In the 1964 World Series between the New York Yankees and the St. Louis Cardinals, some of the Cardinals players noticed that Yankee outfielder Tom Tresh had a slight limp as he ran out to his position in left field.

“Does he have a bum knee?” someone asked.

“No,” replied third baseman Ken Boyer. “He runs like that because that’s the way (Mickey) Mantle runs” (Halberstam 1994, 323). This form of emulation amongst ballplayers is not uncommon, notes Tim McCarver, Cardinal catcher and Hall of Famer. McCarver often noticed that “young players, consciously or unconsciously, tended to take on the mannerisms of the best players of their teams” (Halberstam 1994, 323). There is no mystery as to why they did this: Aspiring young players study the superstars in hope of discovering the magic ingredients that fuel their amazing feats—from how they carry themselves to the way they swing the bat. After all, there’s no better model for success than those who are successful.

It’s not my job to teach my students how to play baseball, but if it were, I’d want them to run (and hit) like Mickey Mantle, too. Instead, my job is to build young readers and writers, which is why I want them to consciously and unconsciously emulate the mannerisms of the Mickey Mantles of adolescent literacy—the John Greens, the Laurie Halse Andersons, the Chris Crutchers. Providing models for emulative purposes is critical to deepening my students’ ability to read and write.

To show my students the importance of models, I begin by distributing a blank sheet of paper to everyone in the class. I tell them that I am going to name an item and that I want them to draw it to the best of their abilities. When they are ready, I write “Kakapo” on the board and tell them to begin. Without fail, they ask, “What is a Kakapo?” I tell them that if they don’t know what it is, they should guess what it might be and to begin drawing what they think it might look like.

Students come up with some unique creations. After some sharing (and some laughter), I show them a photograph of an actual Kakapo, which is a flightless member of the parrot family with a greenish-yellow underbelly, a broad head, a large bill, and an owl-like circular facial disk (BirdLife International 2014). Of course, their original drawings are inaccurate, so after they have looked at the photograph for a few seconds, I remove it and then give them two minutes to revise their drawings. Immediately, their drawings improve. The point of the lesson? To draw a Kakapo, one must know what a Kakapo looks like. This lesson helps them to internalize the importance of having a model at their sides.

I am not charged with teaching my students how to draw birds, but I am charged with teaching them how to read and write better. Instead of photos of Kakapos, they need lots of models of exemplary writing. If we want our students to write compelling arguments, or interesting explanatory pieces, or engaging narratives, we need to have our students read, analyze, and emulate compelling arguments, interesting explanatory pieces, and engaging narratives. Before they begin writing, they need to know what the writing task at hand looks like.

When it comes to the teaching of writing, effective modeling entails much more than handing students a mentor text and asking them to emulate it. It is not a “one and done” process. Rather, students benefit when they pay close attention to models before they begin drafting, they benefit when they pay close attention to models while they are drafting, and they benefit when they pay close attention to models as they begin moving their drafts into revision. Mentor texts achieve maximum effectiveness when students frequently revisit them throughout the writing process. Let’s explore the value of modeling in each of these stages.

If we want our students to write in a particular discourse, such as poetry, then we should begin by providing them with lots of poems to read. As students are swimming in poems, we must move beyond simply asking them to retell what the poems say; to maximize the effectiveness of the models, students need to be taught how to read like writers—how to notice the techniques, the moves, and the choices the poets make. Students are accustomed to being asked what is written, but asking them to recognize how the text is written is a different kind of reading than many of them are accustomed to. This shift—from what something says to how it is said—is seen in three of the ten Common Core anchor reading standards:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.4 Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.5 Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.6 Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text.

All three of these standards ask readers to answer the same basic question: What did the writer do? To get my students to begin thinking in these terms, I start them with “Four Skinny Trees,” a vignette from Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street:

They are the only ones who understand me. I am the only one who understands them. Four skinny trees with skinny necks and pointy elbows like mine. Four who do not belong here but are here. Four raggedy excuses planted by the city. From our room we can hear them, but Nenny just sleeps and doesn’t appreciate these things.

Their strength is secret. They send ferocious roots beneath the ground. They grow up and they grow down and grab the earth between their hairy toes and bite the sky with violent teeth and never quit their anger. This is how they keep.

Let one forget his reason for being, they’d all droop like tulips in a glass, each with their arms around the other. Keep, keep, keep, trees say when I sleep. They teach.

When I am too sad and too skinny to keep keeping, when I am a tiny thing against so many bricks, then it is I look at trees. When there is nothing left to look at on this street. Four who grew despite concrete. Four who reach and do not forget to reach. Four whose only reason is to be and be. (1991, 74)

After reading this passage, students are asked to identify the techniques employed by Cisneros. For example, I want them to recognize how she employs personification (“Four skinny trees with skinny necks and pointy elbows like mine”), how she uses similes (“they’d all droop like tulips in a glass”), how she uses intentional repetition (“Four who … Four who … Four whose …”), and how she stacks the end of the passage with a series of intentional fragments. I also want them to understand that she uses four skinny trees as a central metaphor for the struggle of growing up in poverty.

Having students recognize these techniques before they begin writing helps students adopt these techniques when they get to the drafting stage.

When George Lucas was making Star Wars, his special effects team was at a loss on how to realistically film the aerial dogfight scenes. They storyboarded them, but they found that simply drawing the scenes on paper did not help them to understand the pacing and the rhythm of the fights. Needing additional inspiration, they spliced together footage of real dogfights from World War II documentaries and copied them. Many of the dogfight scenes shown in Star Wars are frame-by-frame replicas of actual war footage.

This Star Wars anecdote reminds me of the first time I was asked to write a grant proposal. I was feeling very unsure of myself, understandable given the fact that my bosses were counting on me to write something I didn’t know how to write. Can you guess what I did next? (Anyone who has written a grant proposal knows where I am going with this anecdote.) I found a previously successful grant proposal and studied it, paying close attention to its structure, syntax, and tone. Like the Star Wars special effects team, I found a strong model and I emulated it.

