CHAPTER 8

Towers and Spires

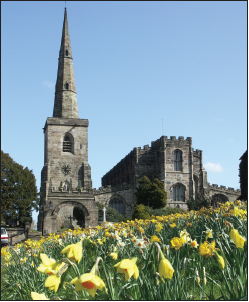

Towers and Spires

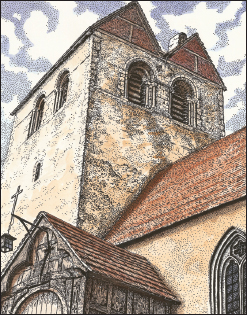

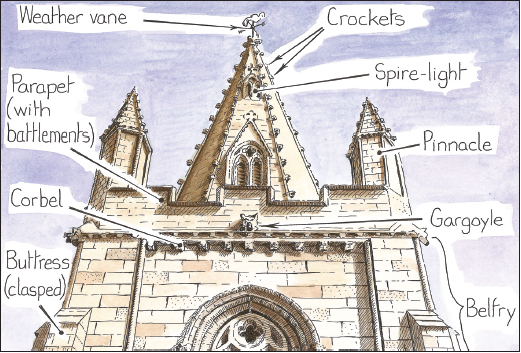

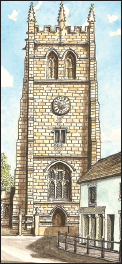

FIG 8.1: A drawing of a tower, with a parapet spire and labels of some of the key features.

The crowning glory of most parish churches is its tower or spire. It is a beacon visible from miles around which seemingly pins the village or town into the landscape. Yet it is the one part of the building which serves no ceremonial or liturgical purpose, its only role was to hold the bells and this had been done previously in freestanding wooden frames in the churchyard, making the tower really just an architectural luxury.

It was often the case that a village or wealthy individual tried to outdo their neighbour by adding a taller or more elaborate tower, this competition along with the properties of local materials and the limited area in which the masons worked helped create their distinct regionalization. The tall elaborate towers of Somerset and the spires of the East Midlands are just a couple of examples of these vernacular forms, a neat pattern which the Victorians displaced by importing their favourite types into virtually every area!

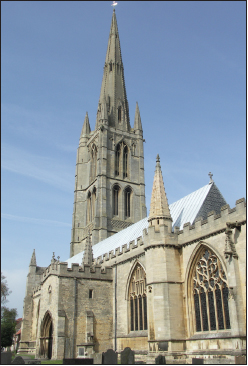

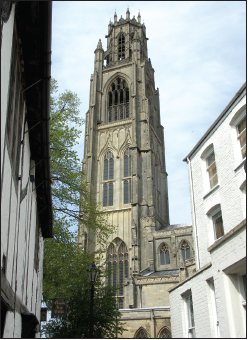

FIG 8.2 BOSTON, LINCS: Although a tower’s principal purpose was to hold the bells, with the occasional use as a strong-room, refuge or beacon, the main motive was probably pride. The tallest medieval tower in England, the 288 ft Boston Stump, pictured here, may have been a feature useful to shipping coming into this busy port but it is more a demonstration of the wealth which this trade created for the town.

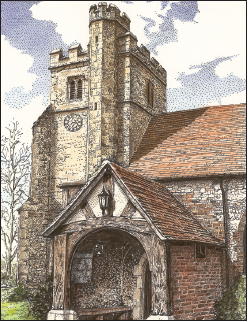

Despite this, 19th-century architects should be credited with saving many towers. As much as we can rightly marvel at the medieval builder who erected huge structures with simple tools, wooden scaffolding and experience rather than science, many did fall down, usually through poor foundation or later neglect (see Fig 4.14). What you see today might be an ambitious project which ran out of money and was capped off, a short tower which was heightened later or one which was in such a poor state that it was rebuilt, with only a lower portion surviving from its previous incarnation.

