In Chapter 2, we focused on important core values behind the teaching of reading, and in doing so, we looked at some of the things that the Common Core anchor reading standards get right. Let’s now turn our attention to what they get wrong. When it comes to the teaching of reading, the new standards raise numerous major concerns:

David Coleman and Susan Pimentel, two of the principal architects of the CCSS, have said on a number of occasions that when reading, students should “stay within the four corners of the text” (Wilson and Newkirk 2011, 1). By this, they mean that readers should focus entirely on what the author is saying and what the author is doing, and there should be little or no emphasis on connecting the reading passage to the outside world. This poem (or novel, or play), they stress, is really not about your grandmother, so we should stop allowing our students’ interpretations to lead them far away from the printed page. Instead, Coleman argues, our students would be better off if the students studied the text on “its own terms.”

To put it bluntly, this is ludicrous. To illustrate just how so, I ask you to read the following sentence without venturing outside the four corners of the text:

Syria missed an important deadline this week, failing to turn over all its chemical weapons.

How’d you do? My guess is that you can tell me what the text says without straying from the four corners (Syria missed its deadline to turn over chemical weapons). I am sure you can also tell me what the writer does (stylistically, the author connects an independent clause as an “end branch” to the sentence). But can you tell me what the text means without activating your thinking beyond the four corners of the text? No, because deeply comprehending this sentence is impossible without considering the following:

What do you know about Syria?

Where is Syria located?

Who is president of Syria?

What is the history of the current conflict in Syria?

Why has Syria been told to turn over its chemical weapons?

Who has demanded that Syria turn over its chemical weapons?

When and why did Syria agree to do so?

Based on other examples in recent history, what might happen if Syria refuses to comply?

Given the current regime in Syria, how do we interpret this missed deadline?

When my students read of the genocide occurring in Syria, are they not to connect their thinking to their previous studies of Anne Frank’s diary or to Elie Wiesel’s memoir? When my students read the arguments for and against the Affordable Care Act are they not to think about the health histories of their families or their neighbors? When my students read a website “news” story on Fox or MSNBC, are they not to consider the history of these organizations and how these histories might influence the veracity of what they are reading?

Of course I want my students to be able to tell me what a text says. Of course I want them to be able to recognize what the text does, to understand the techniques employed by the author. Of course I want my students to embrace the wrestling match that comes with making deep sense of challenging texts, to wean themselves from me, their teacher, and to move away from the learned helplessness many of them have acquired. I want my students to do all of these things that Coleman and Pimentel advocate. They are all worthy steps in building deeper readers. But they, alone, are not enough. Stopping inside the four corners of the text limits our students’ thinking.

The very reason I want my students to read core works of literature and nonfiction is so that they can eventually get outside the four corners of the text and use these reading experiences to think about, to understand, to gain greater insight into the world they are about to inherit. Books worthy of study should be rehearsals for the real world. They should be springboards to close examination of what is happening in the here and now. If our students read The Grapes of Wrath (Steinbeck 1939) deeply but never use that reading experience to catapult them into an examination of today’s immigration debate, or if our students read Animal Farm (Orwell 1946) and do not apply their newfound thinking to the propaganda they face in a given day, or if our students read The Red Badge of Courage and they do not use the wisdom found in this book to help them better understand the US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan, then they are simply reading stories. True, they might be great stories that stand on their own terms, but surely these works have more to offer than to teach students to recognize when foreshadowing is evident or to gain an appreciation when an author is intentionally using repetition. I want my students to work through “What does the text say?” and “What does the text mean?” as soon as possible so they can spend as much time as possible applying their newfound thinking toward answering, “How does this book make me smarter about today’s world?” I want them to deeply consider what the books mean in our world and for their future.

If we teach students to think only inside the four corners of the text, we are telling them what not to think. And when we tell students what they cannot think, oppression and hegemony occur.

