Study Notes for 2 Chronicles

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 1:1–2:18 Solomon’s Temple Preparations. God provides Solomon with the wealth, material, and workers to build the temple.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 1:1–6 Solomon’s journey to the Mosaic tabernacle and altar at Gibeon, like David’s mission to retrieve the ark (1 Chron. 13:1–16:43), is presented as a public enterprise that involves all Israel (cf. 1 Kings 2:4). Like David, Solomon maintains continuity with the Mosaic covenant as the foundation of his own reign. Sought it out (cf. esv footnote, “him,” i.e., Yahweh) continues the parallel with David (see 1 Chron. 13:3). Solomon begins his reign as David instructed him (1 Chron. 22:19), by worshiping God and seeking guidance. Bezalel is the master craftsman of the tabernacle, assisted by Oholiab (see Ex. 31:1–11). See note on 2 Chron. 2:11–16.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 1:7–13 Solomon’s faithful seeking leads to a nighttime appearance of God (in a dream, according to 1 Kings 3:5), in which God invites Solomon to ask in prayer for whatever he desires (cf. John 15:7). Solomon’s request that God will fulfill his promise to David (see 1 Chron. 17:23) looks forward to the completion of the temple (2 Chron. 6:17), while his request for wisdom and knowledge is focused not on selfish ambition but on the need to govern God’s people wisely (see note on 1 Kings 3:11–14). God grants Solomon’s request and also promises him riches, possessions, and honor that he did not request. This theme is taken up again at the end of the Solomon narrative (2 Chron. 8:1–9:28). numerous as the dust of the earth. God’s covenant promise to Abraham (Gen. 13:16) was being fulfilled in Solomon’s day.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 1:14–17 From 1 Kings 10:27–29, and repeated with some modifications at 2 Chron. 9:25–28. This section demonstrates the fulfillment of God’s promise of wealth (1:12; see note on 1 Kings 10:26–29).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 2:1 a temple for the name of the LORD. See Deut. 12:5. God’s “name” in association with a place signifies his actual presence there among his people, where God may be met and petitioned. Yet in no sense is God contained or limited by his localized presence: see 2 Chron. 2:6. The Chronicler’s temple theology embraces both the actual or real presence of God and his majestic transcendence. It is a forerunner to the doctrine of the incarnation of God in Christ (see John 2:21). royal palace. Linked here with the temple, perhaps to indicate the close connection between the two “houses” of the Davidic covenant (see 1 Chron. 17:14). While the Chronicler mentions Solomon’s palace a number of times (2 Chron. 2:12; 7:11; 8:1; 9:3–4, 11), he passes over the account of its construction (1 Kings 7:1–12).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 2:2 Solomon used the forced labor of Canaanites living in the land (see vv. 17–18; cf. notes on 8:7–10; 1 Chron. 22:2–5) for the construction work. Subject peoples were often conscripted to such work in the ancient world.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 2:3–10 Solomon’s letter to Hiram, king of Tyre (who had earlier assisted David; 1 Chron. 14:1), is considerably expanded from 1 Kings 5:3–6 to describe the purpose of the temple for regular and seasonal worship according to the Law of Moses, to express the supremacy and transcendence of Israel’s God (2 Chron. 2:5–6), and to request a skilled craftsman (v. 7), along with different kinds of timber (v. 8). The Hebrew for skilled (khakam) also means “wise.” Its use here consciously echoes Solomon’s request for wisdom (1:10) and the wisdom and knowledge Solomon needs for building the temple (2:5–6). The skills called for here recall Oholiab’s work on the tabernacle, under the direction of Bezalel (Ex. 31:1–11).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 2:6 heaven, even highest heaven, cannot contain him. See note on 1 Kings 8:27–30.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 2:11–16 Hiram’s letter of reply includes a Gentile’s acknowledgment of Yahweh as Creator, and of God’s gift of wisdom to Solomon (v. 12), which is especially focused on the task of temple building (cf. note on 1 Kings 5:9–12). Huram-abi is likened to Oholiab (the mothers of both men are said to be descended from Dan; see Ex. 31:6; cf. note on 1 Kings 7:13–14), while Solomon the temple builder is implicitly compared to Bezalel, who directed the building of the tabernacle (see 2 Chron. 1:5). The reference in 2:16 to Joppa (not mentioned in 1 Kings 5:9) may reflect Ezra 3:7. Timber from Lebanon for the second temple was floated to that port.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 3:1–5:1 Solomon’s Building of the Temple. The temple is to be a fit place for God to dwell among his people.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 3:1–17 The Chronicler’s actual account of the construction of the temple is much briefer than his source (1 Kings 6). The architectural details of 1 Kings 6:4–20a are passed over, as are the descriptions of the intricate carvings or stonework in 1 Kings 6:29–36. Instead, the Chronicler leads his readers in their imagination through the vestibule (2 Chron. 3:4) into the ornate nave or Holy Place (vv. 5–7), then on to the Most Holy Place (vv. 8–13), partitioned off by the veil (v. 14). The numerous references to gold (vv. 4–10) and cherubim (vv. 7, 10–14) highlight the splendor of the temple as the heavenly King’s earthly palace. As its structure and furnishings indicate, it stood in continuity with the Mosaic tabernacle, at the same time exceeding it in beauty and opulence. The temple measured about 90 feet by 30 feet (27 m by 9.1 m; v. 3), so it was not particularly large compared to many modern church buildings, and it did not function as a place of congregational worship. Only priests would have been admitted to the temple itself, and only the high priest could enter the Most Holy Place, and only on the Day of Atonement.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 3:1 Mount Zion is identified here with Mount Moriah, where Abraham was commanded to offer Isaac (Gen. 22:2).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 3:2 See 1 Kings 6:1. Depending on which chronology is followed, this may have been in either 966 or 959 B.C.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 3:4 120 cubits. The Septuagint and other ancient versions of the OT suggest that the vestibule was actually 20 cubits (30 feet/9.1 m) high. The Hebrew text lacks the word “cubits,” so precise identification of the height is uncertain.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 3:6 Parvaim. Possibly a place in northeastern Arabia.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 3:8–13 The Most Holy Place was the secret, cube-shaped room in which the ark of the covenant would be finally deposited (5:7). The cherubim were angelic beings that combined human and animal features (cf. Ezek. 10:14; 41:18–19) and served as throne-guards to the ark. On the construction of the temple, see note on 1 Kings 6:14–35.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 3:14 The Most Holy Place was separated from the rest of the sanctuary by a veil as well as by doors (4:22). The inclusion of the veil signified the continuity of the temple with the Mosaic tabernacle (Ex. 26:31–35). Herod’s temple was similarly arranged (Matt. 27:51); the tearing of the veil at the death of Christ indicated that the “shadow” of the Mosaic institutions had now given way to the final sacrifice of Christ, with all its benefits (see Heb. 9:11–12; 10:1).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 3:15–17 thirty-five cubits high. Probably the combined heights of the pillars (see note on 1 Kings 7:15–21; cf. 1 Kings 7:15; 2 Kings 25:17). Jachin (“he establishes”); Boaz (“in him is strength”). The names may signify that Yahweh establishes his covenant through the temple.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 4:1–5:1 The temple’s furnishings communicated the same message as that signified by the structure of the building: the presence of the holy God in the midst of his people, and his gracious provision of atonement and forgiveness. For the Chronicler’s own generation, the fact that these vessels had been returned from their Babylonian captivity (Ezra 1:3–11; 6:5) was a sign as well that they were still God’s covenant people and the heirs of his promises to David and Solomon.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 4:1 Solomon’s altar stood outside the temple. Perhaps it stood in front of the temple entrance, just as Moses’ altar had stood before the entrance of the tabernacle (Ex. 40:6), though it may have stood in the northeast corner, opposite the bronze sea basin in the southeast corner.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 4:2–6 On various details of the temple, cf. notes on 1 Kings 7:23–47. The sea was a large, circular water tank, located outside the southeast corner of the temple (2 Chron. 4:10) and used by the priests for their ceremonial cleansing before they entered the temple (v. 6). It corresponded to the bronze basin that had stood between the entrance to the tabernacle and the Mosaic altar (Ex. 30:18–21). 3,000 baths. First Kings 7:26 reads “two thousand baths.” The difference may be due to a copyist’s error. The twelve oxen probably signified the tribes of Israel, especially as they were encamped around the four sides of the tabernacle in the wilderness (see Num. 2:1–31).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 4:2 ten cubits … thirty cubits. See note on 1 Kings 7:23.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 4:7–8 In contrast to the tabernacle, with its one seven-branched lampstand and table (Ex. 25:31–36), Solomon’s temple had ten of each (but cf. 1 Kings 7:48, which mentions only one table). The tables were apparently for the “bread of the Presence” (2 Chron. 4:19; see 1 Chron. 9:32), a perpetual bread offering to Yahweh, through which Israel consecrated itself to God (Ex. 25:30).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 4:9 the court of the priests. A feature that also corresponds to the tabernacle; see Ex. 27:9–19.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 4:11b–22 The bronze vessels and furnishings were located in the temple entrance and court, while those in the interior (the place of greater holiness) were made of gold. The golden altar was for the burning of incense (see Ex. 30:1–10; 1 Chron. 28:18). The Most Holy Place was separated from the nave (the Holy Place) by inner doors … of gold as well as the veil (2 Chron. 3:14).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 4:19 Solomon made all the vessels. See note on 1 Kings 7:48–51.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 5:1 A summary statement, again recalling that the temple was the joint enterprise of Solomon and David (see 1 Chron. 17:8; 22:2–16).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 5:2–7:22 The Dedication of the Temple. The Chronicler’s account of the dedication of the temple is notably longer than his description of the building work (77 verses compared to 40), since he is more concerned with the meaning of the temple than with its physical structure. This interest is conveyed through the two theophanies (5:14; 7:1–3), Solomon’s great prayer of dedication (6:14–42), and God’s message to Solomon (7:12–22).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 5:2–3 Just as David had summoned all the leaders of Israel to retrieve the ark from Kiriath-jearim (1 Chronicles 13; 15), Solomon also assembled them for the ark’s final journey from its tent in the city of David (see 1 Chron. 16:1). the feast that is in the seventh month. The Feast of Booths (see Lev. 23:33–43). The temple was completed in the eighth month of Solomon’s eleventh year (see 1 Kings 6:38 = 959 or 952 B.C.), and the dedication took place 11 months later. The Israelites had been instructed to live in temporary shelters during this feast, to commemorate the exodus. It was observed annually in the seventh month of the Jewish calendar (September–October).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 5:5 Moses’ tent of meeting and its holy vessels were brought up from Gibeon (1:3) to join the ark. Similarly, the Levitical priests Asaph, Heman, and Jeduthun (5:12; see 1 Chron. 16:37, 42) were united for this ceremony. Henceforth, all of Israel’s worship would be focused on the Jerusalem temple.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 5:7–9 The priests completed the transfer of the ark, since only they could enter the Most Holy Place. And they are there to this day. A comment from an early author, whose work was used by the author of Kings (see note on 1 Kings 8:8) and the Chronicler. The ark was apparently destroyed along with the first temple and was never replaced.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 5:10 The ark had once contained the jar of manna and Aaron’s rod (Heb. 9:4; see Ex. 16:32–34; Num. 17:10–11), but now held only the two tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 5:11–14 The Chronicler inserts a lengthy sentence (vv. 11b–13) into his source (1 Kings 8:10) to describe a highly festive scene, suggesting that the cloud of God’s glory (see Ex. 13:21–22) that filled the temple came in response to the Levites’ and priests’ worship. The Chronicler’s own generation should draw a similar lesson, that God will surely be present when his people offer praise and thanksgiving. The appearance of the cloud and the inability of the priests even to stand to minister in God’s presence signified that God in his majesty was taking up residence in his temple. There is an evident parallel here, and in 2 Chron. 7:3, with the appearance of the glory cloud in the tabernacle and over the tent of meeting (cf. Ex. 40:34–35). The visible manifestation of God’s glory and presence was known in later Judaism as the “Shekinah,” and it provides the background to John’s comment about the incarnate Son: “we have seen his glory” (John 1:14). The praise of 2 Chron. 5:13b appears again in 20:21b. God’s steadfast love (Hb. hesed) in particular denotes his covenant commitment to David (1 Chron. 17:13), which has finally resulted in this temple.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:1–42 The Chronicler follows his source quite closely in his presentation of Solomon’s prayer of dedication for the temple (see 1 Kings 8:12–50a). Yet whereas the earlier version finishes with an appeal to the exodus under Moses as the basis of God’s relationship with Israel (1 Kings 8:50b–53), the Chronicler focuses instead on the Davidic covenant (2 Chron. 6:41–42, from Ps. 132:8–10). For the Chronicler’s own postexilic generation, the temple signified God’s promise to David of an enduring kingdom, however restricted Israel’s present circumstances might seem. As the focal point of God’s presence on earth, the temple also stood as a constant visible encouragement to prayer, as indicated by the different circumstances of need envisioned by Solomon in his prayer (2 Chron. 6:12–42).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:1–2 God was present in the thick darkness of the cloud on Mount Sinai (see Ex. 20:21), and has now graciously come to dwell in the Most Holy Place of the temple.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:3–11 Solomon’s accession to the throne, the completion of the temple, and the placing of the ark are all due to God’s fulfilling his promise to David (see 1 Chron. 17:23–24). Human obedience to God’s commands is the means of ratifying or accepting God’s promises, as well as a condition for experiencing the reality of the promises in the present (see 2 Chron. 6:14–17), yet God himself provides the grace for his people to obey.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:7 On the name of the LORD, see notes on 1 Kings 8:17 and Acts 10:48.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:12–13 The prayer of dedication is offered from a specially constructed platform before the altar of burnt offerings, in front of the temple entrance.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:15 On God’s promises to David, cf. 1 Chron. 17:11–14 and 22:9–10.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:18–21 The infinite God cannot be contained within space (heaven and the highest heaven), let alone any man-made structure, yet he has made the temple the point of contact and immediate communication with his people. Prayer in or toward the temple will come before God in his heavenly dwelling place because his name is on the temple (vv. 20, 34, 38), which signifies both his spiritual presence in that place and his ownership of it and is thus an invitation to pray there in confident faith. (See note on 2:1.) The NT equivalent is prayer offered in Jesus’ name (see John 14:13–14).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:22–40 Solomon offers some representative situations in which Israelites and even foreigners (v. 32) should offer prayer at or toward the temple, seeking forgiveness, vindication, and divine help.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:22–23 See Ex. 22:7–12; Num. 5:11–31; and note on 1 Kings 8:31–32. The Law of Moses provided for oaths to be taken in the sanctuary to determine guilt or innocence if there were no witnesses to an offense.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:24–25 See Lev. 26:17; Deut. 28:25; and note on 1 Kings 8:33–40. National defeat is included among the curses for covenant breaking. Exile is one possible punishment.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:26–27 heaven is shut up … no rain. See Lev. 26:19; Deut. 28:23–24; 2 Chron. 7:13; and note on 1 Kings 8:33–40.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:28–31 See Deut. 28:21 and note on 1 Kings 8:33–40. The emphasis is on God’s intimate knowledge of and concern for each individual among his people.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:32–33 See note on 1 Kings 8:41–43. Your mighty hand and your outstretched arm calls to mind God’s deliverance in the exodus (Ex. 3:19–20). Solomon envisions Gentiles making pilgrimage to pray at the temple because of what they have heard about this event. On the temple as a place of prayer for all nations, see also Isa. 2:2–4 and Zech. 8:20–23.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:34–35 God’s help in answer to prayer made in time of war is depicted in 13:14–15; 14:11; 18:31; 20:5–23; 32:20–22. See note on 1 Kings 8:44–45.

