I was pumped as my seniors walked into class one Monday morning. This was the day that they would begin reading 1984, one of my favorite novels to teach. After a few introductory comments explaining the concept of a dystopia and hinting at the book’s relevance to today’s world, I paused and asked a question to get the conversation started:

“Does anyone have an idea why we will be reading this book?” I asked, hopeful that someone in the room would make a connection to today’s surveillance-heavy world, to Edward Snowden, to the NSA, to Kim Jong Un, to contemporary propaganda … to anything.

“Cuz you want us to write an essay?” asked Antonio.

The worst part about Antonio’s response was that I truly could not tell if he was being sarcastic. But, really, does it matter? If he was being sarcastic, then his comment can certainly be interpreted as a stinging indictment of what he has come to believe reading to be. If he was not being sarcastic, then his comment can also certainly be interpreted as a stinging indictment of what he has come to believe reading to be. Either way, not good. For Antonio, and I suspect for many of his classmates, great works of literature have been turned into ten weeks of worksheets, culminating in the writing of dry, teacher-directed essays.

When considering what might be a more effective approach to the teaching of reading, it will be helpful to start by examining the ten Common Core anchor reading standards. Yes, I know not all states have adopted the CCSS, but I do believe all teachers will benefit from a close examination of the Common Core anchor reading standards. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the new reading standards by themselves are necessary but insufficient. They get many things right, and they get some things wrong. Examining what they get right and what they get wrong will be beneficial for all teachers of reading, whether your state has adopted the CCSS or not.

In this chapter, we examine what the standards get right about the teaching of reading and how teaching to students’ strengths will make them better readers. In Chapter 3, we examine where the anchor reading standards miss the mark and how we might adjust our instruction to overcome their shortcomings.

First, let’s look at the Common Core reading standards:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.1 Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.2 Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.3 Analyze how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of a text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.4 Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.5 Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.6 Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.7 Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.8 Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.9 Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.10 Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently. (NGA/CCSSO 2010a)

Reading through these standards reminds me that they are a marked improvement over the reading standards adopted in most states during the NCLB era. They ask our students to do deeper, closer reading of rigorous, high-quality literature and nonfiction. This is a move in the right direction.

In looking at what the anchor standards get right, let’s chunk them into three major sections. As P. David Pearson notes, each chunk has a separate reading focus:

STANDARDS |

FOCUS OF THE STANDARDS |

Standards 1–3: Key Ideas and Details |

In standards 1–3, the essential question is what does the text say? |

Standards: 4–6: Craft and Structure |

In standards 4–6, the essential question is what does the text do? |

Standards 7–9: Integration of Knowledge and Ideas |

In standards 7–9, the essential question is what does the text mean? |

Source: P. David Pearson 2014

Being able to answer these questions—What does the text say? What does the text do? What does the text mean?—is an essential reading skill. Let’s look at how we might work these skills into our classroom.

First we’ll review anchor reading standards one through three, categorized as “Key Ideas and Details.”

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.1 Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.2 Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.3 Analyze how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of a text.

Deeper reading starts with a literal understanding of the text. If students cannot figure out what the text is saying—if they cannot retell what is happening—then moving into closer reading and deeper understanding will be impossible. You have to recognize who is a Capulet and who is a Montague before any rich understanding of Romeo and Juliet can take place.

When it comes to making sure my students know what the text says, I start by introducing a series of summary activities. The ability to write summaries is an often overlooked and underrated skill. They are hard to fake, and they give me a quick, formative assessment of what my students understand (and what they are missing in their initial reading). When introducing the skill of summarizing, I start very simply and scaffold my students up from there. Here are some activities I have my students do to sharpen their summary skills:

My students were just beginning to read Lord of the Flies (Golding 1962). I walked them into Chapter 1 by reading the first few pages of the chapter to them and then asked them to complete the reading of the chapter on their own. Before we really dove into the later chapters of the novel, I wanted to see if they understood what was happening in Chapter 1, so I chose a student at random and asked her to pick a number between ten and twenty. She chose seventeen, so I asked my students to write seventeen-word summaries of the chapter. Not eighteen words. Not sixteen words. Seventeen, and exactly seventeen words. Here are some of their responses:

Ralph and Piggy are stranded, but with the help of a conch shell, they discover more kids.

—Alicia

Because of a plane crash, a group of kids are stranded on an island with no adults.

—Miguel

Ralph, who’s “fair,” becomes leader of the plane-crash survivors after uniting them by blowing on the conch.

