In Chapter 4 we focused on what the Common Core writing anchor standards get right. Let’s now turn our attention to what they get wrong. Specifically, when it comes to the teaching of writing, the new standards have five key shortcomings.

David Coleman, one of the authors of the CCSS, argued in his now infamous speech, that narrative writing should be deemphasized:

Do you know the two most popular forms of writing in the American high school today? … It is either the exposition of a personal opinion or the presentation of a personal matter. The only problem, forgive me for saying this so bluntly, the only problem with these two forms of writing is as you grow up in this world you realize people don’t really give a shit about what you feel or think. What they instead care about is can you make an argument with evidence, is there something verifiable behind what you’re saying or what you think or feel that you can demonstrate to me. It is a rare working environment that someone says, “Johnson, I need a market analysis by Friday but before that I need a compelling account of your childhood.” (Coleman 2011, 10)

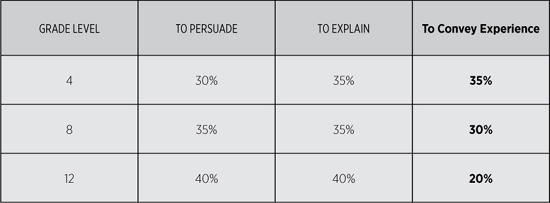

And true to his word, Coleman and the other writers of the standards have gradually deemphasized narrative writing as students move through the K-12 system. This de-emphasis emanates from the 2011 NAEP Writing Framework, which recommended that the breakdown of student writing be as follows (NGA/CCSSO 2010e, 5):

Consistent with these NAEP recommendations, the Common Core Standards for Language Arts now call for an “overwhelming focus of writing throughout high school to be on arguments and informative/explanatory texts” and that the distribution of writing purposes across grades “should adhere to those outlined by NAEP” (NGA/CCSSO 2010e, 5). This de-emphasis on narrative writing is a mistake. The best teachers, doctors, lawyers, salespersons, managers, nurses, CEOs, taxi drivers, scientists, football coaches, and politicians have one thing in common: the ability to connect with people through storytelling. Being able to tell a good story is not a school skill, it is a life skill, and as such, it should be given greater, not less, emphasis. If we want our students to be good storytellers, they need to read and write more narratives.

It turns out that reading and writing narrative texts is very good for you. Here are some reasons our students should be doing a lot more reading and writing of narrative texts.

In Chapter 3 I discussed Judith Langer’s notion that there is a unique kind of thinking that is developed when people read rich, literary works—a kind of thinking that is different than the thinking that is generated when one reads expository text. Langer (1995) argues that literary thinking is an important cognitive piece in the development of deeper thinkers. The CCSS’s de-emphasis on narrative reading and writing (and, conversely, its increased emphasis on expository reading and writing) will move our students away from developing the unique thinking that is generated by reading rich literature and poetry.

An area of psychology that has been given a lot of attention of late is the concept of “theory of mind,” or ToM (Sapolsky 2013). This area of research examines a person’s ability to understand the emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and intentions of others. Developmental psychologists, in trying to figure out when ToM is developed, might ask young children to consider the following story:

Every day, Sally puts her beloved toy rabbit Stuffy on her pillow before going to preschool. One day, after Sally leaves for school, her father notices that Stuffy is quite dirty and puts him in the washing machine. He intends to then put him in the dryer, but forgets. When Sally returns from school that day, she wants to tell her friend Stuffy about her day. Where would she expect to find him? (Sapolsky 2013)

A child who “has not yet developed the skills of theory of mind will answer, ‘In the washing machine.’ The child knows where Stuffy is from having heard the story, and so assumes that Sally must know this too. Only when a child has developed the intuitive ability to put herself in another’s shoes can she recognize that Sally would not know about the laundering, because it happened after she left for school, and so would look for Stuffy on her bed” (Sapolsky 2013).

Why are psychologists so interested in how children develop ToM? Because there is strong evidence that the development of ToM is a precursor for building empathy. The relevance of this for English teachers begins to emerge when you consider a series of experiments conducted by David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano (2013). Kidd and Castano began by looking at the effects that reading has in building one’s empathy. More specifically, they were interested in whether different kinds of reading had equal effect on ToM, so they conducted experiments where participants were divided into groups and assigned to read in one of the following areas: literary fiction, popular fiction, or nonfiction reading. Their findings? Participants who read a lot of literary fiction performed significantly better on the ToM tests than did those assigned to read in the other experimental reading groups.

It should also be noted Kidd and Castano’s studies found that it wasn’t simply the reading of any fiction that fostered ToM; it was the reading of literary fiction. “Literary fiction” in this case is defined as recent National Book Award finalists or winners of the PEN/O’Henry awards. In other words, the participants who did the best on the ToM tests were those who were immersed in “heavy,” high-quality literature. Not surprisingly, literary fiction was found to be more “writerly” and was “more likely to challenge the reader’s expectations, to contain many voices and perspectives” (Sapolsky 2013). As Kidd and Castano note, “The worlds of literary fiction are replete with complicated individuals whose inner lives are rarely easily discerned but warrant exploration” (Perry 2013).

