EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:1–32:32 Oracles against Foreign Nations. Poised at this moment in the dramatic downfall of Jerusalem, Ezekiel’s tirade ends and the focus shifts. The fate of the city is left hanging as a collection of oracles against foreign nations is presented. While not all the oracles in this collection are dated, most seem to fall within the period 587–585 B.C. (for the exception, see 29:17). Almost every Prophetic Book includes prophecies addressed to nations other than Israel and Judah (e.g., Isaiah 13–23; Jeremiah 46–51; Amos 1–2; Zephaniah 2). Their primary theological role is to show that all peoples are under the dominion and discipline of the King of kings. Israel is uniquely God’s own, yet all nations are subject to the one true God (cf. Amos 3:2; 9:7). The fate of every nation, whether for judgment or for blessing, is in God’s hands. Implied hope for Israel is thus a secondary message of the condemnatory foreign-nation oracles. Further, the reasons for judgment found in the foreign and domestic oracles tend to cohere within a given book. In Ezekiel, just as Judah and Jerusalem are punished for impurity and oppression, so too are the foreign nations. However, Ezekiel often simply announces God’s opposition to these nations without offering an explicit rationale. The oracles are arranged in three large sections: first, Judah’s nearest neighbors are condemned (Ezekiel 25), followed by the extended collections of oracles against Tyre (chs. 26–28) and Egypt (chs. 29–32). Two smaller oracles—one against Sidon, the other looking to Israel’s regathering—are embedded at the halfway point (28:20–26). In all, seven nations stand condemned.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:1–17 Against Judah’s Neighbors. Apart from the old northern kingdom of Israel to the north, Judah had four immediate neighbors. Clockwise, they were Ammon on the northeast (vv. 1–7), Moab to the east across the Dead Sea (vv. 8–11), Edom to the south (vv. 12–14), and Philistia to the west (vv. 15–17). The oracles against these nations group into two pairs. Excluding Philistia, but including Tyre and Sidon (chs. 26–28), these nations had been part of a coalition with Judah against Babylon early in Zedekiah’s reign (see Jer. 27:3). Each of these oracles has a similar structure, with formulaic address and conclusion, as well as similar content: condemnation for contemptuous cruelty of heart toward Judah.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:1–7 Against Ammon. Ammon and Moab fell to the Babylonians much later than Judah. Clearly, talk of “coalition” did nothing to help Judah’s cause when the Babylonians overran it. Ammon receives two oracles, and the pattern is followed in the succeeding indictments: the basis of judgment is stated (because, Hb. ya‘an), the outcome announced (therefore, Hb. laken), and the recognition formula follows by way of conclusion. The Ammon oracle, then, falls into two sections, with vv. 1–5 being more detailed than vv. 6–7.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:3 The leading reason for judgment against Ammon is the insult they gave to my sanctuary—God’s own reputation is of primary concern. While land (Hb. ’adamah; see note on 7:2) of Israel is a common phrase in Ezekiel, house of Judah is not; it is used outside this chapter only at 4:6 and 8:17. “House of Israel,” by contrast, is used 83 times in Ezekiel, well over half of its occurrences in the entire OT.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:4 The agents of divine justice are the people of the East, that is, desert nomads. This both accounts for the description that follows, and implies the ironic insult that the people unconquered by mighty Babylon will fall to nomads.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:6 This second oracle is linked to the first (for, or “because,” Hb. ki) as a further indictment.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:8–11 Against Moab. For structure and general features, see note on vv. 1–7. Although the indictment is very brief, the insult to God behind the belittling of Judah (v. 8) can still be discerned.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:8 and Seir. This phrase, lacking in the Septuagint (see esv footnote), is surprising here and may be the result of a copyist’s error. Seir is consistently identified with Edom in the OT, but nowhere else with Moab. It is not mentioned in the judgment of vv. 9–11.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:9 These place names are known from sources outside the Bible. Although not leading cities themselves, they form a direct line pointing to Dibon and Aroer in the Moabite heartland.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:10 For people of the East, see note on v. 4.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:12–14 Against Edom. The intense hatred felt for Edom by later Judeans is amply attested in the OT, e.g., Ps. 137:7; Jer. 49:7–22; Lam. 4:21–22. In the OT, Edom often serves as the chief representative of hostility to God and his people. The accusation of taking vengeance (Ezek. 25:12) coheres with this wider picture. The locations of the cities Teman and Dedan are not certain, but the suggestion that they represent the extremities of Edom (from … to) makes good sense. Assigning my people Israel (v. 14) to be the agent of God’s wrath is not paralleled elsewhere in Ezekiel, but it does have the ring of poetic justice against this traditional foe.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 25:15–17 Against Philistia. Philistia had already been subdued by Nebuchadnezzar before the campaigns against Judah. It was thus not in a position to be part of the conspiracy planned in Zedekiah’s day (see note on vv. 1–17). This oracle is very much an echo of the preceding one. The Cherethites (v. 16) were coastal dwellers, identified with the Philistines also in Zeph. 2:5. Use of their name also provides a pun on their punishment: in the phrase cut off the Cherethites, the verb and the proper noun both have the same three consonants (k-r-t) in their root (Hb. wehikrati ’et-Keretim).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:1–28:19 Oracles against Tyre. The Tyre oracles are neatly divided into three large segments by the concluding refrain at 26:21, 27:36, and 28:19. With further subdivisions, there are seven units in all. This lengthy collection, surpassed only by the Egypt oracles, immediately raises the question, why so much about Tyre? The answer seems to be that, of the states addressed by Ezekiel, only Tyre and Egypt had the power to withstand Babylon: Egypt’s power was military, Tyre’s was economic. This latter factor is especially prominent in Ezekiel’s oracles. Some have claimed that the Tyre oracles, especially ch. 26, are examples of unfulfilled prophecy. Ezekiel announces the devastation of Tyre at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar (26:7–13). Tyre eventually capitulated but was not destroyed, as Ezekiel eventually knew (29:17–20). How is this so-called “failure” of the prophetic word to be explained? Some recent interpreters have preferred to identify Alexander the Great’s victory over Tyre in 332 B.C. with Ezekiel’s prophecy. This interpretation is unsatisfactory, however, because it does not do justice to the expectation that Babylon would destroy Tyre (cf. 26:7). Others appeal to God’s sovereign freedom, claiming he is able not only to carry out a threat but also to relent, as with Nineveh in Jonah 3. However, there is no suggestion that Tyre repented as did Nineveh, and this approach renders the interpretation of prophecy quite arbitrary. A third strategy lays emphasis on the element of promise rather than prediction: no matter the actual outcome, the real intent was to subject Tyre to God’s sovereignty by the prophetic word. However, this reading is unsatisfactory in that it seems to render insignificant the details of Ezekiel’s language. A further possibility is to read Ezekiel 26 along the lines suggested in ch. 16, that is, that metaphorical language should not be confused with literal. Since much of this prophecy is metaphorical, one should not look for literal fulfillment. Finally, it is also clear that biblical prophecy is not necessarily exhausted in a single historical horizon (cf. Jeremiah’s 70 years [Jer. 25:12; Dan. 9:2, 20–27]). So too here, Tyre’s initial reduction in Ezekiel’s day (see note on Ezek. 26:1–21) was but the firstfruits of the unfolding of God’s judgment on Tyre. The exposition here seeks to steer carefully through these difficulties.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:1–21 Against Tyre. The prophet announces the destruction of Tyre at the hands of the Babylonians in four oracles grouped into two pairs, each linked by the Hebrew ki (vv. 7, 19; “for,” “because”; see 25:6): 26:1–6 and 7–14 look toward Tyre being razed; vv. 15–18 and 19–21 stand imaginatively on the other side of destruction, depicting reactions to Tyre’s demise. To the claim that the prophecies in ch. 26 were never fulfilled, the best answer recognizes that the prophecy against Tyre in vv. 3–14 is a complex one. It combines elements that would be fulfilled in the attack of Nebuchadnezzar (he besieged Tyre for 13 years, from 585–572 B.C., an attack described in vv. 7–11), and in the subsequent attack and conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 (this provides a fulfillment for the complete destruction predicted in vv. 3–6 and vv. 12–14). OT prophecies often contain different elements that are fulfilled in the near future and in the more distant future. In addition, some parts of ch. 26 were not even fulfilled until a time later than Alexander (see note on v. 14).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:1–6 Apart from the date formula (see note on v. 1), this unit bears striking similarity to those of ch. 25 and thus serves as a “hinge” between that sequence on Judah’s nearest neighbors (see note on 25:1–32:32) and this larger complex of Tyrian oracles. Like those nations, Tyre had been involved with the coalition referred to in Jer. 27:3, and now is censured for its insult to and exploitation of Jerusalem (Ezek. 26:2).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:1 The date formula lacks the month, and so cannot be fixed with precision. It falls within the span of 587/586 B.C. According to Josephus, Nebuchadnezzar’s siege against Tyre was launched around 586/585 B.C. and lasted 13 years (Jewish Antiquities 10.228).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:3 The agents of destruction here are many nations, described metaphorically as the crashing of the sea and its waves. The description that follows continues this figurative language. This was fulfilled partially by the siege of Nebuchadnezzar, and then more fully in the conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. (see note on 26:1–28:19). Both Nebuchadnezzar and Alexander the Great led the military forces from “many nations” whom they had conquered. Nebuchadnezzar’s title “king of kings” (26:7) reflected this reality and echoes historical records of Assyrian royal language. Alexander the Great, in attacking Tyre, had the help of 80 ships from Persia and 120 from Cyprus, in addition to soldiers from other nations.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:4–5 The location of Tyre in the midst of the sea, often seen in extrabiblical sources as a sign of its security, is now described with derision (see also v. 17). In the conquests of Alexander the Great, Tyre was indeed destroyed and made like a bare rock.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:6 Her daughters on the mainland are the villages on the mainland that were opposite the island city of Tyre. They were destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar and again by Alexander.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:7–14 This oracle develops its briefer partner (vv. 2–6), adding specificity and concreteness to the imagery as its message is reinforced. Some repeated vocabulary contributes to their coherence (“walls” and “towers,” vv. 4 and 9; “bare rock,” vv. 4 and 14; “a place for the spreading of nets,” vv. 5 and 14).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:7 Nebuchadnezzar (II) of Babylon reigned 605–562 B.C.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:8–10 Ezekiel’s oracle includes many of the traditional elements of siege warfare, at the same time conjuring up much of its claustrophobia. daughters. See note on v. 6.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:12 That Tyre’s wealth should be subject to plunder is not only inevitable in ancient warfare, it is also poetic justice, given its gloating (v. 2). However, by the time that Nebuchadnezzar conquered Tyre, much of value had been removed by sea, and apparently little wealth remained after 13 years of siege (see 29:18). Later, Alexander the Great conquered Tyre by building a 2,600-foot (800-m) causeway from the mainland out to the island fortress, thus fulfilling the prophecy of this verse, your stones and timber and soil they will cast into the midst of the waters. (These materials came from the destruction of the city’s settlements on the mainland, 26:6, 8.)