FIG 8.3 BYLAUGH, NORFOLK: The most regional distinctive types of tower are the round ones of East Anglia. Most of the hundred or so which stand were built in the Saxon or Norman period, possibly with defence from raiders in mind. They may have served as a look out and had a ladder to get villagers in if under attack. On the other hand the lack of good building stone in the area made this form with no corners a more practical shape to build. This example has a 14th-century octagonal belfry section.

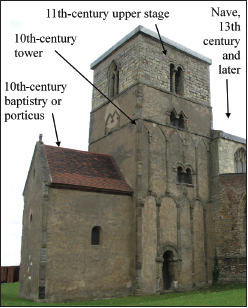

FIG 8.4 BARTON-UPON-HUMBER, LINCS: This notable Saxon tower dates from the late 10th century with similar triangular and round arched openings with vertical strips to Earls Barton (see Fig 1.20). When built the square base of the tower acted as the nave, with the small room to the left in this picture possibly used for baptisms and a similar one to the right being the chancel. This latter part was rebuilt around the time of the Norman Conquest and the tower heightened (the different masonry in the top section), then later still the present nave and chancel developed.

Early Towers

Towers were rare on parish churches before the 13th century and those which were built indicate that the building was a minster or in an important centre (Barton-upon-Humber in Fig 8.4, for instance, was a major port at the time). Some were narrow in form (see Fig 8.5), others broad when they were possibly used as a nave (see Fig 8.4 and 8.6).

FIG 8.5: A distinctive narrow tower (left) from a 7th-century monastic church at Monkwearmouth (upper parts are later Saxon) and one dating from the 11th century from Marton, Lincs (right). Note the top of a blocked door on the latter just above the roof of the nave, a distinctive feature of Saxon towers, which was originally inside the nave – you can see the old roof line above it.

FIG 8.6 FINGEST, BUCKS: A large Norman tower with its distinctive belfry openings and bulky form, which dominates this tiny hamlet. It may have served as the nave on the original church as at Barton (Fig 8.4) though in similar towers the room at the bottom might have been used for accommodation for the priest. Above is a twin saddleback roof, a common late 17th- and early 18th-century method of covering large spaces. Originally it probably had a low pyramidal roof.

The Normans built towers of similar form but with larger openings or erected central towers (with or without transepts) capped off by a low pyramidal roof (usually later replaced). The latter had the advantage that an elaborate west front and windows could be added, making a grand ceremonial entrance. These were probably built by a select few masons or churchmen and hence are similar in style, with little regional variation at this stage. They could also take a long time to build so the decoration could change the further up it reached.

FIG 8.7 KEMPLEY, GLOS: A distinctive squat, plain Norman tower with a low pyramidal roof (details like the buttresses are later). Many 12th-century towers and some later had corbel shelves around the top (see Fig 1.13).

Spires: Early English and Decorated

In the 13th and early 14th centuries the spire was the must-have addition for churches with a wealthy benefactor. Nobody knows its exact origins but it probably evolved by raising the pitch of the pyramidal roofs used on Norman towers as it better suited the new narrow lancet windows.

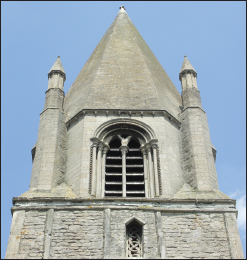

FIG 8.8 BARNACK, CAMBS: This 13th-century rather squat spire is possibly the earliest surviving one in the country. It stands on top of a Saxon structure (note the rough masonry and vertical strips) and has pinnacles in the corners covering the junction between the octagonal bell stage and square tower.

At the same time it was realized that an octagonal form was more appropriate for a spire, leaving a gap in each corner where it met the square top of the tower. Some of the earliest from the 13th century around Oxford resolved this by building pinnacles over these corners, but in the East Midlands small sloping triangular pieces called broaches were used, hence making the distinctive broach spire. It was also appreciated that ventilation was important to prevent damp so decorative openings shaped as windows with a triangular gable called spirelights were fitted, early ones tending to be large, subsequent ones smaller.