In addition, the readers of literary fiction did significantly better than participants who read popular fiction (selected from Amazon.com best sellers), and they also did significantly better than the participants who read nonfiction (works selected from Smithsonian magazine). Reading literary fiction, it turns out, “may be the equivalent of aerobic exercise for the parts of your brain most involved in the theory-of-mind skills” (Sapolsky 2013). This is good news for those of us who still believe in teaching the classics. Not only do our students gain cultural literacy when they read noteworthy books, but the evidence suggests that they are also building the capacity to have empathy for others.

Beyond developing ToM, reading narrative texts has another benefit: it can change a young reader’s social skills. In his study “In the Minds of Others,” Keith Oatley, professor emeritus of cognitive psychology at the University of Toronto, notes that recent research has found

that far from being a means to escape the social world, reading stories can actually improve your social skills by helping you better understand other human beings. The process of entering imagined worlds of fiction builds empathy and improves your ability to take another person’s point of view. It can even change your personality. The seemingly solitary act of holing up with a book, then, is actually an exercise in human interaction. It can hone your social brain, so that when you put your book down you may be better prepared for camaraderie, collaboration, even love. (2011, 1)

Oatley’s studies dispel the stereotype that people who read a lot of fiction are isolated bookworms. In fact, he found the opposite: Readers of fiction were “less socially isolated and had more social support than people who were largely nonfiction readers” (Oatley 2011, 3). Oatley found that the reading of fiction facilitated the development of social skills because it provides the reader with the experience of thinking about other people. He notes that the “defining characteristic of fiction is not that it is made up but that it is about human, or humanlike, beings and their intentions and interactions. Reading fiction trains people in this domain, just as reading nonfiction books about, say, genetics or history builds expertise in those subject areas” (2011, 3).

In summary, Oatley (2011) found the following:

• The solitary act of holing up with a book is actually an exercise in human interaction (5).

• We internalize what a character experiences by mirroring those feelings and actions (5).

• Reading stories can fine-tune your social skills by helping you better understand other human beings (6).

• Entering imagined worlds builds empathy and improves your ability to take another person’s point of view (6).

• Reading narrative may gradually alter your personality—in some cases, making you more open (6).

• Reading stories exposes readers to new experiences and helps them to become more socially aware (6).

Neil Gaiman, author of short fiction, novels, comic books, graphic novels, audio theater, and films, echoes this sentiment. When you read narrative, Gaiman argues, you recognize what happens to other people. Gaiman notes that prose fiction is “something you build up from 26 letters and a handful of punctuation marks, and you, and you alone, using your imagination, create a world and people it and look out through other eyes” (2013). When you read fiction, Gaiman adds, “You get to feel things, visit places and worlds you would never otherwise know. You learn that everyone else out there is a me, as well. You’re being someone else, and when you return to your own world, you’re going to be slightly changed” (2013). Both Oatley’s and Gaiman’s work bring me back to Judith Langer, who found that “stories provide us with ways not only to see ourselves, but also to re-create ourselves” (1995, 5).

The studies mentioned in this chapter—by Langer, by Kidd and Castano, and by Oatley—all illuminate the importance and value gained by reading narrative. So why am I sharing them in a chapter that argues students should be writing more narrative? Because to write narratives well, students first need to read and emulate strong narratives, and I can’t help but believe that the mental processes that are fostered when students read narrative are in line with the mental processes students develop when they write narratives. As Time humorist Joel Stein writes,

When I want my writing to improve, I read something that forces me to think about words differently: a novel, a poem, a George W. Bush speech. Sure, some nonfiction is beautifully written, and none of Jack London’s novels are, but no nonfiction writer can teach you how to use language like William Faulkner or James Joyce can. Fiction also teaches you how to tell a story, which is how we express and remember nearly everything. If you can’t tell a story, you will never, ever get people to wire you the funds you need to pay the fees to get your Nigerian inheritance out of the bank. (2012)

The Nigerian inheritance reference aside, it is helpful to remind ourselves that the CCSS define narrative as “real or imagined,” and when students write their way into imaginary worlds, surely they benefit from giving careful consideration to the decisions, the relationships, and the actions of others.

When students are reading and writing narratives, they are in the process of re-creating themselves.

The good news is that the CCSS focus on three important writing genres: narrative, inform and explain, and argument. The bad news is that the CCSS focus on only three important writing genres. Beyond the walls of school—in the real world—other types of writing occur. Sometimes, for example, I might sit down to write a proper thank-you note to a friend. Or I might write to an apartment owner to inquire about a property. Or I might write to help me flesh out an inchoate thought. Or I might write as a means to process events that are happening in my life. And sometimes I have no defined purpose when I sit down to write, trusting that the act of writing itself will lead me to discover my purpose.

The kinds of writing we want our students to develop do not always fit neatly under the umbrella of the three big writing types pushed by the CCSS, and my concern is that teachers will become so laser- focused on teaching the “big three” types (since these will be the only three types tested) that the other types of writing—the types we utilize in the real world—will be ignored. Since the CCSS only value part of our writers’ potential, I worry that only part of our students’ writing potential will be developed.

Jamming young writers into these three narrowly defined writing boxes is limiting. We need to make sure our students get lots of practice through and beyond the Common Core anchor writing standards. You wouldn’t limit an aspiring architect by asking her to strictly adhere to only three standardized building blueprints, would you?

