Chapter 54 NURSING MANAGEMENT: male reproductive problems

1. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of benign prostatic hyperplasia.

2. Explore the nursing management of benign prostatic hyperplasia.

3. Analyse the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of prostate cancer.

4. Discuss the nursing management of prostate cancer.

5. Evaluate the clinical manifestations of testicular cancer.

6. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and collaborative and nursing management of prostatitis and problems of the penis and scrotum.

7. Discuss the nursing management and multidisciplinary care of problems related to male sexual functioning.

8. Explore the psychological and emotional implications related to male reproductive problems.

benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)

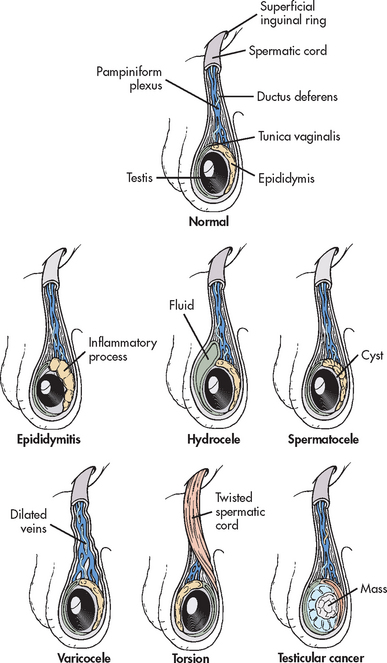

prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

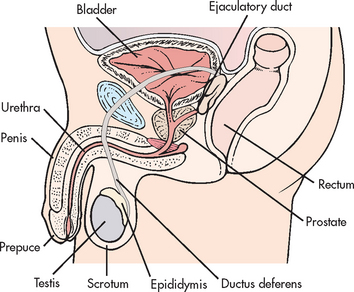

Problems of the male reproductive system can involve a variety of structures, including the prostate, penis, urethra, ejaculatory duct, scrotum, testes, epididymis, ductus deferens and rectum (see Fig 54-1). One in three men over the age of 40 years will experience erectile dysfunction, prostate disease or lower urinary tract symptoms in their lifetime.1

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is an enlargement of the prostate gland resulting from an increase in the number of epithelial cells and stromal tissue. It is the most common problem affecting the adult male reproductive system. BPH occurs in about 50% of men over 50 years of age and in 90% of men over 80 years of age.2 Approximately 25% of men require some form of treatment by the time they reach age 80. Prostate hyperplasia does not predispose the individual to the development of prostate cancer.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Although the cause of BPH is not completely understood, it is thought that BPH results from endocrine changes associated with the ageing process. Possible endocrine causes include excessive accumulation of dihydrotestosterone (the principal intraprostatic androgen), stimulation of oestrogen and local growth hormone action.

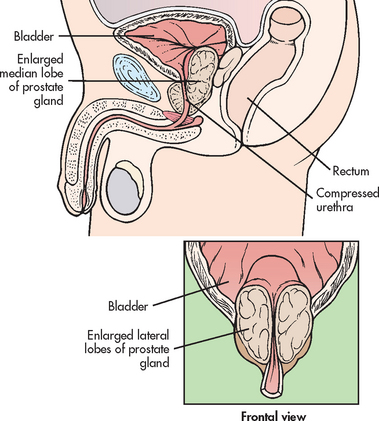

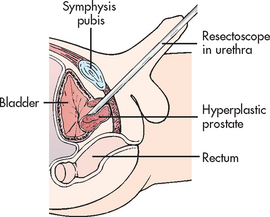

Typically, BPH develops in the inner part of the prostate. (Prostate cancer is most likely to develop in the outer part.) This enlargement gradually compresses the urethra, eventually leading to partial or complete obstruction (see Fig 54-2). It is the compression of the urethra that ultimately leads to the development of clinical symptoms. There is no direct relationship between the size of the prostate and the degree of obstruction. It is the location of the enlargement that is most significant in the development of obstructive symptoms. For example, it is possible for mild hyperplasia to cause severe obstruction; likewise, it is possible for extreme hyperplasia to cause few obstructive symptoms.

Risk factors for BPH other than ageing have not been clearly identified, although family history (particularly involving first-degree relatives), environment and diet have all been implicated.2 Men from all ethnic groups appear to be at equal risk. Some evidence has reported a higher incidence of BPH, particularly fast-growing BPH, in men with obesity, heart and circulatory diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus.2 Diabetes worsens urinary tract symptoms in men with BPH (see Ch 48). A higher risk of BPH has been found in association with a diet high in zinc, butter and margarine, whereas individuals who eat a lot of fruit are thought to have a lower risk of BPH.2,3

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The symptoms of BPH experienced by the patient result from urinary obstruction. Symptoms are usually gradual in onset and may not be noticed until prostatic enlargement has been present for some time. Early symptoms are usually minimal because the bladder can compensate for a small amount of resistance to urine flow. The symptoms gradually worsen as the degree of urethral obstruction increases.

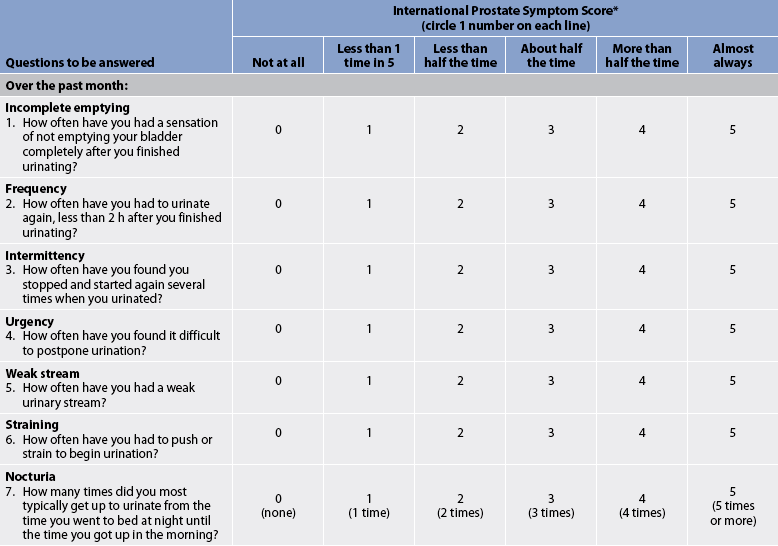

Symptoms fall into one of two groups: voiding symptoms and storage symptoms. Classic voiding symptoms include a decrease in the calibre and force of the urinary stream, difficulty in initiating voiding, intermittency (stopping and starting stream several times while voiding), dribbling at the end of urination and incomplete bladder emptying because of urinary retention. Storage symptoms, which include urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria, bladder pain, nocturia and incontinence, are associated with inflammation or infection. The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS, also known as the American Urological Association [AUA] Symptom Index for BPH; see Table 54-1) is a tool used to assess voiding symptoms associated with obstruction. Although this tool is not diagnostic, it is useful in determining the degree of symptoms, and while it is old, it has been supported by subsequent research3 and is still used by practitioners. Collectively, these symptoms are referred to as lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).

TABLE 54-1 International Prostate symptom score (IPSS)

* Also known as the American Urological Association Symptom index for BPH.

** Score is interpreted as: 0–7, mild; 8–19, moderate; 20–35, severe.

Source: From Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP et al. The American Urological Association symptom Index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol 1992; 148:1549–1557.

COMPLICATIONS

The majority of complications that develop in BPH are related to urinary obstruction leading to urinary retention. Acute urinary retention is a common complication and is an indication for surgical intervention in about 25–30% of patients. However, surgical intervention is becoming less common during the acute phase as increases in patient morbidity and mortality have been noted secondary to emergency prostate surgery.4 While there are several approaches to treating acute urinary retention, there is little consistency between countries in managing the problem.4

Another common complication is urinary tract infection (UTI) and, potentially, sepsis secondary to UTI. Incomplete bladder emptying (associated with partial obstruction) results in residual urine, providing a favourable environment for bacterial growth.

Calculi may develop in the bladder because of the alkalisation of the residual urine. Although bladder calculi are eight times more common in men with BPH, the risk of renal calculi is not significantly increased. Other less common but potential complications include renal failure caused by hydronephrosis (distension of the pelvis and calyces of the kidneys by urine that cannot flow through the ureter to the bladder), pyelonephritis and bladder damage if treatment for acute urinary retention is delayed.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The primary methods used to diagnose BPH include a history and physical examination. The prostate can be palpated by digital rectal examination (DRE). Using DRE, the healthcare provider can estimate the size, symmetry and consistency of the prostate gland. In BPH the prostate is symmetrically enlarged, firm and smooth. The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood level is generally not used to diagnose BPH; it is usually measured to rule out prostate cancer. However, PSA levels may be slightly elevated in patients with BPH.

Additional diagnostic tests may be indicated, depending on the type and severity of symptoms and clinical findings. Diagnostic tests are typically done to determine the presence of complications or for differential diagnosis. Urinalysis with culture is routinely done to determine the presence of infection. The presence of bacteria, white blood cells (WBCs) or microscopic haematuria is an indication of infection or inflammation. A serum creatinine test may be ordered to rule out renal insufficiency.