Today, when my students sit down to write, they also benefit greatly when they have exemplary models to read, analyze, and emulate—models to guide them as they are drafting. These models should not come solely from professional writers; students also benefit greatly from studying models produced from the best writer in the classroom—the teacher. I am not suggesting that we should make students sit still while the teacher drafts an entire essay in front of the class; I am suggesting that the teacher write in short five- to seven-minutes blasts in front of students, thinking out loud while composing, and that this kind of modeling be done frequently. For those who are reluctant to write in front of their students for fear that they may be revealed as mortal, remember that students benefit greatly by seeing the teacher struggle. It reinforces a central lesson: that for all writers, even for the teacher, struggle is a central part of the writing process. It’s what writers do.

While my students are in the drafting process, I conduct a number of mini-lessons designed to get them to emulate at the sentence level. I give them a group of sentences that all have something in common, and I ask them what they notice. For example, I might give them the following mentor sentences:

“I want to go,” she said, “but I don’t have any money.”

“If you think I am happy,” John yelled, “you are wrong!”

“I bought tickets for the game,” he said, “for I am a huge fan.”

There are a number of things I want my students to notice about these sentences:

• They all contain quotations.

• They all have middle attribution.

• When a quotation is interrupted by middle attribution, it has to be closed before the attribution, and it has to be reopened after the attribution.

• Because the quotation is not completed, the first word after the attribution is not capitalized. (There is an exception to this rule when the first word after the attribution is a proper noun.)

• End marks go inside any closing quotation mark.

• When you have an exclamation point (or a question mark) as an end mark, it takes the place of a period. You do not need both.

I don’t give this list to my students. I have them generate it from paying close attention to the mentor sentences. When students notice the construction behind good sentences, they construct good sentences. So how do I choose the mentor sentences that I want them to emulate? I read their papers and look for patterns of weaknesses. For example, if I notice an overabundance of simple sentences, I will have them study mentor sentences that infuse dependent clauses. Sometimes I select sentences for them to study because they need to learn a specific punctuation rule (e.g., they misplace the commas when using middle attribution quotations). Other times I select sentences to try to amp up the craft of their papers, as I did when I brought them this whopper of a sentence from Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, where the author describes the frenzy of living in the New York City rat race:

People gambled and golfed and planted gardens and traded stocks and had sex and bought new cars and practiced yoga and worked and prayed and redecorated their homes and got worked up over the news and fussed over their children and gossiped about their neighbors and pored over restaurant reviews and supported political candidates and attended the U.S. Open and dined and traveled and distracted themselves with all kinds of gadgets and devices, flooding themselves incessantly with information and texts and communication and entertainment from every direction to try to make themselves forget it: where we were, what we were. (2013, 477)

My students examine the construction of this sentence, discussing how the intentional run-on reinforces the pressures of daily living. They then imitate the sentence as they write about the pressures of school. Here is Shaniah’s sentence:

Students press their alarm clocks and roll out of bed and get ready for school and wait a long time for the train and arrive to school late and get lectured by the attendance lady for their tardiness and read lots of long novels and study SAT vocab and wrestle with chemistry formulas and tackle pre-calculus problems and annotate primary source Civil War documents and work their way through a 6.5 hour day and meet with teachers and have mountains of homework and get report cards and get yelled at by parents and go to study halls and take numerous tests and stress over their grades and sacrifice sleep just to get to this finish line we call graduation.

Language traditionalists may be shocked that I am using a run-on sentence for emulation purposes, but I believe it is okay to break the rules if there is intentional thinking behind breaking the rules (an argument put forth in Edgar Schuster’s [2003] Breaking the Rules). Shaniah’s intent here, of course, is to illustrate the rat race of high school, and breaking the rules adds power to her intent. As Shaniah’s sentence shows, having students emulate mentor sentences is the first step in elevating their writing.

From the mentor sentence level, I first move students to chunks of writing before moving into more developed pieces. I start by having them write 100-word stories, an idea taken from the website www.100wordstory.org. As the title of the website indicates, the stories are exactly 100 words. I write mine first in front of the students, sharing my thinking, adding a bit here and subtracting a bit there to shape it into exactly 100 words:

Sitting on the uptown 3 on my way to school. Different walks of life on the train: Mr. Yankees fan quietly lamenting his team’s elimination from the playoffs. A mom herding her three sleepy kids to school. The homeless man bundled and huddled in the corner. A young couple lost in each other. A teenager, with ear buds in place, singing loudly. A woman lost in playing Candy Crush. A war vet walking through asking the passengers for money. An angry man is glaring at me from across the car. Twenty-three strangers in my subway car. Some coming, some going.

My students then follow. Here is Jocelyn’s draft:

Look in front of you and what do you see? A crush? A dream? What about what you don’t see? The valuable things that are staring back at you, but you don’t notice. The best friend who wants something more. The sister who has always been beside you. The mother who left, but will always love you. We keep our eyes ahead and don’t realize who is standing next to us. In that way, we are all farsighted. We constantly stick our hands out for more but don’t take the time to realize what we already hold in our hands.

From 100-word passages, you might move your students into drafting 100-word poems. I use Neil Gaiman’s “A Hundred Words to Talk of Death” as a mentor text:

A Hundred Words to Talk of Death

By Neil Gaiman

A hundred words to talk of death?

At once too much and not enough.

My plans beyond that final breath

are currently a little rough.

The dying thing comes on so slow:

reluctance to get out of bed

is magnified each day and so

transmuted into dead.

I dream of dying all alone,

nobody there to watch me pass

nothing remains for me to own,

no breath remains to fog the glass.

And when I do put down my pen

My memories will fly like birds.

