Ten

Soft Is Hard

May we recommend

‘Does Television Rot Your Brain? New Evidence from the Coleman Study’

by Matthew Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro (National Bureau of Economic Research paper, 2006)

Some of what’s in this chapter: His proud ‘simplistic view of corruption’ • Narcissism writ big • Dietrich’s doll fetish • The further, two-dimensional, adventures of Jesus • A market for stock metaphors • Baggagial emotion • Oboe danger • The Thatcher cut-off • No yes • A scarcity of bad singers • Nervousness detector • Filthy words from the distaff side • Personality of veg • Benefits of randomness • Double-entry Australadventures • An exacting approach to vagueness • Do not mention the wolves • Wedding rings are wearing • Your discoveries

The economist who theorized on corruption

Steven Ng-Sheong Cheung, because of his adventure with the legal system – not despite it – sets a high standard for economists. The economics profession is often accused of concocting clever theories that don’t resonate in the lives of real people. Cheung devised a theory about man’s struggle with corruption and governments. He wrote about his theory, with relish. The US government shone a spotlight on Professor Cheung’s thoughts when it issued a warrant for his arrest.

Back in 1996, Cheung – who was then head of the University of Hong Kong’s School of Economics and Finance, and an economist at the University of Washington in Seattle – published ‘A Simplistic General Equilibrium Theory of Corruption’ in the journal Contemporary Economic Policy. The very first sentence of that paper says: ‘The author’s simplistic view of corruption is that all politicians and government officials – like everyone else – are constrained self-maximizers. They therefore establish or maintain regulations and controls with the intent to facilitate corruption, which then becomes a source of income for them.’

Cheung dives deep into the matter. A few pages later he explains: ‘I made the now famous statement that it is no use to put a beautiful woman in my bedroom, naked, and ask me not to be aroused. I said that the only effective way of getting rid of corruption is to get rid of the controls and regulations that give rise to corruption opportunities.’

A press release issued on 25 February 2003 by the Seattle office of the US Department of Justice bears the headline: ‘ARREST WARRANTS ISSUED FOR ECONOMIST AND WIFE FOR THEIR FAILURE TO APPEAR’ (in all uppercase letters). That press release reported: ‘A federal grand jury returned an indictment against the CHEUNGs on January 28, 2003. STEVEN N.S. CHEUNG was named in all thirteen counts of the indictment, charging him with Conspiracy to Defraud the United States, six counts of filing false income tax returns, and six counts of filing false foreign bank account reports.’

Previously, an investigative team at the Seattle Times newspaper had alleged that Cheung was linked to an art gallery that sold fake antiques.

In 2004, Steven N.S. Cheung Inc., the corporation in front of the man behind the corporation, sued the US government for ‘recovery of wrongful levy’ of $1,434,573.76 in taxes. Cheung’s company won, but then lost a court appeal over how much money was involved.

Professor Cheung retired to China, where he became a newspaper columnist and blogger (blog.sina.com.cn/zhangwuchang), joining a profession that enjoys almost as much public confidence and respect as his former one.

Cheung, Steven Ng-Sheong (1996). ‘A Simplistic General Equilibrium Theory of Corruption’. Contemporary Economic Policy 14 (3): 1–5.

US Department of Justice (2003). ‘Arrest Warrants Issued for Economist and Wife for Their Failure to Appear’. Press release, Seattle, 25 February, http://www.justice.gov/tax/usaopress/2003/txdv03cheung.html.

US Department of Justice (2003). ‘Eminent Economist and Wife Indicted on Tax Charges’. Press release, 28 January, Seattle, http://www.justice.gov/tax/usaopress/2003/txdv03cheung012803.html.

Wilson, Duff (2003). ‘Economist Tied to Fake Art Faces Tax Charges’. Seattle Times, 29 January, http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=20030129&slug=cheung29.

US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (2008). Steven N.S. Cheung Inc v. United States of America, no. 07-35161, Seattle, 23 September.

In brief

‘Narcissism is a Bad Sign: CEO Signature Size, Investment, and Performance’

by Charles Ham, Nicholas Seybert and Sean Wang (UNC Kenan-Flagler research paper, 2013)

The authors explain: ‘Using the size of the CEO signature on annual SEC filings to measure CEO narcissism, we find that narcissism is positively associated with several measures of firm overinvestment, yet lower patent count and patent citation frequency. Abnormally high investment by narcissists predicts lower future revenues and lower sales growth. Narcissistic CEOs also deliver worse current performance as measured by return on assets, particularly for firms in early life-cycle stages and with uncertain operating environments, where a CEO’s decisions are most likely to impact the firm’s future value. Despite these negative performance indicators, more narcissistic CEOs enjoy higher compensation, both unconditionally and relative to the next highest paid executive at their firm.’

Samples: CEO signatures taken from annual reports

The fetishized Dietrich’s doll fetish

‘The study of Marlene Dietrich’s relationship with her dolls has taken me into some new research territory.’ With these words, Judith Mayne, the Distinguished Humanities Professor of French Studies and Italian Studies and Women’s Studies at Ohio State University, takes many of us into some new territory. Her recent study ‘Marlene, Dolls, and Fetishism’, published in the journal Signs, is an introductory guidebook to this intriguing land.

Scholars of the German film star Marlene Dietrich have debated many of the contradictions in her screen roles and in her life. Professor Mayne singles out a contradiction the other scholars have apparently failed to appreciate: ‘The particular contradiction that I find the most challenging in relationship to Dietrich is that this icon of sophistication and glamour was the proud owner of a black doll, which she called her “mascot” and carried with her everywhere during her career.’

The chief source of information about the doll is a memoir that Dietrich’s daughter, Maria, published in 1992. Drawing from that memoir, Mayne describes the central role that the doll had in Dietrich’s life:

‘Marlene came home in a fury one day, desperately digging through trunks and accusing little Maria of having stolen her doll. Maria knew that her father, Rudolf Sieber, had been fixing the grass skirt of the doll; the father is thus identified as both maternal and as the devoted handmaiden to his wife’s desires. Daughter Maria concluded that the doll was Dietrich’s ‘good-luck charm throughout her life – her professional one’.

Mayne reports that this was not the only doll that Dietrich owned, and that this doll was not a strictly private object. ‘Indeed, attentive viewers might well recognize the doll from Dietrich’s films as well as from publicity postcards of the actress, often in the company of yet another one of Dietrich’s dolls, a so-called Chinese coolie doll, made by Lenci.’ Mayne concentrates her analytical powers on the black doll, dismissing the Chinese coolie doll as likely just ‘a companion’ to the other, and paying the other dolls scarcely a mention.

The black doll appeared in at least four of Dietrich’s films, including the one that made her famous: The Blue Angel. Mayne concentrates on that film. In so doing, she gives us her highly original – and, I must say, challenging – take on Dietrich, dolls and fetishism.

‘It is perhaps easy (too easy) to see the doll in The Blue Angel as a classic fetish’, Mayne writes. ‘Fetishism, understood now more as the ambivalence of the ironist than the dread of the phallocrat, is, if not celebrated, then at the very least explored as offering an understanding of multiple identifications and positions … [But] the racial dynamics of Dietrich’s relationship with her dolls foreclose any simple celebration of fetishism as necessarily subversive.’

Mayne, Judith (2004). ‘Marlene, Dolls, and Fetishism’. Signs 30 (1): 1257–63.

In brief

‘The Organization of Santa: Fetishism, Ambivalence and Narcissism’

by Robert Cluley (published in Organization, 2011)

Jesus, fleshed out

The Tring tiles add spice, and maybe a little sugar, to the question, ‘What would Jesus do?’ These adventure-packed ceramic cartoons depict scenes, unmentioned in the bible, from Jesus’s boyhood, and appear to be based on the Apocryphal Infancy of Christ Gospels, ‘which purport to tell events from Jesus’ life, from ages 5 – 12’. Apparently created in the fourteenth century, they once enlivened a wall of the parish church in the town of Tring, though, according to some accounts, ‘the Infancy stories were so startling that Church Fathers condemned them as unsuitable for inclusion in the canon’.

Several of the tiles now reside under glass, in Case 15 of Room 40 of the British Museum in London. Every year, almost all of the museum’s five million or so visitors pass them by, unaware of the potent lessons that the tiles offer.

The spare New Testament description of Jesus gets some fleshing out. The museum has provided labels that help the visitor make sense of the action. (The museum changes the labels now and again; the descriptions below are the wording as it appeared when I first encountered the tiles.)

We see young Jesus learning how to play with others, and how not to. The accompanying label explained: ‘Jesus plays by the side of the river Jordan making pools; a boy destroys one with a stick and falls dead.’ Then, ‘The Virgin admonishes Jesus, who restores the boy to life by touching him with his foot.’

We see that Jesus the boy is rambunctiously playful: ‘A schoolmaster is seated on the left. Before him stands Jesus, a boy leaping on to his back in attack. The boy falls dead.’ Then ‘Two women complain to Joseph on the left, while Jesus restores the boy to life.’

As with all artwork, religious or otherwise, these images invite further, and perhaps different, interpretations. As the boy is falling dead, the schoolmaster and Jesus rather appear to be smiling and giving each other what is now known as a ‘high five’. The two women who complain about the death do so with what would, in other circumstances, be taken as smug smiles.

Where the museum labels’ author observed that Jesus revives the other boy – the one who mucked with Jesus’s pools by the river Jordan – ‘by touching him with his foot’, some may think they see a kick being administered.

A few of the cartoon sequences are incomplete. For these, the museum’s captions shared what happens in the missing tiles.