In patients with an abnormal DRE and elevated PSA level, a transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) scan is typically indicated. This examination allows accurate assessment of prostate size and is helpful in differentiating BPH from prostate cancer. Biopsies can be taken during the ultrasound procedure. Uroflowmetry, a study that measures the volume of urine expelled from the bladder per second, is helpful in determining the extent of urethral blockage and thus the type of treatment needed. Postvoid residual urine volume is often measured to determine the degree of urine flow obstruction. Cystourethroscopy, which is a procedure allowing internal visualisation of the urethra and bladder, is performed if the diagnosis is uncertain and in patients who are scheduled for prostatectomy. Diagnostic studies are outlined in Box 54-1.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

The goals of multidisciplinary care are to restore bladder drainage, relieve the patient’s symptoms and prevent or treat the complications of BPH (see Box 54-1). Treatment is generally based on the degree to which the symptoms bother the patient or the presence of complications rather than the size of the prostate. The numerous treatment options for BPH can be categorised as conservative therapy (including drug therapy) and invasive therapy.

The most conservative initial treatment for BPH is referred to as observation or ‘watch and wait’. When there are no symptoms or only mild ones (IPSS ≤7), a wait-and-see approach is taken. Because symptoms may come and go, a conservative approach has value. Dietary changes (decreasing intake of caffeine and artificial sweeteners, limiting spicy or acidic foods), avoiding medication such as decongestants and anticholinergics, and restricting evening fluid intake may result in an improvement of symptoms. A timed voiding schedule may reduce or eliminate symptoms, thus obviating the need for further intervention. If the patient begins to have signs or symptoms that indicate an increase in obstruction, further treatment is indicated.

Drug therapy

Drugs that have been used to treat BPH with variable degrees of success include 5-α-reductase inhibitors and α-adrenergic receptor blockers.

5-α-reductase inhibitors

These drugs work by reducing the size of the prostate gland. Finasteride blocks the enzyme 5-α-reductase, which is necessary for the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the principal intraprostatic androgen. This drug results in regression of hyperplastic tissue through suppression of androgens and reduces urinary outflow resistance. Finasteride is an appropriate treatment option for individuals who score between 12 and 26 on the IPSS (see Table 54-1). Although 40–50% of those treated show improvement, it takes 6–12 months to be effective and the medication must be taken on a continuous basis to maintain therapeutic results. Finasteride does lead to statistically significant improvement in symptom scores and flow rates but the magnitude of the effect is small in comparison with that of surgical treatment. Finasteride may also lower the risk of low-grade early-stage prostate cancer when used for symptom relief from BPH.5 Side effects include decreased libido, decreased volume of ejaculate and erectile dysfunction.

α-adrenergic receptor blockers

Another drug treatment option for BPH involves agents that block α1-adrenergic receptors. Although these drugs are more commonly used for the treatment of hypertension, they also promote smooth muscle relaxation in the prostate. α1-adrenergic receptors are abundant in the prostate and are increased in hyperplastic prostate tissue. Relaxation of the smooth muscle ultimately facilitates urinary flow through the urethra.

Currently, the α-adrenergic blockers are the most widely prescribed drugs for patients with BPH who are experiencing moderate symptoms without the presence of other complications. These agents demonstrate a 50–60% efficacy in improvement of symptoms, with one study demonstrating a 53% improvement in normal voiding following a successful trial without a catheter.4 Improvement of symptoms occurs within 2–3 weeks. The most important side effects are postural hypotension and dizziness. To minimise postural hypotension and the ‘first-dose’ effect, the dose should be titrated gradually.

Several α-adrenergic blockers, including prazosin, terazosin and tamsulosin, are used. Side effects, including postural hypotension, dizziness and fatigue, can be problematic, especially if the patient is also taking cardiac or other antihypertensive medication. It must be pointed out that although these drugs offer symptomatic relief of BPH, they do not treat hyperplasia.

Herbal therapy

Herbs extracted from plants have been used in the management of BPH. In particular, plant extracts, such as saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), have been used and patients have claimed that it improved urinary symptoms and urinary flow measures.6 Research results about the role of Serenoa repens are conflicting. A study conducted in the US found no difference when compared with the placebo and cast doubt on the effectiveness of the treatment,7 and a recent evidence-based review indicates that saw palmetto has no benefit over a placebo (see the Complementary & alternative therapies box).8

Invasive therapy

Invasive therapy is indicated when there is a decrease in urine flow sufficient to cause discomfort, persistent residual urine, acute urinary retention because of obstruction with no reversible precipitating cause or hydronephrosis. Intermittent catheterisation or insertion of an indwelling catheter can temporarily reduce symptoms and bypass the obstruction. However, long-term catheter use should be avoided because of the increased risk of infection.

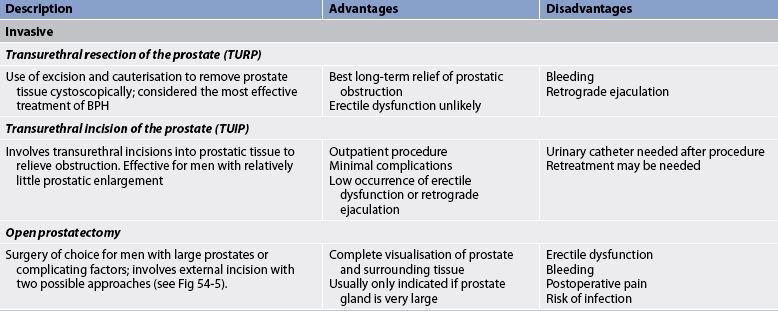

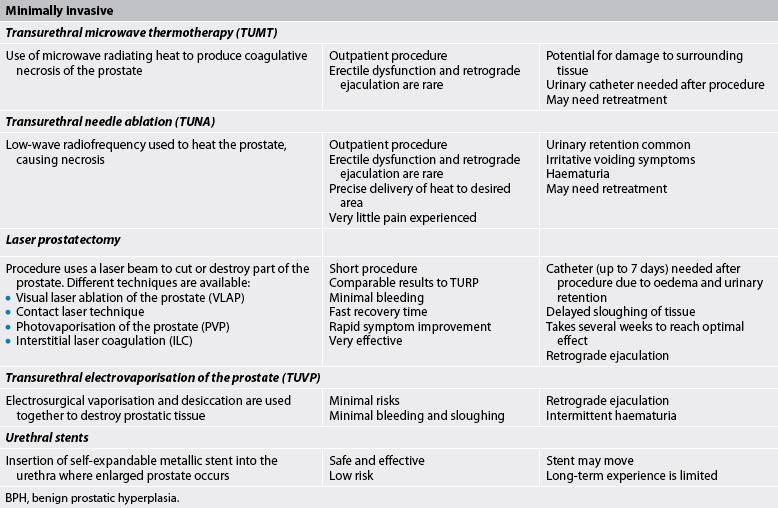

Invasive treatment of symptomatic BPH primarily involves resection or ablation of the prostate. The choice of the treatment approach depends on the size and location of the prostatic enlargement, as well as patient factors such as age and surgical risk. Various invasive treatments are summarised in Table 54-2.

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is a surgical procedure involving the removal of prostate tissue by means of a resectoscope inserted through the urethra. It is considered the gold standard of surgical procedures for this condition.2 TURP is performed under spinal or general anaesthesia. No external surgical incision is made. A resectoscope is inserted through the urethra to excise and cauterise obstructing prostatic tissue (see Fig 54-3). A large three-way indwelling catheter with a 30 mL balloon is inserted into the bladder after the procedure to provide haemostasis and to facilitate urinary drainage. The bladder is irrigated, either continuously or intermittently, usually for the first 24 hours to prevent obstruction from mucus and blood clots.

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Based on a review of scientific literature. Available at www.naturalstandard.comBent D, Kane C, Shinohara K, et al. Saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:557.

Tacklind J, MacDonald R, Rutks I, et al. Serenoa repens for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:3.

The outcome for 80–90% of patients is excellent, with marked improvements in symptoms and urinary flow rates.9 TURP is a surgical procedure with relatively low risk. Some of the postoperative complications include bleeding, clot retention and dilutional hyponatraemia associated with irrigation. Because bleeding is a common complication, patients taking aspirin or warfarin must discontinue these medications several days before surgery.

Although this procedure remains by far the most common operation performed, there has been a decrease in the number of TURP procedures done in recent years due to the development of less invasive technologies.

Minimally invasive therapy

Minimally invasive therapies are an alternative to ‘watch and wait’ and invasive treatment. They generally do not require hospitalisation or catheterisation and are associated with few adverse events. When compared to invasive techniques many of the minimally invasive therapies are less effective in improving urine flow and symptoms, which may necessitate retreatment.10 In general, there is a higher reported rate of retreatment in patients undergoing minimally invasive therapies when compared to surgical methods. Each minimally invasive treatment option provides a way of inducing urethral prostatic tissue necrosis by one of several means: microwave energy (TUMT), radiofrequency (TUNA), laser energy, water or even ultrasound energy. Various minimally invasive treatments are summarised in Table 54-2.

Transuretheral microwave thermotherapy

Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT) is an outpatient procedure that involves the delivery of microwaves directly to the prostate through a transurethral probe in order to raise the temperature of the prostate tissue to about 45°C. The heat causes death of tissue, thus relieving the obstruction. A rectal temperature probe is used during the procedure to ensure that the rectal temperature is kept below 43.5°C to prevent rectal tissue damage. Although infrequent, serious thermal injuries can occur as a consequence of TUMT due to incorrect placement of the transurethral probe or rectal temperature probe.