When I am done, when I am dead,

and finished with my hundred words. (2009)

From practicing 100-word stories and 100-word poems, we transition to emulating other mentor passages, like this one culled from Of Mice and Men, where John Steinbeck describes the men’s living quarters:

The bunk house was a long, rectangular building inside, the walls whitewashed and the floor unpainted. In three walls there were small, square windows, and in the fourth, a solid door with a wooden latch. Against the walls were eight bunks, five of them made up with blankets and the other three showing their burlap ticking. Over each bunk there was nailed an apple box with the opening forward so that it made two shelves for the personal belongings of the occupant of the bunk. And these shelves were loaded with little articles, soap and talcum powder, razors, and those Western magazines ranch men love to read and scoff at and secretly believe. And there were medicines on the shelves, and little vials, combs; and from nails on the box sides, a few neckties. Near one wall there was a black cast-iron stove, its stovepipe going straight up through the ceiling. In the middle of the room stood a big square table littered with playing cards, and around it were grouped boxes for the players to sit on. (1993, 17)

My students then imitate the passage. Here is Eduardo’s description of the subway train he takes to school every morning:

The #6 trains are rectangular cars linked together, making a silver metal sausage, with the decal number 6 on the side rectangular windows of the cars. Inside, the baby blue seats line both sides of the car, above a black and white speckled floor. People sit opposite each other, sleeping, gazing off into space, or silently wondering about the lives and problems of their fellow passengers. Metal poles are strategically placed through the middle of the car, giving standing passengers a place to grab. Above the seats hang advertisements for sleazy lawyers or television shows, many of which are inappropriate for the youngsters on the train. After repeated stops, the car fills, becoming so crowded that the floors and windows are no longer visible.

As the year progresses, I move students into more challenging writing tasks. For the last ten years, for example, my seniors have written historical investigations into the events of September 11. Some of these students have never written a three-page paper, but last year the papers averaged twenty-five pages in length. How did I move my young writers into writing such in-depth pieces? I employed numerous strategies, but perhaps the most effective was allowing them to study exemplary papers from previous years. Holding models in their hands helped them to discover the appropriate voice. It taught them how to properly imbed research. It showed them what a works cited page looks like. Seeing how previous examples were structured was invaluable in enabling them to take on such an arduous writing task. Before they could do it, they had to know what it looked like, and as they were writing, they benefitted greatly from studying models placed at their sides.

Mentor texts help elevate inexperienced writers, of course, but they are also effective in improving the writing of our best young writers. Consider, for example, how you might prepare your students to answer this advanced placement prompt:

A bildungsroman, or coming-of-age novel, recounts the psychological or moral development of its protagonist from youth to maturity, when this character recognizes his or her place in the world. Select a single pivotal moment in the psychological or moral development of the protagonist of a bildungsroman. Then write a well-organized essay that analyzes how that single moment shapes the meaning of the work as a whole. (College Board 2013, 4)

The best AP teachers I know prepare their students for rigorous questions like these by having them analyze previously scored essays. The College Board, who creates these prompts and scores the responses, also understands the importance of models, which is why they post examples of high, middle, and low student essays on their website for teachers and students to study. The College Board knows that even our best writers benefit when they stand next to exemplary writing and analyze what makes it good.

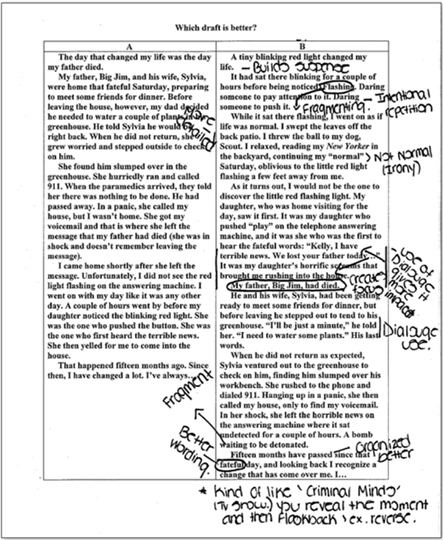

One of my favorite strategies to spur meaningful revision is to have my students compare two different drafts and then ask them which of the two is better. Following are two drafts I wrote about the day I learned my father had died. I gave both drafts to a group of eighth-grade students and asked them to determine which draft is better. I now invite you to do the same. Which one is better, Draft A or Draft B?

DRAFT A |

DRAFT B |

The day that changed my life was the day my father died. My father, Big Jim, and his wife, Sylvia, were home that fateful Saturday, preparing to meet some friends for dinner. Before leaving the house, however, my dad decided he needed to water a couple of plants in his greenhouse. He told Sylvia he would be right back. When he did not return, she grew worried and stepped outside to check on him. She found him slumped over in the greenhouse. She hurriedly ran and called 911. When the paramedics arrived, they told her there was nothing to be done. He had passed away. In a panic, she called my house, but I wasn’t home. She got my voicemail and that is where she left the message that my father had died (she was in shock and doesn’t remember leaving the message). I came home shortly after she left the message. Unfortunately, I did not see the red light flashing on the answering machine. I went on with my day like it was any other day. A couple of hours went by before my daughter noticed the blinking red light. She was the one who pushed the button. She was the one who first heard the terrible news. She then yelled for me to come into the house. That happened fifteen months ago. Since then, I have changed a lot. I’ve always … |

A tiny blinking red light changed my life. It had sat there blinking for a couple of hours before being noticed. Flashing. Daring someone to pay attention to it. Daring someone to push it. While it sat there flashing, I went on as if life was normal. I swept the leaves off the back patio. I threw the ball to my dog, Scout. I relaxed, reading my New Yorker in the backyard, continuing my “normal” Saturday, oblivious to the little red light flashing a few feet away from me. As it turns out, I would not be the one to discover the little red flashing light. My daughter, who was home visiting for the day, saw it first. It was my daughter who pushed “play” on the telephone answering machine, and it was she who was the first to hear the fateful words: “Kelly, I have terrible news. We lost your father today…” It was my daughter’s horrific screams that brought me rushing into the house. My father, Big Jim, had died. He and his wife, Sylvia, had been getting ready to meet some friends for dinner, but before leaving he stepped out to tend to his greenhouse. “I’ll be just a minute,” he told her. “I need to water some plants.” His last words. When he did not return as expected, Sylvia ventured out to the greenhouse to check on him, finding him slumped over his workbench. She rushed to the phone and dialed 911. Hanging up in a panic, she then called my house, only to find my voicemail. In her shock, she left the horrible news on the answering machine where it sat undetected for a couple of hours. A bomb waiting to be detonated. Fifteen months have passed since that fateful day, and looking back I recognize a change that has come over me. I … |

Which one did you pick? Most of my students chose Draft B as the better draft. In Draft A, I wrote the narrative much like a typical student, straightforward, in sequence, and devoid of many of the craft moves we’d want our students to make. (Note the typical student-written introduction: “The day that changed my life was the day my father died.”) In Draft B I revised, infusing many of the craft moves we want students to adopt. (Note how the introduction in Draft B teases the reader: “A tiny blinking red light changed my life.”)

