Study Notes for 2 Kings

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 1:1–18 The Death of Ahaziah. Like his father Ahab, Ahaziah is destined to meet Elijah. The occasion for their confrontation is an injury sustained by the king when falling out the window of his upper chamber in Samaria.

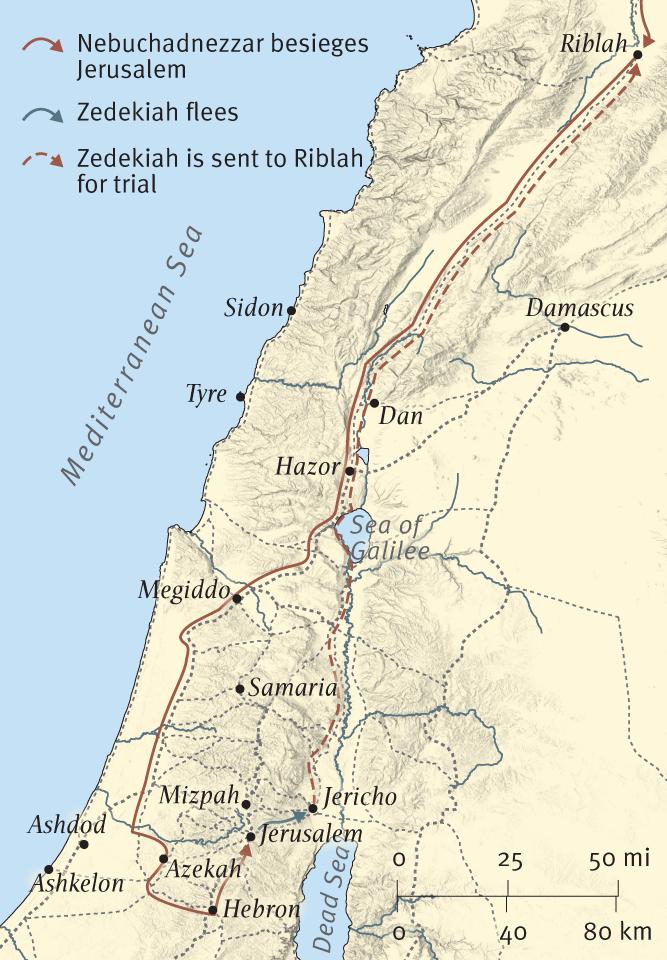

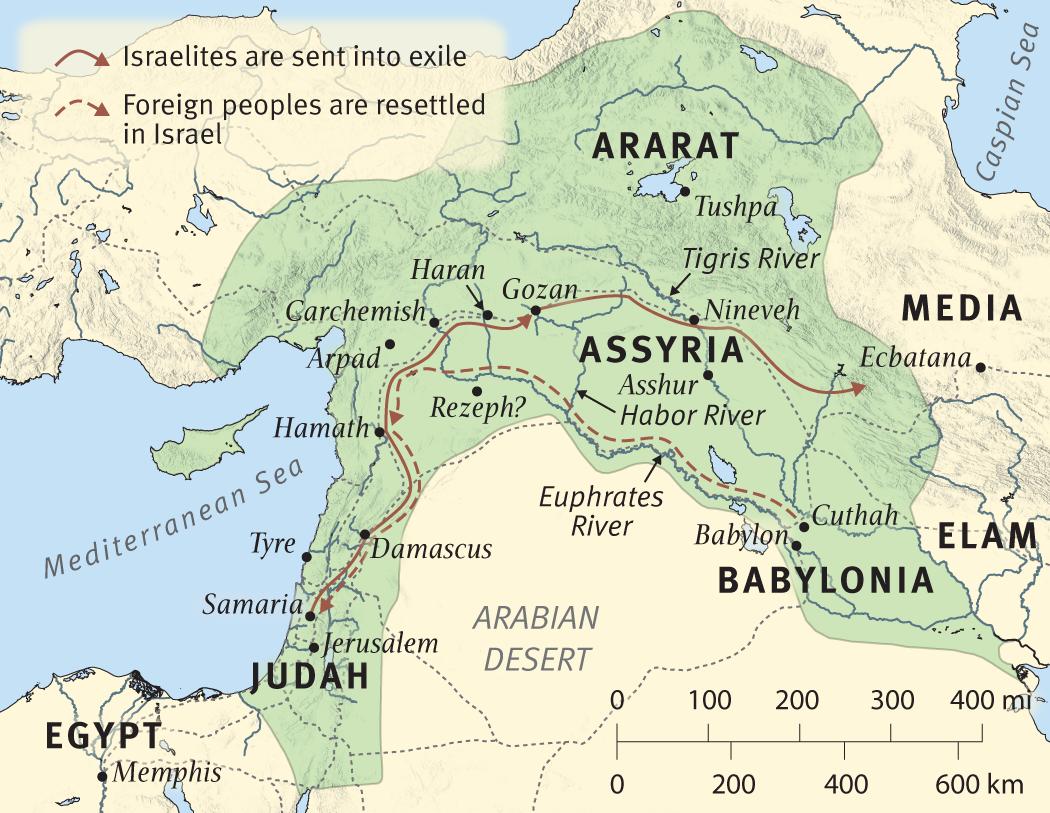

Israel and Judah in 2 Kings

c. 853 B.C.

