In Chapter 2, we began our discussion about the teaching of reading by first looking at the strengths of the Common Core anchor reading standards. In Chapter 3, we then examined the weaknesses of these standards, keeping in mind that we need to be sure that our reading instruction stays true to what is in the best interest of our students. We now turn our attention to the teaching of writing, and we will follow the same sequence: this chapter, Chapter 4, examines the strengths of the Common Core anchor writing standards, and, in doing so, offers teachers strategies proven to elevate student writing. (Again, I know some states have not adopted the CCSS, but I do believe all teachers will benefit from a close examination of the strengths found in these standards.) Chapter 5 takes a close look at the shortcomings of the new writing standards so that we can ensure that our writing instruction stays true to what is in the best interest of our students.

First, let’s look at the Common Core anchor writing standards.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.1 Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.3 Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.5 Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.6 Use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing and to interact and collaborate with others.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.7 Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.8 Gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources, assess the credibility and accuracy of each source, and integrate the information while avoiding plagiarism.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.9 Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.10 Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

Source: (NGA/CCSSO 2010d)

Following are six strengths found in the anchor writing standards.

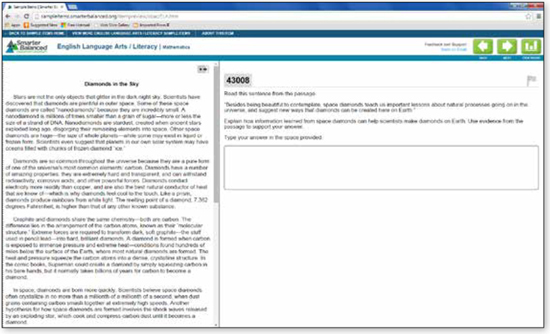

Unlike many states’ standards in the NCLB era, which virtually ignored writing, the CCSS weave reading and writing together. Figure 4.1 is a sample assessment item released by the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (2014a).

Figure 4.1 “Diamonds in the Sky” assessment item

In the example shown in Figure 4.1, students are first asked to read a passage about space diamonds and then to explain via writing how information learned about space diamonds can help scientists make diamonds on Earth. There are two things worth noting in this example: (1) the reading and writing are science-based, which reinforces the critical idea that teaching students how to better read and write is a shared responsibility among teachers of all content areas (not just English teachers); and (2) the writing required by the prompt is text-dependent, meaning that the students cannot answer it without a close reading of the passage. Gone are the days (at least for now) when students will be asked to write responses to stand-alone prompts. The new standards—and many of the newly adopted tests—require students to weave reading and writing together, and this is a good thing.

Because the CCSS recognize that reading and writing are interconnected, and because the assessments generated by the CCSS require students to write across various content areas, I remain hopeful that students will be asked to write more in classes other than English. Of course, for many of us this seems silly, for we know the value of having our students write every day. The powers that be could take every assessment away tomorrow and we would still have our students write daily. But the sad truth is that there are teachers out there who need their feet held to the testing fire before writing will occur in their classrooms, and assessments of Common Core standards provide that fire. If a test is what it takes to get some teachers to integrate more writing into their curriculum, this is also a good thing.

Many of my students begin the year as “one-and-done” writers. They write one draft; they are done. They think “revision” means “type it.” I am hoping that the CCSS will help students—and teachers—to push past one-and-done writing and into multiple-draft practice. It is important to keep the tenth anchor writing standard in mind, which asks students to “write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision)” (NGA/CCSSO 2010d). Our students should wrestle with the cognitive challenges that occur when working on a paper over an extended period of time. Doing so produces a much deeper level of brain exercise than simply writing a single draft and walking away from it.

As I outline in Write Like This, the best way to help students to internalize the value of moving beyond one and done is through intensive modeling (Gallagher 2011). We should provide models…

… before they begin writing (by outlining and brainstorming).

… as they begin writing (by writing alongside them and presenting them with mentor texts).

… when they share and respond to one another’s papers (by first responding to the teacher’s draft).

… to demonstrate how revision occurs (by using student and teacher models as examples).

… that help students properly edit a paper (by using mentor sentences to teach these editing skills).

… to ensure our students learn proper manuscript guidelines (by using exemplary examples for guidance).

Far from one and done, our modeling should be woven throughout the writing process. This level of modeling marks the crucial difference between assigning writing and teaching writing.

Narrative writing is one of the big three writing genres of writing valued by the CCSS. This is important since the ability to tell a good story is a skill that resonates well beyond the walls of the English classroom.

In Write Like This, I share a number of narrative writing activities I worked through alongside my students (Gallagher 2011). Following are more narrative writing ideas that invite students to write longer pieces. For each of them, you will see my brainstorm of possible writing topics on the left-hand side and the ideas my students brainstormed on the right-hand side.

Some moments in our lives matter more than others. For this writing activity, students are asked to consider the moments in their lives that really matter. I share my list, and then students create their own lists, which generate numerous writing possibilities.

MR. GALLAGHER’S MOMENTS THAT MATTERED |

STUDENTS’ MOMENTS THAT MATTERED |

• The start of a friendship • The end of a friendship • Meeting my future wife at a wedding • The birth of each of my children • My parents informing me they were divorcing • The death of my father • Adopting our dog, Scout • Receiving notice that my first book would be published • Dropping out of school (which led me to reconsider my career) • Being told we were moving • An automobile accident • Seeing my sister being arrested • The talk with my grandfather • Hearing Sheridan Blau speak at a teaching conference • Reading Sophie’s Choice |

• That kiss • The Prom • Meeting my best friend • Getting suspended • Moving from Puerto Rico • Making the team • My mom’s new boyfriend • Getting my driver’s license • Moving in with my dad • Getting hired at Wendy’s • Breaking up with my boyfriend • 9/11 • Failing geometry • Attending my first funeral • Saying no to my mom • Stopped smoking weed • When my dog died • Staying home alone for the first time • Being introduced to snowboarding |

We have all been stranded, physically and/or emotionally.