I ask my students which draft they like better, and once they have chosen, I ask them to return to the chosen draft and identify what makes it better. They do this by physically circling the parts that make it a better piece of writing. Once they’ve circled these moves made by the writer, I have students label them. In Figure 6.1, you will see what Grace identified as the parts she felt were better. One (of many) move Grace noted is that the sequence in Draft B was different. As Grace writes at the bottom of her notes, Draft B is “kind of like ‘Criminal Minds’ (TV show.) You reveal the moment and then flashback…” Recognizing this move, Grace immediately went back to her first draft and started experimenting with rearranging its sequence. Other students suggested that the dialogue found in Draft B made it a better piece of writing; many of these same students then returned to their drafts and added dialogue.

The effectiveness of the “Which Draft Is Better?” strategy is not limited to narrative writing. I use it in other contexts, as I did recently when working with students in an eighth-grade history class. They were studying post-Civil War Reconstruction, and the students were given a number of primary source documents outlining the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan. Each student was asked to read through the various documents, to make a claim about the KKK, and to support his or her claim.

Students turned in woefully underdeveloped drafts. Here, for example, is what Lassan wrote (unedited) in his first draft:

The Ku Klux Klan were a group of people who hated Negroes. They lynched, bombed, and burned many blacks. Abram Colby is a perfect example. He was beat for 3 hours in the woods and left for dead. This clearly shows how much the Ku Klux Klan hated blacks.

This is not the introduction to Lassan’s first draft; this is his entire first draft. To help him improve his first draft, I had him undergo the “Which Draft Is Better?” exercise with the following passages (written by me):

Figure 6.1 Grace’s “Which Draft Is Better?” chart

DRAFT B |

|

The Ku Klux Klan were a group of ex-slave owners who did not believe in change or at least free African Americans. They went around burning free African Americans’ houses. In the Abram Colby case, members of the Ku Klux Klan dragged Colby out of his house (in front of his wife and daughter) into the woods and beat him for more than three hours. |

In the Reconstruction Era, the Ku Klux Klan was allowed to gather too much power. One needs to look no farther than the case of Abram Colby to see this abuse of power. Colby, a former slave and member of the Georgia legislature, was beaten savagely in 1869 in an attempt to scare him away from politics. Colby recalls the horrors of the day the Klan came to get him: “The Klansmen broke my door open, took me out of bed, took me to the woods and whipped me three hours or more and left me for dead … they set in and whipped me a thousand licks more, with sticks and straps that had buckles on the end of them.” It is a myth that the Klan was made up of a small group of renegades. How, then, was the Klan able to gather too much power? According to Eric Fomer, “Most of the leaders of the Klan were respectable members of their communities, business leaders, farmers, ministers … it became very clear that they were respectable people, so to speak. And all that comes out in the hearings and trials. It really puts a face on Klan activity, and you see the victimization and the terrible injustice that have been suffered.” And this explains why the Klan was able to gain and keep so much power. Many Klan members were made up of “Southern white aristocrats who had owned slaves for generations.” These leaders believed that black people could not be equal to whites, and since they had the power, they ensured that this injustice continued. African Americans often couldn’t turn to their town leaders for help because often it was their town leaders who were in the Klan. The story of Abram Colby, and others like him, raises some troubling questions: How could the nation stand by and allow the Klan to gain so much power? Why did it take the federal government so long to fight the Klan? Whatever the answers may be, one thing is clear: the KKK was allowed to gain too much power, and they were allowed to keep it too long. |

Lassan read the two drafts, determined that Draft B was better, and identified the moves that I made as a writer. Amongst the moves he noticed, for example, is that Draft B started with a direct claim and that later in the draft a number of primary sources were cited.

Of course there is a danger in modeling the same piece I want the students to do, for they will be inclined to simply copy what I have done. To prevent this, I collected my “Which Draft Is Better?” model from Lassan and his classmates (after they recognized the craft moves), and replaced it with a different model. The new model made many of the same craft moves as the KKK draft, but focused on an entirely different historical event (the events of 9/11):

DRAFT A |

DRAFT B |

On September 11, 2001, nineteen terrorists hijacked four airplanes and flew them into American targets. Two crashed into the World Trade Center in New York, one crashed into the Pentagon in Virginia, and one crashed into a field in Pennsylvania. When it was all said and done, 2,996 Americans lost their lives on that tragic day. |

The events of 9/11 could have been avoided, if only our government had paid more attention to the warning signs. Everyone knows the basics of the day: nineteen terrorists hijacked four airplanes and flew them into American targets. Two crashed into the World Trade Center in New York, one crashed into the Pentagon in Virginia, and one crashed into a field in Pennsylvania. When it was all said and done, 2,996 Americans lost their lives on that tragic day. “The day was avoidable,” says Joe Smith. “The FBI had been warned by one of their agents that a number of suspicious men were taking flight training classes in Florida. He even wrote a report warning his superiors of the plot, but somehow that report was not acted on. The FBI dropped the ball on this one” (Smith 112). It is a myth that … |

It should be noted that Draft B is not historically accurate (I made up the quotation for demonstrative purposes, and I informed my students as such). I simply wanted the students to note that the model started with a straight claim and that citing a primary source supported the claim. Once students recognized these moves, I had them revise the first drafts of their KKK pieces. With the 9/11 example in his hand, note the difference Lassan made between his two drafts:

LASSAN’S DRAFT AFTER THE MODELING |

|

The Ku Klux Klan were a group of people who hated Negroes. They lynched, bombed, and burned many blacks. Abram Colby is a perfect example. He was beat for 3 hours in the woods and left for dead. This clearly shows how much the Ku Klux Klan hated blacks. |

