Chapter 42 NURSING MANAGEMENT: lower gastrointestinal problems

1. Explain the common aetiologies, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of diarrhoea, faecal incontinence and constipation.

2. Describe the common causes of acute abdominal pain and nursing management of the patient following an exploratory laparotomy.

3. Describe the multidisciplinary care and nursing management of acute appendicitis, peritonitis and gastroenteritis.

4. Compare and contrast the inflammatory bowel diseases of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, including pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, complications, multidisciplinary care and nursing management.

5. Differentiate between mechanical, neurogenic and vascular bowel obstructions, including causes, multidisciplinary care and nursing management.

6. Describe the clinical manifestations and collaborative management of colorectal cancer.

7. Explain the anatomical and physiological changes and nursing management of the patient with an ileostomy and colostomy.

8. Differentiate between diverticulosis and diverticulitis, including clinical manifestations, multidisciplinary care and nursing management.

9. Compare and contrast the types of hernias, including aetiology and surgical and nursing management.

10. Describe the types of malabsorption syndrome and multidisciplinary care of coeliac disease, lactase deficiency and short-bowel syndrome.

11. Examine the types, clinical manifestations, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of anorectal conditions.

gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs)

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

This chapter examines common problems with the lower intestine. Problems with the lower intestine are likely to affect most people in the community at some stage during their lifetime. While many people will not be hospitalised with their problems, nurses need to understand the causes, signs and symptoms and treatments to be able to effectively advise patients when asked for their opinion about what treatment options are best.

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea, the frequent passage of loose, liquid stools, is not a disease but a symptom. The term diarrhoea may mean different things to different people. It is commonly used to denote an increase in stool frequency or volume and an increase in the looseness of stool.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The causes of diarrhoea can be divided into the general classifications of decreased fluid absorption, increased fluid secretion and motility disturbances, or a combination of these (see Box 42-1). For example, large amounts of undigested carbohydrate in the bowel produce osmotic diarrhoea, which promotes rapid transit through the bowel and prevents absorption of fluid and electrolytes. Lactose intolerance and certain laxatives (e.g. lactulose and sodium phosphate) produce osmotic diarrhoea. Infectious agents (e.g. Escherichia coli, Salmonella), bile salts and undigested fats lead to excessive fluid secretion in the gut. The diarrhoea from coeliac disease and short bowel syndrome results from malabsorption in the small intestine. A combination of mechanisms leads to the diarrhoea of Crohn’s disease: decreased absorption because of inflammation and destruction of surface epithelium, increased secretion due to excessive bile salts, and osmotic diarrhoea from lactose intolerance.

Decreased fluid absorption

Oral intake of poorly absorbable solutes (e.g. laxatives)

Maldigestion and malabsorption (e.g. maldigestion of fat with pancreatitis, poorly absorbed bile salts in terminal ileum disease)

Mucosal damage (e.g. coeliac disease, Crohn’s disease, radiation injury, ulcerative colitis, ischaemic bowel disease)

Intestinal enzyme deficiencies (e.g. lactase)

Decreased surface area (e.g. intestinal resection)

Osmotic diarrhoea (lollies, gum, mints containing sorbitol, laxatives)

Increased fluid secretion

Infectious: bacterial endotoxins (e.g. cholera, Escherichia coli, Shigella, Salmonella, Staphylococcus, Clostridium difficile, viral agents [rotavirus] and parasitic agents [Giardia lamblia])

Hormonal: vasoactive intestinal polypeptide secretion from adenoma of the pancreas; gastrin secretion caused by Zollinger-Ellison syndrome; calcitonin secretion from carcinoma of the thyroid

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

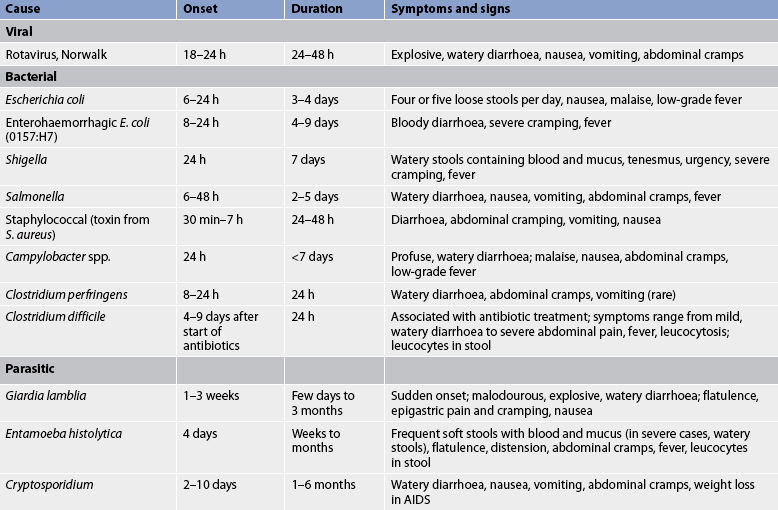

Diarrhoea may be acute or chronic. Acute diarrhoea most commonly results from infection. Causes of acute infectious diarrhoea are listed in Table 42-1. Bacterial or viral infection of the intestine may result in symptoms such as explosive watery diarrhoea, tenesmus (spasmodic contraction of the anal sphincter with pain and a persistent desire to defecate) and abdominal cramping or pain. Liquid stools can also lead to perianal skin irritation. Systemic manifestations include fever, nausea, vomiting and malaise. Leucocytes, blood and mucus may be present in the stool, depending on the causative agent (see Table 42-1). Acute diarrhoea is often self-limiting in adults. Symptoms continue until the irritant or causative agent is excreted. The epithelial cells lining the lumen of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract regenerate after the inflammatory response resolves.

Diarrhoea is considered chronic when it lasts for at least 4 weeks.1 Chronic diarrhoea can produce life-threatening dehydration, electrolyte disturbances (e.g. hypokalaemia) and acid–base imbalances (metabolic acidosis). Infants and the elderly are particularly vulnerable to chronic diarrhoea. Malabsorption and malnutrition are also sequelae of chronic diarrhoea.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Accurate diagnosis and management require a thorough history, physical examination and laboratory testing. The patient should be asked about recent travel to foreign countries, medication use, diet, previous surgery, interpersonal contacts and a family history of diarrhoea. Deficiencies in iron and folate occur with longstanding diarrhoea and can result in anaemia. Increased haemoglobin, haematocrit and serum urea levels suggest that fluid deficits and electrolyte levels may be abnormal. Infectious diarrhoea may be associated with an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count. Stools are examined for the presence of blood, mucus, WBCs and parasites, and cultures are performed to identify infectious organisms.

In a patient with chronic diarrhoea, measurement of stool electrolytes, pH and osmolality helps determine whether the diarrhoea is related to decreased fluid absorption or increased fluid secretion (secretory diarrhoea). Measurement of stool fat and undigested muscle fibres may indicate fat and protein malabsorption conditions, including pancreatic insufficiency. Elevated serum levels of GI hormones, such as vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and gastrin, are present in some patients with secretory diarrhoea. Stools can also be examined for faecal calprotectin, a neutrophil granulocyte cytosol protein secreted from neutrophils. Calprotectin is released from neutrophils in the bowel lumen as a result of bowel wall inflammation and, since it can be easily measured in faecal samples, it is a useful test to help identify organic bowel disease against functional bowel disease such as irritable bowel syndrome in patients with chronic diarrhoea.2 Colonoscopy is used to examine the mucosa and obtain biopsies for histological examination. Upper and lower radiological studies with barium contrast may be helpful in detecting mucosal disease or structural abnormalities.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Treatment depends on the cause. Foods and medications that cause diarrhoea should be avoided. Acute diarrhoea from infectious causes is usually self-limiting. The major concern is fluid and electrolyte replacement and resolution of the diarrhoea. Oral solutions containing glucose and electrolytes may be sufficient to replace losses from mild diarrhoea, but parenteral administration of fluids, electrolytes, vitamins and nutrition is necessary if losses are severe.

Antidiarrhoeal agents are sometimes given to coat and protect mucous membranes, absorb irritating substances, inhibit GI motility, decrease intestinal secretions and decrease central nervous system stimulation of the GI tract (see Table 42-2). They are contraindicated in the treatment of infectious diarrhoea because they potentially prolong exposure to the infectious organism, and are used cautiously in inflammatory bowel disease because of the danger of toxic megacolon (colonic dilation greater than 5 cm). Regardless of the cause of diarrhoea, antidiarrhoeal drugs should be given only for a short period of time.

| Type | Mechanism of action | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Demulcent | Soothes, coats and protects mucous membranes | Kaolin,* pectin, hyoscyamine sulphate, hyoscine hydrobromide, atropine sulfate;*† aluminium hydroxide |

| Anticholinergic | Inhibits GI motility | Atropine sulphate,*† diphenoxylate with atropine sulphate, loperamide*‡ |

| Antisecretory | Decreases intestinal secretion | Octreotide, a synthetic analogue of somatostatin |

| Opioid | Decreases CNS stimulation of GI tract motility and secretion; directly inhibits GI motility | Kaolin, pectin, aluminium hydroxide, codeine phosphate |

CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal.

*Also absorbent, which contributes to the adhesiveness of the stool.

†Also inhibits bacterial activity and is used prophylactically to prevent traveller’s diarrhoea.

‡Has cholinergic and non-cholinergic actions.