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:14 You shall never be rebuilt. Tyre was rebuilt and reconquered several times after Alexander the Great, so the complete fulfillment of this prophecy did not come immediately. The modern city of Tyre is of modest size and is near the ancient site, though not identical to it. Archaeological photographs of the ancient site show ruins from ancient Tyre scattered over many acres of land. No city has been rebuilt over these ruins, however, in fulfillment of this prophecy.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:15–18 Off the island itself, the vantage point is now that of the mainland cities (cf. vv. 6, 8) as their princes mourn the downfall of formerly majestic Tyre. The lament itself appears in vv. 17–18, an outpouring of fear-induced grief. Laments feature prominently in the Tyre and Egypt oracles (cf. 27:1–36; 28:11–19; 32:1–32).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 26:19–21 The final oracle anticipates the closing of the entire foreign-nation oracle collection, which bemoans the arrival of the nations in the underworld place of the dead (32:17–32; cf. Job 3:13–19). The repeated phrase those who go down to the pit (twice, Ezek. 26:20; see 32:18) refers to the state of those whom death has separated from communion with God (cf. Isa. 38:13).

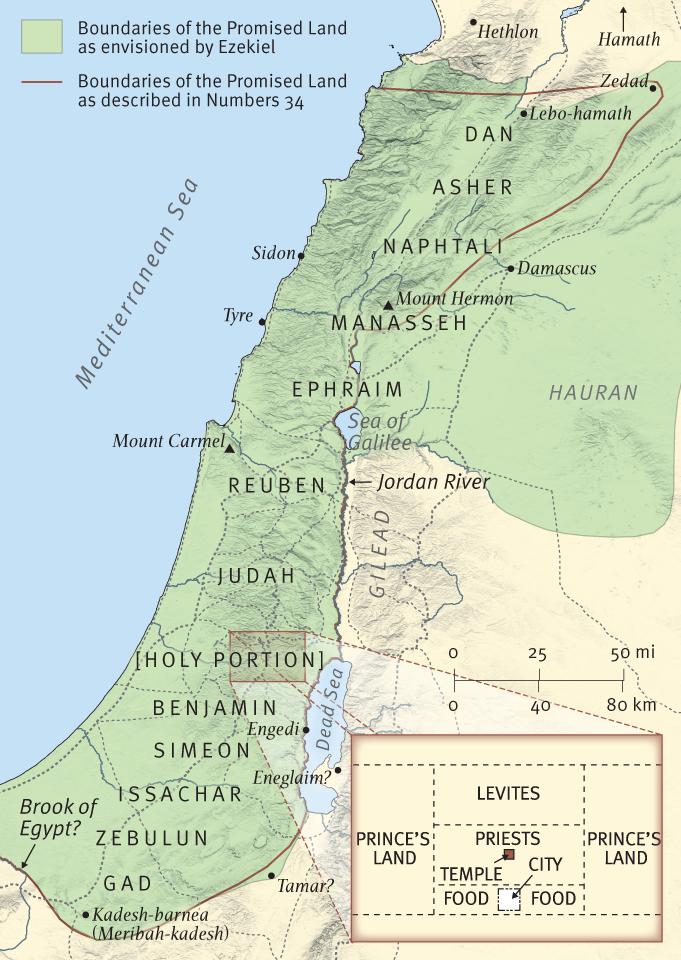

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 27:1–36 A Lament against Tyre. This remarkable passage, the second installment of the Tyre series, is both simple and complex. Its simplicity lies in the unfolding narrative line, set in the form of a lament. Its complexity is in the wealth of detail and technical artistry displayed throughout. Tyre is likened to a merchant ship, whose fortunes are traced from the shipyards (vv. 4–7) and crew (vv. 8–11) to its tragic loss at sea (vv. 26–27) and the outcry its loss provokes (vv. 28–32a)—all culminating in a lament-within-a-lament (vv. 32b–36). A lengthy aside in the middle of the chapter (vv. 12–25) offers a sort of commercial litany, as Tyre’s many trading partners and their wares are dolefully itemized (see map). A striking feature of the lament, lending to its somber tone, is the complete lack of invective; nor is God mentioned within the oracle. In spite of some obscure details and uncertain place names, the force of the lament is clear enough: for all its splendor and in spite of its wealth, Tyre is doomed.

Tyre’s International Trade

c. 587 B.C.

During Ezekiel’s time, the city of Tyre had grown very wealthy due to its strategic island location in the middle of the ancient Near East. Tyre served as a sort of international commodities exchange for the surrounding nations, and Ezekiel’s extensive list of various nations who traded or collaborated with Tyre (shown here) gives a glimpse of the city’s great influence. Merchants from as far away as Persia, southern Arabia (including Sheba, etc.), and perhaps even Spain (a possible location of Tarshish) traded their goods there.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 27:5–6 The wood comes from the regions corresponding to modern Lebanon (Senir is north of Mount Hermon) and the Golan Heights (Bashan).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 27:8–9 The mariners came from various Phoenician coastal cities.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 27:10 Persia (modern Iran), Lud (probably in Asia Minor), and Put (Libya) mark out a vast geographical triangle from which mercenaries were drawn. The actual location of Lud is uncertain. The most common view is that Lud is Lydia (a region in western Asia Minor, later a Roman province and now part of modern Turkey), but some place it in northern Africa.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 27:11 The identifications of the final group of place names are uncertain. They serve to complete the beauty boasted of in vv. 3–4.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 27:12–25 The impressive range of merchant connections begins and ends with Tarshish, probably in southern Spain, implying that Tyre’s trade stretched along the whole extent of the Mediterranean.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 27:13 The names Javan, Tubal, and Meshech are first found as sons of Japheth in Gen. 10:2 (repeated in 1 Chron. 1:5). But in Ezekiel’s time the names signified geographical regions, perhaps peopled by descendants of those men. The primary import of the names here is to signify the far-off places with which Tyre did business. More specifically, “Javan” (Hb. Yawan) was a collective OT name for Greece or the Greeks (the same Hb. term is translated “Greece” in Dan. 8:21; 10:20; 11:2; Zech. 9:13). “Tubal” refers to ancient Tabal, in what is now central Turkey (the province of Cappadocia in NT times). “Meshech” refers to a people known in Greek literature as the Moschoi, who settled in an area on the southeast edge of the Black Sea (the northeastern part of modern Turkey).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 27:14 Beth-togarmah was located in the region of Carchemish and Harran.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 27:32–36 The lament raised by the onlookers (vv. 28–29) offers a miniature version of the whole chapter: wealthy Tyre, who enriched the entire economy, has sunk, instilling fear in the watching nations.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:1–19 Against Tyre’s King. The final part of the Tyre oracles brings the movement of Tyre’s hubris to a climax. While its pride was implied throughout ch. 26, and led to self-exaltation in ch. 27, here Tyre claims deity (28:2). Two distinct laments are presented: vv. 1–10 assail the pride of Tyre’s king; vv. 11–19 present him as a primordial being fallen from grace. In neither case does a particular king seem to be in view; rather, Tyre is personified through its monarch. Tyre’s wealth is constantly in view, as it has been throughout chs. 26–27, intrinsically bound up with its opposition to God.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:1–10 Although cast in lament form, the structure of this oracle takes the familiar pattern of grounds of indictment (vv. 2b–6) and outcome (vv. 7–10) with a formulaic conclusion. Pride is at the center of the charge, reinforced by the repetition of the word “heart” (Hb. leb or lebab), used eight times in the span of vv. 2–8.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:2 The king of Tyre is designated prince (Hb. nagid). It could simply be a stylistic variation for “king” (cf. Ps. 76:12, where it is a poetic parallel to “kings”). If it has further value beyond a simple designation for a national leader, this term could imply a divinely appointed, charismatic leader as it does in older Hebrew usage. If so, it further emphasizes the hubris of this figure.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:3 On Daniel, see note on 14:14, 20.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:4–5 Trade and commerce were the foundation of Tyre’s wealth, but then that wealth led Tyre to become proud, which led to aspirations to deity.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:6 The entire because … therefore structure (vv. 2, 7) is distilled in this single “hinge” verse.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:7–8 Here the agents of divine punishment are unnamed foreigners, elsewhere identified with the Babylonians (26:7; 29:18; cf. 30:10–11). For descent to the pit, cf. 26:19–21.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:11–19 The final anti-Tyre oracle adds a plethora of detail. As in ch. 27, there is no indictment (like in 28:1–10) but rather a narrative lament culminating in inevitable doom. The imagery is kaleidoscopic. Tyre is likened to a second Adam, clearly a created being (vv. 13, 15) and yet a “cherub” (v. 14). It is in the “garden of God” in v. 13, and on the “mountain of God” in vv. 14 and 16. Some would see v. 17 as a poetic allusion, wherein Ezekiel likens the downfall of the proud king of Tyre to the fall and curse on Satan in Gen. 3:1–15. At minimum, the extravagant pretensions of Tyre are graphically and poetically portrayed (cf. note on Ezek. 28:4–5), along with the utter devastation inflicted upon Tyre as a consequence (vv. 18–19).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:13 Putting Tyre in Eden, the garden of God, forges a link with Genesis 2–3, but avoids connecting pagan Tyre with “the garden of Yahweh,” as in Gen. 13:10 and Isa. 51:3. Some of the precious stones in this difficult list cannot be identified with confidence. It parallels similar lists in Exodus of the composition of the breastpiece of the priestly garments (see Ex. 28:17–20; 39:10–13).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:14 As a guardian cherub, Tyre is like the cherubim guarding Eden (Gen. 3:24) rather than the “living creatures” seen in Ezekiel 1–3 and 8–11, who are throne-bearers.