As I write this paragraph, I am a new resident of New York City, and when I moved to this neighborhood, I needed to find someone to cut my hair. To figure out where I might go, I surfed Yelp, where I came across reviews of a local hair salon, Salon Above. Here is what Linda O. thinks of this salon:

I’ve been seeing Desi for more than 6 years now. She’s been with me through thick and thin—literally! After losing quite a bit of weight, quite a bit of my hair fell out, but she kept me looking great through it all.

The space is lovely—so tastefully decorated by the owner, Frank—and is always a calm retreat, located a floor above street level. I am always delighted to be offered a drink when I arrive and a chocolate when I leave.

Desi is a gifted stylist who always helps me to look fabulous. She is supported by many other excellent hairstylists as well. But don’t take my word for it—go in for a cut!

Reread this post and ask yourself: Which discourse does this piece of writing fall under? Is it narrative? Is it informative? Is it argument? The answer? Yes, yes, and yes. It has elements of narrative (“I’ve been seeing Desi for more than 6 years now … quite a bit of my hair fell out”). It has elements of inform and explain (“The space is lovely—so tastefully decorated by the owner, Frank—and is always a calm retreat, located a floor above street level”). And it has elements of argument (“But don’t take my word for it—go in for a cut!”). This piece is not narrative. It is not informative. It is not an argument. It is all three.

In the real world, writing is not artificially separated into specific discourses. It is blended for effect. In teaching this idea to my students, I often start with the annual State of the Union address. In 2013, for example, President Obama was appealing to the nation to strengthen gun laws in the wake of the school shootings in Newtown, Connecticut. In making his point, the president shared the following story:

Because in the two months since Newtown, more than a thousand birthdays, graduations, anniversaries have been stolen from our lives by a bullet from a gun—more than a thousand.

One of those we lost was a young girl named Hadiya Pendleton. She was 15 years old. She loved Fig Newtons and lip gloss. She was a majorette. She was so good to her friends they all thought they were her best friend. Just three weeks ago, she was here, in Washington, with her classmates, performing for her country at my inauguration. And a week later, she was shot and killed in a Chicago park after school, just a mile away from my house.

Hadiya’s parents, Nate and Cleo, are in this chamber tonight, along with more than two dozen Americans whose lives have been torn apart by gun violence. They deserve a vote. They deserve a vote. Gabby Giffords deserves a vote. The families of Newtown deserve a vote. The families of Aurora deserve a vote. The families of Oak Creek and Tucson and Blacksburg, and the countless other communities ripped open by gun violence—they deserve a simple vote. They deserve a simple vote. (Obama 2013)

The president could have simply made an appeal to the American people to support his call to strengthen gun laws. He could have said something direct, something like, “We are becoming increasingly a violent society and it is the time to take a hard look at some of our gun laws.” Instead, he chose to weave the Hadiya Pendleton story into his argument. Why? Because telling Hadiya’s story makes the president’s point real, and this realness connects to readers (or, in this case, listeners). It lends poignancy to his argument.

Using narrative to strengthen argument is not a strategy used exclusively by Democrats; it is a favorite technique used by both parties. Look at any president’s State-of-the-Union address and you will find places where narrative has been woven into the president’s argument. Why do both parties employ this strategy? Because it makes their arguments more effective.

One of the problems I encounter when I have students write argument papers is that they often begin writing without knowing much about the argument. Yes, they know a little bit about their side of the argument, but they rarely show evidence of deep consideration of the opposing argument. Without my guidance, they churn out shallow “X is bad and here are three reasons why” essays. To illustrate how I move my students beyond these types of papers, let me walk you through a unit where my students wrote various arguments under the umbrella topic of immigration. As you read, you will see how my students strengthened their arguments by blending narratives into them.

To prepare students, I had them read a lot about the current immigration debate. They read the president’s proposal. They read the opposition’s criticisms and counterproposals. They read arguments posted on both sides of the debate on ProCon.org (a good site for researching arguments). In short, they swam in the immigration debate, highlighting both sides of the argument. From this data swim, students then chose arguments that fit under the big umbrella of “immigration,” and they wrote claims (in complete sentences) that captured their arguments. Here were some of their claims:

• The term “illegal aliens” is racist and should not be used.

• Military service should move someone here illegally to the front of the citizenship line.

• Building a fence along the border is a bad idea.

• Building a fence along the border is a good idea.

• Illegal immigrants take jobs away from American citizens.

• Our economy will suffer if all illegal immigrants are forced out of the country.

• If you are here illegally, you should pay to stay.

• Amnesty should be granted to illegals who have proven to be productive citizens.

• Granting amnesty rewards illegal immigration.

• Having civilian border patrols is a bad idea.

• Having civilian border patrols is a good idea.

After students created their claims, I asked them to find specific stories that supported their claims. If, for example, a student believed that military service should move an illegal immigrant to the front of the citizenship line, then she was asked to find a story about a specific immigrant that supported her assertion. The selected story could be about someone she knew personally (e.g., a relative or neighbor) or it could be someone she had never met but had found via research.

As we began to work our way through drafting and revising this paper, I adopted an “I go, then you go” approach. I wrote an argument paper alongside them, and in doing so, I modeled the steps required of them. I wanted them to outline their essays before they wrote, so I outlined my essay before I wrote. There was one problem with this approach: if I had modeled an essay about immigration, many of them would have copied my stance. To avoid this, I wrote my model essay under a different big topic. Though my topic was different, the features of my model had the same features I wanted students to emulate, especially the skill of weaving a narrative into an argument paper.