We see the curiosity-driven Jesus learn, in fits and starts, some fine points about how to teach people a lesson: ‘Parents, to prevent their children playing with Jesus, have shut them in an oven; Jesus, asking what that oven contains, is told “Pigs”. (The remainder of the story, showing the children transformed into pigs and their subsequent cure by Jesus, is missing.)’

We see how, as word about the boy Jesus spreads, neighbours sometimes leap to unkind assumptions about the lad: ‘A father locks his boy up in a tower to stop him playing with Jesus.’ Then ‘Jesus helps the boy out of the tower. (The remainder of this story, showing the father struck blind on his return, is missing.)’

The Tring tiles presumably will continue their residence in the British Museum. There are no announced plans to reproduce them for contemplative use in churches, offices or the home.

Bagley, Ayers (1985). ‘Jesus at School’. Journal of Psychohistory 13 (1): 13–31.

Casey, Mary F. (2007). ‘The Fourteenth-century Tring Tiles: A Fresh Look at Their Origins and the Hebraic Aspects of the Child Jesus’ Actions’. Peregrinations 2 (2): n.p., http://peregrinations.kenyon.edu/vol2-2/current.html.

May we recommend

‘Jesus and the Ideal of the Manly Man in New Zealand after World War One’

by Geoffrey M. Troughton (published in Journal of Religious History, 2006)

The dead cat bounce

In struggling to make sense of the stock market, people reach and stretch for metaphors. Sometimes they even contort, dislocate and mangle. In 1995, Geoff P. Smith of the University of Hong Kong made a grand unified effort to gather and classify those metaphors.

Smith congealed the metaphors and his thoughts into a monograph called ‘How High Can a Dead Cat Bounce?: Metaphor and the Hong Kong Stock Market’. It appeared in the journal Hong Kong Papers in Linguistics and Language Teaching.

Detail: ‘Resident Fauna’ of ‘How High Can a Dead Cat Bounce?’

Smith collected mostly from three sources: the South China Morning Post’s business supplement, the Asian Wall Street Journal and the Asia Business News television programme.

Here are verbatim snippets, which I present in the form of a mixed-metaphor story. It begins, of course, with two favourite animals.

- Strong bears came out of the woods determined to drag the market down.

- The bears had their claws firmly dug in and were not letting go.

- Optimists saw the makings of a baby bull, but naysayers warned it could be a bum steer … after last year’s grizzly bear market.

- Speculators played a cat and mouse game with stocks.

- The stock remained a dog.

- Investors [ran] like a herd of startled gazelles.

- The market was very nervous.

- The market was having trouble focusing on issues.

- Sick dollar … groggy dollar … dollar cringes.

- The market was suffering vertigo.

- The market started to drift and lose direction.

- [The market] precariously balanced on the 10,050 mark.

- The index hovered.

- [The market was] losing its footing.

- The index fell off the cliff.

- The Hang Seng Index dropped like a brick. [This one’s a simile. I know, I know.]

- [The] index continued its tailspin.

- The market seemed to have come out of its free fall.

- Stock prices took a roller coast ride and ended up in the subway.

- The bounce was more technical than substantial.

- Those hoping for a big rebound to catapult it out of this bear trap would probably be disappointed.

- The question every trader will be asking himself this week is: just how high can a dead cat bounce?

Surveying the hotchpotch of stock phrases and market-driving hype, Smith sighs: ‘Rarely do commentators say “These events are totally unpredictable; I haven’t the slightest idea what caused them to occur.” ’

The possibility flaunts itself that no one quite understands what the stock market’s doing. If that’s the case, everyone’s unlikely to come up with metaphors that truly fit. But that won’t stop them from trying. Smith tells us why at the end of his report: ‘A group with a significant stake in the maintenance of an impression of certainty are the financial “gurus” whose words and actions can have profound effects on the way markets move … To a lesser extent, a host of commentators, analysts and advisers benefit from the illusion that market events are controlled and rational and can be explained and predicted.’

Smith, Geoff P. (1995). ‘How High Can a Dead Cat Bounce?: Metaphor and the Hong Kong Stock Market’. Hong Kong Papers in Linguistics and Language Teaching 18: 43–57.

In brief

‘On What I Do Not Understand (and Have Something to Say), Part I’

by Saharon Shelah (published in Fundamenta Mathematicae, 2000)

An academic view on emotional baggage

Until 1997, lost luggage just sat there, ignored, while scholars focused on other subjects. Then Klaus R. Scherer and Grazia Ceschi of the University of Geneva went to an airport and took a hard look at the emotions engendered by luggage loss.

Scherer and Ceschi used hidden cameras, microphones and survey forms to record people’s reactions to learning that their luggage was lost. Their report, called ‘Lost Luggage: A Field Study of Emotion–Antecedent Appraisal’, published in the journal Motivation and Emotion, concerns 112 luggage-deprived passengers. It looks at several questions.

QUESTION ONE: When airline passengers discover that their baggage is lost, which emotions do they feel, and with what intensity?

The researchers focused on five basic emotions: anger, resignation, indifference worry and good humour. They tried to measure the intensity of each of these twice – first before and then after the passengers spoke with an airport baggage agent. The study presents the data in a series of tables and graphs, which culminate in an image labelled ‘Component loadings in a three-dimensional solution produced by nonlinear canonical correlation of appraisal dimensions and emotion ratings’.

QUESTION TWO: Can the emotional reactions reported by these airline passengers help prove or disprove one of the fundamental tenets of a theory called ‘Appraisal Theory’?

Specifically, Scherer and Ceschi want to know what these luggage-loss emotions can tell us about ‘the notion that objectively similar events or situations will elicit dissimilar patterns of emotional reactions in different individuals, due to variable appraisal patterns’. It’s a subtle question, but Scherer and Ceschi find a simple, clear answer. Appraisal Theory, they conclude, is not yet up to snuff. It will need some tinkering before it can adequately explain how airline passengers react after learning that their luggage has gone missing.

QUESTION THREE: Once a baggage agent enters the picture, how does he or she affect the passenger’s luggage-loss-related emotions?

This is the question they ask, and it may be an important question, but Scherer and Ceschi are really after something deeper. What they really want to know, they say, is what happens in the end. What emotion will passengers feel after they have (a) lost their luggage, and then (b) talked with an airport baggage agent, and then (c) decided how well (or how badly) the whole baggage retrieval service worked?

The answer, say Scherer and Ceschi, is that people ‘tended to be less angry and/or sad if they were satisfied with the performance of the retrieval service’, or if the airport baggage agent made ‘a positive impression’ on them.

The researchers were surprised by the strong extent of what they call ‘emotion blending’. The unfortunate passengers often felt more than pure anger or resignation or worry. Sometimes they felt both anger and resignation, or both anger and worry.

Scherer and Ceschi welcome such unexpected discoveries. And so they offer a suggestion for their fellow social scientists. Actually seeing how people behave, they write, can ‘widen the perspective’. It’s a ‘corrective against the self-insulation tendencies’ of relying too much on theories about how people behave.

Scherer, Klaus R., and Grazia Ceschi (1997). ‘Lost Luggage: A Field Study of Emotion–Antecedent Appraisal’. Motivation and Emotion 21 (3): 211–35.

— (2000). ‘Criteria for Emotion Recognition from Verbal and Nonverbal Expression: Studying Baggage Loss in the Airport’. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26 (3): 327–39.

Oboe, solo

‘Dangerous Trends in Oboe Playing’ burst into print in 1973, a fiery warning for all to see.

Melvin Berman, then a professor of oboe and chamber music at the University of Toronto, daringly discussed – openly, in public – a problem that threatened his tradition-bound minority community. Publishing in the Journal of the International Double Reed Society, he wrote: ‘The American oboist is being branded as an in-bred, dull and insensitive technician by most of the world’s orchestral musicians and many of the world’s finest conductors … Something is desperately wrong and everyone, except the oboists, knows what it is. Now, I think it’s time for the oboists to find out.’

This was the roiling societal ferment of the 1960s, at last and after a delay of several years reaching into even the tiniest and most isolated of social groups. It was also a cri de coeur: ‘We have forgotten, or refuse to accept the fact that there are other schools of playing, other approaches to the oboe, other methods of making reeds, which deserve and have at least as wide an acceptance as our own … We are taught to laugh at the English vibrato, smirk at the German sound, ridicule the French brightness.’ The solution, insisted Professor Berman, was ‘to liberate ourselves from the restrictive attitudes imposed upon us by certain elements of the past generation’.

The Berman article appeared at a peculiar moment. The oboe community had just been confronted and transfixed by a challenge to its deepest values. This, of course, was the appearance of the Italian composer Luciano Berio’s Sequenza VII, a piece written for solo oboe. So novel was it that two decades passed before a scholar, Cason A. Duke of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, described it coherently: ‘a single note held as a drone by the audience throughout the piece’. (Berio later reworked the composition as Sequenza VIIb for soprano saxophone.)

The oboists were not unique in feeling isolated. That same issue of the Journal of the International Double Reed Society also contained a revealing study by the Austrian bassoonist Hugo Burghauser. He described the loneliness of bassoonists, and also the physically painful reality of their existence.

Burghauser’s writing is intensely personal: ‘I was often asked why I chose to play the bassoon. The answer is simple and might be the same for many other bassoonists: in my youth, students for this instrument were very scarce so when I wanted to enter the Vienna Conservatory the Dean of this prominent Academie offered me every course free of all tuition if only I would take up the bassoon.’

Burghauser – and his fellows’ – pain shines through in passages such as this one: ‘Many years ago also, there was the experience in Europe of manufacturing reeds from steel. They sounded beautiful, spoke easily and lasted of course for a very long time, with but one hitch – after five minutes playing a splitting headache resulted!’