—Karen

A plane crashes on an island; the kids will have to learn how to survive without groups.

—Jessica

I like this activity on a number of levels. It not only teaches them to summarize but also teaches them to pay very close attention to sentence structure and to word choice. In the preceding examples, notice the “moves” the writers have to make to exactly hit the seventeen-word target. Karen uses a hyphen, and Jessica employs a semicolon as a way of avoiding the use of a coordinating conjunction. This activity requires students to pay attention to their sentence construction, and, better yet, I can read their responses very quickly and get an instant sense of who understands the text and who does not.

To help students refine their summary skills, I have them create headlines for actual newspaper stories. I usually start lightly, often sharing actual headlines that are unintentionally funny. Here are some actual headlines that overstate the obvious:

“Missippi’s Literacy Program Shows Improvement” (note misspelling)

“City Council Runs Out of Time to Discuss Shorter Meetings”

“Man Accused of Killing Attorney Receives New Lawyer”

“Homicide Victims Rarely Talk to the Police”

“Healthy Diet Lowers Death Risk”

“Pregnant Girls are Vulnerable to Weight Gain”

“Most Earthquake Damage is Done by Shaking”

“Tight End Returns After Colon Surgery”

Source: Huffington Post 2012

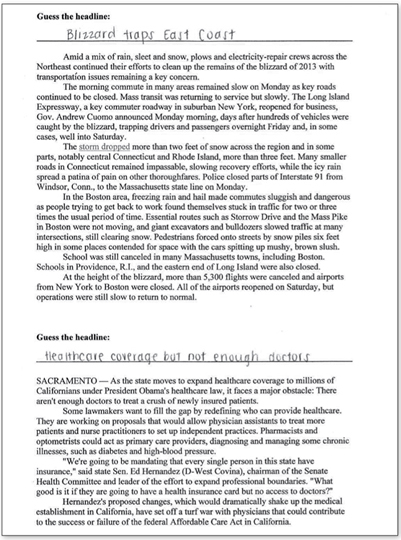

Okay, maybe I would not share the last one with ninth graders, but you get the idea. Once students are warmed up a bit, we have a brief discussion of what makes an effective headline. I then give students newspaper stories with the headlines removed and ask them to supply headlines of their own. In Figure 2.1, you will see an example from Alejandra, a ninth-grade student.

Figure 2.1 Alejandra’s newspaper headlines

Figure 2.2 Ricardo’s headline for Fahrenheit 451 reading

Once my students get the knack of writing newspaper headlines, I have them apply this skill to the literature they are reading by having them write headlines for assigned chunks of the novels. Recently I assigned a section of Fahrenheit 451 (Bradbury 1953) to be read, and as part of a reading check, I began class by having students write a headline for that particular chunk. Along with the headline, I ask for a brief response explaining why the headline they wrote is appropriate. In Figure 2.2, you will see that Ricardo wrote “Montag has an epiphany” as his headline, and then follows by explaining how the character has come to realize the importance of books. Also, notice how I expand the reading check by asking students to explain the significance of both a character (Faber) and of a passage found in the assigned reading.

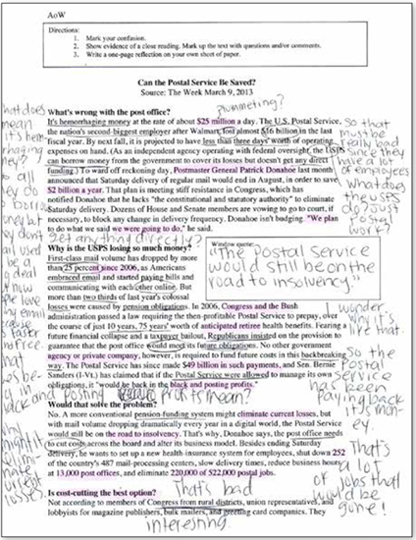

Often in longer magazine articles the editor will choose a key line or quotation and feature it in a window quote, a box placed in the article so that the text of the article wraps around it (see Figure 2.3). The purpose of the window quote is to lure the reader into the piece by highlighting something interesting from the article; in doing so, the window quote often captures a big idea of the piece as well.

Figure 2.3 This magazine page contains a window quote that highlights a key point of the article.

I have students practice writing window quotes in their article of the week (AoW) assignment. (For those unfamiliar with the AoW assignment, I give my students an article to read every Monday. More details on the AoW assignment can be found in my book Readicide [Gallagher 2009].) In Figure 2.4, you will see an example of a window quote written from an AoW that explains that the postal service is awash in red ink and is considering curtailing Saturday mail delivery.

