Chapter 47 NURSING ASSESSMENT: endocrine system

1. Identify the common characteristics and functions of hormones.

2. Name the locations of the endocrine glands.

3. Describe the functions of hormones secreted by the pituitary, thyroid, parathyroid and adrenal glands and the pancreas.

4. Describe the locations and roles of hormone receptors.

5. Identify the significant subjective and objective assessment data related to the endocrine system that should be obtained from a patient.

6. Apply appropriate technique used in the physical assessment of the thyroid gland.

7. Describe age-related changes in the endocrine system and differences in assessment findings.

8. Differentiate between normal and common abnormal findings in the assessment of the endocrine system.

9. Describe the purpose, significance of results and nursing responsibilities related to diagnostic studies of the endocrine system.

The endocrine system and the nervous system are two of the primary communicating and coordinating systems in the body. The nervous system communicates through nerve impulses; the endocrine system communicates through chemical substances known as hormones, and it plays a role in reproduction, growth and development, and regulation of energy. The endocrine system is composed of glands or glandular tissues that produce, store and secrete hormones, which travel through the blood to specific target cells throughout the body.

The endocrine glands include the hypothalamus, pituitary, thyroid, parathyroids, adrenals, pancreas, ovaries, testes, pineal and thymus (see Fig 47-1). The thymus gland is important in the function of the immune system and is discussed in Chapter 13. The pineal gland, which secretes melatonin, is involved in stimulating gonadal function.1 In addition to the endocrine glands, other body organs secrete hormones. For example, the kidneys secrete erythropoietin, the heart secretes atrial natriuretic peptide and the gastrointestinal tract secretes numerous peptide hormones (e.g. gastrin). These hormones are discussed in their respective assessment chapters.

Figure 47-1 Location of the major endocrine glands. The parathyroid glands actually lie on the posterior surface of the thyroid.

Structures and functions of the endocrine system

GLANDS

The organs of the endocrine system are referred to as glands. Endocrine glands produce chemical substances called hormones and secrete them into blood, where they eventually affect specific target tissues. A target tissue is the body tissue or organ that the hormone has its effect on. For example, the thyroid (gland) synthesises thyroxine (the hormone), which influences all body tissues (target tissue). It is important to note that not all glands in the body belong to the endocrine system. There are two types of glands—exocrine glands and endocrine glands. Exocrine glands secrete their substances into ducts that then empty into a body cavity or onto a surface (e.g. skin). For example, salivary glands produce saliva, which is secreted through salivary ducts into the mouth. By contrast, endocrine glands do not have ducts. They secrete their substances directly into the blood.

HORMONES

Classifications and functions

A hormone is a chemical substance synthesised and secreted by a specific organ or tissue. Most hormones have common characteristics, including: (1) secretion in small amounts at variable but predictable rates; (2) circulation through the blood; and (3) binding to specific cellular receptors either in the cell membrane or within the cell.

Hormones are classified by their chemical structure as either lipid-soluble hormones or water-soluble (protein-based) hormones. Lipid-soluble hormones include steroid hormones (all hormones produced by the adrenal cortex and sex glands) and thyroid hormones. All other hormones are water soluble.2 The differences in solubility become important in understanding how hormones interact with target cells.

Hormones control a number of physiological activities. Important hormonal functions are related to reproduction, response to stress and injury, electrolyte balance, energy metabolism, growth, maturation and ageing. Hormones also play a role in nervous system function. Some hormones have a regulatory effect on nervous tissue. For example, catecholamines are hormones when they are secreted by the adrenal medulla, but act as neurotransmitters when they are secreted by nerve cells in the brain and peripheral nervous system. When adrenaline travels through the blood, it is a hormone and affects target tissues. When it travels across synaptic junctions, it acts as a neurotransmitter.

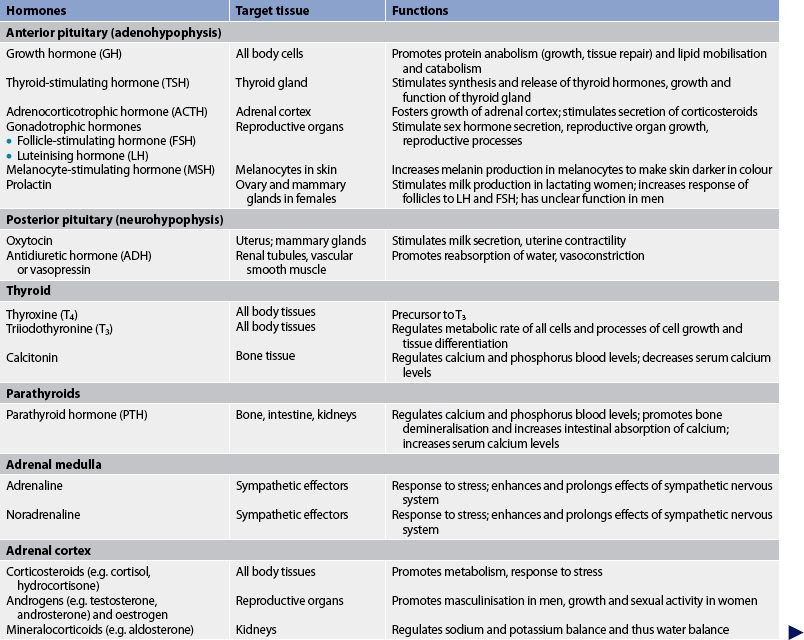

Hormones can also influence behaviour.3 For example, excess growth hormone, cortisol and parathyroid hormone can cause mood swings. Depression has been associated with adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism. Table 47-1 summarises the major hormones, the glands or tissues from which they are synthesised, target organs or tissues, and functions.

Hormone transport

Hormones are carried by the blood to other sites in the body where their actions are exerted. Some hormones (e.g. steroid and thyroid hormones) are not water soluble. These types of hormones are bound to plasma proteins for transport in the blood. Although hormones are inactive when bound to plasma proteins, they can be released when appropriate and immediately exert their action at the target tissue. Water-soluble hormones (e.g. protein hormones, catecholamines) circulate freely in the blood and are not dependent on proteins for transport.

Targets and receptors

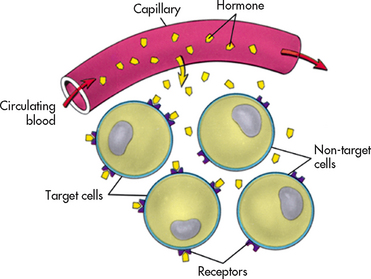

Hormones exert their effects on target tissue. The hormone recognises the target tissue through receptors (the site that interacts with the hormone) on, or within, cells of the target tissue. The specificity of hormone–target cell interaction is determined by receptors in a ‘lock-and-key’ type of mechanism. Thus, a hormone will act only on cells that have a receptor specific for that hormone (see Fig 47-2). It is important to note that there are two types of receptors: those within the cell (e.g. steroid and thyroid hormone receptors) and those on the cell membrane (e.g. protein hormone receptors). The location of the receptor sites affects the mechanism of action for the hormone.

Figure 47-2 The target cell concept. A hormone acts only on cells that have receptors specific to that hormone because the shape of the receptor determines which hormone can react with it. This is an example of the lock-and-key model of biochemical reactions.

Steroid and thyroid hormone receptors

Steroid and thyroid hormone receptors are located inside the cell. Because these hormones are lipid soluble, they pass through the target cell membrane by passive diffusion and bind to receptor sites located in the cytoplasm or nucleus of the target cell.4 Intracellular hormone–receptor complexes, such as those seen in steroid hormone action, bind to specific sites on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) to stimulate or inhibit the synthesis of messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA). When new mRNA is synthesised, it migrates to the cytoplasm, where it stimulates the synthesis of new protein. These new proteins produce specific effects in the target cell (see Fig 47-3).

Figure 47-3 A, Steroid hormones penetrate the cell membrane and interact with intracellular receptors. The hormone–receptor complex activates the cell by stimulating protein synthesis. B, Protein hormones bind to receptors located on the surface of the cell membrane. The hormone–receptor interaction stimulates the formation of cAMP, thereby activating various cell processes.