Antibiotics are rarely used to treat acute diarrhoea since the infection generally runs its course. Some antibiotics kill the normal bowel flora, thereby allowing pathogenic organisms to flourish. For example, patients receiving antibiotics (e.g. clindamycin, ampicillin, amoxycillin, cephalosporin) are susceptible to Clostridium difficile infection, which is a serious bacterial infection. C. difficile causes mild-to-severe diarrhoea, abdominal cramping and fever. C. difficile infection can also result in pseudomembranous enterocolitis and intestinal perforation. Immunosuppressed patients and the elderly are particularly susceptible. C. difficile is a particularly hazardous nosocomial infection because hospitalised patients are often immunosuppressed, antibiotic therapy is common and C. difficile spores can survive for up to 70 days on inanimate objects. The spores have been found on commodes, telephones, thermometers, bedside tables, floors and other objects in patients’ rooms as well as on the hands of healthcare workers. Healthcare workers who do not adhere to infection control precautions can transmit C. difficile from patient to patient. In many cases, the infection resolves when antibiotic therapy ceases. If not, metronidazole is the first line of therapy. Vancomycin is used if metronidazole is ineffective.3

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE INFECTIOUS DIARRHOEA

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE INFECTIOUS DIARRHOEA

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

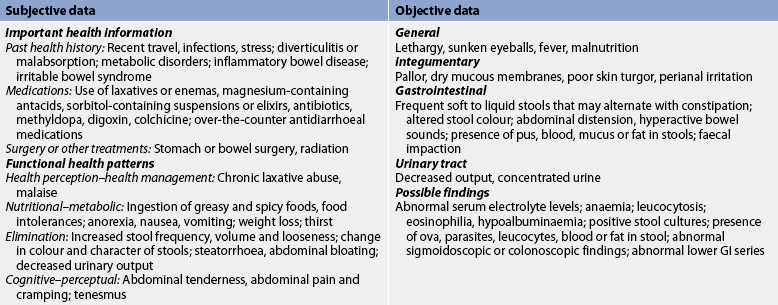

Nursing assessment begins with a thorough history and physical examination (see Table 42-3). The patient is asked to describe the stool pattern and associated symptoms. Questions focus on the duration, frequency, character and consistency of stool. A medication history includes the use of antibiotics, laxatives, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) and other drugs known to cause diarrhoea. Recent travel, stress, and health and family illnesses should be discussed. The patient is asked about eating habits, appetite and food intolerances, especially milk and dairy products, and food preparation practices.

Physical examination includes vital signs, and height and weight measurements. The patient’s skin should be inspected for signs of dehydration (poor turgor, dryness and areas of breakdown). The abdomen is inspected for distension, auscultated for bowel sounds and palpated for tenderness.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

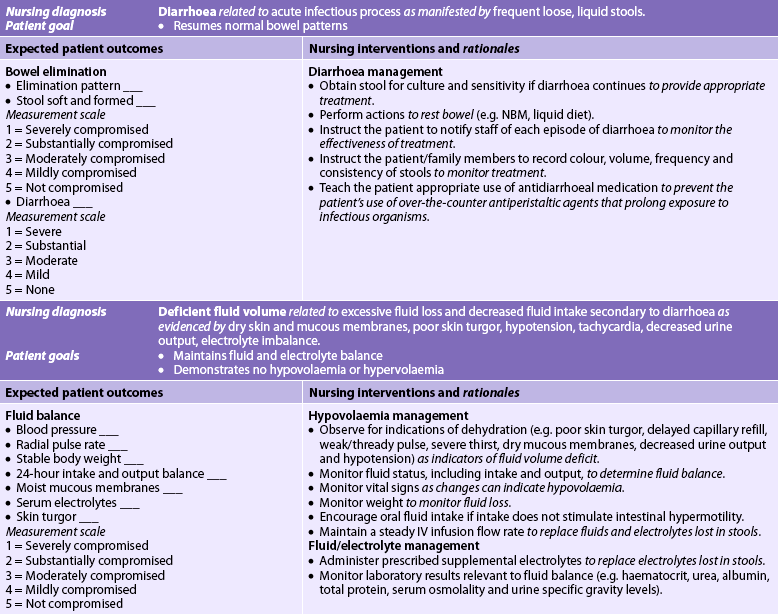

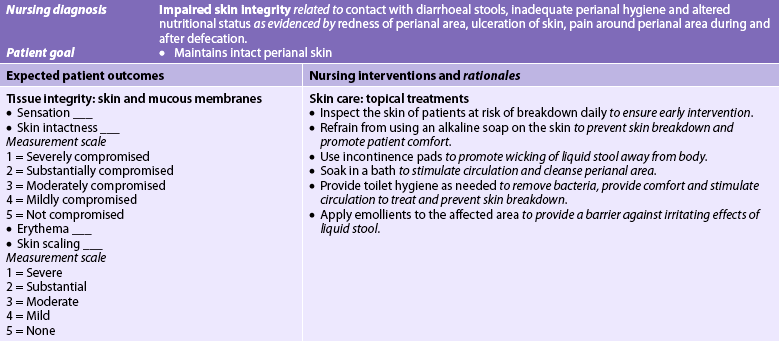

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with acute infectious diarrhoea may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 42-1.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with diarrhoea will: (1) not transmit the microorganism causing the infectious diarrhoea; (2) cease having diarrhoea and resume normal bowel patterns; (3) have normal fluid and electrolyte and acid–base balance; (4) have normal nutritional status; and (5) have no perianal skin breakdown.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

All cases of acute diarrhoea should be considered infectious until the cause is known. Strict infection control precautions are necessary to prevent the infection from spreading to others. Hands should be washed before and after contact with each patient and gloves worn when body fluids of any kind are handled. The patient and family should be taught the principles of hygiene, infection control precautions and the potential dangers of an illness that is infectious to themselves and others. Proper food handling, cooking and storage should be discussed with the patient suspected of having infectious diarrhoea.

Patients with C. difficile should be placed in a private room and gloves and gowns should be worn for all care. An individual stethoscope and patient thermometer should be kept in the room. Objects in the room must be considered contaminated and can be disinfected with a 4% solution of household bleach. Strict hand-washing is vital and patients and their families should be taught ways to prevent the spread of infection.

Faecal incontinence

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Faecal incontinence, the involuntary passage of stool, occurs when the normal structures that maintain continence are disrupted. Normally, faecal contents pass from the sigmoid colon into the rectum, causing rectal distension. Sensory (stretch) receptors in the muscles surrounding the rectum are stimulated. This causes a reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter and contraction of the external anal sphincter. Sensory receptors in the epithelium of the anal canal are able to distinguish between solid, liquid and gas. The combination of contraction of the abdominal muscles, relaxation of the pelvic muscles, squatting (which straightens the anorectal angle) and voluntary relaxation of the external anal sphincter allows for elimination of faeces. Problems with motor function (contraction of muscles) or sensory function (ability to perceive the presence of stool or to experience the urge to defecate) or their combination can result in faecal incontinence. Weakness or disruption of the internal or external anal sphincter, damage to the pudendal nerve or other nerves that innervate the anorectum, damage to the anal tissue and weakness of or trauma to the puborectalis muscle all contribute to incontinence.

For women, obstetric trauma is the most common cause of sphincter disruption. However, faecal incontinence usually develops years later when the woman is in her 50s or older. Constipation and diarrhoea are common risk factors for faecal incontinence (see Box 42-2). Faecal incontinence can occur secondary to faecal impaction, which is an accumulation of hardened faeces in the rectum or sigmoid colon that cannot be expelled. Faecal incontinence caused by faecal impaction is a common problem in older adults with limited mobility.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

The diagnosis and effective management of faecal incontinence require a thorough health history and physical examination with appropriate diagnostic studies. The patient is asked about the number of incontinent episodes weekly and stool consistency and volume. A rectal examination should be performed. Faecal impaction, internal prolapse, increased perineal descent, poor anal sphincter squeeze pressure and rectocele can be detected during a rectal examination. If the impaction is higher in the colon, an abdominal X-ray or a computed tomography (CT) scan may be helpful. However, a CT scan is rarely used for this due to the high radiation dosage. Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy may identify inflammation, tumours, fissures and other colonic pathological conditions. Anorectal manometry, electromyography, pudendal nerve latency testing and ultrasound imaging of the anal sphincter may be used in the diagnosis. Defaecography also provides useful information about difficulties with defecation and continence.4

Treatment of incontinence depends on the underlying cause. If faecal incontinence is related to non-infectious diarrhoea, bulking agents are the first choice for treating diarrhoea. If bulking agents are ineffective, antidiarrhoeal agents such as loperamide may be useful in reducing diarrhoea and increasing sphincter tone.

Faecal incontinence from faecal impaction usually resolves after manual removal of the hard faeces and cleansing enemas. To prevent recurrence, a high-fibre diet, along with increased fluid intake, should be given unless contraindicated.

Dietary fibre supplements or bulk-forming laxatives can improve continence by increasing stool bulk, firming consistency and promoting the sensation of rectal filling. Perianal pouching or disposable pads or briefs provide containment of stool, protect skin and promote comfort and dignity.