MR. GALLAGHER’S STRANDED MOMENTS |

STUDENTS’ STRANDED MOMENTS |

• Stuck in O’Hare at midnight with no hotel room or rental car • Locked out of my family home (as a young boy) with everyone gone for the weekend • Living alone in a New York City apartment • Left by my group to finish the high school project • Staring at a blank page when facing a deadline • Standing next to my conked-out VW on the side of the freeway |

• Getting lost in the grocery store • My friends moved away • Trying to write an essay the night before it is due • Phone dies while trying to meet someone • Stuck in a jail cell without my parents knowing • Stuck at a friend’s house during Hurricane Sandy • Getting suspended • Alone during a blackout • Got lost on the train • Home alone during a thunderstorm |

Students are asked to consider times when weather was a factor.

Students are encouraged to write about significant changes in their lives.

MR. GALLAGHER’S SIGNIFICANT CHANGES |

STUDENTS’ SIGNIFICANT CHANGES |

• Introduction to meditation • Hair style • New Year’s resolution: no more french fries • Brad after his brain surgery • Quitting an old job and starting a new job • Breaking up with a girlfriend • Disney buying the Anaheim Angels • Moving to New York • Teaching a new grade level • The closing of my favorite breakfast restaurant • Empty nest syndrome: daughters leave home • Jeremy Renner is not Jason Bourne |

• Cutting off my braids • From Blackberry to iPhone • Changing jobs • Moving to Harlem • Facebook re-do • Beating my father in pool for the first time • Getting a girlfriend • New grading system • New baby in the family • New zit • Mom losing her job • New friend • Miley Cyrus—what happened? • My father’s attitude • New student in our writing group |

Students are asked to reflect on attempting something for the first time.

MR. GALLAGHER’S FIRST ATTEMPTS |

STUDENTS’ FIRST ATTEMPTS |

• Driving a stick shift up a hill • Building a skateboard • Learning to ski • Writing a book • Teaching my first class • Eating escargot • Bodysurfing • Creating a website • Navigating the subway system • Trying that yoga pose |

• Drinking • Reading a new genre • Working out • Driving a golf cart • Cutting my own hair • First demerit • Getting arrested • Getting “stopped and frisked” • Shaving • Kissing a girl |

Students are asked to consider a time they were unprepared.

MR. GALLAGHER’S UNPREPARED |

STUDENTS’ UNPREPARED |

• Job interview(s) • Entering the Fire Academy • Physics exam in college • Giving a speech at a basketball banquet • Teaching a summer school math class • For the ending of the following films: Planet of the Apes, Gallipoli, Soylent Green, The Sixth Sense, The Crying Game • News of parents’ divorce • Friend’s cancer news |

• College interview • My uncle coming out • My grandmother dying • Hurricane Sandy • Socratic seminar in social studies • My cousin’s pregnancy • SpongeBob getting canceled • Attending my friend’s funeral • Stuck outside without an umbrella • Watching Paranormal Activity—it freaked me out! |

Students are asked to write about near misses they have experienced.

MR. GALLAGHER’S NEAR MISSES |

STUDENTS’ NEAR MISSES |

• Near runway collision • Near barbed wire decapitation • Almost drowned • The shot that would have won the basketball game • Losing control of the car in the ice storm • Rams losing to the Steelers in the 1979 Super Bowl • Seagull poop attack • Sledding accident |

• Nearly getting electrocuted • Jennifer Hudson on American Idol • One girl texting me when I was with another girl • Almost got caught cheating on a test • Losing the game by 1 point • Almost falling off a balcony • Getting away with losing my phone • Coming in 2nd in a dance competition |

Students are asked to discuss a time they had to choose a side.

MR. GALLAGHER’S CHOOSING SIDES |

STUDENTS’ CHOOSING SIDES |

• Coke or Pepsi? • Obama or Romney? • Mom or Dad? • USC or UCLA? • Angels or Dodgers? • United Airlines or American Airlines? • Jimmy: Fallon or Kimmel? • Back in the day: English department versus social science department |

• This high school or another high school? • Junk food or healthy food? • Run or fight? • Candace or Bria? • Knicks or Heat? • Play Station or Xbox? • Go out for football or basketball? • Lebron or Melo? • USA or Mexico soccer teams? |

Students are asked to write about times when they taught others something.

MR. GALLAGHER’S YOU ARE A TEACHER |

STUDENTS’ YOU ARE A TEACHER |

• Taught my nephew how to spin a basketball on his finger • Taught my daughters to value reading • “The Ethicist” column in the New York Times taught my daughters ethics • Training new waiters • Teaching basketball player how to tie a tie |

• Taught my sister how to count • Taught my grandma how to use an iPhone • Taught myself to memorize Shakespeare • Taught myself to be a vegetarian • Taught my sister how to cook • Taught my little brother how to call 911 • Taught my mom how to speak English |

Students are asked to discuss how they got from one place to another.