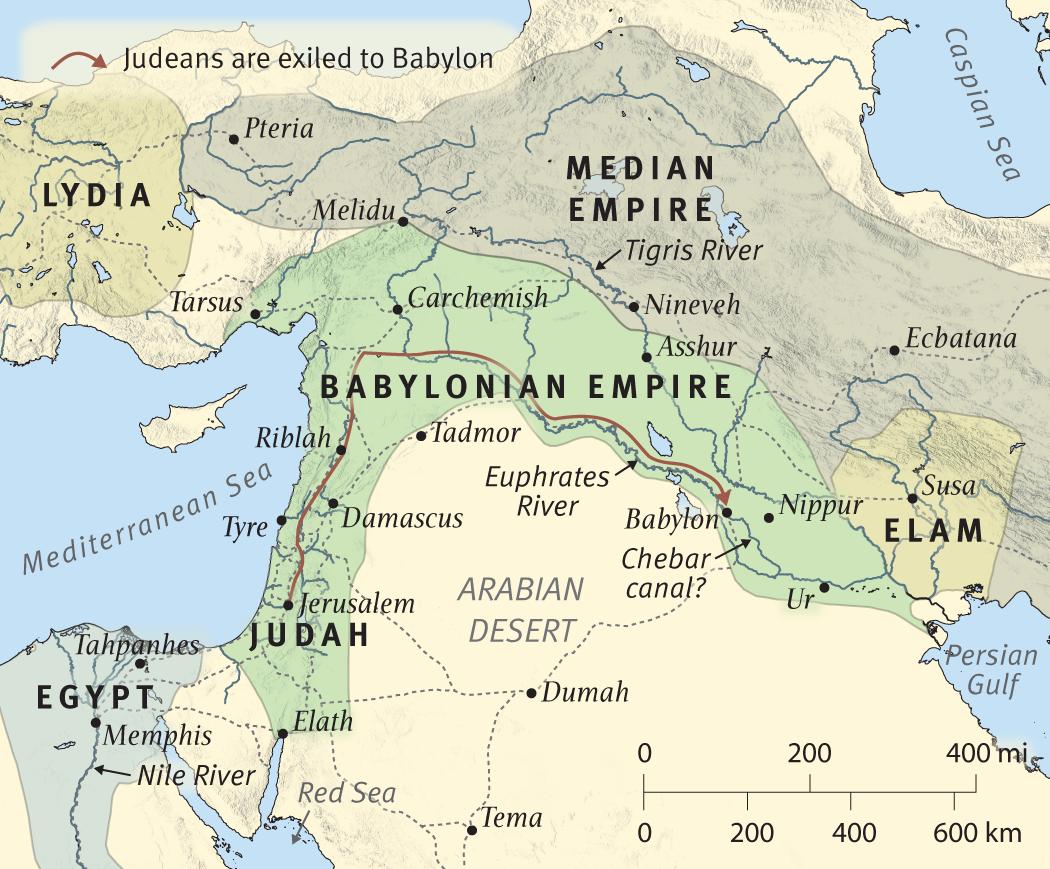

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:36–39 See note on 1 Kings 8:46–51. Exile from the Promised Land is presented as the climax of punishments on account of sin (see 2 Chron. 36:15–20). there is no one who does not sin. Cf. Prov. 20:9; Eccles. 7:20; Rom. 3:23. Solomon prays that Yahweh will respond to the heartfelt repentance of his people in exile and their intercession toward the house that I have built for your name. Bodily posture was a part of prayer, especially for exiles like Daniel, who consciously prayed in the direction of Jerusalem (Dan. 6:10).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 6:41–42 In place of the ending to this prayer in 1 Kings 8:50b–53 (an appeal to God’s mercy shown in the exodus), the Chronicler inserts a version of Ps. 132:8–10, which concerns the transfer of the ark into the temple. It functions here as a prayer that God will once again come in power and grace for the Chronicler’s generation and their temple, as he had done for the people and temple of Solomon’s day. Verse 42 of 2 Chronicles 6 is a prayer for the Davidic descendants, the recipients of God’s covenant promise of steadfast love for David. For the Chronicler, this enduring covenant is now the basis of the relationship between God and his people.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:1–22 God’s twofold answer to Solomon’s prayer (through the appearance of the glory of the Lord in vv. 1–3 and the words from God in vv. 12–22) takes readers to the heart of the Chronicler’s message of repentance and restoration. The Chronicler is acutely aware of Israel’s sinfulness (6:36), knowing that this will result in exile; but against this bleak fact he highlights Yahweh’s undeserved restorative mercy and forgiveness toward his people, for which the temple is the visible symbol. The assurance that the temple is indeed the divinely sanctioned place of atonement and prayer should encourage the Chronicler’s own postexilic generation to respond accordingly, confident that God will grant a greater measure of restoration and blessing. Ultimately, salvation will come not through a material building but through the One whom the temple foreshadows (John 2:19–21).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:1b–3 An addition to 1 Kings 8. A parallel with David (see 1 Chron. 21:26) and Moses is intended here: just as a divine fire consumed the burnt offering in the newly erected Mosaic tabernacle, and “the glory of the LORD” was visible to the people (see Lev. 9:23–24), the fire … from heaven that consumed the sacrifice signaled acceptance of the temple and the priests’ ministry there, while the glory of the LORD appeared on the temple, and the people worshiped. For he is good, for his steadfast love endures forever. Variations on this refrain from Psalm 136 occur several times in the book (see 1 Chron. 16:34; 2 Chron. 5:13; 7:6; 20:21) and may indicate a link between the author and the temple singers.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:4–10 The dedication of the temple at the Feast of Tabernacles (see 5:3) entailed vast numbers of sacrifices (7:5) and involved the whole nation in its broadest extent (v. 8). Unity, joy, and gratitude to God are the keynotes of this festival.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:8 Lebo-hamath to the Brook of Egypt designates the whole of Solomon’s empire (see note on 1 Kings 8:65–66).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:11–22 God’s reply to Solomon’s prayer is presented immediately after the account of the dedication, although in fact 13 years had elapsed, in which time the palace was also completed (v. 11; see 1 Kings 7:1; 9:10). Yahweh’s appearance at night (2 Chron. 7:12) corresponds to his first appearance to Solomon at Gibeon, at the beginning of his reign (1:7).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:12b The temple is for sacrifice as well as prayer. The OT understanding of worship regularly joins sacrifices (of atonement, dedication, or thanksgiving) with prayer as the material expression of the worshiper’s inner disposition.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:12b–16 The Chronicler’s addition to 1 Kings 9:3–4 provides a succinct summary of the central message of the book: the meaning of the temple and the response that God looks for in his people.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:13 A summary reference to the divine punishments mentioned in Solomon’s prayer (6:26, 28).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:14 if my people. God’s purpose above all is to forgive his penitent people and heal their land. The specific vocabulary of this verse (humble themselves, pray, seek, turn) describes different aspects of heartfelt repentance and will recur throughout chs. 10–36. “Heal their land” includes deliverance from drought and pestilence as well as the return of exiles to their rightful home (6:38). For the Chronicler, this includes the restoration of the people to their right relationship with God. Cf. Jer. 25:5; 26:3.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:15–16 The invitation to prayer and repentance (v. 14) is sealed with the strong assurance of God’s presence and attention in the temple.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:17–18 A summons to Solomon to be obedient to the Law of Moses as the grounds for establishing his throne. a man to rule Israel. See Mic. 5:2. Messianic hopes for the continuation of the Davidic line continued to be affirmed in the Chronicler’s time, even though the last Davidic king had been deposed in 586 B.C.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 7:19–22 The statement if you turn aside and forsake my statutes is addressed to the people (“you” in v. 19 is plural; see notes on 1 Kings 9:6; 9:7–8). While the temple signified God’s will to forgive and restore, the stubborn rejection of his statutes and commandments would lead to God’s rejection of both people and temple (see Deut. 29:24–28). The decisive factor, as shown throughout the rest of the book, is whether the call to repentance is heeded.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:1–18 This section generally follows 1 Kings 9:10–28, with a significant variation and addition (see 2 Chron. 8:2–4, 12–16).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:1–16 Solomon’s Other Accomplishments. Solomon’s further conquests and building projects are revealed, as well as his attention to matters of worship, both for himself and for the people. The success of Solomon’s various building projects are seen as blessings that follow his obedience in building the temple (which, along with his palace, took twenty years to complete).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:2 According to 1 Kings 9:11–14, Solomon had actually given these cities to Hiram, perhaps as collateral for a loan (1 Kings 9:14; cf. notes on 1 Kings 9:10–13; 9:10; 9:11). The Chronicler would then be describing their subsequent reversion to Israelite control.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:3–4 Hamath-zobah lay about 120 miles (193 km) north of Damascus (see 1 Chron. 18:3), while Tadmor lay about 125 miles (201 km) to the northeast. Control over these commercial cities represented the farthest extent of Solomon’s power. First Kings does not mention these campaigns.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:5 Upper Beth-horon and Lower Beth-horon were located on a ridge above the Valley of Aijalon northwest of Jerusalem. They were crucial to the security of the city and provided access to the international coastal highway (see also note on 1 Kings 9:17–19).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:7–10 In keeping with an ancient practice of controlling enemies, Solomon drafted the descendants of the Canaanites into forced labor for his construction projects throughout the nation. According to 1 Kings 5:13–18, Solomon imposed a less rigorous demand on the Israelites.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:11 Solomon’s Egyptian wife, Pharaoh’s daughter, was kept in a separate house and away from the ark, probably on account of her paganism (see 1 Kings 11:7–8). See Solomon’s Temple and Palace Complex.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:12–15 The Chronicler expands the brief note in 1 Kings 9:25, detailing the pattern of daily, weekly, monthly, and annual sacrifices and feasts instituted in the temple by Solomon, along with his organization of the temple personnel. Solomon’s fidelity to the instructions of Moses (2 Chron. 8:13) and David (vv. 14–15) is emphasized.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:16 So the house of the LORD was completed. The completion of the temple did not come with its building or dedication but with the institution of its regular services. Solomon proved himself faithful in his commission, and the subsequent details of his reign (8:17–9:28) represent God’s blessing on his obedience (see 1:12).