Biofeedback therapy is aimed at improving awareness of the rectal sensation and coordination of the internal and external anal sphincters, and increasing the strength of contraction of the external sphincter.4 Biofeedback training requires adequate mental status and motivation to learn. Components of biofeedback include education, reinforcement and concentration. It is a safe, painless and relatively inexpensive treatment for faecal incontinence, but further investigation is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of various biofeedback programs.4

Surgery (e.g. sphincter repair procedures) should be considered only when conservative treatment fails, in cases of full-thickness prolapse and when the sphincter needs repair. A colostomy is sometimes necessary.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: FAECAL INCONTINENCE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: FAECAL INCONTINENCE

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Faecal incontinence is embarrassing, uncomfortable and irritating to the skin. An assessment of the patient’s general condition and mental alertness is necessary to identify the best alternative for managing the patient with faecal incontinence. The nurse should ask about bowel patterns before the incontinence developed, usual bowel habits, stool consistency and current symptoms, including pain during defecation, blood or mucus in the stool and a feeling of incomplete evacuation. The nurse determines whether the patient has defecation urgency and is aware of leaking stool. Further assessment includes questions about the coexistence of urinary incontinence, a history of multiple or traumatic childbirths, previous anorectal surgery or injury, and any loss of sensation in the perineal region.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with faecal incontinence include, but are not limited to, the following:

• bowel incontinence related to inability to control bowel function

• self-care deficit (toileting) related to inability to manage bowel evacuation voluntarily

• risk of situational low self-esteem related to inability to control bowel movements

• risk of impaired skin integrity related to incontinence of stool

• social isolation related to inability to control bowel functions.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with faecal incontinence will: (1) have normal bowel control; (2) maintain perianal skin integrity; and (3) avoid self-esteem problems related to problems with bowel control.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Prevention and treatment of faecal incontinence may be managed by implementing a bowel-training program. Bowel training is effective in many patients because once the bowel is empty the rectum does not fill until the next day. If there is no stool, the person is continent. Bowel elimination occurs at regular intervals in most people, and the nurse uses knowledge of the patient’s regular pattern to time elimination. The patient is put on a bedpan, assisted to a bedside commode or walked to the bathroom at a regular time daily to promote bowel regularity. A good time to establish this pattern is within 30 minutes after breakfast. Most people experience an urge to defecate following the first meal of the day because of the gastrocolic reflex. If the usual bowel habits differ from this pattern, efforts should be made to adhere to the patient’s individual timing.

If these techniques are ineffective in re-establishing bowel regularity, a bisacodyl or glycerine suppository, or a small phosphate enema may be administered 15–30 minutes before the usual evacuation time. These preparations stimulate the anorectal reflex and should be discontinued when a regular pattern is re-established. They are particularly useful for patients with overflow faecal incontinence as a consequence of faecal loading.

Maintenance of skin integrity is of utmost importance, especially in the bedridden and older adult patient. Nursing management may necessitate the use of drainage tubes or catheters, incontinence briefs and meticulous skin care. Rectal tubes and catheters are avoided because they can decrease responsiveness of the rectal sphincter and cause ulceration of the rectal mucosa. Incontinence briefs may be helpful in maintaining skin integrity if changed frequently, but can be demeaning and humiliating to the patient. Meticulous cleaning after each stool is essential for skin integrity. The skin is cleaned with a mild soap and rinsed to remove faeces, the area is dried and a protective skin barrier cream is applied. Because the patient may have several stools each day, maintaining skin integrity is an important task for the nurse and the family.

Constipation

Normal bowel movement frequency varies from three bowel movements daily to one bowel movement every three days.Constipation can be defined as a decrease in the frequency of bowel movements from what is ‘normal’ for the individual; hard, difficult-to-pass stools; a decrease in stool volume; and/or retention of faeces in the rectum. Since individuals vary, it is important to compare current symptoms with the patient’s normal pattern of elimination. Changes in bowel habits may also indicate bowel obstruction produced by a tumour.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Common causes of constipation include insufficient dietary fibre, inadequate fluid intake, decreased physical activity and ignoring the defecation urge. Many medications, especially narcotics, cause constipation. Constipation occurs with many diseases that slow GI transit and hamper neurological function, such as diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis. Emotions affect the GI tract, and both depression and stress can contribute to constipation (see Box 42-3). For many patients with constipation, however, it is not possible to identify the underlying cause.

Some patients believe that they are constipated if they do not have a daily bowel movement. This can result in chronic laxative use and subsequent cathartic colon syndrome. In this condition, the colon becomes dilated and atonic (lacking muscle tone) and the person cannot defecate without the laxative.

Ignoring the urge to defecate for a prolonged period can cause the muscles and mucosa of the rectum to become insensitive to the presence of faeces. In addition, the prolonged retention of faeces results in drying of stool due to water absorption. The harder and drier the faeces, the more difficult it is to expel.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The clinical presentation of constipation may vary from a chronic discomfort to an acute event mimicking an ‘acute abdomen’. Stools are absent or hard, dry and difficult to pass. Other clinical manifestations are presented in Box 42-4. Haemorrhoids are the most common complication of chronic constipation. They result from venous engorgement caused by repeated Valsalva manoeuvres (straining) and venous compression from hard impacted stool.

The Valsalva manoeuvre, which occurs during straining to pass a hardened stool, may cause serious problems in patients with heart failure, cerebral oedema, hypertension and coronary artery disease. During straining, the patient inspires deeply and holds the breath while contracting abdominal muscles and bearing down. This increases both intraabdominal and intrathoracic pressures and reduces venous return to the heart. The heart slows temporarily (bradycardia), the cardiac output is decreased and there is a transient drop in arterial pressure. When the patient relaxes, thoracic pressure falls, resulting in a sudden flow of blood into the heart, increased heart rate and an immediate rise in arterial pressure. These changes may be fatal for the patient who cannot compensate for the sudden increased blood flow returning to the heart.

In the presence of constipation, or faecal impaction secondary to constipation, colonic perforation may occur. Perforation, which is life-threatening, causes abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever and an elevated WBC. An abdominal X-ray shows the presence of free air, which is diagnostic of perforation. Rectal mucosal ulcers and fissures may also occur as a result of stool stasis or straining. Diverticulosis is another potential complication of chronic constipation and is described later in this chapter. These complications are most common in older patients.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

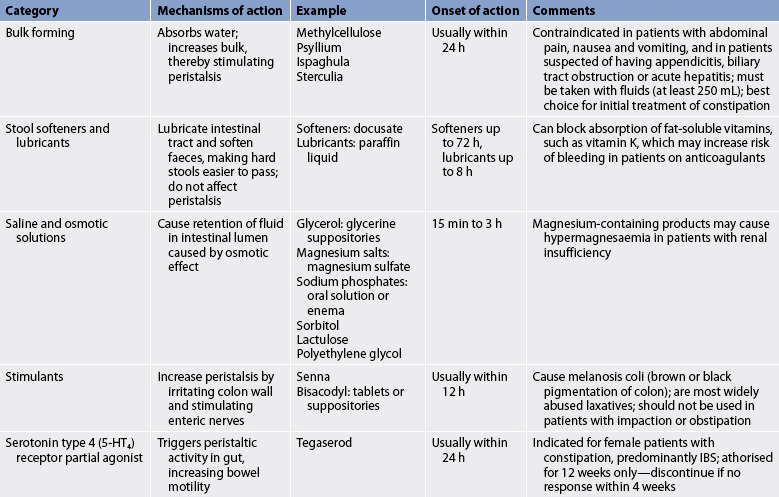

A thorough history and physical examination should be performed so that the underlying cause of constipation can be identified and treatment started. A sudden change in bowel habit is a ‘red flag’ symptom that needs investigation to exclude pathology such as colon cancer, particularly in the presence of rectal bleeding. In these cases abdominal X-rays, barium enema, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and anorectal manometry may be helpful in the diagnosis. Routinely there is little role for diagnostic tests (other than a plain abdominal X-ray) in the assessment of constipation.5 Many cases of constipation can be prevented by increasing dietary fibre, fluid intake and exercise. Laxatives (see Table 42-4) and enemas may be used to treat acute constipation, but are used cautiously because overuse leads to chronic constipation. People who continue to use laxatives and enemas eventually become unable to have a bowel movement without them.

The choice of laxative or enema depends on the severity of the constipation and the health of the individual. Management should start with the simplest laxative first, such as a stool bulking agent.5 The healthcare provider may prescribe daily bulk-forming preparations to prevent constipation because they work like dietary fibre and do not cause tolerance. Stool softeners are also used to prevent constipation. Stimulant laxatives such as bisacodyl and senna are more potent and thus are more likely to cause tolerance and mucosal changes and should be used mainly in the treatment of acute constipation. Polyethylene glycol, magnesium sulphate and lactulose are osmotic laxatives that can be used for both acute and chronic constipation where simpler laxatives and dietary modification have not been effective. Polyethylene glycol is an inert substance that moves through the gastrointestinal tract without being absorbed and relives constipation by rehydrating the stool rather than stimulating the GI tract. It is therefore particularly useful in patients with chronic constipation, as it is less likely to cause tolerance. It is not available on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, but can be purchased as an over-the-counter medication.

Enemas are fast-acting and beneficial for the immediate treatment of constipation, but must be used cautiously. Soap and water enemas produce inflammation of the colon mucosa, tap-water enemas can lead to water intoxication and sodium phosphate enemas may cause electrolyte imbalances in patients with cardiac and renal problems.

Biofeedback therapy may benefit patients who are constipated as a result of anismus (uncoordinated contraction of the anal sphincter during straining). For the patient in whom perceived constipation is related to rigid beliefs regarding bowel function, the nurse should initiate a discussion about these beliefs with the patient. Appropriate information on normal bowel function needs to be given and discussed along with the adverse consequences of excessive use of laxatives and enemas.

A patient with severe constipation related to bowel motility or mechanical disorders may require more intensive treatment. Diagnostic studies such as anorectal manometry, GI tract transit studies and sigmoidoscopic rectal biopsies should be performed before treatment. In a patient with unrelenting constipation, a subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis is occasionally considered.