MR. GALLAGHER’S FROM A TO B |

STUDENTS’ FROM A TO B |

• Walking three miles to junior high every day • First airline flight (ending in disaster) • Endless car trip to Mexico City • Secret midnight horseback riding in Laguna Beach • Skateboarding the Huntington Beach boardwalk • Running the half mile for the track team • My dad giving us wheelbarrow rides • Go-kart racing • Canoeing the Colorado River • Zip line in Cancun • Snorkeling across Honolua Bay • Taking the train to Berlin • Nightmare trip—Orange County to Michigan: 20 hours • Seasick on boat to Catalina Island • Stuck on a BART train underneath San Francisco Bay |

• First train ride by myself • Sneaking out through the fire escape • Driving to find the block party • Driving to Florida/Disney World • The cab ride from hell • Crossing state lines • Walking home from the hospital • Riding a garbage can lid in the snow • Six mile walk after car broke down • Swimming in the Gulf of Mexico • The fight on the subway • First ride on the Long Island Ferry • Ditching to take the train to Coney Island • My first solo motorcycle ride • Long car ride: 4 kids/2 seats • Riding bikes to Chelsea Pier • Riding a scooter in Honduras • Running endlessly in basketball practice • How I went from being a junior to being a senior • Walking from Harlem to the WTC • Going from happy to sad in an instant |

The ability to inform and/or explain is a real-world writing skill I want my students to practice. Additionally, it is one of the three types of writing valued by the CCSS and the new generation of tests. With this in mind, the following exercises invite students to write longer pieces in this genre.

In Write Like This, I share a “Bucket List” assignment where my students listed all the things they would like to do before they die (Gallagher 2011). Inspired by Jeffrey Goldberg’s column in the Atlantic, I now have my students create reverse bucket lists—lists of things they are positive they never want to do (2011). I go first:

Mr. Gallagher’s Reverse Bucket List

1. Eat sushi

2. See any movie featuring Renee Zellweger

3. See any movie featuring Sarah Jessica Parker

4. See any movie featuring Arnold Schwarzenegger

5. Play Candy Crush

6. Go to a Pit Bull concert

7. Get a job as a telemarketer

8. Play golf

9. Get a pet turtle

10. Hang out in Times Square on New Year’s Eve

11. Hang out anywhere on New Year’s Eve

12. Join the Duck Dynasty fan club

13. Read a Stephenie Meyer book

14. Shop at any mall

15. Run an ultra-marathon

16. Request a middle airline seat

17. Become a Yankees fan

18. Subscribe to Oprah

19. Become a dentist

20. Wear a monocle

21. Visit/shop at a pet store

22. Go to Disneyland on a summer day

23. Retire to Florida

24. Write a book about penguins

25. Gather a deep understanding of the US tax code

26. Collect snow globes

27. Get a facial tattoo

28. Pierce my nose

29. Take yodeling lessons

30. Go on a Disney cruise

My students then create their reverse bucket lists. Here is a sampling:

1. Twerk

2. Eat frog legs

3. Become a taxi driver

4. Clean zoo cages

5. Shave my head

6. Work at McDonald’s

7. Watch every episode of Law and Order

8. Date a girl with less hair than me

9. Get an STD

10. Work as a janitor

11. Sing a Justin Bieber song

12. Go to jail

13. Go back to jail

14. Play ping pong

15. Be at a graveyard at night

16. Open a restaurant

17. Buy a motor scooter

18. Visit Siberia

19. Watch Vampire Diaries

20. Make coleslaw

21. Learn how to knit

22. Ride in an ambulance

23. Go on a safari

24. Get hit by pepper spray

25. Give birth

26. Repeat 12th grade

27. Play bridge

28. Study the history of catsup

29. Raise snakes

30. Be featured on YouTube

From their lists, students pick one (or more) and explain in detail why it (or they) made the list.

Every issue of ESPN magazine has a one-page column titled, “Six Things You Should Know About …” In Figure 4.2, you can see an example of six things you should know about playing in the World Cup. Here are other recent topics found in the magazine:

Six Things You Should Know About …

… being a Pro Gamer.

… acting in a Sports Movie.

… faith in the Locker Room.

… treating NHL Teeth.

… owning a NASCAR Team.

… dealing at the World Series of Poker.

… the Westminster Kennel Club Show.

… the upcoming Olympics.

Figure 4.2 Sample “Six Things You Should Know About …” article

The examples from ESPN magazine are all sports related, but I ask my students to brainstorm topics both inside and outside the world of sports. Here are some topics I modeled, next to some of my students’ topics:

Six Things You Should Know About… (Mr. Gallagher’s List) |

Six Things You Should Know About… (Students’ List) |

… buying a car. … renting an apartment. … owning a dog. … becoming a teacher. … being a parent. … writing a book. … being in an airport. … being an Angels fan. … coaching high school basketball. … applying to college. … applying for a job. … our school library. |

… playing Grand Theft Auto V. … passing AP biology. … being a babysitter. … playing varsity football. … being a twin. … the McDonald’s menu. … a Galaxy 7 phone. … being in student government. … playing soccer. … Instagram. … Harlem. … the subway system. |

After we brainstorm, I choose one topic and write a model for my students, noting the formatting of the magazine piece (e.g., each of the “things” is numbered and in bold font). I take students into the computer lab and teach them how to insert a stock photo and how to wrap text around it. In Figure 4.3, you will see the first page of my rough draft of “Six Things You Should Know About Writing a Book.” Figure 4.4 shows Alicia’s first draft of “Six Things You Should Know About Being a Twin.”

Figure 4.3 The first draft of my “Six Things…” piece

Figure 4.4 The beginning of the first draft of Alicia’s “Six Things…” piece

One of my students’ favorite writing assignments is to inform the reader of significant moments in history that occurred on their birthdays. There are a number of “This day in history” websites where a student can type in his or her birthday and get a list of important historical occurrences from that day (my favorite site is www.onthisday.com). Here, for example, are important historical events that occurred on my birthday, October 9 (http://www.on-this-day.com/onthisday/thedays/alldays/oct09.htm):

1781: The last major battle of the American Revolutionary War took place in Yorktown, VA. The American forces, led by George Washington, defeated the British troops under Lord Cornwallis.

1855: Isaac Singer patented the sewing machine.

1858: Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson made their longest telephone call to date (two miles).

1940: St. Paul’s Cathedral in London was bombed by the Nazis.

1940: John Lennon was born.

1944: Churchill and Stalin conferred.

1974: Oskar Schindler died in Frankfurt, Germany. Schindler is credited with saving the lives of 1200 Jews during the Holocaust.