Postoperative urinary retention is a common complication. Thus, the patient is generally sent home with an indwelling catheter for 2–7 days to maintain urinary flow and to facilitate the passing of small clots or necrotic tissue. Antibiotics, pain medication and bladder antispasmodic medications are used to treat and prevent postprocedure problems. The procedure is not appropriate for men with rectal problems. Anticoagulant therapy should be stopped 10 days before treatment. Mild side effects include occasional problems of bladder spasm, haematuria, dysuria and retention.

Transurethral needle ablation

Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA) is another procedure that increases the temperature of prostate tissue, thus causing localised necrosis. TUNA differs from TUMT in that low-wavelength radiofrequency is used to heat the prostate, and only prostate tissue in direct contact with the needle is affected, allowing greater precision in removal of the target tissue. The extent of tissue removed by this process is determined by the amount of tissue contact (needle length), amount of energy delivered and duration of treatment. Some 70% of patients undergoing TUNA report an improvement in symptoms, making this an attractive treatment option for men with BPH.

The procedure is performed in an outpatient unit or doctor’s surgery using local anaesthesia and intravenous or oral sedation and typically lasts only 30 minutes. The patient generally experiences little pain and an early return to regular activities. Complications include urinary retention, urinary tract infection and irritative voiding symptoms (e.g. frequency, urgency, dysuria). Some patients require a urinary catheter for a short duration. Patients typically have haematuria for up to a week.

Laser prostatectomy

Laser therapy is increasingly being used to treat BPH. The laser beam is delivered transurethrally through a fibre instrument and is used for cutting, coagulation and vaporisation of prostatic tissue. There are a variety of laser procedures using different sources, wavelengths and delivery systems. A common laser procedure is laser coagulation of the prostate, often referred to as visual laser ablation of the prostate (VLAP). VLAP uses the laser beam to produce deep coagulation necrosis of the prostate. The affected prostate tissue gradually sloughs in the urinary stream. It takes several weeks before the patient reaches optimal results following this type of laser therapy. At the completion of VLAP, a urinary catheter is inserted to allow drainage.

Contact laser technique involves the direct contact of the laser with the prostate tissue. This produces an immediate vaporisation of the prostate tissue. Blood vessels near the laser tip are cauterised immediately; thus, bleeding during the procedure is rare. A three-way catheter with slow-drip irrigation is placed immediately after the procedure for a short time. Typically, the catheter is removed within 6–8 hours after the procedure. Advantages of this procedure over TURP include minimal bleeding both during and after the procedure, faster recovery time and the ability to perform the surgery on patients taking anticoagulants.

Another approach to laser prostatectomy is interstitial laser coagulation (ILC). The prostate is viewed through a cystoscope. A laser is used to treat precise areas of the enlarged prostate quickly by placement of interstitial light guides directly into the prostate tissue.

High-intensity focused ultrasound

This method utilises a transrectal probe to deliver low-energy ultrasound waves. This results in prostatic tissue necrosis due to high temperature locally. Like other minimally invasive therapies, this treatment modality is tolerated well by most patients undergoing therapy.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA

NURSING MANAGEMENT: BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA

Because the nurse is most directly involved with the care of patients with BPH who are having invasive procedures, the focus of nursing management in this section is on preoperative and postoperative care.

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

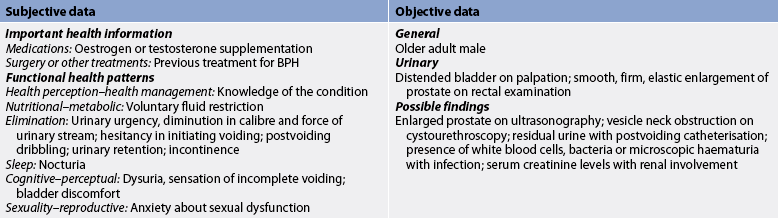

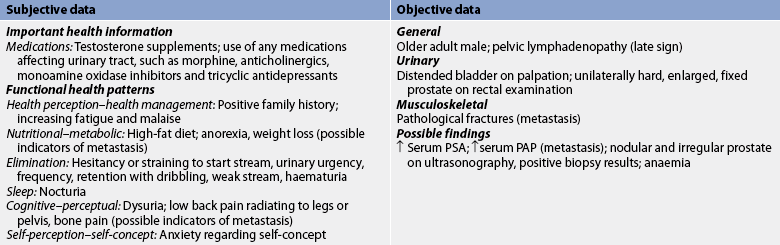

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from a patient with BPH are presented in Table 54-3.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

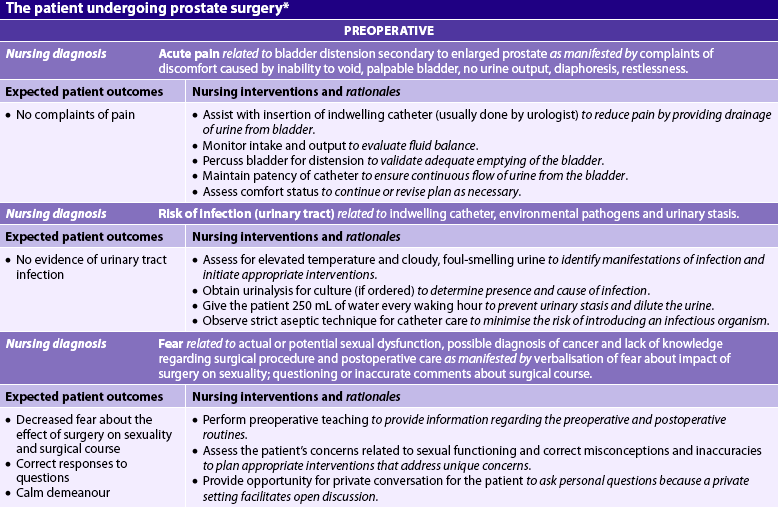

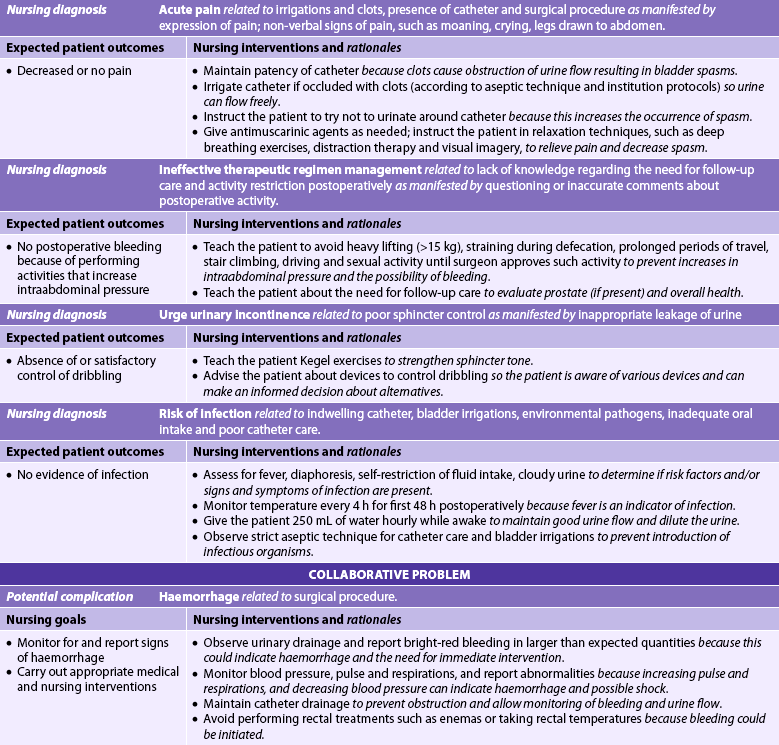

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with BPH may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 54-1.

Planning

Planning

The overall preoperative goals for the patient having invasive procedures are to have: (1) restoration of urinary drainage; (2) treatment of any urinary tract infection; and (3) understanding of the upcoming procedure, implications for sexual functioning and urinary control. The overall postoperative goals are to have: (1) no complications; (2) restoration of urinary control; (3) complete bladder emptying; and (4) satisfying sexual expression.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

The cause of BPH is largely attributed to the ageing process. The focus of health promotion is on early detection and treatment. The Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand has recently changed its recommendations about screening based on detailed evidence and found that there is no established benefit to regular or mass screening.11 Screening is found to be of most benefit for men aged between 55 and 69 years. However, if men aged around 40 or older are concerned about their prostate health, a DRE and PSA can be performed to give a baseline picture of their prostate health. Population screening of asymptomatic men is not recommended. The Cancer Society of New Zealand does not recommend routine screening but does recommend that men with a family history or with symptoms suggestive of benign or malignant prostatic disease seek assessment by a doctor. (This is in contrast to screening for prostate cancer, which is discussed later in the chapter.) When symptoms of prostatic hyperplasia become evident, further diagnostic screening may be necessary (see Box 54-1).

Some men find that the ingestion of alcohol and caffeine tends to increase prostatic symptoms because the diuretic effect of these substances increases bladder distension. Compounds found in common cough and cold remedies, such as pseudoephedrine and phenylephrine, often worsen the symptoms of BPH. These drugs are α-adrenergic agonists that cause smooth muscle contraction. If this happens, these drugs should be avoided.