Figure 2.4 This student’s annotated AoW includes a window quote selected by the student.

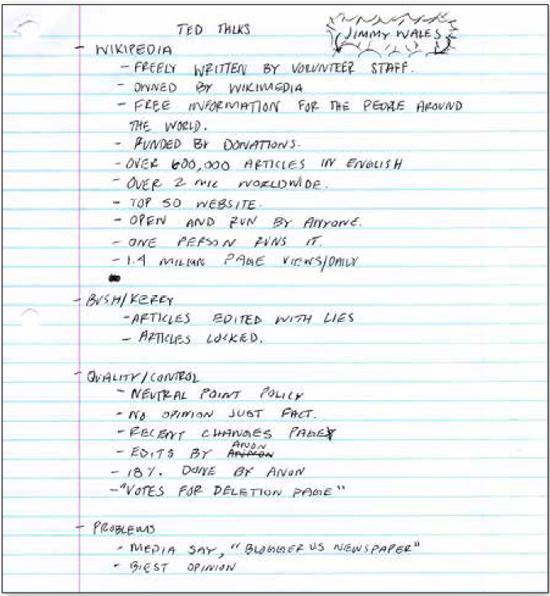

Another way of helping our students sharpen their summary skills is to move them beyond the printed page and have them work with digital text. I use a series of Ted Talk video clips to do this, starting with a brief lecture by Jimmy Wales (2005), the cofounder of Wikipedia. Before I show this clip, I simply ask students to listen carefully to the lecture and to write down the key points. I know this is not the best teaching, but I intentionally underteach because I want to see what kind of listening and note-taking abilities students possess prior to any support from me. Upon completion of the TED Talk video clip, I collect the students’ notes, pick a couple of models that show students seem to have captured the gist, and use them to generate whole-class discussion on what makes an effective summary (see Figure 2.5 for Javier’s notes).

Figure 2.5 Javier’s notes on a TED Talk

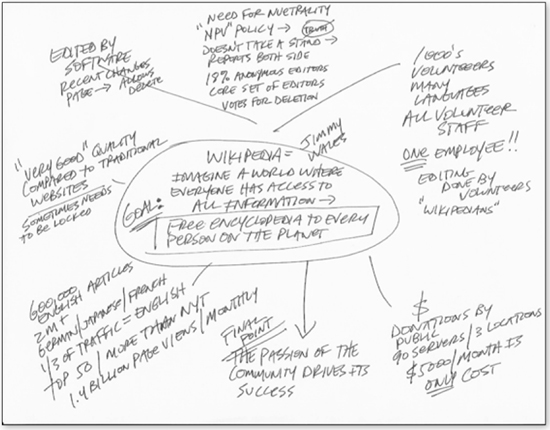

I find consistently that, without any instruction on how to take notes, many of my students follow the approach found in Figure 2.5—a very linear, step-by-step retelling of the text. There is nothing wrong with this particular approach, but I want my students to know there are other ways to take notes. To get them thinking in other directions, I show them the notes I took of the Wikipedia speech—notes I intentionally crafted in a nonlinear fashion (see Figure 2.6). I then choose another TED Talk for students to “read” and I ask them to emulate this nonlinear note-taking technique.

Figure 2.6 I show students this sample of my nonlinear notes.

After my students have created individual notes from watching any TED Talk, I often put them in groups and give them a few moments to compare their summaries. Once they’ve had a little time to identify the similarities and differences between their notes, I give them ten minutes to compile all of their notes and turn them into a single-paragraph group summary. This activity requires students to reconsider what is truly important in their individual notes, and, in doing so, generates good discussion on what should stay in and what should be removed from the group paragraph. See Figure 2.7 for a group summary my students composed after watching and comparing their notes on the TED Talk on Wikipedia.

Figure 2.7 A small-group summary based on students’ notes

Once my students get some practice creating straight summaries, I move them into deeper water by having them do a version of Cornell Notes. I ask them to turn their notebook pages to landscape mode and to divide their papers into a one-third/two-thirds T-chart. On the left (one-third) side, students record questions, key ideas, and important words and concepts. On the right (two-thirds) side, they record notes about the TED Talk.