Berman, Melvin (1973). ‘Dangerous Trends in Oboe Playing’. Journal of the International Double Reed Society 1 (1): n.p.

Burghauser, Hugo (1973). ‘Philharmonic Adventures with Bassoon’. Journal of the International Double Reed Society 1 (1): n.p.

Berman, Melvin (1988). Art of Oboe Reed Making. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Duke, Cason A. (2001). ‘A Performer’s Guide to Theatrical Elements in Selected Trombone Literature’. Thesis, School of Music, Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, May.

Thatcher, interrupted

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher‘s masterful way of handling interruptions inspired one psychologist to study, intently, how she did it. As this scholar communicated his findings to the public, other scholars, with different views, interrupted him – and he them.

Geoffrey Beattie is a professorial research fellow of the Sustainable Consumption Institute at the University of Manchester. Or rather, was – the 12 November 2012 issue of the Manchester Evening News quotes ‘a university spokesman’ as saying: ‘We can confirm Geoff Beattie has been dismissed from the university for gross misconduct following a disciplinary hearing.’ In 1982, however, while he was at the University of Sheffield, Beattie published two studies about Thatcher.

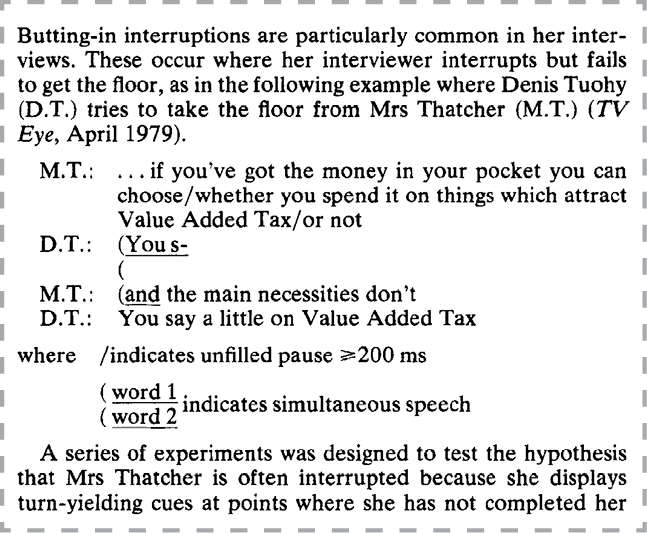

The first, in the journal Semiotica, says: ‘Mrs Thatcher’s interviews display a distinctive pattern – she is typically interrupted more frequently than other senior politicians, and she is interrupted more often by interviewers than she herself interrupts … Butting-in interruptions … occur where her interviewer interrupts but fails to get the floor.’

From ‘Why Is Mrs Thatcher Interrupted So Often?’

The second study, called ‘Why Is Mrs Thatcher Interrupted So Often?’, appears in the journal Nature. Beattie (and two colleagues) analysed how Thatcher deployed her voice, words and gaze when Denis Tuohy interviewed her on the television programme TV Eye. The study explains that most people use fairly standard cues with each other, as to when each will stop or start talking. But, it explains: ‘Many interruptions in an interview with Mrs Margaret Thatcher, the British prime minister, occur at points where independent judges agree that her turn appears to have finished. It is suggested that she is unconsciously displaying turn-yielding cues at certain inappropriate points.’

Peter Bull and Kate Mayer of the University of York disagreed. They and Beattie argued, slowly, in public, mostly in the pages of the Journal of Language and Social Psychology. In 1988, Bull and Mayer wrote a treatise called ‘Interruptions in Political Interviews: A Study of Margaret Thatcher and Neil Kinnock’, saying their ‘results were quite contrary to what might have been expected from the work of Beattie’. Beattie replied with ‘Interruptions in Political Interviews: A Reply to Bull and Mayer’.

Then, a year later, Bull and Mayer countered with ‘Interruptions in Political Interviews: A Reply to Beattie’. And Beattie responded with ‘Interruptions in Political Interviews: The Debate Ends?’.

Bull and Mayer, four years later, published a study called ‘How Not to Answer Questions in Political Interviews’. After that, the conversation dwindled.

But Beattie did not shy away from studying interruptive behaviour. He wrote a book called On The Ropes: Boxing as a Way of Life. A reviewer, in the journal Aggressive Behavior, contended that the book is a knuckle-cracking good read, that it ‘takes you into a world where respect has nothing to do with your publication record or letters after your name, but with your ability to take a punch without letting on that you are hurt. Geoffrey gives a wonderful description of what it is like to be on the receiving end of an accomplished sparring partner.’

Beattie, Geoffrey W. (1982). ‘Turn-taking and Interruption in Political Interviews: Margaret Thatcher and Jim Callaghan Compared and Contrasted’. Semiotica 29 (1/2): 93–114.

—, Anne Cutler and Mark Pearson (1982). ‘Why Is Mrs Thatcher Interrupted So Often?’. Nature 300 (23/30 December): 744–7.

Bull, Peter, and Kate Mayer (1988). ‘Interruptions in Political Interviews: A Study of Margaret Thatcher and Neil Kinnock’. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 7 (1): 35–46.

Beattie, Geoffrey (1989). ‘Interruptions in Political Interviews: A Reply to Bull and Mayer’. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 8 (5): 327–39.

Bull, Peter, and Kate Mayer (1989). ‘Interruptions in Political Interviews: A Reply to Beattie’. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 8 (5): 341–4.

Beattie, Geoffrey (1989). ‘Interruptions in Political Interviews: The Debate Ends?’. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 8 (5): 345–8.

Bull, Peter, and Kate Mayer (1993). ‘How Not to Answer Questions in Political Interviews’. Political Psychology 14 (4): 651–66.

Beattie, Geoffrey (1996). On the Ropes: Boxing as a Way of Life. London: Victor Gollancz.

Archer, John (1997). ‘Book Review: On the Ropes: Boxing as a Way of Life, by Geoffrey Beattie’. Aggressive Behavior 23 (3): 215–6.

Research spotlight

‘The Demise of “Yes”: An Informal Look’

by John W. Trinkaus (published in Perceptual and Motor Skills, 1997)

The author explains: ‘For affirmative responses to simple interrogatories, the use of “absolutely” and “exactly” may be becoming more socially frequent than “yes”. A counting of positive replies to 419 questions on several TV networks showed 249 answers of “absolutely”, 117 “exactly”, and 53 of “yes”.’

Harmonious results

Despite what you may have heard, acoustical analysis suggests that (1) most people are not horrible singers, and (2) most horrible singers are not tone deaf – they’re just horrible singers.

In 2007, Isabelle Peretz and Jean-François Giguère of the University of Montreal, and Simone Dalla Bella, of the University of Finance and Management in Warsaw, tested the abilities of sixty-two ‘nonmusicians’ in Quebec who admitted to being ‘occasional singers’.

The very act of testing proved more difficult than Dalla Bella, Giguère and Peretz had heard it would be. Still, they published their report, in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, called ‘Singing Proficiency in the General Population’. They complain, to anyone who will listen, that it is not easy to measure the goodness or badness of singing. There is ‘no consensus’, they seem to wail, ‘on how to obtain … objective measures of singing proficiency in sung melodies’.

They devised their own test, using the refrain from a song called ‘Gens du Pays’, which people in Quebec commonly sing as part of their ritual to celebrate a birthday. That refrain, they explain, has thirty-two notes, a vocal range of less than one octave, and a stable tonal centre.

These scientists went to a public park, where they used a clever subterfuge to recruit test subjects: ‘The experimenter pretended that it was his birthday and that he had made a bet with friends that he could get 100 individuals each to sing the refrain of Gens du Pays for him on this special occasion.’

The resulting recordings became the raw material for intensive computer-based analysis, centring on the vowel sounds – the ‘i’ in ‘mi’, for example. Peretz, Giguère and Dalla Bella assessed each performance for pitch stability, number of pitch interval errors, ‘changes in pitch directions relative to musical notation’, interval deviation, number of time errors, temporal variability and timing consistency. For comparison, they recorded and assessed several professional singers performing the same snatch of song.

Peretz, Giguère and Dalla Bella give a cheery assessment of the untrained, off-the-street singers: ‘We found that the majority of individuals can carry a tune with remarkable proficiency. Occasional singers typically sing in time, but are less accurate in pitch as compared to professional singers. When asked to slow down, occasional singers greatly improve in performance, making as few pitch errors as professional singers.’ Only a very few, they say, were ‘clearly out of tune’.

The scientists then focused on two of the horrid singers. Both screechers were ‘aware that they sang out of tune’. They proved to be almost the opposite of tone deaf. When tested, they ‘correctly detected 90% and 96% of pitch deviations in a melodic context’.

Peretz has continued to study the mystery of poor singing. In 2012, she and her colleague Sean Hutchins finished a comprehensive study. Harmoniously with the earlier finding, they conclude that most bad singers are good at hearing fine sounds, and bad at making them.

Dalla Bella, Simone, Jean-François Giguère and Isabelle Peretz (2007). ‘Singing Proficiency in the General Population’. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America 121 (2): 1182–9.

Hutchins, Sean, and Isabelle Peretz (2012). ‘A Frog in Your Throat or in Your Ear?: Searching for the Causes of Poor Singing’. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 141 (1): 76–97.

Nervous calls

Businesses need a way to detect nervousness on the telephone, says a 2011 patent, which offers a computerised means of accomplishing this.

Inventor Valery Petrushin obtained his doctorate in computer science from the Glushkov Institute for Cybernetics, Kiev, and now works in Illinois. His patent is for a method of ‘detecting emotion in voice signals in a call center’.

