In Chapter 5 we explained the “inner logic” of the Affordable Care Act, showing that the desire to legislate universal coverage necessarily carried with it a string of further features, such as community rating and the individual mandate. Then in Chapter 6 we outlined some of the immediate consequences of each of these features, using simple economic logic to explain why the ACA would backfire, and drawing on the government’s own estimates to get a sense of how bad the fallout would be.

Relying on the material developed in the prior two chapters as our foundation, in this chapter we look ahead to provide a qualitative sketch of what is likely to unfold in the US markets for health insurance and health care over the next few decades. To anticipate our prognosis: the current framework is utterly unsustainable. The perverse incentives inherent in the system before passage of the ACA have only been exacerbated by the massive burst of new legislation. Over time, the problems spawned by the ACA will continue to grow, while its ostensible benefits will remain elusive.

At some point in the not-too-distant future, Americans will realize that they must make another momentous decision when it comes to the provision of health care and health insurance. One path would be a massive rollback of the federal government’s interventions into these markets.

Unfortunately, if history is any guide, the pundits and politicians will probably convince enough of the public to “finish the reform” initiated by Barack Obama, and move the United States to a “single payer” system in which the government pushes those pesky private sector insurance companies out of the picture and directly pays for all major health care in the country. It is necessary to understand the urgency of the situation in order to appreciate the strategies outlined later in this book, which will guide Americans through what appears to be an inevitably approaching storm.

The most obvious impact of the ACA worth closely monitoring was the increase in health insurance premiums that most Americans would experience. Readers who followed the pundits and political debates may recognize a feeling of two parallel universes, as conservative media outlets trumpeted studies showing enormous projected rate hikes— particularly for young people in states that previously had little regulation of the health insurance market—while liberal media outlets published reports showing the “good news” that health care spending was growing more slowly than anybody had expected.1 The average American could understandably feel helpless in parsing through the analyses, since the experts in the two partisan camps—those who were demonizing the Obama Administration versus those who defended it—seemed to be making completely opposite claims. Was one side in the debate simply fabricating figures?

As with most things involving economics and statistics, neither side was necessarily lying; they didn’t need to. By carefully choosing modeling assumptions, the group of individuals being examined, and the relevant baseline, an analyst could truthfully paint a picture of the ACA either sharply increasing premiums or making health insurance much more affordable. In this section we’ll explain some of the biggest sources of confusion.

When considering the impact of the ACA on health insurance premiums, the most important thing to keep straight is whether we’re looking at premium hikes for a given person or premium hikes for a given type of policy. It is precisely this ambiguity that allows friends and foes of Obama to point at the exact same study and claim, “We told you so!”

This distinction between people and policies is crucial because the ACA—with its requirement of a suite of “essential health benefits”— forces people to buy insurance plans that are more generous than what these people may have wanted to buy voluntarily. To return to a car analogy: if the government forces everybody to buy a Ferrari, people who previously drove Toyotas are going to face a huge increase in their car payments, even if the model 2015 Ferrari is only modestly more expensive than the model 2014 Ferrari.

To see the importance of picking a baseline, consider a 2009 CBO analysis on the impact of proposed legislation on 2016 premiums. Ironically, this CBO estimate gave both groups the talking points they wanted to say that ObamaCare was either awful or wonderful.

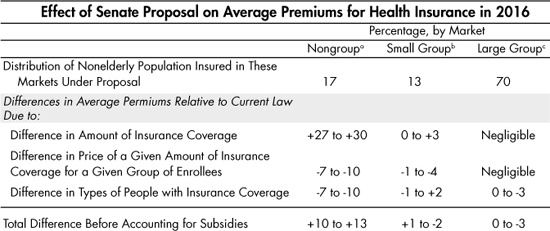

Table 7-1. CBO Estimate (Made in 2009) of ACA’s Impact on 2016 Premiums

The CBO estimate in Table 7-1 was made back in 2009, so for our purposes the specific numbers in the table aren’t as important as the various factors that the CBO analysis so clearly delineates. The top row shows the distribution of the US population into various types of insurance offerings; for example, the CBO projected the biggest impacts on premiums in the nongroup market, which only affected 17 percent of the population. For these people, the effect of having to buy more generous insurance plans was quite large, increasing premiums by 27 to 30 percent. However, even within this segment of the market, the total projected effect on premiums was a more modest 10 to 13 percent hike. That’s because the CBO estimated that the ACA would reduce the premiums necessary to provide a given insurance policy, since (among other things) the individual mandate would force young and relatively healthy people into the insurance pool who might otherwise not buy coverage. Notice also that the CBO report projected modest overall impacts on (small and large) group insurance. Here, the effect of the “essential health benefits” requirements in the ACA is less significant than for the nongroup segment, because existing employer plans typically were in or near compliance with the standards.

Thus we see that the 2009 CBO forecast of the legislation’s impact on premiums offered something for everyone: Obama’s critics could highlight the top left figure of a 27 to 30 percent increase, while Obama’s allies could claim that most people would see a slight drop in premiums. Relying on the 2009 forecast, neither side would be lying, but it would be hard for an average member of the public to parse the claims to understand the true situation.

In addition to the 2009 forecast, we can see other, more recent examples of different groups using the same data to reach (seemingly) opposite conclusions about the ACA. In September 2013, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a slender report discussing the premiums that individuals would face once the new exchanges opened. (Recall that the Healthcare.gov website officially launched—with dramatic problems—on October 1, 2013.) The Abstract of the HHS report concluded on this cheerful note: “[N]early all consumers (about 95%) live in states with average premiums below earlier estimates.”2

That sounds like great news, right? The problem is, the HHS report was comparing the 2014 premiums to earlier estimates of 2014 premiums. That’s not what most people had in mind when they wondered, “How much is ObamaCare going to cost me?” Indeed, former CBO director Douglas Holtz-Eakin said this of the HHS report: “There are literally no comparisons to current rates. That is, HHS has chosen to dodge the question of whose rates are going up, and how much.”