In Figure 2.8, you will see Jocelyn’s notes from watching Sir Ken Robinson’s TED Talk titled “How Schools Kill Creativity” (2006). When, in the left-hand column, Jocelyn asks questions like “What if great ideas weren’t cherished?” and “How did the humanities and arts lose their value as education?” she is moving beyond summary and getting into deeper levels of cognition.

Figure 2.8 Jocelyn’s notes on a TED Talk

When students have finished their Cornell Notes, I want them to share and discuss them, but instead of simply having them turn and talk, I find that I will get much more meaningful talk if I have the students first do five minutes of private reflection via writing. Sometimes, students need to think before they can think, and giving them time to discover what they are thinking via writing leads to a much richer discussion when the quick-write is over. In Figure 2.9, you will find the reflection Jocelyn wrote before joining the group discussion. (You’ll notice that Jocelyn references the Puente Project, a University of California outreach program designed to help underrepresented students make it into a four-year university. She is a Puente student.) Five minutes of writing time positioned Jocelyn to be a better participant when the subsequent conversation began.

Figure 2.9 Jocelyn’s private reflection writing

Another strategy that reinforces summary skills but also moves students into deeper thinking is to ask students what has been left out. I discuss this strategy in Deeper Reading (2004), but here I apply it to the reading of digital text. I show my students Jill Bolte Taylor’s TED Talk titled “Stroke of Insight” (2008). In this video clip, Taylor, a scientist who specializes in brain disorders, describes what she learned when she herself suffered (and recovered from) a stroke. Before my students view the clip, I preview some key difficult vocabulary, which the students take notes on. Below the vocabulary in their notebooks, the students create a T-chart where on the left side they record what the text says and on the right side they record what is not said in the clip. (See Figure 2.10 for Licci’s chart.) Capturing what is said helps strengthen my students’ summary skills, and capturing what is not said (what is left out) drives them to think about the text at deeper levels (in this case the “text” is a video clip).

Figure 2.10 Licci’s notes list both what is said and what is not said in a text.

Having students “read” digital clips creates an added bonus in that it helps students sharpen their ability to listen closely, a skill many of my students lack. (For more on sharpening listening skills, see Chapter 7.)

If students do not understand the text at a surface level, they are not going to develop their deeper reading skills. All the strategies mentioned in this chapter thus far (17-Word Summaries, Write a Headline, Window Quotes, Digital Text Summaries, Group Summaries, Summary Plus, and What Is Left Out?) are designed to help students answer the question, “What does the text say?” Once this is established, it’s time to move students into the kind of reading demanded by the Common Core reading standards that relate to the question, “What does the text do?”

Let’s look at anchor reading standards four through six, categorized as “Craft and Structure.”

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.4 Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.5 Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.6 Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text.

When we think about how to move our students into deeper levels of reading, it is helpful to remember an expression that has been used for years at National Writing Project sites: “Students need to read like writers and they need to write like readers.” The first half of that statement—“Students need to read like writers”—is especially true when it comes to getting students to recognize what a text does.

To better understand this notion of reading like a writer, read the following passage from Martin Luther’s King Jr.’s famous “Letter from Birmingham City Jail”:

I guess it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say wait. But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick, brutalize, and even kill your black brothers and sisters with impunity; when you see the vast majority of your 20 million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see the tears welling up in her little eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see the depressing clouds of inferiority begin to form in her little mental sky, and see her begin to distort her little personality by unconsciously developing a bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five-year-old son who is asking in agonizing pathos: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?” when you take a cross country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” men and “colored” when your first name becomes “nigger” and your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and when your wife and mother are never given the respected title of “Mrs.” when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tip-toe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”—then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into an abyss of injustice where they experience the bleakness of corroding despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience. (1963)

In a traditional, NCLB-influenced classroom, students might be asked to read this passage and respond to traditional questions such as the following:

List three things that Dr. King rails against.

Explain what Dr. King means by “nobodiness.”

What is Dr. King’s central claim in this piece?

What evidence supports this claim?

These questions are designed to see if the students have gained a surface-level understanding of the text (What does the text say?). But if we want to encourage our students to read like writers, we might, instead, start by asking some of the following questions:

What makes this an effective piece of writing?

What techniques are used by the writer that elevates the writing?

What “moves” does the writer make?

What does he do here? What does he do there?

This is a different line of questioning than many of our students are used to answering. “Reading like a writer” means we want the students to move beyond telling us what the text says and to recognize the “moves” the writer is making. In the excerpt from “Letter from Birmingham City Jail,” for example, we might want our students to recognize King’s use of intentional repetition (“when you … when you … when you…”), or his techniques of using semicolons to separate long items in a series, or of his infusing an anecdote about his own daughter as a way to forge a connection with the reader. When we ask students to read like writers, we are not asking them to recognize what the text says; we are asking them to recognize how the text is said.