A simple flow chart illustrates ‘a method for detecting nervousness in a voice in a business environment to prevent fraud’. We see the following three statements, each enclosed in its own box: ‘Receiving voice signals from a person during a business event’; ‘Analyzing the voice signals for determining a level of nervousness of the person during the business event’; ‘Outputting the level of nervousness of the person prior to completion of the business event’. Petrushin recommends his invention also to improve ‘contract negotiation, insurance dealings … in the law enforcement arena as well as in a courtroom environment, etc’. He specifies a few of the many applications in these fields: ‘fear and anxiety could be detected in the voice of a person as he or she is answering questions asked by a customs officer, for example’.

Petrushin assigned his patent rights to Accenture Global Services Ltd, the giant international advice-for-almost-everything consulting company. Accenture sells call-centre-centric services to BSkyB (‘BSkyB increased its customer satisfaction while enhancing its bottom-line performance’, its website once noted) and other high-flying firms.

The patent, in essence, presents a recipe that has missing steps. That’s because scientists have not yet found a reliable mechanical way to identify emotions. But there’s hope (the document implies), in that ‘psychologists have done many experiments and suggested theories’.

The method relies on ‘statistics of human associations of voice parameters with emotions’. These parameters are acoustical – all about the vibrations of the voice, paying no attention to the words those sounds happen to represent. Words can be misleading; if spoken different ways, they might carry different emotions.

This all grew out of, and in a sense headed sideways from, Petrushin’s early research about telephone-borne emotion. Those were the days before fear came to prominence. A study he published in 2000 identified a different emotion as the one to focus on for industrial purposes. Petrushin wrote at that time: ‘It was not a surprise that anger was identified as the most important emotion for call centers.’

After recording one of four sentences: ‘This is not what I expected’; ‘I’ll be right there’; ‘Tomorrow is my birthday’; and ‘I’m getting married next week’. One of the study question posed: ‘Which kinds of emotions are easier/harder to recognize?’ The researchers explain: ‘people better understand how to express/decode anger and sadness than other emotions’.

His experiment back then measured the ability of then-current computer programs to correctly identify different emotions in recorded voices. The patent filing, eleven years later, speaks of improvement in the emotional technology. In the best of several test runs, it says, ‘We can see that the accuracy for fear is higher (25–60%) … The accuracy for sadness and anger is very high: 75–100% for anger and 88–93% for sadness.’

Petrushin, Valery A. (2011). ‘Detecting Emotion in Voice Signals in a Call Center’. US patent no. 7,940,914, 10 May.

— (2000). ‘Emotion Recognition in Speech Signal: Experimental Study, Development, and Application’. Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Spoken Language Processing, Beijing: 222–5.

May we recommend

‘The Personality of Vegetables: Botanical Metaphors for Human Characteristics’

by Robert Sommer (published in Journal of Personality, 1988)

Women’s dirty words

‘Expletives of Lower Working-Class Women’, published in 1992 in the journal Language in Society, is a rare sociolinguistic study of this inherently provocative topic. ‘This article’, wrote author Susan Hughes of the University of Salford, ‘sets out to look at the reality of the swearing used by a group of women from a deprived inner-city area’. Hughes surveyed six women in Ordsall, a part of Salford said to be characterized by ‘social malaise’.

‘My observations of these women’, Hughes wrote, ‘showed me that, contrary to some theories, they use a strong vernacular style … These women are proud of their swearing: “We’ve taught men to swear, foreigners what’s come in the pub.” Their general conversation is peppered with fuck, twat, bastard, and so on. Yet they do differentiate between using swearwords in general conversation and using them with venom and/or as an insult.’

That traditional practice of womanly swearing, if it is to survive, must deal with challenges. Fifteen years after the Hughes study was published, a corrupting influence came to town. A home insurance firm announced that Ordsall had attained a place on the company’s Young Affluent Professionals Index. Ordsall, they said, had become a ‘property hotspot’ attracting wealthy young professionals. The newcomers will have something to say about the community’s evolving expletive standards.

Hughes’ study gave scholars a clean picture of those standards prior to yuppie adulteration. She perhaps hinted that tensions would arise if outsiders were to move in. ‘The use of “prestigious” standard English has no merit nor relevance for these [lower working-class] women, it cannot provide any social advantage to them or increase any life chances for them. In fact, the standard norm would isolate them from their own tight-knit community.’

Hughes explicity based her inquiry on an elegant, simple piece of research performed a few years earlier. Barbara Risch, at the University of Cincinnati, published a study called ‘Women’s Derogatory Terms for Men: That’s Right, “Dirty” Words’. Risch surveyed forty-four female, mostly middle-class students, asking each of them to answer the following question:

There are many terms that men use to refer to women which women consider derogatory or sexist (broad, chick … piece of ass, etc.). Can you think of any similar terms or phrases that you or your friends use to refer to males?

Risch reported that: ‘A classification system for the fifty variant terms emerged quite naturally from the data obtained. The responses can be classified under the following headings: references to birth, ass, head, dick, boys, animal, meat, and other.’

She gave advice to future expletive researchers: ‘The importance of female interviewers for the results of this study cannot be overemphasized. It is doubtful whether any response would have been elicited in the presence of male interviewers.’

Recent expletive research uses MRI scanners to try to see what happens physically in someone’s brain when they swear. Typified by 1999’s ‘Expletives: Neurolinguistic and Neurobehavioral Perspectives on Swearing’, these studies owe a debt, at least in spirit, to the cussing women of Ordsall and Cincinnati.

Hughes, Susan E. (1992). ‘Expletives of Lower Working-Class Women’. Language in Society 21 (2): 291–303.

Risch, Barbara (1987). ‘Women’s Derogatory Terms for Men: That’s Right, “Dirty” Words’. Language in Society 16 (3): 353–8.

Van Lancker, Diana, and Jeffrey L. Cummings (1999). ‘Expletives: Neurolinguistic and Neurobehavioral Perspectives on Swearing’. Brain Research Reviews 31 (1): 83–104.

In brief

‘Usage and Origin of Expletives in British English’

by Hana Cechová (thesis, Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic, 2006)

Party politics gone random

Democracies would be better off if they chose some of their politicians at random. That’s the word, mathematically obtained, from a team of Italian physicists, economists and political analysts. The team includes a trio whose earlier research showed, also mathematically, that bureaucracies would be more efficient if they promoted people at random.

Alessandro Pluchino, Andrea Rapisarda, Cesare Garofalo and two other colleagues at the University of Catania in Sicily published their new study in a physics journal Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. The study itself is titled ‘Accidental Politicians: How Randomly Selected Legislators Can Improve Parliament Efficiency’.

The scientists made a simple calculation model that mimics the way modern parliaments work, including the effects of particular political parties or coalitions. In the model, individual legislators can cast particular votes that advance either their own interests (one of which is to gain re-election), or the interests of society as a whole. Party discipline comes into play, affecting the votes of officials who got elected with help from their party.

But when some legislators are selected at random – owing no allegiance to any party – the legislature’s overall efficiency improves. That higher efficiency, the scientists explain, comes in ‘both the number of laws passed and the average social welfare obtained’ from those new laws.

Parliamentary voting behaviour echoes, in a surprisingly detailed mathematical sense, something economist Carlo M. Cipolla sketched in his 1976 essay published in book form, The Basic Laws of Human Stupidity (see page 9). Cipolla gave an insulting, yet possibly accurate, description of any human group: ‘human beings fall into four basic categories: the helpless, the intelligent, the bandit and the stupid’. Pluchino, Rapisarda, Garofalo and their colleagues base their mathematical model partly on this fourfold distinction.

The maths indicate that parliaments work best when some – but not all – of the members have been chosen at random. The study explains how a country, subject to the quirks of its own system, can figure out what mix will give the best results.

Random selection may feel like a mathematician’s wild-eyed dream. It’s not. The practice was common in ancient Greece, when democracy was young. The study tells how, in Athens, citizens’ names were placed into a randomisation device called a kleroterion.

Later on, legislators were selected randomly in other places, too. In Bologna, Parma, Vicenza, San Marino, Barcelona and bits of Switzerland, say the scientists, and ‘in Florence in the 13th and 14th century and in Venice from 1268 until the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797, providing opportunities to minorities and resistance to corruption’.

Athens, way back when, used random selection to people its juries. So, still, does much of the world.

And it’s not just juries. Iceland, having survived a financial collapse in the first decade of the twenty-first century, set about devising a new constitution. For advice on that, the nation assembled a committee of 950 citizens chosen at random.

In 2010, Pluchino et al. were awarded an Ig Nobel Prize in management for demonstrating mathematically that organizations would become more efficient if they promoted people at random.

Pluchino, Alessandro, Cesare Garofalo, Andrea Rapisarda, Salvatore Spagano and Maurizio Caserta (2011). ‘Accidental Politicians: How Randomly Selected Legislators Can Improve Parliament Efficiency’. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 390 (21/22): 3944–54.

Pluchino, Alessandro, Caesar Garofalo and Andrea Rapisarda (2010). ‘The Peter Principle Revisited: A Computational Study’. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 389 (3): 467–72.

Cipolla, Carlo M. (1976). The Basic Laws of Human Stupidity. Bologna: The Mad Millers/Il Mulino.

Great adventures in accounting

The supposedly staid, unglamorous field of accounting is in fact packed, to some degree, with exciting adventures. But accountants rarely divulge this fact to persons outside the profession. Three monographs, all produced in Australia, document some of the adventure – and even some of the excitement.

