Chapter 50 NURSING ASSESSMENT: reproductive system

1. Describe the structures and functions of the male and female reproductive systems.

2. Summarise the functions of the major hormones essential for the functioning of the male and female reproductive systems.

3. Explain the physiological changes of a man and a woman during the stages of sexual response.

4. Relate the age-related changes of the male and female reproductive systems to the differences in assessment findings.

5. Select the significant subjective and objective data related to the male and female reproductive systems and information about sexual function that should be obtained from a patient.

6. Select appropriate techniques to use in the physical assessment of the male and female reproductive systems.

7. Differentiate between normal and common abnormal findings of a physical assessment of the male and female reproductive systems.

8. Describe the purpose, significance of results and nursing responsibilities related to diagnostic studies of the male and female reproductive systems.

Structures and functions of the male and female reproductive systems

The reproductive system of both males and females consists of primary (or essential) organs and secondary (or accessory) organs. The primary reproductive organs are referred to as gonads. The female gonads are the ovaries; the male gonads are the testes. The primary responsibility of the gonads is the secretion of hormones and the production of gametes (ova and sperm). Secondary or accessory organs are responsible for transporting and nourishing the ova and sperm, as well as preserving and protecting the fertilised eggs.

MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

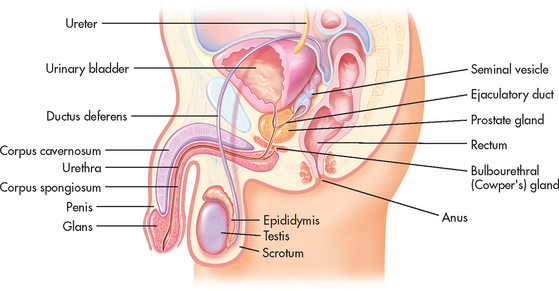

The three primary roles of the male reproductive system are: (1) production and transportation of sperm; (2) deposition of sperm in the female reproductive tract; and (3) secretion of hormones. The primary reproductive organs in the male are the testes. Secondary reproductive organs include ducts (epididymis, ductus deferens, ejaculatory duct and urethra), sex glands (prostate gland, Cowper’s glands, and seminal vesicles) and the external genitalia (scrotum and penis) (see Fig 50-1).1

Testes

The paired testes are ovoid, smooth, firm organs measuring 3.5–5.5 cm long and 2–3 cm wide. They are within the scrotum, which is a loose protective sac composed of a thin outer layer of skin over a tough connective tissue layer. Within the testes, coiled structures known as seminiferous tubules form spermatozoa (immature sperm). The process of sperm production is called spermatogenesis. Interstitial cells of the testes lie between the seminiferous tubules and produce the male sex hormone testosterone.

Ducts

Sperm formed in the seminiferous tubules move through a series of ducts. These ducts transport the sperm from the testes to the outside of the body. As sperm exit the testes they enter and pass through the epididymis, ductus deferens, ejaculatory duct and urethra.

The epididymis is a comma-shaped structure located on the posterior-superior aspect of each testis within the scrotum (see Figs 50-1 and 50-2). It is a very long, tightly coiled structure that measures about 300 cm in length.1 The epididymis transports the sperm as they mature. Sperm exit the epididymis through a long, thick tube known as the ductus deferens.

The ductus deferens (also known as the vas deferens) is continuous with the epididymis within the scrotal sac. It travels upwards through the scrotum and continues through the inguinal ring into the abdominal cavity. The spermatic cord is composed of a connective tissue sheath that encloses the ductus deferens, arteries, veins, nerves and lymph vessels as it ascends up through the inguinal canal (see Fig 50-2). In the abdominal cavity, the ductus deferens travels up, over and behind the bladder. Posterior to the bladder the ductus deferens joins the seminal vesicle to form the ejaculatory duct (see Fig 50-1).

The ejaculatory duct passes downwards through the prostate gland, connecting with the urethra. The urethra extends from the bladder, through the prostate and ends in a slit-like opening (the meatus) on the ventral side of the glans, the tip of the penis. During the process of ejaculation, sperm travel through the urethra and out of the penis.

Glands

The seminal vesicles, prostate gland and Cowper’s (bulbourethral) glands are the accessory glands of the male reproductive system. These glands produce and secrete seminal fluid (semen), which surrounds the sperm and forms the ejaculate.

The seminal vesicles lie posterior to the bladder and between the rectum and the bladder. The ducts of the seminal vesicles fuse with the ductus deferens to form the ejaculatory ducts that enter the prostate gland. The prostate gland lies beneath the bladder. Its posterior surface is in contact with the rectal wall. The prostate normally measures 2 cm wide and 13 cm long and is divided into right and left lateral lobes and an anteroposterior median lobe. Cowper’s glands lie on each side of the urethra and slightly posterior to it, just below the prostate. The ducts of these glands enter directly into the urethra.

Secretions from the seminal vesicles, prostate and Cowper’s gland make up most of the fluid in the ejaculate. These various secretions serve as a medium for the transport of sperm and create an alkaline, nutritious environment that promotes sperm motility and survival.

External genitalia

The external genitalia consist of the penis and the scrotum. The penis comprises a shaft and a tip, which is known as the glans. The glans is covered by a fold of skin, the prepuce (or foreskin), which forms at the junction of the glans and the shaft of the penis. In circumcised males the prepuce has been removed. The broadened segment of the glans at the junction is the corona. The shaft of the penis consists of erectile tissue composed of the corpus cavernosum, the corpus spongiosum, the fibrous sheath that encases the erectile tissue and the urethra. The skin covering the penis is thin, loose and hairless.

FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

The three primary roles of the female reproductive system are: (1) production of ova (eggs); (2) secretion of hormones; and (3) protection and facilitation of the development of the fetus in a pregnant female. Like the male, the female has primary and secondary reproductive organs. The primary reproductive organs in the female are the paired ovaries. Secondary reproductive organs include ducts (fallopian tubes), the uterus, the vagina, sex glands (Bartholin’s glands and breasts) and the external genitalia (vulva).

Pelvic organs

Ovaries

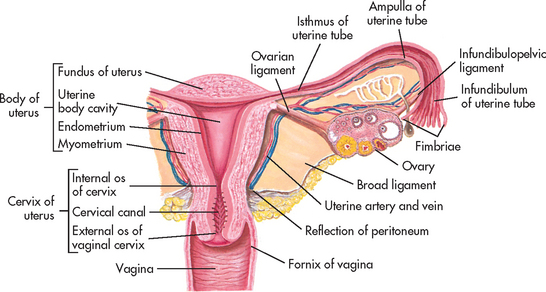

The ovaries are usually located on either side of the uterus, just behind and below the fallopian (uterine) tubes (see Fig 50-3). The ovaries are firm and solid, approximately 1.5 cm wide and 3 cm long. Their functions include ovulation, as well as secretion of the two major reproductive hormones, oestrogen and progesterone. The outer zone of the ovary contains follicles with germ cells, or oocytes. Each follicle contains a primordial (immature) oocyte surrounded by granulosa and theca cells. These two layers protect and nourish the oocyte until the follicle reaches maturity and ovulation occurs. However, not all follicles reach maturity. In a process termed atresia, most of the primordial follicles become smaller and are reabsorbed by the body; thus the number of follicles declines from 2–4 million at birth to approximately 300,000–400,000 at menarche. This number continues to decrease throughout a woman’s reproductive years. Fewer than 500 oocytes are actually released by ovulation during the reproductive years of the normal healthy woman.

Fallopian tubes

Normally, each month during a woman’s reproductive years, one ovarian follicle reaches maturity and the ovum is ovulated, or expelled, from the ovary through the stimulus of the gonadotropic hormones, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH). The ovum then travels up a fallopian tube where fertilisation by sperm may occur, if they are present. An ovum can be fertilised up to 72 hours after its release.