When my students were reading All Quiet on the Western Front (Remarque 1929), I brought in passages from Kevin Powers’s The Yellow Birds, a brilliant novel that follows Bartle, an American soldier, through the Iraq War. Near the end of the novel, Bartle has come home and is suffering from PTSD. He can’t stop his mind from recounting the horrors of the war, and as a result, he has become suicidal. I asked my students to read the following passage like writers. I invite you to do the same. What do you notice? What makes this an effective piece of writing?

Or I should have said I wanted to die, not in the sense of wanting to throw myself off the train bridge over there, but more like wanting to be asleep forever because there isn’t any making up for the killing of women or even watching women get killed, or for that matter killing men and shooting them in the back and shooting them more times than necessary to actually kill them and it was like trying to kill everything you saw sometimes because it felt like there was acid seeping down into your soul and then your soul is gone and knowing from being taught your whole life that there is no making up for what you are doing, you’re taught that your whole life, but that even your mother is so happy and so proud because you lined up your sight posts and made people crumble and they were not getting up ever and yeah they might have been trying to kill you too, so you say, What are you gonna do?, but really it doesn’t matter because by the end you failed at the one good thing you could have done, the one person you promised would live is dead, and you have seen all things die in more manners than you’d like to recall and for a while the whole thing f***ing ravaged your spirit like some deep-down sh*t, man, that you didn’t even realize you had until only the animals made you sad, the husks of dogs filled with explosives and old arty shells and the f***ing guts and everything stinking like metal and burning garbage and you walk around and the smell is so deep down into you now and you say, How can metal be so on fire? and even back home you’re getting whiffs of it and then that thing you started to notice slipping away is gone and now it’s becoming inverted, like you have bottomed out in your spirit but yet a deeper hole is being dug because everybody is so f***ing happy to see you, the murderer, the f***ing accomplice, the at-bare-minimum bearer of some f***ing responsibility, and everybody wants to slap you on the back and you want to start to burn the whole god**n country down, you want to burn every god**n yellow ribbon in sight, and you can’t explain it but it’s just, like F**k you, but then you signed up to go so it’s all your fault, really, because you went on purpose, so you are in the end doubly f**ked, so why not just find a spot and curl up and die and let’s make it as painless as possible because you are a coward and, really, cowardice got you into this mess because you wanted to be a man and people made fun of you and pushed you around in the cafeteria and the hallways in high school because you liked to read books and poems sometimes and they’d call you fag and really deep down you know you went because you wanted to be a man and that’s never gonna happen now and you’re too much of a coward to be a man and get it over with so why not find a clean, dry place and wait it out with it hurting as little as possible and just wait to go to sleep and not wake up and f**k ‘em all. (Powers 2012, 144)

What did you notice? What techniques does the writer employ? My students are a little taken aback when they realize that this entire passage is one massive run-on sentence. Obviously, Kevin Powers knows he has broken a major writing rule; his flagrant disregard for sentence boundaries is intentional. Why he broke the run-on rule, and what effect he was hoping this might have on the reader, generates interesting classroom discussion. As in the Kevin Powers passage above, it is important that my students recognize that proper punctuation is not simply an editing concern; I want them to recognize that punctuation can be manipulated to bring additional meaning to the piece, that a writer can punctuate for reasons beyond correctness. To illustrate this point, I share the following sentence I have written:

If they ask, I will not do it.

And then I share how I revised this sentence:

If they ask, I. Will. Not. Do. It!

How would you characterize the moves I made in the revised sentence? Are they editing moves? Or are they revision moves? Are they both? Editing is not just a process to make sentences correct. Editing is often done to add meaning to what I am trying to say. Good writers often edit for effect.

One way to help students pay attention to writers’ moves is to have students carefully consider the choices that poets make, particularly when it comes to deciding where line breaks should be placed. I could, for example, take the mentor sentence from above and write it poetically more than one way:

If they ask,

I will not do it.

… has a different feeling than …

If they ask,

I will not do

It.