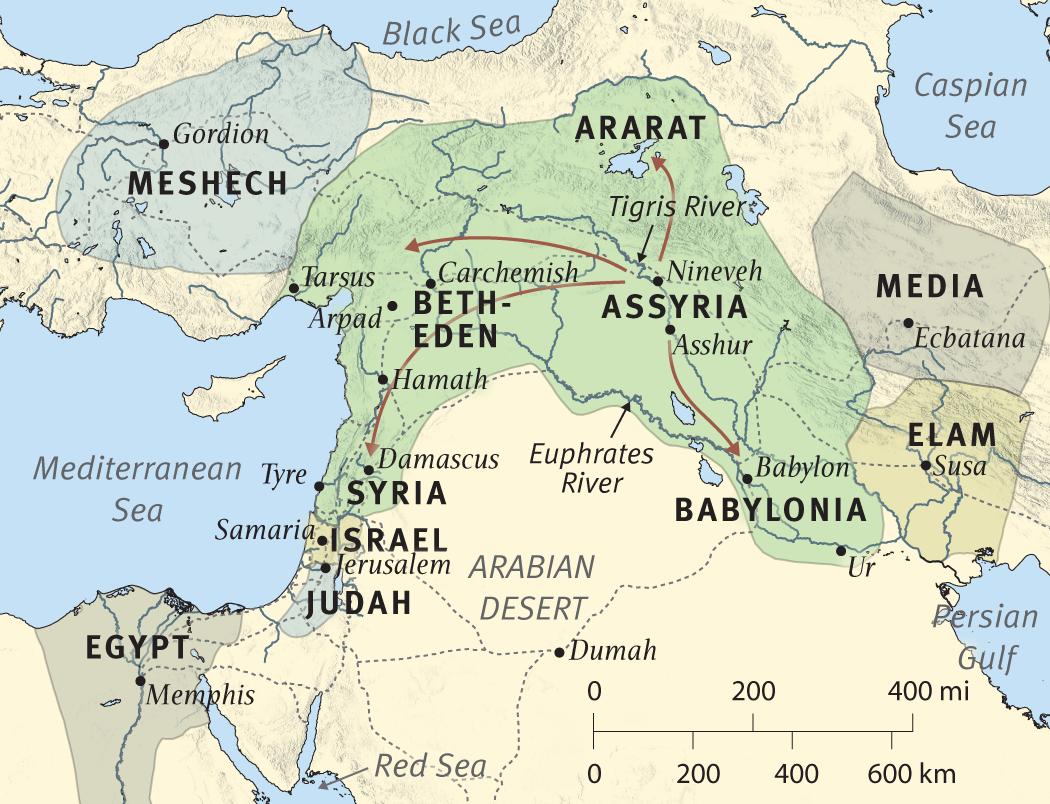

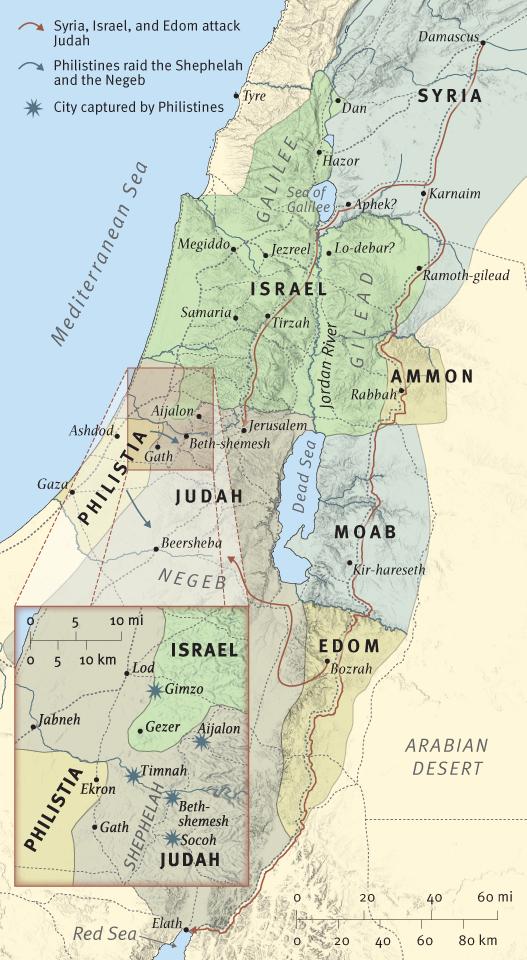

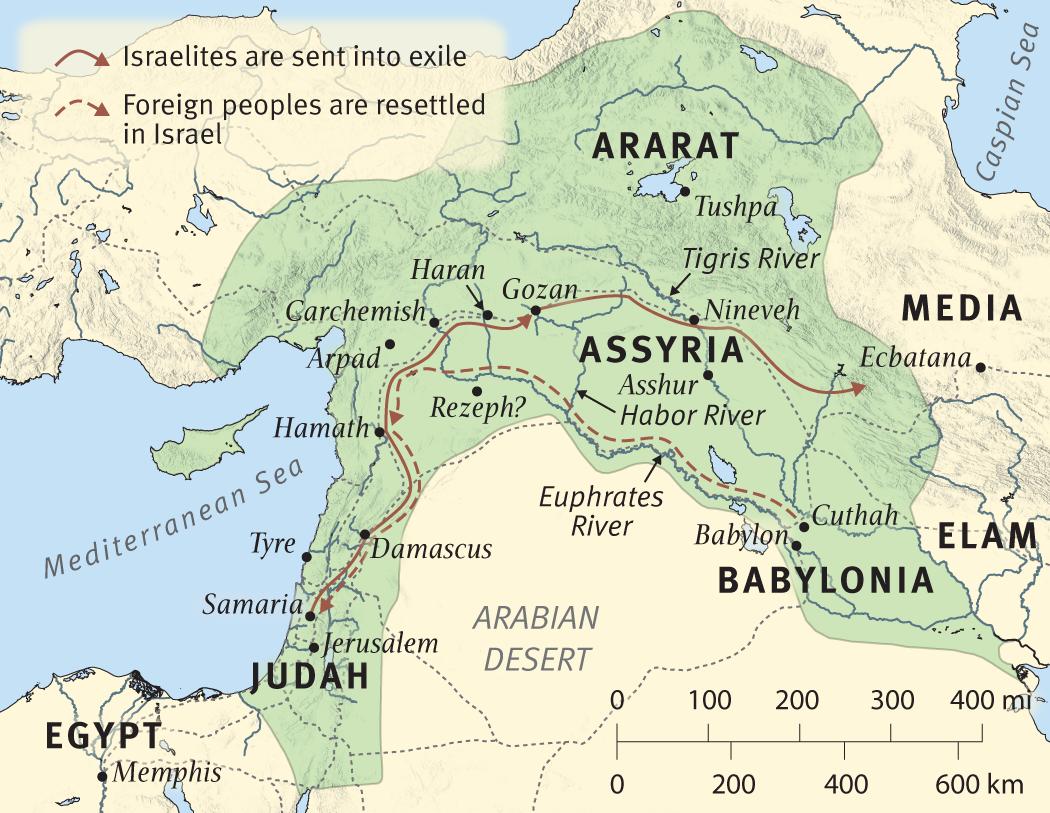

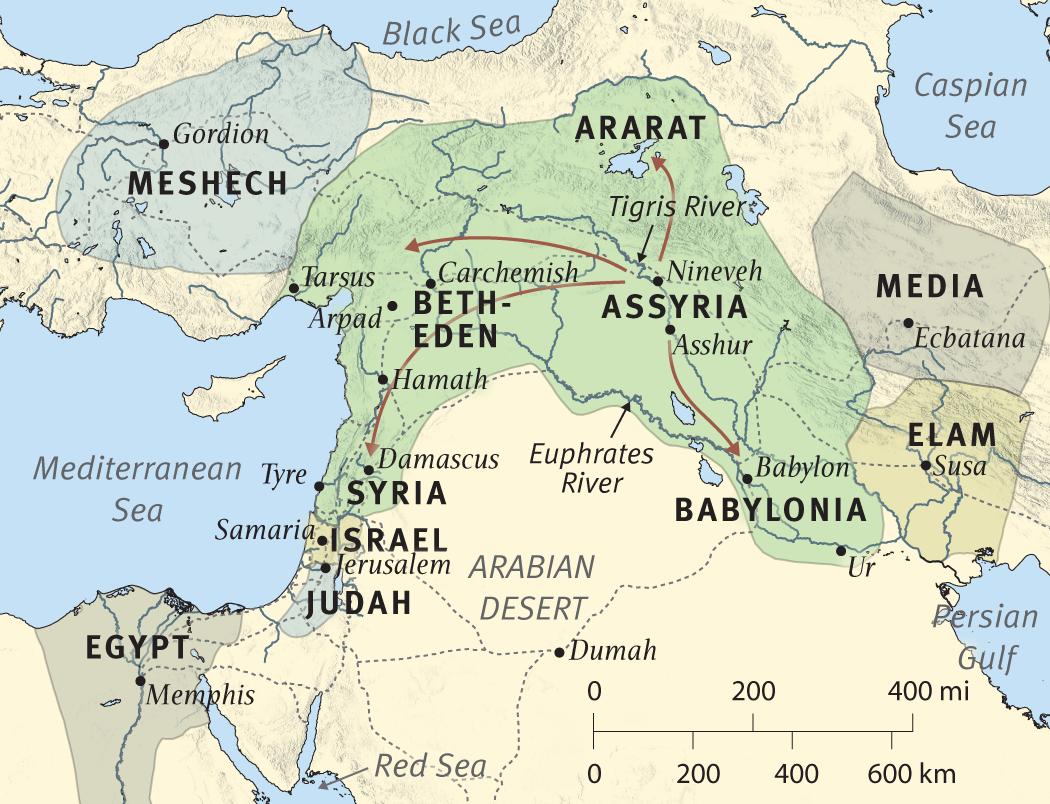

The book of 2 Kings recounts events in Israel and Judah from the death of Ahab to the exile of Israel and Judah. The complex and shifting political setting for the book involves Israel, Judah, Syria, Ammon, Moab, Edom, and Philistia, as well as Egypt, Assyria, Babylonia, and other kingdoms far beyond Israel’s borders.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 1:1 After the death of Ahab, Moab rebelled. More on this rebellion will be related in ch. 3. It is mentioned here to make the point that, whereas the relatively righteous Jehoshaphat maintained his control of other nations (Edom, 1 Kings 22:47), Ahab’s Baal-worshiping son did not. An inscribed stone monument of King Mesha of Moab (commonly known as the “Mesha Inscription” or “Moabite Stone”) probably refers to this same Moabite rebellion (see note on 2 Kings 3:4–27).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 1:2 Samaria was the capital of the northern kingdom of Israel from the time of Omri (1 Kings 16:24) until the fall of the northern kingdom under Hoshea (2 Kings 17). Ekron was an important Philistine city about 25 miles (40 km) west of Jerusalem. Baal-zebub means “lord of the flies” and is probably a deliberate Hebrew corruption of “Baal-zebul” (“Baal the exalted” or “Baal/master of the height” or possibly “Baal/master of the dwelling”; cf. note on Matt. 10:25), intended to express the authors’ scorn of or hostility toward this “deity.” Ahaziah looks for help from this local manifestation of the god Baal (see 1 Kings 16:31–33), perhaps regarding the Ekronite version of the deity as especially powerful.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 1:3–4 In a scene reminiscent of the opening verses of 1 Kings 19, the Lord sends an angel (Hb. mal’ak) in response to other people’s sending messengers (also Hb. mal’ak, 2 Kings 1:2).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 1:8 He wore a garment of hair. The Hebrew is lit., “He was a man who was a lord/owner of hair”—possibly a play on words with “lord of the flies” in v. 2. The “hair” could be either animal or human, which is why translations of the Hebrew have varied between “garment of hair” and “hairy” (i.e., long-haired, bearded).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 1:9–12 the king sent to him a captain of fifty men. The odds would seem good for 50 soldiers to be able to bring back one man, but the Lord is on Elijah’s side. This is not the first time a negative oracle addressed to a king elicits an attempt to capture the prophet who delivered it (cf. 1 Kings 13:1–7; 17:1–4; 18:9–10; also 1 Sam. 19:19–24). The prophetic word, however, cannot be brought under human control, and the God of Mount Carmel sends fire from heaven to underline this fact (cf. 1 Kings 18:38). Two “lords” vie for worship throughout the Elijah story (Baal and Yahweh), both of them identified with fire—and Ahaziah has chosen the wrong one. Here 100 soldiers die as a result of Ahaziah’s choice to turn from God, again showing that the sins of leaders often lead to tragic consequences for those whom they lead (see note on 2 Sam. 24:17).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 1:13–18 third captain. This man shows Elijah the respect he is due as a prophet of the Lord and escapes with his life. On the other hand, Ahaziah has his desired meeting with Elijah, and it changes nothing; the king dies. His brother Jehoram succeeds him (v. 17; cf. 3:1). On the Chronicles of the Kings, see note on 1 Kings 14:19.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:1–10:36 Elisha and Israel. Elijah’s days have been numbered since 1 Kings 19:15–18, and particularly God’s instructions there about Elisha. The end of the war with Baal worship will not come about until Elisha has succeeded Elijah, and Hazael and Jehu have appeared. This section of 1–2 Kings now tells of these events.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:1–25 Elijah Gives Way to Elisha. The prophetic mantle passes from Elijah to Elisha. As Elijah has called fire down from heaven in ch. 1, so he now will be lifted in fire up to heaven, and Elisha will be authenticated as his successor.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:1 The idea of going up to heaven at the end of an earthly life was not common in ancient Israel. The OT more characteristically speaks of the deceased’s “going down” to Sheol, the world of the dead (e.g., Job 7:9; Isa. 57:9; see note on 1 Sam. 2:6). It was the fate even of mighty heroes of the Hebrew tradition to be “gathered to their people” in this way (e.g., Gen. 25:7–8; 1 Kings 2:10). Elijah represents a remarkable exception to this way of speaking (see also Enoch in Gen. 5:24; cf. Heb. 11:5). This does not mean that the OT faithful had no fellowship with God after they died, but only that this idea is seldom made explicit in the OT (but see indications of hope for continuing fellowship with God after death in Ps. 16:10–11; 17:15; 23:6; 115:17–18; Eccles. 12:7; and certainly here in 2 Kings 2:11). In the NT, Jesus implied that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were alive and in God’s presence (Matt. 22:32); Moses and Elijah appeared talking with Jesus in Matt. 17:3; and the parable of the rich man and Lazarus implied fellowship in Abraham’s presence immediately after death (Luke 16:22–25). Extrabiblical texts underline the unusual nature, in the ancient Near Eastern context, of any idea that mortals can enter and remain in heaven. The best known of these is the Akkadian myth of Adapa, the son of Ea, who visits heaven and almost obtains eternal life, but is compelled in the end to return to earth. It is not clear whether the Lord has any reason for sending Elijah from Gilgal to Bethel, and then on to Jericho (2 Kings 2:2–4); but all three cities appear in 2 Kings as locations of prophetic communities (“sons of the prophets”; see note on v. 3; also v. 5; 4:38), and Elijah is probably their leader (as Elisha is later).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:2 Bethel is identified with Jeroboam’s apostasy in 1 Kings 12–13. Please stay here. It is never made clear why Elijah, in the course of his roundabout journey, keeps trying to get Elisha to remain behind on the very day that the prophetic succession is to take place (“today the LORD will take away your master”), but it is probably a testing of Elisha’s mettle as the professed disciple and designated successor to Elijah. This may provide further evidence of Elijah’s reluctance to fully embrace God’s plans for the future (see 1 Kings 19:13–21). Elijah affirms a little later that Elisha can receive Elijah’s spiritual power only if he sees him when he is taken away by God (2 Kings 2:9–10). The prophets in the meantime are to “keep quiet”; it is disrespectful to speak of Elijah’s passing while he is still around.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:3 The sons of the prophets are not their physical descendants but groups of prophets usually affiliated with a more prominent prophet (cf. 1 Sam. 10:5; 19:20; 1 Kings 18:4; 2 Kings 4:1, 38; 6:1; 9:1). (The phrase “sons of” can mean “members of a guild of”; cf. “the sons of the gatekeepers” in Ezra 2:42.) Though groups of false prophets also exist (e.g., 1 Kings 22:6), the prophetic groups associated with true prophets such as Samuel and Elijah are never viewed as false prophets but as servants of God, and therefore they must have received special revelations from God (which is the requirement for a true prophet: Deut. 18:18, 20; Jer. 14:14; Ezek. 13:1–3), though none of their prophecies are recorded in Scripture. In this text God has revealed to them that today the LORD will take away Elijah.