During the Reconstruction Era, the Ku Klux Klan wanted power. Violence became the way they gained this power. The Ku Klux Klan, also known as the Klan or the “Hooded Order,” was a group who directed hatred towards blacks. They often beat blacks to show their power. This terrorist organization in the United States tried to get white supremacy and hatred towards blacks legalized. Abram Colby, a famous victim, is a perfect example of pain the Klan caused: “On the 29th of October, 1869,” Colby stated, “they broke my door open, took me out of the bed and whipped me for three hours … they said to me, ‘Do you think you will ever vote for another damned Radical Ticket?’” It is crazy that the Klan could almost kill another human being because of who he voted for. The KKK were clearly heartless attackers who would do whatever it took to maintain their power and to keep blacks down. They tried to control the vote by beating people who would not vote in their favor. Some people argued back then that the KKK did not have bad intentions. If that is true, why did they base their entire organization on public violence against blacks as intimidation? How do you explain former confederate Brigadier General George Gordon, who developed a dogma that said the world should be based off the white man’s beliefs? He believed the world should follow a “white man’s government.” KKK members during Reconstruction were often rich men from the South. They had no real reason to hate the blacks, unless there was a personal issue. So, why the hatred toward blacks? Why did they burn black churches and schools without a legitimate reason? Why did our government stand by when this was happening, why didn’t it get more involved? Will this organization gain power again and start another era of hatred towards blacks? Anything may occur, but one thing is known: the KKK used violence to gain power in the Reconstruction Era. |

Lassan’s second draft is certainly not polished—it still needs a lot of work—but his revised version starts with a much clearer claim, it has much more detail, it is supported by two primary sources, it has a recognizable conclusion, and it contains other craft moves taken from the 9/11 model (for example, he uses a series of rhetorical questions).

In both of these examples—the writing of a narrative in an English class and the writing of an analysis about the emergence of the KKK in a history class—the students’ writing was elevated through their ability to read closely.

The ability to read like a writer also proved beneficial to Yolanda, an inexperienced seventh-grade writer, who in her English class was drafting a narrative about being stood up by a boy at a dance. After comparing two mentor drafts, she changed her introduction:

YOLANDA’S FIRST-DRAFT INTRODUCTION |

YOLANDA’S SECOND-DRAFT INTRODUCTION |

I was in summer camp and there was a dance that was happening tomorrow night. I decided to ask my first crush, who was Australian. His name was Vincent and we were friends since the second day of camp. |

Where is Vincent? Did he forget? Did he change his mind? Standing alone in a ravishing dress, I am shocked, feeling a heat wave come across my face. Where is that boy? |

When I conferred with Yolanda, I told her that I really liked her line, “Where is that boy?” She responded with a confession. She said, “I stole it from a book called That Boy by Jillian Dodd (2012). I read it in a scene where two people were trying to find each other in a crowded restaurant. I liked it.”

The work of the students shared in this chapter reminds us that the act of reading well leads to the act of writing well.

Thus far I have described the importance of modeling in building young writers. Let’s now turn our attention to the value modeling holds when building young readers. The modeling I provide in hopes of making my students better readers springs from one simple question: What do I want my students to be able to do as readers? In short, I want my students to do these things:

Read for enjoyment

Read widely

Know what readers do when they are confused

Track their thinking over the course of a book

Be able to read between the lines—to infer

Be able to meaningfully discuss their reading

Think about their reading via writing

Develop agency as readers, thus reducing their dependence on the teacher

Consider their reading in the context of their worlds

Let’s look at each of these goals, taking a moment to consider how modeling helps students achieve them.

Since the Common Core anchor reading standards virtually ignore recreational reading, I am concerned that students will lose opportunities to read for enjoyment. And students who are not given a chance to read for enjoyment are much more likely to become adults who do not read for enjoyment. Don Holdoway, the respected New Zealand educator and father of shared reading, once noted in a talk at a conference that there is a lot of “criminal print starvation” going on in our schools. Holdoway’s comment reminds us that Priority 1 is to make sure our students have ample opportunities to read good books, and to ensure that this happens, I strongly suggest beginning with three steps:

1. Build an extensive classroom library.

2. Build an extensive classroom library.

3. Build an extensive classroom library.

I can’t model that reading is fun unless my students are surrounded by books that are fun to read. I want most of the reading my students do this year to be self-selected and high interest in nature (more about this in Chapter 8), and access to lots of good books is where achieving this goal starts.

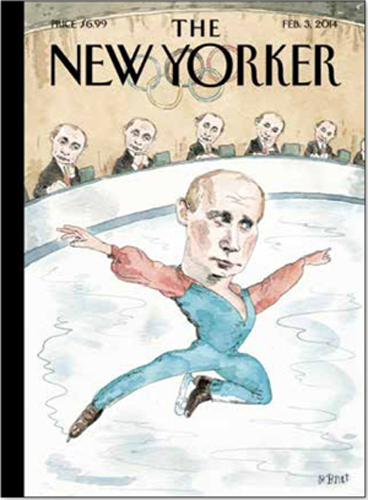

You have to know stuff to read stuff. To demonstrate this to my students, I bring in covers from the New Yorker and ask them if they can explain the covers to me. Most cannot do so. Take the cover shown in Figure 6.2, for example. To understand this cover, a reader would have to know all of the following:

• The winter Olympic games were held in Russia.

• Vladimir Putin is the president of Russia.

• The government of Russia is homophobic.

• Russia’s homophobia stirred a lot of controversy.

• Male figure skaters are often stereotypically associated with being gay.

Figure 6.2 The New Yorker’s satirical take on the Sochi Olympics

That is a lot to bring to the page before the reader can reach understanding (and this is before the magazine is even opened). If the reader comes to this cover not knowing who Putin is, or not knowing that Russia had passed antigay laws, it doesn’t matter what reading strategies he or she possesses. The game is already over. Rereading, or visualizing, or slowing the reading pace will not help. Reading is more than simply having the right reading tools on the reader’s tool belt. Readers have to know stuff to read stuff.