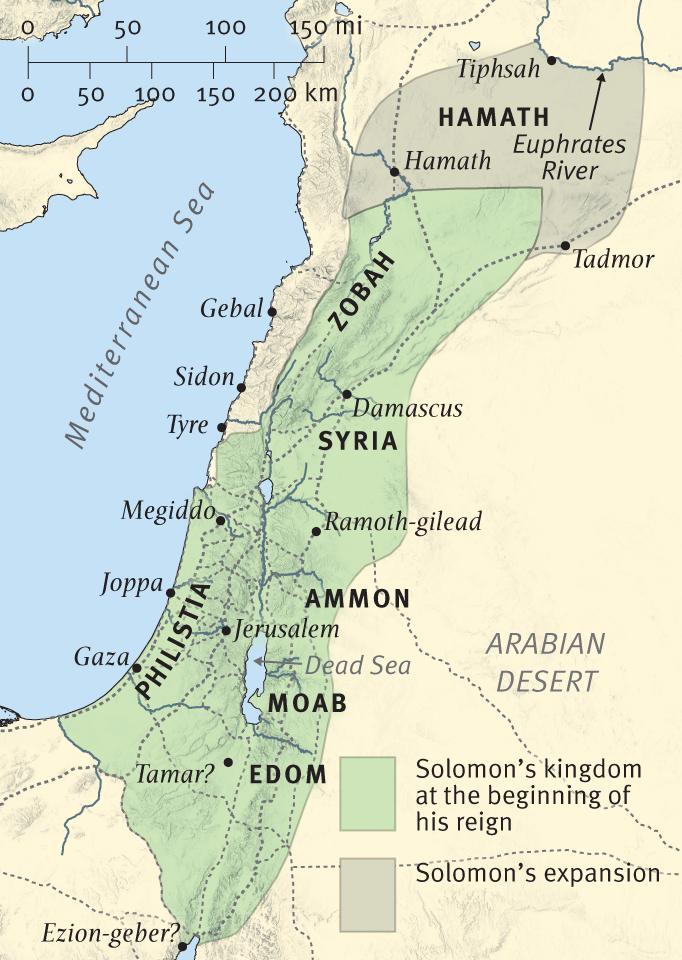

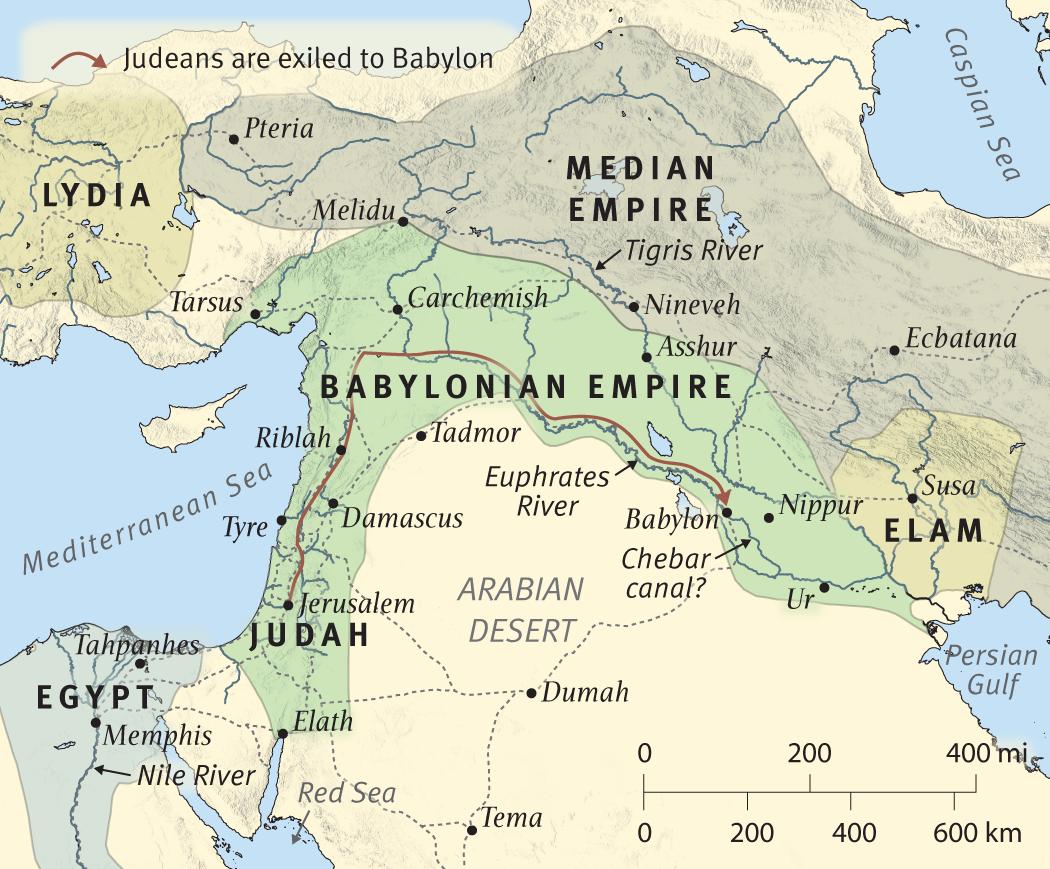

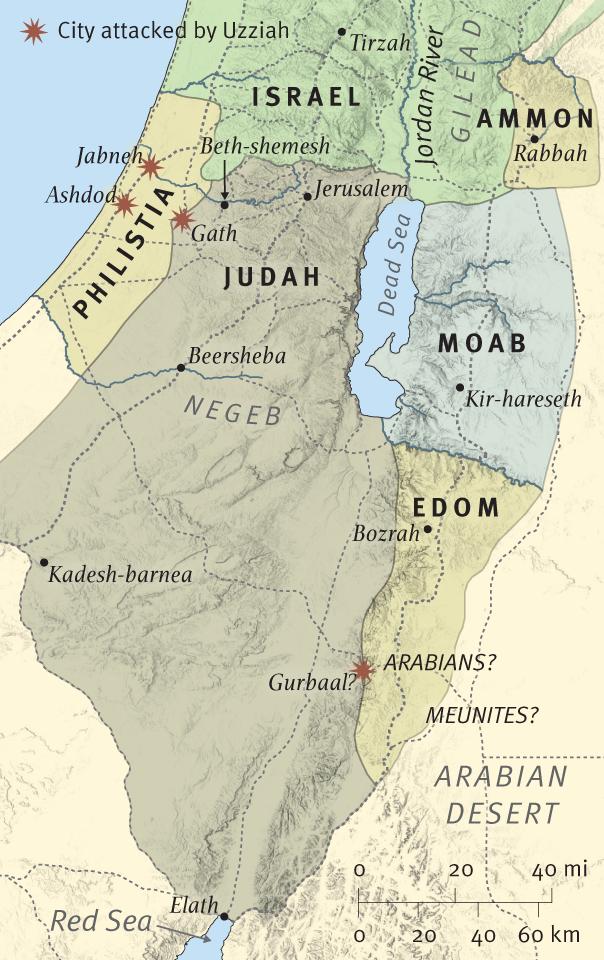

The Extent of Solomon’s Kingdom

c. 971–931 B.C.

Solomon’s reign marked the zenith of Israel’s power and wealth in biblical times. His father, David, had bestowed upon him a kingdom that included Edom, Moab, Ammon, Syria, and Zobah. Solomon would later bring the kingdom of Hamath under his dominion as well, and his marriage to Pharaoh’s daughter sealed an alliance with Egypt. His expansive kingdom controlled important trade routes between several major world powers, including Egypt, Arabia, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia (Asia Minor).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:17–9:31 Solomon’s International Relations and Renown. Solomon’s reputation and influence extend beyond the borders of Israel.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 8:17–18; 9:10–11 Ezion-geber. See note on 1 Kings 9:26–28. Israel forms the land bridge (and the trade routes) connecting the Mediterranean lands with the kingdoms on the Red Sea and beyond, into Asia. Solomon profited from his control of these routes, and from his maritime partnership with Hiram, the king of Tyre. The Tyreans (a people of Phoenician stock) were renowned for their seamanship. Ophir was probably in southwest Arabia or the Horn of Africa.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 9:1–9, 12 This section closely follows 1 Kings 10:1–13. Sheba, or Saba, corresponds roughly to modern Yemen and was a mercantile kingdom that traded in luxury goods from East Africa and India. The queen’s visit may have had commercial trade purposes (see 2 Chron. 9:1, 9) prompted by Solomon’s naval activities in the south of the Red Sea, but her visit is presented primarily as a quest for wisdom (vv. 1, 6). Solomon is acknowledged as excelling in both wisdom and wealth (see 1:12). The Gentile queen recognizes that Solomon’s greatness is from Yahweh (9:8; see 2:12) and that Solomon sits on God’s throne as his king (cf. 1 Kings 10:9, “the throne of Israel”). For the Chronicler, the Davidic kingdom is the earthly expression of God’s eternal kingdom (see 1 Chron. 17:14; 28:5; 2 Chron. 13:8). Recognition (esp. from a Gentile monarch) that God was the actual King of Israel could only encourage the postexilic community, when no descendant of David was on the throne.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 9:7 Happy are these your servants. See note on 1 Kings 10:8.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 9:9–12 On the queen’s gift of 120 talents of gold, see note on 1 Kings 10:10–13.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 9:13–28 This section closely follows 1 Kings 10:14–28. The Chronicler’s presentation of Solomon concludes with a description of the king at the zenith of his wealth and international renown (a far cry from the difficult conditions of the postexilic days; see Ezra 9:7; Neh. 9:36–37).