The distal ends of the fallopian tubes consist of finger-like projections called fimbriae that ‘massage’ the ovaries at ovulation to help extract the mature ovum. The tubes, which average 12 cm in length, extend from the fimbriae to the superior lateral borders of the uterus. Fertilisation usually takes place within the outer one-third of the fallopian tubes.

Uterus

The uterus is a pear-shaped, hollow, muscular organ (see Fig 50-4). It is located between the bladder and the rectum. In the mature nulliparous (never pregnant) female, the uterus is approximately 6–8 cm long and 4 cm wide. The uterine walls consist of an outer serosal layer, the perimetrium; a middle muscular layer, the myometrium; and an inner mucosal layer, the endometrium.

The uterus consists of the fundus, body (or corpus) and cervix (see Figs 50-3 and 50-4). The body makes up about 80% of the uterus and connects with the cervix at the isthmus, or neck. The cervix is the lower portion of the uterus that projects into the anterior wall of the vaginal canal. It makes up about 15–20% of the uterus in the nulliparous female. The cervix consists of the ectocervix, the outer portion that protrudes into the vagina, and the endocervix, the canal in the opening of the cervix. The ectocervix is covered with squamous epithelial cells, which give it a smooth, pinkish appearance. The endocervix contains a lining of columnar epithelial cells, which give it a rough, reddened appearance. The junction at which the two types of epithelial cells meet is termed the squamocolumnar junction and contains the optimal types of cells needed for an accurate Papanicolaou (Pap) test to screen for malignancies.

The cervical canal is 2–4 cm long and is relatively tightly closed. The cervix, however, allows sperm to enter the uterus and allows menses to be expelled. The columnar epithelium, under hormonal influence, provides elasticity at labour for the cervix to stretch to allow for the passage of a fetus during the birth process. The entrance of sperm into the uterus is facilitated by mucus produced by the cervix under the influence of oestrogen. Under normal conditions, the cervical mucus becomes watery, stretchy and more abundant at ovulation. This mucus facilitates the passage of sperm into the uterus. The postovulatory cervical mucus, under the influence of progesterone, is thick and inhibits sperm passage.

The anterior and posterior peritoneal covering of the uterus is called the broad ligament. It separates the uterus from the bladder and the rectum but does not provide support for the uterus or the adnexa (ovaries and tubes). The round ligament, which extends anteriorly to the labia majora, provides some support but is easily weakened by pregnancy. The firmest support for the uterus is provided by the uterosacral ligaments, which pull the uterus back and away from the vaginal orifice.

Vagina

The vagina is a tubular structure 8–10 cm long that is lined with squamous epithelium. The secretions of the vagina consist of cervical mucus, desquamated epithelium and, during sexual stimulation, a direct transudate secretion. These fluids help protect against vaginal infection. The muscular and erectile tissue of the vaginal walls allows enough dilation and contraction to accommodate the passage of the fetus during labour, as well as penetration of the penis during intercourse. The anterior vaginal wall lies along the urethra and bladder. The posterior vaginal wall is adjacent to the rectum.

Pelvis

The female pelvis consists of four bones (two pelvic bones, sacrum, coccyx) held together by several strong ligaments. The sections of these bones that lie below the iliopectineal line are very important during birth and are often a factor determining the ability of a woman to deliver a child vaginally. Knowledge of these bones and the landmarks that they form in the pelvis allows the practitioner to estimate pelvic measurements and the potential for a woman’s pelvis to accommodate the birth of a full-term fetus.

External genitalia

The external portion of the female reproductive system (see Fig 50-5), commonly called the vulva, consists of the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, urethral meatus, Skene’s glands, vaginal introitus (opening) and Bartholin’s glands.

The mons pubis is a fatty layer lying over the pubic bone. It contains coarse hair that lies in a triangular pattern. (The male hair pattern is diamond shaped.) The labia majora are folds of adipose tissue that form the outer borders of the vulva. These hair-covered folds contain sweat glands and sebaceous glands. The hairless labia minora form the borders of the vaginal orifice and extend anteriorly to enclose the clitoris.2

The vestibule is a boat-shaped fossa between the labia minora, extending from the clitoris at the anterior end to the vaginal opening at the posterior end. The perineum is the area between the vagina and the anus. The vaginal introitus is surrounded by thin membranous tissue called the hymen. In the adult woman, the hymen usually appears as folds or hymenal tags and separates the external genitalia from the vagina. Although all females have this structure, there is wide anatomical variation in its morphology. At the posterior aspect of the vagina, a tense band of mucous membrane connecting the posterior ends of the labia minora is referred to as the posterior fourchette.

The clitoris is erectile tissue that becomes engorged during sexual excitation. It lies anterior to the urethral meatus and the vaginal orifice and is usually covered by the prepuce.2 Clitoral stimulation is an important part of sexual activity for many women.

Ducts of the Skene’s glands lie alongside the urinary meatus and are thought to help lubricate the urinary meatus.3 The Bartholin’s glands, located at the posterior and lateral aspects of the vaginal orifice, secrete a thin, mucoid material believed to contribute slightly to lubrication during sexual intercourse. These glands are not usually palpable unless sebaceous-like cysts form or in the presence of an infection, such as a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

Breasts

The breasts are a secondary sex characteristic that develops during puberty in response to oestrogen and progesterone. Cyclic hormonal changes lead to regular changes in breast tissue to prepare it for lactation when fertilisation and pregnancy occur. The breasts are also considered a major organ of sexual stimulation.

The breasts extend from the second to the sixth ribs, with the tail reaching the axilla (see Fig 50-6). The fully mature breast is dome shaped and contains a pigmented centre termed the areola. The areolar region contains Montgomery’s tubercles, which are similar to sebaceous glands and assist in lubricating the nipple. During lactation, the alveoli secrete milk. The milk then flows into a ductal system and is transported to the lactiferous sinuses. The nipple contains 15–20 tiny openings through which the milk flows during breastfeeding. The fibrous and fatty tissue that supports and separates the channels of the mammary duct system is primarily responsible for the varying sizes and shapes of the breasts in different individuals.

Figure 50-6 The female breast. A, Sagittal section of the lactating breast. Notice how the glandular structures are anchored to the overlying skin and to the pectoral muscles by the suspensory ligaments of Cooper. Each lobule of glandular tissue is drained by a lactiferous duct that eventually opens through the nipple. B, Anterior view of a lactating breast. In non-lactating breasts, glandular tissue is less evident with adipose tissue comprising most of the breast.

The breast has a rich lymphatic network that drains into axillary and clavicular channels (see Fig 50-6). Superficial lymph nodes are located in the axilla and are accessible to examination. This system is often responsible for the metastasis of a malignant tumour from the breast to other parts of the body.

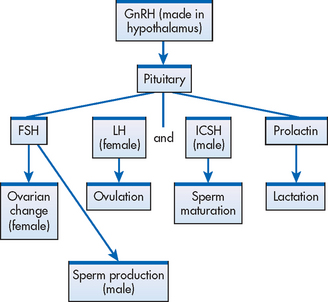

NEUROENDOCRINE REGULATION OF THE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

The hypothalamus, the pituitary gland and the gonads secrete numerous hormones (see Fig 50-7). (Endocrine hormones are discussed in Ch 47.) These hormones regulate the processes of ovulation, spermatogenesis (formation of sperm) and fertilisation, and the formation and function of the secondary sex characteristics. In women, the hormones secreted by the anterior pituitary gland cause cyclical changes in the ovaries. The hypothalamus secretes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the anterior pituitary gland to secrete its hormones, including FSH and LH. LH in males is sometimes called interstitial cell–stimulating hormone (ICSH). The gonadal hormones are oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone.

Figure 50-7 Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. Only the major pituitary hormone actions are depicted. FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; ICSH, interstitial cell–stimulating hormone; LH, luteinising hormone.