One of the concerns addressed by the authors of the Common Core reading standards is that teachers are often doing too much of the work for the students, especially in the prereading stage. I have seen this firsthand: Teachers “frame” the reading so much that the reading has virtually been done for the students. Students quickly learn that they don’t have to wrestle with the text because the teacher has done much of the wrestling for them. To address this concern of overscaffolding text, the writers of the CCSS suggest this:

The scaffolding should not preempt or replace the text by translating its contents for students or telling students what they are going to learn in advance of reading the text; that is, the scaffolding should not become an alternate, simpler source of information that diminishes the need for students to read the text itself carefully. Effective scaffolding aligned with the standards should result in the reader encountering the text on its own terms, with instructions providing helpful directions that focus students on the text. Follow-up support should guide the reader when encountering places in the text where he or she might struggle. (Coleman and Pimentel 2012, 8)

Though I share the concern that many teachers enable their young readers by doing too much of the heavy prereading lifting for them, Coleman and Pimentel’s statement is problematic on a number of fronts. Allow me to extract some of this statement in chunks and share my concerns:

The scaffolding should not preempt or replace the text by translating its contents for students or telling students what they are going to learn in advance of reading the text.

On the contrary, I frequently tell my students what they are going to learn in advance of reading the text. I have consciously stopped teaching all things in all books; I am trying to avoid turning the novel into a ten-week worksheet. Instead, I teach one or two big things in a book and try to take my students deep into those concepts. I am not trying to fool them; I don’t want these concepts to be secrets. I want my students to know what I want them to know, and I want them to know this before we get started. I want the focus of study out on the table, and I want it to drive a focused reading of the text.

I am not suggesting that I tell my students how the novel will end before they commence reading; I am suggesting that students will know before chapter 1 that the reading of this novel will help lead us to a deeper understanding of X, and achieving a deeper understanding of X will be driven by a central question. (When reading 1984, for example, I might frame the reading of the novel around the following central guiding question: How much power should citizens permit their leadership to have?) This essential question drives a focused reading of the text, and students know this before reading chapter 1.

Effective scaffolding aligned with the standards should result in the reader encountering the text on its own terms. (Coleman and Pimentel 2012, 8)

Let’s use a wrestling metaphor to illustrate my concern about this point. If you have little or no experience as a wrestler, asking you to jump in there and to take on the best varsity wrestler in the county is going to be a very difficult, if not impossible, sell. Simply assuring you that it will be good for you to encounter the wrestler on your own terms—that you should take on this formidable opponent without any help (because that is good for your development as a wrestler)—is certainly not going to be enough to sustain you through the difficult experience. Giving you assurance that help will come from your coach after the other wrestler kicks your butt could possibly be the worst coaching strategy ever.

If I really want to prepare an inexperienced wrestler to take on a difficult opponent, I would use another approach. First, I would get on the mat with the novice wrestler and model some of the wrestling moves one would need to compete. We would practice these moves repeatedly, together. I would demonstrate them, and then I’d have the student repeat them. I would make sure that the inexperienced wrestler got in the weight room to build up his or her strength and stamina. I would demonstrate how each machine in the weight room worked and how to use them properly. I would watch video of expert wrestlers with the student, making sure the novice analyzed the moves made by the expert wrestlers. I would have the young wrestler adopt many of these moves in numerous practice sessions. When I felt the young wrestler was ready, I would have the novice begin wrestling others in scrimmage situations, where I could stop the action at any time and make suggestions. Finally, when the wrestler was up to the challenge, I would set up a match with a difficult opponent, thus completing a gradual release that would put the protégé in a place where he or she could encounter this match on his or her own terms.

Students also need to be gradually released into the “wrestling matches” necessary to make sense of difficult texts. Anyone who has ever taught Shakespeare, for example, knows that the beginning of the play is very hard for students to interpret, even at a literal level. The rhythm and the language of the play are very unfamiliar, and the students’ frustration level can be very high. If you work with reluctant readers, or readers who are behind grade level, it is entirely unrealistic to hand the play to them and expect them to “encounter the text on its own terms.” Though I understand (and empathize) with the goal of having students take ownership of grappling with the complexity of the text, it is wishful thinking that students will initially take on that challenge on their own. Instead, they need to be led there by a teacher who expertly walks them into the work, especially if the work they are about to read is far away from their prior knowledge. The more unfamiliar the work, the more scaffolding will be needed to prepare them for the wrestling match.

Those of us who have taught difficult books also know something else: that somewhere in the middle of the book, the students’ ability to understand it vastly improves. If the teacher has done effective scaffolding, the students begin to “settle in” to the language, to the rhythm of the text. This is where the teacher needs to begin to let go, to begin the process of getting out of the way so that the students can take ownership of wrestling with the rest of the text.

