Study Notes for Ezekiel

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:1–3:27 Inaugural Vision. The opening sequence of Ezekiel is the most elaborate and complex of the prophetic call narratives in the OT, and also one of the most carefully structured. In a vision, Ezekiel witnesses the awesome approach of the glory of God (1:1–28). Ezekiel receives his prophetic commission through swallowing the scroll God offers (2:1–3:11), thus both fortifying him and training him in obedience. After the glory of God withdraws (3:12–15), Ezekiel’s role is further refined by his appointment as a “watchman” (3:16–21). The sequence concludes with a further encounter with God’s glory (3:22–27).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:1–3 Setting. Unusually, Ezekiel opens with an autobiographical note (v. 1) and some accompanying explanation (vv. 2–3). These verses have echoes in 3:14–15; together they frame the book’s opening vision.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:1 What the thirtieth year signifies is obscure, as it does not follow the usual pattern for dates in Ezekiel. It may refer to the prophet’s age. Reference to the Chebar canal locates the prophet near ancient Nippur (or, in modern terms, halfway between Baghdad and Basra) and thus not in the city of Babylon itself. Visions of God links this vision with 8:3 and 40:2; the other great vision in the book (37:1–14) does not use this language.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:2 Probably the “thirtieth year” of v. 1 should be linked with the fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin (i.e., 593 B.C.). Jehoiachin’s exile is the regular chronological marker for dates given throughout the book. Jehoiachin was only 18 at the time of exile in 597 B.C., and had then been king for only three months (see 2 Kings 24:8).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:4–3:15 Inaugural Vision. The vision forms a unified whole, in spite of its being comprised of distinct episodes. It is symmetrically structured, having onion-like layers: the “frame” (1:1–3 and 3:14–15) is wrapped around the approach and departure of the cherub-throne (1:4–28 and 3:12–13), with the prophet’s audience before the Lord contained in 2:1–3:11. That central section has its own internal “nesting.”

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:4–28 The Throne of the Lord Approaches. The richness of detail in Ezekiel’s account of this vision is both inspiring and perplexing. It recalls the traditions of the ark of the covenant (Ex. 25:10–22), especially within the context of Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 8:6–8), and stands at the head of the later mystical merkavah (Hb. for “chariot”) tradition within Judaism.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:4 A stormy wind (Hb. ruakh se‘arah) heralds the approach of the Lord, as in Job 38:1; 40:6. Likewise, the north is associated with the divine abode (see Ps. 48:2), and in Jeremiah it indicates the source of divine judgment (Jer. 1:13–15). The phrase as it were translates the Hebrew preposition ke-, “like,” which is used 18 times in this description; half of those are in Ezek. 1:24–28. Clearly Ezekiel is groping for language to describe the vision.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:5–14 The piling up of detail contrasts with the bland label of living creatures, only later identified as “cherubim” in 10:20. The first impression (1:6–9) is followed by closer detail (vv. 10–13). (A beautiful carved ivory that may depict one of these composite creatures has been found, dating to the 9th century B.C. It probably comes from the site of Arslan Tash in northern Syria. The figure combines all four features described in ch. 1: a human figure, wings of an eagle, forelegs of a lion, and hind legs of an ox.)