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:4–5 Jericho was in the Jordan Valley about 10 miles (16 km) to the northwest of the Dead Sea and is best known as the city that the Israelites first conquered in Canaan.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:6–8 The Jordan River runs along a short stretch of a geological fault that starts in the north in Syria and extends southward into Africa. This scene of the crossing of the Jordan is reminiscent of Moses at the Red Sea, where the people also go over on dry land (Ex. 14:15–31, esp. vv. 21–22). Later in the chapter, Elisha proves that he is Joshua to Elijah’s Moses by recrossing the river (see note on 2 Kings 2:14).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:9 Elisha requests of Elijah what an eldest son would expect of a father in Israel: a double portion of the inheritance (see Deut. 21:15–17). In this case, however, the inheritance is not land but spiritual power: Elisha has already left behind him normal life and the normal rules of inheritance (cf. 1 Kings 19:19–21).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:10 You have asked a hard thing. It is not clear how Elisha’s request can be hard, given that Elisha is ordained by God to succeed Elijah as a Spirit-empowered prophet. Is Elijah simply looking for difficulties? But cf. note on v. 2.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:11–13 chariots of fire and horses of fire. The divine army, last encountered waging war on Ahab (1 Kings 22:1–38), has come for Elijah; Elisha sees it, as he will see it again in 2 Kings 6:8–23. In biblical tradition, both chariotry and fire have strong associations with God’s self-disclosure. Both images come together in the most common natural form of divine appearing (“theophany”) in the OT: the thunderstorm—the storm cloud representing the divine chariot or throne (Ezekiel 1; Hab. 3:8) and the fiery lightning bolts representing the divine weapons (Ps. 18:14; Hab. 3:11). In response to this particular theophany, Elisha took hold of his own clothes and tore them in two pieces. This is perhaps part of a mourning ritual (cf. Gen. 37:34; 2 Sam. 13:31; Isa. 37:1), but it is also suggestive of leaving his old life behind, as he picks up instead the cloak of Elijah (used in 1 Kings 19:19–21 to symbolize Elisha’s prophetic call).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:14 the water was parted … and Elisha went over. The Spirit who empowered Elijah has now come upon Elisha, and miracles immediately follow. As Elijah’s true successor, Elisha is able to repeat Elijah’s action in parting the waters (v. 8). There is also a kind of parallel in the life of Joshua, for Joshua also crossed the Jordan in Joshua 3 and entered the land of Israel near Jericho, “repeating” Moses’ action in parting the waters (Exodus 14).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:15 they came to meet him and bowed. The roots of the Jericho community’s allegiance to Elisha lie in their conviction that he is Elijah’s bona fide successor (The spirit of Elijah rests on Elisha).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:16 Please let them go and seek your master. The sons of the prophets seem to understand that the prophetic succession has taken place, but do not fully understand what has happened. Standing at a distance (v. 7), they have seen the fire and the whirlwind (v. 11), but they have not perceived what was happening in the storm’s midst. They wonder, therefore, whether the Spirit of the LORD has not simply caught Elijah up and cast him upon some mountain or into some valley; and they at least want to retrieve Elijah’s body for burial (cf. 1 Sam. 31:11–13).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:19–22 the water is bad, and the land is unfruitful. This is the first of two stories that further authenticate Elisha as Elijah’s prophetic successor, a man able both to bless and to curse in the Lord’s name (cf. Moses in Deuteronomy 28). Jericho was in an area ideal for settlement because of the presence of the perennial spring ‘Ain es-Sultan, which irrigated the fertile land around it. This story, however, tells of contamination of the water supply (the rebuilding of the city having taken place under the shadow of Joshua’s curse; Josh. 6:26; 1 Kings 16:34). The remedy offered by the new Joshua (Elisha), who has just crossed the Jordan, involves a new bowl and salt. New items, being uncontaminated, were customarily employed in rituals in the ancient Near East (e.g., Judg. 16:11; 1 Kings 11:29). Elsewhere in the OT, salt is associated with the covenant and is included as part of offerings made to the Lord (see “salt of the covenant” in Lev. 2:13; cf. Num. 18:19), as well as being used in other specific rituals (Judg. 9:45; Ezek. 16:4). The use of salt here is likewise symbolic, for by itself a tiny bowl of salt would have no effect on a constantly flowing spring. The healing of the water was therefore accomplished by supernatural means: Thus says the LORD, I have healed this water.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:23–24 jeered at him. The focal point for Israel’s apostasy was Bethel (see 1 Kings 12:25–13:34). Therefore, it is no surprise to find young people from this city adopting a disrespectful attitude toward a prophet of the Lord, and to treat a prophet with disrespect is to treat God himself with disrespect. The reference to the baldhead is not clear, but Elisha might have already been so bald by nature that to youthful eyes he looked grotesque; or perhaps some prophets, like later Christian monks, shaved their heads as a mark of their vocation. he cursed them. … And two she-bears … tore forty-two of the boys. Though this judgment may at first seem harsh, the group must have included over 50 boys old enough to be out running in a pack, and so they constituted something of a physical threat to Elisha. The authors of Kings regularly show that contempt toward divinely called prophets is disastrous for God’s people.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 2:25 The succession narrative now complete, Elisha ends his journey with a visit to Mount Carmel—the scene of Elijah’s great victory—and a return to Samaria to continue the war against Baal worship.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:1–27 Elisha and the Conquest of Moab. One expects that Elisha, as Elijah’s successor, will also be involved in politics, and in this story he is consulted about a military campaign. The narrative noticeably echoes 1 Kings 22:1–28.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:2 not like his father and mother. As one of a number of surprises in ch. 3, Jehoram son of Ahab is distanced from the rest of his family by the way in which his reign is described. The implication is that while he tolerated the Baal cult (cf. v. 13; 9:22; 10:18–28), he did not himself worship Baal (he removed Baal’s pillar from the temple; see 1 Kings 14:23).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:4–27 The Moabite Stone (currently in the Louvre Museum in Paris) is a stele set up by Mesha, king of Moab, to commemorate his achievements. Mesha makes his version of a war fought with Israel in 850 B.C. prominent; the Israelite account appears in this chapter. The two accounts differ: Mesha emphasizes his victories over Israel, and the biblical writer emphasizes Israel’s successful counterattacks.