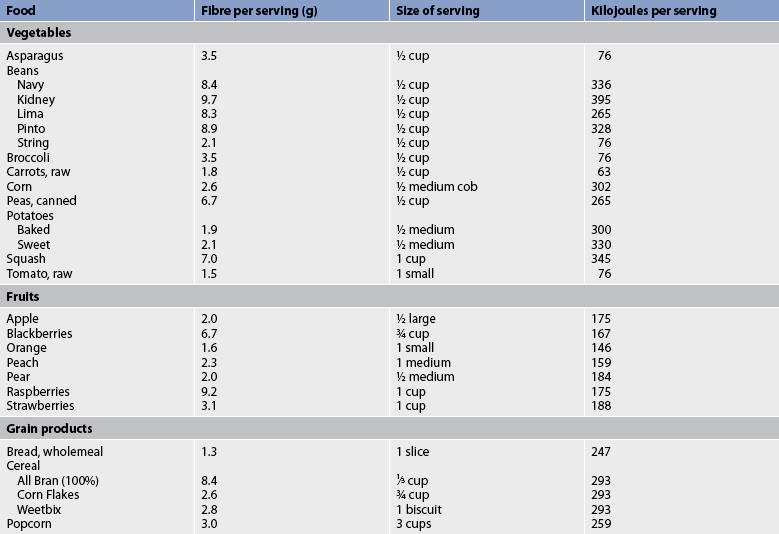

Nutritional therapy

Diet is an important factor in the prevention of constipation. Many patients experience an improvement in their symptoms when they increase their intake of dietary fibre and fluids. Dietary fibre is found in plant foods: fruits, vegetables and grains (see Table 42-5). Wheat bran and prunes are especially effective for preventing and treating constipation.

TABLE 42-5 High-fibre foods*

* High-fibre foods are especially recommended for patients with diverticulosis, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, haemorrhoids, colon cancer, atherosclerosis, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus.

Insoluble fibre, which is found in higher concentrations in whole wheat, bran and flaxseed meal, remains essentially unchanged as it moves through the GI tract, until it reaches the colon where fermentation occurs. Dietary fibre adds to the stool bulk directly and by attracting water. Large, bulky stools decrease pressure within the lumen of the colon and move through the colon much more quickly than small stools. Therefore, stool frequency increases and constipation is prevented. A fluid intake of approximately 3000 mL daily is important because much of the stool bulk and softening comes from the attraction of water to the stool.

The person who eats large amounts of dietary fibre and does not drink enough fluids will have dry, hard stools that are difficult to pass. The recommended fluid intake may be contraindicated in the patient with cardiac disease or renal insufficiency or failure. The patient’s understanding of their dietary needs and the importance of dietary fibre is important to ensure compliance. Patients should be told that initially fibre may increase gas production because of fermentation in the colon, but that this effect decreases with use.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CONSTIPATION

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CONSTIPATION

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

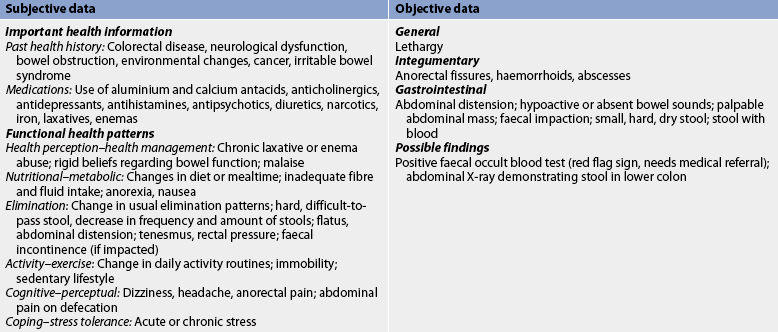

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from a patient with constipation are presented in Table 42-6.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnosis for the patient with constipation includes, but is not limited to, the following:

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with constipation will: (1) increase dietary intake of fibre and fluids; (2) increase physical activity; (3) have the passage of soft, formed stools; and (4) not have any complications, such as bleeding haemorrhoids.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Nursing management should be based on the patient’s symptoms (see Box 42-4) and the assessment of the patient (see Table 42-6). An important nursing role is teaching patients the importance of dietary measures to prevent constipation. A patient and family teaching guide for constipation is presented in Box 42-5. Emphasis should be placed on maintaining a high-fibre diet, increasing fluid intake and following a regular exercise program. The patient should be taught to establish a regular time to defecate and not to suppress the urge to defecate. The patient should be discouraged from using laxatives and enemas to achieve faecal elimination.

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

The following are teaching guidelines for the patient and family:

1. Eat dietary fibre. Eat 20–30 g of fibre per day. Gradually increase the amount of fibre eaten over 1–2 weeks. Fibre softens hard stool and adds bulk to stool, promoting evacuation.

2. Drink fluid. Drink 2–3 L per day. Drink water or fruit juices; avoid caffeinated coffee, tea and cola. Fluid softens hard stools; caffeine stimulates fluid loss through urination.

3. Exercise regularly. Walk, swim or do other exercise at least three times per week. Contract and relax abdominal muscles when standing or by doing sit-ups to strengthen muscles and prevent straining. Exercise stimulates bowel motility and moves stool through the intestine.

4. Establish a regular time to defecate. First thing in the morning or after the first meal of the day is a good time because people often have the urge to defecate at this time.

5. Do not delay defecation. Respond to the urge to have a bowel movement as soon as possible. Delaying defecation results in hard stools and a decreased ‘urge’ to defecate. Water is absorbed from stool by the intestine over time. The intestine becomes less sensitive to the presence of stool in the rectum.

6. Record your bowel elimination pattern. Develop a habit of recording when you have a bowel movement on your calendar. Regular monitoring of bowel movement will assist in early identification of a problem.

7. Avoid laxatives and enemas. Do not overuse laxatives and enemas because they cause dependence. People who overuse them are unable to have a bowel movement without them.

Proper position is important when defecating. Defecation is easiest when the person is sitting on a commode with the knees higher than the hips. It is extremely difficult to defecate while sitting on a bedpan. For a patient in bed, the bedpan should be placed under the patient and the head of the bed should be elevated as high as the patient can tolerate. For the person who can sit on a toilet, a footstool may be placed in front of the toilet. Placing the feet on the footstool promotes flexion of the thighs, which assists in defecation.

Most people are embarrassed by the sights, sounds and smell of defecation and the nurse should ensure that patients have as much privacy as possible.

The patient with poor muscle tone should be encouraged to exercise the abdominal muscles and can be taught to contract the abdominal muscles several times a day. Sit-ups and straight leg raises can also be used to improve abdominal muscle tone.

Patients taking bulking products need to be taught to follow product recommendations in terms of fluid intake. Similar to increasing fibre intake, patients may initially experience an increase in flatus, which will decrease with time.

Acute abdominal pain

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

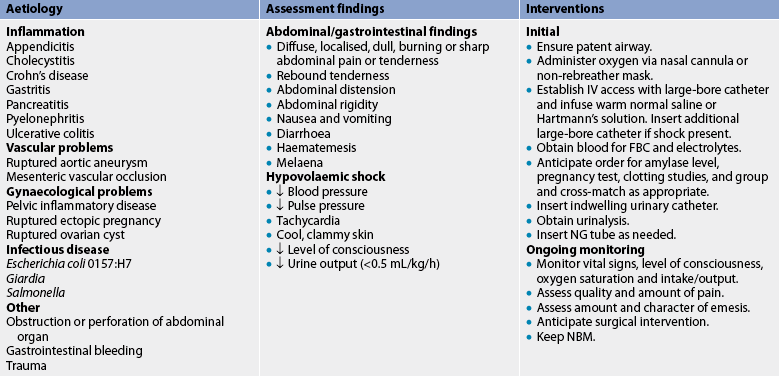

Acute abdominal pain is a symptom of many different types of tissue injury and can arise from damage to abdominal or pelvic organs and blood vessels. The most common causes of an acute onset of abdominal pain are listed in Box 42-6. Certain causes (e.g. haemorrhage, obstruction and rupture) are life-threatening because large fluid losses from the vascular space lead to shock. Other problems require only conservative medical treatment.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Pain is the most common presenting symptom of an acute abdominal problem. The patient may also complain of nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, flatulence, fatigue, fever and an increase in abdominal girth.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES ANDCOLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT

Many disorders must be ruled out before a diagnosis is confirmed. Diagnosis begins with a complete history and physical examination. A complete description of the pain (frequency, timing, duration, location) and accompanying symptoms provides vital clues about the origin of the problem. Physical examination should include a rectal and pelvic examination in addition to an inspection of the abdomen. A full blood count (FBC), urinalysis, abdominal X-ray and an electrocardiogram are done initially, along with an ultrasound or CT scan. Pregnancy tests should be done in women of childbearing age with acute abdominal pain to rule out ectopic pregnancy. The healthcare provider should attempt to make a differential diagnosis because many causes of abdominal pain do not require surgery (see Box 42-6).

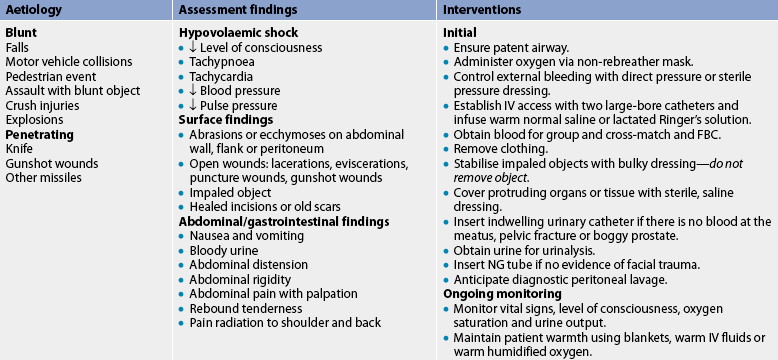

The emergency management of the patient with acute abdominal pain is presented in Table 42-7. The goal of management is to identify and treat the cause, and monitor and treat complications, especially shock. It was previously thought that pain medication should be withheld because analgesics might obscure progression of the clinical manifestations and impede diagnosis. It is now known that appropriate pain management that does not result in altered consciousness can decrease diffuse pain and abdominal rigidity and help localise the pain. This can lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment.

TABLE 42-7 Acute abdominal pain

FBC, full blood count; IV, intravenous; NBM, nil by mouth; NG, nasogastric.