To get a better sense of what was really in store for most Americans, scholars at the Manhattan Institute used the very same data compiled by the HHS, but this time asked the question: what are some pre-ACA and post-ACA apples-to-apples premium comparisons for various demographic groups? There were many permutations in the analysis, but here we can reproduce some of their key findings.3 When looking at the cheapest insurance plans for 27-year-olds in 2013 compared to the cheapest plans that had just been announced for the ACA exchanges, the Manhattan Institute analysts found that on average (across states) rates went up 97 percent for men and 55 percent for women. (In Nebraska the sticker shock was the worst, with rates for the cheapest policy available to 27-year-old men increasing 279 percent.) Perhaps surprisingly, the Manhattan Institute analysts found a similar pattern even for 40-year-olds, with men on average seeing the cheapest available plan increasing 99 percent in price while women faced a hike of 62 percent.

Now to be sure, this technique overstates the impact of the ACA for those people in 2013 who weren’t buying the cheapest health insurance policy available. (Specifically, people who had health insurance that was already in compliance with the ACA’s “essential health benefits” requirements would not see such drastic premium hikes.) On the other hand, what of the young and healthy people who originally chose not to buy health insurance because they had more important things to do with their limited budgets? Now that the ACA is forcing many of them to spend large amounts on health insurance, these particular Americans have seen an infinite percentage increase in their premiums (or fines, if they choose to pay the IRS the penalty). Keep that in mind when you see estimates of the “average” (and finite!) effects of the ACA on premiums: this group of Americans (which could be millions of people) is obviously not having their percentage hike entering the computation.

To get an estimate of the increase in premiums across the population as a whole, we can look to Yale University’s Amanda E. Kowalski: she developed a full-blown model with all the bells and whistles, which weighted premiums by enrollment size. In a study for the Brookings Institution, she concluded:

In the vast majority of states, in the first quarter of 2014 premiums rose relative to state seasonally adjusted trends. Health insurance premiums almost always go up, but it is striking that they went up so much relative to trend…[P] remiums increased relative to seasonally adjusted trends in the first half of 2014 in the four most populous states. Across all states, from before the reform to the first half of 2014, enrollment-weighted premiums in the individual health insurance market increased by 24.4 percent beyond what they would have had they simply followed state-level seasonally adjusted trends.4

It is important to note that Kowalski’s estimates refer to the unsubsidized premium amount, meaning what health insurers are actually receiving for policies as opposed to the out-of-pocket payments made by individuals. This is yet another crucial “switch” that can be flipped on or off in the arguments over the impact of the ACA. In a typical unfolding of the current political debate, the critic of the ACA will argue that it is grossly inefficient, driving up premiums across the board. The defender will then argue that the statistics involved only look at the market rates; once we take into account the help various individuals will get from the government, then all of a sudden ObamaCare should seem like a good deal to lots of people. Whether or not this is true— we’ll see in a minute that we strongly disagree—forcing some people to subsidize the premiums of others doesn’t change the fact that multiple features of the legislation make health insurance far more expensive than it needs to be.

As of this writing, the simple truth is that we really don’t know the full impact of the ACA on typical premiums. Several elements of the original legislation were designed to ease Americans into the new regime, rather than “shocking” them upfront and giving a chance for people to demand repeal. For example, the screws don’t really tighten on the individual mandate until 2016. This feature of the ACA is supposed to force enough young and healthy people to enter the risk pool and thereby curb average costs. Insurers may be holding off on major rate hikes, waiting to see the composition of their enrollment pool once the individual mandate is at full blast.

Second, remember that the ACA contains various measures by which the federal government temporarily shares the risk of unexpectedly high claims with the insurance companies. For example, in its April 2014 analysis, the CBO wrote:

… CBO and JCT expect that reinsurance payments scheduled for insurance provided in 2014 are large enough to have reduced exchange premiums this year by approximately 10 percent relative to what they would have been without the program. However, such payments will be significantly smaller for 2015 and 2016, and they will not occur for the years following. Therefore, that program is expected to have resulted in lower premiums in 2014, to reduce premiums by smaller amounts in 2015 and 2016 than in 2014, and to have no direct effect thereafter.5

We should emphasize that a 10 percent suppression of premiums in 2014 is a very large effect. This factor alone would have been enough to force many pro-ACA pundits to abandon the claim that “ObamaCare proved the worrywarts wrong.”

For a third example, the tax on employer-provided “Cadillac plans” isn’t even scheduled to go into effect until 2018. This 40 percent (!) surtax on high-premium plans could have an enormous impact on the health insurance market for group plans. Until then, current talk of the ACA’s ultimate impact on private health insurance, and the fate of the taxpayer, is quite premature.

So far, we’ve outlined three major wild cards in the legislated unfolding of the ACA. But in addition to the designed delay, the Obama Administration has also postponed the application of onerous provisions through Executive fiat. For example, in response to the outrage over the millions of plan cancellations, the Administration (as of this writing) has twice extended the grace period for non-compliant plans— meaning that people can “keep their plan if they like it” through September 2017.6 It is not surprising that some of the critics’ worst fears have not yet been realized, since the Obama Administration postponed several of the most onerous portions of the new legislation.

It is undeniable that a key result of the ACA will be a huge expansion of the number of Americans who are dependent on the federal government for their health care, either directly (through Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans Administration, etc.) or indirectly (through generous subsidies for otherwise unaffordable “private” health insurance). As usual, we can use the government’s own estimates to demonstrate our claim.