In 1967, a paper by Professor R.J. Chambers of the University of Sydney, called ‘Prospective Adventures in Accounting Ideas’, appeared in the journal Accounting Review. Looking both backwards and forwards, Chambers enthuses ruefully: ‘These fifty years have seen quite a few potentially fruitful ideas, with wide implications, brought to notice, noticed scarcely at all and almost abandoned … Some 43 years ago, [accounting scholar Henry Rand] Hatfield said “Let us boldly raise the question whether accounting, the late claimant for recognition as a profession, is not entitled to some respect, or must it consort with crystal-gazing … and palmreading?” I wonder what Hatfield would think today, to see how far some would have us go in the direction of crystal-gazing. I leave you to think about what I am referring to.’

Decades of accounting adventures later, Lee D. Parker of the University of Adelaide penned a thirty-one-page study, ‘Historiography for the New Millennium: Adventures in Accounting and Management’, for a rival journal. Parker explains, almost giddily, that ‘we stand on the threshold of the new millennium, facing, on one hand, an academy avowedly presentist and futurist in its research orientation, but, on the other hand, signs of a society rediscovering its past with upsurges of interest in heritage building and artefacts preservation, cinema audiences attracted to the plots of Thomas Hardy and Jane Austen and a host of historical periods and events, historical tourism, thriving antique furniture markets and so on.’

Parker comes to a barely restrained conclusion: ‘While we owe the twentieth century founders of accounting and management history a considerable debt, there remains much for us to learn and even more to discover. Let us begin.’

The turn of the century brought a new openness to, maybe even nostalgia and yearning for, accounting adventure, symbolized by the publication of a jaunty paper by Lorne Cummings and Mark Valentine St. Leon of Macquarie University in the journal Accounting History.

Table 1 from ‘Jugglers, Clowns and Showmen: The Use of Accounting Information in Circus in Australia’. The authors state: ‘Bemoaning the liquidation of his Wild West and circus enterprise in Melbourne in 1913, the American showman Bud Atkinson said that “about 8,300 pounds [was] put into the show”, a figure which probably includes the cost of shipping personnel from the west coast of the United States, as well as the purchase, or construction, and shipment of its American-built wagons.’

Called ‘Juggling the Books: The Use of Accounting Information in Circus in Australia’, it savours the accounting practices of Australian circuses during the period from 1847 to 1963. ‘Responding to the call for an increased historical narrative in accounting’, write Cummings and St. Leon, ‘we have studied the literature, documentation and personal memoirs concerning circus in Australia … We have established that, despite elementary levels of education, many circus people exhibited an intuitive grasp of fundamental accounting principles, albeit in a rudimentary form. Nevertheless, since financial and management reporting practises were typically unsystematic, and even non-existent, in all but the largest circus enterprises, Australian circus management may not have been optimized.’

Chambers, R.J. (1967). ‘Prospective Adventures in Accounting Ideas’. Accounting Review 42 (2): 241–53.

Parker, Lee D. (1999). ‘Historiography for the New Millennium: Adventures in Accounting and Management’. Accounting History 4 (2): 11–42.

Cummings, Lorne, and Mark Valentine St. Leon (2009). ‘Juggling the Books: The Use of Accounting Information in Circus in Australia’. Accounting History 14 (1-2): 11–33.

May we recommend

‘Vagueness: An Exercise in Logical Analysis’

by Max Black (published in Philosophy of Science, 1937)

Shepherds and hunters and butchers, oh my

When you hobnob with Slovakian shepherds, don’t mention wolves. A new study called ‘Mitigating Carnivore-Livestock Conflict in Europe: Lessons from Slovakia’, says: ‘Compared to other sectors of society shepherds had the most negative attitudes, particularly towards wolves.’

Wolves are again roaming the forests of Slovakia. They were almost wiped out in the mid-twentieth century, then reappeared thanks to a thirty-year moratorium on hunting. Now the small-but-growing wolf population has restored its tradition of helping local livestock go missing or get mauled.

The researchers, Robin Rigg and Maria Wechselberger at the Slovak Wildlife Society, Slavomír Findo at the Carpathian Wildlife Society, Martyn Gorman at the University of Aberdeen, and Claudio Sillero-Zubiri and David Macdonald at the University of Oxford, published their work in the journal Oryx.

They found that, mostly, wolves grab sheep near the edge of a forest, especially if the shepherds employ what the scientists call ‘ineffective methods (chained dogs and inadequate electric fencing)’. Experimenting, the team identified two effective methods: unchained guard dogs and adequate fencing. As with much research, the obvious was apparently not obvious beforehand to all who needed to know about it.

Appreciating carnivore-livestock conflict

That’s the story with shepherds. Now, for people who kill lots of animals: hunters and butchers. A study by an Austrian/British/Malaysian team probes the psychological differences between them.

The monograph, ‘Multi-method Personality Assessment of Butchers and Hunters: Beliefs and Reality’, appeared last year in the journal Personality and Individual Differences. The authors, Martin Voracek (the one and same, mentioned elsewhere in this volume), Stefan Stieger and Viren Swami, learned, through direct questioning, that 102 Austrian university students feel hunters and butchers have ‘higher aggressiveness and masculinity’. The students also seem to believe that hunters – but not butchers – possess unusually high self-esteem.

The researchers then studied twenty-five hunters and twenty-three butchers from rural Lower Austria, and compared them with forty-eight persons who neither hunt nor butcher.

First, they tested for hypermasculinity, using a survey technique that ‘gauges macho personality’. They verified their findings ‘unobtrusively’, by doing an analysis based on the relative lengths of each person’s second and fourth fingers.

Then they used a standard test to measure each person’s self-esteem. They double-checked by having each individual rate ‘the likeability of all letters of the alphabet’, bearing in mind that ‘letters appearing in individuals’ names, especially their initials, are rated more favorably than the remainder of the alphabet’.

All told, the researchers ‘found little evidence for the factuality of’ hunters or butchers having great masculinity, aggressiveness or self-esteem.

Rigg, Robin, Salvomír Findo, Maria Wechselberger, Martyn L. Gorman, Claudio Sillero-Zubiri and David W. Macdonald (2011). ‘Mitigating Carnivore-Livestock Conflict in Europe: Lessons from Slovakia’. Oryx 45 (2): 272–80.

Voracek, Martin, Daniela Gabler, Carmen Kreutzer, Stefan Stieger, Viren Swami and Anton K. Formann (2010). ‘Multi-method Personality Assessment of Butchers and Hunters: Beliefs and Reality’. Personality and Individual Differences 49 (7): 819–22.

Research spotlight

‘Digit Ratio (2D:4D) and Wearing of Wedding Rings’

by Martin Voracek (published in Perceptual and Motor Skills, 2008)

Wedding rings, diminished or dismissed

A gold wedding band symbolises permanence, but bits of it disappear as a marriage endures, scraping against the marital skin every moment that metal and finger convene. Georg Steinhauser, a chemist at Vienna University of Technology, calculated how much goes missing, how quickly and at what cost.

Figure 1: ‘The author’s wedding ring’ from Steinhauser (2008)

Steinhauser’s study,’ Quantification of the Abrasive Wear of a Gold Wedding Ring’, appears in a 2008 issue of Gold Bulletin, a quarterly journal published by the World Gold Council, whose stated goal is ‘to stimulate desire for gold by articulating core truths and discovering new opportunities’.

Steinhauser got married. A week later he weighed his wedding ring. He weighed it every week over the next year. The report shows a graph of the weight, revealing an average loss of about 0.12 milligrams per week.

Figure 2: ‘Extraordinary events (potentially) influencing the abrasion are noted’.

Steinhauser estimated that, every year, the city of Vienna, with slightly more than 300,000 married couples, suffers an aggregate loss from its rings of about 2.2 kilograms of eighteen-carat gold, worth (at the time) approximately 35,000 euros.

Steinhauser says: ‘Due to abrasion of metal particles, human fingers wearing gold rings leave a trace of gold almost everywhere.’ He warns his fellow scientists to ‘not wear gold rings in analytical laboratories that are dedicated to the analysis of traces of metals, because a gold ring or the skin that has been in contact with the ring are possible sources of contamination’.

So it is important to give some thought to where you wear your wedding ring, a fact brought bleakly home, and then to an infirmary, in 2002. The urology department of the University of Bonn in Germany received a visit from a fifty-nine-year-old man who had slipped his wedding band from its habitual home on a knuckled digit on to a different, non-knuckled digit, to which it became tightly attached. Too tightly.

After a period of questioning and photograph-taking, the medical staff brought out a small machine called a metal-ring cutter. They snipped the ring asunder, freeing it from the withered post that had come to inhabit it in a fashion known medically as ‘strangled’.

A quartet of medicos published a graphic study about this in the journal Urology. ‘To our knowledge’, they write, ‘this is the first report of a wedding ring used as [a] constriction device.’

Steinhauser, Georg (2008). ‘Quantification of the Abrasive Wear of a Gold Wedding Ring’. Gold Bulletin 41 (1): 51–7.

Perabo, Frank G.E., Gabriel Steiner, Peter Albers and Stefan C. Müller (2002). ‘Treatment of Penile Strangulation Caused by Constricting Devices’. Urology 59 (1): 137.

Call for submissions

If you know of any improbable research – the sort that makes you laugh and think, and that you think will make other people laugh, too – I would be delighted and grateful to hear about it.

Please email me at marca@improbable.com with an improbable subject line of your choosing.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to my wife, Robin, our socially challenged yet ever-helpful dog Milo, my parents, my ever-astounding editor, Robin Dennis, and equally stout-hearted agents, Regula Noetzli and Caspian Dennis (who is still, as far as I know, not related by blood or marriage to Robin Dennis).

