indicated for cervicitis. Inadequate oestrogenic stimulation is treated by the administration of oestrogen.

When a couple has not succeeded in conceiving while under infertility management, an option is intrauterine insemination with sperm from the partner or a donor. If this technique does not succeed, assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) may be used. ARTs include in-vitro fertilisation (IVF), gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT), zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT), donor gametes and embryo cryopreservation. IVF involves the removal of mature oocytes from the woman’s ovarian follicle via laparoscopy, followed by in-vitro fertilisation of the ova with the partner’s sperm. When fertilisation and cleavage have occurred, the resulting embryos are transferred into the woman’s uterus. The procedure requires 2–3 days to complete and is used in cases of fallopian tube obstruction, diminished sperm count and unexplained infertility. Frequently, multiple attempts are needed for successful implantation. IVF is financially costly and emotionally stressful. However, it has become an accepted method of therapy for infertile couples.

With the increasing sophistication of ARTs, couples have an increased potential for pregnancy. However, the use of ARTs often poses many ethical, legal and social concerns. Furthermore, the regulation and funding for ARTs differs between states and countries and is a factor of the relative strength of the various interest groups involved.2

Healthcare practitioners can assist women experiencing infertility by providing information about the physiology of reproduction, offering infertility evaluation and addressing the psychological and social distress that can accompany infertility. Reducing patients’ psychological stress can make them more relaxed and may assist in achieving a pregnancy.

Teaching and providing emotional support are major responsibilities throughout infertility testing and treatment. Feelings of anger, frustration, grief and helplessness may heighten as additional diagnostic tests are performed. Infertility can generate great tension in a marriage as the couple exhausts financial and emotional resources. Few insurance carriers cover the high cost of infertility testing or expensive infertility treatment. Recognising and taking steps to deal with the psychological factors that surface can assist the couple to better cope with the situation. Couples should be encouraged to participate in a support group for infertile couples, as well as individual therapy.

Abortion

An abortion is the loss or termination of a pregnancy before the fetus has developed to a state of viability. Abortions are classified as spontaneous (those occurring naturally) or induced (those occurring as a result of mechanical or medical intervention). Miscarriage is the common term for the unintended loss of a pregnancy. Habitual recurrent abortion is a history of three or more aborted pregnancies or miscarriages in succession.

SPONTANEOUS ABORTION

Spontaneous abortion is the natural loss of a pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestation. Fetal chromosomal anomalies account for 50% of miscarriages before 8 weeks of gestation. Other causes of spontaneous abortion include endocrine abnormalities, maternal infection, acquired anatomical abnormalities (e.g. uterine fibroids, endometriosis), immunological factors and environmental factors. About 10–15% of all pregnancies end as a result of spontaneous abortion.

Uterine cramping coupled with vaginal bleeding often indicates a spontaneous abortion. Cramping is usually absent if the vaginal bleeding is caused by other conditions, such as polyps. Serial serum βhuman chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) hormone and vaginal ultrasound examination of the pelvis are the most reliable indicators of early pregnancy viability. The gestational sac can be visualised using ultrasound as early as 6 weeks of gestation.

Treatment for a possible spontaneous abortion is limited. Although bed rest and avoiding vaginal intercourse are often recommended, there is no evidence that these measures improve the outcome. The woman is advised to report any bleeding to her healthcare provider. Most women proceed to abortion regardless of treatment. If the products of conception do not pass completely or bleeding becomes excessive, a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure is generally performed. The D&C involves dilating the uterine cervix and scraping the endometrium of the uterus to empty the contents of the uterus.

Women who are experiencing bleeding and cramping during pregnancy may be admitted to hospital. Vital signs and estimated blood loss are monitored, and any tissue or blood clots that might contain tissue for products of conception are examined. Women are often very distressed and experience both physical and emotional pain during and following a miscarriage. Nurses should use comfort measures to provide needed physical and mental rest and arrange for someone to stay with the patient, as emotional support is important. Nurses should be aware of the grieving process that results from the loss of a pregnancy.4 Support of the patient and her family is essential.

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Situation

A recently married 39-year-old woman is informed that the results of her amniocentesis indicate that her fetus has major chromosomal abnormalities and is expected to have severe physical and mental disabilities. The patient has no children, but her husband has three children from a previous marriage. She asks you what she should do. How would you respond?

Important points for consideration

• Decisions about whether to continue a pregnancy with a child who has severe disabilities are extremely personal and emotional. The woman and her husband will need support and information to explore their options and their values.

• Pregnancy counselling is warranted about the woman’s choices, her feelings about the pregnancy, her desire to have a child with her husband, her concerns about raising a child with severe disabilities, her feelings about abortion and concerns about possible future pregnancies.

• Patient autonomy ensures that a woman may decide for herself whether or not to continue a pregnancy.

• Abortion or termination of a pregnancy is available in all states and territories in Australia and New Zealand provided a doctor considers it necessary to preserve the woman from serious danger to her life or to her physical or mental health. In Victoria and the Australia Capital Territory abortion is available on a woman’s request. Queensland has the most restrictive law, but all abortions may be the subject of criminal law. Each state and territory in Australia has legislation prohibiting unlawful abortion. Under the Crimes Act 1961 and the Contraception, Sterilisation and Abortion Act 1977 in New Zealand, abortion is permitted under certain circumstances.

• The role of the healthcare professional in these difficult situations is to provide education and support, to remain neutral and to facilitate a decision consistent with the patient’s values.

INDUCED ABORTION

Induced abortion is the intentional or elective termination of a pregnancy. Induced abortion is done for personal reasons (at the request of the woman) and for medical reasons. Several techniques are used to induce abortion, including menstrual extraction, suction curettage, dilation and evacuation (D&E), and drug therapy. Deciding which technique to use to terminate a pregnancy depends on the gestational age (length of the pregnancy) and the woman’s condition. Table 53-2 lists current methods for induced abortion.

Suction curettage may be performed up to 14 weeks of gestation and accounts for more than 90% of abortion procedures. Drug therapy is another method to induce abortion (medical abortion) early in pregnancy. The drug agents must be given within the first 49 days of pregnancy (day 1 being the first day of the last menstrual period). Mifepristone works by blocking progesterone, a hormone needed for pregnancy to continue. It is given in combination with misoprostol, an agent that produces uterine contractions, resulting in expulsion of the products of conception. In rare cases, fatal bacterial infections have been associated with mifepristone.5 Methotrexate, also given in combination with misoprostol, is another option for medically induced abortions. Methotrexate induces abortion because of its toxicity to trophoblastic tissue. Misoprostol induces uterine contractions.

Once the decision is made to have an abortion, the woman and her significant others need support and acceptance. The patient needs to be prepared for what to expect both emotionally and physically. Grief and sadness are normal emotions after an abortion. The patient needs to understand the procedure, including instructions for preprocedure and postprocedure care. The nurse’s caring attitude can be a positive factor in the patient’s experience.

After the procedure, the patient should be taught the signs and symptoms of possible complications, such as abnormal vaginal bleeding, severe abdominal cramping, fever and foul drainage. The nurse should also stress to the patient to avoid intercourse and vaginal insertions until re-examination, which needs to be in 2 weeks. Contraception can be started the day of the procedure or during the patient’s return visit in accordance with her needs and desires.