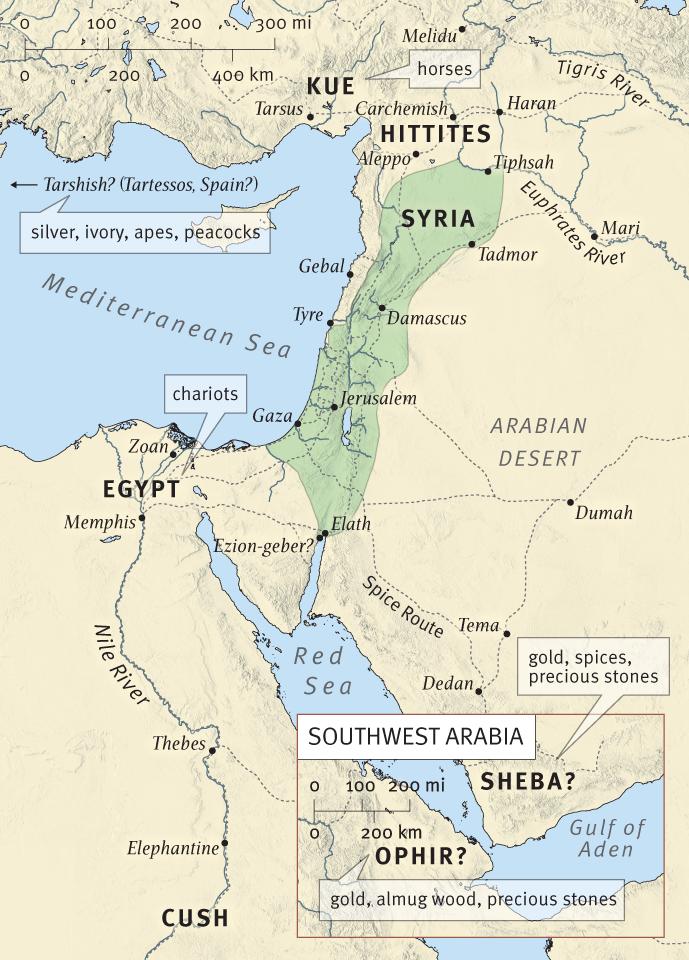

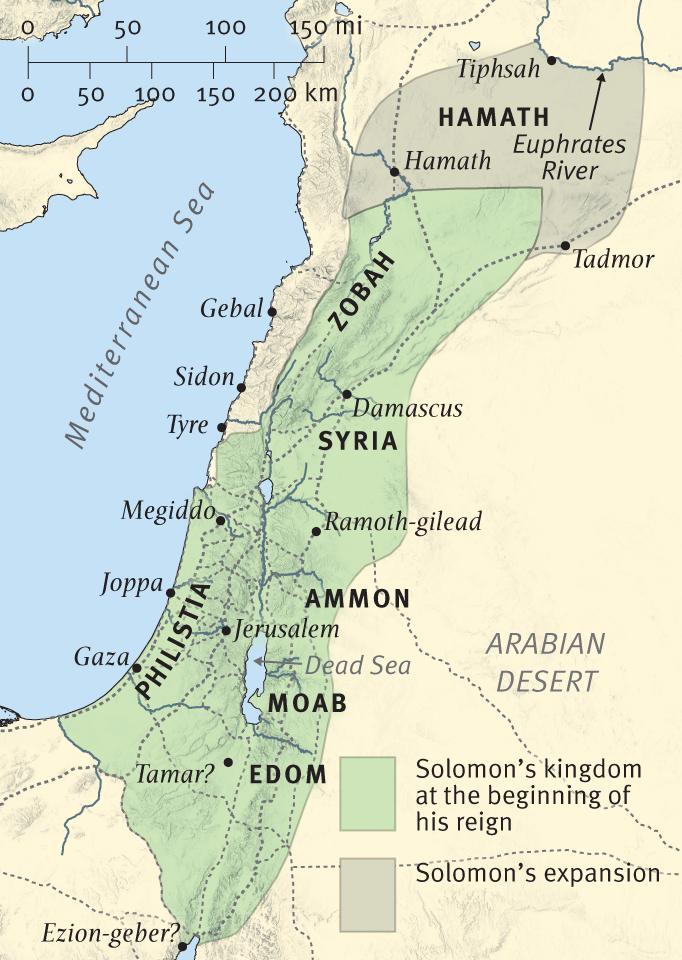

Solomon’s International Ventures

c. 950 B.C.

Solomon’s firm control of important trade routes linking Egypt, Arabia, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia (Asia Minor) provided him with incalculable wealth. Partnering with King Hiram of Tyre, Solomon also launched his own trading expeditions to Ophir to acquire valuable and exotic goods. The queen of Sheba’s visit to Solomon attests to his great fame throughout the ancient world. Solomon further augmented his wealth by buying horses from Kue and chariots from Egypt and selling them to the kings of Syria and the Hittites.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 9:13–14 Solomon’s annual revenues in gold (equal to about 22 tons) would have been derived from both tribute and trade (see note on 1 Kings 10:14–25).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 9:15–16 The House of the Forest of Lebanon was Solomon’s palace, which contained great quantities of cedar (see 1 Kings 7:2). The gold shields were lost as booty to Pharaoh Shishak by Solomon’s son Rehoboam (2 Chron. 12:9).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 9:21 Tarshish is usually identified with Tartessus in Spain, but here the Chronicler seems to use it more generically, in the sense of “the ends of the earth” (cf. Ps. 72:10).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 9:22–28 Solomon is presented as supreme over all the kings of the earth, in keeping with the promises made at the beginning of his reign (1:12). Verses 25–28 of ch. 9 are a partial repetition of 1:14–17, and thus form an inclusio (literary “bookends”) around the Chronicler’s portrayal of Solomon (cf. note on 1 Kings 10:26–29).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 9:29–31 This is from 1 Kings 11:41–43, but with additional reference to Ahijah the Shilonite (see 1 Kings 11:29–40) and Iddo the seer (traditionally identified with the unknown prophet in 1 Kings 13). Although the Chronicler omits the accounts of Solomon’s apostasy and the rebellions he faced in his declining years (1 Kings 11), the allusion to the words of these prophets directs the reader to the account in Kings, where a more critical portrayal of Solomon is preserved. As with his presentation of David, the Chronicler’s focus here is on the positive achievement of Solomon’s reign and its abiding significance for his community. Solomon slept with his fathers. See notes on 1 Kings 2:10 and 11:43.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:1–36:23 The Kingdom of Judah down to the Exile. The post-Solomonic narrative in Chronicles deals almost exclusively with the kingdom of Judah, following the division of the kingdom under Rehoboam. In contrast to 1–2 Kings, the history of the northern kingdom is considered by the Chronicler only as it touches upon that of Judah, such as in war (e.g., 2 Chronicles 13; 16; 18) or in moves toward unity (chs. 29–30). The Chronicler never disputed that the northern tribes belonged to Israel but insisted that legitimacy and leadership lay with the Davidic monarchy and the tribe of Judah.