First let’s consider Medicaid, the federal government’s program (acting in cooperation with state governments) for providing health care financing to low-income Americans. For those who supported passage of the ACA, one of the most obvious “gains” it achieved was expanding Medicaid eligibility and federal funding for the program. The CBO estimates that by 2018, the ACA will place an additional 13 million people on Medicaid and CHIP (the Children’s Health Insurance Program), and that “the added costs to the federal government for Medicaid and CHIP attributable to the ACA will be $20 billion in 2014 and will total $792 billion for the 2015–2024 period.”7

Second, besides expanding existing government programs (i.e. Medicaid and CHIP), the ACA obviously will foster an enormous population dependent on large government subsidies of policies offered through the “exchanges.” Again relying on the latest CBO report, the government projects that 25 million Americans will receive their health insurance through the exchanges by the year 2017. Of these 25 million, 19 million (76 percent) will be subsidized, while only 6 million (24 percent) will pay the full “market” price. Thus there will be three subsidized people for every one person paying full freight for insurance purchased through the individual marketplaces.

Also note that the size of these subsidies will be quite large: “CBO and JCT project that the average subsidy [per subsidized enrollee] will be $4,410 in 2014, that it will decline to $4,250 in 2015, and that it will then rise each year to reach $7,170 in 2024.”8 Let’s be sure we understand what that figure means: the CBO is saying that if you add up all of the money the federal government will use (either in direct spending or through tax credits) to subsidize exchange premiums in a given year, divided by the total number of subsidized individuals it expects to buy coverage through the exchanges, then the result will be $4,250 in 2015 and $7,170 by 2024.

It should thus be crystal clear that the millions of people added to Medicaid, CHIP, and the ACA exchanges will generally be utterly dependent on the federal government for their health care.9 At the same time, various measures of the ACA are projected to significantly reduce the incentives for employers to offer coverage to their employees.

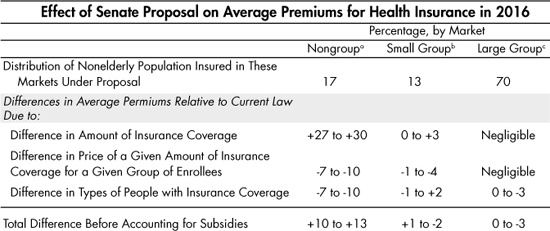

The following table is the CBO’s snapshot (as of April 2014) of the various trends in sources of health insurance coverage attributable to the ACA:

Table 7-2. CBO Estimate (April 2014) of ACA’s Impact on Sources of Insurance Coverage

Regarding Table 7-2, we will walk through the column for the year 2018, because the numbers have leveled off at this point and are fairly representative of the medium-term impact. The numbers in the bottom group show the CBO’s projections for the change in insurance coverage (by various sources) due to the ACA; the numbers in the top group show the baseline, if the ACA had never been passed.

The table shows that in 2018, the CBO projects an additional 13 million Americans will have Medicaid and CHIP coverage—an increase of about 40 percent from the baseline of 33 million, for a total of 46 million people getting their health care expenses paid through these programs. The CBO also projects that 25 million Americans will be covered through exchanges, an “infinite” percentage increase relative to the (non-existent) baseline. In contrast, employer-based coverage will fall by 8 million employees, about a 5 percent drop from a baseline of 164 million. Nongroup and other coverage will fall by 4 million, about a 15 percent drop relative to the baseline of 26 million.

Added together, the CBO projects that in 2018, the exchanges, Medicaid, and CHIP will have picked up 38 million people, while employer-based and individual coverage (outside of the exchanges) will have dropped 12 million, for a net fall in the ranks of the uninsured by 26 million. It is worth emphasizing that this projected net drop in 26 million uninsured people occurs because of a gross increase of 38 million people getting their coverage from the government-facilitated programs, with the 12 million-person discrepancy due to a shrinking of insurance coverage through non-governmental sources.

But wait: we need to make an adjustment to the figures we’ve been using. You see, the CBO reports are very nice and tidy—the authors do a great job spelling out the assumptions they used to generate the numbers that come out the other end—but typically they analyze the ACA from the perspective of the “nonelderly population.” In other words, the enrollment projections in Table 7-2 completely ignore Medicare, as well as the millions of elderly people on Medicaid.

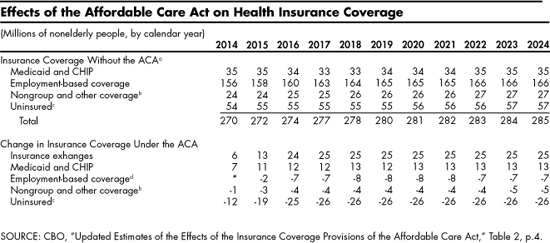

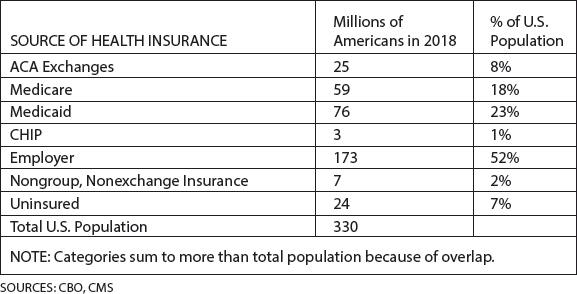

Using projections from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in Table 7-3 we give a fuller picture of the total number of Americans who will receive their health insurance through various channels by the year 2018:10

Table 7-3. Government Estimates of Sources of Health Insurance in Year 2018

As Table 7-3 indicates, the central warning of this chapter—that the US is headed toward an explicitly “single payer” framework in which the government directly pays for everyone’s health care—will be significantly closer by 2018, using the government’s own figures. According to this particular forecast, out of a projected 330 million Americans total, fully 126 million—almost 40 percent—will receive their health insurance through government channels, with the vast majority getting explicit payments from the government.

If the government’s own projections admit such a future, imagine what will actually happen as the economy limps along, with more employers kicking workers off their company plans and the “unintended consequences” of the ACA making truly private health insurance increasingly unrealistic. If the ACA remains intact for even just one decade, the United States will be much closer to a de facto single payer system than most people expect.

So far in this chapter, we’ve shown that premiums may be a ticking time bomb, that major elements of the ACA have yet to fully kick in and wreak havoc on the system, and that the government’s own projections show an additional 38 million people getting their insurance through government channels in the near future.