In women, FSH production by the anterior pituitary stimulates the growth and maturity of the ovarian follicles necessary for ovulation. The mature follicle produces oestrogen, which in turn suppresses the release of FSH. Another hormone, inhibin, is also secreted by the ovarian follicle and inhibits both GnRH and FSH secretion. In men, FSH stimulates the seminiferous tubules to produce sperm.

LH contributes to the ovulatory process because it causes follicles to complete maturation and undergo ovulation. It also causes the development of a ruptured follicle, or the area on the ovum where the ovum exited during ovulation. The ruptured follicle develops into a corpus luteum from which progesterone is secreted. Progesterone maintains the rich vascular state of the uterus (secretory phase) in preparation for fertilisation and implantation. In men, LH or ICSH triggers testosterone production by the interstitial cells of the testes and thus is essential for the full maturation of sperm. Prolactin has no known function in men. In women, prolactin stimulates the development and growth of the mammary glands. During lactation, it initiates and maintains milk production.

In women, the gonadal hormones oestrogen and progesterone are produced by the ovaries. Small amounts of an oestrogen precursor are also produced in the adrenal cortices. Oestrogen is essential to the development and maintenance of secondary sex characteristics, the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle immediately after menstruation, and the uterine changes essential to pregnancy. The role and importance of oestrogen in men are not well understood. In men, oestrogen is produced predominantly in the adrenal cortex.

Progesterone plays a major role in the menstrual cycle but most specifically in the secretory phase. Like oestrogen, progesterone is involved in the bodily changes associated with pregnancy. Adequate progesterone is necessary to maintain an implanted egg.

The major gonadal hormone of men, testosterone, is produced by the testes. Testosterone is responsible for the development and maintenance of secondary sex characteristics, as well as for adequate spermatogenesis. Androgens are produced in females by the adrenal glands and ovaries in small amounts and are a precursor to both testosterone and oestrogen.

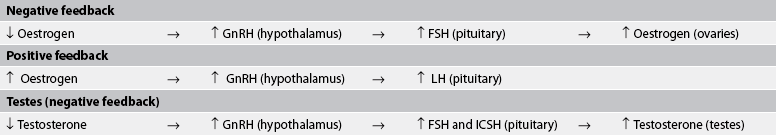

The circulating levels of gonadal hormones are controlled primarily by a negative feedback process. Receptors within the hypothalamus and pituitary are sensitive to the circulating blood levels of the hormones (see Table 50-1). Increased levels of hormones stimulate a hypothalamic response to decrease the high circulating levels. Likewise, low circulating levels provoke a hypothalamic response that increases the low circulating levels. For example, if the circulating level of testosterone in men is low, the hypothalamus is stimulated to secrete GnRH. This triggers the anterior pituitary to secrete greater amounts of FSH and ICSH, which in turn cause an increase in the production of testosterone. The high level of testosterone signals a decrease in the production of GnRH and thus of FSH and ICSH.

TABLE 50-1 Gonadal feedback mechanisms

FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; ICSH, interstitial cell–stimulating hormone; LH, luteinising hormone.

In women, however, there is a slight variation. The circulating levels are controlled through a combination of both a negative and a positive feedback system. A negative feedback control mechanism exists similar to that described previously. When circulating oestrogen levels are low, the hypothalamus is stimulated to increase its production of GnRH. GnRH stimulates the pituitary to secrete greater amounts of FSH and LH, resulting in higher levels of oestrogen production by the ovaries. Reciprocally higher levels of circulating oestrogen result in a decreasing secretion of GnRH and thus a decrease in the secretion of FSH by the pituitary. There is also a positive feedback control mechanism. Thus with increasing levels of circulating oestrogen, a greater level of GnRH is produced, resulting in an increased level of LH from the pituitary. Likewise, lowered levels of oestrogen result in a lowered level of LH.

MENARCHE

Menarche is the first episode of menstrual bleeding, indicating that a female has reached puberty. Menarche usually occurs at approximately 12–13 years of age but can occur as early as 10 years of age in some individuals.4 As puberty approaches, there are changes associated with the elevated rate of oestrogen and progesterone secretion by the ovaries. These changes include the development of breast buds and pubic hair, and later the development of axillary hair. During this time, there is a decrease in the sensitivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis that allows for increased secretion of FSH and LH and a resultant increase in oestrogen. It is during this time that the adult pattern of gonadotropin secretion occurs, resulting in the menstrual cycle. Menstrual cycles are often irregular for the first 1–2 years following menarche because of anovulatory cycles (cycles without ovulation).

MENSTRUAL CYCLE

The major functions of the ovaries are ovulation and the secretion of hormones. These functions are accomplished during the normal menstrual cycle, a monthly process mediated by the hormonal activity of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland and ovaries. Menstruation occurs during each month in which an egg is not fertilised (see Fig 50-8). The endometrial cycle is divided into three phases labelled in relation to uterine and ovarian changes: (1) the proliferative or follicular phase; (2) the secretory or luteal phase; and (3) the menstrual or ischaemic phase. The length of the menstrual cycle ranges from 20 to 40 days, the average being 28 days.

Figure 50-8 Events of the menstrual cycle. The various lines depict the changes in blood hormone levels, the development of the follicles and the changes in the endometrium during the cycle. FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinising hormone.

The menstrual cycle begins on the first day of menstruation, which usually lasts 4–6 days.5 Table 50-2 includes characteristics of the menstrual cycle and related patient teaching. During this time, oestrogen and progesterone levels are low, but FSH levels begin to increase. During the follicular phase, a single follicle matures fully under the stimulation of FSH. (The mechanism that ensures that usually only one follicle reaches maturity is not known.) The mature follicle stimulates oestrogen production, causing a negative feedback with resulting decreased FSH secretion.

Although the initial stage of follicular maturation is stimulated by FSH, complete maturation and ovulation occur only with the presence of LH. When oestrogen levels peak on about the twelfth day of the cycle, there is a surge of LH, which triggers ovulation a day or two later. After ovulation (maturation and release of an ovum), LH promotes the development of the corpus luteum.

The fully developed corpus luteum continues to secrete oestrogen and initiates progesterone secretion. If fertilisation occurs, high levels of oestrogen and progesterone continue to be secreted due to the continued activity of the corpus luteum from stimulation by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). If fertilisation does not take place, menstruation occurs because of a decrease in oestrogen production and progesterone withdrawal.

During the follicular phase, the endometrial lining of the uterus also undergoes change. As larger amounts of oestrogen are produced, the endometrial lining undergoes proliferative changes and there is an increase in cellular growth, including an increase in the length of blood vessels and glandular tissue.

With ovulation and the resulting increased levels of progesterone, the luteal (or secretory) phase begins. In this phase, the blood vessels begin to coil, increasing the surface area of the vascular supply. The glandular tissues mature and secrete a glycogen-rich substance, and the glandular ducts dilate. If the corpus luteum regresses (when fertilisation does not occur) and oestrogen and progesterone levels fall, the endometrial lining can no longer be supported. As a result, the blood vessels contract and tissue begins to slough (fall away). This sloughing results in the menses and the start of the menstrual phase.5

MENOPAUSE

Menopause is the physiological cessation of menses associated with declining ovarian function. It is usually considered complete after 1 year of amenorrhoea (absence of menstruation). (Menopause is discussed in Ch 53.)

PHASES OF SEXUAL RESPONSE

The sexual response is a complex interplay of psychological and physiological phenomena and is influenced by a number of variables, including daily stress, illness and crisis. The changes that occur during sexual excitement are similar for men and women. Masters and Johnson, in their classic work on human sexual response, described the sexual response in terms of the excitement, plateau, orgasmic and resolution phases.6

Male sexual response

The penis and the urethra are essential to the transport of sperm into the vagina and the cervix during intercourse. This transport is facilitated by penile erection in response to sexual stimulation during the excitement phase. Erection results from the filling of the large venous sinuses within the erectile tissue of the penis. In the flaccid state the sinuses hold only a small amount of blood, but during the erection stage they are congested with blood. Because the penis is richly endowed with sympathetic, parasympathetic and pudendal nerve endings, it is readily stimulated to erection. The loose skin of the penis becomes taut as a result of the venous congestion. This erectile tautness allows for easy insertion into the vagina.