The patient with obstructive symptoms should be advised to urinate every 2–3 hours and when first feeling the urge. This will minimise urinary stasis and acute urinary retention. Fluid intake should be maintained at a normal level to avoid dehydration or fluid overload. The patient may believe that if he restricts his fluid intake, symptoms will be less severe, but this only increases the chances of an infection. However, if the patient increases his intake too rapidly, bladder distension can develop because of the prostatic obstruction.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Preoperative care

Preoperative care

Urinary drainage must be restored before surgery. Prostatic obstruction may result in acute retention or inability to void. A urethral catheter such as a Coudé (curved-tip) catheter may be needed to restore drainage. In many healthcare settings, 10 mL of sterile 2% lignocaine gel is injected into the urethra before insertion of the catheter. The lignocaine gel not only acts as a lubricant but also provides local anaesthesia and helps open the urethral lumen. If a sizable obstruction of the urethra exists, a urologist may insert a filiform catheter with sufficient rigidity to pass the obstruction. Aseptic technique is important at all times to avoid introducing bacteria into the bladder.

Antibiotics are usually administered before any invasive procedure. Any infection of the urinary tract must be treated before surgery. Restoring urine drainage and encouraging a high fluid intake (2–3 L/day unless contraindicated) are also helpful in managing the infection.

The patient is often concerned about the impact of the impending surgery on his sexual functioning. Data gathered from the health history relating to sexual activities will identify possible problem areas. The nurse should provide an opportunity for the patient and his partner to express their concerns. The patient needs to know how the surgery may affect sexual functioning. All types of prostatic surgery generally result in some degree of retrograde ejaculation. The patient should be informed that the ejaculate may be decreased in amount or totally absent. This may decrease orgasmic sensations felt during ejaculation. Retrograde ejaculation is not harmful because the semen is eliminated during the next urination.

Postoperative care

Postoperative care

The main complications following surgery are haemorrhage, bladder spasms, urinary incontinence and infection. The plan of care should be adjusted to the type of surgery, the reasons for surgery and the patient’s response to surgery.

After surgery the patient will have a standard catheter or a triple lumen catheter. Bladder irrigation is typically done to remove clotted blood from the bladder and ensure drainage of urine. The bladder is irrigated either manually on an intermittent basis or more commonly as continuous bladder irrigation with sterile normal saline solution or another prescribed solution. If the bladder is manually irrigated, 50 mL of irrigating solution should be instilled and then withdrawn with a syringe to remove clots that may be in the bladder and catheter. Painful bladder spasms often occur as a result of manual irrigation. With continuous bladder irrigation, irrigating solution is continuously infused and drained from the bladder. The rate of infusion is based on the colour of drainage. Ideally the urine drainage should be light pink without clots. Inflow and outflow must be continuously monitored. If outflow is less than inflow, the catheter patency should be assessed for kinks or clots. If the outflow is blocked and patency cannot be re-established by manual irrigation, continuous bladder irrigation is stopped and the surgeon notified.

Careful aseptic technique should be used when irrigating the bladder because bacteria can easily be introduced into the urinary tract. Proper care of the catheter is important. To prevent urethral irritation and minimise the risk of bladder infection, the catheter must be secured to the leg or abdomen with tape or a catheter strap. The catheter should be connected to a closed-drainage system and should not be disconnected unless it is being removed, changed or irrigated. The secretions that accumulate around the meatus can be cleansed daily with soap and water.

Blood clots are expected after prostate surgery for the first 24–36 hours. However, large amounts of bright-red blood in the urine can indicate haemorrhage. Postoperative haemorrhage may occur from displacement of the catheter, dislodgement of a large clot or increases in abdominal pressure. Release or displacement of the catheter dislodges the balloon that provides counterpressure on the operative site. Traction on the catheter may be applied to provide counterpressure (tamponade) on the bleeding site in the prostate, thereby decreasing bleeding. Such traction can result in local necrosis if pressure is applied for too long. Pressure should be relieved on a scheduled basis by qualified personnel. Activities that increase abdominal pressure, such as sitting or walking for prolonged periods and straining to have a bowel movement (Valsalva manoeuvre), should be avoided in the postoperative recovery period.

Bladder spasms are a distressing complication for the patient after transurethral procedures. They occur as a result of irritation of the bladder mucosa from the insertion of the resectoscope, the presence of a catheter or clots leading to obstruction of the catheter. The patient should be instructed not to urinate around the catheter because this increases the likelihood of spasm. If bladder spasms develop, the catheter should be checked for clots. If present, the clots should be removed by irrigation so that urine can flow freely. Antimuscarinic agents (e.g. hyoscine, oxybutynin) along with relaxation techniques are used to relieve the pain and decrease spasm. The catheter is often removed 2–4 days after surgery. The patient should urinate within 6 hours after catheter removal. If he cannot, a catheter is reinserted for a day or two. If the problem continues, the nurse may need to instruct the patient in clean, intermittent self-catheterisation (discussed in Ch 45).

Sphincter tone may be poor immediately after catheter removal, resulting in urinary incontinence or dribbling. This is a common but distressing situation for the patient. Sphincter tone can be strengthened by advising the patient to practise Kegel exercises (pelvic floor muscle technique) 10–20 times per hour while awake. The patient should be encouraged to practise starting and stopping the stream several times during urination. This facilitates learning the pelvic floor exercises. It usually takes several weeks to achieve urinary continence. In some instances, control of urine may never be fully regained. Continence can improve for up to 12 months. If continence has not been achieved by that time, the patient may be referred to a continence clinic. A variety of methods, including biofeedback, have been used to achieve positive results. The patient can also be instructed to use a penile clamp, condom catheter or incontinence pads or briefs to avoid embarrassment from dribbling. In severe cases, an occlusive cuff that serves as an artificial sphincter can be surgically implanted to restore continence. The nurse should assist the patient in finding ways to manage the problem that will allow him to continue socialising and interacting with others.

The patient should be observed for signs of postoperative infection. If an external wound is present (from an open prostatectomy), the area should be observed for redness, heat, swelling and purulent drainage. Special care must be taken if a perineal incision is present because of the proximity of the anus. Rectal procedures, such as taking rectal temperatures and administering enemas, should be avoided.

Dietary intervention and stool softeners are important in the postoperative period to prevent the patient from straining while having bowel movements. Straining increases the intraabdominal pressure, which can lead to bleeding at the operative site. A diet high in fibre facilitates the passage of stool.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

Discharge planning and home care issues are important aspects of care after prostate surgery. Instructions include: (1) caring for an indwelling catheter (if one is left in place); (2) managing urinary incontinence; (3) maintaining oral fluids between 2 and 3 L per day; (4) observing for signs and symptoms of urinary tract and wound infection; (5) preventing constipation; (6) avoiding heavy lifting (>15 kg); and (7) refraining from driving or intercourse after surgery as directed by the surgeon.

The patient may experience a change in sexual functioning following surgery. Many men experience retrograde ejaculation because of trauma to the internal sphincter. Semen is discharged into the bladder at orgasm and may produce cloudy urine when the patient urinates after orgasm. Physiological erectile dysfunction (ED) may occur if the nerves are cut or damaged during surgery. The patient may experience anxiety over the change due to a perceived loss of his sex role, self-esteem or quality of sexual interaction with his partner. The nurse should discuss these changes with the patient and his partner and allow them to ask questions and express their concerns. Sexual counselling and treatment options may be necessary if ED becomes a chronic or permanent problem. (ED is discussed later in this chapter.) It should be pointed out that although some patients may be worried about changes in sexual function, this is not a universal concern. Many men are comfortable with such changes and view them as appropriate for their age. If this is the case, nurses should be careful not to cause concern in their enthusiastic attempts to pursue such problems.

The bladder may take up to 2 months to return to its normal capacity. The patient should be instructed to drink at least 2 L of fluid per day and urinate every 2–3 hours to flush the urinary tract. Bladder irritants such as caffeine products, citrus juices and alcohol should be avoided or limited to small amounts. Because the patient may be experiencing incontinence or dribbling, he may incorrectly believe that decreasing fluid intake will relieve this problem. Urethral strictures may result from instrumentation or catheterisation. Treatment may include teaching the patient intermittent clean catheterisation or having a urethral dilation.

The patient must be advised that he should continue to have a yearly DRE if he has had any procedure other than complete removal of the prostate. Hyperplasia or cancer can occur in the remaining prostatic tissue.

Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is a malignant tumour of the prostate gland. In Australia, diagnoses of prostate cancer are increasing, with approximately 3.1 additional cases per 100,000 population diagnosed per year (more than 19,000 men).12 Nearly 3000 men a year die from the disease.13 In New Zealand in 2007 there were 2954 prostate cancer registrations and 574 deaths.14 One in every 11 men will develop prostate cancer at some point during their lifetime. Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men, excluding non-melanoma skin cancers. It is the second leading cause of cancer death in men in Australia (exceeded only by lung cancer)13 and the third leading cause in New Zealand.14 However, by the end of 2011 it is projected that prostate cancer will be the leading cause of male cancer-related deaths.11 The majority of cases (more than 80%) occur in men over the age of 65 years. However, many cases occur in younger men who sometimes have a more aggressive type of cancer. The large increase in the incidence of newly diagnosed cases of prostate cancer since 1990 has been attributed to the widespread use of PSA as a screening procedure, allowing early detection of prostate cancer (i.e. the rise is due to earlier detection rather than an absolute increase in the rate).13 Prostate cancer incidence is forecast to continue its steady upward trend, particularly as a result of population ageing.11

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Prostate cancer is an androgen-dependent adenocarcinoma. The majority of tumours occur in the outer aspect of the prostate gland. The cancer is usually slow growing. It can spread by three routes: (1) direct extension, (2) through the lymph system or (3) through the bloodstream. Spread by direct extension involves the seminal vesicles, urethral mucosa, bladder wall and external sphincter. The cancer later spreads through the lymphatic system to the regional lymph nodes. The veins from the prostate seem to be the mode of spread to the pelvic bones, head of the femur, lower lumbar spine, liver and lungs.