Thanks to helpful friends/colleagues at The Guardian, especially Tim Radford, Will Woodward, Claire Phipps, Donald MacLeod, Alice Wooley, Ian Sample and Alok Jha.

Thanks to each of the many people who told me about things that wound up in this book, some of whom are named: Richard Akerman, Gábor Andrássy, Claudio Angelo, Catherine L. Bartlett, Yoram Bauman, Sandra Betar, Tommy Burch, Jim Cowdery, Sofia Dahl, Kristine Danowski, Tommy Dighton, Martin Eiger, Stefanie Friedhoff, Martin Gardiner, Eric Geigle, Tom Gill, Jessica Girard, Diego Golombeck, Richard Gustafson, Stephen Hale, Andrea Halpern, N. Hammond, Silvia Haneklaus, Kathryn Hedges, Mark Henderson, D.E. Hepplewhite, K. Kris Hirst, Torbjörn Karfunkel, Geoffrey Kendrick, Maarten Keulemans, Greg Kohs, Erwin Kompanje, C. Lajcher, Frederic Lepage, Mark Lewney, El Lisse, Shelly Marino, Pedro Marques-Vidal, Benno Meyer-Rochow, James H. Morrissey, Ernst Niebur, Mason Porter, Hanne Poulsen, Tim Reese, Achim Reisdorf, G. Jules Reynolds, Felicia Sanchez, Ewald Schnug, Ivan Schwab, Sally Shelton, Derek R. Smith, John Troyer, Kurt Verkest, Marcy Weisberg, Greg Wells, Anna Wexler, and quite a few more whose names I apologize for not listing here.

Thanks also to the following individuals who have helped in delighful, and sometimes improbable ways, in recent years: Siobhan Abeyesinghe, Dany Adams, Henry Akona, Faraz Alam, Kendra Albert, Deborah Anderson, Helen Arney, Amar Asher, James Bacon, Richard Baguley, Robin Ball, Chris Balliro, Matthew Battles, Bob Batty, Jackie Baum, Alice Bell, Jim Bell, Michael Berry, Monica Berry, Stephan Bolliger, Tina Bowen, Jim Bredt, Ryan Budish, Estrella Burgos, Heidi Clark, Brian Clegg, Charlotte Burn, Mary Carmichael, Rita Carter, Sarah Castor-Perry, Sylvie Coyaud, J.V. Chamary, Stuart Clark, Julie Clayton, Brian Clegg, Stevyn Colgan, Michael Conterio, Mo Costandi, Ian Day, Charles Deeming, Neil Denny, Judith Donath, Nick Doody, Gary Dryfoos, Chris Dunford, Stanley Eigen, the family Eliseev/Eliseeva, Steve Farrar, Lucy Feilen, Maria Ferrante, Melissa Franklin, Hayley Frend, Andrew J.T. George, Jean Berko Gleason, Ray Goldstein, Alain Goriely, David C. Green, Katherine Griffin, Boris Groysberg, Jenny Gutbezahl, James Harkin, Margaret Harris, Hunter Heinlen, Jeff Hermes, Dudley Herschbach, Arthur Hinds, Jens Holbach, Adam Holland, Andrew Holding, Fariba Houman, Jonnie Hughes, Gareth Jones, Terry Jones, Susan Kany, David Kessler, Sandra Klemm, Bart Knols, Eliza Kosoy, Peter Lamont, Frederic Lepage, Maggie Lettvin, Henry Leitner, Julia Lunetta, Georgia Lyman, Mark Lynas, L. Mahadevan, Alice Martelli, Lauren Maurer, Chris McManus, Xiao-Li Meng, Thomas Michel, Kees Moeliker, Lauren Mulholland, Gustav Nilsonne, Ivan Oransky, Amanda Palmer, Rohit Parwani, Charles Paxton, Bruce Petschek, Johan Pettersson, Tacye Phillipson, Mason Porter, Thomas Povey, Aarathi Prasad, Tim Radford, Gus Rancatore, Ros Reid, Rich Roberts, SciCurious, Sid Rodrigues, Santi Rodriquez, the family Rosenberg, Steffen Ross, Michael Rutter, Faina Ryvkin, Molly Sauter, Helen Scales, Dan Schreiber, Margo Seltzer, Wolter Seuntjens, Alom Shaha, Annette Smith, Chris Smith, Alicia Solow-Niederman, Volker Sommer, Graham Southorn, Hari Sriskantha, Naomi Stephen, Richard Stephens, Brian Sullivan, Geri Sullivan, Wolter Suntjens, Vaughn Tan, Peaco Todd, Patrick Warren, Simon Watt, Magnus Whalberg, Corky White, Tony Whitehead, Anna Wilkinson, Stuart Wilson, Jane Winans, Richard Wiseman, George Wolford, Thomas Woolley, Helen Zaltzman, Jonathan Zittrain, Eric Zuckerman, and quite a few more whose names I also apologize for not listing here.

Extra Citations

Research spotlight

Bean, Robert Bennett (1919). ‘The Weight of the Leg in Living Men’. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2 (3): 275–82.

Brase, Gary L., Dan V. Caprar, and Martin Voracek (2004). ‘Sex Differences in Response to Relationship Threats in England and Romania’. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 21 (6): 763–78.

Di Noto, Paula M., Leorra Newman, Shelley Wall and Gillian Einstein (2012). ‘The Hermunculus: What Is Known about the Representation of the Female Body in the Brain?’. Cerebral Cortex 23 (5): 1005–13.

Einstein, Andrew J. (2010). ‘President Obama’s Coronary Calcium Scan’. Archives of Internal Medicine 170 (13): 1175–6.

Einstein, Gillian, April S. Au, Jason Klemensberg, Elizabeth M. Shin and Nicole Pun (2012). ‘The Gendered Ovary: Whole Body Effects of Oophorectomy’. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 44 (3): 7–17.

Einstein, Shlomo Stan. (2012). ‘An Ode to Substance Use(r) Intervention Failure(s): SUIF’. Substance Use and Misuse 47 (13/14): 1687–721.

Manning, John T., and Peter E. Bundred (2000). ‘The Ratio of 2nd to 4th Digit Length: A New Predictor of Disease Predisposition?’. Medical Hypotheses 54 (8): 5–7.

— and Frances M. Mather (2004). ‘Second to Fourth Digit Ratio, Sexual Selection, and Skin Colour’. Evolution and Human Behavior 25 (1): 38–50.

Romans, Sarah, Rose Clarkson, Gillian Einstein, Michele Petrovic and Donna Stewart (2012). ‘Mood and the Menstrual Cycle: A Review of Prospective Data Studies’. Gender Medicine 9 (5): 361–84.

Trinkaus, John W. (1980). ‘Preconditioning an Audience for Mental Magic: An Informal Look’. Perceptual and Motor Skills 51 (1): 262.

— (1980). ‘Honesty at a Motor Vehicle Bureau: An Informal Look’. Perceptual and Motor Skills 51 (3): 1252.

— (1990). ‘Queasiness: An Informal Look’. Perceptual and Motor Skills 70 (2): 1393–4.

— (1997). ‘The Demise of “Yes”: An Informal Look’. Perceptual and Motor Skills 84 (3): 866.

Van den Bergh, Bram, and Siegfried Dewitte (2006). ‘Digit Ratio (2D:4D) Moderates the Impact of Sexual Cues on Men’s Decisions in Ultimatum Games’. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273 (1597): 2091–5.

Voracek, Martin, and Maryanne L. Fisher (2002). ‘Sunshine and Suicide Incidence’. Epidemiology 13 (4): 492–4.

— and Gernot Sonneck (2002). ‘Solar Eclipse and Suicide’. Americna Journal of Psychiatry 159 (7): 1247–8.

Voracek, Martin A., Albinas Bagdonas, and Stefan G. Dressler (2007). ‘Digit Ratio (2D:4D) in Lithuania Once and Now: Testing for Sex Differences, Relations with Eye and Hair Color, and a Possible Secular Change’. Collegium Antropologicum 31 (3): 863–8.

Voracek, Martin (2008). ‘Digit Ratio (2D:4D) and Wearing of Wedding Rings’ Perceptual and Motor Skills 106 (3): 883–90.

— and Stefan G. Dressler (2010). ‘Relationships of Toe-length Ratios to Finger-length Ratios, Foot Preference, and Wearing of Toe Rings’. Perceptual and Motor Skills 110 (1): 33–47.

Westerhof, Danielle (2005). ‘Celebrating Fragmentation: The Presence of Aristocratic Body Parts in Monastic Houses in Twelfth- and Thirteenth-Century England’. Citeaux Commentarii Cistercienses 56 (1): 27–45.

In brief

Appel, Markus (2011). ‘A Story about a Stupid Person Can Make You Act Stupid (or Smart): Behavioral Assimilation (and Contrast) as Narrative Impact’. Media Psychology 14 (2): 144–67.

Bernhard, Jeffrey D. (1995). ‘The Swedish Pimple: Or, Thoughts on Specialization’. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 32 (3): 505–9.

Bessa Jr, Octavio. (1993). ‘Tight Pants Syndrome: A New Title for an Old Problem and Often Encountered Medical Problem’. Archives of Internal Medicine 153 (11): 1396.

Beveridge, Allen (1966). ‘Images of Madness in the Films of Walt Disney’. Psychiatric Bulletin 20 (10): 618–20.

Bohigian, George H. (1997). ‘The History of the Evil Eye and Its Influence on Ophthalmology, Medicine and Social Customs’. Documenta Ophthalmologica 94 (1/2): 91–100.