![]() DRUG ALERT—oral contraceptives (both oestrogen and progesterone)

DRUG ALERT—oral contraceptives (both oestrogen and progesterone)

• May increase the risk of cervical, liver and perhaps breast cancer.

• May elevate blood pressure and cholesterol (related to oestrogen).

• Increase the risk of cardiac disease if the patient also smokes.

• May impair the effectiveness of concurrent use of antibiotics.

• Are contraindicated in patients with migraine headaches and depression.

PROBLEMS RELATED TO MENSTRUATION

The normal menstrual cycle is discussed in Chapter 50, and the hormonal changes related to the menstrual cycle are shown in Figure 50-8. Menstruation may be irregular during the first few years after menarche and the years preceding menopause. Once established, a woman’s menstrual cycle usually has a predictable pattern. However, considerable normal variation exists in cycle length, as well as in the duration, amount and character of the menstrual flow (see Table 50-2).

Premenstrual syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a symptom complex related to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.6 The symptoms can be severe enough to impair interpersonal relationships or interfere with usual activities. Because many symptoms may be associated with PMS, it is difficult to concisely define it. However, PMS symptoms always occur cyclically during the luteal phase before the onset of menstruation and are not present at other times of the month.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The aetiology and pathophysiology of PMS are not well understood. It may have a biological trigger with compounding psychosocial factors. Neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, could also be involved. Some women may have a genetic predisposition to PMS. Other proposed causes of PMS include hormone imbalance and nutritional deficiencies. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMD-D) is the term applied to a type of PMS. Women with PMD-D have a severe mood disorder in addition to PMS.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

PMS is extremely variable in its clinical manifestations. Variation is common between women and, for an individual woman, from one cycle to another. Common physical symptoms include breast discomfort, peripheral oedema, abdominal bloating, sensation of weight gain, episodes of binge eating and headaches. Abdominal bloating and breast swelling are caused by fluid shifts because total body weight does not generally change. Symptoms of autonomic nervous system arousal (e.g. heart palpitations, dizziness) have been reported by women with PMS. Anxiety, depression, irritability and mood swings are some of the emotional symptoms that women may experience.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

PMS can be diagnosed only when other possible causes for the symptoms have been ruled out. A focused health history and physical examination should be undertaken to identify any underlying conditions such as thyroid dysfunction, uterine fibroids or depression that may account for the symptoms. No definitive diagnostic test is available for PMS. When PMS or PMD-D is a possible diagnosis, the patient is given a symptom diary to record her symptoms prospectively for two or three menstrual cycles. Diagnosis is based on an evaluation of the woman’s symptoms.

Non-drug and drug strategies can relieve some PMS symptoms (see Box 53-2). However, no single treatment is available. The goal of treatment is to reduce the severity of symptoms and enhance the woman’s sense of control and quality of life.

Several conservative approaches to managing PMS symptoms are considered helpful, including stress management, diet changes, exercise, education and counselling. Techniques for stress reduction include yoga, meditation, imagery and biofeedback. To decrease autonomic nervous system arousal, women should avoid caffeine, reduce their dietary intake of refined carbohydrates, exercise on a regular basis and practise relaxation techniques. Eating complex carbohydrates with high fibre, foods rich in vitamin B6 and sources of tryptophan (dairy and poultry) are thought to promote serotonin production, which improves the symptoms. Vitamin B6 may be found in foods such as pork, milk, egg yolks and legumes. Although no strongly supportive data exist, limiting salt intake before menstruation and increasing calcium intake have been proposed to alleviate fluid retention, weight gain, bloating, breast swelling and tenderness.

Exercise results in a release of endorphins, leading to mood elevation. Aerobic exercise can also have a relaxing effect. Because fatigue tends to exaggerate the symptoms of PMS, adequate rest in the premenstrual period is a priority.

Explanations about PMS will help the patient to understand the complexity of the disorder and ways that she can regain a better sense of control. Assuring women that their symptoms are real and they are not ‘crazy’ may be helpful. Teaching the woman’s partner about the nature of PMS assists the partner to better understand PMS and to provide support to the woman in making lifestyle changes to reduce the symptoms of PMS.

Drug therapy

Drug therapy is considered when symptoms persist or interfere with daily functioning. Presently, no single drug can treat all the symptoms associated with PMS. One therapy may be tried for a time, and if no improvement is noted, another approach can be tried. Many treatments are symptom specific. For fluid retention, diuretics such as spironolactone are used. For reducing cramping pain, backache and headaches, prostaglandin inhibitors such as ibuprofen are used. To improve negative mood, vitamin B6 supplementation (50 mg daily) may be used. Calcium and magnesium supplementation may also be effective in alleviating psychological and physiological symptoms. For anxiety, buspirone taken during the luteal phase helps some women. Women with PMD-D may benefit from taking antidepressants, including fluoxetine and tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline).

Other drug treatments are directed at PMS in general. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; e.g. sertraline) have provided significant relief to some women with severe PMS.7 Other general treatment includes oral contraceptives containing oestrogen and progesterone. Evening primrose oil may help some women.

Dysmenorrhoea

Dysmenorrhoea is abdominal cramping pain or discomfort associated with menstrual flow. The degree of pain and discomfort varies with the individual. The two types of dysmenorrhoea are primary (no pathology exists) and secondary (pelvic disease is the underlying cause). Dysmenorrhoea is one of the most common gynaecological problems, affecting approximately 50% of all women.8

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Primary dysmenorrhea is not a disease. It is caused by an excess of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) and/or an increased sensitivity to it. Stimulation of the endometrium by oestrogen, followed by progesterone, results in a dramatic increase in prostaglandin production by the endometrium. With the onset of menses, degeneration of the endometrium releases prostaglandin. Locally, prostaglandins increase myometrial contractions and constriction of small endometrial blood vessels. This causes tissue ischaemia and increased sensitisation of the pain receptors, resulting in menstrual pain. Primary dysmenorrhoea begins in the first few years after menarche, typically with the onset of regular ovulatory cycles.

Secondary dysmenorrhoea is usually acquired after adolescence, occurring most commonly at 30 to 40 years of age. Common pelvic conditions that cause secondary dysmenorrhoea include endometriosis, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease and uterine fibroids. Because secondary dysmenorrhoea is caused by many conditions, symptoms vary. However, painful menses is present in all situations.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Primary dysmenorrhoea starts 12–24 hours before the onset of menses. The pain is most severe the first day of menses and rarely lasts more than 2 days. Characteristic manifestations include lower abdominal pain that is colicky in nature, frequently radiating to the lower back and upper thighs. The abdominal pain is often accompanied by nausea, diarrhoea, loose stools, fatigue, headache and light-headedness.

Secondary dysmenorrhoea usually occurs after the woman has experienced problem-free periods for some time. The pain may be unilateral and it is generally more constant and continues longer than in primary dysmenorrhoea. Depending on the cause, symptoms such as dyspareunia (painful intercourse), painful defecation or irregular bleeding may occur at times other than menstruation.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Evaluation begins with distinguishing primary from secondary dysmenorrhoea. A complete health history should be obtained, paying special attention to the menstrual and gynaecological history. A pelvic examination should be performed by the healthcare provider. The probable diagnosis is primary dysmenorrhoea if the history reveals an onset shortly after menarche, symptoms are only associated with menses and the pelvic examination is normal. If a specific cause of dysmenorrhoea is evident, the diagnosis is secondary dysmenorrhoea.