In the case of acute abdominal pain, surgery can be a diagnostic as well as a therapeutic procedure. An exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy, in which an opening is made through the abdominal wall into the peritoneal cavity, is done after a careful examination of the patient. This procedure is done when ‘look and see’ is better than ‘wait and see’. If the cause of acute abdominal pain can be surgically removed (e.g. inflamed appendix) or surgically repaired (e.g. ruptured abdominal aneurysm), surgery is considered definitive therapy.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Vital signs should be taken immediately. Increased pulse and decreasing blood pressure (BP) are indicative of hypovolaemia and/or shock. An elevated temperature may indicate an inflammatory or infectious process. Intake and output measurement provides essential information about the adequacy of vascular volume. The abdomen should be inspected for distension, masses, abnormal pulsation, rashes, scars and pigmentation changes. Bowel sounds should be auscultated. Bowel sounds that are diminished or absent in a quadrant may indicate a complete bowel obstruction, acute peritonitis or paralytic ileus. Palpation should be gentle.

A thorough assessment of the patient’s symptoms should be made to determine the onset, location, intensity, duration, frequency and character of pain. The nurse should determine whether the pain has spread or moved to new locations (quadrants), as well as what makes the pain worse or better. In addition, the nurse should determine whether the pain is associated with other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, changes in bowel and bladder habits, or vaginal discharge in women. Assessment of vomiting should include the amount, colour, consistency and odour of the emesis. Bowel patterns and habits should also be carefully assessed.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with acute abdominal pain include, but are not limited to, the following:

• acute pain related to inflammation of the peritoneum and abdominal distension

• risk of deficient fluid volume related to collection of fluid in the peritoneal cavity secondary to inflammation or infection

• imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to anorexia, nausea and vomiting

• anxiety related to pain and uncertainty of cause or outcome of condition.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with acute abdominal pain will have: (1) resolution of inflammation; (2) relief of abdominal pain; (3) freedom from complications (especially hypovolaemic shock); and (4) normal nutritional status.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

General care for the patient involves management of fluid and electrolyte imbalances, pain and anxiety. The quality and intensity of pain is measured at regular intervals, and medication and other comfort measurements are administered. A calm environment, confident attitude and prompt provision of information help allay anxiety. The nurse continues to monitor vital signs, intake and output, and level of consciousness, which are key indicators of hypovolaemic shock. If the patient has an exploratory laparotomy or other surgery, the nurse provides pre- and postoperative care.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Preoperative care

Preoperative care

Preoperative care includes the emergency care of the patient described in Table 42-7 and general care of the preoperative patient (see Ch 17).

Postoperative care

Postoperative care

Postoperative care depends on the type of surgical procedure performed. The increased use of laparoscopic procedures has reduced the risk of postoperative complications related to wound care, and postoperative paralytic ileus is rare. Early ambulation and advancement of diet result in shorter hospital stays. A general nursing care plan for the postoperative patient is presented in Chapter 19.

A nasogastric (NG) tube with low suction may be used to empty the stomach of secretions and gas to prevent gastric dilation. However, the NG tube is used less frequently due to the increased use of laparoscopic procedures. If the upper GI tract has been entered, drainage from the NG tube may be dark brown to dark red for the first 12 hours. Later it should be light yellowish brown, or it may have a greenish tinge because of the presence of bile. If a dark-red colour continues or if bright-red blood is observed, the doctor should be notified at once of the possibility of haemorrhage. ‘Coffee ground’ granules in the drainage are due to the presence of blood that has been chemically acted on by acidic gastric secretions.

The NG tube is checked frequently for patency. If the tube is obstructed with mucus, sediment or blood clots, the nurse should request approval to irrigate it with 20–30 mL of normal saline solution as necessary. Repositioning the tube may facilitate drainage. When bowel sounds are auscultated, the healthcare provider usually orders the removal of the NG tube. An accurate record of intake and output, including emesis and gastric drainage, is essential. The nurse assesses serum electrolyte values and acid–base balance because prolonged gastric suctioning can result in loss of sodium chloride, potassium, water and hydrochloric acid (HCl).

Routine mouth care and nasal care are essential. The patient tends to breathe through the mouth while the NG tube is in place and mouth breathing dries the mucosal membranes of the mouth. The tube irritates nasal mucosa, leading to increased secretions and crusting. Parenteral fluids are administered to provide the patient with fluids and electrolytes until bowel sounds return. Occasionally, ice chips may be ordered because they aid in the flow of saliva and prevent a dry mouth. When bowel sounds return, fluids and food are increased gradually.

Nausea and vomiting are not uncommon after abdominal surgery, and may be caused by the surgery, decreased peristalsis or pain medications. Antiemetics such as prochlorperazine, metoclopramide or ondansetron may be ordered. Management of nausea and vomiting are discussed in Chapter 41. Swallowed air and decreased peristalsis from decreased mobility, manipulation of abdominal organs during surgery and anaesthesia can lead to abdominal distension and gas pains. Early ambulation helps to restore peristalsis and eliminate flatus and gas pain. If gas pain is severe, the doctor sometimes prescribes a medication (e.g. metoclopramide) to stimulate peristalsis. The surgeon should be informed of abdominal distension and rigidity. Gradually, as intestinal activity increases, distension and gas pain disappear.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

Preparation for discharge begins soon after surgery. Instructions to be given to the patient and family should include any modifications in activity, care of the incision, diet and drug therapy. Clear liquids are given initially after surgery and, if tolerated, the patient progresses to a regular diet.

Early ambulation speeds recovery, but normal activities should be resumed gradually, with planned rest periods. After surgery the patient is generally instructed not to lift anything greater than a few kilograms. The patient should be aware of possible complications after surgery and should notify their doctor immediately if vomiting, pain, weight loss, incisional drainage or changes in bowel function occur.

CHRONIC ABDOMINAL PAIN

Chronic abdominal pain may originate from abdominal structures or may be referred from a site with the same or a similar nerve supply. Common causes include irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), diverticulitis, peptic ulcer disease, chronic pancreatitis, hepatitis, cholecystitis, pelvic inflammatory disease and vascular insufficiency. (Some of these disorders are discussed in this chapter.)

Diagnosis of the cause of chronic abdominal pain begins with a thorough history and description of specific pain characteristics. The character and severity, location, duration and onset of pain should be determined. The assessment also includes the relationship of pain to meals, defecation and activity, and factors that increase or decrease the pain. Chronic abdominal pain is often described as dull, aching or diffuse.

Endoscopy, CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), laparoscopy and barium studies may be used in the patient evaluation. Treatment for chronic abdominal pain is comprehensive and directed towards palliation of symptoms using non-opiate analgesics and antiemetics, as well as psychological or behavioural therapies (e.g. relaxation therapies).

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a symptom complex characterised by intermittent and recurrent abdominal pain and stool pattern irregularities. It is classified as IBS with diarrhoea, IBS with constipation, and IBS with alternating diarrhoea and constipation. Other common symptoms include abdominal distension, excessive flatulence, bloating, a continual defecation urge, urgency and a sensation of incomplete evacuation. IBS is a common problem affecting approximately 10–15% of the Western population.6 In Western societies, approximately two to three times as many women as men seek healthcare services for IBS. Stress, psychological factors, prior gastroenteritis and specific food intolerances have been identified as major factors that precipitate IBS symptoms.

The abdominal pain or discomfort associated with IBS is most likely due to increased visceral sensitivity. That is, the presence of stool or gas in the GI tract stimulates visceral afferent fibres, which results in a perception of discomfort or pain. Several neurochemicals, including serotonin, are likely to be involved in the bowel symptoms of diarrhoea, constipation and pain sensitivity.7

There are no specific physical findings with IBS. The diagnosis is made when the patient displays the characteristic symptoms and other conditions are ruled out. The key to accurate diagnosis is a thorough history and physical examination. Emphasis should be on symptoms, past health history (including psychosocial factors such as physical or sexual abuse), family history, and drug and diet history. Diagnostic tests should be selectively used to rule out more serious disorders with symptoms similar to those of IBS, such as colorectal cancer, peptic ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disease and malabsorption disorders (e.g. coeliac disease). Symptom-based criteria for IBS have been standardised and are referred to as the Rome criteria. The Rome III criteria include the following: abdominal discomfort or pain and marked change in bowel habit for at least 6 months with symptoms experienced on at least 3 days a month within the last 3 months, and at least two of the following characteristics: (1) pain relieved with defecation; (2) onset of pain associated with a change in stool frequency; and (3) onset of pain associated with a change in stool appearance.8

The healthcare provider should establish a trusting relationship with the patient at the onset of treatment. The patient should be encouraged to verbalise their concerns and anxiety. Since treatment is often focused on symptoms, patients are encouraged to keep a diary of symptoms, diet and episodes of stress to help identify factors that seem to trigger the symptoms.6 Healthcare providers have traditionally prescribed a diet containing at least 20 g per day of dietary fibre (see Table 42-5) or a bulking agent such as psyllium. Unfortunately, fermentation of large amounts of fibre can increase bloating and gas pain (at least initially), two symptoms that are already problematic for many patients with IBS.