After having students consider how a single line might be divided in different ways, I might choose a stanza from another poem for them to analyze. For example, consider the following from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “Charge of the Light Brigade,” where the poem describes soldiers storming into battle on horseback:

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley’d and thunder’d;

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

(1998, 408)

In this stanza, Tennyson doesn’t just describe the rush into battle. If you read it aloud, you can hear a rhythm woven into the poem—a meter that enables the reader to actually hear the horses’ hooves as they gallop into battle. The way the poem is written adds depth to one’s understanding of the intensity of the battle.

Another way, via poetry, to teach students to pay attention to an author’s craft comes from W.D. Snodgrass’s De/Compositions: 101 Good Poems Gone Wrong, where he rewrites original poems to make them deliberately worse. For example, here is the first stanza of Emily Dickinson’s “I Heard a Fly Buzz–When I Died”:

I heard a Fly buzz–when I died—

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Stillness in the Air—

Between the Heaves of Storm—

(Dickinson 1976, 223)

Here is Snodgrass’s revision of the stanza:

A fly got in, the day I died;

The calm in my bedroom

Was like the quiet in the air

Between the blasts of storm

(2001, 85)

Snodgrass reads the original stanza and then has the students read the rewritten version. When they have finished, Snodgrass asks them to identify the most “scandalous” thing he has done to the poem. Why, for example, is the use of the word “Stillness” in the original poem a better choice of diction than the word “calm” in the second version? And why did Dickinson choose to capitalize “Stillness” (when “calm” is not capitalized)? Having students pay attention to the differences between the two poems pushes them to sharpen their close reading skills.

Teaching students to recognize what a writer is doing is a major step in having students actually do what the writer is doing (as I demonstrate in Chapter 6). Noticing what a writer does, of course, requires the reader to read closely—a skill valued by the CCSS, as seen in the following statement by the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC):

Close, analytic reading stresses engaging with a text of sufficient complexity directly and examining meaning thoroughly and methodically, encouraging students to read and reread deliberately. Directing student attention on the text itself empowers students to understand the central ideas and key supporting details. It also enables students to reflect on the meanings of individual words and sentences; the order in which sentences unfold; and the development of ideas over the course of the text, which ultimately leads students to arrive at an understanding of the text as a whole. (PARCC 2012, 7)

We want our students to develop the habits of mind associated with close reading, and getting them to do so requires careful practice. Teaching students to read closely makes them better readers and writers, and a large part of developing close-reading skills begins by being able to recognize the author’s craft.

So far, we have looked at anchor standards 1–3, which ask “What does the text say?” and anchor standards 4–6, which ask “What does the text do?” We now turn our attention to anchor standards 7–9, titled “Integration of Knowledge and Ideas,” which essentially ask for a third kind of reading: “What does the text mean?”

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.7 Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.8 Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.9 Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

Answering “What does the text mean?” requires the reader to move beyond the literal interpretation and to start to think inferentially. To do so, students must be taught how to make claims from the text. To help my students to develop this skill, I start small. I begin by using factoids taken from the “Harper’s Index,” a one-page collection of statistics found in every edition of Harper’s magazine. Here is an example of one factoid:

Percentage change since 1996 in the number of U.S. children living in poverty: +12

(Harper’s 2013)

Students are asked to make a claim based on this factoid. To help them, I ask what can be inferred from the factoid. Here are some of their responses:

The economy is bad. There are fewer jobs.

More people are being laid off than in 1996.

Salaries have been cut. Even people who have jobs are making less.

Things cost more than they used to.

From there, I will give students a pair of factoids and ask them to create a claim that addresses both of them:

Portion of U.S. public-school students who are Latino: 1/4

Portion of U.S children’s books published annually that are by or about Latinos: 1/50

(Harper’s 2013)

Their responses:

History books do not tell the full story.

Book publishers are missing a large market.

Racism still exists.

This imbalance may change soon as the Latino population grows.

From “Harper’s Index,” I move students into making claims from visual texts. As Carol Jago notes,

Our students are bombarded by visual images yet rarely stop to analyze them. I’m not talking only of advertising. Media study units are popular components in many English syllabi. What isn’t much in evidence in the secondary English curriculum are rhetorical readings of visual texts. (Jago 2013, 1)

Jago is right. Using visual texts is an excellent way to enable students to deepen their reading skills (and important given the amount of visual texts our students will read in their lives). I begin with having my students wrestle with infographics, starting with “Readers round the world” found on The Digital Reader website (Hoffelder 2013; see Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11 Students examine infographics like this one to deepen reading skills.