Burton, Thomas C. (1998). ‘Pointing the Way: The Distribution and Evolution of Some Characters of the Finger Muscles of Frogs’. American Museum Novitates paper no. 3229.

Cechová, Hana (2006). ‘Usage and Origin of Expletives in British English’. Undergraduate thesis, Department of English Language and Literature, Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic, 20 April.

Cluley, Robert (2011). ‘The Organization of Santa: Fetishism, Ambivalence and Narcissism’. Organization 18 (6): 779–94.

Davidson, T.K. (1972). ‘Panti-Girdle Syndrome’. British Medical Journal 2 (5810): 407.

Dreber, Anna, Christer Gerdes and Patrik Gränsmark (2013). ‘Beauty Queens and Battling Knights: Risk Taking and Attractiveness in Chess’. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 90: 1–18.

Drummond, J.R., and G.S. McKay (1999). ‘Biting Off More Than You Can Chew: A Forensic Case Report’. British Dental Journal 187 (9): 466.

George, M., and J. Round (2006). ‘An Eiffel Penetrating Head Injury’. Archives of Disease in Childhood 91 (5): 416.

Ham, Charles, Nicholas Seybert and Sean Wang (2013). ‘Narcissism is a Bad Sign: CEO Signature Size, Investment, and Performance’. University of North Carolina Kenan-Flagler Business School research paper no. 2013–1, 19 March.

Hansen, Christian Stevns, Louise Holmsgaard Faerch and Peter Lommer Kristensen (2010). ‘Testing the Validity of the Danish Urban Myth that Alcohol Can Be Absorbed Through Feet: Open Labelled Self Experimental Study’. British Medical Journal 341: c6812.

Hauber, Mark E., Paul W. Sherman and Dóra Paprika (2000). ‘Self-referent Phenotype Matching in a Brood Parasite: The Armpit Effect in Brown-headed Cowbirds (Molothrus alter)’. Animal Cognition 3 (2): 113–7.

Hostetter, Autumn B., Martha W. Alibali and Sotaro Kita (2007). ‘Does Sitting on Your Hands Make You Bite Your Tongue? The Effects of Gesture Prohibition on Speech During Motor Descriptions’. In McNamara, D.S., and J.G. Trafton (eds). Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Nashville, TN, 1-4 August. Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society: 1097–1102.

Hurd, Peter L., Patrick J. Weatherhead and Susan B. McRae (1991). ‘Parental Consumption of Nestling Feces: Good Food or Sound Economics?’. Behavioral Ecology 2 (1): 69–76.

Isaacs, D. (1992). ‘Glue Ear and Grommets’. Medical Journal of Australia 156 (7): 444–5.

Khairkar, Praveen, Prashant Tiple and Govind Bang (2009). ‘Cow Dung Ingestion and Inhalation Dependence: A Case Report’. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 7 (3): 488–91.

Lattimer, J.K., and A. Laidlaw (1996).‘Good Samaritan Surgeon Wrongly Accused of Contributing to President Lincoln’s Death: An Experimental Study of the President’s Fatal Wound’. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 182 (5): 431–48.

Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno, and Jozsef Gal (2003). ‘Pressures Produced When Penguins Pooh: Calculations on Avian Defaecation’. Polar Biology 27: 56–8.

Morse, Donald R. (1993). ‘The Stressful Kiss: A Biopsychosocial Evaluation of the Origins, Evolution, and Societal Significance of Vampirism’. Stress Medicine 9 (3): 181–99.

Nikolić, Hrvoje (2008). ‘Would Bohr Be Born If Bohm Were Born Before Born?’. American Journal of Physics 76 (2): 143.

Pekár, S., D. Mayntz, T. Ribeiro and M.E. Herberstein (2010). ‘Specialist Ant-eating Spiders Selectively Feed on Different Body Parts to Balance Nutrient Intake’. Animal Behaviour 79 (6): 1301–6.

Ros, S.P., and F. Cetta (1992). ‘Metal Detectors: An Alternative Approach to the Evaluation of Coin Ingestions in Children?’. Pediatric Emergency Care 8 (3): 134–6.

Sahoo, Manash Ranjan, Anil Kumar Nayak, Tapan Kumar Nayak and S. Anand (2013). ‘Fracture Penis: A Case More Heard about than Seen in General Surgical Practice’. BMJ Case Reports.

Schmidt, Steven P., H. Gibbs Andrews and John J. White (1992). ‘The Splenic Snood: An Improved Approach for the Management of the Wandering Spleen’. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 27 (8): 1043–4.

Shafik, A. (1996). ‘Effect of Different Types of Textiles on Male Sexual Activity’. Archives of Andrology 37 (2): 111–5.

Shelah, Saharon (2000). ‘On What I Do Not Understand (and Have Something to Say), Part I’. Fundamenta Mathematicae 168 (1/2): 1–82.

Shravat, B.P., and S.N. Harrop (1995). ‘Broken Hand or Broken Nose: A Case Report’. Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine 12: 225–6.

Slay, Robert D. (1986). ‘The Exploding Toilet and Other Emergency Room Folklore’. Journal of Emergency Medicine 4 (5): 411–4.

Spradley, M. Katherine, Michelle D. Hamilton and Alberto Giordano (2011). ‘Spatial Patterning of Vulture Scavenged Human Remains’. Forensic Science International 219 (1): 57–63.

Taylor, W.S., and E. Culler (1929). ‘The Problem of the Locomotive-God’. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 24 (3): 342–99.

Turner, M. (1991). ‘Panty Hose-Pants Disease’. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 164 (5): 1366.

Walmsley, Christopher W., Peter D. Smits, Michelle R. Quayle, Matthew R. McCurry, Heather S. Richards, Christopher C. Oldfield, Stephen Wroe, Phillip D. Clausen and Colin R. McHenry (2013).‘Why the Long Face?: The Mechanics of Mandibular Symphysis Proportions in Crocodiles’. PLos ONE 8 (1): e53873.

Walz, F.H., M. Mackay and B. Gloor (1995). ‘Airbag Deployment and Eye Perforation by a Tobacco Pipe’. Journal of Trauma 38 (4): 498–501.

Whitaker, J.H. (1977). ‘Arm Wrestling Fractures: A Humerus Twist’. American Journal of Sports Medicine 5 (2): 67–77.

White, P.D. (1973). ‘The Tight-Girdle Syndrome’. New England Journal of Medicine 288 (11): 584.

Williams, S. Taylor (2012). ‘ “Holy PTSD, Batman!”: An Analysis of the Psychiatric Symptoms of Bruce Wayne’. Academic Psychiatry 36 (3): 252–5.

Zerbe, K.J. (1985). ‘ “Your Feet’s Too Big”: An Inquiry into Psychological and Symbolic Meanings of the Foot’. Psychoanalytic Review 72 (2): 301–14.

May we recommend

Beaver, Bonnie V., Margaret Fischer and Charles E. Atkinson (1992). ‘Determination of Favorite Components of Garbage by Dogs’. Applied Behaviour Science 34 (1): 129–36.

Bemelman, M., and E.R. Hammacher (2005). ‘Rectal Impalement by Pirate Ship: A Case Report’. Injury Extra 36: 508–10.

Black, Max (1937). ‘Vagueness: An Exercise in Logical Analysis’. Philosophy of Science 4 (4): 427–55.

Bond, J.H., and M.D. Levitt (1979). ‘Colonic Gas Explosion: Is a Fire Extinguisher Necessary?’. Gastroenterology 77 (6): 1349–50.

Christen, J.A., and C.D. Litton (1995). ‘A Bayesian Approach to Wiggle-Matching’. Journal of Archaeological Science 22 (6): 719–25.

Craig, J.M., R. Dow and M. Aitken (2005). ‘Harry Potter and the Recessive Allele’. Nature 436 (7052): 776.

Eley, Karen A., and Daljit K. Dhariwal (2010). ‘A Lucky Catch: Fishhook Injury of the Tongue’. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock 3 (1): 92–3.

Elgar, M.A., and B.J. Crespi (eds) (1992). Cannibalism: Ecology and Evolution among Diverse Taxa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Farrier, Sarah, Iain A. Pretty, Christopher D. Lynch and Liam D. Addy (2011). ‘Gagging during Impression Making: Techniques for Reduction’. Dental Update 38 (3): 171–6.

Fujihira, H. (1978). ‘Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Bang-Bang Control’. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications 25 (4): 549–54.

Fujimura, Jun, Kenji Sasaki, Tsukasa Isago, Yasukimi Suzuki, Nobuo Isono, Masaki Takeuchi and Motohiro Nozaki (2007). ‘The Treatment Dilemma Caused by Lumps in Surfers’ Chins’. Annals of Plastic Surgery 59 (4): 441–4.

Gentzkow, Matthew, and Jesse M. Shapiro (2006). ‘Does Television Rot Your Brain? New Evidence from the Coleman Study’. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 12021, February.

Ghanem, Hussein, Sidney Glina, Pierre Assalian and Jacques Buvat (2013). ‘Position Paper: Management of Men Complaining of a Small Penis Despite an Actually Normal Size’. Journal of Sexual Medicine 10 (1): 294–303.

Gifford, Robert and Robert Sommer (1968). ‘The Desk or the Bed?’. Personnel and Guidance Journal 46 (9): 876–8.

Goldberg, R.L., P.A. Buongiorno and R.I. Henkin (1985). ‘Delusions of Halitosis’. Psychosomatics 26 (4): 325–7, 331.

Hansen, Kim V., Lars Brix, Christian F. Pedersen, Jens P. Haase and Ole V. Larsen (2004). ‘Modelling of Interaction between a Spatula and a Human Brain’. Medical Image Analysis 8 (1): 23–33.