Treatment for primary dysmenorrhoea includes heat, exercise and drug therapy. Heat is applied to the lower abdomen or back. Regular exercise is beneficial because it may reduce endometrial hyperplasia and subsequent prostaglandin production. Primary drug therapy is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as naproxen, which has anti-prostaglandin activity. NSAIDs should be started at the first sign of menses and continued every 4–8 hours to maintain a sufficient level of the drug to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis for the usual duration of discomfort. Oral contraceptives may also be used. They decrease dysmenorrhoea by reducing endometrial hyperplasia.

Acupuncture and transcutaneous nerve stimulation provide varying degrees of relief. (See Ch 7 for a discussion of acupuncture.) These methods may be used for women who obtain inadequate relief from medications or who prefer not to take medications. Patients who are unresponsive to these treatments should be evaluated for chronic pelvic pain.

Treatment of secondary dysmenorrhoea depends on the cause. Some individuals with secondary dysmenorrhoea will be helped by the approaches used for primary dysmenorrhoea. Depending on the underlying causes of dysmenorrhoea, additional drug or surgical interventions are used.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: DYSMENORRHOEA

NURSING MANAGEMENT: DYSMENORRHOEA

One of the primary nursing roles is teaching. The nurse should instruct women on why dysmenorrhoea occurs, as well as how to treat it. This will provide them with a foundation for coping with this common problem and increase feelings of control and self-reliance.

Women often ask what can be done to relieve the minor discomfort associated with menstrual cycles. The nurse should advise that during acute pain, relief may be obtained by applying heat to the abdomen or back and taking NSAIDs for analgesia.9 Non-invasive pain-relieving practices such as distraction and guided imagery can also be suggested. Other healthcare measures to reduce the discomfort of dysmenorrhoea include regular exercise and proper nutritional habits. Avoiding constipation, maintaining good body mechanics and eliminating stress and fatigue, particularly during the time preceding menstrual periods, can also decrease discomfort.

Abnormal vaginal bleeding

Abnormal vaginal or uterine bleeding is a common gynaecological concern. Abnormalities include oligomenorrhoea (long intervals between menses, generally greater than 35 days), amenorrhoea (absence of menstruation), menorrhagia (excessive or prolonged menstrual bleeding) and metrorrhagia (irregular bleeding or bleeding between menses). The cause of abnormal bleeding may vary from anovulatory menstrual cycles to more serious causes such as ectopic pregnancy or endometrial cancer. The age of the woman provides direction for identifying the cause of bleeding. For example, a postmenopausal woman with abnormal bleeding must always be evaluated for endometrial cancer but does not need to be evaluated for possible pregnancy. For a 20-year-old woman with abnormal bleeding, the possibility of pregnancy must always be considered and the possibility of endometrial cancer would be unlikely. When bleeding is due to a disruption in the menstrual cycle (e.g. anovulation) it is called dysfunctional uterine bleeding.

Abnormal bleeding may be caused by dysfunction of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis such as a pituitary adenoma. Another cause may be infection. Changes in lifestyle such as marriage, recent moves, a death in the family, financial stress and other emotional crises can also cause irregular bleeding. Because psychological factors can influence endocrine function, they should be considered when the patient is evaluated.

TYPES OF IRREGULAR BLEEDING

Oligomenorrhoea and secondary amenorrhoea

Anovulation is the most common cause for missing menses once pregnancy has been ruled out. Additional causes of amenorrhoea are listed in Box 53-3. Primary amenorrhoea refers to the failure of the menstrual cycle to begin by age 16 years or by age 14 years if secondary sex characteristics are present. Secondary amenorrhoea refers to the cessation of the menstrual cycle once established.

BOX 53-3 Causes of amenorrhoea

Hypothalamic–pituitary axis

Ovaries

• Autoimmune disease (often involving thyroid, adrenal and islet cells)

• Congenital or genetic conditions (e.g. Turner’s syndrome)*

• Infection (e.g. mumps, oophoritis)

*Usually manifests as primary amenorrhoea.

Ovulation is often erratic for several years following menarche and before menopause. Thus oligomenorrhoea due to anovulation is common for women at the beginning and end of menstruation.10 In anovulatory cycles, the corpus luteum that produces progesterone does not form. This may result in a situation referred to as unopposed oestrogen. When unopposed by progesterone, oestrogen can cause excessive build-up of the endometrium. Persistent overgrowth of the endometrium increases a woman’s risk for endometrial cancer. To reduce this risk, progesterone or oral contraceptives are prescribed to ensure that the patient’s endometrial lining will be shed at least four to six times per year.

Menorrhagia

The excessive bleeding associated with menorrhagia can be characterised as an increased duration (more than 7 days) or an increased amount (more than 80 mL), or both. Anovulatory uterine bleeding is the most common cause of menorrhagia. An unopposed oestrogen state continues to build up the endometrium until it becomes unstable, resulting in menorrhagia. For young women with excessive bleeding, clotting disorders must be considered. Uterine fibroids (also called leiomyomas) and endometrial polyps are common causes of menorrhagia for women in their thirties and forties.

Metrorrhagia

Metrorrhagia, also referred to as spotting or breakthrough bleeding, is bleeding between menstrual periods. For all reproductive-age women, pregnancy complications such as spontaneous abortion or ectopic pregnancy must be considered as a possible cause. Other causes include cervical or endometrial polyps, infection and cancer. Spotting is common during the first three cycles of oral contraceptives. If spotting continues past the woman’s third cycle using oral contraceptives, a different pill formulation can be prescribed when other causes of metrorrhagia have been ruled out. Spotting with long-acting progestogen therapy (e.g. Mirena IUD) or progestogen-only pills is also common. For postmenopausal women, endometrial cancer must be considered whenever spotting is experienced. In postmenopausal women, exogenous oestrogen administration during hormone replacement therapy is a common cause of metrorrhagia. Menometrorrhagia is excessive bleeding that occurs at irregular intervals. It may be caused by endometrial cancer or uterine fibroids.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Because abnormal vaginal bleeding has multiple causes, the diagnostic and multidisciplinary care varies. A health history and physical examination directed at the most likely causes of vaginal bleeding for the woman’s age-group is the first step. These findings will provide the basis for selecting the necessary laboratory tests and diagnostic procedures. Treatment depends on the aetiology of the problem (e.g. menorrhagia, amenorrhoea), the degree of threat to the patient’s health and whether children are desired in the future.

Combined oral contraceptives may be prescribed for a woman with amenorrhoea to ensure regular shedding of the endometrium if she also wants contraception. If she wants to become pregnant, a fertility drug may be prescribed. If she does not need birth control, progesterone may be prescribed to ensure a shedding of the endometrial lining four to six times per year. Tranexamic acid, a non-hormonal product, may be used to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. This drug stabilises a protein that helps blood to clot. Side effects may include headaches, sinus and nasal symptoms, back pain, abdominal pain, muscle and joint pain, muscle cramps, anaemia and fatigue. Use of tranexamic acid while taking hormonal contraceptives may increase the risk of blood clots, stroke or heart attack. Women using hormonal contraception should take tranexamic acid only if there is a strong medical need.

The treatment goal for women with menorrhagia is to minimise further blood loss. If menorrhagia is the result of anovulatory cycles, the endometrium must be stabilised by a combination of oral oestrogen and progesterone.