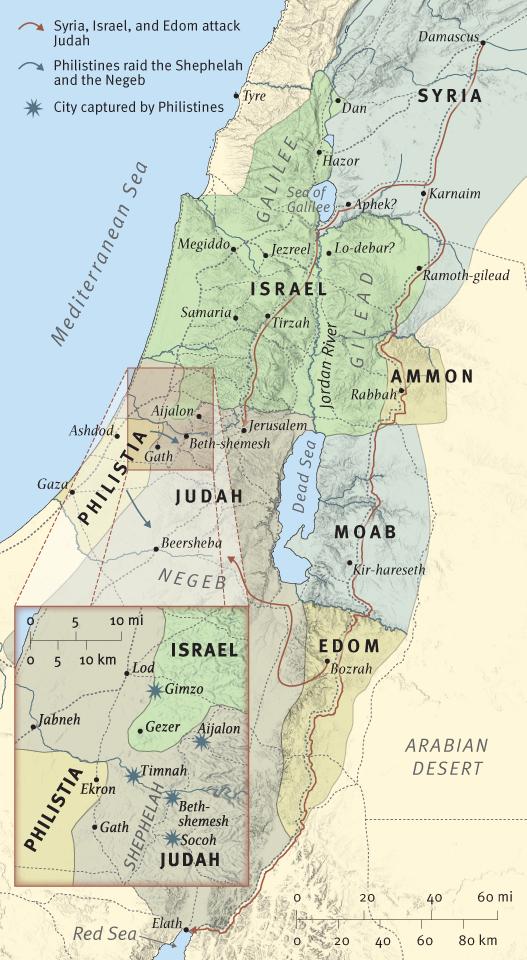

Moab, Edom, and Libnah Revolt

853, 848 B.C.