1986: The musical Phantom of the Opera by Andrew Lloyd Webber opened in London.

1994: The U.S. sent troops and warships to the Persian Gulf in response to Saddam Hussein sending thousands of troops and hundreds of tanks toward the Kuwaiti border.

Students choose one event and explain the details of the event to the reader. If teachers want to add another layer to the assignment, they can also ask students to argue why this historical event still matters today.

As English teachers, we spend a lot of time teaching students the power of words. In generating informative writing, there is value in having students consider the power of photographs as well.

On April 24, 2013, an eight-story commercial building housing garment factory workers collapsed in Bangladesh, killing an estimated 1,129 people and injuring 2,515 others. Taslima Akhter, a photographer, rushed to the scene and took a heartbreaking and haunting photograph of two deceased workers embracing one another in the rubble. (Because of the disturbing nature of the photograph, I chose not to include it in these pages. It can be viewed by searching “Taslima Akhter” online.) Akhter’s photograph mattered: it helped spark an outcry that manifested itself in protests and riots, ultimately culminating in labor laws being reformed in Bangladesh.

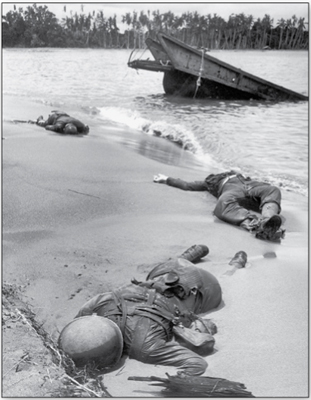

Figure 4.5 George Strock’s famous photograph of dead American soldiers at Buna Beach

Using Akhter’s photograph as a starting point, I move to George Strock’s famous photograph of dead American soldiers at Buna Beach, which shows the bodies of American serviceman washed up on the beaches on Papua New Guinea (see Figure 4.5). First published in Life, this photograph shocked Americans, who were insulated from the grim realities of the war. The editors of Life knew that in this case a picture spoke more than a thousand words, and, apparently, so did President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who lifted the ban on images depicting U.S. casualties. Strock’s photograph “ended the censorship rule, boosted support for the war and had a lasting effect on photo journalism” (Associated Press 2013). It is also interesting to note that Roosevelt’s strategy in releasing the photograph was the opposite of the strategy employed by George W Bush, who forbade any photographs from being taken of flag-draped coffins returning from Iraq. Both presidents knew the power of photography.

After sharing these photographs by Akhter and Strock (and why they mattered), I ask students to research and find photographs that mattered and, after researching their photographs, to explain why they mattered. One great resource for students to start their searches is 100 Photographs That Changed the World (Sullivan 2003). (Students can also find Strock’s iconic photograph in this book.)

In the New York Times Magazine, published every Sunday, is a column titled, “Who Made That?” This column informs the reader how and where common, everyday items originated. (For example, see Figure 4.6, where the reader learns who first made flip-flops.) In recent weeks, this column has highlighted the people who first made…

… dog tags. |

… the planetarium. |

… the home pregnancy test. |

… the corkscrew. |

… Nigerian scams. |

… the contact lens. |

… the tricycle. |

… the food truck. |

Figure 4.6 From the New York Times Magazine’s “Who Made That?” series

This year, my colleague Isabel Yalouris asked her seventh-grade students to pick common items and to research their origins. In Figure 4.7, you will see how Anaya explains the origin of the woman’s handbag.

Figure 4.7 Anaya’s “Who Made That?”

Last year, my students made a classroom edition of “Who Made That?” by binding all their responses into one booklet and then placing the booklet in the classroom library.

Another idea taken from the New York Times is a column titled “36 Hours in …,” which is found in the newspaper’s weekend travel section. This column recommends how a person might spend thirty-six hours in a given city, providing suggestions on where to stay, where to eat, what to do, and what to see within a thirty-six-hour time frame. Using this newspaper column as a template, Yalouris had her students emulate the “36 Hours in…” format. Hadja, a seventh grader, put together a thirty-six-hour itinerary for a visit to New York City that included the following stops: Times Square, the Barclay Center, a Serendipities ice cream parlor, the Statue of Liberty, Yankee Stadium, the Magic Johnson Theater, Riverside Park (for ice skating), the Bronx Zoo, and the Empire State Building. Each suggested stop was accompanied by a short paragraph giving the potential visitor more information (e.g., hours, cost, why this spot is worth the visit).

Have your students choose locales and have them explain to the reader how best to spend thirty-six hours there.

Another colleague of mine at the Harlem Village Academies, Dave Hibler, had his students create theme newsletters under the umbrella of informational writing. Each student was asked to choose a big topic, and then to generate four informative pieces that fit under the big topic. Hibler, an avid runner, created a model newsletter around the topic of running. He wrote four pieces: (1) suggestions on the best places to run in New York City; (2) ten tips for long-distance running; (3) a biography on a student runner; and (4) a news report on a student track meet. After completing his writing, Hibler taught his students how to lay out the pieces in a newsletter format.

Dave’s students then emulated him. Esther, a seventh-grade student, created a newsletter on the topic of reading urban fiction. Her four pieces: (1) an introduction to the genre; (2) an explanation of myths versus facts regarding urban fiction; (3) profiles on prominent authors in the genre; and (4) reviews on three books students might want to read in the genre (see Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.8 Esther’s theme newsletter on urban fiction

Have your students choose topics they are passionate about and have them create newsletters containing articles that offer further information and/or explanation to the reader.

Of the three big writing types, the authors of the CCSS place the heaviest emphasis on our students’ ability to write effective arguments. The standards suggest that by the end of the twelfth grade, 40 percent of a student’s writing done in schools be argumentative in nature. (This 40 percent target also raises some concerns—see Chapter 5.) With such a heavy emphasis on teaching the argument paper, here are five key points to keep in mind.