I started by picking a different topic, and I showed my students, through a graphic organizer, that I had read both sides of the issue (see Figure 5.1). I chose a controversial topic—gun policy—recognizing that a topic that invites strong opposition makes a good argumentative topic. I know some of my students (and some of you reading this) will strongly disagree with my claim that high-capacity ammunition magazines should be banned. I want this disagreement; that is why it is called an argument. Also, it should be noted that the example I am sharing with you in these pages was written with the Newtown school shootings in mind, and though I am not anti-gun ownership (my father was a police officer who often took me shooting on the range), I argue in my paper that there is really no place for private citizens to own guns that have high-capacity magazines. In my graphic organizer, I listed the main reasons behind my stance, I anticipated the counterarguments, and I thought through how I would respond to the counterarguments.

So far, this was a pretty standard way to set up an argumentative paper. The twist comes in to play at the bottom of the graphic organizer, where I consider a personal experience of someone whose story strengthens my argument. In this case, I chose the true story of Vicky Soto, a teacher who lost her life trying to protect her children during the Newtown shooting tragedy. (I recognize that writing about real victims of Newtown may be difficult for readers of this book, especially those with ties to that tragedy. I apologize for any pain this may cause, but after long and careful consideration I decided to use this anecdote in my classroom because the “realness” of the example deeply strengthens the argument—an argument also made by some of the families of the victims.)

Figure 5.1 Argument graphic organizer

After a little research, I jotted down notes of Soto’s story—notes I would use to support my argument against the use of high-capacity gun magazines. My students then researched narratives that supported their claims. In Figure 5.2, you will see that Karina stated a claim—“If all immigrants were deported our economy would suffer”—and in addition to considering the points she would make and the counterarguments she would address, she chose to strengthen her argument with a story about her Uncle Miguel, who, as an undocumented worker, toils in a low-paying job.

Before we begin drafting, students will have done the following:

Made claims and gathered evidence to support their claims

Decided what the counterarguments would be and how they would respond to these counterarguments

Found narratives that strengthen their arguments

Then, and only then, is it time to draft.

To model the drafting process, I began by writing the argument section of the paper first, starting with reasons why high-capacity magazines should be banned. Here are my (rough draft) body paragraphs (counterarguments are in bold, which I explain following the draft):

High-capacity ammunition magazines should be banned for one simple reason: there have been far too many mass shootings in our country. Columbine High School. Virginia Tech University. A movie theater in Aurora. Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. People who disagree with this ban will argue that the Constitution gives them the right to bear arms, but that document was written in the 1700s—long before modern weapons were made to be much more deadly. If one were to take their argument to the extreme, where does the right to bear arms end? Can we arm ourselves with bazookas? A drone? A nuclear weapon? Their argument simply does not make sense in the modern world. The level of violence in our society today was surely not anticipated by our Founding Fathers.

Another problem with high-capacity magazines is that many people who are unbalanced can get access to these weapons at gun shows, where background checks are virtually nonexistent. Pro-gun advocates often claim that guns are not the problem, that it’s really a people problem. Exactly! It’s crazy people who are the problem, and as such, we should not let everyone off the street to have instant access to purchasing guns. We need to build in a waiting period for all guns sold. The law needs to be toughened so that any crazy person can’t walk in to a gun show and walk out with a gun (high capacity or not). No one should be able to purchase a gun without a thorough background check.

Figure 5.2 Karina’s argument graphic organizer

Many prominent people support the banning of high-capacity magazines, as well. Numerous lawmakers—both democratic and republican—have come out in favor of the ban. Also supporting this movement are a large number of our nation’s police chiefs, who are tired of being outgunned by criminals. Here in California, “An overwhelming 83 percent of voters support providing more money for efforts to take guns away from convicted felons; 75 percent support requiring anyone buying ammunition to first get a permit and undergo a background check, none of which is required now; and 61 percent support putting higher taxes on ammunition, with proceeds going to violence prevention programs” (Richman 2013). Gun advocates will say that these measures are the beginning of a slippery slope, that taking some rights away from gun owners will lead to other rights being stripped. But I agree with the voters of California, who now say it’s more important to put new limited controls on gun ownership than it is to protect Americans’ rights to own guns. Putting a limit on these types of high-volume weapons does not interfere with a person’s right to bear arms; it’s simply a sensible approach to trying to stop the next mass shooting from occurring.

In modeling these paragraphs for my students, I wanted them to recognize that each paragraph has the following features:

• A central argument that supports my claim

• The recognition of a counterargument to my argument (which I have set in bold for my students to see)

• A response to the counterargument

• Some research to support my argument (I am not simply spouting off the top of my head)

My students then emulated this process by writing the argument sections of their papers. Elias, a sophomore, took his claim (“Deporting everyone who is here illegally is not the answer”) and, after a bit of research, created a rough draft of his argument section (where you’ll see that I asked him to place his counterarguments in bold):

Elias’s Argument Section

The reality of deporting illegal immigrants is an issue lawmakers must really consider. When thinking about deporting illegal immigrants, they must consider the issue of time. If the US were to deport, let’s say, ten illegal immigrants a day, it would take at least three thousand years to deport every single illegal immigrant. People might say the goal to deport all illegal immigrants can be possible if we deport them by the thousands a day. This will only be possible if we deport around ten thousand immigrants each day, for a full three years. Let’s say we did have the money and resources to do this, do you know how long it takes for one illegal immigrant to be deported back in a civilized way? According to the Department of Homeland Security, the process to deport a single illegal immigrant back to Mexico, can take up to eight years. Eight years! As opposed to maybe a few hours to cross the border back into the United States again.