Balloon thermotherapy is a technique for menorrhagia that involves the introduction of a soft, flexible balloon into the uterus; the balloon is then inflated with sterile fluid (see Fig 53-2). The fluid in the balloon is heated and maintained for 8 minutes, thus causing ablation (removal) of the uterine lining. When the treatment is completed, the fluid is withdrawn from the balloon and the catheter is removed from the uterus. The uterine lining sloughs off in the following 7–10 days. Uterine balloon thermotherapy is contraindicated for women who desire to maintain their fertility and for women with any suspected uterine abnormalities such as fibroids, suspected endometrial cancer, prior caesarean section or myomectomy. With severe bleeding, hospitalisation is indicated. All patients with menorrhagia should be evaluated for anaemia and treated as indicated.

Figure 53-2 Balloon thermotherapy for treatment of menorrhagia. A, A balloon-tipped catheter is inserted into the uterus through the vagina and cervix. B, The balloon is inflated with a sterile fluid that expands to fit the size and shape of the uterus. The fluid is heated to 87°C and maintained for 8 minutes while the uterine lining is treated. C, Fluid is withdrawn from the balloon and the catheter is removed.

Surgical therapy

Surgery may be indicated depending on the underlying cause of the abnormal vaginal bleeding. D&C was once a common therapy for excessive bleeding or for spotting in perimenopausal women. Now D&C is used only in extreme cases of bleeding or for older women when endometrial biopsy and ultrasonography have not provided the necessary diagnostic information. Endometrial ablation for menorrhagia may be done by laser, thermal balloon, cryotherapy, microwave energy or electrosurgical technique for patients who do not want to have children.10 If menorrhagia is caused by uterine fibroids, a hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) may be performed. A myomectomy (removal of fibroids without removal of the uterus) may be performed if the patient wants to preserve her uterus. The myomectomy is done via laparotomy, laparoscopy or hysteroscopy. Hormonal regimens and embolisation of the blood vessels supplying the fibroid tumour are other treatment options.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ABNORMAL VAGINAL BLEEDING

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ABNORMAL VAGINAL BLEEDING

Infrequent or no menses may or may not be seen as a desirable state by the patient. Teaching women about the characteristics of the menstrual cycle will enable them to identify normal variations.

Table 50-2 includes characteristics of the menstrual cycle and related patient teaching. This knowledge can diminish apprehension and dispel misconceptions about the menstrual cycle. If the patient’s menstrual cycle pattern does not fall within the normal range, she should be advised to visit her healthcare provider. Myths concerning activities allowed during menstruation are common. The nurse should be prepared to clarify the facts: bathing and hair washing are safe; a daily warm bath may help relieve pelvic discomfort; women can swim, exercise, have intercourse and basically continue their usual daily activities.

Frequent changing of tampons or pads meets comfort and hygiene needs during menstruation. The selection of internal or external sanitary protection is a matter of personal preference. Tampons are convenient and make menstrual hygiene easier, whereas pads may provide better protection. Using a combination of tampons and pads and avoiding prolonged use of superabsorbent tampons may decrease the risk of toxic shock syndrome (TSS). TSS is a rare, but acute, life-threatening condition caused by a toxin from Staphylococcus aureus. TSS causes high fever, vomiting, diarrhoea, weakness, myalgia and a sunburn-like rash.11

Whenever excessive, the amount of the patient’s vaginal bleeding should be assessed as accurately as possible. The number and size of pads or tampons used and the degree of saturation should be reported and recorded. The patient’s fatigue level, along with variations in blood pressure and pulse, should be monitored because anaemia and hypovolaemia may be present. For the patient requiring a surgical procedure, the nurse should provide the appropriate preoperative and postoperative care.

Ectopic pregnancy

An ectopic pregnancy is the implantation of a fertilised ovum anywhere outside the uterine cavity. Ectopic pregnancy is a life-threatening condition. Earlier identification has contributed to a decrease in mortality rates; however, approximately 3 million women are diagnosed annually with ectopic pregnancy (up to 3% of all pregnancies).12 Approximately 98% of ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tube (see Fig 53-3). The remaining 2–3% may be ovarian, abdominal or cervical.

Figure 53-3 Sites of implantation of ectopic pregnancies. Order of frequency of occurrence is ampulla, isthmus, interstitium, fimbria, tubo-ovarian ligament, ovary, abdominal cavity and cervix (external os).

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Any blockage of the tube or reduction of tubal peristalsis that impedes or delays the zygote passing to the uterine cavity can result in tubal implantation. After implantation, the growth of the gestational sac expands the tubal wall. Eventually the tube ruptures, causing acute peritoneal symptoms. Less acute symptoms usually begin within 6–8 weeks after the last normal menstrual period and weeks before rupture would occur.

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, prior ectopic pregnancy, current progestin-releasing intrauterine device (IUD), progestin-only birth control failure and prior pelvic or tubal surgery. Additional risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include procedures used in infertility treatment, including IVF procedures, embryo transfer and ovulation induction.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The classic symptoms of ectopic pregnancy are abdominal or pelvic pain, missed menses and irregular vaginal bleeding. Other symptoms include amenorrhoea, morning sickness, breast tenderness, gastrointestinal disturbance, malaise and syncope. Pain is almost always present and is caused by distension of the fallopian tube. It may start unilaterally and then spread to become bilateral. The character of the pain varies among women and can be colicky or vague. If tubal rupture occurs, the pain is intense and may be referred to the shoulder as a result of irritation of the diaphragm by blood released into the abdominal cavity. Symptom severity does not necessarily correlate with the extent of external bleeding present. With rupture, the risk of haemorrhage and hypovolaemic shock is present. Suspected rupture is treated as an emergency.

The vaginal bleeding that may accompany ectopic pregnancy is usually described as spotting. However, it is also possible that bleeding may be heavier and can be confused with menses.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Because of the life-threatening nature of ectopic pregnancy, it should be considered whenever pregnancy is even remotely possible. Ectopic pregnancy can be a diagnostic challenge because of its similarity to other pelvic and abdominal disorders, such as salpingitis, spontaneous abortion, ruptured ovarian cyst, appendicitis and peritonitis. A serum (radioimmunoassay) pregnancy test should be performed. If the test is negative, an ectopic pregnancy is not likely. If ectopic pregnancy cannot be excluded by the pregnancy test, further evaluation is warranted. If the patient is in a stable condition, a combination of serial serum β-hCG and vaginal ultrasonography is used. The β-hCG level is expected to double about every 48 hours in a normal pregnancy. If the β-hCG level fails to double, the patient may have an ectopic pregnancy. Transvaginal ultrasound can be used to confirm the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy once the β-hCG level has reached 1500–2000 mIU/mL.13

Absence of a normal intrauterine pregnancy means that the diagnosis is probably a spontaneous abortion or an ectopic pregnancy. With a spontaneous abortion serial serum β-hCG levels will decrease over time. A complete blood count is obtained when there is any concern regarding the amount of blood loss or if surgery is contemplated. A gradually decreasing haematocrit may indicate internal bleeding.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ECTOPIC PREGNANCY

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ECTOPIC PREGNANCY

Surgery remains the primary approach for treating ectopic pregnancies and should be performed immediately. However, medical management with methotrexate is being used with increasing success with patients who are haemodynamically stable and have a mass less than 3 cm in size. A conservative surgical approach limits damage to the reproductive system as much as possible. Removal of the pregnancy from the tube is preferred to removing the tube. Laparoscopy is preferable to laparotomy, because it decreases blood loss and the length of the hospital stay (see Fig 53-4). If the tube ruptures, conservative surgical approaches may not be possible. The patient may need a blood transfusion and supplemental intravenous (IV) fluid therapy to relieve shock and restore a satisfactory blood volume for safe anaesthesia and surgery. The use of microsurgery techniques has resulted in fewer repeated ectopic pregnancies and a higher rate of future successful pregnancies.