Protein hormone receptors

Protein hormone action is a two-step process. The receptor is located in the target cell membrane; thus, the hormone itself acts as a ‘first messenger’. The hormone–receptor interaction stimulates the production of a ‘second messenger’, such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). cAMP works by activating enzymes to regulate intracellular activity (see Fig 47-3).

Regulation of hormonal secretion

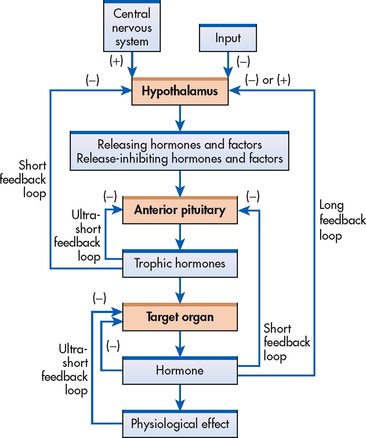

The regulation of endocrine activity is controlled by specific mechanisms of varying levels of complexity. These mechanisms stimulate or inhibit hormone synthesis and secretion and include simple feedback, complex feedback, nervous system control and physiological rhythms.

Simple feedback

The regulation of hormone levels in the blood depends on a highly specialised mechanism called feedback. Feedback is based on the blood level of a particular substance. This substance may be a hormone or other chemical compound regulated by, or responsive to, a hormone. With negative feedback, the most common type of feedback system, the gland responds by increasing or decreasing the secretion of a hormone based on feedback from various factors. Negative feedback is similar to the functioning of a thermostat in which cold air in a room activates the thermostat to release heat, and hot air turns off the thermostat to prevent more warm air from entering the room.

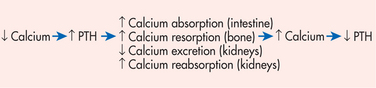

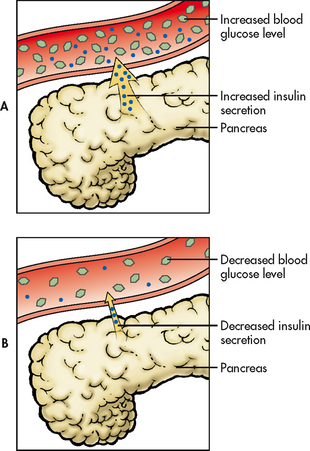

The pattern of insulin secretion is a physiological example of negative feedback between glucose and insulin. Elevated blood glucose levels stimulate the secretion of insulin from the pancreas. As blood glucose levels decrease, the stimulus for insulin secretion also decreases (see Fig 47-4). This homeostatic mechanism is considered negative feedback as it reverses the change in blood glucose level. Another example of negative feedback is the relationship between calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH). Low blood levels of calcium stimulate the parathyroid gland to release PTH, which acts on bone, the intestines and the kidneys to increase blood calcium levels. The increased blood calcium levels then inhibit further PTH release (see Fig 47-5).

Figure 47-4 The feedback mechanism between blood glucose levels and insulin. Increased blood glucose levels stimulate increased insulin secretion from the pancreas. As blood glucose levels decline, insulin secretion decreases.

Positive feedback is a second method of regulation of hormone secretion. The positive feedback mechanism increases the target organ action beyond normal. The action of oxytocin in childbirth is an example. The hormone oxytocin from the posterior pituitary stimulates and increases uterine contractions. Oxytocin release is stimulated by pressure receptors in the vagina. As the fetus enters the vagina during childbirth, the pressure receptors sense increased pressure and signal the brain to release more oxytocin. Oxytocin release leads to stronger uterine contractions. With birth, the stimulus to the pressure receptors in the vagina ends, thus leading to decreased oxytocin secretion.

Complex feedback

Complex feedback involves communication via hormones among several glands to turn on or turn off target organ hormone secretion. An example of complex feedback is regulation of thyroid hormones (see Fig 47-6). The synthesis and release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) or thyrotrophin from the anterior pituitary is stimulated by thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH), which is secreted by the hypothalamus. The thyroid hormones, triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), have an inhibitory effect on the secretion of both TRH from the hypothalamus and TSH from the anterior pituitary.

Nervous system control

In addition to chemical regulation, some endocrine glands are directly affected by the activity of the nervous system. Pain, emotion, sexual excitement and stress can stimulate the nervous system to modulate hormone secretion. Neural involvement is initiated by the central nervous system (CNS) and implemented by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). For example, stress is sensed by the CNS, and the SNS secretes catecholamines that increase heart rate and blood pressure to deal with stress more effectively.

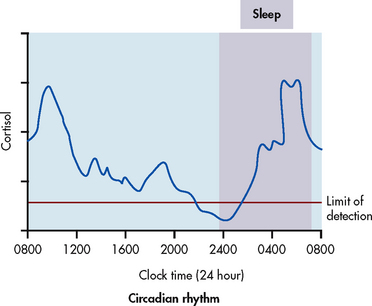

Rhythms

Another regulatory mechanism affecting many hormonal secretions involves the rhythms of secretions. These rhythms originate in brain structures. A common physiological rhythm is the circadian rhythm, in which a hormone level fluctuates predictably during a 24-hour period.5 These rhythms may be related to sleep–wake or dark–light cycles. For example, cortisol rises early in the day, declines towards evening and rises again towards the end of sleep to peak by morning (see Fig 47-7). Growth hormone (GH) and prolactin secretion peak during sleep. TSH secretion is also maximal during sleep and ebbs 3 hours after a person awakens in the morning. The menstrual cycle is an example of a body rhythm that is longer than 24 hours (ultradian). These rhythms must be considered when interpreting hormone levels on laboratory results. (See diagnostic studies section in this chapter and Ch 50.)

HYPOTHALAMUS

The relationship between the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland is one of the most important aspects of the endocrine system. Although the pituitary gland has been referred to as the ‘master gland’, most of its functions rely on an interrelationship with the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus and the pituitary gland integrate communication between the nervous and endocrine systems.

The hypothalamus is located in the most central part of the diencephalon area of the brain (see Fig 47-1). Although it is really part of the brain, the hypothalamus secretes many hormones. Two important groups of hormones from the hypothalamus are releasing hormones and inhibiting hormones.6 The function of these hormones is to either stimulate (release) or inhibit the secretion of hormones from the anterior pituitary gland (see Box 47-1).

The hypothalamus also contains neurons, which receive input from the brainstem and limbic system. These neurons influence the limbic system, brainstem and spinal cord. This creates a circuit to facilitate the coordination of the endocrine system, autonomic nervous system (ANS) and expression of complex behavioural responses, such as anger and feelings of fear and pleasure.

PITUITARY

The pituitary gland (also called the hypophysis) is very small—about the size of a pea. It is located in the sella turcica under the hypothalamus at the base of the brain above the sphenoid bone (see Fig 47-1). The pituitary is connected to the hypothalamus by the infundibular (hypophyseal) stalk. This stalk serves as a communication mechanism between the hypothalamus and the pituitary. The pituitary consists of two parts: the anterior (adenohypophysis) lobe and the posterior (neurohypophysis) lobe. Hormones secreted from each of these pituitary lobes serve very different functions.