Age, ethnicity and family history are three non-modifiable risk factors for prostate cancer. The incidence of prostate cancer rises markedly after age 50 years; more than 80% of men diagnosed are older than 65 years. Australian and New Zealand-born males from European backgrounds have higher death rates from prostate cancer than men born outside of either country, and the lowest rates are found in men born in Asia. A family history of prostate cancer, especially first-degree relatives (fathers, brothers), is also associated with an increased risk. Hereditary forms of prostate cancer account for approximately 9% of all cases. The hereditary prostate cancer gene 1 (HPC1) has been linked to the ribonuclease L or RnaseL gene on chromosome 1 and has signified a new direction for prostate cancer research. In addition, the macrophage scavenger receptor 1 (MSR1) on chromosome 8p has been linked to hereditary prostate cancer.15

Chemoprevention of prostate cancer is now an active area of research.16 Recent findings of a large trial of more than 18,000 men indicate that finasteride reduces the chance of getting prostate cancer by up to 25%.5 High-grade tumours were found earlier because men taking finasteride have a smaller prostate volume. Finasteride is a 5-α-reductase inhibitor used to treat BPH. It blocks the enzyme 5-α-reductase, which is necessary for the conversion of testosterone to dihydroxytestosterone. Men who are concerned about prostate cancer should discuss the potential risks and benefits of taking finasteride with their doctor.

Although occupational exposure to chemicals (e.g. cadmium) may be associated with higher prostate cancer risk, this possible cause continues to be studied. A history of BPH is not a risk factor for prostate cancer; however, dietary factors may be associated with prostate cancer.17 A diet high in red meat and high-fat dairy products along with a low intake of vegetables and fruits may increase the risk of prostate cancer. Studies are examining the role of dietary carotenoids (e.g. lycopene) and antioxidants (e.g. vitamins E and D and selenium) in reducing prostate cancer risk.18

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

Prostate cancer is usually asymptomatic in the early stages. Eventually the patient may have symptoms similar to those of BPH, including dysuria, hesitancy, dribbling, frequency, urgency, haematuria, nocturia, retention, interruption of urinary stream and inability to urinate. Pain in the lumbosacral area that radiates down to the hips or legs, when coupled with urinary symptoms, may indicate metastasis.

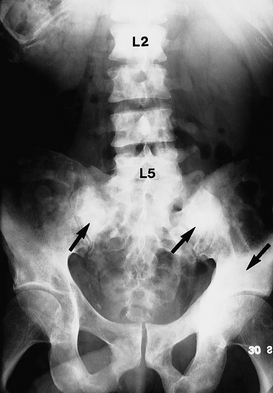

Early recognition and treatment are required to control growth, prevent metastasis and preserve quality of life.19 The tumour can spread to pelvic lymph nodes, bones, the bladder, lungs and liver. Once the tumour has spread to distant sites, the major problem becomes the management of pain. As the cancer spreads to the bones (a common site of metastasis), pain can become severe, especially in the back and the legs because of compression of the spinal cord and destruction of bone (see Fig 54-4).

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Improved diagnostic techniques have greatly enhanced the detection of prostate cancer. The two primary screening tools are DRE and a blood test for PSA, a glycoprotein produced by the prostate. On DRE the prostate may feel hard and have asymmetrical enlargement with areas of induration or nodules.

Elevated levels of PSA (normal level, 0–4.0 ng/mL) indicate prostatic pathology, although not necessarily prostate cancer. However, prostate pathology has been diagnosed in patients with PSA levels <2.5 ng/mL.20 Mild elevations in PSA may occur in BPH, acute or chronic prostatitis, urinary retention or after a long bike ride. In addition, cystoscopy, indwelling urethral catheters and prostate biopsies may produce an elevation. When prostate cancer exists, serum PSA levels are a useful marker of tumour volume (i.e. the higher the PSA level, the greater the tumour mass). Some men with prostate cancer have normal PSA levels.

PSA is used not only to detect prostate cancer but also to monitor the success of treatment. When the treatment has been successful in removing prostate cancer, PSA levels should fall to undetectable levels. Regular measurement of PSA levels following treatment is important to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment and the possible recurrence of prostate cancer.

Elevated level of prostatic isoenzyme of serum acid phosphatase (prostatic acid phosphatase [PAP]) is another indication of prostate cancer, especially if there is extracapsular spread. In advanced prostate cancer, serum alkaline phosphatase is increased as a result of bone metastasis. Investigation is now underway to locate a serum marker for prostate cancer similar to CA-125, which is a useful marker in ovarian cancer. (Ovarian cancer is discussed in Ch 53.) A recent study found that the enzyme flap endonuclease 1 (FEN-1) occurs at significant levels in patients with prostatic cancer, with the level rising as the disease progresses.21 The correlation between FEN-1 levels and disease progression was made using the Gleason grading system (see below) for prostate cancer.21

Neither the PSA level nor DRE is a definitive diagnostic test for prostate cancer. If PSA levels are elevated or if the DRE is abnormal, biopsy of the prostate tissue is indicated. Biopsy has been recommended to take place when the PSA level is 3.0 ng/mL or with a suspicious DRE.11 This is important, due to the potential diagnosis of prostate pathology in patients with a PSA >4.0 ng/mL. Biopsy of prostate tissue is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of prostate cancer. The biopsy is typically done using TRUS because it allows the doctor to visualise the prostate and pinpoint abnormalities. When a suspicious area is located, a special biopsy needle is inserted into the prostate to obtain a tissue sample. An examination of the tissue specimen is done to assess for malignant changes. Other tests used to determine the location and extent of the spread of the cancer may include bone scan, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using an endorectal probe, and TRUS (see Box 54-2).

The Prostascint scan is a single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging technique that uses a monoclonal antibody to target prostate-specific membrane antigens. This procedure is able to detect spread of prostate cancer to the pelvic lymph nodes.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

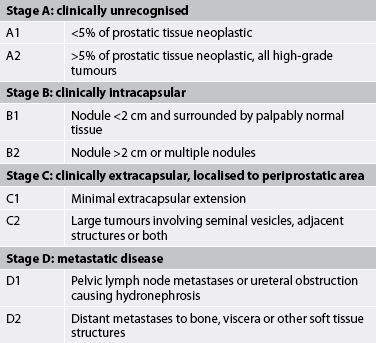

Early-stage prostate cancer is a curable disease in the majority of men. Based on findings from diagnostic studies, the prostate cancer is staged and graded. Two common classification systems used for staging prostate cancer, the Whitmore-Jewett system (see Table 54-4) and the tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) system, are both based on the size (volume) of the tumour and its spread. It is estimated that 80% of patients with prostate cancer are initially diagnosed when the cancer is in either a local or a regional stage. The 5-year survival rate with an initial diagnosis at this stage is 91–100%.11,12

TABLE 54-4 Whitmore-Jewett staging classification of prostate cancer

Source: Adapted from Schroeder F, Hermanek P, Denis L et al. TNM classification of prostate cancer. Prostate 1992; 4(suppl):129; and American Joint Committee on Cancer. Manual for staging of cancer. 4th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1992.

Grading of the tumour is done based on tumour histology using the Gleason scale. With this scale, tumours are graded from 1 to 5 based on the degree of glandular differentiation. Grade 1 represents the most well differentiated (most like the original cells) and grade 5 represents the most poorly differentiated (undifferentiated). Gleason grades are given to the two most commonly occurring patterns of cells and added together. The Gleason score is a number from 2 to 10. This scale is used to predict how quickly the cancer will progress.22

The multidisciplinary care of the patient with prostate cancer depends on the stage of the cancer and the overall health of the patient. At all stages, there is more than one possible treatment option. The decision on which treatment course to pursue is made jointly by the patient and his doctor based on a careful analysis of the facts and the patient’s preference. Box 54-2 summarises the various treatment options available.

Conservative therapy

Only some prostate cancers are highly aggressive; the majority are relatively slow growing. Therefore, a conservative approach to management of prostate cancer is observation or ‘watch and wait’ (also known as ‘deferred treatment’). The decision to adopt a strategy of watchful waiting is appropriate when there is: (1) a life expectancy of less than 10 years; (2) the presence of significant comorbidities; and (3) the presence of a low-grade, low-stage tumour. These patients are typically followed with frequent PSA measurements, along with DRE, to monitor the progress of the disease. Significant changes in either PSA level or DRE, or the development of other symptoms, warrant a re-evaluation of treatment options, whether they be definitive or palliative.