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:15–16 Tyre was blameless, as was Job (Job 1:1; 12:4). But trade, coupled with violence, triggers the downfall of this previously admirable creature; see also Ezek. 28:18.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:18 The priestly allusions are further developed as the sanctuaries are profaned.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:20–23 Oracle against Sidon. Sidon is often mentioned alongside Tyre (e.g., Jer. 25:22; 47:4; Joel 3:4; Zech. 9:2), an association that survived into NT times (e.g., Matt. 11:21–22; Luke 10:13–14). This brief oracle is, on one hand, reminiscent of the collection in Ezekiel 25 (cf. 25:1–2 and 28:20–21) and continues the geographical sequence begun there. On the other hand, it contains no accusation against Sidon, but simply announces divine opposition to it.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:22 Behold, I am against you will also be the opening formula in the Egypt oracles (29:3), forming a link to the following collection. Concern for God’s glory and holiness picks up the underlying theme of ch. 25 (see note on 25:3).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:23 This trio of pestilence, blood, and sword is characteristic of Ezekiel.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 28:24–26 Israel Gathered in Security. Strategically, this hopeful note is struck precisely at the halfway point in the collection of foreign-nation oracles. Verses 24 and 26 make explicit what is sometimes implicit and often simply absent from foreign oracles: the subduing of God’s enemies will result in the well-being of God’s own people. Since “scattering” is one of the primary judgments on Israel (e.g., Lev. 26:33; Deut. 28:64), “gathering” (Ezek. 28:25) is one of God’s distinctive saving responses (cf. Deut. 30:3), a theme to be repeated throughout the latter part of Ezekiel’s book. The peaceful settlement in a bountiful land (Ezek. 28:26) anticipates the prophecy of the “covenant of peace” (34:25–30).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:1–32:32 Oracles against Egypt. The seventh and last of the nations to be addressed, Egypt (like Tyre) receives seven oracles, clarified structurally by the date formula that heads all but one of them (30:1 is the exception). The Egypt oracles equal in bulk the rest of the collection in chs. 25–28. If the chief interest in Tyre was economic, the leading issue for Egypt is military power. As seen in chs. 17 and 19, Egypt was still closely bound up with Judean affairs at this time. The Egyptian king during the period covered by these oracles was Hophra (reigned 589–570 B.C.), named in the OT only in Jer. 44:30. His aspirations over this region were instrumental in fomenting Zedekiah’s rebellion against Babylon. This accounts both for the belief that Judeans fleeing Babylonian reprisals would find safety in Egypt (Jeremiah 42–43) and Ezekiel’s condemnation of Egypt’s opposition to the Babylonians, who wielded the sword of the Lord’s wrath.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:1–16 Against Pharaoh. The two leading charges against Egypt come out clearly in this initial trio of oracles. Verses 1–6a portray the hubris of Egypt putting itself in the place of God, while vv. 6b–9a condemn it for its part in the destruction of Judah. The third section returns to the charge of hubris and subjects Egypt in a more extended way to the retributive hand of God. The date of these prophecies in v. 1, under which these oracles are gathered, equates to January 587 B.C., just after Babylon laid siege to Jerusalem, and after Hophra came to power in Egypt. In several prophecies, including this one, God shows Ezekiel what was happening hundreds of miles away (see note on 24:2).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:1–6a Ezekiel delivered this oracle against Pharaoh king of Egypt, soon after Hophra ascended the throne (in 589 B.C.).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:3 The confrontational formula, Behold, I am against you, also appears at 28:22, there addressed to Sidon, the last nation to be dealt with before Egypt (see also 26:3). The figure of the dragon takes Ezekiel’s language to the boundary between the natural and supernatural realms. At one level, this is a symbolic name for the crocodile in the Nile (also 32:2), but at another level it represents a cosmic creature opposed to the rule of God and defeated by him (e.g., Ps. 74:13; Isa. 27:1; 51:9). The claim to be the maker of the Nile amounts to arrogation of divinity (cf. Tyre; Ezek. 28:2).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:4–5 hooks in your jaws. The judgments against Pharaoh match the metaphorical framework of the accusation (“great dragon … in the midst of his streams”; v. 3).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:6b–9a The second accusation is cast in the familiar because … therefore (Hb. ya‘an … laken) form seen often in Ezekiel. A river-related metaphor is again used; this time, however, Egypt is the staff of reed (i.e., a useless staff made from a flimsy reed) that treacherously fails to give support. In all likelihood this metaphor relates to the events narrated in Jer. 37:5–11 and echoes the taunt hurled against Hezekiah’s Jerusalem by the Assyrians (2 Kings 18:21).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:9b–16 A brief because section (v. 9b) repeats the accusation against Egypt in v. 3 before a much longer and literal judgment speech (vv. 10–16). The judgment has typical elements in vv. 10–12 that coincide with those leveled against Israel and Judah themselves. That Egypt should also be favored with restoration (vv. 13–16) is more surprising, but not unparalleled (see Jer. 46:26; cf. Jer. 48:47; 49:6, 39). Restored Egypt will, however, be cured of its hubris (Ezek. 29:14–15). Isaiah describes a future even farther off, with the Egyptians brought to knowing the true God (Isa. 19:18–25).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:10–11 The desolation of Egypt, which lasts forty years, strikes at the assumption that the annual inundations of the Nile that supported Egypt guaranteed its perpetual well-being. The location of Migdol is unknown, but together with Syene (Aswan) it bounds Egypt north and south. Cush is the region roughly corresponding to modern Ethiopia. Most interpreters think this “forty years” does not refer to any specific period of time but is a symbolic number showing the parallel to the wandering of Israel in the wilderness for 40 years, or just symbolizing the completeness of God’s judgment. Some interpreters have taken it to refer to the period when Egypt was under Babylonian rule from 568 to 525 B.C. (see note on v. 19).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:14 Ancient Egyptian tradition located its national origins in the region of the Upper Nile where Pathros is located. The reference suggests that Ezekiel was well informed of Egyptian lore. Jewish mercenaries had been in the region for many years. Judean refugees fled there with Jeremiah (Jer. 44:15).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:15 they will never again rule over the nations. Egypt never rebuilt the empire it once had.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:17–21 Nebuchadnezzar and Egypt. This is the latest-dated oracle in the book, coming in April 571 B.C. Nebuchadnezzar’s siege of Tyre had ended with Tyre intact, albeit subject to the Babylonians, who had little to show for 13 years of effort. (On this episode, see note on 26:1–28:19.) The concluding remark in 29:20 that they worked for me (i.e., Babylon was doing the Lord’s work in besieging Tyre), emphasizes the point of view running through Ezekiel’s foreign-nation oracles: opposition to Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon was opposition against the agents of God’s wrath. Thus the labor they expended (v. 18) was to be rewarded with wages (v. 19) provided by God, but now coming from Egypt (v. 20).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:19 I will give the land of Egypt to Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon. This prophecy was given in 571 B.C. (see note on vv. 17–21), and Nebuchadnezzar conquered Egypt in 568 (this is described in detail in Jeremiah 43–44 and also recorded in Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 10.180–182). Egypt was subsequently subject to Persian rule (beginning in 525 B.C.), was conquered by Alexander the Great and made part of his empire in 332, and was conquered by the Romans and became part of the Roman Empire in 31.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 29:21 The final note of promise appears to be for Ezekiel himself. The phrase open your lips does not relate to Ezekiel’s muteness (which would have ended years earlier than the events foretold here; see 33:21–22). Rather, it affirms that, after all those years, Ezekiel’s prophetic ministry was to be vindicated.