Nursing care depends on the condition of the patient. Before the diagnosis has been confirmed, the nurse should be alert to patient signs of increasing pain and vaginal bleeding, which may indicate that rupture of the tube has occurred. Vital signs are monitored closely, along with observation for signs of shock. The nurse should give explanations and prepare the patient for diagnostic procedures when appropriate. Preparation of the patient for abdominal surgery may follow rapidly. The nurse should assess the patient’s emotional status and give reassurance and support for the surgery to the patient and her family. Postoperatively, the patient may express a fear of future ectopic pregnancies and have many questions about the impact of this experience on her future fertility.

Perimenopause and postmenopause

The perimenopause is a normal life transition that begins with the first signs of change in the menstrual cycle and ends after cessation of menses. Menopause is the physiological cessation of menses associated with declining ovarian function. It is usually considered complete after 1 year of amenorrhoea (absence of menstruation). Menopause starts gradually and is usually associated with changes in menstruation, including menstrual flows that are increased, decreased and/or irregular. Cessation of menses finally occurs. Postmenopause refers to the time in a woman’s life after menopause.

The age at which menopause occurs ranges from 44 to 55 years, with an average age of 51 years.14 Menopause may occur earlier due to illness, surgical removal of the uterus or both ovaries, side effects of radiation therapy or chemotherapy, or drugs. The age at which menopause occurs is not affected by age at menarche, physical characteristics, number of pregnancies, date of last pregnancy or oral contraceptive use. However, genetic factors, autoimmune conditions, cigarette smoking and racial/ethnic factors have been linked to an earlier age at menopause.15

Changes within the ovary start the cascade of events that finally result in menopause. The regression of the follicles within each ovary begins at puberty and accelerates after age 35. With age, fewer follicles remain that are responsive to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). FSH normally stimulates the dominant follicle to secrete oestrogen. When the follicles can no longer respond to FSH, the production of oestrogen and progesterone from the ovary declines. However, perimenopausal women can get pregnant until menopause has occurred. This is due to many women having long anovulatory cycles interspersed with shorter, ovulatory cycles.

With decreased ovarian function, decreased levels of oestrogen cause a gradual increase in FSH and LH as a result of the negative feedback process. By the time menopause occurs, there is a 10-fold to 20-fold increase in FSH. The elevated FSH level may take several years to return to the premenopausal level. The reduced oestrogen level also causes a decrease in the frequency of ovulation and results in changes in the reproductive organs and tissues (e.g. atrophy of vaginal tissue).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Clinical manifestations of perimenopause and menopause are presented in Table 53-3. Perimenopause is a time of erratic hormonal fluctuation. Irregular vaginal bleeding is common. With decreasing oestrogen, hot flushes and other symptoms begin. The signs and symptoms of diminished oestrogen are listed in Box 53-4. The loss of oestrogen plays a significant role in the cause of age-related alterations. Changes most critical to a woman’s wellbeing are the increased risks for coronary artery disease (CAD) and osteoporosis (secondary to bone density loss). Other changes include a redistribution of fat, a tendency to gain weight more easily, muscle and joint pain, loss of skin elasticity, changes in hair amount and distribution, and atrophy of external genitalia and breast tissue.

Hallmarks of the perimenopause include vasomotor instability (hot flushes) and irregular menses. A hot flush is described as a sudden sensation of intense heat along with perspiration and flushing.16 These sensations may last from several seconds to 5 minutes and occur most often at night, thereby disturbing sleep. The cause of hot flushes, or vasomotor instability, is not clearly understood. It has been theorised that temperature regulators in the brain are in proximity to the area where gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released. The lowered oestrogen levels are correlated with dilation of cutaneous blood vessels resulting in hot flushes and increased sweating. The more sudden the withdrawal of oestrogen (e.g. surgical removal of the ovaries), the more likely the symptoms will be severe if no hormone replacement is provided. These symptoms subside over time with or without hormone replacement therapy. Hot flushes can be triggered by stress and situations that affect body temperature, such as eating a hot meal, hot weather or warm clothing.

Atrophic vaginal changes secondary to decreased oestrogen include thinning of the vaginal mucosa and the disappearance of rugae. Vaginal secretions also decrease and become more alkaline. As a result of these changes, the vagina is easily traumatised and more susceptible to infection, including a higher risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission if exposed. Dyspareunia (painful intercourse) may also occur. This can lead to unnecessary and premature cessation of sexual activity. Dryness is a problem that can be corrected easily with water-soluble lubricants or, if needed, hormonal creams or systemic hormone replacement therapy.

Atrophic changes in the lower urinary tract also occur with a decrease in oestrogen. Bladder capacity decreases and the bladder and urethral tissue lose tone. These changes can cause symptoms that mimic a bladder infection (e.g. dysuria, urgency, frequency) when no infection is present.

Whether decreasing oestrogen causes the psychological changes associated with perimenopause is unclear. The attributed depression, irritability and cognitive problems could result from life stressors or sleep deprivation from hot flushes. Depressive symptoms appear to improve when hormone levels stabilise.17

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

The diagnosis of perimenopause should be made only after careful consideration of other possible causes for the woman’s symptoms. Depression, thyroid dysfunction, anaemia or anxiety could be responsible for the same symptoms. An accurate history of menstrual patterns should be reviewed as part of establishing the diagnosis.18 Because of the hormonal fluctuations that occur before menopause, routine testing of the serum FSH level is not indicated.

Drug therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was once standard therapy in many Western countries for treating menopausal symptoms. HRT includes oestrogen for women without a uterus or oestrogen and progesterone for women with a uterus. Since 2002, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) clinical trials have changed this practice. The data from this study showed that women who had taken oestrogen plus progestin had an increased risk of breast cancer, stroke, heart disease and emboli. However, the women in the study also had fewer hip fractures and a lower risk of developing colorectal cancer. In women who took only oestrogen there was an increased risk for stroke and emboli.19 However, these women had decreased risk for fractures with no increased risk for heart disease or breast or colorectal cancer. Neither oestrogen plus progestin nor oestrogen alone affected the risk of death.19

If women wish to consider taking HRT for the short-term treatment (4–5 years) of menopausal symptoms, the risks and benefits of therapy (e.g. minimises bone loss, hot flushes, vaginal atrophic changes) should be considered carefully. The decision to take HRT, and which hormones to take, should be discussed thoroughly between the woman and her healthcare provider. If a woman chooses to use HRT, the lowest effective dose should be used.20,21 The age that a woman starts HRT may determine her risk of heart disease. The risk appears to increase the further a woman moves away from menopause.