When King Ahab of Israel died, King Mesha of Moab seized the opportunity to throw off the yoke of tribute imposed on his people by David. Israel, Judah, and Edom (which still belonged to Judah) joined forces to attack Moab, but their efforts failed to re-subdue the nation. Perhaps emboldened by Moab’s success, Edom later revolted against the rule of King Jehoram (also called Joram) of Judah. At the same time, the western town of Libnah also revolted against Judah.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:4–5 Mesha was a ninth-century king of Moab, the successor of his father Chemosh-yatti according to the Moabite Stone (see notes on 1:1; 3:4–27). He began his reign under the dominion of the Israelite house of Omri, and was required to pay his overlord “tribute” (i.e., taxation) in the form of a percentage of his agricultural produce (lambs and wool), which is understandable given the importance of sheep in the economy of ancient Palestine. After the death of Ahab, Mesha took advantage of the new situation and rebelled, inciting Ahab’s son Jehoram to launch the military campaign described in this chapter (see map).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:7–9 he went and sent word to Jehoshaphat. Like his father before him, Jehoram seeks help from his southern neighbor Jehoshaphat, whose initial response is recognizable from 1 Kings 22:4: I am as you are, my people as your people, my horses as your horses. Missing on this occasion, however, is any desire on Jehoshaphat’s part to discover the counsel of the Lord before going off to war (contrast 1 Kings 22:5); here he moves directly from agreement to tactics (2 Kings 3:8), and from tactics to action (v. 9). This is surprising. The tactics involve attacking Moab from the south, through the wilderness of Edom, rather than from the north. This is possible because Edom is under Judean rule (1 Kings 22:47) and her king is Jehoshaphat’s deputy rather than an independent monarch. The action involves a march in which the combined armies get lost, caught in a circuitous march. Unsurprisingly, a military venture undertaken without prophetic advice faces disaster.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:11–14 Is there no prophet of the LORD here? Jehoshaphat’s memory suddenly returns, and he asks the right question (cf. 1 Kings 22:7). Elisha, the one who poured water on the hands of Elijah (probably a reference to Elisha’s role as Elijah’s servant), is found to be in their midst. Unimpressed as he is with Jehoram’s piety, Elisha agrees to help because of righteous (albeit forgetful) Jehoshaphat’s presence in the alliance.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:15–19 bring me a musician. Music plays a part in Elisha’s attainment of the prophetic state in which he utters his prophecy (cf. 1 Sam. 10:5–11; note on 1 Sam. 10:5). The immediate crisis (no water, 2 Kings 3:9) is to be dealt with by miracle, as the nearby streambed shall be filled with water from an unspecified and unexpected source (neither wind nor rain). God will further grant the alliance a comprehensive victory over Moab. They will attack every fortified city and every choice city (or perhaps “major town”), devastating the land as they move through it. Deuteronomy 20:19–20 prohibits this kind of destruction in normal cases, but here it appears that Elisha portrays the Moabites as a nation to be given over to desolation (like the cities of Canaan in Deut. 20:16–18), rather than simply subjugated.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:20–24 Events begin to unfold in line with Elisha’s prophecy. Water mysteriously flows from the direction of Edom (Hb. ’Edom), fooling the Moabites into thinking the allies have slaughtered each other because in the morning sunlight the water appears red (Hb. ’adummim) as blood (Hb. dam); notice the play on words with ’Edom. Their reckless advance on the Israelite camp is met with force.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:25 The combined armies act out Elisha’s words (cf. v. 19) point by point, attacking all the Moabite cities including Kir-hareseth, strategically situated on a rocky hill overlooking the Dead Sea about 17 miles (27 km) south of the Arnon Gorge and 11 miles (18 km) east of the Dead Sea.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 3:27 Facing defeat by Israel, Mesha offered his son as burnt offering on the wall. As a consequence, there came great wrath (Hb. qetsep) against Israel. This is not to be understood as divine anger, because on the one hand the biblical authors did not regard the Moabite god Chemosh as a real god (1 Kings 11:7), and on the other hand Israel’s God would surely not have acted on Moab’s behalf as a result of a ritual practice that was abhorrent to him (cf. 2 Kings 16:3; 17:17; 21:6). It seems, instead, that this “great wrath” is human wrath (as on both other occasions in Kings when qetsep appears, 5:11; 13:19): Mesha’s troops respond to his desperate act with an anger that carries them to victory against the odds.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:1–44 Elisha’s Miracles. Both Elijah and Elisha are now associated with the God who provides water at will (cf. 1 Kings 18), whether by ordinary means (wind and rain, 1 Kings 18:45) or not (neither wind nor rain, 2 Kings 3:17). A number of further miracles serve in the same way as a reminder of Elijah.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:1–7 the creditor has come to take my two children to be his slaves. Indebtedness was a common problem throughout the ancient Near East and could lead to the loss of property, home, fields, and ultimately the freedom of the debtor (cf. Neh. 5:4–5; Isa. 50:1; Amos 2:6; 8:6). Persons and property ending up in the hands of creditors could often be redeemed (cf. Ruth 4:1–12; Jer. 32:6–15), and among the responsibilities of the “kinsman-redeemer” in an extended Israelite family was the maintenance or redemption of the person or dependents of a kinsman in debt (Lev. 25:35–55). In the apparent absence of a true kinsman for the widow in this story, Elisha as the leader of the prophetic communities effectively takes on this kind of role for her. The proceeds from the sale of the multiplied oil (cf. 1 Kings 17:7–16) will leave her and her sons sufficient money to live on even after she has paid off her debts.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:10 a small room on the roof. Roofs in ancient Israel were typically flat and served as important areas in the life of the family (cf. Josh. 2:6–8; 2 Sam. 11:2; 2 Kings 23:12; Jer. 19:13), providing among other things temporary guest accommodations (cf. 1 Sam. 9:26; 2 Sam. 16:22; 1 Kings 17:17–24). The structure in question here, however, is more permanent (it has walls).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:13 a word spoken on your behalf. Elisha offers the Shunammite woman benefits, through his patronage, from the king or the commander of the army—two of the most powerful people in the land. She has no need of their help, however, because she is wealthy (v. 8) and, living among her own kinfolk (my own people), has their support and protection. She is not vulnerable like the widow in vv. 1–7.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:23 The implication to be drawn from the husband’s response is that it was customary in Israel to consult prophets only on particular rest days—the new moon, marking the beginning of each month, and the Sabbath (cf. 1 Sam. 20:5–34; Hos. 2:11; Amos 8:5). The practice of celebrating on the first of the month had ancient roots; the new moon was already one of the principal lunar festivals in Old Babylonian times. This woman’s business, however, will not wait. All is not really well, but she does not want either her husband or Gehazi (2 Kings 4:26) getting in her way as she seeks Elisha’s help.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:27 the LORD has hidden it from me. Elisha had not foreseen this happening. Prophets are not omniscient, but depend always on God’s revelation.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:29 Tie up your garment. As the woman had arrived at Carmel in great haste (v. 24), so Elisha sends Gehazi back to Shunem in similar haste, his garment hitched up so that he can run (cf. 1 Kings 18:46).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:30–31 I will not leave you. The woman is not willing to accept Elisha’s plan to resurrect the boy from a distance by means of his staff; she wants his personal attention, which in the end does in fact prove crucial. Only his own prayer and mysterious actions succeed in bringing the boy back to life (cf. 1 Kings 17:19–23).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:34 Elisha’s actions vividly picture God restoring breath to the child (putting his mouth on his mouth), as well as sight (his eyes) and strength (his hands). As Elisha stretched himself upon him, it portrayed the Spirit of God who, through Elisha, was being imparted to the child to give him life.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:38 famine in the land. Elisha’s third miracle (see note on vv. 1–44) is reminiscent of the healing of the water of Jericho (2:19–22). Famine is the context in which the whole succeeding narrative up to ch. 8 takes place (see 8:1), although a general state of famine does not imply an absolute absence of food (see, e.g., 4:42–44).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:40–41 death in the pot. As with the salt thrown into the water at Jericho (2:21), the flour used by Elisha is a visible sign of the Lord’s power working through Elisha.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 4:42–44 bread of the firstfruits. The final miracle of the chapter (see note on vv. 1–44) also concerns provision for the people who depend on Elisha. A limited amount of food is once again multiplied (cf. vv. 1–7), in face of the incomprehension of the servant, so that it not only provides immediate needs but also produces a surplus. It is the final demonstration in the chapter that the God of Elisha heals, provides, and brings life from death.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:1–27 A Syrian Is Healed. The account of Elisha’s miracles continues with the story that again picks up themes from the Elijah story: the Lord is seen to be God, not only of Israelites, but also of foreigners (1 Kings 17:17–24), and is in fact acknowledged as the only real God there is (1 Kings 18:20–40).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:1 the LORD had given victory to Syria. It was common throughout the ancient Near East for peoples to claim that their gods had given them victory in battle, but the claim here is of a distinctively monotheistic kind; here (as always in the Bible) Israel’s God is responsible for victory or defeat in battles, no matter which gods may be worshiped by the victorious or defeated peoples (cf. Dan. 1:1–2). The vanquished here are not specified but may have included Israel, which was defeated at Ramoth-gilead in 1 Kings 22:29–36. The general by whom God had given the Syrians victory on this occasion was himself a leper (Hb. metsora‘); he suffered from some kind of disfigurement of the skin (but not necessarily what is known by modern people as “leprosy”; see note on Luke 5:12), rendering him ritually unclean from an Israelite point of view (cf. Leviticus 13–14; Num. 12:1–15; 2 Sam. 3:28–29).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:5–7 a letter to the king of Israel. An uneasy truce appears to be in force between Syria and Israel. There is sufficient tension, however, for the king of Israel to be concerned that the king of Syria is seeking a quarrel in asking him to perform a task (cure him of his leprosy) that only divinity can accomplish—akin to the raising of someone from the dead (to kill and to make alive). The tearing of clothes, as well as indicating sorrow (see note on 2:11–13), could also signify consternation (cf. 22:11–13). There is sufficient quiet, on the other hand, for Naaman to travel safely to Israel with his letter and his various gifts. Ten talents of silver represents about 750 pounds (341 kg) of this metal, compared with 150 pounds (68 kg; six thousand shekels) of gold, reflecting the much greater value of the gold (which here is equivalent to the combined annual wages of 600 common laborers).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:9–12 stood at the door. Naaman clearly expects personal and immediate attention from Elisha, but Elisha addresses him only through a messenger and sends him to wash in the Jordan; moreover, Naaman was looking for a cure, and Elisha apparently offers only ritual cleansing (wash … be clean; cf. the cleansing ritual of Leviticus 13–14 with its use of the same Hb. verbs [Lev. 14:8–9 and in 13:7, 35; 14:2, 23, 32]). This he could have had at home, by bathing in the rivers of Damascus.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:13 Has he actually said … ? Naaman’s servants have been listening more attentively, for Elisha did not speak only of ritual cleansing but of healing (“your flesh shall be restored,” v. 10). They urge Naaman to consider Elisha’s actual words and act on them.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:14–15 a little child. The Hebrew is na‘ar qaton, and there is evidently a play on the phrase na‘arah qetannah (“little girl”) in v. 2. The “great man” (v. 1) had a problem, to which the “little girl” had the solution; but the solution involved Naaman’s becoming, like her, “a little child”—someone under prophetic authority, humbly acknowledging his new faith (I know that there is no God in all the earth but in Israel). He had looked to the prophet himself for a cure, in line with the words of his Israelite informant (v. 3); but the way in which the cure has been wrought has made it clear to him that Elisha’s God is a living person, not simply a convenient metaphor for unnatural prophetic powers.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:16 I will receive none. For Elisha to accept a gift is to risk the impression that he is personally responsible for what has happened.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:17 two mule loads of earth. The earth is to be used in the construction of a mud-brick altar (cf. Ex. 20:24–25) for Naaman’s worship of the Lord.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:18 May the LORD pardon is reminiscent of Solomon’s prayer in 1 Kings 8:22–53, with its frequent requests to forgive (1 Kings 8:30, 34, 36, 39, 50) and its consideration of the foreigner who prays toward the temple (1 Kings 8:41–43). Naaman’s dilemma is that he will still be required in the course of his official duties to attend the temple of Rimmon—a reference to the storm god Baal-hadad under a name that has not been previously encountered (see note on 1 Kings 16:31–33; cf. Zech. 12:11).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:20–22 I will run … and get something from him. Gehazi either has not grasped the meaning of what has happened or does not care; he tries to “cash in” on an act of God (cf. Joshua 7; Acts 8:18–24) by means of a story designed to explain a change of heart on Elisha’s part (he has two new arrivals to provide for).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 5:26 Was it a time to accept … ? Gehazi’s aspirations to wealth and status have led him to forget the Lord (cf. Deut. 6:10–12; also compare the list of items here with the catalog of royal wealth in 1 Sam. 8:14–17). Just as kings can misuse their power for self-enrichment, so can the servants of prophets.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:1–23 Elisha and Syria. With the healing of Naaman, Elisha has involved himself with Syria for the first time. That involvement now occupies most of the attention of the authors for the next two chapters, as they prepare the reader for the bloody events of chs. 8–10.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:1–7 While one of the prophetic communities is building a new place to meet, a member of the group loses a borrowed axe head. Elisha has past experience of manipulating the waters of the Jordan by the Lord’s power (2:14), and here he is miraculously able to make the iron float like the piece of wood he has thrown in beside it.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:8 the king of Syria was warring against Israel. Relations between Syria and Israel have deteriorated since ch. 5.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:9 the man of God sent word. Elisha intervenes to help Jehoram, not because anything has changed in his behavior (3:2–3, 13) but simply because the time has not yet arrived for final judgment on this royal house (cf. chs. 9–10). Prophetic oracles apparently were often sought or offered in the ancient Near East in relation to military campaigns (see note on 3:11–14).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:13 Dothan is only 10 miles (16 km) north of the capital city of Samaria, illustrating the extent of Syrian penetration into Israel at this time. But the Syrian king is deluded in his belief that he can send and seize Elisha (cf. 1 Kings 13:1–6; 18:9–14; 2 Kings 1:2–17).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:16 those who are with us. Elisha knows that the Lord has sent an army of angels to protect him, and apparently he can see them but the servant cannot. They are more than a match for the Syrian army (cf. Ps. 91:11; Heb. 1:14).