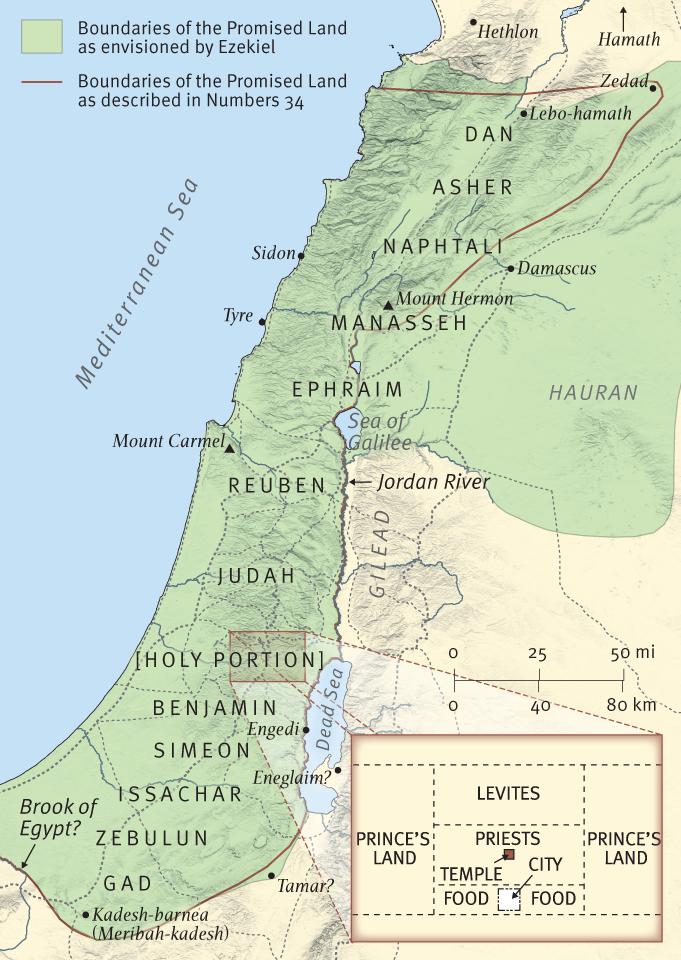

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 30:1–19 Lament for Egypt. The third of the seven anti-Egypt oracles is the only one undated, and it contains no written basis for dating. It is comprised of four relating prophecies, each introduced by Thus says the Lord (vv. 2, 6, 10, 13) and each echoing motifs and ideas seen elsewhere in Ezekiel’s oracles. Together they announce the fall not only of Egypt but also of her allies, and again by the hand of Nebuchadnezzar (v. 10). Much like in the Tyre oracle in ch. 27, there is no specific charge brought against Egypt here; rather, God’s judgment is simply pronounced. See map.

Ezekiel Prophesies against Egypt

c. 571 B.C.

Ezekiel prophesied that even the great nation of Egypt and its allies would fall to the Babylonians, who already occupied the land of Israel and Judah. The rule of the Babylonians would eventually extend as far as the borders of Cush, referred to elsewhere as Ethiopia. None of the great cities of Egypt would be spared Babylon’s wrath.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 30:2–5 The cry of the day (v. 2) and the announcement that the day is near (v. 3) point to the “day of the LORD” concept, developed in 7:10–27 (see notes there). The bare announcement of the day of the LORD finds its counterpart in the time … for the nations, explained almost at once as a time of doom. Ezekiel combines this motif with the “sword of the Lord” in a subtle way at 21:8–10, but here the connection is overt with the reference to the sword in 30:4.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 30:4–5 On Cush, see 29:10. Put refers to the same region as Libya; for it and Lud, see note on 27:10. The Hebrew underlying Arabia (‘Ereb) literally means “mixed peoples.” This geographical survey anticipates the central thrust of the next unit.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 30:6–9 Here the allies of Egypt come into focus. They shall share the same fate as their master. On Migdol to Syene, see 29:10. The language of desolation also forges a link back to 29:8, 10.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 30:10–12 The explicit identification of Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians as the agents of God’s wrath links to 29:17–20, although it is likely that this unit comes from an earlier period. Likewise, the drying up of the Nile (30:12) links back to 29:9b–12.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 30:13–19 The knowledge of Egypt demonstrated in 29:14 is seen in this unit’s plethora of place names, often compared to Mic. 1:10–15. To each place is joined a facet of the judgment to fall upon it. This litany of divine actions amounts to a comprehensive rejection of Egyptian religion and politics. There is no clear geographical organization to the list, but where information is available, the judgments appear to be appropriate to the place. Memphis (Ezek. 30:13, 16) was the capital of Lower Egypt, south of the Nile delta. On Pathros (v. 14), see 29:14. Zoan (30:14), Pelusium (vv. 15–16), and Tehaphnehes (v. 18) were in the northeastern delta, with Pelusium being a strategic fortress at the border with the Sinai. Thebes (vv. 14–16) was capital of Upper Egypt, thus holding great symbolic value. On and Pi-beseth (v. 17) were in the southeastern delta, near the land of Goshen, the location of the sojourn of the people of Israel before the exodus (Gen. 45:10). Some of the judgments (Ezek. 30:18) provide allusions to the exodus plagues.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 30:17 The Hebrew text has only a feminine pronoun (“they”), and the esv supplies the referent as women, anticipating the ending of v. 18; it could also be “cities,” which is grammatically feminine (see esv footnote).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 30:20–26 The Kings of Egypt and Babylon. The dates return in this fourth Egypt oracle, locating this unit in April 587 B.C. This oracle contrasts the weakness of Hophra’s forces with the might of Babylon. The direct confrontation between these kings has been announced in v. 10. The sword (vv. 21–22) will fall from the hand of Hophra, but Nebuchadnezzar wields the sword of the Lord (v. 24; cf. 29:11, 19). Again, the king of Babylon does God’s work (29:20).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 30:23 scatter … and disperse (see also v. 26). This language appeared in 29:12. The fear of dispersion is one of the most deep-seated in the OT (e.g., Gen. 11:4; cf. Ezek. 28:24–26).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 31:1–18 The Fall of Pharaoh. Ezekiel’s fifth oracle against Egypt dates to June 587 B.C., thus only a few weeks after the preceding unit. Here the prophet points to Assyria as an object lesson to Egypt. In its dying days, the once-mighty Assyrian Empire looked to Egypt for help against the mounting power of Babylon (c. 610 B.C.). Even together they could not withstand the Babylonian onslaught. That had been a mere 23 years earlier, well within living memory. In Isaiah’s prophecies, given earlier still, Assyria—pride personified—was chopped down by the axe of the Lord (Isa. 10:5–19). This, the prophet says, is the fate awaiting Egypt. The motif of the “cosmic tree” that harbors the nations in its branches uses elements from ancient mythology, much as does the oracle of Tyre in the “garden of God” (see Ezek. 28:11–19).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 31:2 The notice of Pharaoh and his multitude is repeated in v. 18b, but there as a statement rather than an address. Likewise, the rhetorical question in v. 2b is posed again and expanded in v. 18a. This provides an effective frame around the intervening verses.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 31:3 Some find the reference to Assyria problematic, expecting rather immediate application to Egypt. However, the text is stable and clear, and there is no support from the ancient translations for suggested textual corrections (which are themselves not free from interpretative problems).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 31:8–9 The garden of God is mentioned three times. As in 28:13 (see note), this garden is identified with Eden (also 31:16, 18). I (God) made it beautiful, leaving no room for self-exaltation (v. 9).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 31:10–14 Pride precedes the fall, here brought about by the agency of a mighty one of the nations (v. 11), paralleled by the most ruthless of nations (v. 12), elsewhere a cryptic code for Babylon (28:7). Those who once prospered in Egypt’s shadow now languish on its remains; no longer is it able to sustain life. The closing mention of those who go down to the pit (cf. 26:19–21) provides a bridge into the next paragraph.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 31:15–17 While the judgment entailed in these verses echoes the content of those immediately preceding, the attention to Sheol (the place of the dead) prepares the way for the longer reflection on this theme in 32:17–32.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 31:18 Pharaoh … multitude. See note on v. 2.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:1–16 Lament over Pharaoh. Like the preceding oracle, this one is firmly bounded by a repeated element, the call to “lament” (vv. 2, 16)—although the poetic form itself is not strongly marked by this genre. The poem turns on the identification of Pharaoh as a “dragon” (v. 2), recalling 29:3 (see note). It is followed by two pronouncements of divine activity, one in 32:3–10, which develops the metaphorical world of the “dragon,” and the second in vv. 11–15, which more briefly and literally applies divine judgment to Egypt.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:1 The date formula corresponds to March 585 B.C., placing it some time after the fall of Jerusalem and its defining moment in Ezekiel at 33:21, breaking the book’s chronological sequence in order to follow the thematic gathering of the foreign-nation oracles into a single collection.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:2 Egypt may fancy itself a lion, a self-delusion like that in 29:3, but it is a dragon, the cosmic beast being associated with the Nile’s crocodile (again, see 29:3). In the verses that follow, the cosmic and natural elements intermingle, although the metaphorical language predominates.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:3–6 Slaying the monster affects the entire landscape. The gorging of the birds and beasts in v. 4 is a stage beyond settling on the remains of the “cosmic tree” in 31:13.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:7–8 The “cosmic” scope of the language is obvious in these heavenly effects of the dragon’s death. The darkness on your land again provides allusions to the exodus story (cf. 30:13–19; also Ex. 10:21–23).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:9–10 The political dimension is introduced. The more literal language, along with the reference to my sword, provides a transition to the second unit.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:11–13 Yet again the agent of God’s punishment is identified as the king of Babylon (v. 11), once again bearing the sword of the Lord (v. 10). Here, the demise of Egypt provides an opportunity for nature to recover from its corrupting influence, with the “waters” and “rivers” of v. 14 pointing back to the initial picture drawn in v. 2.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:16 The closing verse of the oracle also connects with v. 2, providing a literary envelope for the whole oracle.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:17–32 Egypt’s Descent to the Pit. The seventh and final oracle against Egypt—and the last of the entire foreign-nation oracle collection—returns to a theme introduced briefly in an oracle on the sinking of Tyre in 26:20, and already used against Egypt in 31:14, 16. In a grand finale, all the nations are gathered together in the pit (32:18), in Sheol, the place of the dead. Egypt joins them there, Pharaoh receiving cold comfort from the welcome he receives (v. 31). Ezekiel is instructed to wail (v. 18), not to “lament,” so this dirge lacks the poetic structure of the lament genre. After a leading rhetorical question, which serves as a thematic superscription, Egypt’s reception in Sheol is described in terms of the “welcoming party”—five nations already languishing there. In drawing the nations together in this place over which God alone has power, Ezekiel again demonstrates God’s sovereignty, poised at this juncture of the book when Judah’s own death seems assured.