Anterior pituitary

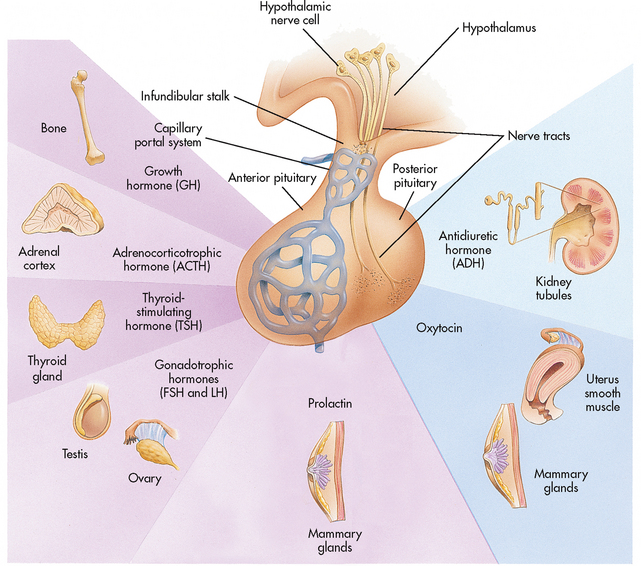

The anterior lobe accounts for 80% of the gland by weight. As mentioned previously, the anterior pituitary is regulated by the hypothalamus through releasing and inhibiting hormones. These hypothalamic hormones reach the anterior pituitary through a network of capillaries known as the hypothalamus–hypophyseal portal system. The releasing and inhibiting hormones in turn affect the secretion of six hormones from the anterior pituitary (see Fig 47-8 and Box 47-1).

Figure 47-8 The relationship between the hypothalamus, pituitary and target organs. The hypothalamus communicates with the anterior pituitary via a capillary system and with the posterior pituitary via nerve tracts. The anterior and posterior pituitary hormones are shown with their target tissues.

Trophic hormones

Several hormones secreted by the anterior pituitary are referred to as trophic hormones. These hormones control the secretion of hormones by other glands. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) stimulates the thyroid gland to secrete thyroid hormones. Adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) stimulates the adrenal cortex to secrete corticosteroids. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates secretion of oestrogen and the development of ova in the female and sperm in the male. Luteinising hormone (LH) stimulates ovulation in the female and the secretion of sex hormones in both the male and the female.

Growth hormone

Growth hormone has effects on all body tissues. GH, as its name suggests, affects the growth and development of skeletal muscles and long bones, affecting a person’s size and height. It also has numerous biological actions, including a role in protein, fat and carbohydrate metabolism.7

Posterior pituitary

The posterior pituitary is composed of nerve tissue and is essentially an extension of the hypothalamus. The communication between the hypothalamus and the posterior pituitary occurs through nerve tracts known as the median eminence. The hormones secreted by the posterior pituitary, antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and oxytocin, are actually produced in the hypothalamus. These hormones travel down the nerve tracts from the hypothalamus to the posterior pituitary and are stored until their release is triggered by the appropriate stimuli (see Fig 47-8).

Antidiuretic hormone

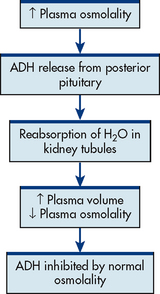

The major physiological role of ADH is regulation of fluid volume by stimulation of reabsorption of water in the renal tubules. ADH, also called vasopressin, is a potent vasoconstrictor.

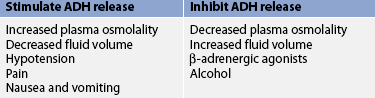

The most important stimulus to ADH secretion is plasma osmolality (a measure of the solute concentration of circulating blood; see Fig 47-9). Plasma osmolality will increase when there is a decrease in extracellular fluid or an increase in solute concentration (see Ch 16). The increased plasma osmolality activates osmoreceptors, which are extremely sensitive, specialised neurons in the hypothalamus. These activated osmoreceptors stimulate ADH release.8 Table 47-2 presents factors that affect ADH release. When ADH is released, the renal tubules reabsorb water, creating a more concentrated urine. When ADH release is inhibited, renal tubules do not reabsorb water, thus creating more dilute urine.

THYROID GLAND

The thyroid gland is located in the anterior portion of the neck in front of the trachea. It consists of two encapsulated lateral lobes connected by a narrow isthmus (see Fig 47-10). The thyroid is a highly vascular organ and is regulated by TSH from the anterior pituitary. The three hormones produced and secreted by the thyroid gland are thyroxine, triiodothyronine and calcitonin.

Thyroxine and triiodothyronine

The major function of the thyroid gland is the production, storage and release of the thyroid hormones, thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). T4 is by far the most abundant thyroid hormone, accounting for 90% of thyroid hormone produced by the thyroid gland. T3 is much more potent and has greater metabolic effects. About 20% of circulating T3 is secreted directly by the thyroid gland and the remainder is obtained by peripheral conversion of T4.9 Iodine is necessary for the synthesis of thyroid hormones. T4 and T3 affect metabolic rate, energy requirements, oxygen consumption, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, growth and development, brain functions and other nervous system activities. More than 99% of thyroid hormones are bound to plasma proteins, especially thyroxine-binding globulin, which is synthesised by the liver. Only the unbound ‘free’ hormones are biologically active.

Thyroid hormone production and release is stimulated by TSH from the anterior pituitary gland. When circulating levels of thyroid hormone are low, the hypothalamus releases TRH, which in turn causes the anterior pituitary to release TSH. High circulating thyroid hormone levels have an inhibitory effect on the secretion of both TRH from the hypothalamus and TSH from the anterior pituitary.

Calcitonin

Calcitonin is a hormone produced by C cells (parafollicular cells) of the thyroid gland in response to high circulating calcium levels. Calcitonin inhibits calcium resorption (loss of substance) from bone, increases calcium storage in bone and increases renal excretion of calcium and phosphorus, thereby lowering serum calcium levels. Despite providing a counter mechanism to the action of parathyroid hormone, calcitonin does not play a critical role in calcium balance.10

PARATHYROID GLANDS

The parathyroid glands are small, oval structures usually arranged in pairs behind each thyroid lobe (see Fig 47-10). There are usually four glands. The major cell type of the glands is epithelial, and the gland is richly supplied with blood from the inferior and superior thyroid arteries.

Parathyroid hormone

The parathyroids secrete parathyroid hormone, also called parathormone. Its major role is to regulate the blood level of calcium. PTH acts on bone and the kidneys, and indirectly on the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In bone, PTH stimulates bone resorption and inhibits bone formation, resulting in the release of calcium and phosphate into the blood. In the kidneys, PTH increases calcium reabsorption and phosphate excretion. In addition, PTH stimulates renal conversion of vitamin D to its most active form (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3). This active vitamin D then enhances intestinal absorption of calcium.

PTH is not under pituitary and hypothalamic control. The secretion of this hormone is directly regulated by a feedback system (see Fig 47-5). When the serum calcium level is low, PTH secretion increases; when the serum calcium level rises, PTH secretion falls. In addition, high levels of active vitamin D inhibit PTH and low levels of magnesium stimulate PTH secretion.

ADRENAL GLANDS

The adrenal glands are small, paired, highly vascularised glands located on the upper portion of each kidney. Each gland consists of two parts: the medulla and the cortex (see Fig 47-11). Each part has distinct functions, and the glands act independently of one another.

Adrenal medulla

The adrenal medulla is the inner part of the gland and consists of sympathetic postganglionic neurons. The medulla secretes the catecholamines: adrenaline (the major hormone [75%]), noradrenaline (25%) and dopamine. Catecholamines, usually considered neurotransmitters, are hormones when secreted by the adrenal medulla because they are released into the circulation and transported to their target organs. Catecholamines exert their effects after binding to adrenergic receptors on cells, and they have widespread effects on all body systems. Catecholamines are an essential part of the body’s response to stress.

Adrenal cortex

The adrenal cortex is the outer part of the adrenal gland. It secretes more than 50 steroid hormones, which are classified as glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids and androgens. Cholesterol is the precursor for steroid hormone synthesis. Glucocorticoids (e.g. cortisol) are named for their effects on glucose metabolism. Mineralocorticoids (e.g. aldosterone) are essential for the maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance. Adrenal androgens are produced and secreted in small but significant amounts. The term corticosteroid refers to any of the hormones synthesised by the adrenal cortex (excluding androgens).

Cortisol

Cortisol, the most abundant and potent glucocorticoid, is necessary to maintain life. One major function of cortisol is the regulation of blood glucose concentration. Cortisol increases blood glucose levels through stimulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis (conversion of amino acids to glucose) and inhibiting protein synthesis. Cortisol also decreases peripheral glucose use in the fasting state. Additionally, glucocorticoids stimulate lipolysis in adipose tissue, thereby mobilising glycerol and free fatty acids.