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:5 The many uses of the term likeness (Hb. demut, 10 times in ch. 1) emphasize the impressionistic nature of the vision’s description.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:9 The notice that their wings touched is reminiscent of the description of the cherubim in the Most Holy Place in Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 6:27). The four-sided form of the creatures ensures that they can always do the impossible: go straight forward, in any direction, but without turning (cf. “went straight forward” [Ezek. 1:12] with “darted to and fro” [v. 14]).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:10 The creatures had a predominantly human shape, but each had four different faces. This assemblage is unique, although complex combinations of supernatural beings are known throughout the ancient Near East. Many suggestions have been made to explain their symbolism. Certainly each creature is majestic in its realm, whether among the wild (lion; Prov. 30:30) and domestic (ox; Prov. 14:4) animals, or in the air (eagle; Prov. 23:5; cf. Obad. 4), with each of them noticed subsequently to the human face (cf. Gen. 1:26). This imagery is later echoed in the four (separate) creatures before the throne in Rev. 4:7.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:11 The two wings of these creatures (also in v. 23) are similar to the three pairs of wings of the seraphim in Isaiah’s throne vision (Isa. 6:2).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:12 straight forward … without turning. See note on v. 9. Should this spirit (Hb. ruakh) be identified with that of v. 20? It is certainly different from the ruakh (Hb. for “wind”) of v. 4. Given the closer identification of the spirit in v. 20, it seems likely that here the reference is to a “spirit” beyond the living creatures—in other words, the creatures’ movements are responsive to the divine spirit (for “Spirit,” see note on 3:12; and esv footnote on 1:12).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:14 darted to and fro. See note on v. 9.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:15–21 The complex structure of their wheels is difficult to envisage, though something gyroscopic seems to be suggested.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:16 Beryl (Hb. tarshish) is a crystalline mineral found in different colors. Here, it is likely to be the pale green to gold variety. The Septuagint does not use a consistent Greek equivalent.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:18 The wheels’ eyes should be understood metaphorically and as related to the “gleaming” beryl of v. 16 (perhaps protruding gemstones).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:22–28 The climax of the vision: a form can be discerned above the wheels, above the creatures, above the expanse, on a throne. Wrapped in light, the glory of the LORD cannot be captured in human language.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:22–23 Expanse appears four times in the immediate context (vv. 22–23, 25–26) and forms a strong link to Gen. 1:6–8, 14–20, where it is used nine times (out of a total of 17 times in the whole OT). There the expanse forms the dome of the sky; here it is borne on the wings of the creatures and forms a boundary beyond which comes the culmination of the vision.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:24 For the first time in the vision, sound dominates sight, even though the preceding description includes a violent thunderstorm (v. 4). The sound of many waters will again accompany the approaching glory of God in 43:2.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:25 While the sound of a voice is registered, report of speech is deferred until v. 28b.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 1:28 The bow … on the day of rain could signal the covenant rainbow of Gen. 9:13–16. Given the ominous message that follows, the more likely symbolic reference is to the bow that is the Lord’s weapon from the storm, which shoots arrows of lightning (see Ps. 7:12–13; Hab. 3:9). The glory of the LORD is his manifested presence with his people, visible in the wilderness (Ex. 16:7) and then accessible through the sanctuary (Ex. 40:34–35); in Ezekiel the term appears in Ezek. 1:28; 3:12, 23; 8:4; 9:3; 10:4, 18–19; 11:22–23; 43:2–5; 44:4. This glory will leave the temple (chs. 9–11) and then will return to the restored temple (43:2–5). See note on Isa. 6:3. I fell on my face. In the NT, John’s vision of the risen Christ (Rev. 1:9–20, esp. v. 17) stirred a similar response.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 2:1–3:11 The Prophet Commissioned. The vision of glory culminates in a call that is both sweet and severe. Two speeches bracket a test of obedience.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 2:1 Ezekiel is never addressed by name, but 93 times as son of man (Hb. ben-’adam), out of a total of 99 times for the phrase in the OT; Daniel is the only other person so addressed in the OT (Dan. 8:17). The Hebrew idiom “son of x” indicates membership in a class. “Son of man” identifies Ezekiel as a creature before the supreme creator. This highlights the humanity and thus the proper humility and dignity of the servant before Israel’s almighty, transcendent God.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 2:2–4 The characterization of the people of Israel as rebels sounds a distinctive note throughout the commissioning vision. This deep-seated trait (and their fathers; cf. v. 4) will be emphasized again in Ezekiel’s retrospective of Israel’s history in ch. 20. Ezekiel is sent to speak on God’s behalf (you shall say to them), but no content is given—yet.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 2:5–7 The label rebellious house, used almost like a refrain in these verses, is unique to Ezekiel (see also 3:9, 26–27; 12:2–3, 9, 25; 24:3). This label joins 2:2–4 in pointing to a deeply ingrained bent to rebellion, while treating the Judean nation as a whole. On the parallel of vv. 6b–7 to 3:9b–11, see note on 3:9b–11.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 2:8–3:3 The demand to eat the scroll immediately tests Ezekiel’s obedience, a matter of contrast with the rebelliousness of his compatriots. The progression from command to compliance moves through three moments of speech and response (2:8–10; 3:1–2; 3:3).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 2:8–10 The request to open your mouth and eat comes without any indication of what is to be given. The missing “content” of v. 4 is about to be provided, not as food but as the scroll of a book. This phrase (elsewhere found only in Ps. 40:8; Jer. 36:2, 4) emphasizes the scroll’s physicality. When it is unrolled, the writing is visible front and back: the scroll is full, just as Ezekiel soon will be (Ezek. 3:3). Its words are all audible, though their precise content remains unspecified.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:1–2 The command to eat is now combined with the commission to go and speak.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:3 feed your belly. Does this third instruction imply hesitation on the prophet’s part? Finally, having tasted, the prophet gets another surprise: the words of mourning are not bitter, as one would expect, but sweet as honey. Ezekiel has taken a first step in obedience to the Lord.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:4–11 Following Ezekiel’s obedient response, the emphasis shifts from prophet to people, though both remain in view.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:4 The command to go and speak is repeated in v. 11, framing this second speech. While the first speech emphasized divine sending (2:3–4), here the focus is on the prophet’s going.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:5–7 Contrary to expectation, Ezekiel is cautioned that a cross-cultural mission would be easier than taking words of God to his own people. There is nothing inherently derogatory about foreign speech and a hard language, although the terms could be negatively applied to a foreign oppressor (cf. Isa. 33:19).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:8–9a made your face as hard. This equipping forms the necessary step to the final charge.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:9b–11 The conclusion to the second speech echoes and expands on that of the first (2:6b–7). Despite the striking resemblance of the English texts, the Hebrew is cast quite differently in the two passages. This could simply be stylistic variation. If the Hebrew constructions are intended to carry a nuance, then 2:6b–7 has the force of an immediate instruction (“don’t be afraid [now]!”) while 3:9b–11 has that of a blanket prohibition (“never fear!”). It could also carry the implication that Ezekiel, now that he has been divinely toughened, simply will not be afraid.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:10 Embedded in this charge, God’s words give one of the few descriptions of prophetic experience in the OT, involving both a psychological (receive in your heart) and an auditory (hear with your ears) element (cf. Job 32:18–20; Jer. 20:7–9).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:12–13 The Throne of the Lord Withdraws. The departure of the glory of God is accompanied by the same sensory experiences as its approach (cf. 1:24).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:12 the Spirit lifted me up. Simultaneous events are being described: Ezekiel is being taken away, but at the same time the throne of the Lord is departing. There is ambiguity in the Hebrew ruakh: “Spirit” implies the divine spirit (see notes on 1:4 and 1:12) but, given the stormy setting, “wind” (esv footnote) or the Spirit manifested in the form of wind is also possible. However, there is a tacit “transportation” here (see 3:15), and the parallels in 8:3 and 37:1 point toward this certainly being the divine Spirit in action in some form.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:13 In the audience with God, the living creatures have been momentarily forgotten, but their movement brings them dramatically into focus once more.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:14–15 The Vision Concludes. In language echoing 1:1–3, Ezekiel’s visionary encounter with the Spirit draws to an end. It is tempting to think of going in bitterness in the heat of my spirit simply as a state of agitation following this traumatic encounter, and the translation “in the heat” leaves open this possibility. But this idiom appears 30 times in the OT, and the esv generally translates it “in wrath” or “in fury” or the like. Probably this nuance also applies here. Ezekiel has gained a divine perspective on his people’s sin, and his anger reflects that shared viewpoint.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:15 Although no “transportation” was narrated in the course of the vision that began by the Chebar canal (see note on 1:1), Ezekiel knows himself to have been elsewhere. The seven days of recovery echo the time of Job’s recovery from tragedy before he finds his voice (Job 2:13). The term Tel-abib means “mound of the flood,” but its precise location has not been determined. It was near the “Chebar canal,” and therefore it should not be confused with modern Tel Aviv in Israel.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:16–21 The Watchman. Ezekiel is assigned duty as an early warning system for Judah. This role is rehearsed and elaborated in 33:1–9, the passage introducing the second phase of Ezekiel’s ministry.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:17 The task of watchman is also found in Isaiah (Isa. 21:6–9), Hosea (Hos. 9:8), and Habakkuk (Hab. 2:1), but none provides a direct parallel to Ezekiel’s commission (see 2 Sam. 18:24–27; 2 Kings 9:17–20). The insistence on speaking only the divine word persists from Ezek. 3:10.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:18–19 Although the intent is clearly to warn the wicked and thus save his life (cf. 33:8), the more fundamental concern here remains the fidelity of the prophet to deliver warnings faithfully. Both scenarios result in the death of the wicked; but in the second, if the warning is issued, the prophet’s life is saved (delivered your soul; see 3:21).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:20–21 Even the righteous need warnings, for they remain susceptible to sin. Indeed, God’s sovereignty includes taking responsibility for the fatal stumbling block of v. 20.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:22–27 Inaugural Vision Reprise. This final piece of the complex vision sequence comes as something of an aftershock in the wake of the main event, with several direct parallels to the earlier vision.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:22–23 Here the valley is the broad river valley of Mesopotamia, the same setting as the later vision of dry bones (37:1).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 3:25–27 Ezekiel has already ingested the message (vv. 1–3) and absorbed the divine perspective (v. 14). His identification with the prophetic message is pushed even further, with his actions and words under direct divine control. Ezekiel will be mute until Jerusalem’s fall (see 33:22). Such constraint raises the problem: how will he warn if he cannot speak? The solution: oracles of God will be divinely enabled—I will open your mouth. The concluding words are familiar, echoing the terms of the divine commission in 2:4, 7.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:1–24:27 Judgment on Jerusalem and Judah. In the roughly chronological ordering of Ezekiel’s preaching, the oracles of chs. 4–24 precede the downfall of Jerusalem in 586 B.C. His message consistently points to approaching judgment; both the message and the messenger were vindicated by the fall of the city. Although the sequence appears to be chronological, there is also some grouping by theme and genre: chs. 4–7 include a high density of “symbolic actions”; chs. 8–11 comprise the second major vision sequence in the book, Ezekiel’s first “temple vision”; chs. 15–23 are dominated by “parables” and extended metaphors. Almost the only relief from the relentless indictment of sin and announcement of judgment comes in 11:14–21, which anticipates the hopeful tone of the latter half of the book, but not without sounding the familiar warning.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:1–5:17 God against Jerusalem. Commissioned, equipped, and positioned, Ezekiel now receives his first complex of oracles.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:1–5:4 God against Jerusalem Enacted. Poetry is typically the vehicle for prophetic oracles—but not here. Ezekiel is called upon to perform “street theater”: actions (rather than words) that convey a divine message. In most cases in Ezekiel, like this one, only the instructions are recorded, and not the report of the performance and its reception.