Another factor that we must consider with the reality of deporting illegal immigrants is that of money. According to an immigration and customs enforcement deputy, it costs the US around $12,500 to deport a single illegal immigrant. There are currently ten to eleven million illegal immigrants here; I’ll let you do the math. People might say this can be done by paying more money in taxes. But is this really a good idea? As of this year, the cost for deporting all of the United State’s illegal immigrants would be $285,000,000,000. This money can go to more important issues such as money going towards schools, a big problem the US is facing. This money can even go to the deficit of the US which currently stands at 1.1 trillion.

Businesses will also be affected if the deportation of all illegal immigrants were to occur. Illegal immigrants get any job that is willing to pay even the least amount of money. This makes businesses act and want to hire them. Many people see this as a problem since they feel it takes away job opportunities and money from legal citizens. Many legitimate businesses have now made it almost impossible for illegal immigrants to get these jobs for a long time now making them get open to anyone who is legal. The only jobs available are going to be the ones that no one really wants to get, and illegal immigrants will still get them. All this just means legal citizens come first at job opportunities, leaving the unemployed with an excuse.

Once the argument section of the paper was drafted, it was time to draft the narrative chosen to strengthen the argument. I went first, and it was my goal to connect my argument (“high-capacity magazines should be banned”) to a victim of a high-capacity shooting spree—in this case, Vicki Soto, the teacher who heroically lost her life trying to shield her students in Newtown. After some research, I began drafting the narrative section of the essay:

Vicki Soto loved books, the Yankees, flamingos, and Roxie, her big black Labrador retriever. She also loved kids, which is why as a first-grade teacher she often spoke of her students with “such fondness and caring” (Pearce 2012).

Vicki was murdered in the Newtown massacre.

She was killed at Sandy Hook Elementary School when a deranged gunman, Adam Lanza, opened fire on students and staff with his Bushmaster AR-15 assault-type weapon, the latest in a long line of mass shootings in the United States. Vicki, who was only 27 years old, was shot and killed after hiding some of her students in a closet. According to her mother, she loved her students “more than life” (Pearce 2012).

Vicki was buried on Wednesday, as were twenty innocent children and five other adult educators—all victims of yet another madman who had easy access to a high-capacity magazine weapon.

My students then began drafting narratives that supported their arguments. To support his claim (“Deporting everyone who is here illegally is not the answer”), Elias chose to begin his essay by writing about his own family:

I have always feared the day when I.C.E (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) would show up on my doorstep looking for my family. Some days I even ran and hid under my bed when I looked outside my home window and saw what appeared to be a policeman.

I am currently fifteen and have been here in the U.S. for almost thirteen years now. I am currently illegal, but not for long. My sister and brother both have gone through the process to becoming legal here in the US. My sister has already gotten her California ID card and my brother is just waiting on his. I am actually just a few steps away from also becoming a resident of California. My mother is going to the school to get some documents she needs to send off to get back more documents to make me legal. I consider myself very lucky now of no longer having that fear of being taken away from everything and everyone I have come to know.

At this point, I had written a draft of an argument and a draft of a narrative (as had Elias and the other students). This raised a question about the essay’s construction: How could the narrative be blended into the paper in a way that increased the effectiveness of the argument? There is no “correct” answer of course, so I wrestled with this decision in front of my students. Should I start with my Vicki Soto narrative as a way of leading into my gun control argument? Or should I first make my gun control argument and follow it with the Vicki Soto narrative? Which approach would be more effective? I thought aloud in front of my students, trying various combinations. Did I like it in this order? Or did I like it in that order? After trying a number of approaches, I decided to mix it up: I started with the Soto narrative, transitioned into my gun control argument, and then finished by circling back to the Newtown tragedy (see Figure 5.3 for my rough draft). Elias decided to start by writing about his family before transitioning into his immigration argument (see Figure 5.4 for Elias’s rough draft). Though we took slightly different approaches, blending narrative into the mix strengthened both of our arguments.

Figure 5.3 The rough draft of my argument essay on gun control, with narrative woven in

Figure 5.4 The rough draft of Elias’s argument essay on deportation, with personal narrative woven in

In the real world we do not artificially separate discourses; we blend them. I want my students to understand how the power of narrative can be used to strengthen an argument.

With the adoption of the CCSS, I am concerned that the testing pressures around the big three writing types—narrative, inform and explain, and argument—will create classrooms in which the teacher, as a way to ensure students gain proficiency across the tested discourses, prescribes exactly what the students write. I am afraid that given the testing pressures, student choice will be endangered. This concern might come across as a bit hypocritical, given the fact that the previous example in this chapter illustrated a unit in which I chose the topic for my students. (The topic was immigration—though even when I choose a big topic like immigration, my students have lots of fertile ground in which to develop a variety of arguments. There is not one argument to be made under the umbrella of “immigration”; there are several possible choices.) But beyond assignments like the immigration argument paper, I am careful to make sure my students have plenty of other opportunities to self-select the topics they want to explore via writing (more on this soon).