Gerontological considerations: the effects of ageing on the reproductive system and sexual response

With advancing age, changes occur in the male and female reproductive systems. In women many of these changes are related to the altered oestrogen production that is associated with menopause. A reduction in circulating oestrogen along with an increase in androgens in postmenopausal women is associated with breast and genital atrophy, reduction in bone mass and increased rate of atherosclerosis. Vaginal dryness may occur, which can lead to urogenital atrophy and changes in the quantity and composition of vaginal secretions.7 A gradual testosterone decline in elderly men also occurs.8 Manifestations of hormonal decline in men can be physical, psychological or sexual. Some of the changes include an increase in prostate size, decreased testosterone level, decreased sperm production, decreased muscle tone of the scrotum and a decrease in the size and firmness of the testicles. Erectile dysfunction and sexual dysfunction occur in some men as a result of these changes. Age-related changes in the reproductive systems and differences in assessment findings are presented in Table 50-3.

Gradual changes resulting from advancing age occur in the sexual responses of men and women (see Table 50-4). These changes occur at different rates and to varying degrees. The cumulative effects of these changes, as well as negative social attitude towards sexuality in older adults, can affect the sexual practices of people in this age group. Nurses have an important role in providing accurate and unbiased information about sexuality and age, and should emphasise that sexual activity in older adults is normal. Counselling may be necessary to help older patients accommodate to the physiological changes of ageing.

As the man reaches the plateau phase, the erection is maintained and a small increase in diameter occurs as a result of a slight increase in vasocongestion. There is also an increase in testicle size. Sometimes a change in colour occurs in the glans penis, which becomes more reddish-purple.

The subsequent contraction of the penile and urethral musculature during the orgasmic phase propels the sperm outwards through the meatus. In this process, termed ejaculation, sperm are released into the ductus deferens during contractions. Sperm advance through the urethra, where fluids from the prostate and seminal vesicles are added to the ejaculate. The sperm continue their path through the urethra, receiving a small amount of fluid from the Cowper’s glands, and are finally ejaculated through the urinary meatus. Orgasm is characterised by the rapid release of the vasocongestion and muscular tension (myotonia) that have developed. The rapid release of muscular tension (through rhythmic contractions) occurs primarily in the penis, prostate gland and seminal vesicles. After ejaculation, the man enters the resolution phase. During this phase the penis undergoes involution, gradually returning to its unstimulated, flaccid state.

Female sexual response

The changes that occur in a woman during sexual excitation are similar to those in a man. In response to stimulation, the clitoris becomes congested and vaginal lubrication increases from secretions from the cervix, Bartholin’s glands and vaginal walls. This initial response is the excitation phase.

As excitation is maintained in the plateau phase, the vagina expands and the uterus is elevated. In the orgasmic phase, contractions occur in the uterus from the fundus to the lower uterine segment. There is a slight relaxation of the cervical os, which helps the entrance of the sperm, and rhythmic contractions of the vagina. Muscular tension is rapidly released through rhythmic contractions in the clitoris, the vagina and the uterus. This phase is followed by a resolution phase in which these organs return to their pre-excitation state. However, women do not have to go through the resolution (refractory) recovery state before they can be orgasmic again. They can be multiorgasmic without resolution between orgasms.

Assessment of male and female reproductive systems

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Important health information

In addition to general health information, the nurse should elicit information specifically relating to the reproductive system. Reproduction and sexual issues are often considered extremely personal and private. It is essential to develop trust with the patient in order to elicit such information. A professional demeanour is important when taking a reproductive or sexual history. Be sensitive, ask gender-neutral questions and maintain an awareness of the patient’s culture and beliefs. It helps to begin with the least sensitive information (e.g. menstrual history) before asking questions about more sensitive issues such as sexual practices or STIs.

Past health history

The past health history should include information about major illnesses, hospitalisations, immunisations and surgeries. The nurse should inquire about any infections involving the reproductive system, including STIs, and take a complete obstetric and gynaecological history from the female patient.

Common paediatric illnesses that affect reproductive function are mumps and rubella. The occurrence of mumps in young men has been associated with an increase in sterility. Bilateral testicular atrophy may occur secondary to mumps-related orchitis. In the health history male patients should be asked if they have had mumps, been immunised with the mumps vaccine or have any indications of sterility.

Rubella is of primary concern to women of childbearing age. If rubella occurs during the first 3 months of pregnancy, the possibility of congenital anomalies is increased. For this reason, nurses should encourage immunisation for all women of childbearing age who have not been immunised for rubella or have not already had the disease. However, women should not be immunised if they are already pregnant.9 Women should be advised not conceive for at least 3 months after the immunisation. Rubella immunity can be determined by antibody titres.

The patient should be questioned about their current health status and the presence of any acute or chronic health problems. Problems in other body systems are often related to problems with the reproductive system. Questions relating to possible endocrine disorders—particularly diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism—must be asked because these disorders directly interfere with women’s menstrual cycles and with sexual performance. Men who have diabetes mellitus may experience erectile dysfunction and retrograde ejaculation. In women with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, pregnancy may constitute significant risks to health. Many other chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory disorders, anaemia, cancer, and kidney and urinary tract disorders may affect the reproductive system and sexual functioning.

The nurse should determine whether a history of stroke is present. In men, strokes may cause physiological or psychological erectile dysfunction. Men who have suffered a myocardial infarction (MI) may experience erectile dysfunction because of the fear of precipitating another MI resulting from sexual activity. This same concern is shared by the woman both as a partner of someone who has had an MI and as the person recovering from an MI. Although most patients have concerns about sexual activity following an MI, many are not comfortable expressing these concerns to the nurse. Be sensitive to this concern. In women, a history of cardiovascular disease (e.g. hypertension, thrombophlebitis, angina) causes a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality with pregnancy or oral contraceptive use.

Medications

All prescription and over-the-counter medications that the patient is taking should be documented, including the reason for the medication, the dosage and the length of time that the medication has been taken. All drugs taken by female patients should be evaluated for possible teratogenic effects in women of childbearing age. Patients should also be asked about the use of herbal products and dietary supplements.

Particularly relevant in the assessment of the reproductive system is the use of diuretics (sometimes prescribed for premenstrual oedema), psychotropic agents (which may interfere with sexual performance) and antihypertensives (some of which may cause erectile dysfunction). Thus patients who use drugs such as amlodipine, lisinopril, propranolol and clonidine must be closely assessed for these problems.10 Also note the use of drugs such as alcohol, marijuana, barbiturates, amphetamines or phencyclidine hydrochloride (PCP; also called ‘angel dust’), which can have serious behavioural or physiological effects on the functioning of the reproductive system.

In women, record the use of oral contraceptives or other hormones. The long-term use of both oestrogen and progesterone in hormone replacement therapy (HRT) appears to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke and breast cancer in postmenopausal women.11 The short-term use of HRT appears to be appropriate for women experiencing moderate-to-severe menopausal symptoms. (HRT is discussed in Ch 53.)

A history of cholecystitis and hepatitis is important information because these conditions may be contraindications for the use of oral contraceptives: cholecystitis is often aggravated by oral contraceptives, and chronic active inflammation of the liver generally precludes the use of oestrogen products because they are metabolised by the liver. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may be a contraindication to oral contraceptive use because progesterone thickens respiratory secretions.