The Kingdom Divides

931 B.C.

When Solomon’s son Rehoboam arrived at Shechem for his coronation after his father’s death, he refused to lighten his father’s heavy tax burden on the people, and the 10 northern tribes revolted and set up Jeroboam as their king. The northern kingdom would now be known as Israel and the southern kingdom as Judah. Five years later, Shishak (also called Sheshonq) king of Egypt invaded Judah and Israel and captured a number of towns. Rehoboam avoided Jerusalem’s destruction by paying off Shishak with many of the treasures Solomon had placed in the temple.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:1–12:16 Rehoboam. The reign of Rehoboam (931–915 B.C.) is dominated by the division of the kingdom and the consequences thereof. While Rehoboam is judged negatively for his failures as a leader, the Chronicler also uses his example to show how repentance and obedience may lead to the restoration of blessing.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:1–19 From 1 Kings 12:1–19. The division of the kingdom was a complex matter, to which Solomon (2 Chron. 10:4, 10, 11) and Jeroboam (13:6–7) both contributed through their disobedience, but here the focus is on Rehoboam’s folly in alienating the northerners. At the same time, the author notes that this was a turn of affairs brought about by God (10:15), indicating that God remained in control of his kingdom and that the northerners’ rebellion was understandable; it was, in fact, in accordance with the prophetic word (v. 15, which presupposes the reader’s knowledge of 1 Kings 11:29–39). It was the northerners’ later idolatry that made their continuing rebellion reprehensible (2 Chron. 13:8–10).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:1–5 Rather than simply make Rehoboam king (as he no doubt expected), the tribal leaders wished to negotiate the terms of his kingship, including relief from the forced labor imposed by Solomon.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:1 Shechem. See note on 1 Kings 12:1.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:2 Jeroboam. See 1 Kings 11:26–40.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:4 Your father made our yoke heavy. See note on 1 Kings 12:4.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:7 Speak good words appears to be a technical term meaning “make an agreement” (see 2 Kings 25:28–29).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:10 My little finger. See note on 1 Kings 12:10–11.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:14–15 I will discipline you with scorpions. The attempt to browbeat the people with threats backfired, not least because the course of events was determined by God’s will and the prophetic word (cf. notes on 1 Kings 12:14; 12:15).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:16 This poetic fragment announcing rejection of the house of David contrasts pointedly with the poetic declaration of loyalty in 1 Chron. 12:18. It was apparently the rallying cry of the northern tribes against Judah (see 2 Sam. 20:1).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 10:18 Hadoram was Solomon’s taskmaster, also called “Adoram” (see note on 1 Kings 12:18) or “Adoniram” (1 Kings 4:6; 5:14).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 11:1–12:16 The Chronicler’s account of Rehoboam’s rule over the southern kingdom is much longer and more complex than that given in Kings (1 Kings 14:21–31). As the first king of Judah after the division of the kingdom, Rehoboam serves to illustrate several of the key themes that will recur throughout the subsequent history of the Davidic monarchy: the blessings that flow from repentance and obedience to the prophetic word; conversely, the punishment that follows disobedience to God’s law; the function of the faithful Levites in strengthening the kingdom; and the constant presence of the prophetic word to guide and rebuke. Rehoboam’s reign shows how the principles and promises of judgment and restoration in 2 Chron. 7:13–14 are being enacted in the life of the kingdom, even when the king falls short of the ideal compared to his people (12:14).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 11:1–4 This is from 1 Kings 12:21–24. Rehoboam’s attempt to reunite the kingdom by force is averted by the prophet Shemaiah (see 2 Chron. 12:5, 7), who informs him that the division is from God (11:4; see 10:15).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 11:4 your relatives. Despite their rebellion (for which they had good reason at this point), the northern tribes did not cease to be part of “all Israel.” they listened to the word of the LORD. See note on 1 Kings 12:24.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 11:5–23 This information has no parallel in Kings but is derived from another source or sources (see note on 12:15–16). It illustrates the blessings that come to Judah following Rehoboam’s and the people’s obedience to the word of Yahweh (11:4), while Jeroboam leads the northerners into apostasy.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 11:5–12 The fortified cities covered the eastern, southern, and western approaches to Judah, and were thus probably intended as a defense against Egypt, Jeroboam’s ally. Yet they did not prove effective against Shishak (12:4).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 11:13–17 Jeroboam instituted his own syncretistic cult in Bethel and Dan to deter his people from going to sacrifice in Jerusalem and possibly defecting to Rehoboam (1 Kings 12:26–33). The Chronicler condemns him for his goat idols as well as golden calves (2 Chron. 11:15; see Lev. 17:7), and for driving out the legitimate priesthood (2 Chron. 11:14; 13:9). The exemplary attitude is shown by those Levites who took the costly step of abandoning their lands to move to Judah, and those laypeople who followed them to Jerusalem to offer sacrifice (11:16). Israel’s true unity was centered on the temple worship (see 15:9). The theme of the Levites’ “strengthening the kingdom” is frequent in Chronicles (see 19:8–11; 20:14–17; 29:25–30), and the task remained equally relevant in the Chronicler’s own day (1 Chron. 9:2).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 11:17 Rehoboam’s and Judah’s commitment to faithful worship and obedience to God’s law lasted only three years (12:1).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 11:18–23 The growth of Rehoboam’s family is a sign of God’s blessing on him, although these details must refer to the whole of his 17-year reign, and not just the three-year period of faithfulness to God’s law. His family is of strong Davidic lineage: the father of Mahalath was Jerimoth, presumably the son of one of David’s concubines (1 Chron. 3:9), while Maacah was probably the granddaughter of David’s son Absalom, through his daughter Tamar (2 Sam. 14:27).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 12:1 After a faithful beginning, Rehoboam seems to have descended into pride and a reliance on his own strength instead of dependence on God. That he and his people abandoned the law of the LORD is equated with abandoning God himself (v. 5): there is no effective relationship with God without obedience to his revealed will. The NT makes the same point positively when Jesus equates love for him with obedience to his commandments (John 14:21).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 12:2 unfaithful (Hb. ma‘al). A key term for the Chronicler. See note on 1 Chron. 2:3–8. The Egyptian invasion follows hard on the heels of national apostasy and is explicitly identified by the writer as God’s punishment for sin; but not every instance of distress or suffering in Chronicles is understood this way (e.g., 2 Chron. 20:1–12; 32:1, where Judah suffers foreign invasion after its kings have acted faithfully; similarly 13:8). Shishak is Sheshonq I, who ruled from 945–924 B.C. His campaign through Judah and Israel is commemorated in inscriptions on the temple at Karnak. fifth year. 925 B.C. (see note on 1 Kings 14:25–26).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 12:3 Sukkiim. Soldiers probably of Libyan origin, mentioned in Egyptian records of the thirteenth and twelfth centuries B.C.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 12:5 You abandoned me, so I have abandoned you. See 1 Chron. 28:9; 2 Chron. 15:2.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 12:6–8 humbled themselves. See 7:14. The partial deliverance that Judah experienced was intended to teach its people a fuller devotion to God. For the Chronicler’s own generation, it would have called to mind their own circumstances: subject to the Persian kings, yet free to worship Yahweh in his temple (see Ezra 9:8–9).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 12:9–11 Resumes the account from 1 Kings 14:26–28 (see note on 1 Kings 14:25–26). The treasures of the temple and palace were surrendered as tribute to avert an attack on the city.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 12:12 when he humbled himself the wrath of the LORD turned from him. This is the key point concerning Rehoboam’s reign that the Chronicler wishes to make for his readers.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 12:14 The writer’s overall estimate of Rehoboam is negative: whereas 1 Kings 14:22 (see note there) blames the people for “doing evil,” the Chronicler makes this charge against Rehoboam and adds that he did not set his heart to seek the LORD (cf. 2 Chron. 11:16).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 12:15–16 These verses generally follow 1 Kings 14:29–31 but specify that historical records from Shemaiah and Iddo contributed to the Chronicler’s sources (see note on 1 Kings 14:19). The Chronicler’s use of such sources accounts for much of the material in his work that is additional to 1–2 Kings.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:1–14:1 Abijah. The Chronicler’s account of Abijah’s reign is much longer than that given in 1 Kings 15:1–8 (where he is called Abijam). It is, in fact, mainly the development of the statement in 1 Kings 15:7 that “there was war between Abijam and Jeroboam” through the detailed record of one incident, a battle between these kings in the hill country of Ephraim. In the estimation of 1 Kings 15:3, Abijah, like his father Rehoboam, “was not wholly true to the LORD.” The Chronicler would probably agree (since it appears from 2 Chron. 14:3–5; 15:8, 16 that idolatrous worship was practiced throughout Judah during Abijah’s reign), but he refrains from explicit comment on the king’s own piety to concentrate instead on what God accomplished through his reign. The Chronicler notes that in contrast to Jeroboam’s kingdom and cult, the Davidic monarchy is the object of God’s enduring promise (13:5, 8); the Jerusalem priesthood is legitimate and faithful (13:10–11); and the men of Judah trust in God (13:13, 18). It is for these reasons that the southern kingdom enjoys God’s protection and blessing, even if Abijah himself (like his father) falls somewhat short of the ideal.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:2 three years. 915–912 B.C. Micaiah. Also spelled Maacah. See 11:20.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:3 To judge from Abijah’s words in v. 8, Jeroboam probably instigated this war, seeking to reunite the kingdom by force, as Rehoboam had tried to do (11:1–4). On the size of the armies, see note on 1 Chron. 12:23–37. However the numbers should be understood, Judah is outnumbered two to one by Israel.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:4 Mount Zemaraim. Probably on the northern border of Benjamin, on the frontier between the two kingdoms; see Josh. 18:22. Abijah’s speech is one of several royal addresses in Chronicles that serve to convey the author’s concerns—in this case, his condemnation of the northern kingdom for its apostasy and continuing rebellion.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:5–8a Abijah condemns Jeroboam and the northerners for opposing God’s grant of perpetual kingship over Israel to David and his sons. The term covenant of salt denotes a permanent provision; see Num. 18:19. Jeroboam’s kingship is dismissed as rebellion against his master, Solomon, while the Davidic kingdom is nothing less than the kingdom of the LORD (see 2 Chron. 9:8).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:8b–12 Abijah condemns the northerners for their religious unfaithfulness in making calf idols (see Hos. 8:6) and driving out the Aaronic priests and Levites in favor of their own appointees. Judah, by contrast, has the legitimate priesthood and temple worship, so Israel should not fight against the LORD. For the Chronicler’s own audience, Abijah’s speech may have functioned as a sermonic appeal to the different tribes to be united around the temple, under the leadership of the Davidic family.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:13–19 This battle report echoes older OT narratives in which God fights for and with his people (cf. v. 14 with Josh. 6:20). Judah’s reliance on God (2 Chron. 13:14, 18) is the key factor in its success.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:19 Bethel was one of the locations of Jeroboam’s calf cult (see v. 8 and 1 Kings 12:28–29).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:21 Large families are a conventional sign in Chronicles of God’s blessing on those who rely on him (see 1 Chron. 28:5; 2 Chron. 11:18–21).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 13:22 the story of the prophet Iddo. Cf. notes on 12:15–16 and 1 Kings 14:19.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 14:2–16:14 Asa. The Chronicler’s account of Asa’s reign (910–869 B.C.) is also much longer and more complex than that given in the earlier history (1 Kings 15:9–24). It describes a reign that begins well but ends badly, as trust in God and obedience to the prophetic word give way to a dependence on human alliances and the rejection of the prophetic word.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 14:2–8 Asa begins his reign in an exemplary way by rooting out idolatry and commanding Judah to seek the LORD (see 1 Chron. 22:19). High places were local sites usually associated with pagan worship (see Deut. 12:2–3). Asherim. Poles representing the fertility goddess Asherah. The subsequent building projects, large army, and peace are typical blessings for faithfulness and obedience in Chronicles (see 2 Chron. 11:5–12; 13:3; 17:10).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 14:9 Zerah the Ethiopian. Lit., “the Cushite,” from modern Sudan (see 12:3; 16:8). Not otherwise known, but possibly a general in the service of Pharaoh Osorkon I, son of Shoshenq I (12:2). A million men is literally “a thousand thousands” and represents an enormous number. An alternative way to understand this is “a thousand units” (see note on 1 Chron. 12:23–37). This is more than double the army following Asa (2 Chron. 14:8). Mareshah. One of Rehoboam’s fortified cities on Judah’s southwestern border (11:8).

Zerah Attacks Judah

898 B.C.

At some point during Asa’s long and prosperous reign over Judah, Zerah the Ethiopian led a vast army from the south to attack Judah at a valley near Mareshah. Asa’s army routed Zerah’s forces and pursued them to Gerar until none of them remained. Perhaps as punishment for Philistia allowing Zerah’s army to pass through their nation, Asa’s men then plundered many towns in the region around Gerar before returning to Jerusalem.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 14:11–15 Asa’s prayer reflects the situation envisioned in 6:34–35. Many of the motifs of sacred warfare found in ch. 13 are expressed here as well and will recur in ch. 20: a prayer (or speech) is made by the king before battle, expressing trust in God (see 13:4–12; 20:5–12); Judah faces overwhelming odds (see 13:3; 20:2); and Yahweh strikes the enemy (see 13:15–16; 20:22–23). The fear of the LORD was upon them (see 1 Chron. 14:17; 2 Chron. 20:29). The plunder was used for sacrifices (15:11).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 15:1–7 Azariah is not otherwise known. His speech is intended to encourage Asa to continue his reforms and lead the people into covenant renewal. If you seek him. See 1 Chron. 28:9. The theme of “seeking the LORD” recurs throughout 2 Chronicles 15 (vv. 4, 12, 13, 15). Verses 3–6 call to mind the unstable time of the judges, marked by cycles of apostasy and return to God (see Judges 3), and the absence of effective spiritual leadership (see Judg. 17:5–6).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 15:8 Cities that he had taken in … Ephraim implies that there had been conflict between Judah and Israel prior to the thirty-sixth year of Asa’s reign (16:1; c. 875 B.C.).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 15:9 The Chronicler highlights a number of occasions when northerners are reunited with their fellow Israelites in Judah, always in the context of worship and seeking God (cf. 11:16; 30:11, 18, 25; 35:18).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 15:10 the third month of the fifteenth year. Probably May/June 895 B.C. The assembly may have taken place during the Festival of Weeks (or Pentecost) (see Ex. 23:16 [“Feast of Harvest”]; Lev. 23:15–21).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 15:12 Effectively a renewal of the Sinai covenant (Exodus 19–20; 24), allowing the people to affirm their total commitment to Yahweh (with all their heart and with all their soul). Covenant renewal in connection with reform is also featured in 2 Chron. 23:16; 29:10; 34:31–32. The implication of these popular acts of religious commitment would have been clear to the Chronicler’s own community.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 15:13 whoever would not seek the LORD … should be put to death. See Deut. 13:6–10 and 17:2–7.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 15:16 The queen mother played an important role within the family politics of the court as an adviser of the king and teacher of the royal children. The brook Kidron, or the “Kidron Valley,” was just outside Jerusalem and was used as a refuse dump for idolatrous objects (29:16; 30:14). An inscription found at the site of Khirbet El-Qom, near modern Hebron, reads: “Blessed be Uriyahu by Yahweh and by his Asherah; from his enemies he saved him!” The inscription dates to the second half of the eighth century B.C. It reflects the constant struggle in Judah between true servants of Yahweh and those who were syncretists and idolaters.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 15:17 The high places were not taken out of Israel probably refers to those cities that had previously belonged to the northern kingdom and were then under Asa’s control (“out of Israel” is the Chronicler’s addition to 1 Kings 15:14a); in Judah, by contrast, Asa’s reforms had been much more successful (2 Chron. 14:3, 5). the heart of Asa was wholly true all his days (cf. 1 Kings 15:14). This is the overall assessment of his reign, despite the decline of his last years (see note on 2 Chron. 16:13–14).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 16:1–14 Asa’s last five years are marked by spiritual and physical decline, stemming from his unfaithful response to a military threat from the northern kingdom. He reverses the pattern of his earlier life: a covenant or treaty with Ben-hadad of Syria or Aram (vv. 2–6), in contrast to his covenant with Yahweh (15:12); he rejects the words of Hanani and mistreats him (16:7–10), in contrast to his response to Azariah (15:1–8); he fails to “seek the LORD” in his illness (16:12–13), in contrast to 14:4, 7 and 15:15.