Surgical therapy

Radical prostatectomy

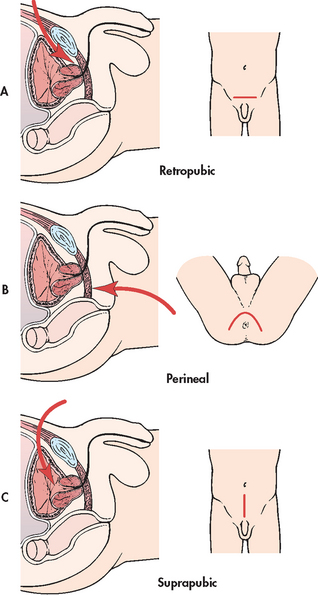

In radical prostatectomy, the entire prostate gland, seminal vesicles and part of the bladder neck (ampulla) are removed. The entire prostate is removed because the cancer tends to be in many different locations within the gland.15 In addition, a retroperitoneal lymph node dissection is usually done. A radical prostatectomy is the surgical procedure considered the most effective treatment for long-term survival.15 Thus, it is the preferred treatment for men with a greater than 10-year life expectancy who are in good health and with the cancer confined to the prostate (stages A and B). Surgery is usually not considered an option for stage D cancer (except to relieve symptoms associated with obstruction) because metastasis has already occurred. The two most common approaches for radical prostatectomy are retropubic and perineal resection (see Fig 54-5). With the retropubic approach, a low midline abdominal incision is made to access the prostate gland, and the pelvic lymph nodes can be dissected. With the perineal resection, an incision is made between the scrotum and anus. This procedure cannot remove lymph nodes.

Figure 54-5 Three approaches used to perform a prostatectomy. A, Retropubic approach involves a midline abdominal incision. B, Perineal approach involves an incision between the scrotum and anus. C, Suprapubic approach involves an abdominal incision.

A laparoscopic approach to prostatectomy is used in some settings. While it has the potential to offer technological improvement, less bleeding, less pain and faster recovery compared to traditional approaches, the long-term benefits are still being investigated. A robotic-assisted (e.g. da Vinci system) prostatectomy is a type of laparoscopy in which the surgeon sits at a computer console while controlling high-resolution cameras and microsurgical instruments. Robotics allow for increased precision, visualisation and dexterity by the surgeon when removing the prostate gland. Compared to traditional approaches, laparoscopic and robotic-assisted prostatectomy evaluations have shown similar surgical outcomes to traditional surgery with improved recovery times.19

After surgery, the patient has a large indwelling catheter with a 30 mL balloon placed in the bladder via the urethra. This catheter is typically left in place for 1–3 weeks. A drain is left in the surgical site to aid in the removal of drainage from the area. This drain is typically removed after a couple of days. Because the perineal approach has a higher risk of postoperative infection (due to the location of the incision related to the anus), careful dressing changes and perineal care after each bowel movement are important for comfort and to prevent infection. The typical length of hospital stay postoperatively is 3 days.

Two major complications following a radical prostatectomy are erectile dysfunction and incontinence. Because this procedure often destroys the nerves needed for erection, erectile dysfunction may occur. The incidence of erectile dysfunction is dependent on the patient’s age, preoperative sexual functioning, whether nerve-sparing surgery was performed and the expertise of the surgeon. Problems with urinary control occur in nearly all men for the first few months following surgery because the bladder must be reattached to the urethra after the prostate is removed. Over time, the bladder adjusts and most men regain control. It is estimated that up to 5% of men may still be incontinent up to 18 months after surgery. Other common complications associated with surgery include haemorrhage, urinary retention, infection, wound dehiscence, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli.

Nerve-sparing procedure

Many men desire to retain sexual function following radical prostatectomy. In such cases a nerve-sparing procedure that spares the nerves responsible for erection may be possible. This procedure is the preferred choice for most men undergoing prostatectomy in the early stage of the disease. Nerve-sparing prostatectomy is indicated only for patients with cancer confined within the prostate gland. Although the risk of erectile dysfunction is significantly reduced with this procedure, there is no guarantee that potency will be maintained. Because the nerves lie directly beneath the prostate gland, the risk of damage is very high. The percentage of success reported varies.

Cryosurgery

Prostatic cryosurgery is a surgical technique that destroys cancer cells by freezing the tissue. It has been used both as an initial treatment and as a second-line treatment after radiation treatment failures. A TRUS probe is used to visualise the prostate gland and liquid nitrogen is inserted into the prostate, destroying the tissue through a series of freezing/thawing cycles. Possible complications of prostatic cryosurgery include damage to the urethra and, in rare cases, a urethrorectal fistula (an opening between the urethra and the rectum) or a urethrocutaneous fistula (an opening between the urethra and the skin). Tissue sloughing, erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, prostatitis and haemorrhage have also been reported. The treatment takes about 2 hours under general or spinal anaesthesia and does not involve an abdominal incision.

Other forms of cryosurgery utilise greater accuracy in targeting pathological cells.21 For example, ultrathin 17-gauge probes are inserted under TRUS guidance via use of a brachytherapy template (see below) to ensure correct placement.21 In order to reduce complications resulting from freezing beyond the prostate border, a warming catheter is inserted prior to freezing/thawing cycles commencing.23 Specialised temperature probes located close to the prostate–rectal border monitor therapy cycles.19,23 This therapy is also used in conjunction with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with promising results.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a common treatment option for prostate cancer, especially for men over 70 years, patients who are poor surgical risks or those who wish to avoid surgery. The long-term outcome of radiation therapy is dependent on the stage of the cancer. Because many of the men choosing radiation therapy are older and perhaps not in as good health as those undergoing prostatectomy, comparisons are difficult. Radiation therapy may be offered as the only treatment, or it may be offered in combination with surgery or with hormonal therapy.

External beam radiation

External beam radiation is the most widely used method of delivering radiation treatments for those with prostate cancer. This therapy can be used to treat patients with prostate cancer confined to the prostate and/or surrounding tissue and with a life expectancy greater than 10 years (stages A, B and C). Patients are treated on an outpatient basis 5 days a week for 6–8 weeks. Each treatment lasts only a few minutes. Side effects from radiation can be acute (occurring during treatment or within the following 90 days) or delayed (occurring months or years after treatment). Common side effects involve the skin (dryness, redness, irritation, pain), gastrointestinal tract (diarrhoea, abdominal cramping, bleeding), urinary tract (dysuria, frequency, hesitancy, urgency, nocturia), sexual functioning (erectile dysfunction), fatigue and bone marrow suppression. These problems usually resolve 2–3 weeks after the completion of radiation therapy. In patients with clinically localised disease, cure rates with external beam radiation are comparable to those with radical prostatectomy.

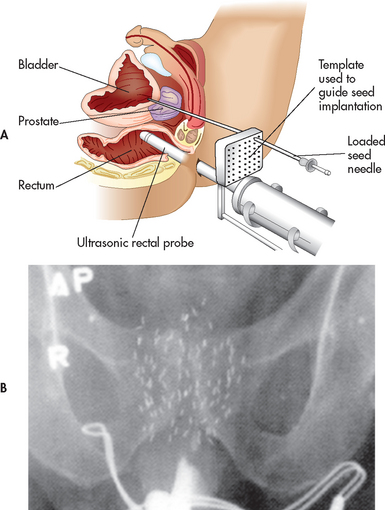

Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy involves the implantation of radioactive seeds into the prostate gland, allowing higher radiation doses directly in the tissue while sparing the surrounding tissue (rectum and bladder). The radioactive seeds are placed in the prostate gland with a needle through a grid template guided by TRUS (see Fig 54-6). The grid template and ultrasound ensure accurate placement of the seeds. Because brachytherapy is a one-time outpatient procedure, many patients find this more convenient than external beam radiation treatment. Brachytherapy is best suited for patients with a Gleason score of less than 7 and a greater than 10-year life expectancy (stage A or B prostate cancer). The most common side effect is the development of urinary irritative or obstructive problems. The IPSS (see Table 54-1) can be used to measure urinary function for patients undergoing brachytherapy and can be incorporated into postoperative nursing management. For those with more advanced tumours, brachytherapy may be offered in combination with external beam radiation treatment.

Drug therapy

The forms of drug therapy available for the treatment of prostate cancer are hormonal therapy or chemotherapy, or a combination of both.

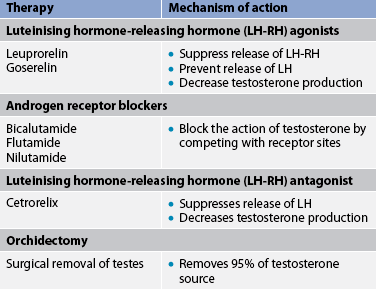

Hormone therapy

Prostate cancer growth is largely dependent on the presence of androgens. Therefore, androgen deprivation is the primary therapeutic approach for men with prostatic cancer. Hormone therapy is focused on reducing the levels of circulating androgens in order to reduce the tumour growth. Hormone or antiandrogen therapy can also be used as adjunct therapy before surgery or radiation therapy to reduce tumour size and in men with locally advanced disease (stage C). One of the biggest challenges with hormone therapy is the development of hormone-refractory disease. The duration of response to initial hormone therapy averages 1–2 years. Androgen ablation can be produced by interference with androgen production (e.g. luteinising hormone-releasing hormone [LH-RH] agonists, LH-RH antagonists, orchidectomy) or androgen receptor antagonists (see Table 54-5).