The side effects of oestrogen include nausea, fluid retention, headaches and breast enlargement. Side effects of progesterone include increased appetite, weight gain, irritability, depression, spotting and breast tenderness. A commonly used oestrogen preparation is 0.625 mg of conjugated oestrogen daily. For symptom relief, a higher dose may be needed. To receive the protective benefit of progesterone, 5–10 mg of medroxyprogesterone is indicated for 12 days of each month on a cyclic regimen or 2.5 mg if on a continuous regimen. If the oestrogen is increased for symptom relief, the progesterone should also be increased. Other forms of progesterone include micronised progesterone creams, dermal patches, gels and lotions; rings placed around the cervix; and subcutaneous pellets. Vaginal creams are especially useful for urogenital symptoms (e.g. dryness). Transdermal (skin patch) oestrogen has the advantage of bypassing the liver, but has the disadvantage of causing skin irritation.

Can hormone replacement therapy improve cognitive function?

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Critical appraisal and synthesis of evidence

• 16 double-blind RCTs (n = 10,114) of postmenopausal healthy women 29 to >75 years old.

• Women without dementia on HRT (oestrogen alone or oestrogen and progesterone) for 2 weeks (short term) up to 5 years (long term).

• Cognitive function measured through global and specific tests including verbal and visual memory, attention and reasoning.

Implications for nursing practice

• Advise patients that HRT may be given as short-term therapy for menopausal symptoms such as intolerable hot flushes or night sweats.

• Counsel patients that current evidence does not support taking HRT to maintain cognitive function, and that HRT increases the risk of stroke and breast cancer.

P, patient population of interest; I, intervention or area of interest; C, comparison of interest or comparison group; O, outcome(s) of interest; T, time.

Antidepressants known as SSRIs, including paroxetine, fluoxetine and venlafaxine, are an effective alternative to HRT in reducing hot flushes. This effect is noted even if the user is not depressed.21 The mechanism of action is unknown. Clonidine, an antihypertensive drug, and gabapentin, an antiseizure drug, have also been shown to relieve hot flushes.

Selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SORMs), such as raloxifene, are also used in treating menopausal problems. These drugs have some of the positive benefits of oestrogen, such as preventing bone loss, without the negative effects, such as endometrial hyperplasia. Raloxifene competes with oestrogen for oestrogen receptor sites. It decreases bone loss and serum cholesterol while having minimal effects on breast and uterine tissue.

Bisphosphonates including alendronate and risedronate are also used to decrease the risk for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. These drugs enhance bone mineral density by suppressing reabsorption. SORMs and bisphosphonates are discussed further in Chapter 63 with respect to their role in the management of osteoporosis.

Non-hormonal therapy

Because of the risks associated with HRT, alternative therapies are often tried by many women to relieve menopausal symptoms. Hot flush frequency and severity can be reduced by promoting measures that would lead to a decrease in heat production and an increase in heat loss. Keeping a cool environment and limiting caffeine and alcohol intake lowers heat production. Behavioural changes, such as relaxation techniques, may also help. To promote heat loss at night when hot flushes can disrupt sleep, increase air circulation in the room and avoid bedding that traps the heat (e.g. heavy quilts). Loose-fitting clothes do not retain body heat, whereas clothes with tight necks and wrists do. Cool cloths applied to flushed areas also aid in heat loss. A daily intake of vitamin E in doses up to 800 IU may also help reduce hot flushes in some women.

A focus on improving behaviours related to good nutrition with adequate amounts of exercise and sleep can help decrease anxiety and depression. Changing sleep patterns may be helped by avoiding alcohol and controlling hot flushes. Stress reduction techniques can promote a better night’s sleep by decreasing anxiety. A regular moderate program (three to four times per week) of aerobic and weight-bearing exercises can slow the process of bone loss and a tendency towards weight gain. Exercise is important for menopausal women in modifying CAD risk factors including stress, obesity, physical inactivity and hypertension.

Nutritional therapy

Good nutrition can decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis in addition to assisting with vasomotor symptoms. A daily intake of about 125 kJ/kg of body weight is recommended. A decrease in metabolic rate and careless eating habits can cause the weight gain and fatigue often attributed to menopause. An adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D helps maintain healthy bones and counteracts loss of bone density. Postmenopausal women who are not receiving supplemental oestrogen should have a daily calcium intake of at least 1500 mg. Those who are taking oestrogen replacement need at least 1000 mg per day. Calcium supplements are best absorbed when taken with meals. Either dietary calcium or calcium supplements may be used (see Tables 63-8 and 63-9).

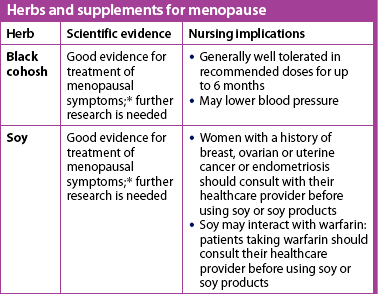

The diet should be high in complex carbohydrates and vitamin B complex, especially B6. Phyto-oestrogens from plant sources may reduce menopausal symptoms. Examples of foods containing phyto-oestrogens include soy, tofu, chickpeas and sunflower seeds. Herbal remedies, such as black cohosh, have become popular in treating menopausal symptoms (see Complementary & alternative therapies box). Consultation with an experienced herbal practitioner is recommended before initiating therapy. Many herbs can cause serious adverse effects.

Herbs and supplements for menopause

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

* Based on a systematic review of scientific literature. Available at www.naturalstandard.com, accessed 21 December 2010.

Culturally competent care: menopause

Menopause is a universal phase in a woman’s life, but the perception of this change varies by culture. Ethnic groups have their different traditions and beliefs regarding menopause. Nurses must be aware of the attitudes and beliefs regarding menopause among women from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds. In many cultures, menopause is considered a normal part of ageing and little emphasis is placed on the physical and emotional symptoms that accompany the loss of fertility. A study of Hindu women found that the women looked forward to menopause.22 In cultures where the elderly are revered, menopause is seen as a liberating transition to a state of being a ‘wise woman’.23

Western cultures generally have a negative attitude towards ageing and place high value on youth. Menopause is therefore often considered a disorder that requires treatment. Menopausal symptoms may be viewed as troublesome, with a strong need to treat hot flushes and mood swings. Numerous substances, from HRT to herbal preparations, are often used to treat menopausal symptoms.

Although menopause is experienced by all women, its meaning and symptoms vary. Menopause is a milestone in a woman’s life that is embedded in her own personality and her culture. Approaching the menopausal woman with this understanding is important in order to provide culturally competent care.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PERIMENOPAUSE AND POSTMENOPAUSE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PERIMENOPAUSE AND POSTMENOPAUSE

Nurses have a key role in helping women to understand perimenopausal changes and options to minimise troublesome symptoms. Nurses should foster a positive image of perimenopause as a time of vitality and attractiveness. They should provide teaching and reassurance to perimenopausal women who experience difficulty in managing their symptoms, and explain that symptoms are normal and often are temporary. Non-drug approaches to managing symptoms should also be discussed, along with misconceptions about menopause, to reduce unnecessary anxiety.

Dry skin can be improved by the use of moisturising soaps and body lotions. Kegel exercises may help decrease stress incontinence (see Ch 46). Sexual function can continue with little change in the vast majority of postmenopausal women. Cessation of menstruation and ability to bear children should not be equated with cessation of sexual capability; in fact, it may be liberating. Femininity and libido do not disappear with menopause. Atrophic changes in vaginal epithelium associated with decreased oestrogen may lead to dyspareunia. A water-soluble lubricant is often effective in managing this problem. An active sex life helps increase lubrication and maintains the pliability of vaginal tissues. Provide the patient with an opportunity to candidly discuss concerns related to sexual functioning.