To understand the difference between persuasion and argument, one needs to look no further than the Norm Reeves Honda Superstore, a car dealership in Southern California. In an attempt to persuade consumers to visit their dealership, the folks at Norm Reeves promised in advertisements that customers could lease new cars without paying anything up front. This form of persuasion worked in getting people to visit the car lot, as evidenced by the fact that this car dealership is the top-selling Honda dealership in the United States. However, there was one big problem with the ads that lured customers to the car lot: they were untrue. Though the ads claimed that customers could drive off without any down payment, the FTC found that there were “substantial fees and other amounts” hidden in the fine print (LaReau 2014).

As the Norm Reeves example reminds us, persuasion (as opposed to argument) can be dependent on the use of propaganda. In persuasion, style rather than substance is often utilized to detract from the issue at hand. Persuasion can be steeped in falsehood. Think about the last presidential campaign: Were both parties always truthful in their attempts to persuade you to vote for their candidates?

Argument, on the other hand, is grounded in logic and critical thinking. It is reasoned. It is not overly dependent on style; it is rooted in substance. In Teaching Argument Writing, George Hillocks recognizes three kinds of arguments:

• Arguments of fact: This type of argument dates back to Aristotle and was often taught through syllogisms. For example, start with a major premise: All mortals die. This leads to a minor premise: All men are mortals. Which, in turn, leads to a conclusion: All men will die. But as Hillocks notes, “In most disciplines (with the exception of mathematics and sometimes physics), and in most everyday problems and disputes, we do not have premises that we know to be absolutely true. We have to deal with statements that may be true or that we believe to be true—but are not absolutely true” (2011, xviii). In other words, truth shifts, and, because of this, Hillocks argues we should have our students focus on the other two types of arguments—arguments of judgment and arguments of policy.

• Arguments of judgment: Is the president doing a good job? Who is the greatest living baseball player? What makes a good teacher? To argue any of these questions requires judgment on the part of the writer—judgment, of course, that we hope is supported by facts and evidence.

• Arguments of policy: As Hillocks notes, arguments of policy “typically make a case to establish, amend, or eliminate rules, procedures, practices, and projects that are believed to affect people’s lives” (2011, 67). When a student argues that the school’s dress code is unreasonable, or that the Affordable Care Act is good (or bad), the student is making an argument of policy.

Rather than ask students to write “persuasive essays,” we should give students practice writing both arguments of judgment and arguments of policy. Hillocks (2011), citing Stephen Toulmin’s The Uses of Argument (2003), suggests that arguments of judgment and arguments of policy should include the following:

1. A claim: what is the big idea being argued?

2. Evidence that supports the claim. This evidence should be based in data.

3. A warrant: this explains how the evidence supports the claim.

4. Backing supporting the warrants.

5. Qualifications and rebuttals or counterarguments that refute countering claims. (Hillocks 2011, xix)

To understand how these elements fit into an argument, consider the following excerpt from an argumentative essay:

As a high school student, I think it is unfair that we have to wear school uniforms. Therefore, it is time to get rid of mandatory uniforms at this school.

Most students at Valley High agree with me. They believe they are old enough to decide what to wear. They also believe they are being denied their right to express themselves. Denying students the ability to creatively express themselves is wrong. It is time we were treated like adults.

This is a typical excerpt of argumentative writing that I might get from my students. (I say “typical” because I wrote it for demonstration purposes. Believe me, after twenty-nine years, I have seen enough to create an accurate representation of student argument papers.) To show my students the shortcomings of this draft, I have them compare it against this revision:

As a high school student, I think it is unfair that we have to wear school uniforms. Therefore, it is time to get rid of mandatory uniforms at this school.

Most students at Valley High agree with me, as evidenced by a survey recently conducted through the English classes. When asked if they would support the removal of mandatory school uniforms, 92 percent of students said yes. This is not simply a majority of students who support this position; it is an overwhelming majority. Because this anti-uniform sentiment is so widespread, the time has come to take it seriously. When this many students feel this strongly about the uniform issue, the policy is surely overdue for reevaluation. It is possible that the administration may challenge the validity of the survey, but please know that in an attempt to eliminate bias, it was administered to every student in the school (as opposed, for example, to only giving it to seniors). As such, it is an accurate representation of the feelings of this student body, which means the time has come to give students choice when deciding what to wear to school.

I then have my students notice the elements of the second example:

Claim |

“Therefore, it is time to get rid of mandatory uniforms at this school.” |

Evidence |

“When asked if they would support the removal of mandatory school uniforms, 92 percent of students said yes.” |

Warrant |

“This is not simply a majority of students who support this position; it is an overwhelming majority.” |

Backing |

“Because this anti-uniform sentiment is so widespread, the time has come to take it seriously. When this many students feel this strongly about the uniform issue, the policy is overdue for reevaluation.” |

Rebuttal of the counterargument |

“It is possible that the administration may challenge the validity of the survey, but please know that in an attempt to eliminate bias, it was administered to every student in the school (as opposed, for example, to only giving it to seniors). As such, it is an accurate representation of the feelings of this student body.” |

Having students compare the two models helps to ensure that they will include all of the essential elements of arguments when they write their papers.

When we ask students to make an argument defending the central theme found in To Kill a Mockingbird (Lee 1960), for example, there is not much of an argument there. In effect, the teacher has asked the question “Can you find the main theme in the novel?” and the students dutifully set off in search of evidence to support the answer to the teacher’s question. This line of questioning seems artificial, especially when students know they can go to SparkNotes and immediately find an answer(s). When a student makes a claim that “It takes courage to stand up to racism” is a main theme found in To Kill a Mockingbird, there is no real argument there. An argument is more compelling when there are two people actually arguing.