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:1–8 This complex of instructions is not dated. Although the “vision reprise” in the preceding section links it most naturally back to the beginning of the book, other terms (e.g., “cords” in 3:25; cf. 4:8) join it closely with this passage. If so, these symbolic actions would then belong to the same time frame as the prophet’s commissioning (about 593 B.C.). In any case this passage ought to be dated before the events of 24:1 (roughly 587 B.C.), when the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem is reported to Ezekiel.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:1–2 These verses describe a complete siege in miniature; brick was the common building material in Babylon, not Jerusalem. The fivefold repetition of against it strikes an insistent note.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:3 The iron griddle (Hb. makhabath barzel) was part of the priestly equipment (see Lev. 2:5; 6:21; 7:9); domestic versions were probably not metal. The sign ensures that the siege, which could have been construed as God’s passive neglect, be understood as deliberate hostility.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:4–6 The instructions to lie on your left side and then again lie down … on your right side prescribe Ezekiel’s disposition during the enacted siege (v. 7). The practicalities of what would amount to over 14 months in this posture are not spelled out (e.g., readers are not told for how many hours each day Ezekiel would lie down this way), but the implied identification of the prophet with his people remains strong.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:4 Punishment (Hb. ‘awon, “punishment” or “iniquity,” given as an alternative in esv footnote; cf. vv. 5, 6, 17). The word may refer to either an offense or its penalty. Ezekiel’s enactment points to “punishment,” which is the most likely sense (see v. 12), although when combined with bear, ‘awon usually carries the nuance of “iniquity” (e.g., Lev. 10:17; Num. 18:1). The number of the days, stipulated in the following verses, corresponds to periods of exile. Both phrases strikingly parallel the pronouncement of the 40 years of wilderness wandering in Num. 14:33–34.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:7 As the prophet takes God’s role in the street drama, the arm bared (cf. Isa. 52:10) suggests the more common “outstretched arm” (e.g., Ex. 6:6; Deut. 4:34; Ezek. 20:33–34) with which the Lord acts on behalf of his people, but here it is wielded against Jerusalem. Ezekiel’s muteness (3:26) gives way to speech with the instruction to prophesy against the city.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:8 For cords, cf. 3:25.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:9–17 Again, the actions commanded—in this case rationing of food and water—ensure that Ezekiel’s symbolic identification with the besieged community is complete.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:9 The combination of wheat … emmer (as the esv footnote explains, emmer is a type of wheat; it is inferior to ordinary wheat) is not prohibited, but it is not appealing. Desperation for food during a siege will drive one to eat even this—and worse.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:10 The twenty shekels ration of bread amounts to just 8 ounces (0.23 kg). Since Ezekiel is acting out a symbolic message, it is not necessary to suppose that he ate or drank nothing else for 24 hours every day, but in any case his hardship was evident.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:11 The sixth part of a hin is roughly equivalent to 1.4 pints (0.6 liters).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:12–15 Ezekiel raises no objection until he is told to use human dung for fuel. Animal dung is a common fuel (v. 15; cf. 1 Kings 14:10), but Ezekiel, as a priest, regards food as holy (e.g., Lev. 21:6; 22:7–8) and excrement as defiling (Deut. 23:12–14).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:16 Underlying the phrase supply of bread is the distinctive Hebrew “staff of bread” (matteh-lekhem; see esv footnote), which probably refers to a method of storage. To break the staff (see 5:16; 14:13; also Lev. 26:26; Ps. 105:16) is synonymous with famine.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 4:17 The context here reinforces the nuance of punishment for the Hebrew ‘awon (see note on v. 4).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 5:1–4 razor. Although cleanliness from disease may underlie this action (Lev. 14:9), it is unlikely that that picture of purification is in mind here. Rather, the shaving of head and beard combines elements that are again both desecrating and shaming. Priests should not shave off their hair (Ezek. 44:20; see also Lev. 21:5), so this desecrates as the unclean food did in Ezekiel 4. Further, the shaming of the king of Assyria in Isa. 7:20 at God’s own hands echoes Ezekiel’s action here. Each of the three actions should be understood as proclaiming destruction, even for those who survive (scatter to the wind, Ezek. 5:2; bind them, v. 3). Even the remnant of vv. 3–4 faces a precarious and vulnerable future.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 5:5–17 God against Jerusalem Explained. Naturally, these symbolic actions carry enigmatic elements, not the least of which is the motivation behind them. This oracular commentary on Ezekiel’s street theater offers the rationale and alludes to each of the three phases of Jerusalem’s destruction previously acted out. Since this passage is intended to be commentary, it is also in large part self-explanatory.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 5:8–10 The hostility identified here with God’s setting himself against Jerusalem points back to the actions in 4:1–2. eat their sons. This gruesome prospect arises not only out of the realities of siege warfare (see Lam. 4:10) but also from the judgments for breaking the covenant (Deut. 28:49–57).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 5:11 Deuteronomy often steels the Israelites to inflict stern judgment—when issues of purity or loyalty are at stake—in terms of their “eye not pitying” (e.g., Deut. 13:8; 19:13). The same Hebrew is used here for God’s eye that will not spare (also six more times in Ezekiel).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 5:12 The groupings of thirds point back to the symbolic action of the hair in vv. 1–4, as does the reference to scattering (cf. v. 10). With pestilence, famine, and sword (also v. 17; 6:11–12; 7:15; 12:16; and 14:21), Ezekiel employs one of Jeremiah’s favorite groupings of three disasters (used 17 times), one of several examples of the younger prophet’s use of language borrowed from his older contemporary.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 5:16 The commentary now connects with the famine, alluding to the second symbolic action (4:9–17), including the distinctive break your supply of bread (see 4:16).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 6:1–7:27 Oracles against the “Land.” These two extended oracles share the feature of being addressed to “geography”: the “mountains” (6:2) and “land” (Hb. ’adamah; lit., “ground”; 7:2) of Israel, a feature also shared with 20:46; 21:2; 35:2; and 36:1, 6. Although in both cases the real audience is human (see 6:6), this form of address must have some significance beyond being simply symbolic. A deliberate connection of both “mountains” and “land” is found in ch. 36—one of the most theologically important chapters in the book, which forms a counterpart to chs. 6 and 7. Chapters 6 and 7 both describe coming punishment, but each addresses a different theme.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 6:1–14 Against the Mountains of Israel. The address to the “mountains of Israel” (v. 2)—a phrase unique to Ezekiel in the OT—does more than strike a nostalgic note, although it does that as well. The hills were inherently linked to illicit worship (see 1 Kings 14:23; 2 Chron. 21:11; Jer. 3:6), and this is Ezekiel’s focus. Variations of the “recognition formula” (“you shall know that I am the LORD,” Ezek. 6:7; cf. vv. 10, 13, and 14) structure the chapter.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 6:1–7 prophesy against them. Here the focus is on the death of idolaters.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 6:2 set your face. Another favorite phrase of Ezekiel, expressing determination, reflects God’s own orientation in Jer. 44:11 and that of the “servant” in Isa. 50:7. Luke used it of Jesus in Luke 9:51.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 6:3 The treaty curses of Leviticus 26 lurk in the background. This is especially clear in the threat to bring a sword upon you, used five more times in Ezekiel (5:17; 11:8; 14:17; 29:8; and 33:2) and once in Lev. 26:25, but only in three other places in the entire OT. The high places (Hb. bamot) were not just the crests of hills. They were constructed cultic installations that could, therefore, be destroyed.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 6:8–10 leave some of you alive. Complete annihilation is moderated with the promise of a remnant (cf. 5:3). The remorse of the survivors is matched by the striking description of the effect that idolatry had on God: I have been broken (6:9) uses the same term of God as was used in v. 6 (“idols broken”), and indicates God’s deep sorrow at the people’s sin.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 6:11–13 The prophet’s nonverbal actions here indicate the force with which the oracle is to be delivered. This catalog of illicit cultic locations occurs elsewhere in the OT and has its roots in Deut. 12:2.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 6:14 The place name Riblah, a correction of the Masoretic text’s “Diblah,” is based on some Hebrew evidence (the mistake of d for r was very easy in both paleo-Hebrew as well as later square script). The area being described stretches from the Negeb to northern Syria.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:1–27 Against the Land of Israel. The address to the “land [soil] of Israel” (v. 2) links this chapter to the previous one against the “mountains of Israel” (6:2). Two features of this chapter pull in different directions: the Hebrew is at points quite obscure and translation is difficult (see the “uncertain” readings in esv footnotes); yet the imagery is striking and the overall sense plain. Although laid out as prose, many see Ezekiel’s diction here inclining to poetry, as short staccato lines echo content. As in ch. 6, the “recognition formula” (7:4, 9, 27; cf. Introduction: Style) gives internal shape to the oracle, which falls into two main parts (vv. 1–9, 10–27). Together they form a “sermon” whose text is Amos 8. The resonance of language and overlap of themes and sequence between these chapters is impressive, and it seems likely that Ezekiel’s oracle develops Amos’s earlier prophecy.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:1–9 The end has come (v. 2). This first section itself further divides in two, with introductory and concluding formulas framing vv. 1–4 and 5–9, with strong parallels between them: cf. vv. 2 and 5–6; 3 and 8; 4 and 9. Is this a first and second “edition,” both of which were preserved? The “odd man out,” v. 7, finds its echo in the second section at v. 12. These verses are mostly framed in the first person, as God announces the imminent outpouring of his wrath.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:2 The address to the land (lit., “soil”) of Israel uses a phrase unique to Ezekiel (found 17 times in the book, always referring to the people Israel). Similar to 6:2, it is evocative language on the lips of an exile. The announcement of an end (also 7:3, 6) picks up the language of Amos 8:2.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:3 abominations (also vv. 4, 8, 9; plural of Hb. to‘ebah). These are offenses repugnant to God that defile and that demand elimination. This is very frequent language in Ezekiel (mentioned 41 times), and is rooted more in Deuteronomy (e.g., Deut. 18:12) than Leviticus.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:7 The time and day point forward to the second part of the chapter, and indicate a moment of reversal.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:10–27 Behold, the day! (v. 10). The “day of the LORD” is a prominent theme in the Hebrew prophets, with origins in Amos 5:18–20 (see notes on Isa. 13:5–6; Amos 5:18–20). Ezekiel’s development relates most closely to Amos 8:9–10. It was a time of great expectation but was turned to bitter anguish at the hands of God, who was wrongly assumed to be coming in blessing. Among the many motifs shared between Ezekiel 7 and Amos 8 are the “day” itself, violence and wealth, agricultural metaphors, foiled commerce, desecration of holy things, and withholding of divine direction. In contrast to the first-person oracle of Ezek. 7:1–9, the action of vv. 10–27 is mostly carried by third-person descriptions of the coming disaster.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:12–13 The transactions described here connect with the laws of Lev. 25:26–27. There is no opportunity to redeem property because death will come first.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:17 all knees turn to water. The Hebrew formulation suggests a loss of bladder control with the onset of panic (lxx, “all thighs will be defiled with moisture”).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:20 The beautiful ornament is an obscure reference, but imagery of the temple is probably in mind.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 7:26 Loss of divine direction from the prophet, priest, and elders forges another link to Jeremiah, where the oblivious Judeans assume that such guidance will always be forthcoming (Jer. 18:18).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:1–11:25 Ezekiel’s Temple Vision. This is the second of Ezekiel’s four dramatic visions, having overt connections with the opening vision (chs. 1–3). It also has strong links to the concluding vision (chs. 40–48), which offers a mirror image to this one. Ezekiel is shown a mounting series of vignettes of idolatrous worship in the temple (ch. 8), the citywide slaughter of idolaters (ch. 9), the destruction of Jerusalem by fire, and the gradual withdrawal of the presence of the Lord from the temple (ch. 10). The vision culminates in the contrast of judgment on wicked officials (11:1–13) with an oracle of hope (11:14–21) before God’s glory departs completely (11:22–25). As a whole, the vision emphasizes God’s rejection of this generation of Judeans and demonstrates the justice of God’s stance.