War between Israel and Judah

As Israel and Judah battled each other to determine their permanent border, King Baasha of Israel attempted to restrict access to Judah by moving the border down to Ramah. Rather than fight with Baasha himself, King Asa of Judah bribed Ben-hadad of Syria to attack the northern border of Israel and force Baasha to withdraw from Ramah. Once Baasha withdrew, Asa carried away the building supplies of Ramah and used them to fortify Mizpah (further north) and Geba (near the pass at Michmash).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 16:1 The thirty-sixth year of the reign of Asa would be c. 876 or 875 B.C. As it stands, the text raises a problem, since Baasha had already been dead 10 years by this time (see 1 Kings 15:33; 16:8; and note on 1 Kings 15:17). One possible explanation is that the text here has suffered from a copying error. Letters from the Hebrew alphabet were originally used to denote numbers, and here (and in 2 Chron. 15:19) a scribe might have confused two similar-looking letters (י or yod for 10 and ל or lamedh for 30, letters that looked more alike in early handwritten Hebrew script than they do in modern typography). If so, then perhaps the original said that this was the “sixteenth year of the reign of Asa”—i.e., 896 or 895 B.C. Ramah lay about 5 miles (8 km) north of Jerusalem, and commanded the main road to and from the city.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 16:2–5 silver and gold. See note on 1 Kings 15:18–19. There is (or “Let there be”) a covenant. By entering into an alliance with Ben-hadad (at the expense of the temple and his palace), Asa countered the threat from Baasha, but his action reflected a lack of faith in Yahweh, who had delivered him from a greater threat (2 Chron. 16:8). Foreign alliances are condemned in 19:2; 20:35–37; 22:5; 28:16–21.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 16:7–9 The rebuke by Hanani contrasts with Azariah’s exhortation (15:2–7). Asa, who had once relied on Yahweh (14:11; 16:8), has relied instead on the king of Syria and will now face future wars (v. 9; contrast 15:15, 19). Hanani implies that Asa could have defeated Syria as well as Israel (16:7), had he trusted in God. During the reign of Asa’s son Jehoshaphat, Judah will in fact be at war with Syria (18:30). the eyes of the LORD run to and fro throughout the whole earth. God continuously watches and evaluates everyone’s inner thoughts, attitudes, and convictions (heart). Similar wording appears in Zech. 4:10.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 16:10 Asa was angry with the seer. Asa’s response is the first act of persecution of a prophet by a king recorded in the OT (see 18:26; 24:21; 25:16; 36:16). Put him in the stocks calls to mind the persecution of Jeremiah (Jer. 20:2).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 16:11–12 the Book of the Kings of Judah and Israel. See 12:15; 13:22; and note on 1 Kings 14:19. The Chronicler does not specify whether Asa’s foot disease is divine punishment for his lack of faith and his abuse of Hanani, though this may be implied. (An explicit connection between sickness and divine punishment is made in 2 Chron. 21:16–20; 26:16–23.) The primary concern here is Asa’s response: he did not seek the LORD (cf. 14:4, 7; 15:12). He is not criticized so much for seeking help from physicians (or “healers”), but for doing so apart from “the LORD, [his] healer” (Ex. 15:26), and his promises of “healing” in 2 Chron. 7:14 (see 30:20).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 16:13–14 forty-first year. Asa ruled 912–871 B.C. Funeral reports in Chronicles are often used to pass a theological judgment on a reign. a very great fire. See 21:19; Jer. 34:5. The honor shown Asa at his funeral indicates that he was held in high esteem by the people. The Chronicler also seems to have taken a generally positive view of his reign, despite the decline of his last five years (or his last 25 years; see note on 2 Chron. 16:1).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 17:1–21:1 Jehoshaphat. Jehoshaphat’s reign (871–849 B.C.) probably included three years as co-regent with Asa during his illness (see 20:31; 2 Kings 3:1; 8:16). The Chronicler’s account of his reign is much longer than that given in Kings, where Jehoshaphat plays a subordinate role to the northern kings Ahab (1 Kings 22:4–5, 29–33) and Jehoram (2 Kings 3:4–27). The Chronicler passes over the Jehoram narrative and assigns Jehoshaphat a central significance in his own right, as one who strengthens his kingdom spiritually and militarily (2 Chron. 17:1–19), organizes its system of courts (19:1–11), and demonstrates exemplary faith and leadership in the face of a terrible military threat (20:1–29). At the same time, Jehoshaphat is criticized for his alliances with the apostate northern kingdom (19:1–3; 20:37). Like his predecessors, Jehoshaphat is thus a mixture of good and bad qualities, with a preponderance of good.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 17:1–6 Jehoshaphat’s actions at the start of his reign are directed toward reforming the nation’s religious life and strengthening its military capabilities, no doubt in view of the border conflicts with the northern kingdom that marked the previous reigns. As long as he continues in this attitude of faith in God and loyalty to the ways of David (vv. 3–6), his kingdom will enjoy security and prosperity. On later occasions, however, Jehoshaphat will be drawn into alliances through marriage or military and commercial arrangements with the northern kingdom, and all of these will lead to potentially disastrous consequences.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 17:3–4 The Chronicler’s characteristic theme of “seeking God” is accompanied by obedience to God’s commandments. This is the first mention of the Baals in Chronicles. Under Ahab and his Tyrean wife Jezebel (contemporaries of Jehoshaphat), the northern kingdom adopted Canaanite Baal worship (1 Kings 16:31), leading to conflict with Elijah (1 Kings 19).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 17:5 The LORD established the kingdom in his hand, continuing the promise made to David (see 1 Chron. 17:11). God acts in and through his people’s obedience to fulfill his word.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 17:6 Reform of worship is characteristic of faithful kings in Chronicles (see 14:3, 5; 15:8; 34:4).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 17:7–9 In the third year of his reign. Probably the first year of his reign alone (870 B.C.), following a three-year co-regency with his father (see 16:12; 20:31). Jehoshaphat’s reforms were not limited to worship but also included a mission by his officials, along with a number of Levites and priests, to instruct the nation in the Law of Moses. It was God’s intention from Israel’s beginning that his people be thoroughly conversant with the law (see Deut. 6:6–9). Besides administering sacrifices, it was the duty of priests in particular to instruct the people in the law (see Lev. 10:11; Deut. 33:10; Jer. 18:18; Mal. 2:7). On the role of the Levites in teaching the law, see Neh. 8:7–9.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 17:10–11 See 1 Chron. 14:17 and 2 Chron. 14:14. The blessings of peace with the neighboring nations, and tribute from them, are presented as a consequence of the people’s faithfulness to the law. The significance of this for the Chronicler’s own relatively weak and impoverished community is clear. Arabians probably refers to tribes living to the south and southwest of Judah, close to the Philistines (see 21:16–17; 26:6–7).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 17:12–19 The description of Jehoshaphat’s military forces looks forward to the account of his alliance with Ahab in ch. 18. Large armies are regularly a sign of God’s blessing in Chronicles, but the author will show that they are no certain defense if priorities are wrong and faith is misplaced (cf. Ps. 33:16–19). The details seem to be drawn from a military census list. thousands. These may be actual numbers, or they may indicate military units (actual size uncertain); see note on 1 Chron. 12:23–37.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:1–27 The account of Jehoshaphat’s alliance with Ahab is taken with few changes from 1 Kings 22:1–40, but the additional comments in 2 Chron. 18:1–2 and in 19:1–3 give it an altogether different significance. Jehoshaphat, rather than Ahab (and the divine punishment he received for spurning the prophetic word), is the focus here. The Chronicler is concerned to show that Jehoshaphat is equally subject to the prophetic word, but that by repentance and a conscientious return to God’s way, he may escape divine wrath. As with his father Asa (see 16:3), Jehoshaphat seeks an alliance with the northern kingdom that is based not on righteous grounds but on political expediency that may draw Judah into destruction. In his account of Hezekiah’s reign (chs. 29–30), the Chronicler will indicate how a true and beneficial unity among the tribes of Israel can be achieved.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:1–2 The Chronicler’s introduction alludes to the marriage of Jehoshaphat’s son Jehoram to Ahab’s daughter Athaliah (see 21:6), some years before the battle Ahab initiated against Syria to recapture Ramoth-gilead. The statement that Jehoshaphat had great riches and honor is an indication of divine blessing on his reign and casts his alliance with Ahab into a yet more reprehensible light. The marriage between the royal houses was intended to seal peace between the kingdoms after 50 years of hostilities. Such an alliance, however, would require Jehoshaphat to “help the wicked and love those who hate the LORD” (19:2). Ahab’s great feast for Jehoshaphat and his persuasive words induced (Hb. sut) or enticed him to take part in the battle (see also 1 Chron. 21:1; 2 Chron. 32:11, 15). The same Hebrew word is found in 18:31 (“God drew them away from him”) as the positive counterbalance to the evil into which Ahab draws Jehoshaphat.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:3 Ramoth-gilead was southeast of the Sea of Galilee (probably Tell Ramith, near the modern Jordanian city of Ramtha; see Deut. 4:43). The Syrians captured it during the reign of Ben-hadad (c. 860–843 B.C.). Jehoshaphat’s words indicate his commitment to the treaty with Ahab.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:4–14 Jehoshaphat (in contrast to Ahab) is at least concerned to seek the word of the LORD concerning the advisability of the mission (vv. 4, 6, 7). Ahab’s four hundred men were called prophets (cf. also note on 1 Kings 22:6–7), but they were also government officials, probably connected with the Baal and Asherah worship that Jezebel had introduced into the northern kingdom (see 1 Kings 18:19). Their words (2 Chron. 18:5, 11) and symbolic actions (v. 10; see Jer. 27:2–7) are unequivocal and exactly what Ahab wants to hear. Jehoshaphat, however, does not recognize them as prophets of Yahweh and so persists in his request (2 Chron. 18:6). Micaiah the son of Imlah is one of the authentic prophets of Yahweh (in a kingdom where they had recently been persecuted; see 1 Kings 18:4). His initial words to Ahab (2 Chron. 18:14) were apparently spoken in an ironic tone, as Ahab’s reaction (v. 15) suggests.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:9–11 sitting at the threshing floor. See note on 1 Kings 22:10–12.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:14 Go up and triumph. See note on 1 Kings 22:15–16.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:15–22 Ahab’s insistence on hearing what Micaiah had really received from Yahweh is answered with a report of two visions. The first concerns the outcome of the battle (v. 16), while the second makes the remarkable claim that God put a lying spirit in the mouth of Ahab’s prophets (vv. 18–22); see notes on 1 Sam. 16:14 and 1 Kings 22:24. The sense here is that, as a follower of false gods (see 1 Kings 16:30–33), Ahab is fittingly deceived by their spokesmen, his prophets. God’s action has the nature of a test. The irony of the situation is that Ahab is told the truth (2 Chron. 18:16, 18–22) but does not recognize it as such, even though he had insisted that Micaiah tell him the truth (v. 15). His repudiation of Micaiah’s message and his treatment of the prophet (v. 26) indicate his contempt for the truth.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:23–27 Zedekiah … struck Micaiah on the cheek. Zedekiah had claimed to speak in the name of Yahweh (v. 10), but he shows by his violent and contemptuous conduct his scant concern for the truth. Ahab’s treatment of Micaiah foreshadows Jeremiah’s suffering (Jer. 37:14–16).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:24 you shall see … inner chamber. See note on 1 Kings 22:25.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:25 Amon … Joash. See note on 1 Kings 22:26.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:28–34 Ahab is enticed into battle, as the spirit had promised (v. 20). His decision to disguise himself, while rather cynically directing Jehoshaphat to wear his royal robes, indicates his dominant role in the alliance and perhaps also represents a contrived attempt to evade Micaiah’s word of doom. But events turn out the opposite of what Ahab intended: Jehoshaphat is delivered in battle as a consequence of his desperate prayer (v. 31b, and the LORD helped him; God drew them away from him is the Chronicler’s own addition to the text; see note on vv. 1–2), while Ahab dies from an apparently random arrow (v. 33), clear evidence of God’s sovereign direction of events.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 18:29 I will disguise myself. See note on 1 Kings 22:30.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 19:1–3 This is the Chronicler’s own addition to 1 Kings 22. Jehu the son of Hanani had ministered in the days of Baasha, king of Israel (1 Kings 16:1–3). His denunciation of Jehoshaphat for his alliance with the ungodly Ahab echoes his criticism of the wicked Baasha (1 Kings 16:7). Love here denotes not emotion but the commitment to support a treaty. God’s wrath is a matter of immense seriousness, yet may be averted or mitigated by repentance (see 2 Chron. 12:7; 32:25–26). Jehu’s acknowledgment that some good is found in Jehoshaphat recognizes his basic commitment to seek God and looks forward to his subsequent actions of repentance and reform (19:4–11).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 19:4–11 Jehoshaphat (whose name means “Yahweh judges”) institutes a judicial reform that embraces both religious and civil matters. Jehoshaphat’s primary concern is to appoint judges of integrity and impartiality, who are exhorted to perform their office in the fear of the LORD (vv. 7, 9).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 19:4 he went out again. A continuation of the religious teaching mission described in 17:7–9, this time involving the king himself. From Beersheba to the hill country of Ephraim describes the limits of Judah from south to north.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 19:5–7 Jehoshaphat’s action in appointing judges in the fortified cities of Judah and his words of admonition to them are inspired by the instructions in Deut. 16:18–17:13. Israel’s judges must act out of a sense of sacred duty (you judge not for man but for the LORD) and must reflect Yahweh’s concern for justice and impartiality.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 19:8–11 These are legal reforms for Jerusalem involving certain priests, Levites, and heads of families as judges. The Jerusalem court would have supplemented the existing local courts in the land and probably dealt with the more difficult disputed cases. The presiding justices Amariah the chief priest and Zebadiah … the governor are responsible for the interests of the temple and the crown, respectively. The Chronicler is careful to show through Jehoshaphat’s reforms that, along with inculcating personal faith and obedience to Yahweh (v. 4), the judicial system has a vital role in ensuring that the nation’s life is righteous and just, so that the people do not incur guilt and wrath.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 20:1–30 This is the Chronicler’s own material, describing a victory over Judah’s enemies in which the sovereign God alone acts for his people. In contrast to earlier battles (chs. 13; 14), Judah’s part is simply to pray for God’s help, trust in his word, worship him (20:18–22), and then watch thankfully while the Divine Warrior destroys the enemy. The narrative draws together a wide range of religious themes and practices, especially those centered on the temple, and also alludes to many earlier scriptural texts and themes. Jehoshaphat’s faith is presented here in the most positive light (although the Chronicler will go on to show a further lapse in vv. 35–37), and the rest of the nation (conceived here as a sacred assembly) similarly acts in an exemplary way. The significance of the narrative for the Chronicler’s own postexilic community seems clear: although Judah was a small and oppressed outpost of the Persian Empire, recourse to the temple in prayer and trust in the prophetic word (v. 20) was its sure defense in the most testing circumstances, including the dangers posed by its hostile neighbors (cf. Ezra 4; Nehemiah 4).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 20:1–2 After this. The invasion followed Jehoshaphat’s religious and judicial reforms (ch. 19), and so was not an instance of divine punishment (cf. 12:2) but rather an opportunity to exercise faith (see 32:1). The Moabites and Ammonites lived east of the Dead Sea. The Meunites are equated with the people of Mount Seir (20:10, 22, 23), on the southern border of Judah (see Deut. 2:1; 2 Chron. 26:7). Engedi lies on the midpoint of the Dead Sea’s western shore. great multitude. See 13:8; 14:9; 32:7. Judah was apparently outnumbered by the coalition of enemy nations.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 20:3–4 to seek the LORD. See 1 Chron. 22:19. “Seeking the LORD” was characteristic of Jehoshaphat at his best (see 2 Chron. 17:4; 18:4; 19:3). The fast was an expression of the special intensity of the people’s prayer (see Judg. 20:26; Ezra 8:21–23).