Surgery or other treatment

Any surgical procedures should be noted in the health history. Surgical procedures involving the reproductive system are listed in Table 50-5. Therapeutic or spontaneous abortions should also be documented.

Functional health patterns

The key questions to ask a patient with a reproductive problem are presented in Table 50-6.

• How would you describe your overall health?

• Women: Explain how you examine your breasts. Have you had a pap smear test or mammogram recently? If so, what were the results and dates of these tests?

• Men: Explain how you examine your testes. Have you had a prostate examination recently? If so, what were the results and date of this examination?

• Describe the health of your family members. Any history of breast, uterine, ovarian or prostate cancer?

• Do you use tobacco products, alcohol or drugs?*

• Describe what you usually eat and drink.

• Have you experienced any changes in weight?*

• How do you feel about your current weight?

• Do you take any nutritional supplements such as calcium or vitamins?*

• Do you have any dietary restrictions?*

• Do you experience problems with urination (e.g. pain, burning, dribbling, incontinence, frequency)?*

• Have you had bladder infections? If so, when? How often?

• Do you experience problems with bowel movements?* Do you use laxatives?*

• What activities do you typically do each day?

• How many hours do you typically sleep each night?

• Do you feel rested after sleep?

• Do you experience any problems associated with sleeping?*

• Are you able to read and write?

• Do you experience problems with dizziness?*

• Do you experience pain? If yes, where?

• Do you experience pain during sexual activity or intercourse?*

• How would you describe yourself?

• Have there been any recent changes that have made you feel differently about yourself?*

• Are you experiencing any problems that are affecting your sexuality?*

• Describe your living arrangements. Who do you live with?

• Do you have a significant other? If yes, is this relationship satisfying?

• Are you experiencing any role-related problems in your family?* at work?*

• Are you sexually active? If so, how many partners do you have?

• What kind of sex do you engage in (e.g. oral, vaginal, rectal)?

• How do you protect yourself against sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancy?

• Are you satisfied with your present means of sexual expression? If no, explain.

• Have you experienced any recent changes in your sexual practices?*

• Women: Date of last menstruation, description of menstrual flow, problems with menstruation, age of menarche, age of menopause.

• Women: pregnancy history—number of times pregnant, number of living children, number of miscarriages/abortions.

• Have there been any major changes in your life within the last couple of years?*

Health perception–health management pattern

Two of the primary focuses of this health pattern are the patient’s perception of their own health and measures that the patient takes to maintain health. Specifically, it is important to ask about self-examination practices and screenings. Mammography according to age-specific guidelines (see Ch 51), Pap smear tests and breast self-examinations (BSEs), which are encouraged, are integral to a woman’s health. Testicular self-examination (TSE) should be practised by all men, starting in adolescence (see Box 54-3). Regular prostate examination should be encouraged as well. The Australian Cancer Council does not recommend use of the prostate specific antigen (PSA) test as a population-based screening tool for men who have no symptoms of prostate enlargement. Rather, it recommends that men who are at greater risk of prostate cancer should discuss monitoring options with their doctor.12 However, men over the age of 50 should have a regular digital rectal examination (DRE) of the prostate. Family history is also a component of this health pattern. The nurse should inquire about a history of cancer, particularly cancer of the reproductive organs. Having a first-degree relative who has had cancer of the breast, ovaries, uterus or prostate significantly increases the risk of cancer for the patient. Determination of a familial tendency for diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hypertension, stroke, angina, myocardial infarction, endocrine disorders or anaemia is also important.

Assessment of the reproductive system is incomplete without knowledge of the patient’s lifestyle choices. Determine whether a woman uses cigarettes, alcohol, caffeine or other drugs because these substances can be detrimental to both mother and fetus. Cigarette smoking may delay conception and can increase the risk of morbidity in women using oral contraceptives. Early menopause is also associated with smoking in women. These substances may adversely affect the sperm count in men and cause erectile dysfunction or decreased libido.

Also document whether the patient is allergic to sulfonamides, penicillin, rubber or latex. Sulfonamides and penicillin are used frequently in the treatment of reproductive and genitourinary problems such as vaginitis and gonorrhoea. Rubber and latex are commonly used in diaphragms and condoms. An allergy to these substances precludes their use as contraceptive methods.

Nutritional-metabolic pattern

Anaemia is a common problem in women in their reproductive years, particularly during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The adequacy of the patient’s diet should be evaluated with this condition in mind. Take a thorough nutritional and psychological history to assess for the presence of an eating disorder. Anorexia can cause amenorrhoea and subsequent problems, such as osteoporosis, that are related to menopause. From early adolescence, nurses should counsel women regarding adequate calcium and vitamin D intake to prevent osteoporosis. Estimate the patient’s daily calcium intake to determine whether there is a need for supplementation. Evaluate folic acid intake for women in their reproductive years because a deficiency can result in spina bifida and other neural tube defects in the fetus.13

Elimination pattern

Many gynaecological problems can result in genitourinary problems. Stress and urge incontinence are common in older women because of relaxation of the pelvic musculature caused by multiple births or advancing age. Vaginal infections predispose patients to chronic or recurrent urinary tract infections. Metastasis of malignant tumours of the reproductive system to the genitourinary system is possible because of their proximity. Benign prostatic hyperplasia is a common problem of older men. It can alter normal urination, causing retention and difficulty in initiating the urinary stream.

Activity-exercise pattern

The amount, type and intensity of activity and exercise should be recorded. Lack of stress on bones secondary to lack of exercise is an important factor in the development of osteoporosis. Weight-bearing exercise decreases the risk of osteoporosis in women. Women who engage in excessive exercise may experience amenorrhoea. This may result from decreased oestrogen related to a low percentage of body fat because oestrogen is stored in fat cells. Anaemia can result in fatigue and activity intolerance and can interfere with satisfactory performance of the activities of daily living.

Sleep-rest pattern

Sleep patterns may be affected during the postpartum period and also while raising young children. The hot flushes and sweating often present during perimenopause can cause serious sleep interruption when the woman awakens in a drenching sweat. The need to change her night clothes and bedding further disrupts her sleep. Insomnia is also a common complaint of perimenopausal women, and daytime fatigue often results from such sleep disruptions. In men, sleep disturbances may be caused by frequent urination at night associated with prostate enlargement or hormonal therapy for prostate cancer.

Cognitive-perceptual pattern

Pelvic pain is associated with various gynaecological disorders such as pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian cysts and endometriosis. Dyspareunia (painful intercourse) can be particularly problematic for a woman. The pain associated with intercourse can make her reluctant to participate in sexual activity and strain her relationship with her sexual partner. The woman should be referred to her healthcare provider if dyspareunia is present.

Self-perception–self-concept pattern

The reproductive changes of ageing such as pendulous breasts and vaginal dryness in women and decreased size of the penis in men may lead to emotional distress. The subtle changes associated with sexuality and advancing age may alter the patient’s self-concept.

Role-relationship pattern

The nurse should obtain information regarding the family structure and occupations. Determining the patient’s role in the family is a starting point in determining family dynamics. The patient should also be questioned regarding recent changes in work-related relationships or family conflict. Roles and relationships are affected by changes within the family. The addition of a new baby in the family may change family dynamics. Role-relationship patterns change as children begin their careers and move away from home. Another change occurs when people retire.

Sexuality-reproductive pattern

The extent and depth of the interview about a patient’s sexuality depend primarily on the expertise of the interviewer and on the needs and willingness of the patient. Before taking a sexual history, nurses should assess their own comfort with their sexuality, because any discomfort in questioning becomes obvious to the patient. Interviews must be carried out in an environment that provides reassurance, confidentiality and a non-judgemental attitude.14 It helps to begin with the least sensitive areas of questioning and then move to more sensitive areas.