The patient whose primary symptoms are abdominal distension and increased flatulence should be advised to eliminate common gas-producing foods (e.g. broccoli, cabbage) from the diet and to substitute yoghurt for milk products to help determine if there is lactose intolerance. Antispasmodic agents (e.g. mebeverine hydrochloride) may be tried before meals to alleviate the pain associated with the ingestion of food, but their effectiveness has been questioned.9 Loperamide, a synthetic opioid that decreases intestinal transit and enhances intestinal water absorption and sphincter tone, has been found effective for IBS patients with diarrhoea.9 Other therapies include cognitive behavioural therapy, relaxation and stress management techniques, acupuncture, hypnosis and Chinese herbs.10 No single therapy has been found to be effective for all patients with IBS. More recently, the implementation of a diet low in fermentable, short-chain carbohydrates (a low ‘FODMAP’ diet) has been found helpful in some patients with IBS who persist with functional symptoms such as pain, bloating and altered stool frequency.11

Abdominal trauma

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Injuries to the abdominal area most often occur as a result of blunt trauma or penetration injuries. Blunt trauma commonly occurs with motor vehicle accidents and falls, and may not be obvious since it does not leave an open wound. Both compression (e.g. direct blow to the abdomen) and shearing injuries (e.g. rapid deceleration in a motor vehicle crash allows some tissues to move forwards while others are held stationary) occur with blunt trauma. Penetrating injuries occur when a gunshot or stabbing produces an obvious, open wound into the abdomen. Regardless of whether it is a blunt or penetration injury, the abdominal organs are damaged. Solid organs (liver, spleen) bleed profusely when injured. Damage to hollow organs such as the bladder, stomach and intestines causes peritonitis when the contents spill into the peritoneal cavity.

Common injuries of the abdomen include lacerated liver, ruptured spleen, pancreatic trauma, mesenteric artery tears, diaphragm rupture, urinary bladder rupture, great vessel tears, renal injury and stomach or intestine rupture. These injuries can result in massive blood loss and hypovolaemic shock. Surgery is performed as early as possible to repair the damaged organs and to stop the bleeding. Common sequelae of intraabdominal trauma are peritonitis and sepsis, particularly when the bowel is perforated. (Abdominal trauma is discussed in Ch 68.)

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Careful assessment provides important clues to the type and severity of injury. Clinical manifestations of abdominal trauma are: (1) guarding and splinting of the abdominal wall (indicating peritonitis); (2) a hard, distended abdomen (indicating intraabdominal bleeding); (3) decreased or absent bowel sounds; (4) contusions, abrasions or bruising over the abdomen; (5) abdominal pain; (6) pain over the scapula caused by irritation of the phrenic nerve by free blood in the abdomen; (7) haematemesis or haematuria; and (8) signs of hypovolaemic shock (see Table 42-8). If the patient was in a motor vehicle accident, a contusion or abrasion across the lower abdomen indicates that the seat belt probably did damage to the internal organs. Ecchymosis around the umbilicus (Cullen’s sign) or flanks (Grey Turner’s sign) may indicate retroperitoneal haemorrhage. Loss of bowel sounds occurs with peritonitis. Bowel sounds are heard in the chest when the diaphragm ruptures. Auscultation of bruits signals arterial or aortic damage.12 Intraabdominal injuries are often associated with low rib fractures, a fractured femur, fractured pelvis and thoracic injury. If any of these injuries is present, the patient should be observed for abdominal trauma.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Laboratory tests include a baseline FBC and urinalysis. Even when bleeding, the patient’s haemoglobin and haematocrit will remain normal because fluids are lost at the same rate as the red blood cells (RBCs). Deficiencies will be evident after fluid resuscitation begins. Blood in the urine may be a sign of damage to the kidneys or bladder. Additional laboratory tests include arterial blood gases, prothrombin time, electrolytes, serum urea and creatinine, and group and cross-match (in anticipation of possible blood transfusions). Ultrasound is often used because it is portable and non-invasive. Abdominal and chest CT can identify specific injury sites, but its use requires that the patient be stable enough to transport to radiology.

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage may also be used.12 Peritoneal lavage is performed by inserting a large angiocatheter or peritoneal dialysis catheter into the abdomen after a local anaesthetic has been injected. A syringe is attached to the catheter, and an attempt is made to gently aspirate any blood. If less than 10 mL of blood is aspirated, a litre of saline solution is then infused into the abdomen and drained. The fluid is observed for gross abnormalities, especially blood, and is sent to the laboratory for microscopic evaluation. Positive findings include: (1) RBC count greater than 10 × 1012/L; (2) WBC greater than 500 × 109/L; (3) high amylase level; and (4) presence of bacteria, bile or faecal material. If the results are positive, immediate surgery is indicated. If the results are negative, continued observation of the patient is warranted.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

Emergency management of abdominal trauma focuses on establishing a patent airway and adequate breathing, fluid replacement and prevention of hypovolaemic shock (see Table 42-8). Intravenous (IV) lines are inserted, and volume expanders or blood are given if the patient is hypotensive. An NG tube may be inserted to decompress the stomach and prevent aspiration. Frequent ongoing assessment is necessary to detect deterioration in the condition and the necessity of surgery. An impaled object should never be removed until skilled care is available. Removal may cause further injury and bleeding.

Regardless of the type of injury, physical evidence of abdominal trauma in a patient who is haemodynamically unstable mandates immediate laparotomy. Otherwise, the laparotomy may be delayed. If surgery is performed, the postoperative nursing care is similar to the care of the patient after laparotomy.

Appendicitis

Appendicitis is an inflammation of the appendix, a narrow blind tube that extends from the inferior part of the caecum. Appendicitis occurs in 7–12% of the world’s population. It can occur at any age but is most common in young adults.13

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The most common causes of appendicitis are obstruction of the lumen by a faecalith (accumulated faeces), foreign bodies, tumour of the caecum or appendix, or intramural thickening caused by excessive growth of lymphoid tissue. Obstruction results in distension, venous engorgement and the accumulation of mucus and bacteria, which can lead to gangrene and perforation (see Fig 42-1).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Symptoms vary and diagnosis can be difficult. Appendicitis typically begins with periumbilical pain, followed by anorexia, nausea and vomiting. The pain is persistent and continuous, eventually shifting to the right lower quadrant and localising at McBurney’s point (located halfway between the umbilicus and the right iliac crest). Further assessment of the patient reveals localised tenderness, rebound tenderness and muscle guarding. The patient usually prefers to lie still, often with the right leg flexed. Low-grade fever may or may not be present, and coughing aggravates pain. Rovsing’s sign may be elicited by palpation of the left lower quadrant, causing pain to be felt in the right lower quadrant. Complications of acute appendicitis are perforation, peritonitis and abscesses.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Examination of the patient includes a complete history and physical examination (particularly palpation of the abdomen) and a differential WBC. The WBC may be elevated with appendicitis. A urinalysis may be done to rule out genitourinary conditions that mimic the manifestations of appendicitis. The gold standard for diagnosis is either an ultrasound or a CT scan.

How long after gastrointestinal surgery should patients remain NBM?

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Clinical question

For patients undergoing gastrointestinal (GI) surgery (P), does enteral feeding within 24 hours postoperative (I) versus maintaining NBM (nil by mouth) status (C) reduce postoperative mortality (O)?

Implications for nursing practice

• Before surgery, patients are often malnourished due to disease process, vomiting and preparations for diagnostic testing or surgery. Severe malnourishment increases morbidity and mortality risks.

• Consult with surgeons and dieticians in advance for beginning enteral feeding in the first 24-h postoperatively (see Fig 65-1).

P, Patient population of interest; I, intervention or area of interest; C, comparison of interest or comparison group; O, outcome(s) of interest.

If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, the appendix can rupture and the resulting peritonitis can be fatal. The treatment of appendicitis is immediate surgical removal (appendicectomy) if the inflammation is localised. If the appendix has ruptured and there is evidence of peritonitis or an abscess, conservative treatment consisting of antibiotic therapy and parenteral fluids is given for 6–8 hours before the appendicectomy in order to prevent sepsis and dehydration.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: APPENDICITIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: APPENDICITIS

The patient with abdominal pain is encouraged to see a healthcare provider and to avoid self-treatment. Laxatives and enemas are especially dangerous because the resulting increased peristalsis may cause perforation of the appendix. Until a healthcare provider sees the patient, nothing should be taken by mouth (NBM) to ensure that the stomach is empty in the event that surgery is needed. Surgery, generally laparoscopically, is performed as soon as the diagnosis is made.

Postoperative nursing management is similar to postoperative care of the patient after laparotomy. In addition, the patient is observed for evidence of peritonitis. Ambulation begins the day of surgery or the first postoperative day. The diet is advanced as tolerated. The patient is usually discharged on the first or second postoperative day, and normal activities are resumed 2–3 weeks after surgery.

Peritonitis

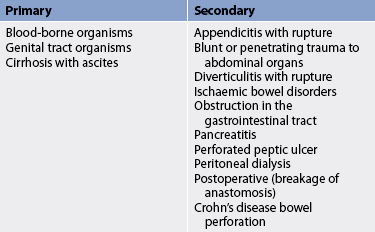

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Peritonitis results from a localised or generalised inflammatory process of the peritoneum. The causes of peritonitis are listed in Table 42-9. Primary peritonitis occurs when blood-borne organisms enter the peritoneal cavity. For example, the ascites that occurs with cirrhosis of the liver provides an excellent liquid environment for bacteria to flourish. Secondary peritonitis is much more common. It occurs when abdominal organs perforate or rupture and release their contents (bile, enzymes, bacteria) into the peritoneal cavity. Common causes include a ruptured appendix, perforated gastric or duodenal ulcer, severely inflamed gall bladder, small bowel perforation and trauma from gunshot or knife wounds. Intestinal contents and bacteria irritate the normally sterile peritoneum and produce an immediate chemical peritonitis that is followed a few hours later by a bacterial peritonitis. Patients who use continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis are also at high risk. (Peritoneal dialysis is described in Ch 46.) No matter what the cause, the resulting inflammatory response leads to massive fluid shifts (peritoneal oedema) and adhesions as the body attempts to ward off the infection.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Abdominal pain is the most common symptom of peritonitis. A universal sign of peritonitis is tenderness over the involved area. Rebound tenderness, muscular rigidity and spasm are other major signs of irritation of the peritoneum. Patients may lie very still and take only shallow respirations because movement causes pain. Abdominal distension or ascites, fever, tachycardia, tachypnoea, nausea, vomiting and altered bowel habits may also be present. These manifestations vary depending on the severity and acuteness of the underlying cause. Complications of peritonitis include hypovolaemic shock, sepsis, intraabdominal abscess formation, paralytic ileus and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Peritonitis can be fatal if treatment is delayed.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