Which brings me back to a seventh-grade reading class I was working in last year, where I was struck by the barrenness of the students’ background knowledge. While conferring with a student, for example, I was asked if China was part of the United States. In the very next conference, a different student asked me if I knew the name of the president of Utah. (These questions came from middle school students, mind you.) Recognizing that these students needed to immediately broaden their reading, we set aside a day each week for students to read Upfront magazine, a weekly current events magazine jointly published by Scholastic and the New York Times. Upfront is an excellent tool to help students broaden their knowledge of the world. It helps students learn about what is happening in the world, which, in turn, deepens their ability to read widely. If we don’t build prior knowledge, deeper reading will not occur. (Information about Upfront can be found at http://www.upfront.scholastic.com.)

Beyond Upfront, I model to my students that wide reading is important by reading widely myself and by consistently sharing what I am reading with my classes. Every day, I begin each class period by reading something to my students—a poem, a newspaper article, a blog, a passage from a novel or a work of nonfiction—something to show my students the value and the fun that comes from reading widely. I also build in time so that my students can share what they are reading with one another.

When reading gets hard, experienced readers become active. The first thing they do is monitor exactly where the confusion arises (you can’t fix your comprehension unless you are aware of the exact spot where it falters). Once they identify the confusion, readers apply strategies in an attempt to make meaning. (For an extensive list of what readers do to make sense of confusion, see pages 104–105 of Readicide [Gallagher 2009]). I want my students to adopt these moves, but for that to happen, I—the teacher—have to model them.

I also want my students to know that applying tools to their confusion doesn’t always remedy the problem. There are times as readers in which we have to live with ambiguity. When experienced readers get confused—especially early in a novel—they recognize that the confusion is normal and that, often, one has to embrace and hold on to that confusion until it begins to clear. Anyone who has ever watched a Terrence Malick film understands this point.

The best way, of course, to teach my students how to handle the confusion encountered while reading is to model how I handle confusion when I read. To achieve this, I do a lot of read-aloud/think-alouds in front of my students, sharing with them what I do to make sense of the hard parts.

Sometimes we focus so intently on getting students to demonstrate that they can read a passage closely that we forget the bigger picture of teaching students how to track their thinking over the course of a book. Not only do I want my students to be able to track their thinking throughout a book, but also I want them to note how their thinking may shift over time. What you think in the beginning of the book may be different from what you think in the middle of the book, and what you think in the middle of the book may be different from what you think at the end of the book. (For example, the view my students have of Prince Hamlet at the end of the play is often very different from the impression they originally formed of him in act 1.) As my colleague Donna Santman (personal communication) notes, at the beginning of a novel students’ thinking will be grounded in a lot of exposition—Who is who? Where are we? What is happening? By the middle of the book, Santman suggests, the students, thinking shifts toward the conflicts that arise—Who is doing what to whom? Why is that character acting that way? Why is this happening? At the end of the book the thinking shifts again toward resolution and big ideas—Why did the book end this way? What is the author trying to say? What big ideas are hiding in this book?

To help students think about their thinking while they read, Santman has developed the following sentence stems:

• I started by thinking_________________and as I read I added/learned_________________.

• I used to think_________________, but now I think_________________.

• Some people think_________________, but I think_________________.

These sentence starters prompt students to track their thinking as they read across chapters. To help students capture their thinking, I give them composition books with unlined paper. I give them unlined paper to send the message that there are a number of ways they can capture their thinking: they can write, draw, make T-charts, create graphs, post sticky notes and then comment on them—anything that demonstrates that they are actively thinking as they read. I do not tell them how much they need to write or how many entries they must produce. I let them decide. I do tell them that if they overannotate they will kill the book, and that if they underannotate they will not get to levels of deeper reading.

I don’t ask my students simply to track their thinking over the course of reading their books; I ask them to do so with the intention of discovering one of the author’s big ideas. There are two important points to consider here: (1) I am careful not to establish the big idea for my students to consider; I want them to determine the possibilities. (2) I want them to recognize that in any rich book there are numerous big ideas to consider, and that no book is driven by one theme. It could be argued, for example, that the big idea in To Kill a Mockingbird is “It takes courage to stand up to racism.” But it could also be argued that one of the following is the big idea:

Because you can’t win doesn’t mean you shouldn’t fight.

You never really understand a person until you stand in his or her shoes.

One person can make a difference.

Heroism is often quiet.

Schools often get in the way of a good education.

Parenting is the most important job in the world.

Some people can be judged at first sight; others can’t.

Education provides the ladder out of poverty.

Because something is legal doesn’t make it moral.

Coming of age involves innocence being lost.

Or there might be other big ideas that I have yet to consider. Because there are many big ideas in a given book, it is counterproductive for the teacher to establish the big idea. Doing so denies students the opportunity to hone their own thinking.

There is another benefit to having students find their own big ideas: It drives more meaningful annotation while they read. When students annotate with the purpose of discovering a big idea in the book, it drives a richer reading of the text. It encourages them to consider how they came to their big idea, and it prompts them to pay attention to what the author did to establish the theme. Instead of isolated or “one and done” annotation (e.g., “This reminds me of my grandmother…”), tracing an idea across a book requires a deeper level of reflection. This kind of annotation is very different than blind, unattached “drive by” annotation, where students are asked to generically annotate whatever comes to mind without any thought to the larger picture.

So I hear the question resonating in many of your minds at this moment: How do I grade my students’ thinking? For accountability purposes, I confer with each student three times—once at the one-third point in the book, once at the two-thirds point in the book, and once at the end of the book. We sit down together each of these times to consider the level of thinking the student is doing. I score each student’s thinking in two ways: through the work found in the notebook and through the discussion that occurs while we confer. I don’t have a rubric. I don’t have a checklist. We simply talk and look through the notebook together, and then I make a professional judgment. If the student disagrees, I ask for a defense of the disagreement. Sometimes negotiation occurs. And, as always, when I find excellent work, I bring it up for the entire class to see. It is the sharing of excellent student work that provides my students with the rich models needed to understand how to meaningfully track thinking across a book.

In Deeper Reading, I argue that our students’ ability to infer is sharpened when we teach them to consider what is not said in the text (Gallagher 2004). Here are a few more inference activities I have brought to my classroom since the writing of that book.