For women, it is important to obtain a menstrual and an obstetric history. The menstrual history includes the first day of the last menstrual period, a description of menstrual flow, the age of menarche and, if applicable, the age at menopause. Menstrual history data are used in the detection of pregnancy, infertility and numerous other gynaecological concerns. The patient should be asked to explicitly describe any change in the usual menstrual pattern to determine whether the change is transient and unimportant or connected with a more serious gynaecological problem. Metrorrhagia (spotting or bleeding between menstruations), menorrhagia (excessive menstrual bleeding), amenorrhoea (lack of menstruation) and postcoital bleeding are examples of such problems. Changes in menstrual patterns associated with the use of contraceptive pills, intrauterine devices (IUDs), birth control patches, vaginal rings or medroxyprogesterone injections should also be identified. Contraceptive pills usually decrease the amount and duration of flow, whereas some IUDs may cause an increase in the amount and duration. Some IUDs also increase the severity of dysmenorrhoea. However, newer IUDs contain progestin and may be therapeutic.

The obstetric history includes the number of pregnancies, full-term births, preterm births and live births. It should also include information about any ectopic pregnancies or abortions, either spontaneous or therapeutic, as well as any problems that occurred with pregnancy or in the perinatal period.

The sexual history includes information regarding sexual activity, beliefs and practices. It may be necessary to explore sexual preference (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual), the frequency and type of sexual activity (penile–vaginal, penile–rectal, recipient rectal, oral), and the number of partners and protective measures against STIs and pregnancy. The patient’s knowledge of safe sexual practices should be determined, as a history of multiple sex partners and unprotected sex increases the risk of contracting an STI. For a woman, this can increase the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, which can compromise her ability to become pregnant.

Box 50-1 outlines specific questions for the sexual history. Only a skilled interviewer should approach some of these questions, and then only with discretion and sensitivity to cultural differences.

BOX 50-1 Sexual history format

• Are you currently in a relationship that involves sexual intercourse? If yes, do you have one or multiple partners?

• How frequently do you engage in sexual activities? Are you and your partner(s) satisfied with the sexual relationship?

• How many sexual partners have you had in the past 6 months?

• Do you prefer relationships with men or women, or both? (Inquire if the patient is in a significant relationship.)

• Has your sex life changed during the past year? If yes, how?

• Have you ever had a sexually transmitted disease? If yes, what?

• What are you doing to protect yourself from sexually transmitted diseases? If protection is used, what type? Do you use protection every time you have intercourse?

• Are you currently using any birth control measures? If yes, what type? How long have you been using this product? How effective do you feel this has been?

• Have you ever been in a relationship with anyone who hurt you? Have you ever been forced into sexual acts as a child or an adult?

• How often have you experienced erectile dysfunction (male) or difficulty with vaginal lubrication (female) or pain with intercourse?

Source: Adapted from Wilson SF, Giddens JF. Health assessment for nursing practice. 4th edn. St Louis: Mosby; 2009.

Both men and women should be asked about their general satisfaction with sexuality. The patient’s satisfaction with the opportunities for sexual gratification is important information that should be elicited. The patient should be questioned about sexual beliefs and practices and whether orgasm is achieved. Any unexplained change in sexual practices or performance should be explored. Problems of the reproductive system can cause physiological or psychological problems that can lead to painful intercourse, erectile dysfunction, sexual dysfunction or infertility. Both the cause and the effect of such problems should be determined.

Coping–stress tolerance pattern

The stress related to situations such as pregnancy and menopause increase dependence on support systems. It is important to determine who the support people are in the patient’s life. The diagnosis of an STD can cause stress for the patient and their partner, and the nurse should help them to explore ways to manage this stress.

Value-belief pattern

Sexual and reproductive functioning is closely related to cultural, religious, moral and ethical values. Nurses should be aware of their own beliefs in these areas and recognise and sensitively react to the patient’s personal beliefs associated with reproductive and sexuality issues.

OBJECTIVE DATA

The nurse should always ask for and gain the patient’s consent prior to touching the patient for any form of physical examination. This is particularly important when examining the genitalia.

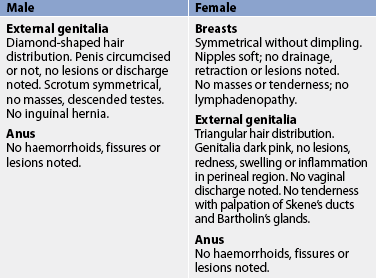

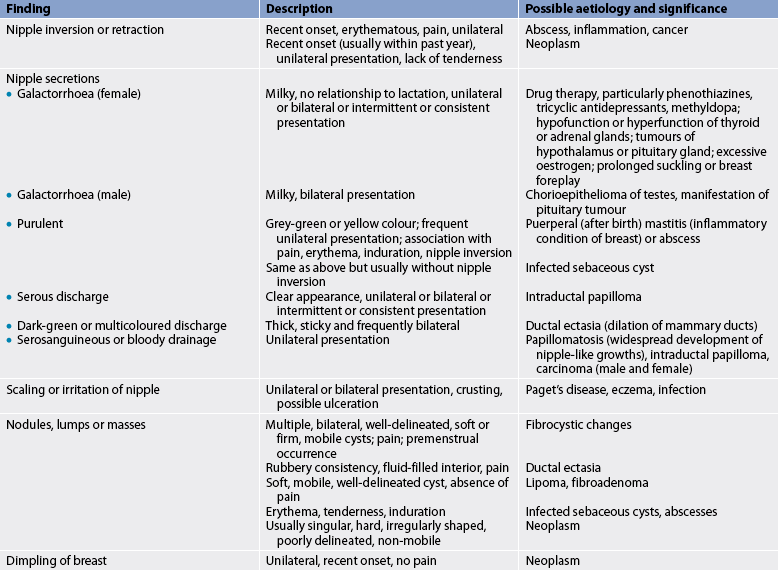

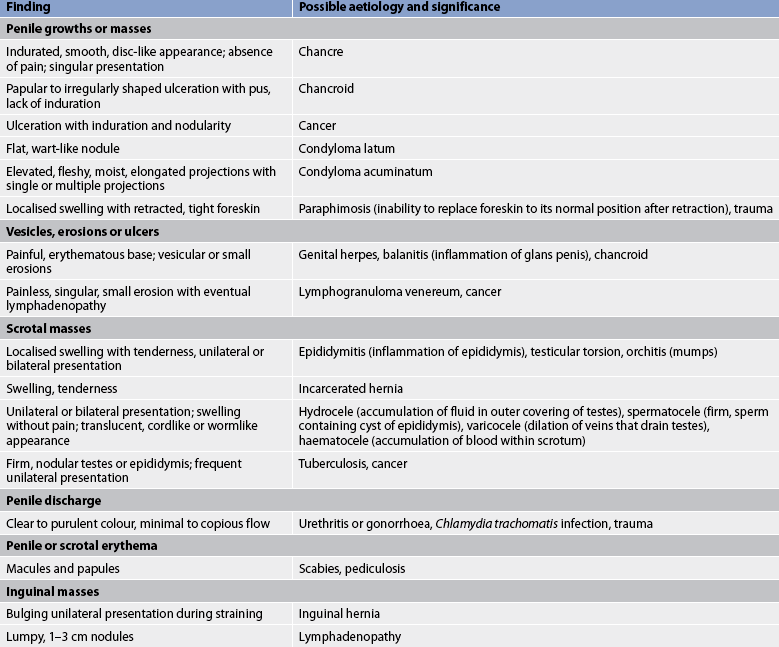

Table 50-7 provides an example of a recording format for the physical assessment findings for the male and female reproductive systems, and Tables 50-8 to 50-10 summarise common assessment abnormalities of the breasts, female reproductive system and male reproductive system, respectively. The Clinical practice box (p 1446) can be used to evaluate the status of previously identified reproductive problems and to monitor for signs of new problems.