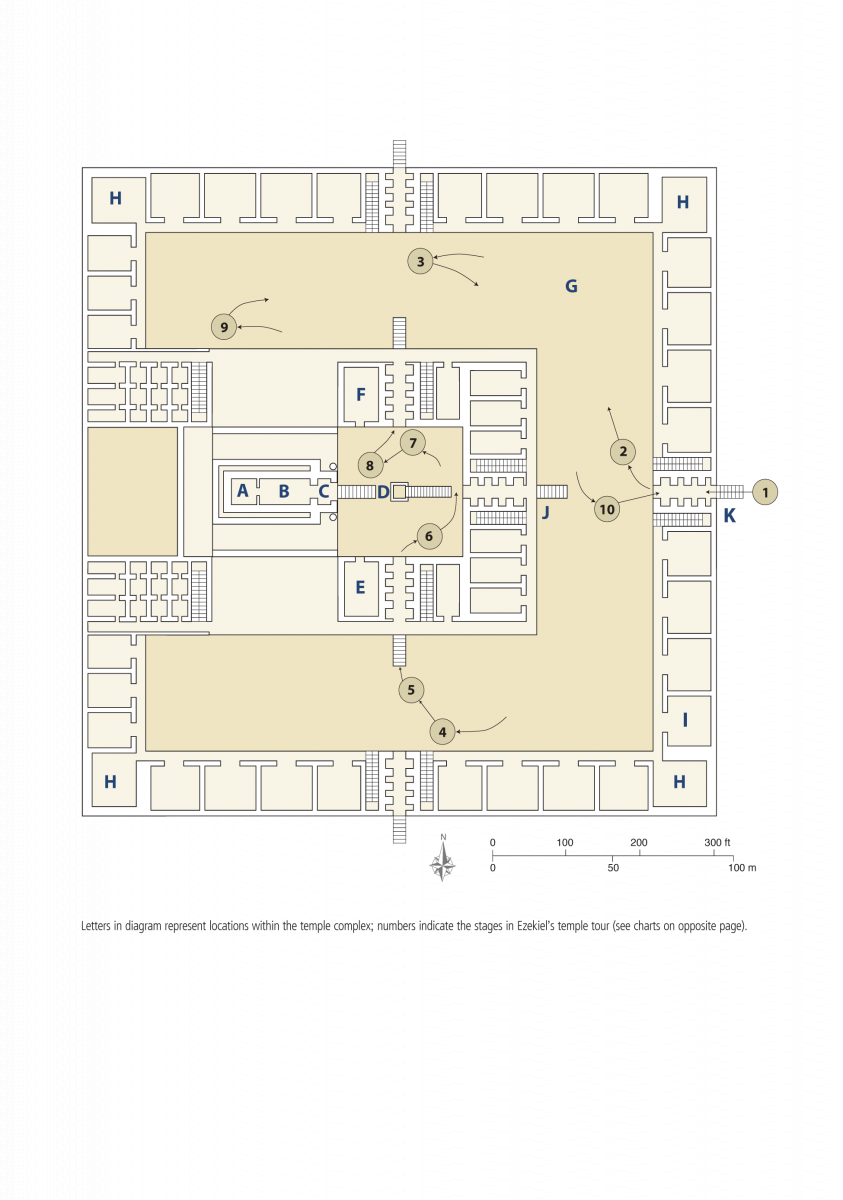

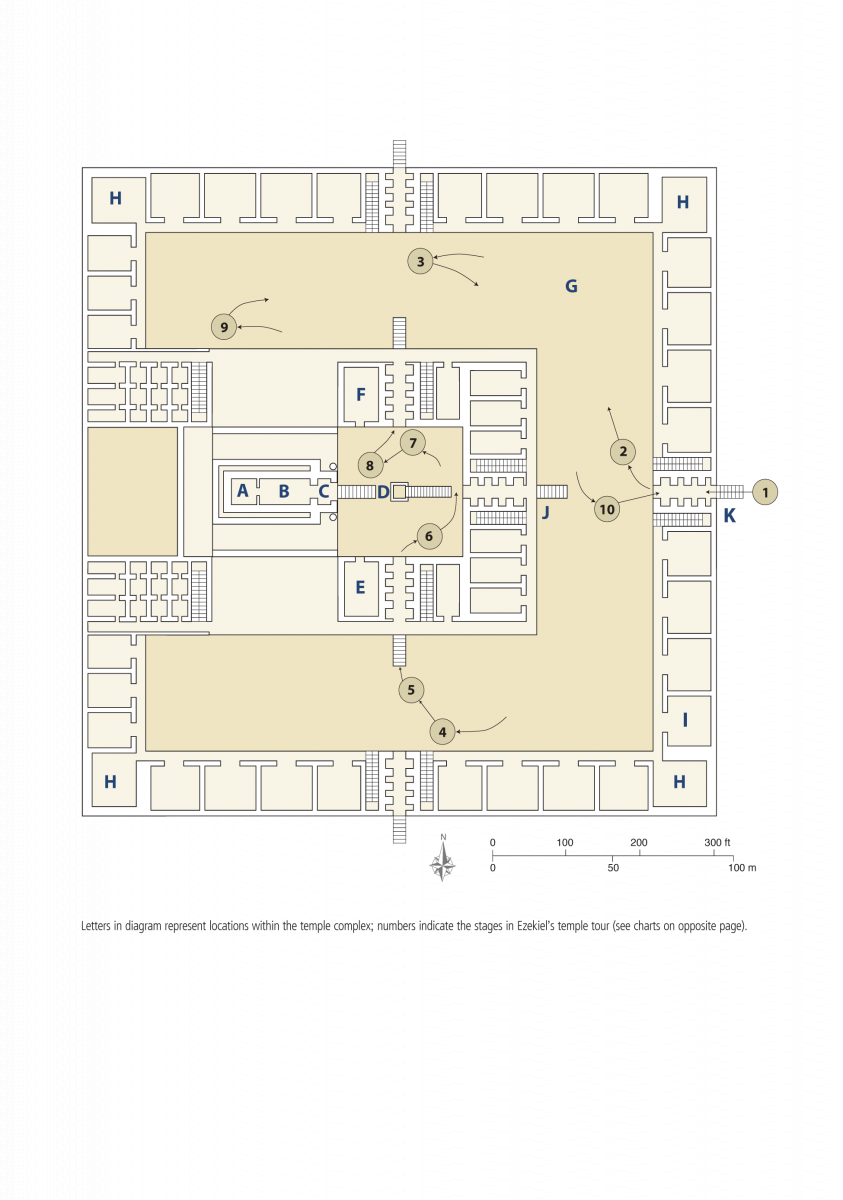

Ezekiel’s Temple Vision

Ezekiel’s final vision of an ideal temple (and city, and land; chs. 40–48) forms a counterpart to the vision of chs. 8–11. In each case he is taken on a tour of the structure, but whereas in the earlier vision he discovers abominations and perverted worship, in this final vision all is in readiness for the perpetual dwelling of the glory of the God of Israel. In chs. 8–10 most of the movement centers on the gate structures to the north and finally focuses on the main sacrificial altar, from which central point the slaughtering angels begin their work (9:6b). In this final vision Ezekiel’s tour begins and ends at the East Gate, but passes by the same areas as those he saw in the earlier vision. With the “tour” completed, he is again outside the main East Gate as he senses the approach of the glory of God returning the same way as Ezekiel had seen him go.

Temple Plan

The labels are arranged from the innermost, and most sacred, area and moving outward. It must be borne in mind that “temple” can have two quite distinct references: it can refer generally to the entire “temple” complex, including the outer gates and court; in its more “strict” reference the “temple” is the innermost structure itself, which has a single (eastern) entrance and contains the Most Holy Place.

| |

Reference |

Explanation |

| A |

41:4

|

The “Most Holy Place.” |

| B |

41:3

|

The inner room of the temple. |

| C |

41:2

|

The entrance to the temple. |

| D |

43:13–17

|

The imposing altar; although the number of stairs is not given, the entire altar structure is about 16 feet (4.9 m) tall, so many steps would have been required. This area of the inner court was accessible only by priests—not even the prince was permitted entry. |

| E |

40:46

|

Chamber for Zadokite priests. |

| F |

40:45

|

Chamber for “priests who have charge of the temple.” |

| G |

40:17–19

|

The outer court, with its 30 chambers in the outer wall (40:17). |

| H |

46:21–24

|

The temple “kitchens,” one in each corner of the outer court. |

| I |

40:17

|

The 30 outer chambers. |

| J |

46:2

|

The “prince’s gate”: from its threshold he worships on each Sabbath while the priests bring the offerings into the inner court. |

| K |

43:1

|

The main east gate, through which “the glory of the God of Israel” returns to his temple (cf. 10:19; 11:22–23). |

Temple Tour

| |

Reference |

Explanation |

| 1 |

40:6

|

The eastern (main) gate begins the tour; the E–W axis of the temple should be noted; if a line is drawn from the east gate to the Most Holy Place, there is a sequence of three elevations, as the space in the inner temple becomes increasingly constricted. |

| 2 |

40:17

|

From this vantage point in the outer court, Ezekiel is shown the main features of this “plaza” area. |

| 3 |

40:20

|

The northern-facing gate. |

| 4 |

40:24

|

En route to the southern-facing gate, no details are given of the outer facade of the inner court; the architectural details of this area must remain speculative. |

| 5 |

40:28

|

Ezekiel’s entry to the inner court is by way of its south gate … |

| 6 |

40:32

|

… then to the east gate (past the imposing altar, not yet described) … |

| 7 |

40:35

|

… and on to the north gate, which includes areas for handling sacrificial animals. |

| 8 |

40:48; 41:1

|

Ezekiel approaches the inner temple structure itself, first describing its entrance; he is then stationed outside the entrance while his guide first measures its interior, then the exterior. |

| 9 |

42:1

|

They exit the inner court through its north gate to explore the northwestern quadrant of the outer court. |

| 10 |

42:15

|

Ezekiel and his guide leave the temple from the east gate by which they first entered. From this vantage point, Ezekiel was able to watch the return of “the glory of the God of Israel” moments later (43:1–5). |

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:1–18 Transportation and Abominations. Ezekiel is transported in his vision to the temple complex at the heart of Jerusalem (vv. 1–4). In a series of locations, including both the center and the periphery of the temple, various cultic practices, termed abominations, are revealed.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:1–4 The vision begins with Ezekiel’s “physical” transportation from his home in Babylon (v. 1) to the Jerusalem temple (v. 3), a detail without parallel in the canonical OT (but cf. Bel and Dragon 14:33–36). Otherwise the setting is reminiscent of the inaugural vision (Ezekiel 1–3).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:1 The date formula places this vision in September 592 B.C., just over a year from the inaugural vision. No triggering event can be linked to this date with certainty, but the events leading up to the sinking of the anti-Babylonian scroll related in Jer. 51:59–64 may lurk in the background. Clearly there were “prophets” among the exiles fomenting rebellion (see Jer. 29:20–23). The elders (Ezek. 8:1) seek a word from Ezekiel.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:2 The manifestation of God that Ezekiel sees on this occasion is like that of the inaugural vision in 1:27. In 8:4 this connection is made explicit.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:3 When interpreting chs. 8–11 it must be borne in mind that what Ezekiel sees are dreamlike visions of God. This is spiritual, not “natural” reality. The inner gateway locates Ezekiel within the temple-palace complex, yet not at its center. (For the image of jealousy, see 8:5.)