Another major effect of glucocorticoids is their anti-inflammatory action and supportive actions in response to stress. A marked increase in the rate of cortisol secretion by the adrenal cortex aids the body in coping more effectively with stressful situations. Cortisol decreases the inflammatory response by stabilising the membranes of cellular lysosomes and preventing increased capillary permeability. The lysosomal stabilisation reduces the release of proteolytic enzymes and thereby their destructive effects on surrounding tissue. Cortisol can also inhibit production of prostaglandins, thromboxanes and leukotrienes and alter the cell-mediated immune response. Cortisol helps maintain vascular integrity and fluid volume. It has a mineralocorticoid effect because it can bind to mineralocorticoid receptors.

Cortisol is secreted in a diurnal pattern (see Fig 47-7). The major control of cortisol is by means of a negative feedback mechanism that involves the secretion of corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus. CRH stimulates the secretion of ACTH by the anterior pituitary. Cortisol levels are also increased by surgical stress, burns, infection, fever, acute anxiety and hypoglycaemia.

Aldosterone

Aldosterone is a potent mineralocorticoid that maintains extracellular fluid volume. It acts at the renal tubule to promote renal reabsorption of sodium and excretion of potassium and hydrogen ions. Aldosterone synthesis and secretion are stimulated by angiotensin II, hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia, and inhibited by atrial natriuretic peptide and hypokalaemia.

Adrenal androgens

The third class of steroids synthesised and secreted by the adrenal cortex are the androgens. Normally, the adrenal cortex secretes small amounts of androgens. Adrenal androgens stimulate pubic and axillary hair growth and sex drive in females. In females, androgens are converted to oestrogen in the peripheral tissues. In postmenopausal women the major source of oestrogen is the peripheral conversion of adrenal androgen to oestrogen. The effects of adrenal androgen in men are negligible in comparison with those of testosterone, which is secreted by the testes.

PANCREAS

The pancreas is a long, tapered, lobular, soft gland located behind the stomach and anterior to the first and second lumbar vertebrae. The pancreas has both exocrine and endocrine functions. The hormone-secreting portion of the pancreas is referred to as the islets of Langerhans. The islets account for less than 2% of the gland and consist of four types of hormone-secreting cells: alpha, beta, delta and F cells. Alpha cells produce and secrete the hormone glucagon; beta cells produce and secrete insulin; delta cells produce and secrete somatostatin; and F (or PP) cells secrete pancreatic polypeptide.

Glucagon

Glucagon is synthesised and released from pancreatic alpha cells in response to low levels of blood glucose, protein ingestion and exercise. Glucagon increases blood glucose levels by stimulating glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis. Usually, glucagon and insulin function in a reciprocal manner to maintain normal blood glucose levels. The exception is after ingestion of a high-protein, carbohydrate-free diet, in which case both hormones are secreted. In this instance, glucagon counteracts the inhibitory effect of insulin on gluconeogenesis, and normal blood glucose levels are maintained.

Gerontological considerations: effects of ageing on the endocrine system

Normal ageing has many effects on the endocrine system (see Table 47-4). These include: (1) decreased hormone production and secretion; (2) altered hormone metabolism and biological activity; (3) decreased responsiveness of target tissues to hormones; and (4) alterations in circadian rhythms.

TABLE 47-4 Effects of ageing on the endocrine system

GERONTOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES IN ASSESSMENT

PTH, parathyroid hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; T3, triiodothyronine; T4, thyroxine.

Assessment of the effects of ageing on the endocrine system is difficult because the subtle changes of ageing often mimic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Some endocrine changes associated with ageing are obvious, whereas others are subtle. The nurse must be aware that endocrine problems may manifest differently in an older adult than in a younger person. Older adults may have multiple comorbidities and take multiple medications that alter the body’s usual response to endocrine dysfunction. Symptoms of endocrine dysfunction, such as fatigue, constipation or mental impairment, are often missed in the older adult because they are attributed solely to ageing. It is important that the nurse consider age-related endocrine changes when assessing the older adult.2

Insulin

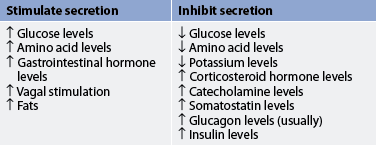

Insulin is the principal regulator of the metabolism and storage of ingested carbohydrates, fats and proteins. Insulin facilitates glucose transport across cell membranes in most tissues. However, the brain, nerves, lens of the eye, hepatocytes, erythrocytes and cells in the intestinal mucosa and kidney tubules are not dependent on insulin for glucose uptake. An increased blood glucose level is the major stimulus for insulin synthesis and secretion. Other stimuli to insulin secretion are increased amino acid levels and vagal stimulation. Insulin secretion is usually inhibited by low blood glucose levels, glucagon, somatostatin, hypokalaemia and catecholamines (see Table 47-3).

A major effect of insulin on glucose metabolism occurs in the liver, where the hormone enhances glucose incorporation into glycogen and triglycerides by altering enzymatic activity and inhibiting gluconeogenesis. Another major effect occurs in peripheral tissues, where insulin facilitates glucose transport into cells, transport of amino acids across muscle membranes and their synthesis into protein, and transport of triglycerides into adipose tissue. Thus, insulin is a storage, or anabolic, hormone.

The endocrine system is concerned with the regulation of body processes and the maintenance of internal homeostasis despite vastly changing substrates, as is seen in glucose homeostasis after food ingestion. After a meal, insulin is responsible for the storage of nutrients (anabolism). In the fasting state (during which ingested glucose is not readily available), hormones such as catecholamines, cortisol and glucagon break down stored complex fuels (catabolism) to provide simple glucose as fuel for energy.

Assessment of the endocrine system

Hormones affect every body tissue and system, causing great diversity in the signs and symptoms of endocrine dysfunction. Therefore, assessment of the endocrine system is often difficult and requires keen clinical skills to detect manifestations of disorders. Endocrine dysfunction may result from deficient or excessive hormone secretion, transport abnormalities, an inability of the target tissue to respond to a hormone or inappropriate stimulation of the target-tissue receptor.

Endocrine disorders may have specific or non-specific (vague) clinical manifestations. Specific signs and symptoms, such as the classic ‘polys’ (polyuria, polydipsia and polyphagia) in diabetes mellitus, make the assessment easier. Non-specific signs and symptoms, such as tachycardia, palpitations, fatigue or altered mood, are more problematic. Non-specific changes should alert the healthcare provider to the possibility of an endocrine disorder. The most common non-specific symptoms, fatigue and depression, are often accompanied by other manifestations, such as changes in energy level, alertness, sleep patterns, mood, affect, weight, skin, hair, personal appearance and sexual function.

SUBJECTIVE DATA

The lack of clear-cut manifestations of endocrine problems requires a conscientious and detailed health history. A careful health history will yield data to help sort out possible causes and the effect of the problem on the person’s life (see Table 47-5).

• What is your usual day like?

• Have you noticed any changes in your ability to perform your usual activities compared with last year? 5 years ago?*

• What is your weight and height?

• How much do you want to weigh?

• Have there been any changes in your appetite or weight?*

• Have you noticed any changes in the distribution of hair anywhere on your body?*

• Have you noticed any changes in the colour of your skin, particularly on your face, neck, hands or body creases?*

• Has the texture of your skin changed? For example, does it seem thicker and drier than it used to?*

• Have you noticed any difficulty swallowing or are your shirts more difficult to button up?*

• Do you feel more nervous than you used to? Do you notice your heart pounding or that you sweat when you do not think you should be sweating?

• Do you have difficulty holding things because of shakiness of your hands?*

• Do you feel that most rooms are too hot or too cold? Do you frequently have to put on a sweater or feel as though you need to open windows when others in the room seem comfortable?*

• Do you have to get up at night to urinate? If so, how many times? Do you keep water by your bed at night?