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:17 the LORD opened the eyes of the young man. The angelic armies have been there all along, but they are invisible to Elisha’s servant until the Lord enables him to see them (cf. 2:11; also Num. 22:31; Luke 2:13; Col. 1:16). the mountain was full. Syrian troops may surround (Hb. sabab) the city (2 Kings 6:15), but Elisha himself is supported all around (Hb. sabib) by the army of the Lord.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:18 blindness. Probably not a loss of physical sight (since the Syrians would not doubt their location just because they could no longer physically see it), but rather a dazed mental condition in which they are open to suggestion and manipulation but still able to follow the prophet to Samaria. The Syrians are “bedazzled” and do not “see” things clearly, whereas Elisha’s servant has been given perfect clarity of “sight” about reality.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:19 I will bring you to the man whom you seek. The statement is somewhat puzzling, but rather than leaving the Syrians, Elisha did in fact bring them face to face with the man they were looking for.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:22 You shall not strike them down. Jehoram would not kill men taken captive with your sword and with your bow, and these are not even men like that. They are to be treated as guests.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:24–7:20 The Siege of Samaria. The uneasy peace of ch. 5 gave way in 6:8–23 to sporadic fighting involving Syrian raids into Israelite territory, curtailed because of what has just happened to the last of the raiding parties (6:23), but now comes a full-blown invasion.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:25 donkey’s head … dove’s dung. Donkeys were commonly found among the domestic animals in Syria-Palestine, and various OT laws identify them as significant possessions (e.g., Ex. 13:13; 20:17; 22:4). So severe was the siege that the inhabitants of Samaria were reduced not only to slaughtering and eating valuable animals, but also to consuming body parts that would not normally be consumed, and purchasing them for exorbitant prices (the cost of a live horse in 1 Kings 10:29 is only 150 shekels of silver, and here a donkey’s head costs eighty). During this crisis even half a liter (the fourth part of a kab) of dove’s dung cost what the average worker could make in six months (five shekels of silver).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:26–27 Help, my lord, O king. The plea is directed to the king as the ultimate court of human justice, as in 1 Kings 3:16–28, but Israel has strayed a long way from that glorious era when a wise king could ensure justice. The normal food supply is exhausted; nothing comes from the threshing floor (see note on 1 Kings 22:10–12) or winepress (a flat, hard surface on which grapes could be trodden, with the juice running off into a reservoir and then being poured into large jars for fermentation).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:28–29 Give your son. The Assyrian king Ashurbanipal also reports that, during his two-year siege of Babylon (which ended in 648 B.C.), “famine seized them; for their hunger they ate the flesh of their sons and daughters”; the Bible itself reports other instances of cannibalism arising from a long siege (e.g., Lam. 2:20; 4:10; Ezek. 5:10).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:30–31 he tore his clothes. See notes on 2:11–13; 5:5–7; sackcloth is also symbolic of mourning and distress. Jehoram appears to believe that removing Elisha will remove the problems he is facing.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 6:32 the elders were sitting with him. As the “sons of the prophets” seem to have gathered to listen to the prophet (ch. 4), so here the elders of Samaria are gathered together in Elisha’s house (cf. the similar scenario in Ezek. 8:1; 20:1).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 7:1 a seah of fine flour … two seahs of barley. A seah is about 7 quarts (7.7 liters). The king will have to wait no longer: salvation is imminent, and normal business at the gate of Samaria will be resumed on the following day (the prices are much lower here than in 6:25). The open area inside city gates served various important social purposes in ancient times. Among other things, agricultural activities took place and business was transacted there (e.g., Gen. 23:10; 34:20).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 7:2 windows in heaven. It is impossible for this officer to imagine how such an economic recovery could happen overnight, in the aftermath of such a terrible siege. Will God hand out unexpected material blessings through the windows of his heavenly storehouse (cf. Ps. 78:23; Mal. 3:10)? To mock the prophetic word is to mock the Lord himself, however, so he shall see it … but … not eat.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 7:3–4 four men who were lepers. A leper had first brought the Syrians to Samaria during Jehoram’s reign (5:1–7), and four men with a similar ailment now drive them away. Faced with certain death if they enter the city or sit where they are, they instead choose possible death in the camp of the Syrians.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 7:6 kings of Egypt. Perhaps the four lepers (Hb. metsora‘im), seen in the twilight (v. 5), are mistaken for a mercenary army drawn from northern Syria and from Egypt (Hb. Mitsrayim); otherwise, the delusion came from another source.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 7:13–14 five of the remaining horses. Only two horsemen are sent. Perhaps they take with them three spare horses, or one spare horse (if the horsemen took two chariots, each having two horses).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 7:20 the people trampled him. The skeptical officer of v. 2, ironically stationed at the very gate at which he had anticipated seeing no trade, is trampled in the scramble to acquire goods, fulfilling Elisha’s prophecy.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:1–6 The Shunammite’s Land Restored. After the long narrative about the siege of Samaria, the Shunammite woman of 4:8–37 reappears. The key to understanding this new story is found in 4:13, where the woman declines Elisha’s offer of help because she has a home among her own people. In 8:1–6, however, she no longer has such a home, for she has followed Elisha’s advice and avoided famine by sojourning in Philistia.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:1 Elisha had said. The prophecy had been delivered around the same time that Elisha restored the woman’s son to life, and the famine had followed shortly thereafter (cf. 4:38). This general state of famine is to be distinguished from the even more severe famine in the city of Samaria described in 6:24–7:20, which is specifically the result of siege.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:2 The land of the Philistines was a natural place for the Shunammite woman to seek refuge during a time of famine in Israel (the patriarch Isaac himself moved into this region in similar circumstances; Gen. 26:1), not least because of its proximity to Egypt, the breadbasket of the ancient world and the common destination throughout the biblical period of people escaping times of hardship (e.g., Gen. 12:10; 41:53–42:5; 47:4).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:3 her house and her land. Someone has taken the woman’s property in her absence—perhaps Jehoram himself, showing the same land-grabbing tendencies as his parents (cf. 1 Kings 21). The king was now the recipient of her appeal, as the person with primary responsibility under God for the establishment and maintenance of order and justice throughout the kingdom (cf. Psalm 72). In Israel the end of the seventh year was a proper time for restoration of property and cancellation of debt (Ex. 21:2–3; Deut. 15:1).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:6 all the produce. The king goes farther than restoring everything that belonged to the woman; he also provides her with all the income from her land that she would have received had she stayed in the country.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:7–15 Hazael Murders Ben-hadad. The house of Omri has now held the throne of Israel since 1 Kings 16:23, and in spite of Elijah’s prophecy in 1 Kings 21:21–24 about its end, one now reads of Ahab’s second apostate son holding on to his kingdom with the help of Elijah’s successor (e.g., 2 Kings 3:1–27; 6:9–10). Has Elijah sabotaged God’s plan by failing to anoint Hazael and Jehu (1 Kings 19:15–18)? It turns out that the answer is no. Hazael is now introduced, to be followed shortly by Jehu.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:8–9 meet the man of God. Ben-hadad II consults Israel’s God about his future in much the same way that King Ahaziah of Israel earlier consulted Baal-zebub of Ekron (see note on 1:2). It appears to have been customary when consulting prophets to offer some payment, in this case an extravagant gift of forty camels’ loads of goods (cf. 1 Sam. 9:1–9; 1 Kings 14:1–4; 2 Kings 5:1–6). The messenger Hazael enters the narrative mysteriously. Readers are not told his lineage, nor even his role (servant? officer?). He comes from nowhere—a mere “dog,” as he puts it in 8:13. A fragmentary Assyrian text on a basalt statue of King Shalmaneser III refers to him similarly as the “son of nobody,” doubtless reflecting lowly, nonroyal origins.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:10 say to him, “You shall certainly recover.” This is what the Hebrew text says. But the word translated “to him” (Hb. lo) is sometimes to be read as the negative word “not” (the Hb. word lo’ has virtually the same sound as the almost identical Hb. word lo). If this is the case, then Hazael is to say to Ben-hadad, “You will certainly not recover” (see esv footnote), and Hazael would have lied to the king (v. 14). But if the Hebrew of Elisha’s statement does indeed mean “You shall certainly recover,” it could have been a truthful prediction about the course of Ben-hadad’s sickness that was still negated when Hazael murdered him—i.e., Ben-hadad could have recovered had Hazael not murdered him. Alternatively, some have suggested that Elisha’s statement was in fact deceptive, to lull the king into a false sense of security, so that he would be unprepared for Hazael’s attack.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:11 he fixed his gaze. The text does not identify “he” and “him” in this verse. Most interpreters understand the first “he” to be Elisha, who “fixed his gaze” on Hazael, staring at him but also seeing with prophetic vision what Hazael would do in the future. Hazael does not know how to respond and is embarrassed, and then Elisha weeps. An alternative interpretation is that Hazael remains dazed by what he has heard and so he stares at Elisha, until Elisha’s weeping breaks into his reverie.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:15 Hazael became king. Hazael came to power in Syria at some point between the Assyrian Shalmaneser III’s campaign in the west in his fourteenth year (845 B.C.), when it is known that Ben-hadad (a throne name; his personal name was Adad-idri) was still on the throne, and the campaign of Shalmaneser’s eighteenth year (841), which records Hazael as king. He reigned for about 40 years as one of Israel’s most bitter enemies.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:16–29 Jehoram and Ahaziah. Judah was last mentioned in ch. 3, when Jehoshaphat was king of Judah. Another Judean king has come and gone in the meantime, however, and the reader must be told about him and be introduced to his successor in order to understand chs. 9–10.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:16 Jehoram the son of Jehoshaphat. First introduced briefly in 1 Kings 22:50, this king is mentioned again in 2 Kings 1:17. In 8:21, 23–24, his name appears as “Joram,” which is also the name of the king of Israel in this period (v. 16). This Israelite king is himself called “Jehoram” in such verses as 1:17 and 3:1. At precisely the point when the southern monarchy has come to resemble the northern monarchy most closely in its worship (see note on 8:18), their kings are called by the same name, and one must work hard to distinguish their actions in the text.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:18 Jehoram walked in the way of the kings of Israel. His father, Jehoshaphat, had made peace with the king of Israel in the aftermath of the struggles that arose out of the division of the kingdoms under Jeroboam and Rehoboam (1 Kings 22:44). From Jehoshaphat’s reign onward, the fortunes of the house of Omri and the house of David were closely interconnected. There was intermarriage between the two families (Jehoram had married the daughter of Ahab), and the two kingdoms followed a similar religious policy (as the house of Ahab had done).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:19 he promised to give a lamp to him. See 1 Kings 11:36; 15:4. Sins in David’s family are to be punished not with the destruction of his dynasty but with the “rod of men” (2 Sam. 7:14–16)—divine discipline, characterized in 1–2 Kings as “affliction” (see 1 Kings 11:39). So it is that the LORD was not willing to destroy Judah, for the sake of David his servant.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:20–22 In his days Edom revolted. The “affliction” on David’s house in this case (cf. note on v. 19) comes in Jehoram’s failure to subdue a rebellion by Edom, a country hitherto ruled by a king appointed by Judah (1 Kings 22:47; see note on 2 Kings 3:7–9), and in unrest even within Judah itself: Libnah was a Judean city to the southwest of Jerusalem and 5 miles (8 km) to the northeast of Lachish, with which it is associated in 19:8. Chronicles adds to this picture of a weak king by telling of attacks from the Philistines and Arabs who had given tribute to Jehoram’s father (2 Chron. 21:16–17).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:23 Chronicles of the Kings. See note on 1 Kings 14:19.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:25–27 Ahaziah the son of Jehoram. This Judean king, too, has habits of religion to match those of the family to whom he is related by marriage (He also walked in the way of the house of Ahab). The fact that he reigned for only one year, combined with the fact that he began his reign in the twelfth year of Joram … king of Israel (i.e., Joram’s last year, 3:1), is the first hint of moving toward the end of the house of Omri.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 8:28–29 war against Hazael king of Syria. The context in which the house of Omri comes to its end is now provided. Another joint battle against the Syrians at Ramoth-gilead (cf. 1 Kings 22:1–4) is followed by withdrawal to the Omride stronghold of Jezreel, so that the Israelite king can recover from his wounds. Ramoth-gilead is apparently back in Israelite hands by this point in the narrative (2 Kings 9:14), perhaps abandoned in the course of the general Syrian retreat in 7:3–7.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:1–10:17 The End of Ahab’s House. Of the players in the last act of Ahab’s drama who were mentioned in 1 Kings 19:15–18, only Jehu has remained out of the picture. His story is now told.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:1 Tie up your garments. See 1 Kings 18:46 and 2 Kings 4:29; speed will be important for this messenger from among the sons of the prophets (the prophetic communities over which Elisha presides; see note on 2:3). The army is still at Ramoth-gilead, even though the king has withdrawn to Jezreel (8:29).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:2 Jehu the son of Jehoshaphat, son of Nimshi. Jehu was described in 1 Kings 19:16 only as “son of Nimshi” (cf. also 2 Kings 9:20), but Nimshi now turns out in fact to have been his grandfather rather than his father (who shares his name with a Judean king, Jehoshaphat). This use of Hebrew ben to mean “grandson” rather than “son” certainly occurs in the OT (e.g., Gen. 29:5; 31:28), but it is unusual for the grandfather to be referred to in citations of this particular kind; perhaps Nimshi was a particularly well-known person.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:3 flask of oil. Elijah had been commanded to anoint Jehu king over Israel (1 Kings 19:16), but had failed to do so. It is left to Elisha now to fulfill his mission. Anointing with oil was a common practice in the ancient Near East to mark various rites of passage, and in Israel it was closely associated with the enthronement of kings (see 1 Sam. 16:13). It appears to be bound up with the king’s legitimacy and right to rule; to be the “anointed of the Lord” is to be a person inviolable and sacrosanct (1 Sam. 24:6–7; 2 Sam. 19:21–22). The secret anointing that takes place here (in an “inner chamber”; 2 Kings 9:2) is particularly reminiscent of Samuel’s anointing of Saul (cf. 1 Sam. 9:27–10:1). The reasons for Elisha’s advice to the messenger to open the door and flee are not provided, but the reference to Jehu’s reckless chariot driving in 2 Kings 9:20 perhaps suggests that he has a reputation for rash behavior and could be dangerous to the messenger.