CONDITIONS OF THE VULVA, VAGINA AND CERVIX

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Infection and inflammation of the vagina, cervix and vulva commonly occur when the natural defences of the acid vaginal secretions (maintained by sufficient oestrogen levels) and the presence of Lactobacillus are disrupted. The woman’s resistance may also be decreased as a result of ageing, poor nutrition and the use of drugs that alter the bacterial flora or mucosa. Organisms gain entrance to the areas through contaminated hands, clothing and douche tips, and during intercourse, surgery and childbirth. Table 53-4 relates the specific aetiological factors, clinical manifestations and diagnostic methods, and multidisciplinary care of common infections and inflammations.

TABLE 53-4 Infections of the lower genital tract

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; KOH, potassium hydroxide.

Most lower genital tract infections are related to sexual intercourse. Intercourse can transmit organisms, injure tissues and alter the acid–base balance of the vagina. Vulvar infections caused by viruses such as herpes and genital warts can be sexually transmitted when no lesions are apparent (see Ch 52 for discussion about sexually transmitted infections). Oral contraceptives, antibiotics and corticosteroids may produce changes in the vaginal pH and trigger an overgrowth of the organisms present. For example, Candida albicans may be present in small numbers in the vagina. An overgrowth of this organism causes vulvovaginitis.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Abnormal vaginal discharge and reddened vulvar lesions are common clinical manifestations. In addition to a thick white curd-like discharge, women with vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) often experience intense itching and dysuria, which is the result of urine coming into contact with fissures and irritated areas on the vulva. The hallmark of bacterial vaginosis is the fishy odour of the discharge. Women with cervicitis may notice spotting after intercourse.

Common vulvar lesions include herpes infection and genital warts. Initial or primary herpes infections may be extremely painful. Herpes begins as a small vesicle followed by a superficial red ulcer. Most herpes lesions are painful. Dysuria is common when urine touches the lesion. Genital warts, caused by the human papillomavirus, vary in appearance. Irregularly shaped ‘cauliflower’ lesions are common. Genital warts are painless unless traumatised. (Herpes infection and genital warts are discussed in Ch 52.)

Postmenopausal older women may develop gynaecological problems such as lichen sclerosis.24 This chronic inflammatory condition is associated with intense itching in the genital skin area (e.g. labia minora, clitoris). The lesions are white with a ‘tissue paper’ appearance initially, although scratching produces changes in the appearance. The cause is unknown. High-potency topical corticosteroid ointment such as clobetasone helps to relieve itching.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Genital problems should be evaluated by taking a history, performing a physical examination and obtaining the appropriate laboratory and diagnostic studies. Because many problems relate to sexual activity, a sexual history is essential. The nature of the problem directs specific aspects of the evaluation. Ulcerative lesions should be cultured for herpes. A blood test for syphilis may be done when ulcerative lesions are present. Genital warts are usually identified by their clinical appearance. Vulvar dystrophies may be examined via colposcopy with a biopsy taken for diagnosis.

Problems involving vaginal discharge are evaluated by microscopy and cultures. The most common vaginal conditions (i.e. bacterial vaginosis, VVC and trichomoniasis) are diagnosed by a procedure called a wet mount. The findings characteristic of each condition are shown in Table 53-4. To assess for cervicitis, endocervical cultures are obtained for Chlamydia and gonorrhoea. If purulent discharge is observed coming from the cervix, a sample of endocervical cells may be taken to conduct a Gram stain. The Gram-stained slide is examined with a microscope to identify white blood cells and gram-negative diplococci (indicative of gonorrhoea). (Sexually transmitted infections [STIs] are discussed in Ch 52.)

Drug therapy is based on the diagnosis and is shown in Table 53-4. Antibiotics taken as directed will cure bacterial infections. Antifungal preparations (in oral and cream preparations) are indicated for VVC. Women with vaginal conditions or cervical infection should abstain from intercourse for at least 1 week. Douching has been adversely linked to pelvic inflammatory disease, sexually transmitted infections and ectopic pregnancy and thus should be avoided.25 Sexual partners must be evaluated and treated if the patient is diagnosed with trichomoniasis, Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis or HIV.

Treatment of vulvar dystrophies is symptomatic because no cures are available. Treatment involves controlling the itching and hence the scratching. Interrupting the ‘itch–scratch cycle’ prevents further secondary damage to the skin.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CONDITIONS OF THE VULVA, VAGINA AND CERVIX

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CONDITIONS OF THE VULVA, VAGINA AND CERVIX

Nurses have the opportunity to teach women about common genital conditions and how to reduce their risks. Recognising symptoms that indicate a problem can help women seek care in a timely manner. Discussing problems that concern the patient’s genitals or sexual intercourse is frequently difficult. The nurse should use a non-judgemental attitude to make women feel more comfortable while empowering them to ask questions.

When a woman is diagnosed with a genital condition, the nurse should ensure that she fully understands the directions for treatment. Taking the full course of medication is especially important to decrease the chance of relapse. Because genitalia are such a private area, the use of graphs and models is especially helpful for patient teaching. When a woman will be using a vaginal medication for the first time, the nurse should show her the applicator and how to fill it, and explain where and how the applicator should be inserted (using visual aids or models). Vaginal creams should be inserted before going to bed so that the medication will remain in the vagina for a long period of time. Women using vaginal creams or suppositories may wish to use panty liners during the day when the residual medication may drain out.

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an infectious condition of the pelvic cavity that may involve the fallopian tubes (salpingitis), ovaries (oophoritis) and pelvic peritoneum (peritonitis). A tubo-ovarian abscess may also form (see Fig 53-5). Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are the most common causative organisms of PID. In Australia in 2007 notifications of Chlamydia infections were 250 per 100,000 population and Neisseria gonorrhoeae were 25 per 100,000 population.26 PID is not notifiable in New Zealand so it is difficult to know what the incidence is; however, an estimated 10–20% of women with Chlamydia may develop PID if they do not receive adequate treatment.27 PID is referred to as ‘silent’ when women do not perceive any symptoms. Other women with PID will be in acute distress. Pelvic pain may also be of a chronic nature.

Figure 53-5 Common routes of the spread of pelvic inflammatory disease. A, Direct spread of bacterial infection other than Neisseria gonorrhoeae. B, Direct spread of Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PID is often the result of untreated cervicitis. The organism infecting the cervix ascends higher into the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries and peritoneal cavity. These organisms, as well as anaerobes, mycoplasma, streptococci and enteric gram-negative rods, gain entrance during sexual intercourse or after pregnancy termination, pelvic surgery or childbirth. It is important to remember that not all cases of PID are the result of an STI.

Women at increased risk for Chlamydia infections (younger than 24 years of age, who have multiple sex partners or who have a new sex partner) should be routinely tested for Chlamydia. Chlamydia infections can be asymptomatic and unknowingly transmitted during intercourse. Silent PID is a major cause of female infertility.

Chronic pelvic pain is pain 6 months in duration or longer, and is located below the umbilicus and between the hips.28 Up to one-third of women have chronic pelvic pain after PID. Additional factors associated with chronic pelvic pain include interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, adhesions, endometriosis and dysmenorrhoea.28

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Women with PID usually see a doctor because they are experiencing lower abdominal pain. The pain typically starts gradually and then becomes constant. The intensity may vary from mild to severe. Movement such as walking can increase the pain; pain is also frequently associated with intercourse. Spotting after intercourse and purulent cervical or vaginal discharge may also be noted. Fever and chills may be present. Women with less acute symptoms often notice increased cramping pain with menses, irregular bleeding and some pain with intercourse. Women who have mild symptoms may go untreated because either they did not seek care or the healthcare provider misdiagnosed their complaints.