Now we are ready to explain why we can expect massive public dissatisfaction with this new state of affairs. The “solution” supposedly offered by the ACA will turn out to be like all of the previous health care “fixes” of the twentieth century: the government will massively expand its power and spending, and the public will be glad to see some apparent improvements in a few important criteria, but eventually it will become clear to the pundits and political officials that the “free market system” is still broken and the government “needs” to intervene yet again.

The overarching problem with the ACA is that it promises the economically impossible: it seeks to (1) massively increase the demand for medical services while (2) containing the growth in medical prices, and yet (3) not sacrifice the quality or availability of medical services to the public. Absent other major reforms that would massively increase the supply of medical personnel (such as an unexpected advance in robotics, special immigration waivers to bring in foreign doctors, or a rollback of government licensing requirements), this combination of features is truly impossible.

In practice, the government will play “whack a mole” with all three objectives, opting to partially satisfy each of them—which means it will fully satisfy none of them. Yes, the feds have expanded the demand for health care services, but they won’t actually achieve the original goal of “universal coverage.” And yes, the government will probably “bend the cost curve” and push out the day when its major entitlement programs officially run out of money, but the enormous “savings” that are built into the ACA’s rosy budget accounting will prove politically impossible to push through: future legislators will realize that cutting back so sharply on reimbursement rates for various medical services will simply make them unavailable to anyone relying on the government system. Finally, Americans will notice the overall system become increasingly bureaucratic, impersonalized, and sluggish, with barebones one-size-fits-all service rationed out in diluted form by an overworked core of frazzled “health care providers.”

We realize we are painting a bleak vision of the not-too-distant future, but it’s important to fully understand the situation. Let us buttress our bold claims with some numbers.

• “Universal” coverage? Hardly!

The government’s own projections of health care coverage from the ACA have been consistently scaled back as time has passed. Table 7-4 draws on a five different CBO reports, issued from March 2010 through April 2014, to show the consistent drop in expectations regarding “universal coverage”:

Table 7-4. Government Reduces Projections of Coverage Over Time

As Table 7-4 shows, the forecast for approximating universal coverage slightly improved from March 2010 to March 2011. But from that point forward, every year the CBO became more pessimistic on some dimension. Over the four-year period (from the first report in March 2010 through the April 2014 report), the CBO scaled back its estimates of 2019 coverage by seven million people. Note that the most recent estimate has the CBO projecting that even by 2019, there will still be 8 percent of nonelderly legal residents who lack coverage, and 11 percent of the total nonelderly population if we include illegal immigrants (not shown).

Here’s another way of looking at the situation. That latest CBO forecast also says (not shown in the previous table) that without passage of the ACA, in 2019 the US would have had 56 million uninsured people among the nonelderly. But because the ACA was passed, the CBO is projecting that only 30 million will lack coverage. That change of “26 million” also shows up in the bottom row of the third column in Table 7-4. That means the ACA won’t even cut the problem of uninsured Americans in half, let alone solve it. And this is for the year 2019, a full decade after the ACA was passed. Would anybody have supported President Obama if he had announced in 2010, “I am going to sign this legislation that over the next ten years will add a trillion dollars in new taxes, will cause millions of you to get kicked off your existing insurance plans, and when all is said and done will leave us with 30 million Americans who still lack health insurance. Now who’s with me?”

• ACA only “reduces the deficit” via massive cuts to Medicare reimbursements

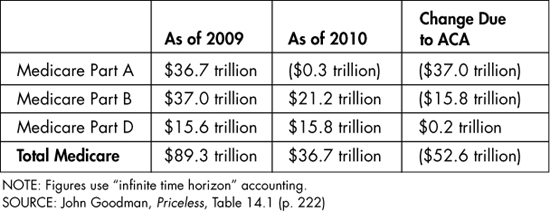

You may remember that back in Chapter 3, when discussing the Ponzi schemes of Social Security and Medicare, we summarized their literal bankruptcy as of 2009. That’s because that passage of the ACA did indeed dramatically improve—at least on paper—the solvency of Medicare. (To be sure, normal accounting still says it’s bankrupt, just not as bankrupt.) In his own book indicting the US health care system, economist John Goodman emphasized just how dramatically the ACA affected the Medicare spending projections with the following table:

Table 7-5. Impact of the ACA on Long-Term Medicare Unfunded Obligations

We’ll let Goodman explain the meaning of these figures, and why they should make us very concerned about the future of US health care delivery:

… [T]he Affordable Care Act uses cuts in Medicare to pay for more than half the cost of expanding health insurance for young people, but it contains no serious plan for making Medicare more efficient. All it really proposes to do is pay less to doctors and hospitals. That’s why the Medicare actuaries are predicting greatly reduced access to care for the elderly and the disabled.

Most serious people inside the Washington, DC beltway believe these cuts will never take place. The reason: our experience with similar cuts in Medicare under previous legislation. If Congress has been unwilling to allow reductions in doctor fees for nine straight years under previous legislation, how likely is it to allow the even greater spending reductions called for under ACA?11

We realize that the incomprehensibly gigantic figures of Medicare’s long-run unfunded liabilities may not resonate with you. Consider instead Table 7-6, which is also adapted from Goodman’s book. It summarizes a National Center for Policy Analysis study that estimated the impact the ACA would have on Medicare recipients, broken up by age:

Table 7-6. Lifetime Medicare Benefits versus Payments, Before and After ACA

Table 7-6 shows us that the passage of the ACA—with its built-in cuts to Medicare expenditures—instantly changed the expected value of the entitlement program. Moreover, the changes do not hit all Americans equally, but instead tighten the screws as time passes. For people who turned 65 when the analysis was published (in 2011), the ACA was responsible for a reduction of $27,310 in their lifetime net benefits (using discount rates to compare dollars in different years of life) of the Medicare program. But for people who will turn 65 in 2030, the ACA causes more than double the hit, reducing their lifetime net benefits by more than $58,000. Indeed, for these people, Medicare is a losing proposition, considered as an investment vehicle: over their lifetimes, they can expect to pay $251,660 in a combination of payroll taxes while working and then health insurance premiums when retired, but will only draw out $240,233 in medical reimbursements after “going on Medicare.”