An FBC is done to determine elevations in the WBC and haemoconcentration from fluid shifts (see Box 42-7). Peritoneal aspiration may be performed and the fluid analysed for blood, bile, pus, bacteria, fungus and amylase content. An X-ray of the abdomen may show dilated loops of bowel consistent with paralytic ileus, free air if perforation has occurred, or air and fluid levels if an obstruction is present. Ultrasound and CT scans may be useful in identifying the presence of ascites, small bowel perforation and abscesses. Laparoscopy may be helpful in the patient without ascites. Direct examination of the peritoneum can be obtained, along with biopsy specimens for diagnosis.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Surgery is usually indicated to locate the cause, drain purulent fluid and repair the damage. Appropriate antibiotics are given to treat the infection. Patients with milder cases of peritonitis or those who are poor surgical risks may be managed non-surgically. Treatment consists of antibiotics, NG suction, analgesics and IV fluid administration. Patients who require surgery need preoperative preparation as previously described.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PERITONITIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PERITONITIS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Assessment of the patient’s pain, including the location, is important and may help in determining the cause of peritonitis. The patient should be assessed for the presence and quality of bowel sounds, increasing abdominal distension, abdominal guarding, nausea, fever and manifestations of hypovolaemic shock.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with peritonitis include, but are not limited to, the following:

• acute pain related to inflammation of the peritoneum and abdominal distension

• risk of deficient fluid volume related to fluid shifts into the peritoneal cavity secondary to trauma, infection or ischaemia

• imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to anorexia, nausea and vomiting

• anxiety related to uncertainty of cause or outcome of condition and pain.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with peritonitis will have: (1) resolution of inflammation; (2) relief of abdominal pain; (3) freedom from complications (especially hypovolaemic shock); and (4) normal nutritional status.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

The patient with peritonitis is extremely ill and needs skilled supportive care. An IV line is inserted to replace vascular fluids lost to the peritoneal cavity and as an access for antibiotic therapy. The patient is monitored for pain and response to analgesic therapy. The patient may be positioned with knees flexed to increase comfort. The nurse should provide rest and a quiet environment. Sedatives may be given to allay anxiety.

Accurate monitoring of fluid intake and output and electrolyte status is necessary to determine replacement therapy. Vital signs are monitored frequently. Antiemetics may be administered to decrease nausea and vomiting and prevent further fluid and electrolyte losses. The patient is NBM and may need an NG tube to decrease gastric distension and further leakage of bowel contents into the peritoneum. Low-flow oxygen may be needed.

If the patient has an open surgical procedure, drains are inserted to remove purulent drainage and excessive fluid. Postoperative care of the patient is similar to the care of the patient with an exploratory laparotomy.

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is an inflammation of the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine. Clinical manifestations include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal cramping and distension. Fever, increased WBC, and blood or mucus in the stool may be present. Causative agents are varied (see Table 42-1). Most cases are self-limiting and do not require hospitalisation. However, older adults and chronically ill patients may be unable to consume sufficient fluids orally to compensate for fluid loss. Until vomiting has ceased, the patient should be on NBM status. If dehydration occurs, IV fluid replacement may be necessary. As soon as tolerated, fluids containing glucose and electrolytes should be given. If the causative agent is identified, appropriate antibiotic and antimicrobial drugs are given.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: GASTROENTERITIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: GASTROENTERITIS

Accurate monitoring of intake and output is important for successful replacement of lost fluid. Strict medical asepsis and infection control precautions should be instituted when indicated. The patient is instructed in the importance of proper food handling and the preparation of food to prevent infections such as salmonellosis and trichinosis.

Symptomatic nursing care is given for nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. The importance of rest and increased fluid intake should be stressed. The nurse should assess complaints of pain, vomiting and diarrhoea because gastroenteritis is often confused with appendicitis. To allay the patient’s apprehension, the nurse should explain that gastroenteritis usually runs an acute course with no sequelae.

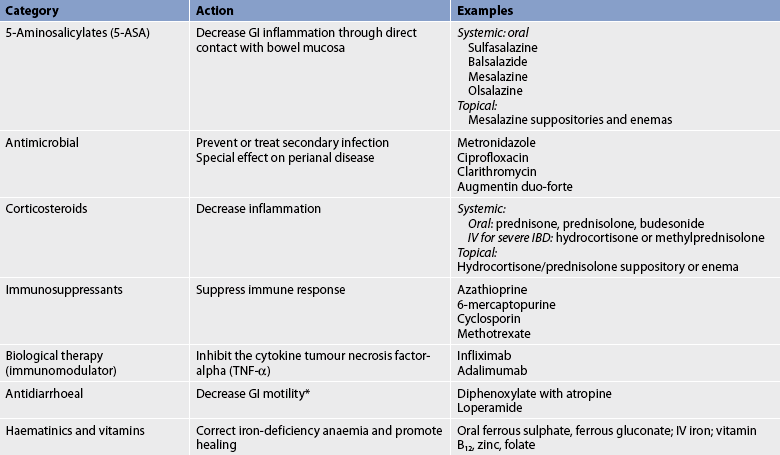

Inflammatory bowel disease

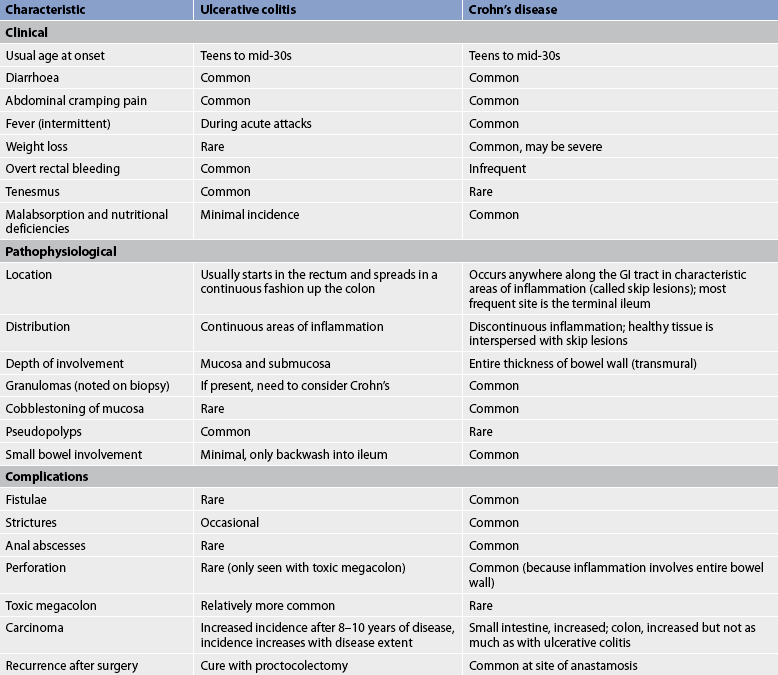

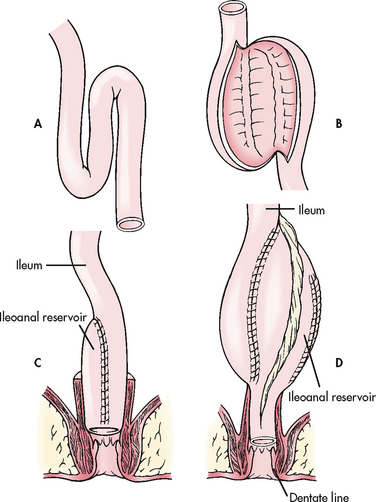

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are immunologically related disorders that are referred to as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (see Table 42-10). Both diseases are characterised by chronic inflammation of the intestine with periods of remission interspersed with periods of exacerbation. The cause is unknown and there is no medical cure; therefore, treatment relies on medications to treat the acute inflammation, avoid or manage complications and maintain remission. Surgery is reserved for patients who are unresponsive to medications or who develop life-threatening complications. In treatment of refractory ulcerative colitis, a curative total colectomy (removal of the whole colon) with formation of either an end ileostomy or a restorative ileo-anal pouch may be performed.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

IBD is an autoimmune disease. Although an antigen probably initiates the inflammation, the actual tissue damage is due to an overactive, inappropriate and sustained inflammatory response. Both genetic and environmental factors seem to play a role in IBD. The prevalent theory is that an unidentified, possibly bacterial antigen, which is usually innocuous, stimulates a poorly regulated immune response in genetically susceptible people.14 According to this theory, a genetically susceptible person who is never exposed to the antigen will not become ill, and a person who is not genetically susceptible will not develop IBD even if exposed to the antigen.

Both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease commonly occur during the teenage years and early adulthood, but both have a second peak in the sixth decade of life. Both are more prevalent in Caucasians and in industrialised regions of the world. An increasing incidence is being noted in Asia as this region industrialises.15

Studies of twins and family members provide support for a genetic influence in IBD. Family members of patients with Crohn’s disease not only are at increased risk of Crohn’s disease, but also have an increased risk of ulcerative colitis, and vice versa. Genetic research studies have led to the identification of a number of susceptibility genes including CARD15, DLG5, OCTN1 and 2, NOD1, HLA and TLR4.15 The CARD15 gene, on chromosome 16, has been associated with Crohn’s disease, and is undoubtedly replicated most widely and is most understood; however, this gene is only present in a minority of people with IBD. Genetic research in IBD is advancing understanding of the complexities of the disease and has started to unravel some of the interactions between genetic risk factors and environmental risk factors in IBD. Future genetic research may also enable the targeting of therapies for patients according to their genetic make-up, as genes are thought to influence response to and toxicity from therapies.14,16

No single antigen that initiates IBD has been found. Various bacteria have been proposed and some patients respond favourably to antibiotic therapy, although no studies show persistent long-term improvement with treatment with antibiotics. The normal inflammatory response is altered in patients with IBD and this is now known to be genetically determined.17

Certain criteria are used to differentiate ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s disease, but the diseases have much in common and a clear differentiation between the two cannot be made in about 10% of cases. The fact that people with ulcerative colitis commonly have a relative with Crohn’s disease, and vice versa, supports the existence of a common genetic influence.