I place students in groups and give them a few minutes to read and discuss the image; I eventually bring it back to a whole-class discussion, making sure they understand the image on a literal level. Then I ask them to begin inferring claims. “According to this infographic, people in India read more than anyone else in the world,” I say. “Why might that be?”

Their responses (claims):

There are fewer technological distractions for children growing up in India.

Kids in India do more reading in school.

Their school days are longer.

India has more bookstores.

Students in India have more digital access.

Maybe the graphic is wrong. Who is the source?

It is possible that some of these claims are incorrect. I don’t know, for example, if Indian children have fewer technological distractions. I have to remind myself that making numerous incorrect assumptions is necessary before students can begin making correct assumptions. It is important to keep in mind that even as adults, we often make incorrect inferences. How do we get better at inferring? By doing it. We are better than our students in applying inference skills because we are more experienced in doing so. Building strong inferential skills takes practice.

From “Readers round the world” I ask my students to interpret two more infographics. The first provides data on urban life in the United States, including statistics about life expectancy, demographics, and possible advantages. The second infographic is about American voting trends, citing voter turnout percentages based on classifications such as race, gender, and income level. While reading these, I ask students (1) to make a list of what they have learned by reading the infographics and (2) to generate claims from what they’ve learned. In Figure 2.12, you’ll find Alicia’s response to the infographic about the growth of cities, and Figure 2.13 shows her response to the voting trends infographic.

If you want to slip in a message that reading is important, you might have students analyze Janet Neyer’s infographic, “Why Read?” (Figure 2.14). This infographic can be downloaded by selecting “Instructional Materials” in the “Resources” section of my website, kellygallagher.org.

Figure 2.12 Alicia’s response to an infographic about the trend toward urban living in the United States

Figure 2.13 Alicia’s response to an infographic about how America votes

Figure 2.14 “Why Read?” infographic by Janet Neyer

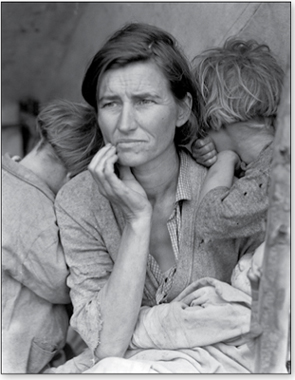

When trying to move my students beyond surface-level thinking, I move them past infographics and into analyzing photographs. I start with selections from Life’s 100 Photographs That Changed the World, choosing photos that provoke the reader (Sullivan 2003). In Figure 2.15, for example, you will see Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, which captures a thirty-two-year old California farmworker who scavenged vegetables and hunted wild birds in a desperate attempt to feed her seven kids.

I ask the students to first consider what the text “says,” asking them to read the photograph carefully. I have them list what they notice. One group’s responses:

The woman looks sad/worried.

The children have buried their faces away from the photographer.

Their clothes are dirty and torn.

They appear very poor.

The wall behind them looks dirty. Are they in a tent?

Even without a working knowledge of the Dust Bowl, students are able to discern what the text “says.” They understand, on a literal level, that the photo puts the spotlight on poverty.

Figure 2.15 Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother

Once the initial understanding of the photograph is established, I introduce Lange’s work, telling the students that she was famous for documenting the poor during the Great Depression. I then ask the students a different set of questions; here is a recorded classroom conversation:

“What was the photographer’s purpose in taking this photo?” I asked.

“She was trying to show poor people to the rest of the world,” Brianna said.

“Why?”

“So they would understand how hard it is to be poor.”

“That’s it? To show others what poverty looks like? Any other reason?”

“To show people she had skills as a photographer?” Michael offered.

“C’mon. Really? What might be a deeper purpose for sharing this photo?”

“Maybe she thought the photo might get people to do something about it,” Alex jumped in.

“I don’t know. Send food or money.”

“Well, that brings up another interesting question: Who did Dorothea Lange hope would see her photo?”

“Rich people,” Samuel offered.

“Okay. But Alex said that maybe the photo would spur people to do something about it. Can you think of others besides rich people who might be in a position to do something about it?”

(Pause.)

“People who make the laws?” Alicia offered.

“Politicians,” Elias added.

“People who vote,” said Ricky.