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:17 This oracle occurs two weeks later than the previous one (fifteenth day; cf. “first day,” v. 1).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:19 The rhetorical question with its implied irony alludes to Tyre’s proud claim in 27:3, but is framed in a way similar to the question posed to Egypt in 31:2b. The Egyptians practiced circumcision, thus their place with the uncircumcised would be cause for deep shame.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:22–23 Assyria is the chief of the slain (cf. ch. 31), but in the uttermost parts of the pit. Ezekiel’s Sheol knows gradations of shame, and Assyria’s appears to be the deepest.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:24–25 Elam, in modern terms bordering southern Iraq to the east, was not at this time a notable political power. Its inclusion may be to mark a remote eastern edge of the nations gathered.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:26–27 Not … with the mighty implies that residence in Sheol includes distinctions of shame and honor (cf. note on 32:22–23).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:28 The focus of the mourning returns briefly to address Egypt directly.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:29–30 Edom (v. 29; see 25:12–14) and the Sidonians (32:30; see 28:20–23) were Judah’s near neighbors to the southeast and northwest respectively.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 32:31–32 The oracle returns full circle (cf. vv. 18–21), affirming Pharaoh’s destiny.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:1–39:29 After the Fall of Jerusalem. Following the central collection of foreign-nation oracles, the focus returns to Judah (or “the house of Israel” in Ezekiel’s preferred phrase). Before Jerusalem’s fall, warning and doom dominated Ezekiel’s message—although hints of hope were not absent. In the wake of Jerusalem’s destruction (33:21–22), the balance is reversed. With false hopes shattered, Ezekiel’s oracles now point to the true source and proper shape of life renewed. This reorientation is not an abrupt “about face” but rather a gradual turning that revisits the realities of life under judgment while building toward the solid promise of a renewed and permanent relationship of life with God.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:1–20 Reminders. On the brink of hope, there is a brief pause to forge links back to chs. 1–24, and to remind Ezekiel and his audience of their mutual responsibilities: 33:1–9 again describes the role of the prophet in terms of the “watchman” seen also in 3:16–21; 33:10–20 offers a different edition of the teaching on individual responsibility seen in 18:21–29.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:1–9 The Watchman (Reprise). See also 3:16–21. God, prophet, and people are inextricably bound together in these verses. The role of the watchman (33:2, 6, 7) dominates. He must act on what he sees (vv. 3, 6). Yet v. 2 frames the parable of vv. 2–6 about the land itself, and the whole oracle (vv. 2–9) is addressed to your people. They are responsible to attend to the watchman’s warnings (vv. 4–5). The watchman must exercise vigilance to discern the actions of God (If I bring the sword … and if he sees, vv. 2–3), but God himself speaks the divine word to the prophet (v. 7). Verses 7–9 are almost identical to 3:17–19.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:2 On God’s own sword, cf. 21:3 and the context there.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:10–20 Moral Responsibility (Reprise). As the reminders continue, the emphasis falls on the people. This passage parallels that of 18:19–29 (see the notes there), which concluded with a call to repentance (18:30–32). Here, no such call is issued. But the following oracle represents the most important juncture in the prophet’s ministry.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:11 I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked. The Bible is clear that God will punish sin and vindicate his holiness and justice. At the same time, God feels sorrow over the punishment and death of creatures created in his image.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:17 your people say, “The way of the Lord is not just.” When people do wrong, they are quick to complain about God rather than admitting their own sin.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:21–22 The Fall of Jerusalem. This brief notice has an importance out of proportion to its size. It provides the hinge on which the main structure of the book turns. The readers, and Ezekiel, have had preparation for this precise moment: Ezekiel’s muteness was first encountered in 3:22–27, and a marker had been put down when the siege of Jerusalem began (24:1–2, 25–27). The date is now January 585 B.C., about five months after the fall of the city. The arrival of the fugitive confirms the word spoken at the beginning of the siege (24:25–27), affirms Ezekiel’s prophetic ministry, and establishes the work of God in bringing it about. It also gives weight to the words that follow.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:23–33 Culpability. Although the movement toward restoration has begun, words from the LORD are castigating Judeans at home (vv. 23–29) and abroad (vv. 30–33) regarding ungodly living.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:23–29 A Word for the Homelanders. Those left in Judah after its fall are addressed. The scenarios described (vv. 24–26) overlap with those listed in ch. 18. The connection is appropriate. Chapter 18 challenges the notion that ancestry ensures (or prohibits) blessing, and the claim confronted here, in part, is that “paternity” implies possession. Rather, the desolation of the land (33:27–29) is directly linked to the people’s own abominations.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:24 The patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob) are rarely mentioned by the prophets. For this invocation of Abraham, cf. Isa. 41:8; 51:2. The Judeans’ “logic” of arguing from the one to the many here is deeply flawed. On possession of land at this time, see also Jer. 39:10.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:25–26 On this catalog of crimes, cf. notes on 18:5–18. You eat flesh with the blood. The Hebrew is literally “you eat over the blood,” an idiom used also in Lev. 19:26. The reference is to illicit sacrifice. Ezekiel’s rhetorical questions (shall you then possess the land?) imply the terms of the covenant that the homelanders have seemingly forgotten.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 33:30–33 A Word for the Exiles. If the “implied” audience for vv. 23–29 was the homelanders, the “real” audience listening in was Ezekiel’s fellow exiles. Their enjoyment of the rebuke aimed at their land-hungry compatriots is cut short as Ezekiel turns to accuse them of also being marked by greed (v. 31). Compounding this, they treat prophetic words as mere entertainment (v. 32). No judgment is pronounced, but it is ominously implied (v. 33).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:1–31 Shepherds and Sheep. The move toward restoration continues by way of further warning and indictment. Ezekiel develops the picture of the community and its leaders as flock and shepherds (used throughout Jeremiah). In Ezekiel, the metaphor is seen only in this chapter and in 37:24. The brief oracle in Jer. 23:1–4 focused only on the shepherds, and this is Ezekiel’s starting point (Ezek. 34:1–16)—but here Ezekiel goes on to address the sheep (vv. 17–31).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:1–16 Wicked Shepherds and the Good Shepherd. The passage moves from condemnation (vv. 1–10) to restoration (vv. 11–16). As in Jeremiah, the punishment of negligent shepherds (the leaders of the people) precedes the promise of a faithful shepherd, although the two prophets differ on details. The passage is emphatic that the role of the shepherd is to ensure the safety and well-being of the flock. This has been the distinctive failure of Judah’s leaders.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:1–10 Often in Ezekiel a concise accusation leads to a lengthy description of consequences and punishments. Here, the proportions are reversed. The situation is presented in vv. 1–6, it is summarized in vv. 7–8, and judgment is announced in vv. 9–10.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:2 The metaphor of shepherds for the rulers of the community has ancient roots and was widespread in the ancient Near East (e.g., on Tammuz, 8:14–15). In the OT, David is the shepherd-king par excellence (2 Sam. 5:2; Ps. 78:70–72), but preeminently, it applies to God himself (e.g., Ps. 80:1). Jesus identifies himself as the “good shepherd” (John 10:11, 14). feeding yourselves. The failure here is not simply a matter of neglecting the sheep but of benefiting at the cost of the flock.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:3–6 These verses pointedly describe how the shepherds misused their power by using it for their own gain rather than for the good of the people. Because of this covenant neglect (Lev. 26:33; Deut. 28:64) the sheep were scattered.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:10 No punishment is identified except that this situation must stop, and divine intervention ensures that it does (see note on vv. 11–16).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:11–16 God intervenes to reverse, step by step, the process described above. He successively undoes the damage inflicted by the failed shepherds (vv. 2–6, 8) by seeking the scattered (v. 12), gathering (v. 13) and feeding them (v. 14), and ensuring they live in security (v. 15). On the announcement of God himself as shepherd (v. 15), see v. 23. The summary in v. 16 portrays the judgment of the shepherds and the restoration of the flock as two aspects of a single work of God. In John 10:9, Jesus speaks of the sheep finding “pasture” (evoking Ezek. 34:14).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:17–31 The Flock: Problems and Prospects. The remainder of the chapter is addressed to the flock in three stages: vv. 17–22 condemn victimization within the flock; vv. 23–24 return to the provision of a faithful shepherd; and vv. 25–31 attend to the implications of renewal for the natural world.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:17–22 The structure is much like that of vv. 1–10. Behavior within the flock is described and condemned in vv. 17–19, and the consequent divine intervention is described (vv. 20–22), which includes a reiteration of the charges (v. 21). The “you” now addresses the flock rather than its shepherds.