FIG 8.9 KIRBY BELLARS, LEICS: A broach spire and tower dating from the late 13th and 14th centuries. The style and size of the spire lights can help date the structure.

FIG 8.10 TREBETHERICK, CORNWALL: This rather weather-worn broach spire dating from the 13th century slightly leans towards the top. This distortion and twisting is more common on lead-covered timber spires, as famously at Chesterfield, Derbys, which was probably caused by constant heating and cooling or unseasoned timber.

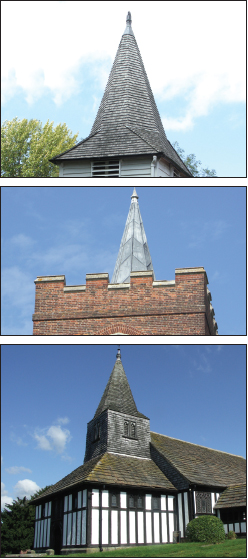

FIG 8.11: A splay footed wooden-shingle covered spire from Greensted, Essex (top), popular in the south where suitable stone was limited. Spikes are a distinctive feature of Essex, as with this example from Stansted Mountfitchet (centre). Some towers had a lean-to aisle wrapped around to cover part of the supporting timber work as here at Marton, Cheshire (bottom).

Later in the period, spires become taller often with decorative bands or crockets (small projecting leaf-like spurs) up the vertical angles. The most notable change was the addition of a parapet around the top of the tower, with gargoyles helping to drain the water off and the spire set behind and hence appearing finer. This had the advantage that ladders could be set on the tower making construction and maintenance easier.

FIG 8.12 ASTBURY, CHESHIRE: A 14th-century parapet spire with a distinctive needle-like appearance. The parapets here are plain, but most would have had battlements. This is also an example of a detached tower, which is often due to poor foundations at the west end of the nave where most towers are sited.

FIG 8.13 GRANTHAM, LINCS: One of the finest English church spires from the 14th century, with crockets down the corners (these form steps for steeplejacks). The optical effect of vertical features like columns appearing to bulge in the middle was countered in some spires by enlarging the crockets in the centre section (called entasis).

Perpendicular Towers

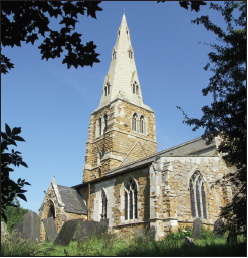

In the late 14th century spires began to fall from fashion partly as the new Perpendicular style with broader, flatter arches and roofs better suited a squared-off tower rather than a fine point. Up until the Reformation thousands of new towers were built, some upon existing churches where there had been none or replacing an earlier central type, others as part of new ambitious projects. Most were taller than before with thinner but more prominent stepped buttresses in the corners and larger belfry openings in the style of the latest window tracery. The tops usually featured battlements or a parapet with decorative cut outs, often with pinnacles in the corners.

FIG 8.14: The finest collection of Perpendicular towers is in Somerset, an area which grew rich at the time through the wool trade with individuals ploughing their personal wealth into these soaring spectacles. These examples from Backwell (left) and Winscombe (right) have the distinctive large belfry openings, elaborate parapets and pinnacles, and prominent buttresses (stepped back at Backwell and on the angle at Winscombe).

FIG 8.15 YOULGREAVE, DERBYS: Large Perpendicular towers are instantly recognizable by their height, prominent stepped buttresses, and large belfry openings with contemporary tracery. They also tend to have pinnacles and battlements around the top.

FIG 8.16 GEDNEY, LINCS: An example of a tower heightened in the Perpendicular period. The Early English structure below (note the original blocked belfry openings and the flat buttresses with columns up the corners) had an upper stage added with distinctive ogee arches and belfry tracery. The top appears blunt because a spire was planned but never completed and a small lead-covered spirelet stands in its place today.