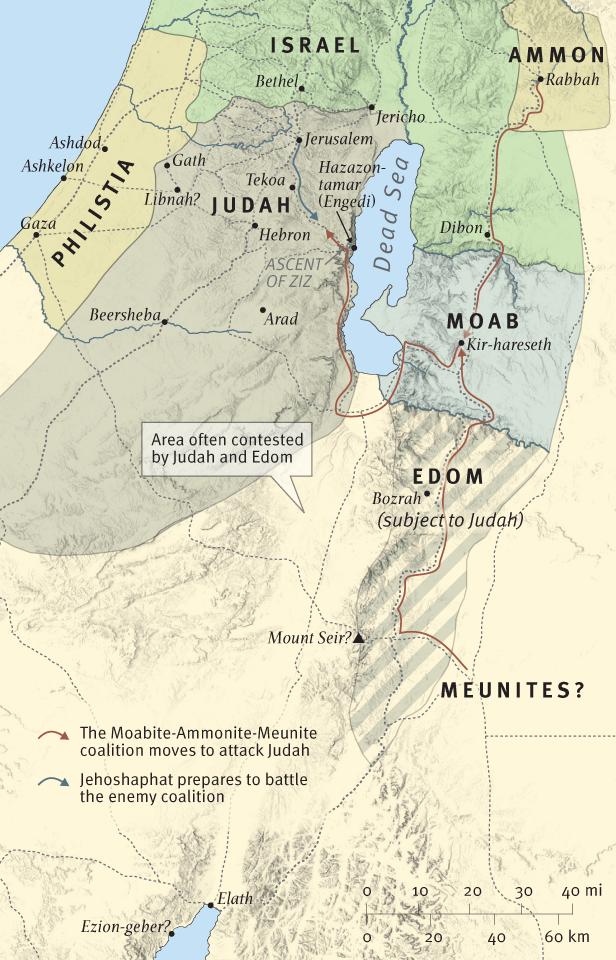

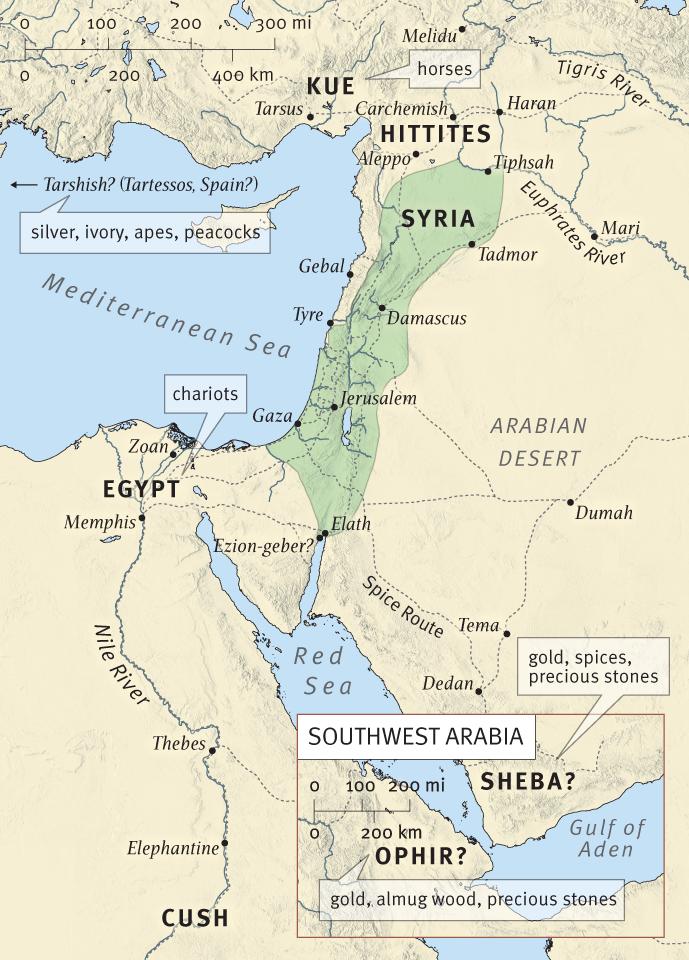

The Moabite Alliance Attacks Judah

Early in Jehoshaphat’s reign over Judah, the Moabites rebelled and gained independence from Israel. Soon after this they formed a coalition with the Ammonites and the Meunites to attack Judah. When they had crossed the Dead Sea and were making their way up the ascent of Ziz at Hazazon-tamar (Engedi), Jehoshaphat’s army prepared to meet them in battle. Before the battle could begin, however, the Lord caused the Moabites and the Ammonites to turn and attack the Meunites, and the coalition was routed.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 20:5–12 Jehoshaphat’s prayer in the house of the LORD begins by calling to mind God’s universal sovereignty (v. 6), his gift of the land to Abraham’s descendants (v. 7), and the sanctuary that testifies to God’s promise to hear his people’s prayers and save them (v. 9, a clear allusion to the circumstances envisioned in Solomon’s dedicatory prayer in 6:14–42). In the juridical style of the so-called psalms of lament (see Psalms 44; 74), Jehoshaphat then complains to God against the injustice of the invaders, acknowledging that Judah is powerless against them, but steadfastly trusting God to execute judgment on them.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 20:14–19 The prophecy of Jahaziel, given by the Spirit of the LORD in answer to Jehoshaphat’s prayer, exhorts the people not to be afraid (see v. 3) and informs them that God and not Judah will do the fighting. The people must confront the enemy, but as prayerful spectators, not combatants. Verse 17 is based very closely on Ex. 14:13–14 (“Fear not, stand firm, and see the salvation of the LORD. … The LORD will fight for you, and you only have to be silent”), pointing to a fundamental similarity between these two miraculous deliverances. Judah’s response must not be mere passivity: Tomorrow go down against them is “fighting talk,” but Judah’s part in this instance is not to take up arms but to exercise faith and to offer prayer and praise (see Eph. 6:10–18). The Levites’ ministry of leading praise appropriately concludes the great gathering for prayer.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 20:20–23 The wilderness of Tekoa lies about 12 miles (19 km) south of Jerusalem. Jehoshaphat’s call to faith is based on Isa. 7:9. Believe here means the active and obedient trust that God rewards (see Heb. 11:6), acting on the revealed word of his prophets, including Jahaziel. The singers whom Jehoshaphat appointed to go out before the army were evidently Levites (in holy attire; see 1 Chron. 16:29), declaring words from Psalm 136 as their battle song (see 1 Chron. 16:34; 2 Chron. 5:13). Their song of praise invokes God to move against their enemies (20:22; see 1 Chron. 16:35). Ambush may denote either angelic agents (see 2 Chron. 32:21) or men (see Judg. 9:25), in which case there were mutual suspicions among the coalition forces, leading to panic and their own destruction (2 Chron. 20:23; see Judg. 7:22; 1 Sam. 14:20).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 20:24–30 Verse 24 calls to mind Israel’s sight of the dead Egyptians in Ex. 14:30 (see note on 2 Chron. 20:14–19). Valley of Beracah. “Beracah” means “blessing.” There may be a recollection of this event in the prophecy in Joel 3:2, 12 (“the Valley of Jehoshaphat”). The return to Jerusalem takes the form of a triumphal procession, which ends appropriately in the temple, where the people had first sought God’s deliverance (2 Chron. 20:5). the fear of God. See 1 Chron. 14:17; 2 Chron. 14:14; 17:10; also note on Acts 9:31. God gave him rest all around. See 1 Chron. 22:9 and 2 Chron. 14:6.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 20:31–34 Adapted from 1 Kings 22:41–45 (cf. note on 1 Kings 22:43–46). Some have claimed that 2 Chron. 20:33 is inconsistent with 17:6, which says that Jehoshaphat “took the high places … out of Judah,” but both statements can be true if 17:6 refers to Jehoshaphat’s official actions and 20:33 indicates that the people’s commitment to Jehoshaphat’s reforms was not wholehearted in every place (cf. 1 Kings 22:43). The Chronicler explains why: the people had not yet set their hearts upon the God of their fathers (2 Chron. 20:33).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 20:35–37 Adapted and expanded from 1 Kings 22:48–49. Jehoshaphat repeats his error of making an alliance (this time, a commercial one) with the northern king, Ahab’s son Ahaziah. The Chronicler has added the prophetic denunciation by Eliezer.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 21:1–20 The Chronicler’s account of Jehoram’s reign is considerably expanded over the description given in 2 Kings 8:16–24. The dominant concern here, and in the accounts of his successor Ahaziah (2 Chron. 22:1–9) and the usurper Athaliah (22:10–23:21), is the disastrous influence of the house of Ahab on the Davidic dynasty and Judah. While the Chronicler’s portrayal of Jehoram is unremittingly negative, he highlights God’s promise to David (21:7) as the grounds for hope in the most troubled days. Again, the Chronicler’s own community may take this example from history and apply it to their own circumstances.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 21:1 Jehoshaphat slept with his fathers. See notes on 1 Kings 2:10 and 11:43; cf. 1 Kings 22:50.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 21:2–22:12 Jehoram and Ahaziah. God demonstrates his faithfulness to his promise to preserve David’s house, even when the spirit of Ahab is manifested in specific Davidic kings.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 21:2–6 Jehoram reigned c. 849–842 B.C., including a co-regency with his father from 853 (see 2 Kings 1:17 and note on 2 Kings 8:16). His marriage to Athaliah, the daughter of Ahab, implicated him in the evil ways of that kingdom. Once in sole possession of the throne, Jehoram demonstrated his true character through the murder of his brothers and other possible rivals (a policy that Athaliah would later repeat; see 2 Chron. 22:10). Alliance with the ungodly would bring the dynasty to the brink of destruction.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 21:6 he walked in the way of the kings of Israel. See note on 2 Kings 8:18.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 21:7 Because of the covenant that he had made with David is the Chronicler’s comment added to his source (see 1 Chron. 17:14). a lamp to him and to his sons forever. A metaphor of persistence and permanence in the darkest times, perhaps suggested by the constantly burning temple lamps (2 Chron. 13:11). As the subsequent narrative shows, the Davidic line will be brought perilously close to extinction through murder and war (21:4, 17; 22:10), until it hangs by the slenderest thread. Against all odds, the dynasty will be preserved in God’s grace, but Jehoram must still bear the punishment of his own wickedness (21:10–20; cf. notes on 2 Kings 8:19; 8:20–22).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 21:8–10 This is taken from 2 Kings 8:20–22, with the additional comment that the revolts happened because Jehoram had forsaken the LORD, the God of his fathers (see 1 Chron. 28:9). Libnah was a Judahite city on the border with Philistia.