Follow-up support should guide the reader when encountering places in the text where he or she might struggle. (Coleman and Pimentel 2012, 8)

The idea that we should allow students to first “encounter the text on its own terms” before we come in and offer “follow-up support” is backward. Throwing a poor swimmer into the deep end and then tossing him or her a life preserver just prior to the swimmer’s drowning is the wrong approach. Let’s put our students into the deep end with life preservers to cling to, and then gradually teach them how to swim without them. This is not the same as enabling students by doing all the work for them. There is still plenty of text left for students to encounter on its own terms. They are still going to work very hard. But if you begin the unit by throwing them into the deep end of the pool without any coaching, they will drown.

With this in mind, think about the hardest book that you teach—the one book you know will present a major challenge to your students. Have it in mind? My guess is that the book you picked is really hard for your students because it is really far away from their prior knowledge. Not having important background information is what makes the reading of the book hard. If you handed me a book about the Anaheim Angels, I would not need any support before I began reading. (I have been an Angels fan for decades.) On the other hand, if you handed me a book about the Crimean War, your guidance would be necessary to put me on the path to deeper reading. (Without Google at hand, I could not tell you a thing about this war.)

When prior knowledge is sparse or missing, what the teacher does before the kids begin reading is often as important as the actual reading itself. Our job is to ease our students into the difficult reading, to walk them into it. Then, and only then, should the gradual release occur.

Have you ever been invited to a wedding, only to find your place card on the worst table in the reception hall? You know that table; it’s the one next to the kitchen door, the one where you find yourself sitting between a third cousin of the groom on one side and the bride-doesn’t-really-like-him-but-she-must-invite-him-because-she-works-with-him colleague on the other side. At the risk of overdosing this chapter on metaphor, that is the table where recreational reading has been sat.

One visit to the CCSS website will give you a clear indication how little recreational reading is valued (http://www.corestandards.org/the-standards). Recreational reading is not mentioned in the introduction. It is not mentioned in any of the ten anchor reading standards. It is not mentioned in the grade-specific standards for reading literature. It is not mentioned in the grade-specific standards for reading informational texts. It is not mentioned under the discussion of “foundational skills.” It is not mentioned in the appendixes. It is not mentioned in any of these places, period.

To find what the authors think about the value of recreational reading, you will have to dig through the “Revised Publishers’ Criteria for the Common Core State Standards in Language Arts and Literacy, Grades 3–12” (an obscure guide—the equivalent to the worst table at the back of the wedding reception). In this document, Coleman and Pimentel write this:

Additional materials aim to increase regular independent reading of texts that appeal to students’ interests while developing both their knowledge base and joy in reading. These materials should ensure that all students have daily opportunities to read texts of their choice on their own during and outside of the school day. Students need access to a wide range of materials on a variety of topics and genres both in their classrooms and in their school libraries to ensure that they have opportunities to independently read broadly and widely to build their knowledge, experience, and joy in reading. Materials will need to include texts at students’ own reading level as well as texts with complexity levels that will challenge and motivate students. Texts should also vary in length and density, requiring students to slow down or read more quickly depending on their purpose for reading. In alignment with the standards and to acknowledge the range of students’ interests, these materials should include informational texts and literary nonfiction as well as literature. A variety of formats can also engage a wider range of students, such as high-quality newspaper and magazine articles as well as information-rich websites. (2012, 4)

There is a lot to like about this statement. We know that the students who read the most for fun are also the same students who read the best. (We know that students who read the most become our best writers as well.) We also know that the single biggest obstacle to our students becoming proficient readers may be that they simply do not have access to interesting books to read. (For studies that support this claim read Krashen’s The Power of Reading [2004].)

Though Coleman and Pimentel’s statement recognizes the importance of joyful reading, it is buried so far out of the sight of teachers and curriculum directors that it will be all but forgotten. Placing this statement at the equivalent of the back table of the wedding reception is a mistake, because it doesn’t matter how good the anchor reading standards are if our students don’t read. It doesn’t matter how much effort teachers put into teaching the anchor reading standards if our students don’t read. And if we don’t create environments where our students are reading lots of books, they will never become the kinds of readers we want them to be. They will simply remain test takers (and not very good test takers at that). More on how to increase the amount our students read is discussed in Chapter 8.