Every January, National Geographic publishes the most memorable photographs of the previous year. Figure 6.3 shows one taken by Sue Ogrocki. I start by showing students the photo and asking them to read the photograph carefully and consider what might have happened. Most of them correctly infer that some sort of natural disaster (tornado? earthquake?) has occurred. Others guess that it depicts a war zone. (The natural disaster inference is correct—this photo was taken near the collapsed Plaza Towers Elementary School in Moore, Oklahoma, after a massive tornado struck the Oklahoma City suburbs in 2013.) After I tell the students what the photo actually shows, I ask them what else the photograph suggests. In other words, what does the photograph imply? Here are some of their responses:

• There may not have been an adequate warning system.

• Maybe it happened in the morning while people were sleeping.

• There are no emergency responders in the photo. Maybe the devastation is so widespread that these people were left on their own.

• Some victims may have survived and might have needed to be rescued.

• The dead will have to be recovered.

• The survivors will need a place to sleep.

• They will need food and water.

• The children who survived will have to attend a different school.

Figure 6.3 Inferring from photographs: Moore, Oklahoma, May 20, 2013

After we work with photographs, I have students apply the same inference skills while reading paintings. I start with Ralph Fasanella’s Lawrence 1912–The Bread and Roses Strike (see Figure 6.4). I do not share the title of the painting with my students beforehand because I do not want to influence their “reading” of it. Students are asked to infer what might be happening in the scene. This painting depicts a massive strike of textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, which at the time was one of the most important textile manufacturing towns in the United States. The strike led to violence (notice the striker in the painting being trampled by the horse) before eventually being settled a year later. Though I certainly do not expect my students to possess specific background knowledge regarding the Bread and Roses Strike, it is always interesting to see how much they can infer from the painting.

Figure 6.4 Ralph Fasanella’s Lawrence 1912—The Bread and Roses Strike

Take a page from a comic book and white out the bubbles where the characters’ speech is written. Have the students fill in the dialogue, predicting what is said based only on the graphics. Once they make their predictions, show them the original dialogue. I choose a student whose created dialogue comes very close to the original, and I have this student share his or her inferential thinking with the class.

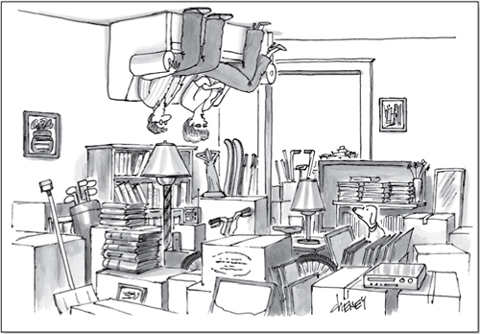

The last page of each issue of the New Yorker includes a cartoon caption contest. The magazine editors select a cartoon and publish it without the caption. Readers then write in and supply possible captions. Figure 6.5 shows a recent example without the caption. Students write their own humorous captions, which are then compared to the three finalists (following) chosen by the magazine editors.

Figure 6.5 Creating cartoon captions from the New Yorker

1. “Let’s flip this house.”

2. “I told you to tip the movers.”

3. “We’re not really utilizing our wall space.”

Wrestling with Sandy Silverthorne and John Warner’s One Minute Mysteries (http://www.oneminutemysteries.com) also develops my students’ inference skills. Here is one example, titled “Lunch Time”:

Robbie goes into a restaurant and orders a deli sandwich and a cola for lunch. Afterward, he pays his bill, tips his waitress, and goes outside. He slowly takes in his surroundings. The sky is black and the city streets are deserted. What happened? (2007, 12)

Using inference skills, the students have to come up with a plausible answer. (In this example, the man worked the night shift and took his lunch break in the middle of the night.) Having students wrestle with one-minute mysteries helps to sharpen their inference skills.

I want my students to apply inference skills to the novels they are reading. I might start with a passage like this one, which appears on the first page of Laurie Halse Anderson’s Chains:

Pastor Weeks sat at the front of the squeaky wagon with Old Ben next to him, the mules’ reins loose in his hands. The pine coffin that held Miss Mary Finch—wearing her best dress, with her hair washed clean and combed—bounced in the back when the wagon wheels hit a rut. My sister, Ruth, sat next to the coffin. Ruth was too big to carry, plus the pastor knew about her peculiar manner of being, so it was the wagon for her and the road for me. (2008, 3)

After a close read, my students came up with the following inferences:

• This takes place in a rural area.

• This story takes place in the “old days.”

• Old Ben is a dog.

• Mary Finch died young.

• Ruth might have special needs.

• The narrator might be related to Miss Mary Finch—maybe a sister?

The beginning of a novel—where it pays to notice how characters are introduced—is an excellent place to practice inferential skills. I often have students infer from a book’s opening paragraph.

Once students move past the exposition, I sharpen their inference skills by having them predict what might happen next. Anyone can make a prediction, but I have my students cite textual evidence that lends credence to their predictions. What have you inferred, I ask, that leads you to that prediction? Later, I might have them return to their predictions and reflect where their inferences were strong and where they were weak.

In every one of these examples—how to infer from a photo, a painting, a comic book, a cartoon, a one-minute mystery, a novel—I always begin by modeling my thinking. For example, if I want my students to make inferences from reading Painting A, I model the kind of thinking I am looking for by sharing my inferential thinking about Painting B. When teaching inference, I go, and then they go.

Thus far I have discussed how I want my readers to do these things:

Read for enjoyment

Read widely

Know what readers do when they are confused

Track their thinking over the course of a book

Be able to read between the lines—to infer

But as I stated earlier in the chapter, I also want them to be able to do these things:

Be able to meaningfully discuss their reading

Think about their reading via writing

Develop agency as readers, thus reducing their dependence on the teacher

Consider their reading in the context of their worlds

Let’s look at how I work on each of these in the classroom.

When meaningful talk happens around books, everyone gets smarter. The key word here, of course, is “meaningful.” Because talk is central to deepening my students’ thinking, I build a lot of opportunity for students to talk into every day’s lesson. My students frequently interact verbally through partner talks, group discussions, and whole-class discussions (ranging from wide-open exchanges to Socratic seminars), and I work hard to make sure that through these discussions it is my students who are generating the thinking.