It’s a little thing to answer someone else’s argument question; it’s a big thing to initiate your own idea and craft an argument from it. This is the kind of argumentative thinking we want our students to develop.

When crafting an argument, students often begin by forming claims and then set out to find data that supports their claims (as with the aforementioned To Kill a Mockingbird example). Hillocks argues that this approach is backward (2011). Instead, he suggests that students should start by reading lots of data, and as they work their way through their reading, they should take note of the interesting claims that begin to emerge.

To consider how this might look in the classroom, let’s look at the case of Philip Seymour Hoffman, the Academy Award-winning actor who died two weeks before I wrote this paragraph. In two weeks’ time and in a number of newspaper articles, the story of Hoffman’s death evolved. Here is the sequence of that evolution:

Philip Seymour Hoffman was found dead in his apartment.

News leaks that he possibly died of a heroin overdose.

Reactions from others pour in.

A video of Hoffman and two men withdrawing money from an ATM surfaces.

Police are trying to find the drug dealer(s). Possible murder charges to be filed.

Obituaries emerge.

Retrospectives of Hoffman’s career appear.

Hoffman had reportedly told friends he was afraid he was going to fatally OD.

Tips surface on how to help someone who is addicted to heroin.

Hoffman had fallen out of rehab shortly before dying.

A report surfaces that Hoffman spent $1000 on drugs the night before he died.

A timeline of his final hours emerges.

Stories emerge examining the use of heroin across the country.

Questions are asked: Where is the heroin coming from? Why is its use increasing?

Four arrests are made in Hoffman’s case. Identities of the suspects are not revealed.

One of the suspects had Hoffman’s phone number on his cell phone.

The suspects’ identities are revealed.

The suspects plead not guilty.

Autopsy results are inconclusive. Further tests pending.

News outlets get hold of and publish parts of Hoffman’s diary.

Hoffman was allegedly involved in a love triangle.

Backlash over printing excerpts from his diary arises.

While reading through this stream of stories interesting questions begin to arise—questions that may eventually lead to meaningful arguments. As Hillocks notes, teachers should try “to find data sets that require some interpretation and give rise to questions. When the data are curious and do not fit preconceptions, they give rise to questions and genuine thinking. Attempts to answer these questions become hypotheses, possible future thesis statements that we may eventually write about after further investigation. That is to say, the process of working through an argument is the process of inquiry” (2011, xxii; emphasis in original). The approach Hillocks suggests is the opposite of the traditional approach to teaching the argument paper, where a student starts with a claim and then begins to find evidence that supports the claim. Instead, Hillocks says that students should start with inquiry. They should “swim” in issues until interesting arguments begin to emerge. For example, given the data generated by the Hoffman story, here are some arguments that emerge that might be worthy of further exploration:

Was Hoffman one of our greatest actors?

Was Hoffman’s death preventable?

Do our nation’s drug policies need overhaul?

Are more rehabilitation facilities needed?

Is more drug prevention work needed in our schools?

Are the “Just Say No” and Red Ribbon Week campaigns effective?

Why is heroin use increasing?

What might a person do to help a friend with an addiction problem?

Is murder an appropriate (or inappropriate) criminal charge in this case?

Is the attention to Hoffman’s case out of proportion?

Do the rich and famous get preferential treatment?

Some of these questions lead to judgment arguments. Others encourage policy arguments. All of the questions were generated after swimming in data (in this case, reading the string of articles published in the days after Hoffman’s death).

After I modeled the process of exploring data and then developing possible claims with my students, I had them find developing stories worthy of tracking. Here are some of the stories they tracked this year:

The debate over sanctions on Iran

The Chris Christie bridge controversy

Richard Sherman (of the Seattle Seahawks) ranting on national television

The fight over Michael Jackson’s estate

Woody Allen being accused of sexual abuse by his daughter

The disappearance of Malaysia Flight 370

The abduction of 300 teenage girls in Nigeria

All of these developing stories have “legs” and can be tracked over time. Tracking them led my students to write interesting argument papers.

For students who have trouble deciding where to begin searching for interesting data, I have them start with The Learning Network, part of the New York Times website. On this site, Learning Network writer Michael Gonchar has posted 200 prompts for argumentative writing under the following broad categories:

Education

Technology and Social Media

Arts and Media: Music, Video Games and Literature

Gender Issues

Sports and Athletics

Politics and the Legal System

Parenting and Childhood

Health and Nutrition

Personal Character and Morality Questions

Science

Other Questions

(Gonchar 2014)

I use Gonchar’s list to show my students how to generate thinking that may lead to interesting arguments. Under “Technology and Social Media,” for example, one of the links is entitled “Does Technology Make Us More Alone?” When a student clicks on that link, he or she will find a YouTube video entitled “I Forgot My Phone” that follows a young woman through her day as the world ignores her because people are too engrossed in their phones. Below the YouTube link, Gonchar posts a series of questions:

• Does technology make us more alone? Do you find yourself surrounded by people who are staring at their screens instead of having face-to-face conversations? Are you ever guilty of doing that, too?

• Is our obsession with documenting everything through photographs and videos preventing us from living in the moment?

• Do you ever try to put your phone down to be more present with the people in the room?

• Do you have rules for yourself or for your friends or family about when and how you use technology in social situations? If not, do you think you should?

• Do you think smartphones will continue to intrude more into our private and social spaces, or do you think society is beginning to push back? (2014)

At the bottom of the web page there is a comments section, where readers are invited to join the argument. It is not my intention that my students pick one of the questions from Gonchar’s list to argue. It is my intention that they pick one of the questions on the site as a jumping-off point to begin reading a data stream that will eventually lead them to form their own arguments. This is where their inquiry starts—inquiry that will eventually lead them to arguments that are yet undiscovered.