Our point in reproducing these Medicare projections isn’t to pine for a continuation of the program as it stood on the eve of the ACA’s passage. Rather, we are simply warning the reader that a massive financial crunch in the health care sector is coming. The government is going to drastically scale back its reimbursements to hospitals and doctors through Medicare, and to the extent that some of these projected cuts are postponed—perhaps because the collapse in care for Medicare patients becomes too intolerable politically—then all of the rosy fiscal analyses of the ACA go out the window.

• The expansion of government-provided health insurance, combined with watered-down employer plans, will lead to longer waits and cattle-car care

It is inevitable that hospitals, doctors’ offices, and health insurance companies will adopt more bureaucratic and penny-pinching measures in response to the ACA’s overhaul. We’ve already shown the farce of the promise of “universal coverage,” but even those people who have health insurance—particularly if they are dependent on the government to pay the bills—will learn the important difference between health insurance and health care. Navigating through the health care system will become more Kafkaesque as the years pass.

In his book Priceless John Goodman gives many anecdotes and statistics to demonstrate that having “guaranteed” health coverage is not at all the same thing as having actual access to medical care. For example, almost one-third of US doctors refuse to accept Medicaid patients, period, and even those who do accept them will often take on only a limited number. Medicaid patients in Denver had to endure six- to eight-month waits for appointments at specialty clinics.12

HEALTH “COVERAGE” DOESN’T NECESSARILY EQUAL HEALTH CARE

A nonprofit group tried to enroll people in the “free” health insurance offered through “Medi-Cal,” California’s Medicaid program, and this is what happened:

“Of the 50 calls made over a three-month period, only 15 calls were answered and addressed. The remaining 35 calls were met by a recording that stated, “Due to an unexpected volume of callers, all of our representatives are currently helping other people. Please try you call again later,” followed by a busy signal and the inability to leave a voice message. For the 15 answered calls, the average hold time was 22 minutes with the longest hold time being 32 minutes.”13

The problems of rationed, cattle-car care are not limited to Medicaid. Consider the other major vehicle for expanding health insurance coverage, namely the exchanges or “marketplaces.” In early 2014, after seeing the exchanges in operation, the CBO revised downward its forecasts for exchange premiums, since they were coming in cheaper than it had expected. Naturally, this was welcome news to fans of President Obama. But it’s interesting to read the April 2014 CBO discussion of why it was revamping its estimates:

A crucial factor in the current revision [of forecasted exchange premiums] was an analysis of the characteristics of plans offered through the exchanges in 2014. Previously, CBO and JCT had expected that those plans’ characteristics would closely resemble the characteristics of employment-based plans throughout the projection period. However, the plans being offered through the exchanges this year appear to have, in general, lower payment rates for providers, narrower networks of providers, and tighter management of their subscribers’ use of health care than employment-based plans do.14

We should also expect employer-based plans to become more bureaucratic and mediocre. Remember that the whole point of the ACA’s whopping 40 percent surtax on employer-provided health plans that are too expensive—so-called “Cadillac plans”—is to convince employers to stop giving their employees such generous plans.

Note the irony here. On the one hand, the “essential health benefits” aspect of the ACA forces health insurance plans to meet minimum standards, while the looming 2018 surtax on Cadillac plans effectively enacts maximum standards. Thus the ACA surrounds its enemy, attacking from two fronts—where the “enemy” in this case is product variety in a market, giving consumers a choice among options with different prices and features.

All in all, the ACA’s projected shift of millions of people into government channels for their health insurance, combined with the dilution of the quality of existing employer-based plans, will lead to growing dissatisfaction among the public. As wait times increase, quality suffers, premiums and out-of-pocket payments continue to rise, and millions of people are fined for not being able to afford health insurance, Americans will become angry. They will realize that the “Affordable Care Act” is a cruel joke, and they will demand that the politicians in DC fix what they broke. Ironically, that is exactly what many of the ACA’s proponents secretly welcome.

As we hope our analysis in this book so far has made clear, the ACA will simply exacerbate the problems in US health care and insurance that existed circa 2009, when President Obama took office. Most Americans are going to experience a massive shock over the next few years as the provisions of the ACA fully kick in.

The tragedy of all of this is that most people will misunderstand what’s happening. In particular, they will survey the slow-motion train wreck and conclude, “Yep, that’s the free market for ya. We need more government to fix this.” This reaction will be understandable, because Americans are going to directly experience frustration with “private sector” institutions, not realizing the various government interventions are what spawn such outcomes.

For example, one of the popular provisions of the ACA that went into effect a few months after passage (in the fall of 2010) was that children (under certain conditions) would be allowed to stay on their parents’ health insurance plan until age 26, which was an extension compared to many plans at the time.15 Another aspect of the ACA that went into effect in 2010 forbid insurance companies from denying coverage to children for pre-existing conditions. This set up a scenario where a family might strategically not buy health insurance for the children, because if they later got sick they could at that time be added.

These two provisions of the ACA taken together perversely gave an insurance company an incentive to simply drop coverage for children altogether, since the law technically only said that a health plan needed to cover children through age 26 if it covered them at all. And in fact, that is precisely what happened. Yet the blame wasn’t put on the perverse incentives of the ACA. Let us quote from a news article in The Hill to show how all of this played out politically as it went down:

Health plans in at least four states have announced they’re dropping children’s coverage just days ahead of new rules created by the healthcare reform law, according to the liberal grassroots group Health Care for America Now (HCAN)….

“We’re just days away from a new era when insurance companies must stop denying coverage to kids just because they are sick, and now some of the biggest changed their minds and decided to refuse to sell child-only coverage,” HCAN Executive Director Ethan Rome said in a statement. “The latest announcement by the insurance companies that they won’t cover kids is immoral, and to blame their appalling behavior on the new law is patently dishonest.