Although symptoms are often the same (diarrhoea, bloody stools, weight loss, abdominal pain, fever and fatigue), the pattern of inflammation is different for the two diseases (Figs 42-2 and 42-3 illustrate the differences between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis). In Crohn’s disease the inflammation is transmural (involving all layers of the bowel wall). Crohn’s disease can occur anywhere in the GI tract from the mouth to the anus, but occurs most commonly in the terminal ileum and colon. Furthermore, segments of normal bowel can occur between diseased portions, so-called skip lesions (see Table 42-10). Typically, ulcerations are deep and longitudinal and penetrate between islands of inflamed oedematous mucosa, causing the classic cobblestone appearance (see Fig 42-3). Strictures at the areas of inflammation may cause bowel obstruction. Since the inflammation goes through the entire wall, microscopic leaks can allow bowel contents to enter the peritoneal cavity and form abscesses or peritonitis.

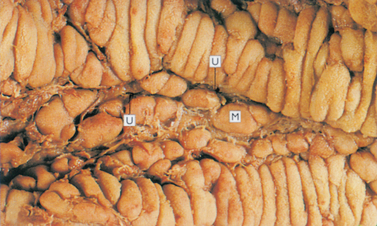

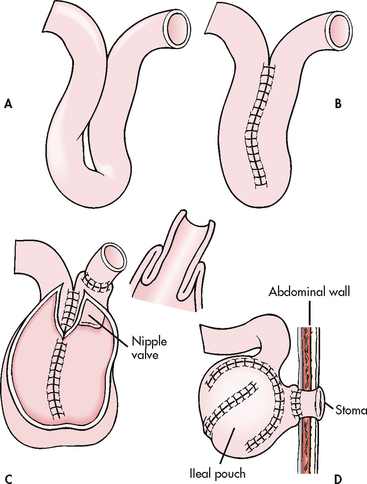

Figure 42-2 Crohn’s disease. The mucosa in Crohn’s disease demonstrates a cobblestone pattern as a result of fissured ulcers (U) with intervening areas of oedematous mucosa (M).

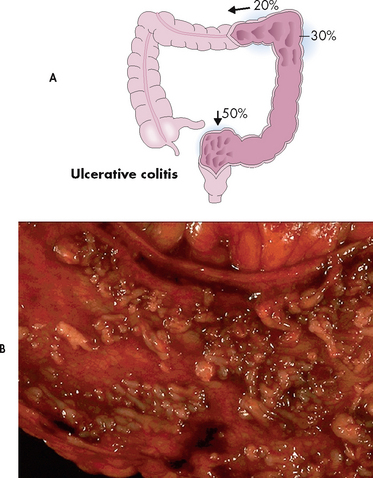

Figure 42-3 Ulcerative colitis. A, Approximately 50% of cases of ulcerative colitis occur in the rectosigmoid area, with 30% of cases extending to hepatic flexure. In 20% of cases ulcerative colitis is diffuse. B, The mucosa has been ulcerated away in a severe case of ulcerative colitis.

Source: Craft J, Gordon G, Tiziani A. Understanding pathophysiology. Sydney: Elsevier; 2011.

Is inflammatory bowel disease a risk factor for osteoporosis?

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Clinical question

Do adults (P) with IBD (I) have a higher risk of osteoporosis (0) than adults without inflammatory bowel disease (C)?

Critical appraisal and synthesis of evidence

• 40 studies (n = 48,000) with a majority being observations from IBD clinics.

• 50% of patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis had bone density levels within osteopenic or osteoporotic range.

• Hip fracture risk related to osteoporosis was greater in persons with IBD than the general population.

Implications for nursing practice

• Counsel patients with IBD to modify osteoporosis risk factors where possible, such as smoking cessation.

• Collaborate with healthcare providers to encourage osteoporosis treatment and prevention measures such as weight-bearing exercises and dietary or supplemental calcium and vitamin D.

P, Patient population of interest; I, intervention or area of interest; C, comparison of interest or comparison group; O, outcome(s) of interest.

Lewis NR, Scott BB. Guidelines for osteoporosis in inflammatory bowel disease and coeliac disease. British Society of Gastroenterology. Available at www.bsg.org.uk/images/stories/clinical/ost_coe_ibd.pdf, 2007. accessed 26 June 2010.

Sometimes these leaks form tracts or fistulae between adjacent organs. Fistulae can develop between adjacent areas of bowel, between the bowel and the bladder and between the bowel and the vagina, and can also form a tract through the skin to the outside of the body. Urinary tract infections are usually the first sign of a bowel–bladder fistula and faeces is sometimes seen in the urine. A fistula between the bowel and vagina allows the passage of flatus and faeces to leak out through the vagina, and if there is a fistula onto or towards the skin (cutanous fistula) faeces or bowel contents can leak onto the skin, or cause a subcutaneous abscess.

Ulcerative colitis, another inflammatory bowel condition, usually starts in the rectum and extends a variable distance proximally towards the caecum. Although there is sometimes mild inflammation in the terminal ileum (backwash ileitis), ulcerative colitis is a disease of the colon and rectum (see Fig 42-3). Unlike Crohn’s disease where healthy tissue is interspersed with inflamed tissue, ulcerative colitis spreads in a continuous pattern. In ulcerative colitis, the inflammation and ulcerations occur only in the mucosal layer of the bowel wall. Since it does not extend through all bowel wall layers, fistulae and abscesses are rare. Water and electrolytes are absorbed when the mucosal epithelium is healthy but cannot be absorbed through inflamed mucosa. Therefore, bloody diarrhoea with large fluid and electrolyte losses is a characteristic feature of damage to the colonic mucosa epithelium. Breakdown of cells results in protein loss through the stool. Where there is regeneration in areas of inflamed mucosa, pseudopolyps form. These are tongue-like projections of mucosa into the bowel lumen.

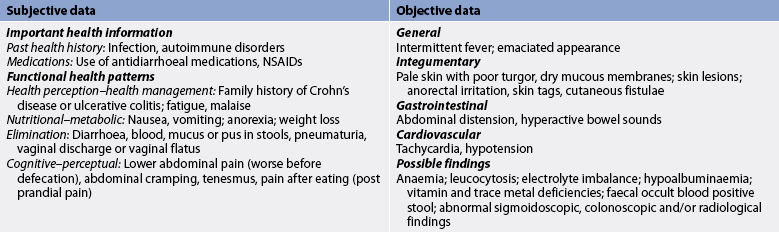

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Both forms of IBD are chronic disorders with mild-to-severe acute exacerbations that occur at unpredictable intervals over many years. With Crohn’s disease, diarrhoea and colicky abdominal pain are common symptoms. If the small intestine is involved, weight loss may occur due to malabsorption. A mass is sometimes felt in the right iliac fossa. Overt rectal bleeding sometimes occurs with Crohn’s disease, although not as often as with ulcerative colitis. In addition, patients may have systemic symptoms such as fever.

About 90% of patients with ulcerative colitis have mild-to-moderately severe disease. The primary symptoms of ulcerative colitis are rectal bleeding and abdominal pain, with bloody diarrhoea being common in patients with more extensive colitis. Pain may vary: mild to moderate lower abdominal cramping associated with diarrhoea is common, whereas severe, constant pain is rare but may be associated with acute perforations. With mild disease, diarrhoea may consist of one to two semiformed stools daily that contain small amounts of blood. The patient may have no other systemic manifestations. In moderate ulcerative colitis there is increased stool output (four to five stools per day), increased bleeding and systemic symptoms (fever, malaise, anorexia). In severe cases, diarrhoea is bloody, contains mucus and occurs 10–20 times a day. In addition, fever, weight loss greater than 10% of total body weight, anaemia, tachycardia and dehydration are present.

COMPLICATIONS

Patients with IBD experience both local (confined to the GI tract) and systemic (extraintestinal) complications. GI tract complications include haemorrhage, strictures, perforation (with possible peritonitis), fistulae and colonic dilatation. Colonic dilatation greater than 6 cm, associated with signs of systemic toxicity, is called toxic megacolon. Patients with toxic megacolon are at a high risk of perforation and may need an emergency colectomy.18

Chronic blood loss or haemorrhage may lead to anaemia, and is corrected with iron supplements and blood transfusions. Perineal abscess and fistulae occur in up to a third of patients with Crohn’s disease,17 and some patients develop skin tags around the anus.

Nutritional problems are especially common with Crohn’s disease when the terminal ileum is involved. Bile salts and vitamin B12 are exclusively absorbed in the terminal ileum. Thus, disease at this location can result in fat malabsorption and vitamin B12 deficiency and anaemia.

Toxic megacolon is more common with ulcerative colitis, but strictures and fistulae occur most commonly with Crohn’s disease. Patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis are at an increased risk of colorectal cancer and those with Crohn’s disease are at an increased risk of small bowel cancer.18,19 Regular surveillance colonoscopy is recommended for patients with IBD after 8–10 years of disease, particularly those with extensive colonic disease, to detect dysplasia and/or colorectal cancer. Systemic complications of IBD, including fever, anorexia and malaise, are due to the general inflammatory response and are seen more commonly in Crohn’s disease.