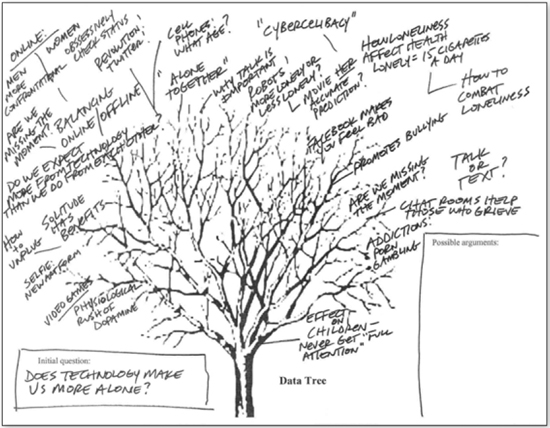

To illustrate to my students how starting with one link can grow into wider thinking, I create a “data tree” (see Figure 4.9).

Figure 4.9 My data tree.

For the technology example, I start with the link “Does Technology Make Us More Alone?” and, starting from the article on that page, I begin to branch my searches for information outward from there. As I read through the data (in this case, a number of related articles), other ideas catch my eye, and I jot them on my data tree. Once the branches of my tree are full, I step back and consider where on the tree some arguments may emerge. For example, here are possible arguments generated by my data tree in Figure 4.9:

Technology is pulling our society apart.

Twitter is a powerful tool for democracy.

Talk is more valuable than texting.

Technology fuels addiction.

Cyberbullying deserves more attention.

It is time to unplug.

The movie Her is a warning we should heed.

Selfies are a new art form.

Being “alone together” is unhealthy.

Facebook contributes to narcissism.

Airlines should not allow phone calls during flight.

Solitude has its benefits.

Technology has weakened parenting skills.

Technology is creating serious health issues.

Shopping from home is not a good thing.

The robot age will be awesome.

Chat rooms have tremendous value (e.g., for people who are grieving).

I can now choose an argument that intrigues me (“Technology has weakened parenting skills”), presenting me with an area to explore in depth via further research. This process has led me to an argument I care about, which will in turn motivate me to take my writing task more seriously. Because I care, I am more likely to conduct deeper inquiry.

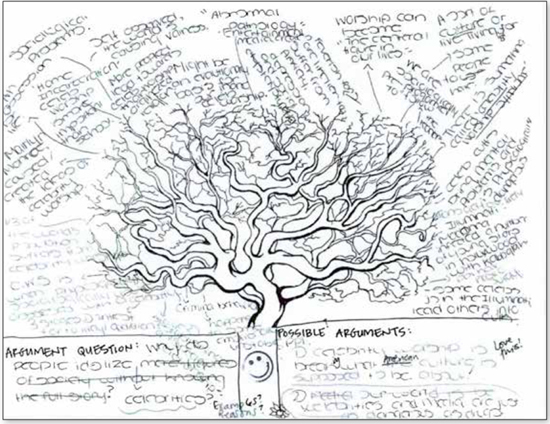

The key point here bears repeating: I have decided on an argument (“Technology has weakened parenting skills”), but I didn’t start with that argument in mind. Instead, I started by reading lots of data under the umbrella of the unit of study, and it was through the reading of this data that my research question emerged. Don’t have students start with a question and then go find the supporting data. Have them discover arguments through the inquiry process. In Figure 4.10, for example, you can see how Grace, an eighth-grade student, started with the question “Why do people idolize celebrities?” After swimming through data, she settles on her argument: “Celebrity worship is breaking what American culture is supposed to be about.” Granted, her argument statement is a bit rough and needs revision (it is an initial draft), but Grace is now invested in doing research to support her argument.

Having students start with inquiry before they generate their arguments works in all content areas, not just in the ELA classroom. If I were a teacher of American history and my students were studying the Civil War, I would want them to read widely about the Civil War before generating their arguments. A student who, through inquiry, generates the argument that economic disparity played a more important role than slavery in causing the Civil War, and another student who, through inquiry, argues that the seeds of the Civil War can be found in the tension between states’ versus federal rights, are going to write much better papers than a student who is simply assigned to respond to the following prompt: “Write an essay explaining the three causes of the Civil War.”

Figure 4.10 Grace’s data tree

When students are taught to approach argument through inquiry, good things happen: they choose topics worthy of arguing, they gain ownership (through choice) of their writing, and their teacher is not stuck in Groundhog Day reading the same argument paper over and over.

Can you imagine living in a world where the five-paragraph essay really existed? In a five-paragraph essay world, you would turn on ESPN for some post-Super Bowl game analysis, and you would hear Chris Berman read the following off the teleprompter:

The Seattle Seahawks defeated the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XLVIII tonight, and in this broadcast we will give you three reasons why.

The first reason the Seahawks won is because their defense shut down Payton Manning and the vaunted passing game of the Broncos. Let’s look at a highlight that demonstrates this.

The second reason the Seahawks won is because they committed fewer turnovers. Let’s look at a highlight that demonstrates this.

The third reason the Seahawks won is because their special teams units outplayed the special teams unit from the Broncos. Let’s look at a highlight that demonstrates this.

As you can see, the Seahawks defeated the Broncos because their defense shut down Payton Manning, they committed fewer turnovers, and their special teams unit outplayed the special teams unit of the Broncos.

At this point, ESPN would cut to a Chevy truck ad. The voiceover would go as thus:

There are lots of trucks to choose from, but the Chevy Silverado is the right truck for you. In this commercial, we will tell you three reasons why.

The first reason you should buy a Chevy Silverado is that it has a new, more fuel-efficient engine. This is important because you will now get better gas mileage, which will save you some of your hard-earned cash.

The second reason you should buy a Chevy Silverado is that it has a quiet highway ride. After a hard day at work, you will want a peaceful ride home.