… This offensive behavior by the insurance companies is yet another reminder of why the new law is so important and why the Republicans’ call for repeal is so misguided.”16

This episode epitomizes the dynamic in government intervention in health care: a sweeping new measure tries to transform good intentions into a better world, without even a cursory consideration of the actual effects it will have on the decisions of the major players involved. Then when the initial intervention results in a predictable, undesirable consequence, its supporters get mad at reality and double down on their stance.

Despite the official protections that the ACA gives to those with pre-existing conditions, nonetheless the health insurers have found ways to discourage HIV+ customers from enrolling. From a story five months after the ACA’s “exchanges” went into effect:

“Four Florida insurance companies offering Affordable Care Act policies are discriminating against people with HIV or AIDS, according to two health-rights organizations that plan to file a formal complaint with the federal government Thursday….

‘Not only did the companies place HIV/AIDS drugs in the plans’ highest formulary tiers — even generic drugs — they required prior authorization for any HIV/AIDS medication,’ said Wayne Turner, the National Health Law Program staff attorney who drafted the complaint. Turner said he could find no justification for such a benefit design. ‘From our reading, the companies were looking for a way around the ACA’s protections to discourage people with HIV/AIDS from enrolling in their plans.’”17

The end limit of this process is a “single payer” system, in which the federal government brushes those pesky private-sector insurance companies out of the way and directly handles medical expenses for all Americans. Think of it as Medicare starting at birth, rather than at age 65. For example, remember the debacle when Healthcare.gov was first rolled out in October 2013, and hardly anybody could even sign up? Here’s how Paul Krugman tried to do damage control a few weeks later:

Obamacare isn’t complicated because government social insurance programs have to be complicated: neither Social Security nor Medicare are complex in structure. It’s complicated because political constraints made a straightforward single-payer system unachievable. It’s been clear all along that the Affordable Care Act sets up a sort of Rube Goldberg device, a complicated system that in the end is supposed to more or less simulate the results of single-payer, but keeping private insurance companies in the mix and holding down the headline amount of government outlays through means-testing…

So [Mike] Konczal is right to say that the implementation problems aren’t revealing problems with the idea of social insurance; they’re revealing the price we pay for insisting on keeping insurance companies in the mix, when they serve little useful purpose.18

So there you have it: a monumental flaw in the implementation of the ACA so comical that nobody would have put it into a fictional story—even the harshest conservative critics of the ACA weren’t predicting that the government’s website wouldn’t work—and the ACA’s Nobel Prize-winning cheerleader tries to spin it as the fault of keeping private health insurance companies in America. That is why we can be so sure that when the ACA fails to solve the problems in US health care and insurance, these same “experts” will come back with just the solution: more government intervention and less freedom.

To provide yet more evidence of the pattern we’ve described, it will be instructive in this section to examine the topic of restrictions on patient choice. As we explained earlier in this chapter, the insurance plans offered through the ACA-established exchanges (or market-places) typically have much narrower “provider networks.” This is one of the ways insurers keep down costs and avoid massive sticker shock, given the other mandates in the ACA.

As we have warned earlier, Americans should get used to this treatment: they are going to see their freedoms and choices chipped away on various margins in the coming years, in health care as in other areas of life. Although the shriller supporters of bigger government will no doubt use the restricted choice to blame the private sector—who can forget Helen Hunt’s famous indictment of “f***ing HMO bastard pieces of sh**!” from As Good As It Gets?—the pro-ObamaCare website Vox has been buttering up its readers to the idea of restricted patient choice being a necessary evil for health “reform.” For example, in an article with the headline “Limited doctor choice plans don’t mean worse care,” Vox contributor Sarah Kliff explains:

Narrow networks are common on Obamacare’s new exchanges, as health insurers try to hold down premium prices by contracting with fewer doctors. McKinsey and Co. estimates that more than a third of the plans sold on the new marketplaces left out 70 percent of the region’s large hospitals. This unsurprisingly led to a barrage of negative headlines about insurers leaving well-known hospitals out of network.

But narrow networks aren’t all bad. Health economists actually tend to be quite fond of these products, as they help hold down spending. The potential for savings is big: limited choice plans can reduce patient spending by as much as a third, new research from economists Jon Gruber and Robin McKnight finds.19

The ostensibly good news from the Gruber/McKnight study is that an experiment in Massachusetts showed that limited choice plans not only save money (which is unsurprising) but also apparently had no adverse consequences on patient health. Specifically, in 2011 the state government of Massachusetts offered large financial incentives—paying three months of the insurance premiums—to some of the state’s employees to switch to a limited choice plan. The Gruber/McKnight study then looked at the employees who took the plan and those who kept the original plan, both a year before and a year after the switch (i.e. in 2010 and then in 2012). We’ll quote from the Vox article’s summary of their findings:

1. With the three-month premium holiday, lots of people switched to the narrow network plan …

2. Health spending fell by one-third for those who switched …

3. Patients used more primary care—and got fewer specialty services… While urgent care clinics and emergency room travel didn’t change, trips to the hospital became much longer, by as much as 40 miles.

4. The narrow network hospitals provided just as good care…. Gruber and McKnight look at a typical panel of health indicators, like how many heart attack patients die within a month and re-admission rates where the hospital messed up the first time.

They find that hospitals in and outside of the narrow plans look pretty similar; there’s no significant difference in quality. “Enrollment in limited network plans is not associated with any change in the quality of accessible inpatient hospital care,” Gruber and McKnight conclude.

Gruber and McKnight were unable in this particular study to look at the health outcomes of patients — to explore whether limited network enrollees fared better, worse, or the same in the care of a smaller handful of providers.

Did you catch the magic trick that Gruber and McKnight—and the Vox writer summarizing their research—pulled off in this excerpt? Note the last sentence we put in bold: because they said they lacked precise enough data, the researchers didn’t actually take a stand on whether the Massachusetts employees who enrolled in the narrow plan did better or worse than their peers who had remained in the original plan. And yet, that was the whole point of the Vox article; remember, its title was, “Limited doctor choice plans don’t mean worse care.”