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:17–19 The previous oracle concluded with a statement of “justice” (v. 16, Hb. mishpat); this pertains not only to the rulers but also to the people themselves. The selfish greed, which not only monopolizes but also squanders the resources of the community, is “judged” (v. 17, Hb. shophet, related to mishpat). Ezekiel’s oracle anticipates Jesus’ teaching in Matt. 25:31–46.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:20–22 The description of the classes of sheep implies oppressive exploitation apart from failed leadership. The assertion of judgment that begins and ends this oracle distinguishes it from the next element in the chapter.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:23–24 Ezekiel’s announcement of a Davidic shepherd (v. 23; cf. 37:24) is similar to Jeremiah’s (Jer. 23:5–6). The covenant formula in Ezek. 34:24 affirms the relationship of God and people. Because it is in such close proximity to v. 15, some commentators see a tension between those taking up the role of shepherd: is the shepherd divine (v. 15) or human (v. 23)? The dilemma may be solved by appeal to editorial layering, or in assuming a hierarchy of divine shepherd over human shepherd. A Christological reading finds here an anticipation of the divine-human nature of the Messiah. Such a reading explains John 10:11–18, where, in claiming to be the “good shepherd,” Jesus claims to be both the Davidic Messiah (Ezek. 34:23) and the incarnate God of Israel (v. 15; cf. John 1:14). Ezekiel’s uneasiness with any king except God is seen in designating David as prince (Hb. nasi’).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 34:25–31 The covenant of peace announced in v. 25 extends the renewal of life from the human community to the natural world. These effects also come in tandem with the messianic age in Isa. 11:1–9. Covenant curses have been prominent until this point, but the covenant also entailed blessings (cf. Lev. 26:4–6; Deut. 28:8–14). They shall be showers of blessing refers not only to literal rain but also to abundant blessings from God. Ezekiel 34:31 returns explicitly to the pastoral metaphor to draw the threads of the chapter together.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 35:1–36:15 The Mountains of Edom and Israel. In so highly structured a book as Ezekiel, it seems odd that an oracle against a foreign nation should appear outside the collection in chs. 25–32. However, that collection is itself highly structured, and it is clear that the prophecies against Mount Seir (Edom) in ch. 35 are a preface to the address to the mountains of Israel in 36:1–15, and these two passages are best regarded as a single unit in two parts.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 35:1–15 Against Mount Seir. Mount Seir (v. 2) is identified with Edom (v. 15) much as Mount Zion is identified with Judah. An oracle against Edom appears in 25:12–14 (see note there), and its theme is echoed here. Edom’s excesses against the stricken Judah (which inspired such animosity) are registered and judged. (Cf. also the book of Obadiah.) There is also considerable overlap of language with Ezekiel’s earlier oracle against the “mountains of Israel” in Ezek. 6:1–7, 11–14. In this passage, the “recognition formula” (35:4, 9, 12a, 15; cf. Introduction: Style) punctuates a sequence of four related sayings. The key words “waste” and “desolation” recur throughout the passage, translating at least four Hebrew terms.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 35:1–4 The first oracle is little more than a bare announcement of God’s opposition to Mount Seir and his intention to destroy it. “Mount Seir” was not a single peak but rather the highland region southeast of the Dead Sea.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 35:5–9 The familiar because … therefore structure of indictment sets out the key charges against Edom (v. 5) and details the judgment (vv. 6–9). Edom is treated here much as Israel was in ch. 6.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 35:10–12a Edom’s land-grab is condemned. Two nations refers to Israel and Judah as separate kingdoms (see 37:15–28). Punishment is presented as poetic justice: just as Edom treated Israel and Judah, so it will be treated in turn. The assertion in 35:10 that the LORD was there moderates the claims of those who portray Yahweh as having abandoned the land of promise (see 11:23) for the land of the exiles. This land remains the Lord’s.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 35:12b–15 The theme of derisive speech picks up one of the main issues from ch. 25. As there, so here the speech is more than simply taunting a vanquished people. God is himself the object of insult, and this is unacceptable. The sole mention of the name Edom comes in 35:15 (cf. note on vv. 1–15).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:1–15 The Mountains of Israel Restored. The judgment of Mount Seir (ch. 35)—so reminiscent of God’s prior judgment of the mountains of Israel (ch. 6)—contrasts with the announcement now of restoration in corresponding terms. The address here is fairly consistently to the “mountains of Israel” (36:1), and most of the second-person references (“you”) are plural. A singular reference is occasionally made, however (e.g., to the “land [soil] of Israel,” v. 6). Broadly, this oracle sets out an explanation for the wrath that befell the “mountains” (vv. 1–7), followed by the promise of their restoration (vv. 8–15). Within that simple division, the structure is complicated.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:1–7 In vv. 1–7 there are a series of nested “because” and “therefore” statements whose relationships are difficult to disentangle, as apparent outcomes simply introduce further grounds. Three factors are intertwined: the encroachment of Israel’s enemies, the desolation of the land, and the wrath of God. The enemies come to the fore in vv. 2 and 7, the situation of Israel is the focus of vv. 3–4 and 6, and God’s wrath is the theme of v. 5.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:2 The claim to the ancient heights points back to the intended dispossession of Israel’s land, judged in ch. 35.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:3 The enemy is seen to be legion: they came from all sides, without further identification (until v. 5). The derision (v. 4) inspired by the fall of Israel and Judah will be the closing concern of this oracle (vv. 13–15).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:5 That the judgment of Edom in ch. 35 was in part exemplary is seen here, as it takes its place within the welter of enemies that came against God’s people.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:8–15 But you signals a transition: although the address has been to the “mountains of Israel,” now the focus is on Israel’s promising future, rather than its bleak, enemy-ridden past. As in the “covenant of peace” (34:25–30), the prosperity of people is bound up with the bounty of the land. Verses 8–11 of ch. 36 present a series of blessings, reminiscent of the restoration of Job 42 as the new exceeds the old. The people themselves become the focus of Ezek. 36:12, reiterating right ownership (cf. v. 2).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:13–14 The identity of the “mountains” with the “land” is seen here: the you of v. 13 is plural, but the you addressed in v. 14 is feminine singular, referring to the land (soil) of Israel (v. 6). The long history of unsettled relationship between people and land will no longer hold in God’s restoration—a vision to sustain future hope.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:15 The reproach that went beyond insulting people to dishonoring God is also consigned to the past.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:16–38 Restoration for the Sake of God’s Name. This key passage sets out in concentrated form Ezekiel’s entire theology. It is one of the primary restoration passages, though it also contains an analysis of human failure that calls for divine judgment. It carries forward some ideas from the preceding “mountain” oracles, in particular the joint restoration of land and people, and the silencing of blasphemous taunts. Far overshadowing these, however, are the towering claims of the supremacy of a holy God. The impurity of God’s people impelled him to scatter them (vv. 16–21). This in turn led to derision (v. 20), so in order to vindicate his reputation, God was moved to act on behalf of his people (vv. 22–32). The restoration of the land of Israel silences the nations, compelling them to recognize the true God (vv. 33–36), just as the flourishing of Israel confirms their recognition of their own God (vv. 37–38).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:16–21 State of Impurity. With v. 15 ending on the note of reproach being lifted, this return to scrutinize Israel’s failings initially jars. However, this account of Israel’s impurity is the basis on which God’s intervention to restore his people must be understood. The metaphor of menstrual impurity (v. 17; see Lev. 15:19–30) is likewise jarring, but Ezekiel uses it for at least two reasons: (1) it accords with his earlier portrayals of the abandoned child (Ezekiel 16) and the sisters (ch. 23), and (2) it emphasizes Israel’s defiling the sacred. That is, the activity used as a metaphor for Israel’s sin is not a criminal or moral failure so much as a willful disregard of the holiness of God. However, the judgment itself (36:18–19) resulted in God’s holiness being yet further profaned (v. 20). So God looked now to his own interests (v. 21).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:22–32 Divine Intervention: A New Spirit. This theologically central passage is often compared to Jeremiah’s “new covenant” text (Jer. 31:31–34; cf. 32:36–41). The overtones carried by Jeremiah’s language resonate with political loyalty. Ezekiel’s overtones, by contrast, have to do with ritual purity, as Ezek. 36:17–19 bears out. The structure of this passage reinforces its message. The outer verses relate the responses of God (vv. 22–23) and people (vv. 31–32). Nested within the next layer are the movements of return and purification brought about in renewal (vv. 24–25, 28–30). At the heart of the passage is the divine gift of the new heart and spirit, which enables right response (vv. 26–27). The physical return was only the beginning of the fulfillment for these prophecies.