As much as possible, I am trying to create agency in my young writers. Students who have acquired agency don’t need the teacher to assign them a prompt; they are young writers who are able to independently generate writing from self-initiated ideas. They revel in choice—the very choice I am afraid will disappear in classrooms operating under the testing pressures generated by the Common Core writing standards.

One way I generate agency in my students is through the formation of writing groups, a weekly structure where students share self-generated writing. Let’s take a closer look at how these groups help to develop agency in young writers.

Every Thursday my students meet in their writing groups. Each group consists of five students of mixed gender and ability. All written pieces brought to the writing groups are self-generated by the students, and for each writing group meeting, students are asked to bring either a new draft or an old piece they have significantly revised. They are also asked to bring copies of their pieces for each of the other members of their groups. This means that if a student is in a group of five, she brings five copies of her piece to the discussion.

Once in the groups, each student takes a turn sharing his or her piece with the other members of the writing group. When it is a student’s turn to share, he or she distributes copies of it to the other group members and, before reading it aloud to the other group members, indicates the level of response he or she would like from peers. The student asks the group to provide one of the following three levels of response (these originated years ago somewhere in the National Writing Project):

Bless: When a student requests “bless,” he asks for his peers to note only the things they like about the paper. Elements students might bless include diction, sentence structure, the introduction and/or the conclusion, sequencing, realistic use of dialogue, or a favorite segment of the paper. When the writer requests “bless,” no criticism of the paper is allowed. All comments are positive. Hakuna matata only.

Address: When a student requests “address,” she is asking for peers to look at a very specific element of the paper. For example, a student might ask the others in the group to pay close attention to a particular section of the paper she is having trouble with and to offer some thinking on how to work through the difficulty. When a student asks for “address,” she dictates exactly where in the paper she would like her fellow group members to focus their feedback.

Press: When a student requests “press,” he is indicating to his partners that all comments are welcome. Partners can offer constructive criticism, praise, and/or suggestions. Anything goes—provided the feedback helps the writer to make the paper better.

Let’s say it is Robert’s turn to share his piece with his writing group. Robert distributes copies to the others in his group, and because he is a reluctant writer, he asks his partners to “bless” his paper. Once the copies are distributed, Robert reads his paper aloud to his group, who are following the reading with pencils in hand and quickly marking areas they may “bless.” When Robert finishes reading, he sits silently for a couple of minutes while his partners revisit the paper, highlighting areas of strength in the paper. This is all done silently. His partners then grab precut quarter sheets of paper and write comments to Robert (based on the markings they made while Robert read the paper to them).

When each group member has had a chance to write his or her comments on individual quarter sheets of paper, the conversation phase begins. The writer remains silent while each group member—one at a time—shares his or her thinking aloud with the group. Once every member has shared thinking about the piece, Robert is then invited to talk. He can respond to one or more of the comments that came his way, or he can send the conversation in a new direction. At this point, the conversation is open—anyone can share his or her thinking. When the conversation has run its course, the partners pass their comment sheets to Robert, who then collects and staples them to his paper. If Robert wants to revisit the paper later in the year, he will have these written notes attached to his draft to jog his memory.

The group then turns its attention to the next person in the group. She distributes her paper, indicates whether she wants her paper blessed, addressed, or pressed, and the process is repeated.

When the groups meet again the following week, students bring copies of new drafts (or heavily revised) previous drafts, and the bless, address, press process begins anew.

If you are interested in setting up similar writing groups in your classroom, here are some suggestions:

• Model how the groups work. I cannot simply give my kids a handout that explains the process; students need to see the process. Last year, all senior classes participated in writing groups, so on the day the three senior English teachers introduced the idea, we gathered all of our seniors into the school’s theater where we modeled the process. This means we each wrote a separate piece. We were careful to mix up genres—I wrote a poem, one of my colleagues wrote a personal narrative, and my other colleague wrote an argument. We had the students watch us as we modeled the process (one of us asked for “bless,” one of us asked for “address,” and one of us asked for “press”). We had the students take notes on the drafts as well, and we had them fill out quarter-sheet comments. When it came time to discuss the papers, we invited all the students in the theater to participate. This fishbowl demonstration was crucial in getting our students to understand the process.

• Do not begin the writing groups too early in the year. I want to make sure I get to know my students pretty well before groups are formed. I also want the writing culture of the classroom to develop before asking kids to share their writing with one another. My writing groups are usually formed around the beginning of the second quarter of the school year.

• The teacher should select the writing groups, taking into careful consideration the makeup of each group. I mix gender, because boys and girls often think differently. I mix ability levels as well, making sure that students have access to at least one strong writer in each group. I try to place reluctant writers with students who will be nurturing.

• Writing groups should stay together for the remainder of the year. Many groups start off a bit shy, but one of the beauties of writing groups is the bond that grows within them over time. At first, most students are a bit freaked out about sharing their writing with their new group members. Initially, most ask for “bless” only. But as time passes and they begin to trust one another, they start to open up. Last year, some of my groups celebrated each week by bringing small snacks for their fellow group members. By the end of the year, the groups really know one another well and are often sad to “break up.”