The third reason you should buy a Chevy Silverado is because it has generous passenger and cargo space. This truck gives you all you need to cart friends and/or cargo around.

The Chevy Silverado is the truck for you because it gets good gas mileage, it provides a quiet highway ride, and it has generous passenger and cargo space.

I hope my point is obvious by now, but in the small chance that it is not, repeat after me: Arguments are not crafted this way! An argument is much more than a claim followed by three reasons. Arguments that are shoehorned into five-paragraph structures are actually weakened by the artificiality of the structure itself. The lameness of the structure diverts the reader’s attention from the argument itself.

As I argue in Write Like This, if students are going to write effective arguments, they need to see what effective arguments look like. They need models, like the following one from Miami Herald columnist Leonard Pitts Jr. (2014). As you read it, notice the “moves” the writer makes that contribute to the effectiveness of his argument.

Perhaps you’ve heard of the Fourth Amendment.

That’s the one that guarantees freedom from unfettered government snooping, the one that says government needs probable cause and a warrant before it can search or seize your things.

That guarantee would seem to be ironclad, but we’ve been learning lately that it’s not. Indeed, maybe we’ve reached the point where the Fourth ought to be marked with an asterisk and followed by disclaimers in the manner of the announcer who spends 30 seconds extolling the miracle drug and the next 30 speed-reading its dire side effects:

To wit: “Fourth Amendment not available to black and Hispanic men walking in New York, who may be stopped and frisked for no discernible reason. Fourth Amendment does not cover black or Hispanic men driving anywhere as they may be stopped on any pretext of traffic violation and searched for drugs. Fourth Amendment does not protect library patrons as the Patriot Act allows the FBI to search your library records without your knowledge. Fourth Amendment does not apply to anyone using a telephone, the Internet or email as these communications may be searched by the NSA at any time.”

To those disclaimers, we now add a new one: “Fourth Amendment not effective at the U.S. border.”

Just before New Year’s, you see, federal Judge Edward Korman tossed out a suit stemming from something that happened to Pascal Abidor, a graduate student who holds dual French and U.S. citizenship. He was taken off an Amtrak train crossing into New York from Canada in May 2010, cuffed and detained for hours by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents. They seized his laptop and kept it for 11 days.

It seems the computer contained photos of rallies by Hamas, the radical Islamist group, and his passport indicated travel in the Middle East. Abidor explained that he’s a student of Islamic studies at McGill University and that he’s researching his doctoral thesis. According to at least one news report, he’s not even Muslim.

None of this moved the border agents—or the judge. He rejected the suit, brought by the ACLU, among others, on behalf of Abidor and the National Press Photographers Association, among others, on grounds the plaintiffs had no standing to bring suit because, he says, the searches are so rare there is little risk a traveler will be subjected to one.

More jarring, Korman found that even had the suit gone forward the plaintiffs would have lost on the merits.

It is permissible, he said, for border agents to seize your devices and copy your files, even without any suspicion of wrongdoing. He questioned whether people really need to carry devices containing personal or confidential material and said that dealing with a possible search of such a device is just one of the “inconveniences” a traveler faces.

As it happens, border-control officers already operate under a looser constitutional standard. They are allowed to conduct warrantless, suspicionless searches of our bodies and our bags.

But our laptops? Our iPads? These devices are repositories of financial records, health information, confidential news sources and diaries.

Are you required to surrender even the most intimate stuff of your life and work on the whim of a border agent because he or she doesn’t like your looks?

Apparently, yes.

It is a sobering reminder—not simply that the law lags the innovations of the Information Age, not simply that the whole idea of privacy is shrinking like an ice cube in a tea kettle, but also that if you lard a right with too many “exceptions,” that right becomes impotent.

So maybe instead of counting the places and situations where the Fourth Amendment no longer applies, we should start counting the ones where it still does.

It’s getting so that might be a shorter list.

When I have students read arguments like this one, I have them do what I asked you to do—notice the moves employed by the writer to sharpen the argument being made. Here are a few moves they noticed Pitts made in this essay:

Uses intentionally short, one sentence paragraphs

Weaves in an anecdote to support the claim

Uses humor to connect with the reader

Asks rhetorical questions

Makes a claim that is implied, rather than directly stated

After we read the Pitts essay closely, I have my students read other argumentative models. Students need to know what the genre looks like before they can write in the genre (see Chapter 6 for more on the importance of modeling).

Once in a while, a kid will say to me, “I don’t know which side of the argument to take. Both sides have good points.” I am fine with that, as long as the student has demonstrated that he or she has thoughtfully read about and given careful consideration to the issue at hand. I am afraid I have been guilty in the past of forcing children to take positions on complex issues when they may not be intellectually or developmentally ready to do so. Sometimes, I have to remind myself, it is more important that a kid carefully consider both sides of an argument than take a definitive stand.

Amid the controversy swirling around the CCSS, let’s be mindful that when it comes to the teaching of writing, the anchor writing standards get the following right:

• The new Common Core standards, unlike many state standards in the NCLB era, recognize that reading and writing are interconnected. They encourage students to read like writers and to write like readers.

• Since exams of the Common Core standards value writing across the curriculum, they may drive more writing across the curriculum. This, in turn, may drive deeper thinking across the curriculum. More writing is always good for kids.

• The Common Core anchor writing standards will sharpen writing skills in the following discourses: narrative, inform and explain, and argument. These discourses all hold value long after graduation.

All of these bulleted items align nicely with our core values of teaching writing, and I hold out hope that the Common Core standards will induce more and better writing in our schools. But a careful examination of what the anchor writing standards get right illuminates the flip side as well—it raises awareness of what the new standards get wrong. And, unfortunately, when it comes to the teaching of writing, these new standards come with major shortcomings. For what they get wrong, and for how to ensure that our writing instruction stays true to our students’ best interest, let’s move to Chapter 5.