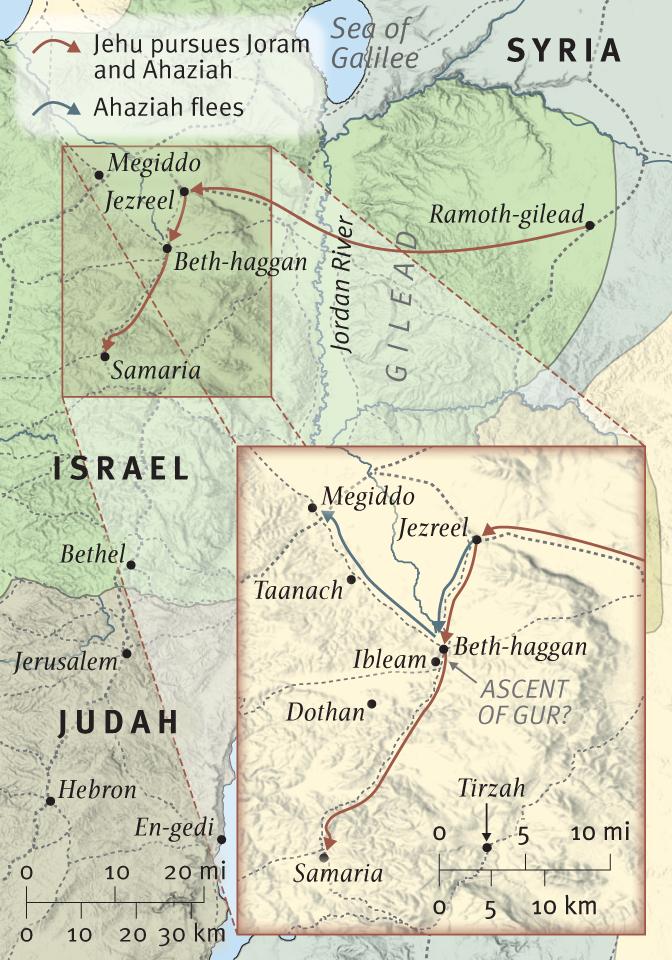

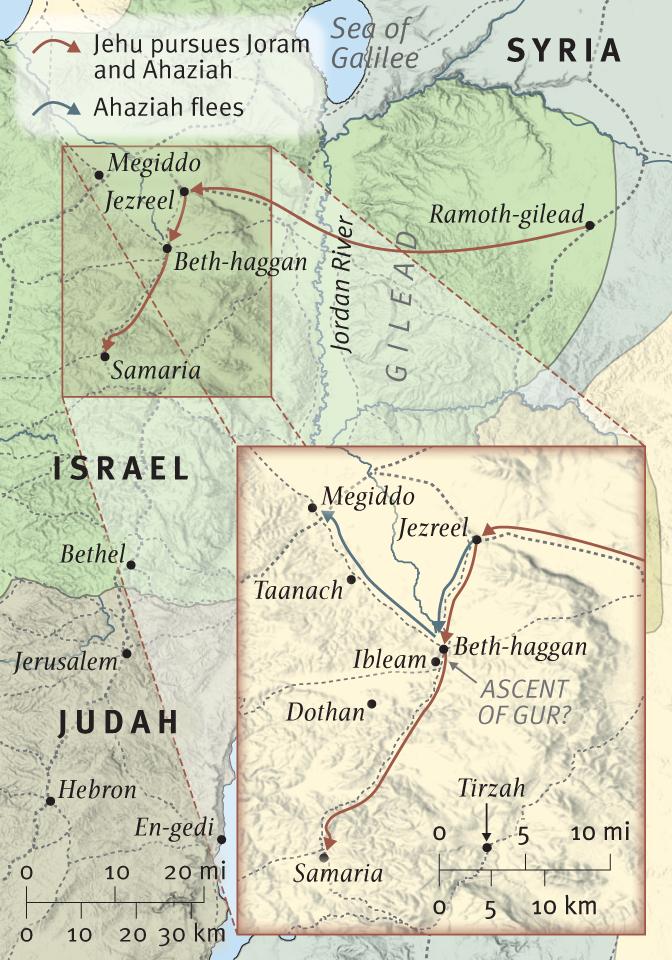

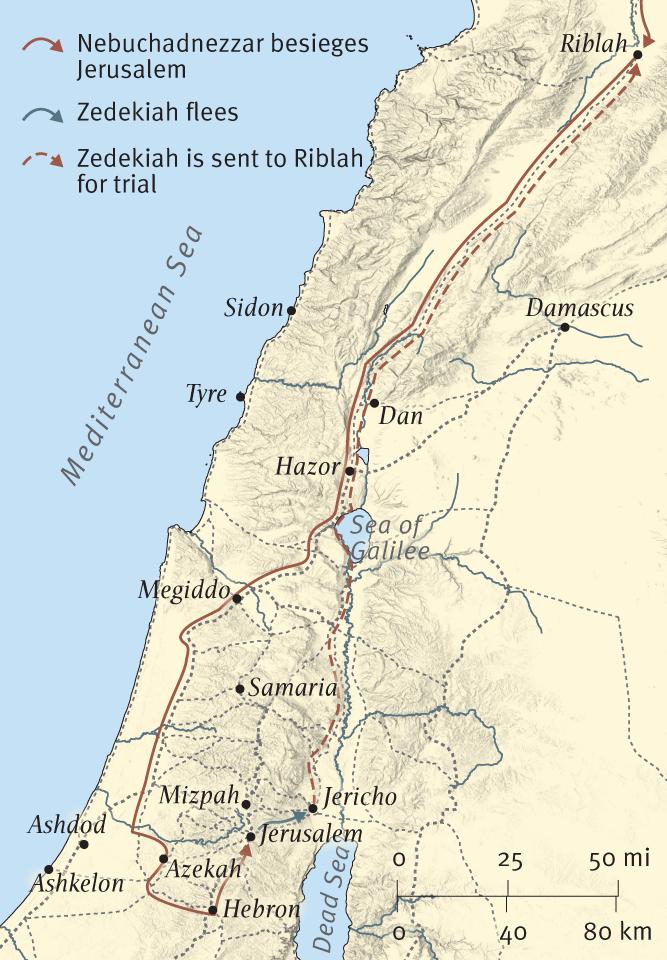

Jehu Executes Judgment

841 B.C.

Elisha fulfilled the Lord’s prophecy to Elijah by sending someone to Ramoth-gilead to anoint Jehu, one of Joram’s commanders, as king of Israel. Jehu promptly headed for Jezreel, where King Joram (also called Jehoram) of Israel was recovering from some battle wounds. When Joram and King Ahaziah of Judah went out in their chariots to meet Jehu, Jehu mortally wounded Joram with an arrow and chased Ahaziah to Beth-haggan, where he wounded him as well. It appears that Ahaziah then fled to Megiddo, where he died (see also 2 Chron. 22:9).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:7 you shall strike down the house of Ahab. The oracle actually delivered by the messenger is much longer than the one pronounced by Elisha in v. 3. The essence of the message is given there, with its fuller form being delayed until later, presumably so that repetition should not unnecessarily hold up the narrative. For the same reason, only the essence of the message is later communicated by Jehu to his fellow officers (v. 12), the details being subsumed under “Thus and so he spoke to me.” the blood of my servants the prophets. Elijah did not explicitly state to Ahab in 1 Kings 21:21–24 that the Lord’s action against Ahab’s house would be partly a matter of vengeance for the blood of the prophets. This is implicit in 1 Kings 19:14–18, however, where God’s response to Elijah’s complaint about the murder of the prophets (1 Kings 18:4, 13) is precisely to send him to anoint Jehu (among others).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:10 none shall bury her. Similarly, this is not explicitly stated in 1 Kings 21:23, nor indeed is it said that Jezebel’s body would be like “dung on the face of the field … so that no one can say, ‘This is Jezebel’” (2 Kings 9:37); but these things are implicit in the statement that dogs shall eat Jezebel (1 Kings 21:23). It was considered a terrible thing in Israel not to be afforded a proper burial (cf. Deut. 28:25–26; Jer. 16:4).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:13 they blew the trumpet and proclaimed, “Jehu is king.” The people’s eagerness to do this suggests that there was already unrest in the army because of Jehoram’s lack of success in his military ventures.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:17–20 I see a company. As Jehu approaches with his army, it is not at first clear to those within the city what is happening. The watchman initially sees only a company (lit., “a multitude”). Later, after the two messengers sent out to elicit information have failed to return, he deduces from the manner in which the lead chariot is being driven that Jehu is involved: he drives furiously.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:22 Is it peace, Jehu? It seems improbable that Jehoram and Ahaziah would have left the safety of Jezreel to meet Jehu if there had been any doubt in their minds about his intentions. The Hebrew hashalom has the sense, “Is all well?” (cf. 4:26; 5:21; 9:11). Jehoram has sent messengers, and has now gone out himself, to discover what brings Jehu to Jezreel: has disaster overtaken Ramoth-gilead, and is this company all that remains of his army? Jehu’s response is to ask how things can be well in a kingdom dominated by the Baal religion and the whorings of Joram’s mother Jezebel. “Whorings” (Hb. zenunim), also linked with sorceries (Hb. keshapim) in Nah. 3:4, is a term associated with fertility religion in Hosea (Hos. 1:2; 2:2, 4; 4:12; 5:4). It is derived from the Hebrew verb zanah (cf. 1 Kings 3:16; 22:38).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:25–26 plot of ground belonging to Naboth the Jezreelite. See the prophecy of Elijah to Ahab in 1 Kings 21:17–24, which precipitated that king’s death (1 Kings 22, esp. v. 38; see also note on 1 Kings 21:19) in circumstances similar to those of his son Jehoram (death by arrow, 1 Kings 22:34).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:27–28 he fled to Megiddo and died there. Linked with Ahab in marriage and at one with him in religion, Ahaziah also shares in his fate. He is shot … in the chariot, later to be transported dead to his capital city for burial (cf. 1 Kings 22:34–37). The shooting takes place near Ibleam, one of the cities that guarded access to and from the southern end of the Jezreel Valley, as Ahaziah flees south from Jezreel back toward Samaria; but after the attack he abruptly changes direction and heads northwest for Megiddo in the western part of the Jezreel Valley. Megiddo was an important and strategic city in ancient times, controlling the main international highway running from Egypt to Damascus as it entered the valley. Israelite remains at Megiddo from the period of the divided monarchy are numerous. An imposing water tunnel, probably cut during Ahab’s reign (9th century B.C.), was discovered here. A large vertical shaft (115 feet/35 m) was cut into bedrock, and then a 200-foot (61-m) horizontal shaft was dug to reach a spring outside the city. A series of buildings was discovered that probably served as either storehouses or stables in the time of Ahab.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:29 the eleventh year of Joram the son of Ahab. In 8:25 one reads of “the twelfth year.” Accession dates could be reckoned in different ways, particularly in terms of the way that part-years were handled, resulting in such apparent discrepancies. The new information is given here to clarify how it could be that both men died at the same time if Jehoram reigned for 12 years (3:1) yet Ahaziah, who came to the throne in Jehoram’s “twelfth year,” reigned for one year. The fragmentary ninth-century B.C. Tell Dan inscription probably alludes to the deaths of these same kings, although the Syrian king responsible for the inscription there claims responsibility for the deaths of the Judean and Israelite kings mentioned—a good example of the oversimplification and hyperbole that is typical of victory monuments in the ancient Near East. Perhaps Hazael regarded Jehu as a vassal, and felt justified in claiming Jehu’s feats as his own.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:30 she painted her eyes and adorned her head. This could mean only that Jezebel met her end proudly, dressed up as a queen should be. Her posture, however, echoes the “woman in the window” motif found on carved ivory plaques from various ancient Near Eastern sites (see note on 2 Sam. 6:16–19), which may represent the goddess Astarte, one of the wives of Baal; so perhaps Jezebel is being represented as the very incarnation of the religion that she brought into Israel from Sidon.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:31 Is it peace, you Zimri? “Is it peace?” is a question intricately tied to the demise of Ahab and his dynasty (see note on v. 22; cf. vv. 18–19; 1 Kings 22:28). Jezebel asks, sarcastically, whether “all is well” (knowing that all is far from well) and she taunts Jehu as one who is unlikely to survive his own revolution (Zimri’s reign was a “seven-day wonder”; see 1 Kings 16:8–20).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:32 It was common practice in the ancient world for the king to have a harem (cf. 1 Kings 11:3), and for the harem to be provided with guards. These guards were typically eunuchs (castrated males), so that the king could be sure that the males close to his women were not capable of sexual relations with them. Eunuchs also performed an important role in the official hierarchy of the ancient Near East more generally. In neo-Assyrian sources, e.g., they are attested at the royal court, in the army, in the bureaucracy, and in the provincial administration. They functioned, among many other roles, as the king’s personal attendants, cooks, palace guards, scribes, and ambassadors.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 9:36 the word of the LORD, which he spoke by his servant Elijah. Using the language of covenant curses, Elijah earlier prophesied the “cutting off” of all the males of Ahab’s house (1 Kings 21:21–22; 2 Kings 9:8–9) as well as the gruesome death of Jezebel (1 Kings 21:23; 2 Kings 9:10). dogs shall eat. The exposure of Jezebel’s corpse to devouring dogs meant disgrace since burial was now impossible. Now that Jezebel is dead, Jehu turns his attention to Ahab’s sons (see note on 10:1).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:1 Now Ahab had seventy sons in Samaria. Elijah had prophesied that the Lord would consume Ahab’s descendants and cut off from him every last male in Israel (1 Kings 21:21; cf. the previous prophecies against Jeroboam and Baasha in 1 Kings 14:10; 16:3). Jehu now looks to fulfill this prophecy. The guardians of the sons of Ahab are probably those in general who were loyal to Ahab and to his house, as distinct from the rulers and the elders with their specific roles.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:3 fight for your master’s house. By writing letters to the leading citizens and challenging them to place one of Ahab’s potential heirs on his father’s throne, Jehu forces them to choose sides.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:5 he who was over the palace … he who was over the city. These are the “rulers of the city” mentioned in v. 1. The position of palace administrator was an important one (cf. 15:5; 18:18, 37; 19:2), and his power at least in Judah is indicated in Isa. 22:22. Both the title (“he who was over the palace”) and sometimes the names of its holders are found in extrabiblical inscriptions. The joint reply of these two officials along with the elders and the other former Ahab loyalists (the “guardians”) reveals that they are no longer Ahab’s or Jehoram’s, but are now Jehu’s servants.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:7 they took the king’s sons and slaughtered them. This fulfills the word of the Lord in 9:7–9 and is similar to other instances in which entire groups of people are put to death (e.g., Dan. 6:24, which likewise does not commend the action; cf. note on 2 Sam. 21:3–6). This kind of drastic action against a royal household was not at all uncommon in the ancient world, as the present incumbents of thrones tried to ensure a future free of retaliation. For example, the Aramaic Panammuwa Inscription (c. 733–727 B.C.) records that Panammuwa of Sam’al was the survivor of a palace coup in which a brother killed his father Barsur, along with 70 brothers of his father. This text and the biblical text in Judg. 9:5, where Abimelech kills 70 of his brothers before being crowned king, may suggest that the number seventy in such contexts is a round number, or a matter of literary convention, rather than an exact number. In any case, the number of sons of such a monarch could be quite large.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:8–10 two heaps at the entrance of the gate. The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II records in an inscription that during his siege of the city of Damdammusa he cut off the heads of 600 of his enemy’s troops and, in an act of intimidation, “built a pile of heads before his gate.” Jehu’s aim is similar: to convince the people that resistance is futile. He knows who struck down all these, but the people do not; and he invites them to believe that the heads mean that the revolution is bigger than he is, involving mysterious powers more lethal than his (he killed only his master); it is truly the LORD who is at work in overthrowing the house of Ahab. As fair-minded (implied by innocent) people, they should be able to arrive at the correct interpretation of the evidence.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:13–14 His work in Jezreel complete, Jehu leaves for Samaria. On the way, he encounters some relatives of Ahaziah king of Judah. The Judean royal family keeps being drawn into the events, even though there was no prophetic forewarning. Cf. 9:27 for the death of Ahaziah. they took them alive and slaughtered them. This new king is thorough in exterminating all traces of the past, and the consequences for Judah will be dire (11:1).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:15 Is your heart true to my heart as mine is to yours? The Hebrew vocabulary of yashar (“right,” “true”) and lebab (“heart”) appears in other places in 1–2 Kings (e.g., 1 Kings 14:8), including 2 Kings 10:30 in relation to Jehu himself: “you have done well in carrying out what is right in my eyes, and have done to the house of Ahab according to all that was in my heart.” The wording here underlines that the theme throughout the chapter is “who is on the Lord’s side; who is in the right?” Jehonadab, who is on the right side, reappears in Jeremiah 35 (“Jonadab”) as the founder of a purist religious group committed to Israel’s older ways.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:18–36 Jehu Destroys Baal Worship. It is no surprise to find Jehu now taking decisive action against the worship of Baal, for 1 Kings 19:15–18 had pointed toward final victory over Baal worship in naming Jehu (along with Hazael, 2 Kings 10:32–33) as the Lord’s instrument of judgment.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:18–19 Jehu assembled all the people. Samaria had been the focal point for the Baal cult (cf. 1 Kings 16:32–33), to which Jehu now gives his attention. His strategy is to feign enthusiasm while preparing for destruction; he tells the people that although the dynasty has changed, the religious policy will remain the same (Ahab served Baal a little, but Jehu will serve him much).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:20 Sanctify a solemn assembly. This phrase is unparalleled in Hebrew, but a Ugaritic text concerned with gaining protection for the royal ancestors of King Ammurapi of Ugarit suggests that it represents genuine Canaanite religious terminology.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:25 inner room. The Hebrew is ‘ir, which normally means “city.” In this context it presumably refers to some “city-like” aspect of the temple, behind its own walls—perhaps an inner room or a walled courtyard.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:27 the pillar of Baal … the house of Baal. See 1 Kings 16:32–33 and 2 Kings 3:2. Baal worship in Israel is officially at an end. It has neither royal patronage nor royal tolerance.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:29 did not turn aside from the sins of Jeroboam. The worship of Baal was only a particularly bad form of the idolatry practiced in Israel. Jehu has dealt with Baal worship, but he does nothing at all about the golden calves … in Bethel and in Dan that Jeroboam installed after leading Israel in revolt against the house of David (1 Kings 12:25–30). The symbolism of these calves encouraged a blurring of the distinction between Mosaic and Canaanite religion; the high god of the Canaanite pantheon, El, is frequently called “the bull” in Ugaritic materials (signifying his strength and fertility), and Baal himself is also represented as a bull. Archaeologists have discovered bull icons at numerous sites in Syria-Palestine, including Byblos, Ugarit, and Hazor.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:30 Since Jehu does not abolish the golden calves in Bethel and Dan (v. 29; cf. v. 31), it is surprising to find him addressed as someone who has carried out what is right (Hb. yashar) in the eyes of the Lord. In other places, the authors of Kings use yashar only positively, with regard to David (1 Kings 15:5) and the relatively good (i.e., non-idolatrous) kings of Judah (1 Kings 15:11; 22:43; 2 Kings 12:2; 14:3; 15:3, 34; 18:3; 22:2). It is even more surprising to find Jehu receiving a David-like dynastic promise. His descendants will sit on the throne of Israel to the fourth generation. This is not the same thing as a promise of eternal dynasty, but it is nevertheless extraordinary; Jeroboam was promised a dynasty like David’s if he did “what was right” in the Lord’s eyes (1 Kings 11:38), but then he failed and lost this opportunity (1 Kings 14:8). Evidently what Jehu has done that is right (eradication of Baal worship) far outweighs what he continues to do that is wrong.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:32–33 the LORD began to cut off parts of Israel. First Kings 19:15–18 pointed to a time when God’s judgment would fall on Israel because of Baal worship. Jehu would deal with those who escaped Hazael, and Elisha with those who escaped Jehu. Implicit in such an ordering was that Hazael would turn out to be the greatest destroyer of the three—something to which 2 Kings 8:12 also pointed, with its emphasis on Hazael’s brutality. It is no surprise, therefore, to find now an account of Hazael’s aggression against Israel. He is said to have conquered Transjordan as far south as the Valley of the Arnon, the southern limit of Israelite Transjordanian territory (cf. Josh. 12:2). This military success occurred during the lull in Assyrian aggression against Syria-Palestine between the campaign of Shalmaneser III’s twenty-first year (838 B.C.), when he captured four of Hazael’s cities and accepted tribute from the peoples of the Phoenician coast, and the campaign of the fifth year of Adad-nirari III (806). This respite enabled Damascus to turn its full attention toward Israel and Judah and to subject these kingdoms to prolonged pressure in the last decades of the ninth century. More of Hazael’s conquests will be reported later (2 Kings 12:17–18; 13:3–7, 22–23).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 10:34 the rest of the acts of Jehu. Jehu appears in Assyrian records describing an event that must have taken place shortly after his accession to the throne, during the western campaign of Shalmaneser III’s eighteenth year (841 B.C.). During that campaign King Shalmaneser besieged Damascus, marched on to the Hauran Mountains in southern Syria, then through Gilead to the south of the Sea of Galilee and through Jezreel to Ba’li-ra’si (perhaps Mount Carmel) near Tyre. Hosea 10:14 may preserve a memory of this march through northern Palestine, since “Shalman” there is probably an abbreviated form of Shalmaneser’s name. At this time, Shalmaneser collected tribute from “Jehu the Israelite” as well as from Tyre and Sidon. The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (859–824 B.C.), found at the site of Nimrud, depicts the Israelite king Jehu giving tribute. Jehu, or perhaps his emissary, lies prostrate before the king while other Israelites present tribute that includes gold and silver objects. If the figure is Jehu, then it is the only extant pictorial representation of an Israelite king from antiquity. Shalmaneser III, after having received tribute from Jehu, also plundered Tyre and Sidon in Phoenicia. In commemoration of this successful campaign, Shalmaneser had his portrait carved on the cliffs of the Dog River, north of Beirut.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 11:1–12:21 Joash. The destruction of the house of Ahab has greatly affected the house of David: Ahaziah (of Judah) has been killed, just like Jehoram (of Israel), and a number of his relatives have suffered the same fate as Ahab’s relatives (10:12–14). Have the two houses become so identified in intermarriage (8:18, 27) that a distinction no longer exists between them? Chapters 11–12 clarify that in fact the distinction remains, for David’s house survives even the assault of wicked Queen Athaliah, a Judean “Jezebel.”