The path to lifelong reading begins with lots of early reading, so it is disconcerting that the CCSS do not provide specific grade-level reading targets. Goals are important in developing young readers. There is a strong, undeniable connection between time spent reading and performance on reading assessments, yet recommendations on how much students should read are nowhere to be found in the CCSS. Simply stating which reading skills students should learn without suggesting how much students should read sets a dangerous precedent. As we learned in the NCLB era, this approach turned many classrooms into places where drill and skill took precedence, and the overall amount of reading done by many students declined. Teaching skills without establishing reading goals ignores a central tenet to the teaching of reading: If your students are not reading a lot, it doesn’t matter what skills you teach them. Volume matters.

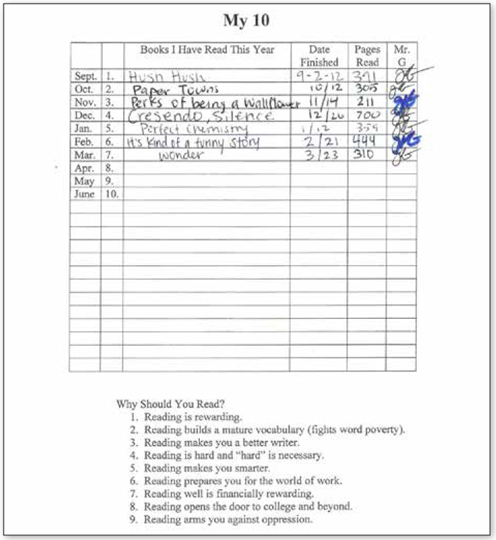

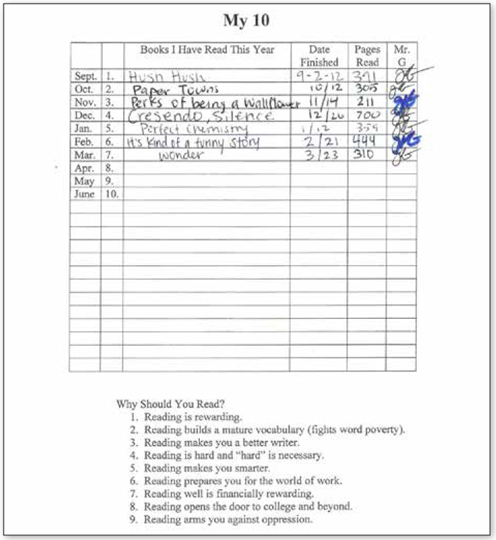

To ensure my high school students are getting enough reading under their belts, I set a goal that they read one self-selected book a month. These books are in addition to the books we may be reading as a class or in book clubs, and to keep track of their progress, I have each of them complete a “My 10” chart (see Figure 3.1). When a student finishes a book, he or she confers with me and I then initial his or her My 10 chart. I do not score the chart; it is a prerequisite. Failure to keep the chart up to date results in the student’s grade being dropped one level on the report card. (I explain this in a letter home to parents and have them sign off on the grading policy.) The My 10 chart creates accountability—but not so much accountability that the reading experience actually ceases to be recreational. (To download a copy of the My 10 chart, go to kellygallagher.org and pull down “Resources” to find “Instructional Materials.”)

Figure 3.1 “My 10” reading chart

When kids read a lot, their fluency and comprehension improve. They build broad vocabularies (see Figure 3.2). They develop stamina. Reading gets easier, which, in turn, invites more reading. As stated earlier, volume matters. If we know all of this to be true, why didn’t the CCSS set reading targets?

Figure 3.2 Results of NAEP study

Kids’ brains, which are still developing, are different from adult brains. Renowned developmental psychologist Jean Piaget identified the following stages of intellectual development in children:

Sensorimotor |

Birth through ages 18–24 months |

Preoperational |

18-24 months through early childhood (age 7) |

Concrete operational |

Ages 7 to 12 |

Formal operational |

Adolescence through adulthood |

(WebMD 2012) |

|

At the preoperational stage, the age where students enter kindergarten, children’s thinking “is based on intuition and still not completely logical. They cannot yet grasp more complex concepts such as cause and effect, time, and comparison” (WebMD 2012). This is why, for example, you cannot teach algebra to a kindergartner. To understand algebraic concepts, explains child clinical psychologist Megan Koschnick, a student has to be able to reason abstractly, and abstract reasoning doesn’t begin to develop in most people until they reach the formal operational stage, which is approximately age 12 (American Principles Project 2013).