• Have you ever had a kidney stone?*

• Describe your usual bowel pattern. Have you noted any bowel changes?*

• Do you use anything, such as laxatives, to help you to move your bowels?*

• What is your usual activity pattern during a typical day?

• Do you have a planned exercise program? If yes, what is it and have you had to make any changes in this routine lately? If so, why and what kinds of changes?

• Do you experience fatigue with or without activity?*

• How many hours do you sleep at night? Do you feel rested on awakening?

• Are you ever awakened by sweating during the night?*

• Do you have nightmares?*

• Does anyone in your family complain about your snoring?*

• How is your memory? Have you noticed any changes?

• How long can you concentrate on any one thing? Has this changed lately?

• Have you experienced any blurring or double vision?*

• Have you noticed any changes in your physical appearance or size?*

• Are you concerned about your weight?*

• Do you feel you are able to do what you think you should be capable of doing? If not, why not?

• Does your health problem affect how you feel about yourself?*

• Are you married? Do you have any children? Do you think you are able to take care of your family, home? If no, why not?

• Where do you work? What kind of work do you do? Are you able to do what is expected of you and what you expect of yourself?

• If retired, what do you do with your time? What did you do before you retired?

• When did you start to menstruate? Was this earlier or later than other women in your family? Do you have light, heavy or irregular menstrual flows?

• How many children have you had? How much did they weigh at birth? Were you told you had diabetes during any pregnancy?*

• Were you able to breastfeed your children if you wanted to?

• Are you attempting to get pregnant but cannot?*

• Have you noticed any changes in your ability to have an erection?*

• Are you trying to have children but cannot?*

• What kind of stressors do you have?

• How do you deal with stress or problems?

• What is your support system? To whom do you turn when you have a problem?

• Do you think medicine should still be taken even though you feel okay?

• Do any of your prescribed therapies cause any conflict in your value–belief system?*

Important health information

Past health history

During an assessment, the patient should be questioned about the general state of health and if there have been any changes. In addition, the patient or significant other should be specifically questioned about previous or current endocrine abnormalities and abnormal patterns of growth and development.

Medications

The patient should be questioned about the use of all medications (both prescription and over-the-counter drugs) and any herbs and dietary supplements, as well as the reason for taking the medication, the dose and the length of time taken. The patient should specifically be asked about the use of hormone replacements. Information that the patient is currently taking hormone replacements, such as insulin, thyroid hormones or corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone), helps direct the nurse regarding possible problems associated with the use of these agents. For example, corticosteroids may cause glucose intolerance in the susceptible patient by increasing glycogenolysis and insulin resistance. The side effects and adverse effects of many non-hormone medications can contribute to problems affecting endocrine function. For example, many drugs can affect blood glucose levels (see Ch 48).

Functional health patterns

Health perception–health management pattern

Inquiry should be made about the patient’s general healthcare and healthcare behaviours. Such an inquiry might result in the identification of vague, non-specific symptoms that could suggest an endocrine problem.

Heredity can play a major role in the occurrence of endocrine problems. The patient should be questioned about the following conditions in family members: diabetes mellitus or insipidus; hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, goitre; hypertension or hypotension; obesity; infertility; growth problems; phaeochromocytoma (neoplastic tumour of the adrenal medulla or sympathetic ganglia); autoimmune diseases (e.g. Addison’s disease); and adrenal hyperplasia. Asking the question ‘Are there any other members of your family who have, or have had, a similar problem?’ will assist in uncovering evidence of a familial tendency.

Nutritional–metabolic pattern

A major function of the endocrine system is regulating metabolism and maintaining homeostasis, so the patient with endocrine dysfunction will often experience alterations in nutritional metabolic patterns. Reported changes in appetite and weight can indicate endocrine dysfunction. Weight loss with increased appetite may indicate hyperthyroidism or diabetes mellitus, particularly type 1. Weight loss with decreased appetite may indicate hypopituitarism, hypocortisolism or gastroparesis (decreased gastric motility and emptying due to autonomic neuropathy) from diabetes mellitus. Weight gain may indicate hypothyroidism and, if the weight gain is concentrated in the truncal area, hypercortisolism. In addition, weight gain in a genetically susceptible patient may increase the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Difficulty swallowing or a change in neck size may indicate a thyroid disorder or inflammation. Questions related to increased SNS activity (e.g. nervousness, palpitations, sweating, tremors) may assist in identifying a thyroid disorder or phaeochromocytoma. Heat or cold intolerance may indicate hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, respectively.

The patient should also be asked about changes to the skin or hair, since hair distribution and skin and hair colour and texture can all indicate endocrine dysfunction. Hair loss can indicate hypopituitarism, hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism or increased testosterone and other androgens. Increased body hair may indicate hypercortisolism. Decreased skin pigmentation can occur in hypopituitarism, hypothyroidism and hypoparathyroidism, whereas increased skin pigmentation, particularly in sun-exposed areas, can indicate hypocortisolism. A patient with hypothyroidism or excess growth hormone may complain of coarse, leathery skin. A patient with hyperthyroidism may comment about fine, silky hair.

Elimination pattern

Maintenance of fluid balance is a major role of the endocrine system, so questions related to elimination patterns may uncover endocrine dysfunction. For example, increased thirst and urination can indicate diabetes mellitus or insipidus. The patient should be asked about the frequency and consistency of bowel movements. Frequent defecation may indicate hyperthyroidism. Large-volume, watery stools or faecal incontinence may indicate autonomic neuropathy of diabetes mellitus. Constipation is also seen in the patient with diabetes mellitus, as well as in hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism and hypopituitarism.

Activity–exercise pattern

The nurse should ask about energy levels, particularly as compared with the patient’s past energy level. Fatigue and hyperactivity are two common problems associated with endocrine problems. The major effect of endocrine dysfunction on the activity–exercise pattern is an inability to maintain previous activity levels.

Sleep–rest pattern

It is important to obtain a detailed sleep history from the patient. Sleep disturbances are frequently seen in endocrine dysfunction. The patient with diabetes mellitus or insipidus will complain of nocturia, which can severely disrupt normal sleep patterns. The patient with type 1 diabetes mellitus on a tight glucose control regimen who complains of sweating or nightmares may be experiencing hypoglycaemia. The hyperthyroid patient may complain of an inability to sleep, as may one with hypercortisolism. The patient with hypothyroidism, hypocortisolism or hypopituitarism may tell of sleeping all the time, yet still being fatigued.

Cognitive–perceptual pattern

A patient with an endocrine dysfunction will frequently manifest apathy and depression. The nurse can question both the patient and significant other to determine whether any cognitive changes are present. Memory deficits and an inability to concentrate are common in endocrine disorders. A patient report of visual changes, such as blurring or double vision, could be an indication of endocrine problems.

Self-perception–self-concept pattern

Endocrine disorders may affect the patient’s self-perception because of associated physical changes affecting appearance. Changes in weight, size and level of fatigue should be determined. The chronicity of many endocrine disorders and the need for continued therapy can affect the patient’s self-perception. The patient should be asked to describe the effects of the present illness on self-perception.

Role–relationship pattern

The nurse should ask the patient whether there have been any changes in their ability to maintain roles at home, at work or in the community. Often the patient with an endocrine disorder will be unable to sustain life’s roles. However, in most cases the patient can be advised that, with adequate management, previous roles can be resumed. This can be very reassuring for the patient and family.

Sexuality–reproductive pattern

The development of abnormal secondary sex characteristics (e.g. facial hair in a woman or decreased need for shaving in a man) should be documented. Problems with menstruation and pregnancy in a woman may indicate an endocrine disorder. Consequently, a detailed history of menstruation and pregnancy should be obtained. Menstrual irregularities are seen in disorders of the ovaries, pituitary, thyroid and adrenal glands. A female patient with a history of large babies may have had undiagnosed gestational diabetes, which may put her at a higher risk of developing diabetes mellitus. A history of inability to lactate may indicate a pituitary disorder.