We can illustrate the enormous potential problem here with an analogy. Suppose the New York City branch of Goldman Sachs thought its executives were abusing their travel budgets. In order to weed out the frivolous flights, Goldman thus institutes a new policy: Any New York-based executive who agrees to only fly in and out of Reagan airport— located in Washington, DC—will get a $5,000 bonus. Executives who wish to retain the option of being reimbursed for their work flights using JFK or LaGuardia may continue to do so, but they forfeit the $5,000 bonus.

Now what would happen if we checked on the groups who did and did not take the bonus money a year after the new policy had been implemented at Goldman Sachs? We would presumably find that the executives who took the money ended up requesting much less in travel reimbursements. After all, if they wanted to fly somewhere for work, they would have to book the flights through DC, meaning they would need to take Amtrak or some other mode of transport down to that airport, rather than the much more convenient NYC-based airports. This is why executives opting for the restricted-choice air plan would end up making fewer trips to the airport than their peers who had not joined the (voluntary) Goldman program.

It is no surprise that our hypothetical restricted-airport plan could hold down travel expenses for the Goldman employees who opted to participate in the program. However, Goldman management would also want to know whether the program had any adverse effect on employee satisfaction and firm productivity. To this end, imagine that they hired outside researchers to conduct a study, asking them to quantify not merely the cost savings on travel expenses (which would be obvious) but also to gauge the downsides of the program.

The most obvious comparisons would look at the actual executives split into two groups: those who opted into the restricted-airport plan and those who didn’t, examining what their work performance was like before and after the program was implemented. If the group that opted into the plan saw a reduction in productivity relative to the control group (perhaps because they spent some of their time traveling to the DC airports, or because they opted for a conference call when a face-to-face meeting would have sealed the business deal), then Goldman could compare the savings on travel expenses with the reduction in employee output—thus determining whether, on net, the restricted-airport plan made financial sense for the company.

Ah, but what if the researchers said that they lacked the data to make such assessments? Rather than report on the outcomes of the actual Goldman employees involved with the new plan, instead the researchers looked at various metrics relating to the general users of the NYC versus DC airports. For example, the researchers reported statistics showing that flight delays, emergency landings and crashes, lost luggage, and so forth, were not significantly different when looking at passengers flying out of DC versus NYC airports. Armed with this research, the people at Goldman Sachs who had always been in favor of the new policy happily announced at the next meeting, “Limited airport-choice executive travel plans don’t mean worse air travel. We have hard evidence showing that our plan has saved the company hundreds of thousands of dollars without hurting the quality of accessible air travel for our employees.” Then these proponents of the plan make a move to mandate it for all executives, since the voluntary test-run showed that there were no quantifiable downsides to the program.

We hope our silly analogy helps illuminate the serious flaw in the Gruber/McKnight health care study: it is hardly consolation to know that one’s health insurance plan has a “good hospital” in network when that hospital is an extra 40 miles away. Nonetheless, pro-ACA media outlets trumpeted the study as showing limited-choice plans don’t hurt participants, when the authors themselves said quite explicitly that they had not been able to perform that measurement.

It is no coincidence that the biggest supporters of the ACA are preparing the public to accept restrictions on choosing their doctors and hospitals: this is our inevitable future. It is economically impossible to let Americans treat the health care sector as an all-you-can-eat buffet that comes with a flat and reasonable fee. That might work for (moderate quality) Chinese food, but not for state-of-the-art medicine. If Americans really want to follow the political promises of “free and universal” coverage, they necessarily will have shortages, bureaucracy, and rationing in their future.

AN ER DOCTOR REPORTS FROM THE FRONT LINES …

“One of the major quality improvements touted by ACA proponents is the decreased hospital readmission rates following implementation of new CMS [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] rules under the ACA. Beginning in 2013, CMS began denying payment to hospitals or physicians for any patient discharged from a hospital and then readmitted within 30 days. If a patient “bounced back” and required readmission, then CMS would not reimburse for any care administered during the readmission. The rationale was that this would encourage higher quality care during the initial hospital stay, which would therefore prevent the need for a repeat admission within 30 days. Driving this rule change was the assumption that before the ACA, patients only “bounced back” because doctors and hospitals had been cutting corners during the initial admission.

What this assumption ignores is that readmissions within 30 days can be a very necessary component of caring for sicker patients, particularly those with chronic diseases. For example, a COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] patient who gets admitted for pneumonia during flu season, and discharged when well enough that hospitalization offers no further benefit, still runs a very high risk of needing readmission within 30 days. The patient may continue to smoke. The disease is more active when such a patient has to use home heat, which dehumidifies the air, and the patient may come into contact with others carrying flu or other viruses. In summary, such a patient may bounce back for reasons that have nothing to do with the quality of care at the first visit.

Another consideration is that CMS incentives on the front-end of a hospital admission may actually drive decisions to discharge patients home prematurely. The DRG [diagnosis related group] system generates fixed payments that only cover a limited amount of time in the hospital. Hospital-based physicians are thus under intense pressure from their hospital administrators to discharge patients in a timely manner so the expenses of providing care do not exceed the fixed fee provided for the patient’s primary diagnosis. While it is doubtful that anyone is deliberately discharging patients home prematurely, when you consider the pressures exerted through CMS rules, then transmitted by hospital administrators down to those who provide the care (and whose jobs may be at risk if they push back), it is not hard to see that it does happen. I myself have not provided inpatient care since residency, but I cannot recall ever being able to treat and discharge a patient within the time frames that are expected today.