This raises serious questions about the standards written for the early grades. When it comes to developing very young writers, for example, the CCSS has students eliciting peer response as a revision technique. But as Koschnick notes, this may be developmentally inappropriate. If one kindergartner in a writing group tells another that his cat should have been black instead of orange, this may stunt the writer’s creativity, leading to frustration and tears. At this early age, we should be more concerned with developing the independence of young writers. Following a standard that asks students to respond to one another’s work may actually hinder the level of independence that we want to foster in our emerging writers.

When it comes to the teaching of reading, Koschnick notes that there are a number of standards that are also developmentally inappropriate (American Principles Project 2013). For example, she cites the following third-grade standard:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.3.5c: Distinguish shades of meaning among related words that describe states of mind or degrees of certainty (e.g., knew, believed, suspected, heard, wondered). (NGA/CCSSO 2010b)

This reading standard asks students to think abstractly at an age when abstract thinking has not been developed. It requires a nuance that most students that age do not yet possess.

The CCSS were written with college and career readiness in mind, and as a result, they were developed backward from young adulthood all the way down to kindergarten. Instead of asking, “What is developmentally appropriate for kindergarten?” and creating standards upward from there, the new standards take a “top-down” approach that has resulted in some new standards that are developmentally inappropriate for some young children. And when you ask students to do things that are developmentally inappropriate, Koschnick notes, bad things happen (American Principles Project 2013). Stress is induced, which causes disengagement from learning. This disengagement, in turn, causes teachers—and parents—to see normally developing students as delayed, which, in turn, may lead to additional problems (for example, this “delay” may prompt educators to recommend the “need” for an IEP when there really is no need for an IEP).

The CCSS suggest that 30 percent of reading done by students should be literary in nature, while 70 percent of their reading should be informational. This 30/70 split is not a guideline for reading done solely in ELA classes; it is a suggestion for the types of reading that students should be doing across an entire school day. But even if the majority of informational reading is done in classes other than English/Language Arts, this still presents a problem for the ELA teacher. Simply, the math doesn’t add up. Sandra Stotsky, Professor Emerita of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, notes that the 30 percent figure

raises important questions that have not been discussed, never mind answered. Since students typically take 4–5 major subjects in high school and English is therefore responsible for only about 20–25% of what they read (assuming students read something in their science, math, history, and foreign language classes), wouldn’t this mean that just about all of the reading instruction in high school English classes should be literary so that students can achieve there most of the 30% quota desired by Common Core? Students would need about 5–10% more literary study somewhere else to satisfy Common Core’s quota, although Common Core’s architects don’t explain where else literary study is to take place or what kind of literary study elsewhere would satisfy their quota, especially if students don’t achieve most of the 30% quota in the English class. (2013)

More likely, Stotsky notes, is that this artificial 30/70 division will lead to a reduction of imaginative literary works taught in the ELA classroom.

Giving students fewer literary works to read is not in their best interest. In Envisioning Literature, Judith Langer, an internationally known reading scholar, notes that the literary experience is “a profoundly different kind of social and cognitive act, one that engages minds in ways that are essentially different from other disciplines, yet are critically important to the well-developed and highly literate mind” (1995, ix). Reading literature, it turns out, develops the mind in unique ways because the thinking that is generated through the reading of literary works is different from the thinking that is generated by reading in other disciplines. It is through literature, Langer notes, that “students learn to explore possibilities and consider options; they gain connectedness and seek vision. They become the type of literate, as well as creative, thinkers that we’ll need to learn well at college, to do well at work, and to shape discussions and find solutions to tomorrow’s problems” (1995, 2).

Literature and poetry have always been at the center of a strong ELA program, and they should remain so. No one would dare tell math teachers that they should no longer teach algebra, and no one should be telling ELA teachers to cut back on the reading of literature and poetry. This trend of moving students away from literary reading is antithetical to good ELA instruction. Kids need more literary reading, not less.