This is the opposite approach to what I found in a classroom I visited last year—a seventh-grade classroom where the students were reading Lois Lowry’s The Giver. To sharpen the students’ reading, the teacher had determined that the theme of the novel centered on the idea of the dangers of oppression. The students were told this before the reading commenced and all their annotation of the novel centered on finding evidence of oppression. Every time the students met in groups to discuss the novel, their discussions centered on how Lowry developed the notion of oppression. When they finished the novel, they were given an essay question asking how oppression played a role as the central theme, which they were able to answer dutifully (since they had read the entire book and taken notes through this lens).

The problem with this approach is that much of the thinking was done for the students, and it was done for them before they even read the first page of the novel. By determining the central theme to be studied, the teacher denied students the chance to make their own meaning. Who is to say, for example, that the theme chosen by the teacher is the definitive theme? Someone else might argue that Lowry’s book is really about the importance of individuality. Or that the book is a commentary on the value of our memories. All rich books have several themes. When a teacher predetermines “the” theme, the teacher also predetermines the students’ thinking.

So what do I mean when I say I want students to generate their own thinking? Let’s return to The Giver, for example. Before reading the novel, I would have told my students that there were several large ideas imbedded in the text and that their job as they read would be to identify one or more of them and to track the development of the ideas. After reading a few chapters, I would schedule a day for the class to revisit their reading. Instead of assigning a theme to track, I might put them in small groups and ask them, “What’s worth talking about in this chapter? What big ideas are beginning to emerge?” After they had a chance to explore their thinking, I would then open up the discussion for the entire class to participate. This approach is a different approach than the one often taken in a traditional classroom, where the teacher has prepared a list of questions for the students to answer—a list of questions designed to lead the students to adopt the teacher’s interpretation of the novel. This is not to say, of course, that I, as the teacher, do not have anything valuable to contribute to the conversation. But I am careful to have the discussion start with what the students are thinking. If, over the course of their discussion, I think they have missed a big idea, I can throw a question into the mix to get them to begin thinking in that direction. But the point here is that the conversation starts with what the students are thinking, and it is my students—through lots of talking—who determine which big ideas are worth tracking and discussing.

Student-centered talk is crucial. If the teacher is the only one talking in the room, the students will never get to the deepest level of thinking. In Chapter 7, I explore additional strategies for strengthening our students’ speaking and listening skills.

As I demonstrated earlier in this chapter in the discussion about using mentor sentences, one of the best ways to develop young writers is to have them carefully emulate the craft of established writers. This emulation occurs through careful reading of excellent writing. Reading makes us better writers. Conversely, let us not forget that the opposite is also true: Writing makes us better readers. The act of writing deepens our comprehension.

To illustrate this, let’s return to the teaching of The Giver. Let’s say students have read the first few chapters, and I am getting ready to ask them the following: “What’s worth talking about in this chapter? What big ideas are beginning to emerge?” Before I allow students to discuss this, I have them explore their thinking by writing for five minutes. At the end of the quick-write, I place them in small groups and have them silently pass their papers to the next person. Each person in the group reads someone else’s thinking, and then responds silently in writing. The students continue to pass the papers every five minutes, until every student has read and responded to multiple perspectives. This written silent conversation always generates new thinking for my students, and it primes the pump for the ensuing small-group and/or whole-class discussion.

I use this strategy often, mixing in different questions to spur the thinking. Last year, for example, students came to class having just read the section in Of Mice and Men where Steinbeck introduces the character of Crooks. I put students into groups and asked the following: “Why do you think Steinbeck introduced the character of Crooks? What is his purpose for doing so?” Students wrote silently and then passed their papers several times. This writing led them to a rich discussion—a discussion that deepened their comprehension of the novel and motivated them to continue to read. For more on how to deepen students’ reading comprehension through writing, I recommend Harvey and Elaine Daniels’s The Best Kept Teaching Secret: How Written Conversations Engage Kids, Activate Learning, and Grow Fluent Writers, K-12 (2013).

The goal in every ELA classroom should be to help students develop agency as readers—students who take ownership of their reading without being constantly prodded by the teacher. To accomplish this, our classrooms must move away from the all-or-nothing reading approach adopted in many schools—classrooms where books are either subject to hyperattentiveness (and thus killed) or books that are simply assigned with little or no attention to the readers’ journeys. Instead, to develop agency, our students would be better served if we created what Judy Wallis, a veteran teacher in Houston, refers to as a “three-text” classroom: a place where students encounter texts we all read, where students encounter texts that some of us read, and where students encounter texts that they read independently. Our students need a blended reading experience, and in Chapter 8 I discuss a model for developing this kind of a classroom.

I want my students to take the wisdom they encounter in the books they are reading and apply that wisdom to the world they will soon inherit. I want them to move beyond the ability to recognize theme or foreshadowing, and to consider how reading books makes them wiser as they approach adulthood. I am much less interested in their ability to answer a question like, “How does the author use personification?” than I am in their ability to answer a question like, “What lessons does The Great Gatsby teach the modern reader?” If we don’t use the books as springboards to help our students think about the world today, then our students are simply reading stories. And though they may be great stories, they have much more to offer young readers than sharpening their ability to recognize literary elements. Students need to stretch their thinking beyond the four corners of the text.

If we want our students to make connections between the books they are reading and the modern world, we need to design lessons that ask students to make those connections. Students who have read 1984, for example, should be prompted to think about when and where our world remains Orwellian. Of course, I might begin the unit by modeling some of these connections to my students (for example, I might bring in editorials or political cartoons that refer to Big Brother), but eventually I want my students to be able to go out in the world and find connections on their own. If a book is worthy of whole-class instruction, it should enable students to make deep connections to today’s world.

Like the up-and-coming baseball players who mimic the mannerisms and techniques of their idols, developing readers and writers benefit from being able to see, analyze, and emulate the strategies and approaches of great readers and writers. With this in mind, let’s make sure we provide our students with plenty of opportunities to stand next to worthy models of reading and writing. Doing so will help them—consciously and unconsciously—deepen their reading and writing abilities. Amongst all the noise currently surrounding the new standards and testing, let’s not forget that building better readers and writers often begins with finding good models for our students to emulate.