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:4 glory. See note on 1:28.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:5–6 The first of the four vignettes situates Ezekiel with his back to the altar, facing an image of jealousy, which remains unidentified. The vagueness is deliberate: focus remains on the provocation of divine outrage, not on the specifics of the image itself. It will get worse (still greater abominations; cf. vv. 13, 15). These sins are “greater” in the sense of being more hateful to God; this can be because of such factors as bringing him more dishonor, bringing greater harm to others, expressing more and more defiance to God’s warnings or indifference to his love, being more boldly done in public, or being committed by those with greater responsibility.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:7–13 This second scenario demonstrates the impossible possibilities of visions. To look inside the wall for a literal “room” that could hold 70 men is to miss the force of what Ezekiel is being shown: the interior of self-deceived (v. 12) idolaters.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:10 The images engraved on the walls contravene not only the second commandment (Ex. 20:4) but also the list enumerated in Deut. 4:15–18.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:11 The presence of Jaazaniah the son of Shaphan among the 70 elders may have been a shock. He was probably a member of the clan of Shaphan (2 Kings 22:8–10) which had proved so loyal to the cause of Yahweh in Jeremiah’s ministry (e.g., Jer. 26:24). This identification is not certain, but would explain why Jaazaniah is singled out for mention here.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:14–15 Moving farther north, Ezekiel sees women weeping for Tammuz (from the Sumerian name, Dumuzi). This ancient Mesopotamian cult celebrated the shepherd-king and god of vegetation, whose association with sacred marriage seems clear, while claims about his status as a dying and rising god remain controversial. (The term “sacred marriage” describes ancient practices of ritual prostitution intended to ensure agricultural fertility.) Mourning rites among women in his cult are well attested outside of the Bible.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:16 The final vignette, also the briefest, states simply and starkly the climax of abominations. The twenty-five men are not further identified, but the location between the porch and the altar would normally be reserved for priests. At this sacred place they venerate the sun. Solar worship is prohibited in Deut. 4:19 (see also 2 Kings 23:11). The outrage of this action contrasts with what priests ought to do here (cf. Ps. 26:6–7; Joel 2:17).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 8:17–18 The behavior described in vv. 1–16 must be punished by a holy God. The phrase put the branch to their nose remains obscure; it was probably a gesture of derision.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 9:1–11 Slaughter in Jerusalem. A team of seven angels carries out the execution of the unfaithful in Jerusalem at God’s command. Only one of them is assigned the job of protecting the faithful. The prophet’s anguished intervention does not dissuade God from judgment. Cf. the Passover (Exodus 12): a mark protects the faithful from God’s agents of death.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 9:1–2 The first phrase of v. 1 ironically repeats the closing phrase of 8:18. Hebrew pequddot, here rendered executioners, also carries the sense of “governing officials.” The angels of the seven cities of Revelation 1–3 may be an analogy. In Ezekiel 9, destruction is by weapon; in ch. 10 it is by fire.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 9:3–7 Verse 3a is a parenthetic aside, foreshadowing the main focus of ch. 10. The seventh angel, in the role of scribe, puts a mark on the foreheads (9:4) of those faithful to the Lord. Preserving a remnant has been a feature of chs. 4–7. Here, the mark is the Hebrew taw, and in the script of Ezekiel’s day would be an X. Ancient Christian interpretation saw in this symbol an anticipation of the cross. Verses 6–7 of ch. 9 indicate that the slaughter is to begin where Ezekiel’s tour of ch. 8 ended. The command to defile the house (9:7) overcomes the reluctance to pollute the sanctuary with corpses (cf. 1 Kings 1:51; 2 Kings 11:15).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 9:6 they began with the elders. Just as the leaders had led the people astray, so now judgment begins with them, from their place before God’s house (the temple). This judgment is echoed in Peter’s talk of a purifying judgment that will “begin at the household of God” (1 Pet. 4:17).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 9:8–10 Ah, Lord GOD! Ezekiel’s impassioned outburst pleads for the remnant, and prompts the question: was the preserving angel finding any faithful? See also 4:14; 11:13; 21:5. God reiterates the firm intention of his justice and pointedly responds to the delusion of divine ignorance voiced by the elders (cf. 8:12 and 9:9).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 10:1–22 The Fire and the Glory. Two actions are interwoven here: the second (visionary) phase of city destruction (vv. 1–8), and the further withdrawal of the glory of God from the temple (vv. 9–22).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 10:1–8 The man clothed in linen (v. 2), a “preserving angel” in ch. 9, here becomes an incendiary agent of destruction. The narrative remains elusive, as attention oscillates between the angel (10:2, 6–7) and the cherubim, who are both the “throne” for God’s presence and the source of the burning coals that will ignite the city (vv. 1, 3–5, 8). On a natural level, sword and fire would coincide; in the vision, they are distinct phases.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 10:4 glory. See note on 1:28.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 10:9–22 Much of the description of the cherubim here overlaps with the account of the “living creatures” in ch. 1, and reference should be made to that passage for an explanation of the common features. Although the description itself already signals this equivalence, the visionary account makes it explicit in 10:15, 20–22. The assault of sight and sound on the senses seems overpowering, as it was in the inaugural vision. While description dominates this section, the action, confined to vv. 18–19, is crucial. At the threshold (v. 18) of the east gate (v. 19), the glory of the God of Israel is poised to depart from the midst of his sinful people slowly and in stages (perhaps symbolizing how he gives the people every opportunity to repent). The language is deliberate: “God of Israel” is used five times in this vision (8:4; 9:3; 10:19–20; 11:22), and four of those with “glory of.” Beyond these, this phrasing occurs in Ezekiel only at 43:2 and 44:2, when God’s glory returns.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 11:1–13 Punishment for Civic Authorities. The new introduction at v. 1 seems to interrupt the vision sequence at this point of tension, with God’s glory poised at the threshold. Ezekiel sees 25 men—a different group from 8:16, and at a different location. And unlike the previous group, the problem here is not with worship but with politics, although the precise issue at stake remains elusive. The overall impression is that the thing they fear will come upon them (11:8; like the Tower of Babel in Gen. 11:1–9) and that they have brought divine judgment on themselves. This framework helps make sense of the details.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 11:1 The named individuals are otherwise unknown; on Pelatiah, see v. 13. The Hebrew behind princes of the people (sare ha‘am) need not refer to royalty, nor does it here; cf. the identical phrase translated “leaders of the people” at Neh. 11:1.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 11:2–3 Unfortunately for interpretation, the wicked counsel announced in v. 2 and quoted in v. 3 is obscure. Verse 3a may be either a statement or a question. If the former, the cauldron and meat metaphor is negative (“we’re cooked!”); but if the latter, the metaphor is positive (“we won’t be burned!”). Since it is unlikely that being cooked is positive, the imagery is best understood to indicate fear, which led to mistrusting God. The metaphor is further developed in ch. 24.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 11:6 Although the judgment that multiplies corpses is divine (9:7), it has been provoked by the people’s guilt, and they remain responsible.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 11:7–12 The focus here is on the distinction between the court officials and the people slain. The outcome here has clarity that the earlier part of the vision lacked: the departure of Zedekiah’s court and its destruction at the hands of the Babylonians (see 2 Kings 25:4–7). Note the theological perspective of Ezek. 11:9 (I will bring you out), in contrast to the panicked flight of 2 Kings 25:4.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 11:13 The impact of the death of Pelatiah the son of Benaiah on Ezekiel is not immediately obvious. Perhaps it is due to Ezekiel’s shock at seeing such an immediate judgment from God in fulfillment of his prophecies. Its significance may also lie in the symbolism of the name itself: “The LORD delivers,” the son of “The LORD builds,” has died.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 11:14–21 Promise of a New Heart, Spirit. Ezekiel’s outcry of v. 13 apparently prompts one of the most important statements of hope in the book, one closely connected to the famous “new heart” passage in 36:22–32. In 11:15 the voice of those left in Judah is heard baiting the exiles. The divine response of v. 16 both asserts God’s own action in bringing about the exile (I removed … I scattered) and redefines the relationship between God and the remnant: the real sanctuary is not the temple but God himself. That new relationship is marked by a new spirit and a heart of flesh (v. 19) provided by God himself, which enables faithful living previously impossible with a heart of stone. There is a theological tension in Ezekiel between divine provision (here and 36:26–27) and human endeavor (“make yourselves a new heart and a new spirit,” 18:31).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 11:22–25 The Glory of the Lord Departs. The vision concludes on a tragic note: the departure of the God of Israel from his city denotes divine absence and thus death for the people. The mountain … on the east is the Mount of Olives. Both the action and location confirm that the emphasis falls on divine absence from Jerusalem rather than (by inference) presence with the exiles. God’s absence persists until 43:1–5. The concluding report (11:25) links back to the setting of 8:1.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:1–28 Anticipating Exile. The unfolding of events surrounding the collapse of Judah must always be borne in mind when reading Ezekiel. This is especially true for this chapter, as its predictions of exile come during a time when the exile has already begun. This only makes sense in the context of the uncertain decade between 597 B.C. (the deportation during the reign of Jehoiachin, during which Ezekiel was exiled) and 586 (the final fall of Jerusalem, during the reign of Zedekiah). It is the latter complex of events toward which these oracles point. Formulaic markers group them into two pairs: symbolic action is again a vehicle for the divine word in vv. 1–16 and 17–20; the passage of time prompted doubts about this further exile, and these are confronted in the pair of oracles in vv. 21–25 and 26–28.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:1–20 Exile Predicted. Ezekiel, who was included in the first deportation to Babylon, predicts a further exile by means of symbolic actions, much like chs. 4–5.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:1–16 Ironically, the issue of perception lies at the heart of this passage. Ezekiel’s fellow exiles form the audience whose attitude, one must conclude, remained untouched by their own experience of exile and whose expectations were therefore deluded.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:2 On Ezekiel’s distinctive use of rebellious house (also vv. 9, 25), see note on 2:5–7. The unseeing eyes and unhearing ears emphasize the willfulness of the exiles’ ignorance (cf. Isa. 6:9–10; Jer. 5:21).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:3 In their sight is repeated seven times in vv. 3–7, further underlining the main point of the prophecy. The hope that they will understand (lit., that they will “see”) also develops this theme.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:8–15 The explanation of the symbolic actions has both a broad and a narrow application. Verse 10 targets the prince in Jerusalem—a reference to Zedekiah, whom Ezekiel resolutely refuses to refer to as “king”—while the rest of v. 10 and the plural references of v. 11 broaden the scope to the rest of the remaining Judeans. Verses 12–15 point in specific detail to the fate of Zedekiah narrated in 2 Kings 25, much as did the oracle of Ezek. 11:5–12. Still, this remains a sign for you (plural, 12:11), that is, for Ezekiel’s fellow exiles.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:13 he shall not see it. The fate of Zedekiah is clearly in view here: cf. 2 Kings 25:7; Jer. 52:11.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:17–20 The demeanor of refugees is the focus of these verses. The symbolic action has some resonance with 4:9–17, but the emphasis here is psychological rather than ritual. The people of the land (12:19) refers to the commoners among Ezekiel’s fellow exiles who are now, of course, landless.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:21–28 Exile Confirmed. Apparently, the delay in fulfillment of the prophecy opened a window for counter-prophecies, which are here rebutted. This pair of oracles may be a longer and shorter version of the same prophecy given on different occasions, somewhat like 7:1–9. These verses provide an affirmation of the predictive element among the Hebrew prophets: their “forth-telling” is sometimes emphasized, but “foretelling” constituted a significant factor in their preaching.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:21–25 The proverb that authorizes ignoring Ezekiel’s warning, quoted in v. 22, is inverted in v. 23. It requires refutation, much as another proverb will in 18:2–3.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:24 The introduction of the theme of false prophecy sets the stage for the next block of oracles.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 12:26–28 Here, the tone is not so much the assumed failure of vision as its supposed interminable delay. But the God who gives the word will also bring it to pass, without fail.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 13:1–14:11 False Prophecy, True Prophecy. Chapters 13–14 express condemnation of speaking false prophecy and of ignoring true prophecy. The subject has already been broached in 12:24 in terms now repeated throughout ch. 13. The passage falls into two main sections: the condemnations against false speaking (ch. 13) and against false seeking (14:1–11).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 13:1–23 False Prophets. Two groups come in for condemnation: male “prophets” who simply prophesy delusions (vv. 1–16), and women who are prophets by pretense (vv. 17–23). Each group is addressed twice, so that the broad architecture of ch. 12 is also seen here (two groups of two oracles). The masculine and feminine references tend to break down toward the end of the chapter. Although the text is difficult, it remains clear that the issue is not gender. The themes developed here appear in concentrated form in Mic. 3:5–7.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 13:1–9 Introductory and concluding formulas as well as distinctive content bracket these verses from those that follow. The basic indictment—prophets speak their own delusions—is voiced in vv. 2–3 and developed throughout. The metaphors of vv. 4–5 are striking: like jackals (v. 4; cf. Jer. 9:11) they are no more than scavengers, when they ought to have been sentinels (Ezek. 13:5; cf. 22:30; Ps. 106:23). Hammering home the point, Ezek. 13:6, 7, and 9 each make explicit reference to false visions and lying divinations, the latter referring to the manipulation of some object to discern a divine message (v. 8 varies this pattern slightly). For this combination, cf. Jer. 14:14.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 13:2 who prophesy from their own hearts. Cf. v. 17. “Hearts” (Hb. leb) could also be translated “minds” as in Jer. 14:14; 23:16.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 13:9 The punishment is total exclusion. The council (Hb. sod) of my people provides an oblique contrast with the “council of the LORD” (Jer. 23:18, 22), where the prophet should stand.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 13:10–16 A further connection with Jeremiah (Jer. 6:14; 8:11) brackets this second oracle: the false declaration of peace (also Ezek. 13:16). The false prophets’ word of peace puts a delusive veneer on people’s hopes.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 13:17–21 Attention turns to women who give prophecies of their own devising. The term “prophetess,” usually found with genuine agents of God (e.g., Miriam in Ex. 15:20; Deborah in Judg. 4:4; Huldah in 2 Kings 22:14), is avoided with reference to these impostors. Focus shifts resolutely onto magical practices that are very difficult to clarify any further. The striking language of hunt for souls (Ezek. 13:18, 20) identifies this generally as illicit spiritual manipulation. Such behavior is forbidden (e.g., in Lev. 19:26, 31; Deut. 18:10–14).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 13:22–23 Those with spiritual power ought to strengthen the righteous and cast down the wicked; however, this has been inverted. The Hebrew of v. 22 is ambiguous in its reference, but the announcement of v. 23 (you shall no more) identifies the targets as the female false prophets of the preceding oracle. The conclusion (v. 23) forms a doublet with v. 21: God will deliver his people from this malicious power.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 14:1–11 False Inquirers. That the theme of false prophecy continues is clear from vv. 9–11, although now the problem is viewed from the side of the recipients rather than the producers of false oracles. A second occasion of being approached by the elders (v. 1) in exile (cf. 8:1; 20:1) sets the context for this oracle against idolaters seeking a word from the Lord. Although the exilic setting is not required to explain the idolatry of these elders, the new cultural setting and dislocation could promote unthinking syncretism. This section turns on God’s question in 14:3, which brings three successive responses. Verses 4–5 give an apparent “yes,” but what it might mean to lay hold of the hearts (v. 5) is unpacked in the following verses. The second response comes in vv. 6–8: any divine answer to idolatrous inquirers will be tuned to their repentance (v. 6)—which, if not forthcoming, leads to their rejection by God (v. 8). The third response (vv. 9–11) joins inquirer and false prophet, as God asserts responsibility for deceptions that ensure punishment for both partners in delusion (cf. 1 Kings 22:13–28).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 14:7 The strangers (Hb. ger) and native Israelites were to have one and the same code for life, according to priestly law (cf. Lev. 19:33–34; Num. 15:13–16).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 14:9 I, the LORD, have deceived that prophet. One of the forms of God’s judgment is allowing people to believe falsehood, or even (as in this verse) leading them to believe falsehood. Yet Scripture also consistently affirms the human decision to sin and human responsibility for that decision (note the idolatry [v. 7] that preceded this deception, and the just punishment from God [vv. 9–10]). Moreover, Scripture never says that God himself speaks falsehood (he cannot; Titus 1:2; Heb. 6:18), and it never excuses human beings for speaking or believing falsehood.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 14:10 On bear their punishment, see note on 4:4.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 14:12–15:8 The Consequences of Infidelity. Larger complexes of material are more difficult to discern, from this point through to the collection of oracles against foreign nations (chs. 25–32). The common thread in these verses is the certainty of divine judgment on Jerusalem.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 14:12–23 Noah, Daniel, Job. Five clearly formed paragraphs make up this oracle: the first four detail four modes of divine judgment on Jerusalem: famine (vv. 12–14); beasts (vv. 15–16); sword (vv. 17–18); and pestilence (vv. 19–20). The final paragraph provides a summary and holds open the possibility of a remnant (vv. 21–23). For this oracle’s holding up righteous heroes of the past, cf. Jer. 15:1. For its implied hope that a few righteous might suffice to save many wicked, cf. Gen. 18:22–33. The implicit assertion that each individual is held to account for his or her own life (the summary phrase of each paragraph here) was an implicit theme of Ezekiel from the start (see Ezek. 3:16–21) and will see its fullest treatment in ch. 18.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 14:14, 20 Noah and Job are well-known righteous men of the past (see Gen. 6:9; Job 1:1). Noah saved only his family; the protection of Job’s piety did not even extend that far. The identity of Daniel (cf. also Ezek. 28:3) has been disputed. Traditionally, he is identified with the hero of the book of Daniel, a contemporary of Ezekiel, who served in the court of Babylon and then of Persia. His reputation might have spread widely enough by this time for Ezekiel to expect his audience to recognize him (cf. Dan. 2:1, which is well before Ezekiel’s call, although it is hard to say whether he was widely known outside the court, and Ezekiel was not in Babylon itself). Others suggest, however, that the Daniel mentioned here should be identified with an ancient sage of the Syrian region, known from the Ugaritic texts as a just and pious ruler. This is suggested by the fact that the other two figures, Noah and Job, are from the distant past, and are not Israelite (contrast Jer. 15:1, using Moses and Samuel). Further, the book of Daniel consistently spells the name with the consonants d-n-y-’-l (with vowels, Daniye’l), in Ezekiel it is d-n-’-l (with vowels, Dani’el), which some students of Ezekiel suggest points to the Daniel in Ugaritic texts. On balance, however, there is no conclusive evidence indicating that the Daniel mentioned in Ezekiel is anyone other than the biblical prophet Daniel.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 14:23 The expanded recognition formula (you shall know; cf. Introduction: Style) emphasizes the justice of God’s actions.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 15:1–8 The Useless Vine. This “parable of the vine” is very different from John 15! The metaphor of the vine for Israel is common in the OT (e.g., Ps. 80:8–16; Jer. 2:21; Hos. 10:1), which explains Jesus’ claim in John 15:1 (“I am the true vine”) to embody the people of God. (On Israel as a vineyard, cf. Isa. 5:1–7; Jer. 12:10; as an olive tree, cf. Jer. 11:16; Rom. 11:17–24.) The juxtaposition of vine and harlotry themes in Jer. 2:20–21 is exactly what one finds on a different scale in Ezekiel 15–16. Ezekiel himself further develops the vine metaphor in ch. 17 (cf. 19:10–14). Here, the point is simple: the wood of a vine is fit only for burning—and so it is with the inhabitants of Jerusalem (15:6). Such a pessimistic evaluation is not only consistent with Ezekiel’s oracles up to this point, it also marks his evaluation of the whole of Israelite history in ch. 20.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 15:2 how does the wood … surpass? The Hebrew is difficult to translate. The question may also be rendered, “Son of man, of any wood, what happens to the wood of a vine … ?”