One of the lessons learned in the NCLB era is that the tests started driving what was taught. Those tests valued multiple-choice surface-level thinking, so students were given a lot of practice answering multiple-choice surface-level questions. Those tests did not value writing, so students were not asked to do a lot of writing.

To help prepare students for the type of reading passages valued by the CCSS, many teachers turn to CCSS Appendix B (NGA/CCSSO 2010c), which provides test exemplars and sample performance tasks (see CCSS Appendix B at http://www.corestandards.org/assets/Appendix_B.pdf). The reading passages found in Appendix B are all short excerpts, which, I am afraid, will negatively affect how reading is approached in our classrooms. When excerpts are valued by the exams, the emphasis in many classes will shift to giving students lots of practice reading excerpts. And when the emphasis shifts to reading more excerpts, the emphasis shifts away from sustained reading of longer literary works. This approach creates a choppy curriculum, and students don’t get the crucial practice needed to develop the ability to stay with extended works of literature.

Recently, I tweeted the concern that the heavy emphasis on excerpts might squeeze out the reading of longer works, and I was immediately bombarded with responses from teachers around the country who told me it is already happening in their schools. As Maryanne Wolf notes in Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, when students are not stretched by longer, challenging works, their cognitive windows run the risk of shutting down (2007). Wolf reminds us that the mental acuity required to read an entire novel is a different skill set than the skill set required to simply read an excerpt, and it is important to remember that the ability to read a novel in its entirety comes through the practice of reading novels in their entirety. If the reading of excerpts replaces the reading of novels, students will be denied the opportunity to stretch their capacities at exactly the time when they are in the key stages of brain development.

The exemplars found in CCSS Appendix B create another concern: they are not organic (NGA/CCSSO 2010c). They are randomly selected without any intrinsic connection to what is being taught. Sandra Stotsky notes that in the ninth and tenth grade, you’ll find the following:

Patrick Henry’s Speech to the Second Virginia Convention, Margaret Chase Smith’s Remarks to the Senate in Support of a Declaration of Conscience, and George Washington’s Farewell Address. In fact, most of the “informational” exemplars for English teachers in grades 9/10 are political speeches. Why political speeches, and why these political speeches, as exemplars for English teachers? How many English teachers are apt to understand the historical and political context of these speeches? How did such heavily historically-situated political speeches with few literary qualities come to be viewed as suitable nonfiction reading in an English class? No explanation is given. (Stotsky 2013)

As Stotsky notes, it appears free reign “has been given to people to write standards documents who are, apparently, insufficiently aware of three very important matters: the content of the subjects typically taught in regular public high schools, the academic background of the teachers of these subjects, and the academic level of the courses in a typical secondary curriculum, grade by grade, from 6 to 12” (Stotsky 2013).

These exemplars overlook another concern as well: some of them are too hard to read for those students who are two or three years (or more) behind grade level in reading. There are no tiered texts offered, no differentiation for those readers overmatched at this grade level.

Let’s review the big ideas shared in this chapter and in Chapter 2 about the Common Core anchor reading standards.

COMMON CORE ANCHOR READING STANDARDS |

|

THE STRENGTHS |

THE SHORTCOMINGS |

1. Students are asked to read rigorous, high-quality literature and nonfiction. 2. Students are asked to determine what a text says, what a text does, and what a text means. 3. Close reading of rigorous text is emphasized. |

1. Readers should not be confined to stay “within the four corners of the text.” 2. Prereading activities are undervalued. 3. Recreational reading is all but ignored. 4. There are no reading targets in terms of how much students should read. 5. The reading standards may be developmentally inappropriate. 6. There is a misinterpretation regarding the amount of informational reading. 7. CCSS is driving an overemphasis on the teaching of excerpts. 8. The exemplars are problematic in terms of relevance and reading levels. |

As P. David Pearson notes, the new reading standards, despite the problems I’ve listed, “are still the best game in town” (2014). But just because the new reading standards are the best game in town doesn’t mean we should adopt them without critically challenging them. Let’s not make the same mistake many teachers made when they blindly hitched their wagons to the latest rounds of adopted exams. Let’s remain mindful of the concerns listed in the right-hand column of the preceding table. Let’s take the best of what the Common Core reading standards have to offer, while remaining acutely aware of their shortcomings. And where the new standards come up short, let’s take the steps necessary to ensure that our core values in the teaching of reading are not sacrificed.