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:22–23 It is not for your sake. The fundamental reason given for God’s acting on Israel’s behalf is not grace and mercy (though it is gracious and merciful) but to uphold the sanctity and greatness of God’s reputation: but for the sake of my holy name. Although the “recognition formula” (will know that I am the LORD, v. 23; cf. Introduction: Style) is used repeatedly throughout the book of Ezekiel, here its significance is made plain. It is not just that Israel’s God is “great” and “holy”; it is also imperative that God be given the recognition and respect, indeed the honor, that he is due. To vindicate the holiness of God’s great name is also to “hallow his great name” (cf. Matt. 6:9) and is contrasted to “profaning his name” (i.e., treating it, and so him, as not holy).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:24–25 The restoration of God’s reputation first requires the external renovation of his people. God’s actions are naturally sequential: gathering and return (v. 24) precede cleansing (v. 25). Purification with clean water echoes God’s earlier cleansing of his people (16:4, 9) and once again relates to ritual cleansing in the Mosaic law (cf., e.g., Lev. 17:15–16; 22:6; Num. 19:19–21). The reference to cleansing by sprinkling “clean water on you” recalls the cleansing by sprinkling for touching a dead body (Num. 19:13, 20), perhaps suggesting that the idols of Ezek. 36:25 are comparable to dead things. Many interpreters see this picture of cleansing by water as the background to Jesus’ words in John 3:5, “Unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God”; cf. the mention of “my Spirit” in Ezek. 36:27. Thus, Ezekiel’s prophecy refers both to outward cleansing by a ceremony and to inward, spiritual cleansing.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:26–27 God’s initiative moves from external to internal with the gift of a new heart and new spirit (see 11:19; cf. 18:31). The outer purification will be no use without the inner disposition to live rightly before God (36:27). The connection of “water” (v. 25) and “Spirit” (v. 27) lies behind John 3:5. I will put my Spirit within you predicts an effective inward work of God in the “new covenant.”

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:28–30 With God’s people now graced with an inclination to keep faith with God, so too there will be an enduring habitation of the land (v. 28)—this time with no occasion for it to prove “treacherous” (cf. vv. 13–14). The conjunction of restoration of people and land is a continuing theme through this part of Ezekiel (see e.g., 34:25–31). The restoration of the people to the land is symbolic of, and probably implies the reality of, the return of the people to live in the presence of God, knowing once again his blessings on their lives (see 36:27).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:31–32 you will loathe yourselves. The response of the renewed people is to see themselves as God sees them. not for your sake. The assertion of God acting for his own sake repeats and confirms the basis of God’s action spelled out already in v. 22, thus bracketing this overtly theological account of renewal.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:33–36 Land Renewed. As seen in vv. 28–30, the land enjoys the benefits of the people’s cleansing (v. 33). The impact on the land is not simply on its fertility (vv. 34–35). The cityscape is renewed as well as the landscape (v. 33). The mention of Eden (v. 35) emphasizes the nature of this act as re-creation (see 28:13; cf. 37:1–14). One appointed function of Israel’s experience in the land was to show the whole world a restored Edenic life, lived in God’s presence and with his blessing.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 36:37–38 Populace Increased. The flourishing of the people in terms of a flock recalls the pastoral imagery of ch. 34 (see also 37:24). Applying the metaphor to a flock for sacrifices (36:38) may seem ironic, but the imagery suggests not impending death but festivals and great numbers, all set aside for God. Then they will know. The recognition formula (cf. Introduction: Style) is a fitting conclusion to a passage in which recognizing the true God is seen to be paramount.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:1–14 The Vision of Dry Bones. This vision, Ezekiel’s third in the book (see 1:1), is one of the most famous passages in Ezekiel. While it stands on its own as a powerful statement of God’s power to re-create the community, the context is significant. The promised gift of new heart and spirit (36:26–27) left questions hanging (i.e., how can this be? and can it be true for us?). Chapter 37 addresses these questions. The vision itself is reported in vv. 1–10 with vivid power. The landscape is filled with bleached bones to which Ezekiel is commanded to prophesy. As he does, the bones are restored to life. The vision receives a double interpretation in vv. 11–14. The primary meaning relates directly to the exiles’ despair (v. 11) and concludes the vision in v. 14. Verses 12–13 transpose the metaphor to a graveyard and contain one of the few hints of resurrection in the OT (see note).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:1 The vast landscape of dry bones suggests the aftermath of battle, the ultimate outcome of the judgment of ch. 6.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:3 The question can these bones live? anticipates the exiles’ own self-perception (v. 11): total hopelessness. It also introduces one of the key words in the passage: the verb “to live” appears in vv. 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, and 14. Ezekiel’s response leaves the outcome to God’s sovereignty.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:4–6 God commands Ezekiel to do what seems pointless (prophesy over these bones, v. 4), and includes the promise that he will perform the impossible (vv. 5–6)—bring them back to life. The key to “resuscitation” is stated in v. 5: breath is the Hb. ruakh, the same word used for “the Spirit” in v. 1, and which appears seven more times in the vision.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:8 The first phase of prophesying results in the rebuilt bodies, which lack breath. So far this activity only yields corpses—but it is still a necessary first step.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:9–10 The second phase of prophesying is addressed to the breath (or wind or spirit/Spirit; Hb. ruakh, which can take all three meanings). The coming of the wind/breath/spirit that gives life powerfully alludes to God’s creative work in Gen. 2:7. God creates, and God re-creates.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:12–13 I will open your graves and raise you from your graves, O my people. The vision of national revival is transposed into the metaphor of a cemetery, which seems to be related to the experience of exile (v. 12b). By using this language, Ezekiel also contributes to OT teaching on resurrection. Although clear statements of bodily life after death are not common in the OT, one of the clearest comes in Daniel (Dan. 12:2–3). In addition, there were hints in earlier texts that prepared the way. The influence of a number of these texts, including Isa. 26:19 and Hos. 6:1–2 and 13:14, is immediately apparent in the NT. Other passages include Job 19:25–27 and Ps. 17:15 (see note).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:14 The fundamental lesson of the vision is repeated: when the Spirit is present, God’s people are enabled to live. This is the only basis on which hope can be held out to the despairing community.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:15–28 The Houses of Israel and Judah. The re-creative activity of vv. 1–14 included homecoming (vv. 12, 14). Although homecoming remains a minor element in the “dry bones” vision, it provides a link to this oracle (vv. 21, 25–26)—a symbolic action as in chs. 4–5 but much simpler than those Ezekiel performed earlier in his ministry. The instructions for this bit of street theater are given in 37:16–17. The reunion of Israel and Judah is another theme that Ezekiel shared with Jeremiah (cf. Jer. 30:3; 50:4; esp. 33:14–16, which joins the same themes as this passage). This action prompts questions from the onlookers (Ezek. 37:18) and sets up two oracles: vv. 19–20 announce the reunification of old northern and southern kingdoms; vv. 21–23 give the renewed nation its moral and political shape. Verses 24–28 elucidate the second oracle. The closing verses, with their allusions to the temple, provide a bridge to chs. 40–48.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:16 Joseph, as father of Ephraim (see Gen. 48:5, 8–20), here represents the northern kingdom of Israel. Judah represents the southern kingdom (cf. Ps. 78:67–68).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:19 make them one stick. Although the hopes for a reunion were alive at this time, Israel’s deportation by the Assyrians was already 150 years in the past. It may be that the “dry bones” vision in vv. 1–14 allayed doubts as to the plausibility of this hope.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:21–22 This renewed national unity requires a secure national home (v. 21). The reunion takes concrete political shape under the rule of one king, which is not Ezekiel’s usual title for the messianic figure (cf. “prince,” v. 25).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:23 The life of this nation is consistently moral and pure. The people are enabled to live in this way by God (I will save them). The covenant formula appears here and in v. 27, one mirroring the other.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:24–25 The assignment of David as shepherd-king recalls 34:23–24, there in terms of prince (v. 25), as well as several passages in Jeremiah (e.g., Jer. 23:5; 30:9). Divine enabling to live rightly (Ezek. 37:23) does not exclude moral vigilance on the part of the people but enforces it.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:26 The covenant of peace (see 34:25) and everlasting covenant (see 16:60) appeared individually earlier in Ezekiel. Here they come together to provide the charter for the renewed nation. The joining of these covenants also combines political life and the natural world, as if people and land are in symbiotic unity.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 37:27–28 My dwelling place shall be with them. The oracle’s conclusion emphasizes the centrality of God’s presence to the renewed people, the greatest of all blessings by far. The “dwelling place” (Hb. mishkan) recalls the wilderness tabernacle. The sanctuary (Hb. miqdash; see v. 26) points rather to the temple, in particular the renewed temple, which will occupy Ezekiel’s attention in ch. 44.