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:1–63 The Faithless Bride. This is both the most infamous passage in the book and also its longest single oracle. The infamy rests not only on the brutal violence it depicts but also on Ezekiel’s shocking use of sexual language. On a general level, the meaning of the passage is clear: the infidelity of Jerusalem has brought upon it the just punishment of God. However, at the level of detail it is very complex, and the boundary between the metaphorical and the literal is sometimes difficult to discern. Some interpreters have also voiced concerns about the legitimization that might be given by this metaphorical description of the violent attacks by the adulteress’s husband (vv. 37–42). Yet it must be remembered that this is an extended metaphor portraying God’s judgment on the nation, and it is by no means intended as a pattern for any human punishment of adultery. Structurally, the passage divides into two large sections, plus a conclusion: vv. 1–43 follow the story of the abandoned child who became a bride; vv. 44–58 broaden the “family” to include two “sisters,” Samaria and Sodom; and vv. 59–63 conclude both parts.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:1–43 Jerusalem, the Foundling Bride. This oracle is an extended metaphor, and so its details cannot simply be equated with certain aspects of literal history. It moves through three phases as God speaks through the prophet: (1) The story of the abandoned girl (v. 6) who becomes a queen (v. 13) is told in the first person through the actions of the king (by implication) who found her (vv. 1–14). (2) Verses 15–34 describe in the third person the sexual promiscuity of the “queen” despite her husband’s generosity. (3) The first-person account resumes to announce the impending judgment on the faithless bride (vv. 35–43).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:1–14 As in ch. 15, the oracle focuses on the city of Jerusalem, and not “Israel” per se. This accounts for the seemingly unusual account of origins given in 16:3 and is the reason why the “sisters” in the second half of the chapter are also both cities. The first stage of the oracle depicts Jerusalem’s helpless and hopeless state—except for the intervention of the passerby (who is God).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:2 The instruction to deliver the oracle comes in quasi-legal language: make known carries overtones of “arraign” (cf. 20:4; also Job 13:23). On abominations, see note on Ezek. 7:3.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:3 land of the Canaanites. Jerusalem’s recorded history predates its takeover by David (2 Sam. 5:6–10) by centuries. The parentage of Amorite and Hittite joins together two of the pagan peoples inhabiting Canaan in pre-Israelite times (cf. Ex. 3:8, and the close joining of these names in Neh. 9:8).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:4–5 cast out. Exposure clearly implies an unwanted birth and certain death. Ezekiel also describes the usual practice for welcoming a newborn. The reason for rubbing with salt is not understood, although the custom persists in some traditional cultures, in the belief that it is beneficial.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:6 Blood is an important motif throughout Ezekiel’s book. Usually it refers to violence, but here to life (cf. Gen. 9:4) and the discharge of birthing.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:7 The narrative quickly moves from infancy to puberty. Still naked, she is vulnerable and in need of resources.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:8 Now at a marriageable age, she is taken as a wife; spread … my garment signals intent to marry (cf. Ruth 3:9), and the covenant signifies the formal commitment (Mal. 2:14). The bonds are formed before the cleansing of Ezek. 16:9.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:9 The cleansing actions here mirror those of v. 4, though now of an adult; blood therefore is menstrual issue.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:10–13 Only after the covenant has been entered are the beautifying gifts given. This culminates in status as royalty (v. 13).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:14 The first-person verbs in the preceding verses find their summation here, as God asserts that Jerusalem’s renown (Hb. shem, “name”) and beauty were entirely of his making (that I had bestowed).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:15–34 God’s address switches now to focus on the actions of his bride in response to his life-giving gifts. The passage is marked by inversions, initially signaled by the phrasing but you … beauty … renown in v. 15, literally reversing the terms of v. 14. Throughout these verses, the gifts given in vv. 10–13, which enhanced and beautified, successively become the means of Jerusalem diminishing and debasing herself. She thus alienates herself from her husband. Structurally, vv. 15–22 present the initial indictment, vv. 23–29 develop the political aspects of the metaphor, and vv. 30–34 summarize the inversions of Jerusalem’s behavior.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:15 played the whore. This language in the OT (Hb. zanah) usually refers to wanton sexual immorality. When used metaphorically of one’s relationship with God, it brings connotations of depraved worship.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:20–22 took your sons and your daughters … these you sacrificed. Cf. the accusation against Manasseh in 2 Kings 21:6 (cf. Jer. 7:31).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:22 did not remember the days of your youth. The failed memory refers both to infancy (v. 4) and puberty (vv. 7, 9). This theme reappears later in the chapter: vv. 43, 60 (cf. 23:19; Eccles. 12:1).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:23–29 Jerusalem’s “whorings” included multiple partners, each involving a turn away from God. The Egyptians (v. 26) had been involved in Judean politics (2 Kings 23:31–35) and proved a perennial temptation for illicit political alliance (cf. Isa. 31:1), as did the Assyrians (Ezek. 16:28) at this point in Judah’s history (see Jer. 2:18).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:30–34 The summary pointedly accuses Jerusalem of being uniquely (v. 34) promiscuous, drawing together the two preceding metaphors. The marriage metaphor relates to infidelity and adultery, offending against exclusive loyalty at the heart of the covenant relationship. The prostitution metaphor relates to the multiplicity of partners, secured by inverting the client relationship. Both metaphors, then, represent reversals, with the second intensifying the offense of the first.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:35–43 An important question for interpretation turns on how far the metaphors are carried into the punishments announced, and where literal razing of Jerusalem shapes this language. The because … therefore terms in vv. 36–37 (Hb. ya‘an … laken) and v. 43 (Hb. ya‘an … gam) structure the grounds and outcome of the accusation in two unequally weighted parts (vv. 36–42, 43). Adultery, along with other illicit sexual relationships, was one of a number of capital crimes in Israel’s law, and so the announcement of execution here is not surprising. Other aspects of the punishments listed do not fit Israelite law so simply. It is unclear how stripping the culprit (v. 37) relates to adultery law. It seems rather to be a case of “poetic justice,” returning Jerusalem to the naked estate in which she was found (vv. 4, 7–8). Nor does entrusting punishment to the illicit partners (vv. 39b–42) or dismemberment (v. 40) appear in biblical law. Here Ezekiel crosses over into the language of city destruction, made explicit in the mention of houses in v. 41. In all this, the supreme element in view is the offense against God, who remains responsible for judgment (vv. 37–39a, 43).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:44–58 Jerusalem and Her Sisters. The second major block in this chapter aligns Jerusalem’s crimes with those of two more cities. Jerusalem suffers in comparison with both “sisters.” The structure parallels that of the preceding section, with metaphorical reminiscence (vv. 44–48) giving way to analysis (vv. 49–52) before divinely imposed outcomes are announced (vv. 53–58).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:44–48 A history much like that of v. 3 is sketched (v. 45), and the “proverb” of v. 44 (see note on 12:21–25) may account for bringing the Hittite mother to the foreground. The relationships are different and more laterally focused now, with no mention of the husband-wife metaphor of the first half of the chapter.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:49–52 Jerusalem’s crimes exceed those of her sisters, but these now fall into the category of social justice (v. 49), beyond that of idolatry.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:49 Sodom … did not aid the poor and needy. There were other sins as well (as narrated in Gen. 19:4–9; cf. Jude 7), but this is the sin that God chooses to highlight through Ezekiel’s prophecy at this point (along with Sodom’s pride, Ezek. 16:50).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:53–58 Unlike the “outcome” of vv. 35–43 (which detailed punishment), here judgment is presupposed and a future restoration envisaged. Neither here nor in the conclusion of vv. 59–63 does future hope exclude shame. Restoring each to their former state (v. 55) puts Jerusalem on the same level as her “sisters” who have been similarly graced.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 16:59–63 The Everlasting Covenant. The final brief passage of ch. 16 explicitly refers back both to the sections on the abandoned child (vv. 8 and 59, 22 and 60) and the “sisters” (vv. 45 and 61), drawing them together in one conclusion. The malleability of the metaphors can be seen in the sisters being given as daughters in v. 61. The everlasting covenant (Hb. berit ‘olam) of v. 60 finds parallels elsewhere in the OT, most significantly in 37:26 (cf. Isa. 61:8); also within the context of bringing back together the old kingdoms of north and south (cf. the hope expressed in Jer. 32:40).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:1–24 The Parable of the Eagles and the Vine. The predominantly theological viewpoint of ch. 16 now gives way to a predominantly political one. It bears the hallmarks of a “fable,” a story form in which flora and fauna take the lead roles in order to teach some lesson (e.g., Judg. 9:8–15). Here two eagles, a cedar, and a vine are the main protagonists, and the story turns on the fortunes of the vine (cf. Ezek. 19:10–14; Isa. 5:1–7). The whole is meant to illustrate the current and imminent state of Judah’s political fortunes, and ultimately its future under God. The fable is narrated in Ezek. 17:1–12 and successively unpacked, first on the natural plane (vv. 11–18) and then in theological terms (vv. 19–21). Finally, the terms of the fable return to articulate an ideal future (vv. 22–24).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:1–10 The Parable Narrated. Although the story is easily followed, it still puzzles the hearer. It proceeds in two phases. A great eagle (v. 3) transplants a twig from a cedar, then plants a seed, which becomes a flourishing vine. But then a second, lesser eagle (v. 7) attracts the vine’s attention and draws it away from the first.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:2 This oracle appears as a riddle, designed to provoke thought, and a parable (Hb. mashal, also translated “proverb”; see 12:22), which depends on some comparison.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:3–5 The terms of the description are significant, as they indicate the relative status of the various characters. This is the greater eagle, taking a topmost twig as well as a seed.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:7 The second eagle lacks the grandeur of the first, while still remaining “great.”