Ho, Luis C., Alexei V. Filippenko and Wallace L.W. Sargent (1997). ‘The Influence of Bars on Nuclear Activity’. Astrophysical Journal 487 (2): 591–602.

Jackson, C.R., B. Anderson and B. Jaffray (2003). ‘Childhood Constipation Is Not Associated with Characteristic Fingerprint Patterns’. Archives of Disease in Childhood 88 (12): 1076–7.

Kompanje, Erwin J.O. (2013). ‘Real Men Wear Kilts: The Anecdotal Evidence that Wearing a Scottish Kilt Has Influence on Reproductive Potential – How Much Is True?’. Scottish Medical Journal 58 (1): e1–5.

Lee, C.T., P. Williams, and W.A. Hadden (1999). ‘Parachuting for Charity: Is It Worth the Money? A 5-Year Audit of Parachute Injuries in Tayside and the Cost to the NHS’. Injury 30 (4): 283–7.

Leung, A.K. (1984). ‘Doll Shoes: The Cause of Behavioural Problems?’. Canadian Medical Association Journal 131 (10): 1193.

Lim, Erle C.H., Amy M.L. Quek and Raymond C.S. Seet (2006). ‘Duty of Care to the Undiagnosed Patient: Ethical Imperative, or Just a Load of Hogwarts?’. Canadian Medical Association Journal 175 (12): 1557–9.

Lisi, Antony Garrett (2007). ‘An Exceptionally Simple Theory of Everything’. arXiv.org, 6 November, http://arxiv.org/abs/0711.0770.

Mandell, Arnold J., Karen A. Selz, John Aven, Tom Holroyd and Richard Coppola (2010). ‘Daydreaming, Thought Blocking and Strudels in the Taskless, Resting Human Brain’s Magnetic Fields’. Paper presented at the International Conference on Applications in Nonlinear Dynamics, AIP Conference Proceedings 1339 (2011): 7–22.

Moeliker, C.W. (2007). ‘A Penis-shortening Device Described by the 13th Century Poet Rumi’. Archives of Sexual Behavior 36 (6): 767.

Morice, Alyn H. (2004). ‘Post-Nasal Drip Syndrome: A Symptom to be Sniffed At?’. Pulmonary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 17 (6): 343–5.

Petrof, Elaine O., Gregory B. Gloor, Stephen J. Vanner, Scott J. Weese, David Carater, Michelle C. Daigneault, Eric M. Brown, Kathleen Schroeter and Emma Allen-Vercoe (2013). ‘Stool Substitute Transplant Therapy for the Eradication of Clostridium difficile Infection: “RePOOPulating” the Gut’. Microbiome 1 (3): http://www.microbiomejournal.com/content/1/1/3/additional.

Pon, Brian, and Alan Meier (1993). ‘Hot Potatoes in the Gray Literature’. Recent Research in the Building Energy Analysis Group, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, paper no. 3, October.

Ryter, Stefan W., Danielle Morse and Augustine M.K. Choi (2004). ‘Carbon Monoxide: To Boldly Go Where NO Has Gone Before’. Science STKE: Signal Transduction Knowledge Environment 2004 (230): re6.

Seimens, H.W. (1967). ‘The History of Freckles in Art’. Der Hautarzt 18 (5): 230–2.

Silverberg, Jesse L., Matthew Bierbaum, James P. Sethna and Itai Cohen (2013). ‘Collective Motion of Humans in Mosh and Circle Pits at Heavy Metal Concerts’. Physical Review Letters 110 (22): 228701.

Smith, G.C.S., and J.P. Pell (2003). ‘Parachute Use to Prevent Death and Major Trauma Related to Gravitational Challenge: Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials’. British Medical Journal 327: 1459–61.

Sommer, Robert (1988). ‘The Personality of Vegetables: Botanical Metaphors for Human Characteristics’. Journal of Personality 56 (4): 665–83.

Soussignan, Robert, Paul Sagot and Benoist Schaal (2007). ‘The “Smellscape” of Mother’s Breast: Effects of Odor Masking and Selective Unmasking on Neonatal Arousal, Oral and Visual Response’. Developmental Psychobiology 49 (2): 129–38.

Stern, Ronald J., and Henry Wolkowicz (1991). ‘Exponential Nonnegativity on the Ice Cream Cone’. SIAM: Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications 12 (1): 160–5.

Troughton, Geoffrey M. (2006). ‘Jesus and the Ideal of the Manly Man in New Zealand after World War One’. Journal of Religious History 30 (1): 45–60.

Yerhuham, I., and O. Koren (2003). ‘Severe Infestation of a She-Ass with the Cat Flea Ctenocephalides felis felis (Bouche, 1835)’. Veterinary Parasitology 115 (4): 365–7.

An improbable innovation

Bublitz, Rebecca J., and Annette L. Terhorst (2003). ‘Human-figure display system’. US patent no. 6,601,326, granted 5 August.

Castanis, George and Thaddeus Castanis (1982). ‘Producing Replicas of Body Parts’, US patent no. 4,335,067, granted 15 June.

Huffman, Hugh, and Ernest J. Peck (1916). ‘A New and Useful Improvement in Scarecrows’. US patent no. 1,167,502, granted 11 January.

Lowe, Henry E. (1983). ‘Odor Testing Apparatus’. US patent no. 4,411,156, granted 25 October.

MacDonald, Louise S. (2011). ‘Internal nostril or nasal airway sizing gauge’. US patent no. 7,998,093, granted 16 August.

McMorrow, Philip E. (1968). ‘Animal Track Footwear Soles’. US patent no. 3,402,485, granted 24 September.

Shemesh, David, and Dan Forman (2004). ‘Automated Surveillance Monitor of Non-humans in Real Time’. US patent no. 6,782,847, granted 31 August.

Williams, Hermann W. (1931). ‘A Safety Device for Use in Making a Landing from an Aeroplane or Other Vehicle of the Air’. US patent no. 1,799,664, granted 7 April.

Call for investigators

Haller, Daniel G. (2013). ‘A Call for Opinions’. Gastrointestinal Cancer Research 6 (1): 1.

Oum, Robert E., Debra Lieberman and Alison Aylward. ‘A Feel for Disgust: Tactile Cues to Pathogen Presence’. Cognition & Emotion 25 (4): 717–25.

The inhumanity of prozac

Deckel, A.W. (1996). ‘Behavioral Changes in Anolis carolinensis Following Injection with Fluoxetine’. Behavioural Brain Research 78: 175–82.

Dodman, Nicholas H., R. Donnelly, Louis Shuster, F. Mertens, W. Rand and Klaus Miczek (1996). ‘Use of Fluoxetine to Treat Dominance Aggression in Dogs’. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 209 (9): 1585–7.

Fehrer, S.C., Janet L. Silsby and Mohamed E. El Halawani (1983). ‘Serotonergic Stimulation of Prolactin Release in the Young Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo)’. General and Comparative Endocrinology 52 (3): 400–8.

Freire-Garabal, Manuel, María J. Núñez, Pilar Riveiro, José Balboa, Pablo López, Braulio G. Zamarano, Elena Rodrigo and Manuel Rey-Méndez (2002). ‘Effects of Fluoxetine on the Activity of Phagocytosis in Stressed Mice’. Life Sciences 72 (2): 173–83.

Henderson, Daniel R., Darlene M. Konkle and Gordon S. Mitchell (1999). ‘Effects of Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibition on Ventilatory Control in Goats’. Respiration Physiology 115 (1): 1–10.

Huber, Robert, Kalim Smith, Antonia Delago, Karin Asaksson and Edward A. Kravitz (1997). ‘Serotonin and Aggressive Motivation in Crustaceans: Altering the Decision to Retreat’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 94 (11): 5939–42.

Khan, Izhar A., and Peter Thomas (1992). ‘Stimulatory Effects of Serotonin on Maturational Gonadotropin Release in the Atlantic Croaker, Micropogonias undulatus’. General and Comparative Endocrinology 88 (3): 388–96.

McKay, D.M., David W. Halton, J.M. Allen and Ian Fairweather (1989). ‘The Effects of Cholinergic and Serotoninergic Drugs on Motility in Vitro of Haplometra cylindracea (Trematoda: Digenea)’. Parasitology 99 (2): 241–52.

Poulsen, E.M., V. Honeyman, P.A. Valentine and G.C. Teskey (1996). ‘Use of Fluoxetine for the Treatment of Stereotypical Pacing Behavior in a Captive Polar Bear’. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 209 (8): 1470–4.

Pryor, Patricia A., Benjamin L. Hart, Kelly D. Cliff and Melissa J. Bain (2001). ‘Effects of a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor on Urine Spraying Behavior in Cats’. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 72 (2): 173–83.

Smith, Greg N., Joseph Hingtgen and William DeMyer (1987). ‘Serotonergic Involvement in the Backward Tumbling Response of the Parlor Tumbler Pigeon’. Brain Research 400 (2): 399–402.

Villalba, Constanza, Patricia A. Boyle, Edward J. Caliguri and Geert J. DeVries (1997). ‘Effects of the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Fluoxetine on Social Behaviors in Male and Female Prairie Voles (Microtus ochrogaster)’. Hormones and Behavior 32 (3): 184–91.

Illustration Credits

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the many researchers and inventors whose work is illustrated in these pages, sometimes with illustrations, sometimes without.

Page numbers refer to the print version.

A classic in the body of 2D:4D work (p. xii) adapted from ‘A Preliminary Investigation of the Associations between Digit Ratio and Women’s Perception of Men’s Dance’ by Bernhard Fink, Hanna Seydel, John T. Manning and Peter M. Kappeler