These students have moved beyond literal understanding and into consideration of what the photo means. Once they understand that a single photograph can lead to creating real change in the world, I give them other influential photographs to consider. You might try George Strock’s photo that depicts dead American soldiers washed up on the beaches of Papua New Guinea during World War II. (This photo is easily found by searching Google images.) Life magazine published this controversial photo “in concert with government wishes” because Franklin D. Roosevelt “was convinced that Americans had grown too complacent about the war” (Sullivan 2003). This photo had the desired effect: “The public, shocked by combat’s grim realities, was instilled with yet greater resolve to win the war” (Sullivan 2003). Or try Charles Moore’s Birmingham, which shows water hoses being turned on African Americans in Alabama in 1963. This iconic photograph is famous for rallying public support for the plight of African Americans in the early days of the civil rights movement. This photograph is easily found by Googling both the author’s name and the name of the photograph.

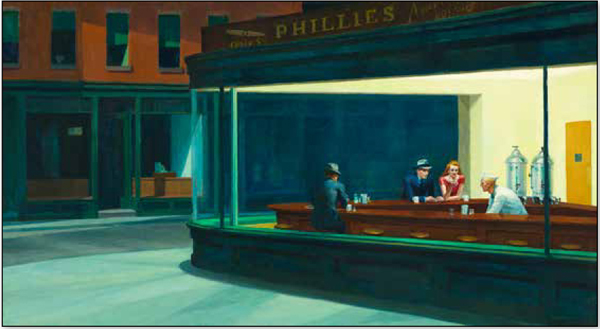

After analyzing photographs, students can easily transfer that skill to the reading of paintings. I start with Edward Hopper’s well-known Nighthawks, which depicts three people sitting at a diner counter at night (see Figure 2.16). In their initial readings of the painting, I make sure students pay attention to Hopper’s unusual use of perspective, color, and light. Once they wrestle with the painting a bit, I shift their thinking by asking them to consider the painter’s claim, to consider what he might be trying to say in this painting. Many of my students focus on the solitary figure at the center of the painting and suggest that Hopper is saying something about loneliness and isolation. I also like introducing my students to Nighthawks because it is one of the most recognizable paintings in American art, and I want them to have this piece of cultural literacy (this will enable them, for example, to understand the reference when they see Homer sitting at the same lunch counter in an episode of The Simpsons).

Figure 2.16 Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks

In her books, Barbara Greenwood weaves fiction and nonfiction together to help the reader make sense of historical events. In A Pioneer Sampler: The Daily Life of a Pioneer Family in 1840, for example, she chronicles a year in the life of the fictional Robinson pioneer family, and to demonstrate these hardships, Greenwood weaves in nonfictional artifacts throughout the book (1994). When the Robinson family builds a log cabin, Greenwood provides the reader with a visual cut-out that demonstrates how a log cabin is constructed. To demonstrate life at home, Greenwood interrupts the narrative with instructions on how to make maple syrup. As the reader works through the book, he or she encounters a number of real artifacts that lend authenticity to the fictional story.

In another Greenwood book, Factory Girl, we meet young Emily Watson, who works eleven hours a day clipping threads from blouses in the Acme Garment factory (2007). Emily’s story, though fictional, is grounded in the real-life hardships of children working in sweatshops in the early 1900s. Throughout Emily’s tale, Greenwood sprinkles in advertisements for the various clothing styles that were in vogue at the time along with a number of photographs that depict life in the factories. Through the weaving of fiction and nonfiction, Greenwood gives students a richer understanding of history.

My colleague Donna Santman suggests that students be instructed to use Greenwood’s approach with the novels they are reading in class. A student reading Lord of the Flies, for example, should be asked to consider what nonfiction artifacts he or she would use throughout the text to deepen the readers’ understanding of the novel. The student might include the following nonfiction examples:

• Survival tips on how to survive a plane crash

• A chart identifying which plants are edible and which plants are poisonous

• Directions on how to start a fire from scratch

• Information on conch (and other) shells

• A diagram on how to build a thatch hut

Deciding which artifacts compliment the reading of the book is only half the job; once the artifacts are created, the student must then decide where to strategically place them in the novel. Students are asked to share their thinking behind the placement of the artifacts. How do these placements heighten the readers’ understanding of the book?

Greenwood’s idea of weaving nonfiction artifacts into works of fiction can be used with any novel or play.

When we have students read speeches, paintings, novels, works of nonfiction, magazines, and TED Talks and other digital texts, we are not just teaching them reading skills. We are deepening their understanding of the world, which, in turn, makes them better readers. As the CCSS rightly recognize, teaching students to recognize what a “text” says, does, and means is vitally important to developing literate citizens. These standards are rich, they are necessary, but as I said earlier in this chapter, they, alone, are insufficient. To examine where these reading standards fall short, turn this page.