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:8 The new orientation of the vine to the second eagle threatens its choice location and flourishing state.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:9–10 The provocative questions clearly require a judgment on the part of the hearers and implicate them in that judgment—the function of all good parables.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:11–18 The Parable Explained. The first phase of explanation identifies the characters of the fable (vv. 11–15) before spelling out the moral of the story (vv. 16–18). The first eagle is the king of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar, who takes her king, i.e., Judah’s king Jehoiachin (the “twig”), to Babylon (v. 12). The royal offspring (the “seed”) is Zedekiah (v. 13), Jehoiachin’s uncle and replacement to whom Ezekiel never refers as a “king.” Zedekiah’s failure was to break his covenant with Nebuchadnezzar (vv. 13–14) by turning to Egypt (v. 15), whose king was Hophra, the lesser eagle. Ultimately, hope in Egyptian aid will prove futile (v. 17; see Jer. 37:6–10). The breaking of this political covenant will bring disaster on Zedekiah and his people (Ezek. 17:18).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:19–21 The Parable Interpreted. The “natural,” political explanation does not exhaust the meaning of the parable. Zedekiah’s political covenant is now termed my covenant by God (v. 19). God takes full responsibility for the disaster to come (return … spread … bring … enter, all first-person verbs), now seen not as military defeat but as divine judgment.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 17:22–24 A New Parable. God’s action continues as the terms of the parable are used to sketch not a flawed present but an ideal messianic future. The eagles are absent. God chooses a new sprig from the topmost part of the cedar (v. 22) and plants it himself (v. 23). The terms asserting God’s sovereignty in v. 24 resonate with 1 Sam. 2:1–10 and Luke 1:46–55.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 18:1–32 Moral Responsibility. Chapter 18 is sometimes thought to present a novel understanding of Hebrew ethics, as the high politics of chs. 17 and 19 give way to the lot of ordinary people. Some view the notions of corporate responsibility (cf. Josh. 7:19–26) and accumulated guilt (cf. 2 Kings 23:26) as the primary context for Ezekiel’s teaching and observe that, here in Ezekiel 18, he appears to depart from that context and focus on the moral responsibility of the individual. Of course, this reading sits well with modern individualism (which rightly stresses individual moral accountability) but it misses the primary communal focus of Ezekiel. Ezekiel’s “you” addresses are consistently in the plural (note also “house of Israel” in vv. 25, 29). The primary focus of this chapter is not so much on legal individual culpability as on divine justice resting afresh on each generation in accord with what that generation deserves.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 18:1–4 The One Who Sins Dies. fathers have eaten sour grapes … children’s teeth are set on edge. Cf. Jer. 31:29. Once again a proverb (cf. Ezek. 12:22) is introduced as a vehicle for an oracle. The second-person plural forms (What do you mean?) address the whole community in exile. The exilic setting itself is significant; see note on 18:30–32.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 18:5–18 Three Case Studies. Ezekiel exemplifies his teaching by means of three generations: a righteous father (vv. 5–9) and his wicked son (vv. 10–13), who in turn fathers a righteous son (vv. 14–18). Each paragraph follows the same format—the behavior and moral character is introduced, illustrated by a list of characteristic actions, and concluded by a statement regarding either life or death, as appropriate. There are obvious resonances with the Ten Commandments, but not so close as to suggest Ezekiel is citing them. Other such lists appear in Psalms 15 and 24; cf. also Job’s declaration of innocence in Job 31.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 18:19–29 Two Objections. The words yet you say (vv. 19, 25) introduce two objections from Ezekiel’s exilic audience. Again, “you” is plural. Another edition of this teaching appears in 33:10–20.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 18:19–24 Why should not the son suffer for the iniquity of the father? Ezekiel anticipates his audience clinging to their traditional understanding encapsulated in the now defunct proverb (vv. 1–2).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 18:20–24 The soul who sins shall die. Verses 21–24 explain this teaching in what might seem a surprising way for Ezekiel. Verses 21–22 consider the wicked person who then repents and lives rightly before God. Verse 24 considers the opposite scenario. Sandwiched between these is the central declaration of God’s “pleasure” (v. 23) in repentance, and a denial that he has any pleasure in the death of the wicked (see note on 33:11).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 18:25–29 The way of the Lord is not just. The second objection, repeated in vv. 25 and 29, appears to be oriented to the immediately preceding teaching on repentance, rather than being a second objection to the main teaching of the chapter. “Just” (Hb. root takan, vv. 25, 29) has the sense of “weighed” or “measured,” that is, in conformity to a standard (cf. 1 Sam. 2:3). The irony of this objection is rich, coming from people whose lives have not accorded with justice.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 18:30–32 Conclusion: Repent! Repentance is not being urged on Jerusalem, for the preceding chapters affirm that its destruction is assured. Rather, the exiles are pressed to repent and take responsibility for their moral lives. Thus the appeal is to make yourselves a new heart and spirit, in contrast to 11:19 and 36:26, where these are the gift of God. The restatement of God’s displeasure in anyone’s death (18:32; cf. v. 23 and note on 33:11) is the basis for the final entreaty to turn, and live.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 19:1–14 Lament for the Princes of Israel. Ezekiel presents two further political allegories, like that of ch. 17. Unfortunately the symbolism remains unexplained here. In 19:1–9, a lioness produces two cubs who represent the fate of two Davidic princes, while in vv. 10–14 a vine produces branches, as well as a particular “stem” that appears to represent a single Davidic figure. The whole is presented as a lamentation (v. 1), a distinctive form of Hebrew poetry. Some see this lament as ironic, a pseudo-lament that infuses the literary form of the dirge with disparaging content. Others hear in these words genuine sadness, and the conclusion in v. 14b suggests this is the better reading. The political lesson is that even Davidic princes are not immune from the divine consequences of their actions.