Here are some problems I have encountered in setting up and running writing groups, and how I addressed them:

WRITING GROUP PROBLEM |

HOW I ADDRESS THE PROBLEM |

A group has trouble generating conversation for an entire class period. |

I sit in with the group and participate alongside them. When the conversation lags, I interject a comment or question to restart the conversation. If a group finishes with a few minutes remaining, its members can take out their writer’s notebooks and begin quietly drafting a new piece for the next week’s meeting. |

A student shows up unprepared for the group discussion. |

I adopt a “three strikes, you’re out” policy. For a first or second offense, I allow students to participate without bringing a piece to share (I believe they benefit from seeing others’ writing, and I want the peer pressure of being part of the group to kick in). If it becomes habitual, I remove the student from the group and have him or her sit off to the side of the class where he or she will draft quietly. Usually, this is enough to get the student back on track. |

If a student misses the writing group day but shows up the next day with a draft, I give half credit (even if the absence is excused). A student cannot receive full credit unless she participates in the group discussion, since that’s where much of the value lies. This is explained to my students ahead of time. |

|

A student keeps writing the exact same type of paper each week (for example, a student shows up with a poem every week and doesn’t stretch himself into other writing discourses). |

Though students can freely choose topics and discourses, they are encouraged to do so with the end-of-the-year portfolio in mind (more on the portfolio requirements later in this chapter). A student who writes a poem every week will be unprepared when it comes time to select portfolio pieces. Students are reminded of the portfolio requirements every few weeks and told that by the end of the year they should have written broadly. |

A student writes way too much for the group to respond to in a short time. |

Last year, I had a student, Eric, who decided that he would use writing group as a way to get feedback on the novel he was writing over the course of the year. Every time his group met, he handed each of them twenty pages to read. To streamline the discussion, I had Eric select a two-page excerpt from his weekly work for the group to bless/address/press. |

A student shows up with his writing piece but doesn’t have copies for his partners to track while he shares. |

I teach in a low-income school, so many of my students do not have printers (or ink) at home. They can print in our media center for ten cents a page, or they can come in to my classroom before school and print for free. Yes, I run through a lot of ink and paper, but I have secured funding from various school sources to keep the printers printing. |

One last question that always arises regarding writing groups: How do you score all those papers? The short answer: I don’t! My goal is to get my students to write independently—to see themselves as writers who write regularly. This is much more likely to happen if I don’t grade everything. Grading doesn’t make my students better writers. Lots of practice coupled with meaningful feedback makes my students better writers. On writing group day I quickly move between the groups, stamping their drafts with the date. Later I give them points for every stamp they accumulate. Many of their writing group papers will never be graded. Others will be selected for and assessed in the end-of-the-year portfolio.

As stated earlier, I am afraid that the adoption of the Common Core writing standards will drive many teachers to micromanage writing topics. This is the beauty of writing groups. Kids choose their own topics.

How do I ensure that my students get a good mix of writing experiences, from wide-open, student-generated to topics generated from the teacher? I start with my end-of-the-year portfolio requirements and work backward. Here, for example, are the pieces I require my students to include in their portfolios (along with brief explanations):

1. Baseline Essay: During the first week of school I have my students write an essay without any help from me. The purpose is to gather a writing sample that establishes a baseline of where they started the year as writers. The baseline essay is not revised in the portfolio. Students are asked to revisit the baseline essay at the end of the year to remind themselves where they were as writers at the beginning of the school year. This enables them to reflect on their growth.

2. Myself, the Writer, Reflective Letter: This is the most important portfolio piece. Students are asked to read through their body of work and to reflect on their year as writers. Some questions I have them consider before they draft their letters:

• In what areas—specifically—did you grow as a writer? Can you point to these areas in this portfolio?

• What are your favorite discourses? Least favorite? Why might that be?

• Reflect on a struggle you faced as a writer this year. What did you learn from the struggle?

• Discuss specific writing strategies you’ve used with references to specific pieces you’ve written.

• Where does your writing still need improvement? How will you improve?

• Reflect on your experiences in your writing group. What worked? What did not work? How could writing groups be improved?

• What are your immediate and long-range goals as a writer?

• Have you developed agency as a writer? Do you write without being asked to? Why? Why not?

3. Best On-Demand Writing: Over the course of the year, my students are asked to do one timed-writing per month. Students are asked to select their best on-demand writing performance. This essay is not revised for the portfolio.

4. Best Narrative Piece: Each student is asked to include a narrative (real or imagined). Students are encouraged to blend other discourses into their narrative pieces. The selected piece should be revised at least one more time.

5. Best Inform and Explain Piece: Each student is asked to include an informative and/or an explanatory piece. Students are encouraged to blend other discourses into their inform and explain pieces. The selected piece should be revised at least one more time.

6. Best Argument Piece: Each student is asked to include an argument piece. Students are encouraged to blend other discourses into their argument pieces. The selected piece should be revised at least one more time.

7. Best Poetry: Students are asked to include samples of their best poetry.

8. Best Article of the Week Reflection: My students are given an article to read each week, and as part of that assignment, they write one-page weekly reflections. I have students select their best reflections, which should be revised before entering the portfolio.

9. Best Writing from Another Class: Each student selects a writing sample from another class and revises it before placing it in the portfolio. He or she includes a brief note explaining the context of the writing assignment and why he or she likes this piece of writing.