Male sexual dysfunction is also frequently seen in endocrine disorders. It usually takes the form of impotence, although retrograde ejaculation can occur. Infertility in either sex warrants a full reproductive and endocrine diagnostic examination.

Coping–stress tolerance pattern

Stressors of all kinds affect the endocrine system. Areas that can cause a great deal of stress should be investigated. These include job stresses, role stresses and financial stresses. Usual coping patterns and support systems should also be discussed in order to determine whether previous coping patterns are still successful and whether support systems are meeting the patient’s current needs.

Value–belief pattern

When dealing with a patient with a chronic condition, identifying the patient’s value–belief pattern can assist the healthcare team to identify appropriate regimens. This is particularly important in a condition such as diabetes mellitus, which may require major lifestyle changes for successful management. Other endocrine disorders, such as hypothyroidism or hypocortisolism, can be easily managed with oral medication taken faithfully. Identifying a patient’s ability to make lifestyle changes or take daily medication (and increase this medication as indicated) is an important nursing function.

OBJECTIVE DATA

Most endocrine glands are inaccessible to direct examination. With the exception of the thyroid and male gonads, the glands are deeply encased in the body, protected against injury and trauma. However, assessment can be accomplished using a variety of objective data. It is imperative to understand the actions of hormones so that the function of a gland can be assessed by monitoring the target tissue.

Physical examination

It is important to keep in mind that the endocrine system affects every body system. Clinical manifestations of endocrine function vary significantly depending on the gland involved. Specific clinical findings for the various endocrine problems are discussed in Chapters 48 and 49. Regardless of the type of endocrine dysfunction, the following general examination procedure should be followed.

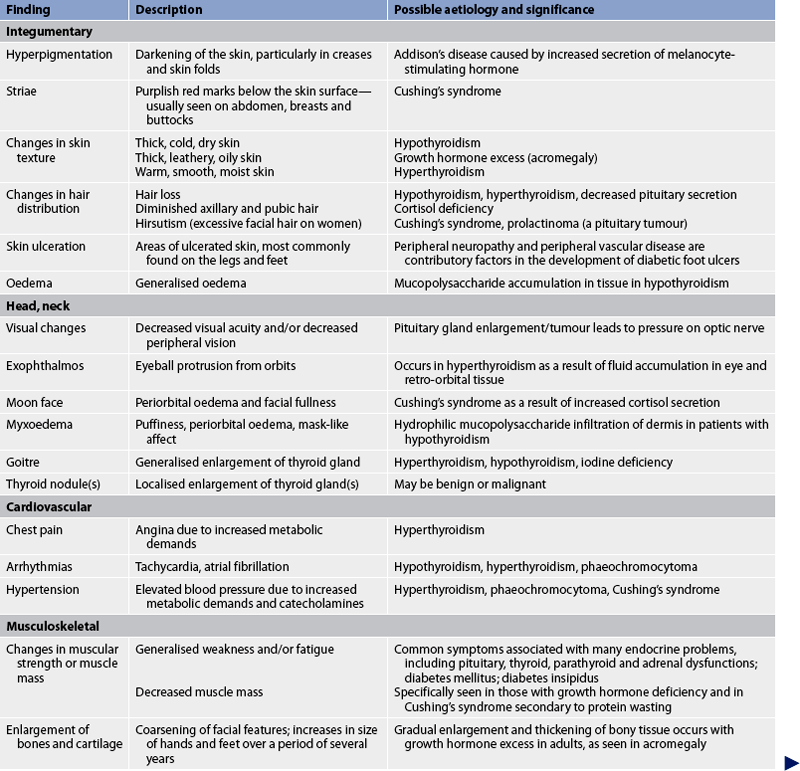

Vital signs

A full set of vital signs is taken at the beginning of the examination. Variations in temperature may be associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cardiovascular changes, such as tachycardia, bradycardia, hypotension or hypertension, may be seen with a variety of endocrine-related problems.

Height and weight

Assessment of the endocrine system includes a history of growth and development patterns, weight distribution and changes, and comparisons of these factors with normal findings. Growth pattern abnormalities suggest problems associated with growth hormone. Changes in weight may also be associated with endocrine dysfunction. Thyroid disorders and diabetes mellitus are examples of endocrine disorders that can affect body weight. Body mass index (BMI) is a height-to-weight ratio used to assess nutritional status.

It may also be helpful to compare the patient’s current body weight with their usual body weight in order to assess changes. Weight change (%) is calculated by dividing the current body weight by the usual body weight and multiplying by 100. Weight change greater than 5% in 1 month, 7.5% in 3 months or 10% in 6 months is considered severe.11

Mental–emotional status

Throughout the examination the patient’s orientation, alertness, memory, affect, personality, anxiety, and appropriateness of dress and speech pattern should be objectively assessed. Endocrine disorders can commonly cause changes in mental and emotional status.

Integument

The colour and texture of the skin, hair and nails should be noted. The overall skin colour should also be noted, as well as pigmentation and possible ecchymosis. Hyperpigmentation of the skin (particularly on the knuckles, elbows, knees, genitalia and palmar creases) is a classic finding in Addison’s disease, but is also seen with ACTH-producing tumours and acromegaly.12 The skin should be palpated for its texture and the presence of moisture. The hair distribution should be examined not only on the head, but also on the face, trunk and extremities. The appearance and texture of the hair should be examined. Dull, brittle hair, excessive hair growth or hair loss may indicate endocrine dysfunction.

Head

The size and contour of the head should be inspected. Facial features should be symmetrical. Eyes should be inspected for position, symmetry, shape and eye movement, opacity over the lens, lid lag and oedema. Visual acuity should also be checked because changes may be associated with a pituitary tumour. In the mouth, inspect the buccal mucosa and the condition of teeth, malocclusion and mottling, tongue size and fasciculations (localised, uncoordinated, uncontrollable twitching of a single muscle group).

Neck

When inspecting the thyroid gland, observation should be made first with the patient in the normal position (preferably with side lighting), then in slight extension and then as the patient swallows some water. The trachea should be midline and the neck should appear symmetrical. Any unusual bulging over the thyroid area should be noted. If there is no noticeable enlargement of the thyroid gland, palpation can be done. (Because palpation can trigger the release of thyroid hormones, palpation should be deferred in the patient with a visibly enlarged thyroid gland.) When an enlarged thyroid is noted, the lateral lobes should be auscultated with the stethoscope bell to determine the presence of a bruit.

The thyroid gland is difficult to palpate. Thyroid palpation requires considerable practice, as well as validation by a more experienced examiner. Water should always be available for the patient to swallow as part of this examination. There are two acceptable approaches to thyroid palpation: anterior or posterior. For anterior palpation the nurse stands in front of the patient, with the patient’s neck flexed. The nurse places the thumb horizontally with the upper edge along the lower border of the cricoid cartilage. The thumb is moved over the isthmus as the patient swallows water. The fingers are then placed laterally to the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and each lateral lobe is palpated before and while the patient swallows water.

For posterior palpation the nurse stands behind the patient. With the thumbs of both hands resting on the nape of the patient’s neck, the nurse uses the index and middle fingers of both hands to feel for the thyroid isthmus and for the anterior surfaces of the lateral lobes. To facilitate the examination of each lobe and to relax the neck muscles, the nurse asks the patient to flex the neck slightly forwards and to the right. The thyroid cartilage is displaced to the right by the left hand and fingers. The nurse palpates with the right hand after placing the thumb deep and behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle with the index and middle fingers in front of it; the area is palpated with the right hand (see Fig 47-12). While this is done, the patient is asked to swallow water. This procedure is then repeated on the left side. The thyroid is palpated for its size, shape, symmetry and tenderness, and for any nodules.

In a normal person the thyroid is often not palpable. If palpable, it usually feels smooth, with a firm consistency, and is not tender with gentle pressure. Nodules, enlargement, asymmetry or hardness is abnormal, and the patient should be referred for further evaluation.