Luteinising hormone-releasing hormone agonists

LH-RH is released from the hypothalamus to stimulate the anterior pituitary to produce luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH stimulates the testicular Leydig cells to produce testosterone. The LH-RH agonists superstimulate the pituitary. This ultimately results in down-regulation of the LH-RH receptors, leading to a refractory condition in which the anterior pituitary is unresponsive to LH-RH. These drugs cause an initial transient increase in LH and testosterone. However, with continued administration, LH and testosterone levels are decreased. Current antiandrogen therapy includes leuprorelin and goserelin. This therapy essentially produces a chemical castration similar to the effects of an orchidectomy. Antiandrogen medications are given by subcutaneous or intramuscular injections on a regular basis and they must be given indefinitely. Goserelin is available as an implant that is placed subcutaneously and delivers the drug continuously for 3 months. Side effects of LH-RH agonists include hot flushes, loss of libido and erectile dysfunction.

Androgen receptor blockers

Another classification of antiandrogens is drugs that compete with circulating androgens at the receptor sites. Flutamide, nilutamide and bicalutamide are non-steroidal androgen receptor blockers. They can be used in combination with goserelin or leuprorelin. The combination has been found to be safe and well tolerated as a potency-sparing, androgen-ablative therapy. Adverse effects of androgen receptor blockers include loss of libido, erectile dysfunction and hot flushes. Breast pain and gynaecomastia may also occur in men treated with androgen receptor blockers.

Oestrogen

Oestrogen has been used as a form of androgen deprivation therapy. However, oestrogen treatment is declining in popularity because of cardiovascular complications (e.g. myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, cerebrovascular disease), lack of economic interest on the part of manufacturers and the development of more effective hormone therapies.

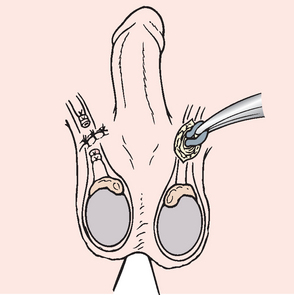

Orchidectomy

A bilateral orchidectomy is the surgical removal of the testes, which may be done alone or in combination with prostatectomy. For advanced stages of prostate cancer (stage D) an orchidectomy is one treatment option for cancer control. Since prostate cancer is a sex hormone-induced disease, testosterone, produced by the testes, stimulates growth of the prostate cancer. An orchidectomy reduces the circulating testosterone levels by 90%. Another possible benefit of this procedure is the rapid relief of bone pain associated with advanced tumours. Orchidectomy may also induce sufficient shrinkage of the prostate to relieve urinary obstruction in later stages of disease when surgery is not an option.

Side effects of orchidectomy include hot flushes, erectile dysfunction, loss of sex drive and irritability. Weight gain and loss of muscle mass, which are also common, can alter a man’s physical appearance. Osteoporosis has also been reported as a consequence of orchidectomy. These physical changes can affect self-esteem, leading to grief and depression. Although this procedure is permanent and cost-effective (compared to chemical hormone manipulation using LH-RH agonists), many men prefer drug therapy to orchidectomy.

Chemotherapy

The use of chemotherapeutic agents has primarily been limited to treatment for those with hormone-resistant prostate cancer in late-stage disease. In hormone-resistant prostate cancer, the cancer is progressing despite treatment. This occurs in patients who have taken an antiandrogen for a certain period of time. Historically, prostate cancer has been poorly responsive to chemotherapy, which has not been shown to improve survival. Thus, the goal of chemotherapy is palliation. Some of the more commonly used chemotherapy drugs include mitozantrone, cyclophosphamide, idarubicin and epirubicin. (Cancer is discussed in Ch 15.)

Bisphosphonates

Patients with advanced prostate cancer have a high risk of developing bone complications, such as pain, fractures and spinal cord compression. Bisphosphonates can be used to prevent and treat bone complications in advanced prostate cancer. Bisphosphonates include zoledronic acid, risedronate and alendronate.

CULTURALLY COMPETENT CARE: PROSTATE CANCER

Nurses must be aware of not only the epidemiological differences that occur with prostate cancer but also the differences that exist in health promotion practice. Demographic characteristics should be considered when providing information about the risk of prostate cancer and screening recommendations. For example, Māori men have a lower incidence of prostate cancer than the rest of the New Zealand male population; however, this might be due to a lower proportion of the population being screened, as the mortality rate for Māori men is higher than for non-Māori.14 Men are most likely to take part in regular screenings when they are informed of their risk of prostate cancer and screening options. Although exposure to electronic and print media is successful in informing some men about prostate cancer, significant differences of effectiveness exist based on demographic variables, such as ethnicity, age, education level and socioeconomic level. Ideally, no man should be unaware of (1) the risks associated with prostate cancer and (2) the screening methods available. Nurses who work in general practice and in the community must consider the best method to communicate this information to men of all cultures and language groups to achieve the greatest degree of understanding and participation in prostate cancer screening.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PROSTATE CANCER

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PROSTATE CANCER

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with prostate cancer are presented in Table 54-6.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with prostate cancer depend on the stage of the cancer. General nursing diagnoses, which may or may not apply to every patient with cancer of the prostate, may include, but are not limited to, the following:

• decisional conflict related to numerous alternative treatment options

• acute pain related to surgery, prostatic enlargement, bone metastasis and bladder spasms

• urinary retention related to obstruction of the urethra or bladder neck by the prostate, blood clots or loss of bladder tone

• impaired urinary elimination related to bladder neck sphincter damage

• constipation or diarrhoea related to treatment interventions

• sexual dysfunction related to the effects of treatment

• anxiety related to the uncertain outcome of the disease process, its effect on life and lifestyle and the effect of treatment on sexual functioning.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with prostate cancer will: (1) be an active participant in the treatment plan; (2) have satisfactory pain control; (3) follow the therapeutic plan; (4) accept the effect of the therapeutic plan on sexual function; and (5) find a satisfactory way to manage the impact on bladder or bowel function.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

One of the most important roles for nurses in relation to prostate cancer is to encourage patients to have an annual prostate screening (PSA test and DRE) starting at age 50 years or younger if risk factors are present.24 Because of their increased risk of prostate cancer, men with a family history of prostate cancer should have an annual PSA test and DRE beginning at age 40 years.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Preoperative and postoperative phases of radical prostatectomy are essentially the same as for open prostatectomy previously described with BPH (see Table 54-2). Nursing interventions for the patient who undergoes radiation therapy and chemotherapy are discussed in Chapter 15. An additional consideration is the psychological response of the patient to a diagnosis of cancer. The nurse should provide sensitive, caring support for the patient and his family to help them to cope with the diagnosis of cancer. Prostate support groups are available for men and their families to encourage them to be active, informed participants in their own care.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

If the patient is discharged with an indwelling catheter in place, the nurse must teach appropriate catheter care. The patient should be instructed to clean the urethral meatus with soap and water once a day; maintain a high fluid intake; keep the collecting bag lower than the bladder at all times; keep the catheter securely anchored to the inner thigh or abdomen; and report any signs of bladder infection, such as bladder spasms, fever or haematuria. If urinary incontinence is a problem, patients should be encouraged to practise pelvic floor muscle exercises (Kegel exercises) at every urination and throughout the day. Continuous practice during the 4–6 week healing process improves the success rate. Products used for incontinence that are specifically designed for men are available through home care product catalogues and many retail stores.

Although prostate cancer has a high cure rate if detected and treated early, prognosis for stage D prostate cancer is very unfavourable. Hospice care is often appropriate and beneficial to the patient and family. (Hospice care is discussed in Ch 9.) Common problems experienced by the patient with advanced prostate cancer include fatigue, bladder outlet obstruction and ureteral obstruction (caused by compression of the urethra and/or ureters from the tumour mass or lymph node metastasis), severe bone pain and fractures (caused by bone metastasis), spinal cord compression (from spinal metastasis) and leg oedema (caused by lymphoedema, deep vein thrombosis and other medical conditions). Nursing interventions must focus on all of these problems. However, management of pain is one of the most important aspects of nursing care for these patients. Pain control is managed through ongoing pain assessment, administration of prescribed medications (both opioid and non-opioid agents) and the use of non-pharmacological methods of pain relief. (Pain management is discussed further in Ch 8.)

Prostatitis

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Prostatitis is a broad term that describes a group of inflammatory conditions affecting the prostate gland. It is the most common urological problem in men younger than 50 years of age. It is estimated that 1 in 6 men may experience prostatitis at some time during their lives.25 Historically, this condition has lacked a strong agreement regarding the cause, diagnosis and optimal treatment. To bring greater consistency in approaching this common condition, the National Institutes of Health in the United States established consensus classifications of prostatitis syndromes and these are used in New Zealand and Australia to classify prostatitis syndromes. The consensus classifications include four categories: (1) acute bacterial prostatitis; (2) chronic bacterial prostatitis; (3) chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome; and (4) asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis.

Both acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis generally result from organisms reaching the prostate gland by one of the following routes: ascending from the urethra, descending from the bladder and invasion via the bloodstream or the lymphatic channels. Common causative organisms are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Proteus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and group D streptococci; however, the role of Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasmas and Ureaplasmas are less common but accepted as potential pathogens.25 Chronic bacterial prostatitis differs from acute prostatitis in that it involves recurrent episodes of infection.

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome describes the syndrome with prostate and urinary pain in the absence of an obvious infectious process.26 The aetiology of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is unclear.26 It may occur after a viral illness, or it may be associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), particularly in younger adults. The aetiology is not known, and a culture reveals no causative organisms. However, leucocytes may be found in prostatic secretions.

Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis is usually diagnosed in individuals who have no symptoms but are found to have an inflammatory process in the prostate. These patients are usually diagnosed during the evaluation of other genitourinary tract problems. Leucocytes are present in the seminal fluid from the prostate but the cause of this finding is unclear.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

Common clinical manifestations of acute bacterial prostatitis include fever, chills, back pain and perineal pain, along with acute urinary symptoms such as dysuria, urinary frequency, urgency and cloudy urine. The patient may also have acute urinary retention caused by prostatic swelling. With DRE, the prostate is extremely swollen, very tender and firm. The complications of prostatitis are epididymitis and cystitis. Sexual functioning may be affected as manifested by post-ejaculation pain, libido problems and erectile dysfunction. Prostatic abscess is also a potential, but somewhat uncommon, complication.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis and chronic prostatitis/pelvic pain syndrome manifest with similar symptoms that are generally milder than those associated with acute bacterial prostatitis. These include irritative voiding symptoms (frequency, urgency, dysuria), backache, perineal/pelvic pain and ejaculatory pain. Obstructive symptoms are uncommon unless the patient has coexisting BPH. With DRE, the prostate feels enlarged and firm (often described as boggy) and is slightly tender with palpation. Chronic prostatitis can predispose the patient to recurrent urinary tract infections.

The clinical features of prostatitis can mimic urinary tract infection. However, acute cystitis is not common in men.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Because patients with prostatitis have urinary symptoms, urinalysis and urine culture are indicated; often WBCs and bacteria are present. If the patient has a fever, WBC count and blood cultures are also indicated. The PSA test may be done to rule out prostate cancer. However, PSA levels are often elevated with prostatic inflammation. Thus, it is not considered diagnostic in itself.

Microscopic evaluation and culture of expressed prostate secretion (EPS) is considered useful in the diagnosis of prostatitis. EPS is obtained using a pre-massage and post-massage test. The patient is asked to void into a specimen cup just before and just after a vigorous prostate massage. Prostatic massage (for EPS) should be avoided if acute bacterial prostatitis is suspected because compression is extremely painful and can increase the risk of bacterial spread. TRUS has not been particularly useful in the diagnosis of prostatitis. However, transabdominal ultrasound or MRI may be done to rule out an abscess on the prostate.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: PROSTATITIS

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: PROSTATITIS

Antibiotics commonly used for acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis include cotrimoxazole, trimethoprim and ciprofloxacin. Doxycycline or tetracycline may be prescribed for those patients with multiple sex partners. Antibiotics are usually given orally for up to 4 weeks for acute bacterial prostatitis. However, if the patient has a high fever or other signs of impending sepsis, hospitalisation and intravenous antibiotics are prescribed. Patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis are given oral antibiotic therapy for 4–16 weeks. A short course of oral antibiotics is usually prescribed for those with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. However, antibiotic therapy is often ineffective for these patients.

Although patients with acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis tend to experience a great amount of discomfort, the pain resolves as the infection is treated. Pain management for patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is more difficult because the pain persists for weeks to months. Anti-inflammatory agents are the most common agents used for pain control in prostatitis but these provide only moderate pain relief. Opioid analgesics can be used but because this pain is chronic in nature, the use of opioids should be approached cautiously.

Acute urinary retention can develop in acute prostatitis requiring bladder drainage with suprapubic catheterisation. Passage of a catheter through an inflamed urethra is contraindicated in acute prostatitis. Repetitive prostatic massage is thought to be therapeutic for most types of prostatitis but it is not an appropriate measure for acute bacterial prostatitis. This measure relieves congestion within the prostate by squeezing out excess prostatic secretions, thus providing pain relief. Prostatic massage is performed by using the index finger of a gloved hand and pressing down on the prostate, covering the entire surface of the gland in longitudinal strokes. Measures to stimulate ejaculation (masturbation and intercourse) help drain the prostate as well and are encouraged.

Because the prostate can serve as a source of bacteria, fluid intake should be kept at a high level for all patients with prostatitis. Nursing interventions are aimed at encouraging the patient to drink plenty of fluids. This is especially important for those with acute bacterial prostatitis due to the increased fluid needs associated with fever and infection. Management of fever is also an important nursing intervention.

PROBLEMS OF THE PENIS

Health problems of the penis are rare if STIs are excluded (see Ch 52). Problems of the penis may be classified as congenital, problems of the prepuce, problems with the erectile mechanism and cancer.

Congenital problems

Hypospadias is a urological abnormality in which the urethral meatus is located on the ventral surface of the penis anywhere from the corona to the perineum. Hormonal influences in utero, environmental factors and genetic factors are possible causes. Surgical repair of hypospadias may be necessary if it is associated with chordee (a painful downward curvature of the penis during erection) or if it prevents intercourse or normal urination. Surgery may also be done for cosmetic reasons or emotional wellbeing.

Epispadias, an opening of the urethra on the dorsal surface of the penis, is a complex birth defect that is usually associated with other genitourinary tract defects. Corrective surgery to place the urethra in a normal position in the penis is usually done in early childhood.

Problems of the prepuce

Circumcision, the surgical removal of the foreskin of the penis, is a procedure done to male infants for religious or cultural reasons. It is believed to prevent problems such as phimosis (tightness of the foreskin resulting in the inability to retract it), paraphimosis (tightness of the foreskin resulting in the inability to pull it forwards from a retracted position) and cancer of the penis. In Australia and New Zealand, the circumcision rate of male infants has fallen in recent years and it is estimated that currently only 10–20% of males are circumcised.27 The Royal Australasian College of Physicians reaffirmed in 2006 that there is no medical indication for routine male circumcision and the best-recognised indicator for circumcision is phimosis.27

Phimosis is a constriction of the uncircumcised foreskin around the head of the penis, making retraction difficult. It is caused by oedema or inflammation of the foreskin, and is usually associated with poor hygiene techniques that allow bacterial and yeast organisms to become trapped under the foreskin (see Fig 54-7). Paraphimosis is oedema of the retracted uncircumcised foreskin, preventing normal return over the glans. This can occur when the foreskin is pulled back during bathing, use of urinary catheters or intercourse and is not placed back in the forward position. Antibiotics, warm soaks and sometimes circumcision or dorsal slit of the prepuce may be required. Careful cleaning followed by replacement of the foreskin generally prevents these problems.

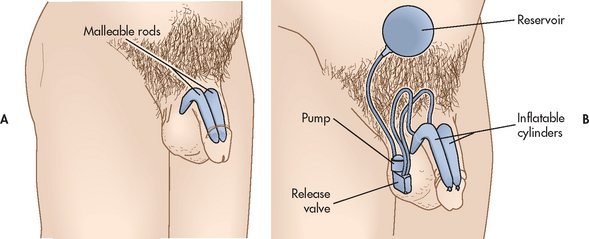

Problems of the erectile mechanism

Priapism is a painful erection lasting longer than 6 hours. Causes of priapism include thrombosis of the corpus cavernosal veins, leukaemia, sickle cell anaemia, diabetes mellitus, degenerative lesions of the spine, neoplasms of the brain or spinal cord, prolonged foreplay, injection of vasoactive medications into the corpus cavernosa and cocaine use. Treatment may include sedatives, injection of smooth muscle relaxants directly into the penis, aspiration and irrigation of the corpora cavernosa with a large-bore needle or the surgical creation of a shunt to drain the corpora. Prolonged priapism constitutes a medical emergency. Complications may include penile tissue necrosis caused by a lack of blood flow or hydronephrosis from bladder distension. After an episode of priapism, the patient may be unable to achieve a normal erection.

Peyronie’s disease, sometimes referred to as curved or crooked penis, is caused by plaque formation in one of the corpora cavernosa of the penis. The palpable, non-tender, hard plaque formation is usually found on the posterior surface. It may result from trauma to the penile shaft or may occur spontaneously. The plaque prevents adequate blood flow into the spongy tissue, which results in a curvature during erection. The condition is not dangerous but can result in painful erections, erectile dysfunction or embarrassment. If conservative measures do not correct the problem, surgery may be necessary.

Cancer of the penis

Cancer of the penis is rare in developed countries and is associated with the STI human papillomavirus (HPV) and men who were not circumcised as infants. The latest mortality figures in Australia (2005) show that 13 men died in one year from penile cancer as a primary tumour,9 and it was projected that by 2010, Australia would have had 86 new registrations, showing a steady rise over the past decade. In New Zealand, there were 12 registrations and 4 deaths from cancer of the penis in 2002;28 however, none have been reported subsequently (2011).12 The tumour may appear as a superficial ulceration or a pimple-like nodule. The non-tender warty lesion may be mistaken for a venereal wart. The majority of malignancies (95%) are well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. Treatment in the early stages is laser removal of the growth. A radical resection of the penis may be done if the cancer has spread. Surgery, radiation or chemotherapy may be tried depending on the extent of the disease, lymph node involvement or metastasis.

Inflammatory and infectious problems

SKIN PROBLEMS

The skin of the scrotum is susceptible to a number of common skin diseases. The most common conditions of the scrotal skin are fungal infections, dermatitis (neurodermatitis, contact dermatitis, seborrhoeic dermatitis) and parasitic infections (scabies, lice). These conditions involve discomfort for the patient but are associated with few, if any, severe complications (see Ch 22).

EPIDIDYMITIS