10. Best One-Page Evidence of Revision: Each student is asked to include one page where the ability to deeply revise is evident. This page should be heavily marked up—very messy—and is accompanied by a note that explains what the writer did to make this paper better.

11. Wild Card: Students are asked to select something they wrote inside or outside of class. Maybe it is something they wrote in their writer’s notebooks but never turned in. Or it can be something more unconventional (an e-mail or tweet). It can be secretive (a poem written without anyone’s knowledge). It can be anything. This is also the place where a student might submit a piece that does not fit neatly under the big three CCSS writing genres.

12. Sentence of the Week Checklist: If I do a mini-lesson on the proper use of semicolons, then I want to see that my students are incorporating semicolons into their writing. I provide students with a list of all the mini-lessons we did that year, and I ask them to indicate on which pages of the portfolio I will be able to find the infused skills. This list is the final piece placed inside the portfolio.

13. Best Single Line You Wrote This Year: Each student selects the one favorite line he or she wrote that year and places it on the back cover (facing out). It is not accompanied by anything else. It just stands there, alone, out of context.

My students spend the last two weeks of the school year working on their portfolios. I do not, however, wait until the end of the year to share the portfolio requirements with them. These requirements are given to them at the beginning of the school year, and they frequently revisit them as they write their way through the year. To help keep them on track, I give them a “Track Your Writing” chart and every time they finish a draft, they add it to the chart (see Appendix A or go to http://www.kellygallagher.org [click on “Resources” and select the “Track Your Writing” chart from the drop-down menu]). If a student is writing nothing but narratives, for example, the empty spaces in his chart tells him that that he needs to start to venture into other writing discourses.

It is also important to note that even though I am prescribing the categories to be placed in the portfolios, there is a lot of student choice built in. For example, a student might fulfill the narrative requirement of the portfolio by selecting a self-generated piece that was written for her writing group.

Because the standardized tests that assess Common Core standards use “one and done” writing activities, they may not value the deeper kind of writing we want to nurture in our students. To illustrate this concern, let’s look at a sample middle school argumentative writing task as prepared by the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium:

Read the text and complete the task that follows it.

Cell Phones in School—Yes or No?

Cell phones are convenient and fun to have. However, there are arguments about whether or not they belong in schools. Parents, students, and teachers all have different points of view. Some say that to forbid them completely is to ignore some of the educational advantages of having cell phones in the classroom. On the other hand, cell phones can interrupt classroom activities and some uses are definitely unacceptable. Parents, students, and teachers need to think carefully about the effects of having cell phones in school.

Some of the reasons to support cell phones in school are as follows:

• Students can take pictures of class projects to e-mail or show to parents.

• Students can text-message missed assignments to friends that are absent.

• Many cell phones have calculators or Internet access that could be used for assignments.

• If students are slow to copy notes from the board, they can take pictures of the missed notes and view them later.

• During study halls, students can listen to music through cell phones.

• Parents can get in touch with their children and know where they are at all times.

• Students can contact parents in case of emergencies.

Some of the reasons to forbid cell phones in school are as follows:

• Students might send test answers to friends or use the Internet to cheat during an exam.

• Students might record teachers or other students without their knowledge. No one wants to be recorded without giving consent.

• Cell phones can interrupt classroom activities.

• Cell phones can be used to text during class as a way of passing notes and wasting time.

Based on what you read in the text, do you think cell phones should be allowed in schools? Using the lists provided in the text, write a paragraph arguing why your position is more reasonable than the opposing position. (Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium 2014b)

Looking at this sample question, I am struck by how many factors get in the way of students actually producing good writing: (1) It is on-demand. (2) Students are handed the “argument” to be made. (3) There is no inquiry involved. (4) The reasons supporting a student’s thesis are already provided. (5) Students are not required to think.

Students who answer this prompt are not being asked to craft an argument; they are being asked to spit back information that has already been spoon-fed to them. This prompt almost invites students to write in the five-paragraph format I warned against in Chapter 4. However, if we teach students how to write deeper arguments like those outlined in these chapters, they will do fine on the state tests. On the other hand, if we only teach students to write to the level of the test, they will never master the skill of argumentative writing. (The same holds true when it comes to the teaching of narrative and informational writing.) We should aim our writing instruction far above the bar posited by the exams thus far created to assess Common Core skills.

Let’s briefly revisit the strengths and weaknesses of the Common Core anchor writing standards:

COMMON CORE ANCHOR WRITING STANDARDS |

|

THE STRENGTHS |

THE SHORTCOMINGS |

1. Reading and writing are connected. 2. The new Common Core writing standards may drive more writing across the curriculum. 3. Process writing is valued. 4. Writing skills are sharpened in the following discourses: narrative, inform/explain, and argument. |

1. Though narrative writing is one of the genres required by the CCSS, it remains undervalued. 2. The big three writing discourses are too limiting. 3. There is an artificial separation between writing discourses. 4. The Common Core writing standards endanger student choice. 5. The CCSS exam may actually lower the writing bar. |

Teachers who adhere blindly to the new Common Core writing standards without considering their shortcomings will not be serving their students well. Let’s take the best of what the new anchor writing standards have to offer while remaining mindful of their shortcomings. Most importantly, when it comes to the teaching of writing, let’s make sure our core values (rather than the current standards movement) continue to drive us to do what is in the best interest of our students.