PID is a clinical diagnosis based on the patient’s signs and symptoms. The diagnosis is determined from data obtained during the bimanual portion of the pelvic examination. Women with PID have lower abdominal tenderness, adnexal tenderness and positive cervical motion tenderness. Additional criteria useful for diagnosis may include fever and abnormal discharge (vaginal or cervical). Cultures for gonorrhoea and Chlamydia are also obtained, and a pregnancy test is done to rule out ectopic pregnancy. Drug therapy begins when minimal diagnostic criteria are met; thus treatment is not delayed for culture results. When the patient’s pain or obesity compromises the pelvic examination and a tubo-ovarian abscess may be present, a vaginal ultrasound is indicated.

COMPLICATIONS

Immediate complications of PID include septic shock and Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome, which occurs when PID spreads to the liver and causes acute perihepatitis. The patient will have symptoms of right upper quadrant pain, but liver function tests will be normal. Tubo-ovarian abscesses may ‘leak’ or rupture, resulting in pelvic or generalised peritonitis. As the general circulation is flooded with bacterial endotoxins from the infected areas, septic shock may result. Embolisms may occur as the result of thrombophlebitis of the pelvic veins.

PID can cause adhesions and strictures to develop in the fallopian tubes. Ectopic pregnancy may result when a tube is partially obstructed because the sperm can pass through the stricture but the fertilised ovum cannot reach the uterus. After one episode of PID, the risk of having an ectopic pregnancy increases 10-fold. Further damage can obstruct the fallopian tubes and cause infertility.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

PID is usually treated on an outpatient basis. The patient is given a combination of antibiotics such as cefoxitin and doxycycline to provide broad coverage against the causative organisms. With effective antibiotic therapy, the pain should subside. The patient must have no intercourse for 3 weeks. Her partner(s) must be examined and treated. An important part of care is physical rest and oral fluids. Re-evaluation in 48–72 hours, even if symptoms are improving, is an essential part of outpatient care.

If outpatient treatment is unsuccessful or if the patient is acutely ill or in severe pain, admission to the hospital is indicated. If a tubo-ovarian abscess is present, hospitalisation is also indicated. Maximum doses of parenteral antibiotics are given in the hospital. Corticosteroids may be added to the antibiotic regimen to reduce inflammation, allowing for faster recovery and improvement in subsequent fertility. Application of heat to the lower abdomen or sitz baths may improve circulation and decrease pain. Bed rest in a semi-Fowler position promotes drainage of the pelvic cavity by gravity and may prevent the development of abscesses high in the abdomen. Analgesics to relieve pain and IV fluids to prevent dehydration are also used.

An indication for surgery is the presence of an abscess that fails to resolve with IV antibiotics. The abscess may be drained by laparoscopy or laparotomy. In extreme cases of infection or severe chronic pelvic pain, a hysterectomy may be performed. When surgery is necessary, the capacity for childbearing is preserved whenever possible.

Treatment for chronic pelvic pain should focus on the underlying disorder.28 If the source of the pain is unknown, treatment is directed at managing the symptoms.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with PID are presented in Table 53-5. Prevention, early recognition and prompt treatment of vaginal and cervical infections can help prevent PID and its serious complications. The nurse should provide accurate information about factors that place a woman at increased risk for PID and urge women to seek medical attention for any unusual vaginal discharge or possible infection of their reproductive organs. The nurse should also inform patients that not all discharge indicates infection, but that early diagnosis and treatment of an infection, if present, can prevent serious complications. Patients should be taught methods to decrease the risk of getting STIs and to recognise the signs of infection in their partner(s).

The patient may have guilt feelings about having PID, especially if it is associated with an STI. She may also be concerned about the complications associated with PID, such as adhesions and strictures of the fallopian tubes, infertility and the increased incidence of ectopic pregnancy. Discussing such feelings and concerns may assist the patient to cope more effectively with them.

For patients requiring hospitalisation, nurses have an important role in implementing drug therapy, monitoring the patient’s health status and providing symptom relief and patient teaching. The nurse records vital signs and the character, amount, colour and odour of the vaginal discharge. The nurse also explains the need for limited activity, being in a semi-Fowler’s position and increased fluid intake. Assessing the degree of abdominal pain will provide information about the effectiveness of drug therapy.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the presence of normal endometrial tissue in sites outside the endometrial cavity. The most frequent sites are in or near the ovaries, the uterosacral ligaments and the uterovesical peritoneum (see Fig 53-6). However, endometrial tissues can be in many other locations such as the stomach, lungs, intestines and spleen. The tissue responds to the hormones of the ovarian cycle and undergoes a mini–menstrual cycle similar to the uterine endometrium.

The typical patient with endometriosis will be in her late twenties or early thirties, white and never had a full-term pregnancy. Although it is not a life-threatening condition, endometriosis can cause considerable pain. It also increases the risk of ovarian cancer. Endometriosis is one of the most common gynaecological problems and is estimated to affect 10% of all women and between 30% and 50% of women with infertility.29

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The aetiology is poorly understood, and many theories about the cause of endometriosis have been proposed. A widely held view is that retrograde menstrual flow passes through the fallopian tubes carrying viable endometrial tissues into the pelvis. The tissue attaches to various sites shown in Figure 53-6. Another theory suggests that undifferentiated embryonic peritoneal cavity cells remain dormant in the pelvic tissue until the ovaries produce sufficient hormones to stimulate their growth. Other proposed causes include a genetic predisposition and altered immune function.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

In patients with endometriosis a wide range of clinical manifestations and severity exists. The magnitude of a woman’s symptoms does not necessarily correlate with the clinical extent of her endometriosis. Dysmenorrhoea after years of relatively pain-free menses and infertility may serve as clues to the presence of endometriosis. The most common manifestations are secondary dysmenorrhoea, infertility, pelvic pain, dyspareunia and irregular bleeding. Less common manifestations include backache, painful bowel movements and dysuria. These symptoms may or may not correspond to the woman’s menstrual cycle. With menopause, oestrogen is no longer produced in the ovaries. This may lead to the disappearance of the symptoms.

When the ectopic endometrial tissues ‘menstruate’, the blood collects in cyst-like nodules that have a characteristic bluish-black colour. Nodules in the ovaries are sometimes called chocolate cysts because of the thick, chocolate-colour material they contain. When a cyst ruptures, the pain may be acute and the resulting irritation promotes the formation of adhesions, which attach and fix the affected area to another pelvic structure. Endometrial lesions may become severe enough to cause a bowel obstruction or painful micturition.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Endometriosis may be suspected from a patient’s history of the characteristic symptoms and the healthcare provider’s palpation of firm nodular lumps in the adnexa on bimanual examination. However, laparoscopy is necessary for a definitive diagnosis. The treatment of endometriosis is influenced by the patient’s age, desire for pregnancy, symptom severity, and extent and location of the disease. When symptoms are not disruptive, a ‘watch and wait’ approach is used (see Box 53-5). When endometriosis is identified as a probable cause of infertility, therapy proceeds more rapidly.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Drug therapy