Thorax

The thorax should be inspected for shape and characteristics of the skin. The presence of gynaecomastia in men should be noted. Lung sounds and heart sounds are auscultated, and the presence of adventitious lung sounds or extra heart sounds should be noted.

Abdomen

There are no specific abdominal examination findings for endocrine dysfunction other than skin characteristics and hyperactive or hypoactive bowel sounds.

Extremities

The size, shape, symmetry and general proportion of the hands and feet should be assessed. The skin should be inspected for changes in pigmentation and the presence of lesions and oedema. Muscle strength should be evaluated, as well as deep tendon reflexes. In the upper extremities, the presence of tremors is assessed by placing a piece of paper in the outstretched fingers, palm down.

Genitalia

The hair distribution pattern should be inspected. A diamond pattern in women is an abnormal finding and may indicate endocrine dysfunction. For males, the testes should be palpated; for females, any clitoral enlargement should be noted.

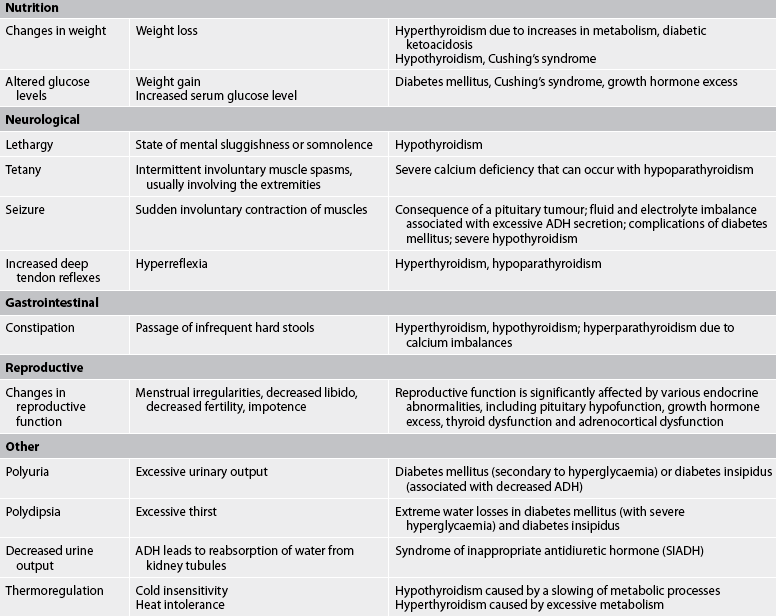

Common assessment abnormalities related to the endocrine system are presented in Table 47-6.

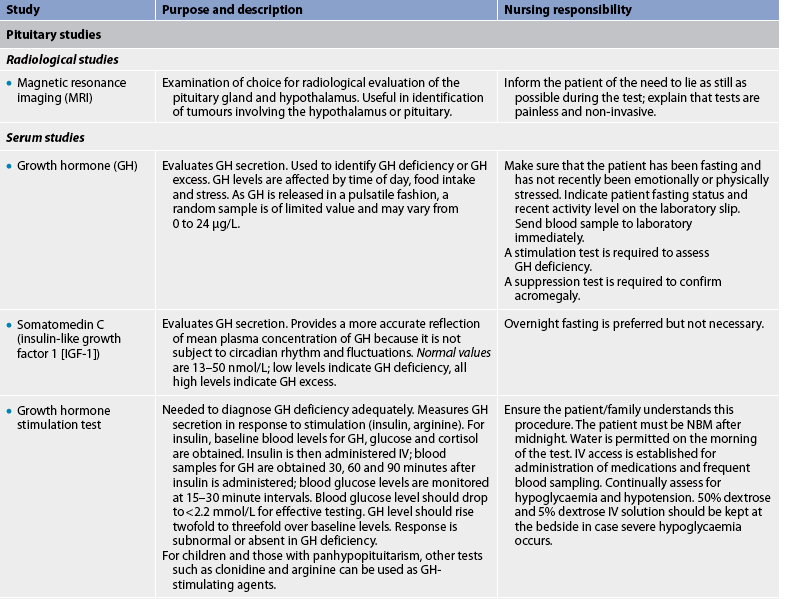

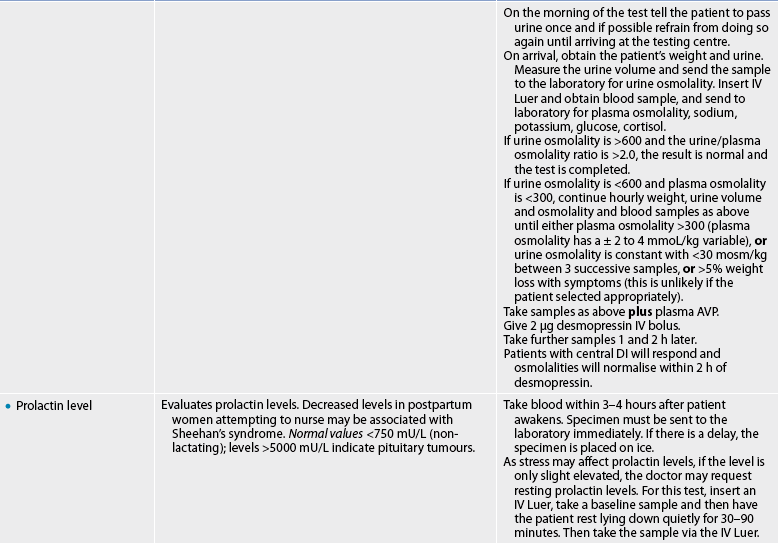

Diagnostic studies of the endocrine system

Accurately performed laboratory tests and radiological examinations contribute to the diagnosis of an endocrine problem. Laboratory tests usually involve blood and urine testing. Ultrasound may be used as a screening tool to localise endocrine growths, such as thyroid nodules. Radiological tests include regular X-ray, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). With all diagnostic testing, the nurse is responsible for explaining the procedure to the patient and family. Diagnostic studies common to the endocrine system are presented in Table 47-7.

LABORATORY STUDIES

Laboratory studies used to diagnose endocrine problems may include direct measurement of the hormone level, or they may provide an indirect indication of gland function by evaluating blood or urine components affected by the hormone (e.g. electrolytes).

Hormones with fairly constant basal levels (e.g. T4) require only a single measurement. Notation of sample time on the laboratory slip and sample is important for hormones with circadian or sleep-related secretion (e.g. cortisol). Evaluation of other hormones may require multiple blood sampling, such as in suppression (e.g. dexamethasone) and stimulation (e.g. glucose tolerance) tests. In these situations, it is often necessary to obtain intravenous access to administer medications and fluids and to take multiple blood samples.

Pituitary studies

Disorders associated with the pituitary gland can manifest in a wide variety of ways because of the number of hormones produced. There are many diagnostic studies that evaluate these hormones either directly or indirectly. The studies used to assess function of the anterior pituitary hormones relate to GH, prolactin, FSH, LH, TSH and ACTH.

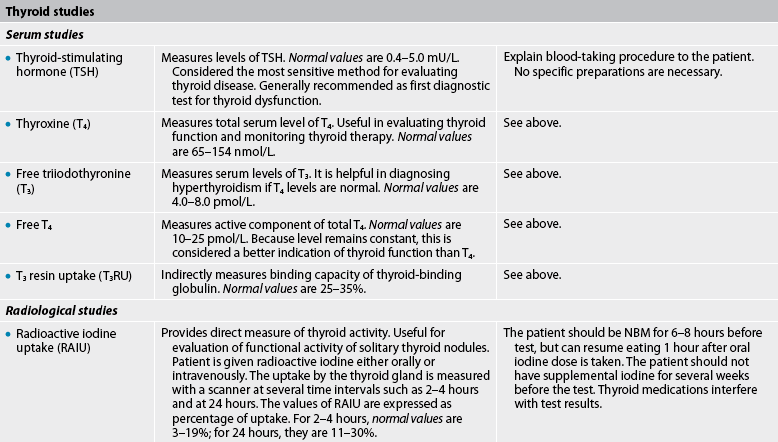

Thyroid studies

A number of tests are available to evaluate thyroid function. The most sensitive and accurate laboratory test is measurement of TSH; thus, it is often recommended as a first diagnostic test for evaluation of thyroid function.13 Common additional tests ordered in the presence of abnormal TSH include total T4, free T4 and total T3. Free T4 is the unbound thyroxine and is a more accurate reflection of thyroid function than total T4. Less common tests that are used to help in the differentiation of various types of thyroid disease include T3, free T3 resin uptake, thyroid autoantibodies, thyroid scanning, ultrasound and biopsy.