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:1–39:29 Gog of Magog. These initially obscure chapters, which form a single unit, deliver a powerful assertion of God’s sovereignty. The prophet addresses the mysterious Gog, ruler of the equally mysterious Magog (see note on 38:2). Gog commands his own army and a legion of allies (38:4–6). Ezekiel’s oracle pronounces judgment on him for attacking renewed Israel (38:1–3, 7–13). However, there is a power greater than Gog: the sovereign God of Israel reigns over Gog’s plans, which will be used to vindicate God’s holiness (38:14–16). Gog and his hordes attack, bringing peril to God’s people and convulsions to the natural world. But they meet the wrath of God, who vindicates himself before the nations (38:17–23). God’s judgment against this latter-day enemy results in Gog’s complete destruction. His army falls (39:1–6), an event that galvanizes God’s people as they see the greatness of their God (39:7–8). So great is the number of the dead, and so complete the victory, that Israel will use the weapons taken from Gog as fuel for seven years (39:9–10) and take seven months to cleanse the land of the dead (39:11–16). This “sacrifice” will yield a feast for predators (39:17–20). No question will remain about the reason for Israel’s earlier exile: the all-powerful God withdrew from them because of their treachery, but this final victory displays God’s supremacy (39:21–24) and marks the final restoration of his people (39:25–29). Sketched thus, the contours of Ezekiel’s prophecy against Gog are clear, but obscurity remains at the level of detail. The structural signals that usually mark Ezekiel’s oracles are of less help here, as the introductions and conclusions often do not coincide. Another problem for interpretation is the shifting viewpoint taken at different points in the oracle (somewhat like the parable of ch. 17). As the vantage point shifts from prophet to observer to an overtly theological outlook, so too the reader’s perception of the narrative alters. The setting of this oracle in the context of restored Israel remains clear, and theological lessons emerge. The security Israel enjoys is not the result of a lack of threats but of an indissoluble bond between God and people. Nor is the presence of threat a sign of God’s absence: the human, animal, and natural worlds are all under God’s control.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:2 Gog, of the land of Magog. These two names have been the focus of extensive investigation and speculation in both Jewish and Christian literature, but there is no consensus on their meaning. Some interpreters think “Gog” is a veiled reference to a historical figure, such as Gyges, a seventh-century B.C. king of Lydia in Asia Minor, in which case the prophecy would be about a future attacker similar to Gyges. Others have thought it was a prediction of Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.). But elsewhere Ezekiel was willing to make firm identifications or use more obvious symbols, and a connection with Alexander would be anything but obvious. Therefore many interpreters understand this passage to be a prophecy concerning an attack against Israel in a more distant future. In rabbinic literature and the Targums, Gog and Magog are often seen as leaders of a great attack on Israel in a future messianic age. In particular, Magog is seen as representing the Scythian people (see Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 1.123), who ruled vast regions of Asia north of the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea (modern Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan) and who also conquered peoples east and south of the Black Sea (modern Georgia, Armenia, and Turkey). In the NT, Gog and Magog are the names of the nations led by Satan to attack Jerusalem at the end of the “thousand years” (Rev. 20:8). Although the other geographical names in this passage can be identified (see notes on Ezek. 38:5; 38:6), “Gog” and “Magog” remain enigmatic, perhaps because the intention of the prophecy is simply to point to a yet-unknown future leader of a great attack against God’s people, one whose identity will not be known until the prophecy is fulfilled. No time is specified in the prophecy either, except the vague “In the latter years” in v. 8 and “In the latter days” in v. 16. (As the esv footnote indicates, an alternative translation of v. 2 is “Gog, prince of Rosh, Meshech, and Tubal,” but no place named “Rosh” can be clearly identified either.) Meshech and Tubal, first named in Gen. 10:2, are in Asia Minor (see note on Ezek. 27:13).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:4 I will bring you out. From the beginning, God’s initiative in rousing Gog’s hordes is apparent.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:5 For Persia (modern Iran), cf. 27:10; Cush is in the region of Ethiopia (cf. 29:10); Put is identified with Libya (27:10; 30:4–5). Gog’s allies are described in terms analogous to those of Tyre in 27:10. Together with 38:2, 6, this passage depicts enemies coming against Israel from all sides: Meshech, Tubal, Gomer, and Beth-togarmah from the north (vv. 2, 6), and here Persia, Cush, and Put from the south.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:6 Gomer probably refers to the Cimmerians, who had lived north of the Black Sea (modern Ukraine and the southern part of Russia) but were expelled by the conquering Scythians and migrated to an area south of the Black Sea, in Anatolia (modern Turkey). For Beth-togarmah, see note on 27:14. The uttermost parts of the north seems to refer to enemies that will come from regions to the far north of Israel, without specifically identifying these enemies. This phrase (repeated in 38:15; 39:2) has led some interpreters to understand this as a prediction of a future attack against Israel by Russia (Russia is the country farthest north of Israel, and Moscow is directly north of Jerusalem). But others see it as a general prediction of invaders from the north (see note on 38:2). In other places in the OT, this phrase describes the place where God reigns (Ps. 48:2) or where God will set his throne (Isa. 14:13), which would suggest a more symbolic interpretation of this oracle.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:8 Locating this episode in the latter years in the land that is restored casts this oracle into the future. See the “latter days” in v. 16 (cf. note on Isa. 2:2); thus, it is not necessarily the absolute end of time.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:10–13 The clear insistence that Gog remains firmly under God’s control and, in fact, acts at God’s behest (vv. 4, 16), does not preclude Gog from forming plans to plunder the now-fertile land of restored Israel (the quiet people who dwell securely, v. 11) and being held responsible for those plans.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:16 like a cloud. The vastness of Gog’s hordes that come against Israel is a theme repeated throughout these chapters. Once again, God’s sovereignty over Gog’s actions is asserted (I will bring you), as Gog is a tool used to vindicate God’s holiness. In this, Gog evokes Pharaoh in the exodus narratives (see Ex. 7:3–5; 14:4).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:17 The Septuagint understands this sentence as an assertion rather than a question (though the Hb. is more naturally a question). Either way, it probably relates to the mysterious “foe from the north” tradition linked especially to Jeremiah (e.g., Jer. 4:6; 6:22).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:19–20 Upheaval in nature, reflecting the cosmic outpouring of God’s wrath, consequently affects God’s own people. Such phenomena are also part of Jeremiah’s vision of the future (cf. Jer. 4:23–26).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 38:22–23 This battle is God’s. So too the greatness belongs to him alone.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 39:1–6 God’s opposition to Gog is reiterated as the invasion of Israel proceeds, only for Gog’s army to fall solely by the hand of God. On Meshech and Tubal, see note on 38:2. uttermost parts. See note on 38:6.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 39:7–8 This brief passage asserting the devotion to the holy God by his own people is introduced at this point as the obvious peril implied in vv. 2–5 draws attention to the Israelites themselves. It also forges a link with 21:7, where the words of 39:8 were applied to Judah and Jerusalem. The fall of Gog’s hordes is as certain as Jerusalem’s own was.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 39:9 The seven years of fuel provided by the abandoned weapons of the enemy corresponds to the “seven months” of burial in v. 14. The number seven is also deliberately employed in the collection of oracles against foreign nations.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 39:17–20 This grisly scene represents the wholesale inversion of what sacrifice intends, but God has inverted it. The slain of Gog’s army are carrion for scavengers, a banquet celebrating condemnation. In John’s vision of the end in Rev. 19:17–21, he sees an angel using this language and this imagery.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 39:21–24 all the nations shall see my judgment. This absolute, unanswerable demonstration of God’s power serves as vindication before the nations. It also puts Israel’s exile into proper perspective. Their expulsion from their land was not because their God was incapable of preserving them. On the contrary, their treachery compelled God to hide his face (vv. 23, 24; cf. v. 29) from them, leaving them to the fate they deserved for their iniquity of turning against God (cf. Deut. 31:18).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 39:25–29 The final element of the oracle attends now to Israel rather than to Gog. These brief verses echo many of the restoration passages in chs. 34–37, including the themes of renewal for the whole house of Israel (39:25), the turning away from previous treachery (v. 26), and the gathering and return of those once scattered (vv. 27–28).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 39:29 God’s promise (I will not hide my face) ensures that the abandonment reviewed in vv. 23–24 is consigned to the past (cf. Isa. 54:8). As in Ezek. 37:1–14, this final renewal coincides with the outpouring of my Spirit.