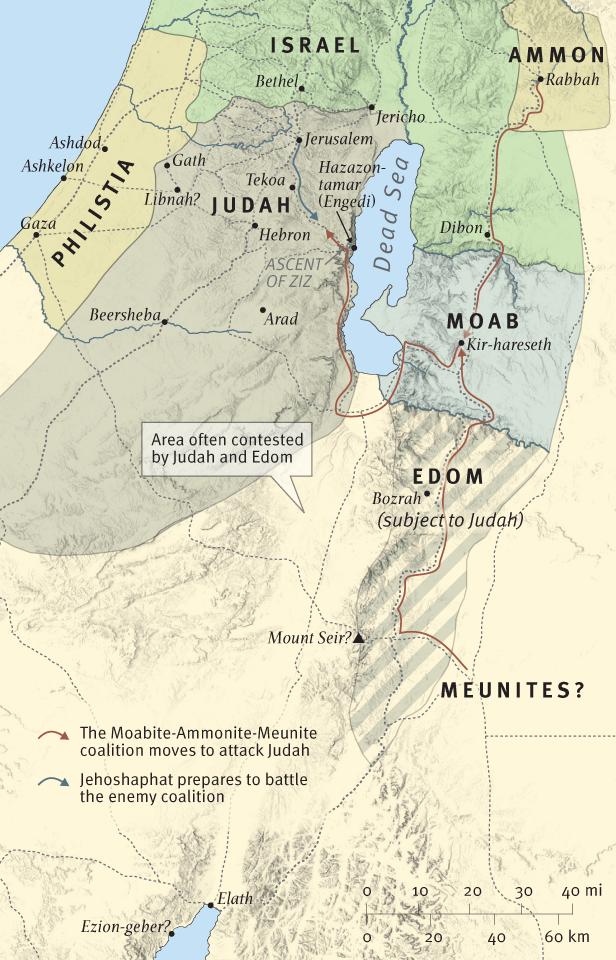

Edom and Libnah Revolt

848 B.C.

Perhaps emboldened by Moab’s rebellion from Israel a few years earlier, Edom revolted against the rule of King Jehoram (also called Joram) of Judah. Jehoram led his army to Edom to put down the rebellion, but his efforts failed. At the same time, the western priestly town of Libnah revolted against Judah, apparently because of Jehoram’s idolatrous practices. Philistines and Arabians also attacked Judah and plundered the royal palace, carrying away all its possessions and many of Jehoram’s wives and sons.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 21:11–20 This is the Chronicler’s own material. In contrast to his father Jehoshaphat, who sought to suppress the heathenish high places (17:6), Jehoram actually promotes their construction, probably as a consequence of his marriage alliance with the northern kingdom. Whoredom was a traditional term among the prophets for apostasy into idolatry (see Ezek. 16:16; Hos. 4:17–18). As always in Chronicles, the errant king is subject to prophetic rebuke; here, it takes the singular form of a letter … from Elijah the prophet. The last years of Elijah’s ministry overlapped with the beginning of Jehoram’s reign (2 Kings 1:17). As he had opposed Ahab (1 Kings 17–18), Elijah now condemns Ahab’s spiritual successor (2 Chron. 21:6, 13) for leading Judah into idolatry and for murdering his own brothers. The destruction of Jehoram’s own family is decreed, to be fulfilled at the hands of the Philistines and of the Arabians, while Jehoram himself is condemned to a fatal bowel disease. On disease as divine punishment, see 16:12; 26:19–21; and note on John 9:2. Jehoram’s exclusion from burial in the tombs of the kings is a final indication that he belonged to the ways of Ahab rather than David.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 22:1–9 The Chronicler’s account of Ahaziah’s brief reign (842–841 B.C.) is adapted from 2 Kings 8:24–29; 9:21, 28; 10:13–14. The main interest lies with the malignant influence of the house of Ahab over the young and ineffectual king. Ahaziah’s mother Athaliah is a daughter of Ahab (see 2 Chron. 18:1; 22:2) and his counselor in doing wickedly (the Chronicler’s addition to the text). As queen mother, she held an official position in the court as a royal adviser. Her role was supplemented by other officials from the house of Ahab, who were Ahaziah’s counselors, to his undoing (v. 4b, the Chronicler’s addition).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 22:5–9 Ahaziah’s decision to join Jehoram (a variant spelling of Joram), king of Israel, in his bid to recapture Ramoth-gilead from Hazael, king of Syria, comes at the behest of his “Ahabite” counselors. Some years previously, Jehoshaphat had allied himself with Joram’s father Ahab in an identical mission, ending in Ahab’s death (ch. 18). Joram was wounded at Ramoth-gilead, and withdrew to Jezreel to recuperate. Ahaziah came to visit his ally there, only to fall into the hands of Jehu, Joram’s commander, whom God had chosen to destroy the house of Ahab (see 1 Kings 19:15–17). Jehu’s violent coup is described in detail in 2 Kings 9:1–28. The Chronicler assumes his readers’ acquaintance with this narrative and focuses instead on Ahaziah’s fate, which he remarks was ordained by God (see 2 Chron. 10:15; 24:20). Ahaziah falls under the same judgment as the house of Ahab, insofar as he followed the ways of that apostate dynasty.

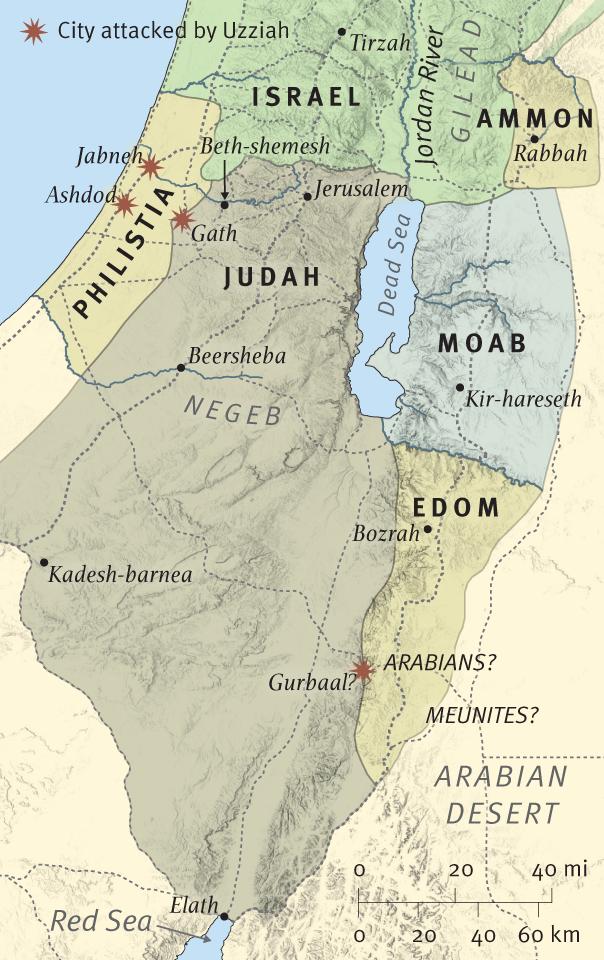

Jehu Executes Judgment

841 B.C.

During a battle with Syria at Ramoth-gilead, King Joram (also called Jehoram) of Israel was wounded and went to Jezreel to recover. While he was there, Jehu, one of Joram’s commanders, came from Ramoth-gilead to carry out the Lord’s judgment on Joram’s family. When Joram and King Ahaziah of Judah went out in their chariots to meet Jehu, Jehu mortally wounded Joram with an arrow and chased Ahaziah to Beth-haggan, where he wounded him as well. It appears that Ahaziah then fled to Megiddo, where he died (2 Kings 9:27).

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 22:9 In contrast to Joram, whose body was left exposed on Naboth’s field (2 Kings 9:26), Ahaziah is granted a decent burial out of respect for his grandfather Jehoshaphat.

2 CHRONICLES—NOTE ON 22:10–12 Athaliah is nothing more than a violent usurper who attempts to secure the throne for herself by massacring rivals from the royal family, including her own relatives. Like Jehoram (21:4), she brings the Davidic dynasty to the brink of destruction. But while she rules the land for six years (probably 841–835 B.C.), she does so without legitimacy: no statements at the beginning or end of her rule make her reign official. The contrasting figure to her is Ahaziah’s sister Jehoshabeath, who courageously conceals the infant heir Joash throughout those years. The Chronicler adds the comment that Jehoshabeath is also the wife of Jehoiada the high priest, which helps explain how the child could be concealed in the temple buildings throughout Athaliah’s rule. Mention of Jehoiada here also prepares the way for the following account of Athaliah’s overthrow by the high priest.