FIG 8.17 LITTLE MISSENDEN, BUCKS: More humble Perpendicular towers are still distinguished by prominent buttresses, battlements and square-headed, cusped belfry openings. This example has a prominent stair turret, a feature popular in certain regions. Other staircases were hidden in corners or buttresses; just look for a series of narrow windows to see where they are.

Later Towers and Spires

This great age of tower building came to an end with the Reformation, the great sums of money required for these symbols of local pride now being directed into private projects. Those which were built were increasingly made from brick, at first in the south and eastern counties but spreading out into the Midlands during the 17th century. After the Restoration in 1660 they began to reflect the new Classical styles, most notably on Wren’s London churches (see Fig 4.3), although most were less ambitious with round arched belfry openings and a cupola or similar feature on the roof.

The Victorian love of the Gothic meant a return of the spire and it became a prominent feature once again on the skyline of towns and cities. They were, however, generally copies of medieval types (see Fig 2.4) with little new invention. It was only later in the period and into the 20th century when squat Norman and tall Perpendicular towers were the inspiration, that new types appeared with simplified bold features. On those many churches built in this period for smaller communities, a bellcote had to suffice; a simple gabled top with a couple of openings housing the bells (see Fig 5.5).

FIG 8.18 BANGOR-IS-Y-COED, NR WREXHAM: Georgian towers are distinguished by the use of Classical details upon a largely plain un-buttressed body. They also have round arched and circular openings and features like urns and cupolas on the top.

FIG 8.19 FOSDYKE, LINCS: A distinctive Victorian redbrick church with a tower capped off by a lead-covered spire. This material had been used on similar timber structures for centuries but copper, which turns green on exposure, was only used from the 18th century.

Bells

The only practical reason behind the building of a tower was to house bells and more than 5,000 have a ring of five or more (usually only in the Church of England), sounding out a summons to services as well as alarms, celebration or tragedy. The oldest which can be accurately dated are from the 13th century, these medieval types tending to be narrower than later ones and they are often inscribed with prayers. Most bells will date from after the Reformation, with inscriptions in English and the foundry’s name upon them. The distinctive change ringing, when bells are rung one after another but with the order changing each time, was only introduced in the mid-17th century and is unique to this country.

FIG 8.20 HEDSOR, BUCKS: Many churches in the 19th century had a simple bellcote added or a small bell turret as here on this late medieval flint and brick church.

FIG 8.21: Text on the upper band of a bell recording the date and, in the small box, that ‘Henry Neale made mee’.

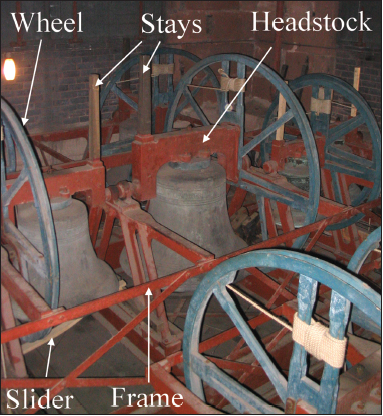

The ringing starts with the bells in an upright position. As the rope attached to the wheel at the side of each bell is released their momentum enables them to complete a roughly 300° turn, which is stopped by stays fixed to the headstock hitting a slider below. As it swings, the clapper inside hits the sound bow (the thick metal rim at the mouth of the bell), the tone of the ring depending on the size and form of the bell.

FIG 8.22: A ring of bells with wheels set in a modern metal frame.

Clocks

Although the congregation could be summoned by bells, the time for services could also be calculated by small scratch sundials upon the south side of the church (see Fig 6.10). Clocks did not appear on village churches until the 17th century with most dating to later. These early clocks could be most elaborate, with colourfully-decorated figures ringing bells or with elaborately projecting faces.

Weather Vanes

Telling the direction of the wind was important in a country which was dominated by agricultural concerns. The weather vane on top of the church tower has been a feature even included on the Bayeaux Tapestry and subjects on them include the cock, which symbolized vigilance, as well as dragons and fish.