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 11:1–3 Athaliah the mother of Ahaziah. Possibly a daughter of Jezebel (8:26), Athaliah certainly displays the same ruthless streak. Her attack on the royal family is stemmed only by the resourceful Jehosheba, who hides the young Joash and his nurse in the Jerusalem temple. The nurse’s willingness to share danger with the child in her care contrasts sharply with the spineless leading men of Samaria in 10:1–7. Cf. note on 2 Chron. 22:10–12.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 11:4 Jehoiada … the Carites and … the guards. It is subsequently clarified that Jehoiada is the chief priest (vv. 9, 15). Jerusalem’s guards and their duties around the palace and the temple have been described in 1 Kings 14:27–28. The Carites appear in the consonantal Hebrew text of 2 Sam. 20:23 as part of the elite royal bodyguard alongside the Pelethites. They may well be the same body as (or at least the regiment may be descended from the regiment of) the Cherethites, with whom the Pelethites normally appear in the OT (2 Sam. 8:18; 15:18; 20:7, 23; 1 Kings 1:38, 44); see note on 1 Kings 1:38.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 11:5–8 This is the thing that you shall do. The normal duties of the troops mentioned here are reasonably clear: the guarding of the king’s house (the royal palace) and the house of the LORD (the temple), along with two important gates. The gate Sur was a gate in the walled enclosure that surrounded the temple precincts and the royal residences in Jerusalem, probably to be identified with the gate of Shallecheth of 1 Chron. 26:16 (called the “Gate of the Foundation” in 2 Chron. 23:5). From this gate a road ascended to the Fish Gate at the northwest corner of the city’s outer defensive wall. The gate behind the guards was apparently located in a wall separating the temple and palace complexes (2 Kings 11:19) and is called the “upper gate” in 2 Chron. 23:20 (cf. 2 Kings 15:35). The interpretation of the troops’ reassignments, however, is more difficult. It does not seem likely that the troops in 11:5–6 are being assigned to guard the king’s palace (v. 6), for the terminology used to specify the building at the end of v. 6 (Hb. habbayit massakh, perhaps “house named destruction”?) is not the same as the terminology used of the royal palace in v. 5 (“the king’s house,” Hb. bet-hammelek). Furthermore, Athaliah leaves the royal palace unhindered in v. 13, with no guards in sight. Most likely, then, it is the temple (“palace”) of Baal that is to be guarded in v. 6—the building destined for destruction in v. 18. Troops are sent to both temples: the “house named destruction” (vv. 5–6) and the “house of the LORD” (v. 7). They are sent to the first in order to discourage interference by the worshipers of Baal and to detain the priest Mattan. The overall concern is that sufficient security be provided for the coronation ceremony to take place within the temple precincts.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 11:10 spears and shields. Since it is not likely that the soldiers needed to be armed by the chief priest, it is probably the symbolism that is important here. The commanders are making it clear that they have allied themselves with David’s cause, and at the same time they are receiving articles to be given to the new king as symbols of his royal power (the spear is a prominent royal weapon in the books of Samuel; e.g., 1 Sam. 18:10–11; 22:6).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 11:12 the testimony. Joash is presented with a list of divinely ordained laws (Hb. ‘edut). For kings ruling under divine law, see Deut. 17:18–20; 1 Kings 2:3; 2 Kings 23:3.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 11:14 pillar. In 1–2 Kings the Hebrew ‘ammud has appeared thus far only in 1 Kings 7, referring to the pillars of the Solomonic palace (1 Kings 7:2–3, 6) and temple (1 Kings 7:15–22, 41–42). Either Jachin or Boaz is probably in view here (1 Kings 7:21); “Jachin” may mean “the establisher,” and would thus provide a fitting location for a coronation. The emphasis on custom is important in a context where the authors are trying to stress the legitimacy of Joash’s claim to the throne; the coronation takes place in line with law and custom, and in full view of the people of the land.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 11:17 Jehoiada made a covenant. The king and people once more identify themselves as the LORD’s people through a covenant-renewal ceremony (cf. Josh. 24:1–27; 2 Kings 23:1–3). At the same time, a covenant is made between the king and the people (cf. 2 Sam. 5:1–3), redefining kingship in distinctively Israelite terms after a period in which foreign ideas have dominated.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 11:21 Joash, introduced by that name in v. 2, will be called Jehoash throughout most of ch. 12, to be called Joash again only in 12:19, where his death is reported. See also note on 13:9.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 12:2–3 Jehoash (i.e., Joash; see note on 11:21) did what was right. He was a relatively good king who rejected idolatrous worship (contrast the verdict on the idolaters Jehoram and Ahaziah in 8:18, 27), but the high places were not taken away (see note on 1 Kings 3:2; cf. also 1 Kings 15:14; 22:43).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 12:4–5 repair the house. The temple of the Lord had suffered neglect during the years in which the worship of Baal was encouraged, and to neglect a temple in the ancient world was to neglect its deity and to risk his or her disapproval and the possible undermining of a king’s legitimate authority to rule (which is why a king such as Esarhaddon of Assyria had servants traveling around his realm and sending him reports about the state of its temples). Three sources of income are specified as the repair project gets underway here. Two of these represent regular temple income: payments made in relation to the periodic census of male Israelites (money for which each man is assessed; Ex. 30:11–16), and monetary equivalents for things dedicated to God (money from the assessment of persons; Lev. 27:1–25). Money that a man’s heart prompts him to bring refers to a special fund-raising campaign similar to that initiated by Moses, at God’s command, in Exodus 35 (where people also give from the heart; Ex. 35:5, 21–22, 26, 29).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 12:7–12 hand it over. Joash’s initial plan was to leave the matter to the priests themselves (vv. 4–5). But this plan fails because, it is implied, the priests are not eager to spend good money on mere buildings, even though they are well provided for through the normal sacrificial system (v. 16; cf. Num. 5:5–10). Joash himself therefore takes control of the project, ensuring that the income goes directly to the workmen appointed to supervise the work.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 12:13 But there were not made … any vessels of gold, or of silver. Joash’s achievements, after all his efforts, are somewhat disappointing: only a very humble restoration of the temple has taken place, and it stands as a poor reflection of its former glory (cf. 1 Kings 7:50). Once again the reader is reminded of the “affliction of the house of David” theme (1 Kings 11:39) that has surfaced in the description of even the best of the post-Solomonic Judean kings.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 12:17–18 took all the sacred gifts. The theme of affliction continues: Judah, too, is oppressed by Hazael king of Syria (cf. 10:32–33 for his assault on Israel), as he turns east from the Philistine city of Gath to attack Jerusalem. This presupposes that Hazael could move at will through Israelite territory to the north, so that the campaign is best dated during the reign of Jehu’s son Jehoahaz (c. 815–799 B.C.), who fared even worse than his father at the hands of Syria (13:1–7, 22–23). Like Asa, Joash knows no Solomonic peace during his rule, and tribute flows north from Israel to Syria, instead of south from Syria to Israel (cf. 1 Kings 15:18–24). Both Asa and Joash in fact empty the treasuries of the house of the LORD and of the king’s house. Long past are those days when the king of Israel had “rest on every side” (1 Kings 5:4). Much later, Hag. 2:7–8 (see notes there) foretold that one day the nations would bring their wealth to the temple.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 12:19 Chronicles of the Kings. See note on 1 Kings 14:19.

Syria Captures Gilead

c. 825–798 B.C.

The Syrians under Hazael continued to plague Israel during Jehu’s reign, eventually capturing all of Gilead from Aroer on the Arnon River to Bashan in the north. Later during the reign of Jehoash (also called Joash), Hazael attacked Gath on the western border of Judah, and Jehoash sent Hazael treasures from the temple of the Lord to persuade him to withdraw from attacking Jerusalem.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 12:20 Silla was probably a neighborhood of Jerusalem below “the Millo” (see note on 2 Sam. 5:9), and the house of Millo was perhaps a prominent building in the Millo.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:1–25 Jehoahaz and Jehoash. The reader is now updated on what has been happening in Israel during the reigns of those two kings whose accessions took place within Joash of Judah’s lifetime.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:1–5 the anger of the LORD was kindled against Israel. Under normal circumstances, one might expect the appearance of a prophet to announce the end of Jehu’s house because of its sins (v. 2; cf. 1 Kings 14:6–16). The divine promise to Jehu, however, is functioning like the earlier promise to David (2 Sam. 7:1–17; 2 Kings 10:30), and the Israelite royal house is for the moment being treated like the Judean royal house. The anger of the Lord is thus expressed only in the form of Syrian oppression.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:4–5 Jehoahaz sought the favor of the LORD. The language throughout vv. 3–5 is reminiscent of the book of Judges, where Israel’s recurring idolatry was followed by divine anger, expressing itself in oppression by foreigners. When Israel cried out under this oppression, God sent a savior (2 Kings 13:5; cf. Judg. 3:9, 15) to rescue them. It seems likely that the “savior” in question here is Assyria, whose interest in Syria-Palestine was rekindled in the closing years of the ninth century B.C., resulting in a measure of relief for Israel as the attention of Damascus necessarily turned to the north.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:6 the Asherah … remained in Samaria. On Asherim, see note on 1 Kings 14:15. The English translation here implies that this is the same Asherah that Ahab made earlier (mentioned in 1 Kings 16:33), which in that case must have survived Jehu’s reformation. But it could also be translated “an Asherah (once again) stood in Samaria.”

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:7–8 dust at threshing. See note on 1 Kings 22:10–12. God’s punishment is so severe that it reduces the army of Jehoahaz to little more than a remnant, as insubstantial as chaff in the breeze. On the Chronicles of the Kings (also in 2 Kings 13:12), see note on 1 Kings 14:19.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:9 The next king of Israel, introduced here as Joash, is referred to as both Joash (e.g., v. 14) and Jehoash (v. 25) throughout the rest of this chapter and in ch. 14 (e.g., 14:8–9). He is not to be confused with Joash of Judah; see note on 11:21.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:14–19 Joash (Jehoash of Israel) weeps because he thinks he is on the verge of defeat, having inherited depleted resources in chariots and horsemen from his father (v. 7). Elisha, who knows of other chariots and horsemen of Israel who are not of flesh and blood (2:11–12; 6:8–17), is able to promise the king a series of victories (three times, 13:19). The victories would have been greater in number had the king, in response to prophetic commands, been more enthusiastically obedient (“You should have struck five or six times”) to the words of the prophet (cf. 1 Kings 13:1–32). Aphek lay eastward of the main Israelite territory in Transjordan, the direction in which Jehoash shoots the arrow and from which the Syrian threat to Israel typically came.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:20–21 grave of Elisha. Tombs in ancient Israel were often dug out of soft rock, or located in caves (e.g., Genesis 23), and they were not difficult to access. It is probably important to know at this point that Elisha’s powers to resurrect live on (cf. 2 Kings 4:8–37), because as this man was thrown (Hb. shalak) into the grave of Elisha, so God will soon “throw” (or “cast”) Israel into exile in Assyria (17:20, same verb, shalak). The Israelites need to maintain contact with the great prophets of the past through obedience to their teachings if this “death” in exile is also to be followed by an unexpected resurrection (cf. Ezek. 37:1–14).

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:23–25 his covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Here is a deeper reason than the one given in 10:30 for Israel’s survival during Jehoahaz’s reign. Long before he made promises to Jehu about kingship and a covenant with David, God was dealing with Israel’s ancestors (e.g., Gen. 15:1–21; 17:1–27). That is why he kept the Syrians at bay during the reign of Jehoahaz, in spite of Israel’s sin; and that is why the equally sinful Jehoash was later able to lead Israel to something of a recovery (in a period when Hazael’s successor Ben-hadad III was preoccupied with the Assyrian threat to his north). Even until now (2 Kings 13:23), in the time that the authors are writing (after Israel’s exile), Israel remains in God’s presence.

2 KINGS—NOTE ON 13:25 Three times Joash (i.e., Jehoash; see note on v. 9) defeated him, fulfilling the prophecy of Elisha (v. 19).