TABLE 50-9 Female reproductive system

COMMON ASSESSMENT ABNORMALITIES

PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Physical examination: male

The examination of the male external genitalia includes inspection and palpation. An examination may be performed with the patient lying or standing. The standing position is generally preferred. The nurse should be seated in front of the standing patient. Gloves should be used during examination of the male genitalia.

• Pubis. The distribution and general characteristics of the pubic hair and skin should be observed. Normally, the hair is in a diamond-shaped pattern and coarser than scalp hair. The absence of hair is not a normal finding. The skin is also evaluated.

• Penis. The size and skin texture of the penis and any lesions, scars or swelling should be noted. It is also important to note the location of the urethral meatus, as well as the presence or absence of a foreskin. If present, the foreskin should be retracted to note cleanliness and replaced over the glans after observation. The glans is compressed to note any discharge and its amount, colour and odour if present. Palpate the penile shaft for tenderness or masses and observe the ventral and dorsal aspects.

• Scrotum and testes. This part of the examination is usually not performed by a non-specialised nurse. The nurse with advanced skills would start by performing a complete skin examination by lifting each testis to inspect all sides of the scrotal sac. Palpation of the scrotum is done to note changes in consistency or the presence of masses. It is important to note whether the testes are descended. The left testis usually hangs lower than the right. An undescended testis is a major risk factor for testicular cancer, as well as a potential cause of male infertility.

• Inguinal region and spermatic cord. This part of the examination is usually not performed by a non-specialised nurse. The nurse with advanced skills would first inspect the skin overlying the inguinal regions for rashes or lesions. The patient should be asked to bear down and cough. While he is straining, the inguinal area should be inspected for the presence of a bulge. No bulging should be seen. Next, the right and left inguinal rings should be palpated using the index finger or middle finger. The finger should be inserted into the lower aspect of the scrotum and should follow the spermatic cord upwards through the triangular slit-like opening of the inguinal ring. At this point, the patient should be asked to bear down and cough. Determine whether the strain produces a bulging of the intestines through the ring, indicating the presence of a hernia, a condition that requires follow-up. The inguinal lymph nodes should also be palpated. Enlargement of the lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) could suggest a pelvic organ infection or malignancy.

• Anus and prostate. The anal sphincter and perineal regions should be inspected for lesions, masses and haemorrhoids. A DRE is required for all men who have symptoms of prostate trouble, such as difficulty in initiating urination and the urge to void frequently. This examination should be performed annually by their general practitioner for all men over 50 years of age.

Physical examination: female

Physical examination of the female often begins with inspection and palpation of the breasts and then proceeds to the abdomen and genitalia. Examination of the abdomen provides an opportunity to detect pain or any masses that may involve the genitourinary system. Abdominal examination is discussed in Chapter 38. Gloves should be used during examination of the female genitalia

• Breasts. The breasts are first examined by visual inspection. With the patient seated, the breasts are observed for symmetry, size, shape, skin colour, vascular patterns, dimpling and the presence of unusual lesions. Then the patient is asked to put her arms at her sides, arms overhead, lean forward and press hands on hips. Observe for any abnormalities during these manoeuvres. The axillae and the clavicular areas are then palpated for enlarged lymph nodes.

• After the patient assumes a supine position, place a pillow under her back on the side to be examined. Ask her to put her arm above and behind her head. These manoeuvres flatten breast tissue and make palpation easier. The breast should be palpated in a systematic fashion, preferably using a vertical line, with the distal finger pads. The axillary tail of Spence should be included in the examination because this area and the upper outer quadrant are the areas where most breast malignancies develop. Finally, the area around the areolae should be palpated for masses. The nipple should be compressed to determine the presence of discharge or any masses, and the colour, consistency and odour of any discharge should be documented (see Table 50-2).

• External genitalia. The mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, posterior fourchette, perineum and anal region should be inspected for characteristics of skin, hair distribution and contour. Any lesions, inflammation, swelling and discharge should be noted. The labia need to be separated to fully inspect the clitoris, urethral meatus and vaginal orifice.

• Internal pelvic examination. This part of the examination is performed only by nurses who have had special training, for example women’s health nurses. During the speculum examination, the nurse observes the walls of the vagina and the cervix for inflammation, discharge, polyps and suspicious growths. During this examination, it is possible to obtain a Pap smear test and collect cells for culture and microscopic examination. After the speculum examination, a bimanual examination is performed to allow assessment of the size, shape and consistency of the uterus, ovaries and tubes. The tubes are not normally palpable. Parts of the pelvic examination are not included in this text as they are considered advanced skills and are not usually within the scope of the generalist nurse.