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 19:1–9 A Lioness and Her Cubs. Both allegories refer to a mother (vv. 2, 10). One cannot be certain whether a literal queen mother is in view (then most likely Hamutal; 2 Kings 23:31; 24:18), or rather a symbolic reference to the nation of Judah (cf. Gen. 49:9 and “mother” of Babylon as nation, Jer. 50:12). Ezekiel 19:3–4 applies most closely to Jehoahaz, taken captive to Egypt by Pharaoh Neco (2 Kings 23:31–35). The second cub’s identity in Ezek. 19:5–9 is much more problematic. Of possible candidates, Zedekiah remains plausible (see 2 Kings 25:6), but Jehoiachin is more likely (2 Kings 24:12). Both Jehoahaz and Jehoiachin reigned only three months, which is thought to be a problem for the negative assessment of the second “cub” (although cf. 2 Kings 24:8–9).

EZEKIEL—NOTE ON 19:10–14 A Vine and Its Stem(s). For details, cf. the parable of the eagles and the vine in ch. 17. Whereas the lioness-and-cubs story fixed attention on the fate of individuals, the vine-and-stems (Hb. mattot, plural of matteh) passage makes more inclusive reference to the whole dynasty. Verses 12b and 14 of ch. 19 single out one particular strong stem (Hb. matteh), normally translated “staff,” only here referring to a living branch. Wordplay undoubtedly motivated this choice. The reference seems to be to Zedekiah, the last reigning Davidic figure, whose attempts at power politics ended in disaster.