Parathyroid studies

The only hormone secreted by the parathyroid glands is PTH. Because the function of PTH is to regulate serum calcium and phosphate levels, abnormalities in PTH secretion are reflected in the calcium and phosphate levels. For this reason, diagnostic tests for the parathyroid gland typically include PTH, serum calcium and serum phosphate levels.

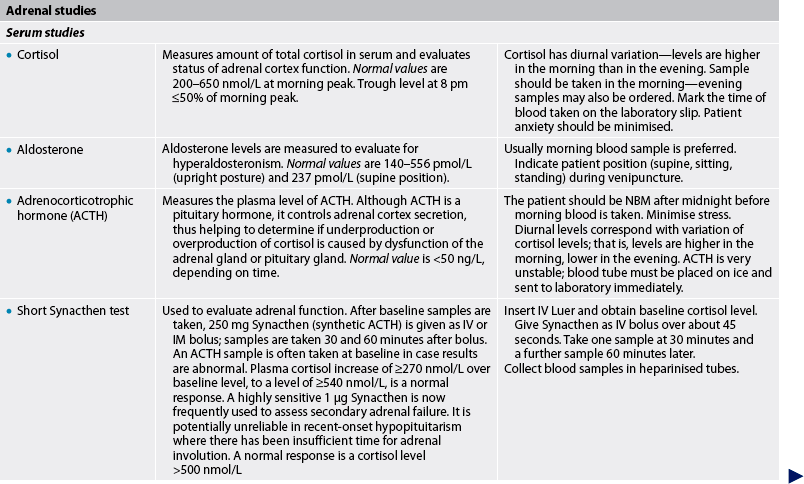

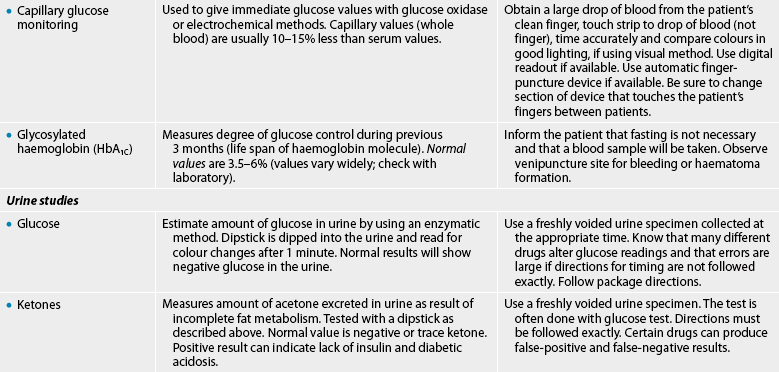

Adrenal studies

Diagnostic tests associated with the adrenal glands focus on the three types of hormones secreted: glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids and androgens. These hormone levels can be measured in both blood plasma and urine. If urine studies are used, these will usually be done as a 24-hour urine collection. The major advantage of a 24-hour urine sample is that the short-term fluctuations in hormone levels seen in plasma samples are eliminated.14,15

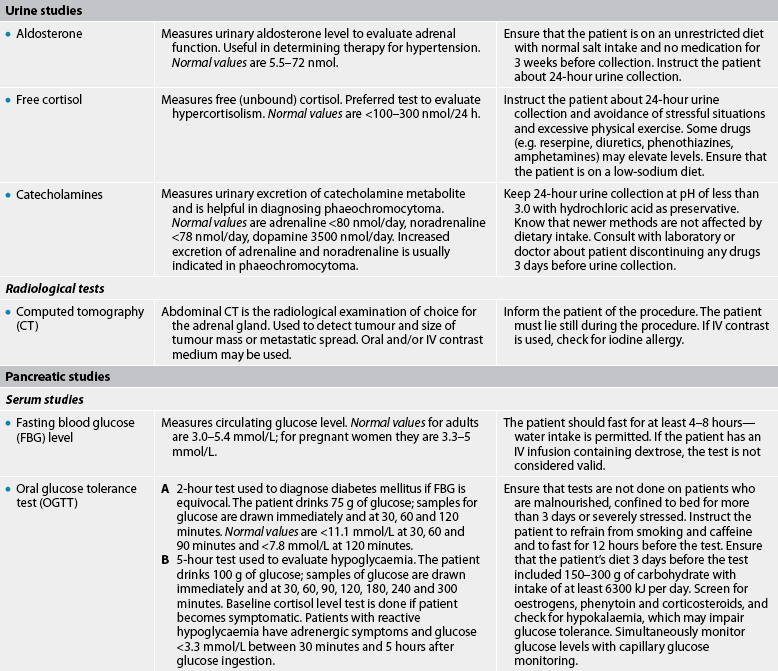

Pancreatic studies

The tests given in Table 47-7 are used to evaluate the metabolism of glucose. They are important in the diagnosis and management of diabetes. (Diagnostic studies for diabetes are also discussed in Ch 48.)

1. A characteristic common to all hormones is that they:

2. A patient is receiving radiation therapy for cancer of the kidney. The nurse monitors the patient for signs and symptoms of damage to the:

3. A patient has a serum sodium level of 152 mmol/L. The normal hormonal response to this situation is:

4. All cells in the body are believed to have intracellular receptors for:

5. When obtaining subjective data from a patient during assessment of the endocrine system, the nurse asks specifically about:

6. An appropriate technique to use during physical assessment of the thyroid gland is:

7. Endocrine disorders often go unrecognised in the older adult because:

8. An abnormal finding by the nurse during an endocrine assessment would be:

9. A patient has a total serum calcium level of 1.75 mmol/L. If this finding reflects hypoparathyroidism, the nurse would expect further diagnostic testing to reveal:

1 Low MJ. Neuroendocrinology. In: Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, et al, eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008.

2 Eliopoulos C. Gerontological nursing, 7th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

3 Goodman HM. Basic medical endocrinology, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

4 Greenspan FS. The thyroid gland. In Greenspan FS, Gardner DG, eds.: Basic and clinical endocrinology, 8th edn., New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007.

5 Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, et al. Principles of endocrinology. In: Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, et al, eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008.

6 Guillemin R. Hypothalamic hormones a.k.a. hypothalamic releasing factors. J Endocrinol. 2005;184(1):11–28.

7 Styne D. Growth. In Greenspan FS, Gardner DG, eds.: Basic and clinical endocrinology, 8th edn., New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007.

8 Gordon C, Craft J. Shock. In: Craft J, Gordon C, Tiziani A, eds. Understanding pathophysiology. Sydney: Elsevier, 2011.

9 DeGroot LJ. Diagnosis and treatment of Graves’ disease. Thyroid Disease Manager. Available at www.thyroidmanager.org/Chapter11/11-frame.htm, Updated 1 April 2010. accessed 3 January 2011.

10 Shoback D, Marcus R, Bihle D. Metabolic bone disease. In Greenspan FS, Gardner DG, eds.: Basic and clinical endocrinology, 8th edn., New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007.

11 Wilson SF, Giddens JF. Health assessment for nursing practice. St Louis: Mosby, 2009.

12 Jarvis C. Physical examination and health assessment, 6th edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2008.

13 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE). AACE Thyroid Task Force medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Amended. Available at http://www.aace.com/pub/pdf/guidelines/hypo_hyper.pdf, 2006. accessed 20 December 2010.

14 Pagana KD, Pagana TJ. Diagnostic and laboratory test reference, 9th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2009.

15 Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma: recommendations for clinical practice from the First International Symposium, October 2005. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3(2):92–102.