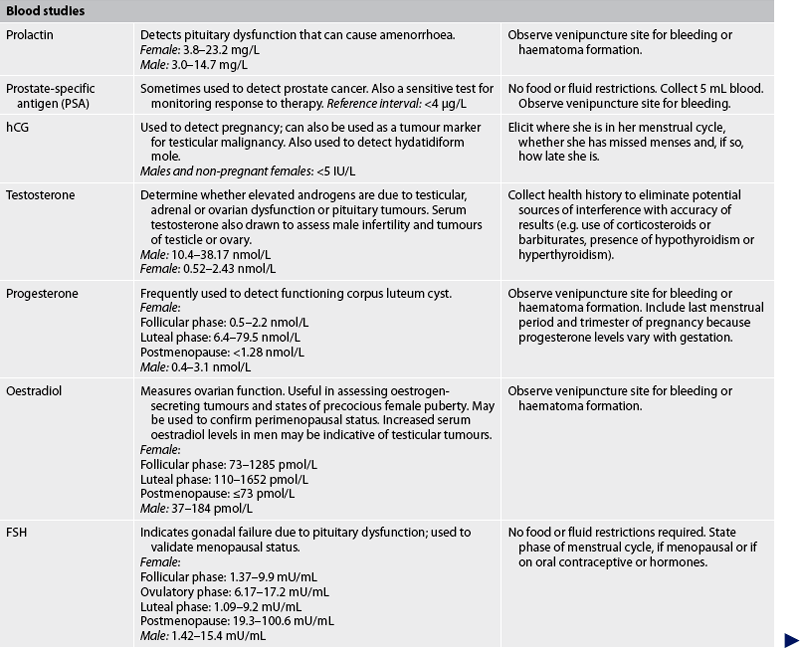

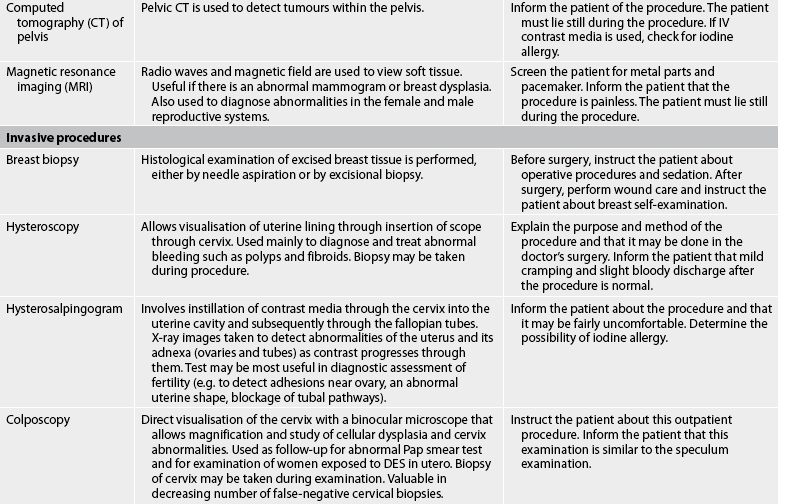

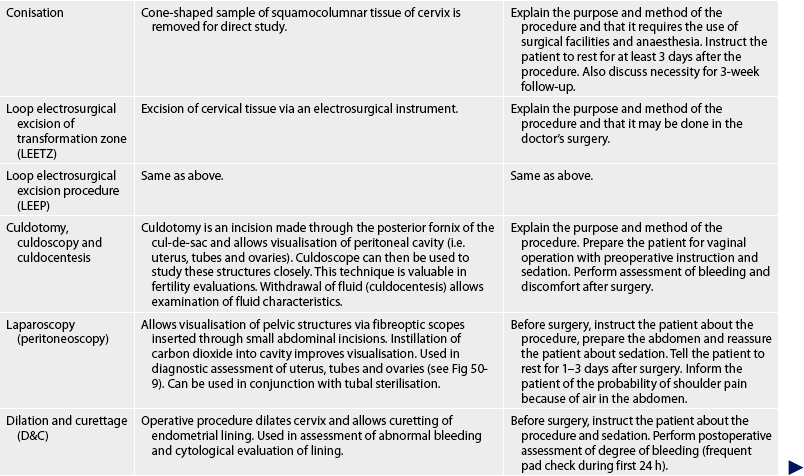

Diagnostic studies of reproductive systems

Numerous diagnostic studies are available to assess the reproductive systems. Table 50-11 summarises the most commonly used diagnostic studies in the assessment of the reproductive systems, and select studies are described in more detail below.

TABLE 50-11 Male and female reproductive systems

DES, diethylstilboestrol; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; IUD, intrauterine device.

URINE STUDIES

Pregnancy testing

The occurrence of pregnancy is generally validated by measuring hCG in the urine. A solution containing monoclonal antibodies specific for hCG is mixed with a small amount of urine. The presence of hCG causes a change in colour of the tested urine. Home pregnancy test kits use the same assay principle: positive results are based on the presence of hCG in the urine. Some tests can detect pregnancy as early as the first day following a missed menstrual period. These tests are 98% accurate if the test is performed exactly per the instructions. A second test is recommended within a week if the first test is negative (assuming menses has not yet occurred).15

Hormone studies

Although oestrogen studies are performed on urine, the results are often inaccurate because of variable oestrogen levels during the normal cycle and the difficulty in estimating the day of the cycle in women with irregular menses. Adrenal androgens are precursors of oestrogens and can be measured in the urine of both men and women. FSH can be measured in a 24-hour urine specimen. Increased and decreased FSH levels can indicate gonadal failure due to pituitary dysfunction. For more information on hormone studies, see Chapter 47.

BLOOD STUDIES

Hormone studies

Serum assays for hCG can detect pregnancy before a woman misses her menstrual period.15 The prolactin assay is used primarily in the assessment of a patient with amenorrhoea. High levels of prolactin are normally associated with low levels of oestrogen, such as those that occur during lactation. However, the same finding can occur with pituitary adenomas, especially with otherwise unexplained galactorrhoea (excessive secretion of breast milk). Serum progesterone and oestradiol are sometimes measured in assessment of ovarian function, particularly for amenorrhoea. In addition, hormonal blood studies are essential components of a thorough fertility work-up.

Tumour markers

Biological tumour markers are substances associated with malignant disease. Measurement of these markers is useful in monitoring therapy (marker levels rise as disease progresses and fall with disease regression) because marker levels may rise months before new disease or metastasis is evident. α-fetoprotein (AFP), hCG and CA-125 are sometimes used as tumour markers for reproductive system malignancies. A specific tumour antigen such as PSA is another type of tumour marker frequently used for prostate cancer.

Serology tests for syphilis

The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test and the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) detect the presence of antibodies in the serum of patients infected with syphilis. These tests are inexpensive and reliable but have high levels of false-positive results. The fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-Abs) test is highly reliable and should be used after a positive VDRL or RPR, even one that is weakly positive or questionable.

CULTURES AND SMEARS

Cultures and smears are most frequently employed in the diagnosis of STIs. Specimens for cultures and smears are most commonly taken from the vagina, endocervix and rectum for females and the urethra and rectum for males. For a culture, the specimen is placed on a special culture medium; a smear involves rubbing the specimen on a slide for direct examination. Gram stain smears have been shown to be effective in the diagnosis of Chlamydia infection. A nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) can screen for both gonorrhoea and Chlamydia from a wide variety of samples, including vaginal, endocervical, urinary and urethral specimens. Dark-field microscopy involves the direct examination of a specimen obtained from a syphilitic chancre for the diagnosis of syphilis.

CYTOLOGICAL STUDIES

Cytology involves the study of cells under microscopic examination. The Pap smear test is a screening test to detect abnormal cells obtained from the cervix or vagina. It is performed by obtaining cells from the cervical canal, preferably the endocervix, as well as from the vagina. The cells are placed in a fixative for examination by a cytologist for cellular abnormalities. Screening guidelines for the Pap smear test are discussed in Chapter 53.

Cytological study is also indicated for nipple discharge. Cytological examination of discharge can detect the presence of malignant cells as opposed to a discharge associated with infection.

RADIOLOGICAL STUDIES

Mammography

Mammography, one of the most frequently used diagnostic tools to assess the reproductive system, is used to detect breast masses. Mammography can detect breast masses before they are palpable. Mammography and screening guidelines for mammography are discussed in Chapter 51.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound has many applications for diagnostic studies. Pelvic ultrasound is used to obtain images of the pelvic organs (see Fig 50-9). These types of ultrasound are also used to detect pregnancy in the uterus, ectopic pregnancy, ovarian cysts and other pelvic masses. Breast ultrasound is useful in the detection of fluid-filled masses. In men, ultrasound is used to detect testicular masses and testicular torsion. Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) is useful for diagnosing prostate tumours.

1. A normal reproductive function that may be altered in a patient who undergoes a prostatectomy is:

2. Oestrogen production by the mature ovarian follicle causes:

3. Male orgasm is the result of:

4. An age-related finding noted by the nurse during assessment of the older woman’s reproductive system is:

5. Significant information about a patient’s past health history related to the reproductive system should include:

6. The examination technique used to evaluate the prostate involves:

7. An abnormal finding noted during physical assessment of the male reproductive system is:

8. The screening criteria for assessing prostate cancer include a:

1 Thibodeau GA, Patton KT. Structure and function of the body, 13th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2008.

2 Katz V. Comprehensive gynecology, 5th edn. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2007.

3 McCance KL, Huether SE. Pathophysiology: the biological basis for disease in adults and children, 6th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2010.

4 Styne D, Grumbach M. Puberty. Ontogeny, endocrinology, physiology and disorders. In Kronberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, et al, eds.: Williams textbook of endocrinology, 11th edn., Philadelphia: Mosby, 2008.

5 Farage M, Neill S, MacLean A. Physiological changes associated with the menstrual cycle: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64:58.

6 Masters WH, Johnson E. Human sexual response. Boston: Little Brown, 1966. Seminal text

7 Weismiller DG. Menopause. Prim Care. 2009;36:199.

8 Gooren L. Recent perspectives on the age-related decline of testosterone. J Men’s Health. 2008;5:87.

9 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Care before and during pregnancy: prenatal care. Available at www.nichd.nih.gov/womenshealth. accessed 15 October 2010.

10 Saunders. 2010 drug reference. St Louis: Saunders, 2010.

11 National Institutes of Health/Women’s Health Initiative. Facts about postmenopausal hormonal therapy. Available at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/women. accessed 15 October 2010.

12 Australian Cancer Council. Position statement: prostate cancer screening. Available at www.cancer.org.au/File/PolicyPublications/Position_statements/PS_prostate_cancer_screening_updated_June_2010.pdf. accessed 15 October 2010.

13 Blencowe H, Cousens C, Modell B, Lawn J. Folic acid to reduce neonatal mortality from neural tube disorders. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:i110–i121.

14 Wallace M. Assessment of sexual health in older adults. Am J Nurs. 2008;108:52.

15 Chernecky C, Berger B. Laboratory tests and diagnostic procedures, 5th edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2008.