My actual experience is that the number of bounce-backs is not decreasing and may actually be increasing. The number of read-missions, however, is decreasing. Due to the financial pressures of this new ruling, hospitals are finding other venues of care for patients who return within 30 days of hospital discharge, legitimately needing readmission. Some of these patients are readmitted and the hospital and doctors just take the financial hit. However, many times an alternative disposition is found. For example, case managers may arrange for home health to visit and provide care at home. Other times, the patient may be directed to “short-term rehab” in a nursing home or assisted care facility. Another possibility is that a patient will be directed to hospice for comfort care. It is not uncommon for an elderly person with pneumonia to be discharged home and then return, having decompensated. Rather than being admitted for IV antibiotics and further care, the patient and family may be nudged toward hospice care and succumb from the illness. Some may argue for the appropriateness of this approach, but at times it can be a bit fuzzy.

What is disturbing is that ACA and CMS officials are touting the 30-day rule as an indicator for improved quality of care because statistics show that fewer patients are being readmitted. My personal experience is that decreased readmissions are just a response to economic incentives put in place by CMS, and that the number of bounce-backs has not decreased at all. My fear is that there may be some dead bodies hidden within those decreased readmission numbers. There could be people who could have been saved by a readmission but are instead dying at home, at a nursing home, or at hospice. I suspect it is happening but may never be discovered, and will be represented as a quality improvement when it is, in fact, a way of sweeping the new system’s failures under the rug.”

—Co-author Doug McGuff

We realize that our description of the country’s trajectory is alarming. However, we have not been throwing out idle speculation; we have explained the logic of our projections and backed our claims with examples and data. To further defend ourselves from charges of “paranoia,” in this final section of the chapter we will show that fans of the ACA are making similar forecasts.

The single best “smoking gun” for this issue is the first-hand testimony of Nevada Senator Harry Reid, one of the major forces behind the Affordable Care Act. In August 2013, Reid participated in a PBS show called Nevada Week in Review, in which the discussion turned to health care reform.20 The following (lightly edited for readability) excerpt of the interview between the Las Vegas Review-Journal’s Steve Sebelius and Reid is on the long side, but it confirms exactly what we have been warning:

SEBELIUS: … The system is better than it was when President Obama started his reform. But every problem that Mitch and Rick have identified, relate to the fact this was really health insurance reform not health care reform. If we had gone to a single payer system, none of these problems would have come up …

REID: My liberal friend, it’s nice of you to say that…. Don’t think we didn’t have a tremendous number of people who wanted a single-payer system…. Well, you have to get a majority of the votes, we weren’t able to do that….

SEBELIUS: … From what the public saw, the public option notwithstanding, there wasn’t even an attempt to get—

REID: Oh sure there was. Sure there was. We had a number of different iterations at health care…. We had a real good run at the public option. We thought we had of way of doing that. We couldn’t get it done …

SEBELIUS: Last question on this topic: Do you think that the health insurance model that started in World War II as a benefit when the wage-and-price controls were imposed, do you think that that is going to continue into the future, as the American model of health care delivery, or do you think eventually we’ll have—

REID: I think we have to work our way past that. Prior to World War II, there were no health benefits from your employer, it didn’t exist. Wage-and-price controls came into effect, and so the Big Three … got into fringe benefits: health care, vacation time, retirement time, all this kind of stuff. That’s where the model started, and we’ve never been able to work our way out of that. What we’ve done here with ObamaCare is a step in the right direction, but we’re far from having something that’s going to work.

SEBELIUS: So eventually though you think we’ll work beyond the insurance—?

REID: Yes, absolutely, yes.

Another bugaboo in the debate over the ACA is the notion of “death panels.” Conservative critics of the Obama Administration warned Americans that eventually bureaucrats would have the power to make life or death decisions. The pro-Obama pundits rolled their eyes at the “paranoid” rantings of Sarah Palin and the like.

Our purpose here is not to defend every specific complaint that any person on FOX ever launched against the ACA. Yet consider the following excerpt from a public talk that Paul Krugman gave in February of 2013. After fielding a question about whether a particular level of government debt would lead to a crisis, in the course of his answer Krugman said:

There is this question, how are we going to pay for the programs? In the year 2025, 2030, something is going to have to give, right?… Surely it will require some middle class taxes as well, so we won’t be able to pay for the kind of government as a society we want, without some increases in taxes—not a huge one—but some increases in taxes on the middle class taxes, maybe a Value Added Tax. And we’re also going to have to do, really, make decisions about health care, and not pay for health care that has no demonstrated medical benefits. And so, you know, the snarky version I use—which I shouldn’t even say because it will get me in trouble—is death panels and sales taxes is how we do this. But it’s not that hard.22

Now to be sure, Krugman was “just joking” with his use of the term “death panel,” but as they say: it’s funny because it’s true! If Krugman had been discussing, say, government funding for new schools or a mission to Mars, then labeling it “death panels” wouldn’t have made any sense. But because Krugman was talking about the government ultimately protecting its financial position by refusing to pay for health care that “has no demonstrated medical benefits,” that’s why the “death panel” joke worked. If everyone’s health care is paid for by everyone else as a taxpayer, then it won’t suffice to let individuals choose to run up huge medical bills in the last year of life.

IF HISTORY IS OUR GUIDE …

If all of our talk still sounds paranoid, we can also look to the past to see precedents for what happens when the government has power over someone’s treatment. Those with a strong stomach are encouraged to Google the 1946 Life magazine article by Albert Maisel titled, “Bedlam 1946.”22 The piece was a shocking exposé on the horrid condition of many state-run psychiatric hospitals. The anecdotes and grisly photos reveal what can happen even here in America.

For a recent example of the dangers of government health care, we can look at the unfolding scandal with the abysmal treatment and subsequent cover-ups in Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospitals. On April 30, 2014, CNN relied on whistleblowers in a report that at least 40 veterans had died while waiting for care at the Phoenix VHA facilities. By June 5, 2014, VA internal investigations confirmed that at least 35 veterans in the Phoenix area had indeed died while awaiting treatment.23 A broader investigation began, implicating more VHA hospitals around the country, while the VHA’s top health official, Dr. Robert Petzel, as well as the Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric Shinseki, eventually both resigned. The ultimate fallout from the VA scandal is not yet clear, but what is certain is that the dangers in government health management are still very real.